- WRITING SKILLS

Journalistic Writing

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Writing Skills:

- A - Z List of Writing Skills

The Essentials of Writing

- Common Mistakes in Writing

- Introduction to Grammar

- Improving Your Grammar

- Active and Passive Voice

- Punctuation

- Clarity in Writing

- Writing Concisely

- Coherence in Writing

- Gender Neutral Language

- Figurative Language

- When to Use Capital Letters

- Using Plain English

- Writing in UK and US English

- Understanding (and Avoiding) Clichés

- The Importance of Structure

- Know Your Audience

- Know Your Medium

- Formal and Informal Writing Styles

- Note-Taking from Reading

- Note-Taking for Verbal Exchanges

- Creative Writing

- Top Tips for Writing Fiction

- Writer's Voice

- Writing for Children

- Writing for Pleasure

- Writing for the Internet

- Technical Writing

- Academic Writing

- Editing and Proofreading

Writing Specific Documents

- Writing a CV or Résumé

- Writing a Covering Letter

- Writing a Personal Statement

- Writing Reviews

- Using LinkedIn Effectively

- Business Writing

- Study Skills

- Writing Your Dissertation or Thesis

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Journalistic writing is, as you might expect, the style of writing used by journalists. It is therefore a term for the broad style of writing used by news media outlets to put together stories.

Every news media outlet has its own ‘house’ style, which is usually set out in guidelines. This describes grammar and style points to be used in that publication or website. However, there are some common factors and characteristics to all journalistic writing.

This page describes the five different types of journalistic writing. It also provides some tips for writing in journalistic style to help you develop your skills in this area.

The Purpose of Journalistic Writing

Journalistic writing has a very clear purpose: to attract readers to a website, broadcaster or print media. This allows the owners to make money, usually by selling advertising space.

Newspapers traditionally did not make most of their money by selling newspapers. Instead, their main income was actually from advertising. If you look back at an early copy of the London Times , for example (from the early 1900s), the whole front page was actually advertisements, not news.

The news and stories are only a ‘hook’ to bring in readers and keep advertisers happy.

Journalists therefore want to attract readers to their stories—and then keep them.

They are therefore very good at identifying good stories, but also telling the story in a way that hooks and keeps readers interested.

Types of Journalistic Writing

There are five main types of journalistic writing:

Investigative journalism aims to discover the truth about a topic, person, group or event . It may require detailed and in-depth exploration through interviews, research and analysis. The purpose of investigative journalism is to answer questions.

News journalism reports facts, as they emerge . It aims to provide people with objective information about current events, in straightforward terms.

Feature writing provides a deeper look at events, people or topics , and offer a new perspective. Like investigative journalism, it may seek to uncover new information, but is less about answering questions, and more about simply providing more information.

Columns are the personal opinions of the writer . They are designed to entertain and persuade readers, and sometimes to be controversial and generate discussion.

Reviews describe a subject in a factual way, and then provide a personal opinion on it . They are often about books or television programmes when published in news media.

The importance of objectivity

It should be clear from the list of types of journalistic writing that journalists are not forbidden from expressing their opinions.

However, it is important that any journalist is absolutely clear when they are expressing their opinion, and when they are reporting on facts.

Readers are generally seeking objective writing and reporting when they are reading news or investigative journalism, or features. The place for opinions is columns or reviews.

The Journalistic Writing Process

Journalists tend to follow a clear process in writing any article. This allows them to put together a compelling story, with all the necessary elements.

This process is:

1. Gather all necessary information

The first step is to gather all the information that you need to write the story.

You want to know all the facts, from as many angles as possible. Journalists often spend time ‘on site’ as part of this process, interviewing people to find out what has happened, and how events have affected them.

Ideally, you want to use primary sources: people who were actually there, and witnessed the events. Secondary sources (those who were told by others what happened) are very much second-best in journalism.

2. Verify all your sources

It is crucial to establish the value of your information—that is, whether it is true or not.

A question of individual ‘truth’

It has become common in internet writing to talk about ‘your truth’, or ‘his truth’.

There is a place for this in journalism. It recognises that the same events may be experienced and interpreted in different ways by different people.

However, journalists also need to recognise that there are always some objective facts associated with any story. They must take time to separate these objective facts from opinions or perceptions and interpretations of events.

3. Establish your angle

You then need to establish your story ‘angle’ or focus: the aspect that makes it newsworthy.

This will vary with different types of journalism, and for different news outlets. It may also need some thought to establish why people should care about your story.

4. Write a strong opening paragraph

Your opening paragraph tells readers why they should bother to read on.

It needs to summarise the five Ws of the story: who, what, why, when, and where.

5. Consider the headline

Journalists are not necessarily expected to come up with their own headlines. However, it helps to consider how a piece might be headlined.

Being able to summarise the piece in a few words is a very good way to ensure that you are clear about your story and angle.

6. Use the ‘inverted pyramid’ structure

Journalists use a very clear structure for their stories. They start with the most important information (the opening paragraph, above), then expand on that with more detail. Finally, the last section of the article provides more information for anyone who is interested.

This means that you can therefore glean the main elements of any news story from the first paragraph—and decide if you want to read on.

Why the Inverted Pyramid?

The inverted pyramid structure actually stems from print journalism.

If typesetters could not fit the whole story into the space available, they would simply cut off the last few sentences until the article fitted.

Journalists therefore started to write in a way that ensured that the important information would not be removed during this process!

7. Edit your work carefully

The final step in the journalistic writing process is to edit your work yourself before submitting it.

Newsrooms and media outlets generally employ professional editors to check all copy before submitting it. However, journalists also have a responsibility to check their work over before submission to make sure it makes sense.

Read your work over to check that you have written in plain English , and that your meaning is as clear as possible. This will save the sub-editors and editors from having to waste time contacting you for clarifications.

Journalistic Writing Style

As well as a very clear process, journalists also share a common style.

This is NOT the same as the style guidelines used for certain publications (see box), but describes common features of all journalistic writing.

The features of journalistic writing include:

Short sentences . Short sentences are much easier to read and understand than longer ones. Journalists therefore tend to keep their sentences to a line of print or less.

Active voice . The active voice (‘he did x’, rather than ‘x was done by him’) is action-focused, and shorter. It therefore keeps readers’ interest, and makes stories more direct and personal.

Quotes. Most news stories and journalistic writing will include quotes from individuals. This makes the story much more people-focused—which is more likely to keep readers interested. This is why many press releases try to provide quotes (and there is more about this in our page How to Write a Press Release ).

Style guidelines

Most news media have style guidelines. They may share these with other outlets (for example, by using the Associated Press guidelines), or they may have their own (such as the London Times style guide).

These guidelines explain the ‘house style’. This may include, for example, whether the outlet commonly uses an ‘Oxford comma’ or comma placed after the penultimate item in a list, and describe the use of capitals or italics for certain words or phrases.

It is important to be aware of these style guidelines if you are writing for a particular publication.

Journalistic writing is the style used by news outlets to tell factual stories. It uses some established conventions, many of which are driven by the constraints of printing. However, these also work well in internet writing as they grab and hold readers’ attention very effectively.

Continue to: Writing for the Internet Cliches to Avoid

See also: Creative Writing Technical Writing Coherence in Writing

The Art of Journalistic Writing: A Comprehensive Guide ✍️

Journalistic writing aims to provide accurate and objective news coverage to the audience. Learn how to write like journalists in this comprehensive guide.

In the fast-paced realm of freelance writing, captivating and informative articles are the key to setting yourself apart from the competition. That's where the art of journalistic writing becomes your secret weapon.

Below, we'll delve into the significance of journalistic writing for Independents, demystify its definition and various types, explore its essential features, and provide you with invaluable tips to sharpen your skills. Get ready to unlock the power of journalistic writing and take your freelance career to new heights . Let's dive in and discover the magic behind compelling stories that captivate readers worldwide.

What is journalistic writing? 📝

Journalistic writing, as the name implies, is the style of writing used by journalists and news media organizations to share news and information about local, national, and global events, issues, and developments with the public.

The main goal of journalistic writing is to provide accurate and objective news coverage. Journalists gather facts, conduct research, and interview sources to present a fair and unbiased account of events. They strive to deliver information clearly, concisely, and interestingly that grabs readers’ attention and helps them understand the subject.

Journalistic writing also encourages public discussion, critical thinking, and informed decision-making. Since journalists present diverse perspectives, analyze complex issues, and investigate misconduct, they empower readers to form opinions and actively engage with the news. Journalistic writing acts as a watchdog, holding institutions and individuals accountable and promoting transparency in society.

Types of journalistic writing 🔥

Different types of journalism writing styles serve unique purposes, from exposing truths to keeping us informed, sparking conversations, and providing meaningful insights into the world around us.

Here are five types of journalistic writing you should know about:

Investigative journalism 🕵️

Investigative journalists are like detectives in the news world. They dive deep into topics, dedicating their time and resources to uncover hidden information, expose corruption, and bring wrongdoing to the surface.

News journalism 🗞️

News journalists are frontline reporters who inform people about the latest happenings. They cover a wide range of topics, from politics and the economy to science and entertainment. They gather facts, interview sources, and present unbiased information objectively and concisely.

Column journalism 📰

In column journalism, writers share their personal opinions and perspectives on various subjects. They offer analysis, commentary, and insights on social, cultural, or political issues. Whether they are experts in their fields or well-known figures with unique voices, their columns provide readers with different standpoints and spark thought-provoking discussions.

Feature writing 🙇

Feature writers take us beyond the basic facts and immerse us in storytelling. They explore human-interest stories, profiles, and in-depth features on specific topics. They also delve into the personal lives, experiences, or achievements of individuals or communities, providing a deeper understanding of the subject matter by using narrative techniques.

Reviews journalism 📖

Reviewers are the guides helping us make informed decisions about the arts. They evaluate and critique films, books, music, theater shows, and more. Through their opinions and assessments, they analyze the quality, impact, and significance of creative works. Review journalism not only helps us choose what to watch, read, or listen to, but it also contributes to cultural conversations and discussions.

Key features of journalistic writing 🔑

Journalistic writing distinguishes itself from other forms of writing through several essential characteristics. And here are a few:

- Accuracy and objectivity: These are of utmost importance. Journalists go to great lengths to gather reliable information, verify sources, and present a balanced perspective. They strive to separate facts from opinions, ensuring readers receive an accurate account of events.

- Timeliness and relevance: Journalists focus on current events and issues that are of interest to the public. They aim to provide up-to-date information, sharing the latest developments and their implications.

- Clarity and conciseness: Journalists use clear and simple language, avoiding complex jargon that might confuse the audience. They use short sentences and paragraphs that enhance readability.

- Inverted pyramid structure: Commonly employed in journalistic writing, this structure places the most important information at the beginning of the article –– in the headline and the first paragraph. Subsequent paragraphs contain supporting details arranged in descending order of significance. By adopting this approach, journalists enable readers to grasp the main points quickly and decide whether to delve deeper into the topic.

- Engagement and impact: Journalists leverage various storytelling techniques, such as vivid descriptions and compelling narratives, to captivate their audience. They incorporate quotes, anecdotes, and human-interest elements to evoke emotions among readers and make the story relatable.

How to write like a journalist: 7 tips 💯

Now that you know the ins and outs of journalistic style and storytelling, let’s explore the best practices to follow during news writing:

1. Use the inverted pyramid structure 🔻

If you’re wondering how to structure and write a news story or article, the answer is simple: Go from the most important to the least important. Start your articles with vital facts, and arrange supporting details in descending order of significance. This structure ensures readers receive essential information even if they don’t read the entire piece.

2. Establish your angle 📐

Before you begin writing , determine the angle or perspective you want to take on the story. Although you should share a neutral opinion, choosing an angle helps you stay focused and deliver a clear message. Consider what makes your story unique or newsworthy, and shape your narrative accordingly.

3. Stick to the facts 🩹

Journalistic writing values accuracy and objectivity. Present information verifiable and supported by credible sources, and avoid personal opinions and biases –– allowing the facts to speak for themselves. Fact-checking is essential to maintain the integrity of your writing.

4. Use quotations to generate credibility 💭

Including quotes from reliable sources adds credibility and depth to your writing. Interview relevant individuals, experts, or eyewitnesses to gather their perspectives and insights. Incorporate their direct quotes to support your narrative and provide first-hand accounts.

5. Write clear and concise sentences 💎

Use straightforward language to effectively communicate your message. Journalism articles typically only include one-to-three sentences per paragraph and should not exceed 20 words per sentence.

6. Edit and revise 💻

Thorough editing is crucial to produce polished and professional journalistic pieces. So once you finish your first draft, invest time on editing and revising your work. Look for grammatical errors, clarity issues, and redundancies. And ensure your writing flows smoothly and maintains a consistent tone.

7. Maintain ethical standards 🏅

You want repeat readers who’ll come back for more from you. And for that, you must keep in mind journalistic principles and share fair, trusting, and accountable pieces. Attribute information to appropriate sources, respect privacy when necessary, and conduct thorough fact-checking.

Write like a pro with Contra 🌟

Mastering the art of journalistic writing is the key to becoming a skilled and impactful freelance writer . By understanding the criticality of thorough research, engaging storytelling, and holding the powerful accountable, you can create compelling news stories that resonate with readers.

And with Contra as your trusted companion, you'll have the tools and resources to refine your journalistic writing skills and take your freelance career to new heights. So don't miss out on the opportunity to write like a pro. Sign up with Contra today, promote your services commission-free, and connect with fellow writers.

Check out Contra for Independents , and join our Slack community to interact with a supportive network of writers, sharing knowledge and learning from each other.

How to Write an Op-Ed: A Guide to Effective Opinion Writing 🖋️

Related articles.

Crafting an Informative Essay: A Comprehensive Guide 📝

What Is Content Writing? Tips to Craft Engaging Content 👀

The 12 Rules Of Grammar Everyone Should Know ✍️

Mastering the White Paper Format: A Step-by-Step Guide 📝

What is a ghostwriter? Everything you need to know 👻

Start your independent journey.

Hire top independents

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Journalism and Journalistic Writing: Introduction

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Journalism is the practice of gathering, recording, verifying, and reporting on information of public importance. Though these general duties have been historically consistent, the particulars of the journalistic process have evolved as the ways information is collected, disseminated, and consumed have changed. Things like the invention of the printing press in the 15 th century, the ratification of the First Amendment in 1791, the completion of the first transatlantic telegraph cable in 1858, the first televised presidential debates in 1960, and more have broadened the ways that journalists write (as well as the ways that their readers read). Today, journalists may perform a number of different roles. They still write traditional text-based pieces, but they may also film documentaries, record podcasts, create photo essays, help run 24-hour TV broadcasts, and keep the news at our fingertips via social media and the internet. Collectively, these various journalistic media help members of the public learn what is happening in the world so they may make informed decisions.

The most important difference between journalism and other forms of non-fiction writing is the idea of objectivity. Journalists are expected to keep an objective mindset at all times as they interview sources, research events, and write and report their stories. Their stories should not aim to persuade their readers but instead to inform. That is not to say you will never find an opinion in a newspaper—rather, journalists must be incredibly mindful of keeping subjectivity to pieces like editorials, columns, and other opinion-based content.

Similarly, journalists devote most of their efforts to working with primary sources, whereas a research paper or another non-fiction piece of writing might frequently consult an encyclopedia, a scholarly article, or another secondary or tertiary source. When a journalist is researching and writing their story, they will often interview a number of individuals—from politicians to the average citizen—to gain insight into what people have experienced, and the quotes journalists collect drive and shape their stories.

The pages in this section aim to provide a brief overview of journalistic practices and standards, such as the ethics of collecting and reporting on information; writing conventions like the inverted pyramid and using Associated Press (AP) Style; and formatting and drafting journalistic content like press releases.

Journalism and Journalistic Writing

These resources provide an overview of journalistic writing with explanations of the most important and most often used elements of journalism and the Associated Press style. This resource, revised according to The Associated Press Stylebook 2012 , offers examples for the general format of AP style. For more information, please consult The Associated Press Stylebook 2012 , 47 th edition.

What Is Literary Journalism?

Carl T. Gossett Jr / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Literary journalism is a form of nonfiction that combines factual reporting with narrative techniques and stylistic strategies traditionally associated with fiction. This form of writing can also be called narrative journalism or new journalism . The term literary journalism is sometimes used interchangeably with creative nonfiction ; more often, however, it is regarded as one type of creative nonfiction.

In his ground-breaking anthology The Literary Journalists , Norman Sims observed that literary journalism "demands immersion in complex, difficult subjects. The voice of the writer surfaces to show that an author is at work."

Highly regarded literary journalists in the U.S. today include John McPhee , Jane Kramer, Mark Singer, and Richard Rhodes. Some notable literary journalists of the past include Stephen Crane, Henry Mayhew , Jack London , George Orwell , and Tom Wolfe.

Characteristics of Literary Journalism

There is not exactly a concrete formula that writers use to craft literary journalism, as there is for other genres, but according to Sims, a few somewhat flexible rules and common features define literary journalism. "Among the shared characteristics of literary journalism are immersion reporting, complicated structures, character development, symbolism , voice , a focus on ordinary people ... and accuracy.

"Literary journalists recognize the need for a consciousness on the page through which the objects in view are filtered. A list of characteristics can be an easier way to define literary journalism than a formal definition or a set of rules. Well, there are some rules, but Mark Kramer used the term 'breakable rules' in an anthology we edited. Among those rules, Kramer included:

- Literary journalists immerse themselves in subjects' worlds...

- Literary journalists work out implicit covenants about accuracy and candor...

- Literary journalists write mostly about routine events.

- Literary journalists develop meaning by building upon the readers' sequential reactions.

... Journalism ties itself to the actual, the confirmed, that which is not simply imagined. ... Literary journalists have adhered to the rules of accuracy—or mostly so—precisely because their work cannot be labeled as journalism if details and characters are imaginary."

Why Literary Journalism Is Not Fiction or Journalism

The term "literary journalism" suggests ties to fiction and journalism, but according to Jan Whitt, literary journalism does not fit neatly into any other category of writing. "Literary journalism is not fiction—the people are real and the events occurred—nor is it journalism in a traditional sense.

"There is interpretation, a personal point of view, and (often) experimentation with structure and chronology. Another essential element of literary journalism is its focus. Rather than emphasizing institutions, literary journalism explores the lives of those who are affected by those institutions."

The Role of the Reader

Because creative nonfiction is so nuanced, the burden of interpreting literary journalism falls on readers. John McPhee, quoted by Sims in "The Art of Literary Journalism," elaborates: "Through dialogue , words, the presentation of the scene, you can turn over the material to the reader. The reader is ninety-some percent of what's creative in creative writing. A writer simply gets things started."

Literary Journalism and the Truth

Literary journalists face a complicated challenge. They must deliver facts and comment on current events in ways that speak to much larger big picture truths about culture, politics, and other major facets of life; literary journalists are, if anything, more tied to authenticity than other journalists. Literary journalism exists for a reason: to start conversations.

Literary Journalism as Nonfiction Prose

Rose Wilder talks about literary journalism as nonfiction prose—informational writing that flows and develops organically like a story—and the strategies that effective writers of this genre employ in The Rediscovered Writings of Rose Wilder Lane, Literary journalist. "As defined by Thomas B. Connery, literary journalism is 'nonfiction printed prose whose verifiable content is shaped and transformed into a story or sketch by use of narrative and rhetorical techniques generally associated with fiction.'

"Through these stories and sketches, authors 'make a statement, or provide an interpretation, about the people and culture depicted.' Norman Sims adds to this definition by suggesting the genre itself allows readers to 'behold others' lives, often set within far clearer contexts than we can bring to our own.'

"He goes on to suggest, 'There is something intrinsically political—and strongly democratic—about literary journalism—something pluralistic, pro-individual, anti-cant, and anti-elite.' Further, as John E. Hartsock points out, the bulk of work that has been considered literary journalism is composed 'largely by professional journalists or those writers whose industrial means of production is to be found in the newspaper and magazine press, thus making them at least for the interim de facto journalists.'"

She concludes, "Common to many definitions of literary journalism is that the work itself should contain some kind of higher truth; the stories themselves may be said to be emblematic of a larger truth."

Background of Literary Journalism

This distinct version of journalism owes its beginnings to the likes of Benjamin Franklin, William Hazlitt, Joseph Pulitzer, and others. "[Benjamin] Franklin's Silence Dogood essays marked his entrance into literary journalism," begins Carla Mulford. "Silence, the persona Franklin adopted, speaks to the form that literary journalism should take—that it should be situated in the ordinary world—even though her background was not typically found in newspaper writing."

Literary journalism as it is now was decades in the making, and it is very much intertwined with the New Journalism movement of the late 20th century. Arthur Krystal speaks to the critical role that essayist William Hazlitt played in refining the genre: "A hundred and fifty years before the New Journalists of the 1960s rubbed our noses in their egos, [William] Hazlitt put himself into his work with a candor that would have been unthinkable a few generations earlier."

Robert Boynton clarifies the relationship between literary journalism and new journalism, two terms that were once separate but are now often used interchangeably. "The phrase 'New Journalism' first appeared in an American context in the 1880s when it was used to describe the blend of sensationalism and crusading journalism—muckraking on behalf of immigrants and the poor—one found in the New York World and other papers... Although it was historically unrelated to [Joseph] Pulitzer's New Journalism, the genre of writing that Lincoln Steffens called 'literary journalism' shared many of its goals."

Boynton goes on to compare literary journalism with editorial policy. "As the city editor of the New York Commercial Advertiser in the 1890s, Steffens made literary journalism—artfully told narrative stories about subjects of concern to the masses—into editorial policy, insisting that the basic goals of the artist and the journalist (subjectivity, honesty, empathy) were the same."

- Boynton, Robert S. The New New Journalism: Conversations with America's Best Nonfiction Writers on Their Craft . Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2007.

- Krystal, Arthur. "Slang-Whanger." The New Yorker, 11 May 2009.

- Lane, Rose Wilder. The Rediscovered Writings of Rose Wilder Lane, Literary Journalist . Edited by Amy Mattson Lauters, University of Missouri Press, 2007.

- Mulford, Carla. “Benjamin Franklin and Transatlantic Literary Journalism.” Transatlantic Literary Studies, 1660-1830 , edited by Eve Tavor Bannet and Susan Manning, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 75–90.

- Sims, Norman. True Stories: A Century of Literary Journalism . 1st ed., Northwestern University Press, 2008.

- Sims, Norman. “The Art of Literary Journalism.” Literary Journalism , edited by Norman Sims and Mark Kramer, Ballantine Books, 1995.

- Sims, Norman. The Literary Journalists . Ballantine Books, 1984.

- Whitt, Jan. Women in American Journalism: A New History . University of Illinois Press, 2008.

- An Introduction to Literary Nonfiction

- Creative Nonfiction

- John McPhee: His Life and Work

- Defining Nonfiction Writing

- Genres in Literature

- literary present (verbs)

- Interior Monologues

- Third-Person Point of View

- Tips on Great Writing: Setting the Scene

- What Is a Synopsis and How Do You Write One?

- A Guide to All Types of Narration, With Examples

- The Essay: History and Definition

- A Look at the Roles Characters Play in Literature

- What Is a Novel? Definition and Characteristics

- Writing Style

- How to write …

- Analysis of Speech

- Storytelling

- Career Development

What Is Journalistic Writing: Purpose, Features, Types, and 10 News Values

- by Anastasiya Yakubovska

- 26.04.2022 02.05.2024

Further in the article, you will learn about what journalistic writing is, its main purpose, what are the features and characteristics of journalistic style, get acquainted with three types of journalism, and at the end of the article, you will find information about how the media select news.

Not so long ago, people could get news only from local newspapers, radio, and television. Nowdays we have access to any information in any format 24/7 (thank you, Internet!).

The ways of obtaining information have changed, but the principles and features of journalism have remained the same.

Table of Contents

What is journalistic writing, and its main purpose.

- Features of Journalistic Writing

How to Write a Journalistic Text: 3 Key Elements

Information genre and its types, analytical genre.

- Artistic-journalistic Types of Journalistic Writing

- 10 News Values

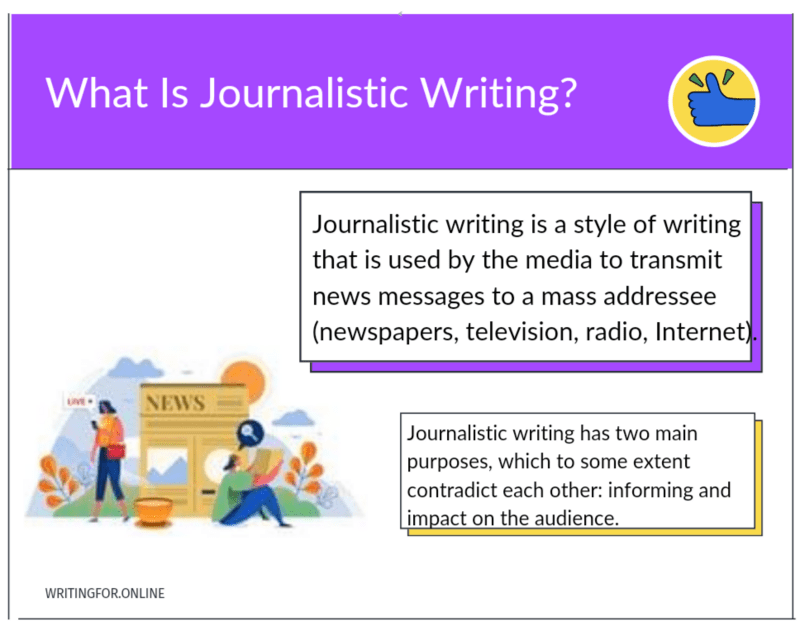

Journalistic writing is a style of writing that is used by the media to transmit news messages to a mass addressee (newspapers, television, radio, Internet).

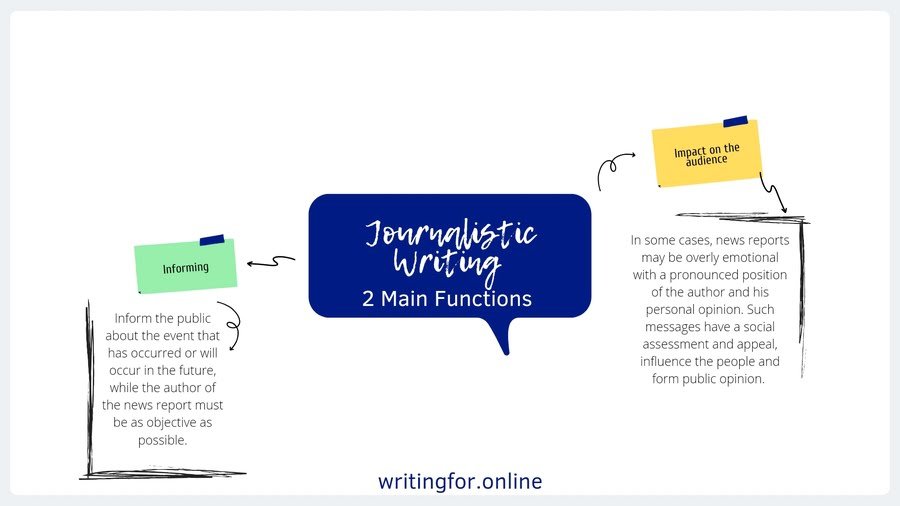

Journalistic writing has two main purposes, which to some extent contradict each other:

- Informing . The main aim of journalistic writing is to inform the public about the event that has occurred or will occur in the future, while the journalist must be as objective as possible.

- Impact on the audience . In some cases, news reports may be overly emotional with a pronounced position of the author and his personal opinion. Such messages have a social assessment and appeal, influence the people and form public opinion.

Features of Journalistic Writing

Journalistic writing has some specific features by which it is easy to identify:

- Informative heading. The news headlines are quite long. From the title, it is clear what will be discussed in the news article.

- The first sentence (paragraph or lead) summarizes the essence of the news.

- The inverted pyramid principle . The priority, value, and usefulness of information decrease from the beginning of the text to its end.

- Sentences and paragraphs are mostly short.

- Lots of specifics and details.

- Readability, simplicity, competent presentation of information.

- Emotionality and evaluation.

- Frequent use of socio-political vocabulary (names of political parties, departments, economic and legal terms, etc.).

- Focus on a mass audience.

- Rhetorical questions, exclamations, and repetitions.

- In addition to the main colloquial (informal) style used in journalism, there are slang and jargon words.

- post “What Is Scientific Writing Style: Characteristics, Types, and Examples”.

- “What Is Business Writing Style: Characteristics, Types, and Examples”.

There are three key components on which any journalistic text is built:

- Lead (or lede). This is the first sentence or main and opening paragraph of the news article. The lead is the “header” of the article, which outlines the main idea of the text. Often the lead is highlighted in a different font or color, usually, its length is from 3 to 5 lines of text.

Lead cannot be ignored. It can be sensational or dramatic, it can reveal the details of an event or briefly describe the news, it can amuse the reader or challenge him.

A news article lead looks like this:

“ Rescue operations are continuing in South Africa in an effort to save the lives of dozens of people who are missing following the floods in KwaZulu-Natal province. With more rain on its way, emergency teams face further peril as they search for survivors. “ bbc.com

2. Citation . 90% of all journalistic investigations are based on interviews or other primary sources. Therefore, it is not surprising that quotes have a special place in news reports.

Read also post “How to Write a Persuasive Article or Essay: Examples of Persuasive Argument”.

3. Brevity and readability. Sentences and paragraphs are short and simple. It does not mean that you will not find long compound sentences in the text. But in most cases – “brevity is the soul of wit.”

In addition, it is important not to overdo with terms. Still, the news articles should be understandable to the mass audience: if you used the term “legal nihilism”, be kind, and explain what it means (p.s.: legal nihilism is the denial of laws and rules/norms of behavior ).

Journalism Genres and Types of Journalistic Writing

There are three genres of journalistic writing:

- Informational : reportage, interview, information note, informational report. The main function is to communicate information: what, where, when, and under what circumstances it happened or will happen.

- Analytical : conversation, review , article, survey, correspondence. The primary function is to influence the public. There are the author’s reasoning, argumentation, analysis of the event, personal conclusions, and assessment of what is happening.

- Artistic-journalistic : essay , feuilleton, pamphlet, profile essay. These genres used to get a figurative, emotional idea of an event or fact.

Let’s take a closer look at each genre.

Note as a Type of Journalistic Writing

A note is a short message about a new event or fact. The main features are the reliability of the fact, novelty, and brevity.

“The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge were accompanied by two of their children as they joined other royals for the Easter Sunday service at Windsor Castle. Prince George was dressed in a dark blue suit like his father while Princess Charlotte’s dress matched her mother Catherine’s light blue outfit . Several of their second cousins, such as Mia Tindall and Savannah and Isla Phillips, also attended. The Queen was not at the service – one of the staples of the family’s year. The 95-year-old monarch, who has been suffering mobility issues recently. was also absent from the traditional Maundy Service last Thursday where special coins were given to 96 men and 96 women .” bbc.com

Read also “How to Write a News Story”.

Reportage is a message from the scene. Features: efficiency, objective coverage of events, the reporter is an eyewitness or participant in what is happening.

Example: television report (live broadcast from the scene), report in the print media after collecting and processing information.

An interview is the receipt of information during a conversation between an interviewer (journalist) and an interviewee.

Examples: informational interviews to collect up-to-date data on an air crash that has occurred (for example, an interview with eyewitnesses); interview investigation; personal interview or interview-portrait.

Informational Report

A report is a chronologically sequential, detailed report of an event.

Example: a report on hostilities, a report on the results of a meeting, a conference, a government or court session.

Conversation or Dialogue

A conversation (dialogue) is a type of interview when a journalist acts not just as an intermediary between the hero and the viewer, but communicates with the interlocutor on an equal footing thanks to his achievements, experience, and professionalism.

Example: TV show with artists.

A review is a critical judgment or discussion that contains an assessment and a brief analysis of a literary work, scientific publication, analysis of a work of art, journalism, etc.

Examples: book review , play review, movie review , TV show review, game review.

An article is a genre of journalism that expresses the author’s reasoned point of view on social processes, on various current events or phenomena.

After reading an analytical article, the reader receives the information he needs and then independently reflects on the issues of interest to him.

The subject of the article is not the event itself, processes, or phenomena, but the consequences they cause.

Examples: an article on the political development of the country, a practical and analytical article on the rise in food prices, a polemical article (dispute) on teaching the basics of Orthodox culture.

Analytical Correspondence

Analytical correspondence is a message that gives information about an event or phenomenon (usually this is one significant fact).

Analytical correspondence may include fragments of a “live” report or a retelling of what is happening. But necessarily in such a message, there is a clarification of the causes of the event or phenomenon, the determination of its value and significance for society, and the prediction of its further development.

The primary source of this genre of journalistic writing is always the author of the publication (correspondent).

Artistic-journalistic Types of Journalistic Writing

Essay : a journalist not only describes a problem, an event, or a portrait of a person, based on factual data but also uses artistic methods of expressiveness.

Examples: a portrait essay about the life of a famous person; historical essays , description of incidents, meetings with people during the author’s travel (essay by A. S. Pushkin “Journey to Arzrum”, 1829).

Feuilleton is a short note, essay, or article of a satirical nature, the main task of which is to ridicule “evil”.

Examples: satirical writers such as M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin, I.A. Ilf, and E.P. Petrov.

A pamphlet is a satirical work or article, the purpose of which is to ridicule certain human vices, to denounce and humiliate a hero who appears to the author as a carrier of a dangerous social evil.

In a pamphlet, the author uses grotesque, hyperbole, irony, and sarcasm.

Examples: “Lettres provinciales” by the French scientist and philosopher Blaise Pascal, “The Grumbled Hive” by the English writer Bernard Mandeville, pamphleteers D.I. Pisarev with the pamphlet “Bees”, A.M. Gorky “The City of the Yellow Devil”, L.M. Leonov “The Shadow of Barbarossa”.

10 News Values

First of all, journalistic writing is associated with the media. A special place in the mass media is occupied by news articles : they are in demand and attract more readers.

Therefore, I propose to pay attention to one very interesting point: how is a news article written, and by what criteria are news “selected”?

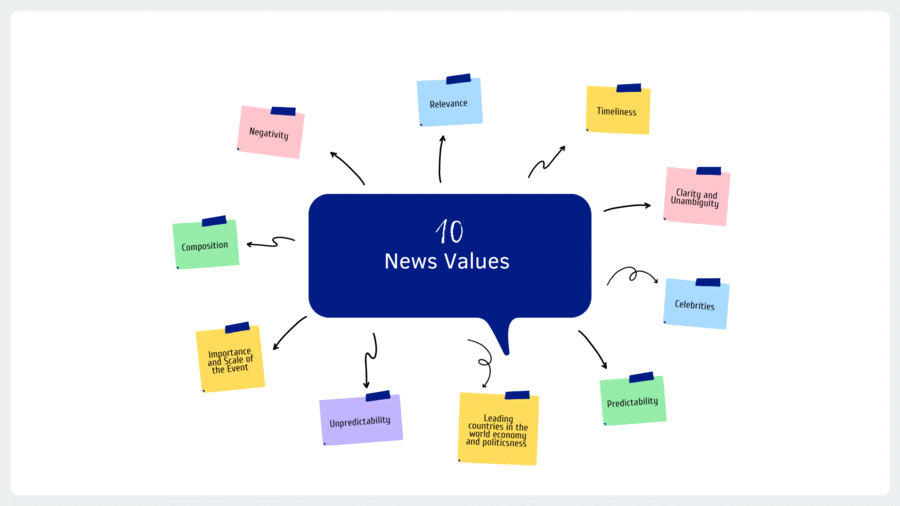

So, 10 news values are:

- Relevance . The news must meet the needs and interests of the audience.

- Timeliness . Event information must be up to date and appear on time. No one will read the election results two weeks after the election.

- Clarity and unambiguity. Simple, understandable news is more accessible to the public, read more often, and is more interesting.

- Predictability . Significant events usually have specific dates (for example, election day, the opening ceremonies of the Olympic Games, the football championship). Therefore, with the approach of such an event, public interest increases, and the news becomes more valuable.

- Unpredictability . On the other hand, unpredictable events and phenomena (natural disasters or crimes) also arouse public interest.

- Importance and scale of the event. War, elections, protests, sports games, and other important events require long and detailed press coverage.

- Composition . Sometimes, to dilute, for example, the negativity of the information flow, the editor selects news reports of the opposite nature: funny cases, love, romance, salvation, animals, adventure, risk, etc.

- Celebrities . News with the participation of politicians, artists, and sportsmen, due to their status and recognition, is more often published in the media and arouses increased interest.

- Leading countries in the world economy and politics. A strike, a natural disaster, or a plane crash in a developed country will immediately hit the media. But about the lack of drinking water in Ethiopia, you can write later.

- Negativity . The “bad” news is more popular.

P. S.: Did you like this post? Share it with your friends, thank you!

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 5 / 5. Vote count: 7

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Journalism Online

Real Information For Real People

What is Literary Journalism: a Guide with Examples

Literary journalism is a genre created with the help of a reporter’s inner voice and employing a writing style based on literary techniques. The journalists working in the genre of literary journalism must be able to use the whole literary arsenal: epithets, impersonations, comparisons, allegories, etc. Thus, literary journalism is similar to fiction. At the same time, it remains journalism , which is the opposite of fiction as it tells a true story. The journalist’s task here is not only to inform us about specific events but also to affect our feelings (mainly aesthetic ones) and explore the details that ordinary journalism overlooks.

Characteristics of literary journalism

Modern journalism is constantly changing, but not all changes are good for it (take fake news proliferating thanks to social media , for instance). Contemporary literary journalism differs from its historic predecessor in the following:

- Literary journalism almost completely lost its unity with literature

- Journalists have stopped relying on the literary features of the language and style

- There are fewer and fewer articles in the genre of literary journalism in modern editions

- Contemporary media has lost the need in literary journalism

- The habits of media consumers today are not sophisticated enough for a revival of literary journalism

The most prominent works of literary journalism

With all this, it’s no surprise that we need to go back in time to find worthy examples of literary journalism. Fortunately, it wasn’t until the 1970-s that literary journalism came to an end, so here are 4 great works of the genre that are worth every minute of your attention.

Mark Twain, The Innocents Abroad (1869)

Mark Twain studied journalism from the age of 12 and until the end of his life. It brought him his first glory and a pseudonym and made him a writer. In 1867, Twain (as a correspondent of the newspaper Daily Alta California , San Francisco) went on a sea voyage to Europe, the Middle East, and Egypt. His reports and travel records turned into the book The Innocents Abroad , which made him famous all over the world.

In some sense, American journalism came out of letters that served as an important source of information about life in the colonies. The newspaper has long been characterized by an epistolary subjectivity, and Twain’s book recalls the times when no one thought that neutrality would one day become one of the hallmarks of the “right” journalism.

Of course, Twain’s travel around the Old World was a journey not only through geography but also through the history that Twain resolutely refused to worship. Sometimes it’s funny, sometimes not too much, but the more valuable are the lyrical and sublime notes that sound when Twain-the-narrator is truly captivated by something.

John Hersey, Hiroshima (1946)

John Hersey was a war correspondent and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize for his debut story A Bell for Adano . As a reporter of The New Yorker , he was one of the first journalists from the USA who came to Hiroshima to describe the consequences of the atomic bombing.

Starting with where two doctors, two priests, a seamstress, and a plant employee were and what they were doing at exactly 08:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, when the bomb exploded over Hiroshima, Hersey describes the year they lived after that. Hersey’s uniform and detached tone seems to be the only appropriate medium in relation to what one would call indescribable and inexpressible. Without allowing himself sentimentality, admiring horrors, or obvious partiality, he doesn’t miss any of the details that add up to a horrible and magnificent picture.

Hiroshima became a sensation due to the formidable brevity of the author’s prose, which tried to give the reader the most explicit (and the most complete) idea of what happened for the first time in mankind’s history

Truman Capote, “In Cold Blood” (1965)

Truman Capote turned to journalism as a young writer looking for a new form of self-expression. He read an article about the murder of the family of a farmer Herbert Clutter in Holcomb City (Kansas) in the newspaper and went there to collect the material. His original idea was to write about how a brutal murder influenced the life of the quiet backwoods. The killers were caught, and Capote decided to use their confessions in his book. He finished it only after the killers were hanged. This way, the six-year story got the finale.

In Cold Blood was published in “The New Yorker” in 1965. Next year it was released as a book that became the benchmark of true crime and a super bestseller. “In Cold Blood” includes:

- A stylistic brilliance.

- Inexorable footsteps of doom destroying both innocent and guilty.

- The horror hidden in a person and waiting for a chance to break out.

Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968)

Tomas Wolfe is one of the key figures of literary journalism. Mainly due to his creative and, so to speak, production efforts, “the new journalism” became an essential part of American culture and drew close attention (both critical and academic).

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test became one of the hallmarks of this type of journalism with its focus on aesthetic expressiveness (along with documentary authenticity). This is a story about the writer Ken Kesey and his friends and associates’ community, “Merry Pranksters”, who spread the idea of the benefits of expanding consciousness.

Wolfe decided to plunge into the “subjective reality” of the characters and their adventures. To convey them to the reader, he had to “squeeze” the English language: Wolfe changes prose to poetry , dives into the stream of consciousness, and mocks the traditional punctuation. In general, he does just about everything to make a crazy carnival come to life on the pages of his book (without actually participating in it). Compare that with gonzo journalism by Hunter S. Thompson , the author of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas which draws upon some similar themes.

The book’s main part is devoted to the journey of the “pranksters” on a psychedelic propaganda bus and the “acid tests” themselves, which were actually parties where a lot of people took LSD. Wolfe had to use different sources of information to reconstruct these events, and it’s hard to believe that he didn’t experience any of them himself. Yet, no matter how bright his book shines and how much freedom it shows, Wolfe makes it clear that he’s talking about a doomed project and an ending era.

You might also like

OUT WITH THE OLD, IN WITH THE NEWS

Zach Fenno on the Art of Tennis: The Perfect Blend of Physicality and Strategy

How are Creativity and Innovation Related?

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- IFCN Grants

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

The Pyramid of Journalism Competence: what journalists need to know

What does a journalist need to know?

What defines “competence” in journalism?

When you graduate from a journalism school, what should you know how to do?

In the digital age, the answers to those questions are more important than ever. For more than three decades now, they have been near the center of conversation and debate at Poynter. Before we could figure out what to teach, we needed to understand – in the public interest – what journalists needed to learn.

This process was energized in 1997 by a call to action from Tom Rosenstiel, one of the leaders of a group called the Committee of Concerned Journalists. Over the next two years, the committee conducted “21 public forums attended by 3,000 people and involving testimony from more than 300 journalists,” according to the book “The Elements of Journalism” by Rosenstiel and Bill Kovach.

Poynter was asked to conduct one of those forums on a most challenging topic: What does it mean to be a competent journalist? And so we did.

In preparation for this conference on Feb. 26, 1998, the Poynter faculty, under my direction, built an edifice we came to call the Pyramid of Competence. This structure comprised 10 blocks. The cornerstones were news judgment and reporting . The foundation also included language and analysis . The central stone was technology , between audio-visual knowledge and numeracy . Closer to the top were civic and cultural literacy. At the apex was ethics .

The pyramid has had an interesting history, inside and outside the institute. Its most serious consideration came from the accrediting council of AEJMC. At a time when the standards for accreditation were under review, leaders such as Trevor Brown, dean at Indiana University, thought the ideas behind the pyramid would lead to a clearer articulation of educational “outcomes,” what students should expect to get out of a journalism education.

Much has changed in the world of journalism since the pyramid was constructed. New media platforms have been invented; business models have collapsed; arguments about who is a journalist abound. Pyramids may be tombs for dead kings, but they have a way of hanging around – for a long time.

What you are about to experience is the most up-to-date version of the Pyramid of Competence. It contains 10 sections, one for each of the competencies. It begins with a description and a definition, followed by a list of imagined courses that could impart that competency, topped off with an example of an essay that could be used to cultivate that area of journalistic knowledge.

You will find in these descriptions language that, we hope, is contemporary, including words such as “curation,” “aggregation,” and “data visualization,” language that was not part of journalism study when the pyramid was first created.

There were some key questions that were not resolved when the pyramid was built — and that remain unresolved. The big question is this: How many of these competencies should reside in any individual journalist? Or is it possible and desirable to imagine that these competencies can reside across a news organization, expressed in the work of specialists? In short, should the writer of the story also know how to develop an algorithm of data analysis and also be able to design a page?

Our tentative answer (perhaps I should restate that as “my” tentative answer) is that versatility is one of the most important virtues in contemporary journalism. That does not mean that the journalist need be an expert in all these areas. But it requires the journalist to be able to converse with colleagues in these areas across disciplines and “without an accent.” Competence is not a synonym for expertise.

We invite you to climb the Pyramid of Competence. Let us know how the world of journalism looks when you reach the top.

News Judgment

This competence resides in every academic discipline but is made manifest in powerful ways in the study and practice of journalism.

On any given day – or minute – the journalist (especially the editor) sorts through the events and concerns of the moment, hoping to determine which of them deserves the special attention of general and particular audiences.

Decisions on what to publish are based on two broad categories, expressed here in the form of questions:

• Is it important?

• Is it interesting?

There are, of course, important things that may not be interesting – a fluctuation in the money supply. Interesting things – celebrity divorces – may not be important. But on many days, the two categories will converge:

• The attacks of 9/11.

• The oil spill in the Gulf.

• The collapse of the economy in 2008.

• The election of the first African-American president.

• The rate of suicide of soldiers returned from war.

All these are terribly interesting and crucially important, relevant at some level to every person on the planet. Such stories deserve a standing at the top of the news ladder.

But these choices are obvious. The importance of news is relative. On some days news is slow so that an alligator attack across the state gets more attention than it may deserve. Then there are big news days when stories elbow each other for prominence. A significant tropical storm that hit Tampa Bay in 2001 got much less attention than usual because it happened the week of the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

An editor with rich experience and refined news judgment will be able to see important news that is invisible to others. This is an invaluable civic, democratic, and commercial power. An expert is paying attention.

[News judgment describes the cognitive acts of understanding what matters: what is most important or most interesting. It is exercised in such practices as the generation of story ideas by reporters; by selection and play of stories by news editors; by the curation and aggregation of items on the Internet.]

Courses that would enrich news judgment

• Reporting I & II

• Advanced Reporting

• Editing I & II

• Investigative Reporting

• Computer-Assisted Reporting

• Work on School Publications

• Internships at News Organizations

• Media & Society

• News & Media Literacy

• Understanding Social Networks

An essay to read that would enhance news judgment

“From Politics to Human Interest,” by Helen MacGill Hughes

Reporting and Evidence

If news judgment sits as one cornerstone of the pyramid of competence, reporting serves as the other. In an academic context, reporting represents the gathering, verification, and distribution of evidence.

• Why is the price of gasoline so high?

• Where is the balance between personal privacy and national security?

• What were the root causes for the attacks on America on 9/11?

• Is Apple exploiting Chinese workers?

The answers to these questions cannot be simply asserted. Reporters and other news researchers must go out, gather evidence from reliable sources, check it out, and present it in the public interest.

Journalists of various types learn different methods of hunting and gathering information: documents (such as court records), minutes or notes taken at meetings, chronologies, interviews, public records, direct observation, participant observation, immersion reporting, data analysis, participation in social networks – these are just some of the methods journalists use to gain a meaningful picture of the world.

Science, law, economics, ethnography – each discipline offers a distinctive perspective on what constitutes good evidence. The big word for this in philosophy is “epistemology,” the philosophy of knowing. In journalism the questions might go simply, “How do reporters know?”

Academic study takes this to another level, “How do they KNOW what they know?”

[Reporting and Evidence represent the process and products of research.

The traditional methods of reporting all involve finding things out and checking them out, what Kovach and Rosenstiel describe as a discipline of verification, not assertion. Evidence involves tests of reliability, often based on knowledge of the sources. Reporters gather evidence, which is then tested against the standards of editors. Investigations, often to expose wrongdoing, require different standards of evidence than traditional reporting. Forms of evidence are gathered by photographers and documentary videographers, and, most recently, by computer-assisted and data-management efforts. Since standards of evidence differ in various disciplines, knowledge of a field outside of journalism – law, economics, biology – enrich all acts of reporting.]

Courses that would enrich reporting and evidence

• Public Service Reporting

• Fact-Checking and Verification

• Scientific Method

• Ethnography

• Rules of Evidence

• Philosophy of Knowledge

• Quantitative Methods

An essay to read that would enhance reporting and evidence

“Getting the Story in Vietnam,” by David Halberstam

Language and Storytelling

The pyramid of journalism competence is built upon a foundation. One of its blocks is the effective use of language to express reports, stories, and other appropriate forms of communication.

Canadian scholar Stuart Adam argues that, at heart, journalists are a type of author, the work existing on a spectrum that extends from the civic to the literary. Competent journalists exhibit versatility in this area, demonstrating the capacity to write in different genres and for different media – long or short, fast or slow – for a variety of audiences and platforms.

A key distinction is between reports and stories. At the heart of journalism remains the neutral, unbiased report, still grounded in the traditional questions of who, what, when, where, why, and how. Using what semanticist S.I. Hayakawa termed “unloaded” language, the reporter sorts through the evidence to provide audiences with good information in the public interest.

The yang to the yin of the report is the story. The product of story is not information, but experience, and the effect is not just actionable knowledge, but empathy. This is created by the transformation of elements of reporting into narrative, so that who becomes character, what becomes scenic action, when becomes chronology, where becomes setting, why (always the most difficult) becomes motive, and how becomes how it happened.

There are forms of reportage and narrative that are expressed via other media and methods (we’ll get to these). But the written word on the page is the basis for all others.

[Language and Storytelling come to the journalist through normal intellectual development, but are enhanced by the practice of authorship, the study of language (including a foreign language), experimentation with a variety of narrative strategies in multiple genres across media platforms.]

Courses that would enrich language and storytelling

• Elements of Language

• Composition I & II

• Surveys of English and American Literature

• Nonfiction Narrative

• Theories of Narrative

• Foreign Language

An essay to read that would enhance language and storytelling

“Politics and the English Language,” by George Orwell

Analysis and Interpretation

To quote the 1947 Hutchins Commission report , “It is no longer enough to report the fact truthfully. It is now necessary to report the truth about the fact.” Context, meaning, trends, relationships, tensions all must appear on the radar screen of the discerning journalist. Some scoops are conceptual.

“Critical thinking” has become too vague a concept to describe this capacity. This form of literacy falls somewhere between analysis and interpretation and is often conveyed in arguments, commentary, opinion, and investigative reporting.

• How does a sexual abuse scandal at Penn State University resemble the one inside the Catholic Church?

• In what sense has global economics given us a “flat” world?

• Can the events of 9/11/2001 really be traced back to political and religious forces in Egypt, dating back to 1948?

The ability to see such questions, to analyze them and derive meaning from them, comes from the exercise of cognitive muscles toned in the gymnasia of traditional academic disciplines, from studies as diverse as evolutionary biology to anthropology to calculus to world literature.

Formal journalism study that is too narrow (with too many courses specifically about journalism) may result in short-term gains at the expense of long-term progress in a career. The aspiring journalist needs the enrichment of the Arts, Humanities, and Sciences; it is from those deep wells that the competent journalist can draw.

[Analysis and Interpretation describe the ability of the journalist to make sense of the often jumbled and chaotic movements of the day. In a deadline story or in a book, the journalist gains audience and credibility when he or she can discern trends, patterns, a higher or deeper level of meaning. This has no agreed-up name, but comes under phrases such as “sense-making,” “gaining altitude,” “conceptual scoops,” and “collateral journalism.”]

Courses that would enrich analysis and interpretation

• Myth and Literature

• History of Science

• Abnormal Psychology

• Quantum Physics

• Principles of Economy

• Art Appreciation

• Technology and Society

An essay to read that would enhance analysis and interpretation

“The Dark Continent of American Journalism,” by James W. Carey

Innumeracy can be as bad as illiteracy in a profession – especially one such as journalism that describes its members as watchdogs in the public interest. Corruption of power – by banks or governments – often involves the abuse of numbers. The ability to work with numbers – especially for those with a natural word orientation – enriches reporting capacity exponentially.

[If you do not know the meaning of the metaphor “exponential,” you may have some work to do.]

Let’s take the case of the young reporter who asks a state commissioner of education why the budget for pre-school education was cut last year. “Check your facts, please,” says the commissioner. “Our budget increased by one percent,” and that’s what the reporter put in a draft of the story. Until a more numerate editor asked “What was the inflation rate last year?” Turned out, it was 3 percent. So that in real dollars, the value of money to be spent on education did, indeed, decline.

More and more, the numbers tell the story. The analysis and presentation of numbers – described in the jargon “big data” – adds in the reporting of such diverse topics as to whether state lottery revenues actually contribute to education, to the probable winners in an electoral cycle, to whether or not a certain economic policy is discriminatory, to the workings of a successful fantasy football league.

A lack of numeracy has been described as the “dark hole” of journalism competence. It need not be that way. In fact, the analysis of numbers often reveals a secret part of the world that can be explored by reporters and storytellers. Reporter Mara Hvistendahl knew that in normal circumstances 105 boy babies are born for every 100 girl babies. Her research discovered that the Chinese port city of Lianyungang has a gender ratio for children under five of 163 boys for every 100 girls. Armed with such numbers she set off for Asia to report their human consequences.

[Numeracy is most often the ability to use computation skills (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) to understand the world. For some stories, higher skills are necessary, including the ability to report for numbers, understand probability and statistics, and work with basic economic concepts – such as adjusting for inflation. Journalists also make routine decisions about what information to include in print stories, and which ones to illustrate graphically.]

Courses that would enrich numeracy

• Probability and Statistics

• College Level Algebra (and more advanced courses in mathematics)

• Math for Journalists

• Econometrics

• Quantitative Social Science Methodology

An essay to read that would enhance numeracy

“The Scientific Way,” by Victor Cohn

It may be obvious to state the importance of technological literacy in the digital age, but consider the complexity of this: that many students raised with the Internet may be, in important ways, more technologically literate than their professors. Universities must grapple with who has the capacity to teach students about technology in the interests of journalism and democracy.

The key for journalism competence is to understand technology in two ways:

1. How technology undergirds changing forms of journalism – the way that the telegraph liberated news from geography and transportation.

2. How technology acts as a force that changes society – for better and worse – thus demanding coverage in the news itself.

The competent journalist must be prepared to work successfully in a variety of media platforms, from print to video to digital to mobile – including forms that have not yet been invented. Just as “computer assisted reporting” once enriched investigative work, there is now new potential in forms of computer programming, data analysis and display.

Technological innovations can be disruptive, placing demands on the competent journalist to manage change, and often to embrace it, but it does not require achieving escape velocity from enduring values and traditions.

What is called for here is neither technophilia nor phobia, but a techno-realism that recognizes the gains and compensates for the losses brought by new technologies.

[Technology literacy includes abilities in word processing, search and research functions, social networking, blogging, programming, mobile applications, data analysis and display, aggregation and curation.]

Courses that would enrich technological competency

• History of Technology

• Technology, Community, Culture

• Computer Science

• Introduction to Programming

• Introduction to Blogging

• Data Analysis and Display

An essay to read that would enhance technological literacy

“Into the Electronic Millennium,” by Sven Birkerts

Audio-Visual

Long before the invention of the written word, humans created forms of storytelling that took care of their informational and aspirational needs. Drawings on cave walls in France tell stories of the hunt and of the gods. Oral poetry – often recited to music – defined cultures and described heroes and enemies.

The audio and visual have evolved as crucial modes of journalism expression, a movement magnified by the Internet.

While there remains a place for journalism specialization, versatility is a virtue of the day. The backpack journalist collects photos, videos, sound, and writes texts. The cell phone is a tool that allows the collection of all these elements in the palm of the hand.

But one key feature of favorite technologies is their design. The world’s great designers have turned their attention from newspapers and magazines to websites and blogs to mobile technologies such as the iPhone and iPad. Audio and visual elements enrich everything from news navigation to data display to storytelling in multi-media and multiple media forms.

Radio remains a powerful medium for journalism worldwide, and famous networks such as the BBC and NPR now use text and visual elements on their websites.

This is one literacy in which collaboration is crucial and the best work undertaken comes from the marriage of writing, editing, and design.

[Audio-Visual literacy is expressed through photography and video, design and illustration, the use of color, creation of slide shows and other multi-media productions, the use of natural sound, and the use of music, when appropriate.]

Courses that would enrich audio-visual literacy

• History of Western Art

• 20th Century Art (Modern & Post-Modern)

• Theories of Color

• History of Photography

• Art and Craft of Photo Composition

• Multi-Media Reporting and Editing

• Music Appreciation

• Selected Masters of Classical Music

• Musical Performance (any instrument, including voice)

An essay to read that would enhance audio-visual literacy

“In Plato’s Cave,” by Susan Sontag

Civic literacy

The teaching of civics in American public or private schools has never been known as ideal – even in decades past. Civic literacy requires basic knowledge of such things as the separation of powers, the three branches of government, and how a bill becomes a law. It is enriched by a knowledge of American history and familiarity with the foundational documents of democracy, including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and Bill of Rights, famous Supreme Court Decisions, the Emancipation Proclamation, etc.

Much of what journalists will learn about civics will come from the experience of covering beats such as city hall, the school board, and criminal courts. All this is necessary but insufficient to the achievement of civic literacy. In addition to official sources of power and influence, there are countless informal ones: the barber shop, the nail salon, the diner, the soccer field, the church choir – sources of social capital where the pulse of practical democracy can be taken.

[Civic Literacy requires knowledge of government, politics, social capital, social contracts, power, history, public life, civic culture, how audiences can be measured for public opinion, how media influence the constituent groups in society.]

Courses that would enrich civic literacy

• Introduction to U.S. Government

• Comparative Government and Politics

• American History

• World History

• Introduction to Democratic Theory

• Lippman, Dewey, and the American Social Contract

• Origins and Structures of Social Capital

• Introduction to Constitutional Law

An essay to read to enhance civic literacy

“Bowling Alone,” by Robert Putnam

Cultural Literacy

Professor James Carey would often argue that news and other forms of journalism were expressions of culture, increasing their value as objects of scholarly study and practical investigation. One of the purposes of journalism is to reflect the constituent elements within a society so that they can see each other and converse across differences.

It is not unusual for certain expressions of journalism to emanate from a particular cultural point of view. In America, in spite of changing demographics, that mainstream perspective often reflects the interests and beliefs of the white governing class, residing in centers of power such as New York, Washington D.C., and Los Angeles.

Recognizing the potential for self-interest and bias, journalists seek a cultural competence that allows them to operate with people and in places that are unfamiliar. To use the academic jargon of the day, they must learn to see The Other.

Often this is most easily understood and accounted for when journalists serve as foreign correspondents. When they travel to Asia, the Middle East, or South America, they may prepare themselves by studying the language and culture of the new setting. But the same learning across difference must occur when an American reporter travels to another part of the country.

In many towns, differences must be learned when traveling from one end of a street to the other.

[Cultural Literacy requires knowledge of and sensitivity to cultural differences, whether they are expressed by race, social class, ethnicity, religion, gender, or sexual orientation. Key issues related to cultural literacy include assimilation and diversity, multi-culturalism, international understanding, and foreign languages.]

Courses that would enrich cultural literacy

• Introduction to Anthropology

• Gender Studies

• Class and Power in American Society

• From Slavery to Freedom

• Race and Culture in America

• Comparative Culture and Literature

An essay to read to enhance cultural literacy

“Of Our Spiritual Strivings,” by W.E.B. DuBois

Mission and Purpose

From the cornerstones of news judgment and reporting, up from the foundational blocks, through technology, and beyond civic and cultural literacy, the pyramid of competence reaches a pinnacle with an understanding of mission and purpose.

Journalism is a profession that often resides within a business, an enterprise that creates wealth that can be used to commit better journalism. While there has always been – and always will be – a tension between professional and commercial interests, all involved in the enterprise must achieve a clear vision of mission and purpose.

The exercise of craft without purpose can become irrelevant or even dangerous. When journalists operate in the public interest, they often commit their best work. A sense of purpose grows out of the practice of journalism, but also out of academic study, which includes familiarity with the canons of ethics, law, journalism history, standards and practices, and the study of principles of democracy, theories of liberty and justice, conversations about the social contract.

[Mission and Purpose derive from both practice and study. Sources of knowledge include media ethics and law, the First Amendment, the history of journalism (with special attention to its noble and heroic characters), principles of democracy, and a working knowledge of the role journalism plays in communities and municipalities.]

Courses that would enrich a sense of mission and purpose

• Studies in the First Amendment

• History of Journalism

• Media and Journalism Ethics

• Applied Ethics

• Principles of Democracy

• Theories of Justice

• Advanced Literary Studies

• Theories of the Press

• Civic Journalism

• Journalism and Society