Tragic Tales and Epic Adventures: Essay Topics in Greek Mythology

Table of contents

- 1 Tips on Writing an Informative Essay on a Greek Mythical Character

- 2.1 Titles for Hero Essays

- 2.2 Ancient Greece Research Topics

- 2.3 Common Myth Ideas for Essays

- 2.4 Topics about Greek Gods

- 2.5 Love Topics in the Essay about Greek Mythology

With its rich pantheon of gods, heroes, and timeless tales, Greek mythology has been a source of inspiration and fascination for centuries. From the mighty exploits of Hercules to the cunning of Odysseus, these myths offer a window into ancient Greek culture, values, and understanding of the world. This exploration delves into various aspects of Greek mythology topics, providing a wealth of ideas for a captivating essay. How do myths impact today’s society? Whether you’re drawn to the legendary heroes, the powerful gods, or the intricate relationships within these stories, there’s a trove of ideas to explore in Greek mythology research topics.

Tips on Writing an Informative Essay on a Greek Mythical Character

Crafting an informative essay on a Greek mythical character requires a blend of passionate storytelling, rigorous research, and insightful analysis. Yet, there are some tips you can follow to reach the best result. Read this student essay written about the Greek mythology guide.

- Select a Fascinating Character. Choose a Greek mythical character that genuinely interests you. Your passion for the character will enhance your writing and engage your readers.

- Conduct Thorough Research. Dive into the character’s background, roles in various myths, and their significance in Greek mythology. Use reliable sources such as academic papers, respected mythology books, and scholarly articles to gather comprehensive and accurate information.

- Analyze Characteristics and Symbolism. Explore the deeper meanings behind your character’s actions and traits. Discuss what they symbolize in Greek culture and mythology.

- Use a Clear Structure. Organize your essay logically. Ensure each paragraph flows smoothly to the next, maintaining a coherent and compelling narrative.

- Incorporate Quotes and References. Use quotes from primary sources and reference key scholars to support your points. This adds credibility and depth to your essay.

- Edit and Revise. Finally, thoroughly revise your essay for clarity, coherence, and grammatical accuracy. A well-edited essay ensures your ideas are conveyed effectively.

By following these tips, you can create a compelling essay that recounts famous myths and explores the rich symbolic and cultural significance of these timeless tales.

Greek Mythology Topics for an Essay

Explore the rich tapestry of Greek mythology ideas with these intriguing essay topics, encompassing legendary heroes, ancient gods, and the timeless themes that have captivated humanity for millennia. Dive into the stories of Hercules, the wisdom of Athena, the complexities of Olympian deities, and the profound lessons embedded in these ancient tales. Each topic offers a unique window into the world of Greek myths, inviting a deep exploration of its cultural and historical significance.

Titles for Hero Essays

- Hercules: Heroism and Humanity

- Achilles: The Warrior’s Tragedy

- Odysseus: Cunning over Strength

- Theseus and the Minotaur: Symbolism and Society

- Perseus and Medusa: A Tale of Courage

- Jason and the Argonauts: The Quest for the Golden Fleece

- Atalanta: Challenging Gender Roles

- Ajax: The Unsung Hero of the Trojan War

- Bellerophon and Pegasus: Conquest of the Skies

- Hector: The Trojan Hero

- Diomedes: The Underrated Warrior of the Iliad

- Heracles and the Twelve Labors: A Journey of Redemption

- Orpheus: The Power of Music and Love

- Castor and Pollux: The Gemini Twins

- Philoctetes: The Isolated Warrior

Ancient Greece Research Topics

- The Trojan War: Myth and History. Examining the blending of mythological and historical elements in the story of the Trojan War.

- The Role of Oracles in Ancient Greek Society. Exploring how oracles influenced decision-making and everyday life in Ancient Greece.

- Greek Mythology in Classical Art and Literature. Analyzing the representation and influence of Greek myths in classical art forms and literary works.

- The Historical Impact of Greek Gods on Ancient Civilizations. Investigating how the worship of Greek gods shaped the societal, cultural, and political landscapes of ancient civilizations.

- Mythology’s Influence on Ancient Greek Architecture. Studying the impact of mythological themes and figures on the architectural designs of Ancient Greece.

- Athenian Democracy and Mythology. Exploring the connections between the development of democracy in Athens and the city’s rich mythological traditions.

- Minoan Civilization and Greek Mythology. Delving into the influence of Greek mythology on the Minoan civilization, particularly in their art and religious practices.

- The Mycenaean Origins of Greek Myths. Tracing the roots of Greek mythology back to the Mycenaean civilization and its culture.

- Greek Mythology and the Development of Theater. Discuss how mythological stories and characters heavily influenced ancient Greek plays.

- Olympic Games and Mythological Foundations. Examining the mythological origins of the ancient Olympic Games and their cultural significance.

- Maritime Myths and Ancient Greek Navigation. Investigating how Greek myths reflected and influenced ancient Greek seafaring and exploration.

- The Impact of Hellenistic Culture on Mythology. Analyzing how Greek mythology evolved and spread during the Hellenistic period.

- Alexander the Great and Mythological Imagery. Studying the use of mythological symbolism and imagery in portraying Alexander the Great.

- Greek Gods in Roman Culture. Exploring how Greek mythology was adopted and adapted by the Romans.

- Spartan Society and Mythological Ideals. Examining Greek myths’ role in shaping ancient Sparta’s values and lifestyle.

Common Myth Ideas for Essays

- The Concept of Fate and Free Will in Greek Myths. Exploring how Greek mythology addresses the tension between destiny and personal choice.

- Mythological Creatures and Their Meanings. Analyzing the symbolism and cultural significance of creatures like the Minotaur, Centaurs, and the Hydra.

- The Underworld in Greek Mythology: A Journey Beyond. Delving into the Greek concept of the afterlife and the role of Hades.

- The Role of Women in Greek Myths. Examining the portrayal of female characters, goddesses, and heroines in Greek mythology.

- The Transformation Myths in Greek Lore. Investigating stories of metamorphosis and their symbolic meanings, such as Daphne and Narcissus.

- The Power of Prophecies in Greek Myths. Discussing the role and impact of prophetic declarations in Greek mythological narratives.

- Heroism and Hubris in Greek Mythology. Analyzing how pride and arrogance are depicted and punished in various myths.

- The Influence of Greek Gods in Human Affairs. Exploring stories where gods intervene in the lives of mortals, shaping their destinies.

- Nature and the Gods: Depictions of the Natural World. Examining how natural elements and phenomena are personified through gods and myths.

- The Significance of Sacrifice in Greek Myths. Investigating the theme of voluntary and forced sacrifice in mythological tales.

- Greek Mythology as a Reflection of Ancient Society. Analyzing how Greek myths mirror ancient Greek society’s social, political, and moral values.

- Mythical Quests and Adventures. Exploring the journeys and challenges heroes like Jason, Perseus, and Theseus face.

- The Origins of the Gods in Greek Mythology. Tracing the creation stories and familial relationships among the Olympian gods.

- Lessons in Morality from Greek Myths. Discussing the moral lessons and ethical dilemmas presented in Greek mythology.

- The Influence of Greek Myths on Modern Culture. Examining how elements of Greek mythology continue to influence contemporary literature, film, and art.

Topics about Greek Gods

- Zeus: King of Gods. Exploring Zeus’s leadership in Olympus, his divine relationships, and mortal interactions.

- Athena: Goddess of Wisdom and War. Analyzing Athena’s embodiment of intellect and battle strategy in myths.

- Apollo vs. Dionysus: Contrast of Sun and Ecstasy. Comparing Apollo’s rationality with Dionysus’s chaotic joy.

- Hera: Marriage and Jealousy. Examining Hera’s multifaceted nature, focusing on her matrimonial role and jealous tendencies.

- Poseidon: Ruler of Seas and Quakes. Investigating Poseidon’s dominion over the oceans and seismic events.

- Hades: Lord of the Underworld. Delving into Hades’s reign in the afterlife and associated myths.

- Aphrodite: Essence of Love and Charm. Exploring Aphrodite’s origins, romantic tales, and divine allure.

- Artemis: Protector of Wilderness. Discussing Artemis’s guardianship over nature and young maidens.

- Hephaestus: Craftsmanship and Fire. Analyzing Hephaestus’s skills in metallurgy and his divine role.

- Demeter: Goddess of Harvest and Seasons. Investigating Demeter’s influence on agriculture and seasonal cycles.

- Ares: Embodiment of Warfare. Delving into Ares’s aggressive aspects and divine relations.

- Hermes: Divine Messenger and Trickster. Exploring Hermes’s multifaceted roles in Olympian affairs.

- Dionysus: Deity of Revelry and Wine. Analyzing Dionysus’s cultural impact and festive nature.

- Persephone: Underworld’s Queen. Discussing Persephone’s underworld journey and dual existence.

- Hercules: From Hero to God. Examining Hercules’s legendary labors and deification.

Love Topics in the Essay about Greek Mythology

- Orpheus and Eurydice’s Tragedy. Analyzing their poignant tale of love, loss, and music.

- Aphrodite’s Influence. Exploring her role as the embodiment of love and beauty.

- Zeus’s Love Affairs. Investigating Zeus’s romantic escapades and their effects.

- Eros and Psyche’s Journey. Delving into their story of trust, betrayal, and love’s victory.

- Love and Desire in Myths. Discussing the portrayal and impact of love in Greek myths.

- Hades and Persephone’s Love. Analyzing their complex underworld relationship.

- Paris and Helen’s Romance. Examining their affair’s role in sparking the Trojan War.

- Pygmalion and Galatea’s Tale. Exploring the theme of transcendent artistic love.

- Alcestis and Admetus’s Sacrifice. Investigating the implications of Alcestis’s self-sacrifice.

- Apollo’s Unrequited Love for Daphne. Discussing unreciprocated love and transformation.

- Hercules and Deianira’s Tragic Love. Exploring their love story and its tragic conclusion.

- Jason and Medea’s Turmoil. Analyzing their intense, betrayal-marred relationship.

- Cupid and Psyche’s Resilience. Delving into the strength of their love.

- Baucis and Philemon’s Reward. Exploring their love’s reward by the gods.

- Achilles and Patroclus’s Bond. Discussing their deep connection and its wartime impact.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

How to Write a Greek Mythology Essay

Introduction

Greek mythology has fascinated scholars and enthusiasts for centuries. The epic tales of gods, heroes, and mythical creatures have captivated the imagination of people across the globe. Writing a Greek mythology essay provides the perfect opportunity to delve into this engrossing subject and showcase your knowledge and analytical skills. In this comprehensive guide, we'll explore the key components of a successful Greek mythology essay and provide valuable tips and insights to help you craft an outstanding piece of academic writing.

Understanding Greek Mythology

Before embarking on your essay, it's important to have a solid understanding of Greek mythology's rich tapestry. Greek mythology encompasses a vast array of gods, goddesses, heroes, and mythical creatures, each with their own unique attributes and stories. Familiarize yourself with the major gods and goddesses, such as Zeus, Athena, and Apollo, as well as renowned heroes like Hercules and Perseus. Additionally, acquaint yourself with prominent myths, such as the Trojan War and the adventures of Odysseus in the Odyssey . This foundation will provide you with a wealth of material to analyze and discuss in your essay.

Choosing a Topic

When selecting a topic for your Greek mythology essay, consider your personal interests and the specific requirements of your assignment. You could focus on a particular god or goddess and explore their significance in Greek mythology, examining their roles and associated myths. Alternatively, you may opt to discuss a specific heroic figure and analyze their portrayal in various myths.

Another approach is to explore the overarching themes present in Greek mythology, such as the concept of fate, the power dynamics between gods and mortals, or the representation of women in ancient Greek society. By narrowing down your topic and selecting a specific angle, you can delve deeper into the subject matter and present a more focused and compelling essay.

Research and Gathering Sources

A successful Greek mythology essay relies on thorough research and a solid understanding of the primary sources. Dig deep into the works of renowned Greek writers, such as Homer, Hesiod, and Ovid, who have provided invaluable insights into the mythology of ancient Greece. Explore their epics and poems, such as the Iliad and the Metamorphoses , to gain a comprehensive understanding of the myths and characters.

In addition to classical sources, consult modern academic books, articles, and scholarly journals to gain different perspectives and interpretations. This will enable you to present a well-rounded analysis of your chosen topic and demonstrate your ability to engage with reputable sources.

Structuring Your Essay

A well-structured essay is crucial for conveying your ideas coherently and logically. Begin with an engaging introduction that provides background information on Greek mythology and presents your thesis statement. Your thesis statement should clearly state your argument or the main point you'll be discussing in your essay.

Subsequently, organize your essay into distinct paragraphs that focus on specific aspects or themes. Each paragraph should have a clear topic sentence that introduces the main idea and supports your thesis. Use evidence from your research to support your claims and ensure a well-supported argument.

Remember to include appropriate citations and references whenever you include information from external sources. This demonstrates your academic integrity and strengthens your arguments.

Analyzing and Interpreting the Myths

Throughout your essay, aim to provide thoughtful analysis and interpretation of the myths you're discussing. Consider the cultural, historical, and societal contexts in which these myths were created, and explore their relevance and enduring impact on literature and popular culture.

Examine the themes, symbolism, and character motivations present in the myths. Compare and contrast different versions of the same myth to gain a deeper understanding of the variations and underlying messages. Engage with scholarly debates and offer your own well-reasoned interpretations.

In your conclusion, summarize your main arguments and restate your thesis in a concise manner. Reflect on the broader significance of Greek mythology and its enduring legacy. Conclude with a thought-provoking statement that leaves the reader with a lasting impression.

Final Thoughts

Writing a Greek mythology essay provides a captivating journey into the world of ancient gods and heroes. By following the steps outlined in this guide, you'll be well-equipped to craft an exceptional essay that showcases your knowledge and analytical prowess.

Remember to dedicate ample time to research, planning, and revision. Engage with primary and secondary sources, formulate a strong thesis, and present your arguments coherently. With these tools at your disposal, you'll be able to write an essay that stands out from the rest and demonstrates your expertise in the captivating realm of Greek mythology.

Case Study Help Online - Studybay

Essay on Silence: Comprehensive Guide - Studybay

Web Design Homework Help Website Design Assignment Help

How To Write an Academic Article

Find The Best Internship Essay Sample Right Here

Business Plan Composition: Outline Your Success - The Knowledge Nest

Help With Nursing Assignments - Studybay

Definition Of Heroism Essay: Great Example And Writing Tips

Book Report Helper - Book Report Writing Service

9 Trends In Hardware and Software to Bring You Up to Speed

a world on the web

Writing tips 1: How to Work with Myths and Legends

Published on Wednesday 7th May 2014 by Lucy Coats

Since I am this mad mythology-obsessed writer, I thought I’d kick off my series of occasional writing tips and tricks with brief ‘useful guide’ for those of you who might be interested in this area of fiction too, but weren’t quite sure how or where to begin. So, first I’ll ask the obvious question!

What use are myths and legends to a fiction writer? Why should I use them as a starting point for my stories?

Myths and legends—and fairytales and folklore too—are a fantastic resource for the writer, a huge treasure chest of goodies to spark the creative imagination. Just look at what’s out there for you to plunder! There’s the Greeks (all those fallible and rather human gods and goddesses, as well as a whole clutch of butch heroes and scary monsters); there’s the Celts (more muscle-bound heroes, plus the original elves or fairies in their many manifestations): there’s the Norse lot (warrior gods and ice giants and brave maidens with breastplates); there’s the Eastern Europeans (witches, vampires, werewolves); there’s the Far East (here be wise and intelligent dragons); there’s the Aboriginal Australians (bunyips, songlines, animal Ancestors); there’s the Americas North and South (thunderbirds, tricksters, hidden cities of gold) – and then there’s my newest discovery, the Egyptians (shape-shifting animal gods and goddesses, a scary underworld, the magic of sun and moon).

Are you excited yet? Because I am, just writing down a fraction of what’s out there for you. Go forth and raid your local library at once! Devour the mythology section bit by bit, and read it all. If you don’t get some kind of idea for your book after that, I’ll be willing to consider eating my hat. With ketchup and possibly a side-order of Worcestershire Sauce.

What if I want to do retellings? How much should I remain faithful to existing texts?

I’m not going to lie. Retellings can be tricky, especially if you’re going to be doing them for children. I should know—I’ve done over 150 of them, both Greek and Celtic, as well as retellings of Oscar Wilde and other more modern writers. It’s important a) to know your original source material and b) to know what to skate over/ignore/discard. As you can imagine, the Greek myths have lots of incest, murder, rape and all that. People always ask me how I ‘get round it’. My answer is that since kids don’t know it was there in the first place, they won’t know it’s missing—and if they get hooked on myths through my stories, they can always go and look at the originals for themselves later on. The most important thing is to make the story exciting and accessible in language terms. I’ve never had a kid ask a tricky question about why Zeus has children with his sisters, by the way, nor about his dodgy habit of turning into animals or birds to seduce young and pretty maidens.

How much research should I do?

I have a whole bookshelf devoted to myths and legends—both the original tales themselves, and research relating to them, which I refer to all the time. Even though most of them are in my head already, there are always details I need to check up on. And if there’s a relevant book that I need and I haven’t got, or that is out of print, I hunt it down, either in my local library or via secondhand bookshops on the internet (Abe Books www.abebooks.co.uk is always a good place to start). Research is never wasted—but my Top Tip is to be sure and keep notes on page numbers of where you find useful stuff. It can be maddening and time-consuming to comb your books for that vital fact you remember seeing somewhere and need right now! I’ve made that mistake FAR too often!

How do I tackle the job of incorporating existing myths into my work of original fiction? How much creative licence am I allowed?

I have huge fun with the retellings, but they can seem a little constricting. I found writing my own first novel incredibly liberating in that respect, because I wasn’t hemmed in by having to stick to a script, and it was the same with my forthcoming Beasts of Olympus series, in which I take characters and creatures from Greek myth and weave them into my own story, taking a few liberties along the way, but trying to remain true to the essentials of the originals.

So, in your case, let’s say something mythological takes your fancy. You want to write a novel about, for example, a modern-day American boy who finds out he’s the son of Poseidon…oh wait—Rick Riordan already did that with Percy Jackson! There’s a long and honourable line of authors who have taken elements of myth and done whatever the heck they wanted with them. There’s the greatest myth-plunderer of all, JRR Tolkien, there’s Neil Gaiman (American Gods etc), Joanne Harris (Runemarks), Kevin Crossley-Holland (The Arthur trilogy)—and then there’s me.

My first teen novel, Hootcat Hill , has elements of Celtic and Norse myth, plus a smidgin of Arthurian legend thrown into the mix. I took a lot of liberties and I found it made me want to go ‘wheeeee!’ with a slightly naughty sense of excitement every time I did so. This was my story, and who had the right to inform me it ‘didn’t happen that way because Ovid (or whoever) tells it differently’? No one, that’s who! I think as long as you have a passion for and know your original sources well, it’s ok to treat them with a little ‘loving disrespect’. In my case, I made the Norse Völundr (Weland) into a modern blacksmith in red leathers, who rides a fast motorbike and has a bad line in jokes.

The two YA novels I’m working on at the moment stray into a slightly different territory – the one where actual history meets mythology. No one knows anything concrete about Cleopatra’s life before she entered the history books, but she’s a real person. That meant I could let my imagination go free, and, as she was later described as ‘the new Isis’, it seemed right to make Isis her patron goddess and a very real presence in Cleo’s life.

Myths are not just for dry, dusty old anthropology professors to muse over in their ivory towers—they’re living stories which we continually reinvent for the times we live in. And it’s up to us as writers and tellers of tales to make sure they never die or are forgotten. So have fun exploring loads of different myths and thinking ‘What If’? Because you never know what might happen!

8 comments so far

A good post. With thousands of years of literature at our disposal, there can be no excuse for writer’s / illustrators’ block. Loved the “myth-plunderer” line. Got me to wondering if there’s such a thing as a modern myth?

Regardless, a very good read!

This is wonderful! It’s so great to see another author’s take on retelling the myths of old.

I am trying that out too. I am writing a Romeo & Juliet/Little Red Riding Hood retelling with a greek mythology setting.

I am planning a Bajirao Mastani/Rumpelstiltskin retelling with hindu mythology setting.

it seems really fun to do all the research and yet twist it to what my characters require. Even more because I have to find a common ground between both.

thank you for this it was definitely a confidence boost for me (I’m only 12 but hopefully I’ll become the next big thing)

I love this article as I am fascinated by the amazing tales in myth and folklore. At the moment I’m writing a book where the main character is half Hulder (from Scandinavian folklore). However I was wondering, is it ok to take creatures from other places’ myths and folklore if it’s relevant to the story? I’d like for this universe to have all sorts of creatures from near every myth (each originally living in where they were spoken of but in modern day they mainly roam the earth wherever). I was wondering if that was ok. I’m definitely doing research and not just throwing them in, so I hope I’m not disrespecting them.

So glad you liked the piece and found it useful. Also, good question. Many fantasies have in the past used mythical creatures in a mix from all the mythologies. However, there has been a lot of anger over cultural appropriation in recent times, even when research has been thorough. Right now, using creatures/beings from a culture clearly not the author’s own (and entirely set in that culture) is often seen as problematic by editors. It’s a difficult one, but I think being respectful and not using/perpetuating stereotypes is where to start. I guess if your world has a cornucopia of nations who interact together, you’ll probably be fine. Personally, I like the idea of all the mythos working together. It’s why I wrote a book with Greek and Norse gods in it! Good luck with the writing! PS I love the Hulderfolk.

So sorry for the late reply. This blog isn’t active any more, so I don’t visit often. Glad it boosted your confidence and good luck with any writing you’re doing. I shall look out for a Human Bean bestseller on the bookshelves in due course.

Thank you. And yes I understand the issue of perpetuating stereotypes, I’ll be sure to be careful about that in my writing. I wouldn’t want to offend, only write a good story and show people cool myths they never knew of before. 🙂

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent blog posts.

- Flow: A Pair of New Masterclasses for Writers

- After the Election – a response to President-Elect Trump

- CHOSEN is nearly here!

- The Joy of Creative Napping

- It’s #UKYADAY – Win a CLEO Mug to celebrate!

My latest Tweets...

10 Writing Prompts from Greek Mythology

Not sure what you want to write your next story about? Need some inspiration to add life to a current project? Ever thought about using writing prompts from Greek mythology?

Storytelling has been around since there have been people with language. Humans need to experience their world through stories and through connections to others. These are stories that have been around for thousands of years, which means there is something compelling about them. Getting your writing inspiration from Greek Mythology can be a fun way to revitalize your own storytelling methods. The Greeks had some pretty amazing stories. Even Shakespeare was influenced by Greek mythology. Romeo and Juliet is an adaptation (of an adaptation) of the myth of Pyramus and Thisbe.

Using a myth as a starting point helps to give you a basic outline so you can focus on adding details and developing characters. To make it interesting you can play with the original story by changing key elements. What happens if you change the gender of the main character? What if you zoom the story into the future? They myths are often vague enough you can give the characters more detailed motivations. Change the relationships or the outcome of the story. See what the myth makes you think of and run with it. Have fun!

Below is a list of 10 writing prompts from Greek mythology and some ways you could use them to make an all new story.

And if you find these helpful, try the prompts from Irish , Norse , and Bulgarian myths.

1) Pyramus and Thisbe

Pyramus and Thisbe were two young people whose parents hated each other. The two were never allowed to spend time together but came to fall in love by talking through a hole in the wall. They decided to meet in person one night and arranged to meet near an old tomb under a mulberry tree. Thisbe got there first and saw a lion, bloody with its last meal, and fled in terror, leaving behind her veil. Pyramus then arrived, saw the veil, and assumed the lion had eaten his beloved. He fell on his sword under the mulberry tree. When Thisbe returned she saw Pyramus and lamented his death bitterly. She then killed herself with the same sword. Their blood splashed on the mulberry tree and the gods changed the color to red permanently in honor of the two lovers.

Writing Prompt

This is a story that has been done many times. For a fresh take, try changing the genre. You could have star-crossed lovers on a generation ship headed to colonize a new planet. Then an alien parasite takes over and makes people see their worst nightmares, in this case making the lovers see the image of each other dead. You could keep the ending or perhaps they find a way to fight it.

2) Sisyphus

King Sisyphus was overall a terrible man. He murdered his guests, a violation of the guest-host relationship Greeks prided themselves on, and generally ruled by force and cruelty. Furthermore he often claimed to be cleverer than Zeus, which was ultimately his downfall. On two different occasions he managed cheat death. The first time was when he betrayed a secret of Zeus so the god ordered Thanatos, Death, to chain Sisyphus in the Underworld. Sisyphus tricked Thanatos into getting chained himself and then escaped. As long as Death was chained, no one could die. No one could make sacrifices to the gods and no one could die in war. Ares eventually got angry that is wars were not as interesting with no death so he went and freed Thanatos and delivered Sisyphus.

Upon being delivered to the Underworld this time, the arrogant King tricked Persephone into letting him go. Finally Zeus stepped in and instead of letting Sisyphus spend his death in the Elysian Fields, forced him to push a rock up a hill. Zeus tricked Sisyphus by enchanting the rock to roll away from him and back down the hill making the task last for eternity.

Create a character who breaks a cherished tradition or challenges a respected authority. What creative punishments can you come up with? The story could be from the perspective of the rule-breaker, perhaps s/he is misunderstood or was tricked him/herself. Or make it from the perspective of the law enforcer tracking down the culprit after s/he escapes, for the first or second time.

3) Pygmalion and Galatea

Pygmalion was a sculptor on Cyprus. He had had a bad experience with some prostitutes and swore off women entirely, disdaining them all because of his experience. When he returned home be began working on a new project, an ivory carving of a woman he called Galatea. He poured everything into the sculpture and soon it was more beautiful than any woman alive. He cherished it and dressed it and brought it gifts. One day, he sacrificed a bull at the temple of Aphrodite. The goddess saw him and knew his desire. She granted his wish and gave him a sign, making the flames shoot up three times. When Pygmalion returned home he found his statue had come to life. Aphrodite blessed them with a happy, loving marriage and they even had a son.

Try this story with a gender swap. Or maybe imagine what a normal person would do when a statue came to life – freak out! You could also try from the statue’s point of view; is she conscious while she is ivory? How does she adjust to being alive?

Halcyon was the daughter of Aeolus the ruler of the winds. She was married to Ceyx, the king of Tachis. Their love was so strong even the gods knew about it. When Ceyx had to travel to consult the oracle at Delphi, Halcyon begged him not to go by boat because she was afraid of the sea. He went anyway and was lost in a storm. But before he drowned he asked Poseidon to bring his body back to the shore where Halcyon could find him.

Meanwhile, Haclyon asked Hera to keep him safe. Too late to save him, Hera sent Morpheus to tell her of Ceyx’s death. Halcyon was so distraught that she threw herself into the sea. The gods were so moved by her devotion that they transformed her and Ceyx into kingfisher birds so they could remain together on the shores. Aeolus calms the winds every January to allow the kingfishers to nest and raise their eggs. These are called the Halcyon days.

What if instead of dying in a storm Ceyx was deliberately attacked by one of the gods or even Halcyon’s father. Imagine if their deaths were faked and they were put into a sort of divine witness protection.

5) Bellerophontes and Pegasus

Bellerophontes, besides having one of the coolest names ever, was an adventurer. He loved looking for trouble and was an accomplished equestrian. His friend, Proteus a sea god, became jealous and sent Bellerophontes to his father in law in Lycia with a note that said the messenger should be killed. Bellerophontes didn’t know he shouldn’t trust Proteus so he delivered the note to the king. The king decided that instead of killing him outright, he would send Bellerophontes to kill the chimera who had been terrorizing region.

In order to succeed Bellerophontes was told he needed to tame Pegasus. He was advised to pray to Athena and sleep in her temple for a solution. He did so and Athena came to him in a dream. She told him where Pegasus went for water and gave him a golden bridle. Bellerophontes found Pegasus and waited, hiding, until the winged horse came and knelt for a drink. Then he jumped on the horse’s back and put the bridle on. Pegasus took to the sky and tried to get free but Bellerophontes kept a firm hold and eventually won the contest. Together the pair defeated the chimera, freeing the people of Lycia and winning the King’s daughter.

But Bellerophontes wanted more adventure. He wanted to fly Pegasus to Mt. Olympus. The gods were incredulous and Zeus decided to take action. He sent a gadfly to bite Pegasus, who then threw Bellerophontes. Athena saved the adventurer’s life but he was crippled. He spent the rest of his days searching for Pegasus but could not find him because Zeus kept the flying horse for himself.

This would be another fun one for a gender swap. Try making Bellerphontes a woman who wants to adventure despite social norms regarding women. Her friend might try to get her killed with the note to keep her from rocking the boat. Perhaps her fall from Pegasus comes when she tries to achieve too much for her sex. Or maybe she succeeds and shows them all.

6) Orpheus and Eurydice

Orpheus was the son of Apollo and Calliope, one of the muses, and had incredible skill with the lyre. He fell in love with Eurydice and they were happily married for a long time. But one day while out for a walk, Eurydice was harassed by a man who was beguiled by her beauty. She tried running away but was bitten by a snake and died. Orpheus was so distraught he played a song on his lyre that moved all the people and things on the earth. The gods were so touched that they allowed Orpheus to go to Hades to see his wife.

Orpheus played for Hades and Persephone and earned his wife back. The condition was that he could not turn to look back at her until he was fully in the light of the earth again. Just shy of the light, Orpheus began to doubt Hades because he couldn’t hear Eurydice’s footsteps. He turned and saw her as she was whisked back down to the Underworld. Again grief tore through Orpheus and he played his lyre and begged for death to take him so he could join his beloved. A pack of beasts, or Zeus with a lightning bolt, granted his wish and killed him. (But the muses kept his head and enchanted it to keep singing.)

This time change the genre. What would happen if this story took place in a distant future where humans are perfecting the ability to revive the dead. Orpheus tries to bring his love back but somehow loses his faith and loses her again at the last minute. Or, maybe humans have discovered a way to see into the afterlife and Orpheus treks into the unknown to bring her back but something goes wrong. You could always throw in some aliens for good measure.

7) Atalanta

Atalanta was an interesting figure and has several stories surrounding her. When she was born her father, King Shoeneus wanted a son so he abandoned her on a mountaintop to die or be saved by the gods. A bear adopted her and Atalanta became an impressive hunter. She took part in the hunt for the Calendonian Boar, making most of the men in the hunting party angry, but she was the first to draw blood from the beast.

Meleager, who eventually abandoned his wife for Atalanta, fell in lover with her and awarded her the boar’s skin. His uncles were furious that a woman was given the skin and Meleager killed them for their actions. Atalanta returned Meleager’s love but had sworn a vow of chastity to the goddess Artemis because of a prophesy that said losing her virginity would be disastrous for her. Distraught, Meleager joined the Argonauts to get away but Atalanta joined the crew to follow him upsetting Jason and many of the other crew members. But she took part in battles and was a benefit to the crew. She even won a wrestling match against Peleus.

Through the boar hunt, Atalanta’s father found out about her and wanted her back to marry her off. She did not want to, however, and forced him to agree that a suitor would have to beat her in a footrace, or be killed. He agreed and many men died in the attempt to win her hand. Finally, Hippomenes won by asking Aphrodite for help. She gave him three golden apples, which could not be resisted. When Atalanta pulled ahead of him in the race, he rolled out an apple and she had to go after it. He won the race and she married him.

They had a son, Parthenopaios, and lived happily for a while but met an unfortunate end. They ended up being punished either for making love in the temple of Zeus or for not giving Athena proper honor. The two were turned into lions, which were believed to only mate with leopards and not other lions, meaning they wouldn’t be able to be together anymore.

Atalanta provides many stories to work with. Pick one or put them all together into a longer work. The story of Atalanta and Meleager would make for a compelling romantic tragedy (typical Greeks). You could also change it some. Perhaps Atalanta is under a curse that the two must break in order to be together. (There, teach those Greeks it doesn’t always have to end in tragedy.)

8) Theseus and the Minotaur

After his son was assassinated, King Minos of Crete declared war on Athens. As the result of a war or of Athen’s surrender, every nine years seven Athenian boys and seven girls were sent to Crete as sacrifice. They were forced into the Labrynth to face the Minotaur. On the third shipment of youths, Theseus volunteered to go and slay the beast.

When he got there, King Minos’ daughter, Ariadne, offered to help Theseus. He told her he would take her with when he escaped. She gave him a ball of thread to mark his path and told him how to get to the center. He made his way to the Minotaur and killed and decapitated it. Theseus escaped in the night with the Athenian youths, Ariadne and her sister. They stopped on the island of Naxos to rest and Athena woke Theseus early, telling him to abandon Ariadne there. Theseus left before she woke. Ariadne was distraught when she woke alone and the god Dionysus, whose island she was on, felt bad for her and married her.

Write this one from Ariadne’s point of view. It is usually taken for granted that Ariadne fell in love with brave Theseus and wanted him to take her away and marry her. Write it as though she used him to get out and arranged for him to leave her on Naxos so she could live out her own life.

9) Cassandra

The story of Cassandra is a tragedy through and through. Cassandra was the daughter of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy and a priestess of Apollo. She was given the gift of prophesy by Apollo in exchange for sleeping with him. When she refused he then cursed his original gift so that no one would believe her prophesies. This caused most people to believe she was mad and in some versions her father locked her up, causing her to truly become mad.

She tried many times to tell the Trojans about the impending war, the many loses, the Greek-filled horse, and the aftermath. Of course, no one believed her and she was forced to watch everything happen as she foresaw. During the sack of the city, Ajax the Lessor found her clinging to the statue of Athena in her temple. Despite rules about touching supplicants and sex in temples he raped her. Athena was so furious that she punished Ajax, his people, and the Greeks who didn’t punish him. This is what caused the storm that sent Odysseus off course.

In the end Cassandra ended up going home with Agamemnon with the spoils of war. She tried one more prophesy, telling him of their murders by his wife and brother. It naturally came true and they were both slain.

I would love to read a story about Space Cassandra. But it would also be fun to see a take where Cassandra finds a way to make people do what she wants them to do. She knows they won’t believe the truth but what if she could fashion lies that would lead them in the right direction. She could play up the madness and have all sorts of hijinx as well.

10) Hercules

This last myth is one close to my heart. I used this one as inspiration for my own current writing project. I don’t have space to do the whole thing but I’ll give the highlights.

Hercules was the son of Zeus and Alcmene. Hera was incredibly jealous and decided to ruin Hercules’ life. She made him go mad and kill his entire family. When he came to, he realized what he’d done and, even though he had been forgiven legally, sought some sort of penance. He ended up working for King Eurystheus doing a total of twelve labors.

The tasks included killing a lion whose skin could not be penetrated, cleaning the stables of immortal horses, capturing a deer sacred to Artemis, gathering a lost herd of cattle, and slaying a number of beasts. They were all designed to kill him and/or humiliate him. Hera was pulling the strings the whole time and trying to get rid of him.

Athena helped him along the way and he eventually completed all the tasks. Some traditions say that when he was done he joined Jason and the Argonauts on the quest for the golden fleece.

This time I’ll let you know how I adapted the myth. First I did a gender swap. I changed Hercules to a young woman and decided to make her a student and instead of killing her family in a magic-induced fury, she kills people at the school. I also made it take place on a system of moons, giving the story a science-fiction feel. In my version she doesn’t know who made her go mad and the series revolves around discovering this and putting a stop to it.

I could find writing prompts from Greek mythology all day. Ancient myths are great sources of writing inspiration. I gave suggestions for each of the myths I listed but you could come up with dozens of ways to customize each one. Look for the fundamental story type of the myth and then have fun with the details.

Unfortunately I couldn’t include all of the myths. Let me know in the comments what Greek myths you’d like to use for writing inspiration.

If you liked what you found here consider supporting this site on Ko-Fi.

Share this:

You May Also Like

10 Writing Prompts from Bulgarian Folklore

10 Writing Prompts from Norse Mythology

15 Writing Prompts from Lovecraft

made my day

You are a very clever person!

QuixoticQuill

That’s very kind of you. 🙂

Salvador Shunk

I am thankful that I observed this web site, precisely the right info that I was searching for! .

These are awesome prompts! You’re so creative. Hope your writing project went well.

Thank you so much! I hope you get some good use out of them. Feel free to link back to your stories if you do.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

130 Inspiring Greek Mythology Topics

Do you have to write a Greek mythology essay as a class assignment? But you are uncertain about where to begin with such a task, right? The answer is a good topic. A thoughtful topic will guide you on what to research for writing a perfect essay and more.

Speaking of which, this interesting blog post offers excellent lists of exciting Greek mythology essay topics. Something you will get by hiring a paper writing service online. So, without further ado, let’s quickly get through these lists.

Table of Contents

130 Unique and Impressive Greek Mythology Topics

Let’s begin exploring top lists of awesome myth ideas for essays from professional research paper writers trusted worldwide.

50 Unique Greek Mythology Topics

When you hear or read the term Greek mythology, words like magic, myths, and more would surely pop up in your head. Interestingly, you’ll find a lot of these terminologies in our first list of myth ideas for essays below.

- A quick comparison between different established Greek Myths.

- How fate plays a role in Greek Mythology Hades and Zeus.

- How has Athena evolved over the years?

- What should you know about the myth of Prometheus? Who came up as a winner in the fate vs. free will in the story of Oedipus?

- The journey of Hercules.

- What are the Greek reflections on love and vanity?

- What should you know about Medusa?

- Understanding the symbol of excellence in Greek Mythology.

- The history and family background of Persephone.

- The secret story of Pandora’s box.

- The Greek Mythology on love and loss.

- What should we know about the myth of Sisyphus?

- The hidden truth about the tale of Icarus.

- What should we know about the mysterious Greek trials?

- Understanding the myths of three fates.

- When and where the Trojan War Originated?

- Everything you need to know about the story of Perseus.

- What’s the Greek concept of threads of life?

- Things we should know about the Trojan War.

- The hidden truth in the story of Perseus.

- Greek Mythology and the power of song.

- The connection between Artemis and Apollo.

- Hidden facts in the story of Pygmalion and Galatea.

- What should we know about the journey of Odysseus?

- What is the Greek concept of the God of Ecstasy?

- Things you don’t know about the story of Pyramus and Thisble.

- The cycle of life and death in Greek Mythology.

- Things you don’t know about the myths of Atlas.

- Greek Myths about the strength of Hercules.

- The hidden truth about the story of Achilles.

- What should we know about Eros and Psyche’s love story?

- Oracle and its role in Greek Society.

- Things you should know about the story of Arachne.

- The differences between Titans and Olympians.

- The Legend of the Minotaur.

- Unveiling the myth of Europa and the Bull.

- What was the catalyst for the Trojan War?

- Things you should know about the Myth of Actaeon.

- The Story of Atalanta.

- The secret of the tale of Daedalus and Icarus.

- What was the importance of Hermes?

- The myth of Arion.

- The Myth of Bellerophon and Pegasus.

- The Cult of Dionysus.

- The untold story of Argonauts and Jason.

- The hidden truth about the underworld of Greek Mythology.

- The legends of King Midas.

- Things you should know about the story of the psyche.

- The symbolism and myths of the Hydra.

50 Greek Mythology Essay Topics Related to Greek Heroes

More or less writing a Mythology essay takes the same format as any other essay. So, it’s not a bad idea to read some tips on essay format before you read another list of Greek mythology ideas for an essay.

- The Legends of Heracles (Hercules).

- Is Achilles the greatest Greek hero?

- Things people don’t know about the

- Hero of Argos.

- The heroes of Athens. Is Odysseus the most cunning hero?

- Was Jason the leader of the Argonauts?

- The famous Swift-Footed Huntress of Greek Mythology.

- The Legends of Bellerophon.

- Is Orpheus the legendary Greek musician?

- Who were the Gemini twins of Greek Mythology?

- Things you should know about the brave warriors of Diomedes.

- Who was Ajax the Great?

- The myths about the Amazon Queen.

- Perseus and Andromeda.

- Things you should know about Achilles.

- Ajax the Great.

- The hidden truth about Theseus and the Amazon Queen love story.

- Love, Peril, and Heroic Rescue in Greek Mythology.

- Friendship and Tragedy in Greek Mythology.

- The Tragic Hero of Greek Mythology.

- The noble Trojan Prince.

- Orpheus and the Underworld.

- The Funeral Games in Greek Mythology.

- Theseus and the Minotaur.

- Things we should know about the Heracles and the Hydra.

- A Hero’s quest for justice in Greek Mythology.

- Who were Jason and Medea?

- What should you know about the Castor of Greek Mythology?

- The Hero’s Marriage to the Amazon Queen.

- Hercules’ Battle with the Son of Earth

- The Greek myth of a hero’s encounter with enchantment

- Heroism in the face of sea monsters.

- The Hero’s Trials in the Greek Underworld.

- Heracles and the Nemean Lion.

- The Hero’s Struggle Against Temptation in Greek Mythology.

- The hidden truth of the heroic duel of the Trojan War

- What should you know about Theseus and Procrustes?

- The Hero’s Battle with Sea Monsters.

- The legends of Heracles and the Atlas.

- Theseus and the Marathonian Bull.

- The Myth of Hero’s Escape from the Cyclops.

- Hidden truth about Perseus and the Graeae.

- Heracles and the Golden Apples of the Hesperides.

- What should we know about the Theseus and the Crommyonian Sow?

- The myths of the hero’s encounter with the Amazon Warrior Queen.

- Things you should know about the hero’s Interactions with the Titan.

- The myth of Hero’s quest for the Girdle of the Amazon Queen.

- The Truth of Hero’s Political Triumph in Athens.

- Odysseus and the Lotus Eaters.

- The Myths of Hero’s Participation in the Hunt

30 Greek Mythology Topics Related to Greek Love

Still couldn’t find a topic to begin writing your essay on? Don’t worry you have 30 more Greek mythology ideas here:

- The tales of love in Greek Mythology.

- Things you should know about the love stories of Aphrodite.

- The Complexities of Divine Marital Love.

- Love, loss, and the power of music in Greek Mythology.

- The secrets of the tragic romance of Pyramus and Thisbe.

- The Love Triangle of Helen, Paris, and Menelaus.

- What should you know about Cupid and Psyche?

- The Unrequited Love Stories in Greek Mythology.

- Love in the Greek mythology underworld.

- A Forbidden love among the stars.

- The Myth of Endymion and Selene in Greek Mythology.

- The Truth of the Love of Demeter and Iasion

- The Legend of Leander and Hero.

- Romance in Nature and Greek Mythology.

- The Tale of Alcyone and Ceyx.

- Friendship or Romantic Love concepts in Greek Mythology?

- The Love Affairs of Zeus.

- The Tragic Tales of Unrequited Love in Greek Mythology.

- The Love of Ariadne and Dionysus.

- The Romance of Perseus and Andromeda.

- The Tragic Consequences of Divine Love in Greek Mythology.

- A Story of Unfulfilled Passion in Greek Mythology.

- The Love Stories of Poseidon.

- The Myth of Iphis and Ianthe.

- The Love Adventures of Hermes.

- The Love Affair of Ares and Aphrodite.

- The Tragic Love of Phaedra and Hippolytus.

- The Romance of Atalanta and Hippomenes.

- The Love Stories of the Muses.

- The Myth of Pygmalion and Galatea.

Final Thoughts On Greek Mythology Topics

Finding a good topic for writing an awesome Greek Mythology essay can be challenging for students. That’s why we thought to offer them help with lists of interesting Greek mythology research topics they can count on.

Above all, writing a Greek mythology essay is not different from other essay writing tasks. The success of this depends on a perfect structure, research, and more.

Hopefully, you have now shortlisted some topics. If you are still confused, don’t forget to count on the skills of our expert writers.

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Try Our Free Paper Writing Service

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

<strong data-cart-timer="" role="text"></strong>

Flickr user Larry Wentzel, Creative Commons

- English & Literature

Writing Creation Myths How can creation myths explain nature and science?

In this 6-8 lesson, students will explore how creation myths provide explanations for nature and science. They engage in an adjectives writing exercise and listen to digital creation myth stories. Students will plan and write original myths, then retell them through a form of media.

Get Printable Version Copy to Google Drive

Lesson Content

- Preparation

- Instruction

Learning Objectives

Students will:

- Analyze how adjectives are used to help readers visualize.

- Discuss how creation myths provide explanations for nature and science.

- Read and analyze a creation myth.

- Write an original myth using the writing process.

- Retell a creation myth story through a form of media.

Standards Alignment

National Core Arts Standards National Core Arts Standards

MA:Cr2.1.6 Form, share, and test ideas, plans, and models to prepare for media arts productions.

MA:Cr2.1.7 Discuss, test, and assemble ideas, plans, and models for media arts productions, considering the artistic goals and the presentation.

MA:Cr2.1.8 Generate ideas, goals, and solutions for original media artworks through application of focused creative processes, such as divergent thinking and experimenting.

Common Core State Standards Common Core State Standards

ELA-LITERACY.W.6.3 Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, relevant descriptive details, and well-structured event sequences.

ELA-LITERACY.W.7.3 Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, relevant descriptive details, and well-structured event sequences.

expectations for writing types are defined in standards 1-3 above.)

ELA-LITERACY.W.8.3 Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, relevant descriptive details, and well-structured event sequences.

Recommended Student Materials

Editable Documents : Before sharing these resources with students, you must first save them to your Google account by opening them, and selecting “Make a copy” from the File menu. Check out Sharing Tips or Instructional Benefits when implementing Google Docs and Google Slides with students.

- Creation Myths: Writing Exercise

- Vocabulary: A World of Myths

- Writing Myths Planner

- The Taino Myth of the Cursed Creator

- The Cambodian Myth of Lightning, Thunder, and Rain

- The Irish myth of the Giant's Causeway

Teacher Background

Build student background knowledge about creation myths with the lesson, A World of Myths . Teachers should familiarize themselves with the creation myth videos prior to teaching the lesson.

Student Prerequisites

Students should have some knowledge of myths, basic story elements, and the writing process.

Accessibility Notes

Modify handouts and give preferential seating for visual presentations. Allow extra time for task completion.

- Have students number a sheet of paper 1-10. Explain that you will state 10 objects. For each object named, they should write the color or colors associated with the object. Encourage specificity. Remind students that colors come in many shades. Mauve, puce, cat's eye green, and banana yellow are examples. List of objects: r aindrops, ocean, sun, hair, rainbow, house, horse, tree, cloud, and mountain.

- Have students turn and talk with their peers to discuss their color choices. Encourage a few students to share their color explanations with the class.

- Engage students in a discussion. How do adjectives, such as colors, change the way people think about someone or something? What would happen if every raindrop was a different color? What if the ocean was orange? What if the sun was adorable? What if you could grow tasty hair? What if every living creature was clumsy? What if everything in our world was gray? What if rainbows were creepy?

- Distribute the Creation Myths: Writing Exercise . Tell students they are going to stretch their imaginations with a writing exercise. Students will complete the story template using wild, imaginative, and untypical adjectives to describe typical things.

- Have a few student volunteers share their stories. As a student reads, have the other students close their eyes to envision the magical story. Follow-up with a discussion about how the adjectives impacted their visualizations.

- Explain to students that creation myths are stories that people told long ago to answer serious questions about how important things began and occurred. Myths employ fantastic mysterious and magical elements. Review the Vocabulary: A World of Myths . Review and discuss the terms with students.

- Watch and discuss the myth, The Taino Myth of the Cursed Creator . Ask students: What words or phrases stood out to you? What do you notice about the author's use of language? How was the ocean created?

- Divide students into pairs to listen to a different creation myth. Share the listening options below. As they listen, ask them to analyze the imaginative elements of the myth and how adjectives inform their visualizations.

The Cambodian Myth of Lightning, Thunder, and Rain - a creation myth explaining the origin of lightning, thunder, and rain according to the Khmer people.

The Irish myth of the Giant's Causeway - a creation myth explaining how the coast of Northern Ireland’s plateau of basalt slabs and columns were created according to the Ancient Irish.

- Allow students time to listen to the stories and discuss the creation myths with their peers. Have students discuss the following elements:

- Setting/Origin

- Characters

- Natural Event

- Divide students into small groups. Give each group chart paper and ask them to brainstorm a list of natural or human creations they think are interesting (i.e., a mountain, the Washington Monument, the Grand Canyon, the Great Wall of China, a redwood tree, giraffes long necks, tornadoes, etc.). Facilitate through the groups discussing their ideas.

- Distribute the Writing Myths Planner . Tell students they are going to use their brainstorm or one of the ideas from the planner to write an original creation myth. Students can collaborate in their small groups, with a partner, or write independently. Review the planner with students and model how to plan creation myth story elements.

- Write a creation myth. Allow time for students to work through the writing process, writing their creation myths using the planner. Encourage students to use adjectives to make the story interesting, allowing readers to visualize common things in a different way. Confer and provide feedback to students.

Reflect

- Have students select a way to share the creation myths they wrote. By choosing one of the following options, they will detail how a natural or human-made thing came to be. Students should rehearse several times before recording their story.

- Audiobook

- Have students share their myths with the class. Teachers can curate a sharing page in Google Classroom, Padlet, or on a class blog.

- Assess students’ knowledge of writing creation myths. Students should be able to explain how a natural or human-made thing came to be by including a setting/origin, characters, a natural event, a problem, and a solution.

Andria Cole

Original Writer

JoDee Scissors

April 27, 2023

Related Resources

Lesson a world of myths.

In this 6-8 lesson, students will explore how myths help to explain nature and science. Students will read, discuss, and draw comparisons between creation myths and explanatory myths. They will then create a drawing or illustration to represent one of those myths.

- World Cultures

- Myths, Legends, & Folktales

Lesson Writing Fables

In this 6-8 lesson, students will engage in the writing process to create original fables and perform a skit. They will review the elements of a fable and develop an understanding of how to create a centralized focus in a narrative.

- Literary Arts

Lesson Writing Folktales

In this 6-8 lesson, students will analyze the characteristics of traditional folktales to write an original tale. They will use elements of folktales to develop their story and strengthen work through the writing process.

Lesson Sci-Fi & Fantasy Worldbuilding

In this 6-8 lesson, students will explore the intersection of science fiction and fantasy from the works of Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time Trilogy. Students will create an original character, thing, ability, and/or place using worldbuilding elements. Students will choose between dramatizing, making a book trailer, or creating an illustration to introduce their imaginary world.

- Fiction & Creative Writing

Article Get Your Write On

Writing can involve reading works that fire up your imagination or finding inspiration by connecting with people. Here are a handful of online resources to help you get your write on.

Article Stories Brought to Life

Learn about ways to increase student participation and skill building during interactive read-alouds.

- Arts Integration

Article Arts in the 21st Century Classroom

The skills our students need can be readily integrated into arts lessons and vice versa.

Article Do Tell: Giving Feedback to Your Students

How can arts educators provide engaging and useful feedback? Here are seven suggestions to get you started.

Kennedy Center Education Digital Learning

Eric Friedman Director, Digital Learning

Kenny Neal Manager, Digital Education Resources

Tiffany A. Bryant Manager, Operations and Audience Engagement

Joanna McKee Program Coordinator, Digital Learning

JoDee Scissors Content Specialist, Digital Learning

Connect with us!

Generous support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. The content of these programs may have been developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education but does not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. You should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Gifts and grants to educational programs at the Kennedy Center are provided by A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; Annenberg Foundation; the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Bank of America; Bender Foundation, Inc.; Carter and Melissa Cafritz Trust; Carnegie Corporation of New York; DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities; Estée Lauder; Exelon; Flocabulary; Harman Family Foundation; The Hearst Foundations; the Herb Alpert Foundation; the Howard and Geraldine Polinger Family Foundation; William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; the Kimsey Endowment; The King-White Family Foundation and Dr. J. Douglas White; Laird Norton Family Foundation; Little Kids Rock; Lois and Richard England Family Foundation; Dr. Gary Mather and Ms. Christina Co Mather; Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation; The Morningstar Foundation;

The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Music Theatre International; Myra and Leura Younker Endowment Fund; the National Endowment for the Arts; Newman’s Own Foundation; Nordstrom; Park Foundation, Inc.; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; The Irene Pollin Audience Development and Community Engagement Initiatives; Prince Charitable Trusts; Soundtrap; The Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust; Rosemary Kennedy Education Fund; The Embassy of the United Arab Emirates; UnitedHealth Group; The Victory Foundation; The Volgenau Foundation; Volkswagen Group of America; Dennis & Phyllis Washington; and Wells Fargo. Additional support is provided by the National Committee for the Performing Arts.

Social perspectives and language used to describe diverse cultures, identities, experiences, and historical context or significance may have changed since this resource was produced. Kennedy Center Education is committed to reviewing and updating our content to address these changes. If you have specific feedback, recommendations, or concerns, please contact us at [email protected] .

By using this site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions which describe our use of cookies.

Reserve Tickets

Review cart.

You have 0 items in your cart.

Your cart is empty.

Keep Exploring Proceed to Cart & Checkout

Donate Today

Support the performing arts with your donation.

To join or renew as a Member, please visit our Membership page .

To make a donation in memory of someone, please visit our Memorial Donation page .

- Custom Other

- Writing Prompts

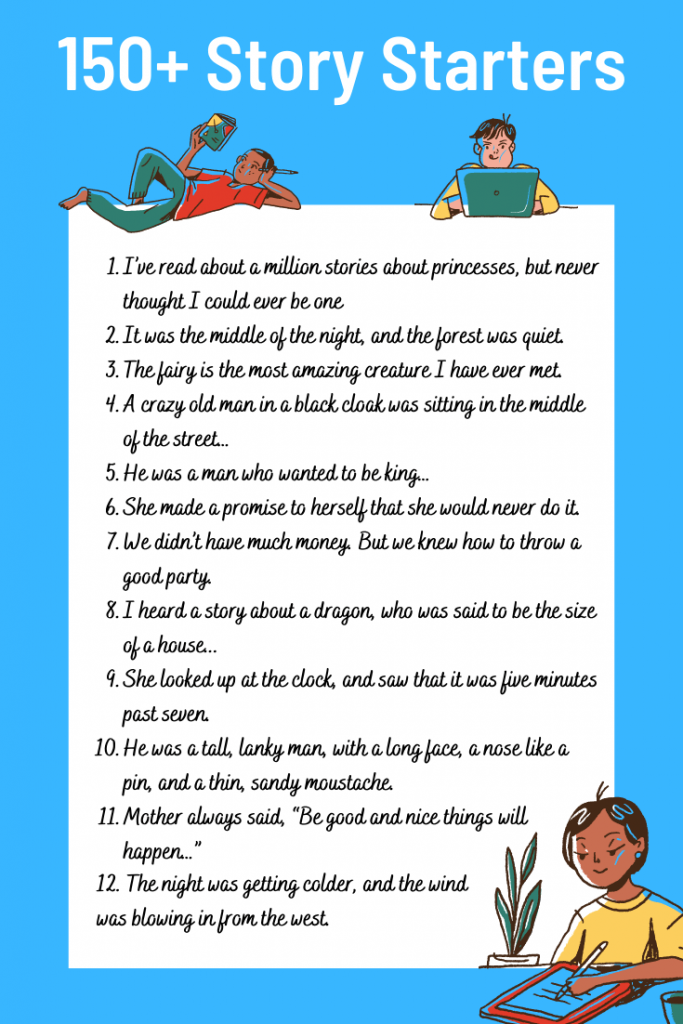

150+ Story Starters: Creative Sentences To Start A Story

The most important thing about writing is finding a good idea . You have to have a great idea to write a story. You have to be able to see the whole picture before you can start to write it. Sometimes, you might need help with that. Story starters are a great way to get the story rolling. You can use them to kick off a story, start a character in a story or even start a scene in a story.

When you start writing a story, you need to have a hook. A hook can be a character or a plot device. It can also be a setting, something like “A young man came into a bar with a horse.” or a setting like “It was the summer of 1969, and there were no cell phones.” The first sentence of a story is often the hook. It can also be a premise or a situation, such as, “A strange old man in a black cloak was sitting on the train platform.”

Story starters are a way to quickly get the story going. They give the reader a place to start reading your story. Some story starters are obvious, and some are not. The best story starters are the ones that give the reader a glimpse into the story. They can be a part of a story or a part of a scene. They can be a way to show the reader the mood of a story. If you want to start a story, you can use a simple sentence. You can also use a question or an inspirational quote. In this post, we have listed over 150 story starters to get your story started with a bang! A great way to use these story starters is at the start of the Finish The Story game .

If you want more story starters, check out this video on some creative story starter sentences to use in your stories:

150+ Creative Story Starters

Here is a list of good sentences to start a story with:

- I’ve read about a million stories about princesses but never thought I could ever be one.

- There was once a man who was very old, but he was wise. He lived for a very long time, and he was very happy.

- What is the difference between a man and a cat? A cat has nine lives.

- In the middle of the night, a boy is running through the woods.

- It is the end of the world.

- He knew he was not allowed to look into the eyes of the princess, but he couldn’t help himself.

- The year is 1893. A young boy was running away from home.

- What if the Forest was actually a magical portal to another dimension, the Forest was a portal to the Otherworld?

- In the Forest, you will find a vast number of magical beings of all sorts.

- It was the middle of the night, and the forest was quiet. No bugs or animals disturbed the silence. There were no birds, no chirping.

- If you wish to stay in the Forest, you will need to follow these rules: No one shall leave the Forest. No one shall enter. No one shall take anything from the Forest.

- “It was a terrible day,” said the old man in a raspy voice.

- A cat is flying through the air, higher and higher, when it happens, and the cat doesn’t know how it got there, how it got to be in the sky.

- I was lying in the woods, and I was daydreaming.

- The Earth is a world of wonders.

- The fairy is the most amazing creature I have ever met.

- A young girl was sitting on a tree stump at the edge of a river when she noticed a magical tree growing in the water.

- My dancing rat is dressed in a jacket, a tie and glasses, which make him look like a person.

- In the darkness of the night, I am alone, but I know that I am not.

- Owls are the oldest, and most intelligent, of all birds.

- My name is Reyna, and I am a fox.

- The woman was drowning.

- One day, he was walking in the forest.

- It was a dark and stormy night…

- There was a young girl who could not sleep…

- A boy in a black cape rode on a white horse…

- A crazy old man in a black cloak was sitting in the middle of the street…

- The sun was setting on a beautiful summer day…

- The dog was restless…”

- There was a young boy in a brown coat…

- I met a young man in the woods…

- In the middle of a dark forest…

- The young girl was at home with her family…

- There was a young man who was sitting on a …

- A young man came into a bar with a horse…

- I have had a lot of bad dreams…

- He was a man who wanted to be king…

- It was the summer of 1969, and there were no cell phones.

- I know what you’re thinking. But no, I don’t want to be a vegetarian. The worst part is I don’t like the taste.

- She looked at the boy and decided to ask him why he wasn’t eating. She didn’t want to look mean, but she was going to ask him anyway.

- The song played on the radio, as Samual wiped away his tears.

- This was the part when everything was about to go downhill. But it didn’t…

- “Why make life harder for yourself?” asked Claire, as she bit into her apple.

- She made a promise to herself that she would never do it.

- I was able to escape.

- I was reading a book when the accident happened.

- “I can’t stand up for people who lie and cheat.” I cried.

- You look at me and I feel beautiful.

- I know what I want to be when I grow up.

- We didn’t have much money. But we knew how to throw a good party.

- The wind blew on the silent streets of London.

- What do you get when you cross an angry bee and my sister?

- The flight was slow and bumpy. I was half asleep when the captain announced we were going down.

- At the far end of the city was a river that was overgrown with weeds.

- It was a quiet night in the middle of a busy week.

- One afternoon, I was eating a sandwich in the park when I spotted a stranger.

- In the late afternoon, a few students sat on the lawn reading.

- The fireflies were dancing in the twilight as the sunset.

- In the early evening, the children played in the park.

- The sun was setting and the moon was rising.

- A crowd gathered in the square as the band played.

- The top of the water tower shone in the moonlight.

- The light in the living room was on, but the light in the kitchen was off.

- When I was a little boy, I used to make up stories about the adventures of these amazing animals, creatures, and so on.

- All of the sudden, I realized I was standing in the middle of an open field surrounded by nothing but wildflowers, and the only thing I remembered about it was that I’d never seen a tree before.

- It’s the kind of thing that’s only happened to me once before in my life, but it’s so cool to see it.

- They gave him a little wave as they drove away.

- The car had left the parking lot, and a few hours later we arrived home.

- They were going to play a game of bingo.

- He’d made up his mind to do it. He’d have to tell her soon, though. He was waiting for a moment when they were alone and he could say it without feeling like an idiot. But when that moment came, he couldn’t think of anything to say.

- Jamie always wanted to own a plane, but his parents were a little tight on the budget. So he’d been saving up to buy one of his own.

- The night was getting colder, and the wind was blowing in from the west.

- The doctor stared down at the small, withered corpse.

- She’d never been in the woods before, but she wasn’t afraid.

- The kids were having a great time in the playground.

- The police caught the thieves red-handed.

- The world needs a hero more than ever.

- Mother always said, “Be good and nice things will happen…”

- There is a difference between what you see and what you think you see.

- The sun was low in the sky and the air was warm.

- “It’s time to go home,” she said, “I’m getting a headache.”

- It was a cold winter’s day, and the snow had come early.

- I found a wounded bird in my garden.

- “You should have seen the look on my face.”

- He opened the door and stepped back.

- My father used to say, “All good things come to an end.”

- The problem with fast cars is that they break so easily.

- “What do you think of this one?” asked Mindy.

- “If I asked you to do something, would you do it?” asked Jacob.

- I was surprised to see her on the bus.

- I was never the most popular one in my class.

- We had a bad fight that day.

- The coffee machine had stopped working, so I went to the kitchen to make myself a cup of tea.

- It was a muggy night, and the air-conditioning unit was so loud it hurt my ears.

- I had a sleepless night because I couldn’t get my head to turn off.

- I woke up at dawn and heard a horrible noise.

- I was so tired I didn’t know if I’d be able to sleep that night.

- I put on the light and looked at myself in the mirror.

- I decided to go in, but the door was locked.

- A man in a red sweater stood staring at a little kitten as if it was on fire.

- “It’s so beautiful,” he said, “I’m going to take a picture.”

- “I think we’re lost,” he said, “It’s all your fault.”

- It’s hard to imagine what a better life might be like

- He was a tall, lanky man, with a long face, a nose like a pin, and a thin, sandy moustache.

- He had a face like a lion’s and an eye like a hawk’s.

- The man was so broad and strong that it was as if a mountain had been folded up and carried in his belly.

- I opened the door. I didn’t see her, but I knew she was there.

- I walked down the street. I couldn’t help feeling a little guilty.

- I arrived at my parents’ home at 8:00 AM.

- The nurse had been very helpful.

- On the table was an array of desserts.

- I had just finished putting the last of my books in the trunk.

- A car horn honked, startling me.

- The kitchen was full of pots and pans.

- There are too many things to remember.

- The world was my oyster. I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth.

- “My grandfather was a World War II veteran. He was a decorated hero who’d earned himself a Silver Star, a Bronze Star, and a Purple Heart.

- Beneath the menacing, skeletal shadow of the mountain, a hermit sat on his ledge. His gnarled hands folded on his gnarled knees. His eyes stared blankly into the fog.

- I heard a story about a dragon, who was said to be the size of a house, that lived on the top of the tallest mountain in the world.

- I was told a story about a man who found a golden treasure, which was buried in this very park.

- He stood alone in the middle of a dark and silent room, his head cocked to one side, the brown locks of his hair, which were parted in the middle, falling down over his eyes.

- Growing up, I was the black sheep of the family. I had my father’s eyes, but my mother’s smile.

- Once upon a time, there was a woman named Miss Muffett, and she lived in a big house with many rooms.

- When I was a child, my mother told me that the water looked so bright because the sun was shining on it. I did not understand what she meant at the time.

- The man in the boat took the water bottle and drank from it as he paddled away.

- The man looked at the child with a mixture of pity and contempt.

- An old man and his grandson sat in their garden. The old man told his grandson to dig a hole.

- An old woman was taking a walk on the beach. The tide was high and she had to wade through the water to get to the other side.

- She looked up at the clock and saw that it was five minutes past seven.

- The man looked up from the map he was studying. “How’s it going, mate?”

- I was in my room on the third floor, staring out of the window.

- A dark silhouette of a woman stood in the doorway.

- The church bells began to ring.

- The moon rose above the horizon.

- A bright light shone over the road.

- The night sky began to glow.

- I could hear my mother cooking in the kitchen.

- The fog began to roll in.

- He came in late to the class and sat at the back.

- A young boy picked up a penny and put it in his pocket.

- He went to the bathroom and looked at his face in the mirror.