- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

4 things you need to know about water and famine, millions of children are facing the deadly effects of drought, including acute hunger, malnutrition and thirst..

- Available in:

Conflict, climate change and poverty are driving massive humanitarian crises, leaving millions at risk of famine. Children are the most vulnerable during periods of famine and extreme food insecurity, facing a greater likelihood of severe malnutrition and death. These crises also produce irreversible, life-long consequences for children, leading to severe health and development challenges.

When we think of famine, we often think of a lack of food. But increasingly, the crisis is one not only of food insecurity, but also of clean water, sanitation and health care – especially disease prevention and treatment. Water and sanitation are just as important as food for children and families facing famine and food insecurity. Here are four reasons why:

1. Disease and malnutrition

Unsafe water and sanitation can lead to malnutrition or make it worse. “No matter how much food a malnourished child eats, he or she will not get better if the water they are drinking is not safe,” says Manuel Fontaine, UNICEF Director of Emergency Programmes. Unsafe water can cause diarrhoea, which can prevent children from getting the nutrients they need to survive, ultimately leading to malnutrition. Malnourished children are also more vulnerable to waterborne diseases like cholera. Inadequate access to minimum water, hygiene, and sanitation is estimated to account for around 50 per cent of global malnutrition.

2. Climate change

Climate change and extreme weather events like droughts and floods can deplete or contaminate water supplies. This threatens both the quality and the quantity of the water that entire communities rely on. As families in areas of extreme water stress compete for scarce or unsafe water sources, they are driven from their homes, increasing their vulnerability to disease and protection risks.

Globally, over 1.42 billion people, including 450 million children, live in areas of high or extremely high water vulnerability. The Horn of Africa is facing the worst drought the region has seen in 40 years . Three consecutive dry seasons have driven hundreds of thousands of people from their homes, killed vast swathes of livestock and crops, and fuelled malnutrition.

3. Conflict

Conflict is often the main factor driving the threat of famine, putting strain on food and water supplies, as well as health systems. The war in Ukraine, for example, has driven up food and fuel prices in places where children are already going hungry. And all too often, the human dependence on water has been intentionally exploited during armed conflict, with water resources and the systems required to deliver drinking water coming under direct attack.

Nearly all of the conflict-related emergencies where UNICEF has responded in recent years have involved some form of attack hindering access to water, whether intentionally directed against water infrastructure or incidentally. For young children especially, the consequences of these disruptions can be deadly. In protracted conflicts, children under 5 are more than 20 times more likely to die from diarrhoeal disease linked to unsafe water and sanitation than violence in conflict.

4. Displacement

When fighting or drought force people from their homes, children and families become more vulnerable both to abuses and to health threats. On the move , children often have no choice but to drink unsafe water. Makeshift camps set up without toilets become hotspots for disease outbreak. Children who are already vulnerable are more susceptible to diseases, and are often unable to access hospitals and health centres as they flee. Around 9.2 million people are displaced across the four famine-threatened countries.

How UNICEF is helping

UNICEF’s support to children and their families includes immediate lifesaving interventions and building resilience over the long term. Included in these are:

- Working with partners on building resilience for communities affected by high or extremely high water vulnerability, in part through groundwater extraction. Drilling for reliable sources of ground water could transform the lives of at least 70 million children in the Horn of Africa who live in areas where access to water is extremely precarious.

- Exploring longer-term solution through regional initiatives. Safe and sustainable sources of water that prevent illness, withstand the impacts of climate change, and allow families to stay in their communities, where children can access their schools and primary healthcare services.

- Developing monitoring and early warning systems. Timely information that alerts governments and communities to rising risks of climate and environmental and hazards, allowing for immediate action to prevent future crises.

- In Somalia, UNICEF is working with the government and partners to provide vital interventions as part of its response to the drought, including providing therapeutic foods to treat acute malnutrition and micronutrients to tackle deficiencies, as well as counselling to encourage families to adopt practical nutrition and health practices at home. UNICEF had also provided around 480,000 people with temporary access to emergency water in the first three months of 2022.

- In 2021, UNICEF reached more than 3 million people in Kenya with access to safe water for drinking, cooking, and personal hygiene, provision of WASH supplies, household water treatment, hygiene promotion and improved sanitation.

Related topics

More to explore.

UNICEF Geneva Palais briefing note on threat of famine for children in Somalia

Children suffering dire drought across parts of Africa are ‘one disease away from catastrophe’ – warns UNICEF

UNICEF Emergency Director, Manuel Fontaine, visits drought stricken Somali region and calls for an immediate scaled up humanitarian response to save millions of children

Child alert: Severe wasting

Also known as severe acute malnutrition, severe wasting is an overlooked but devastating child survival emergency

- Ideas for Action

- Join the MAHB

- Why Join the MAHB?

- Current Associates

- Current Nodes

- What is the MAHB?

- Who is the MAHB?

- Acknowledgments

Overpopulation and water scarcity leading to world future food crisis

| July 12, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Permaculture by Local Food Initiative | Flickr

Author(s): Gioietta Kuo

OVERPOPULATION

The future of our food supply should undoubtedly be the number one concern of our world today. What affects this future food supply? It is well known that the world is already overpopulated today at 7.7 billion and is predicted to have 9.7 billion in 30 years time in 2050. This is destined to happen irrespective of what measures we take today. Only after 2050 may we expect a leveling off if we adopt sensible steps[1].

Apart from food, water is the other essential element for our existence, Water is consumed throughout the food production process, from growing the animal’s food and the drinking water animals drink, to the overall meat production process.

To produce enough food to sustain the planet’s population, it is estimated that 52,8 millions of water per second are required [2] Of our total water consumption, food accounts for roughly 66%. It is ubiquitously hidden in everything we consume. For example one needs

- 240 gallons of water to produce a loaf of bread

- 46 gallons to produce a soda

- 12 gallons for a serving of potato chips

- 108 gallons to produce a gallon of tea from planting

- 1956 gallon to produce coffee

- 872 gallons for one gallon of wine and 296 gallons for one gallon of beer

- Subsidiary products like eggs requires 496 gallons , a pound of cheese requires 483 gallons and a pound of butter 665 gallons 122 gallons for 2 pints of milk

- other items like fruit juice requires gallons of water

According to a UN water scarcity report[3] over 2 billion people live in countries experiencing high water stress. It is estimated that by 2040 some 600 million children will be living in areas of extremely high water stress leading to maybe 700 million people being displaced worldwide.

Typical values for the volume of water required to produce common foodstuffs [4]

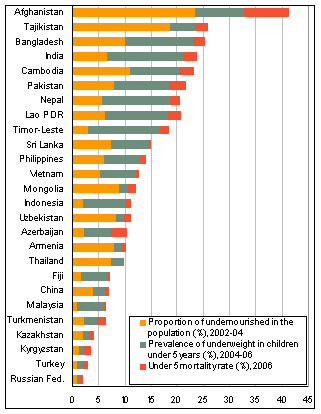

WORLD HUNGER

Although in principle enough food is produced around the world to feed more than enough the global population. But according to Unicef 2019 [5] more than 820 million people go hungry each year.

Factors which contribute to hunger are strongly related to overpopulation and poverty. This involves interactions among an array of social, political, demographic, and societal factors. People living in poverty frequently face household food insecurity, use inappropriate care practices, live in unsafe environments that have low access to quality water, low sanitation, hygiene, and inadequate access or availability to health services and education. Conflict is also a key driver of severe food crises. This includes famine—a fact officially recognized by the UN Security Council in May 2018[3] 4 . Hunger and undernutrition are much worse when conflicts are prolonged and political institutions are weak. Unfortunately the number of conflicts is on the rise today, worsened by climate change. Some have also impacted food availability in many countries and thus contributed to the rise of food insecurity.

This underscoring the immense challenge of the UN Zero Hunger target by 2030. Hunger is on the rise in almost all African subregions leading to Africa having the highest prevalence of undernourishment in the world. The Unicef report calls for actions to safeguard food security and nutrition through economic and social policies that counteracts slowdowns, providing social safety nets and ensuring universal access to health, education, and contraception. Basically one should tackle inequalities to ensure sustainability at all levels of society.

Overpopulation increases uncontrolled urbanization and expansion of cities leading to more infrastructure and using up of resources. At the same time, this increases carbon dioxide emission Into the atmosphere resulting in more climate change. It is imperative to reduce fossil fuel, adopt alternative renewable energy and nuclear power.

EARTH CARRYING CAPACITY

How Many People Can It Support?

According to Harvard’s food expert Edward O. Wilson if everyone became vegetarian then the carrying capacity could be 10 billion as far as food is concerned.

Already we have hit a limit in measuring the ecological footprint of this burgeoning population – the amount of biologically productive land and water a person requires for producing the resources it consumes.

According to the UN food and agriculture organization, 11% of our land surface is being used for growing crops. An even bigger area is being employed for livestock grazing since water is essential for the food we produce.

We have to feed more than 9.7 billion people in less than 30 years. This is an increase of 25% from the current population. Yet many say we need to produce may be 35% in food. This estimate highlights a stark challenge for the global food system. The world is getting richer, especially the developing populous countries of China and India. There is a demand for eating high protein meat products. In China pork is the much preferred meat. While India remains a predominantly a vegetarian nation, there is a growing demand for beef and seafood in coastal regions.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, water used for livestock production is expected to rise by 50 per cent by 2025 and at present it accounts for 15 per cent of all irrigated water.

The global average water footprint of beef is 15,400 liters per kilo, which is predominantly green water – water from renewable sources – (94 percent).

The water footprint related to animal feed takes the largest share with 99 percent of the total consumption, while drinking and service water contribute just one per cent to the total water footprint.

However, drinking water is 30 percent of the blue water footprint.

To achieve this life satisfaction for the ever increasing population will demand a constraint on economic social governmental policies.

According to the United Nations, water use has grown at more than twice the rate of population increase in the last century. By 2025, an estimated 1.8 billion people will live in areas plagued by water scarcity, with two-thirds of the world’s population living in water-stressed regions as a result of use, growth, and climate change. The challenge we now face as we head into the future is how to effectively conserve, manage, and distribute the water we have not only in the US but across the globe. In fact, agricultural withdrawals account for 69% of water use around the world.

The food crisis is more complex and National Geographic has published an excellent article highlighting 5 necessary steps for managing the future food crisis [ 6]. We list here briefly the 5 steps to follow:

- Increase agriculture. Agriculture is among the greatest contributors to global warming. It has cleared forests and grasslands and reduced biodiversity, There are 2 concepts as to how to manage and control agriculture. Conventionally we use modern mechanization on a large scale, with irrigation, fertilizers, pesticides and modern genetics in seeds. This method should increase yields. The other concept is based on local and organic farms which increase demands and help themselves out of poverty – by adopting techniques that improve fertility without synthetic fertilizers and. pesticides.

Industrial agriculture, along with subsistence agriculture, is the most significant driver of deforestation in tropical and subtropical countries, accounting for 80% of deforestation from 2000-2010. Upward of 50,000 acres of forests are cleared by farmers and loggers per day worldwide and a large part is destroyed in the Amazon basin. This extreme clearing of land, especially for animal agriculture, results in habitat loss, amplification of greenhouse gases, disruption of water cycles, increased soil erosion, and excessive flooding.

The current contribution of agriculture to deforestation varies by region, with industrial agriculture being responsible for 30% of deforestation in Africa and Asia, but close to 70% in Latin America. The most significant agricultural drivers of deforestation include soy, palm oil, and cattle ranching.We have already cleared an area the South America to grow crops . And to raise livestock an area the size of Africa. So we can no longer afford to increase food production through agriculture expansion. In fact most of agriculture is used to produce cattle, soybeans for livestock, timber and palm oil. We must avoid further deforestation. Industrial farming has already used you large tracts of land. We should look to organic farming on smaller plots with individual farmers which not only increase yields but left themselves out of poverty.

- Grow more on the farms we have

In Africa, Latin America and Eastern Europe, we can try to increase yields on less productive farmlands by using high tech precision farming systems. With techniques taken from organic farming, such as computerized weather forecasting, exact matching of fertilizers to the soil, drip feeding irrigation and etc, we can boost yields by several times.

- Use resources more efficiently

Today’s commercial farming has started to make huge strides, finding innovative ways to better target the application of fertilizers and pesticides by using computerized tractors equipped with advanced sensors and GPS. Many growers apply customized blends of fertilizer tailored to their exact soil conditions, which helps minimize the runoff of chemicals into nearby waterways.

Organic farming can also greatly reduce the use of water and chemicals—by incorporating cover crops, mulches, and compost to improve soil quality, conserve water, and build up nutrients. Many farmers have also gotten smarter about water, replacing inefficient irrigation systems with more precise methods, like subsurface drip irrigation. Advances in both conventional and organic farming can give us more “crop per drop” from our water and nutrients.

4. Shift diets Why is it that to feed an extra 25% of populations in 2050 we are talking about increasing food production by 50-100 %? It is because today only 55% of the world’s crop calories feed people directly, the rest are fed to livestock( about 36%) or turned into biofuels and industrial products ( around 9%). For every 100 calories of grain we feed animals, we get only 40 new calories of milk, 22 calories of eggs, 12 of chicken, 10 of pork and 3 of beef. Finding more efficient ways to grow meat and shifting to less meat intensive diets could free up a large number of food for the world. See the previous chapter on the Earth’s carrying capacity and shifting to diets using less water. As we have mentioned, the world is getting richer, especially developing countries in China and India. There is a growing demand for high calorie meats. A shift to soybean based diets would better provide for the world’s overpopulation.

5. Reduce waste

Between 500 and 4,000 liters of water are required to produce 1kg of wheat. According to the UK Institution of Mechanical Engineers(IME) [4], as much as 2 billion tonnes of food are wasted every year – equivalent to 50% of all food produced. This means 30-50% (1.2 – 2 billion tonnes) of total food produced every year is lost before reaching a human mouth. In poor countries food is often lost from the farmer due to unreliable storage and transportation. Of all the steps for increasing food for mouths to feed, surely reducing waste is the most direct and effective way?

The publication entitled ‘Global food: waste not, want not’ also aims to highlight the wastage of energy, land and water. Approximately 3.8 trillion cubic meters of water is used by humans annually with 70% being consumed by the global agriculture sector. The amount of water wasted globally in growing crops that never reach the consumer is estimated at 550 billion cubic meters.

IME claim that water requirements to meet food demand in 2050 could reach between 10-13.5 trillion cubic meters per year – about triple the current amount used annually by humans.

—————————————————————————————————

In sum, there is a limit to large scale conventional industrialize farming. We should. use more organic farming using modern techniques of weather forecasting, sensors, GPS, matching of fertilizers to soil, subsurface drip irrigation and prevent runoff.

Most of all, we should reduce waste which at the moment is half what the world produces.

The National Geographic in its article [6} on feeding 9 billion has produced many succinct ideas.in how to overcome the impending future food crisis for the planet. Its conclusion is excellent. We are living at a pivotal moment in history. So far, in history we have adopted the philosophy of more and more food to feed the growing overpopulation. This we do by deforestation and increasing agriculture. But time has come for serious reflection. We cannot continue on this route. We have to change our mind set – To eliminate the vast food wastage at the same time to switch to a more vegetarian diet to release the pressure on meat eating. Most importantly we should improve our food security worldwide – to mitigate the source of our crisis – overpopulation and water scarcity.

—— ———————————————————————-

[1] Growing Global Overpopulation and Migration are Destabilizing our World, Gioietta Kuo,

https://mahb.stanford.edu/library-item/growing-global-overpopulation-migration-destabilizing-world/

[2]. Food and Water: How Much is Needed to Produce Our Food … https://www.the71percent.org/what-is-needed-to-produce-our-food/

[3] https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/scarcity/

World Water Development Report 2020 | UN – Water https://www.unwater.org/publications/world-water-development-report-2020/

[4] How much water is needed to produce food and how much do … https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2013/jan/10/how-much-water-food-production-waste Jan 10, 2013 … Meat production requires a much higher amount of water than vegetables. IME state that to produce 1kg of meat requires between 5,000 and …

[5] World Hunger , Poverty Facts, Statistics 2018 – World Hunger … The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2019 …

www.unicef.org/reports/state-of-food-security …

https://www.worldhunger.org/world-hunger-and-poverty-facts-and-statistics/

[6[ Feeding 9 Billion | National Geographic

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/foodfeatures/feeding-9-billion/

The future is equal

What is famine? Causes and effects and how to stop it

Confronting a despicable and avoidable human tragedy.

When a global report last month revealed that 300,000 families in northern Gaza are facing the threat of “imminent” famine, it was a frightening call to action. In nearly two-thirds of households, people went entire days and nights without eating at least 10 times in the last 30 days.

Wrought by conflict and violence, this hunger crisis in the making was unprecedented. “Palestinians in Gaza are enduring horrifying levels of hunger and suffering...” said Antonio Guterres, the U.N. secretary general. “This is the highest number of people facing catastrophic hunger ever recorded.”

At Oxfam, we’ve been focused on the fight to end hunger since our founding. So, we’re going to define what exactly is famine, what causes it, share an example of a famine, and explain how people like you can help stop famine in its tracks.

You can help save lives

Your contribution to Oxfam’s work will help save lives in Gaza and support long-term efforts to fight inequality and reduce poverty in more than 80 countries.

What does famine mean?

According to researchers Dan Maxwell and Nisar Majid, famine is “an extreme crisis of access to adequate food.” Visible in “widespread malnutrition” and “loss of life due to starvation and infectious disease,” famine robs people of their dignity, equality, and for some—their lives.

So how do we know a famine is occurring? The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, or IPC, is a common global scale that informs how governments and aid groups should respond when people lose reliable access to sufficient, affordable, and nutritious food. It’s a five-phase warning system to inspire urgent action before it’s too late.

For a famine to exist in a given area—Phase 5 of the acute food insecurity scale— three conditions, backed by evidence, must be met:

- 1 in 5 households faces an extreme food shortage

- More than 30 percent of children are “acutely malnourished,” a nutritional deficiency that results from inadequate energy or protein intake

- Death rates exceed two adults or four children per day for every 10,000 people

As of right now, famine has not been declared in northern Gaza. But according to the IPC, evidence supports that famine could occur anytime between now and May. By mid-July of this year, the number of people on the brink of famine in all of Gaza is expected to reach 1.1 million people.

What causes a famine?

Famines are usually caused by multiple factors. Since 2020, a deadly combination of conflict, COVID-19, and climate change has dramatically increased the number of people suffering from severe hunger. When compounded by inaction or policy decisions that make people more vulnerable, famine can result and society can collapse.

In Gaza, many challenges are putting people on the brink of famine:

- Following the attack by Palestinian armed militants on October 7, Israel’s bombardment of Gaza has resulted in widespread damage to assets and infrastructure critical for health and food production and distribution.

- Israel’s tightening of the siege on Gaza and systematic denial of humanitarian access to and within the Gaza Strip continues to impede the safe and equitable delivery of lifesaving humanitarian assistance.

- Aid workers in Gaza are being killed and are unable to safely deliver humanitarian aid, increasing the risk of famine.

Political scientist Alex de Waal calls famine a political scandal, a “catastrophic breakdown in government capacity or willingness to do what [is] known to be necessary to prevent famine.” When governments fail to prevent or end conflict —or help families prevent food shortages brought on by any reason—they fail their own people.

What is an example of a famine?

The 1984 Ethiopian famine took the lives of 1 million people , driven in part by drought, conflict, and the policy choices of national and regional authorities. Estimates suggest around 1 million people survived thanks to the delivery of humanitarian aid.

On the evening of Tuesday, October 23, 1984, NBC Nightly News aired footage taken by an Ethiopian videographer that showed scores of deceased people on stretchers that were being taken toward makeshift graveyards. Though the scenes inspired a robust international response, its nature overlooked the capacity of communities affected by the famine to help themselves.

By the next morning, Oxfam America had received over 300 calls an hour from people like you who wanted to help. During the relief effort, feeding centers provided hungry people with food rations. Makeshift hospitals supported severely dehydrated people with IVs, providing shots of tetracycline to fight infection. Oxfam delivered protein and fat-fortified biscuits to those in need that saved many lives, but some could not eat them—their mouths riddled with open sores because of dehydration.

“These scenes of death and dying in the famine camps in Ethiopia were beyond the American experience, beyond anyone’s comprehension,” recalls Bernie Beaudreau , an Oxfam staffer at the time.

Can famine be stopped?

Famine can be stopped—now, and in the long term . But governments and aid groups must anticipate a worsening hunger crisis, secure the resources and political will to address the root causes of hunger, and safely deliver humanitarian aid to those most in need.

In Gaza and countries like Somalia, Yemen, Ethiopia, and Madagascar, Oxfam is working to reduce the likelihood of famine with people like you. Here are some ways you can support Oxfam’s work:

- Stomach ailments from dirty water rob people of good nutrition from whatever food they can find, and young children are particularly vulnerable. That’s why Oxfam helps improve and repair wells to access clean water as well as trucks in water to areas where there is none.

- Good sanitation and hygiene are essential for preventing the spread of diseases like cholera, Ebola, and COVID-19. Oxfam helps construct latrines and distributes hygiene items like soap so people can wash their hands.

- When food is available in markets, but might be scarce or very expensive for some, Oxfam distributes cash to help buy food. Oxfam also distributes emergency food rations when necessary.

- In areas where farmers can plant crops, Oxfam supplies seeds, tools, and other assistance so people can grow their own food. We also help farmers raising livestock with veterinary services, animal feed, and in some cases, we distribute animals to farmers to help restock their herds .

- We help build the capacity of local organizations to respond to emergencies like famine, shifting power from international organizations to leaders rooted in local know-how. We promote the leadership of our local partners and boost their skills to reduce suffering, risks, and losses by preparing their own communities before disasters strike.

- Oxfam and our supporters advocate for peace and push for sufficient assistance for people affected by war and famine. Our research and advocacy also advance sustainable development in ways that help reduce the risk of future food crises and disasters.

Now you know what famine is

Join Oxfam to help stop famine in its tracks in Gaza right now.

Related content

Sudanese refugees fleeing conflict find refuge in South Sudan

Oxfam is working with partners to assist people from Sudan crossing the border to South Sudan, seeking safety from conflict.

The Future of Food

How Oxfam and our partners are working with people and communities to rethink the way we produce, process, and distribute the world's food.

How will climate change affect agriculture?

Climate change is affecting agriculture, but we can reduce climate-warming emissions and help farmers adapt to ensure we have nutritious food in the future.

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Climate Change

- Policy & Economics

- Biodiversity

- Conservation

Get focused newsletters especially designed to be concise and easy to digest

- ESSENTIAL BRIEFING 3 times weekly

- TOP STORY ROUNDUP Once a week

- MONTHLY OVERVIEW Once a month

- Enter your email *

Water Scarcity in Africa: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

The problem of water scarcity has cast a shadow over the wellbeing of humans. According to estimates, in 2016, nearly 4 billion people – equivalent to two-thirds of the global population – experience severe water scarcity for a prolonged period of time. If the situation doesn’t improve, 700 million people worldwide could be displaced by intense water scarcity by 2030. Africa, in particular, is facing severe water scarcity and the situation is worsening day by day. Resolute and substantial action is needed to address the issue.

Water Scarcity in Africa: An Overview

Water scarcity is the condition where the demand for water exceeds supply and where available water resources are approaching or have exceeded sustainable limits.

The problem of water scarcity in Africa is not only a pressing one but it is also getting worse day by day. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) , water scarcity affects 1 in 3 people in the African Region and the situation is deteriorating because of factors such as population growth and urbanisation but also climate change.

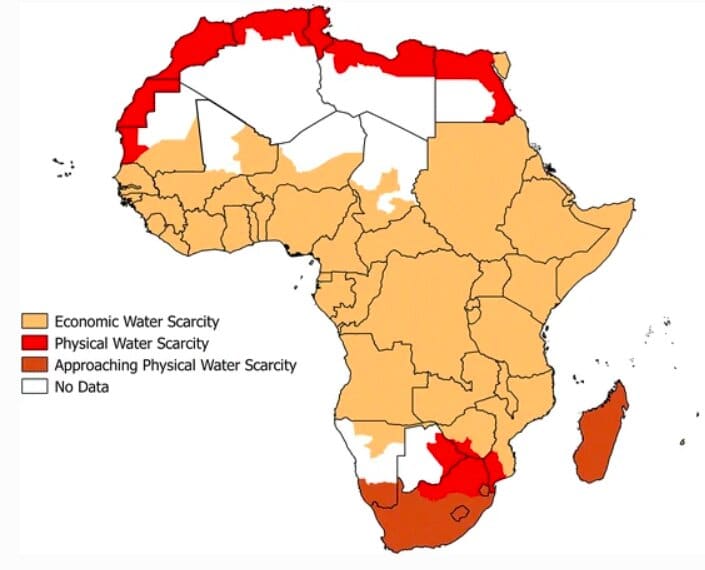

Water scarcity can be classified into two types: physical and economic. Physical water scarcity occurs when water resources are overexploited for different uses and no longer meet the needs of the population. In this case, there is not enough water available in physical terms. Economic water scarcity, on the other hand, is linked to poor governance, poor infrastructure, and limited investments. The latter type of water scarcity can exist even in countries or areas where water resources and infrastructure are adequate.

As reported by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa in 2011, arid regions of the continent – mainly located in North Africa – experience frequent physical water scarcity, while Sub-Saharan Africa undergoes mainly economic water scarcity. Indeed, the latter region has a decent levels of physical water , mainly thanks to the abundant, though highly seasonal and unevenly distributed supply of rainwater. This region’s access to water, however, is constrained due to poor infrastructure, resulting in mainly economic rather than physical water scarcity.

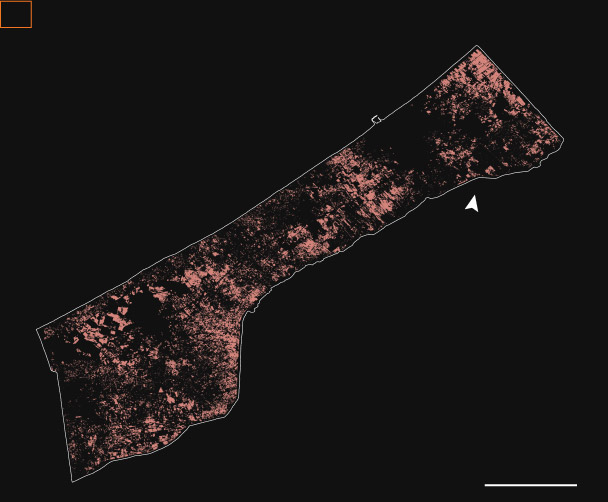

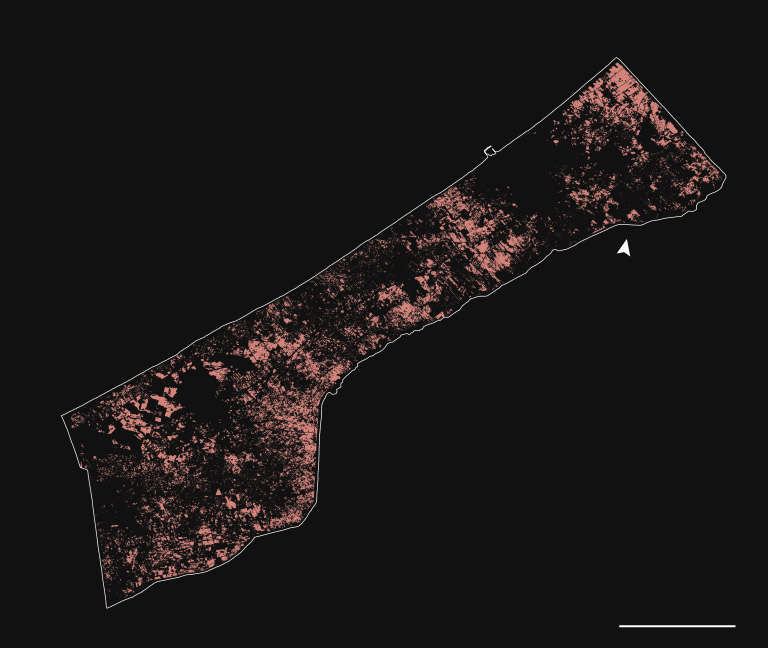

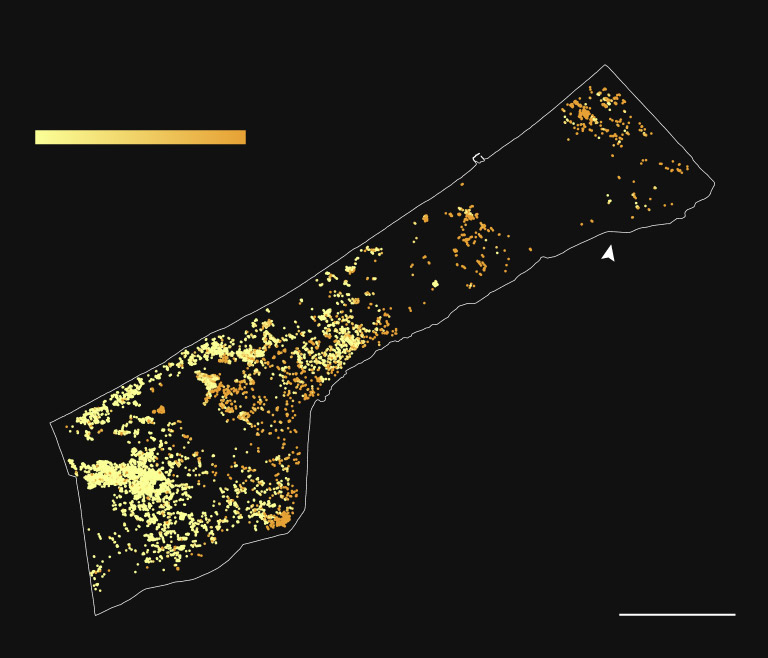

Figure 1: Map of physical and economic water scarcity at basin level in 2007 across the African continent.

You might also like: Countries With Water Scarcity Right Now

In a 2022 study conducted on behalf of the United Nations University Institute for Water Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH), researchers employed indicators to quantify water security in all of Africa’s countries. They found that only 13 out of 54 countries reached a modest level of water security in recent years, with Egypt, Botswana, Gabon, Mauritius and Tunisia representing the better-off countries in Africa in terms of water security.

19 countries – which are home to half a billion people – are deemed to have levels of water security below the threshold of 45 on a scale of 1 to 100. On the other hand, Somalia, Chad, and Niger are the continent’s least water-secure countries.

Egypt performs the best regarding access to drinking water while the Central African Republic performs the worst. The latter, however, has the highest per capita water availability while half of North African countries are characterised by absolute water scarcity. This again shows that Sub-Saharan Africa and Central Africa face economic water scarcity more than physical water scarcity.

Causes of Water Scarcity in Africa

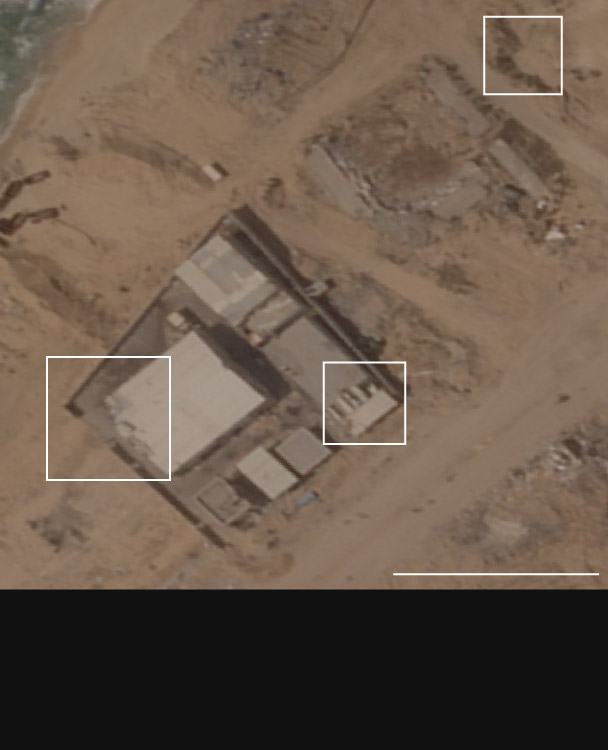

Human activities, which result in overexploitation and global warming, are the main culprit for the water scarcity in Africa. Overexploitation is the main contributor to physical water scarcity. A 2018 report published by the Institute for Security Studies stated that more than 60% of South Africa’s rivers are being overexploited and only one-third of the country’s main rivers are in good condition. Lake Chad – once deemed Africa’s largest freshwater body and important freshwater reservoir – is shrinking because of overexploitation of its water. According to a 2019 report , for this reason alone, the water body of the lake has diminished by 90% since the 1960s, with the surface area of the lake decreasing from 26,000 square kilometres in 1963 to less than 1,500 square kilometres in 2018.

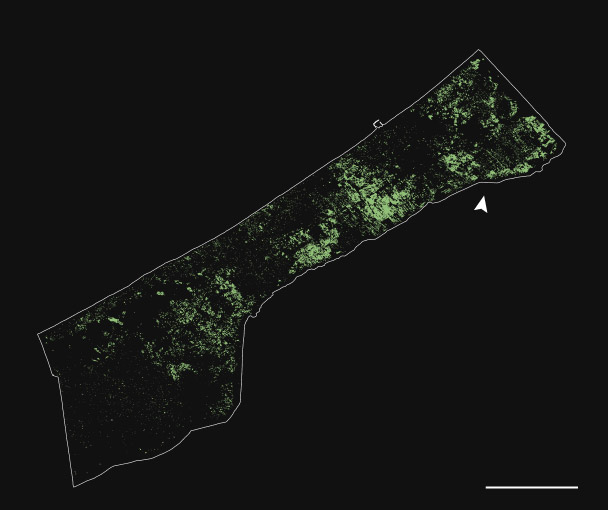

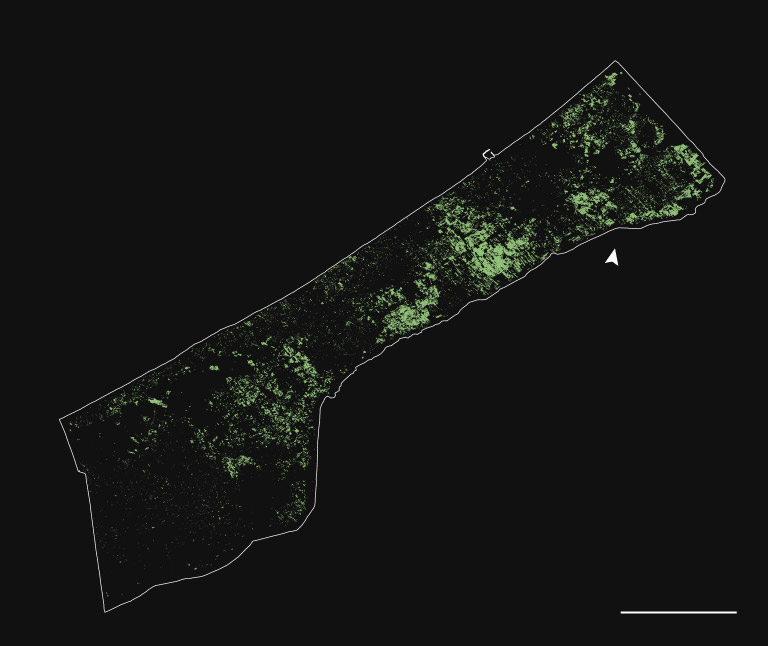

Figure 2: The size of Lake Chad shows a massive shrinking between 1972 and 2007.

The underlying cause for overexploitation can be further broken down to the increase in water demand, driven by the rise in population growth and rate of urbanisation.

Population in Sub-Saharan Africa is growing at a rate of 2.7% a year in 2020, more than twice that of South Asia (1.2%) and Latin America (0.9%). Meanwhile, the population of Nigeria – a country in West Africa – is forecasted to double by 2050. As for the rate of urbanisation, according to the United Nations , 21 out of the 30 fastest-growing cities in the world in 2018 are deemed to be in Africa. Cities such as Bamako in Mali and Yaounde in Cameroon have experience explosive growth.

The booming population will inevitably lead to more food demand, a faster rate of urbanisation and an rise in industrial activities, all of which require abundant water supply.

Climate change and global warming – mainly caused by an increase in human and commercial activities – equally contribute to water scarcity in Africa. As a report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa found, a 1C rise in global temperatures would result in a reduction of runoff – excess rainwater that flows across the land’s surface – by up to 10%. Another study stated that the declining trends of rainfall caused by global warming will continue in North Africa, limiting groundwater recharge and exacerbating groundwater depletion. Although in areas closer to the equator, a soar in precipitation will likely occur as a result of global warming, the increased potential evapotranspiration – the combined loss of water through the plant’s process of transpiration and evaporation of water from the earth’s surface – and drought risks in the majority of the continent still outweigh the increased rainfall in these areas.

Consequences of Water Scarcity in Africa

Water scarcity is expected to affect the economic condition, the health of citizens as well as ecosystems in Africa.

In economic terms, the agriculture sector is likely to be hampered under severe water scarcity. Agriculture is one of the most pivotal economic sectors for Africa, employing the majority of the population. In Sub-Saharan Africa alone, it accounts for nearly 14% of the total Gross Domestic Product (GDP). As the sector that relies on water the most, agriculture is already heavily impacted by water scarcity and the situation is expected to further deteriorate, leading to other issues such as food shortages and, in the worst cases, famine.

You might also like: Why We Should Care About Food Security

Not surprisingly, water shortage is an immense threat to human’s health. In times of water scarcity, people are often forced to get their water supply from contaminated ponds and streams. When ingested, polluted water results in widespread diarrhoeal diseases including cholera, typhoid fever, salmonellosis, other gastrointestinal viruses, and dysentery. Quality of healthcare services in many African countries is low, with only 48% African people having access to healthcare. The poor system has made diarrhoeal diseases life-threatening and in many cases even fatal.

A study published in 2021 found that severe diarrheal disease accounts for about 600,000 deaths each year in sub-Saharan Africa, with the majority being children and elderly. Diarrheal disease is the third-leading cause of disease and death among African children under the age of five, a situation that public health authorities blame on poor quality of water and sanitation.

Lastly, water shortages jeopardise ecosystems and contribute to a loss in biodiversity. Africa is home to some of the most unique freshwater ecosystems in the world. Lake Turkana is the world’s largest desert lake, while Lake Malawi hosts the richest freshwater fish fauna in the world, home to a staggering 14% of the world’s freshwater fish species. If not tackled, water scarcity will disrupt and likely terminate freshwater and marine ecosystems in the continent.

You might also like: 10 of the Most Endangered Species in Africa

Solutions to Water Scarcity in Africa

Remedies for water scarcity are observed on a local, national, and international scale.

Local communities are taking adaptation action. Many opt for drought-tolerant crops instead of crops that require large amounts of water, a strategy to mitigate both water scarcity and food insecurity. Conservation or regenerative agriculture is also introduced to help infiltration and soil moisture retention through mulching and no-tillage approaches. Countries such as Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Ethiopia have all adopted such techniques in recent years.

Several governments are also taking steps to tackle water scarcity across the continent. For example, the government of Namibia financed the construction of a urban wastewater management in the capital Windhoek, significantly improving the management of water resources and thus lowering the risk of water scarcity.

International organisations also lend a helping hand in times of water scarcity. In recent years, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) promoted several initiatives and implemented innovative financing model to alleviate this pressing issue. In regions in eastern and southern Africa, UNICEF is cooperating with the European Investment Bank (EIB), the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) and other international agencies and organisations to evaluate and implement bankable projects in a blended financing mode, particularly targeting the urban areas. For example , the European Union donated €19 million for the construction of water supply systems in the Eswatini’s cities of Siphofaneni, Somntongo, and Matsanjeni. Similarly, the DBSA contributed about €150 million to the construction of the Lomahasha Water Supply. Booster pumping stations as well as reinforced concrete reservoirs are also constructed with the support of international actors.

You might also like: One Woman’s Mission to Fight Water Scarcity in Africa

All in all, the water scarcity problem in Africa is likely to exacerbate under the ever-increasing water demand and rise in global temperatures. Tangible action from all parties is constantly required to tackle this massive problem. Individuals can equally play an important role in alleviating water scarcity in Africa by adopting a more environmental-friendly lifestyle and taking actions in their daily lives to mitigate the effect of climate change and they can develop mindful practises that help safe water, one of the most important resources for life on Earth.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us

About the Author

Charlie Lai

15 Biggest Environmental Problems of 2024

International Day of Forests: 10 Deforestation Facts You Should Know About

Water Shortage: Causes and Effects

Hand-picked stories weekly or monthly. We promise, no spam!

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Boost this article By donating us $100, $50 or subscribe to Boosting $10/month – we can get this article and others in front of tens of thousands of specially targeted readers. This targeted Boosting – helps us to reach wider audiences – aiming to convince the unconvinced, to inform the uninformed, to enlighten the dogmatic.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2021

Evaluating the economic impact of water scarcity in a changing world

- Flannery Dolan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8916-3903 1 ,

- Jonathan Lamontagne ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3976-1678 1 ,

- Robert Link 2 ,

- Mohamad Hejazi 3 , 4 ,

- Patrick Reed ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7963-6102 5 &

- Jae Edmonds ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3210-9209 3

Nature Communications volume 12 , Article number: 1915 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

70k Accesses

176 Citations

181 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Climate and Earth system modelling

- Environmental economics

Water scarcity is dynamic and complex, emerging from the combined influences of climate change, basin-level water resources, and managed systems’ adaptive capacities. Beyond geophysical stressors and responses, it is critical to also consider how multi-sector, multi-scale economic teleconnections mitigate or exacerbate water shortages. Here, we contribute a global-to-basin-scale exploratory analysis of potential water scarcity impacts by linking a global human-Earth system model, a global hydrologic model, and a metric for the loss of economic surplus due to resource shortages. We find that, dependent on scenario assumptions, major hydrologic basins can experience strongly positive or strongly negative economic impacts due to global trade dynamics and market adaptations to regional scarcity. In many cases, market adaptation profoundly magnifies economic uncertainty relative to hydrologic uncertainty. Our analysis finds that impactful scenarios are often combinations of standard scenarios, showcasing that planners cannot presume drivers of uncertainty in complex adaptive systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

The economic commitment of climate change

The carbon dioxide removal gap

Frequent disturbances enhanced the resilience of past human populations

Introduction.

Global water scarcity is a leading challenge for continued human development and achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals 1 , 2 . While water scarcity is often understood as a local river basin problem, its drivers are often global in nature 3 . For instance, agricultural commodities (the primary source of global water consumption 4 ), are often traded and consumed outside the regions they are produced 5 . These economic trade connections mean that global changes in consumption result in impacts on local water systems 6 . Likewise, local water system shocks can also propagate globally 7 , 8 . Water is a critical input to other sectors, such as energy, transportation, and manufacturing 9 , 10 , so that changes in the regional water supply or sectoral demand can propagate across sectors and scales. Continued population growth, climate change, and globalization ensure that these multi-region, multi-sector dynamics will become increasingly important to our understanding of water scarcity drivers and impacts 11 .

Quantifying water scarcity and its impacts are active and growing research areas 12 . Early and influential work in the area largely focused on supply-oriented metrics of scarcity: per-capita water availability 13 , the fraction of available water being used 14 , and more sophisticated measures that account for a region’s ability to leverage available water given its infrastructure and institutional constraints 15 . Recent work proposes indicators such as water quality 16 , green water availability 17 , and environmental flow requirements 18 that focus on specific facets of water scarcity. Qin et al. incorporate the flexibility of current modes of consumption to identify regions where adaptation to scarcity may be relatively difficult 19 . Other recent work focuses on the water footprint of economic activity 20 , 21 making it possible to identify the economic drivers of scarcity (through virtual water trade) 6 , 8 . Yet knowledge gaps remain concerning how the economic costs of future water scarcity will propagate between sectors and regions as society adapts to scarcity, and how the cost of this adaptation depends on uncertainties in the projections of future conditions.

From the economic perspective, water scarcity impacts arise when the difficulty of obtaining water forces a change in consumption. For instance, abundant snowmelt may be of little use to would-be farmers if barriers (cost, institutional, etc.) prevent them from utilizing it. They will be forced to go elsewhere for water or engage in other activities, and this bears an economic cost that is not reflected in conventional water scarcity metrics. When water becomes a binding constraint, societies adapt through trade and shifting patterns of production, and the cost of that adaptation is tied to the difficulty of adopting needed changes. Changing annual cropping patterns to conserve water is easier and will impact an economy less than shuttering thermal power generation during prolonged drought 19 . In a globalized economy, the impact of such adaptation cannot be assessed in a single basin or sector in isolation, as hydrologic changes in one region reverberate across sectors around the world 3 , 22 . Indeed, reductions in water supply in one region may increase demands for water in another, simultaneously inducing both physical scarcity and economic benefit in ways that are difficult to anticipate ex ante 23 . Our primary research question is how these dynamics will impact society in the future, and how both the magnitude and direction of those impacts depend on future deeply uncertain conditions 24 .

To address this question, we deploy a coupled global hydrologic-economic model with basin-level hydrologic and economic resolution 25 to compute the loss (or gain) of economic surplus due to that scarcity in each basin across a range of deeply uncertain futures. Here “economic surplus” refers to the difference between the value that consumers place on a good and the producers’ cost of providing that good 26 . The surplus is a measure of the value-added, or societal welfare gained, due to some economic activity. The change in economic surplus is an appealing metric because it captures how the impact of resource scarcity propagates across sectors and regions that depend on that resource. Change in surplus has been used in past studies to assess the impacts of water policies and to understand how to efficiently allocate water in arid regions 27 , 28 , though it has not typically been used to analyze the impact of water scarcity itself. One exception is a study by Berritella et al., who used the loss in equivalent variation, another welfare metric, to measure the effects of restricting the use of groundwater 29 . On a broader scale, our analysis tracks the impacts of scarcity in hundreds of basins across thousands of scenarios, revealing important global drivers of local impacts that are often missed when the spatial and sectoral scope is defined too narrowly.

Global water scarcity studies depend on long-term projections of climate, population growth, technology change, and other factors that are deeply uncertain, meaning that neither the appropriate distribution nor the correct systems model is agreed upon 24 , 30 . Complicating matters, the coupled human-earth system is complex, exhibiting nonlinearities and emergent properties that make it difficult to anticipate important drivers in the scenario selection process. In such a case, focusing on a few scenarios, as is common in water scarcity studies, risks missing key drivers and their interactions 31 . In contrast, recent studies advocate exploratory modeling 32 to identify important global change scenarios 33 , 34 . In that approach, the uncertainty space is searched broadly and coupled-systems models are used to test the implications of different assumptions on salient measures of impact across a scenario ensemble 35 . Exploratory modeling is especially important in long-term water scarcity studies, where we show that meaningful scenarios vary widely from basin-to-basin, highlighting the inadequacy of relying on a few global narrative scenarios.

By analyzing a large ensemble of global hydro-economic futures, we arrive at three key insights. First, basin-level water scarcity may be economically beneficial or detrimental depending on a basin’s future adaptive capacity and comparative advantage, but that advantage is highly path-dependent on which deeply uncertain factors emerge as the basin-specific drivers of consequential outcomes. For instance, in the Lower Colorado Basin, the worst economic outcomes arise from limited groundwater availability and high population growth, but that high population growth can also prove beneficial under some climatic scenarios. In contrast, the future economic outcomes in the Indus Basin depend largely on global land-use policies intended to disincentive land-use change in the developing world. Our second insight is that those land-use policies often incentivize unsustainable water consumption. In the case of the Indus Basin, limiting agricultural extensification results in intensification through increased irrigation that leads to unsustainable overdraft of groundwater, with similar dynamics playing out elsewhere. Third, our results show that the nonlinear nature of water demand can substantially amplify underlying climate uncertainty, so that small changes in runoff result in large swings in economic impact. This is pronounced in water-scarce basins (like the Colorado) under high-demand scenarios. Collectively, these insights suggest that understanding and accounting for the adaptive nature of global water demand is crucial for determining basin-level water scarcity’s path-dependent and deeply uncertain impacts.

Global-to-basin impacts

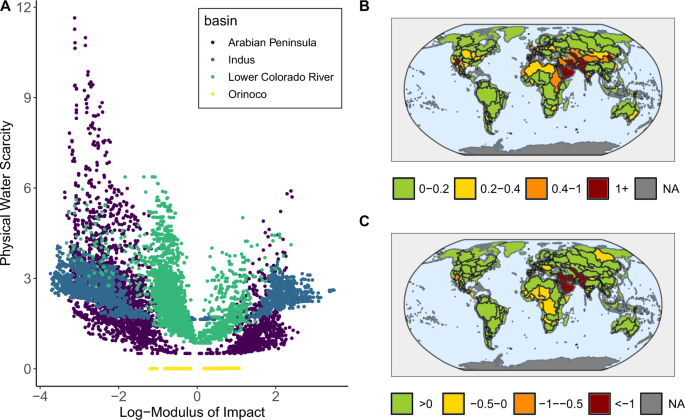

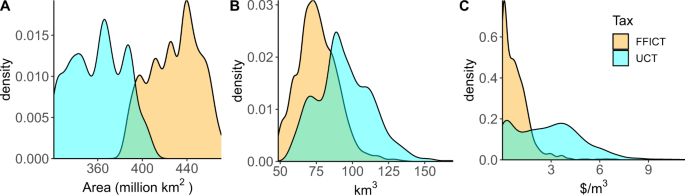

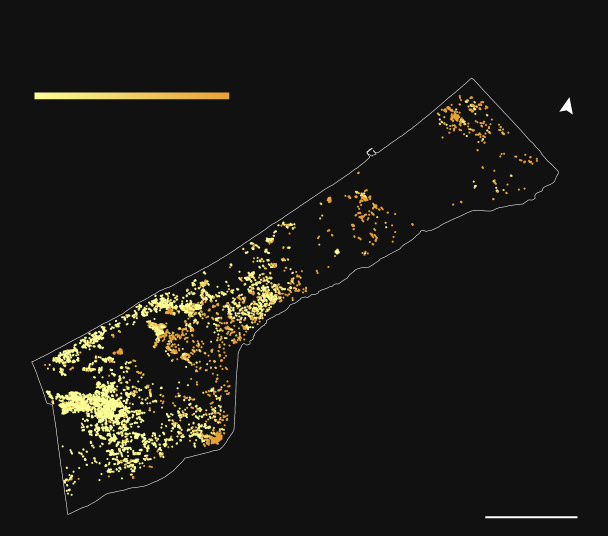

We calculate both physical water scarcity (Fig. 1B ) and its economic impact (Fig. 1C ) over the 21st century for 235 river basins for each of the 3000 global change scenarios, simulated using the Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM) integrated assessment model 36 . With the effects of inter-basin trade, hydrologic basins may experience highly positive or highly negative economic impact due to water scarcity (Fig. 1A ). Here, economic impact is defined as the difference in total surplus in water markets (Supplementary Fig. 1 ) between a control scenario with unlimited water and an experimental scenario with limited water supply (Supplementary Fig. 2 ). Water scarcity usually induces negative economic impact (loss of surplus), although positive economic impact from global water scarcity can arise if a basin holds a comparative advantage over others. With this comparative advantage, a basin can become a virtual water exporter through inter-basin trade 37 , meaning it will export water-embedded goods to other regions. Though some basins experience positive impact more often than others (across the scenario ensemble), all basins experience both negative and positive impacts in some scenarios (Supplementary Table 1 ): no basin has a universally positive or negative outlook. As may be expected, the basins with the highest number of positive impact scenarios are those that are relatively water-rich by conventional measures (Fig. 1B ), for example, the Orinoco River in northern South America (Fig. 1A ).

The scatter plot in panel A shows the two metrics in panels B and C plotted against each other in four basins. Each point represents the maximum absolute value of that metric over time in each scenario. The map in panel B shows WTA in each water basin while the map in panel C shows the log-modulus of economic impact. Both maps plot the maximum absolute value of the metric over time and the median across all scenarios. The correspondence between the two metrics is not perfect. Some water-scarce basins have more capacity to handle water scarcity and thus are not as impacted economically as others.

We measure physical water scarcity using the Withdrawal-To-Availability ratio (WTA) which is computed by dividing water withdrawals by renewable supply. The correspondence between the WTA and the economic impact metric is not perfect (Fig. 1B and C ). In some scenarios (for instance, those with restricted reservoir storage), basins with high physical scarcity have a small negative or even positive economic impact, and in others, basins with low physical scarcity have a negative economic impact (Fig. 1A ). This highlights the importance of capturing the interdependencies between physical and economic factors that affect the welfare of a basin.

Several basins show high variance in economic impacts, including the Indus River Basin, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Lower Colorado River Basin (Supplementary Fig. 4 ). In addition to variance in economic impacts, those basins exhibit a wide range of physical water scarcity, are geographically diverse and are of geopolitical importance. The Orinoco Basin is also highlighted as an example of a basin that is not physically water-scarce and experiences slightly positive economic impact in most scenarios (Fig. 1A and B ). Such water-rich basins are particularly well-positioned to produce more water-intensive products to offset lost production in water-scarce basins (Supplementary Fig. 3 ), though the stylized water markets as represented in GCAM (and indeed in all other global hydro-economic models) may overstate these benefits for some basins compared to real-world conditions. The market representation assumes that all agents have an equal opportunity to acquire water and that water is allocated in the most economically efficient manner (except for agricultural subsidies 38 ). In reality, water rights frameworks and barriers to trade may block potential users from putting the water to more economically beneficial use.

The distributions of the plotted scenarios in the four selected basins (Fig. 1A ) give some indication of the relationship between water scarcity and economic impact in each basin. The bi-modal spread of the scenario points (Fig. 1A ) shows that higher physical water scarcity can be associated with both highly positive and severely negative economic impacts. When the distributions are wide and shallow (e.g., the Indus Basin in Fig. 1A ), smaller changes in physical scarcity lead to much higher changes in economic impact compared with other basins (Table 1 ). This occurs if the basin cannot easily supplement renewable supply with other water sources and the price of water rises precipitously. Shifts in demand subject to these high prices lead to large swings in economic impact.

The direction of shifts in demand depends on a basin’s comparative advantage (or disadvantage) due to the scenario assumptions and how these assumptions affect other basins around the world. As evidenced by the positive scenarios in water-scarce basins in Fig. 1 , this comparative advantage can arise from mechanisms other than abundant water supply (e.g., higher agricultural productivity, different dietary or technological preferences, or a lower population). The equilibrium demand over the renewable supply (the WTA) could be the same in two scenarios with very different economic impacts depending on if the scenario assumptions enable a basin’s comparative advantage in one but are detrimental in another (Fig. 1A ). Influential factors that determine economic impact are basin-specific (examples given in the next section). The changes in demand and resulting impacts due to these factors underscore the importance of projecting basin-level scarcity in a global context that allows for market adaptation.

Climate system uncertainty amplification

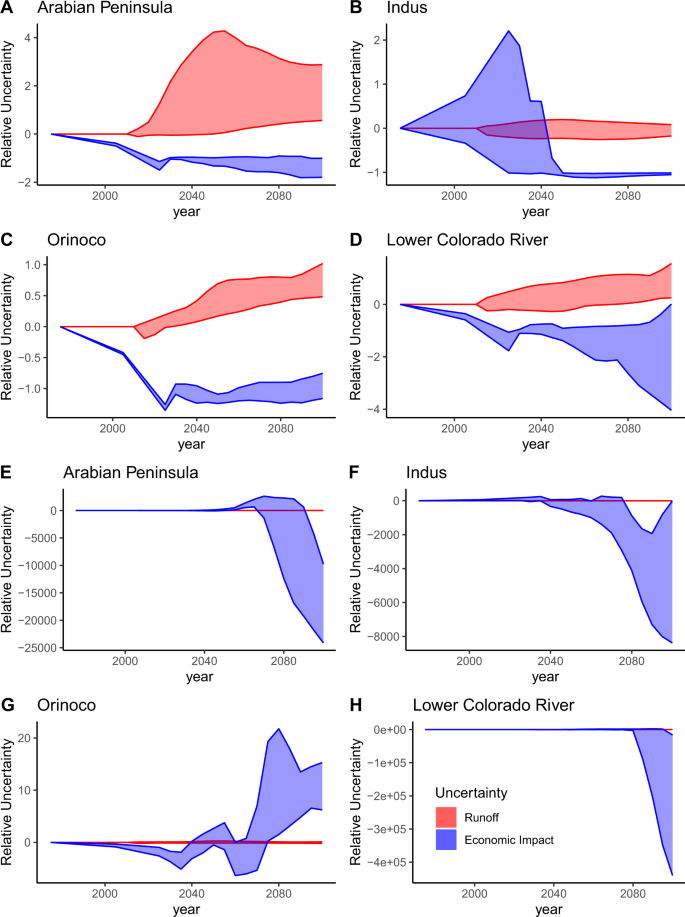

The market response to water scarcity within a hydrologic basin usually amplifies the uncertainty in hydro-climatic projections (Fig. 2 , Supplementary Fig. 5 ), leading to higher changes in economic impact. Analysis of the scenario ensemble revealed that differences in Earth System Model (ESM) forcing often determines the sign of impact (SA Figs. 6 – 9 ). The ESMs contribute precipitation and temperature projections to the hydrologic model used by GCAM, generating water runoff estimates (see “Methods” section). Surface water supply fluctuations heavily affect changes in economic surplus within these hydrologic basins. Other important factors include reservoir expansion (in Arabia and the Orinoco), land-use scenario (in the Indus and Orinoco), and agricultural productivity (in Arabia, the Indus, and the Orinoco) (Supplementary Figs. 6 – 9 ).

Uncertainty over time plots of the four chosen basins. Values are taken relative to the 2015 baseline. Uncertainty prior to 2015 is illustrative only. The scenario group shown in A – D has the lowest mean climate-induced economic impact uncertainty over time out of the 600 groups. The scenario group shown in E – H has the highest mean climate-induced economic impact uncertainty over time. In most scenarios, runoff uncertainty is amplified by the human system, leading to higher uncertainty in economic impact.

Climate uncertainty is one dimension over which decision-makers have very little control (as opposed to socioeconomic trajectories, agricultural advancements, reservoir storage, etc.). To isolate the uncertainty in the economic impact due to this fundamental climate uncertainty, 600 groups of five scenarios were created by holding all factors constant, except the ESM (of which 5 were considered). The difference between the maximum impact in this group of five and the minimum is one measure of climate-induced impact uncertainty. This uncertainty is plotted in blue in Fig. 2 compared to the runoff uncertainty in red. We find that the economic impact uncertainty is usually higher than the runoff uncertainty (Supplementary Fig. 5 ). Here, runoff uncertainty is the difference between the maximum runoff and the minimum runoff in the set of five scenarios. Peaks and troughs in Fig. 2 correspond to slight deviations in climate forcing in the ESMs. This in turn leads to differences in the runoff, which changes the unit costs of water, causing market adaptations and thus amplifying the economic surplus change (Supplementary Fig. 10 ).

High economic impact uncertainty relative to runoff uncertainty indicates that the market is very sensitive to changes in water supply. In high-demand scenarios (e.g., those with a high population and high food demand), the price of water steeply rises when shifting toward nontraditional water sources such as non-renewable reserves and desalination (Supplementary Fig. 11A ). When this occurs, deviations in supply lead to highly nonlinear impacts (Fig. 2E–H ). Vulnerable basins in these high-demand scenarios see steep and rapid declines in economic impact (Fig. 2E, H ). Scenarios where the economic impact continues dropping through the end of the century are of particular concern and suggest that a basin no longer has the economic capacity to stabilize these negative impacts. We will henceforth call this loss in capacity an ‘economic tipping point’.

Importantly, the conditions that lead to tipping points can vary substantially across basins. For instance, in the Arabian Peninsula, tipping point conditions include low groundwater availability and pricing carbon emissions from all sectors (see “Methods” section). Even with ample groundwater supply, tipping points can occur with high population and low GDP (SSP 3 socioeconomic assumptions) in addition to pricing carbon emissions from all sectors. In some scenarios, we can see that the Arabian Peninsula experiences a positive impact mid-century by relying on relatively inexpensive water resources. After these resources run out subject to the constraints, the economic impact becomes more negative until the end of the century (Fig. 2A ) and the basin utilizes an increasing amount of desalinated water (Supplementary Fig. 11B ). The lack of perfect foresight within GCAM helps explain this short-term thinking, though historically the area has withdrawn groundwater at unsustainable rates 39 .

Meanwhile, the Lower Colorado River Basin experiences an economic tipping point when there is low groundwater availability, low agricultural productivity (SSP 3 agriculture and land use assumptions), and high wealth socioeconomic trajectories (SSP 5 socioeconomics). The uncertainty in economic impact in the Lower Colorado Basin is the highest out of all of the highlighted basins (Fig. 2C ) and is one of the basins with the highest uncertainty in economic impact in the world.

Importantly, the factors that cause economic tipping points in these basins are not the same, nor do they always follow a well-defined global narrative such as the canonical SSPs. Table 2 shows the basins with the most highly negative impact values out of all the time periods in every scenario. Most of these scenarios contain a mixture of SSP elements (e.g., SSP 5 socioeconomics and SSP 4 agriculture in the Sabarmati). There are noticeable trends in the factors, for instance, high wealth socioeconomic trajectories (SSP 5) and the Universal Carbon Tax often lead to tipping points. However, the factors are not all the same in each basin (e.g., in the Ganges-Brahmaputra).

Mitigation-scarcity trade-offs

Pricing carbon emissions from the land-use sector often contributes to an economic tipping point because basins respond by intensifying agricultural land and increasing irrigation, thus exacerbating scarcity. When food demand increases, GCAM responds either by expanding agricultural land or intensifying existing agricultural land. With no price put on land-use change emissions (under the Fossil Fuel and Industrial Carbon Tax, or FFICT) it is more cost-effective to expand. Indeed, we find that scenarios with the FFICT use more agricultural land than the Universal Carbon Tax (UCT) scenarios (Fig. 3A ). Conversely, the carbon prices under the UCT disincentivize expansion and therefore prompt intensification. Carbon prices are derived from the continued ambition scenario of the Nationally Determined Contributions in a future with medium challenges to adaptation and mitigation 40 (see “Methods” section).

Density plots depicting the difference in tax regimes. The plot in A depicts the sum of global cropland over time under the two carbon tax regimes. The density plot in B shows water withdrawals in the Arabian Peninsula in FFICT (orange) and UCT (cyan) scenarios. The density plot in C depicts the shadow price of water in the Indus River basin in the two tax cases. Values in B and C are averaged over time. Total agricultural land increases under the FFICT while water price and water withdrawals increase under the UCT.

When intensification occurs, yields are increased by irrigating crops more instead of relying on rainwater. The intensity of agricultural land management also increases. These changes prompt greater water withdrawals (Fig. 3B ). The shift from rainwater toward irrigated water also increases the price of water in the UCT scenarios (Fig. 3C ). These results are especially significant in basins sensitive to land-use change. A previous study found that the FFICT prompts greater water withdrawals 41 . However, the study used a previous version of GCAM that did not have intensification options and assumed unlimited water. In that version, water use was proportional to land use. Therefore, when the UCT disincentivized expansion, water use was also limited. When extensification-intensification dynamics are considered, we find a substitution between water use and agricultural expansion. This finding emphasizes the importance of considering all trade-offs in mitigation policy options.

In this study, we use an economic surplus metric in order to quantify the economic impacts of water scarcity and the uncertainty of this impact due to different factors (i.e., population, agricultural productivity, etc.). Theoretically, basins would withdraw less when exposed to a limited supply of water and thus experience a negative economic impact, yet we find some basins capitalize on their water resources and become virtual water exporters in the face of global water scarcity. This dynamic would not be captured by looking at physical water scarcity metrics alone, nor by assessing economic impact at the basin-scale.

These variable responses to water scarcity are sometimes due to highly uncertain and largely uncontrollable factors such as the climate system. When normalized by a 2015 baseline, we find that uncertainty of economic impact due to Earth System Model forcing alone is often several thousand times higher than the uncertainty in the forcing itself (Fig. 2 ). Across the sampled states of the world, we find that slight deviations in precipitation drivers are almost always amplified as they propagate through markets. Since we have little control over uncertainty in the climate system, basin economies that are sensitive to fluctuations in hydro-climactic forcings will need especially robust water resource management frameworks in the future. Further, basins with the highest amount of impact variability due to climate uncertainty are often in politically unstable regions such as the Middle East. Thus, there is an even greater need to manage water resources in the most efficient way possible in the face of extreme uncertainty of economic impacts due to climate in these basins. Planners must also be aware of factors (e.g., population growth or carbon pricing regimes) that lead to economic tipping points in unstable basins.

Under the assumption that food production will always meet demand, implementing a Universal Carbon Tax prompts the intensification of agricultural land due to the increased cost of converting land for agricultural use. The intensification is enabled by increased irrigation and greater water withdrawals (Fig. 3 ). Thus, the effects of pricing carbon in a land-use policy on land intensification-extensification dynamics need to be taken into account in basins exhibiting high levels of water stress.

We find that most scenarios of interest (i.e., those that resulted in extremely high or low economic impact) are composed of a mix of SSP dimensions. This demonstrates the importance of using a scenario discovery framework in the context of a highly uncertain problem such as modeling water resources and the drawbacks of focusing on a limited set of narratives. In addition, the dimensions of high importance in certain basins are of less importance in others. Indeed, every dimension varied in this study was the most influential factor in determining the economic impact of water scarcity in at least one basin (Supplementary Fig. 12 ). Scenario discovery addresses this by identifying the most critical scenario components to the specific analysis context. There is no reason to expect universal shared scenarios will capture key challenges in each basin (or indeed in any), and it is very difficult to anticipate what combinations of factors present challenges in every basin before doing extensive exploration. Scenario discovery is a promising approach to identify relevant scenarios to inform water scarcity analyses. In addition, while this work assessed the economic impact in water markets alone, future work could make use of a Computable General Equilibrium model where the interactions between all markets would be accounted for (see “Methods” section). Indeed, we hope this work provides the basis for similar analyses across a range of hydro-economic models to ascertain the sensitivity of our results to model structure. Confidence in our metric depends on the fidelity of the selected hydro-economic model, so future work would benefit from expanded data collection of socio-technological drivers of regional and sectoral water consumption to improve those underlying models. This study’s use of a coupled partial equilibrium-hydrologic model to perform an extensive uncertainty analysis is novel to the integrated assessment modeling literature and enables the discovery of important multi-scale dynamics such as a basin’s wide range of adaptive responses to water scarcity.

Human-earth system model

Multiple factors affect water demand including population, wealth abundance and distribution, agricultural technology and practices, technological improvements, and carbon and land-use policy. These factors all interact with each other and with the climate system. It is therefore necessary to use a model that includes detailed representations of these systems and the interdependent endogenous choices that shape them. To this end, we have used a partial equilibrium model in order to represent the affected systems with as much detail as possible.

This study makes use of the Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM), a human-Earth system model that has been used by numerous agencies to make informed policy decisions 36 . GCAM is a complex model that decomposes the world into 32 geopolitical regions, 384 land-use regions, and 235 water basins 36 . GCAM includes coupled representations of the Earth’s climate, economic, hydrologic, land-use, and energy systems. These systems are expressed in varying degrees of detail. Population and GDP growth are represented as simple exogenous model inputs. Energy and land-use systems are represented in more detail, with shares of supplies and technologies competing using a logit model 36 . Renewable technologies within the model become more efficient over time and therefore some processes such as solar energy production become more competitive. Nonrenewable resources such as oil and fossil groundwater are modeled with graded supply curves and become more expensive as the levels are used up over time. Shares of energy production technologies may change based on different policy choices. For example, a carbon tax may increase the feasibility of using renewable energy sources. These policies may also impact the shares of land uses (e.g., the carbon tax may prompt afforestation).

Water demand and supply

GCAM allows users to specify water constraints and to link water supply to Xanthos, an extensible hydrologic model 42 . Previous versions of GCAM have introduced the water system but have limited its capabilities to computing water demands. The current system calculates both supply and demand and balances the two quantities by solving for an equilibrium regional shadow price for water 38 , 43 , 44 . Water demand in GCAM is modeled through six sectors: irrigation, livestock, municipal, manufacturing, primary energy, and electricity generation 25 . Irrigation demand is based on biophysical water demand estimates for twelve crop classes 25 . Water demand for irrigation is determined by deducting green water (i.e., water available for use by plants) on irrigated areas and green water on rain-fed areas from total water consumption. Livestock water demand is computed using the consumptive rates for six livestock types (cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, pigs, and poultry) and estimates of livestock density in 2000 25 . Water withdrawals for electricity generation are related to the amount of electricity generated in each region. Once-through cooling systems compete with evaporative cooling systems with the latter becoming more prevalent over time 25 . Water use in the primary energy sector (i.e., the water used to extract natural resources) is calculated using estimates of energy production in each region along with water use coefficients. Municipal water demand is modeled using population, GDP, and assumptions about technological efficiencies 36 , 41 . Finally, manufacturing water demand is the total industrial water withdrawals less the energy-sector water withdrawals 25 . Consumption is calculated using exogenous consumption to withdrawal ratios for industrial manufacturing 25 .

Water supply in GCAM is modeled using three sources: surface water and renewable groundwater, nonrenewable groundwater, and desalinated seawater. Similar to technology use within GCAM, these sources of water compete using a logit structure based on price. Surface water is typically used first in larger quantities than its competing sources as it is the cheapest source of water. The upper limit of surface water in a basin is taken to be the mean average flow modeled using Xanthos, which calculates water supply at a monthly time step using evapotranspiration, water balance, and routing modules 42 . Accessible water 38 is assumed to be the volume of runoff available even in dry years in addition to reservoir storage capacity (after removing environmental flow requirements). The estimates of accessible water and basin runoff are used as inputs in GCAM. After the renewable water supply is fully consumed, GCAM will either use desalinated water or nonrenewable groundwater depending on the relative shares computed in the price-based logit structure 38 . Nonrenewable groundwater increases in price as more of the resource is consumed. The groundwater supply curves account for geophysical characteristics such as aquifer thickness and porosity, as well as economic factors such as the cost of installing and operating the well. As the price of extraction rises, desalination becomes more competitive, resulting in wider use of desalinated water 44 .

Basin-specific water policies are not represented within GCAM or indeed any global model. The level of detail needed to represent existing water markets and policies exceeds the capabilities of a global model. GCAM does, however, enforce a subsidy on water for agricultural sectors 36 . Imposing this subsidy in GCAM’s water markets allows water to be allocated first to agricultural producers. This behavior mimics the effect of traditional water rights in that senior rights are usually given to agricultural producers. The water markets within GCAM operate by generating a “shadow” price of water, which reflects the economic value of the last unit of water in terms of the water’s contribution to production. When water supply becomes a binding constraint in a particular water basin, the shadow price of water rises because users cannot use more water than there is in the basin. This forces a reduction in the production of the goods and services that rely on water as an input. Clearly, this approach is a simplification, but it marks an improvement over what is most often done where the implications of water scarcity are ignored (i.e., direct and indirect feedbacks associated with unsatisfied water demands are not captured, and analyses are limited to how water scarcity may increase or decrease in the future without a mechanism for dynamic adaptation measures).

We compute the difference in total economic surplus in these simplified water markets (i.e., the sum of producer surplus and consumer surplus) between a control scenario with no water constraints and its paired limited water scenario (see next section).

Capturing economic impact in the entire economy would require a general equilibrium model. However, general equilibrium models necessarily lose some detail in sectoral resolution so that they can capture market interactions. Water is a non-substitutable input to most markets in the human system and so most market interactions will be represented by the changes in water markets when conditions are perturbed. The surplus change in the water markets includes both direct effects (e.g., restricted supply) and indirect effects (e.g., demand shifts in adjacent markets). There may be economic effects not captured by looking at water markets alone, which could be investigated in future work that employs a computable general equilibrium model. Numerous previous studies have assessed economic impact in water markets using both types of models 45 .

Scenario design

We utilize a scenario discovery approach 35 to study the uncertainty in physical water scarcity and its economic impacts. Using this approach, scenarios are generated using all possible combinations of discrete levels of uncertain factors. All scenarios are weighted equally during scenario exploration so as not to presume the likelihood of outcomes a priori. Doing so may leave the system vulnerable to unanticipated events. In addition, in complex adaptive systems such as the human-Earth system, the main drivers of an outcome of interest may be non-intuitive and context-specific 34 . The traditional “predict-then-act” approaches 46 to planning implies a more complete understanding of the system and of future circumstances than is often the case, which can, in turn, lead to myopic decisions 35 . Alternatively, scenario discovery gives equal weight to all possible future system trajectories (i.e., population, wealth, energy prices) and finds the most influential factors driving outcomes of interest-based on the results of all scenarios. Planners can then make robust management decisions based on the influential factors and their uncertainties as opposed to designing based on a few future projections.