Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2021

Two cases about Hertz claimed top spots in 2021's Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies

Two cases on the uses of debt and equity at Hertz claimed top spots in the CRDT’s (Case Research and Development Team) 2021 top 40 review of cases.

Hertz (A) took the top spot. The case details the financial structure of the rental car company through the end of 2019. Hertz (B), which ranked third in CRDT’s list, describes the company’s struggles during the early part of the COVID pandemic and its eventual need to enter Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

The success of the Hertz cases was unprecedented for the top 40 list. Usually, cases take a number of years to gain popularity, but the Hertz cases claimed top spots in their first year of release. Hertz (A) also became the first ‘cooked’ case to top the annual review, as all of the other winners had been web-based ‘raw’ cases.

Besides introducing students to the complicated financing required to maintain an enormous fleet of cars, the Hertz cases also expanded the diversity of case protagonists. Kathyrn Marinello was the CEO of Hertz during this period and the CFO, Jamere Jackson is black.

Sandwiched between the two Hertz cases, Coffee 2016, a perennial best seller, finished second. “Glory, Glory, Man United!” a case about an English football team’s IPO made a surprise move to number four. Cases on search fund boards, the future of malls, Norway’s Sovereign Wealth fund, Prodigy Finance, the Mayo Clinic, and Cadbury rounded out the top ten.

Other year-end data for 2021 showed:

- Online “raw” case usage remained steady as compared to 2020 with over 35K users from 170 countries and all 50 U.S. states interacting with 196 cases.

- Fifty four percent of raw case users came from outside the U.S..

- The Yale School of Management (SOM) case study directory pages received over 160K page views from 177 countries with approximately a third originating in India followed by the U.S. and the Philippines.

- Twenty-six of the cases in the list are raw cases.

- A third of the cases feature a woman protagonist.

- Orders for Yale SOM case studies increased by almost 50% compared to 2020.

- The top 40 cases were supervised by 19 different Yale SOM faculty members, several supervising multiple cases.

CRDT compiled the Top 40 list by combining data from its case store, Google Analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption.

All of this year’s Top 40 cases are available for purchase from the Yale Management Media store .

And the Top 40 cases studies of 2021 are:

1. Hertz Global Holdings (A): Uses of Debt and Equity

2. Coffee 2016

3. Hertz Global Holdings (B): Uses of Debt and Equity 2020

4. Glory, Glory Man United!

5. Search Fund Company Boards: How CEOs Can Build Boards to Help Them Thrive

6. The Future of Malls: Was Decline Inevitable?

7. Strategy for Norway's Pension Fund Global

8. Prodigy Finance

9. Design at Mayo

10. Cadbury

11. City Hospital Emergency Room

13. Volkswagen

14. Marina Bay Sands

15. Shake Shack IPO

16. Mastercard

17. Netflix

18. Ant Financial

19. AXA: Creating the New CR Metrics

20. IBM Corporate Service Corps

21. Business Leadership in South Africa's 1994 Reforms

22. Alternative Meat Industry

23. Children's Premier

24. Khalil Tawil and Umi (A)

25. Palm Oil 2016

26. Teach For All: Designing a Global Network

27. What's Next? Search Fund Entrepreneurs Reflect on Life After Exit

28. Searching for a Search Fund Structure: A Student Takes a Tour of Various Options

30. Project Sammaan

31. Commonfund ESG

32. Polaroid

33. Connecticut Green Bank 2018: After the Raid

34. FieldFresh Foods

35. The Alibaba Group

36. 360 State Street: Real Options

37. Herman Miller

38. AgBiome

39. Nathan Cummings Foundation

40. Toyota 2010

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

GlobalStrategy →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

To solve big issues like climate change, we need to reframe our problems

Reframing our problems could help yield new solutions to major issues like climate change and gender inequality. Image: Unsplash / @pinewatt

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg

Jonathan wichmann.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Behavioural Sciences is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, behavioural sciences.

- Reframing social and global problems could yield viable solutions to major issues such as climate change and gender inequality.

- Being able to identify patterns in how people tend to frame problems underpins this approach.

- Three such patterns include framing problems to avoid change, to blame individuals instead of the system, and to bypass "messy" realities.

Imagine you own an office building and your tenants are complaining that the elevator is way too slow. What do you do?

Faced with this problem, most people instinctively jump into solution mode. How can we make the elevator faster? Can we upgrade the motor? Tweak the algorithm? Do we need to buy a new elevator?

The speed of the elevator might be the wrong problem to focus on, however. Talk to an experienced landlord and they might offer you a more elegant solution: put up mirrors next to the elevator so people don’t notice the wait. Gazing lovingly at your own reflection tends to have that effect.

The mirror doesn’t make the elevator faster. It solves a different problem – that the wait is annoying.

Solve the right problem

The slow elevator story highlights an important truth, in that the way we frame a problem often determines which solutions we come up with. By shifting the way we see a problem, we can sometimes find better solutions.

Problem framing is of paramount importance when it comes to tackling the many hard challenges our societies face. And yet, we’re not terribly good at it. In a survey of 106 corporate leaders, 87% said their people waste significant resources solving the wrong problems. When we go to the doctor, we know very well that identifying the right problem is key. Too often, we fail to apply the same thinking to social and global problems.

Problem framing is of paramount importance when it comes to tackling the many hard challenges our societies face.

Three common patterns

So, how do we get better at it? One starting point is to recognise that there are often patterns in the way we frame problems. Get better at recognising those patterns, and you can dramatically improve your ability to solve the right problems. Here are three typical patterns:

1. We prefer framings that allow us to avoid change

People tend to frame problems so they don’t have to change their own behaviour. When the lack of women leading companies first became a prominent concern decades ago, it was often framed as a pipeline problem. Many corporate leaders simply assumed that, once there were enough women in junior positions, the C-suite would follow.

That framing allowed companies to carry on as usual for about a generation until time eventually proved the pipeline theory wrong , or at best radically incomplete. The gender balance among senior executives would surely be better by now if companies had not spent a few decades ignoring other explanations for the skewed ratio.

People tend to frame problems so they don’t have to change their own behaviour.

2. We blame individuals and ignore the system

Another pattern is that we tend to frame problems at the level of the individual, overlooking systemic factors.

Climate change is an obvious example. Research shows the majority of your carbon footprint is determined by your socioeconomic status and the shared emissions of the area in which you live. There’s only so much you can do to change this, unless you are willing to engage in a very radical lifestyle change such as living off the grid. In popular culture, however, climate change is mostly framed as an individual choice, for example choosing to fly less or at least buy a carbon offset if you do fly.

Framing climate change as an individual responsibility is not a bad thing. If enough people change, it makes a real difference, at least over time. Research has also suggested that individual action can build momentum for systemic change.

But the framing can also distract us from focusing on systemic issues, including what companies do (or don’t do) to address climate change. Some companies may be using this strategically. For example, it's a little-known fact that oil company BP popularised the idea of a “carbon footprint” as part of a mid-2000s advertising campaign .

Framing can distract us from focusing on systemic issues, including what companies do (or don’t do) to address climate change.

3. We want magic bullets, not messy reality

Most of our social and global problems are multi-causal. The problem-solving scholar Russell L. Ackoff memorably used the term “ messes ” to describe real-world problems. But people often dislike complexity, preferring neat stories with a single, easily-identifiable villain.

Take the case of gun deaths in the US. Advocates for gun ownership often use the “mental health” argument that guns don’t kill people, people do. On the other hand, people who dislike guns often see it as an access problem and call for a ban on all guns. Arguably, both of these framings are as simplistic as they are infeasible.

Contrast this with the approach described by the economist Paul Krugman in a recent New York Times column . He uses the car industry to reframe the gun debate. We fight automobile accidents through a broad suite of different interventions, which allows us to keep using our cars but in a safer way.

This approach calls for a portfolio of reasonable regulations that recognises the political fact that many Americans want to keep their guns. This is a far stretch from the binary "access-or-mental-health" framing and, in our opinion, much more likely to create results.

Problem framing is a critical skill and one that can make a big difference to our shared problems.

How to escape a horrible boss

Problem framing is a critical skill and one that can make a big difference to our shared problems. But that’s not the only reason to get better at it - framing can also be useful in our personal lives.

The creativity scholar Robert Sternberg once told the story of an executive who loved his job but hated his boss. The executive’s contempt for his boss was so strong that he decided to contact a headhunter who said that finding a similar job elsewhere should be easy. The same evening, however, the executive spoke to his wife, who happened to be an expert on reframing.

This led to a better approach. In Sternberg’s words: “He returned to the headhunter and gave the headhunter his boss’s name. The headhunter found a new job for the executive’s boss, which the boss—having no idea of what was going on—accepted. The executive then got his boss’s job.”

It seems we could all do with a little bit of reframing.

Have you read?

What covid-19 taught 10 startups about pivoting, problem solving and tackling the unknown, this is how climate change could impact the global economy, how big is the corporate gender gap, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Emerging Technologies .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

5 ways to make the transition to Generative AI a success for your business

Ana Kreacic and Michael Zeltkevic

May 7, 2024

UK proposal to ban smartphones for kids, and other technology stories you need to know

Robot rock stars, pocket forests, and the battle for chips - Forum podcasts you should hear this month

Robin Pomeroy and Linda Lacina

April 29, 2024

4 steps for the Middle East and North Africa to develop 'intelligent economies'

Maroun Kairouz

The future of learning: How AI is revolutionizing education 4.0

Tanya Milberg

April 28, 2024

Shaping the Future of Learning: The Role of AI in Education 4.0

- Browse Topics

- Executive Committee

- Affiliated Faculty

- Harvard Negotiation Project

- Great Negotiator

- American Secretaries of State Project

- Awards, Grants, and Fellowships

- Negotiation Programs

- Mediation Programs

- One-Day Programs

- In-House Training and Custom Programs

- In-Person Programs

- Online Programs

- Advanced Materials Search

- Contact Information

- The Teaching Negotiation Resource Center Policies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Negotiation Journal

- Harvard Negotiation Law Review

- Working Conference on AI, Technology, and Negotiation

- 40th Anniversary Symposium

- Free Reports and Program Guides

Free Videos

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Event Series

- Our Mission

- Keyword Index

PON – Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School - https://www.pon.harvard.edu

Team-Building Strategies: Building a Winning Team for Your Organization

Discover how to build a winning team and boost your business negotiation results in this free special report, Team Building Strategies for Your Organization, from Harvard Law School.

Top 10 International Business Negotiation Case Studies

International business negotiation case studies offer insights to business negotiators who face challenges in the realm of cross-cultural business negotiation..

By PON Staff — on March 26th, 2024 / International Negotiation

If you engage in international negotiation , you can improve your odds of success by learning from these 10 well-known international business negotiation case studies:

Claim your FREE copy: International Negotiations

Claim your copy of International Negotiations: Cross-Cultural Communication Skills for International Business Executives from the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School.

- Apple’s Apology in China

When Apple CEO Timothy D. Cook apologized to Apple customers in China for problems arising from Apple’s warranty policy, he promised to rectify the issue. In a negotiation research study, Professor William W. Maddux of INSEAD and his colleagues compared reactions to apologies in the United States and in Japan. They discovered that in “collectivist cultures” such as China and Japan, apologies can be particularly effective in repairing broken trust, regardless of whether the person apologizing is to blame. This may be especially true in a cross-cultural business negotiation such as this one.

- Bangladesh Factory-Safety Agreements

In this negotiation case study, an eight-story factory collapsed in Bangladesh, killing an estimated 1,129 people, most of whom were low-wage garment workers manufacturing goods for foreign retailers. Following the tragedy, companies that outsourced their garment production faced public pressure to improve conditions for foreign workers. Labor unions focused their efforts on persuading Swedish “cheap chic” giant H&M to take the lead on safety improvements. This negotiation case study highlights the pros and cons of all-inclusive, diffuse agreements versus targeted, specific agreements.

- The Microsoft-Nokia Deal

Microsoft made the surprising announcement that it was purchasing Finnish mobile handset maker Nokia for $7.2 billion, a merger aimed at building Microsoft’s mobile and smartphone offerings. The merger faced even more complexity after the ink dried on the contract—namely, the challenges of integrating employees from different cultures. International business negotiation case studies such as this one underscore the difficulties that companies face when attempting to negotiate two different identities.

- The Cyprus Crisis

With the economy of the tiny Mediterranean island nation Cyprus near collapse, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), European Central Bank (ECB), and the European Commission teamed up to offer a 10-billion-euro bailout package contingent on Cyprus provisioning a substantial amount of the money through a one-time tax on ordinary Cypriot bank depositors. The move proved extremely unpopular in Cyprus and protests resulted. The nation’s president was left scrambling for a backup plan. The lesson from international business negotiation case studies such as this? Sometimes the best deal you can get may be better than no deal at all.

- Dissent in the European Union

The European Union (EU) held a summit to address the coordination of economic activities and policies among EU member states. German resistance to such a global deal was strong, and pessimism about a unified EU banking system ran high as a result of the EU financial crisis. The conflict reflects the difficulty of forging multiparty agreements during times of stress and crisis.

- North and South Korea Talks Collapse

Negotiations between North Korea and South Korea were supposed to begin in Seoul aimed at lessening tensions between the divided nations. It would have been the highest government dialogue between the two nations in years. Just before negotiations were due to start, however, North Korea complained that it was insulted that the lead negotiator from the South wasn’t higher in status. The conflict escalated, and North Korea ultimately withdrew from the talks. The case highlights the importance of pride and power perceptions in international negotiations.

- Canceled Talks for the U.S. and Russia

Then-U.S. president Barack Obama canceled a scheduled summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin, citing a lack of progress on a variety of negotiations. The announcement came on the heels of Russia’s decision to grant temporary asylum to former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden, who made confidential data on American surveillance programs public. From international business negotiation case studies such as this, we can learn strategic reasons for breaking off ties , if only temporarily, with a counterpart.

- The East China Sea Dispute

In recent years, several nations, including China and Japan, have laid claim to a chain of islands in the East China Sea. China’s creation of an “air defense” zone over the islands led to an international dispute with Japan. International negotiators seeking to resolve complex disputes may gain valuable advice from this negotiation case study, which involves issues of international law as well as perceptions of relative strength or weakness in negotiations.

- An International Deal with Syria

When then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and his Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov, announced a deal to prevent the United States from entering the Syrian War, it was contingent on Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s promise to dismantle his nation’s chemical weapons. Like other real-life negotiation case studies, this one highlights the value of expanding our focus in negotiation.

- A Nuclear Deal with Iran

When the United States and five other world powers announced an interim agreement to temporarily freeze Iran’s nuclear program, the six-month accord, which eventually led to a full-scale agreement in 2015, was designed to give international negotiators time to negotiate a more comprehensive pact that would remove the threat of Iran producing nuclear weapons. As Iranian President Hassan Rouhani insisted that Iran had a sovereign right to enrich uranium, the United States rejected Iran’s claim to having a “right to enrich” but agreed to allow Iran to continue to enrich at a low level, a concession that allowed a deal to emerge.

What international business negotiation case studies in the news have you learned from in recent years?

Related Posts

- The Importance of Relationship Building in China

- A Top International Negotiation Case Study in Business: The Microsoft-Nokia Deal

- India’s Direct Approach to Conflict Resolution

- International Negotiations and Agenda Setting: Controlling the Flow of the Negotiation Process

- Overcoming Cultural Barriers in Negotiations and the Importance of Communication in International Business Deals

No Responses to “Top 10 International Business Negotiation Case Studies”

One response to “top 10 international business negotiation case studies”.

It would be interesting to see a 2017 update on each of these negotiations.

Click here to cancel reply.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Negotiation and Leadership

- Learn More about Negotiation and Leadership

NEGOTIATION MASTER CLASS

- Learn More about Harvard Negotiation Master Class

Negotiation Essentials Online

- Learn More about Negotiation Essentials Online

Beyond the Back Table: Working with People and Organizations to Get to Yes

- Learn More about Beyond the Back Table

Select Your Free Special Report

- Beyond the Back Table September 2024 and February 2025 Program Guide

- Negotiation and Leadership Fall 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Essentials Online (NEO) Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Master Class May 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation and Leadership Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Make the Most of Online Negotiations

- Managing Multiparty Negotiations

- Getting the Deal Done

- Salary Negotiation: How to Negotiate Salary: Learn the Best Techniques to Help You Manage the Most Difficult Salary Negotiations and What You Need to Know When Asking for a Raise

- Overcoming Cultural Barriers in Negotiation: Cross Cultural Communication Techniques and Negotiation Skills From International Business and Diplomacy

Teaching Negotiation Resource Center

- Teaching Materials and Publications

Stay Connected to PON

Preparing for negotiation.

Understanding how to arrange the meeting space is a key aspect of preparing for negotiation. In this video, Professor Guhan Subramanian discusses a real world example of how seating arrangements can influence a negotiator’s success. This discussion was held at the 3 day executive education workshop for senior executives at the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School.

Guhan Subramanian is the Professor of Law and Business at the Harvard Law School and Professor of Business Law at the Harvard Business School.

Articles & Insights

- BATNA Examples—and What You Can Learn from Them

- What is BATNA? How to Find Your Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement

- For Sellers, The Anchoring Effects of a Hidden Price Can Offer Advantages

- Negotiation Examples: How Crisis Negotiators Use Text Messaging

- Taylor Swift: Negotiation Mastermind?

- Individual Differences in Negotiation—and How They Affect Results

- Winner’s Curse: Negotiation Mistakes to Avoid

- Solutions for Avoiding Intercultural Barriers at the Negotiation Table

- Top Negotiation Case Studies in Business: Apple and Dispute Resolution in the Courts

- Sales Negotiation Techniques

- The Pitfalls of Negotiations Over Email

- 3 Types of Conflict and How to Address Them

- Negotiation with Your Children: How to Resolve Family Conflicts

- What is Conflict Resolution, and How Does It Work?

- Conflict Styles and Bargaining Styles

- Crisis Negotiation Skills: The Hostage Negotiator’s Drill

- Police Negotiation Techniques from the NYPD Crisis Negotiations Team

- Famous Negotiations Cases – NBA and the Power of Deadlines at the Bargaining Table

- Negotiating Change During the Covid-19 Pandemic

- AI Negotiation in the News

- When Dealing with Difficult People, Look Inward

- Ethics in Negotiations: How to Deal with Deception at the Bargaining Table

- How to Manage Difficult Staff: Gen Z Edition

- Bargaining in Bad Faith: Dealing with “False Negotiators”

- Managing Difficult Employees, and Those Who Just Seem Difficult

- MESO Negotiation: The Benefits of Making Multiple Equivalent Simultaneous Offers in Business Negotiations

- 7 Tips for Closing the Deal in Negotiations

- How Does Mediation Work in a Lawsuit?

- Dealmaking Secrets from Henry Kissinger

- Writing the Negotiated Agreement

- The Importance of Power in Negotiations: Taylor Swift Shakes it Off

- Settling Out of Court: Negotiating in the Shadow of the Law

- How to Negotiate with Friends and Family

- What is Dispute System Design?

- What are the Three Basic Types of Dispute Resolution? What to Know About Mediation, Arbitration, and Litigation

- Leadership and Decision-Making: Empowering Better Decisions

- The Contingency Theory of Leadership: A Focus on Fit

- Directive Leadership: When It Does—and Doesn’t—Work

- How an Authoritarian Leadership Style Blocks Effective Negotiation

- Paternalistic Leadership: Beyond Authoritarianism

- Using E-Mediation and Online Mediation Techniques for Conflict Resolution

- Undecided on Your Dispute Resolution Process? Combine Mediation and Arbitration, Known as Med-Arb

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Training: Mediation Curriculum

- What Makes a Good Mediator?

- Why is Negotiation Important: Mediation in Transactional Negotiations

- Communication in Negotiation: How Hard Should You Push?

- A Negotiation Preparation Checklist

- Negotiation Team Strategy

- Top 10 Negotiation Skills You Must Learn to Succeed

- Deceptive Tactics in Negotiation: How to Ward Them Off

- The Importance of a Relationship in Negotiation

- Collaborative Negotiation Examples: Tenants and Landlords

- Ethics and Negotiation: 5 Principles of Negotiation to Boost Your Bargaining Skills in Business Situations

- Negotiation Journal celebrates 40th anniversary, new publisher, and diamond open access in 2024

- 10 Negotiation Training Skills Every Organization Needs

- Setting Standards in Negotiations

- Negotiating a Salary When Compensation Is Public

- How to Negotiate a Higher Salary after a Job Offer

- How to Negotiate Pay in an Interview

- How to Negotiate a Higher Salary

- Check Out the All-In-One Curriculum Packages!

- Teaching the Fundamentals: The Best Introductory Negotiation Role Play Simulations

- Check Out Videos from the PON 40th Anniversary Symposium on Negotiation Pedagogy, Practice, & Research

- Teach Your Students to Negotiate a Management Crisis

- Check Out the International Investor-State Arbitration Video Course

- What is a Win-Win Negotiation?

- Win-Win Negotiation: Managing Your Counterpart’s Satisfaction

- Win-Lose Negotiation Examples

- How to Negotiate Mutually Beneficial Noncompete Agreements

- How to Win at Win-Win Negotiation

PON Publications

- Negotiation Data Repository (NDR)

- New Frontiers, New Roleplays: Next Generation Teaching and Training

- Negotiating Transboundary Water Agreements

- Learning from Practice to Teach for Practice—Reflections From a Novel Training Series for International Climate Negotiators

- Insights From PON’s Great Negotiators and the American Secretaries of State Program

- Gender and Privilege in Negotiation

Remember Me This setting should only be used on your home or work computer.

Lost your password? Create a new password of your choice.

Copyright © 2024 Negotiation Daily. All rights reserved.

11 min read

Seven case studies in carbon and climate

Every part of the mosaic of Earth's surface — ocean and land, Arctic and tropics, forest and grassland — absorbs and releases carbon in a different way. Wild-card events such as massive wildfires and drought complicate the global picture even more. To better predict future climate, we need to understand how Earth's ecosystems will change as the climate warms and how extreme events will shape and interact with the future environment. Here are seven pressing concerns.

The Far North is warming twice as fast as the rest of Earth, on average. With a 5-year Arctic airborne observing campaign just wrapping up and a 10-year campaign just starting that will integrate airborne, satellite and surface measurements, NASA is using unprecedented resources to discover how the drastic changes in Arctic carbon are likely to influence our climatic future.

Wildfires have become common in the North. Because firefighting is so difficult in remote areas, many of these fires burn unchecked for months, throwing huge plumes of carbon into the atmosphere. A recent report found a nearly 10-fold increase in the number of large fires in the Arctic region over the last 50 years, and the total area burned by fires is increasing annually.

Organic carbon from plant and animal remains is preserved for millennia in frozen Arctic soil, too cold to decompose. Arctic soils known as permafrost contain more carbon than there is in Earth's atmosphere today. As the frozen landscape continues to thaw, the likelihood increases that not only fires but decomposition will create Arctic atmospheric emissions rivaling those of fossil fuels. The chemical form these emissions take — carbon dioxide or methane — will make a big difference in how much greenhouse warming they create.

Initial results from NASA's Carbon in Arctic Reservoirs Vulnerability Experiment (CARVE) airborne campaign have allayed concerns that large bursts of methane, a more potent greenhouse gas, are already being released from thawing Arctic soils. CARVE principal investigator Charles Miller of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena, California, is looking forward to NASA's ABoVE field campaign (Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment) to gain more insight. "CARVE just scratched the surface, compared to what ABoVE will do," Miller said.

Methane is the Billy the Kid of carbon-containing greenhouse gases: it does a lot of damage in a short life. There's much less of it in Earth's atmosphere than there is carbon dioxide, but molecule for molecule, it causes far more greenhouse warming than CO 2 does over its average 10-year life span in the atmosphere.

Methane is produced by bacteria that decompose organic material in damp places with little or no oxygen, such as freshwater marshes and the stomachs of cows. Currently, over half of atmospheric methane comes from human-related sources, such as livestock, rice farming, landfills and leaks of natural gas. Natural sources include termites and wetlands. Because of increasing human sources, the atmospheric concentration of methane has doubled in the last 200 years to a level not seen on our planet for 650,000 years.

Locating and measuring human emissions of methane are significant challenges. NASA's Carbon Monitoring System is funding several projects testing new technologies and techniques to improve our ability to monitor the colorless gas and help decision makers pinpoint sources of emissions. One project, led by Daniel Jacob of Harvard University, used satellite observations of methane to infer emissions over North America. The research found that human methane emissions in eastern Texas were 50 to 100 percent higher than previous estimates. "This study shows the potential of satellite observations to assess how methane emissions are changing," said Kevin Bowman, a JPL research scientist who was a coauthor of the study.

Tropical forests

Tropical forests are carbon storage heavyweights. The Amazon in South America alone absorbs a quarter of all carbon dioxide that ends up on land. Forests in Asia and Africa also do their part in "breathing in" as much carbon dioxide as possible and using it to grow.

However, there is evidence that tropical forests may be reaching some kind of limit to growth. While growth rates in temperate and boreal forests continue to increase, trees in the Amazon have been growing more slowly in recent years. They've also been dying sooner. That's partly because the forest was stressed by two severe droughts in 2005 and 2010 — so severe that the Amazon emitted more carbon overall than it absorbed during those years, due to increased fires and reduced growth. Those unprecedented droughts may have been only a foretaste of what is ahead, because models predict that droughts will increase in frequency and severity in the future.

In the past 40-50 years, the greatest threat to tropical rainforests has been not climate but humans, and here the news from the Amazon is better. Brazil has reduced Amazon deforestation in its territory by 60 to 70 percent since 2004, despite troubling increases in the last three years. According to Doug Morton, a scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, further reductions may not make a marked difference in the global carbon budget. "No one wants to abandon efforts to preserve and protect the tropical forests," he said. "But doing that with the expectation that [it] is a meaningful way to address global greenhouse gas emissions has become less defensible."

In the last few years, Brazil's progress has left Indonesia the distinction of being the nation with the highest deforestation rate and also with the largest overall area of forest cleared in the world. Although Indonesia's forests are only a quarter to a fifth the extent of the Amazon, fires there emit massive amounts of carbon, because about half of the Indonesian forests grow on carbon-rich peat. A recent study estimated that this fall, daily greenhouse gas emissions from recent Indonesian fires regularly surpassed daily emissions from the entire United States.

Wildfires are natural and necessary for some forest ecosystems, keeping them healthy by fertilizing soil, clearing ground for young plants, and allowing species to germinate and reproduce. Like the carbon cycle itself, fires are being pushed out of their normal roles by climate change. Shorter winters and higher temperatures during the other seasons lead to drier vegetation and soils. Globally, fire seasons are almost 20 percent longer today, on average, than they were 35 years ago.

Currently, wildfires are estimated to spew 2 to 4 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere each year on average — about half as much as is emitted by fossil fuel burning. Large as that number is, it's just the beginning of the impact of fires on the carbon cycle. As a burned forest regrows, decades will pass before it reaches its former levels of carbon absorption. If the area is cleared for agriculture, the croplands will never absorb as much carbon as the forest did.

As atmospheric carbon dioxide continues to increase and global temperatures warm, climate models show the threat of wildfires increasing throughout this century. In Earth's more arid regions like the U.S. West, rising temperatures will continue to dry out vegetation so fires start and burn more easily. In Arctic and boreal ecosystems, intense wildfires are burning not just the trees, but also the carbon-rich soil itself, accelerating the thaw of permafrost, and dumping even more carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere.

North American forests

With decades of Landsat satellite imagery at their fingertips, researchers can track changes to North American forests since the mid-1980s. A warming climate is making its presence known.

Through the North American Forest Dynamics project, and a dataset based on Landsat imagery released this earlier this month, researchers can track where tree cover is disappearing through logging, wildfires, windstorms, insect outbreaks, drought, mountaintop mining, and people clearing land for development and agriculture. Equally, they can see where forests are growing back over past logging projects, abandoned croplands and other previously disturbed areas.

"One takeaway from the project is how active U.S. forests are, and how young American forests are," said Jeff Masek of Goddard, one of the project’s principal investigators along with researchers from the University of Maryland and the U.S. Forest Service. In the Southeast, fast-growing tree farms illustrate a human influence on the forest life cycle. In the West, however, much of the forest disturbance is directly or indirectly tied to climate. Wildfires stretched across more acres in Alaska this year than they have in any other year in the satellite record. Insects and drought have turned green forests brown in the Rocky Mountains. In the Southwest, pinyon-juniper forests have died back due to drought.

Scientists are studying North American forests and the carbon they store with other remote sensing instruments. With radars and lidars, which measure height of vegetation from satellite or airborne platforms, they can calculate how much biomass — the total amount of plant material, like trunks, stems and leaves — these forests contain. Then, models looking at how fast forests are growing or shrinking can calculate carbon uptake and release into the atmosphere. An instrument planned to fly on the International Space Station (ISS), called the Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) lidar, will measure tree height from orbit, and a second ISS mission called the Ecosystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station (ECOSTRESS) will monitor how forests are using water, an indicator of their carbon uptake during growth. Two other upcoming radar satellite missions (the NASA-ISRO SAR radar, or NISAR, and the European Space Agency’s BIOMASS radar) will provide even more complementary, comprehensive information on vegetation.

Ocean carbon absorption

When carbon-dioxide-rich air meets seawater containing less carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas diffuses from the atmosphere into the ocean as irresistibly as a ball rolls downhill. Today, about a quarter of human-produced carbon dioxide emissions get absorbed into the ocean. Once the carbon is in the water, it can stay there for hundreds of years.

Warm, CO 2 -rich surface water flows in ocean currents to colder parts of the globe, releasing its heat along the way. In the polar regions, the now-cool water sinks several miles deep, carrying its carbon burden to the depths. Eventually, that same water wells up far away and returns carbon to the surface; but the entire trip is thought to take about a thousand years. In other words, water upwelling today dates from the Middle Ages – long before fossil fuel emissions.

That's good for the atmosphere, but the ocean pays a heavy price for absorbing so much carbon: acidification. Carbon dioxide reacts chemically with seawater to make the water more acidic. This fundamental change threatens many marine creatures. The chain of chemical reactions ends up reducing the amount of a particular form of carbon — the carbonate ion — that these organisms need to make shells and skeletons. Dubbed the “other carbon dioxide problem,” ocean acidification has potential impacts on millions of people who depend on the ocean for food and resources.

Phytoplankton

Microscopic, aquatic plants called phytoplankton are another way that ocean ecosystems absorb carbon dioxide emissions. Phytoplankton float with currents, consuming carbon dioxide as they grow. They are at the base of the ocean's food chain, eaten by tiny animals called zooplankton that are then consumed by larger species. When phytoplankton and zooplankton die, they may sink to the ocean floor, taking the carbon stored in their bodies with them.

Satellite instruments like the Moderate resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra and Aqua let us observe ocean color, which researchers can use to estimate abundance — more green equals more phytoplankton. But not all phytoplankton are equal. Some bigger species, like diatoms, need more nutrients in the surface waters. The bigger species also are generally heavier so more readily sink to the ocean floor.

As ocean currents change, however, the layers of surface water that have the right mix of sunlight, temperature and nutrients for phytoplankton to thrive are changing as well. “In the Northern Hemisphere, there’s a declining trend in phytoplankton,” said Cecile Rousseaux, an oceanographer with the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at Goddard. She used models to determine that the decline at the highest latitudes was due to a decrease in abundance of diatoms. One future mission, the Pre-Aerosol, Clouds, and ocean Ecosystem (PACE) satellite, will use instruments designed to see shades of color in the ocean — and through that, allow scientists to better quantify different phytoplankton species.

In the Arctic, however, phytoplankton may be increasing due to climate change. The NASA-sponsored Impacts of Climate on the Eco-Systems and Chemistry of the Arctic Pacific Environment (ICESCAPE) expedition on a U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker in 2010 and 2011 found unprecedented phytoplankton blooms under about three feet (a meter) of sea ice off Alaska. Scientists think this unusually thin ice allows sunlight to filter down to the water, catalyzing plant blooms where they had never been observed before.

Related Terms

- Carbon Cycle

Explore More

As the Arctic Warms, Its Waters Are Emitting Carbon

Runoff from one of North America’s largest rivers is driving intense carbon dioxide emissions in the Arctic Ocean. When it comes to influencing climate change, the world’s smallest ocean punches above its weight. It’s been estimated that the cold waters of the Arctic absorb as much as 180 million metric tons of carbon per year […]

Peter Griffith: Diving Into Carbon Cycle Science

Dr. Peter Griffith serves as the director of NASA’s Carbon Cycle and Ecosystems Office at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Dr. Griffith’s scientific journey began by swimming in lakes as a child, then to scuba diving with the Smithsonian Institution, and now he studies Earth’s changing climate with NASA.

NASA Flights Link Methane Plumes to Tundra Fires in Western Alaska

Methane ‘hot spots’ in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta are more likely to be found where recent wildfires burned into the tundra, altering carbon emissions from the land. In Alaska’s largest river delta, tundra that has been scorched by wildfire is emitting more methane than the rest of the landscape long after the flames died, scientists have […]

Discover More Topics From NASA

Explore Earth Science

Earth Science in Action

Earth Science Data

Facts About Earth

Rising inequality affecting more than two-thirds of the globe, but it’s not inevitable: new UN report

Facebook Twitter Print Email

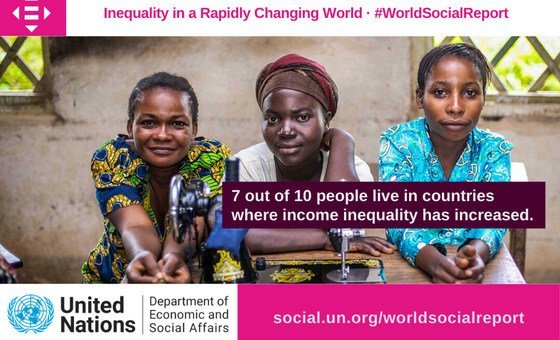

Inequality is growing for more than 70 per cent of the global population, exacerbating the risks of divisions and hampering economic and social development. But the rise is far from inevitable and can be tackled at a national and international level, says a flagship study released by the UN on Tuesday.

The World Social Report 2020, published by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), shows that income inequality has increased in most developed countries, and some middle-income countries - including China, which has the world’s fastest growing economy.

The challenges are underscored by UN chief António Guterres in the foreword, in which he states that the world is confronting “the harsh realities of a deeply unequal global landscape”, in which economic woes, inequalities and job insecurity have led to mass protests in both developed and developing countries.

“Income disparities and a lack of opportunities”, he writes, “are creating a vicious cycle of inequality, frustration and discontent across generations.”

‘The one per cent’ winners take (almost) all

The study shows that the richest one per cent of the population are the big winners in the changing global economy, increasing their share of income between 1990 and 2015, while at the other end of the scale, the bottom 40 per cent earned less than a quarter of income in all countries surveyed.

One of the consequences of inequality within societies, notes the report, is slower economic growth. In unequal societies, with wide disparities in areas such as health care and education, people are more likely to remain trapped in poverty, across several generations.

Between countries, the difference in average incomes is reducing, with China and other Asian nations driving growth in the global economy. Nevertheless, there are still stark differences between the richest and poorest countries and regions: the average income in North America, for example, is 16 times higher than that of people in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Four global forces affecting inequality

The report looks at the impact that four powerful global forces, or megatrends, are having on inequality around the world: technological innovation, climate change, urbanization and international migration.

Whilst technological innovation can support economic growth, offering new possibilities in fields such as health care, education, communication and productivity, there is also evidence to show that it can lead to increased wage inequality, and displace workers.

Rapid advances in areas such as biology and genetics, as well as robotics and artificial intelligence, are transforming societies at pace. New technology has the potential to eliminate entire categories of jobs but, equally, may generate entirely new jobs and innovations.

For now, however, highly skilled workers are reaping the benefits of the so-called “fourth industrial revolution”, whilst low-skilled and middle-skilled workers engaged in routine manual and cognitive tasks, are seeing their opportunities shrink.

Opportunities in a crisis

As the UN’s 2020 report on the global economy showed last Thursday, the climate crisis is having a negative impact on quality of life, and vulnerable populations are bearing the brunt of environmental degradation and extreme weather events. Climate change, according to the World Social Report, is making the world’s poorest countries even poorer, and could reverse progress made in reducing inequality among countries.

If action to tackle the climate crisis progresses as hoped, there will be job losses in carbon-intensive sectors, such as the coal industry, but the “greening” of the global economy could result in overall net employment gains, with the creation of many new jobs worldwide.

For the first time in history, more people live in urban than rural areas, a trend that is expected to continue over the coming years. Although cities drive economic growth, they are more unequal than rural areas, with the extremely wealthy living alongside the very poor.

The scale of inequality varies widely from city to city, even within a single country: as they grow and develop, some cities have become more unequal whilst, in others, inequality has declined.

Migration a ‘powerful symbol of global inequality’

The fourth megatrend, international migration, is described as both a “powerful symbol of global inequality”, and “a force for equality under the right conditions”.

Migration within countries, notes the report, tends to increase once countries begin to develop and industrialize, and more inhabitants of middle-income countries than low-income countries migrate abroad.

International migration is seen, generally, as benefiting both migrants, their countries of origin (as money is sent home) and their host countries.

In some cases, where migrants compete for low-skilled work, wages may be pushed down, increasing inequality but, if they offer skills that are in short supply, or take on work that others are not willing to do, they can have a positive effect on unemployment.

Harness the megatrends for a better world

Despite a clear widening of the gap between the haves and have-nots worldwide, the report points out that this situation can be reversed. Although the megatrends have the potential to continue divisions in society, they can also, as the Secretary-General says in his foreword, “be harnessed for a more equitable and sustainable world”. Both national governments and international organizations have a role to play in levelling the playing field and creating a fairer world for all.

Reducing inequality should, says the report, play a central role in policy-making. This means ensuring that the potential of new technology is used to reduce poverty and create jobs; that vulnerable people grow more resilient to the effects of climate change; cities are more inclusive; and migration takes place in a safe, orderly and regular manner.

Three strategies for making countries more egalitarian are suggested in the report: the promotion of equal access to opportunities (through, for example, universal access to education); fiscal policies that include measures for social policies, such as unemployment and disability benefits; and legislation that tackles prejudice and discrimination, whilst promoting greater participation of disadvantaged groups.

While action at a national level is crucial, the report declares that “concerted, coordinated and multilateral action” is needed to tackle major challenges affecting inequality within and among countries.

The report’s authors conclude that, given the importance of international cooperation, multilateral institutions such as the UN should be strengthened and action to create a fairer world must be urgently accelerated.

The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development , which provides the blueprint for a better future for people and the planet, recognizes that major challenges require internationally coordinated solutions, and contains concrete and specific targets to reduce inequality, based on income.

- World Social Report

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

International business

- Business management

- Business communication

- Collaboration and teams

- Corporate communications

- Corporate governance

How Expats Should Lead in China

- Lynn S. Paine

- December 20, 2011

Where the Race for Talent Is Tight, Women Gain Speed

- Avivah Wittenberg-Cox

- April 12, 2013

The Latest Supply Chain Disruption: Plastics

- Bindiya Vakil

- March 26, 2021

Samsung, Lee Jae-yong's Conviction, and How Business in South Korea Is Changing

- Hansoo Choi

- September 29, 2017

Government Should Enlist Foreign Companies in Rebuilding America’s Industrial Commons

- Robert H. Hayes

- November 10, 2009

Copenhagen: Focus on the (Carbon) Negative

- Nicholas Eisenberger and David Gottesman

- December 07, 2009

Asia’s Key New Segment: Powerful, Professional Women

- Dae Ryun Chang

- April 10, 2013

How General Mills Uses Food Technology to Make an Impact in Africa

- March 06, 2013

The Most Attractive Cities to Move to for Work

- Kevin Randall

- March 06, 2017

The Economic Impact of the Japanese Disasters

- W. Carl Kester

- March 22, 2011

The New Economics of Business (Or, the Case For Going Great-to-Good)

- Umair Haque

- February 09, 2010

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

- Hurd Baruch

- From the January 1979 Issue

The Pope’s “War on Capitalism” and Why Rich Kids Stay Rich

- Kaisa Snellman

- December 03, 2013

Engineering Reverse Innovations

- Amos Winter

- Vijay Govindarajan

- From the July–August 2015 Issue

Citicorp Faces the World: An Interview with John Reed

- Noel Tichy and Ram Charan

- From the November–December 1990 Issue

Find Out if You’re a Scale-Up Entrepreneur with This Two-Minute Test

- Daniel Isenberg

- May 24, 2013

Reversing the Curse of Dominant Logic

- March 26, 2012

Brexit and the Triumph of Insularity

- David Champion

- June 24, 2016

Be a Better Manager: Live Abroad

- William Maddux

- Adam D. Galinsky

- Carmit T. Tadmor

- From the September 2010 Issue

Mythology, Markets, and the Emerging Europe

- Andrew Hilton

- From the November–December 1992 Issue

Facebook, Inc.

- Frank T. Rothaermel

- October 18, 2019

Reliance Industries: Building Execution Excellence in an Emerging Market

- Kannan Ramaswamy

- February 01, 2018

Finning International Inc.: Management Systems in 2009

- Murray J. Bryant

- January 06, 2010

British Airways

- John A. Quelch

- July 17, 1984

Khedut Feeds & Foods Private Limited: Implications of Country of Origin

- Sanjay Kumar Jena

- Sourav Bikash Borah

- Amalesh Sharma

- April 12, 2023

Dr. Lal Pathlabs (B)

- Ajeet Mathur

- December 19, 2017

Illinois Tool Works: Retooling for Continued Growth and Profitability

- Nitin Pangarkar

- January 30, 2017

RBC - Financing Oil Sands (A)

- Michael Sider

- Jana Seijts

- Chandra Sekhar Ramasastry

- January 27, 2010

Refinancing of Shanghai General Motors (B)

- Mihir A. Desai

- Mark F. Veblen

- July 27, 2003

McDonald's Corporation

- November 04, 2019

- Andrew McAfee

- Alexandra De Royere

- December 13, 2005

Hewlett-Packard: Singapore (C)

- Dorothy Leonard-Barton

- George Thill

- September 27, 1993

Global Dexterity: How to Adapt Your Behavior Across Cultures without Losing Yourself in the Process

- Andrew Molinsky

- March 12, 2013

Dubai Internet City: Serving Business

- Jacques Horovitz

- Anne-Valerie Ohlsson

- January 01, 2004

King Digital Entertainment

- Jeffrey Rayport

- Davide Sola

- Federica Gabrieli

- Elena Corsi

- April 14, 2017

Hon Hai's Investment in Sharp

- Keith Chi-ho Wong

- Zachary Markovich

- February 11, 2016

Alibaba's Taobao (A)

- Felix Oberholzer-Gee

- Julie M. Wulf

- January 06, 2009

HCL Technologies (B)

- Linda A. Hill

- Tarun Khanna

- August 03, 2007

International Lobbying and The Dow Chemical Company (B): Regulatory Reform in the USA?

- Arthur A. Daemmrich

- November 12, 2009

Hoechst and the German Chemical Industry

- Benjamin Gomes-Casseres

- Krista McQuade

- January 30, 1990

Introduction to Credit Default Swaps, Teaching Note

- Muhammad Fuad Farooqi

- Walid Busaba

- Zeigham Khokher

- September 03, 2010

Popular Topics

Partner center.

Case Studies of Global Governance for Health Research

- First Online: 14 November 2019

Cite this chapter

- Kiarash Aramesh 4

Part of the book series: Advancing Global Bioethics ((AGBIO,volume 15))

155 Accesses

This chapter is specified to a number of case studies to portray the challenges of Global Health Governance and Global Governance for Health Research in the real-world through historical cases. The fourth chapter begins with a broader scope. In the first case, Zika pandemic, it shows how Global Health Governance uses previous experiences to deal with newly-emerged pandemics. Research integrity in Iran discusses how local practices on research integrity are important at the global scale and should be addressed by Global Governance for Health Research. HIV/AIDS Research in LMICs describes a paradigm case of exploitation in research that contributed to a significant shift in the history of clinical research. Sending Biological Specimens Abroad discusses bio-piracy as a topic within Global Governance for Health Research. Also, it shows how international collaborations may be seen by the weaker sides. Research on Pre-Implantation Human Embryo portrays how different religious and seculars perspectives collectively take part in shaping the ethical grounds for Global Governance for Health Research. The final case study in this chapter, Traditional Medicines, Science-Pseudoscience Debate, and Biopiracy, addresses the globalized aspects of science-pseudoscience debate and Biopiracy by discussing traditional medicines as a paradigm example. By exploring such spectrum of real-world cases, the fourth chapter portrays the existing need of Global Health Governance and Global Governance for Health Research to a comprehensive ethical framework. It also shows how particular challenges or ethical principles are more relevant to each case.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Hazel J Markwell, and Barry F Brown, “Catholic Bioethics,” 189.

Bibliography

Abdelgawad, By Walid. 2012. The Bt Brinjal Case: The First Legal Action Against Monsanto and its Indian Collaborators for Biopiracy. Biotechnology Law Report 31 (2): 136–139.

Article Google Scholar

Afshar, Leila, and Alireza Bagheri. 2013. Embryo Donation in Iran: An Ethical Review. Developing World Bioethics 13 (3): 119–124.

Akrami, Moosa. 2012. Why the Website of Professors Against Plaigarism Is Filtered? Mirath Report 2 (2): 70–71.

Google Scholar

Alef Society for News and Analysis. 2018. Ebtekar’s Explanations About Natur’s Paper and the Findings of De Ja Vu Project . http://alef.ir/vdcg7y9w.ak9xn4prra.html?32958 .

Andorno, Roberto. 2009. Human Dignity and Human Rights. In The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights: Background, Principles, and Application , ed. Henk ten Have and Michèle S. Jean, 91–98. Paris: UNESCO.

Angell, Marcia. 1997. The Ethics of Clinical Research in the Third World. New England Journal of Medicine 337: 847–848.

Annas, G.J., and M.A. Grodin. 1998. Human Rights and Maternal-Fetal HIV Transmission Prevention Trials in Africa. American Journal of Public Health 88 (4): 560–563.

———. 2008. The Nuremberg Code. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics , ed. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David Wendler, 136–140. New York: Oxford University Press.

Aramesh, Kiarash. 2007. The Influences of Bioethics and Islamic Jurisprudence on Policy-Making in Iran. The American Journal of Bioethics 7 (10): 42–44.

———. 2008. Cultural Diversity and Bioethics. Iranian Journal of Public Health 37 (1): 28–30.

———. 2017. Bio-politics, Pseudoscience, and Bioethics in the Global South. The American Journal of Bioethics 17 (10): 26–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2017.1365187 .

———. 2018. Science and Pseudoscience in Traditional Iranian Medicine. Archive of Iranian Medicine 21 (7): 315–323.

Aramesh, Kiarash, and Soroush Dabbagh. 2007. An Islamic View to Stem Cell Research and Cloning: Iran’s Experience. American Journal of Bioethics 7 (2): 62–63.

Ashcroft, Richard E. 2008. The Declaration of Helsinki. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics , ed. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David Wendler, 141–148. New York: Oxford University Press.

Barnett, Michael, and Raymond Duvall. 2014. International Organizations and the Diffusion of Power. In International Organization and Global Bioethics , ed. Thomas G. Weiss and Rorden Wilkinson, 48–59. London/New York: Routledge.

Beauchamp, Tom L. 2008. The Belmont Report. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics , ed. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David Wendler, 149–155. New York: Oxford University Press.

Buse, Kent, and Gill Walt. 2002. The World Health Organization and Global Public-Private Health Partnerships. In Search of ‘Good’ Global Health Governance. PUBLIC-PRIVATE : 169.

Butler, D. 2008. Iranian Paper Sparks Sense of Deja Vu. Nature 455 (7216): 1019.

———. 2009a. Iranian Ministers in Plagiarism Row. Nature 461 (7264): 578–579.

———. 2009b. Plagiarism Scandal Grows in Iran. Nature 462 (7274): 704–705.

Chen, L.H., and D.H. Hamer. 2016. Zika Virus: Rapid Spread in the Western Hemisphere. Annals of Internal Medicine 164: 613–615.

CNN. 2018. Stem Cells Fast Facts. CNN , July 17, 2018. http://www.cnn.com/2013/07/05/health/stem-cells-fast-facts/ .

Copland, P.S. 2004. The Roman Catholic Church and Embryonic Stem Cells. Journal of Medical Ethics 30 (6): 607–608.

Cressey, D. 2017. Treaty to Stop Biopiracy Threatens to Delay Flu Vaccines. Nature 542 (7640): 148.

Dabbagh, S., and K. Aramesh. 2009. The Compatibility between Shiite and Kantian Approach to Passive Voluntary Euthanasia. Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine 2: 21.

De Cock, Kevin M., Mary Glenn Fowler, Eric Mercier, Isabelle de Vincenzi, Joseph Saba, Elizabeth Hoff, David J. Alnwick, Martha Rogers, and Nathan Shaffer. 2000. Prevention of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission in Resource-Poor Countries: Translating Research into Policy and Practice. JAMA 283 (9): 1175–1182.

DeGrazia, David. 2012. Creation Ethics: Reproduction, Genetics, and Quality of Life . Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Dickens, B.M. 2016. The Use and Disposal of Stored Embryos. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics (Apr 18 2016).

Efferth, Thomas, Mita Banerjee, Norbert W. Paul, Sara Abdelfatah, Joachim Arend, Gihan Elhassan, Sami Hamdoun, et al. 2016. Biopiracy of Natural Products and Good Bioprospecting Practice. Phytomedicine 23 (2): 166–173.

Emanuel, Ezekiel J., and Christine Grady. 2008. Four Paradigms of Clinical Research and Research Oversight. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research , ed. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David Wendler, 222–230. New York: Oxford University Press.

Emanuel, Ezekiel J., David Wendler, and Christine Grady. 2008. An Ethical Framework for Biomedical Research. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics , ed. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David Wendler, 123–135. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Ernst, Edzard, M.H. Cohen, and J. Stone. 2004. Ethical Problems Arising in Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Journal of Medical Ethics 30 (2): 156–159.

Fauci, Anthony S. 2014. Ebola—Underscoring the Global Disparities in Health Care Resources. New England Journal of Medicine 371 (12): 1084–1086.

Fauci, A. S., and D. M. Morens. 2016. Zika Virus in the Americas - Yet Another Arbovirus Threat. The New England Journal of Medicine (Jan 13 2016).

Floor, Willem. 2007. Salaamate Mrdom Dar Iran E Qajar (Public Health in Qajar Iran) [in Persian]. Translated by Iraj Nabipour. Tehran: Medical Ethics and History of Medicine Research Center.

Freedman, Benjamin. 1987. Equipoise and the Ethics of Clinical Research. New England Journal of Medicine 317 (3): 141–145.

Frenk, Julio, and Suerie Moon. 2013. Governance Challenges in Global Health. New England Journal of Medicine 368 (10): 936–942.

Galjaard, Hans. 2009. Sharing of Benefits. In The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights: Background, Principles, and Application , ed. Henk ten Have and Michèle S. Jean, 231–242. Paris: UNESCO.

Ghajarzadeh, M., A. Norouzi-Javidan, K. Hassanpour, K. Aramesh, and S.H. Emami-Razavi. 2012. Attitude toward Plagiarism among Iranian Medical Faculty Members. Acta Medica Iranica 50 (11): 778–781.

Ghajarzadeh, M., K. Hassanpour, S.M. Fereshtehnejad, A. Jamali, S. Nedjat, and K. Aramesh. 2013. Attitude Towards Plagiarism Among Iranian Medical Students. Journal of Medical Ethics 39 (4): 249.

Gottweis, Herbert, and Robert Triendl. 2006. South Korean Policy Failure and the Hwang Debacle. Nature Biotechnology 24 (2): 141–143.

Green, Ronald M. 2008. Research with Fetuses, Embryos, and Stem Cells. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics , ed. E.J. Emanuel, C. Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and D. Wendler, 488–499. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Gulland, A. 2016. Who Urges Countries in Dengue Belt to Look out for Zika. BMJ 352: i595.

Hall, Harriet. 2015. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) Didn’t Win a Nobel Prize, Scientific Medicine Did . https://www.csicop.org/specialarticles/show/traditional_chinese_medicine_tcm_didnrsquot_win_a_nobel_prize_scientific_me .

Hansen, K., and K. Kappel. 2010. The Proper Role of Evidence in Complementary/Alternative Medicine. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 35 (1): 7–18.

Harman, Sophie. 2014. Global Health Governance. In International Organization and Global Governance , ed. Rorden Wilkinson and Thomas G. Weiss, 656–667. London/New York: Routledge.

Harper, J., J. Geraedts, P. Borry, M.C. Cornel, W.J. Dondorp, L. Gianaroli, G. Harton, et al. 2014. Current Issues in Medically Assisted Reproduction and Genetics in Europe: Research, Clinical Practice, Ethics, Legal Issues and Policy. Human Reproduction 29 (8): 1603–1609.

Hurd, Elizabeth Shakman. 2012. International Politics after Secularism. Review of International Studies 38 (5): 943–961.

Irani, Nader. Twenty Seven Years of Discrimination in the Educational System . http://www.equal-rights-now.com/maqalat/aamozash.htm .

Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education. 2018. The National Ethical Guideline for Sending Biological Specimens Abroad for Research Purposes . http://ethics.research.ac.ir/docs/ethics_material_transfer.pdf .

Kakuk, Peter. 2009. The Legacy of the Hwang Case: Research Misconduct in Biosciences. Science and Engineering Ethics 15 (4): 545–562.

Kamau, Evanson Chege, Bevis Fedder, and Gerd Winter. 2010. The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit Sharing: What Is New and What Are the Implications for Provider and User Countries and the Scientific Community? Law & Development Journal (LEAD) 6 (3): 248–263.

Kelly, David F., Gerard Magill, and Henk ten Have. 2013. Contemporary Catholic Health Care Ethics . Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Killen, John Y., Jr. 2008. HIV Research. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics , ed. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David Wendler, 97–109. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kmietowicz, Z. 2016. Questions Your Patients May Have About Zika Virus. BMJ 352: i649.

Ku, Charlotte. 2014. The Evolution of International Law. In International Organization and Global Governance , ed. Thomas G. Weiss and Rorden Wilkinson, 35–47. London/New York: Routledge.

Lange, M.M., W. Rogers, and S. Dodds. 2013. Vulnerability in Research Ethics: A Way Forward. Bioethics 27 (6): 333–340.

Larijani, Bagher, Farzaneh Zahedi, and Hossein Malek Afzali. 2005. Medical Ethics in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 11: 5–6.

Lee, K., and A. Mills. 2000. Strengthening Governance for Global Health Research. BMJ 321 (7264): 775–776.

Lurie, Peter, and Sidney M. Wolfe. 1997. Unethical Trials of Interventions to Reduce Perinatal Transmission of the Humsn Immunodeficiency Virus in Developing Countriess. New England Journal of Medicine. 337: 853–856.

MacKenzie, Debora. 2010. Iran Showing Fastest Scientific Growth of Any Country . February 18, 2010. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn18546-iran-showing-fastest-scientific-growth-of-any-country/ .

Macklin, Ruth. 2008. Appropriate Ethical Standards. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics , ed. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David Wendler, 711–718. New York: Oxford University Press.

Magill, Gerard. 2001. Ethics Weave in Human Genomics, Embryonic Stem Cell Research, and Therapeutic Cloning: Promoting and Protecting Society’s Interests. The Albany Law Review 65: 701.

Mansell, M.A. 2001. Research Governance – Global or Local? The Medico-Legal Journal 69: 1–3.

Matsuura, Koichiro. 2009. Preface. In The UNESCO Universal Decaration on Bioethics and Human Rights , ed. Henk A.M.J. ten Have and Michèle S. Jean, 9–10. Paris: UNESCO.

McCarthy, M. 2016. Zika Virus Outbreak Prompts Us to Issue Travel Alert to Pregnant Women. BMJ 352: i306.

McIntire, Steve. 2011. What Happened to Gerald Schatten? Climate Audit, May 31, 2011. http://climateaudit.org/2011/05/31/what-happened-to-gerald-schatten/ .

Miles, Tom, and Ben Hirschler. 2016. Zika Virus Set to Spread across Americas, Spurring Vaccine Hunt. Reuters , January 25, 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-idUSKCN0V30U6 .

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. 2018. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s in a Name? November 8, 2018. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health .

National Institutes of Health. 2019. Research Integrity: Why Does Research Integrity Matter? June 19, 2018. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/research_integrity/care.htm .

———. n.d.-a What Are Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells? http://stemcells.nih.gov/info/basics/pages/basics10.aspx .

———. n.d.-b Research Integrity. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/research_integrity/index.htm .

National Stem Cell Foundation. n.d. Stem Cell Research Facts . http://www.nationalstemcellfoundation.org/stem-cell-research-facts/ .

Neves, Maria Patrao. 2009. Respect for Human Vulnerability and Personal Integrity. In The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights: Background, Principles, and Application , ed. Henk ten Have and Michèle S. Jean, 155–164. Paris: UNESCO.

Park, Robert L. 2000. Voodoo Science: The Road from Foolishness to Fraud . Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 2008. Superstition: Belief in the Age of Science . Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Petersdorf, Robert G. 1986. Fraud, Irresponsible Authorship, and Their Causes: The Pathogenesis of Fraud in Medical Science. Annals of Internal Medicine 104 (2): 252–254.

Porter, Joan P., and Creg Koski. 2008. Regulations for the Protection of Humans in Research in the United States. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics , ed. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David Wendler, 156–167. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rao, M., C. Mason, and S. Solomon. 2015. Cell Therapy Worldwide: An Incipient Revolution. Regenerative Medicine 10 (2): 181–191.

Reagan, J.A. 2015. Taming Our Brave New World. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 40 (6): 621–632.

Resnik, David B. 2008. Fraud, Fabrication, and Falsification. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics , ed. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar K. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David Wendler, 787–794. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Resnik, David B., and Adil E. Shamoo. 2011. The Singapore Statement on Research Integrity. Accountability in Research 18 (2): 71–75.

Revel, Michel. 2009. Respect for Cultural Diversity and Pluralism. In The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights: Background, Principles, and Application , ed. Henk ten Have and Michèle S. Jean, 199–210. Paris: UNESCO.

Rezaeizadeh, H., M. Alizadeh, M. Naseri, and M.R. Shams Ardakani. 2009. The Traditional Iranian Medicine Point of View on Health And. Iranian Journal of Public Health 38 (1): 169–172.

Sachedina, Abdulaziuz. 2009. Islamic Biomedical Ethics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Salter, Brian. 2007. The Global Politics of Human Embryonic Stem Cell Science. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 13 (2): 277–298.

Taylor, Allyn L. 2002. Global Governance, International Health Law and Who: Looking Towards the Future. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 80 (12): 975–980.

Teichfischer, P. 2012. Ethical Implications of the Increasing Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Forschende Komplementärmedizin 19 (6): 311–318.

ten Have, Henk. 2016. Global Bioethics: An Introduction . London/New York: Routledge.

ten Have, Henk, and Michèle S. Jean. 2009. Introduction. In The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights: Background, Principles and Application , ed. Henk A.M.J. ten Have and Michèle S. Jean, 16–55. Paris: UNESCO.

The Islamic Parliament Reseach Center. n.d. The Law for Fascilitation the Entrance of Veteranc to Universities Anf Higher Education Institutions . http://rc.majlis.ir/fa/law/show/92115 .

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and The Office of Research Integrity. n.d. Historical Background . http://ori.hhs.gov/historical-background .

UNESCO. 2005. The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights . UNESCO, Last modified October 19, 2005. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=31058&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html .

United States Institute of Peace. 2004. What Works? Evaluating Interfaith Dialogue Programs . Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

Wahlberg, A., C. Rehmann-Sutter, M. Sleeboom-Faulkner, G. Lu, O. Doring, Y. Cong, A. Laska-Formejster, et al. 2013. From Global Bioethics to Ethical Governance of Biomedical Research Collaborations. Social Science & Medicine 98: 293–300.

Walters, LeRoy. 2004. Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research: An Intercultural Perspective. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 14 (1): 3–38.

Wood, B.D. 2010. Academic Misconduct and Detection. Radiologic Technology 81 (3): 276–279.

Woods, Ngaire, Alexander Betts, Jochen Prantl, and Devi Sridhar. 2013. Transforming Global Governance for the 21st Century. UNDP-HDRO Occasional Papers , no. 2013/09.

World Health Organization. 2007a. Addressing Ethical Issues in Pandemic Influenza Planning . World Health Organization. Last modified 2007. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/cds_flu_ethics_5web.pdf .

———. 2007b. Ethical Considerations in Developing a Public Health Response to Pandemic Influenza . WHO. Last modified 2007. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/WHO_CDS_EPR_GIP_2007_2c.pdf .

———. 2015. Origins of the 2014 Ebola Epidemic . Last modified January 2015. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/one-year-report/virus-origin/en/ .

———. 2018. Zika Virus: Fact Sheet . WHO. Last modified July 20, 2018. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/zika/en/ .

Youde, Jeremy. 2012. Global Health Governance . Malden: Polity Press.

Zahedi, F., and B. Larijani. 2008. National Bioethical Legislation and Guidelines for Biomedical Research in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86 (8): 630–643.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Edinboro University of Pennsylvania, Edinboro, PA, USA

Kiarash Aramesh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions