- How it works

Published by Nicolas at March 21st, 2024 , Revised On March 12, 2024

The Ultimate Guide To Research Methodology

Research methodology is a crucial aspect of any investigative process, serving as the blueprint for the entire research journey. If you are stuck in the methodology section of your research paper , then this blog will guide you on what is a research methodology, its types and how to successfully conduct one.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Methodology?

Research methodology can be defined as the systematic framework that guides researchers in designing, conducting, and analyzing their investigations. It encompasses a structured set of processes, techniques, and tools employed to gather and interpret data, ensuring the reliability and validity of the research findings.

Research methodology is not confined to a singular approach; rather, it encapsulates a diverse range of methods tailored to the specific requirements of the research objectives.

Here is why Research methodology is important in academic and professional settings.

Facilitating Rigorous Inquiry

Research methodology forms the backbone of rigorous inquiry. It provides a structured approach that aids researchers in formulating precise thesis statements , selecting appropriate methodologies, and executing systematic investigations. This, in turn, enhances the quality and credibility of the research outcomes.

Ensuring Reproducibility And Reliability

In both academic and professional contexts, the ability to reproduce research outcomes is paramount. A well-defined research methodology establishes clear procedures, making it possible for others to replicate the study. This not only validates the findings but also contributes to the cumulative nature of knowledge.

Guiding Decision-Making Processes

In professional settings, decisions often hinge on reliable data and insights. Research methodology equips professionals with the tools to gather pertinent information, analyze it rigorously, and derive meaningful conclusions.

This informed decision-making is instrumental in achieving organizational goals and staying ahead in competitive environments.

Contributing To Academic Excellence

For academic researchers, adherence to robust research methodology is a hallmark of excellence. Institutions value research that adheres to high standards of methodology, fostering a culture of academic rigour and intellectual integrity. Furthermore, it prepares students with critical skills applicable beyond academia.

Enhancing Problem-Solving Abilities

Research methodology instills a problem-solving mindset by encouraging researchers to approach challenges systematically. It equips individuals with the skills to dissect complex issues, formulate hypotheses , and devise effective strategies for investigation.

Understanding Research Methodology

In the pursuit of knowledge and discovery, understanding the fundamentals of research methodology is paramount.

Basics Of Research

Research, in its essence, is a systematic and organized process of inquiry aimed at expanding our understanding of a particular subject or phenomenon. It involves the exploration of existing knowledge, the formulation of hypotheses, and the collection and analysis of data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Research is a dynamic and iterative process that contributes to the continuous evolution of knowledge in various disciplines.

Types of Research

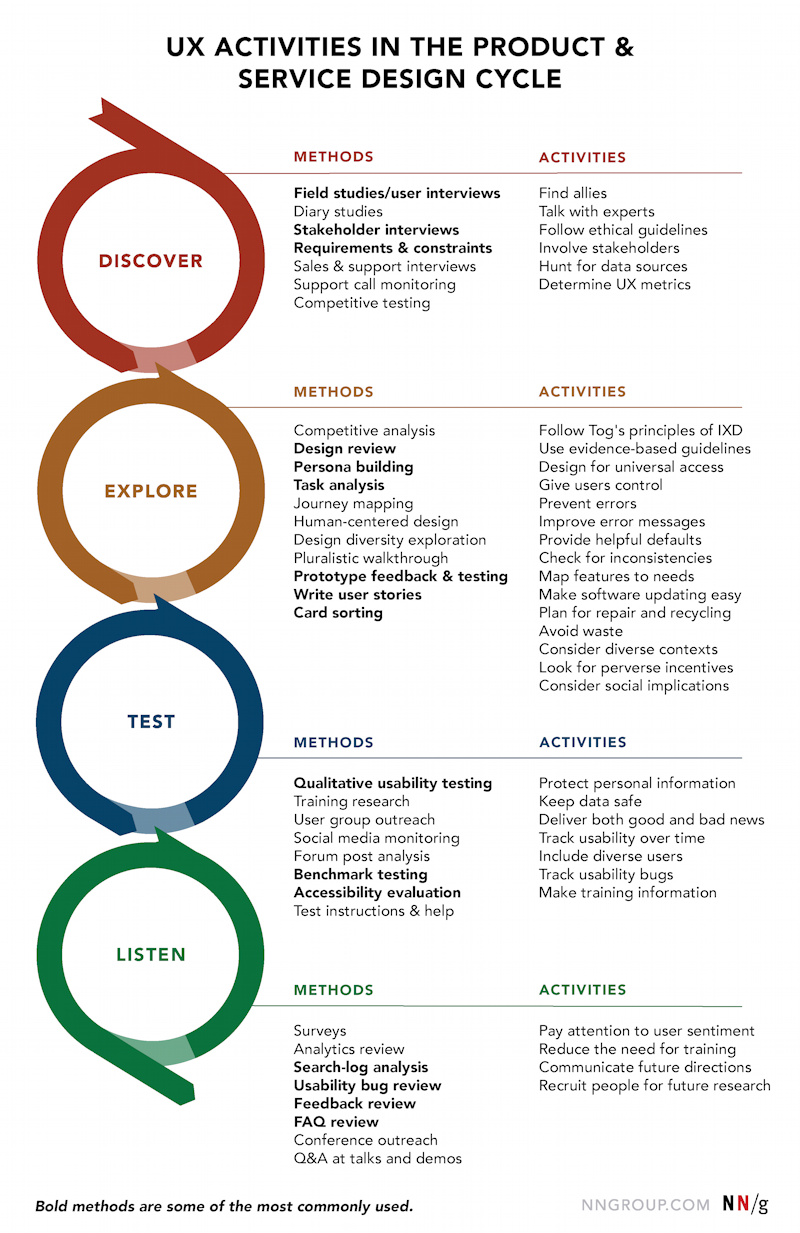

Research takes on various forms, each tailored to the nature of the inquiry. Broadly classified, research can be categorized into two main types:

- Quantitative Research: This type involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to identify patterns, relationships, and statistical significance. It is particularly useful for testing hypotheses and making predictions.

- Qualitative Research: Qualitative research focuses on understanding the depth and details of a phenomenon through non-numerical data. It often involves methods such as interviews, focus groups, and content analysis, providing rich insights into complex issues.

Components Of Research Methodology

To conduct effective research, one must go through the different components of research methodology. These components form the scaffolding that supports the entire research process, ensuring its coherence and validity.

Research Design

Research design serves as the blueprint for the entire research project. It outlines the overall structure and strategy for conducting the study. The three primary types of research design are:

- Exploratory Research: Aimed at gaining insights and familiarity with the topic, often used in the early stages of research.

- Descriptive Research: Involves portraying an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon, answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Explanatory Research: Seeks to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how.’

Data Collection Methods

Choosing the right data collection methods is crucial for obtaining reliable and relevant information. Common methods include:

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Employed to gather information from a large number of respondents through standardized questions.

- Interviews: In-depth conversations with participants, offering qualitative insights.

- Observation: Systematic watching and recording of behaviour, events, or processes in their natural setting.

Data Analysis Techniques

Once data is collected, analysis becomes imperative to derive meaningful conclusions. Different methodologies exist for quantitative and qualitative data:

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Involves statistical techniques such as descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, and regression analysis to interpret numerical data.

- Qualitative Data Analysis: Methods like content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory are employed to extract patterns, themes, and meanings from non-numerical data.

The research paper we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Choosing a Research Method

Selecting an appropriate research method is a critical decision in the research process. It determines the approach, tools, and techniques that will be used to answer the research questions.

Quantitative Research Methods

Quantitative research involves the collection and analysis of numerical data, providing a structured and objective approach to understanding and explaining phenomena.

Experimental Research

Experimental research involves manipulating variables to observe the effect on another variable under controlled conditions. It aims to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Key Characteristics:

- Controlled Environment: Experiments are conducted in a controlled setting to minimize external influences.

- Random Assignment: Participants are randomly assigned to different experimental conditions.

- Quantitative Data: Data collected is numerical, allowing for statistical analysis.

Applications: Commonly used in scientific studies and psychology to test hypotheses and identify causal relationships.

Survey Research

Survey research gathers information from a sample of individuals through standardized questionnaires or interviews. It aims to collect data on opinions, attitudes, and behaviours.

- Structured Instruments: Surveys use structured instruments, such as questionnaires, to collect data.

- Large Sample Size: Surveys often target a large and diverse group of participants.

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Responses are quantified for statistical analysis.

Applications: Widely employed in social sciences, marketing, and public opinion research to understand trends and preferences.

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research seeks to portray an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon. It focuses on answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Observation and Data Collection: This involves observing and documenting without manipulating variables.

- Objective Description: Aim to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: T his can include both types of data, depending on the research focus.

Applications: Useful in situations where researchers want to understand and describe a phenomenon without altering it, common in social sciences and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research emphasizes exploring and understanding the depth and complexity of phenomena through non-numerical data.

A case study is an in-depth exploration of a particular person, group, event, or situation. It involves detailed, context-rich analysis.

- Rich Data Collection: Uses various data sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents.

- Contextual Understanding: Aims to understand the context and unique characteristics of the case.

- Holistic Approach: Examines the case in its entirety.

Applications: Common in social sciences, psychology, and business to investigate complex and specific instances.

Ethnography

Ethnography involves immersing the researcher in the culture or community being studied to gain a deep understanding of their behaviours, beliefs, and practices.

- Participant Observation: Researchers actively participate in the community or setting.

- Holistic Perspective: Focuses on the interconnectedness of cultural elements.

- Qualitative Data: In-depth narratives and descriptions are central to ethnographic studies.

Applications: Widely used in anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies to explore and document cultural practices.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory aims to develop theories grounded in the data itself. It involves systematic data collection and analysis to construct theories from the ground up.

- Constant Comparison: Data is continually compared and analyzed during the research process.

- Inductive Reasoning: Theories emerge from the data rather than being imposed on it.

- Iterative Process: The research design evolves as the study progresses.

Applications: Commonly applied in sociology, nursing, and management studies to generate theories from empirical data.

Research design is the structural framework that outlines the systematic process and plan for conducting a study. It serves as the blueprint, guiding researchers on how to collect, analyze, and interpret data.

Exploratory, Descriptive, And Explanatory Designs

Exploratory design.

Exploratory research design is employed when a researcher aims to explore a relatively unknown subject or gain insights into a complex phenomenon.

- Flexibility: Allows for flexibility in data collection and analysis.

- Open-Ended Questions: Uses open-ended questions to gather a broad range of information.

- Preliminary Nature: Often used in the initial stages of research to formulate hypotheses.

Applications: Valuable in the early stages of investigation, especially when the researcher seeks a deeper understanding of a subject before formalizing research questions.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research design focuses on portraying an accurate profile of a situation, group, or phenomenon.

- Structured Data Collection: Involves systematic and structured data collection methods.

- Objective Presentation: Aims to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: Can incorporate both types of data, depending on the research objectives.

Applications: Widely used in social sciences, marketing, and educational research to provide detailed and objective descriptions.

Explanatory Design

Explanatory research design aims to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how’ behind observed relationships.

- Causal Relationships: Seeks to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Controlled Variables : Often involves controlling certain variables to isolate causal factors.

- Quantitative Analysis: Primarily relies on quantitative data analysis techniques.

Applications: Commonly employed in scientific studies and social sciences to delve into the underlying reasons behind observed patterns.

Cross-Sectional Vs. Longitudinal Designs

Cross-sectional design.

Cross-sectional designs collect data from participants at a single point in time.

- Snapshot View: Provides a snapshot of a population at a specific moment.

- Efficiency: More efficient in terms of time and resources.

- Limited Temporal Insights: Offers limited insights into changes over time.

Applications: Suitable for studying characteristics or behaviours that are stable or not expected to change rapidly.

Longitudinal Design

Longitudinal designs involve the collection of data from the same participants over an extended period.

- Temporal Sequence: Allows for the examination of changes over time.

- Causality Assessment: Facilitates the assessment of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Resource-Intensive: Requires more time and resources compared to cross-sectional designs.

Applications: Ideal for studying developmental processes, trends, or the impact of interventions over time.

Experimental Vs Non-experimental Designs

Experimental design.

Experimental designs involve manipulating variables under controlled conditions to observe the effect on another variable.

- Causality Inference: Enables the inference of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Quantitative Data: Primarily involves the collection and analysis of numerical data.

Applications: Commonly used in scientific studies, psychology, and medical research to establish causal relationships.

Non-Experimental Design

Non-experimental designs observe and describe phenomena without manipulating variables.

- Natural Settings: Data is often collected in natural settings without intervention.

- Descriptive or Correlational: Focuses on describing relationships or correlations between variables.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: This can involve either type of data, depending on the research approach.

Applications: Suitable for studying complex phenomena in real-world settings where manipulation may not be ethical or feasible.

Effective data collection is fundamental to the success of any research endeavour.

Designing Effective Surveys

Objective Design:

- Clearly define the research objectives to guide the survey design.

- Craft questions that align with the study’s goals and avoid ambiguity.

Structured Format:

- Use a structured format with standardized questions for consistency.

- Include a mix of closed-ended and open-ended questions for detailed insights.

Pilot Testing:

- Conduct pilot tests to identify and rectify potential issues with survey design.

- Ensure clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of questions.

Sampling Strategy:

- Develop a robust sampling strategy to ensure a representative participant group.

- Consider random sampling or stratified sampling based on the research goals.

Conducting Interviews

Establishing Rapport:

- Build rapport with participants to create a comfortable and open environment.

- Clearly communicate the purpose of the interview and the value of participants’ input.

Open-Ended Questions:

- Frame open-ended questions to encourage detailed responses.

- Allow participants to express their thoughts and perspectives freely.

Active Listening:

- Practice active listening to understand areas and gather rich data.

- Avoid interrupting and maintain a non-judgmental stance during the interview.

Ethical Considerations:

- Obtain informed consent and assure participants of confidentiality.

- Be transparent about the study’s purpose and potential implications.

Observation

1. participant observation.

Immersive Participation:

- Actively immerse yourself in the setting or group being observed.

- Develop a deep understanding of behaviours, interactions, and context.

Field Notes:

- Maintain detailed and reflective field notes during observations.

- Document observed patterns, unexpected events, and participant reactions.

Ethical Awareness:

- Be conscious of ethical considerations, ensuring respect for participants.

- Balance the role of observer and participant to minimize bias.

2. Non-participant Observation

Objective Observation:

- Maintain a more detached and objective stance during non-participant observation.

- Focus on recording behaviours, events, and patterns without direct involvement.

Data Reliability:

- Enhance the reliability of data by reducing observer bias.

- Develop clear observation protocols and guidelines.

Contextual Understanding:

- Strive for a thorough understanding of the observed context.

- Consider combining non-participant observation with other methods for triangulation.

Archival Research

1. using existing data.

Identifying Relevant Archives:

- Locate and access archives relevant to the research topic.

- Collaborate with institutions or repositories holding valuable data.

Data Verification:

- Verify the accuracy and reliability of archived data.

- Cross-reference with other sources to ensure data integrity.

Ethical Use:

- Adhere to ethical guidelines when using existing data.

- Respect copyright and intellectual property rights.

2. Challenges and Considerations

Incomplete or Inaccurate Archives:

- Address the possibility of incomplete or inaccurate archival records.

- Acknowledge limitations and uncertainties in the data.

Temporal Bias:

- Recognize potential temporal biases in archived data.

- Consider the historical context and changes that may impact interpretation.

Access Limitations:

- Address potential limitations in accessing certain archives.

- Seek alternative sources or collaborate with institutions to overcome barriers.

Common Challenges in Research Methodology

Conducting research is a complex and dynamic process, often accompanied by a myriad of challenges. Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensure the reliability and validity of research findings.

Sampling Issues

Sampling bias:.

- The presence of sampling bias can lead to an unrepresentative sample, affecting the generalizability of findings.

- Employ random sampling methods and ensure the inclusion of diverse participants to reduce bias.

Sample Size Determination:

- Determining an appropriate sample size is a delicate balance. Too small a sample may lack statistical power, while an excessively large sample may strain resources.

- Conduct a power analysis to determine the optimal sample size based on the research objectives and expected effect size.

Data Quality And Validity

Measurement error:.

- Inaccuracies in measurement tools or data collection methods can introduce measurement errors, impacting the validity of results.

- Pilot test instruments, calibrate equipment, and use standardized measures to enhance the reliability of data.

Construct Validity:

- Ensuring that the chosen measures accurately capture the intended constructs is a persistent challenge.

- Use established measurement instruments and employ multiple measures to assess the same construct for triangulation.

Time And Resource Constraints

Timeline pressures:.

- Limited timeframes can compromise the depth and thoroughness of the research process.

- Develop a realistic timeline, prioritize tasks, and communicate expectations with stakeholders to manage time constraints effectively.

Resource Availability:

- Inadequate resources, whether financial or human, can impede the execution of research activities.

- Seek external funding, collaborate with other researchers, and explore alternative methods that require fewer resources.

Managing Bias in Research

Selection bias:.

- Selecting participants in a way that systematically skews the sample can introduce selection bias.

- Employ randomization techniques, use stratified sampling, and transparently report participant recruitment methods.

Confirmation Bias:

- Researchers may unintentionally favour information that confirms their preconceived beliefs or hypotheses.

- Adopt a systematic and open-minded approach, use blinded study designs, and engage in peer review to mitigate confirmation bias.

Tips On How To Write A Research Methodology

Conducting successful research relies not only on the application of sound methodologies but also on strategic planning and effective collaboration. Here are some tips to enhance the success of your research methodology:

Tip 1. Clear Research Objectives

Well-defined research objectives guide the entire research process. Clearly articulate the purpose of your study, outlining specific research questions or hypotheses.

Tip 2. Comprehensive Literature Review

A thorough literature review provides a foundation for understanding existing knowledge and identifying gaps. Invest time in reviewing relevant literature to inform your research design and methodology.

Tip 3. Detailed Research Plan

A detailed plan serves as a roadmap, ensuring all aspects of the research are systematically addressed. Develop a detailed research plan outlining timelines, milestones, and tasks.

Tip 4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical practices are fundamental to maintaining the integrity of research. Address ethical considerations early, obtain necessary approvals, and ensure participant rights are safeguarded.

Tip 5. Stay Updated On Methodologies

Research methodologies evolve, and staying updated is essential for employing the most effective techniques. Engage in continuous learning by attending workshops, conferences, and reading recent publications.

Tip 6. Adaptability In Methods

Unforeseen challenges may arise during research, necessitating adaptability in methods. Be flexible and willing to modify your approach when needed, ensuring the integrity of the study.

Tip 7. Iterative Approach

Research is often an iterative process, and refining methods based on ongoing findings enhance the study’s robustness. Regularly review and refine your research design and methods as the study progresses.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the research methodology.

Research methodology is the systematic process of planning, executing, and evaluating scientific investigation. It encompasses the techniques, tools, and procedures used to collect, analyze, and interpret data, ensuring the reliability and validity of research findings.

What are the methodologies in research?

Research methodologies include qualitative and quantitative approaches. Qualitative methods involve in-depth exploration of non-numerical data, while quantitative methods use statistical analysis to examine numerical data. Mixed methods combine both approaches for a comprehensive understanding of research questions.

How to write research methodology?

To write a research methodology, clearly outline the study’s design, data collection, and analysis procedures. Specify research tools, participants, and sampling methods. Justify choices and discuss limitations. Ensure clarity, coherence, and alignment with research objectives for a robust methodology section.

How to write the methodology section of a research paper?

In the methodology section of a research paper, describe the study’s design, data collection, and analysis methods. Detail procedures, tools, participants, and sampling. Justify choices, address ethical considerations, and explain how the methodology aligns with research objectives, ensuring clarity and rigour.

What is mixed research methodology?

Mixed research methodology combines both qualitative and quantitative research approaches within a single study. This approach aims to enhance the details and depth of research findings by providing a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem or question.

You May Also Like

Discover Canadian doctoral dissertation format: structure, formatting, and word limits. Check your university guidelines.

What is a manuscript? A manuscript is a written or typed document, often the original draft of a book or article, before publication, undergoing editing and revisions.

Academic integrity: a commitment to honesty and ethical conduct in learning. Upholding originality and proper citation are its cornerstones.

Ready to place an order?

USEFUL LINKS

Learning resources, company details.

- How It Works

Automated page speed optimizations for fast site performance

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write Research Methodology

Last Updated: May 27, 2024 Approved

This article was co-authored by Alexander Ruiz, M.Ed. and by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD . Alexander Ruiz is an Educational Consultant and the Educational Director of Link Educational Institute, a tutoring business based in Claremont, California that provides customizable educational plans, subject and test prep tutoring, and college application consulting. With over a decade and a half of experience in the education industry, Alexander coaches students to increase their self-awareness and emotional intelligence while achieving skills and the goal of achieving skills and higher education. He holds a BA in Psychology from Florida International University and an MA in Education from Georgia Southern University. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, several readers have written to tell us that this article was helpful to them, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 522,885 times.

The research methodology section of any academic research paper gives you the opportunity to convince your readers that your research is useful and will contribute to your field of study. An effective research methodology is grounded in your overall approach – whether qualitative or quantitative – and adequately describes the methods you used. Justify why you chose those methods over others, then explain how those methods will provide answers to your research questions. [1] X Research source

Describing Your Methods

- In your restatement, include any underlying assumptions that you're making or conditions that you're taking for granted. These assumptions will also inform the research methods you've chosen.

- Generally, state the variables you'll test and the other conditions you're controlling or assuming are equal.

- If you want to research and document measurable social trends, or evaluate the impact of a particular policy on various variables, use a quantitative approach focused on data collection and statistical analysis.

- If you want to evaluate people's views or understanding of a particular issue, choose a more qualitative approach.

- You can also combine the two. For example, you might look primarily at a measurable social trend, but also interview people and get their opinions on how that trend is affecting their lives.

- For example, if you conducted a survey, you would describe the questions included in the survey, where and how the survey was conducted (such as in person, online, over the phone), how many surveys were distributed, and how long your respondents had to complete the survey.

- Include enough detail that your study can be replicated by others in your field, even if they may not get the same results you did. [4] X Research source

- Qualitative research methods typically require more detailed explanation than quantitative methods.

- Basic investigative procedures don't need to be explained in detail. Generally, you can assume that your readers have a general understanding of common research methods that social scientists use, such as surveys or focus groups.

- For example, suppose you conducted a survey and used a couple of other research papers to help construct the questions on your survey. You would mention those as contributing sources.

Justifying Your Choice of Methods

- Describe study participants specifically, and list any inclusion or exclusion criteria you used when forming your group of participants.

- Justify the size of your sample, if applicable, and describe how this affects whether your study can be generalized to larger populations. For example, if you conducted a survey of 30 percent of the student population of a university, you could potentially apply those results to the student body as a whole, but maybe not to students at other universities.

- Reading other research papers is a good way to identify potential problems that commonly arise with various methods. State whether you actually encountered any of these common problems during your research.

- If you encountered any problems as you collected data, explain clearly the steps you took to minimize the effect that problem would have on your results.

- In some cases, this may be as simple as stating that while there were numerous studies using one method, there weren't any using your method, which caused a gap in understanding of the issue.

- For example, there may be multiple papers providing quantitative analysis of a particular social trend. However, none of these papers looked closely at how this trend was affecting the lives of people.

Connecting Your Methods to Your Research Goals

- Depending on your research questions, you may be mixing quantitative and qualitative analysis – just as you could potentially use both approaches. For example, you might do a statistical analysis, and then interpret those statistics through a particular theoretical lens.

- For example, suppose you're researching the effect of college education on family farms in rural America. While you could do interviews of college-educated people who grew up on a family farm, that would not give you a picture of the overall effect. A quantitative approach and statistical analysis would give you a bigger picture.

- If in answering your research questions, your findings have raised other questions that may require further research, state these briefly.

- You can also include here any limitations to your methods, or questions that weren't answered through your research.

- Generalization is more typically used in quantitative research. If you have a well-designed sample, you can statistically apply your results to the larger population your sample belongs to.

Template to Write Research Methodology

Community Q&A

- Organize your methodology section chronologically, starting with how you prepared to conduct your research methods, how you gathered data, and how you analyzed that data. [13] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Write your research methodology section in past tense, unless you're submitting the methodology section before the research described has been carried out. [14] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Discuss your plans in detail with your advisor or supervisor before committing to a particular methodology. They can help identify possible flaws in your study. [15] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://expertjournals.com/how-to-write-a-research-methodology-for-your-academic-article/

- ↑ http://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/methodology

- ↑ https://www.skillsyouneed.com/learn/dissertation-methodology.html

- ↑ https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/4245/05Chap%204_Research%20methodology%20and%20design.pdf

- ↑ https://elc.polyu.edu.hk/FYP/html/method.htm

About This Article

To write a research methodology, start with a section that outlines the problems or questions you'll be studying, including your hypotheses or whatever it is you're setting out to prove. Then, briefly explain why you chose to use either a qualitative or quantitative approach for your study. Next, go over when and where you conducted your research and what parameters you used to ensure you were objective. Finally, cite any sources you used to decide on the methodology for your research. To learn how to justify your choice of methods in your research methodology, scroll down! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Prof. Dr. Ahmed Askar

Apr 18, 2020

Did this article help you?

M. Mahmood Shah Khan

Mar 17, 2020

Shimola Makondo

Jul 20, 2019

Zain Sharif Mohammed Alnadhery

Jan 7, 2019

Lundi Dukashe

Feb 17, 2020

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Methods | Definition, Types, Examples

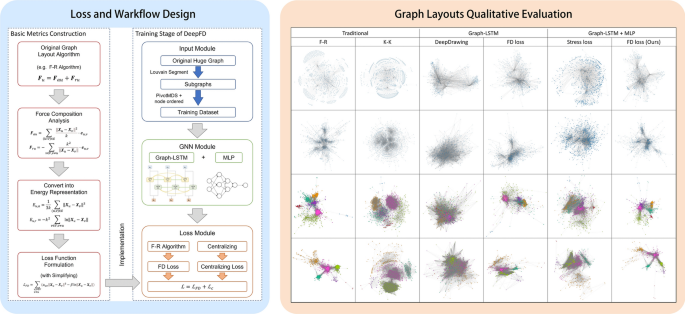

Research methods are specific procedures for collecting and analysing data. Developing your research methods is an integral part of your research design . When planning your methods, there are two key decisions you will make.

First, decide how you will collect data . Your methods depend on what type of data you need to answer your research question :

- Qualitative vs quantitative : Will your data take the form of words or numbers?

- Primary vs secondary : Will you collect original data yourself, or will you use data that have already been collected by someone else?

- Descriptive vs experimental : Will you take measurements of something as it is, or will you perform an experiment?

Second, decide how you will analyse the data .

- For quantitative data, you can use statistical analysis methods to test relationships between variables.

- For qualitative data, you can use methods such as thematic analysis to interpret patterns and meanings in the data.

Table of contents

Methods for collecting data, examples of data collection methods, methods for analysing data, examples of data analysis methods, frequently asked questions about methodology.

Data are the information that you collect for the purposes of answering your research question . The type of data you need depends on the aims of your research.

Qualitative vs quantitative data

Your choice of qualitative or quantitative data collection depends on the type of knowledge you want to develop.

For questions about ideas, experiences and meanings, or to study something that can’t be described numerically, collect qualitative data .

If you want to develop a more mechanistic understanding of a topic, or your research involves hypothesis testing , collect quantitative data .

You can also take a mixed methods approach, where you use both qualitative and quantitative research methods.

Primary vs secondary data

Primary data are any original information that you collect for the purposes of answering your research question (e.g. through surveys , observations and experiments ). Secondary data are information that has already been collected by other researchers (e.g. in a government census or previous scientific studies).

If you are exploring a novel research question, you’ll probably need to collect primary data. But if you want to synthesise existing knowledge, analyse historical trends, or identify patterns on a large scale, secondary data might be a better choice.

Descriptive vs experimental data

In descriptive research , you collect data about your study subject without intervening. The validity of your research will depend on your sampling method .

In experimental research , you systematically intervene in a process and measure the outcome. The validity of your research will depend on your experimental design .

To conduct an experiment, you need to be able to vary your independent variable , precisely measure your dependent variable, and control for confounding variables . If it’s practically and ethically possible, this method is the best choice for answering questions about cause and effect.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Your data analysis methods will depend on the type of data you collect and how you prepare them for analysis.

Data can often be analysed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For example, survey responses could be analysed qualitatively by studying the meanings of responses or quantitatively by studying the frequencies of responses.

Qualitative analysis methods

Qualitative analysis is used to understand words, ideas, and experiences. You can use it to interpret data that were collected:

- From open-ended survey and interview questions, literature reviews, case studies, and other sources that use text rather than numbers.

- Using non-probability sampling methods .

Qualitative analysis tends to be quite flexible and relies on the researcher’s judgement, so you have to reflect carefully on your choices and assumptions.

Quantitative analysis methods

Quantitative analysis uses numbers and statistics to understand frequencies, averages and correlations (in descriptive studies) or cause-and-effect relationships (in experiments).

You can use quantitative analysis to interpret data that were collected either:

- During an experiment.

- Using probability sampling methods .

Because the data are collected and analysed in a statistically valid way, the results of quantitative analysis can be easily standardised and shared among researchers.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research project . It involves studying the methods used in your field and the theories or principles behind them, in order to develop an approach that matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyse data (e.g. experiments, surveys , and statistical tests ).

In shorter scientific papers, where the aim is to report the findings of a specific study, you might simply describe what you did in a methods section .

In a longer or more complex research project, such as a thesis or dissertation , you will probably include a methodology section , where you explain your approach to answering the research questions and cite relevant sources to support your choice of methods.

Is this article helpful?

More interesting articles.

- A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples

- Between-Subjects Design | Examples, Pros & Cons

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

- Cluster Sampling | A Simple Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Confounding Variables | Definition, Examples & Controls

- Construct Validity | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Content Analysis | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Control Groups and Treatment Groups | Uses & Examples

- Controlled Experiments | Methods & Examples of Control

- Correlation vs Causation | Differences, Designs & Examples

- Correlational Research | Guide, Design & Examples

- Critical Discourse Analysis | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Cross-Sectional Study | Definitions, Uses & Examples

- Data Cleaning | A Guide with Examples & Steps

- Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

- Explanatory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- Explanatory vs Response Variables | Definitions & Examples

- Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- External Validity | Types, Threats & Examples

- Extraneous Variables | Examples, Types, Controls

- Face Validity | Guide with Definition & Examples

- How to Do Thematic Analysis | Guide & Examples

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Examples & Definition

- Independent vs Dependent Variables | Definition & Examples

- Inductive Reasoning | Types, Examples, Explanation

- Inductive vs Deductive Research Approach (with Examples)

- Internal Validity | Definition, Threats & Examples

- Internal vs External Validity | Understanding Differences & Examples

- Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

- Mediator vs Moderator Variables | Differences & Examples

- Mixed Methods Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- Multistage Sampling | An Introductory Guide with Examples

- Naturalistic Observation | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Population vs Sample | Definitions, Differences & Examples

- Primary Research | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

- Quasi-Experimental Design | Definition, Types & Examples

- Questionnaire Design | Methods, Question Types & Examples

- Random Assignment in Experiments | Introduction & Examples

- Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples

- Reproducibility vs Replicability | Difference & Examples

- Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques, & Examples

- Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Simple Random Sampling | Definition, Steps & Examples

- Stratified Sampling | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

- Systematic Sampling | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Textual Analysis | Guide, 3 Approaches & Examples

- The 4 Types of Reliability in Research | Definitions & Examples

- The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

- Transcribing an Interview | 5 Steps & Transcription Software

- Triangulation in Research | Guide, Types, Examples

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

- Types of Research Designs Compared | Examples

- Types of Variables in Research | Definitions & Examples

- Unstructured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- What Are Control Variables | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

- What Is a Double-Barrelled Question?

- What Is a Double-Blind Study? | Introduction & Examples

- What Is a Focus Group? | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- What Is a Likert Scale? | Guide & Examples

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- What Is a Prospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

- What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

- What Is Concurrent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convenience Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convergent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Criterion Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Deductive Reasoning? | Explanation & Examples

- What Is Discriminant Validity? | Definition & Example

- What Is Ecological Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Ethnography? | Meaning, Guide & Examples

- What Is Non-Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

- What Is Predictive Validity? | Examples & Definition

- What Is Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Purposive Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition & Methods

- What Is Quota Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

- What Is Snowball Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- Within-Subjects Design | Explanation, Approaches, Examples

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is Research Methodology? Definition, Types, and Examples

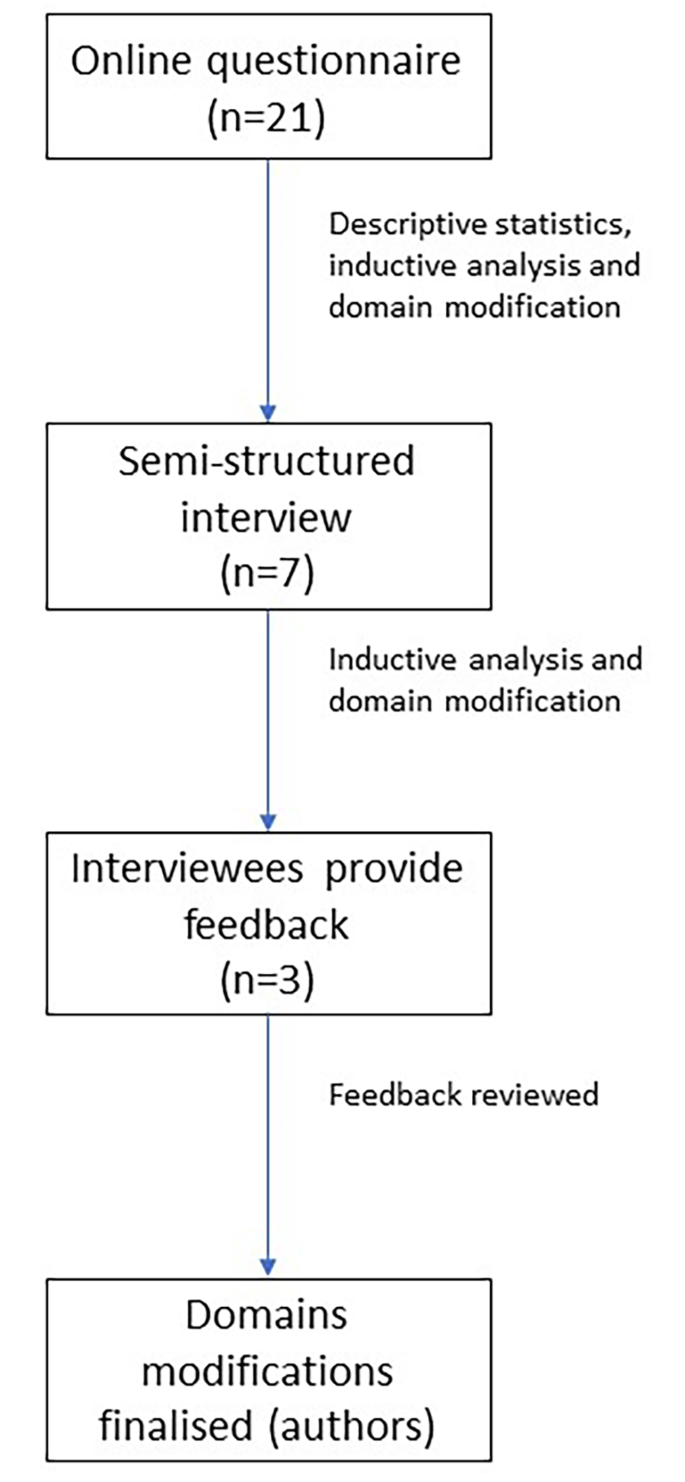

Research methodology 1,2 is a structured and scientific approach used to collect, analyze, and interpret quantitative or qualitative data to answer research questions or test hypotheses. A research methodology is like a plan for carrying out research and helps keep researchers on track by limiting the scope of the research. Several aspects must be considered before selecting an appropriate research methodology, such as research limitations and ethical concerns that may affect your research.

The research methodology section in a scientific paper describes the different methodological choices made, such as the data collection and analysis methods, and why these choices were selected. The reasons should explain why the methods chosen are the most appropriate to answer the research question. A good research methodology also helps ensure the reliability and validity of the research findings. There are three types of research methodology—quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method, which can be chosen based on the research objectives.

What is research methodology ?

A research methodology describes the techniques and procedures used to identify and analyze information regarding a specific research topic. It is a process by which researchers design their study so that they can achieve their objectives using the selected research instruments. It includes all the important aspects of research, including research design, data collection methods, data analysis methods, and the overall framework within which the research is conducted. While these points can help you understand what is research methodology, you also need to know why it is important to pick the right methodology.

Why is research methodology important?

Having a good research methodology in place has the following advantages: 3

- Helps other researchers who may want to replicate your research; the explanations will be of benefit to them.

- You can easily answer any questions about your research if they arise at a later stage.

- A research methodology provides a framework and guidelines for researchers to clearly define research questions, hypotheses, and objectives.

- It helps researchers identify the most appropriate research design, sampling technique, and data collection and analysis methods.

- A sound research methodology helps researchers ensure that their findings are valid and reliable and free from biases and errors.

- It also helps ensure that ethical guidelines are followed while conducting research.

- A good research methodology helps researchers in planning their research efficiently, by ensuring optimum usage of their time and resources.

Writing the methods section of a research paper? Let Paperpal help you achieve perfection

Types of research methodology.

There are three types of research methodology based on the type of research and the data required. 1

- Quantitative research methodology focuses on measuring and testing numerical data. This approach is good for reaching a large number of people in a short amount of time. This type of research helps in testing the causal relationships between variables, making predictions, and generalizing results to wider populations.

- Qualitative research methodology examines the opinions, behaviors, and experiences of people. It collects and analyzes words and textual data. This research methodology requires fewer participants but is still more time consuming because the time spent per participant is quite large. This method is used in exploratory research where the research problem being investigated is not clearly defined.

- Mixed-method research methodology uses the characteristics of both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies in the same study. This method allows researchers to validate their findings, verify if the results observed using both methods are complementary, and explain any unexpected results obtained from one method by using the other method.

What are the types of sampling designs in research methodology?

Sampling 4 is an important part of a research methodology and involves selecting a representative sample of the population to conduct the study, making statistical inferences about them, and estimating the characteristics of the whole population based on these inferences. There are two types of sampling designs in research methodology—probability and nonprobability.

- Probability sampling

In this type of sampling design, a sample is chosen from a larger population using some form of random selection, that is, every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. The different types of probability sampling are:

- Systematic —sample members are chosen at regular intervals. It requires selecting a starting point for the sample and sample size determination that can be repeated at regular intervals. This type of sampling method has a predefined range; hence, it is the least time consuming.

- Stratified —researchers divide the population into smaller groups that don’t overlap but represent the entire population. While sampling, these groups can be organized, and then a sample can be drawn from each group separately.

- Cluster —the population is divided into clusters based on demographic parameters like age, sex, location, etc.

- Convenience —selects participants who are most easily accessible to researchers due to geographical proximity, availability at a particular time, etc.

- Purposive —participants are selected at the researcher’s discretion. Researchers consider the purpose of the study and the understanding of the target audience.

- Snowball —already selected participants use their social networks to refer the researcher to other potential participants.

- Quota —while designing the study, the researchers decide how many people with which characteristics to include as participants. The characteristics help in choosing people most likely to provide insights into the subject.

What are data collection methods?

During research, data are collected using various methods depending on the research methodology being followed and the research methods being undertaken. Both qualitative and quantitative research have different data collection methods, as listed below.

Qualitative research 5

- One-on-one interviews: Helps the interviewers understand a respondent’s subjective opinion and experience pertaining to a specific topic or event

- Document study/literature review/record keeping: Researchers’ review of already existing written materials such as archives, annual reports, research articles, guidelines, policy documents, etc.

- Focus groups: Constructive discussions that usually include a small sample of about 6-10 people and a moderator, to understand the participants’ opinion on a given topic.

- Qualitative observation : Researchers collect data using their five senses (sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing).

Quantitative research 6

- Sampling: The most common type is probability sampling.

- Interviews: Commonly telephonic or done in-person.

- Observations: Structured observations are most commonly used in quantitative research. In this method, researchers make observations about specific behaviors of individuals in a structured setting.

- Document review: Reviewing existing research or documents to collect evidence for supporting the research.

- Surveys and questionnaires. Surveys can be administered both online and offline depending on the requirement and sample size.

Let Paperpal help you write the perfect research methods section. Start now!

What are data analysis methods.

The data collected using the various methods for qualitative and quantitative research need to be analyzed to generate meaningful conclusions. These data analysis methods 7 also differ between quantitative and qualitative research.

Quantitative research involves a deductive method for data analysis where hypotheses are developed at the beginning of the research and precise measurement is required. The methods include statistical analysis applications to analyze numerical data and are grouped into two categories—descriptive and inferential.

Descriptive analysis is used to describe the basic features of different types of data to present it in a way that ensures the patterns become meaningful. The different types of descriptive analysis methods are:

- Measures of frequency (count, percent, frequency)

- Measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode)

- Measures of dispersion or variation (range, variance, standard deviation)

- Measure of position (percentile ranks, quartile ranks)

Inferential analysis is used to make predictions about a larger population based on the analysis of the data collected from a smaller population. This analysis is used to study the relationships between different variables. Some commonly used inferential data analysis methods are:

- Correlation: To understand the relationship between two or more variables.

- Cross-tabulation: Analyze the relationship between multiple variables.

- Regression analysis: Study the impact of independent variables on the dependent variable.

- Frequency tables: To understand the frequency of data.

- Analysis of variance: To test the degree to which two or more variables differ in an experiment.

Qualitative research involves an inductive method for data analysis where hypotheses are developed after data collection. The methods include:

- Content analysis: For analyzing documented information from text and images by determining the presence of certain words or concepts in texts.

- Narrative analysis: For analyzing content obtained from sources such as interviews, field observations, and surveys. The stories and opinions shared by people are used to answer research questions.

- Discourse analysis: For analyzing interactions with people considering the social context, that is, the lifestyle and environment, under which the interaction occurs.

- Grounded theory: Involves hypothesis creation by data collection and analysis to explain why a phenomenon occurred.

- Thematic analysis: To identify important themes or patterns in data and use these to address an issue.

How to choose a research methodology?

Here are some important factors to consider when choosing a research methodology: 8

- Research objectives, aims, and questions —these would help structure the research design.

- Review existing literature to identify any gaps in knowledge.

- Check the statistical requirements —if data-driven or statistical results are needed then quantitative research is the best. If the research questions can be answered based on people’s opinions and perceptions, then qualitative research is most suitable.

- Sample size —sample size can often determine the feasibility of a research methodology. For a large sample, less effort- and time-intensive methods are appropriate.

- Constraints —constraints of time, geography, and resources can help define the appropriate methodology.

Got writer’s block? Kickstart your research paper writing with Paperpal now!

How to write a research methodology .

A research methodology should include the following components: 3,9

- Research design —should be selected based on the research question and the data required. Common research designs include experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational, descriptive, and exploratory.

- Research method —this can be quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method.

- Reason for selecting a specific methodology —explain why this methodology is the most suitable to answer your research problem.

- Research instruments —explain the research instruments you plan to use, mainly referring to the data collection methods such as interviews, surveys, etc. Here as well, a reason should be mentioned for selecting the particular instrument.

- Sampling —this involves selecting a representative subset of the population being studied.

- Data collection —involves gathering data using several data collection methods, such as surveys, interviews, etc.

- Data analysis —describe the data analysis methods you will use once you’ve collected the data.

- Research limitations —mention any limitations you foresee while conducting your research.

- Validity and reliability —validity helps identify the accuracy and truthfulness of the findings; reliability refers to the consistency and stability of the results over time and across different conditions.

- Ethical considerations —research should be conducted ethically. The considerations include obtaining consent from participants, maintaining confidentiality, and addressing conflicts of interest.

Streamline Your Research Paper Writing Process with Paperpal

The methods section is a critical part of the research papers, allowing researchers to use this to understand your findings and replicate your work when pursuing their own research. However, it is usually also the most difficult section to write. This is where Paperpal can help you overcome the writer’s block and create the first draft in minutes with Paperpal Copilot, its secure generative AI feature suite.

With Paperpal you can get research advice, write and refine your work, rephrase and verify the writing, and ensure submission readiness, all in one place. Here’s how you can use Paperpal to develop the first draft of your methods section.

- Generate an outline: Input some details about your research to instantly generate an outline for your methods section

- Develop the section: Use the outline and suggested sentence templates to expand your ideas and develop the first draft.

- P araph ras e and trim : Get clear, concise academic text with paraphrasing that conveys your work effectively and word reduction to fix redundancies.

- Choose the right words: Enhance text by choosing contextual synonyms based on how the words have been used in previously published work.

- Check and verify text : Make sure the generated text showcases your methods correctly, has all the right citations, and is original and authentic. .

You can repeat this process to develop each section of your research manuscript, including the title, abstract and keywords. Ready to write your research papers faster, better, and without the stress? Sign up for Paperpal and start writing today!

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. What are the key components of research methodology?

A1. A good research methodology has the following key components:

- Research design

- Data collection procedures

- Data analysis methods

- Ethical considerations

Q2. Why is ethical consideration important in research methodology?

A2. Ethical consideration is important in research methodology to ensure the readers of the reliability and validity of the study. Researchers must clearly mention the ethical norms and standards followed during the conduct of the research and also mention if the research has been cleared by any institutional board. The following 10 points are the important principles related to ethical considerations: 10

- Participants should not be subjected to harm.

- Respect for the dignity of participants should be prioritized.

- Full consent should be obtained from participants before the study.

- Participants’ privacy should be ensured.

- Confidentiality of the research data should be ensured.

- Anonymity of individuals and organizations participating in the research should be maintained.

- The aims and objectives of the research should not be exaggerated.

- Affiliations, sources of funding, and any possible conflicts of interest should be declared.

- Communication in relation to the research should be honest and transparent.

- Misleading information and biased representation of primary data findings should be avoided.

Q3. What is the difference between methodology and method?

A3. Research methodology is different from a research method, although both terms are often confused. Research methods are the tools used to gather data, while the research methodology provides a framework for how research is planned, conducted, and analyzed. The latter guides researchers in making decisions about the most appropriate methods for their research. Research methods refer to the specific techniques, procedures, and tools used by researchers to collect, analyze, and interpret data, for instance surveys, questionnaires, interviews, etc.

Research methodology is, thus, an integral part of a research study. It helps ensure that you stay on track to meet your research objectives and answer your research questions using the most appropriate data collection and analysis tools based on your research design.

Accelerate your research paper writing with Paperpal. Try for free now!

- Research methodologies. Pfeiffer Library website. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://library.tiffin.edu/researchmethodologies/whatareresearchmethodologies

- Types of research methodology. Eduvoice website. Accessed August 16, 2023. https://eduvoice.in/types-research-methodology/

- The basics of research methodology: A key to quality research. Voxco. Accessed August 16, 2023. https://www.voxco.com/blog/what-is-research-methodology/

- Sampling methods: Types with examples. QuestionPro website. Accessed August 16, 2023. https://www.questionpro.com/blog/types-of-sampling-for-social-research/

- What is qualitative research? Methods, types, approaches, examples. Researcher.Life blog. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://researcher.life/blog/article/what-is-qualitative-research-methods-types-examples/

- What is quantitative research? Definition, methods, types, and examples. Researcher.Life blog. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://researcher.life/blog/article/what-is-quantitative-research-types-and-examples/

- Data analysis in research: Types & methods. QuestionPro website. Accessed August 16, 2023. https://www.questionpro.com/blog/data-analysis-in-research/#Data_analysis_in_qualitative_research

- Factors to consider while choosing the right research methodology. PhD Monster website. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.phdmonster.com/factors-to-consider-while-choosing-the-right-research-methodology/

- What is research methodology? Research and writing guides. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://paperpile.com/g/what-is-research-methodology/

- Ethical considerations. Business research methodology website. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://research-methodology.net/research-methodology/ethical-considerations/

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Dangling Modifiers and How to Avoid Them in Your Writing

- Webinar: How to Use Generative AI Tools Ethically in Your Academic Writing

- Research Outlines: How to Write An Introduction Section in Minutes with Paperpal Copilot

- How to Paraphrase Research Papers Effectively

Language and Grammar Rules for Academic Writing

Climatic vs. climactic: difference and examples, you may also like, mla works cited page: format, template & examples, how to ace grant writing for research funding..., powerful academic phrases to improve your essay writing , how to write a high-quality conference paper, how paperpal is enhancing academic productivity and accelerating..., academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples , what is academic writing: tips for students.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is research methodology?

The basics of research methodology

Why do you need a research methodology, what needs to be included, why do you need to document your research method, what are the different types of research instruments, qualitative / quantitative / mixed research methodologies, how do you choose the best research methodology for you, frequently asked questions about research methodology, related articles.

When you’re working on your first piece of academic research, there are many different things to focus on, and it can be overwhelming to stay on top of everything. This is especially true of budding or inexperienced researchers.

If you’ve never put together a research proposal before or find yourself in a position where you need to explain your research methodology decisions, there are a few things you need to be aware of.

Once you understand the ins and outs, handling academic research in the future will be less intimidating. We break down the basics below:

A research methodology encompasses the way in which you intend to carry out your research. This includes how you plan to tackle things like collection methods, statistical analysis, participant observations, and more.

You can think of your research methodology as being a formula. One part will be how you plan on putting your research into practice, and another will be why you feel this is the best way to approach it. Your research methodology is ultimately a methodological and systematic plan to resolve your research problem.

In short, you are explaining how you will take your idea and turn it into a study, which in turn will produce valid and reliable results that are in accordance with the aims and objectives of your research. This is true whether your paper plans to make use of qualitative methods or quantitative methods.

The purpose of a research methodology is to explain the reasoning behind your approach to your research - you'll need to support your collection methods, methods of analysis, and other key points of your work.

Think of it like writing a plan or an outline for you what you intend to do.

When carrying out research, it can be easy to go off-track or depart from your standard methodology.

Tip: Having a methodology keeps you accountable and on track with your original aims and objectives, and gives you a suitable and sound plan to keep your project manageable, smooth, and effective.

With all that said, how do you write out your standard approach to a research methodology?

As a general plan, your methodology should include the following information:

- Your research method. You need to state whether you plan to use quantitative analysis, qualitative analysis, or mixed-method research methods. This will often be determined by what you hope to achieve with your research.

- Explain your reasoning. Why are you taking this methodological approach? Why is this particular methodology the best way to answer your research problem and achieve your objectives?

- Explain your instruments. This will mainly be about your collection methods. There are varying instruments to use such as interviews, physical surveys, questionnaires, for example. Your methodology will need to detail your reasoning in choosing a particular instrument for your research.

- What will you do with your results? How are you going to analyze the data once you have gathered it?

- Advise your reader. If there is anything in your research methodology that your reader might be unfamiliar with, you should explain it in more detail. For example, you should give any background information to your methods that might be relevant or provide your reasoning if you are conducting your research in a non-standard way.

- How will your sampling process go? What will your sampling procedure be and why? For example, if you will collect data by carrying out semi-structured or unstructured interviews, how will you choose your interviewees and how will you conduct the interviews themselves?

- Any practical limitations? You should discuss any limitations you foresee being an issue when you’re carrying out your research.

In any dissertation, thesis, or academic journal, you will always find a chapter dedicated to explaining the research methodology of the person who carried out the study, also referred to as the methodology section of the work.

A good research methodology will explain what you are going to do and why, while a poor methodology will lead to a messy or disorganized approach.

You should also be able to justify in this section your reasoning for why you intend to carry out your research in a particular way, especially if it might be a particularly unique method.

Having a sound methodology in place can also help you with the following:

- When another researcher at a later date wishes to try and replicate your research, they will need your explanations and guidelines.

- In the event that you receive any criticism or questioning on the research you carried out at a later point, you will be able to refer back to it and succinctly explain the how and why of your approach.

- It provides you with a plan to follow throughout your research. When you are drafting your methodology approach, you need to be sure that the method you are using is the right one for your goal. This will help you with both explaining and understanding your method.

- It affords you the opportunity to document from the outset what you intend to achieve with your research, from start to finish.

A research instrument is a tool you will use to help you collect, measure and analyze the data you use as part of your research.

The choice of research instrument will usually be yours to make as the researcher and will be whichever best suits your methodology.

There are many different research instruments you can use in collecting data for your research.

Generally, they can be grouped as follows:

- Interviews (either as a group or one-on-one). You can carry out interviews in many different ways. For example, your interview can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. The difference between them is how formal the set of questions is that is asked of the interviewee. In a group interview, you may choose to ask the interviewees to give you their opinions or perceptions on certain topics.

- Surveys (online or in-person). In survey research, you are posing questions in which you ask for a response from the person taking the survey. You may wish to have either free-answer questions such as essay-style questions, or you may wish to use closed questions such as multiple choice. You may even wish to make the survey a mixture of both.

- Focus Groups. Similar to the group interview above, you may wish to ask a focus group to discuss a particular topic or opinion while you make a note of the answers given.

- Observations. This is a good research instrument to use if you are looking into human behaviors. Different ways of researching this include studying the spontaneous behavior of participants in their everyday life, or something more structured. A structured observation is research conducted at a set time and place where researchers observe behavior as planned and agreed upon with participants.

These are the most common ways of carrying out research, but it is really dependent on your needs as a researcher and what approach you think is best to take.

It is also possible to combine a number of research instruments if this is necessary and appropriate in answering your research problem.

There are three different types of methodologies, and they are distinguished by whether they focus on words, numbers, or both.

➡️ Want to learn more about the differences between qualitative and quantitative research, and how to use both methods? Check out our guide for that!

If you've done your due diligence, you'll have an idea of which methodology approach is best suited to your research.

It’s likely that you will have carried out considerable reading and homework before you reach this point and you may have taken inspiration from other similar studies that have yielded good results.

Still, it is important to consider different options before setting your research in stone. Exploring different options available will help you to explain why the choice you ultimately make is preferable to other methods.

If proving your research problem requires you to gather large volumes of numerical data to test hypotheses, a quantitative research method is likely to provide you with the most usable results.

If instead you’re looking to try and learn more about people, and their perception of events, your methodology is more exploratory in nature and would therefore probably be better served using a qualitative research methodology.

It helps to always bring things back to the question: what do I want to achieve with my research?

Once you have conducted your research, you need to analyze it. Here are some helpful guides for qualitative data analysis:

➡️ How to do a content analysis

➡️ How to do a thematic analysis

➡️ How to do a rhetorical analysis

Research methodology refers to the techniques used to find and analyze information for a study, ensuring that the results are valid, reliable and that they address the research objective.

Data can typically be organized into four different categories or methods: observational, experimental, simulation, and derived.

Writing a methodology section is a process of introducing your methods and instruments, discussing your analysis, providing more background information, addressing your research limitations, and more.