Peace Education in the Philippines: My Journey as a Peace Educator and Some Lessons Learned

(Reposted from: The Journal of Social Encounters. 2020 )

By Loreta Navarro-Castro

In this essay, Loreta Navarro-Castro discusses the development of Peace Education in the Philippines. She also discusses her journey as a peace educator and organizer of peace education. She concludes with lessons that she learned in her work that may be useful for others interested in Peace Education and Advocacy.

Loreta Navarro-Castro is the founding director of the Center for Peace Education of Miriam College, Philippines. She also teaches in the International Studies and Education departments of the College. She is currently involved in the work of the Global Campaign for Peace Education; the GPPAC Peace Education Working Group; the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons; and the Catholic Nonviolence Initiative of Pax Christi International.

Navarro-Castro, Loreta (2020) “Peace Education in the Philippines: My Journey as a Peace Educator and Some Lessons Learned,” The Journal of Social Encounters: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, 90-95.

Join the Campaign & help us #SpreadPeaceEd!

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

Related Posts

Including transformative education in pre-service teacher training: A guide for universities and teacher training institutions in the Arab region

Building a culture of peace (Trinidad & Tobago)

Faculty equipped with knowledge and skills to teach peace effectively (Pakistan)

UNESCO trains teachers in Education for Peace and Sustainable Development (EPSD) in Myanmar

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Yes, add me to your mailing list!

What the Philippines tells us about democracy

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Julia Andrea R. Abad

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} ASEAN is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

It’s more fun in the Philippines – observers of Philippine democracy could very well apply our tourism slogan to our political landscape. Hard-won after centuries of colonization, years of occupation and decades of dictatorship, Philippine-style democracy is colourful, occasionally chaotic – and arguably inspiring.

Take elections, for example, the cornerstone of democratic institutions. Voters see their power to choose their leaders as their strongest check on the behaviour of the government, their one chance to exact accountability.

Analysts and commentators have branded political campaigns in the Philippines as “highly entertaining”. The mix of old political clans, showbiz personalities and the ubiquitous song and dance that pepper the campaign trail provide plenty of amusement. But be not deceived; the power to choose is a right and responsibility that Filipinos hold dear.

Indeed, ballots are almost sacred in the Philippines. Voters have risked their personal safety to exercise the right. In many cases, the public has seen it as their one weapon against those who abuse their position.

Beyond balloting, democracy is a “government by discussion” (to quote the Indian economist Amartya Sen), characterized by public dialogue and interaction. The vibrancy of democracy in the Philippines hinges largely on the quality of this dialogue and interaction. A government that engages its citizens, is inclusive in its decision-making and, most importantly, enjoys the trust of its electorate, can almost certainly count on public support when making tough decisions. The reverse has also been seen, as in the case of a leadership facing a “crisis of legitimacy” that was seen to make decisions out of political expediency rather than the public good; in this case the people’s mandate, won squarely in an electoral contest, has proven itself to be a potent force for positive change.

The authors of a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research argue that democracy is good for economic growth for various reasons, including the ability of democracies to implement economic reforms. They present evidence from a panel of countries between 1960 and 2010 showing that the “robust and sizeable effect of democracy on economic growth … suggests that a country that switches from non-democracy to democracy achieves about 20% higher GDP per capita in the long run (or roughly in the next 30 years)”.

We can see this in the case of the Philippines, which has enjoyed 60 straight quarters of economic growth since the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Average GDP growth from 2010 to 2013 was recorded at 6.3%, significantly higher than the 4.5% average GDP growth registered from 2001 to 2009. That this relatively higher rate of growth has happened alongside a series of economic reforms backed up by a strong electoral mandate should not be taken as pure coincidence. Closing loopholes in tax collection, an overhaul in customs administration, and passing key legislation on excise taxes – these would not have taken place in an environment which was not supportive of – or indeed, craving for – reform.

Outside of economic reforms, this strong mandate has also enabled the passage of social sector reforms – among them legislation allowing women access to vital information and facilities pertaining to their reproductive health, and a measure extending the education cycle to meet the global standard. These measures had passionate advocates on both sides, and a less committed leadership could have wavered at any point.

Improved government via more efficient tax collection and customs administration, access to vital information and services and a better standard of education: how could one argue that this is not what voters want when they take to the polls?

Of course, this is not always what voters get, even when they faithfully exercise their right to choose. Roadblocks in the process remain, resulting in an occasional disconnect between what voters want, and what they are eventually given. Recent reforms – such as those automating the process and synchronizing elections in different parts of the country – have sought to lessen fraud, intimidation of voters and the exercise of patronage. These instances, however, are far from being wiped out completely. While incidents of poll violence were significantly lower in the most recent mid-term elections, putting an end to vote-buying and the general exercise of political patronage continues to be a challenge.

More significantly, while the Philippines has embraced the democratic traditions of participation and the freedom of choice and expression, the longer-term challenge remains to deepen the quality of its democracy. Building political parties on ideology and merit rather than personality, strengthening accountability mechanisms within government, creating alternative sources of reliable information, and enabling the electorate to make informed choices – there is clearly much more work that needs to be done, despite the progress that has been made.

The next step, however, has to be taken by the electorate itself. We have seen how a strong mandate for change has made change happen – now we just need to sustain it by demanding continuity.

Democracy may be more fun in the Philippines, but this is not a country that takes or makes its choices lightly. Stay tuned.

Author: Julia Andrea R. Abad is the Head of the Presidential Management Staff at the Office of the President of the Republic of the Philippines

Image: A man poses with his inked thumb after voting at the Philippines presidential election in Pasay City, Manila May 10, 2010. REUTERS/Nicky Loh

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Geographies in Depth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

The Horn of Africa's deep groundwater could be a game-changer for drought resilience

Bradley Hiller, Jude Cobbing and Andrew Harper

May 16, 2024

Scale matters more than ever for European competitiveness. Here's why

Sven Smit and Jan Mischke

May 15, 2024

Funding the green technology innovation pipeline: Lessons from China

May 8, 2024

These are the top ranking universities in Asia for 2024

Global South leaders: 'It’s time for the Global North to walk the talk and collaborate'

Pooja Chhabria

April 29, 2024

How can Japan navigate digital transformation ahead of a ‘2025 digital cliff’?

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

April 25, 2024

Eurasia Review

A Journal of Analysis and News

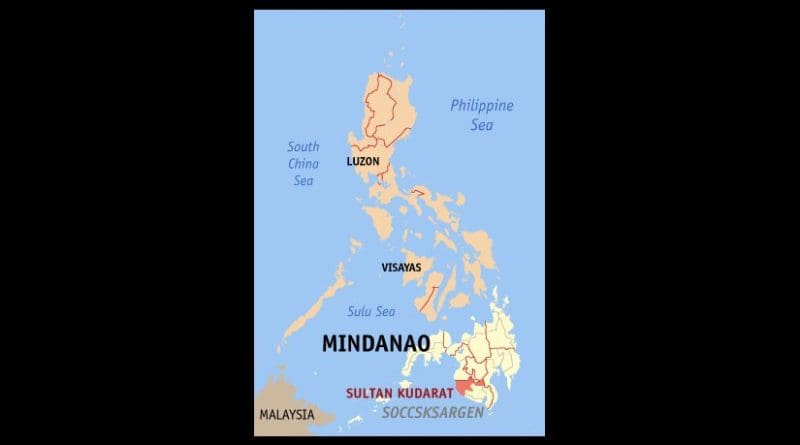

Map of the Philippines with Sultan Kudarat, Mindanao, highlighted. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

Peace Process In Mindanao, The Philippines: Evolution And Lessons Learned – Analysis

The Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (2014) marks the first significant peace agreement worldwide in ten years and has become an inevitable reference for any other contemporary peace process.

By Kristian Herbolzheimer*

On March 27th 2014 the government of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) signed an agreement to end an armed conflict that had started in 1969, caused more than 120,000 deaths and forcibly displaced hundreds of thousands of people. The Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro is the main peace agreement to be signed worldwide since the agreement that stopped the armed conflict in Nepal in 2006.

Every peace agreement addresses a particular context and conflict. However, the Mindanao process is now a crucial reference for other peace processes, given that it is the most recent.

Of the 59 armed conflicts that have ended in the last 30 years, 44 concluded with peace agreements (Fisas, 2015: 16). The social, academic, and institutional capacities to analyse these processes and strengthen peacebuilding policies have thrived in parallel (Human Security Report Project, 2012). However, no peace process has been implemented without some difficulties. For this reason all peace processes learn from previous experiences, while innovating in their own practices and contributing overall to international experience of peacebuilding. The Mindanao peace process learned lessons from the experiences of South Sudan, Aceh (Indonesia) and Northern Ireland, among others. Currently, other countries affected by internal conflicts such as Myanmar, Thailand and Turkey are analysing the Mindanao peace agreement with considerable interest.

This report analyses the keys that allowed the parties to reach an agreement and the challenges facing the Philippines in terms of implementation. The report targets an international audience and aims to provide reflections that might be useful for other peace processes. After introducing the context and development of the Mindanao peace process, the report analyses the actions and initiatives that allowed negotiations to make progress for 17 years and the innovations brought about by this process in areas such as public participation. Particular attention is devoted to the security-related agreements (including arms decommissioning by the insurgency) and to the mechanisms accompanying and verifying the agreement’s implementation.

The Philippines is an archipelago comprising around 7,000 islands. Remarkable among them are the largest one, Luzon (where the capital, Manila, is situated) and the second largest, Mindanao. Together with Timor-Leste, this is the only Asian country with a majority Christian popula- tion. Around 100 million people live in a territory covering 300,000 km2. The system of government is presidential and executive power is limited to a single term of six years.

The country owes its name to King Philip II of Spain, in whose service Magellan was sailing around the world when he arrived at the archipelago in 1521. After being a Spanish colony for three centuries, in 1898 the Philippines came under U.S. administration. A detail with far-reaching consequences is that Spain never took real control of the island of Mindanao. Islam had arrived three centuries before Magellan, and the Spanish found a well- consolidated system of governance, mainly through the sultanates of Maguindanao and Sulu.

In 1946 the Philippines was the first Asian country to gain independence without an armed struggle (one year before India). It was also a pioneer in putting an end to a despotic regime by peaceful means when a non-violent people’s revolution overthrew the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in 1986. In 2001 a second people’s power revolution brought the government of Joseph Estrada – who was accused of corruption – to an end. Even so, the developments that have occurred over nearly 30 years of democracy have been slow. Politics continues to be the feud of a few families who perpetuate themselves in power from generation to generation. Relatives of deposed presidents remain active in politics and enjoy significant support.

Some indicators show advances in poverty reduction, literacy and employment, but neighbouring countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand are far ahead in this regard (UNDP, 2015). The persistence of social inequalities feeds the discourse of the New People’s Army, a Maoist- inspired insurgency that has been active since 1968.

Apart from the armed conflict in Mindanao and the communist insurgency, in recent years the Philippines has also suffered the onslaught of cells of Islamist terrorists linked to transnational networks.

Roots and humanitarian consequences of the conflict

The Muslim population of Mindanao has experienced harassment and discrimination since the times of the Spanish colony (1565-1898). The U.S. colonial administration (1898-1945) initiated a process of land entitlement that privileged Christian settlers coming from other islands of the archipelago. This policy of land dispossession continued after independence, coupled with government policies aimed at the assimilation of the Muslim minority. Currently, the Muslim population is in the majority only in the western part of Mindanao and in the adjacent islands that proliferate up to the borders of Malaysia and Indonesia. Ten per cent of the population in this area are non-Islamised indigenous peoples.

In 1968 an alleged massacre of Muslim army recruits in Manila led to the creation of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), which started an armed struggle for independence. In 1996 the government and the MNLF signed a peace agreement that granted autonomy to provinces with a Muslim majority. The group demobilised as a result, but a breakaway subgroup, the Islamic Front, rejected the terms of the agreement. However, this insurgency’s preference for a negotiated solution led to the signing of a bilateral ceasefire in 1997 and the start of formal peace negotiations in 1999.

The armed conflict in Mindanao has caused around 120,000 deaths, especially in the 1970s. In the 21st century it has been a low-intensity conflict, but continuous instability has generated a phenomenon of multiple displacements: thousands of people flee when there are skirmishes – which sometimes involve other armed actors – and return to their homes once the situation is stabilised. In 2008 the last political crisis in the peace process triggered the displacement of around 500,000 people in a few weeks in what became the most severe humanitarian crisis in the world at the time.

Structure and development of the negotiations

The negotiations lasted for 17 years (1997-2014) and were initially conducted in the Philippines and without mediation. Since 1999 the negotiating teams comprised five plenipotentiary members, with the support of a technical team of around ten people (a variable number). The intensity and duration of the negotiations oscillated over the years. In the last period (2009-14) the parties met in 26 negotiation rounds each lasting between three and five days.

The negotiations were halted on three occasions, triggering new armed confrontations in 2000, 2003 and 2008. After each one the parties agreed on new mechanisms designed to strengthen the negotiations infrastructure. In 2001 the Malaysian government accepted the request of the government of the Philippines to host and facilitate the negotiations. In 2004 the parties agreed to create an International Monitoring Team (IMT) to verify the ceasefire, comprising 50 unarmed members of the armed forces of Malaysia, Libya and Brunei cantoned in five cities in the conflict area. In 2009 this team was expanded and strengthened: two officers of the Norwegian army reinforced the security component, while the European Union (EU) provided two experts in human rights, international humanitarian law and humanitarian response. In parallel, the IMT incorporated a Civilian Protection Component comprising one international and three local non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

In 2009 the negotiating parties agreed to create an International Contact Group (ICG) to act as observers at the negotiations and advise the parties and the facilitator.1

The ICG is formed by four countries (Britain, Japan, Turkey and Saudi Arabia), together with four international NGOs (Conciliation Resources, the Community of Sant Egidio, the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and Muhammadiyah).

Peace agreements

The negotiations started in 1997 with an agreement on a general cessation of hostilities. In the Tripoli Agreement (2001) the parties defined a negotiation agenda with three main elements: security (which had already been agreed on in 2001); humanitarian response, rehabilitation and development (agreed in 2002); and ancestral territories (2008).

In October 2012 the parties finally adopted the Framework Agreement establishing a roadmap for the transition. In the following 15 months the parties concluded the annexes on transitional modalities (February 2013), revenue generation and wealth sharing (July 2013), power sharing (December 2013), and normalisation (January 2014). Finally, in March 2014 the Comprehensive Agreement was signed in the Presidential Palace.

The central axis of the agreement is the establishment of a new self-governing entity called Bangsamoro, which will replace the existing Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao after a transition led by the MILF. The agreement envisages a process of reform in the new autonomous region that will replace the presidential system that governs the rest of the country with a parliamentary one. The objective is to promote the emergence of programmatic political parties.

The government understands that the insurgency must be part of the solution and must assume the corresponding responsibilities. To this end it has encouraged the transformation of the insurgency into a political movement able to take part in local and regional elections.

In terms of endorsement, the peace agreement must be transformed into a law that will regulate the Statute of Autonomy, called the Bangsamoro Basic Law. After parliamentary approval, a plebiscite will be held in the conflict-affected areas. This plebiscite will also serve to determine the territorial extent of the autonomous region, since the municipalities bordering the current autonomous community will have the option to join the new entity.

Constitutional reform is a contentious issue. The MILF insists on the need for reform in order to consolidate the agreements. However, the government has been reluctant to initiate a process that could be tedious and could open a “Pandora’s box”. But doubts about some of the agree- ments’ compliance with the constitution suggest that such a reform process might eventually be discussed. Beyond the agreement with the MILF, the peace process in Mindanao could contribute to opening a national debate about the territorial organisation of the country, since important sectors in other regions are demanding broad constitutional reform along federal lines.

Roadmap of the transition

A controversial issue during the negotiations was the expected time line for implementation. The MILF suggested a six-year period, while the government refused to make commitments beyond its presidential term (2010-16), since the Philippine political system lacks guarantees in terms of the continuity of public policies from one administration to the next. Finally, the MILF accepted this argument and the 2012 Framework Agreement defined a roadmap for implementation with a time horizon of the presidential elections of May 2016.

The key implementation institutions are as follows:

- The Transition Commission comprises 15 people (seven appointed by each side, under an MILF chairperson). Its main mission was the drafting of the Bangsamoro Basic Law, which was submitted to Congress for approval in September 2014.

- The Transitional Authority will be headed by the MILF and will comprise representatives of various social, political and economic actors from the autonomous region. It will be formally set up after the Basic Law is enacted by Congress. Its mission will be to pilot the transformation of the existing autonomous institutions until the holding of elections for a new autonomous government (initially expected in May 2016, although they might need to be postponed).

- The Third Party Monitoring Team (TPMT) is in charge of monitoring the implementation of the agreements. It comprises five members (two representatives of national NGOs, two of international NGOs, and a former EU ambassador to the Philippines who acts as coordinator). The TPMT issues periodic reports for both parties, and public reports twice a year. But its most relevant role – and probably the most controversial – will be to certify the end of the implementation process, which, in turn, conditions the MILF decommissioning process.

- Despite the fact that both parties are represented in all the relevant organs, the negotiating teams remain an organ of last resort to resolve potential problems or disagreements. Malaysia – the facilitator country – and the ICG continue to provide support at the request of the parties.

The challenge of normalisation

Apart from enacting the Bangsamoro Basic law and adapting the various regional institutions to the new Statute of Autonomy, the main objective of the transitional period is the consolidation of normalisation, which is understood as “a process whereby communities can achieve their desired quality of life, which includes the pursuit of sustainable livelihood and political participation within a peaceful deliberative society”.2 The concept of normalisation includes what is termed disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration in other contexts, as well as additional elements aimed at the consolidation of peace and human security.

The process of normalisation has four essential elements:

- The first is socioeconomic development programmes for conflict-affected areas. The MILF-led Bangsamoro Development Agency will be in charge of coordination, together with the Sajahatra presidential programme of immediate relief to improve health conditions, education and development.

- Confidence-building measures include two key processes. Firstly, development programmes will be aimed specifically at MILF members and their relatives in their six main camps. Secondly, the government will commit to using amnesties, pardons, and other available mechanisms to resolve the cases of people accused or convicted of actions and crimes related to the Mindanao armed conflict.3 It is worth noting that neither the MILF nor the government security forces face pending accusations of gross human rights violations or crimes against humanity.

- In matters of transitional justice and reconciliation, a three-person team is mandated to elaborate a methodological proposal about how to address the legitimate grievances of the Bangsamoro (Muslim) people, correct historical injustices, and address human rights violations, including marginalisation due to land dispossession. The team can also propose programmes and measures to promote reconciliation between conflict-affected communities and heal the physical, mental and spiritual wounds caused by the conflict. This mandate includes the proposal of measures to guarantee non-repetition.

- The sensitive issue of security has four elements. The first is reform of the police, since responsibility for public order will be given to a new police force for the Bangsamoro that will be civilian in character and accountable to the communities it serves. The negotiating parties commissioned the Independent Commission on Policing to draft a report with recommendations in this regard. This report was delivered in April 2015.

Secondly, the parties agreed to carry out a joint programme to identify and dismantle “private” armed groups (paramilitaries), which are often controlled by mayors and governors. The operational criteria for this task are still awaiting development.

The third element is arms decommissioning by the MILF. This process is defined as the activities aimed at facilitating the transition of the insurgent forces to a productive civilian life. An Independent Decommissioning Body (IDB) is in charge of registering the MILF’s members and weapons, and planning the phases of collecting, transporting and storing weapons.4 There is as yet no agreement among the parties on the final destination of the weapons decommissioned by the insurgency, and they will be temporarily stockpiled in containers and subject to joint supervision by the insurgency and security forces under international coordination.

The fourth and last security-related element affects the armed forces, who have committed to carrying out a repositioning to help facilitate peace and coexistence. This repositioning will be based on a joint evaluation of the security conditions.

Other normalisation-related elements

A Joint Normalisation Committee will coordinate the overall normalisation process. In terms of financing, the government will assume the responsibility to supply the funds necessary to sustain the process, while the MILF has the right to procure and manage additional funds.

A Joint Peace and Security Committee has overall responsibility for the supervision of all security-related matters of normalization until the full deployment of the new Bangsamoro Police. On the operative side, Joint Peace and Security Teams (comprising members of the armed forces, police and the MILF) will handle law and order in the areas agreed by the parties. In parallel, the existing mechanisms for ceasefire verification will remain operative (the Coordination Committee for the Cessation of Hostilities, the Ad Hoc Joint Action Group (AHJAG) to combat crime in MILF areas and the IMT).

The Agreement on Normalisation does not refer to the MILF cantonments because this point was discussed in the framework of the 1997 bilateral ceasefire agreement. After intense debates the parties identified major and satellite camps where the combatants and their relatives had a stable presence and formed rural communities. There was no registry of members of these communities or their weapons, and free individual movement is allowed.

The agreement also established that any movement of troops – by the insurgency or security forces – should be coordinated with the other party.

A special agreement (the AHJAG) allows the police to maintain public order in MILF-controlled areas in prior coordination with the MILF. The state performs its administrative duties under normal conditions in the whole territory.

A difference from the Final Agreement reached with the MNLF in 1996 is that this agreement does not provide for the integration of MILF combatants into the security forces, except for the new autonomous police.

In terms of de-mining, in 2002 the MILF adhered to the Geneva Call against the use of anti-personnel mines. In 2010 the government and MILF agreed to allow the Philippines Campaign against Land Mines to conduct civic education and the identification and destruction of unexploded ordnance.

Enabling factors for the peace process

First and foremost, both parties have long acknowledged the limits of armed confrontation. In 2000 the government broke off the ceasefire to launch “all-out-war”, which led to the MILF’s military defeat in just four months. However, both the government and the security forces realised that the root causes of the problem were not resolved and that the Muslim population retained an unbroken determination to fight for its identity and dignity. From the perspective of the insurgency, since its creation the MILF recognised that armed victory was not possible, and instead focused on the primacy of peace negotiations.

More recently, the reformist government of Benigno Aquino promoted a change in the country’s military doctrine (AFP, 2010) in the framework of its commitment to resolve internal armed conflicts and deal with the growing geopolitical challenges resulting from China’s emergence as a regional power. The new objective is no longer to “win the war”, but to “win the peace”, and the new doctrine emphasises the establishment of relations of trust with the communities affected by the conflict. The overall goal is the liberation of human and financial resources previously devoted to the internal confrontation in order to be able to better deal with external threats.

Interestingly, the parties have also understood the limits of peace negotiations. Both the government and the insurgency admit that the reforms needed to acknowledge and respect the way of life and history of the Muslim and indigenous peoples demand a wide national consensus. The problems that hampered the implementation of past peace agreements highlight the need for a collective ownership of the peace process and its results by society. For this reason both parties have engaged in intensive consultations with the social, academic, political and institutional sectors with the double objective of strengthening the process with the inputs of those who support it, and listening and responding to the concerns of those who are more sceptical and potentially opposed to the negotiations. On several occasions the MILF has gathered hundreds of thousands of followers in huge conventions to ratify the decisions of its Central Committee.

Apart from these consultation processes, the government and the insurgency have included civil society members in their teams and on several occasions have invited civil society delegates and members of Congress to witness the negotiations. The parties also agreed on the participation of civil society in several of the bodies involved in the implementation of the agreements, notably the TPMT.

These institutional efforts towards inclusion are largely a response to the pressures of an organised civil society that has relentlessly promoted peacebuilding initiatives parallel to the negotiations. These initiatives include the creation of peace zones, inter-religious dialogues, capacity-building in the theory and practice of conflict resolution, the consolidation of citizen agendas, lobbying the armed actors, and the creation of ceasefire monitoring mechanisms such as the Bantay Ceasefire or the Civil Protection Component of the IMT.

Some additional elements help explain the progress of the negotiations:

- The parties’ pragmatism and realism: The insurgency abandoned the objective of total independence in the context of negotiations, while the country’s various governments have all recognised the existence of the root causes of the conflict and committed to a solution based on dialogue.

- Confidence-building measures: The lengthy bilateral ceasefire contributed to building trust between the insurgency and military and police commanders, including at the personal level. This trust is currently the main guarantor that there will be no relapse into armed confrontation. Furthermore, both parties recognise international humanitarian law and international human rights treaties (on the recruitment of child soldiers, the prohibition of the use of anti-personnel mines, etc.). These factors have been fundamental in reducing the levels of confrontation and generating trust between the parties and civil society.

- Strengthening of capacities: Both the government and the MILF are well aware of the problems that emerged during the implementation of the 1996 agreement with the MNLF. The parties therefore decided early on to strengthen the capacity of the MILF to manage civil institutions: in 2002 they created the Bangsamoro Development Agency and in 2009 the Bangsamoro Leadership and Management Institute, both led by the MILF.

Additional highlights

The main peacebuilding developments in the Philippines emerged during the presidency of Fidel Ramos (1992-98). Ramos was a retired general who had been chief of staff of the armed forces during the Marcos dictatorship as well as during the first democratic government, i.e. of President Corazón Aquino. In 1992 Ramos promoted an ambitious process of national dialogue (Coronel-Ferrer, 2002) for the drawing up of a national peace policy. The result of this consultation was a conceptual framework that identified the structural problems affecting the country and defined “six paths to peace”. The conceptual framework emphasises negotiations between the government and the insurgency as one of the paths to peace, but states that a peace process must necessarily be wider and more inclusive than mere peace negotiations. This innovative national peace policy has coexisted for years in contrast to (and in conflict with) a classic national security doctrine focused on defeating the internal enemy. In 2003 a crisis in negotiations and the return of violent incidents mobilised civil society to promote an initiative of its own to verify the ceasefire, known as the Bantay Ceasefire. The network was composed of around 200 voluntary members and, despite the financial constraints it faced, became an essential complement to the formal verification commissions, receiving the appreciation of both parties.

An additional element is the outstanding role played by women in the peace process. The Philippines is possibly the country with the best implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) on women, peace and security. Teresita Deles holds the position of presidential adviser for peace, while Miriam Coronel was the first woman to lead a negotiating team that eventually signed a peace agreement. Women have also led the legal advi- sory teams of both the government and the MILF. Similar to other contexts, women in the Philippines have a wide presence and leadership role in civil society, with Muslim and indigenous women playing a fundamental role (Herbolzheimer, 2013; Conciliation Resources, 2015).

Implementation challenges

In spite of the positive developments, the implementation of the peace agreement is facing multiple obstacles.

The first limiting factor is time. During the negotiation of the Framework Agreement (2012) the government man- aged to link the transitional period to the end of the presidential term in May 2016. But the negotiating teams have not been able to keep up the agreed pace of negotia- tion and implementation. As a result, the parties will have to agree to an extension of the implementation period.

Responsibility for the delay is shared. On the one hand, the insurgency lacks enough qualified and reliable/trustworthy personnel to take on all the responsibilities derived from the transition. On the other hand, the government negotiating team has to deal with limited buy-in on both the agreement and its implementation by other sectors of the bureaucracy.

At the same time Congress has been dragging its feet in enacting the peace agreements into law, while the judiciary must still assess whether the agreements comply with the constitution. There is a high risk that these two state institutions will raise issues that may further block the implementation of the agreements that have been signed.

Furthermore, in the Philippines, prejudice against Muslims – a heritage from the colonial period – still runs deep.

With less than a year remaining until the country’s presidential and legislative elections (May 2016), some prominent politicians and media outlets are turning to populist rhetoric to antagonise public opinion against the peace process.

Even among better-intentioned political actors, a lack of knowledge about the social, political, and cultural reality of the insurgency in particular and the Muslim population in general results in faulty diagnoses and mistaken responses. Successive governments have associated the Moro problem with poverty and economic marginalisation, thus neglecting the relevance of identity and parity of esteem. On its part, the insurgency has been unable to articulate a political discourse that the whole country can understand and endorse. Only after patient dialogue have the peace negotiators deconstructed some of these erroneous imaginaries, but both the Christian and Muslim sectors of society still distrust each other.

The main security-related problem is the proliferation of arms and armed groups. One reason is that holding weapons is legal in the Philippines. Related to this, successive governments have failed in their attempts to disband paramilitary groups run by local politicians. There is also a proliferation of additional armed groups, which can be classified into three categories: an MILF breakaway group that is sceptical about the government’s political commitment (the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters); extremist cells linked to international extremist violence (Abu Sayyaf, Jemaa Islamiyah); and ordinary criminal organisations.

Other difficulties are inherent to any process of transition from war to peace. Apart from political will, the government needs to prove its capacity to transform words into deeds, which has historically proved to be a challenge. In parallel, the insurgency needs a radical paradigm shift from a semi-clandestine military structure to a social and political movement – a terrain in which it has limited experience and where to some extent it is at a disadvantage compared to more established political actors.

Lessons learned for other peace processes

Each peace process responds to a specific conflict that emerges for concrete reasons and in concrete circum- stances (social, political, cultural and temporal). However, comparative analysis is fundamental in every peace process. Some of the lessons from the Philippines could be relevant to other contexts:

- Peace is not a product, but a process. The transformative capacity of a peace agreement and its sustainability over time depend on its legitimacy, which in turn is dependent on the extent that social, political and economic actors feel a sense of ownership of the deliberative process leading to the peace agreements and their implementation.

- Negotiations are just one among multiple paths to peace. In parallel to the negotiations between the government and the insurgency, other dialogue processes must build or restore relations between sectors of society that have been or remained divided during the armed conflict. This is essential to achieving the social, political, economic and cultural transformations needed to overcome a protracted armed conflict.

- The current context demands efforts to facilitate the participation of historically excluded sectors such as women, victims and ethnic communities. Including these sectors greatly contributes to raising the international legitimacy of a peace process.

- The crises that emerge during negotiations are also opportunities to improve the mechanisms that support the talks.

- A government involved in a peace process must include the legislature and take into account the perceptions of the judiciary before the signing of an agreement. Constitutional amendments are the best guarantee to consolidate a country’s structural transformation.

- Giving an insurgency the opportunity to transform itself into a political movement free of coercion and threats is the best guarantee of the non-recurrence of armed conflict. Such an evolution can be enhanced by preventing the potential social and political isolation of the insurgency, as well as agreeing on transitional measures for the political participation of the insurgency before it can compete on equal terms with more established political movements.

- The decommissioning of arms by the insurgency, and the repositioning and reform of the government security sector are gradual and interdependent processes that contribute to confidence-building. The insurgency is aware that the hard-earned legitimacy it has gained as a peace actor can be lost with just one mistake in the management of its weapons, or if it does not allow the state to be fully present and perform its social, administrative and public order duties in the whole territory.

- The implementation of a peace agreement can be as difficult as the negotiations. In the Philippines, this has been managed through the creation of hybrid agreement implementation bodies that allow the joint and complementary work of national and international, civil and military, institutional and civil society actors.

- The implementation of a peace agreement implies an asymmetric power relationship that is favourable to the state. If an insurgent movement does not comply with the agreement, it loses legitimacy. If the state does not comply, the insurgency has limited means to apply pressure because a return to armed conflict is not an option.

- The international community plays a decisive role in accompanying and supporting the peace process. But its role is always secondary and does not replace national leadership. The agenda for negotiations, the time line, the design of consultations, the terms of reference for international support, and other fundamental elements of a peace process are exclusively in the hands of national actors.

About the author: *Kristian Herbolzheimer has more than 15 years of experience in peacebuilding affairs, first as the director of the Colombia Programme at the School for a Culture of Peace in Barcelona, and since 2009 as director of the Colombia and Philippines programmes at Conciliation Resources. As a member of the Mindanao International Contact Group he has acted as adviser to the peace negotiations between the government of the Philippines and the MILF insurgency for six years. He has a master’s in international peace studies and is a qualified agricultural engineer.

Source: This article was published by NOREF as December 2015 Report (PDF)

References: AFP (Armed Forces of the Philippines). 2010. Internal Peace and Security Plan “Bayanihan”. <http://www.army.mil.ph/ATR_Website/pdf_files/IPSP/ IPSP%20Bayanihan.pdf> Annex on Normalisation. 2014. <http://peacemaker.un.org/ sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/PH_140125_AnnexNormal- ization.pdf> Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro. 2014. <http://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/ PH_140327_ComprehensiveAgreementBangsamoro.pdf> Conciliation Resources. 2015. “Operationalizing women’s ‘meaningful participation’ in the Bangsamoro.” <http://www.c-r.org/resources/operationalising-womens- meaningful-participation-bangsamoro> Coronel-Ferrer, M. 2002. “Philippines National Unification Commission: national consultations and the ‘six paths to peace’.” In C. Barnes, ed. Owning the Process: Civil Society in Peace Processes. London: Conciliation Resources. Fisas, V. 2015. Yearbook on Peace Processes. Barcelona: Icaria. <http://escolapau.uab.es/img/programas/pro- cesos/15anuarii.pdf> Herbolzheimer, K. 2013. “Muslim women in peace processes: reflections for dialogue in Mindanao.” <http://www.c-r.org/resources/muslim-women-peace-pro- cesses-reflections-dialogue-mindanao> Human Security Report Project. 2012. Human Security Report 2012. <http://hsrgroup.org/docs/Publications/ HSR2012/HSRP2012_Chapter%206.pdf> ndependent Commission on Policing. 2015. Policing for the Bangsamoro. April 14th. Unpublished report commissioned by the peace panels of the government of the Philippines and the MILF. UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2015. 2015 Human Development Report: Rethinking Work for Human Development. <http://hdr.undp.org/en/rethinking- work-for-human-development>

Notes: 1 For more information about this innovative ICG, see <http://www.c-r.org/resources/practice-paper-innovation-mediation-international-contact-group-mindanao> 2 See the Annex on Normalisation (2014), which is included in this report’s list of references. 3 There is no official data about the numbers of detainees, but they are not large. 4 In the Philippines it is legal to bear arms, and disarmament affects mainly illegal arms. Legal weapons will need to be registered.

- ← Russia’s Policy In Middle East Imperilled By Syrian Intervention – Analysis

- Denmark Rejects Further EU Integration In Referendum →

The Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre/Norsk Ressurssenter for Fredsbygging (NOREF) is an independent foundation established to integrate knowledge, experience, and critical reflection into and thereby strengthen peacebuilding policy and practice. NOREF supports the development of competence and resources for peacebuilding efforts in the fields of conflict prevention, conflict resolution and post-conflict rehabilitation, as well as mediation and humanitarian actors in conflict-affected areas. In order to provide resources on peacebuilding, mediation and humanitarian issues to the Norwegian and the international peacebuilding community, the centre collaborates with a wide network of researchers, policymakers and practitioners.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Home > Journals > The Journal of Social Encounters > Vol. 4 (2020) > Iss. 2

Peace Education in the Philippines: Measuring Impact

Jasmin Nario-Galace , Miriam College

In this essay I discuss the education and experiences that were important for my formation as a Peace Educator and Advocate. The essay also briefly looks at the issue of peace research, teaching and activism, and how we at the Miriam College –Center for Peace Education believe that research and teaching are important but not enough. I recount research I helped to conduct that shows that peace education had a positive impact on those who participated in it, and then go on to describe our successful Iobbying efforts with the Philippine government and at the United Nations. I conclude with examples of peace activities by those we educated that encourage us to persevere in our peace education efforts.

Recommended Citation

Nario-Galace, Jasmin (2020) "Peace Education in the Philippines: Measuring Impact," The Journal of Social Encounters : Vol. 4: Iss. 2, 96-102. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/social_encounters/vol4/iss2/9

Since August 03, 2020

Included in

Anthropology Commons , Catholic Studies Commons , Christianity Commons , Ethics in Religion Commons , International Relations Commons , Islamic Studies Commons , Peace and Conflict Studies Commons , Politics and Social Change Commons , Race and Ethnicity Commons , Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons , Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons , South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons

- Journal Home

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Information for Authors

Recommended

- EXAMPLES OF SHARED ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN ACTIONS

- Environmental Peacebuilding Update Issue 264: 20 Feb 2024 News and Resources

- Climate Diplomacy Magazine Feb. 2024 News and Resources

- Alliance for Peacebuilding Newsletter February 22, 2024 News and Resources

- Catholic Peacebuilding Network News Brief February 26, 2024 News and Resources

- Most Popular Papers

- Receive Email Notices or RSS

Advanced Search

ISSN: 2995-2212

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Content Search

Philippines

Young people in the Philippines are building peaceful societies following the Bangsamoro peace agreement

- Islamic Relief

This International Day of Peace, discover how young people in the Philippines are overcoming walang pakialam (apathy) to embrace pagkakaroon ng pakialam (social engagement) in the push for peace in Mindanao.

Around the world young people are often sidelined in peace dialogues and peacebuilding work as political elites try to tackle the critical political, social and economic issues that give rise to conflict. Young people in the Philippines are no strangers to this.

"There was a time when I was angry with my family for giving birth to me in this place of unending armed conflict and violence," says Munisa, 21, who lives in Gawang barangay (village) in Datu Saudi Ampatuan district.

Like many other communities in her area, Munisa's village had experienced decades of conflict as armed groups clashed with government forces . The war left the Bangsamoro region in Mindanao with the worst human development indicators in the country.

"We did not know what peace is. I felt hopeless and saw no future for me, as war burned our house to the ground on two occasions, drove us from our community, and my studies were continuously disrupted," adds Munisa.

Young people typically disempowered

In their communities, most disputes, whether over land, violent attacks or marriages, were traditionally handled through community leaders, elders and faith leaders. Few young people were involved. Many say they felt their voices were not heard and that they had no confidence to contribute, since their communities saw this as the domain of adults.

Then Munisa joined an Islamic Relief peacebuilding project funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) . Some 50 young people took part in a peace camp, where they learned to strengthen social cohesion in their communities and understand the drivers of conflict and how to prevent them.

In addition to the camp the young people received training on dialogue, negotiation and mediation skills and were shown how to advocate for peace through writing, singing, social media and more.

Separate community-based sessions helped the young people to understand the broader considerations necessary to successfully resolve conflicts in their communities. Dedicated sessions with 180 young people focused on improving community cohesion through dialogue and community development.

Build lasting peace by leaving no-one behind

The Islamic Relief project sought to enable young people to overcome walang pakialam, a Tagalog term referring to the state of apathy, to pagkakaroon ng pakialam.

“Ang pagkakaroon ng pakialam is about caring for the members of the community,” explains Rehana, 21, of Magaslong village. “Caring means walang maiiwan (nobody is left behind).”

The project inspired Rehana and other young people to take action, she says.

“We have fed children and conducted cleaning of public places in the barangay and other civic activities. This builds harmony and unity among the people. In this manner conflict is avoided.”

Munisa was also motivated to contribute.

“The project rekindled my spirit,” she says. “I thought Allah may have a plan for me. Perhaps I have a role to play in the building of peace. Perhaps I could encourage my fellow youth to go back to school and build our future.”

Youth advocates empowered to support peace

Buoyed by her newfound knowledge and confidence, Munisa decided to become one of 30 youth peace advocates working across three districts. It is a key role, as 23-year old Namrah, another of the peace advocates, explains.

“As peace advocates, we help verify information every time there is [a rumour] about conflicts and the security situation and we share only correct information. We use social media and text messages to minimise the fear of our relatives and friends and guide them into proper actions to take.”

Determined to make sure that young people can contribute to peace in their communities, the advocates are already making progress. Some are now members of peace councils, others represent youth in negotiating with village officials and lobbying municipal government.

“I am using the local radio as a platform for peace advocacy,” says Noraisa 30, who lives in Talibadok. She now regularly guests on a local radio programme and has helped organise a youth group in her village to help them push for better public services.

Building much needed community cohesion

Though the Bangsamoro peace agreement has been in place since 2014, people remained hesitant to interact with those on opposing sides. So Munisa has been building bridges between communities in her village.

With friends on both sides, Munisa and her classmates decided to organise a 'boodle fight'. Held before Covid-19 social distancing restrictions, diners were invited to gather around a long table to eat food with their hands.

"We wanted to show our friends from both sides that it is alright and safe now to interact with one another, as the conflict has already been settled," she says, describing how the gathering removed boundaries between people as they enjoyed their meal, renewing friendships and sharing happy moments.

Islamic Relief believes that it is only possible to achieve lasting change if all marginalised groups are involved in the solution. Our peacebuilding work also includes empowering young people in countries such as Pakistan, Indonesia and Kenya.

With your support, we can continue to build bridges between communities and equip local people to secure lasting peace. Donate now.

Related Content

Dswd, opapru turn over pamana housing units to families in 2 zambo peninsula towns, calming the long war in the philippine countryside, dswd execs hold dialogue with ex-dawlah islamiyah members to improve peace and development programs, dswd, afp explore convergence efforts for peace initiatives.

Interview: the Struggle for Peace in Mindanao, the Philippines

The southern Philippines has known a long history of armed conflict. Among those regions is Mindanao, where in February 2019 the Bangsamoro people voted to ratify the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL). This law is a big leap towards peace in the Southern Philippines. To understand why this is such a big leap for peace we interviewed Marc Batac, who is the Regional Programme Coordinator at our member organisation Initiatives for International Dialogue (IID) in the Philippines. IID has been involved in the peace process in Mindanao for almost twenty years.

To give us an overview of the conflict in Mindanao: how did the conflict come about, what are the root causes, who are the main actors and what is it about?

The root cause of armed conflict in Mindanao can be found in the narrative of Mindanao peoples’ continuing struggle for their right to self-determination. A struggle that involves an assertion of their identity and demand for meaningful governance in the face of the national government’s failure to realise genuine social progress and peace and development in the southern Philippines. The struggle is also a response to “historical injustices” and grave human rights violations committed against the peoples of Mindanao.

With the clamor to correct these historical injustices and to recognise their inherent right to chart their own political and cultural path, the Bangsamoro people – together with their non-Moro allies – have struggled to get their calls heard and acted upon by the central government.

A huge number of the victims of the conflict in Mindanao have been ordinary civilians: women and men, young and old who were either displaced from their communities or killed in the crossfire by bullets and bombs that recognize no gender, religion, creed or stature.

There are two opposing views when it comes to the armed struggle in the Bangsamoro region: While the central government had earlier viewed the armed struggle as an act of rebellion against the state, the other party has always claimed it as a legitimate exercise of their right to self-determination.

Over the years, the State has come to recognise the Bangsamoro and Indigenous Peoples struggle for just and lasting peace in Mindanao, albeit always within the framework of the country’s constitution.

A huge number of the victims of the conflict in Mindanao have been ordinary civilians: women and men, young and old who were either displaced from their communities or killed in the crossfire by bullets and bombs that recognize no gender, religion, creed or stature. The impact and social cost of the decades-old war to the people and the entire nation have been vicious and costly. The infographic on the cost of war in Mindanao (see below) explains previous Philippine governments’ huge spending on wars in Mindanao, which clearly talks about ‘lives lost’ rather than ‘lives improved’. Finding peaceful solutions to the causes of the armed conflict in Mindanao is never easy as the toll has affected not just Mindanao but the entire country. This has discouraged foreign and local investments and ultimately bleeding the nation’s coffers with the previous governments spending more on war than on basic social services.

While previous governments tried to resolve these conflicts, the root cause is the failure to address the Mindanao peoples legitimate struggle for their ‘right to self-determination, dignity and governance’, and is a major challenge to achieving sustainable peace in the region.

The conflict between the Government of the Philippines and the armed groups in Mindanao, particularly the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), is not the only conflict affecting the whole region. The conflict in Mindanao is multi-faceted, involving numerous armed groups, as well as clans, criminal gangs and political elites. Main actors to this decades-old conflict are: the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and other groups such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), Abu Sayyaf (considered a bandit group engaged in various criminal activities like kidnapping and bombings), as well as other armed non-state actors who are consistently ‘in conflict’ with the central government.

The Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) has been passed, which is for now the successful conclusion of a peace process. Can you explain what this is? And how it happened?

The purpose and intent of the law is to establish the new Bangsamoro political entity and provide for its basic structure of government. This also includes an expansion of the territory in recognition of the aspirations of the Bangsamoro people. Said law provides that the Bangsamoro Government will have a parliamentary form of government. The two key components of the peace process that will determine its eventual success are the passing of the BOL and the plebiscite for its ratification in the proposed Bangsamoro territory. With the BOL passage comes a roadmap that outlines a smooth transition leading to the creation of the Bangsamoro government that promises to fulfil the Bangsamoro’s aspirations for peace, justice, economic development and self-governance. The new Bangsamoro political entity will in effect abolish the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) and provide for a basic structure of government in recognition of the justness and legitimacy of the cause of the Bangsamoro people and their desire to chart their own political future through a democratic process.

The BOL is a product not only of political negotiations between the Bangsamoro and the Philippine government through their respective principals and negotiators but of the peacebuilding community’s decades of peacemaking and conflict prevention work and initiatives, both inside and outside of Mindanao and the Philippines.

What has civil society, and particularly Initiatives for International Dialogue (IID), done for this peacebuilding process? And why is it important?

IID became more involved into the Mindanao peace process when then President Joseph Estrada unleashed an “all-out war” against the MILF in 2000 that resulted in countless deaths, wounded and massive dislocation of mainly Moro communities. IID’s Moro and Mindanao partners sought the assistance of civil society and IID in helping to galvanize a response and projection of their voices and perspectives into the entire peace process. IID then proceeded to establish platforms and networks to concretize this accompaniment, forming the Mindanao Peoples Caucus (MPC) – a Tri-people (Moro, settlers and Indigenous peoples) network that engaged the peace process. MPC in turn established the Bantay Ceasefire (Ceasefire Watch) – a grassroots and community-based ceasefire-monitoring network.

GPPAC Southeast Asia members in the Philippines have been in the forefront of engaging the peace process in Mindanao since the “all-out war” declared by then President Estrada in 2000 against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

Eventually, IID together with its partner communities were able to go through consensus building and lobbied in Congress a civil society agenda on crucial provisions in the draft BBL, conducted public advocacy activities and engaged lawmakers and the media.

Why is this such a big win for peace in the Philippines and the region?

GPPAC Southeast Asia members in the Philippines have been in the forefront of engaging the peace process in Mindanao since the “all-out war” declared by then President Estrada in 2000 against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). It has since initiated and helped establish various networks for peace in the country, including Bantay Ceasefire, Mindanao Peaceweavers (MPW), Friends of the Bangsamoro (FoBM) and All-Out Peace (AOP) among others.

For us, the enactment of BOL is major step forward in achieving a just and sustainable peace in Mindanao. The BOL, if implemented according to its intent and purpose, could finally open a smooth path towards peace, development and social progress in the south of the Philippines. A product of a long-drawn peace negotiation, it also serves as a 'justice instrument', which can help in correcting historical injustices committed against the Bangsamoro people, the indigenous peoples, and other inhabitants of Mindanao--injustices that continue to haunt them up to this day.

The BOL, if implemented according to its intent and purpose, could finally open a smooth path towards peace, development and social progress in the south of the Philippines.

For numerous decades, Mindanao and its peoples have witnessed the exceptional savagery of armed conflict. The results have been equally vicious: from the unending cycle of multiple displacements by hapless communities to depleting our nation's fiscal health. In all these armed conflicts happening around Mindanao, the most marginalized and vulnerable especially our women, children and the elderly, were made to endure the profound and unceasing pains of conflicts they never wished to be part of. Now that the BOL has been successfully ratified, and the installation of a transition structure through the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) is underway, prospects towards a significant improvement in the lives of the peoples of Mindanao and hopefully in the whole country as well.

Are you hopeful that this change will be sustainable for a more peaceful Mindanao? And what needs to be done now?

While the ratification of the BOL and the eventual establishment of the Bangsamoro government are significant political milestones towards realising just peace and social progress not only for Mindanao but for the whole country, we believe that it is not the end-all and be-all of the struggle for peace. What still needs to be addressed during the process are difficult issues around governance, inclusion, land distribution, incursion of foreign aid, dealing with shadow economies and violent extremism in a fragile peace process. The promise of a more enhanced and meaningful autonomy can reach its full potential if a peacebuilding strategy, coupled with participation and protection pathways, is substantively embedded in governance in the incipient Bangsamoro. Civil society has to develop what is now a “post-conflict peacebuilding” paradigm, wherein we have to locate our role and added value during political transition around hard and intractable issues around land, governance, transitional justice and security.

Peace monitoring will continue to be a staple strategy fulfilling civil society’s role as a third party in the peace process. There are other aspects of the law that must be monitored and ensured especially when the “caretaker” BTA starts its job weeks from now, including how in the transition period the normalization programs will be equally supported and cascaded to ensure decommissioning of the MILF forces and support to these combatants and amnesty, transformation of camps and conflict-affected communities. This, of course, will entail bringing to the Normalization table the issues on displacement and post-reconstruction of those IDPs during the sieges in Zamboanga and Marawi cities, including the displaced indigenous communities due to intermittent armed hostilities in ancestral domain areas in the BARMM.

Civil society has to develop what is now a “post-conflict peacebuilding” paradigm, wherein we have to locate our role and added value during political transition around hard and intractable issues around land, governance, transitional justice and security.

Lastly, a whole of society approach in developing and implementing government programs in the BARMM shall respond to social cohesion, trust building and work on inclusion of minority and minoritized issues concerning the IPs in the region and the Christian population. From a civil society’s perspective, it is not a mere governance issue that is at stake here, but actualising the negotiated consensus (BOL, FAB/CAB, and all previously signed peace agreements) and the essence of social justice by guaranteeing affirmative action every step of the way. The civil society scorecard should be designed to critically monitor the following:

- Realizing meaningful autonomy and right to self-rule of the Bangsamoro (and the inhabitants of the region) based on their distinct cultural identities, historical struggle, faiths, heritage and traditions;

- Grant genuine and efficient fiscal autonomy for the Bangsamoro;

- Provide the Bangsamoro effective management and control over and benefits of the natural resources in the Bangsamoro territory;

- Full Inclusion of the Indigenous Peoples rights in the Bangsamoro governance to ensure the recognition and protection of their rights and to correct historical marginalization and exclusion; and

- Realizing a transitional justice and reconciliation program for the Bangsamoro. Heed previous recommendations to establish a Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission for the Bangsamoro (NTJRCB) that shall among others ensure and promote justice, healing and reconciliation.

- the Philippines

- Southeast Asia

Share this article on

Related highlights.

A Light at the End of the Tunnel? Moving Forward in the Philippines Peace Process

GPPAC Encourages Continued Peace Talks in the Philippines: “Peace talks are paramount for the sustainable future of the Philippines”

GPPAC Statement on Philippines Peace Process

Talk ain’t cheap when keeping the peace.

Document Retrieval

Tripoli agreement.

The agreement establishes autonomy in the Southern Philippines within the realm of sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of the Philippines. It defines the autonomous territory and delineates the competence of the central and regional governments.

Essay on Peace

500 words essay peace.

Peace is the path we take for bringing growth and prosperity to society. If we do not have peace and harmony, achieving political strength, economic stability and cultural growth will be impossible. Moreover, before we transmit the notion of peace to others, it is vital for us to possess peace within. It is not a certain individual’s responsibility to maintain peace but everyone’s duty. Thus, an essay on peace will throw some light on the same topic.

Importance of Peace

History has been proof of the thousands of war which have taken place in all periods at different levels between nations. Thus, we learned that peace played an important role in ending these wars or even preventing some of them.

In fact, if you take a look at all religious scriptures and ceremonies, you will realize that all of them teach peace. They mostly advocate eliminating war and maintaining harmony. In other words, all of them hold out a sacred commitment to peace.

It is after the thousands of destructive wars that humans realized the importance of peace. Earth needs peace in order to survive. This applies to every angle including wars, pollution , natural disasters and more.

When peace and harmony are maintained, things will continue to run smoothly without any delay. Moreover, it can be a saviour for many who do not wish to engage in any disrupting activities or more.

In other words, while war destroys and disrupts, peace builds and strengthens as well as restores. Moreover, peace is personal which helps us achieve security and tranquillity and avoid anxiety and chaos to make our lives better.

How to Maintain Peace

There are many ways in which we can maintain peace at different levels. To begin with humankind, it is essential to maintain equality, security and justice to maintain the political order of any nation.

Further, we must promote the advancement of technology and science which will ultimately benefit all of humankind and maintain the welfare of people. In addition, introducing a global economic system will help eliminate divergence, mistrust and regional imbalance.

It is also essential to encourage ethics that promote ecological prosperity and incorporate solutions to resolve the environmental crisis. This will in turn share success and fulfil the responsibility of individuals to end historical prejudices.

Similarly, we must also adopt a mental and spiritual ideology that embodies a helpful attitude to spread harmony. We must also recognize diversity and integration for expressing emotion to enhance our friendship with everyone from different cultures.

Finally, it must be everyone’s noble mission to promote peace by expressing its contribution to the long-lasting well-being factor of everyone’s lives. Thus, we must all try our level best to maintain peace and harmony.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Peace

To sum it up, peace is essential to control the evils which damage our society. It is obvious that we will keep facing crises on many levels but we can manage them better with the help of peace. Moreover, peace is vital for humankind to survive and strive for a better future.

FAQ of Essay on Peace

Question 1: What is the importance of peace?

Answer 1: Peace is the way that helps us prevent inequity and violence. It is no less than a golden ticket to enter a new and bright future for mankind. Moreover, everyone plays an essential role in this so that everybody can get a more equal and peaceful world.

Question 2: What exactly is peace?

Answer 2: Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in which there is no hostility and violence. In social terms, we use it commonly to refer to a lack of conflict, such as war. Thus, it is freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Essay on Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines

Students are often asked to write an essay on Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines

Who are indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples are the first people to live in a place. In the Philippines, they have their own cultures, languages, and traditions. They live in mountains, forests, and islands. They are also called “Lumad” and “Igorot” among other names.

Where They Live

Many indigenous groups in the Philippines live in Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. They stay in remote areas, which helps them keep their old ways of life. Their homes are often far from cities and hard to reach.

Their Way of Life

These peoples farm, hunt, and fish for food. They respect nature and believe in spirits. They also have colorful clothes, dances, and music that show their culture.

Challenges They Face

Indigenous peoples have problems like losing their land and not having enough rights. Some people don’t respect their way of life, and they struggle to keep their traditions alive.

Protecting Their Rights

The Philippines has laws to protect these peoples. It’s important to make sure they can keep their land, culture, and way of life. Everyone should learn about and respect their contributions to the country’s heritage.

250 Words Essay on Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines

In the Philippines, indigenous peoples are groups of people who have lived in the country for a very long time, even before others came to the islands. They have their own ways of life, languages, and traditions that are different from the rest of the population.

Where Do They Live?

These native groups live in various parts of the Philippines, from the mountains of Luzon to the islands of Mindanao. Some live in forests, while others are by the sea. Each group has learned to live well in their special home environment.

Their Culture and Traditions

Indigenous peoples in the Philippines have rich cultures. They celebrate unique festivals, have their own music, dances, and clothes. They also have special skills in weaving, carving, and making houses that fit their lifestyle. Their beliefs and stories are passed down from old to young, keeping their history alive.

Sadly, these groups often face tough times. Their lands are sometimes taken away for business or other people’s use, which makes it hard for them to live as they always have. They also struggle to keep their culture strong while the world around them changes quickly.

Why They Are Important

Indigenous peoples are very important because they teach us about different ways of living and thinking. Their knowledge of nature and how to care for it is valuable for everyone. It is important to respect and protect their rights so they can continue their way of life and share their wisdom with all of us.

500 Words Essay on Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines

Who are the indigenous peoples in the philippines.