One Hundred Years of Solitude

By gabriel garcía márquez.

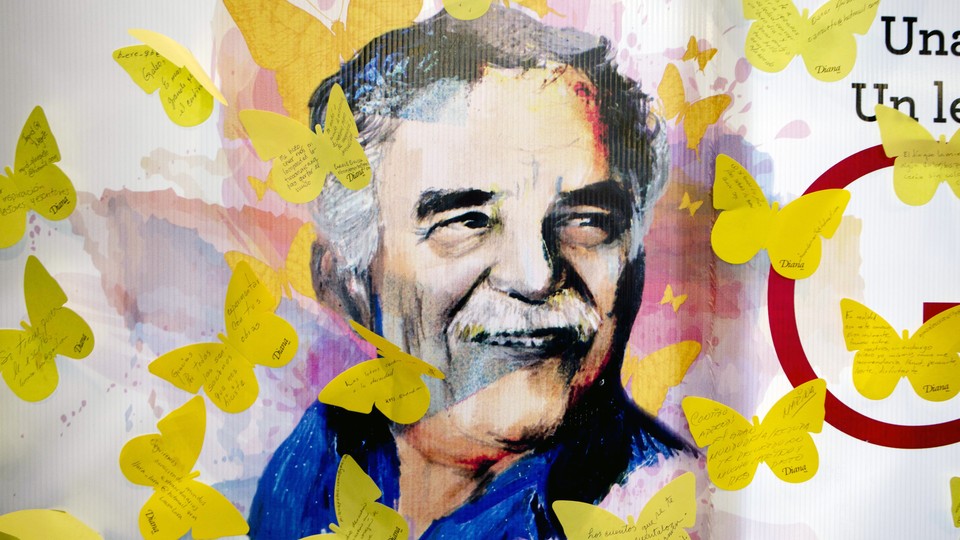

In 'One Hundred Years of Solitude,' Gabriel García Márquez's style of prose is composed of magical realism wherein the mundane is made to be extraordinary and the extraordinary is made to be mundane.

Article written by Charles Asoluka

Degree in Computer Engineering. Passed TOEFL Exam. Seasoned literary critic.

‘ One Hundred Years of Solitude ‘ is a captivating story that follows the lives of the Buendía family for six generations in the small town of Macondo.

Style of Prose

The most notable style of Márquez’s prose is his use of magical realism. This book uses magic realism for two key reasons. It provides background on the Columbian culture that the narrative is based on and challenges us to consider how silly our daily lives are. The residents of Macondo are unconcerned about the supernatural because they come into contact with it regularly. This casual response makes it simple for the reader to believe the weird occurrences that the residents of Macondo refer to as reality.

Márquez’s approach to magic realism also includes using many numerical facts. This addition gives imaginary events a more authentic and realistic description. However, in making these fantastical events believable, it provokes one to question the absurdity of our everyday lives, as the situations which Márquez presents us with are the only exaggeration of what we face in our daily lives.

The Role of Memory and Forgetfulness in One Hundred Years of Solitude

Márquez employed the concept of both remembrance and amnesia in the plot of the ‘ One Hundred Years of Solitude ‘. Rebeca seems to have an overabundance of memory recall while Colonel Aureliano Buendía seems to be an amnesiac, living for the present every day. This contrast helps the reader illustrate the role of history in the repetition of past mistakes l, or the lack thereof.

The Buendías clan’s two afflictions are nostalgia and amnesia, the former of which binds its victims to the past and the latter of which imprisons them in the present. As a result of their condition, the Buendías are destined to keep going through the same cycles until they consume themselves and are unable to advance into the future.

The Naming Conventions of the Buendía family

The Buendía family seems to have a practice of giving their offspring similar names to their predecessors, making it somewhat difficult to follow the character arc of succeeding Buendía members. Nonetheless, Márquez uses this to emphasize the tendency of the offspring to repeat the mistakes of their ancestors.

Márquez’s Use of Symbolism in One Hundred Years of Solitude

Certain oddities and mundane activities or objects in Macondo, seem to have much deeper tones that meet a cursory glance. Márquez plants these subtle cues throughout the book — an Easter egg of sorts.

The significance of Colonel Aureliano Buendía’s tens of thousands of miniature goldfish changes throughout time. These fish initially stand in for Aureliano’s creative temperament and, by extension, the temperament of all Aurelianos. But soon they become more significant, indicating how Aureliano has impacted the globe.

We can also see this symbolism in the train that passes through Macondo. The train symbolizes Macondo’s entry into the modern era. This tragic turn results in the establishment of a banana plantation and the subsequent massacre of 3,000 employees. The train also symbolizes the time when Macondo was most closely connected to the outside world. After the banana plantations are shut down, the railroad deteriorates and the train no longer even makes stops at Macondo.

Lastly, The English dictionary that Meme receives from her American acquaintance first serves as a metaphor for how the American plantation owners are assuming control of Macondo. The foreigners’ invasion of Macondo’s culture is made clear when Meme, a descendant of the town’s founders, starts learning English.

Recurring Themes in One Hundred Years of Solitude

Márquez seeks to emphasize certain aspects of the story by subtly repeating them in various ways. For example, the parallels between the genealogy of the Buendía family and the creation of Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden.

The origin of Macondo and its first Edenic days of purity are described in the narrative, which continues until its catastrophic end with a purifying flood in the middle. José Arcadio Buendía’s search for knowledge led to his downfall—his loss of sanity. The biblical Adam and Eve, who were banished from Eden after eating from the Tree of Knowledge, are represented by him and his wife, Úrsula Iguarán.

Again, this recurring theme also appears in the coming of the gypsies. They are mostly used as linkages throughout ‘ One Hundred Years of Solitude ‘. They serve as a bridge between events and characters that are opposite or unconnected. A group of traveling gypsies arrives every few years, notably in the early years of Macondo, and transforms the community into something akin to a carnival while presenting the goods they have brought with them.

What characterizes Márquez’s writing style?

Magical realism. This is the bread and butter of this story. Márquez presents the absurd as commonplace, forcing the reader to question the validity of the status quo.

What are the major themes in One Hundred Years of Solitude ?

The circularity of time, solitude, progress and civilization, propriety, sexuality, incest, magic vs. reality. The list goes on but these represent the major themes of the book.

How is One Hundred Years of Solitude different from other works of Márquez?

For one, it remains his most successful book — both commercially and critically — and it popularized the genre of ‘realismo magico’.

Is One Hundred Years of Solitude a good story?

It is a good story with deep philosophical undertones. The eclectic assemblage of characters and the oddities that take place within Macondo, make it a very exciting story.

One Hundred Years of Solitude Review

Book Title: One Hundred Years of Solitude

Book Description: 'One Hundred Years of Solitude' chronicles the life and times of the Buendía family as they struggle to navigate the strange world of Macondo.

Book Author: Gabriel García Márquez

Book Edition: First Edition

Book Format: Hardcover

Publisher - Organization: Editorial Sudamericana

Date published: May 18, 1967

ISBN: 978-84-397-0970-0

Number Of Pages: 488

- Lasting Effect on Reader

‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ chronicles the life and times of the Buendía family as they struggle to navigate the strange world of Macondo.

- The story is entertaining and riveting.

- The prose is clear and relatively easy to understand.

- The themes explored are relevant to our society

- . It has a lot of violence and sex which may make some readers uncomfortable

- The repetition of mistakes by the Buendía family is somewhat disorienting at some point.

Join Our Community for Free!

Exclusive to Members

Create Your Personal Profile

Engage in Forums

Join or Create Groups

Save your favorites, beta access.

About Charles Asoluka

Charles Asoluka is a seasoned content creator with a decade-long experience in professional writing. His works have earned him numerous accolades and top prizes in esteemed writing competitions.

About the Book

Discover literature and connect with others just like yourself!

Start the Conversation. Join the Chat.

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

- Invite this member to groups

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

From the archive, 28 June 1970: One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

England is now certainly the last remaining civilised country in which the extraordinary zest and originality of contemporary Latin American fiction has not been recognised.

At a time when the novel appears to many to have generally burnt itself out, Latin Americans have boisterously resuscitated the genre by presenting sheer original subject matter in a vigorous language and a correspondingly original form.

And of the dozen or so most distinguished recent Latin American novelists the Colombian Gabriel García Márquez has been one of the most impressive, and certainly the most spectacularly successful.

A persistent trait of contemporary Latin American fiction has been the presence in it of a curious strain of fantasy: thus in a story by Julio Cortázar a young man coolly vomits up little rabbits.

One Hundred Years of Solitude has been written with the recent Latin American literature of fantasy so firmly in mind that on one level it operates as parody of and reflection on what has gone before. Writers like Borges, Fuentes, Rulfo, Cortázar and particularly Carpentier are all obliquely alluded to and self-consciously parodied in the novel.

Far from indulging in portentous literary games, however, García Márquez's novel aims helpfully to interpret and illuminate what has gone before, offering an explanation and a context to what often seemed purely gratuitous fantasy.

For One Hundred Years of Solitude demonstrates the extent to which the fragile distinction between reality and fantasy depends on the context and assumptions of time and place.

Thus in so remote and improbable a backwater as the swampy village of Macondo which the novel describes, the lunatic ravings of the mad priest who announces the arrival of the Wandering Jew, and the sombre visitations of the ghosts of departed friends, are far more real than such magical novelties as ice, magnets, trains, films and telephones.

And after trains and film shows are introduced to Macondo who can be surprised when the village is subjected to a rain of yellow flowers that covers the streets like a vast carpet, or when a girl is conferred the privilege of assumption, like the Blessed Virgin Mary?

The villagers are far more astonished to find in the cinema that 'a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears of affliction had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one.'

There is no agreement among the inhabitants of Macondo on the exact location of the borderline between fantasy and reality. Yet not even Macondo's most obsessed lunatics are so arbitrary in their deployment of fantasy as the Colombian Government and its ally, American capital.

Thus a strike in a banana plantation that an American company establishes in Macondo is discouraged by the company lawyers' assertion that its workers simply do not exist: 'The banana company did not have, never had had, and never would have any workers in its service because they were all hired on a temporary and occasional basis.'

When the workers finally do strike they are all shot and their bodies are secretly whisked away from Macondo by train at night. Yet a solitary surviving witness of the incident is not able to convince anyone that the slaughter ever occurred, and future generations of Colombian children are to read in their school textbooks not only that there was no slaughter, but indeed that there was never even a banana plantation in Macondo.

Many of the ingredients of contemporary Latin American fiction are packed into this novel. As in other novels, particularly in Carpentier, a savage nature voraciously devours civilisation if it is riot hectically kept at bay; the cult of male virility is fervently, if periodically and humorously, sustained; and as in many Latin American novels, human events are seen ultimately to unfold not progressively but cyclically.

Thus we see Macondo go through laborious alternate cycles of prosperity and decay before finally being swept into the swamp by a cyclone.

All human activity may indeed seem fleeting and cyclical in a continent ravaged by earthquakes, floods, droughts and cyclones. One would anyway not expect a linear view of history to emanate from the imagination of a continent notorious for its inability to achieve significant development.

One Hundred Years of Solitude tells the story of six generations of the Buendia family, the leading family of Macondo, all of whose males are called Jose Arcadio or Aureliano. Their story is a story of endless repetition, of eternal return.

May it, finally, be hoped that this enthralling, exceedingly comic novel will not encounter the lazy indifference that other Latin American novels have met with in this country.

- Gabriel García Márquez

- From the Guardian archive

Gabriel García Márquez, Nobel laureate writer, dies aged 87

Gabriel García Márquez: new extract hints at writer's 'last legacy'

Gabriel García Márquez memorial held

Gabriel García Márquez: 'The greatest Colombian who ever lived'

Latin America reacts to death of literary colossus Gabriel García Márquez

Martin rowson on the death of gabriel garcía márquez – cartoon.

Like Joyce, García Márquez gave us a light to follow into the unknown

Gabriel García Márquez obituary

Gabriel garcía márquez tributes celebrate life and work of literary giant, gabriel garcía márquez death: colombia declares three days of mourning – video, comments (…), most viewed.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

by Gabriel García Márquez & illustrated by Gregory Rabassa by Gabriel Garcia Marquez ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 25, 1969

Those who pass time with the Señor will find this a luxuriant, splendid and spirited conception.

Those (guessably not the general reader) who do not find the labyrinthine configurations of Señor Garcia-Marquez's mighty myth impregnable, and at times interminable, will be rewarded by this story of one hundred years and six generations in the peaceful, primal and ageless world of Macondo.

This is where his earlier No One Writes to the Colonel and Other Stories (1968) took place and it also features the same Buendia clan and its Colonel, a figure of dauntless energy and pride and stamina who carries on 32 small wars and fathers 17 sons by 17 wives. The Buendias are, for more direct purposes of identification, deliberately inseparable by name (and impulse—incest abounds) in spite of the helpful family tree frontispiece. At a rough count there are four Arcadios from the sire Jose Arcadio and six Aurelianos, including a pair of twins. Perhaps it does not matter since they all share to a degree the stubborn simplicity and outsized contours of comic folk characters. But if Senor Garcia-Marquez' book is fable, it is also satire with some of the fanciful giantism of earlier proponents (cf. the sections on war or government and the finally perceived "emptiness' of the former). For a time the Buendias remain untouched in their innocent world and are stunningly surprised by the artifacts of civilization which reach them—ice or false teeth. And even though they are afraid of a horrible precedent (a child born with a pig's tail) they pursue their closely inbred ways. But the incursions from elsewhere and above persist: there's the early plague of insomnia to the later four year, eleven month, two day rain. In the beginning so full of life, the Buendias give way to death and dispersion, and the last scenes of great-great-great-grandmother Ursula, living in the somnolent margins of memory, have great pathos. "Time passes. That's how it goes, but not so much" is a byword of the Buendias.

Pub Date: Feb. 25, 1969

ISBN: 006112009X

Page Count: 417

Publisher: Harper & Row

Review Posted Online: Sept. 30, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 1969

FANTASY | EPIC FANTASY | GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY

Share your opinion of this book

More by Gabriel García Márquez

BOOK REVIEW

by Gabriel García Márquez ; translated by Anne McLean

by Gabriel García Márquez edited by Cristóbal Pera translated by Anne McLean

by Gabriel García Márquez translated by Edith Grossman

More About This Book

SEEN & HEARD

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

New York Times Bestseller

by Max Brooks ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 16, 2020

A tasty, if not always tasteful, tale of supernatural mayhem that fans of King and Crichton alike will enjoy.

Are we not men? We are—well, ask Bigfoot, as Brooks does in this delightful yarn, following on his bestseller World War Z (2006).

A zombie apocalypse is one thing. A volcanic eruption is quite another, for, as the journalist who does a framing voice-over narration for Brooks’ latest puts it, when Mount Rainier popped its cork, “it was the psychological aspect, the hyperbole-fueled hysteria that had ended up killing the most people.” Maybe, but the sasquatches whom the volcano displaced contributed to the statistics, too, if only out of self-defense. Brooks places the epicenter of the Bigfoot war in a high-tech hideaway populated by the kind of people you might find in a Jurassic Park franchise: the schmo who doesn’t know how to do much of anything but tries anyway, the well-intentioned bleeding heart, the know-it-all intellectual who turns out to know the wrong things, the immigrant with a tough backstory and an instinct for survival. Indeed, the novel does double duty as a survival manual, packed full of good advice—for instance, try not to get wounded, for “injury turns you from a giver to a taker. Taking up our resources, our time to care for you.” Brooks presents a case for making room for Bigfoot in the world while peppering his narrative with timely social criticism about bad behavior on the human side of the conflict: The explosion of Rainier might have been better forecast had the president not slashed the budget of the U.S. Geological Survey, leading to “immediate suspension of the National Volcano Early Warning System,” and there’s always someone around looking to monetize the natural disaster and the sasquatch-y onslaught that follows. Brooks is a pro at building suspense even if it plays out in some rather spectacularly yucky episodes, one involving a short spear that takes its name from “the sucking sound of pulling it out of the dead man’s heart and lungs.” Grossness aside, it puts you right there on the scene.

Pub Date: June 16, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-9848-2678-7

Page Count: 304

Publisher: Del Rey/Ballantine

Review Posted Online: Feb. 9, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2020

GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY | GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE | SCIENCE FICTION

More by Max Brooks

by Max Brooks

BOOK TO SCREEN

DARK MATTER

by Blake Crouch ‧ RELEASE DATE: July 26, 2016

Suspenseful, frightening, and sometimes poignant—provided the reader has a generously willing suspension of disbelief.

A man walks out of a bar and his life becomes a kaleidoscope of altered states in this science-fiction thriller.

Crouch opens on a family in a warm, resonant domestic moment with three well-developed characters. At home in Chicago’s Logan Square, Jason Dessen dices an onion while his wife, Daniela, sips wine and chats on the phone. Their son, Charlie, an appealing 15-year-old, sketches on a pad. Still, an undertone of regret hovers over the couple, a preoccupation with roads not taken, a theme the book will literally explore, in multifarious ways. To start, both Jason and Daniela abandoned careers that might have soared, Jason as a physicist, Daniela as an artist. When Charlie was born, he suffered a major illness. Jason was forced to abandon promising research to teach undergraduates at a small college. Daniela turned from having gallery shows to teaching private art lessons to middle school students. On this bracing October evening, Jason visits a local bar to pay homage to Ryan Holder, a former college roommate who just received a major award for his work in neuroscience, an honor that rankles Jason, who, Ryan says, gave up on his career. Smarting from the comment, Jason suffers “a sucker punch” as he heads home that leaves him “standing on the precipice.” From behind Jason, a man with a “ghost white” face, “red, pursed lips," and "horrifying eyes” points a gun at Jason and forces him to drive an SUV, following preset navigational directions. At their destination, the abductor forces Jason to strip naked, beats him, then leads him into a vast, abandoned power plant. Here, Jason meets men and women who insist they want to help him. Attempting to escape, Jason opens a door that leads him into a series of dark, strange, yet eerily familiar encounters that sometimes strain credibility, especially in the tale's final moments.

Pub Date: July 26, 2016

ISBN: 978-1-101-90422-0

Page Count: 352

Publisher: Crown

Review Posted Online: May 3, 2016

Kirkus Reviews Issue: May 15, 2016

GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY | GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE | SCIENCE FICTION | THRILLER | GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION | TECHNICAL & MEDICAL THRILLER

More by Blake Crouch

by Blake Crouch

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

- Non-Fiction

- Author’s Corner

- Reader’s Corner

- Writing Guide

- Book Marketing Services

- Write for us

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Title: One Hundred Years of Solitude

Author: Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Publisher: Editorial Sudamericana, Harper & Row (US) Jonathan Cape (UK)

Genre: Magical Realism, Historical Fiction, Classic Literature

First Publication: 1967

Language: Originally published in Spanish, Translated in English by Gregory Rabassa

Major Characters: Úrsula Iguarán, Remedios Moscote, Remedios, la bella, Fernanda del Carpio, Aureliano Buendía, José Arcadio Buendía, Amaranta Buendía, Amaranta Úrsula Buendía, Aureliano Babilonia, José Arcadio Segundo, Aureliano Segundo, Aureliano José

Theme: The Circularity of Time, Solitude, Progress and Civilization, Magic vs. Reality,

Setting: Macondo, Colombia

Narrator: Third-person omniscient

Book Summary: One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

The novel One Hundred Years of Solitude is an absolute master piece. It manages to capture the various phases and glories of the human history. The book has had a major impact on young minds that have taken up literature as a subject. The book is engaging and intense that reminiscences of how history repeats itself with the collapse and creation of a new Macondo within a span of a century.

The fall and rise of the Buendia family is captured in the backdrop of all the strife that Latin American societies have witnessed. In this novel one will come across this family name spreading out over seven generations.

The book was originally written in Spanish but has been translated into thirty seven languages and till date has sold over thirty million copies.

The theme of this book is about two families that witness various stages of life over the period of a century. How the protagonist try to come to grips with their past and how this obsessiveness brings about the doom of the family is captured in the novel.

In this book Macondo portrays the new world of United Sates, which appeared more like the Promised Land to so many at one time. But over the course of history it came to be accepted as another illusion.

The book can be defined as the fine work of a master writer, about work realism. In his imaginary place metaphors and beliefs have become ordinary facts and life has become most uncertain.

Book Review: One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

One Hundred Years of Solitude is considered by many as Marquez’s masterpiece and that alone says a lot- after all the man won a Nobel Prize . The novel tells the story of Macondo, a fictional town in Latin America, through the history of the Buendia family. The Buendias, generation after generation witnessed the rise, the glory and the fall of the mythical town they called home. In their joys and their sorrows, in their fears and their passions, one sees all of humankind, in all of her tragicomical glory. And in the history and myths of Macondo, the reader sees all of Latin America.

Jose Arcadio Buendia at age 19 moves on looking for greener pastures (actually, the blue sea) with some of his hometown citizens, who have chosen to follow him. He settles down in a spot which feels right and so begins a South American (Colombia) community which becomes the town of Macondo, a village of 20 adobe houses. It rises from the banks of a stony river, a “ land that no one had promised them. ”

“He really had been through death, but he had returned because he could not bear the solitude.”

Jose Arcadio had killed a man who insulted Jose because Jose’s new bride, Ursula, remained a virgin a year after their wedding. She was fearful of producing children with birth defects since the people of their original home village had interbred for centuries. It was possible they were closer than the cousins they believed they were. After Jose kills the man who insulted his virility, he goes home and impregnates Ursula, after which, they pack up and seek their future somewhere else.

With a small number of farm animals, which Ursula uses to grow food, and Jose’s peasant genius for handyman engineering and a restless curiosity for all things alchemical, together they eke out a life for themselves in a brand new village and hold back the jungle – which initially is very difficult. They are almost entirely oblivious of the outside world except for occasional visitors, which include fairground caravan gypsies who bring mystical wonder, willing to make the weeks-long trek to the little isolated town. It will be decades before roads and railroads permit the travel of government soldiers and banana corporations to invade the little community, bringing new blood along with shed blood.

“Wherever they might be they always remember that the past was a lie, that memory has no return, that every spring gone by could never be recovered, and that the wildest and most tenacious love was an ephemeral truth in the end.”

Five generations and a century later, Macondo and its founding family is struggling under a weight of decrepit devolution and decay. But oh, gentle reader, what an extraordinary ride the ordinary standard lives of common ‘simple’ people can be to explore, especially if ingrown and idiosyncratic, even if unintentionally overblown and blowzy as only an isolated hothouse can be! By the last page, all of the ordinary perfidies, wonders, delusions and magic of human loves and passions possible since the beginning of humanity has been revealed to us readers, if not the individuals of this family. The deceptively pedantic pen of a literary genius, the ‘wash, rinse, repeat’ cycle he delightedly exposes, would amuse the Greek muses themselves. He makes the false promise of human evolution painfully clear.

History, technology, war and politics touch the growing, then shrinking, town, warping and weaving the life of small town people into new paths which, mysteriously, show themselves eventually to be amazingly circular instead of moving forward. Each generation begins anew, or at least, they each believe themselves to be fresh and original, and even sometimes solely unloved or unlucky, although each feels shackled by being named after fathers, mothers, aunts and uncles previously born, honorifics passed down like ancient artifacts which the parents, perhaps, hoping unconsciously, that the next generation will accomplish more and better things with the family names. Alas! More than names are passed down! Bodies seem all alike in the darkness.

“Death really did not matter to him but life did, and therefore the sensation he felt when they gave their decision was not a feeling of fear but of nostalgia.”

However, the talented Marquez has us laughing or feeling shocked while we gawp at the bizarre antics of the Buendia generations – until you remember a similar story about your relatives that came from the lips of your own grandmother or stepmother – if she dared tell it.

I admit the book is difficult. Five generations of related siblings, and mothers and fathers who all carry the same names, who have similar adventures over and over, for many hundreds of pages in a stream of unbroken sentences without many paragraphs, dense with meaningful, but not known to the character, repetitive activities which over time show themselves to be ultimately meaningless, and tons of numinous magic, ghosts, clairvoyance, precognition, strangely prescient and revealing dreams – all become like mist above an endlessly flowing river.

“The secret of a good old age is simply an honorable pact with solitude.”

Rivers are notorious for their constant change of moving water sparkling past our dazed eyes, promising us a ride to unknown adventures, soothing and exciting us at the same moment, rich with metaphorical and metaphysical meaning for us creatures of stardust and desire – but it’s only water, after all.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is a story about what it means to be a human being, about the good as well as the bad parts. Love, lust and joy are eternally intertwined with pain, failure and the avarice of death. While reading, you will find yourself laughing out loud as well as mourning in silence, because Marquez manages to capture perfectly every aspect of the human heart and his characters feel real, even when their stories seem quite over-the- top. But that is after all what magical realism is about- making the reader believe that a man can be chased by yellow butterflies wherever he may go, that magic carpets not only exist, but are hardly more remarkable than a huge chunk of ice, and that beautiful girls sometimes do ascent to heavens before their families’ hardly surprised eyes.

“Thus they went on living in a reality that was slipping away, momentarily captured by words, but which would escape irremediably when they forgot the values of the written letters.”

Gabriel García Márquez is one of the most gifted writers I’ve come across. His stories come to life in front of the reader. He hardly writes books; he creates a work of art, he paints pictures but instead of brushes he uses words. Sometimes he can be a bit overly dramatic , and that is the reason why I never feel one hundred percent connected with any of his characters, but the enjoyment of reading his books never ceases.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is not the tale of the forlorn Colonel Aureliano Buendia, who organised thirty-two uprisings and lost each one of them, as well as his heart and feelings. Neither is it the story of Ursula Buendia who witnessed her town’s glory and decay, as well as her family’s. It’s not a story about the life of Remedios, for whom men died nor about the struggles of Aureliano Segundo who married the most beautiful woman in the world only to realise that he would never love anyone more than his mistress. This is an accounting of the history of the human race , of all the time that was and that will be- because one thing is certain; time is moving in a circle.

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Sign me up for the newsletter!

Readers also enjoyed

Legends & lattes by travis baldree, the man who died twice by richard osman, the after life meddlers club by thomas smith, the familiar by leigh bardugo, book lovers by emily henry, popular stories, one day, life will change by saranya umakanthan, most famous fictional detectives from literature, the complete list of the booker prize winner books, book marketing and promotion services.

We provide genuine and custom-tailored book marketing services and promotion strategies. Our services include book reviews and social media promotion across all possible platforms, which will help you in showcasing the books, sample chapters, author interviews, posters, banners, and other promotional materials. In addition to book reviews and author interviews, we also provide social media campaigning in the form of contests, events, quizzes, and giveaways, as well as sharing graphics and book covers. Our book marketing services are very efficient, and we provide them at the most competitive price.

The Book Marketing and Promotion Plan that we provide covers a variety of different services. You have the option of either choosing the whole plan or customizing it by selecting and combining one or more of the services that we provide. The following is a list of the services that we provide for the marketing and promotion of books.

Book Reviews

Book Reviews have direct impact on readers while they are choosing their next book to read. When they are purchasing book, most readers prefer the books with good reviews. We’ll review your book and post reviews on Amazon, Flipkart, Goodreads and on our Blogs and social-media channels.

Author Interviews

We’ll interview the author and post those questions and answers on blogs and social medias so that readers get to know about author and his book. This will make author famous along with his book among the reading community.

Social Media Promotion

We have more than 170K followers on our social media channels who are interested in books and reading. We’ll create and publish different posts about book and author on our social media platforms.

Social Media Set up

Social Media is a significant tool to reaching out your readers and make them aware of your work. We’ll help you to setup and manage various social media profiles and fan pages for your book.

We’ll provide you our social media marketing guide, using which you may take advantage of these social media platforms to create and engage your fan base.

Website Creation

One of the most effective and long-term strategies to increase your book sales is to create your own website. Author website is must have tool for authors today and it doesn’t just help you to promote book but also helps you to engage with your potential readers. Our full featured author website, with blog, social media integration and other cool features, is the best marketing tool you can have. You can list each of your titles and link them to buy from various online stores.

Google / Facebook / Youtube Adverts

We can help you in creating ad on Google, Facebook and Youtube to reach your target audience using specific keywords and categories relevant to your book.

With our help you can narrow down your ads to the exact target audience for your book.

For more details mail us at [email protected]

The Bookish Elf is your single, trusted, daily source for all the news, ideas and richness of literary life. The Bookish Elf is a site you can rely on for book reviews, author interviews, book recommendations, and all things books. Contact us: [email protected]

Quick Links

- Privacy Policy

Recent Posts

How One Hundred Years of Solitude Became a Classic

When Gabriel García Márquez’s most famous novel was published 50 years ago, it faced a difficult publishing climate and baffled reviews.

In 1967, Sudamericana Press published One Hundred Years of Solitude ( Cien años de soledad ), a novel written by a little known Colombian author named Gabriel García Márquez. Neither the writer nor the publisher expected much of the book. They knew, as the publishing giant Alfred A. Knopf once put it, that “many a novel is dead the day it is published.” Unexpectedly, One Hundred Years of Solitude went on to sell over 45 million copies, solidified its stature as a literary classic, and garnered García Márquez fame and acclaim as one of the greatest Spanish-language writers in history.

Fifty years after the book’s publication, it may be tempting to believe its success was as inevitable as the fate of the Buendía family at the story’s center. Over the course of a century, their town of Macondo was the scene of natural catastrophes, civil wars, and magical events; it was ultimately destroyed after the last Buendía was born with a pig’s tail, as prophesied by a manuscript that generations of Buendías tried to decipher. But in the 1960s, One Hundred Years of Solitude was not immediately recognized as the Bible of the style now known as magical realism, which presents fantastic events as mundane situations. Nor did critics agree that the story was really groundbreaking. To fully appreciate the novel’s longevity, artistry, and global resonance, it is essential to examine the unlikely confluence of factors that helped it overcome a difficult publishing climate and the author’s relative anonymity at the time.

In 1965, the Argentine Sudamericana Press was a leading publisher of contemporary Latin American literature. Its acquisitions editor, in search of new talent, cold-called García Márquez to publish some of his work. The writer replied with enthusiasm that he was working on One Hundred Years of Solitude, “a very long and very complex novel in which I have placed my best illusions.” Two and a half months before the novel’s release in 1967, García Márquez’s enthusiasm turned into fear. After mistaking an episode of nervous arrhythmia for a heart attack, he confessed in a letter to a friend, “I am very scared.” What troubled him was the fate of his novel; he knew it could die upon its release. His fear was based on a harsh reality of the publishing industry for rising authors: poor sales. García Márquez’s previous four books had sold fewer than 2,500 copies in total.

Recommended Reading

The Origins of Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Magic Realism

The Subtle Radicalism of Julio Cortázar's Berkeley Lectures

A Lesson for Ravens: Don’t Eat the Tortoises

The best that could happen to One Hundred Years of Solitude was to follow a path similar to the books released in the 1960s as part of the literary movement known as la nueva novela latinoamericana . Success as a new Latin American novel would mean selling its modest first edition of 8,000 copies in a region with 250 million people. Good regional sales would attract a mainstream publisher in Spain that would then import and publish the novel. International recognition would follow with translations into English, French, German, and Italian. To hit the jackpot in 1967 was to also receive one of the coveted literary awards of the Spanish language: the Biblioteca Breve, Rómulo Gallegos, Casa de las Américas, and Formentor.

This was the path taken by new Latin American novels of the 1960s such as Explosion in a Cathedral by Alejo Carpentier, The Time of the Hero by Mario Vargas Llosa, Hopscotch by Julio Cortázar, and The Death of Artemio Cruz by Carlos Fuentes. One Hundred Years of Solitude , of course, eclipsed these works on multiple fronts. Published in 44 languages , it remains the most translated literary work in Spanish after Don Quixote , and a survey among international writers ranks it as the novel that has most shaped world literature over the past three decades.

And yet it would be wrong to credit One Hundred Years of Solitude with starting a literary revolution in Latin America and beyond. Sudamericana published it when the new Latin American novel, by then popularly called the boom latinoamericano , had reached its peak in worldwide sales and influence. From 1961 onward, like a revived Homer, the almost blind Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges toured the planet as a literary celebrity. Following in his footsteps were rising stars like José Donoso, Cortázar, Vargas Llosa, and Fuentes. The international triumph of the Latin American Boom came when the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1967. One Hundred Years of Solitude could not have been published in a better year for the new Latin American novel. Until then, García Márquez and his work were practically invisible.

In the decades before it reached its zenith, the new Latin American novel vied for attention alongside other literary trends in the region, Spain, and internationally. Its primary competition in Latin America was indigenismo , which wanted to give voice to indigenous peoples and was supported by many writers from the 1920s onward, including a young Asturias and José María Arguedas, who wrote in Spanish and Quechua, a native language of the Andes.

In Spain during the 1950s and 1960s, writers embraced social realism, a style characterized by terse stories of tragic characters at the mercy of dire social conditions. Camilo José Cela and Miguel Delibes were among its key proponents. Latin Americans wanting a literary career in Spain had to comply with this style, one example being a young Vargas Llosa living in Madrid, where he first wrote social-realist short stories.

Internationally, Latin American writers saw themselves competing with the French nouveau roman or “new novel.” Supporters, including Jean-Paul Sartre, praised it as the “anti-novel.” For them, the goal of literature was not narrative storytelling, but to serve as a laboratory for stylistic experiments. The most astonishing of such experiments was George Perec’s 1969 novel A Void , written without ever using the letter “e,” the most common in the French language.

In 1967, the book market was finally ready, it seemed, for One Hundred Years of Solitude . By then, mainstream Latin American writers had grown tired of indigenismo , a style used by “provincials of folk obedience,” as Cortázar scoffed. A young generation of authors in Spain belittled the stories in social-realist novels as predictable and technically unoriginal. And in France, emerging writers (such as Michel Tournier in his 1967 novel Vendredi ) called for a return to narrative storytelling as the appeal of the noveau roman waned.

Between 1967 and 1969, reviewers argued that One Hundred Years of Solitude overcame the limitations of these styles. Contrary to the localism of indigenismo , reviewers saw One Hundred Years of Solitude as a cosmopolitan story, one that “could correct the path of the modern novel,” according to the Latin American literary critic Ángel Rama. Unlike the succinct language of social realism, the prose of García Márquez was an “atmospheric purifier,” full of poetic and flamboyant language, as the Spanish writer Luis Izquierdo argued. And contrary to the formal experiments of the nouveau roman , his novel returned to “the narrative of imagination,” as the Catalan poet Pere Gimferrer explained. Upon the book’s translation to major languages, international reviewers acknowledged this, too. The Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg forcefully called One Hundred Years of Solitude “an alive novel,” assuaging contemporary fears that the form was in crisis.

And yet these and other reviewers also remarked that One Hundred Years of Solitude was not a revolutionary work, but an anachronistic and traditionalist one, whose opening sentence resembled the “Once upon a time” formula of folk tales. And rather than a serious novel, it was a “comic masterpiece,” as an anonymous Times Literary Supplement reviewer wrote in 1967. Early views on this novel were indeed different from the ones that followed. In 1989, Yale literary scholar Harold Bloom solemnly called it “the new Don Quixote ” and the writer Francine Prose confessed in 2013 that “ One Hundred Years of Solitude convinced me to drop out of Harvard graduate school.”

Nowadays scholars, critics, and general readers mainly praise the novel as “the best expression of magical realism.” By 1995, magical realism was seen as making its way into the works of major English-language authors such John Updike and Salman Rushdie and moreover presented as “an inextricable, ineluctable element of human existence,” according to the New York Times literary critic Michiko Kakutani. But in 1967, the term magical realism was uncommon, even in scholarly circles. During One Hundred Years of Solitude ’s first decade or so, to make sense of this “unclassifiable work,” as a reviewer put it, readers opted for labeling it as a mixture of “fantasy and reality,” “a realist novel full of imagination,” “a curious case of mythical realism,” “suprarrealism,”or, as a critic for Le Monde called it, “the marvelous symbolic.”

Now seen as a story that speaks to readers around the world, One Hundred Years of Solitude was originally received as a story about Latin America. The Harvard scholar Robert Kiely called it “a South American Genesis” in his review for the New York Times . Over the years, the novel grew to have “a texture of its own,” to use Updike’s words, and it became less a story about Latin America and more about mankind at large. William Kennedy wrote for the National Observer that it is “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the entire human race.” (Kennedy also interviewed García Márquez for a feature story, “The Yellow Trolley Car in Barcelona, and Other Visions,” published in The Atlantic in 1973.)

Perhaps even more surprisingly, respected writers and publishers were among the many and powerful detractors of this novel. Asturias declared that the text of One Hundred Years of Solitude plagiarized Balzac’s 1834 novel The Quest of the Absolute . The Mexican poet and Nobel recipient, Octavio Paz, called it “watery poetry.” The English writer Anthony Burgess claimed it could not be “compared with the genuinely literary explorations of Borges and [Vladimir] Nabokov.” Spain’s most influential literary publisher in the 1960s, Carlos Barral, not only refused to import the novel for publication, but he also later wrote “it was not the best novel of its time.” Indeed, entrenched criticism helps to make a literary work like One Hundred Years of Solitude more visible to new generations of readers and eventually contributes to its consecration.

With the help of its detractors, too, 50 years later the novel has fully entered popular culture. It continues to be read around the world, by celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey and Shakira, and by politicians such as Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, who called the book “one of my favorites from the time I was young.”

More recently, with the aid of ecologically minded readers and scholars, One Hundred Years of Solitude has unexpectedly gained renewed significance as awareness of climate change increases. After the explosion of the BP drilling rig Deepwater Horizon in 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico (one of the worst accidental environmental catastrophes in history), an environmental-policy advocate referred to the blowout as “tragic realism” and a U.S. journalist called it the “pig’s tail of the Petro-World.” What was the connection with One Hundred Years of Solitude ? The explosion occurred at an oil and gas prospect named Macondo by a group of BP engineers two years earlier, so when Deepwater Horizon blew up, reality caught up with fiction. Some readers and scholars started to claim the spill revealed a prophecy similar to the one hidden in the Buendías manuscript: a warning about the dangers of humans’ destruction of nature.

García Márquez lived to see the name of Macondo become part of a significant, if horrifying, part of earth’s geological history, but not to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his masterpiece: He passed away in 2014. But the anniversary of his best known novel will be celebrated globally. As part of the commemoration, the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, where García Márquez’s archives have been kept since 2015, has opened an online exhibit of unique materials. Among the contents will be the original typescript of the “very long and very complex novel” that did not die but attained immortality the day it was published.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

Blue Marble Review

Literary Journal for Young Writers

Review: One Hundred Years of Solitude

By Christine Baek

Gabriel García Márquez’s Cien Años de Soledad, or One Hundred Years of Solitude , reads more like a history than a novel. Chronicling seven generations of the Buendía family, the narrative acts as a wandering guide, often retracing its steps to breathe new life into past memories before moving forward. This writing style could almost be mistaken as discursive if not for the vibrant cast of characters– explorers, scientists, soldiers, artists– whose variegated trials and errors, loves and losses distract us from the rapid shifts through time, and revitalize the glories and pains of humanity.

In the very first chapter, we are carried from the present as Colonel Aureliano Buendía faces the firing squad, to the past where the colonel and his father José Arcadio first touch ice, and then even further back to the founding of Macondo, the Colombian village-home of the Buendías. These bursts of “time-travel” permeate nearly every page and can be as confusing as the repetitious Buendía family names: two Amarantas, four José Arcadios, and over twenty Aurelianos. But the mind-bending effects of these elements are purposeful, forwarding the themes of cyclical fate and the inseparability of past, present, and future. Whether by divine will or by virtue of human nature, each and every generation of the Buendías suffers from Solitude. Family members bearing the same name even share identical causes, which can take the forms of spurned love, violent death, or decrepitude. And with this infallible condition of Solitude comes slow decay, as the once invincible Buendía family descends into ignominy, unable to break free from the inheritance and conditionings of its predecessors.

While One Hundred Years of Solitude can be read solely as a compelling family drama, Márquez’s 448-page book serves as a political commentary on the Latin American elite and the cycles of violence and instability plaguing the continent. Intertwining with the Buendía narrative are military campaigns, political executions, and short-lived dictatorships. In doing so, Márquez retells his own experience as a Colombian living in the crossfire of the banana republics. His unflinching narrative of destruction and decay, therefore, is less of a pessimistic criticism and more of a solemn reflection on humankind. The paradise of Macondo, removed from society and technology, cannot last, Márquez seems to say, because human nature and history deem it so.

And yet One Hundred Years of Solitude reads as uplifting, celebrating the brevity of joy and peace in the midst of war and turmoil. This strange and seemingly irreconcilable dichotomy only cements the nuance of Márquez’s voice and of his belief in our capacity for redemption. As he states in his Nobel Prize Lecture, an echo of the story’s ending:

“It is not yet too late to engage in the creation of the opposite utopia. A new and sweeping utopia of life, where no one will be able to decide for others how they die, where love will prove true and happiness be possible, and where the races condemned to one hundred years of solitude will have, at last and forever, a second opportunity on earth.”

A high school student from the Atlanta suburbs, Christine Baek enjoys writing for The Muse and reading up on history, philosophy, and paleontology.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Why is One Hundred Years of Solitude Eternally Beloved?

At 50 years old, garcía márquez's masterpiece is as important as ever.

Earlier this year I made my first visit to Colombia. During my stay, I became familiar with many of the emblems around which this wonderful nation’s image revolves. There is of course the coffee, some of the best in the world and perhaps primarily known to Americans by the mustachioed Juan Valdez. There are also the ancient indigenous civilizations, whose exquisite artifacts you will see in museums everywhere. Then there is the world-famous painter Fernando Botero, who has adapted his unique style to depict countless national icons, as well as the torture practiced by US soldiers at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison. And most of all, towering over the rest, is Colombia’s most beloved author, Gabriel García Márquez.

There is an oft-told anecdote that cuts to the heart of this writer’s greatness. As he wrote One Hundred Years of Solitude , he would regularly meet with his fellow great Colombian author Álvaro Mutis, updating Mutis on his progress by narrating the latest events from his novel. There was just one problem: none of what García Márquez told Mutis actually occurs in the book. He had effectively made up an entire shadow-novel while in the middle of writing one of the most imaginative and jam-packed books in the history of modern literature. This is a measure of how many competing realities existed in García Márquez’s voracious mind.

I am writing about this author today because his greatest work, One Hundred Years of Solitude , turns 50 years old this year, and I would like to understand why it has had such flabbergasting success. This immense novel is claimed to be an effort to express everything that had influenced García Márquez throughout his childhood. It has been called a latter-day Genesis, the greatest thing in Spanish since Don Quixote (by Pablo Neruda, no less), and unique even by the standards of the colossi of the Boom era. García Márquez wrote it in one rapturous year in Mexico City, supposedly chain-smoking 60 cigarettes a day, secluded and reliant on his wife for the necessities of living. To paraphrase critic Harold Bloom, there is not a single line that does not flood with detail: “It is all story, where everything conceivable and inconceivable is happening at once.”

There are hits, and then there are smash hits, and then there are rocket ships to Mars— One Hundred Years of Solitude would qualify as the last. Estimates of its sales are around 50 million worldwide, which would put it in the range of books like The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes , Lolita , To Kill a Mockingbird , and 1984 . College syllabi can certainly account for some of this figure, but when one considers by just how much García Márquez’s sales dwarf his fellow Boom greats—Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Julio Cortázar—something more than higher education must be called to account. Nor is it easy to explain One Hundred Years of Solitude’s global diffusion: published in at least 44 languages, it is the most translated Spanish-language literary work after Don Quixote .

I think what can be said of this book is that it captured something vital about the historical experience of hundreds of millions of people, not only in Latin America but in other colonized lands as well. Nii Ayikwei Parkes, the award-winning British novelist born to Ghanaian immigrants, has said of the book: “[It] taught the West how to read a reality alternative to their own, which in turn opened the gates for other non-Western writers like myself and other writers from Africa and Asia.” He added that, “Apart from the fact that it’s an amazing book, it taught Western readers tolerance for other perspectives.”

It is indeed true that this book transported something essential about Latin America to far-away places, but I would go farther than that—I would call One Hundred Years of Solitude the most widely read book of Latin American history. I see it as a work in the tradition of ancient foundation stories, such as Virgil’s Aeneid and Homer’s Iliad —or even, while we’re at it, the Bible—a modern version of these works that filtered history through mythic and heroic registers. Reviewing it in 1970 in The New York Times —the year in which North Americans at last received Gregory Rabassa’s “better than the original” translation (to paraphrase García Márquez)—the scholar Robert Kiely said, “the book is a history, not of governments or of formal institutions of the sort which keeps public records, but of a people who, like the earliest descendants of Abraham, are best understood in terms of their relationship to a single family. . . It is a South American Genesis.” Forty-four years later, when García Márquez died, the Times re-upped that opinion in their obituary of the great author, calling One Hundred Years “the defining saga of Latin America’s social and political history.”

The foundation story García Márquez tells is not nearly so heroic as those of Virgil and Homer: rather, his is one of disenchantment and circularity, the slow process of a continent finding its own voice, overcoming efforts to impose a history and trajectory upon it. But though García Márquez would tell history, even incorporate actual historical events into the book, he would not write something that slavishly followed facts. Inspired by Kafka and Joyce, García Márquez believed that in order to speak his truth “it was not necessary to demonstrate facts: it was enough for the author to have written something for it to be true, with no proof other than the power of his talent and the authority of his voice.”

Which is to say, even though One Hundred Years of Solitude springs from very real Colombian politics, it far transcends its political context. The author himself has said that the ideal novel should “perturb not only because of its political and social content, but also because of its power of penetrating reality; and better yet, because of its capacity to turn reality upside down so we can see the other side of it.” And this gets right to the heart of his gift: as the leading exponent of magical realism, One Hundred Years of Solitude is filled with beguiling treasures that captivate a reader’s imagination. As tall as these tales are—a plague of forgetting, or a woman so graceful and beautiful that she ascends right to heaven—they also have an indisputable connection to our prosaic daily lives. This is what literary myth can do that factual history cannot—as García Márquez puts it, this literature turns reality upside down and shows us what hides beneath.

What could be a better foundation myth for a continent deeply fractured along political, historical, and ethnic lines, yet also desirous of articulating a commonly understood experience? Not only that, this story also allowed those on the opposite end—that is, those who had created the conditions for oppression and exploitation—to comprehend and appreciate this shared experience as well. It was through this feat of imagination that García Márquez forged bonds of community. As he said in 1982 while accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature, “poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels . . . we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable. This, my friends, is the crux of our solitude.”

In giving the world new narratives García Márquez helped alleviate that solitude. This is how books like One Hundred Years of Solitude inspire us: they offer new images, new myths, new ideas, and new forms of understanding that cut against those keeping us in division and incomprehension.

Although an author need not be politically motivated to create such art, this is inherently a political act, for politics is made up of narratives—more than that, it depends on them like nothing else—and whenever art creates new, invasive narratives, it contests our politicians’ authority. Let me explain what I mean. When one hears talk of politicians, political campaigns, legislative politicking, and such, never far away is the idea of “controlling the narrative.” Elections are all about defining the narrative you want and hoping it resonates with the voters; then, once in office, you must hang on to your command of the narrative in order to successfully advocate for the policies you want to drum up support for. Imposing your preferred narrative onto the nation is very much essential for transforming your will into law.

According to this notion of politics, narratives are extremely potent things. This is why wealthy and powerful men (it is almost always men) have invested billions of dollars into building media empires meant to put a stranglehold on certain national narratives. Thus the likes of Fox News and Breitbart have convinced millions of people that certain minorities abuse social aid programs, or that the deficit always requires cutting government spending (except when it comes to the military), and that radical Islamists are perpetually on the verge of overrunning our nation. Against these narratives the left plays its own, and if I count myself as a progressive it is primarily because I find the left’s account of the world far more compelling, compassionate, authentic, honest, and productive than the right’s.

It is in the realm of narratives that art can make its most potent interventions into our politics. I do not mean to reduce a book like One Hundred Years of Solitude to a “liberal vs. conservative” framework—even though this book deals to a very large extent with Colombia’s “Thousand Days’ War,” which was precisely a war between Liberals and Conservatives, like any true work of art it defeats such ready-made binaries to show us that the world is immensely more mysterious and complex. And indeed, this must be another measure of García Márquez’s success: that he has given us books that touch us deeply, even if we know virtually nothing of this source material. His novels have altered our narratives even while they resist simple interpretation, growing with society as it ages and remaining contemporary and relevant. To once again quote Bloom, “García Márquez has given contemporary culture, in North America and Europe, as much as in Latin America, one of its double handful of necessary narratives, without which we will understand neither one another nor our own selves.”

In modern history, great art has always shown other ways of seeing the world. It should always remind us that nobody has a monopoly on the truth, and that even the political narratives that we hold to most steadfastly still only capture at best a portion of this world that is always far more complex than our thought and language can say. To experience a towering work like One Hundred Years of Solitude is to be reminded of the humility we should all feel when trying to assert what is true and what is false.

Of course, this is not to say that progressives should not advocate for the world we want with passion and conviction—politics requires just that—it is to say that our compassion and our empathy should always also be close at hand, no matter who we are dealing with. And we should always look to enlarge our world view through books. Even in this age of media over-saturation—when we have film, TV, Facebook, binge-watching, streaming, Twitter, and so many others—I do not believe there is a better medium for conveying challenging, nuanced, original, and important new narratives to our minds. It is precisely these stories that have kept One Hundred Years of Solitude fresh, and that keeps the world reading it.

More Great Latin American Narratives to Discover

Love in a Time of Cholera Gabriel García Márquez (tr. Edith Grossman) * The Passion According to G.H. Clarice Lispector (tr. Idra Novey) * The Invention of Morel by Adolfo Bioy Casares (tr. Ruth L. C. Simms) * Thus Were Their Faces Silvina Ocampo (tr. Daniel Balderston) * Kiss of the Spiderwoman Manuel Puig (tr. Suzanne Jill Levine) * Seeing Red Lina Meruane (tr. Megan McDowell) * Fever Dream Samanta Schweblin (tr. Megan McDowell) * Bonsai Alejandro Zambra (tr. Carolina De Robertis)

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Veronica Esposito

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Everything Will Be Perfect if We Move to the Western Wilderness

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

One Hundred Years of Solitude

Gabriel Garcia Marquez | 4.14 | 1,371,338 ratings and reviews

Ranked #1 in Translated , Ranked #1 in Latin — see more rankings .

Reviews and Recommendations

We've comprehensively compiled reviews of One Hundred Years of Solitude from the world's leading experts.

Barack Obama Former USA President When asked what books he recommended to his 18-year-old daughter Malia, Obama gave the Times a list that included The Naked and the Dead and One Hundred Years of Solitude. “I think some of them were sort of the usual suspects […] I think she hadn’t read yet. Then there were some books that are not on everybody’s reading list these days, but I remembered as being interesting.” Here’s what he included: The Naked and the Dead, Norman Mailer One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez The Golden Notebook, Doris Lessing The Woman Warrior, Maxine Hong Kingston (Source)

Richard Branson Founder/Virgin Group Today is World Book Day, a wonderful opportunity to address this #ChallengeRichard sent in by Mike Gonzalez of New Jersey: Make a list of your top 65 books to read in a lifetime. (Source)

Oprah Winfrey CEO/O Network Brace yourselves—One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez is as steamy, dense and sensual as the jungle that surrounds the surreal town of Macondo! (Source)

Kamal Ravikant Entrepreneur & Author I’m Reading Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, hell of a writer. (Source)

Emi Gal When asked what books he would recommend to young people interested in his career path, mentioned One Hundred Years of Solitude. (Source)

Cal Fussman Cal described why he sometimes gifts Gabriel Garcia Marquez's "One Hundred Years of Solitude" to would-be writers: "If you've never written a book and you're going to tell somebody you want to write a great book, all right. Read this and know what a great book is". (Source)

Leo Babauta Recommends this book

Turtle Bunbury This book put a bit of a sheen on Wilbur [Smith] because it is so beautifully written. I just loved all the different aspects of it. There is such inventive language and concepts, and the whole magical realism thing really appeals to me. There is humour as well, and you don’t get that much humour in old Wilbur to be fair! In this book there are seven generations of a family with a very definite beginning and end. It begins with José Arcadio Buendía, who founds the town of Macondo in the Latin American jungle, and the book follows his family over the next 100 years. Each member of the family... (Source)

Jim Schachter Watching Moulin Rouge and remembering why I decided on first viewing that it was my favorite movie ever. Book-wise, One Hundred Years of Solitude stood up to similar review. Thanks @bazluhrmann (and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.) https://t.co/8HcinqzkWJ (Source)

John King Absolutely. Borges never published, for example, many more than four or five pages at a time, and his narrators tend to navigate that more abstract world of literature and ideas. Whereas what García Márquez does is tell a story of the history and culture of Latin America from the point of view of the ordinary person. He manages to do that through this deadpan narrator who can mix the savagely real with the wonderful, and narrate a family saga which is also a history of Latin America. This book really put Latin American literature on the international map because it is a novel which, while... (Source)

Edith Grossman He’s a delicious man, he says those kind of things all the time. Which takes nothing away from Gregory’s translation, of course. I have read One Hundred Years of Solitude in both Spanish and English, and I was so struck by what Rabassa was able to accomplish that it was the final argument to confirm some changes I made in my own life. I had initially wanted to study baroque poetry in Spanish. I was very enamoured of [Francisco de] Quevedo and [Luis de] Góngora. (Source)

Bill Earner My favorites [novels] are 100 Years of Solitude, All the King's Men, The Last Samurai, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. (Source)

Rankings by Category

One Hundred Years of Solitude is ranked in the following categories:

- #69 in 12th Grade

- #69 in 17-Year-Old

- #69 in 18-Year-Old

- #15 in 20th Century

- #23 in Award-Winning

- #23 in Awarded

- #56 in Beautiful

- #4 in Breakup

- #15 in Bucket List

- #6 in Buzzfeed

- #60 in Class

- #53 in Classic

- #54 in Classical

- #32 in Collection

- #83 in Contemporary

- #98 in Culture

- #47 in Current

- #74 in Entertaining

- #71 in Entertainment

- #52 in Epic

- #10 in Facebook

- #81 in Family

- #34 in Fiction

- #23 in Folio Society

- #75 in Game Changer

- #71 in Gift

- #36 in Gilmore Girls

- #48 in Goodreads

- #19 in Hebrew

- #68 in Humanity

- #71 in Important

- #77 in Intellectual

- #15 in Leather

- #27 in Leather Bound

- #88 in Library

- #54 in Life Changing

- #11 in Literary

- #11 in Literature

- #11 in Loneliness

- #33 in Long

- #1 in Magical Realism

- #43 in Modern

- #13 in Modern Classic

- #26 in Modern Fiction

- #53 in Modernism

- #58 in Most Influential

- #27 in Must-Read

- #15 in Mystical

- #1 in Nobel

- #10 in Novel

- #9 in Oprah

- #19 in Poster

- #7 in Postmodernism

- #24 in Quarantine

- #58 in Recent

- #20 in Roman

- #27 in Saga

- #35 in Soul

- #31 in Spain

- #2 in Spanish

- #37 in Summer

- #73 in Summer Reading

- #4 in Surrealism

- #36 in To-Read

- #27 in Top Ten

- #11 in Vacation

- #32 in Weird

- #13 in World

Similar Books

If you like One Hundred Years of Solitude, check out these similar top-rated books:

Learn: What makes Shortform summaries the best in the world?

Review: One Hundred Years of Solitude

Review Copyright © 2006 Garret Wilson — 28 May 2006 7:12am

“With every event in Gabriel García Márquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude, my anticipation grew, wondering when the climax would be reached, the loose ends tied, the purpose achieved, and the mystery be solved until, reading faster and faster, I reached the end and nothing happened, making me wish I would have taken the time to enjoy each of the intricate, preposterous events along the way.”

Is that the effect Márquez wants to have on his reader? Toward the end of the book, it almost seems so:

It was the last that remained of a past whose annihilation had not taken place because it was still in a process of annihilation, consuming itself from within, ending at every moment but never ending its ending (434).

But I’m not sure that this is his point. I’m not even sure Márquez has a point at all.

When I first started One Hundred Years of Solitude, I was struck by its banality. Those Buendías were to be commended, of course, trekking across the mountains to found the mythical city of Macondo and all, but the sleep of apathy was creeping up on me until the magic carpet floated by and no one notice. Oh, they noticed that it was some new nifty invention, as those gypsies typically brought as they passed through town, but no one realized that it couldn’t really happen. So this must be a tall tale.

But as the story progressed, coasting for a while in the normalcy lane and then revving its engines for a quick spin through some off-the-trail excursion into outlandishness, I expected a rhyme, or a reason; in short, I expected Rushdie. I expected Gabreel and Ganesh and hairs of the prophet, all elaborate metaphors for some statement about politics, religion, or life in general. But the promising drops of absurdity never congealed into any larger Rushie-like plan; the incredulity-causing opportunities are never used, save perhaps the seventy chamberpots which are finally used by José Arcadio Segundo (337).

If Márquez has no point, he at least has a theme: everyone grows up, does lots of things, but is never really happy until they get old, slow down, and stop caring about doing things, basking in their own inward-looking gaze of solitude. Colonel Aureliano Buendía found solitude working in José Arcadio Buendía’s workshop creating gold fishes which he would sell for gold coins which he would then turn into more gold fishes.

Taciturn, silent, insensible to the new breath of vitality that was shaking the house, Colonel Aureliano Buendía could understand only that the secret of a good old age is simply an honorable pact with solitude. He would get up at five in the morning after a light sleep, have his eternal mug of bitter coffee in the kitchen, shut himself up all day in the workshop, and at four in the afternoon he would go along the porch dragging a stool, not even noticing the fire of the rose bushes or the brightness of the hour or the persistence of Amaranta, whose melancholy made the noise of a boiling pot, which was perfectly perceptible at dusk, and he would sit in the street door as long as the mosquitoes would allow him to (216).

When death visited Amaranta and instructed her to sew a shroud, Amaranta followed the same path to solitude as the sat in silence for days on end, constructing her own burial garment:

It was then that she understood the vicious circle of Colonel Aureliano Buendía’s little gold fishes. The world was reduced to the surface of her skin and her inner self was safe from all bitterness. It pained her not to have had that revelation many years before when it had still been possible to purify memories and reconstruct the universe under a new light and evoke without trembling Pietro Crespi’s smell of lavender at dusk and rescue Rebeca from her slough of misery, not out of hatred or out of love but because of the measureless understanding of solitude (300).

And Úrsula, the longsuffering matriarch, as she neared the end of her life fell into a similar state:

Even though the trembling of her hands was more and more noticeable and the weight of her feet was too much for her, her small figure was never seen in so many places at the same time. She was almost as diligent as when she had the whole weight of the house on her shoulders. Nevertheless, in the impenetrable solitude of decrepitude she had such clairvoyance as she examined the most insignificant happenings in the family that for the first time she saw clearly the truths that her busy life in former times had prevented her from seeing (266).

But even these depressing conclusions of futility seem only haphazard pit stops in Márquez’ mad race with time. The José Arcadios and Aurelianos of the Buendía legacy become a blur that even Márquez appears unable to clarify, even though he repeatedly attempts to distinguish which is which and, in the case of the Segundos, why they might have switched. When the end comes, it comes not with a bang or even a whimper, but with a sigh for the spiraling family circle that, even in fiction, may not have ever existed.

Copyright © 2006 Garret Wilson

The Book Report Network

- Bookreporter

- ReadingGroupGuides

- AuthorsOnTheWeb

Sign up for our newsletters!

Find a Guide