Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

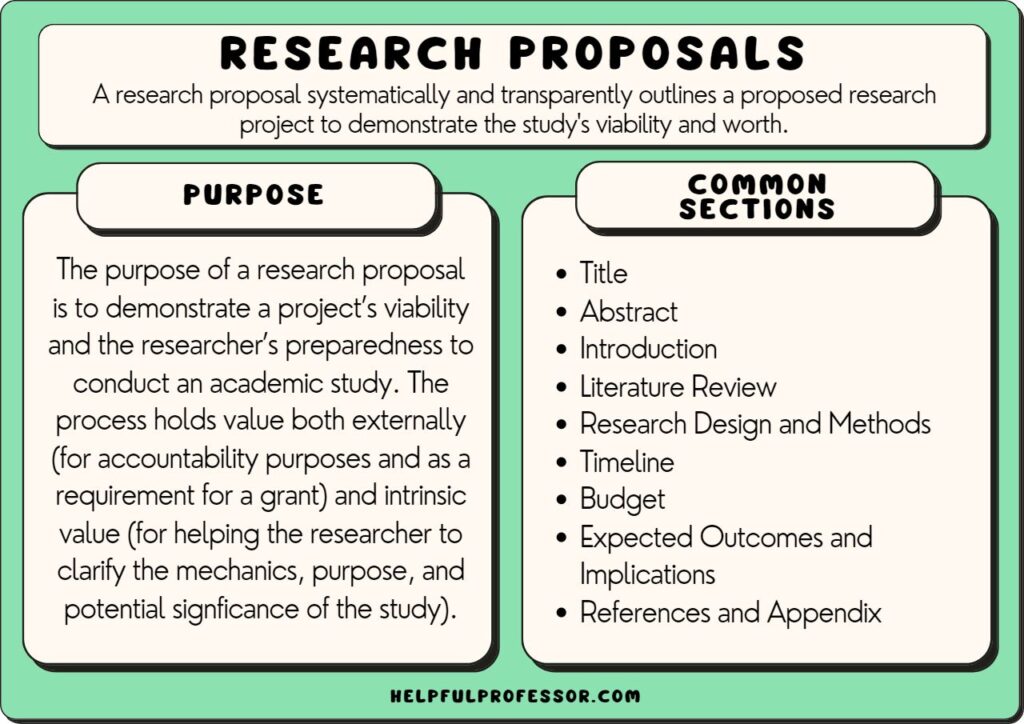

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

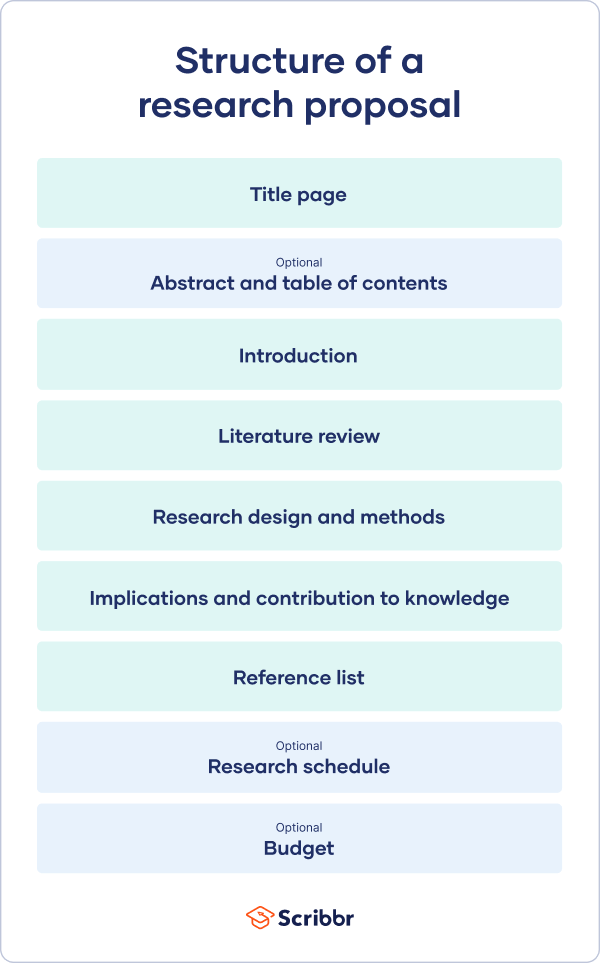

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide...

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Steps in Developing a Research Proposal

Learning objectives.

- Identify the steps in developing a research proposal.

- Choose a topic and formulate a research question and working thesis.

- Develop a research proposal.

Writing a good research paper takes time, thought, and effort. Although this assignment is challenging, it is manageable. Focusing on one step at a time will help you develop a thoughtful, informative, well-supported research paper.

Your first step is to choose a topic and then to develop research questions, a working thesis, and a written research proposal. Set aside adequate time for this part of the process. Fully exploring ideas will help you build a solid foundation for your paper.

Choosing a Topic

When you choose a topic for a research paper, you are making a major commitment. Your choice will help determine whether you enjoy the lengthy process of research and writing—and whether your final paper fulfills the assignment requirements. If you choose your topic hastily, you may later find it difficult to work with your topic. By taking your time and choosing carefully, you can ensure that this assignment is not only challenging but also rewarding.

Writers understand the importance of choosing a topic that fulfills the assignment requirements and fits the assignment’s purpose and audience. (For more information about purpose and audience, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .) Choosing a topic that interests you is also crucial. You instructor may provide a list of suggested topics or ask that you develop a topic on your own. In either case, try to identify topics that genuinely interest you.

After identifying potential topic ideas, you will need to evaluate your ideas and choose one topic to pursue. Will you be able to find enough information about the topic? Can you develop a paper about this topic that presents and supports your original ideas? Is the topic too broad or too narrow for the scope of the assignment? If so, can you modify it so it is more manageable? You will ask these questions during this preliminary phase of the research process.

Identifying Potential Topics

Sometimes, your instructor may provide a list of suggested topics. If so, you may benefit from identifying several possibilities before committing to one idea. It is important to know how to narrow down your ideas into a concise, manageable thesis. You may also use the list as a starting point to help you identify additional, related topics. Discussing your ideas with your instructor will help ensure that you choose a manageable topic that fits the requirements of the assignment.

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Jorge, who is studying health care administration, as he prepares a research paper. You will also plan, research, and draft your own research paper.

Jorge was assigned to write a research paper on health and the media for an introductory course in health care. Although a general topic was selected for the students, Jorge had to decide which specific issues interested him. He brainstormed a list of possibilities.

If you are writing a research paper for a specialized course, look back through your notes and course activities. Identify reading assignments and class discussions that especially engaged you. Doing so can help you identify topics to pursue.

- Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in the news

- Sexual education programs

- Hollywood and eating disorders

- Americans’ access to public health information

- Media portrayal of health care reform bill

- Depictions of drugs on television

- The effect of the Internet on mental health

- Popularized diets (such as low-carbohydrate diets)

- Fear of pandemics (bird flu, HINI, SARS)

- Electronic entertainment and obesity

- Advertisements for prescription drugs

- Public education and disease prevention

Set a timer for five minutes. Use brainstorming or idea mapping to create a list of topics you would be interested in researching for a paper about the influence of the Internet on social networking. Do you closely follow the media coverage of a particular website, such as Twitter? Would you like to learn more about a certain industry, such as online dating? Which social networking sites do you and your friends use? List as many ideas related to this topic as you can.

Narrowing Your Topic

Once you have a list of potential topics, you will need to choose one as the focus of your essay. You will also need to narrow your topic. Most writers find that the topics they listed during brainstorming or idea mapping are broad—too broad for the scope of the assignment. Working with an overly broad topic, such as sexual education programs or popularized diets, can be frustrating and overwhelming. Each topic has so many facets that it would be impossible to cover them all in a college research paper. However, more specific choices, such as the pros and cons of sexual education in kids’ television programs or the physical effects of the South Beach diet, are specific enough to write about without being too narrow to sustain an entire research paper.

A good research paper provides focused, in-depth information and analysis. If your topic is too broad, you will find it difficult to do more than skim the surface when you research it and write about it. Narrowing your focus is essential to making your topic manageable. To narrow your focus, explore your topic in writing, conduct preliminary research, and discuss both the topic and the research with others.

Exploring Your Topic in Writing

“How am I supposed to narrow my topic when I haven’t even begun researching yet?” In fact, you may already know more than you realize. Review your list and identify your top two or three topics. Set aside some time to explore each one through freewriting. (For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .) Simply taking the time to focus on your topic may yield fresh angles.

Jorge knew that he was especially interested in the topic of diet fads, but he also knew that it was much too broad for his assignment. He used freewriting to explore his thoughts so he could narrow his topic. Read Jorge’s ideas.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Another way writers may focus a topic is to conduct preliminary research . Like freewriting, exploratory reading can help you identify interesting angles. Surfing the web and browsing through newspaper and magazine articles are good ways to start. Find out what people are saying about your topic on blogs and online discussion groups. Discussing your topic with others can also inspire you. Talk about your ideas with your classmates, your friends, or your instructor.

Jorge’s freewriting exercise helped him realize that the assigned topic of health and the media intersected with a few of his interests—diet, nutrition, and obesity. Preliminary online research and discussions with his classmates strengthened his impression that many people are confused or misled by media coverage of these subjects.

Jorge decided to focus his paper on a topic that had garnered a great deal of media attention—low-carbohydrate diets. He wanted to find out whether low-carbohydrate diets were as effective as their proponents claimed.

Writing at Work

At work, you may need to research a topic quickly to find general information. This information can be useful in understanding trends in a given industry or generating competition. For example, a company may research a competitor’s prices and use the information when pricing their own product. You may find it useful to skim a variety of reliable sources and take notes on your findings.

The reliability of online sources varies greatly. In this exploratory phase of your research, you do not need to evaluate sources as closely as you will later. However, use common sense as you refine your paper topic. If you read a fascinating blog comment that gives you a new idea for your paper, be sure to check out other, more reliable sources as well to make sure the idea is worth pursuing.

Review the list of topics you created in Note 11.18 “Exercise 1” and identify two or three topics you would like to explore further. For each of these topics, spend five to ten minutes writing about the topic without stopping. Then review your writing to identify possible areas of focus.

Set aside time to conduct preliminary research about your potential topics. Then choose a topic to pursue for your research paper.

Collaboration

Please share your topic list with a classmate. Select one or two topics on his or her list that you would like to learn more about and return it to him or her. Discuss why you found the topics interesting, and learn which of your topics your classmate selected and why.

A Plan for Research

Your freewriting and preliminary research have helped you choose a focused, manageable topic for your research paper. To work with your topic successfully, you will need to determine what exactly you want to learn about it—and later, what you want to say about it. Before you begin conducting in-depth research, you will further define your focus by developing a research question , a working thesis, and a research proposal.

Formulating a Research Question

In forming a research question, you are setting a goal for your research. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper—but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer.

To determine your research question, review the freewriting you completed earlier. Skim through books, articles, and websites and list the questions you have. (You may wish to use the 5WH strategy to help you formulate questions. See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information about 5WH questions.) Include simple, factual questions and more complex questions that would require analysis and interpretation. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several subquestions that you will need to research to answer your main question.

Here are the research questions Jorge will use to focus his research. Notice that his main research question has no obvious, straightforward answer. Jorge will need to research his subquestions, which address narrower topics, to answer his main question.

Using the topic you selected in Note 11.24 “Exercise 2” , write your main research question and at least four to five subquestions. Check that your main research question is appropriately complex for your assignment.

Constructing a Working ThesIs

A working thesis concisely states a writer’s initial answer to the main research question. It does not merely state a fact or present a subjective opinion. Instead, it expresses a debatable idea or claim that you hope to prove through additional research. Your working thesis is called a working thesis for a reason—it is subject to change. As you learn more about your topic, you may change your thinking in light of your research findings. Let your working thesis serve as a guide to your research, but do not be afraid to modify it based on what you learn.

Jorge began his research with a strong point of view based on his preliminary writing and research. Read his working thesis statement, which presents the point he will argue. Notice how it states Jorge’s tentative answer to his research question.

One way to determine your working thesis is to consider how you would complete sentences such as I believe or My opinion is . However, keep in mind that academic writing generally does not use first-person pronouns. These statements are useful starting points, but formal research papers use an objective voice.

Write a working thesis statement that presents your preliminary answer to the research question you wrote in Note 11.27 “Exercise 3” . Check that your working thesis statement presents an idea or claim that could be supported or refuted by evidence from research.

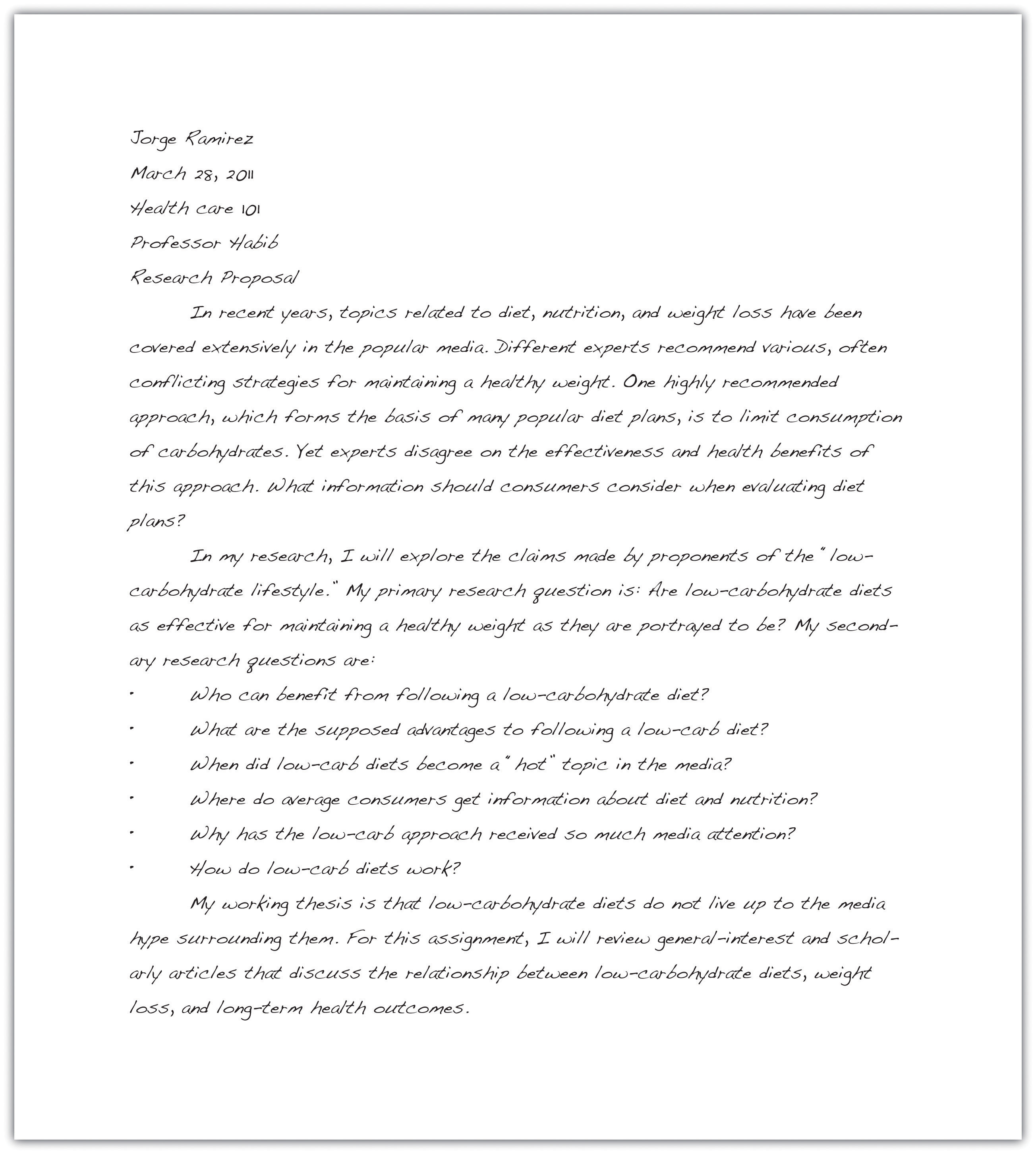

Creating a Research Proposal

A research proposal is a brief document—no more than one typed page—that summarizes the preliminary work you have completed. Your purpose in writing it is to formalize your plan for research and present it to your instructor for feedback. In your research proposal, you will present your main research question, related subquestions, and working thesis. You will also briefly discuss the value of researching this topic and indicate how you plan to gather information.

When Jorge began drafting his research proposal, he realized that he had already created most of the pieces he needed. However, he knew he also had to explain how his research would be relevant to other future health care professionals. In addition, he wanted to form a general plan for doing the research and identifying potentially useful sources. Read Jorge’s research proposal.

Before you begin a new project at work, you may have to develop a project summary document that states the purpose of the project, explains why it would be a wise use of company resources, and briefly outlines the steps involved in completing the project. This type of document is similar to a research proposal. Both documents define and limit a project, explain its value, discuss how to proceed, and identify what resources you will use.

Writing Your Own Research Proposal

Now you may write your own research proposal, if you have not done so already. Follow the guidelines provided in this lesson.

Key Takeaways

- Developing a research proposal involves the following preliminary steps: identifying potential ideas, choosing ideas to explore further, choosing and narrowing a topic, formulating a research question, and developing a working thesis.

- A good topic for a research paper interests the writer and fulfills the requirements of the assignment.

- Defining and narrowing a topic helps writers conduct focused, in-depth research.

- Writers conduct preliminary research to identify possible topics and research questions and to develop a working thesis.

- A good research question interests readers, is neither too broad nor too narrow, and has no obvious answer.

- A good working thesis expresses a debatable idea or claim that can be supported with evidence from research.

- Writers create a research proposal to present their topic, main research question, subquestions, and working thesis to an instructor for approval or feedback.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Writing a Research Proposal

- Purpose of Guide

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- The Research Problem/Question

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Evaluating Sources

- Reading Research Effectively

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Is it Peer-Reviewed?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism [linked guide]

- Annotated Bibliography

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

The goal of a research proposal is to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting the research are governed by standards within the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, so guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and/or benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to ensure a research problem has not already been answered [or you may determine the problem has been answered ineffectively] and, in so doing, become better at locating scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of doing scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those results. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your writing is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to research.

- Why do you want to do it? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of study. Be sure to answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to do it? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having trouble formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here .

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise; being "all over the map" without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review.

- Failure to delimit the contextual boundaries of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.].

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research.

- Failure to stay focused on the research problem; going off on unrelated tangents.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal . The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal . Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal . International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal . University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing a regular academic paper, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. Proposals vary between ten and twenty-five pages in length. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like--"Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

In general your proposal should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea or a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in one to three paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Why is this important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This section can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. This is where you explain the context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is relevant to help explain the goals for your study.

To that end, while there are no hard and fast rules, you should attempt to address some or all of the following key points:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing. Answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care].

- Describe the major issues or problems to be addressed by your research. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain how you plan to go about conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Set the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you will study, but what is excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methods they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, where stated, their recommendations. Do not be afraid to challenge the conclusions of prior research. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your study in relation to that of other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you read more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

To help frame your proposal's literature review, here are the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.] .

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that it is worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research operations you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results of these operations in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that a methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is an argument as to why these tasks add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method is perfect so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your reader.