This Essay From 1949 Is Still The Greatest Love Letter To New York City

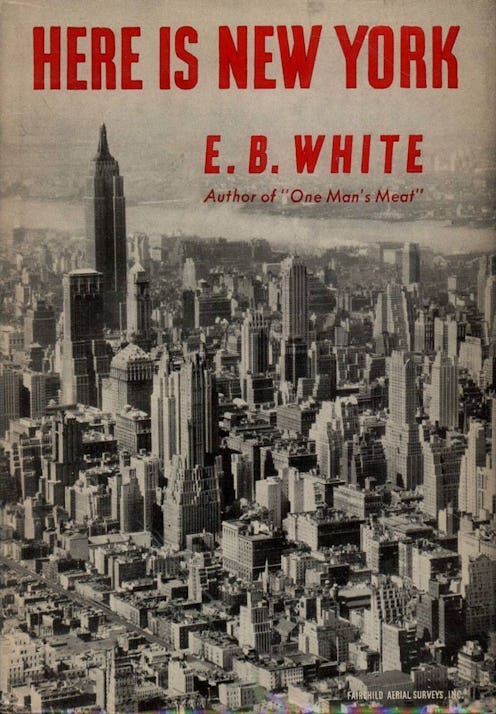

Much has been written on the city of New York. It's the eternal backdrop for rom-coms and financial thrillers, the source of Harlem Renaissance poetry and meandering web-series set in Brooklyn. An endless sea of books, films, and blogs have put forth their opinions on the city, each as contradictory and final as the next (it's overrated, lonely, overcrowded, beautiful, dirty, loud, magnificent, and the damned trains don't work). But if there is an apotheosis of writing on the apotheosis of cities, it has to be E.B. White's aptly titled essay-turned-book Here Is New York .

E.B. White is best known today for his children's books, Charlotte's Web, Stuart Little, and The Trumpet of the Swan, or for his writing style guide, The Elements of Style (he's the "White" in "Strunk & White"). He was also an essayist for The New Yorker and other publications for over fifty years, and "Here Is New York" might be his most celebrated essay. It's a straightforward stroll through the streets of Manhattan, the quintessential love letter to New York and New Yorkers. And, despite being published in 1948, it might be one of the most haunting pieces of post 9/11 literature ever written.

New York has changed since 1949, of course. America has changed. But to read "Here Is New York" today, it's impossible to shake the vague feeling that E.B. White was some kind of oracle, that he knew precisely which parts of the city would flourish, which would disappear, and how it might feel to live in New York in 2018, under the existential threat of war.

Here Is New York by E.B. White, $13, Amazon

White's essay begins by getting straight to the heart of New York's character:

On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.

It's not quite that simple, of course. White understands that New York is made up of a latticework of neighborhoods, interwoven pockets of community, and that New Yorkers are not really the cold-hearted creatures that slow walking tourists might see them as.

At the same time, though, White revels in New York's ability to cram in several million people and maintain an air of perfect solitude. There is spectacle and excitement if one wants spectacle and excitement, but every event is optional (with the exception, according to White, of the St. Patrick's Day parade, which "hits every New Yorker on the head").

He also understands that there is no single New York, but rather a number of different, overlapping cities, depending on who's looking:

There are roughly three New Yorks. There is, first, the New York of the man or woman who was born here, who takes the city for granted and accepts its size and its turbulence as natural and inevitable. Second, there is the New York of the commuter — the city that is devoured by locusts each day and spat out each night. Third, there is the New York of the person who was born somewhere else and came to New York in quest of something...Commuters give the city its tidal restlessness; natives give it solidity and continuity; but the settlers give it passion.

All of these conflicting New Yorks manage to meld and coexist, however, in a city that "has been compelled to expand skyward because of the absence of any other direction in which to grow." This cramped profusion of different lives and cultures only adds to the city, in White's opinion:

A poem compresses much in a small space and adds music, thus heightening its meaning. The city is like poetry: it compresses all life, all races and breeds, into a small island and adds music and the accompaniment of internal engines. The island of Manhattan is without any doubt the greatest human concentrate on earth, the poem whose magic is comprehensible to millions of permanent residents but whose full meaning will always remain elusive.

For all his rhapsodizing on the poetry of New York, though, White admits that the city can impart "a feeling of great forlornness or forsakenness," that it can often be "uncomfortable and inconvenient." But, as he puts it, "New Yorkers temperamentally do not crave comfort and convenience — if they did they would live elsewhere.”

After all, "the city makes up for its hazards and deficiencies by supplying its citizens with massive doses of a supplementary vitamin: the sense of belonging to something unique, cosmopolitan, mighty, and unparalleled."

And then there are the last two pages of the essay.

The subtlest change in New York is something people don’t speak much about but that is in everyone’s mind. The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible. A single flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges, turn the underground passages into lethal chambers, cremate the millions. The intimation of mortality is part of New York now: in the sound of jets overhead, in the black headlines of the latest edition.

White was writing about New York in the aftermath of World War II, after the introduction of the atomic bomb. But his words land squarely in the gut of any New Yorker who lived through 9/11, and of any American who currently lives under a president willing to make nuclear war the subject of angry tweets.

All dwellers in cities must live with the stubborn fact of annihilation; in New York the fact is somewhat more concentrated because of the concentration of the city itself, and because, of all targets, new York has a certain clear priority. In the mind of whatever perverted dreamer might loose the lightning, New York must hold a steady, irresistible charm.

White does not want to comfort his reader or assure the eternal safety of New York. He's not interested in hand-wringing or fear-mongering. He only tries to make sense of the fear. He's here to remind us of the things that must be protected in a time of political turbulence. Turning against each other is not an option for a city build on coexistence.

The city at last perfectly illustrates both the universal dilemma and the general solution, this riddle in steel and stone is at once the perfect target and the perfect demonstration of nonviolence, of racial brotherhood, this lofty target scraping the skies and meeting the destroying planes halfway, home of all people and all nations, capital of everything...

Finally, White compresses his own fear, New York's fear, the world's fear, into one last paragraph:

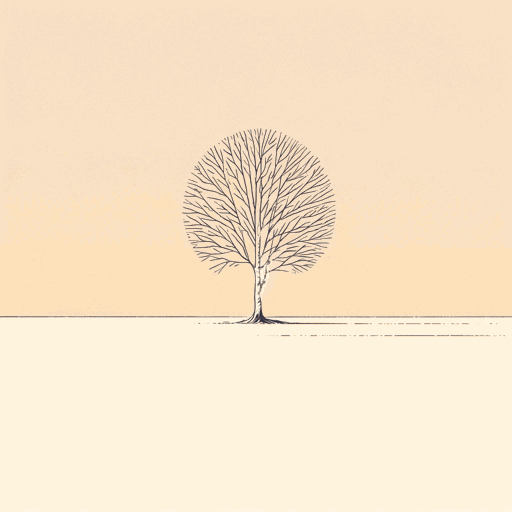

A block or two west of the new City of Man in Turtle Bay there is an old willow tree that presides over an interior garden. It is a battered tree, long-suffering and much climbed, held together by strands of wire but beloved of those who know it. In a way it symbolizes the city: life under difficulties, growth against odds, sap-rise in the midst of concrete, and the steady reaching for the sun. Whenever I look at it nowadays, and feel the cold shadow of the planes, I think: "This must be saved, this particular thing, this very tree." If it were to go, all would go—this city, this mischievous and marvelous monument which not to look upon would be like death.

From across the gulf of history, writing in New York of the 1940's, he manages to capture the mingled hope and terror that comes with life in any city today.

Here Is New York

26 pages • 52 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Analysis: “Here Is New York”

Content Warning: This section references terrorism and racism.

“Here Is New York” is an ode to the author’s beloved city. White uses descriptive language to evoke the inhabitants, architectural features, and numerous cultures that comprise New York City, using his past experiences and current observations to describe what sets it apart from other large cities.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,650+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,850+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

The essay sets out to capture the post-World War II age in New York while situating this version of the city in a historical context . White toggles back and forth between his real-time 1948 observations, his knowledge of the city’s past, his own previous experiences in New York, and sociological musings on the city’s culture and inhabitants. This structure, made up of multiple frames of reference, offers numerous entry points and sources of information. White includes factual firsthand accounts, historical retellings, and poetic musings. As White shifts between types of information, the tone changes as well.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By E. B. White

Charlotte's Web

E. B. White

Once More to the Lake

Stuart Little

The Trumpet of the Swan

Featured Collections

Books on U.S. History

View Collection

Creative Nonfiction

What Makes a Great City: E.B. White on the Poetics of New York

By maria popova.

But what makes a great city? Scholars, social scientists, and urban planners have pondered the question for centuries, pointing to everything from walkability to the social life of small urban spaces . And yet the most timeless answer is a poetic rather than a pragmatic one.

From the 1949 gem Here Is New York ( public library ) — one of the best books about New York ever written, and undoubtedly one of the best books about anything — comes an exquisite articulation by E.B. White (July 11, 1899–October 1, 1985), who captures the singular mesmerism of Gotham and all the “enormous and violent and wonderful events that are taking place every minute.”

In one of the most spectacular passages, he writes:

New York blends the gift of privacy with the excitement of participation; and better than most dense communities it succeeds in insulating the individual (if he wants it, and almost everybody wants or needs it) against all enormous and violent and wonderful events that are taking place every minute. … New York is peculiarly constructed to absorb almost anything that comes along (whether a thousand-foot liner out of the East or a twenty-thousand-man convention out of the West) without inflicting the event on its inhabitants; so that every event is, in a sense, optional, and the inhabitant is in the happy position of being able to choose his spectacle and so conserve his soul.

But White’s words also emanate the universal exhilaration of any large city that cajoles humanity into a state of constant interaction:

A poem compresses much in a small space and adds music, thus heightening its meaning. The city is like poetry: it compresses all life, all races and breeds, into a small island and adds music and the accompaniment of internal engines. The island of Manhattan is without any doubt the greatest human concentrate on earth, the poem whose magic is comprehensible to millions of permanent residents but whose full meaning will always remain elusive.

Here Is New York is a sublime read in its entirety, as “miraculously beautiful” itself as the city it serenades. Complement it with White’s moving obituary for his beloved dog Daisy and his beautiful letter to a man who had lost faith in humanity.

— Published July 9, 2014 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/07/09/e-b-white-here-is-new-york/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books cities culture e. b. white new york, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Here Is New York

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

Book Source: Digital Library of India Item 2015.166056

dc.contributor.author: E. B. White dc.date.accessioned: 2015-07-07T00:11:54Z dc.date.available: 2015-07-07T00:11:54Z dc.date.digitalpublicationdate: 2004-07-26 dc.date.citation: 1949 dc.identifier: RMSC, IIIT-H dc.identifier.barcode: 2999990038253 dc.identifier.origpath: /data/upload/0038/258 dc.identifier.copyno: 1 dc.identifier.uri: http://www.new.dli.ernet.in/handle/2015/166056 dc.description.numberedpages: 54 dc.description.numberedpages: 22 dc.description.scanningcentre: RMSC, IIIT-H dc.description.main: 1 dc.description.tagged: 0 dc.description.totalpages: 76 dc.format.mimetype: application/pdf dc.language.iso: English dc.publisher.digitalrepublisher: Universal Digital Library dc.publisher: Harper Amp Brothers dc.rights: Copyright Protected dc.title: Here Is New York dc.rights.holder: E. B. White

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

12,586 Views

35 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Public Resource on January 19, 2017

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Sign in / Join

- Portuguese (Brazil)

- Portuguese (Portugal)

Results from Google Books

Click on a thumbnail to go to Google Books.

- 0 0 Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff ( lilithcat ) lilithcat : Another love story to New York!

- 0 0 The Owl Pen by Kenneth McNeill Wells ( edwinbcn ) edwinbcn : Both The Owl Pen by Kenneth McNeill Wells and Here is New York by E. B. White describe living on a farm in the countryside, with nostalgia for the old ways of living that were still around in the 1920s - 1950s, but came under pressure later in the century.

Sign up for LibraryThing to find out whether you'll like this book.

No current Talk conversations about this book.

» Add other authors (7 possible)

Is contained in

Distinctions.

References to this work on external resources.

Wikipedia in English

No library descriptions found.

Current Discussions

Popular covers.

Melvil Decimal System (DDC)

Lc classification, is this you.

Become a LibraryThing Author .

The New York Times

City room | in the subway, the 3 new yorks of e. b. white, in the subway, the 3 new yorks of e. b. white.

There may be two Americas , but there are three New Yorks (roughly). Or so claims E. B. White, excerpts of whose 1948 essay, “ Here is New York ,” were introduced last month as part of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s new Train of Thought literary campaign (which displaced the Poetry in Motion campaign , much to the dismay of poets). The selection, which is supposed to represent a slice of history, seems particularly meaningful on the subway, for Mr. White posits:

There are roughly three New Yorks. There is, first, the New York of the man or woman who was born there , who takes the city for granted and accepts its size, its turbulence as natural and inevitable. Second, there is the New York of the commuter — the city that is devoured by locusts each day and spat out each night. Third, there is New York of the person who was born somewhere else and came to New York in quest of something ….Commuters give the city its tidal restlessness, natives give it solidity and continuity, but the settlers give it passion.

The idea of three New Yorks has prompted debates among New Yorkers, non-New Yorkers and people who wish they were New Yorkers.

Can anyone really claim to know New York, a city of eight million , City Room wonders? And just who is a New Yorker anyway? Commuters , settlers and natives ? (Don’t forget the original natives .)

Incidentally, one passage in the “Here is New York” essay struck many for its prescience in the weeks after 9/11:

The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible. A single flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges, turn the underground passages into lethal chambers.

The E. B. White selection will be up for three months. The other selection, focused on science, is by Galileo.

Maybe there are three (or more) New Yorks — but sliced in a different way.

After all, a third of the city’s income is earned by the top 1 percent of its tax filers. For the state overall, every dollar earned by the top fifth of is matched by only 11.5 cents by the bottom fifth — the biggest gap in all the states. In Manhattan, the poor make 2 cents for $1 the rich make (on par with Namibia).

With the rising costs of housing , food , gas and the advent of a what some call the new gilded age , class — not place of origin — might be the true New York divide.

Comments are no longer being accepted.

Thank you for adding the class aspect to E.B.White’s rather dated (it turns out) concept. I’ve always been moved by the White piece but now… I’m more moved and of course appalled by the ever-widening gap between obscenely rich and the vast majority of regular humans. When will something be done to redress this hideous imbalance(if ever)? At least words like yours open the discussion. Again, thanks.

I was born in Brooklyn and have lived here all my life, save for a brief childhood interlude in Coral Gables necessitated by my father’s still-incomprehensible-to-me dream of living in Florida. No “settler” has more passion for NYC than I do. I have never doubted that this is the greatest city in the world. I remember thinking that every day I longed to be back in Brooklyn during my Florida purgatory (which became hell with the hot weather). This native, at least, never takes the City for granted.

While many of us find this idea laudable, it’s also laughable…Over eighty percent of the riders on the MTA NYC subways today are not native Engish speakers, let alone readers…In fact many a time I’m riding in a subway car now and I’m the only one who would be speaking English, if I had someone speaking English to talk to, aside from the realization that I am one of the only English speakers with a native New York accent…. This just shows that the powers that be, never take the subways, and in fact, live in their own cocoons…As the kids would say, get real!

I reread the EB White piece after Sept. 11 and have read it again from time-to-time since. It is an amazing glimpse at New York and, of course, the passage excerpted above is uncanny and prescient. I don’t imagine the MTA will be posting that passage, as it can be upsetting to some intimately touched by the events of Sept. 11.

E.B. White was one of the most brilliant writers who ever put pen to papyrus and wrote for the New Yorker along with James Thurber to make it become one of the great magazines of the twentieth century.

Claiming to be a New Yorker requires more than having a mailing address. One must have amazing resiliency, an abilty to survive, no matter the train delays or unbelieveable high cost of living. A New Yorker is never defeated.

White’s essay on New York has always touched me deeply; it’s the first essay I’ve shared with my son.

I’ll betcha plenty of the immigrants who ride the trains along with Vic would understand a lot more of it than he’d give them credit for.

It’s the “person that was born somewhere else and moved to NYC” that makes this city great. They bring the passion, idealogy, and real-world experience that brings New York alive and gives it its character. I agree with E.B White. Commuters are who they are, they just work here. People who were born and raised here don’t really have a sense of what else is out there, take it for granted, and don’t do much to give the city its life.

There is only one true New Yorker. The one who was born here. I grew up in New Jersey and now live in Lower Manhattan but I will always respect the fact that they can only be one New Yorker..despite the beauty of E.B. White’s words…

As an interesting side note, this beautiful piece is often used as an essay question on the entry test for the excellent Bard Early College HS – a school that has a big middle class and working class immigrant population. I bet reading those essays by the bright 13 year olds who apply would reveal some striking points of view.

There is a fourth kind of New Yorker: the native who leaves. We in exile “know what else is out there” and have chosen it. But we will forever measure all cities against New York. Actually, there’s a fifth kind of New Yorker: those who come and leave, but nonetheless maintain a New York sensibility. Jane Jacobs springs to mind.

It’d take a guy a lifetime to know Brooklyn t’roo an’ t’roo. An’ even den, yuh wouldn’t know it all. Thomas Wolfe

lest we forget the real new yorkers…the pigeons.

I am always irritated at the chauvinistic pride of the “born and bred” New Yorker, as if he/she alone can fully enjoy and appreciate what this city offers. New York is, like all of America, a crossroads of immigrants from all over the world, and Betty from Brooklyn is just as much a New Yorker as is Pedro from Puebla and Dinesh from Dhaka and…

As someone who moved here (relatively unwillingly) for a job, I’ll never understand those who are willing to pay millions of dollars for a tiny apartment when those same millions in a mid-size city (Philadelphia, for example) would fetch a penthouse suite.

F. Scott Fitzgerald (Minnesota), Harold Ross (Colorado), Bob Dylan (Minnesota), Jackson Pollock (Wyoming), Andy Warhol (Pittsburgh). All provided a distinctly New York cultural identity, yet all were from the west or midwest. This is the passion to which White correctly ascribed to the settlers.

I had always been just a little sheepish as a settler in the midst of native New Yorkers but that changed when my two kids were born in (then) Beekman Downtown Hospital. I’ve been outnumbered since then and taken my licks from them and my native wife, so I don’t feel like such an outsider anymore. And I think my kids have gotten something from the story of my migration here, even if they’ve heard it a few times too many.

Too simplistic, E.B. White. Plenty of native-born New Yorkers give it “passion” (defined by whom?); the list is very long. And plenty of non-natives don’t.

There is yet another facet to New Yorkers that is worth remembering (and posting on the trains): our determination. White wrote:

“Mass hysteria is a terrible force, yet New Yorkers seem always to escape it by some tiny margin: they sit in stalled subways without claustrophobia, they extricate themselves from panic situations by some lucky wisecrack, they meet confusion and congestion with patience and grit-a sort of perpetual muddling through.” In the same essay, he also mentioned the commuter calmly “stuck in the mud” beneath the East River.

And we dare not forget another of White’s points – perhaps the one that allows us to tolerate all of the nonsense that we see: “But the city makes up for its hazards and its deficiencies by supplying its citizens with massive doses of a supplementary vitamin – the sense of belonging to something unique, cosmopolitan, mighty and unparalleled.”

It’s still that way in New York!

EB-had reason to prefer transplants- he moved here from Mt. Vernon after college.

My favorite description of the class differences change in attitude is in Bonfire of the Vanities, when the protag’s dad takes the local to Wall St, while he takes the private car. In Bloombergville, the gap is even wider.

Time was, you wouldn’t date anyone with a 718 area code (because long distance relationships are just too hard).

Now, I find it hard to confer NYC citizenship on anyone who rode to high school via internal combustion powered conveyance (unless there was a fare involved, and preferrably a transfer). Remember the details of at least one transit, garbage or teachers strike making you late for class, and I’ll buy you a pint. If your journey involved the L train I’ll support your run for Mayor.

For the record, I now live in Morristown, and commute to Flushing.

Vic – “Over eighty percent of the riders on the MTA NYC subways today are not native Engish speakers”?

As they say on Wikipedia, citation needed…

As a native New Yorker (born in Lenox Hill) I am so appreciative when people respect the very special relationship that New Yorkers born in the city have with the city, and so angered when others believe that a few months out of college in new york grants them true new yorker status.

also, whatever passion the settler might bring to the city, it is the native’s devotion that keeps the city alive and vibrant. I remember very well the days after september 11th when people were afraid to enter the city. I remember because I, along with my family and friends, didn’t go anywhere.

the people and the spirit of new york will always remain indestructible.

As a visitor here, I’m struck by how quickly I want to be a New Yorker. It’s the very essence of what a cosmopolitan city should be. I’m from Los Angeles and Orange County and nothing back home is as centralized and culturally rich as it is here. The funny response I get from New Yorkers when I say I’d like to move here is kind of like, “why would you want to do that?” But still, I will look forward to my return to New York.

how about a fourth version – the carrie bradshaw wannabes that come from all corners of america that only hang out in the meat packing district and live in the upper east side, believing that being a new yorker is wearing the jimmy choos and eating at tao?

I actually liked what White wrote…I found it poetic and overall true. And as to what makes one a “New Yorker”, I think it has to do with state of mind and personality more than anything. Do you say what’s on your mind in a direct manner? Do you get right to the point and not beat around the bush? Etc. THAT’s a New Yorker. And plenty of these “commuters” can be that way and in fact, were born in NYC and then moved out to Westchester or what have you. I think after you’ve lived here a number of years, you can’t help but become a NYer.

What's Next

- Sample Page

E.B. White’s Here is New York

Write a post for Sept. 3rd:

Analyze E. B.White’s opening line, “On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.”

Discuss White’s prophecy (final pages of the book) about airplanes in the light of 9/11.

About Roz Bernstein

17 responses to e.b. white’s here is new york.

Kamelia Kilawan E.B. White’s Here is New York

The opening line of Here is New York has a clear-cut message: true New Yorkers treasure solitude and their privacy. In today’s times both of these qualities define the way we view not simply the lives of our elected leaders but also every small business owner, immigrant, parent, child, teen, or simply put: any New York resident with a dream.

I believe that E.B. White had a solid idea about the most unique and valuable things New York City can offer. Not simply freedom or an opportunity for those who desire it, but the very qualities that make this city a haven for the “queer.”

White’s eerie omen in the wake of 9/11 about the danger of soaring airplanes in the midst of high skyscrapers makes him not only an amazing writer but one with amazing foresight.

And his prophecy to preserve the one natural, high element of the city, the tree, reminds me of the prophecy we see in environmental activism and films like The Lorax. I, for one, agree with White. Much like the tree in his story, strained in every direction, we all are just the same.

It is important to acknowledge and maintain the natural, because it is the only true example of our own queer desires and the inability we have to pursue all of it in a lonely, private city.

Outside of New York, some people may refer to native New Yorkers as jaded, unconventional and insensible because of their lack of attention and caring for their surroundings. E. B. White opens his iconic poem about New York with “on any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gifts of loneliness and the gift of privacy,” which illustrates that as crowded and crazy the city might be it makes each person feel alone in their own world.

As a commuter, and referred by White as a citizen of the second New York, I welcome those gifts of privacy and loneliness. Within those moments and hours of wandering the city I create my own world and have the ability to find myself. There is so much that occurs within the small island and it breaths the aurora of “it could happen to you,” and success is just inches away. People can feel the loneliness and inadequateness but it also brings a sense of peacefulness that transforms into a communal bond between others, and contradicts the idea of being lonely in this vast city.

White continues his depiction of New York and ends with a disturbing and echoing analogy in the wake of the attacks on September 11th. “The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible,” White wrote. The citizens of Manhattan gave the world a sense of invincibility and immortality, until the day that terrorist attacked the World Trade Center. As White proclaims, “a single flight of planes can quickly end this island fantasy,” it brings New York back to fragile and humane state. We come together in crisis’s, take away prejudices and work to rebuild New York for future generations.

Rebecca Ungarino on E.B. White’s Here is New York

The references of New York establishments both past and present, the still-relevant ideals of New Yorkers, and the descriptions of the “three New Yorks” in E.B. White’s short novel are beautiful features of what comes across as a long essay.

The opening line largely sets the tone for the book. White demonstrates from the first few lines that New York, in its five boroughs, is indeed made up of masses of people – natives, transplants, and commuters – who seek out grand lives (these “queer prizes” that White refers to) in one capacity or another, but all want – and receive – quiet, lonely, private lives at the end of the day. No matter the neighborhood, as White mentions many neighborhoods in his book, New York gives its residence a chance to work, a chance to travel, and a chance to rest.

The first line cuts to the chase. E.B. White casts such a shadow over New York, ironically of course, and describes the boroughs with such New York-style disdain that any non-New Yorker wouldn’t want to step foot onto New York soil.

The disturbing omens concerning planes and destruction that White makes throughout the book lend themselves to White’s accurate (while some may say prophetic) insight about New York’s ruination. Three separate instances – toward the beginning of the book, in the last few pages, and then in the last paragraph – occur where White mentions planes causing tragedy in New York. I think of it has, perhaps E.B. White predicted that New York would be overtaken by commercialized endeavors, technology, and bigger, greater vehicles, or maybe he literally meant planes. Either/or, his prophecies prove to be extremely eerie.

Overall, Here is New York is a gorgeous depiction of the real New York.

Danielle Russell E.B. White’s Here is New York

New York is filled with over 8 million residents today. But somehow you can be surrounded by so many people and still feel alone. New Yorkers are known to be unfriendly, rude, and self-reliant. We are eager to get where we are going without interacting with our surroundings. The city offers a sense of coldness, coldness in the sense that everyone is too focused on themselves to develop relationships with others. People become so entangled with making their dreams come true they forget the point of living. White says that “the quality of New York that insulates its inhabitants from life may simply weaken them as individuals.” That is why many say if you can make it in New York you can make it anywhere. There is so much going on in this city many are amazed how people from different races, religions and social statuses manage to coexist together. E. B. Whites book about New York is still relevant today because we still deal with many of the issues he wrote about.

White’s prophecy about airplanes in the light of 9/11 was head on. It makes me think he had an uncanny knack for predicting how New York will turn out. I think it was completely logical for him to feel New York City is no longer indestructible. Society is always advancing and new technology is being invented. It is now easier to reach different places and get your hands on anything imaginable. With New York also growing and developing into a city bigger than life, no wonder why it would be a target for many. E. B. White brings to light that with greatness there comes a price.

Here is New York Marian Thomas First line means of those who strangely decide to live in New York or be in New York it will bring loneliness despite there being so many people and also privacy in which the people of New York care about theirselves and their personal gain that leads ppl to live private lives. He continued to stress the space of eighteen inches of seperation and connection of those in New York he seemed to meet.

In the final lines, White seemed to predict 9/11 as he went on to say New York is destructible and how planes can crash and burn the towers, alluding to the Twin towers. He seemed to think the city was a target and that the people could be annihilated at any time.

Jennifer Ross E.B. White’s Here is New York

“On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.”

In any other town in this nation, loneliness would not be considered a gift…maybe privacy, but definitely not loneliness. To “bestow” loneliness and privacy on a person, in any other town, big or small, could otherwise be known as shunning an outcast amongst the community, someone so obscure or awkward that the locals deem untrustworthy or scary to be around. Yet, in New York, it is a gift and a glorious one at that.

I imagine a tourist reading E.B. White’s opening line and feeling a deep confusion, a troubled sadness, thinking, “What is wrong with New Yorkers? Who would voluntarily want to live in loneliness and privacy?” They imagine this gift in their town, their environment, a place nothing like New York, be that as it may. Without the gift, New Yorkers could lose all patience within themselves and with their world, eventually becoming, dare I say it – rude. Perhaps after reading this quote, the ordinary tourist can justify calling a New Yorker rude, and calmly return to their world appreciating theirs while demonizing the big “bad” apple.

Airplanes in the light of 9/11

There’s a sense of eeriness in how E.B. White describes the city and its destructibility. “A single flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers….cremate the millions.” Never had I imagined this could be prophesized so many decades ago, in such a small book. Yet there it is, in black and white. “…cremate the millions.” How horribly truthful those words are. I wonder what E.B. White would have said had he been in the city on that fateful morning. Would he have any words to say; or could the site of the burning trade towers leave him as it left many of us – speechless. As I read his words, mental images flooded my mind of where I was that morning. What was I doing? Who was I with? Did I speak? As terrible as that day was, E.B. White’s “prophesy” was wrong in one matter. We did not destruct. The city may have been badly burned and forever scarred, but it is now much wiser and stronger. The city proudly wears that scar for all to see. No shame on its face, just strength.

Analyze E. B.White’s opening line, “On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.”

As Roger Angell expressed in his introduction of E.B White’s work, “It is hard to feel private in the surging daily crowds at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, say, or lonely on a side street packed solid with gridlocked traffic.” (11) Indeed, the opening line of Here is New York seems peculiar when one witnesses the sheer flood of civilization in New York City. People seem to be swarming the streets of the city, each with vibrant passion, excitement and enthusiasm. For most, the ’18 inches’ of separation that New York offers its inhabitants from one another offers a dream come true: a “Fragile participation with destiny.” The city provides a front row seat to “…all enormous and violent and wonderful events that are taking place every minute.” (21). However, to those who desire such queer prizes, the enormity and grandeur of New York can make the privacy and loneliness achieved all the more satisfying. As I commute every day to Baruch College, I witness firsthand how the all the commotion, bright lights, and attractions vying for our attention are merely a silent background to most as they race through the agendas of their day. Paradoxically, for those longing for internal quiet, New York is perfect.

Discuss White’s prophecy (final pages of the book) about airplanes in the light of 9/11.

Written in 1949, the scene depicted by E.B White in the final pages of his essay is at once enlightening and startlingly familiar in the aftermath of 9/11. It is important to note that at the time of the writing of the book, the gruesome sights and sounds of war were probably ingrained in the mind of the author after the atrocities of WWII, and of the Holocaust. People around the world saw images of planes flying over civilian neighborhoods in Europe dropping bombs on apartment complexes. It was only natural for White to envision the grand struggle of worldwide conflicting ideologies that would ensue. At the time of the publishing, E.B White witnessed the building of the United Nations on New York soil. There, hundreds of nations would be represented in no other city in the world but Manhattan. Therefore, there is no greater message of hate than to mercilessly attack New York, “the capital of the world” (55) and a symbol of cultural diversity, heterogeneous unity, racial brotherhood and freedom. As White states, “Today Liberty shares the role with Death.” (54) Thankfully Mr. White’s prediction of the annihilation of New York City never occurred. Yet, for those of us who experienced the terror attacks of 9/11/01, White’s message rang true. The world must collectively take a stand against acts of hatred and intolerance, and feverishly support the ideals that hold up this great city today.

“On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.” E.B. White’s opening line captures New York City’s character. This further developed in the reading, but the opening line sets the tone by getting the reader to ask why and how the city grants the gift. This opening line is true to every aspect of the city both good and bad. It expresses the feelings of inclusion and exclusion that everyone can feel at a given moment because of people from all walks of life colliding in one place. White’s last line shows that the feeling of fear has been constant in the city because of its esteem. The way White is able to tap into the emotion of the city is what makes this piece timeless. This is why the last line is alarming to a generation that has lived through 9/11. The emotions he felt at the time and the emotions felt now are the same.

Although New York is a city filled with people, it is definitely a place where one can be lonely and private. Especially with todays use of technology, things like social media have replaced social interactions. In a fast paced city filled with people, it is easy for one to get overwhelmed and not be able to keep up.

New Yorkers are known to be in a rush. Following their daily routines, people dash from one place to another without a second glance at those that are around them. Seeking prizes like money and fame can leave a person distant from people. Balance of work and social life is needed unless loneliness and a private life is what you seek.

” A single flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges, turn the underground passages into lethal chambers, cremate the millions.”

This quote describes the tragedy that occurred on 9/11 as if it were written after the fact. New York, a city full of life became a quiet city filled with worried people who would flinch at the sight or sound of a plane in the sky. The “fantasy of an indestructible city was shattered. Those who, in panic, ran into the subways for shelter found themselves trapped in “lethal chambers. Frantic people seeking their way out of the smoking city filled the bridges. The swinging bridges filled over capacity seemed as if they were to fall and crumble, taking everyone with it.

Taxonomizing E.B. White’s Here is New York as simply a description of “the city that never sleeps” is unfair. White aptly expresses, in less than sixty pages of text, what makes a New Yorker, the feelings and emotions, from various perspectives, accompanying that title, neighborhoods in New York, the constant changes of the people, mood, and structure of the City, and, more generally, the paradox that is New York City. White begins by writing, “On any such person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy,” leading readers into his paradoxical characterization of New York. Being a New Yorker, and what White would call a “commuter,” I find myself in numerous situations surrounded by thousands of people, with whom I am only “eighteen inches away from,” feeling totally alone. I enjoy the repose of a subway ride, where I am packed tightly in a steel box with fifty or so people. I embrace the fact that a man can wear a pink bikini while riding a bicycle on crowded Lexington Avenue without question or second glance. White captures paradoxes, such as the “gifts” of loneliness and privacy, on so many levels that it is unfair to call Here is New York simply a description. If anything, Here is New York is foreboding. People living in privacy and loneliness while never being more than eighteen inches away from one another is fragile. The complex system White describes seems to be teetering on destruction– even death. Planes remind White of this fragility; a simple squadron of planes equipped with bombs could end New York. Written in the mid 1900s, White predicts the 9/11 terrorist attacks. However, even such a tumultuous event did not stop New York from beating on, something White also alludes to. Planes may be equipped with bombs, or used as bombs, but New York and New Yorkers come equipped with resiliency and a sense of community.

In an attempt to bring it down to date, I look out into a more remote part of New York in Long Island where I am free from the hustle of the city E.B. White longingly spoke of in “Here is New York.” I travel on the same Long Island Railroad he mentioned as a daily commuter privy to the city’s way when I am there and reserved when I think about it as I return to the suburbs. Across streets and avenues I seldom have a moment to stop and reflect lest I relinquish my own personal space to people maneuvering their way around me. Yet, I can find a space on a bench in Madison Square Park and put my earphones in and there I find solidarity; a slice of the loneliness and privacy that White speaks of. That slice today is much thinner than before as our seasons rarely hold the relaxed air breathed in by die-hards of White’s summer. We look at the growth of New York sometimes with sadness because we do not want it to be marred by another 9/11. New York has risen as an example and as a target. When White wrote this piece he perhaps estimated his prophecy about the “destroying planes” to the conflict with the Soviet Union, at the time a presumable nuclear threat to the United States. We have seen the impact of the planes on 9/11 and today we behold the uncertainty regarding Syria and the U.S.’s position on chemical weapons. When I walk under the shadow of these buildings, I can feel the routine of the trains beneath me or hear innocent shouts or sirens going off here and there and I wonder of the “perverted dreamer” in the midst waiting to “loose the lightning.” At those times I long to steal away in New York’s gifts all the while knowing that even in our privacy there is a charisma about this city that will not hide it as a target; not then and not now.

E.B. White poses a hopeful and majestic view of New York that he acknowledges through his descriptive details of the beauty of the city and its people. The opening line promises “the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy” to those finding their way to New York for the very first time. The line is an honest paradox of what one may experience while living in the city. Despite its inviting bright lights and crowded streets, the city can often make one feel isolated in his or her own destination and goal. A common example of this would be the morning commute on the 6 train. Strangers make it their priority to ignore others by covering their eyes with sunglasses, stuffing their ears with earphones, pulling their bags close, and letting their minds wander. White captures this concept perfectly.

The last pages of the book eerily prophesied the events of 9/11 despite being written roughly fifty-three years prior. White describes the “flight of planes” as the sign of the city’s imminent mortality and destruction. The irony in this idea is that the very thing that can destroy the city is the thing that built it: man. The image of the great, thriving city that never sleeps shutting down in silence and annihilation is haunting to this day. Despite this dark prophecy, White keeps a somewhat optimistic view; he states, “This must be saved, this particular thing, this tree.” The battered, willow tree symbolizes the life that exists before the installments of the buildings and the bridges, before New York came to be. To White, this tree may have been a symbol for new growth. But most of all, it is a symbol of strength and hope that must be saved in times of tragedy. It is what drives New York to become the city that it is today.

“On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.” This is an interesting opening line. The author E.B. White’s opening line seems to be coming from his own personal experience. It is interesting to see how he uses the term “gift” as a form of reward with words such as loneliness and privacy. It is as if people who encounter success would prefer to be left alone rather than be surrounded all the time with those who always want to be in their presence consistently.

White’s prophecy about airplanes in the light of 9/11, is clearly an idea that led to action. It can be believed that New York is destructible because of the recent events of 9/11. All these new technology’s and infrastructures can destroy human kind because it has. Even when all these things are meant to better the world and ways of living, there can be a reverse effect which has been proven to exist from past events. However, White could be using the planes as an example because during that time, war had just occurred. The city was in amazement with the new surroundings. Buildings were being built taller than trees and planes were new to everyone. White had an idea and it is upsetting that it had to become reality.

E.B. White’s timeless quote “On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.” is covering the truth of New York, a city of 8 million, that ironically provides a sense of isolation for its people. The ability to be condensed in a town with this amount of humans, and successfully coexist as completely polarized individuals, is a prize in and of itself.

As New Yorkers, we move as loners with our own agendas, directly next to millions of peers, on a daily basis. The negative connotation that goes with a word like “loneliness” is a viewpoint that would be understood from an outsider looking in, but as a native, you have no choice but to be familiar with the underlying value that “loneliness” provides.

The physicality of sharing sidewalks and train cars with so many others can seem paradoxical when remembering the fact that your life path is a completely lonesome entity, who’s paving is exclusively left up to you and the city.

E.B. White’s mention of airplanes is just as much a work of art as his subject matter, New York City. Vivid, descriptive creations, which both make a statement that is left up to the observer to decode.

The man From The Bronx who travels to Staten Island every weekend to help Hurricane Sandy victims with the restoration of their homes and businesses. The rushing college student who’s running late for class and stops to help a tourist correct their mistake of taking the R train into Queens from 59th street, when they actually meant to hop on the uptown 6, destined for the Met Museum. These examples of natives stepping outside of their privacy may not be what is brought up when the general boxed description of a New Yorker is the topic of conversation; but the layers of people and personality types is what makes that box simply too small to be the whole truth.

Our uniqueness has gone through every type of criticism from outsiders, but our inside understanding of the way the city works provides a sense of thick skin. Those who have fantasized about our preconceived “coldness,” probably watched the television in awe the weeks following the September 11, 2001 attack, as New Yorkers supported each other in a time of need.

In times of need, New York stands united. Other parts of the country and world may criticize us for not sharing false smiles and greetings with strangers on a daily basis, but that would only distract us from the privacy and loneliness that gives our city it’s unique character.

From devastating terror attacks, electricity blackouts in the hottest days of summer, and even the wrath of a super storm that paralyzed a large portion of the city for months, New York continues to show it’s strength and ability to live in unison. E.B. White certainly captured a glimpse of that strength in “Here is New York.”

Many may not understand why we wait until times of hardship to show a broad sense of camaraderie. I say it’s New York’s way of doing things, and we’ll continue to do just fine being the one’s who get it.

Really thoughtful comments on E.B. White’s Here Is New York. Worth mentioning, too, is White’s powerful use of language –his voice. Narrative. First person. Engaging. Literary. He is truly a visual writer. We see and we hear what he sees and what he hears. As we write our feature stories this semester, keep White’s voice in your mind.

The first line by E.B White: “On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy”. Is a great way to capture the reader’s attention, whether you have lived in New York or not. Why? Because it can be hard to have a sense of privacy in a city filled with different ethnicities and thousands of people from different countries all meshed into one place. However, loneliness can easily be found in the city whether you consider it a gift or a curse. The city that never sleeps is always on the move; people go through one phase of the day to another at the speed of light. This can clearly lead people to feel disconnected with the city itself as well as the people around them. Yet, the final line alluding to 9/11 makes this reading timeless, its alarming to see how he can still connect the city and the feelings of people towards it in today’s generation with such a prediction, while the times change, the city’s vulnerability and the connection to the people in it, do not change. -Abel Ramirez

Comments are closed.

- Search for:

Recent Posts

- Less Art and More People: SoHo

- Getting Your Blog Portfolio in Order

- Profile of Tiger Writing by Gish Jen

- Teen Joyrides Run Awry, Leaving Behind Community in Questions

- Protected: Stigma of the Past

Recent Comments

- Margarita Lappost on Heading Elsewhere for a Better School: Education in Washington Heights

- wdiaz on Less Art and More People: SoHo

- wdiaz on Searching for a Skateboard Haven in Hempstead

- wdiaz on Restaurant Row in Spanish Harlem

- Abel Ramirez on Heading Elsewhere for a Better School: Education in Washington Heights

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- A.J. Liebling

- Amanda Burden

- Announcements

- Backgrounder

- Commentary and Critiques

- Community Services

- Conflict Story

- Deadly Choices at Memorial (Fink)

- Here Is New York

- Joseph Mitchell

- Neighborhood News

- Neighborhoods

- ProfilesDRAFTS

- Reporting Notes

- Small Business

- Story Queries

- Uncategorized

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

- Try the new Google Books

- Advanced Book Search

- Find in a library

- All sellers »

From inside the book

Other editions - view all, common terms and phrases, bibliographic information.

- Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

Promotions apply when you purchase

These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

Audiobook Price: $11.38 $11.38

Save: $8.72 $8.72 (77%)

Buy for others

Buying and sending ebooks to others.

- Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the authors

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Here is New York Kindle Edition

- Book 1 of 1 Here is New York

- Print length 59 pages

- Language English

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publisher Little Bookroom

- Publication date March 30, 2011

- File size 434 KB

- Page Flip Enabled

- Word Wise Enabled

- Enhanced typesetting Enabled

- See all details

- In This Series

- By Roger Angell

- Customers Also Enjoyed

- Literature & Fiction

Editorial Reviews

Amazon.com review.

Anyone who's ever cherished his essays--or even Charlotte's Web --knows that White is the most elegant of all possible stylists. There's not a sentence here that does not make itself felt right down to the reader's very bones. What would the author make of Giuliani's New York? Or of Times Square, Disney-style? It's hard to say for sure. But not even Planet Hollywood could ruin White's abiding sense of wonder: "The city is like poetry: it compresses all life ... into a small island and adds music and the accompaniment of internal engines." This lovely new edition marks the 100th anniversary of E.B. White's birth--cause for celebration indeed. --Mary Park

About the Author

Excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., product details.

- ASIN : B004KZP0WY

- Publisher : Little Bookroom (March 30, 2011)

- Publication date : March 30, 2011

- Language : English

- File size : 434 KB

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Enabled

- Word Wise : Enabled

- Sticky notes : On Kindle Scribe

- Print length : 59 pages

- #2 in Mid Atlantic U.S. Regional Travel

- #2 in 90-Minute Travel Short Reads

- #21 in 90-Minute Biography & Memoir Short Reads

About the authors

Roger angell.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

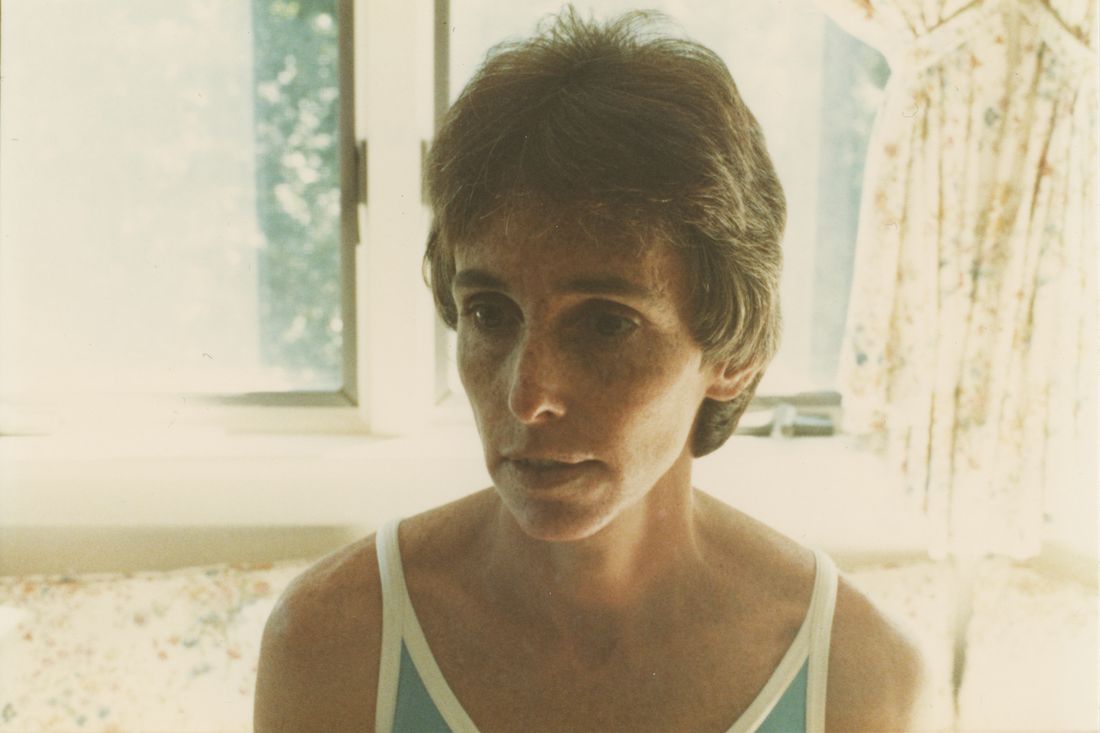

E. B. White

E.B. White, the author of twenty books of prose and poetry, was awarded the 1970 Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal for his children's books, Stuart Little and Charlotte's Web. This award is now given every three years "to an author or illustrator whose books, published in the United States, have, over a period of years, make a substantial and lasting contribution to literature for children." The year 1970 also marked the publication of Mr. White's third book for children, The Trumpet of the Swan, honored by The International Board on Books for Young People as an outstanding example of literature with international importance. In 1973, it received the Sequoyah Award (Oklahoma) and the William Allen White Award (Kansas), voted by the school children of those states as their "favorite book" of the year.

Born in Mount Vernon, New York, Mr. White attended public schools there. He was graduated from Cornell University in 1921, worked in New York for a year, then traveled about. After five or six years of trying many sorts of jobs, he joined the staff of The New Yorker magazine, then in its infancy. The connection proved a happy one and resulted in a steady output of satirical sketches, poems, essays, and editorials. His essays have also appeared in Harper's Magazine, and his books include One Man's Meat, The Second Tree from the Corner, Letters of E.B. White, The Essays of E.B. White and Poems and Sketches of E.B. White. In 1938 Mr. White moved to the country. On his farm in Maine he kept animals, and some of these creatures got into his stories and books. Mr. White said he found writing difficult and bad for one's disposition, but he kept at it. He began Stuart Little in the hope of amusing a six-year-old niece of his, but before he finished it, she had grown up.

For his total contribution to American letters, Mr. White was awarded the 1971 National Medal for Literature. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy named Mr. White as one of thirty-one Americans to receive the Presidential Medal for Freedom. Mr. White also received the National Institute of Arts and Letters' Gold Medal for Essays and Criticism, and in 1973 the members of the Institute elected him to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a society of fifty members. He also received honorary degrees from seven colleges and universities. Mr. White died on October 1, 1985.

Photo by White Literary LLC [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

Report an issue

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Here is New York

A series of 7 sensory videos filmed in New York City in 2019, accompanied by excerpts from E.B. White's essay "Here is New York" published in 1949.

Foreword from E.B. White

This piece about New York was written in the summer of 1948 during a hot spell. The reader will find certain observations to be no longer true of the city, owing to the passage of time and the swing of the pendulum. But the essential fever of New York has not changed in any particular, and I have not tried to make revisions in the hope of bringing the thing down to date. To bring New York down to date, a man would have to be published with the speed of light. I feel that it is the reader’s, not the author’s, duty to bring New York down to date; and I trust it will prove less a duty than a pleasure.

New York is nothing like Paris; it is nothing like London; and it is not Spokane multiplied by sixty, or Detroit multiplied by four.

It is by all odds the loftiest of cities. It even managed to reach the highest point in the sky at the lowest moment of the depression. The Empire State Building shot twelve hundred and fifty feet into the air when it was madness to put out as much as six inches of new growth. (The building has a mooring mast that no dirigible has ever tied to; it employs a man to flush toilets in slack times; it has even been hit by an airplane in a fog, struck countless times by lightning, and been jumped off of by so many unhappy people that pedestrians instinctively quicken step when passing Fifth Avenue and 34th Street.)

MANHATTAN • Brooklyn Bridge Park on a warm evening in June

The city is literally a composite of tens of thousands of tiny neighborhood units.

Each neighborhood is virtually self-sufficient. Usually it is no more than two or three blocks long and a couple of blocks wide. Each area is a city within a city within a city. Thus, no matter where you live in New York, you will find within a block or two a grocery store, a barbershop, a newsstand and shoeshine shack, and ice-coal-and-wood cellar, a dry cleaner, a laundry, a delicatessen, a flower shop, an undertaker’s parlor, a movie house, a radio-repair shop, a stationer, a haberdasher, a tailor, a drugstore, a garage, a tearoom, a soon, a hardware store, a liquor store, a shoe-repair shop.

Mass hysteria is a terrible force, yet New Yorkers seem always to escape it by some tiny margin.

They sit in stalled subways without claustrophobia, they extricate themselves from panic situations by some lucky wisecrack, they meet confusion and congestion with patience and grit—a sort of perpetual muddling through. Every facility is inadequate—the hospitals and schools and playgrounds are overcrowded, the express highways are feverish, the unimproved highways and bridges are bottlenecks; there is no enough air and not enough light, and there is usually either too much heat or too little. But the city makes up for its hazards and its deficiencies by supplying its citizens with massive doses of a supplementary vitamin—the sense of belonging to something unique, cosmopolitan, mighty and unparalleled.

New York blends the gift of privacy with the excitement of participation.

And better than most dense communities it succeeds in insulating the individual against all enormous and violent and wonderful events that are taking place every minute. New York is peculiarly constructed to absorb almost anything that comes along (whether a thousand-foot liner out of the East or a twenty-thousand-man convention out of the West) without inflicting the event on its inhabitants; so that every event is, in a sense, optional, and the inhabitant is in the happy position of being able to choose his spectacle and so conserve his soul. Whatever it means, it is a rather rare gift, and I believe it has a positive effect on the creative capacities of New Yorkers—for creation is in part merely the business of forgoing the great and small distractions.

Many people depend on the city’s tremendous variety and sources of excitement for spiritual sustenance and maintenance of morale.

In the country there are a few chances of sudden rejuvenation—a shift in weather, perhaps, or something arriving in the mail. But in New York the chances are endless. I think that although many persons are here from some excess of spirit (which caused them to break away from their small town), some, too, are here from a deficiency of spirit, who find in New York a protection, or an easy substitution.

The collision and the intermingling of millions of foreign-born people representing so many races and creeds make New York a permanent exhibit of the phenomenon of one world.

The citizens of New York are tolerant not only from disposition but from necessity. The city has to be tolerant, otherwise it would explode in a radioactive cloud of hate and rancor and bigotry. If the people were to depart even briefly from the peace of cosmopolitan intercourse, the town would blow up higher than a kite. In New York smolders every race problem there is, but the noticeable thing is not the problem but the inviolate truce.

The city is like poetry; it compresses all life, all races and breeds, into a small island and adds music and the accompaniment of internal engines.

The island of Manhattan is without any doubt the greatest human concentrate on earth, the poem whose magic is comprehensible to millions of permanent residents but whose full meaning will always remain elusive. At the feet of the tallest and plushiest offices lie the crummiest slums. The genteel mysteries housed in Riverside Church are only a few blocks from the voodoo charms of Harlem. The merchant princes, riding to Wall Street in their limousines down the East River Drive, pass within a few hundred yards of the gypsy kings; but the princes do not know they are passing kings, and the kings are not up yet anyway—they live a more leisurely life than the princes and get drunk more consistently.

About the Project

New York is a living, breathing organism, which leaves an undeniable impression on its residents. Although the city's hallmark is its unbridled movement, locals tend to forget this because they themselves are in constant motion. This video series captures the sights and sounds of places in New York from a still vantage point. During the editing process, we were reminded of E.B. White's beautiful essay about New York. As we reread it, we thought it was a perfect narration of the visuals. We included relevant excerpts that we found especially moving. We hope residents and visitors alike will enjoy a brief escape onto the streets of New York.

Credits Essay by E.B. White Video, Design, & Website by House of Wallis

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Letter of Recommendation

What I’ve Learned From My Students’ College Essays

The genre is often maligned for being formulaic and melodramatic, but it’s more important than you think.

By Nell Freudenberger

Most high school seniors approach the college essay with dread. Either their upbringing hasn’t supplied them with several hundred words of adversity, or worse, they’re afraid that packaging the genuine trauma they’ve experienced is the only way to secure their future. The college counselor at the Brooklyn high school where I’m a writing tutor advises against trauma porn. “Keep it brief , ” she says, “and show how you rose above it.”

I started volunteering in New York City schools in my 20s, before I had kids of my own. At the time, I liked hanging out with teenagers, whom I sometimes had more interesting conversations with than I did my peers. Often I worked with students who spoke English as a second language or who used slang in their writing, and at first I was hung up on grammar. Should I correct any deviation from “standard English” to appeal to some Wizard of Oz behind the curtains of a college admissions office? Or should I encourage students to write the way they speak, in pursuit of an authentic voice, that most elusive of literary qualities?

In fact, I was missing the point. One of many lessons the students have taught me is to let the story dictate the voice of the essay. A few years ago, I worked with a boy who claimed to have nothing to write about. His life had been ordinary, he said; nothing had happened to him. I asked if he wanted to try writing about a family member, his favorite school subject, a summer job? He glanced at his phone, his posture and expression suggesting that he’d rather be anywhere but in front of a computer with me. “Hobbies?” I suggested, without much hope. He gave me a shy glance. “I like to box,” he said.

I’ve had this experience with reluctant writers again and again — when a topic clicks with a student, an essay can unfurl spontaneously. Of course the primary goal of a college essay is to help its author get an education that leads to a career. Changes in testing policies and financial aid have made applying to college more confusing than ever, but essays have remained basically the same. I would argue that they’re much more than an onerous task or rote exercise, and that unlike standardized tests they are infinitely variable and sometimes beautiful. College essays also provide an opportunity to learn precision, clarity and the process of working toward the truth through multiple revisions.

When a topic clicks with a student, an essay can unfurl spontaneously.

Even if writing doesn’t end up being fundamental to their future professions, students learn to choose language carefully and to be suspicious of the first words that come to mind. Especially now, as college students shoulder so much of the country’s ethical responsibility for war with their protest movement, essay writing teaches prospective students an increasingly urgent lesson: that choosing their own words over ready-made phrases is the only reliable way to ensure they’re thinking for themselves.

Teenagers are ideal writers for several reasons. They’re usually free of preconceptions about writing, and they tend not to use self-consciously ‘‘literary’’ language. They’re allergic to hypocrisy and are generally unfiltered: They overshare, ask personal questions and call you out for microaggressions as well as less egregious (but still mortifying) verbal errors, such as referring to weed as ‘‘pot.’’ Most important, they have yet to put down their best stories in a finished form.

I can imagine an essay taking a risk and distinguishing itself formally — a poem or a one-act play — but most kids use a more straightforward model: a hook followed by a narrative built around “small moments” that lead to a concluding lesson or aspiration for the future. I never get tired of working with students on these essays because each one is different, and the short, rigid form sometimes makes an emotional story even more powerful. Before I read Javier Zamora’s wrenching “Solito,” I worked with a student who had been transported by a coyote into the U.S. and was reunited with his mother in the parking lot of a big-box store. I don’t remember whether this essay focused on specific skills or coping mechanisms that he gained from his ordeal. I remember only the bliss of the parent-and-child reunion in that uninspiring setting. If I were making a case to an admissions officer, I would suggest that simply being able to convey that experience demonstrates the kind of resilience that any college should admire.

The essays that have stayed with me over the years don’t follow a pattern. There are some narratives on very predictable topics — living up to the expectations of immigrant parents, or suffering from depression in 2020 — that are moving because of the attention with which the student describes the experience. One girl determined to become an engineer while watching her father build furniture from scraps after work; a boy, grieving for his mother during lockdown, began taking pictures of the sky.

If, as Lorrie Moore said, “a short story is a love affair; a novel is a marriage,” what is a college essay? Every once in a while I sit down next to a student and start reading, and I have to suppress my excitement, because there on the Google Doc in front of me is a real writer’s voice. One of the first students I ever worked with wrote about falling in love with another girl in dance class, the absolute magic of watching her move and the terror in the conflict between her feelings and the instruction of her religious middle school. She made me think that college essays are less like love than limerence: one-sided, obsessive, idiosyncratic but profound, the first draft of the most personal story their writers will ever tell.

Nell Freudenberger’s novel “The Limits” was published by Knopf last month. She volunteers through the PEN America Writers in the Schools program.

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

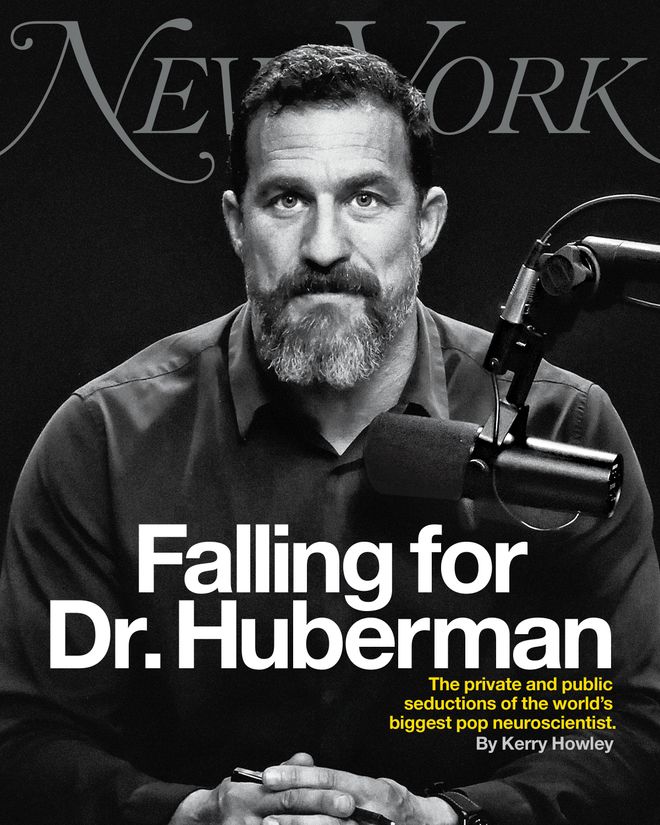

Andrew Huberman’s Mechanisms of Control

The private and public seductions of the world’s biggest pop neuroscientist..

This article was featured in One Great Story , New York ’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

For the past three years, one of the biggest podcasters on the planet has told a story to millions of listeners across half a dozen shows: There was a little boy, and the boy’s family was happy, until one day, the boy’s family fell apart. The boy was sent away. He foundered, he found therapy, he found science, he found exercise. And he became strong.

Today, Andrew Huberman is a stiff, jacked 48-year-old associate professor of neurology and ophthalmology at the Stanford University School of Medicine. He is given to delivering three-hour lectures on subjects such as “the health of our dopaminergic neurons.” His podcast is revelatory largely because it does not condescend, which has not been the way of public-health information in our time. He does not give the impression of someone diluting science to universally applicable sound bites for the slobbering masses. “Dopamine is vomited out into the synapse or it’s released volumetrically, but then it has to bind someplace and trigger those G-protein-coupled receptors, and caffeine increases the number, the density of those G-protein-coupled receptors,” is how he explains the effect of coffee before exercise in a two-hour-and-16-minute deep dive that has, as of this writing, nearly 8.9 million views on YouTube.

In This Issue

Falling for dr. huberman.

Millions of people feel compelled to hear him draw distinctions between neuromodulators and classical neurotransmitters. Many of those people will then adopt an associated “protocol.” They will follow his elaborate morning routine. They will model the most basic functions of human life — sleeping, eating, seeing — on his sober advice. They will tell their friends to do the same. “He’s not like other bro podcasters,” they will say, and they will be correct; he is a tenured Stanford professor associated with a Stanford lab; he knows the difference between a neuromodulator and a neurotransmitter. He is just back from a sold-out tour in Australia, where he filled the Sydney Opera House. Stanford, at one point, hung signs (AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY) apparently to deter fans in search of the lab.