- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

A Guide to Rebuttals in Argumentative Essays

4-minute read

- 27th May 2023

Rebuttals are an essential part of a strong argument. But what are they, exactly, and how can you use them effectively? Read on to find out.

What Is a Rebuttal?

When writing an argumentative essay , there’s always an opposing point of view. You can’t present an argument without the possibility of someone disagreeing.

Sure, you could just focus on your argument and ignore the other perspective, but that weakens your essay. Coming up with possible alternative points of view, or counterarguments, and being prepared to address them, gives you an edge. A rebuttal is your response to these opposing viewpoints.

How Do Rebuttals Work?

With a rebuttal, you can take the fighting power away from any opposition to your idea before they have a chance to attack. For a rebuttal to work, it needs to follow the same formula as the other key points in your essay: it should be researched, developed, and presented with evidence.

Rebuttals in Action

Suppose you’re writing an essay arguing that strawberries are the best fruit. A potential counterargument could be that strawberries don’t work as well in baked goods as other berries do, as they can get soggy and lose some of their flavor. Your rebuttal would state this point and then explain why it’s not valid:

Read on for a few simple steps to formulating an effective rebuttal.

Step 1. Come up with a Counterargument

A strong rebuttal is only possible when there’s a strong counterargument. You may be convinced of your idea but try to place yourself on the other side. Rather than addressing weak opposing views that are easy to fend off, try to come up with the strongest claims that could be made.

In your essay, explain the counterargument and agree with it. That’s right, agree with it – to an extent. State why there’s some truth to it and validate the concerns it presents.

Step 2. Point Out Its Flaws

Now that you’ve presented a counterargument, poke holes in it . To do so, analyze the argument carefully and notice if there are any biases or caveats that weaken it. Looking at the claim that strawberries don’t work well in baked goods, a weakness could be that this argument only applies when strawberries are baked in a pie.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Step 3. Present New Points

Once you reveal the counterargument’s weakness, present a new perspective, and provide supporting evidence to show that your argument is still the correct one. This means providing new points that the opposer may not have considered when presenting their claim.

Offering new ideas that weaken a counterargument makes you come off as authoritative and informed, which will make your readers more likely to agree with you.

Summary: Rebuttals

Rebuttals are essential when presenting an argument. Even if a counterargument is stronger than your point, you can construct an effective rebuttal that stands a chance against it.

We hope this guide helps you to structure and format your argumentative essay . And once you’ve finished writing, send a copy to our expert editors. We’ll ensure perfect grammar, spelling, punctuation, referencing, and more. Try it out for free today!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a rebuttal in an essay.

A rebuttal is a response to a counterargument. It presents the potential counterclaim, discusses why it could be valid, and then explains why the original argument is still correct.

How do you form an effective rebuttal?

To use rebuttals effectively, come up with a strong counterclaim and respectfully point out its weaknesses. Then present new ideas that fill those gaps and strengthen your point.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- How It Works

- Prices & Discounts

A Student's Guide: Crafting an Effective Rebuttal in Argumentative Essays

Table of contents

Picture this – you're in the middle of a heated debate with your classmate. You've spent minutes passionately laying out your argument, backing it up with well-researched facts and statistics, and you think you've got it in the bag. But then, your classmate fires back with a rebuttal that leaves you stumped, and you realize your argument wasn't as bulletproof as you thought.

This scenario could easily translate to the world of writing – specifically, to argumentative essays. Just as in a real-life debate, your arguments in an essay need to stand up to scrutiny, and that's where the concept of a rebuttal comes into play.

In this blog post, we will unpack the notion of a rebuttal in an argumentative essay, delve into its importance, and show you how to write one effectively. We will provide you with step-by-step guidance, illustrate with examples, and give you expert tips to enhance your essay writing skills. So, get ready to strengthen your arguments and make your essays more compelling than ever before!

Understanding the Concept of a Rebuttal

In the world of debates and argumentative essays, a rebuttal is your opportunity to counter an opposing argument. It's your chance to present evidence and reasoning that discredits the counter-argument, thereby strengthening your stance.

Let's simplify this with an example . Imagine you're writing an argumentative essay on why school uniforms should be mandatory. One common opposing argument could be that uniforms curb individuality. Your rebuttal to this could argue that uniforms do not stifle individuality but promote equality, and help reduce distractions, thus creating a better learning environment.

Understanding rebuttals and their structure is the first step towards integrating them into your argumentative essays effectively. This process will add depth to your argument and demonstrate your ability to consider different perspectives, making your essay robust and thought-provoking.

Let's get into the nitty-gritty of how to structure your rebuttals and make them as effective as possible in the following sections.

The Structural Anatomy of a Rebuttal: How It Fits into Your Argumentative Essay

The potency of an argumentative essay lies in its structure, and a rebuttal is an integral part of this structure. It ensures that your argument remains balanced and considers opposing viewpoints. So, how does a rebuttal fit into an argumentative essay? Where does it go?

In a traditional argumentative essay structure, the rebuttal generally follows your argument and precedes the conclusion. Here's a simple breakdown:

Introduction : The opening segment where you introduce the topic and your thesis statement.

Your Argument : The body of your essay where you present your arguments in support of your thesis.

Rebuttal or Counterargument : Here's where you present the opposing arguments and your rebuttals against them.

Conclusion : The final segment where you wrap up your argument, reaffirming your thesis statement.

Understanding the placement of the rebuttal within your essay will help you maintain a logical flow in your writing, ensuring that your readers can follow your arguments and counterarguments seamlessly. Let's delve deeper into the construction of a rebuttal in the next section.

Components of a Persuasive Rebuttal: Breaking It Down

A well-crafted rebuttal can significantly fortify your argumentative essay. However, the key to a persuasive rebuttal lies in its construction. Let's break down the components of an effective rebuttal:

Recognize the Opposing Argument : Begin by acknowledging the opposing point of view. This helps you establish credibility with your readers and shows them that you're not dismissing other perspectives.

Refute the Opposing Argument : Now, address why you believe the opposing viewpoint is incorrect or flawed. Use facts, logic, or reasoning to dismantle the counter-argument.

Support Your Rebuttal : Provide evidence, examples, or facts that support your rebuttal. This not only strengthens your argument but also adds credibility to your stance.

Transition to the Next Point : Finally, provide a smooth transition to the next part of your essay. This could be another argument in favor of your thesis or your conclusion, depending on the structure of your essay.

Each of these components is a crucial building block for a persuasive rebuttal. By structuring your rebuttal correctly, you can effectively refute opposing arguments and fortify your own stance. Let's move to some practical applications of these components in the next section.

Building Your Rebuttal: A Step-by-Step Guide

Writing a persuasive rebuttal may seem challenging, especially if you're new to argumentative essays. However, it's less daunting when broken down into smaller steps. Here's a practical step-by-step guide on how to construct your rebuttal:

Step 1: Identify the Counter-Arguments

The first step is to identify the potential counter-arguments that could be made against your thesis. This requires you to put yourself in your opposition's shoes and think critically about your own arguments.

Step 2: Choose the Strongest Counter-Argument

It's not practical or necessary to respond to every potential counter-argument. Instead, choose the most significant one(s) that, if left unaddressed, could undermine your argument.

Step 3: Research and Collect Evidence

Once you've chosen a counter-argument to rebut, it's time to research. Find facts, statistics, or examples that clearly refute the counter-argument. Remember, the stronger your evidence, the more persuasive your rebuttal will be.

Step 4: Write the Rebuttal

Using the components we outlined earlier, write your rebuttal. Begin by acknowledging the opposing argument, refute it using your evidence, and then transition smoothly to your next point.

Step 5: Review and Refine

Finally, review your rebuttal. Check for logical consistency, clarity, and strength of evidence. Refine as necessary to ensure your rebuttal is as persuasive and robust as possible.

Remember, practice makes perfect. The more you practice writing rebuttals, the more comfortable you'll become at identifying strong counter-arguments and refuting them effectively. Let's illustrate these steps with a practical example in the next section.

Practical Example: Constructing a Rebuttal

In this section, we'll apply the steps discussed above to construct a rebuttal. We'll use a hypothetical argumentative essay topic: "Should schools switch to a four-day school week?"

Thesis Statement : You are arguing in favor of a four-day school week, citing reasons such as improved student mental health, reduced operational costs for schools, and enhanced quality of education due to extended hours.

Identify Counter-Arguments : The opposition could argue that a four-day school week might lead to childcare issues for working parents or that the extended hours each day could lead to student burnout.

Choose the Strongest Counter-Argument : The point about childcare issues for working parents is potentially a significant concern that needs addressing.

Research and Collect Evidence : Research reveals that many community organizations offer affordable after-school programs. Additionally, some schools adopting a four-day week have offered optional fifth-day enrichment programs.

Write the Rebuttal : "While it's valid to consider the childcare challenges a four-day school week could impose on working parents, many community organizations provide affordable after-school programs. Moreover, some schools that have already adopted the four-day week offer an optional fifth-day enrichment program, demonstrating that viable solutions exist."

Review and Refine: Re-read your rebuttal, refine for clarity and impact, and ensure it integrates smoothly into your argument.

This is a simplified example, but it serves to illustrate the process of crafting a rebuttal. Let's move on to look at two full-length examples to further demonstrate effective rebuttals.

Case Study: Effective vs. Ineffective Rebuttal

Now that we've covered the theoretical and practical aspects, let's delve into two case studies. These examples will compare an effective rebuttal versus an ineffective one, so you can better understand what separates a compelling argument from a weak one.

Example 1: "Homework is unnecessary."

Ineffective Rebuttal : "I don't agree with you. Homework is important because it's part of the curriculum and it helps students study."

Effective Rebuttal : "Your concern about the overuse of homework is valid, considering the amount of stress students face today. However, research shows that homework, when thoughtfully assigned and not overused, can reinforce classroom learning, provide students with valuable time management skills, and help teachers evaluate student understanding."

The effective rebuttal acknowledges the opposing argument, uses evidence-backed reasoning, and strengthens the argument by showing the value of homework in the larger context of learning.

Example 2: "Standardized testing doesn't accurately measure student intelligence."

Ineffective Rebuttal : "I think you're wrong. Standardized tests have been around for a long time, and they wouldn't use them if they didn't work."

Effective Rebuttal : "Indeed, the limitations of standardized testing, such as potential cultural bias or the inability to measure creativity, are recognized issues. However, these tests are a tool—albeit an imperfect one—for comparing student achievement across regions and identifying areas where curriculum and teaching methods might need improvement. More comprehensive methods, blending standardized testing with other assessment forms, are promising approaches for future development."

The effective rebuttal in this instance acknowledges the flaws in standardized testing but highlights its role as a tool for larger educational system assessments and improvements.

Remember, an effective rebuttal is respectful, acknowledges the opposing viewpoint, provides strong counter-arguments, and integrates evidence. With practice, you will get better at crafting compelling rebuttals. In the next section, we will discuss some additional strategies to improve your rebuttal skills.

Final Thoughts

The art of constructing a compelling rebuttal is a crucial skill in argumentative essay writing. It's not just about presenting your own views but also about understanding, acknowledging, and effectively countering the opposing viewpoint. This makes your argument more robust and balanced, increasing its persuasive power.

However, developing this skill requires patience, practice, and a thoughtful approach. The techniques we've discussed in this guide can serve as a starting point, but remember that every argument is unique, and flexibility is key.

Always be ready to adapt and refine your rebuttal strategy based on the particular argument and evidence you're dealing with. And don't shy away from seeking feedback and learning from others - this is how we grow as writers and thinkers.

But remember, you're not alone on this journey. If you're ever struggling with writing your argumentative essay or crafting that perfect rebuttal, we're here to help. Our experienced writers at Writers Per Hour are well-versed in the nuances of argumentative writing and can assist you in achieving your academic goals.

So don't stress - embrace the challenge of argumentative writing, keep refining your skills, and remember that help is just a click away! In the next section, you'll find additional resources to continue learning and growing in your argumentative writing journey.

Additional Resources

As you continue to learn and develop your argumentative writing skills, having access to additional resources can be immensely beneficial. Here are some that you might find helpful:

Posts from Writers Per Hour Blog :

- How Significant Are Opposing Points of View in an Argument

- Writing a Hook for an Argumentative Essay

- Strong Argumentative Essay Topic Ideas

- Writing an Introduction for Your Argumentative Essay

External Resources :

- University of California Berkeley Student Learning Center: Writing Argumentative Essays

- Stanford Online Writing Center: Techniques of Persuasive Argument

Remember, mastery in argumentative writing doesn't happen overnight – it's a journey that requires patience, practice, and persistence. But with the right guidance and resources, you're already on the right path. And, of course, if you ever need assistance, our argumentative essay writing service services are always ready to help you reach your academic goals. Happy writing!

Share this article

Achieve Academic Success with Expert Assistance!

Crafted from Scratch for You.

Ensuring Your Work’s Originality.

Transform Your Draft into Excellence.

Perfecting Your Paper’s Grammar, Style, and Format (APA, MLA, etc.).

Calculate the cost of your paper

Get ideas for your essay

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

What is Rebuttal in an Argumentative Essay? (How to Write It)

by Antony W

April 7, 2022

Even if you have the most convincing evidence and reasons to explain your position on an issue, there will still be people in your audience who will not agree with you.

Usually, this creates an opportunity for counterclaims, which requires a response through rebuttal. So what exactly is rebuttal in an argumentative essay?

A rebuttal in an argumentative essay is a response you give to your opponent’s argument to show that the position they currently hold on an issue is wrong. While you agree with their counterargument, you point out the flaws using the strongest piece of evidence to strengthen your position.

To be clear, it’s hard to write an argument on an issue without considering counterclaim and rebuttals in the first place.

If you think about it, debatable topics require a consideration of both sides of an issue, which is why it’s important to learn about counterclaims and rebuttals in argumentative writing.

What is a Counterclaim in an Argument?

To understand why rebuttal comes into play in an argumentative essay, you first have to know what a counterclaim is and why it’s important in writing.

A counterclaim is an argument that an opponent makes to weaken your thesis. In particular, counterarguments try to show why your argument’s claim is wrong and try to propose an alternative to what you stand for.

From a writing standpoint, you have to recognize the counterclaims presented by the opposing side.

In fact, argumentative writing requires you to look at the two sides of an issue even if you’ve already taken a strong stance on it.

There are a number of benefits of including counterarguments in your argumentative essay:

- It shows your instructor that you’ve looked into both sides of the argument and recognize that some readers may not share your views initially.

- You create an opportunity to provide a strong rebuttal to the counterclaims, so readers see them before they finish reading the essay.

- You end up strengthening your writing because the essay turns out more objective than it would without recognizing the counterclaims from the opposing side.

What is Rebuttal in Argumentative Essay?

Your opponent will always look for weaknesses in your argument and try the best they can to show that you’re wrong.

Since you have solid grounds that your stance on an issue is reasonable, truthful, or more meaningful, you have to give a solid response to the opposition.

This is where rebuttal comes in.

In argumentative writing, rebuttal refers to the answer you give directly to an opponent in response to their counterargument. The answer should be a convincing explanation that shows an opponent why and/or how they’re wrong on an issue.

How to Write a Rebuttal Paragraph in Argumentative Essay

Now that you understand the connection between a counterclaim and rebuttal in an argumentative writing, let’s look at some approaches that you can use to refute your opponent’s arguments.

1. Point Out the Errors in the Counterargument

You’ve taken a stance on an issue for a reason, and mostly it’s because you believe yours is the most reasonable position based on the data, statistics, and the information you’ve collected.

Now that there’s a counterargument that tries to challenge your position, you can refute it by mentioning the flaws in it.

It’s best to analyze the counterargument carefully. Doing so will make it easy for you to identify the weaknesses, which you can point out and use the strongest points for rebuttal

2. Give New Points that Contradict the Counterclaims

Imagine yourself in a hall full of debaters. On your left side is an audience that agrees with your arguable claim and on your left is a group of listeners who don’t buy into your argument.

Your opponents in the room are not holding back, especially because they’re constantly raising their hands to question your information.

To win them over in such a situation, you have to play smart by recognizing their stance on the issue but then explaining why they’re wrong.

Now, take a closer look at the structure of an argument . You’ll notice that it features a section for counterclaims, which means you have to address them if your essay must stand out.

Here, it’s ideal to recognize and agree with the counterargument that the opposing side presents. Then, present a new point of view or facts that contradict the arguments.

Doing so will get the opposing side to consider your stance, even if they don’t agree with you entirely.

3. Twist Facts in Favor of Your Argument

Sometimes the other side of the argument may make more sense than yours does. However, that doesn’t mean you have to concede entirely.

You can agree with the other side of the argument, but then twist facts and provide solid evidence to suit your argument.

This strategy can work for just about any topic, including the most complicated or controversial ones that you have never dealt with before.

4. Making an Emotional Plea

Making an emotional plea isn’t a powerful rebuttal strategy, but it can also be a good option to consider.

It’s important to make sure that the emotional appeal you make outweighs the argument that your opponent brings forth.

Given that it’s often the least effective option in most arguments, making an emotional appeal should be a last resort if all the other options fail.

Final Thoughts

As you can see, counterclaims are important in an argumentative essay and there’s more than one way to give your rebuttal.

Whichever approach you use, make sure you use the strongest facts, stats, evidence, or argument to prove that your position on an issue makes more sense that what your opponents currently hold.

Lastly, if you feel like your essay topic is complicated and you have only a few hours to complete the assignment, you can get in touch with Help for Assessment and we’ll point you in the right direction so you get your essay done right.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

How to Write a Rebuttal Essay — An Easy Guide to Follow

Ever wondered how to write a rebuttal essay? Face this academic assignment for the first time and can’t find an understandable guide to follow? Don’t worry because here you’ll find a detailed guideline allowing you to set the record straight and understand what tips to follow while writing. We’ll take a look at all the aspects of writing, check what rebuttal in an essay is and list all tips to follow.

What Is a Rebuttal in an Essay — Simple Explanation

Academicians also call this form of writing a counter-argument essay. Its principal mission is to respond to some points made by a person. If you render a decision to answer one or another argument, you should present a rebuttal which is also known as a counter-argument. Otherwise stated, it is a simple attempt to disprove some statements by suggesting a counter-argument.

At a glance, this task seems to be quite challenging. However, rebuttal argument essay writing doesn’t take a massive amount of time. You just need to air your personal opinion on one or another situation.

Related essays:

- Economic recession essay

- Hamlet & formal structure

- The counter revolution and the 1960s essay

- Viacom Strategic Analysis essay

Nevertheless, your viewpoint should be based on your research and comprise a strong thesis statement. An excellent essay can even change the opinion of the intended audience. Thus, you need to be very attentive while writing and use only strong and double-checked arguments.

How to Do a Rebuttal in an Essay — Useful Tutorial

Firstly, you should conduct simple research before you start expressing your ideas. Don’t tend to procrastinate this task because it is tough to organize your thoughts when your deadline is dangerously close. If you don’t have a desire to spend the whole night poring over the books, it is better to start processing the literature as soon as possible. It would be great if you subdivide this task into a few sections. As a result, it will be easier to work!

The majority of academicians have not the slightest idea how to answer the question of how to start a rebuttal in an essay. In sober fact, you need to start with a strong introduction, comprising a thesis statement. Besides, your introductory part should explain what particular situation you are going to discuss. Your core audience should look it through and immediately understand what position you desire to explore.

You should create a list of claims and build your essay structure in the way allowing you to explain each claim one by one. Writing a rebuttal essay, you should follow a pre-written outline. As a result, you won’t face difficulties with the structure.

For instance, there is a particular situation, and you don’t agree with it. You wish to prove the targeted audience that your idea is correct. In this scenario, you need to state your opinion in a thesis statement and list all counter-arguments one by one.

Each rebuttal paragraph should be short and complete. Besides, you should avoid making too general statements because your targeted audience won’t understand what you mean. If you wish to air your proof-point, you should try to make more precise arguments. As a result, your readers won’t face difficulties trying to understand what you mean.

Rebuttal Essay Outline — Why Should You Create It

As well as any other academic paper, this one also should have a plan to follow. Your rebuttal essay outline is a sterling opportunity to organize your thoughts and create an approximate plan to follow. Commonly, your outline should look like this:

- Short but informative introduction with a thesis statement (just a few sentences).

- 3 or 5 body paragraphs presenting all counter-arguments.

- Strong conclusion where you should repeat your opinion once again.

For you not to forget some ideas, we highly recommend writing a list of all claims you wish to discuss in all paragraphs. Even if you are a seasoned writer who is engaged in this area and deals with creative assignments on a rolling basis, you won’t regret it. You’ll spend a few minutes creating the outline, but the general content of your essay will be considerably better.

Top-7 Rebuttal Essay Topics for Students

If you really can’t render a correct decision and pick a worthy topic, look through the rebuttal essay ideas published below. You can’t go wrong if you choose one of the below-listed ideas:

- Is it necessary to sentence juveniles to life imprisonment?

- Why are electro cars better for the environment?

- Distance learning is more effective than the traditional approach to education.

- Why should animal testing be forbidden?

- Modern drones can help police solve the crimes faster.

- Why should smoking marijuana be prohibited?

- Why should the screentime of kids be limited?

We hope our tips will help you catch the inspiration and create a compelling essay which will make your audience think of the discussed problem and even change their minds.

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, counterarguments – rebuttal – refutation.

- © 2023 by Roberto León - Georgia College & State University

Ignoring what your target audience thinks and feels about your argument isn't a recipe for success. Instead, engage in audience analysis : ask yourself, "How is your target audience likely to respond to your propositions? What counterarguments -- arguments about your argument -- will your target audience likely raise before considering your propositions?"

Counterargument Definition

C ounterargument refers to an argument given in response to another argument that takes an alternative approach to the issue at hand.

C ounterargument may also be known as rebuttal or refutation .

Related Concepts

Audience Awareness ; Authority (in Speech and Writing) ; Critical Literacy ; Ethos ; Openness ; Researching Your Audience

Guide to Counterarguments in Writing Studies

Counterarguments are a topic of study in Writing Studies as

- Rhetors engage in rhetorical reasoning : They analyze the rebuttals their target audiences may have to their claims , interpretations , propositions, and proposals

- Rhetors may develop counterarguments by questioning a rhetor’s backing , data , qualifiers, and/or warrants

- Rhetors begin arguments with sincere summaries of counterarguments

- a strategy of Organization .

Learning about the placement of counterarguments in Toulmin Argument , Arisotelian Argument , and Rogerian Argument will help you understand when you need to introduce counterarguments and how thoroughly you need to address them.

Why Do Counterarguments Matter?

If your goal is clarity and persuasion, you cannot ignore what your target audience thinks, feels, and does about the argument. To communicate successfully with audiences, rhetors need to engage in audience analysis : they need to understand the arguments against their argument that the audience may hold.

Imagine that you are scrolling through your social media feed when you see a post from an old friend. As you read, you immediately feel that your friend’s post doesn’t make sense. “They can’t possibly believe that!” you tell yourself. You quickly reply “I’m not sure I agree. Why do you believe that?” Your friend then posts a link to an article and tells you to see for yourself.

There are many ways to analyze your friend’s social media post or the professor’s article your friend shared. You might, for example, evaluate the professor’s article by using the CRAAP Test or by conducting a rhetorical analysis of their aims and ethos . After engaging in these prewriting heuristics to get a better sense of what your friend knows and feels about the topic at hand, you may feel more prepared to respond to their arguments and also sense how they might react to your post.

Toulmin Counterarguments

There’s more than one way to counter an argument.

In Toulmin Argument , a counterargument can be made against the writer’s claim by questioning their backing , data , qualifiers, and/or warrants . For example, let’s say we wrote the following argument:

“Social media is bad for you (claim) because it always (qualifier) promotes an unrealistic standard of beauty (backing). In this article, researchers found that most images were photoshopped (data). Standards should be realistic; if they are not, those standards are bad (warrant).”

Besides noting we might have a series of logical fallacies here, counterarguments and dissociations can be made against each of these parts:

- Against the qualifier: Social media does not always promote unrealistic standards.

- Against the backing : Social media presents but does not promote unrealistic standards.

- Against the data : This article focuses on Instagram; these findings are not applicable to Twitter.

- Against the warrant : How we approach standards matters more than the standards themselves; standards do not need to be realistic, but rather we need to be realistic about how we approach standards.

In generating and considering counterarguments and conditions of rebuttal, it is important to consider how we approach alternative views. Alternative viewpoints are opportunities not only to strengthen and contrast our own arguments with those of others; alternative viewpoints are also opportunities to nuance and develop our own arguments.

Let us continue to look at our social media argument and potential counterarguments. We might prepare responses to each of these potential counterarguments, anticipating the ways in which our audience might try to shift how we frame this situation. However, we might also concede that some of these counterarguments actually have good points.

For example, we might still believe that social media is bad, but perhaps we also need to consider more about

- What factors make it worse (nuance the qualifier)?

- Whether or not social media is a neutral tool or whether algorithms take advantage of our baser instincts (nuance the backing )

- Whether this applies to all social media or whether we want to focus on just one social media platform (nuance the data )

- How should we approach social standards (nuance the warrant )?

Identifying counterarguments can help us strengthen our arguments by helping us recognize the complexity of the issue at hand.

Neoclassical Argument – Aristotelian Argument

Learn how to compose a counterargument passage or section.

While Toulmin Argument focuses on the nuts and bolts of argumentation, a counterargument can also act as an entire section of an Aristotelian Argument . This section typically comes after you have presented your own lines of argument and evidence .

This section typically consists of two rhetorical moves :

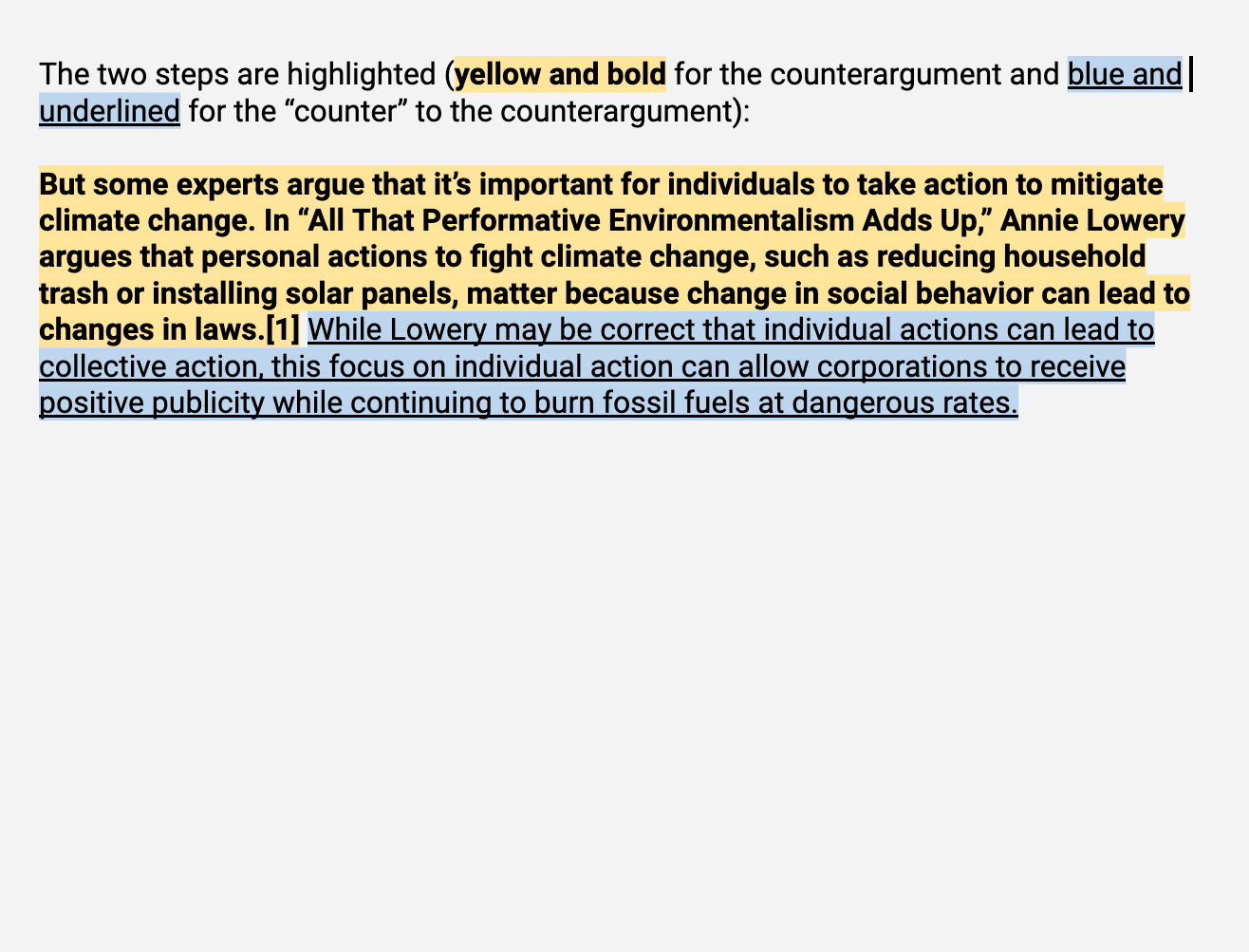

Examples of Counterarguments

By introducing counterarguments, we show we are aware of alternative viewpoints— other definitions, explanations, meanings, solutions, etc. We want to show that we are good listeners and aren’t committing the strawman fallacy . We also concede some of the alternative viewpoints that we find most persuasive. By making concessions, we can show that we are reasonable ( ethos ) and that we are listening . Rogerian Argument is an example of building listening more fully into our writing.

Using our social media example, we might write:

I recognize that in many ways social media is only as good as the content that people upload to it. As Professor X argues, social media amplifies both the good and the bad of human nature.

Once we’ve shown that we understand and recognize good arguments when we see them, we put forward our response to the counterclaim. In our response, we do not simply dismiss alternative viewpoints, but provide our own backing, data, and warrants to show that we, in fact, have the more compelling position.

To counter Professor X’s argument, we might write:

At the same time, there are clear instances where social media amplifies the bad over the good by design. While content matters, the design of social media is only as good as the people who created it.

Through conceding and countering, we can show that we recognize others’ good points and clarify where we stand in relation to others’ arguments.

Counterarguments and Organization

Learn when and how to weave counterarguments into your texts.

As we write, it is also important to consider the extent to which we will respond to counterarguments. If we focus too much on counterarguments, we run the risk of downplaying our own contributions. If we focus too little on counterarguments, we run the risk of seeming aloof and unaware of reality. Ideally, we will be somewhere in between these two extremes.

There are many places to respond to counterarguments in our writing. Where you place your counterarguments will depend on the rhetorical situation (ex: audience , purpose, subject ), your rhetorical stance (how you want to present yourself), and your sense of kairos . Here are some common choices based on a combination of these rhetorical situation factors:

- If a counterargument is well-established for your audience, you may want to respond to that counterargument earlier in your essay, clearing the field and creating space for you to make your own arguments. An essay about gun rights, for example, would need to make it clear very quickly that it is adding something new to this old debate. Doing so shows your audience that you are very aware of their needs.

- If a counterargument is especially well-established for your audience and you simply want to prove that it is incorrect rather than discuss another solution, you might respond to it point by point, structuring your whole essay as an extended refutation. Fact-checking and commentary articles often make this move. Responding point by point shows that you take the other’s point of view seriously.

- If you are discussing something relatively unknown or new to your audience (such as a problem with black mold in your dormitory), you might save your response for after you have made your points. Including alternative viewpoints even here shows that you are aware of the situation and have nothing to hide.

Whichever you choose, remember that counterarguments are opportunities to ethically engage with alternative viewpoints and your audience.

The following questions can guide you as you begin to think about counterarguments:

- What is your argument ? What alternative positions might exist as counterarguments to your argument?

- How can considering counterarguments strengthen your argument?

- Given possible counterarguments, what points might you reconsider or concede?

- To what extent might you respond to counterarguments in your essay so that they can create and respond to the rhetorical situation ?

- Where might you place your counterarguments in your essay?

- What might including counterarguments do for your ethos ?

Recommended Resources

- Sweetland Center for Writing (n.d.). “ How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument? ” University of Michigan.

- The Writing Center (n.d.) “ All About Counterarguments .” George Mason University.

- Lachner, N. (n.d.). “ Counterarguments .” University of Nevada Reno, University Writing and Speaking Center.

- Jeffrey, R. (n.d.). “ Questions for Thinking about Counterarguments .” In M. Gagich and E. Zickel, A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing.

- Kause, S. (2011). “ On the Other Hand: The Role of Antithetical Writing in First Year Composition Courses .” Writing Spaces Vol. 2.

- Burton, G. “ Refutatio .” Silvae Rhetoricae.

Toulmin, S. (1958). The Uses of Argument. Cambridge University Press.

Perelman, C. and Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1971). “The Dissociation of Concepts”; “The Interaction of Arguments,” in The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation (pp. 411-459, 460-508), University of Notre Dame Press.

Mozafari, C. (2018). “Crafting Counterarguments,” in Fearless Writing: Rhetoric, Inquiry, Argument (pp. 333-337), MacMillian Learning

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

Hill Street Studios/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In rhetoric, refutation is the part of an argument in which a speaker or writer counters opposing points of view. Also called confutation .

Refutation is "the key element in debate," say the authors of The Debater's Guide (2011). Refutation "makes the whole process exciting by relating ideas and arguments from one team to those of the other" ( The Debater's Guide , 2011).

In speeches, refutation and confirmation are often presented "conjointly with one another" (in the words of the unknown author of Ad Herrenium ): support for a claim ( confirmation ) can be enhanced by a challenge to the validity of an opposing claim ( refutation ).

In classical rhetoric , refutation was one of the rhetorical exercises known as the progymnasmata .

Examples and Observations

"Refutation is the part of an essay that disproves the opposing arguments. It is always necessary in a persuasive paper to refute or answer those arguments. A good method for formulating your refutation is to put yourself in the place of your readers, imagining what their objections might be. In the exploration of the issues connected with your subject, you may have encountered possible opposing viewpoints in discussions with classmates or friends. In the refutation, you refute those arguments by proving the opposing basic proposition untrue or showing the reasons to be invalid...In general, there is a question about whether the refutation should come before or after the proof . The arrangement will differ according to the particular subject and the number and strength of the opposing arguments. If the opposing arguments are strong and widely held, they should be answered at the beginning. In this case, the refutation becomes a large part of the proof . . .. At other times when the opposing arguments are weak, the refutation will play only a minor part in the overall proof." -Winifred Bryan Horner, Rhetoric in the Classical Tradition . St. Martin's, 1988

Indirect and Direct Refutation

- "Debaters refute through an indirect means when they use counter-argument to attack the case of an opponent. Counter-argument is the demonstration of such a high degree of probability for your conclusions that the opposing view loses its probability and is rejected... Direct refutation attacks the arguments of the opponent with no reference to the constructive development of an opposing view...The most effective refutation, as you can probably guess, is a combination of the two methods so that the strengths of the attack come from both the destruction of the opponents' views and the construction of an opposing view." -Jon M. Ericson, James J. Murphy, and Raymond Bud Zeuschner, The Debater's Guide , 4th ed. Southern Illinois University Press, 2011

- "An effective refutation must speak directly to an opposing argument. Often writers or speakers will claim to be refuting the opposition, but rather than doing so directly, will simply make another argument supporting their own side. This is a form of the fallacy of irrelevance through evading the issue." -Donald Lazere, Reading and Writing for Civic Literacy: The Critical Citizen's Guide to Argumentative Rhetoric . Taylor & Francis, 2009

Cicero on Confirmation and Refutation

"[T]he statement of the case . . . must clearly point out the question at issue. Then must be conjointly built up the great bulwarks of your cause, by fortifying your own position, and weakening that of your opponent; for there is only one effectual method of vindicating your own cause, and that includes both the confirmation and refutation. You cannot refute the opposite statements without establishing your own; nor can you, on the other hand, establish your own statements without refuting the opposite; their union is demanded by their nature, their object, and their mode of treatment. The whole speech is, in most cases, brought to a conclusion by some amplification of the different points, or by exciting or mollifying the judges; and every aid must be gathered from the preceding, but more especially from the concluding parts of the address, to act as powerfully as possible upon their minds, and make them zealous converts to your cause." -Cicero, De Oratore , 55 BC

Richard Whately on Refutation

"Refutation of Objections should generally be placed in the midst of the Argument; but nearer the beginning than the end. If indeed very strong objections have obtained much currency, or have been just stated by an opponent, so that what is asserted is likely to be regarded as paradoxical , it may be advisable to begin with a Refutation." -Richard Whately, Elements of Rhetoric , 1846)

FCC Chairman William Kennard's Refutation

"There will be those who say 'Go slow. Don't upset the status quo.' No doubt we will hear this from competitors who perceive that they have an advantage today and want regulation to protect their advantage. Or we will hear from those who are behind in the race to compete and want to slow down deployment for their own self-interest. Or we will hear from those that just want to resist changing the status quo for no other reason than change brings less certainty than the status quo. They will resist change for that reason alone. So we may well hear from a whole chorus of naysayers. And to all of them, I have only one response: we cannot afford to wait. We cannot afford to let the homes and schools and businesses throughout America wait. Not when we have seen the future. We have seen what high capacity broadband can do for education and for our economy. We must act today to create an environment where all competitors have a fair shot at bringing high capacity bandwidth to consumers—especially residential consumers. And especially residential consumers in rural and underserved areas." -William Kennard, Chairman of the FCC, July 27, 1998

Etymology: From the Old English, "beat"

Pronunciation: REF-yoo-TAY-shun

- The Parts of a Speech in Classical Rhetoric

- Proof in Rhetoric

- Confirmation in Speech and Rhetoric

- Usage and Examples of a Rebuttal

- Arrangement in Composition and Rhetoric

- What Is the Straw Man Fallacy?

- Rogerian Argument: Definition and Examples

- AP English Exam: 101 Key Terms

- Conceding and Refuting in English

- Reductio Ad Absurdum in Argument

- What Does "Dissoi Logoi" Mean?

- What Is a Rhetorical Device? Definition, List, Examples

- 5 Steps to Writing a Position Paper

- Oration (Classical Rhetoric)

- Elenchus (argumentation)

- Appeal to Humor as Fallacy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

21 Argument, Counterargument, & Refutation

In academic writing, we often use an Argument essay structure. Argument essays have these familiar components, just like other types of essays:

- Introduction

- Body Paragraphs

But Argument essays also contain these particular elements:

- Debatable thesis statement in the Introduction

- Argument – paragraphs which show support for the author’s thesis (for example: reasons, evidence, data, statistics)

- Counterargument – at least one paragraph which explains the opposite point of view

- Concession – a sentence or two acknowledging that there could be some truth to the Counterargument

- Refutation (also called Rebuttal) – sentences which explain why the Counterargument is not as strong as the original Argument

Consult Introductions & Titles for more on writing debatable thesis statements and Paragraphs ~ Developing Support for more about developing your Argument.

Imagine that you are writing about vaping. After reading several articles and talking with friends about vaping, you decide that you are strongly opposed to it.

Which working thesis statement would be better?

- Vaping should be illegal because it can lead to serious health problems.

Many students do not like vaping.

Because the first option provides a debatable position, it is a better starting point for an Argument essay.

Next, you would need to draft several paragraphs to explain your position. These paragraphs could include facts that you learned in your research, such as statistics about vapers’ health problems, the cost of vaping, its effects on youth, its harmful effects on people nearby, and so on, as an appeal to logos . If you have a personal story about the effects of vaping, you might include that as well, either in a Body Paragraph or in your Introduction, as an appeal to pathos .

A strong Argument essay would not be complete with only your reasons in support of your position. You should also include a Counterargument, which will show your readers that you have carefully researched and considered both sides of your topic. This shows that you are taking a measured, scholarly approach to the topic – not an overly-emotional approach, or an approach which considers only one side. This helps to establish your ethos as the author. It shows your readers that you are thinking clearly and deeply about the topic, and your Concession (“this may be true”) acknowledges that you understand other opinions are possible.

Here are some ways to introduce a Counterargument:

- Some people believe that vaping is not as harmful as smoking cigarettes.

- Critics argue that vaping is safer than conventional cigarettes.

- On the other hand, one study has shown that vaping can help people quit smoking cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then go on to explain more about this position; you would give evidence here from your research about the point of view that opposes your own opinion.

Here are some ways to begin a Concession and Refutation:

- While this may be true for some adults, the risks of vaping for adolescents outweigh its benefits.

- Although these critics may have been correct before, new evidence shows that vaping is, in some cases, even more harmful than smoking.

- This may have been accurate for adults wishing to quit smoking; however, there are other methods available to help people stop using cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then continue your Refutation by explaining more reasons why the Counterargument is weak. This also serves to explain why your original Argument is strong. This is a good opportunity to prove to your readers that your original Argument is the most worthy, and to persuade them to agree with you.

Activity ~ Practice with Counterarguments, Concessions, and Refutations

A. Examine the following thesis statements with a partner. Is each one debatable?

B. Write your own Counterargument, Concession, and Refutation for each thesis statement.

Thesis Statements:

- Online classes are a better option than face-to-face classes for college students who have full-time jobs.

- Students who engage in cyberbullying should be expelled from school.

- Unvaccinated children pose risks to those around them.

- Governments should be allowed to regulate internet access within their countries.

Is this chapter:

…too easy, or you would like more detail? Read “ Further Your Understanding: Refutation and Rebuttal ” from Lumen’s Writing Skills Lab.

Note: links open in new tabs.

reasoning, logic

emotion, feeling, beliefs

moral character, credibility, trust, authority

goes against; believes the opposite of something

ENGLISH 087: Academic Advanced Writing Copyright © 2020 by Nancy Hutchison is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Organizing Your Argument

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

How can I effectively present my argument?

In order for your argument to be persuasive, it must use an organizational structure that the audience perceives as both logical and easy to parse. Three argumentative methods —the Toulmin Method , Classical Method , and Rogerian Method — give guidance for how to organize the points in an argument.

Note that these are only three of the most popular models for organizing an argument. Alternatives exist. Be sure to consult your instructor and/or defer to your assignment’s directions if you’re unsure which to use (if any).

Toulmin Method

The Toulmin Method is a formula that allows writers to build a sturdy logical foundation for their arguments. First proposed by author Stephen Toulmin in The Uses of Argument (1958), the Toulmin Method emphasizes building a thorough support structure for each of an argument's key claims.

The basic format for the Toulmin Method is as follows:

Claim: In this section, you explain your overall thesis on the subject. In other words, you make your main argument.

Data (Grounds): You should use evidence to support the claim. In other words, provide the reader with facts that prove your argument is strong.

Warrant (Bridge): In this section, you explain why or how your data supports the claim. As a result, the underlying assumption that you build your argument on is grounded in reason.

Backing (Foundation): Here, you provide any additional logic or reasoning that may be necessary to support the warrant.

Counterclaim: You should anticipate a counterclaim that negates the main points in your argument. Don't avoid arguments that oppose your own. Instead, become familiar with the opposing perspective. If you respond to counterclaims, you appear unbiased (and, therefore, you earn the respect of your readers). You may even want to include several counterclaims to show that you have thoroughly researched the topic.

Rebuttal: In this section, you incorporate your own evidence that disagrees with the counterclaim. It is essential to include a thorough warrant or bridge to strengthen your essay’s argument. If you present data to your audience without explaining how it supports your thesis, your readers may not make a connection between the two, or they may draw different conclusions.

Example of the Toulmin Method:

Claim: Hybrid cars are an effective strategy to fight pollution.

Data1: Driving a private car is a typical citizen's most air-polluting activity.

Warrant 1: Due to the fact that cars are the largest source of private (as opposed to industrial) air pollution, switching to hybrid cars should have an impact on fighting pollution.

Data 2: Each vehicle produced is going to stay on the road for roughly 12 to 15 years.

Warrant 2: Cars generally have a long lifespan, meaning that the decision to switch to a hybrid car will make a long-term impact on pollution levels.

Data 3: Hybrid cars combine a gasoline engine with a battery-powered electric motor.

Warrant 3: The combination of these technologies produces less pollution.

Counterclaim: Instead of focusing on cars, which still encourages an inefficient culture of driving even as it cuts down on pollution, the nation should focus on building and encouraging the use of mass transit systems.

Rebuttal: While mass transit is an idea that should be encouraged, it is not feasible in many rural and suburban areas, or for people who must commute to work. Thus, hybrid cars are a better solution for much of the nation's population.

Rogerian Method

The Rogerian Method (named for, but not developed by, influential American psychotherapist Carl R. Rogers) is a popular method for controversial issues. This strategy seeks to find a common ground between parties by making the audience understand perspectives that stretch beyond (or even run counter to) the writer’s position. Moreso than other methods, it places an emphasis on reiterating an opponent's argument to his or her satisfaction. The persuasive power of the Rogerian Method lies in its ability to define the terms of the argument in such a way that:

- your position seems like a reasonable compromise.

- you seem compassionate and empathetic.

The basic format of the Rogerian Method is as follows:

Introduction: Introduce the issue to the audience, striving to remain as objective as possible.

Opposing View : Explain the other side’s position in an unbiased way. When you discuss the counterargument without judgement, the opposing side can see how you do not directly dismiss perspectives which conflict with your stance.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): This section discusses how you acknowledge how the other side’s points can be valid under certain circumstances. You identify how and why their perspective makes sense in a specific context, but still present your own argument.

Statement of Your Position: By this point, you have demonstrated that you understand the other side’s viewpoint. In this section, you explain your own stance.

Statement of Contexts : Explore scenarios in which your position has merit. When you explain how your argument is most appropriate for certain contexts, the reader can recognize that you acknowledge the multiple ways to view the complex issue.

Statement of Benefits: You should conclude by explaining to the opposing side why they would benefit from accepting your position. By explaining the advantages of your argument, you close on a positive note without completely dismissing the other side’s perspective.

Example of the Rogerian Method:

Introduction: The issue of whether children should wear school uniforms is subject to some debate.

Opposing View: Some parents think that requiring children to wear uniforms is best.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): Those parents who support uniforms argue that, when all students wear the same uniform, the students can develop a unified sense of school pride and inclusiveness.

Statement of Your Position : Students should not be required to wear school uniforms. Mandatory uniforms would forbid choices that allow students to be creative and express themselves through clothing.

Statement of Contexts: However, even if uniforms might hypothetically promote inclusivity, in most real-life contexts, administrators can use uniform policies to enforce conformity. Students should have the option to explore their identity through clothing without the fear of being ostracized.

Statement of Benefits: Though both sides seek to promote students' best interests, students should not be required to wear school uniforms. By giving students freedom over their choice, students can explore their self-identity by choosing how to present themselves to their peers.

Classical Method

The Classical Method of structuring an argument is another common way to organize your points. Originally devised by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (and then later developed by Roman thinkers like Cicero and Quintilian), classical arguments tend to focus on issues of definition and the careful application of evidence. Thus, the underlying assumption of classical argumentation is that, when all parties understand the issue perfectly, the correct course of action will be clear.

The basic format of the Classical Method is as follows:

Introduction (Exordium): Introduce the issue and explain its significance. You should also establish your credibility and the topic’s legitimacy.

Statement of Background (Narratio): Present vital contextual or historical information to the audience to further their understanding of the issue. By doing so, you provide the reader with a working knowledge about the topic independent of your own stance.

Proposition (Propositio): After you provide the reader with contextual knowledge, you are ready to state your claims which relate to the information you have provided previously. This section outlines your major points for the reader.

Proof (Confirmatio): You should explain your reasons and evidence to the reader. Be sure to thoroughly justify your reasons. In this section, if necessary, you can provide supplementary evidence and subpoints.

Refutation (Refuatio): In this section, you address anticipated counterarguments that disagree with your thesis. Though you acknowledge the other side’s perspective, it is important to prove why your stance is more logical.

Conclusion (Peroratio): You should summarize your main points. The conclusion also caters to the reader’s emotions and values. The use of pathos here makes the reader more inclined to consider your argument.

Example of the Classical Method:

Introduction (Exordium): Millions of workers are paid a set hourly wage nationwide. The federal minimum wage is standardized to protect workers from being paid too little. Research points to many viewpoints on how much to pay these workers. Some families cannot afford to support their households on the current wages provided for performing a minimum wage job .

Statement of Background (Narratio): Currently, millions of American workers struggle to make ends meet on a minimum wage. This puts a strain on workers’ personal and professional lives. Some work multiple jobs to provide for their families.

Proposition (Propositio): The current federal minimum wage should be increased to better accommodate millions of overworked Americans. By raising the minimum wage, workers can spend more time cultivating their livelihoods.

Proof (Confirmatio): According to the United States Department of Labor, 80.4 million Americans work for an hourly wage, but nearly 1.3 million receive wages less than the federal minimum. The pay raise will alleviate the stress of these workers. Their lives would benefit from this raise because it affects multiple areas of their lives.

Refutation (Refuatio): There is some evidence that raising the federal wage might increase the cost of living. However, other evidence contradicts this or suggests that the increase would not be great. Additionally, worries about a cost of living increase must be balanced with the benefits of providing necessary funds to millions of hardworking Americans.

Conclusion (Peroratio): If the federal minimum wage was raised, many workers could alleviate some of their financial burdens. As a result, their emotional wellbeing would improve overall. Though some argue that the cost of living could increase, the benefits outweigh the potential drawbacks.

English Current

ESL Lesson Plans, Tests, & Ideas

- North American Idioms

- Business Idioms

- Idioms Quiz

- Idiom Requests

- Proverbs Quiz & List

- Phrasal Verbs Quiz

- Basic Phrasal Verbs

- North American Idioms App

- A(n)/The: Help Understanding Articles

- The First & Second Conditional

- The Difference between 'So' & 'Too'

- The Difference between 'a few/few/a little/little'

- The Difference between "Other" & "Another"

- Check Your Level

- English Vocabulary

- Verb Tenses (Intermediate)

- Articles (A, An, The) Exercises

- Prepositions Exercises

- Irregular Verb Exercises

- Gerunds & Infinitives Exercises

- Discussion Questions

- Speech Topics

- Argumentative Essay Topics

- Top-rated Lessons

- Intermediate

- Upper-Intermediate

- Reading Lessons

- View Topic List

- Expressions for Everyday Situations

- Travel Agency Activity

- Present Progressive with Mr. Bean

- Work-related Idioms

- Adjectives to Describe Employees

- Writing for Tone, Tact, and Diplomacy

- Speaking Tactfully

- Advice on Monetizing an ESL Website

- Teaching your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation

- Teaching Different Levels

- Teaching Grammar in Conversation Class

- Members' Home

- Update Billing Info.

- Cancel Subscription

- North American Proverbs Quiz & List

- North American Idioms Quiz

- Idioms App (Android)

- 'Be used to'" / 'Use to' / 'Get used to'

- Ergative Verbs and the Passive Voice

- Keywords & Verb Tense Exercises

- Irregular Verb List & Exercises

- Non-Progressive (State) Verbs

- Present Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Present Simple vs. Present Progressive

- Past Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Subject Verb Agreement

- The Passive Voice

- Subject & Object Relative Pronouns

- Relative Pronouns Where/When/Whose

- Commas in Adjective Clauses

- A/An and Word Sounds

- 'The' with Names of Places

- Understanding English Articles

- Article Exercises (All Levels)

- Yes/No Questions

- Wh-Questions

- How far vs. How long

- Affect vs. Effect

- A few vs. few / a little vs. little

- Boring vs. Bored

- Compliment vs. Complement

- Die vs. Dead vs. Death

- Expect vs. Suspect

- Experiences vs. Experience

- Go home vs. Go to home

- Had better vs. have to/must

- Have to vs. Have got to

- I.e. vs. E.g.

- In accordance with vs. According to

- Lay vs. Lie

- Make vs. Do

- In the meantime vs. Meanwhile

- Need vs. Require

- Notice vs. Note

- 'Other' vs 'Another'

- Pain vs. Painful vs. In Pain

- Raise vs. Rise

- So vs. Such

- So vs. So that

- Some vs. Some of / Most vs. Most of

- Sometimes vs. Sometime

- Too vs. Either vs. Neither

- Weary vs. Wary

- Who vs. Whom

- While vs. During

- While vs. When

- Wish vs. Hope

- 10 Common Writing Mistakes

- 34 Common English Mistakes

- First & Second Conditionals

- Comparative & Superlative Adjectives

- Determiners: This/That/These/Those

- Check Your English Level

- Grammar Quiz (Advanced)

- Vocabulary Test - Multiple Questions

- Vocabulary Quiz - Choose the Word

- Verb Tense Review (Intermediate)

- Verb Tense Exercises (All Levels)

- Conjunction Exercises

- List of Topics

- Business English

- Games for the ESL Classroom

- Pronunciation

- Teaching Your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation Class

Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation

An argumentative essay presents an argument for or against a topic. For example, if your topic is working from home , then your essay would either argue in favor of working from home (this is the for side) or against working from home.

Like most essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction that ends with the writer's position (or stance) in the thesis statement .

Introduction Paragraph

(Background information....)

- Thesis statement : Employers should give their workers the option to work from home in order to improve employee well-being and reduce office costs.

This thesis statement shows that the two points I plan to explain in my body paragraphs are 1) working from home improves well-being, and 2) it allows companies to reduce costs. Each topic will have its own paragraph. Here's an example of a very basic essay outline with these ideas:

- Background information

Body Paragraph 1

- Topic Sentence : Workers who work from home have improved well-being .

- Evidence from academic sources

Body Paragraph 2

- Topic Sentence : Furthermore, companies can reduce their expenses by allowing employees to work at home .

- Summary of key points

- Restatement of thesis statement

Does this look like a strong essay? Not really . There are no academic sources (research) used, and also...

You Need to Also Respond to the Counter-Arguments!

The above essay outline is very basic. The argument it presents can be made much stronger if you consider the counter-argument , and then try to respond (refute) its points.

The counter-argument presents the main points on the other side of the debate. Because we are arguing FOR working from home, this means the counter-argument is AGAINST working from home. The best way to find the counter-argument is by reading research on the topic to learn about the other side of the debate. The counter-argument for this topic might include these points:

- Distractions at home > could make it hard to concentrate

- Dishonest/lazy people > might work less because no one is watching

Next, we have to try to respond to the counter-argument in the refutation (or rebuttal/response) paragraph .

The Refutation/Response Paragraph

The purpose of this paragraph is to address the points of the counter-argument and to explain why they are false, somewhat false, or unimportant. So how can we respond to the above counter-argument? With research !

A study by Bloom (2013) followed workers at a call center in China who tried working from home for nine months. Its key results were as follows:

- The performance of people who worked from home increased by 13%

- These workers took fewer breaks and sick-days

- They also worked more minutes per shift

In other words, this study shows that the counter-argument might be false. (Note: To have an even stronger essay, present data from more than one study.) Now we have a refutation.

Where Do We Put the Counter-Argument and Refutation?

Commonly, these sections can go at the beginning of the essay (after the introduction), or at the end of the essay (before the conclusion). Let's put it at the beginning. Now our essay looks like this:

Counter-argument Paragraph

- Dishonest/lazy people might work less because no one is watching

Refutation/Response Paragraph

- Study: Productivity increased by 14%

- (+ other details)

Body Paragraph 3

- Topic Sentence : In addition, people who work from home have improved well-being .

Body Paragraph 4

The outline is stronger now because it includes the counter-argument and refutation. Note that the essay still needs more details and research to become more convincing.

Working from home may increase productivity.

Extra Advice on Argumentative Essays

It's not a compare and contrast essay.

An argumentative essay focuses on one topic (e.g. cats) and argues for or against it. An argumentative essay should not have two topics (e.g. cats vs dogs). When you compare two ideas, you are writing a compare and contrast essay. An argumentative essay has one topic (cats). If you are FOR cats as pets, a simplistic outline for an argumentative essay could look something like this:

- Thesis: Cats are the best pet.

- are unloving

- cause allergy issues

- This is a benefit > Many working people do not have time for a needy pet

- If you have an allergy, do not buy a cat.

- But for most people (without allergies), cats are great

- Supporting Details

Use Language in Counter-Argument That Shows Its Not Your Position

The counter-argument is not your position. To make this clear, use language such as this in your counter-argument:

- Opponents might argue that cats are unloving.

- People who dislike cats would argue that cats are unloving.

- Critics of cats could argue that cats are unloving.

- It could be argued that cats are unloving.

These underlined phrases make it clear that you are presenting someone else's argument , not your own.

Choose the Side with the Strongest Support

Do not choose your side based on your own personal opinion. Instead, do some research and learn the truth about the topic. After you have read the arguments for and against, choose the side with the strongest support as your position.

Do Not Include Too Many Counter-arguments

Include the main (two or three) points in the counter-argument. If you include too many points, refuting these points becomes quite difficult.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below.

- Matthew Barton / Creator of Englishcurrent.com

Additional Resources :

- Writing a Counter-Argument & Refutation (Richland College)

- Language for Counter-Argument and Refutation Paragraphs (Brown's Student Learning Tools)

EnglishCurrent is happily hosted on Dreamhost . If you found this page helpful, consider a donation to our hosting bill to show your support!

24 comments on “ Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation ”

Thank you professor. It is really helpful.

Can you also put the counter argument in the third paragraph

It depends on what your instructor wants. Generally, a good argumentative essay needs to have a counter-argument and refutation somewhere. Most teachers will probably let you put them anywhere (e.g. in the start, middle, or end) and be happy as long as they are present. But ask your teacher to be sure.

Thank you for the information Professor

how could I address a counter argument for “plastic bags and its consumption should be banned”?

For what reasons do they say they should be banned? You need to address the reasons themselves and show that these reasons are invalid/weak.

Thank you for this useful article. I understand very well.