- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Qualitative Data Collection: What it is + Methods to do it

Qualitative data collection is vital in qualitative research. It helps researchers understand individuals’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors in a specific context.

Several methods are used to collect qualitative data, including interviews, surveys, focus groups, and observations. Understanding the various methods used for gathering qualitative data is essential for successful qualitative research.

In this post, we will discuss qualitative data and its collection methods of it.

Content Index

What is Qualitative Data?

What is qualitative data collection, what is the need for qualitative data collection, effective qualitative data collection methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative data collection.

Qualitative data is defined as data that approximates and characterizes. It can be observed and recorded.

This data type is non-numerical in nature. This type of data is collected through methods of observations, one-to-one interviews, conducting focus groups, and similar methods.

Qualitative data in statistics is also known as categorical data – data that can be arranged categorically based on the attributes and properties of a thing or a phenomenon.

It’s pretty easy to understand the difference between qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative data does not include numbers in its definition of traits, whereas quantitative research data is all about numbers.

- The cake is orange, blue, and black in color (qualitative).

- Females have brown, black, blonde, and red hair (qualitative).

Qualitative data collection is gathering non-numerical information, such as words, images, and observations, to understand individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and motivations in a specific context. It is an approach used in qualitative research. It seeks to understand social phenomena through in-depth exploration and analysis of people’s perspectives, experiences, and narratives. In statistical analysis , distinguishing between categorical data and numerical data is essential, as categorical data involves distinct categories or labels, while numerical data consists of measurable quantities.

The data collected through qualitative methods are often subjective, open-ended, and unstructured and can provide a rich and nuanced understanding of complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research is a type of study carried out with a qualitative approach to understand the exploratory reasons and to assay how and why a specific program or phenomenon operates in the way it is working. A researcher can access numerous qualitative data collection methods that he/she feels are relevant.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

Qualitative data collection methods serve the primary purpose of collecting textual data for research and analysis , like the thematic analysis. The collected research data is used to examine:

- Knowledge around a specific issue or a program, experience of people.

- Meaning and relationships.

- Social norms and contextual or cultural practices demean people or impact a cause.

The qualitative data is textual or non-numerical. It covers mostly the images, videos, texts, and written or spoken words by the people. You can opt for any digital data collection methods , like structured or semi-structured surveys, or settle for the traditional approach comprising individual interviews, group discussions, etc.

Data at hand leads to a smooth process ensuring all the decisions made are for the business’s betterment. You will be able to make informed decisions only if you have relevant data.

Well! With quality data, you will improve the quality of decision-making. But you will also enhance the quality of the results expected from any endeavor.

Qualitative data collection methods are exploratory. Those are usually more focused on gaining insights and understanding the underlying reasons by digging deeper.

Although quantitative data cannot be quantified, measuring it or analyzing qualitative data might become an issue. Due to the lack of measurability, collection methods of qualitative data are primarily unstructured or structured in rare cases – that too to some extent.

Let’s explore the most common methods used for the collection of qualitative data:

Individual interview

It is one of the most trusted, widely used, and familiar qualitative data collection methods primarily because of its approach. An individual or face-to-face interview is a direct conversation between two people with a specific structure and purpose.

The interview questionnaire is designed in the manner to elicit the interviewee’s knowledge or perspective related to a topic, program, or issue.

At times, depending on the interviewer’s approach, the conversation can be unstructured or informal but focused on understanding the individual’s beliefs, values, understandings, feelings, experiences, and perspectives on an issue.

More often, the interviewer chooses to ask open-ended questions in individual interviews. If the interviewee selects answers from a set of given options, it becomes a structured, fixed response or a biased discussion.

The individual interview is an ideal qualitative data collection method. Particularly when the researchers want highly personalized information from the participants. The individual interview is a notable method if the interviewer decides to probe further and ask follow-up questions to gain more insights.

Qualitative surveys

To develop an informed hypothesis, many researchers use qualitative research surveys for data collection or to collect a piece of detailed information about a product or an issue. If you want to create questionnaires for collecting textual or qualitative data, then ask more open-ended questions .

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

To answer such qualitative research questions , the respondent has to write his/her opinion or perspective concerning a specific topic or issue. Unlike other collection methods, online surveys have a wider reach. People can provide you with quality data that is highly credible and valuable.

Paper surveys

Online surveys, focus group discussions.

Focus group discussions can also be considered a type of interview, but it is conducted in a group discussion setting. Usually, the focus group consists of 8 – 10 people (the size may vary depending on the researcher’s requirement). The researchers ensure appropriate space is given to the participants to discuss a topic or issue in a context. The participants are allowed to either agree or disagree with each other’s comments.

With a focused group discussion, researchers know how a particular group of participants perceives the topic. Researchers analyze what participants think of an issue, the range of opinions expressed, and the ideas discussed. The data is collected by noting down the variations or inconsistencies (if any exist) in the participants, especially in terms of belief, experiences, and practice.

The participants of focused group discussions are selected based on the topic or issues for which the researcher wants actionable insights. For example, if the research is about the recovery of college students from drug addiction. The participants have to be college students studying and recovering from drug addiction.

Other parameters such as age, qualification, financial background, social presence, and demographics are also considered, but not primarily, as the group needs diverse participants. Frequently, the qualitative data collected through focused group discussion is more descriptive and highly detailed.

Record keeping

This method uses reliable documents and other sources of information that already exist as the data source. This information can help with the new study. It’s a lot like going to the library. There, you can look through books and other sources to find information that can be used in your research.

Case studies

In this method, data is collected by looking at case studies in detail. This method’s flexibility is shown by the fact that it can be used to analyze both simple and complicated topics. This method’s strength is how well it draws conclusions from a mix of one or more qualitative data collection methods.

Observations

Observation is one of the traditional methods of qualitative data collection. It is used by researchers to gather descriptive analysis data by observing people and their behavior at events or in their natural settings. In this method, the researcher is completely immersed in watching people by taking a participatory stance to take down notes.

There are two main types of observation:

- Covert: In this method, the observer is concealed without letting anyone know that they are being observed. For example, a researcher studying the rituals of a wedding in nomadic tribes must join them as a guest and quietly see everything.

- Overt: In this method, everyone is aware that they are being watched. For example, A researcher or an observer wants to study the wedding rituals of a nomadic tribe. To proceed with the research, the observer or researcher can reveal why he is attending the marriage and even use a video camera to shoot everything around him.

Observation is a useful method of qualitative data collection, especially when you want to study the ongoing process, situation, or reactions on a specific issue related to the people being observed.

When you want to understand people’s behavior or their way of interaction in a particular community or demographic, you can rely on the observation data. Remember, if you fail to get quality data through surveys, qualitative interviews , or group discussions, rely on observation.

It is the best and most trusted collection method of qualitative data to generate qualitative data as it requires equal to no effort from the participants.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

You invested time and money acquiring your data, so analyze it. It’s necessary to avoid being in the dark after all your hard work. Qualitative data analysis starts with knowing its two basic techniques, but there are no rules.

- Deductive Approach: The deductive data analysis uses a researcher-defined structure to analyze qualitative data. This method is quick and easy when a researcher knows what the sample population will say.

- Inductive Approach: The inductive technique has no structure or framework. When a researcher knows little about the event, an inductive approach is applied.

Whether you want to analyze qualitative data from a one-on-one interview or a survey, these simple steps will ensure a comprehensive qualitative data analysis.

Step 1: Arrange your Data

After collecting all the data, it is mostly unstructured and sometimes unclear. Arranging your data is the first stage in qualitative data analysis. So, researchers must transcribe data before analyzing it.

Step 2: Organize all your Data

After transforming and arranging your data, the next step is to organize it. One of the best ways to organize the data is to think back to your research goals and then organize the data based on the research questions you asked.

Step 3: Set a Code to the Data Collected

Setting up appropriate codes for the collected data gets you one step closer. Coding is one of the most effective methods for compressing a massive amount of data. It allows you to derive theories from relevant research findings.

Step 4: Validate your Data

Qualitative data analysis success requires data validation. Data validation should be done throughout the research process, not just once. There are two sides to validating data:

- The accuracy of your research design or methods.

- Reliability—how well the approaches deliver accurate data.

Step 5: Concluding the Analysis Process

Finally, conclude your data in a presentable report. The report should describe your research methods, their pros and cons, and research limitations. Your report should include findings, inferences, and future research.

QuestionPro is a comprehensive online survey software that offers a variety of qualitative data analysis tools to help businesses and researchers in making sense of their data. Users can use many different qualitative analysis methods to learn more about their data.

Users of QuestionPro can see their data in different charts and graphs, which makes it easier to spot patterns and trends. It can help researchers and businesses learn more about their target audience, which can lead to better decisions and better results.

LEARN ABOUT: Steps in Qualitative Research

Qualitative data collection has several advantages, including:

- In-depth understanding: It provides in-depth information about attitudes and behaviors, leading to a deeper understanding of the research.

- Flexibility: The methods allow researchers to modify questions or change direction if new information emerges.

- Contextualization: Qualitative research data is in context, which helps to provide a deep understanding of the experiences and perspectives of individuals.

- Rich data: It often produces rich, detailed, and nuanced information that cannot capture through numerical data.

- Engagement: The methods, such as interviews and focus groups, involve active meetings with participants, leading to a deeper understanding.

- Multiple perspectives: This can provide various views and a rich array of voices, adding depth and complexity.

- Realistic setting: It often occurs in realistic settings, providing more authentic experiences and behaviors.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

Qualitative research is one of the best methods for identifying the behavior and patterns governing social conditions, issues, or topics. It spans a step ahead of quantitative data as it fails to explain the reasons and rationale behind a phenomenon, but qualitative data quickly does.

Qualitative research is one of the best tools to identify behaviors and patterns governing social conditions. It goes a step beyond quantitative data by providing the reasons and rationale behind a phenomenon that cannot be explored quantitatively.

With QuestionPro, you can use it for qualitative data collection through various methods. Using Our robust suite correctly, you can enhance the quality and integrity of the collected data.

FREE TRIAL LEARN MORE

MORE LIKE THIS

Data Information vs Insight: Essential differences

May 14, 2024

Pricing Analytics Software: Optimize Your Pricing Strategy

May 13, 2024

Relationship Marketing: What It Is, Examples & Top 7 Benefits

May 8, 2024

The Best Email Survey Tool to Boost Your Feedback Game

May 7, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Chapter 10. Introduction to Data Collection Techniques

Introduction.

Now that we have discussed various aspects of qualitative research, we can begin to collect data. This chapter serves as a bridge between the first half and second half of this textbook (and perhaps your course) by introducing techniques of data collection. You’ve already been introduced to some of this because qualitative research is often characterized by the form of data collection; for example, an ethnographic study is one that employs primarily observational data collection for the purpose of documenting and presenting a particular culture or ethnos. Thus, some of this chapter will operate as a review of material already covered, but we will be approaching it from the data-collection side rather than the tradition-of-inquiry side we explored in chapters 2 and 4.

Revisiting Approaches

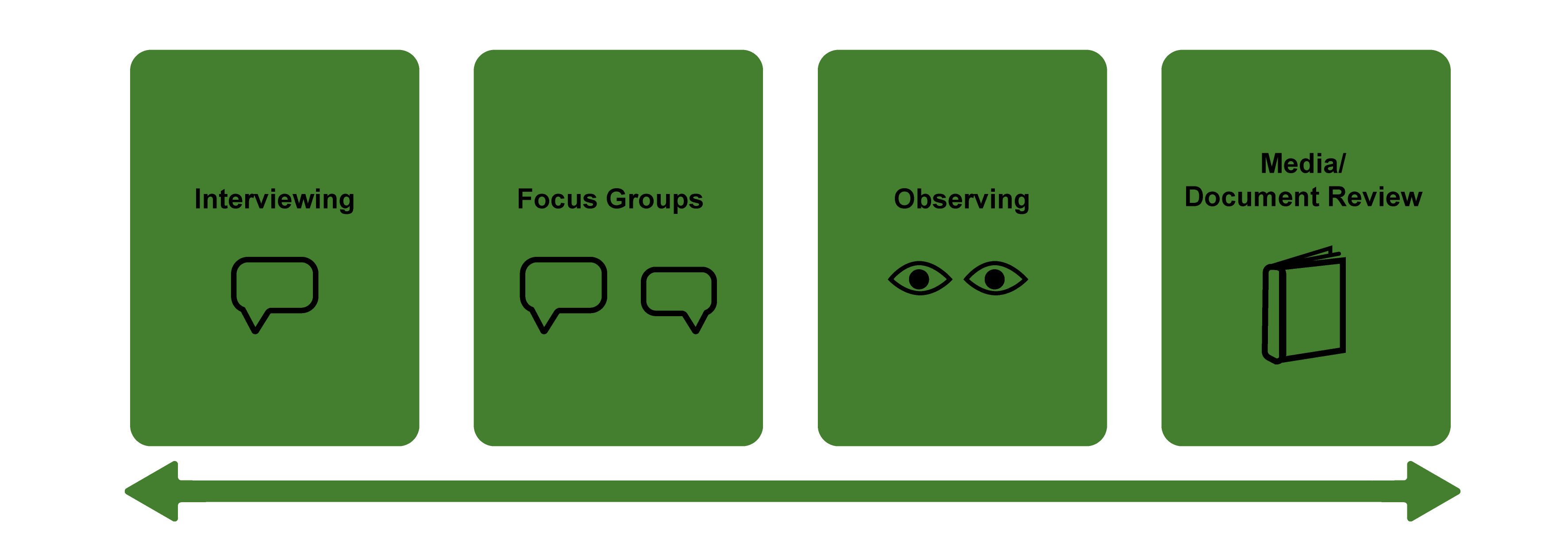

There are four primary techniques of data collection used in qualitative research: interviews, focus groups, observations, and document review. [1] There are other available techniques, such as visual analysis (e.g., photo elicitation) and biography (e.g., autoethnography) that are sometimes used independently or supplementarily to one of the main forms. Not to confuse you unduly, but these various data collection techniques are employed differently by different qualitative research traditions so that sometimes the technique and the tradition become inextricably entwined. This is largely the case with observations and ethnography. The ethnographic tradition is fundamentally based on observational techniques. At the same time, traditions other than ethnography also employ observational techniques, so it is worthwhile thinking of “tradition” and “technique” separately (see figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1. Data Collection Techniques

Each of these data collection techniques will be the subject of its own chapter in the second half of this textbook. This chapter serves as an orienting overview and as the bridge between the conceptual/design portion of qualitative research and the actual practice of conducting qualitative research.

Overview of the Four Primary Approaches

Interviews are at the heart of qualitative research. Returning to epistemological foundations, it is during the interview that the researcher truly opens herself to hearing what others have to say, encouraging her interview subjects to reflect deeply on the meanings and values they hold. Interviews are used in almost every qualitative tradition but are particularly salient in phenomenological studies, studies seeking to understand the meaning of people’s lived experiences.

Focus groups can be seen as a type of interview, one in which a group of persons (ideally between five and twelve) is asked a series of questions focused on a particular topic or subject. They are sometimes used as the primary form of data collection, especially outside academic research. For example, businesses often employ focus groups to determine if a particular product is likely to sell. Among qualitative researchers, it is often used in conjunction with any other primary data collection technique as a form of “triangulation,” or a way of increasing the reliability of the study by getting at the object of study from multiple directions. [2] Some traditions, such as feminist approaches, also see the focus group as an important “consciousness-raising” tool.

If interviews are at the heart of qualitative research, observations are its lifeblood. Researchers who are more interested in the practices and behaviors of people than what they think or who are trying to understand the parameters of an organizational culture rely on observations as their primary form of data collection. The notes they make “in the field” (either during observations or afterward) form the “data” that will be analyzed. Ethnographers, those seeking to describe a particular ethnos, or culture, believe that observations are more reliable guides to that culture than what people have to say about it. Observations are thus the primary form of data collection for ethnographers, albeit often supplemented with in-depth interviews.

Some would say that these three—interviews, focus groups, and observations—are really the foundational techniques of data collection. They are far and away the three techniques most frequently used separately, in conjunction with one another, and even sometimes in mixed methods qualitative/quantitative studies. Document review, either as a form of content analysis or separately, however, is an important addition to the qualitative researcher’s toolkit and should not be overlooked (figure 10.1). Although it is rare for a qualitative researcher to make document review their primary or sole form of data collection, including documents in the research design can help expand the reach and the reliability of a study. Document review can take many forms, from historical and archival research, in which the researcher pieces together a narrative of the past by finding and analyzing a variety of “documents” and records (including photographs and physical artifacts), to analyses of contemporary media content, as in the case of compiling and coding blog posts or other online commentaries, and content analysis that identifies and describes communicative aspects of media or documents.

In addition to these four major techniques, there are a host of emerging and incidental data collection techniques, from photo elicitation or photo voice, in which respondents are asked to comment upon a photograph or image (particularly useful as a supplement to interviews when the respondents are hesitant or unable to answer direct questions), to autoethnographies, in which the researcher uses his own position and life to increase our understanding about a phenomenon and its historical and social context.

Taken together, these techniques provide a wide range of practices and tools with which to discover the world. They are particularly suited to addressing the questions that qualitative researchers ask—questions about how things happen and why people act the way they do, given particular social contexts and shared meanings about the world (chapter 4).

Triangulation and Mixed Methods

Because the researcher plays such a large and nonneutral role in qualitative research, one that requires constant reflectivity and awareness (chapter 6), there is a constant need to reassure her audience that the results she finds are reliable. Quantitative researchers can point to any number of measures of statistical significance to reassure their audiences, but qualitative researchers do not have math to hide behind. And she will also want to reassure herself that what she is hearing in her interviews or observing in the field is a true reflection of what is going on (or as “true” as possible, given the problem that the world is as large and varied as the elephant; see chapter 3). For those reasons, it is common for researchers to employ more than one data collection technique or to include multiple and comparative populations, settings, and samples in the research design (chapter 2). A single set of interviews or initial comparison of focus groups might be conceived as a “pilot study” from which to launch the actual study. Undergraduate students working on a research project might be advised to think about their projects in this way as well. You are simply not going to have enough time or resources as an undergraduate to construct and complete a successful qualitative research project, but you may be able to tackle a pilot study. Graduate students also need to think about the amount of time and resources they have for completing a full study. Masters-level students, or students who have one year or less in which to complete a program, should probably consider their study as an initial exploratory pilot. PhD candidates might have the time and resources to devote to the type of triangulated, multifaceted research design called for by the research question.

We call the use of multiple qualitative methods of data collection and the inclusion of multiple and comparative populations and settings “triangulation.” Using different data collection methods allows us to check the consistency of our findings. For example, a study of the vaccine hesitant might include a set of interviews with vaccine-hesitant people and a focus group of the same and a content analysis of online comments about a vaccine mandate. By employing all three methods, we can be more confident of our interpretations from the interviews alone (especially if we are hearing the same thing throughout; if we are not, then this is a good sign that we need to push a little further to find out what is really going on). [3] Methodological triangulation is an important tool for increasing the reliability of our findings and the overall success of our research.

Methodological triangulation should not be confused with mixed methods techniques, which refer instead to the combining of qualitative and quantitative research methods. Mixed methods studies can increase reliability, but that is not their primary purpose. Mixed methods address multiple research questions, both the “how many” and “why” kind, or the causal and explanatory kind. Mixed methods will be discussed in more detail in chapter 15.

Let us return to the three examples of qualitative research described in chapter 1: Cory Abramson’s study of aging ( The End Game) , Jennifer Pierce’s study of lawyers and discrimination ( Racing for Innocence ), and my own study of liberal arts college students ( Amplified Advantage ). Each of these studies uses triangulation.

Abramson’s book is primarily based on three years of observations in four distinct neighborhoods. He chose the neighborhoods in such a way to maximize his ability to make comparisons: two were primarily middle class and two were primarily poor; further, within each set, one was predominantly White, while the other was either racially diverse or primarily African American. In each neighborhood, he was present in senior centers, doctors’ offices, public transportation, and other public spots where the elderly congregated. [4] The observations are the core of the book, and they are richly written and described in very moving passages. But it wasn’t enough for him to watch the seniors. He also engaged with them in casual conversation. That, too, is part of fieldwork. He sometimes even helped them make it to the doctor’s office or get around town. Going beyond these interactions, he also interviewed sixty seniors, an equal amount from each of the four neighborhoods. It was in the interviews that he could ask more detailed questions about their lives, what they thought about aging, what it meant to them to be considered old, and what their hopes and frustrations were. He could see that those living in the poor neighborhoods had a more difficult time accessing care and resources than those living in the more affluent neighborhoods, but he couldn’t know how the seniors understood these difficulties without interviewing them. Both forms of data collection supported each other and helped make the study richer and more insightful. Interviews alone would have failed to demonstrate the very real differences he observed (and that some seniors would not even have known about). This is the value of methodological triangulation.

Pierce’s book relies on two separate forms of data collection—interviews with lawyers at a firm that has experienced a history of racial discrimination and content analyses of news stories and popular films that screened during the same years of the alleged racial discrimination. I’ve used this book when teaching methods and have often found students struggle with understanding why these two forms of data collection were used. I think this is because we don’t teach students to appreciate or recognize “popular films” as a legitimate form of data. But what Pierce does is interesting and insightful in the best tradition of qualitative research. Here is a description of the content analyses from a review of her book:

In the chapter on the news media, Professor Pierce uses content analysis to argue that the media not only helped shape the meaning of affirmative action, but also helped create white males as a class of victims. The overall narrative that emerged from these media accounts was one of white male innocence and victimization. She also maintains that this narrative was used to support “neoconservative and neoliberal political agendas” (p. 21). The focus of these articles tended to be that affirmative action hurt white working-class and middle-class men particularly during the recession in the 1980s (despite statistical evidence that people of color were hurt far more than white males by the recession). In these stories fairness and innocence were seen in purely individual terms. Although there were stories that supported affirmative action and developed a broader understanding of fairness, the total number of stories slanted against affirmative action from 1990 to 1999. During that time period negative stories always outnumbered those supporting the policy, usually by a ratio of 3:1 or 3:2. Headlines, the presentation of polling data, and an emphasis in stories on racial division, Pierce argues, reinforced the story of white male victimization. Interestingly, the news media did very few stories on gender and affirmative action. The chapter on the film industry from 1989 to 1999 reinforces Pierce’s argument and adds another layer to her interpretation of affirmative action during this time period. She sampled almost 60 Hollywood films with receipts ranging from four million to 184 million dollars. In this chapter she argues that the dominant theme of these films was racial progress and the redemption of white Americans from past racism. These movies usually portrayed white, elite, and male experiences. People of color were background figures who supported the protagonist and “anointed” him as a savior (p. 45). Over the course of the film the protagonists move from “innocence to consciousness” concerning racism. The antagonists in these films most often were racist working-class white men. A Time to Kill , Mississippi Burning , Amistad , Ghosts of Mississippi , The Long Walk Home , To Kill a Mockingbird , and Dances with Wolves receive particular analysis in this chapter, and her examination of them leads Pierce to conclude that they infused a myth of racial progress into America’s cultural memory. White experiences of race are the focus and contemporary forms of racism are underplayed or omitted. Further, these films stereotype both working-class and elite white males, and underscore the neoliberal emphasis on individualism. ( Hrezo 2012 )

With that context in place, Pierce then turned to interviews with attorneys. She finds that White male attorneys often misremembered facts about the period in which the law firm was accused of racial discrimination and that they often portrayed their firms as having made substantial racial progress. This was in contrast to many of the lawyers of color and female lawyers who remembered the history differently and who saw continuing examples of racial (and gender) discrimination at the law firm. In most of the interviews, people talked about individuals, not structure (and these are attorneys, who really should know better!). By including both content analyses and interviews in her study, Pierce is better able to situate the attorney narratives and explain the larger context for the shared meanings of individual innocence and racial progress. Had this been a study only of films during this period, we would not know how actual people who lived during this period understood the decisions they made; had we had only the interviews, we would have missed the historical context and seen a lot of these interviewees as, well, not very nice people at all. Together, we have a study that is original, inventive, and insightful.

My own study of how class background affects the experiences and outcomes of students at small liberal arts colleges relies on mixed methods and triangulation. At the core of the book is an original survey of college students across the US. From analyses of this survey, I can present findings on “how many” questions and descriptive statistics comparing students of different social class backgrounds. For example, I know and can demonstrate that working-class college students are less likely to go to graduate school after college than upper-class college students are. I can even give you some estimates of the class gap. But what I can’t tell you from the survey is exactly why this is so or how it came to be so . For that, I employ interviews, focus groups, document reviews, and observations. Basically, I threw the kitchen sink at the “problem” of class reproduction and higher education (i.e., Does college reduce class inequalities or make them worse?). A review of historical documents provides a picture of the place of the small liberal arts college in the broader social and historical context. Who had access to these colleges and for what purpose have always been in contest, with some groups attempting to exclude others from opportunities for advancement. What it means to choose a small liberal arts college in the early twenty-first century is thus different for those whose parents are college professors, for those whose parents have a great deal of money, and for those who are the first in their family to attend college. I was able to get at these different understandings through interviews and focus groups and to further delineate the culture of these colleges by careful observation (and my own participation in them, as both former student and current professor). Putting together individual meanings, student dispositions, organizational culture, and historical context allowed me to present a story of how exactly colleges can both help advance first-generation, low-income, working-class college students and simultaneously amplify the preexisting advantages of their peers. Mixed methods addressed multiple research questions, while triangulation allowed for this deeper, more complex story to emerge.

In the next few chapters, we will explore each of the primary data collection techniques in much more detail. As we do so, think about how these techniques may be productively joined for more reliable and deeper studies of the social world.

Advanced Reading: Triangulation

Denzin ( 1978 ) identified four basic types of triangulation: data, investigator, theory, and methodological. Properly speaking, if we use the Denzin typology, the use of multiple methods of data collection and analysis to strengthen one’s study is really a form of methodological triangulation. It may be helpful to understand how this differs from the other types.

Data triangulation occurs when the researcher uses a variety of sources in a single study. Perhaps they are interviewing multiple samples of college students. Obviously, this overlaps with sample selection (see chapter 5). It is helpful for the researcher to understand that these multiple data sources add strength and reliability to the study. After all, it is not just “these students here” but also “those students over there” that are experiencing this phenomenon in a particular way.

Investigator triangulation occurs when different researchers or evaluators are part of the research team. Intercoding reliability is a form of investigator triangulation (or at least a way of leveraging the power of multiple researchers to raise the reliability of the study).

Theory triangulation is the use of multiple perspectives to interpret a single set of data, as in the case of competing theoretical paradigms (e.g., a human capital approach vs. a Bourdieusian multiple capital approach).

Methodological triangulation , as explained in this chapter, is the use of multiple methods to study a single phenomenon, issue, or problem.

Further Readings

Carter, Nancy, Denise Bryant-Lukosius, Alba DiCenso, Jennifer Blythe, Alan J. Neville. 2014. “The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research.” Oncology Nursing Forum 41(5):545–547. Discusses the four types of triangulation identified by Denzin with an example of the use of focus groups and in-depth individuals.

Mathison, Sandra. 1988. “Why Triangulate?” Educational Researcher 17(2):13–17. Presents three particular ways of assessing validity through the use of triangulated data collection: convergence, inconsistency, and contradiction.

Tracy, Sarah J. 2010. “Qualitative Quality: Eight ‘Big-Tent’ Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 16(10):837–851. Focuses on triangulation as a criterion for conducting valid qualitative research.

- Marshall and Rossman ( 2016 ) state this slightly differently. They list four primary methods for gathering information: (1) participating in the setting, (2) observing directly, (3) interviewing in depth, and (4) analyzing documents and material culture (141). An astute reader will note that I have collapsed participation into observation and that I have distinguished focus groups from interviews. I suspect that this distinction marks me as more of an interview-based researcher, while Marshall and Rossman prioritize ethnographic approaches. The main point of this footnote is to show you, the reader, that there is no single agreed-upon number of approaches to collecting qualitative data. ↵

- See “ Advanced Reading: Triangulation ” at end of this chapter. ↵

- We can also think about triangulating the sources, as when we include comparison groups in our sample (e.g., if we include those receiving vaccines, we might find out a bit more about where the real differences lie between them and the vaccine hesitant); triangulating the analysts (building a research team so that your interpretations can be checked against those of others on the team); and even triangulating the theoretical perspective (as when we “try on,” say, different conceptualizations of social capital in our analyses). ↵

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

8 Essential Qualitative Data Collection Methods

Qualitative data methods allow you to deep dive into the mindset of your audience to discover areas for growth, development, and improvement.

British mathematician and marketing mastermind Clive Humby once famously stated that “Data is the new oil.” He has a point. Without data, nonprofit organizations are left second-guessing what their clients and supporters think, how their brand compares to others in the market, whether their messaging is on-point, how their campaigns are performing, where improvements can be made, and how overall results can be optimized.

There are two primary data collection methodologies: qualitative data collection and quantitative data collection. At UpMetrics, we believe that relying on quantitative, static data is no longer an option to drive effective impact. In the nonprofit sector, where financial gain is not the sole purpose of your organization’s existence. In this guide, we’ll focus on qualitative data collection methods and how they can help you gather, analyze, and collate information that can help drive your organization forward.

What is Qualitative Data?

Data collection in qualitative research focuses on gathering contextual information. Unlike quantitative data, which focuses primarily on numbers to establish ‘how many’ or ‘how much,’ qualitative data collection tools allow you to assess the ‘why’s’ and ‘how’s’ behind those statistics. This is vital for nonprofits as it enables organizations to determine:

- Existing knowledge surrounding a particular issue.

- How social norms and cultural practices impact a cause.

- What kind of experiences and interactions people have with your brand.

- Trends in the way people change their opinions.

- Whether meaningful relationships are being established between all parties.

In short, qualitative data collection methods collect perceptual and descriptive information that helps you understand the reasoning and motivation behind particular reactions and behaviors. For that reason, qualitative data methods are usually non-numerical and center around spoken and written words rather than data extrapolated from a spreadsheet or report.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Data

Quantitative and qualitative data represent both sides of the same coin. There will always be some degree of debate over the importance of quantitative vs. qualitative research, data, and collection. However, successful organizations should strive to achieve a balance between the two.

Organizations can track their performance by collecting quantitative data based on metrics including dollars raised, membership growth, number of people served, overhead costs, etc. This is all essential information to have. However, the data lacks value without the additional details provided by qualitative research because it doesn’t tell you anything about how your target audience thinks, feels, and acts.

Qualitative data collection is particularly relevant in the nonprofit sector as the relationships people have with the causes they support are fundamentally personal and cannot be expressed numerically. Qualitative data methods allow you to deep dive into the mindset of your audience to discover areas for growth, development, and improvement.

8 Types of Qualitative Data Collection Methods

As we have firmly established the need for qualitative data, it’s time to answer the next big question: how to collect qualitative data.

Here is a list of the most common qualitative data collection methods. You don’t need to use them all in your quest for gathering information. However, a foundational understanding of each will help you refine your research strategy and select the methods that are likely to provide the highest quality business intelligence for your organization.

1. Interviews

One-on-one interviews are one of the most commonly used data collection methods in qualitative research because they allow you to collect highly personalized information directly from the source. Interviews explore participants' opinions, motivations, beliefs, and experiences and are particularly beneficial in gathering data on sensitive topics because respondents are more likely to open up in a one-on-one setting than in a group environment.

Interviews can be conducted in person or by online video call. Typically, they are separated into three main categories:

- Structured Interviews - Structured interviews consist of predetermined (and usually closed) questions with little or no variation between interviewees. There is generally no scope for elaboration or follow-up questions, making them better suited to researching specific topics.

- Unstructured Interviews – Conversely, unstructured interviews have little to no organization or preconceived topics and include predominantly open questions. As a result, the discussion will flow in completely different directions for each participant and can be very time-consuming. For this reason, unstructured interviews are generally only used when little is known about the subject area or when in-depth responses are required on a particular subject.

- Semi-Structured Interviews – A combination of the two interviews mentioned above, semi-structured interviews comprise several scripted questions but allow both interviewers and interviewees the opportunity to diverge and elaborate so more in-depth reasoning can be explored.

While each approach has its merits, semi-structured interviews are typically favored as a way to uncover detailed information in a timely manner while highlighting areas that may not have been considered relevant in previous research efforts. Whichever type of interview you utilize, participants must be fully briefed on the format, purpose, and what you hope to achieve. With that in mind, here are a few tips to follow:

- Give them an idea of how long the interview will last

- If you plan to record the conversation, ask permission beforehand

- Provide the opportunity to ask questions before you begin and again at the end.

2. Focus Groups

Focus groups share much in common with less structured interviews, the key difference being that the goal is to collect data from several participants simultaneously. Focus groups are effective in gathering information based on collective views and are one of the most popular data collection instruments in qualitative research when a series of one-on-one interviews proves too time-consuming or difficult to schedule.

Focus groups are most helpful in gathering data from a specific group of people, such as donors or clients from a particular demographic. The discussion should be focused on a specific topic and carefully guided and moderated by the researcher to determine participant views and the reasoning behind them.

Feedback in a group setting often provides richer data than one-on-one interviews, as participants are generally more open to sharing when others are sharing too. Plus, input from one participant may spark insight from another that would not have come to light otherwise. However, here are a couple of potential downsides:

- If participants are uneasy with each other, they may not be at ease openly discussing their feelings or opinions.

- If the topic is not of interest or does not focus on something participants are willing to discuss, data will lack value.

The size of the group should be carefully considered. Research suggests over-recruiting to avoid risking cancellation, even if that means moderators have to manage more participants than anticipated. The optimum group size is generally between six and eight for all participants to be granted ample opportunity to speak. However, focus groups can still be successful with as few as three or as many as fourteen participants.

3. Observation

Observation is one of the ultimate data collection tools in qualitative research for gathering information through subjective methods. A technique used frequently by modern-day marketers, qualitative observation is also favored by psychologists, sociologists, behavior specialists, and product developers.

The primary purpose is to gather information that cannot be measured or easily quantified. It involves virtually no cognitive input from the participants themselves. Researchers simply observe subjects and their reactions during the course of their regular routines and take detailed field notes from which to draw information.

Observational techniques vary in terms of contact with participants. Some qualitative observations involve the complete immersion of the researcher over a period of time. For example, attending the same church, clinic, society meetings, or volunteer organizations as the participants. Under these circumstances, researchers will likely witness the most natural responses rather than relying on behaviors elicited in a simulated environment. Depending on the study and intended purpose, they may or may not choose to identify themselves as a researcher during the process.

Regardless of whether you take a covert or overt approach, remember that because each researcher is as unique as every participant, they will have their own inherent biases. Therefore, observational studies are prone to a high degree of subjectivity. For example, one researcher’s notes on the behavior of donors at a society event may vary wildly from the next. So, each qualitative observational study is unique in its own right.

4. Open-Ended Surveys and Questionnaires

Open-ended surveys and questionnaires allow organizations to collect views and opinions from respondents without meeting in person. They can be sent electronically and are considered one of the most cost-effective qualitative data collection tools. Unlike closed question surveys and questionnaires that limit responses, open-ended questions allow participants to provide lengthy and in-depth answers from which you can extrapolate large amounts of data.

The findings of open-ended surveys and questionnaires can be challenging to analyze because there are no uniform answers. A popular approach is to record sentiments as positive, negative, and neutral and further dissect the data from there. To gather the best business intelligence, carefully consider the presentation and length of your survey or questionnaire. Here is a list of essential considerations:

- Number of questions : Too many can feel intimidating, and you’ll experience low response rates. Too few can feel like it’s not worth the effort. Plus, the data you collect will have limited actionability. The consensus on how many questions to include varies depending on which sources you consult. However, 5-10 is a good benchmark for shorter surveys that take around 10 minutes and 15-20 for longer surveys that take approximately 20 minutes to complete.

- Personalization: Your response rate will be higher if you greet patients by name and demonstrate a historical knowledge of their interactions with your brand.

- Visual elements : Recipients can be easily turned off by poorly designed questionnaires. Besides, it’s a good idea to customize your survey template to include brand assets like colors, logos, and fonts to increase brand loyalty and recognition.

- Reminders : Sending survey reminders is the best way to improve your response rate. You don’t want to hassle respondents too soon, nor do you want to wait too long. Sending a follow-up at around the 3-7 mark is usually the most effective.

- Building a feedback loop : Adding a tick-box requesting permission for further follow-ups is a proven way to elicit more in-depth feedback. Plus, it gives respondents a voice and makes their opinion feel valued.

5. Case Studies

Case studies are often a preferred method of qualitative research data collection for organizations looking to generate incredibly detailed and in-depth information on a specific topic. Case studies are usually a deep dive into one specific case or a small number of related cases. As a result, they work well for organizations that operate in niche markets.

Case studies typically involve several qualitative data collection methods, including interviews, focus groups, surveys, and observation. The idea is to cast a wide net to obtain a rich picture comprising multiple views and responses. When conducted correctly, case studies can generate vast bodies of data that can be used to improve processes at every client and donor touchpoint.

The best way to demonstrate the purpose and value of a case study is with an example: A Longitudinal Qualitative Case Study of Change in Nonprofits – Suggesting A New Approach to the Management of Change .

The researchers established that while change management had already been widely researched in commercial and for-profit settings, little reference had been made to the unique challenges in the nonprofit sector. The case study examined change and change management at a single nonprofit hospital from the viewpoint of all those who witnessed and experienced it. To gain a holistic view of the entire process, research included interviews with employees at every level, from nursing staff to CEOs, to identify the direct and indirect impacts of change. Results were collated based on detailed responses to questions about preparing for change, experiencing change, and reflecting on change.

6. Text Analysis

Text analysis has long been used in political and social science spheres to gain a deeper understanding of behaviors and motivations by gathering insights from human-written texts. By analyzing the flow of text and word choices, relationships between other texts written by the same participant can be identified so that researchers can draw conclusions about the mindset of their target audience. Though technically a qualitative data collection method, the process can involve some quantitative elements, as often, computer systems are used to scan, extract, and categorize information to identify patterns, sentiments, and other actionable information.

You might be wondering how to collect written information from your research subjects. There are many different options, and approaches can be overt or covert.

Examples include:

- Investigating how often certain cause-related words and phrases are used in client and donor social media posts.

- Asking participants to keep a journal or diary.

- Analyzing existing interview transcripts and survey responses.

By conducting a detailed analysis, you can connect elements of written text to specific issues, causes, and cultural perspectives, allowing you to draw empirical conclusions about personal views, behaviors, and social relations. With small studies focusing on participants' subjective experience on a specific theme or topic, diaries and journals can be particularly effective in building an understanding of underlying thought processes and beliefs.

7. Audio and Video Recordings

Similarly to how data is collected from a person’s writing, you can draw valuable conclusions by observing someone’s speech patterns, intonation, and body language when you watch or listen to them interact in a particular environment or within specific surroundings.

Video and audio recordings are helpful in circumstances where researchers predict better results by having participants be in the moment rather than having them think about what to write down or how to formulate an answer to an email survey.

You can collect audio and video materials for analysis from multiple sources, including:

- Previously filmed records of events

- Interview recordings

- Video diaries

Utilizing audio and video footage allows researchers to revisit key themes, and it's possible to use the same analytical sources in multiple studies – providing that the scope of the original recording is comprehensive enough to cover the intended theme in adequate depth.

It can be challenging to present the results of audio and video analysis in a quantifiable form that helps you gauge campaign and market performance. However, results can be used to effectively design concept maps that extrapolate central themes that arise consistently. Concept Mapping offers organizations a visual representation of thought patterns and how ideas link together between different demographics. This data can prove invaluable in identifying areas for improvement and change across entire projects and organizational processes.

8. Hybrid Methodologies

It is often possible to utilize data collection methods in qualitative research that provide quantitative facts and figures. So if you’re struggling to settle on an approach, a hybrid methodology may be a good starting point. For instance, a survey format that asks closed and open questions can collect and collate quantitative and qualitative data.

A Net Promoter Score (NPS) survey is a great example. The primary goal of an NPS survey is to collect quantitative ratings of various factors on a score of 1-10. However, they also utilize open-ended follow-up questions to collect qualitative data that helps identify insights into the trends, thought processes, reasoning, and behaviors behind the initial scoring.

Collect and Collate Actionable Data with UpMetrics

Most nonprofits believe data is strategically important. It has been statistically proven that organizations with advanced data insights achieve their missions more efficiently. Yet, studies show that despite 90% of organizations collecting data, only 5% believe internal decision-making is data-driven. At UpMetrics, we’re here to help you change that.

UpMetrics specializes in bringing technology and humanity together to serve social good. Our unique social impact software combines quantitative and qualitative data collection methods and analysis techniques, enabling social impact organizations to gain insights, drive action, and inspire change. By reporting and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data in one intuitive platform, your impact organization gains the understanding it needs to identify the drivers of positive outcomes, achieve transparency, and increase knowledge sharing across stakeholders.

Contact us today to learn more about our nonprofit impact measurement solutions and discover the power of a partnership with UpMetrics.

Disrupting Tradition

Download our case study to discover how the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation is using a Learning Mindset to Support Grantees in Measuring Impact

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Collecting and Analyzing Qualitative Data

Brent Wolff, Frank Mahoney, Anna Leena Lohiniva, and Melissa Corkum

- Choosing When to Apply Qualitative Methods

- Commonly Used Qualitative Methods in Field Investigations

- Sampling and Recruitment for Qualitative Research

- Managing, Condensing, Displaying, and Interpreting Qualitative Data

- Coding and Analysis Requirements

Qualitative research methods are a key component of field epidemiologic investigations because they can provide insight into the perceptions, values, opinions, and community norms where investigations are being conducted ( 1,2 ). Open-ended inquiry methods, the mainstay of qualitative interview techniques, are essential in formative research for exploring contextual factors and rationales for risk behaviors that do not fit neatly into predefined categories. For example, during the 2014–2015 Ebola virus disease outbreaks in parts of West Africa, understanding the cultural implications of burial practices within different communities was crucial to designing and monitoring interventions for safe burials ( Box 10.1 ). In program evaluations, qualitative methods can assist the investigator in diagnosing what went right or wrong as part of a process evaluation or in troubleshooting why a program might not be working as well as expected. When designing an intervention, qualitative methods can be useful in exploring dimensions of acceptability to increase the chances of intervention acceptance and success. When performed in conjunction with quantitative studies, qualitative methods can help the investigator confirm, challenge, or deepen the validity of conclusions than either component might have yielded alone ( 1,2 ).

Qualitative research was used extensively in response to the Ebola virus disease outbreaks in parts of West Africa to understand burial practices and to design culturally appropriate strategies to ensure safe burials. Qualitative studies were also used to monitor key aspects of the response.

In October 2014, Liberia experienced an abrupt and steady decrease in case counts and deaths in contrast with predicted disease models of an increased case count. At the time, communities were resistant to entering Ebola treatment centers, raising the possibility that patients were not being referred for care and communities might be conducting occult burials.

To assess what was happening at the community level, the Liberian Emergency Operations Center recruited epidemiologists from the US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the African Union to investigate the problem.

Teams conducted in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with community leaders, local funeral directors, and coffin makers and learned that communities were not conducting occult burials and that the overall number of burials was less than what they had experienced in previous years. Other key findings included the willingness of funeral directors to cooperate with disease response efforts, the need for training of funeral home workers, and considerable community resistance to cremation practices. These findings prompted the Emergency Operations Center to open a burial ground for Ebola decedents, support enhanced testing of burials in the private sector, and train private-sector funeral workers regarding safe burial practices.

Source: Melissa Corkum, personal communication.

Similar to quantitative approaches, qualitative research seeks answers to specific questions by using rigorous approaches to collecting and compiling information and producing findings that can be applicable beyond the study population. The fundamental difference in approaches lies in how they translate real-life complexities of initial observations into units of analysis. Data collected in qualitative studies typically are in the form of text or visual images, which provide rich sources of insight but also tend to be bulky and time-consuming to code and analyze. Practically speaking, qualitative study designs tend to favor small, purposively selected samples ideal for case studies or in-depth analysis ( 1 ). The combination of purposive sampling and open-ended question formats deprive qualitative study designs of the power to quantify and generalize conclusions, one of the key limitations of this approach.

Qualitative scientists might argue, however, that the generalizability and precision possible through probabilistic sampling and categorical outcomes are achieved at the cost of enhanced validity, nuance, and naturalism that less structured approaches offer ( 3 ). Open-ended techniques are particularly useful for understanding subjective meanings and motivations underlying behavior. They enable investigators to be equally adept at exploring factors observed and unobserved, intentions as well as actions, internal meanings as well as external consequences, options considered but not taken, and unmeasurable as well as measurable outcomes. These methods are important when the source of or solution to a public health problem is rooted in local perceptions rather than objectively measurable characteristics selected by outside observers ( 3 ). Ultimately, such approaches have the ability to go beyond quantifying questions of how much or how many to take on questions of how or why from the perspective and in the words of the study subjects themselves ( 1,2 ).

Another key advantage of qualitative methods for field investigations is their flexibility ( 4 ). Qualitative designs not only enable but also encourage flexibility in the content and flow of questions to challenge and probe for deeper meanings or follow new leads if they lead to deeper understanding of an issue (5). It is not uncommon for topic guides to be adjusted in the course of fieldwork to investigate emerging themes relevant to answering the original study question. As discussed herein, qualitative study designs allow flexibility in sample size to accommodate the need for more or fewer interviews among particular groups to determine the root cause of an issue (see the section on Sampling and Recruitment in Qualitative Research). In the context of field investigations, such methods can be extremely useful for investigating complex or fast-moving situations where the dimensions of analysis cannot be fully anticipated.

Ultimately, the decision whether to include qualitative research in a particular field investigation depends mainly on the nature of the research question itself. Certain types of research topics lend themselves more naturally to qualitative rather than other approaches ( Table 10.1 ). These include exploratory investigations when not enough is known about a problem to formulate a hypothesis or develop a fixed set of questions and answer codes. They include research questions where intentions matter as much as actions and “why?” or “why not?” questions matter as much as precise estimation of measured outcomes. Qualitative approaches also work well when contextual influences, subjective meanings, stigma, or strong social desirability biases lower faith in the validity of responses coming from a relatively impersonal survey questionnaire interview.

The availability of personnel with training and experience in qualitative interviewing or observation is critical for obtaining the best quality data but is not absolutely required for rapid assessment in field settings. Qualitative interviewing requires a broader set of skills than survey interviewing. It is not enough to follow a topic guide like a questionnaire, in order, from top to bottom. A qualitative interviewer must exercise judgment to decide when to probe and when to move on, when to encourage, challenge, or follow relevant leads even if they are not written in the topic guide. Ability to engage with informants, connect ideas during the interview, and think on one’s feet are common characteristics of good qualitative interviewers. By far the most important qualification in conducting qualitative fieldwork is a firm grasp of the research objectives; with this qualification, a member of the research team armed with curiosity and a topic guide can learn on the job with successful results.

Semi-Structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews can be conducted with single participants (in-depth or individual key informants) or with groups (focus group discussions [FGDs] or key informant groups). These interviews follow a suggested topic guide rather than a fixed questionnaire format. Topic guides typically consist of a limited number ( 10– 15 ) of broad, open-ended questions followed by bulleted points to facilitate optional probing. The conversational back-and-forth nature of a semi-structured format puts the researcher and researched (the interview participants) on more equal footing than allowed by more structured formats. Respondents, the term used in the case of quantitative questionnaire interviews, become informants in the case of individual semi-structured in-depth interviews (IDIs) or participants in the case of FGDs. Freedom to probe beyond initial responses enables interviewers to actively engage with the interviewee to seek clarity, openness, and depth by challenging informants to reach below layers of self-presentation and social desirability. In this respect, interviewing is sometimes compared with peeling an onion, with the first version of events accessible to the public, including survey interviewers, and deeper inner layers accessible to those who invest the time and effort to build rapport and gain trust. (The theory of the active interview suggests that all interviews involve staged social encounters where the interviewee is constantly assessing interviewer intentions and adjusting his or her responses accordingly [ 1 ]. Consequently good rapport is important for any type of interview. Survey formats give interviewers less freedom to divert from the preset script of questions and formal probes.)

Individual In-Depth Interviews and Key-Informant Interviews

The most common forms of individual semi-structured interviews are IDIs and key informant interviews (KIIs). IDIs are conducted among informants typically selected for first-hand experience (e.g., service users, participants, survivors) relevant to the research topic. These are typically conducted as one-on-one face-to-face interviews (two-on-one if translators are needed) to maximize rapport-building and confidentiality. KIIs are similar to IDIs but focus on individual persons with special knowledge or influence (e.g., community leaders or health authorities) that give them broader perspective or deeper insight into the topic area ( Box 10.2 ). Whereas IDIs tend to focus on personal experiences, context, meaning, and implications for informants, KIIs tend to steer away from personal questions in favor of expert insights or community perspectives. IDIs enable flexible sampling strategies and represent the interviewing reference standard for confidentiality, rapport, richness, and contextual detail. However, IDIs are time-and labor-intensive to collect and analyze. Because confidentiality is not a concern in KIIs, these interviews might be conducted as individual or group interviews, as required for the topic area.

Focus Group Discussions and Group Key Informant Interviews

FGDs are semi-structured group interviews in which six to eight participants, homogeneous with respect to a shared experience, behavior, or demographic characteristic, are guided through a topic guide by a trained moderator ( 6 ). (Advice on ideal group interview size varies. The principle is to convene a group large enough to foster an open, lively discussion of the topic, and small enough to ensure all participants stay fully engaged in the process.) Over the course of discussion, the moderator is expected to pose questions, foster group participation, and probe for clarity and depth. Long a staple of market research, focus groups have become a widely used social science technique with broad applications in public health, and they are especially popular as a rapid method for assessing community norms and shared perceptions.

Focus groups have certain useful advantages during field investigations. They are highly adaptable, inexpensive to arrange and conduct, and often enjoyable for participants. Group dynamics effectively tap into collective knowledge and experience to serve as a proxy informant for the community as a whole. They are also capable of recreating a microcosm of social norms where social, moral, and emotional dimensions of topics are allowed to emerge. Skilled moderators can also exploit the tendency of small groups to seek consensus to bring out disagreements that the participants will work to resolve in a way that can lead to deeper understanding. There are also limitations on focus group methods. Lack of confidentiality during group interviews means they should not be used to explore personal experiences of a sensitive nature on ethical grounds. Participants may take it on themselves to volunteer such information, but moderators are generally encouraged to steer the conversation back to general observations to avoid putting pressure on other participants to disclose in a similar way. Similarly, FGDs are subject by design to strong social desirability biases. Qualitative study designs using focus groups sometimes add individual interviews precisely to enable participants to describe personal experiences or personal views that would be difficult or inappropriate to share in a group setting. Focus groups run the risk of producing broad but shallow analyses of issues if groups reach comfortable but superficial consensus around complex topics. This weakness can be countered by training moderators to probe effectively and challenge any consensus that sounds too simplistic or contradictory with prior knowledge. However, FGDs are surprisingly robust against the influence of strongly opinionated participants, highly adaptable, and well suited to application in study designs where systematic comparisons across different groups are called for.

Like FGDs, group KIIs rely on positive chemistry and the stimulating effects of group discussion but aim to gather expert knowledge or oversight on a particular topic rather than lived experience of embedded social actors. Group KIIs have no minimum size requirements and can involve as few as two or three participants.

Egypt’s National Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) program undertook qualitative research to gain an understanding of the contextual behaviors and motivations of healthcare workers in complying with IPC guidelines. The study was undertaken to guide the development of effective behavior change interventions in healthcare settings to improve IPC compliance.

Key informant interviews and focus group discussions were conducted in two governorates among cleaning staff, nursing staff, and physicians in different types of healthcare facilities. The findings highlighted social and cultural barriers to IPC compliance, enabling the IPC program to design responses. For example,

- Informants expressed difficulty in complying with IPC measures that forced them to act outside their normal roles in an ingrained hospital culture. Response: Role models and champions were introduced to help catalyze change.

- Informants described fatalistic attitudes that undermined energy and interest in modifying behavior. Response: Accordingly, interventions affirming institutional commitment to change while challenging fatalistic assumptions were developed.

- Informants did not perceive IPC as effective. Response: Trainings were amended to include scientific evidence justifying IPC practices.

- Informants perceived hygiene as something they took pride in and were judged on. Response: Public recognition of optimal IPC practice was introduced to tap into positive social desirability and professional pride in maintaining hygiene in the work environment.

Qualitative research identified sources of resistance to quality clinical practice in Egypt’s healthcare settings and culturally appropriate responses to overcome that resistance.

____________________ Source: Anna Leena Lohiniva, personal communication.

Visualization Methods

Visualization methods have been developed as a way to enhance participation and empower interviewees relative to researchers during group data collection ( 7 ). Visualization methods involve asking participants to engage in collective problem- solving of challenges expressed through group production of maps, diagrams, or other images. For example, participants from the community might be asked to sketch a map of their community and to highlight features of relevance to the research topic (e.g., access to health facilities or sites of risk concentrations). Body diagramming is another visualization tool in which community members are asked to depict how and where a health threat affects the human body as a way of understanding folk conceptions of health, disease, treatment, and prevention. Ensuing debate and dialogue regarding construction of images can be recorded and analyzed in conjunction with the visual image itself. Visualization exercises were initially designed to accommodate groups the size of entire communities, but they can work equally well with smaller groups corresponding to the size of FGDs or group KIIs.

Selecting a Sample of Study Participants

Fundamental differences between qualitative and quantitative approaches to research emerge most clearly in the practice of sampling and recruitment of study participants. Qualitative samples are typically small and purposive. In-depth interview informants are usually selected on the basis of unique characteristics or personal experiences that make them exemplary for the study, if not typical in other respects. Key informants are selected for their unique knowledge or influence in the study domain. Focus group mobilization often seeks participants who are typical with respect to others in the community having similar exposure or shared characteristics. Often, however, participants in qualitative studies are selected because they are exceptional rather than simply representative. Their value lies not in their generalizability but in their ability to generate insight into the key questions driving the study.

Determining Sample Size

Sample size determination for qualitative studies also follows a different logic than that used for probability sample surveys. For example, whereas some qualitative methods specify ideal ranges of participants that constitute a valid observation (e.g., focus groups), there are no rules on how many observations it takes to attain valid results. In theory, sample size in qualitative designs should be determined by the saturation principle , where interviews are conducted until additional interviews yield no additional insights into the topic of research ( 8 ). Practically speaking, designing a study with a range in number of interviews is advisable for providing a level of flexibility if additional interviews are needed to reach clear conclusions.

Recruiting Study Participants

Recruitment strategies for qualitative studies typically involve some degree of participant self-selection (e.g., advertising in public spaces for interested participants) and purposive selection (e.g., identification of key informants). Purposive selection in community settings often requires authorization from local authorities and assistance from local mobilizers before the informed consent process can begin. Clearly specifying eligibility criteria is crucial for minimizing the tendency of study mobilizers to apply their own filters regarding who reflects the community in the best light. In addition to formal eligibility criteria, character traits (e.g., articulate and interested in participating) and convenience (e.g., not too far away) are legitimate considerations for whom to include in the sample. Accommodations to personality and convenience help to ensure the small number of interviews in a typical qualitative design yields maximum value for minimum investment. This is one reason why random sampling of qualitative informants is not only unnecessary but also potentially counterproductive.

Analysis of qualitative data can be divided into four stages: data management, data condensation, data display, and drawing and verifying conclusions ( 9 ).

Managing Qualitative Data

From the outset, developing a clear organization system for qualitative data is important. Ideally, naming conventions for original data files and subsequent analysis should be recorded in a data dictionary file that includes dates, locations, defining individual or group characteristics, interviewer characteristics, and other defining features. Digital recordings of interviews or visualization products should be reviewed to ensure fidelity of analyzed data to original observations. If ethics agreements require that no names or identifying characteristics be recorded, all individual names must be removed from final transcriptions before analysis begins. If data are analyzed by using textual data analysis software, maintaining careful version control over the data files is crucial, especially when multiple coders are involved.

Condensing Qualitative Data