Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is Qualitative Research? Methods, Types, Approaches and Examples

Qualitative research is a type of method that researchers use depending on their study requirements. Research can be conducted using several methods, but before starting the process, researchers should understand the different methods available to decide the best one for their study type. The type of research method needed depends on a few important criteria, such as the research question, study type, time, costs, data availability, and availability of respondents. The two main types of methods are qualitative research and quantitative research. Sometimes, researchers may find it difficult to decide which type of method is most suitable for their study. Keeping in mind a simple rule of thumb could help you make the correct decision. Quantitative research should be used to validate or test a theory or hypothesis and qualitative research should be used to understand a subject or event or identify reasons for observed patterns.

Qualitative research methods are based on principles of social sciences from several disciplines like psychology, sociology, and anthropology. In this method, researchers try to understand the feelings and motivation of their respondents, which would have prompted them to select or give a particular response to a question. Here are two qualitative research examples :

- Two brands (A & B) of the same medicine are available at a pharmacy. However, Brand A is more popular and has higher sales. In qualitative research , the interviewers would ideally visit a few stores in different areas and ask customers their reason for selecting either brand. Respondents may have different reasons that motivate them to select one brand over the other, such as brand loyalty, cost, feedback from friends, doctor’s suggestion, etc. Once the reasons are known, companies could then address challenges in that specific area to increase their product’s sales.

- A company organizes a focus group meeting with a random sample of its product’s consumers to understand their opinion on a new product being launched.

Table of Contents

What is qualitative research? 1

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data. The findings of qualitative research are expressed in words and help in understanding individuals’ subjective perceptions about an event, condition, or subject. This type of research is exploratory and is used to generate hypotheses or theories from data. Qualitative data are usually in the form of text, videos, photographs, and audio recordings. There are multiple qualitative research types , which will be discussed later.

Qualitative research methods 2

Researchers can choose from several qualitative research methods depending on the study type, research question, the researcher’s role, data to be collected, etc.

The following table lists the common qualitative research approaches with their purpose and examples, although there may be an overlap between some.

Types of qualitative research 3,4

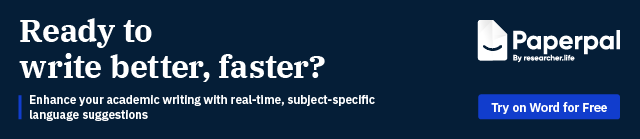

The data collection methods in qualitative research are designed to assess and understand the perceptions, motivations, and feelings of the respondents about the subject being studied. The different qualitative research types include the following:

- In-depth or one-on-one interviews : This is one of the most common qualitative research methods and helps the interviewers understand a respondent’s subjective opinion and experience pertaining to a specific topic or event. These interviews are usually conversational and encourage the respondents to express their opinions freely. Semi-structured interviews, which have open-ended questions (where the respondents can answer more than just “yes” or “no”), are commonly used. Such interviews can be either face-to-face or telephonic, and the duration can vary depending on the subject or the interviewer. Asking the right questions is essential in this method so that the interview can be led in the suitable direction. Face-to-face interviews also help interviewers observe the respondents’ body language, which could help in confirming whether the responses match.

- Document study/Literature review/Record keeping : Researchers’ review of already existing written materials such as archives, annual reports, research articles, guidelines, policy documents, etc.

- Focus groups : Usually include a small sample of about 6-10 people and a moderator, to understand the participants’ opinion on a given topic. Focus groups ensure constructive discussions to understand the why, what, and, how about the topic. These group meetings need not always be in-person. In recent times, online meetings are also encouraged, and online surveys could also be administered with the option to “write” subjective answers as well. However, this method is expensive and is mostly used for new products and ideas.

- Qualitative observation : In this method, researchers collect data using their five senses—sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing. This method doesn’t include any measurements but only the subjective observation. For example, “The dessert served at the bakery was creamy with sweet buttercream frosting”; this observation is based on the taste perception.

Qualitative research : Data collection and analysis

- Qualitative data collection is the process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research.

- The data collected are usually non-numeric and subjective and could be recorded in various methods, for instance, in case of one-to-one interviews, the responses may be recorded using handwritten notes, and audio and video recordings, depending on the interviewer and the setting or duration.

- Once the data are collected, they should be transcribed into meaningful or useful interpretations. An experienced researcher could take about 8-10 hours to transcribe an interview’s recordings. All such notes and recordings should be maintained properly for later reference.

- Some interviewers make use of “field notes.” These are not exactly the respondents’ answers but rather some observations the interviewer may have made while asking questions and may include non-verbal cues or any information about the setting or the environment. These notes are usually informal and help verify respondents’ answers.

2. Qualitative data analysis

- This process involves analyzing all the data obtained from the qualitative research methods in the form of text (notes), audio-video recordings, and pictures.

- Text analysis is a common form of qualitative data analysis in which researchers examine the social lives of the participants and analyze their words, actions, etc. in specific contexts. Social media platforms are now playing an important role in this method with researchers analyzing all information shared online.

There are usually five steps in the qualitative data analysis process: 5

- Prepare and organize the data

- Transcribe interviews

- Collect and document field notes and other material

- Review and explore the data

- Examine the data for patterns or important observations

- Develop a data coding system

- Create codes to categorize and connect the data

- Assign these codes to the data or responses

- Review the codes

- Identify recurring themes, opinions, patterns, etc.

- Present the findings

- Use the best possible method to present your observations

The following table 6 lists some common qualitative data analysis methods used by companies to make important decisions, with examples and when to use each. The methods may be similar and can overlap.

Characteristics of qualitative research methods 4

- Unstructured raw data : Qualitative research methods use unstructured, non-numerical data , which are analyzed to generate subjective conclusions about specific subjects, usually presented descriptively, instead of using statistical data.

- Site-specific data collection : In qualitative research methods , data are collected at specific areas where the respondents or researchers are either facing a challenge or have a need to explore. The process is conducted in a real-world setting and participants do not need to leave their original geographical setting to be able to participate.

- Researchers’ importance : Researchers play an instrumental role because, in qualitative research , communication with respondents is an essential part of data collection and analysis. In addition, researchers need to rely on their own observation and listening skills during an interaction and use and interpret that data appropriately.

- Multiple methods : Researchers collect data through various methods, as listed earlier, instead of relying on a single source. Although there may be some overlap between the qualitative research methods , each method has its own significance.

- Solving complex issues : These methods help in breaking down complex problems into more useful and interpretable inferences, which can be easily understood by everyone.

- Unbiased responses : Qualitative research methods rely on open communication where the participants are allowed to freely express their views. In such cases, the participants trust the interviewer, resulting in unbiased and truthful responses.

- Flexible : The qualitative research method can be changed at any stage of the research. The data analysis is not confined to being done at the end of the research but can be done in tandem with data collection. Consequently, based on preliminary analysis and new ideas, researchers have the liberty to change the method to suit their objective.

When to use qualitative research 4

The following points will give you an idea about when to use qualitative research .

- When the objective of a research study is to understand behaviors and patterns of respondents, then qualitative research is the most suitable method because it gives a clear insight into the reasons for the occurrence of an event.

- A few use cases for qualitative research methods include:

- New product development or idea generation

- Strengthening a product’s marketing strategy

- Conducting a SWOT analysis of product or services portfolios to help take important strategic decisions

- Understanding purchasing behavior of consumers

- Understanding reactions of target market to ad campaigns

- Understanding market demographics and conducting competitor analysis

- Understanding the effectiveness of a new treatment method in a particular section of society

A qualitative research method case study to understand when to use qualitative research 7

Context : A high school in the US underwent a turnaround or conservatorship process and consequently experienced a below average teacher retention rate. Researchers conducted qualitative research to understand teachers’ experiences and perceptions of how the turnaround may have influenced the teachers’ morale and how this, in turn, would have affected teachers’ retention.

Method : Purposive sampling was used to select eight teachers who were employed with the school before the conservatorship process and who were subsequently retained. One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with these teachers. The questions addressed teachers’ perspectives of morale and their views on the conservatorship process.

Results : The study generated six factors that may have been influencing teachers’ perspectives: powerlessness, excessive visitations, loss of confidence, ineffective instructional practices, stress and burnout, and ineffective professional development opportunities. Based on these factors, four recommendations were made to increase teacher retention by boosting their morale.

Advantages of qualitative research 1

- Reflects real-world settings , and therefore allows for ambiguities in data, as well as the flexibility to change the method based on new developments.

- Helps in understanding the feelings or beliefs of the respondents rather than relying only on quantitative data.

- Uses a descriptive and narrative style of presentation, which may be easier to understand for people from all backgrounds.

- Some topics involving sensitive or controversial content could be difficult to quantify and so qualitative research helps in analyzing such content.

- The availability of multiple data sources and research methods helps give a holistic picture.

- There’s more involvement of participants, which gives them an assurance that their opinion matters, possibly leading to unbiased responses.

Disadvantages of qualitative research 1

- Large-scale data sets cannot be included because of time and cost constraints.

- Ensuring validity and reliability may be a challenge because of the subjective nature of the data, so drawing definite conclusions could be difficult.

- Replication by other researchers may be difficult for the same contexts or situations.

- Generalization to a wider context or to other populations or settings is not possible.

- Data collection and analysis may be time consuming.

- Researcher’s interpretation may alter the results causing an unintended bias.

Differences between qualitative research and quantitative research 1

Frequently asked questions on qualitative research , q: how do i know if qualitative research is appropriate for my study .

A: Here’s a simple checklist you could use:

- Not much is known about the subject being studied.

- There is a need to understand or simplify a complex problem or situation.

- Participants’ experiences/beliefs/feelings are required for analysis.

- There’s no existing hypothesis to begin with, rather a theory would need to be created after analysis.

- You need to gather in-depth understanding of an event or subject, which may not need to be supported by numeric data.

Q: How do I ensure the reliability and validity of my qualitative research findings?

A: To ensure the validity of your qualitative research findings you should explicitly state your objective and describe clearly why you have interpreted the data in a particular way. Another method could be to connect your data in different ways or from different perspectives to see if you reach a similar, unbiased conclusion.

To ensure reliability, always create an audit trail of your qualitative research by describing your steps and reasons for every interpretation, so that if required, another researcher could trace your steps to corroborate your (or their own) findings. In addition, always look for patterns or consistencies in the data collected through different methods.

Q: Are there any sampling strategies or techniques for qualitative research ?

A: Yes, the following are few common sampling strategies used in qualitative research :

1. Convenience sampling

Selects participants who are most easily accessible to researchers due to geographical proximity, availability at a particular time, etc.

2. Purposive sampling

Participants are grouped according to predefined criteria based on a specific research question. Sample sizes are often determined based on theoretical saturation (when new data no longer provide additional insights).

3. Snowball sampling

Already selected participants use their social networks to refer the researcher to other potential participants.

4. Quota sampling

While designing the study, the researchers decide how many people with which characteristics to include as participants. The characteristics help in choosing people most likely to provide insights into the subject.

Q: What ethical standards need to be followed with qualitative research ?

A: The following ethical standards should be considered in qualitative research:

- Anonymity : The participants should never be identified in the study and researchers should ensure that no identifying information is mentioned even indirectly.

- Confidentiality : To protect participants’ confidentiality, ensure that all related documents, transcripts, notes are stored safely.

- Informed consent : Researchers should clearly communicate the objective of the study and how the participants’ responses will be used prior to engaging with the participants.

Q: How do I address bias in my qualitative research ?

A: You could use the following points to ensure an unbiased approach to your qualitative research :

- Check your interpretations of the findings with others’ interpretations to identify consistencies.

- If possible, you could ask your participants if your interpretations convey their beliefs to a significant extent.

- Data triangulation is a way of using multiple data sources to see if all methods consistently support your interpretations.

- Contemplate other possible explanations for your findings or interpretations and try ruling them out if possible.

- Conduct a peer review of your findings to identify any gaps that may not have been visible to you.

- Frame context-appropriate questions to ensure there is no researcher or participant bias.

We hope this article has given you answers to the question “ what is qualitative research ” and given you an in-depth understanding of the various aspects of qualitative research , including the definition, types, and approaches, when to use this method, and advantages and disadvantages, so that the next time you undertake a study you would know which type of research design to adopt.

References:

- McLeod, S. A. Qualitative vs. quantitative research. Simply Psychology [Accessed January 17, 2023]. www.simplypsychology.org/qualitative-quantitative.html

- Omniconvert website [Accessed January 18, 2023]. https://www.omniconvert.com/blog/qualitative-research-definition-methodology-limitation-examples/

- Busetto L., Wick W., Gumbinger C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological Research and Practice [Accessed January 19, 2023] https://neurolrespract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s42466-020-00059

- QuestionPro website. Qualitative research methods: Types & examples [Accessed January 16, 2023]. https://www.questionpro.com/blog/qualitative-research-methods/

- Campuslabs website. How to analyze qualitative data [Accessed January 18, 2023]. https://baselinesupport.campuslabs.com/hc/en-us/articles/204305675-How-to-analyze-qualitative-data

- Thematic website. Qualitative data analysis: Step-by-guide [Accessed January 20, 2023]. https://getthematic.com/insights/qualitative-data-analysis/

- Lane L. J., Jones D., Penny G. R. Qualitative case study of teachers’ morale in a turnaround school. Research in Higher Education Journal . https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1233111.pdf

- Meetingsnet website. 7 FAQs about qualitative research and CME [Accessed January 21, 2023]. https://www.meetingsnet.com/cme-design/7-faqs-about-qualitative-research-and-cme

- Qualitative research methods: A data collector’s field guide. Khoury College of Computer Sciences. Northeastern University. https://course.ccs.neu.edu/is4800sp12/resources/qualmethods.pdf

Researcher.Life is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Researcher.Life All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 21+ years of experience in academia, Researcher.Life All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $17 a month !

Related Posts

Academic Writing vs Non-Academic Writing

How to Define a Research Problem?

Qualitative Research Questions: Gain Powerful Insights + 25 Examples

We review the basics of qualitative research questions, including their key components, how to craft them effectively, & 25 example questions.

Einstein was many things—a physicist, a philosopher, and, undoubtedly, a mastermind. He also had an incredible way with words. His quote, "Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted," is particularly poignant when it comes to research.

Some inquiries call for a quantitative approach, for counting and measuring data in order to arrive at general conclusions. Other investigations, like qualitative research, rely on deep exploration and understanding of individual cases in order to develop a greater understanding of the whole. That’s what we’re going to focus on today.

Qualitative research questions focus on the "how" and "why" of things, rather than the "what". They ask about people's experiences and perceptions , and can be used to explore a wide range of topics.

The following article will discuss the basics of qualitative research questions, including their key components, and how to craft them effectively. You'll also find 25 examples of effective qualitative research questions you can use as inspiration for your own studies.

Let’s get started!

What are qualitative research questions, and when are they used?

When researchers set out to conduct a study on a certain topic, their research is chiefly directed by an overarching question . This question provides focus for the study and helps determine what kind of data will be collected.

By starting with a question, we gain parameters and objectives for our line of research. What are we studying? For what purpose? How will we know when we’ve achieved our goals?

Of course, some of these questions can be described as quantitative in nature. When a research question is quantitative, it usually seeks to measure or calculate something in a systematic way.

For example:

- How many people in our town use the library?

- What is the average income of families in our city?

- How much does the average person weigh?

Other research questions, however—and the ones we will be focusing on in this article—are qualitative in nature. Qualitative research questions are open-ended and seek to explore a given topic in-depth.

According to the Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry , “Qualitative research aims to address questions concerned with developing an understanding of the meaning and experience dimensions of humans’ lives and social worlds.”

This type of research can be used to gain a better understanding of people’s thoughts, feelings and experiences by “addressing questions beyond ‘what works’, towards ‘what works for whom when, how and why, and focusing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation,” states one paper in Neurological Research and Practice .

Qualitative questions often produce rich data that can help researchers develop hypotheses for further quantitative study.

- What are people’s thoughts on the new library?

- How does it feel to be a first-generation student at our school?

- How do people feel about the changes taking place in our town?

As stated by a paper in Human Reproduction , “...‘qualitative’ methods are used to answer questions about experience, meaning, and perspective, most often from the standpoint of the participant. These data are usually not amenable to counting or measuring.”

Both quantitative and qualitative questions have their uses; in fact, they often complement each other. A well-designed research study will include a mix of both types of questions in order to gain a fuller understanding of the topic at hand.

If you would like to recruit unlimited participants for qualitative research for free and only pay for the interview you conduct, try using Respondent today.

Crafting qualitative research questions for powerful insights

Now that we have a basic understanding of what qualitative research questions are and when they are used, let’s take a look at how you can begin crafting your own.

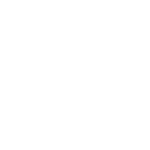

According to a study in the International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, there is a certain process researchers should follow when crafting their questions, which we’ll explore in more depth.

1. Beginning the process

Start with a point of interest or curiosity, and pose a draft question or ‘self-question’. What do you want to know about the topic at hand? What is your specific curiosity? You may find it helpful to begin by writing several questions.

For example, if you’re interested in understanding how your customer base feels about a recent change to your product, you might ask:

- What made you decide to try the new product?

- How do you feel about the change?

- What do you think of the new design/functionality?

- What benefits do you see in the change?

2. Create one overarching, guiding question

At this point, narrow down the draft questions into one specific question. “Sometimes, these broader research questions are not stated as questions, but rather as goals for the study.”

As an example of this, you might narrow down these three questions:

into the following question:

- What are our customers’ thoughts on the recent change to our product?

3. Theoretical framing

As you read the relevant literature and apply theory to your research, the question should be altered to achieve better outcomes. Experts agree that pursuing a qualitative line of inquiry should open up the possibility for questioning your original theories and altering the conceptual framework with which the research began.

If we continue with the current example, it’s possible you may uncover new data that informs your research and changes your question. For instance, you may discover that customers’ feelings about the change are not just a reaction to the change itself, but also to how it was implemented. In this case, your question would need to reflect this new information:

- How did customers react to the process of the change, as well as the change itself?

4. Ethical considerations

A study in the International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education stresses that ethics are “a central issue when a researcher proposes to study the lives of others, especially marginalized populations.” Consider how your question or inquiry will affect the people it relates to—their lives and their safety. Shape your question to avoid physical, emotional, or mental upset for the focus group.

In analyzing your question from this perspective, if you feel that it may cause harm, you should consider changing the question or ending your research project. Perhaps you’ve discovered that your question encourages harmful or invasive questioning, in which case you should reformulate it.

5. Writing the question

The actual process of writing the question comes only after considering the above points. The purpose of crafting your research questions is to delve into what your study is specifically about” Remember that qualitative research questions are not trying to find the cause of an effect, but rather to explore the effect itself.

Your questions should be clear, concise, and understandable to those outside of your field. In addition, they should generate rich data. The questions you choose will also depend on the type of research you are conducting:

- If you’re doing a phenomenological study, your questions might be open-ended, in order to allow participants to share their experiences in their own words.

- If you’re doing a grounded-theory study, your questions might be focused on generating a list of categories or themes.

- If you’re doing ethnography, your questions might be about understanding the culture you’re studying.

Whenyou have well-written questions, it is much easier to develop your research design and collect data that accurately reflects your inquiry.

In writing your questions, it may help you to refer to this simple flowchart process for constructing questions:

Download Free E-Book

25 examples of expertly crafted qualitative research questions

It's easy enough to cover the theory of writing a qualitative research question, but sometimes it's best if you can see the process in practice. In this section, we'll list 25 examples of B2B and B2C-related qualitative questions.

Let's begin with five questions. We'll show you the question, explain why it's considered qualitative, and then give you an example of how it can be used in research.

1. What is the customer's perception of our company's brand?

Qualitative research questions are often open-ended and invite respondents to share their thoughts and feelings on a subject. This question is qualitative because it seeks customer feedback on the company's brand.

This question can be used in research to understand how customers feel about the company's branding, what they like and don't like about it, and whether they would recommend it to others.

2. Why do customers buy our product?

This question is also qualitative because it seeks to understand the customer's motivations for purchasing a product. It can be used in research to identify the reasons customers buy a certain product, what needs or desires the product fulfills for them, and how they feel about the purchase after using the product.

3. How do our customers interact with our products?

Again, this question is qualitative because it seeks to understand customer behavior. In this case, it can be used in research to see how customers use the product, how they interact with it, and what emotions or thoughts the product evokes in them.

4. What are our customers' biggest frustrations with our products?

By seeking to understand customer frustrations, this question is qualitative and can provide valuable insights. It can be used in research to help identify areas in which the company needs to make improvements with its products.

5. How do our customers feel about our customer service?

Rather than asking why customers like or dislike something, this question asks how they feel. This qualitative question can provide insights into customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction with a company.

This type of question can be used in research to understand what customers think of the company's customer service and whether they feel it meets their needs.

20 more examples to refer to when writing your question

Now that you’re aware of what makes certain questions qualitative, let's move into 20 more examples of qualitative research questions:

- How do your customers react when updates are made to your app interface?

- How do customers feel when they complete their purchase through your ecommerce site?

- What are your customers' main frustrations with your service?

- How do people feel about the quality of your products compared to those of your competitors?

- What motivates customers to refer their friends and family members to your product or service?

- What are the main benefits your customers receive from using your product or service?

- How do people feel when they finish a purchase on your website?

- What are the main motivations behind customer loyalty to your brand?

- How does your app make people feel emotionally?

- For younger generations using your app, how does it make them feel about themselves?

- What reputation do people associate with your brand?

- How inclusive do people find your app?

- In what ways are your customers' experiences unique to them?

- What are the main areas of improvement your customers would like to see in your product or service?

- How do people feel about their interactions with your tech team?

- What are the top five reasons people use your online marketplace?

- How does using your app make people feel in terms of connectedness?

- What emotions do people experience when they're using your product or service?

- Aside from the features of your product, what else about it attracts customers?

- How does your company culture make people feel?

As you can see, these kinds of questions are completely open-ended. In a way, they allow the research and discoveries made along the way to direct the research. The questions are merely a starting point from which to explore.

This video offers tips on how to write good qualitative research questions, produced by Qualitative Research Expert, Kimberly Baker.

Wrap-up: crafting your own qualitative research questions.

Over the course of this article, we've explored what qualitative research questions are, why they matter, and how they should be written. Hopefully you now have a clear understanding of how to craft your own.

Remember, qualitative research questions should always be designed to explore a certain experience or phenomena in-depth, in order to generate powerful insights. As you write your questions, be sure to keep the following in mind:

- Are you being inclusive of all relevant perspectives?

- Are your questions specific enough to generate clear answers?

- Will your questions allow for an in-depth exploration of the topic at hand?

- Do the questions reflect your research goals and objectives?

If you can answer "yes" to all of the questions above, and you've followed the tips for writing qualitative research questions we shared in this article, then you're well on your way to crafting powerful queries that will yield valuable insights.

Download Free E-Book

.png?width=2500&name=Respondent_100+Questions_Banners_1200x644%20(1).png)

Asking the right questions in the right way is the key to research success. That’s true for not just the discussion guide but for every step of a research project. Following are 100+ questions that will take you from defining your research objective through screening and participant discussions.

Fill out the form below to access free e-book!

Recommend Resources:

- How to Recruit Participants for Qualitative Research

- The Best UX Research Tools of 2022

- 10 Smart Tips for Conducting Better User Interviews

- 50 Powerful Questions You Should Ask In Your Next User Interview

- How To Find Participants For User Research: 13 Ways To Make It Happen

- UX Diary Study: 5 Essential Tips For Conducing Better Studies

- User Testing Recruitment: 10 Smart Tips To Find Participants Fast

- Qualitative Research Questions: Gain Powerful Insights + 25

- How To Successfully Recruit Participants for A Study (2022 Edition)

- How To Properly Recruit Focus Group Participants (2022 Edition)

- The Best Unmoderated Usability Testing Tools of 2022

50 Powerful User Interview Questions You Should Consider Asking

We researched the best user interview questions you can use for your qualitative research studies. Use these 50 sample questions for your next...

How To Unleash Your Extra Income Potential With Respondent

The number one question we get from new participants is “how can I get invited to participate in more projects.” In this article, we’ll discuss a few...

Understanding Why High-Quality Research Needs High-Quality Participants

Why are high-quality participants essential to your research? Read here to find out who they are, why you need them, and how to find them.

- Open access

- Published: 03 January 2020

Students’ problem-solving strategies in qualitative physics questions in a simulation-based formative assessment

- Mihwa Park ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9549-9515 1

Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research volume 2 , Article number: 1 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

9556 Accesses

1 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Previous studies on quantitative physics problem solving have been concerned with students’ using equations simply as a numerical computational tool. The current study started from a research question: “How do students solve conceptual physics questions in simulation-based formative assessments?” In the study, three first-year college students’ interview data were analyzed to characterize their problem-solving strategies in qualitative physics questions. Prior to the interview, the participating students completed four formative assessment tasks in physics integrating computer simulations and questions. The formative assessment questions were either constructed-response or two-tiered questions related to the simulations. When interviewing students, they were given two or three questions from each task and asked to think aloud about the questions. The findings showed that students still used equations to answer the qualitative questions, but the ways of using equations differed between students. The study found that when students were able to connect variables to a physical process and to interpret relationships among variables in an equation, equations were used as explanatory or conceptual understanding tools, not just as computational tools.

Introduction

Since the new U.S. science standards, Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), were released (NGSS Lead States, 2013 ), science assessments have been moving towards revealing students’ reasoning and their ability to apply core scientific ideas in solving problems (National Research Council, 2014 ; Pellegrino, 2013 ). Underwood, Posey, Herrington, Carmel, and Cooper ( 2018 ) suggested types of questions aligned with three-dimensional learning in A Framework for K-12 Science Education (National Research Council, 2012 ). These questions include constructed-response (CR) questions and two-tiered questions. Underwood et al. ( 2018 ) also argued that questions should address core and cross-cutting ideas and ask students to consider how scientific phenomena occur so that they can construct explanations and engage in argumentation. The underlying assumption of this approach could be that qualitative explanation questions (i.e., questions that ask students to explain qualitatively) reveal students’ reasoning and understanding of core scientific concepts better than do traditional multiple-choice and simple-calculation questions. Numerous studies in physics education have examined students’ problem-solving strategies, including studies that have identified differences in the problem-solving strategies employed by experts and novices. Experts tend to start by using general scientific principles to analyze problems conceptually, while novices tend to start by selecting equations and plugging in numbers (Larkin, McDermott, Simon, & Simon, 1980 ; Maloney, 1994 ; Simon & Simon, 1978 ). Thus, giving students opportunities to reason qualitatively about problems could help them to think like experts (van Heuvelen, 1991 ).

Another way to enhance students’ conceptual understanding of scientific ideas could be using computer simulations, because computer simulations help students visualize scientific phenomena that cannot be easily and accurately observed in real life. Many empirical studies support integrating computer simulations into assessments in order to promote students’ engagement in exploring scientific phenomena (de Jong & van Joolingen, 1998 ) and their conceptual understanding (Rutten, van Joolingen, & van der Veen, 2012 ; Trundle & Bell, 2010 ). For example, Quellmalz, Timms, Silberglitt, and Buckley ( 2012 ) developed a simulation-based science assessment, and found that the assessment was effective to reveal students’ knowledge and to find evidence of students’ reasoning. In the current study, computer simulations and conceptual qualitative questions were incorporated as integral parts of formative assessment to reveal students’ problem-solving strategies in answering qualitative physics questions. Therefore, the current study investigated students’ problem-solving strategies in physics, which offered them opportunities to elicit their reasoning by qualitatively explaining what would happen and why it would happen about a given physical situation.

Students’ strategies to solving physics problems

Early research on physics problem solving identified differences between experts and novices in their problem-solving strategies. For example, experts’ knowledge is organized into structures; thus, they demonstrate the effective use of sophisticated strategies to solve problems (Gick, 1986 ). Conversely, novices tend to describe physics problems at best in terms of equations, and spontaneously use superficial analogies (Gick, 1986 ). Experts also effectively use the problem decomposition strategy: breaking down a problem into subproblems, then solving each subproblem and combining them to form the final solution (Dhillon, 1998 ). They also apply relevant principle and laws to solve problems (Chi, Feltovich, & Glaser, 1981 ; Dhillon, 1998 ). By contrast, novices start with selecting equations and cue into surface features (Chi et al., 1981 ). A common finding from studies on differences between experts and novices in problem solving (e.g., Chi et al., 1981 ; Dhillon, 1998 ; Gick, 1986 ; Larkin et al., 1980 ) is that experts demonstrate their expertise in conceptual analysis of the problems using scientific principles and laws, then translate the problem into relevant mathematical equations, while novices jump to mathematical manipulations without the prior process of conceptual analysis (Larkin et al., 1980 ).

Huffman ( 1997 ) incorporated the results of studies on the differences in problem solving between experts and novices to formulate explicit problem-solving procedures for students. The procedures include five steps: (a) performing a qualitative analysis of the problem situation; (b) translating the conceptual analysis into a simplified physics description; (c) translating the physics description into specific mathematical equations to plan the solution; (d) combining the equations according to the plan; and (e) evaluating the solution to ensure it is reasonable and complete (Huffman, 1997 ). In essence, the procedure is designed to ensure students will conceptually reason about the problem first, using relevant scientific principles and laws, before jumping to selecting mathematical equations.

It is possible that students’ problem-solving strategies are influenced by problem representations (verbal, mathematical, graphical, etc.). Kohl and Finkelstein ( 2006 ) investigated how problem representations and student performance were related, and found that student strategies to solve physics problems often varied with different representations. They also found that not only problem representations but a number of other things, including prior knowledge and experience in solving problems from their previous classes, also influenced students’ performance, especially in the case of low-performing students. When asking students not to calculate a science question but to explain it conceptually, a study found that they still used equations or numerical values to solve the problems, indicating that they translated a conceptual qualitative question into a quantitative one (De Cock, 2012 ). Although students may succeed in calculating values in physics problems, it doesn’t always mean that they have good conceptual understanding of the questions (McDermott, 1991 ).

While earlier studies have been concerned with students’ using equations without conceptual understanding when solving problems, mathematical modeling plays a critical role in the epistemology in physics (Redish, 2017 ). Redish emphasized the importance of connecting physical meaning to mathematical representation when solving problems, because in physics, mathematical equations are linked to physical systems, and an equation contains packed conceptual knowledge. Thus, in physics, equations are not only computational tools but also symbolic representations of logical reasoning (Redish, 2005 , 2017 ). As such, students are expected to incorporate mathematical equations into their intuition of the physical world to conceptualize the physical system (Redish & Smith, 2008 ). In a study of students’ quantitative problem solving, Kuo, Hull, Gupta, and Elby ( 2012 ) pointed out the importance of connecting mathematical symbols to conceptual reasoning. Their study was conducted based on an assumption that equations should be blended with conceptual meaning in physics, which turned the attention of researchers on problem solving from how students select equations to how they use the equations. Kuo et al. ( 2012 ) concluded that blending of mathematical operations with conceptual reasoning constitutes good problem solving; thus, this blended process should be a part of problem-solving expertise in physics.

Using computer simulations as an assessment tool

Given that visualization plays a central role in the conceptualization process of physics (Kozhevnikov, Motes, & Hegarty, 2007 ), previous studies have used computer simulations to visualize scientific phenomena, especially those that cannot be accurately observed in real life, and reported their positive effect on students’ learning outcomes (Ardac & Akaygun, 2004 ; Dori & Hameiri, 2003 ). Using computer simulation to facilitate student learning in science was found to be especially effective on student performance, motivation (Rutten et al., 2012 ), and conceptual change (Smetana & Bell, 2012 ).

Computer simulation can be used not only as an instructional tool but also as an assessment tool. For example, Park, Liu, and Waight ( 2017 ) developed computer simulations for U.S. high school chemistry classes to help students conceptualize scientific phenomena, and then integrated the simulations into formative assessments with questions related to the simulations. Quellmalz et al. ( 2012 ) and Srisawasdi and Panjaburee ( 2015 ) also embedded computer simulations into formative assessments for use in science classrooms, and demonstrated positive effects on students’ performance compared to students who experienced only traditional assessments (e.g., paper-and-pencil tests). While many empirical studies have been done to investigate problem-solving strategies of students, there is a lack in studies on students’ strategies to solve physics problems when computer simulations were used as a visual representation and conceptual explanation questions were asked to reveal the students’ reasoning. This study addresses the gap in the body of literature by investigating students’ strategies in solving conceptual explanation questions in a simulation-based formative assessment.

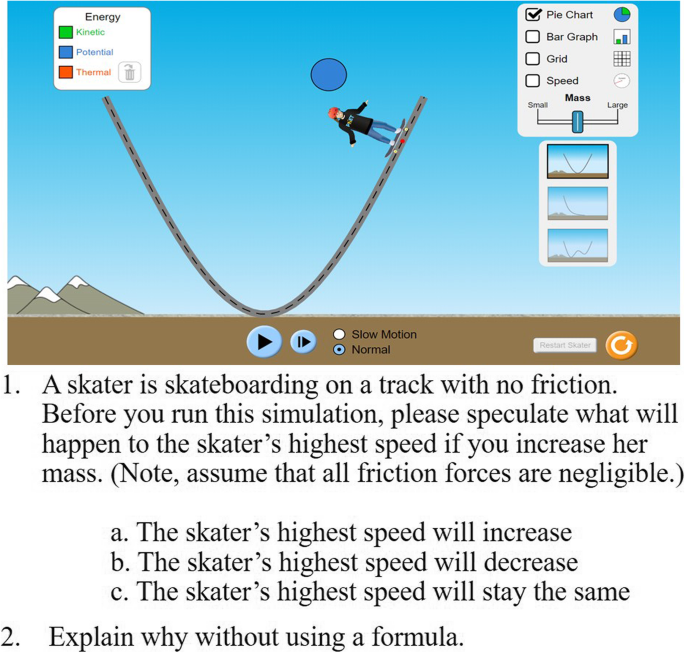

Research procedure and participants

In the study, computer simulations and formative assessment questions were integrated into a web-based formative assessment system for online administration, which allowed students to use it at their convenience (Park, 2019 ). The formative assessment questions were either CR or two-tiered questions related to the simulations. A two-tiered question consists of a simple multiple-choice (MC) question and a justification question for which students write a justification for their answer to the MC question. This format of question was suggested to diagnose possible misconceptions held by students (Treagust, 1985 ) and to provide information about students’ reasoning behind their selected responses (Gurel, Eryılmaz, & McDermott, 2015 ). Computer simulations were selected from the Physics Education Technology (PhET) project ( https://phet.colorado.edu/ ) and embedded into the formative assessment system. The assessments targeted students’ conceptual understanding in physics, thus they were not asked to calculate any values or to demonstrate their mathematical competence (Park, 2019 ). Specifically, the questions presented a scientific situation and asked students to predict what would happen; then the assessment system asked students to run a simulation, posing questions asking for explanation of the phenomena and comparison between their prior ideas and the observed phenomena. Figure 1 presents example questions and simulation for the energy conservation task. After answering the questions, students ran the simulation and responded to questions asking how the skater’s highest speed changed and why they think it happened using evidence found in the simulation.

Energy conservation task example questions

Initially, first-year college students were recruited from a calculus-based, introductory level physics course at a large, public university in the United States; no particular demographic was targeted during recruitment. The physics course was offered to students majoring in subjects related to science or engineering and covered mechanics, including kinematics and conservation of energy, so simulations were selected to align with the course content. After selecting simulations from the PhET project, related formative assessment questions were created. As previously mentioned, the questions first asked students to predict what would happen in a given situation. In this case, verbal (expressed in writing) and pictorial representations (including images, diagrams, or graphs) describing the situation were shown on the screen (Fig. 1 ). Next, after the students answered the questions, the simulations were enabled for the students to run, and they were asked to explain the results. In total, four formative assessment tasks were developed and implemented online, and each task contained from 14 to 17 questions. Topics for the four tasks were (1) motion in two dimensions, (2) the laws of motion, (3) motion in one dimension and friction, and (4) conservation of energy. Descriptions of the four tasks are presented below.

Task 1: Students explore what factors will affect an object’s projectile motion when firing a cannon.

Task 2: Students create an applied force such as pulling against or pushing an object and observe how it makes the object move.

Task 3: Students explore the forces at work when a person tries to push a filing cabinet on a frictionless or frictional surface.

Task 4: Students explore a skater’s motion on different shapes of tracks and explore the relationship between the kinetic energy and thermal energy of the skater.

After the participating students completed the online implementations of the four tasks, an interview invitation email was sent to the students who had completed all four tasks, did not skip any questions, and did not answer a question with an off-task response, but included responses that needed further clarification. Initially, we invited six students to clarify and elaborate on their responses so we could better understand what they were thinking. When scoring students’ written responses, some responses needed further clarification. For example, students mentioned that in projectile motion, “mass is not relative to time”; “the greater angle will create a larger x component of velocity in a projectile motion”; or “an object’s speed is broken up evenly resulting in more air time”. In case of the energy conservation task, the responses needing more clarification were “the speed did not change because speed does not depend on mass” or “because a skater’s total energy increases with increase in mass, her speed does not change”. Those responses were not clear to the author. Thus, the author decided to invite them to clarify their responses. During the interviews, the students’ verbal responses inspired the author to explore differences in their problem-solving strategies to answer conceptual physics questions. Three students especially, Alex, Christopher, and Blake (all pseudonyms), demonstrated noticeable differences in their problem-solving strategies; therefore, they are the focus of the analysis in the current study.

Interview context and protocols

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to investigate students’ reasoning when responding to conceptual physics questions. To this end, the students were given two or three questions from each task and asked to think aloud about the questions. After they verbally answered each question, they were given their original written responses to see if their answers had changed, and if so, to explain why. When students used mathematical equations or graphs in their explanations, they were asked to explain why they used those particular strategies and how the strategies helped them to answer the questions. Some example interview questions were; “Please read the question. Will you tell me your answer for the question?”, “How did you answer this question?”, “Could you clarify what this means?”, and “What did you mean by (specific terms that students used)?” Students were interviewed individually by two interviewers. The interviews, which took place in an interview room located at their university, each lasted an hour.

While the interviews were going on, the author wrote memos about the students’ strategies to answer the given questions and their misconceptions about science. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were initially analyzed to prepare and organize data into emergent themes. In this process, the memos were also used. As a result, three initial themes were developed: 1) students’ strategies to answer problems, 2) effects of the assessment on students’ learning, and 3) students’ misconceptions about science. In the study, the first theme—strategies to answer problems—was made a focus in the next level of analysis, as the students demonstrated noticeable differences in using equations to answer conceptual physics problems. After choosing the theme as a main focus, the author analyzed it by open coding the relevant parts of the transcripts of the individual student interviews (interviews about Tasks 1–3) to formulate possible characterizations of students’ problem-solving strategies, especially when they were using equations. The author constantly compared the characterizations to integrate and refine them (Strauss & Corbin, 1998 ). After that, the rest of each individual student interview transcript (interviews about Task 4) was analyzed, using the same categories to confirm the findings. Students’ drawings (i.e., graphs) used to explain their reasoning were also considered as a data source (Creswell, 2016 ). Once characterizations in students’ use of equations in qualitative physics question were identified and compared across cases, the analysis results were given to a physics education researcher to seek an external check (Creswell & Miller, 2000 ).

Previous studies on expert and novice problem-solving strategies were reflected in the design of the formative assessment questions. Specifically, it was hypothesized that conceptual explanation questions would help students think about the questions more conceptually, so that they would start to solve them using scientific concepts and laws. Therefore, short written questions in the tasks asked the students to explain or to justify their answers without using a formula. Nonetheless, when we were interviewing students, we found that they preferred to use equations and mathematical concepts when explaining physical situations. Although the three participating students commonly used equations or mathematical concepts in their explanations, how they used the equations or mathematical concepts differed. Detailed findings are presented below in three subsections representing patterns in problem-solving strategies. Formative assessment Tasks 1, 2, and 3 were designed to address the topic of Motion and Force, while Task 4 covered the topic of Energy Conservation. We analyzed interview data by these two topics. Note that two terms—formula and equation—were not differentiated in the analysis of data; instead, they were considered synonyms.

Alex’s case – using equations as a conceptual understanding tool

Motion and force.

When interviewing Alex, we asked him what would happen if a person pushed a box, then let it go (Task 2). He said, “If it is frictionless, the box will move forever with a constant velocity, and if friction exists, the speed will decrease and eventually the box will stop.” This answer was very similar to his original written response. Next, we asked what would happen to the box’s motion after another box was placed on top of it. Alex said, “I don’t know how to explain this without a formula.” Because the original questions had asked students not to use formulas, he assumed that he was not allowed to use one in this explanation, and obviously he was struggling to explain without it. We told him to use formulas whenever he wanted, and he quickly jumped into using one.

Alex: Resultant force equals mass times acceleration, so if you have a bigger mass. Uh, if the resultant force was 50N, that’s the force you applied, and then you had 10N in friction, for example, then the resultant force is 40. You had, if you had 20kg, the acceleration would be 2. If you had 50kg, the acceleration would be 4 over 5, which is 0.8, which is less than 2. So, the more mass you have the smaller the acceleration is going to be, as a result of the resultant force equals ma equation.

In this statement, Alex explained what would happen in the given situation with algebraic solutions, using F = ma equation, and concluded that mass would affect the object’s acceleration, as he demonstrated. He further described how the eq. ( F = ma ) helped him to explain the given physical situation.

Alex: If you use the formula, then it makes it much easier, because in real life, you never see something moving without friction, so it just clouds your judgment a bit.

In this statement, Alex described the role of equation for him as a conceptual understanding tool, especially in an ideal situation that is not observable in real life. This was something the author had not initially expected from the students during their interviews. When we asked Alex the next question in Task 3, his answer further supported the finding that equations helped him understand physical situations. Specifically, we asked, in a situation when a person was pushing a cabinet on either a frictionless or a frictional surface, what would happen to the cabinet’s motion and why.

Alex: The normal force is, the gravitational force cancels out the y , so the only thing acting on the—in the x -direction, which is the direction being pushed is the applied force, so as small of a force you apply to it, it’s still going to move it because there’s nothing opposing it…if there was friction, I agree that it won’t move. Because the friction, the friction is the coefficient of friction times the normal force, so, since it’s a really big object, it’s going to have a significant amount of friction acting on it.

In his verbal explanation, Alex used a mathematical concept and an equation to explain the given phenomenon, using the vector concept for two components of force and a mathematical equation for frictional force. Obviously, he found equations useful to make sense of physical situations and to explain his understanding to others. Notably, he started his answer by referring to the formula for kinetic friction force and used the formula as a tool to explain why the cabinet wouldn’t move on a frictional surface. His explanation again demonstrated that equations and mathematical concepts were useful to understanding and interpreting scientific phenomena, and not only as a simple computational tool, at least for Alex.

Conservation of energy

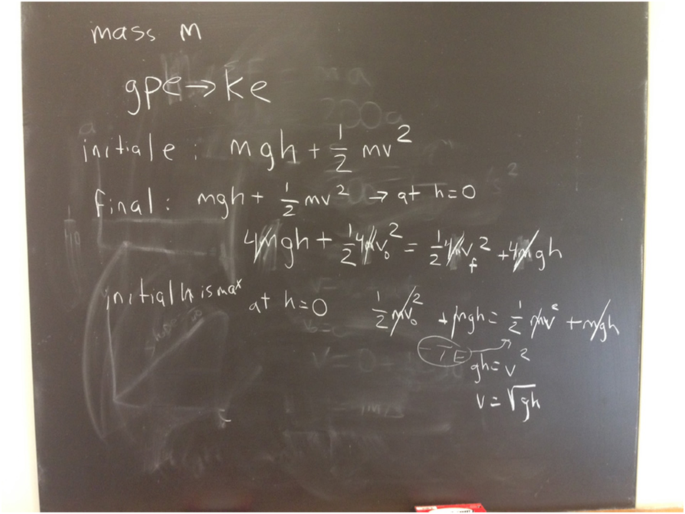

Task 4 was designed to investigate students’ conceptions of mechanical energy and its conservation. We asked Alex, when a skater is skateboarding on a track with no friction, what would happen to the skater’s highest speed as the skater’s mass increases? He again asked us if he could use equations. We confirmed that he was allowed to use equations anytime he wanted. Then he immediately started writing equations on the board (see Fig. 2 ). While he was writing, he explained each variable involved in the equations:

Alex: So, her initial, so, um, at the start, her initial energy is mgh + ½ mv 0 2 and then her final [writing on board] mgh + ½ mv f 2 , but the smaller thing to do is that they [mass] all cancel out, so the mass is really, it doesn’t play a role in the height or the velocity. And then, if you wanted to see how the conversion of energy works, if you were initially starting at the maximum height, whatever that is, you could do ½ mv 2 . At the start, her velocity is 0, at the top, so this cancels out, if we’re analyzing it at the bottom, which is her max speed, then this [ h ] is 0, and then you just do gh = v 2 . To find her velocity. Just looking at this, there’s no mass in this, so it doesn’t matter [the skater’s speed]. When you actually work it out, all the masses cancel out, so it doesn’t matter what the mass is, in reality, when you actually calculate it.

This response was different than his original written response to the same question: “If the skater has a larger mass, she will in turn have a larger gravitational potential energy since GPE [gravitational potential energy] has a direct relationship to mass. As a result and according to the principles of conservation of energy, the KE [kinetic energy] will be greater and thus the velocity will be greater.” In this original written response, Alex included a typical misconception that heavier objects fall faster (e.g., Gunstone, Champagne, & Klopfer, 1981 ; Lazonder & Ehrenhard, 2014 ); “If the skater has a larger mass…thus the velocity will be greater” (in his written response). This was the only case of a misconception found in Alex’s written responses. Notably, when he was using equations, he deduced that “it doesn’t matter what the mass is, in reality, when you actually calculate it” from his step-by-step problem-solving procedure using algebraic solutions. Although he solved the problem using equations through algebraic computation, he explained how the object’s velocity and height would change as the object moved: “At the start, her velocity is 0, at the top, so this cancels out, if we’re analyzing it at the bottom, which is her max speed, then this [ h ] is 0, and then you just do gh = v 2 .” Then he connected conceptual meaning to the equation: “Just looking at this, there’s no mass in this, so it doesn’t matter [the skater’s speed].” This confirmed that for Alex, equations were the first tool to make sense of physical situation. In other words, when he applied an equation to a physical situation, he considered variables related to specific situations, then connected conceptual meaning to the variables, which indicated that for him, equations played a role in analyzing and understanding physical situation.

Alex’s explanation

Christopher’s case – using equations as an explanatory tool

We asked Christopher a question—which tank shell would go farther when the initial angles for two tank shells were different (Task 1). In his original written response, he mentioned that “tank A (initial angle: 45 degree)’s speed is broken up more evenly and this results in more air time which leads to more distance covered in the x axis as well.” This answer was similar to Christopher’s thinking-aloud response, so we asked him to elaborate on what he meant by “speed is broken up more evenly.” Below is his response.

Christopher: Because the velocity is a vector quantity, the speed is still the same, but the velocity, the x and y axis are going to be more evenly split [for Tank A, with a 45-degree initial angle], whereas for Tank B [10-degree initial angle] it would have been almost all in the x axis and close to none in the y , so it wouldn’t get that much air time because the force of gravity still stays the same.

As seen in his response, Christopher deduced his answer from a mathematical concept (vector in this case) explaining why the 45-degree shell would have a greater horizontal range than the 10-degree shell one. His problem-solving strategy in the next questions (questions from Tasks 2 and 3) further confirmed that he used mathematical concepts and equations to explain physical situations. For example, when asked to compare two situations from Task 2—a person pushes a box and lets it go, and after placing another box on top of that, a person pushes both boxes and lets them go—Christopher immediately used F = ma and explained the situation.

Christopher: The velocity and the speed will be decreased because, when applying force, force is mass times acceleration. So, if it would be the same exact force with a higher mass, then the acceleration would have to go down significantly in order to keep the same number [force]. So, because of this, it wouldn’t speed up as much, so it would have a lower velocity after the force was applied [compared to the previous situation]. While you are pushing, the acceleration is constant. And if they let it go, there is no acceleration. Then speed will stay the same.

In his statement, he referred to F = ma , and explained why the box’s acceleration would be smaller when its mass increased using algebraic solutions, which is similar to Alex’s case. The difference is that Christopher’s explanation contained an interpretation of the relationship among velocity, acceleration, and applied force: “So, because of this, it wouldn’t speed up as much, so it would have a lower velocity after the force was applied.” This implies that Christopher did not just use the equation as a computational tool, but linked meanings to variables (force, velocity, mass, and acceleration) and interpreted a relationship among them. When we asked him a question from Task 3—when a person is pushing a cabinet, how will the cabinet’s velocity change after passing over the frictionless surface and traveling onto the surface with friction?—his answer reconfirmed that he considered the relationship among variables and gave conceptual meaning not only to the variables but also to the relationship, and used a mathematical concept as an important tool to interpret a physical situation.

Christopher: So, the velocity is 100% dependent on the acceleration, which depends on the force, and then in this scenario, it is the force at first, it has a much higher total net force in the x direction, whereas later on it decreases [on a frictional surface], but there’s still a positive net force in the x direction, so it will continue. The reason why it continues to speed up is because the acceleration is still positive. ‘Cause mass can’t really be negative so that [acceleration] is the only variable [to determine the change of velocity]. So, that’s why velocity continues to increase, it’s just not as much as before.

In his statement, Christopher did not interpret an individual variable separately; rather, he first considered the relationship between force, velocity, and acceleration using the concept of vector and scalar quantity (e.g., mass is not a vector quantity), and explained how each variable was influenced by the other variables’ changes. From the statements above, it is clear that Christopher reasoned through a physical process by interpreting relationships among variables and attaching conceptual meaning to the relationship and the variables.

When we asked Christopher about change in the skater’s highest speed when the skater’s mass increased, his original written and oral responses contained the common answer that the skater’s highest speed would stay the same because gravity acts on all objects equally: “the downward acceleration will be the same.” We further asked him about how total mechanical energy changes. His response is below.

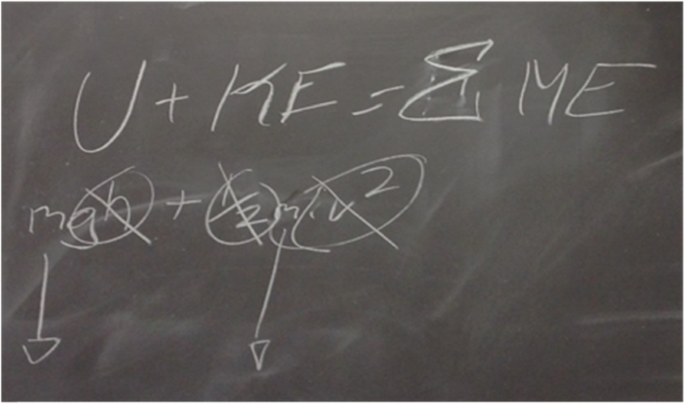

Christopher: Her [the skater’s] mechanical energy would increase because the velocity would stay the same for kinetic, but the mass would go up, so it would make the answer higher. And it’s probably easier to think of it with GPE, can I use the formula to it?

Then he drew a formula on board (Fig. 3 ), and explained why the total mechanical energy would change.

Christopher: This is mg. Since these two [ gh, ½ ] stay the same for both cases, they can be canceled out. So then, these are the only variables in ME (mechanical energy), so if this [ m ] increases, then the whole system[’s energy] will increase, but it won’t change this [ v ] in the specific scenario. If you were to use the equations, once you were to set them equal to each other and solve for the final answer for each, they would still be the same, even though the mass is higher. But because it’s multiplied, you can cancel it [ m ] on both sides for that specific scenario, so it mainly just depends on the constant ½ and then the variable of height and the final velocity which would be the same for this case.

In his response, Christopher first explained the physical situation using the concept of energy and considered the situation as a system: “Her [the skater’s] mechanical energy would increase,” and “so if this [ m ] increases, then the whole system[‘s energy] will increase.” In order to prove why mass doesn’t affect the skater’s speed, he used an equation as an explanatory tool—“And it’s probably easier to think of it with GPE, can I use the formula to it?”—and showed that mass doesn’t affect the skater’s speed: “You can cancel it [ m ] on both sides for that specific scenario.” A noticeable difference from Alex’s approach is that Christopher used equations to prove his claim and to explain it in an easier way, while Alex used equations to make sense of the situation. In other words, equations were in play mainly as explanatory tools for Christopher, whereas they acted as conceptual understanding tools for Alex. Similarly to his previous responses to questions in Motion and Force, Christopher again demonstrated that he considered how all variables were related each other in the system, and attached meaning to the relationship and variables. Interestingly, he often used the phrase “specific scenario,” so we asked what it meant. Below is his response.

Christopher: The equations don’t really help because even though I see it and it’s in my head, but it’s not really useful if I don’t know the scenario. If it’s some problems, I know, are purposefully shaped to muddle it up, and make it purposefully confusing, but usually, when you run the scenario, in a program or in your head, it kind of takes out that confusing stuff.

The above response illustrated that Christopher conceptually interpreted the physical situation first, then translated equations into the physical situation. This strategy shared a commonality with Alex’s in that both students used equations in their explanations and connected how variables in the equations changed as the specific physical situation changed. At the same time, there was a difference between the two students. Christopher’s strategy started with an analysis of the situation, creating a physical scenario and then translating equations into the physical situation, while Alex mentioned relevant equations first, then connected them to the physical situation.

Christopher’s explanation. Note: ME = mechanical energy

Blake’s case – using equations as a computational tool

When we asked Blake which one would go farther when shot from a cannon, a tank shell or a baseball (when air resistance was negligible; Task 1), her original written response and her thinking-aloud response were similar: the mass of an object is not relative to its motion. When we asked her to explain why, she said:

Blake: Because I don’t see kg on the units at all [in the simulation]. kg is the unit for mass, kilograms, so, it’s not written as kg/m/s or something. You could easily compare it with units and mass is not part of the unit.

Her response was interesting in that she used the unit of velocity rather than acceleration. Also, she did not show her conceptual understanding of physical variables and their relationship as Christopher had done. We further asked her what factors should be changed to maximize the horizontal range of the projectile object, in order to elicit her reasoning about a projectile motion. Below is her response.

Blake: You need to throw it faster. Um, because, if you look at gun for example. It’s a really high velocity. So, you just see it going like straight because it’s just high velocity. And, um, if, if I’m throwing this phone, maximum distance it could go is like here [tosses phone, not very far]. Angle? I think…like the maximum distance for x axis and y axis is 45 degrees, but I think it should be a little lower. Around 45 but plus or minus 5 degrees, so like 40 degrees.

Interviewer: Why would you say that?

Blake: It doesn’t get that much time for vertical velocity, but the horizontal velocity will be faster.

In her response, Blake used real-life examples—shooting a gun and throwing a phone—as analogies to reason how to increase the horizontal range of a projectile object. However, when she threw the phone, she tossed it, which started it with a different initial angle from that of a bullet shot from a gun : “You just see it going like straight because it’s just high velocity.” Although she considered two directions of velocity when determining the optimal initial angle, she did not provide a scientifically reasonable explanation for why the initial angle should be lower than 45 degrees. It might be that Blake had learned that 45 degrees is the angle used to maximize range, but that she thought velocity would be more critical than the angle to determine the range, especially that the x -component of velocity would more important than the y -component because an object will fly faster horizontally than vertically when the x- component is greater. Thus, she lowered the initial angle a little bit. In the above statements, Blake did not demonstrate that she could consider the relationship between variables and link conceptual meanings to them (e.g., “Because I don’t see kg on the units at all” and “It doesn’t get that much time for vertical velocity, but the horizontal velocity will be faster”).

For the next question, we asked what would happen to the box’s motion after another box was placed on top of it. She said, “It would still be constant and stay at constant velocity in that motion.” We asked the question again, to clarify if she understood it.

Blake: Yeah. The velocity would be the same. After you let it go. So it will be at constant speed. And the force is proportional to the...wait, well acceleration is proportional to force and mass.

In her response, Blake attempted to apply Newton’s second law ( F = ma ), as the other two students had; however, she didn’t realize that acceleration is inversely proportional to mass, and therefore the velocity would be changed by the different acceleration. As a result, her response involved a misconception that mass doesn’t affect the speed of an object. In other words, she demonstrated her lack of understanding of the relationships between the variables (acceleration, velocity, mass, and force) involved in the situation. Her response to the questions confirmed that she explained scientific phenomena using variables in equations but failed to recognize the relationships among them. Instead she focused on individual variables, e.g., how acceleration will change as force changes, but did not explain how that would change velocity. She also did not explain how two components of velocity affect an object’s motion. Interestingly, she also used the unit of variable to justify her answer without applying conceptual meanings to it. For Blake, equations and units seemed to play important roles in explaining physical situations, but her connection of equations to physical situations was, at best, based on interpretations of individual variables.

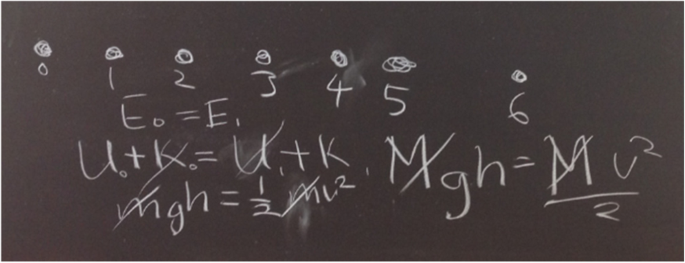

When we asked Blake about change in the skater’s highest speed when the skater’s mass increased, her original written response was that her highest speed would increase because the mass of the skater would require more energy. When we interviewed her, her answer was different from her original response.

Blake: I think it should stay the same. I was thinking of the formula.

When we asked her to explain in more detail, she wrote an equation on the board (Fig. 4 ) and explained what it meant.

Blake: The highest point, because there won’t be any kinetic energy. And it’ll be mgh . Also ½ mv 2 and it [ m ] cancels out. It was exactly the same. The speed was the same. But—wasn’t there a bar graph [in the simulation]? Well, the total energy was bigger [in the simulation]. The total energy. But the total energy was same—no bigger.

Similarly to Alex, Blake used an equation to explain that the skater’s speed wouldn’t change because v doesn’t contain m after canceling out. However, she did not describe why kinetic energy is zero at the highest point and why potential energy is zero at the bottom. It might be that she just did not mention this, but it was obvious that she did not understand how the object’s mass affected the system: “But the total energy was same—no bigger.” We further asked her how the total mechanical energy of the skater would change when the skater’s mass increased. This time, she said, “Well, the total energy was bigger. ‘Cause energy depends on mass and either height or speed of a person.” As seen in the response, she thought of variables in equations of gravitational potential energy ( mgh ) and kinetic energy ( \( \frac{1}{2} \) mv 2 ). When asked why she previously had said the total mechanical energy would be the same, she answered, “because energy is always conserved.” This illustrated her misconception that the amount of energy should always be the same regardless of mass; however, when she considered variables in equations of PE and KE, she answered the question accurately. Throughout the interview, we found that Blake’s strategy to solve questions was consistent across different tasks; she used formulas and units as her first approach. However, a difference between Blake and the other two students is that although she used equations and variables, she did not explain how the variables influenced each other; and how they would change as a specific situation changed. In other words, she did not translate equations into physical situations nor link conceptual meanings to the variables and the relationships between them. The findings showed that for Blake, equations were more likely used as a simple computational tool.

Blake’s explanation

Disconnection of students’ problem-solving strategies from physics lecture