- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.3: Inductive or Deductive? Two Different Approaches

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 12547

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Describe the inductive approach to research, and provide examples of inductive research.

- Describe the deductive approach to research, and provide examples of deductive research.

- Describe the ways that inductive and deductive approaches may be complementary.

Theories structure and inform sociological research. So, too, does research structure and inform theory. The reciprocal relationship between theory and research often becomes evident to students new to these topics when they consider the relationships between theory and research in inductive and deductive approaches to research. In both cases, theory is crucial. But the relationship between theory and research differs for each approach. Inductive and deductive approaches to research are quite different, but they can also be complementary. Let’s start by looking at each one and how they differ from one another. Then we’ll move on to thinking about how they complement one another.

Inductive Approaches and Some Examples

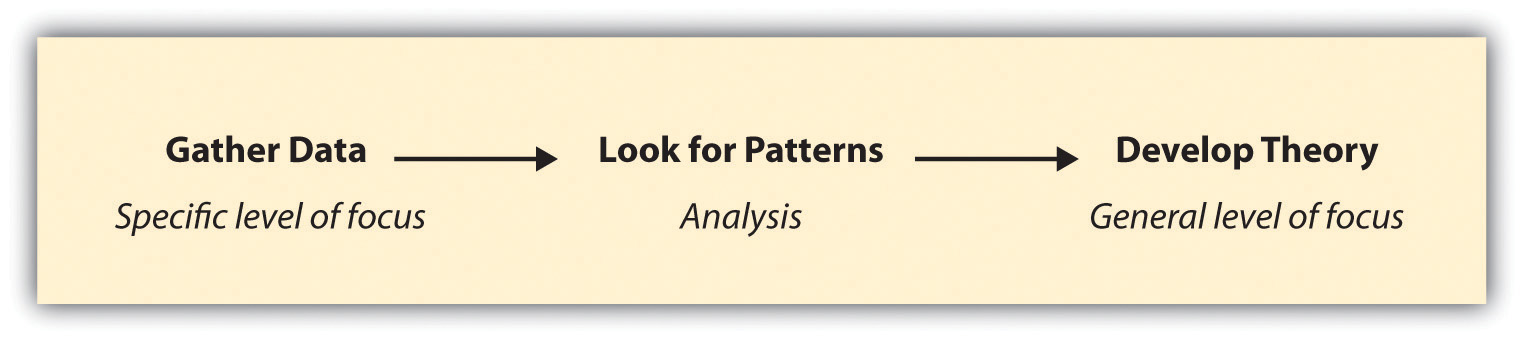

In an inductive approach to research, a researcher begins by collecting data that is relevant to his or her topic of interest. Once a substantial amount of data have been collected, the researcher will then take a breather from data collection, stepping back to get a bird’s eye view of her data. At this stage, the researcher looks for patterns in the data, working to develop a theory that could explain those patterns. Thus when researchers take an inductive approach, they start with a set of observations and then they move from those particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about those experiences. In other words, they move from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Figure 2.5 outlines the steps involved with an inductive approach to research.

Figure 2.5 Inductive Research

There are many good examples of inductive research, but we’ll look at just a few here. One fascinating recent study in which the researchers took an inductive approach was Katherine Allen, Christine Kaestle, and Abbie Goldberg’s study (2011)Allen, K. R., Kaestle, C. E., & Goldberg, A. E. (2011). More than just a punctuation mark: How boys and young men learn about menstruation. Journal of Family Issues, 32 , 129–156. of how boys and young men learn about menstruation. To understand this process, Allen and her colleagues analyzed the written narratives of 23 young men in which the men described how they learned about menstruation, what they thought of it when they first learned about it, and what they think of it now. By looking for patterns across all 23 men’s narratives, the researchers were able to develop a general theory of how boys and young men learn about this aspect of girls’ and women’s biology. They conclude that sisters play an important role in boys’ early understanding of menstruation, that menstruation makes boys feel somewhat separated from girls, and that as they enter young adulthood and form romantic relationships, young men develop more mature attitudes about menstruation.

In another inductive study, Kristin Ferguson and colleagues (Ferguson, Kim, & McCoy, 2011)Ferguson, K. M., Kim, M. A., & McCoy, S. (2011). Enhancing empowerment and leadership among homeless youth in agency and community settings: A grounded theory approach. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28 , 1–22. analyzed empirical data to better understand how best to meet the needs of young people who are homeless. The authors analyzed data from focus groups with 20 young people at a homeless shelter. From these data they developed a set of recommendations for those interested in applied interventions that serve homeless youth. The researchers also developed hypotheses for people who might wish to conduct further investigation of the topic. Though Ferguson and her colleagues did not test the hypotheses that they developed from their analysis, their study ends where most deductive investigations begin: with a set of testable hypotheses.

Deductive Approaches and Some Examples

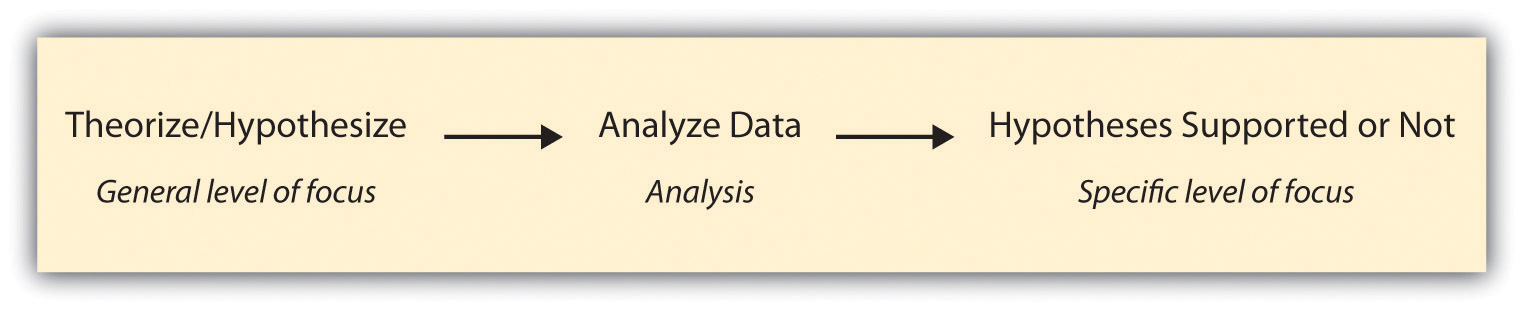

Researchers taking a deductive approach take the steps described earlier for inductive research and reverse their order. They start with a social theory that they find compelling and then test its implications with data. That is, they move from a more general level to a more specific one. A deductive approach to research is the one that people typically associate with scientific investigation. The researcher studies what others have done, reads existing theories of whatever phenomenon he or she is studying, and then tests hypotheses that emerge from those theories. Figure 2.6 outlines the steps involved with a deductive approach to research.

Figure 2.6 Deductive Research

While not all researchers follow a deductive approach, as you have seen in the preceding discussion, many do, and there are a number of excellent recent examples of deductive research. We’ll take a look at a couple of those next.

In a study of US law enforcement responses to hate crimes, Ryan King and colleagues (King, Messner, & Baller, 2009)King, R. D., Messner, S. F., & Baller, R. D. (2009). Contemporary hate crimes, law enforcement, and the legacy of racial violence. American Sociological Review, 74 , 291–315.hypothesized that law enforcement’s response would be less vigorous in areas of the country that had a stronger history of racial violence. The authors developed their hypothesis from their reading of prior research and theories on the topic. Next, they tested the hypothesis by analyzing data on states’ lynching histories and hate crime responses. Overall, the authors found support for their hypothesis.

In another recent deductive study, Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner (2011)Milkie, M. A., & Warner, C. H. (2011). Classroom learning environments and the mental health of first grade children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52 , 4–22. studied the effects of different classroom environments on first graders’ mental health. Based on prior research and theory, Milkie and Warner hypothesized that negative classroom features, such as a lack of basic supplies and even heat, would be associated with emotional and behavioral problems in children. The researchers found support for their hypothesis, demonstrating that policymakers should probably be paying more attention to the mental health outcomes of children’s school experiences, just as they track academic outcomes (American Sociological Association, 2011).The American Sociological Association wrote a press release on Milkie and Warner’s findings: American Sociological Association. (2011). Study: Negative classroom environment adversely affects children’s mental health. Retrieved from asanet.org/press/Negative_Cla...tal_Health.cfm

Complementary Approaches?

While inductive and deductive approaches to research seem quite different, they can actually be rather complementary. In some cases, researchers will plan for their research to include multiple components, one inductive and the other deductive. In other cases, a researcher might begin a study with the plan to only conduct either inductive or deductive research, but then he or she discovers along the way that the other approach is needed to help illuminate findings. Here is an example of each such case.

In the case of my collaborative research on sexual harassment, we began the study knowing that we would like to take both a deductive and an inductive approach in our work. We therefore administered a quantitative survey, the responses to which we could analyze in order to test hypotheses, and also conducted qualitative interviews with a number of the survey participants. The survey data were well suited to a deductive approach; we could analyze those data to test hypotheses that were generated based on theories of harassment. The interview data were well suited to an inductive approach; we looked for patterns across the interviews and then tried to make sense of those patterns by theorizing about them.

For one paper (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004),Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. (2004). Sexual harassment as a gendered expression of power. American Sociological Review, 69 , 64–92. we began with a prominent feminist theory of the sexual harassment of adult women and developed a set of hypotheses outlining how we expected the theory to apply in the case of younger women’s and men’s harassment experiences. We then tested our hypotheses by analyzing the survey data. In general, we found support for the theory that posited that the current gender system, in which heteronormative men wield the most power in the workplace, explained workplace sexual harassment—not just of adult women but of younger women and men as well. In a more recent paper (Blackstone, Houle, & Uggen, 2006),Blackstone, A., Houle, J., & Uggen, C. “At the time I thought it was great”: Age, experience, and workers’ perceptions of sexual harassment. Presented at the 2006 meetings of the American Sociological Association. Currently under review. we did not hypothesize about what we might find but instead inductively analyzed the interview data, looking for patterns that might tell us something about how or whether workers’ perceptions of harassment change as they age and gain workplace experience. From this analysis, we determined that workers’ perceptions of harassment did indeed shift as they gained experience and that their later definitions of harassment were more stringent than those they held during adolescence. Overall, our desire to understand young workers’ harassment experiences fully—in terms of their objective workplace experiences, their perceptions of those experiences, and their stories of their experiences—led us to adopt both deductive and inductive approaches in the work.

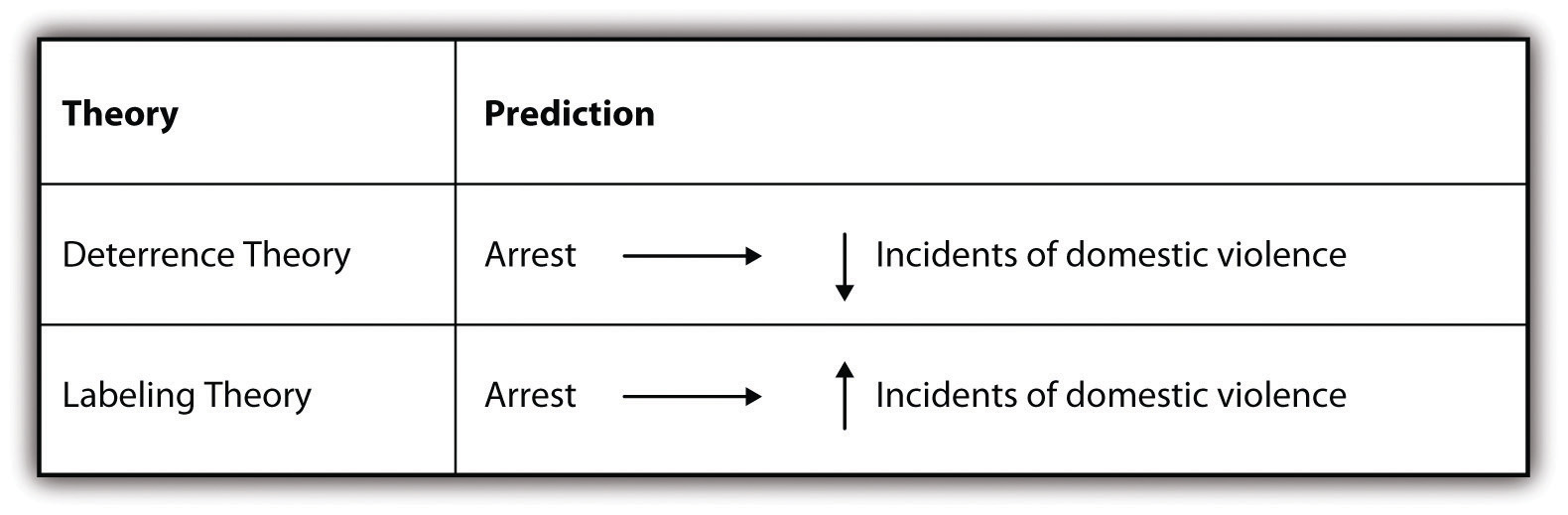

Researchers may not always set out to employ both approaches in their work but sometimes find that their use of one approach leads them to the other. One such example is described eloquently in Russell Schutt’s Investigating the Social World (2006).Schutt, R. K. (2006). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. As Schutt describes, researchers Lawrence Sherman and Richard Berk (1984)Sherman, L. W., & Berk, R. A. (1984). The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. American Sociological Review, 49 , 261–272. conducted an experiment to test two competing theories of the effects of punishment on deterring deviance (in this case, domestic violence). Specifically, Sherman and Berk hypothesized that deterrence theory would provide a better explanation of the effects of arresting accused batterers than labeling theory . Deterrence theory predicts that arresting an accused spouse batterer will reduce future incidents of violence. Conversely, labeling theory predicts that arresting accused spouse batterers will increase future incidents. Figure 2.7 summarizes the two competing theories and the predictions that Sherman and Berk set out to test.

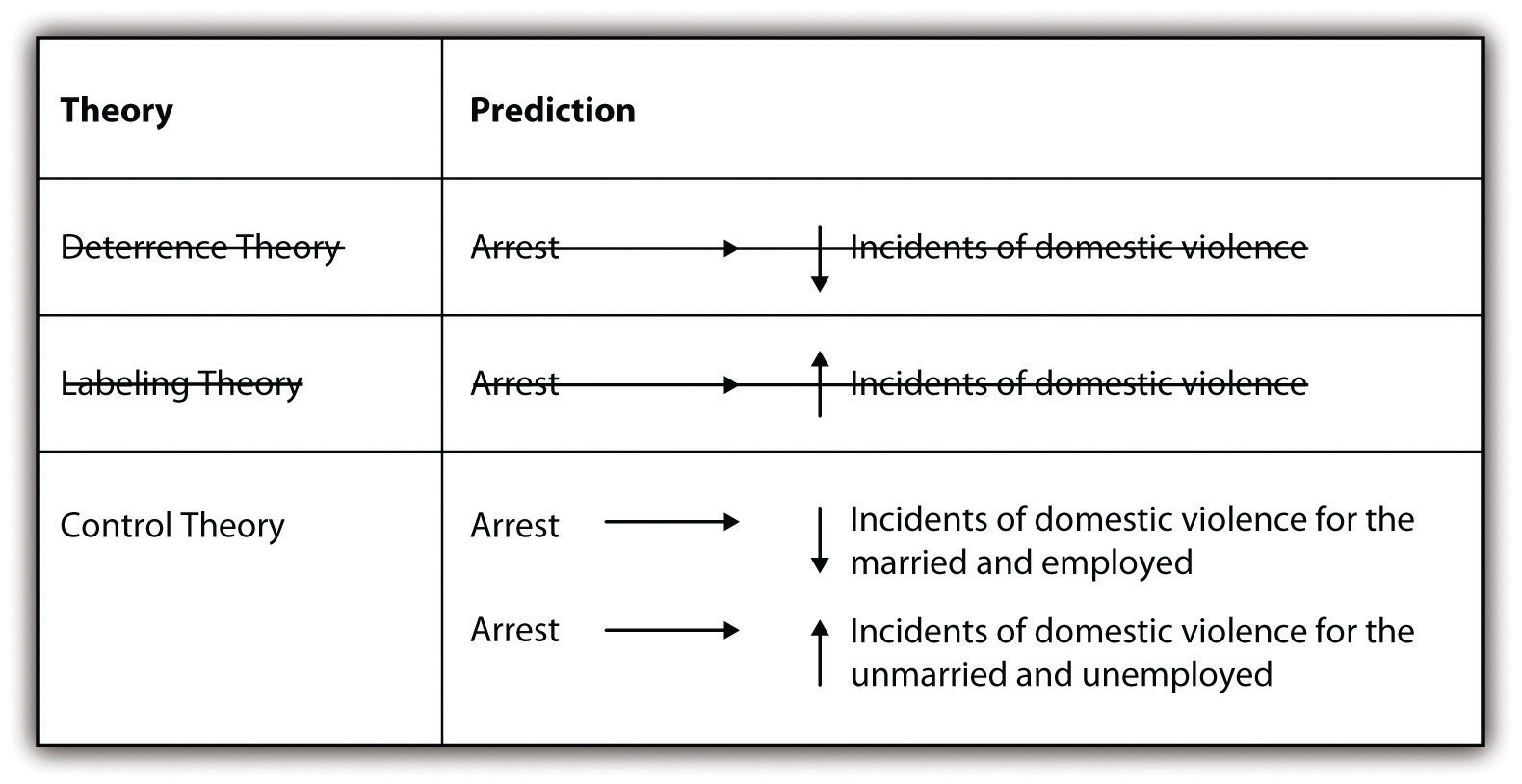

Figure 2.7 Predicting the Effects of Arrest on Future Spouse Battery

Sherman and Berk found, after conducting an experiment with the help of local police in one city, that arrest did in fact deter future incidents of violence, thus supporting their hypothesis that deterrence theory would better predict the effect of arrest. After conducting this research, they and other researchers went on to conduct similar experimentsThe researchers did what’s called replication. We’ll learn more about replication in Chapter 3. in six additional cities (Berk, Campbell, Klap, & Western, 1992; Pate & Hamilton, 1992; Sherman & Smith, 1992).Berk, R., Campbell, A., Klap, R., & Western, B. (1992). The deterrent effect of arrest in incidents of domestic violence: A Bayesian analysis of four field experiments. American Sociological Review, 57 , 698–708; Pate, A., & Hamilton, E. (1992). Formal and informal deterrents to domestic violence: The Dade county spouse assault experiment. American Sociological Review, 57 , 691–697; Sherman, L., & Smith, D. (1992). Crime, punishment, and stake in conformity: Legal and informal control of domestic violence. American Sociological Review, 57 , 680–690. Results from these follow-up studies were mixed. In some cases, arrest deterred future incidents of violence. In other cases, it did not. This left the researchers with new data that they needed to explain. The researchers therefore took an inductive approach in an effort to make sense of their latest empirical observations. The new studies revealed that arrest seemed to have a deterrent effect for those who were married and employed but that it led to increased offenses for those who were unmarried and unemployed. Researchers thus turned to control theory, which predicts that having some stake in conformity through the social ties provided by marriage and employment, as the better explanation.

Figure 2.8 Predicting the Effects of Arrest on Future Spouse Battery: A New Theory

What the Sherman and Berk research, along with the follow-up studies, shows us is that we might start with a deductive approach to research, but then, if confronted by new data that we must make sense of, we may move to an inductive approach. Russell Schutt depicts this process quite nicely in his text, and I’ve adapted his depiction here, in Figure 2.9.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The inductive approach involves beginning with a set of empirical observations, seeking patterns in those observations, and then theorizing about those patterns.

- The deductive approach involves beginning with a theory, developing hypotheses from that theory, and then collecting and analyzing data to test those hypotheses.

- Inductive and deductive approaches to research can be employed together for a more complete understanding of the topic that a researcher is studying.

- Though researchers don’t always set out to use both inductive and deductive strategies in their work, they sometimes find that new questions arise in the course of an investigation that can best be answered by employing both approaches.

Monty Python and Holy Grail :

(click to see video)

Do the townspeople take an inductive or deductive approach to determine whether the woman in question is a witch? What are some of the different sources of knowledge (recall Chapter 1) they rely on?

- Think about how you could approach a study of the relationship between gender and driving over the speed limit. How could you learn about this relationship using an inductive approach? What would a study of the same relationship look like if examined using a deductive approach? Try the same thing with any topic of your choice. How might you study the topic inductively? Deductively?

- Privacy Policy

Home » Inductive Vs Deductive Research

Inductive Vs Deductive Research

Table of Contents

Inductive and deductive research are two different approaches to conducting a research study. While they are different in their orientation and methods, they can both be used to generate new knowledge and advance scientific understanding.

Inductive Research

Inductive research is a bottom-up approach to research where a researcher starts with specific observations and data and then works to generate general principles or theories. This approach involves collecting data and analyzing it to identify patterns, themes, or categories. From these patterns, the researcher can develop theories or concepts that can explain the observations made in the data. Inductive research is often used in qualitative research, case studies, and grounded theory research.

Deductive Research

Deductive research is a top-down approach to research where a researcher starts with a theory or hypothesis and then tests it through data collection and analysis. This approach involves testing a specific hypothesis or theory and then drawing conclusions based on the results of the analysis. Deductive research is often used in quantitative research, experimental research, and survey research.

Difference between Inductive and Deductive Research

Here are some key differences between inductive and deductive research:

Both inductive and deductive research have their strengths and weaknesses, and the choice of which to use depends on the nature of the research question, the research objectives, and the available resources. Inductive research is useful when a researcher wants to explore a new area of inquiry or when there is limited theory or previous research available, while deductive research is useful when a researcher wants to test a specific theory or hypothesis.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Exploratory Vs Explanatory Research

Basic Vs Applied Research

Generative Vs Evaluative Research

Reliability Vs Validity

Longitudinal Vs Cross-Sectional Research

Qualitative Vs Quantitative Research

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, qualitative research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis.

Qualitative Research Journal

ISSN : 1443-9883

Article publication date: 31 October 2018

Issue publication date: 15 November 2018

The purpose of this paper is to explain the rationale for choosing the qualitative approach to research human resources practices, namely, recruitment and selection, training and development, performance management, rewards management, employee communication and participation, diversity management and work and life balance using deductive and inductive approaches to analyse data. The paper adopts an emic perspective that favours the study of transfer of human resource management practices from the point of view of employees and host country managers in subsidiaries of western multinational enterprises in Ghana.

Design/methodology/approach

Despite the numerous examples of qualitative methods of data generation, little is known particularly to the novice researcher about how to analyse qualitative data. This paper develops a model to explain in a systematic manner how to methodically analyse qualitative data using both deductive and inductive approaches.

The deductive and inductive approaches provide a comprehensive approach in analysing qualitative data. The process involves immersing oneself in the data reading and digesting in order to make sense of the whole set of data and to understand what is going on.

Originality/value

This paper fills a serious gap in qualitative data analysis which is deemed complex and challenging with limited attention in the methodological literature particularly in a developing country context, Ghana.

- Qualitative

- Emic interviews documents

Azungah, T. (2018), "Qualitative research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis", Qualitative Research Journal , Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 383-400. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00035

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Generalization and Replication–A Representationalist View

In this paper, we provide a re-interpretation of qualitative and quantitative modeling from a representationalist perspective. In this view, both approaches attempt to construct abstract representations of empirical relational structures. Whereas quantitative research uses variable-based models that abstract from individual cases, qualitative research favors case-based models that abstract from individual characteristics. Variable-based models are usually stated in the form of quantified sentences (scientific laws). This syntactic structure implies that sentences about individual cases are derived using deductive reasoning. In contrast, case-based models are usually stated using context-dependent existential sentences (qualitative statements). This syntactic structure implies that sentences about other cases are justifiable by inductive reasoning. We apply this representationalist perspective to the problems of generalization and replication. Using the analytical framework of modal logic, we argue that the modes of reasoning are often not only applied to the context that has been studied empirically, but also on a between-contexts level. Consequently, quantitative researchers mostly adhere to a top-down strategy of generalization, whereas qualitative researchers usually follow a bottom-up strategy of generalization. Depending on which strategy is employed, the role of replication attempts is very different. In deductive reasoning, replication attempts serve as empirical tests of the underlying theory. Therefore, failed replications imply a faulty theory. From an inductive perspective, however, replication attempts serve to explore the scope of the theory. Consequently, failed replications do not question the theory per se , but help to shape its boundary conditions. We conclude that quantitative research may benefit from a bottom-up generalization strategy as it is employed in most qualitative research programs. Inductive reasoning forces us to think about the boundary conditions of our theories and provides a framework for generalization beyond statistical testing. In this perspective, failed replications are just as informative as successful replications, because they help to explore the scope of our theories.

Introduction

Qualitative and quantitative research strategies have long been treated as opposing paradigms. In recent years, there have been attempts to integrate both strategies. These “mixed methods” approaches treat qualitative and quantitative methodologies as complementary, rather than opposing, strategies (Creswell, 2015 ). However, whilst acknowledging that both strategies have their benefits, this “integration” remains purely pragmatic. Hence, mixed methods methodology does not provide a conceptual unification of the two approaches.

Lacking a common methodological background, qualitative and quantitative research methodologies have developed rather distinct standards with regard to the aims and scope of empirical science (Freeman et al., 2007 ). These different standards affect the way researchers handle contradictory empirical findings. For example, many empirical findings in psychology have failed to replicate in recent years (Klein et al., 2014 ; Open Science, Collaboration, 2015 ). This “replication crisis” has been discussed on statistical, theoretical and social grounds and continues to have a wide impact on quantitative research practices like, for example, open science initiatives, pre-registered studies and a re-evaluation of statistical significance testing (Everett and Earp, 2015 ; Maxwell et al., 2015 ; Shrout and Rodgers, 2018 ; Trafimow, 2018 ; Wiggins and Chrisopherson, 2019 ).

However, qualitative research seems to be hardly affected by this discussion. In this paper, we argue that the latter is a direct consequence of how the concept of generalizability is conceived in the two approaches. Whereas most of quantitative psychology is committed to a top-down strategy of generalization based on the idea of random sampling from an abstract population, qualitative studies usually rely on a bottom-up strategy of generalization that is grounded in the successive exploration of the field by means of theoretically sampled cases.

Here, we show that a common methodological framework for qualitative and quantitative research methodologies is possible. We accomplish this by introducing a formal description of quantitative and qualitative models from a representationalist perspective: both approaches can be reconstructed as special kinds of representations for empirical relational structures. We then use this framework to analyze the generalization strategies used in the two approaches. These turn out to be logically independent of the type of model. This has wide implications for psychological research. First, a top-down generalization strategy is compatible with a qualitative modeling approach. This implies that mainstream psychology may benefit from qualitative methods when a numerical representation turns out to be difficult or impossible, without the need to commit to a “qualitative” philosophy of science. Second, quantitative research may exploit the bottom-up generalization strategy that is inherent to many qualitative approaches. This offers a new perspective on unsuccessful replications by treating them not as scientific failures, but as a valuable source of information about the scope of a theory.

The Quantitative Strategy–Numbers and Functions

Quantitative science is about finding valid mathematical representations for empirical phenomena. In most cases, these mathematical representations have the form of functional relations between a set of variables. One major challenge of quantitative modeling consists in constructing valid measures for these variables. Formally, to measure a variable means to construct a numerical representation of the underlying empirical relational structure (Krantz et al., 1971 ). For example, take the behaviors of a group of students in a classroom: “to listen,” “to take notes,” and “to ask critical questions.” One may now ask whether is possible to assign numbers to the students, such that the relations between the assigned numbers are of the same kind as the relations between the values of an underlying variable, like e.g., “engagement.” The observed behaviors in the classroom constitute an empirical relational structure, in the sense that for every student-behavior tuple, one can observe whether it is true or not. These observations can be represented in a person × behavior matrix 1 (compare Figure 1 ). Given this relational structure satisfies certain conditions (i.e., the axioms of a measurement model), one can assign numbers to the students and the behaviors, such that the relations between the numbers resemble the corresponding numerical relations. For example, if there is a unique ordering in the empirical observations with regard to which person shows which behavior, the assigned numbers have to constitute a corresponding unique ordering, as well. Such an ordering coincides with the person × behavior matrix forming a triangle shaped relation and is formally represented by a Guttman scale (Guttman, 1944 ). There are various measurement models available for different empirical structures (Suppes et al., 1971 ). In the case of probabilistic relations, Item-Response models may be considered as a special kind of measurement model (Borsboom, 2005 ).

Constructing a numerical representation from an empirical relational structure; Due to the unique ordering of persons with regard to behaviors (indicated by the triangular shape of the relation), it is possible to construct a Guttman scale by assigning a number to each of the individuals, representing the number of relevant behaviors shown by the individual. The resulting variable (“engagement”) can then be described by means of statistical analyses, like, e.g., plotting the frequency distribution.

Although essential, measurement is only the first step of quantitative modeling. Consider a slightly richer empirical structure, where we observe three additional behaviors: “to doodle,” “to chat,” and “to play.” Like above, one may ask, whether there is a unique ordering of the students with regard to these behaviors that can be represented by an underlying variable (i.e., whether the matrix forms a Guttman scale). If this is the case, we may assign corresponding numbers to the students and call this variable “distraction.” In our example, such a representation is possible. We can thus assign two numbers to each student, one representing his or her “engagement” and one representing his or her “distraction” (compare Figure 2 ). These measurements can now be used to construct a quantitative model by relating the two variables by a mathematical function. In the simplest case, this may be a linear function. This functional relation constitutes a quantitative model of the empirical relational structure under study (like, e.g., linear regression). Given the model equation and the rules for assigning the numbers (i.e., the instrumentations of the two variables), the set of admissible empirical structures is limited from all possible structures to a rather small subset. This constitutes the empirical content of the model 2 (Popper, 1935 ).

Constructing a numerical model from an empirical relational structure; Since there are two distinct classes of behaviors that each form a Guttman scale, it is possible to assign two numbers to each individual, correspondingly. The resulting variables (“engagement” and “distraction”) can then be related by a mathematical function, which is indicated by the scatterplot and red line on the right hand side.

The Qualitative Strategy–Categories and Typologies

The predominant type of analysis in qualitative research consists in category formation. By constructing descriptive systems for empirical phenomena, it is possible to analyze the underlying empirical structure at a higher level of abstraction. The resulting categories (or types) constitute a conceptual frame for the interpretation of the observations. Qualitative researchers differ considerably in the way they collect and analyze data (Miles et al., 2014 ). However, despite the diverse research strategies followed by different qualitative methodologies, from a formal perspective, most approaches build on some kind of categorization of cases that share some common features. The process of category formation is essential in many qualitative methodologies, like, for example, qualitative content analysis, thematic analysis, grounded theory (see Flick, 2014 for an overview). Sometimes these features are directly observable (like in our classroom example), sometimes they are themselves the result of an interpretative process (e.g., Scheunpflug et al., 2016 ).

In contrast to quantitative methodologies, there have been little attempts to formalize qualitative research strategies (compare, however, Rihoux and Ragin, 2009 ). However, there are several statistical approaches to non-numerical data that deal with constructing abstract categories and establishing relations between these categories (Agresti, 2013 ). Some of these methods are very similar to qualitative category formation on a conceptual level. For example, cluster analysis groups cases into homogenous categories (clusters) based on their similarity on a distance metric.

Although category formation can be formalized in a mathematically rigorous way (Ganter and Wille, 1999 ), qualitative research hardly acknowledges these approaches. 3 However, in order to find a common ground with quantitative science, it is certainly helpful to provide a formal interpretation of category systems.

Let us reconsider the above example of students in a classroom. The quantitative strategy was to assign numbers to the students with regard to variables and to relate these variables via a mathematical function. We can analyze the same empirical structure by grouping the behaviors to form abstract categories. If the aim is to construct an empirically valid category system, this grouping is subject to constraints, analogous to those used to specify a measurement model. The first and most important constraint is that the behaviors must form equivalence classes, i.e., within categories, behaviors need to be equivalent, and across categories, they need to be distinct (formally, the relational structure must obey the axioms of an equivalence relation). When objects are grouped into equivalence classes, it is essential to specify the criterion for empirical equivalence. In qualitative methodology, this is sometimes referred to as the tertium comparationis (Flick, 2014 ). One possible criterion is to group behaviors such that they constitute a set of specific common attributes of a group of people. In our example, we might group the behaviors “to listen,” “to take notes,” and “to doodle,” because these behaviors are common to the cases B, C, and D, and they are also specific for these cases, because no other person shows this particular combination of behaviors. The set of common behaviors then forms an abstract concept (e.g., “moderate distraction”), while the set of persons that show this configuration form a type (e.g., “the silent dreamer”). Formally, this means to identify the maximal rectangles in the underlying empirical relational structure (see Figure 3 ). This procedure is very similar to the way we constructed a Guttman scale, the only difference being that we now use different aspects of the empirical relational structure. 4 In fact, the set of maximal rectangles can be determined by an automated algorithm (Ganter, 2010 ), just like the dimensionality of an empirical structure can be explored by psychometric scaling methods. Consequently, we can identify the empirical content of a category system or a typology as the set of empirical structures that conforms to it. 5 Whereas the quantitative strategy was to search for scalable sub-matrices and then relate the constructed variables by a mathematical function, the qualitative strategy is to construct an empirical typology by grouping cases based on their specific similarities. These types can then be related to one another by a conceptual model that describes their semantic and empirical overlap (see Figure 3 , right hand side).

Constructing a conceptual model from an empirical relational structure; Individual behaviors are grouped to form abstract types based on them being shared among a specific subset of the cases. Each type constitutes a set of specific commonalities of a class of individuals (this is indicated by the rectangles on the left hand side). The resulting types (“active learner,” “silent dreamer,” “distracted listener,” and “troublemaker”) can then be related to one another to explicate their semantic and empirical overlap, as indicated by the Venn-diagram on the right hand side.

Variable-Based Models and Case-Based Models

In the previous section, we have argued that qualitative category formation and quantitative measurement can both be characterized as methods to construct abstract representations of empirical relational structures. Instead of focusing on different philosophical approaches to empirical science, we tried to stress the formal similarities between both approaches. However, it is worth also exploring the dissimilarities from a formal perspective.

Following the above analysis, the quantitative approach can be characterized by the use of variable-based models, whereas the qualitative approach is characterized by case-based models (Ragin, 1987 ). Formally, we can identify the rows of an empirical person × behavior matrix with a person-space, and the columns with a corresponding behavior-space. A variable-based model abstracts from the single individuals in a person-space to describe the structure of behaviors on a population level. A case-based model, on the contrary, abstracts from the single behaviors in a behavior-space to describe individual case configurations on the level of abstract categories (see Table 1 ).

Variable-based models and case-based models.

From a representational perspective, there is no a priori reason to favor one type of model over the other. Both approaches provide different analytical tools to construct an abstract representation of an empirical relational structure. However, since the two modeling approaches make use of different information (person-space vs. behavior-space), this comes with some important implications for the researcher employing one of the two strategies. These are concerned with the role of deductive and inductive reasoning.

In variable-based models, empirical structures are represented by functional relations between variables. These are usually stated as scientific laws (Carnap, 1928 ). Formally, these laws correspond to logical expressions of the form

In plain text, this means that y is a function of x for all objects i in the relational structure under consideration. For example, in the above example, one may formulate the following law: for all students in the classroom it holds that “distraction” is a monotone decreasing function of “engagement.” Such a law can be used to derive predictions for single individuals by means of logical deduction: if the above law applies to all students in the classroom, it is possible to calculate the expected distraction from a student's engagement. An empirical observation can now be evaluated against this prediction. If the prediction turns out to be false, the law can be refuted based on the principle of falsification (Popper, 1935 ). If a scientific law repeatedly withstands such empirical tests, it may be considered to be valid with regard to the relational structure under consideration.

In case-based models, there are no laws about a population, because the model does not abstract from the cases but from the observed behaviors. A case-based model describes the underlying structure in terms of existential sentences. Formally, this corresponds to a logical expression of the form

In plain text, this means that there is at least one case i for which the condition XYZ holds. For example, the above category system implies that there is at least one active learner. This is a statement about a singular observation. It is impossible to deduce a statement about another person from an existential sentence like this. Therefore, the strategy of falsification cannot be applied to test the model's validity in a specific context. If one wishes to generalize to other cases, this is accomplished by inductive reasoning, instead. If we observed one person that fulfills the criteria of calling him or her an active learner, we can hypothesize that there may be other persons that are identical to the observed case in this respect. However, we do not arrive at this conclusion by logical deduction, but by induction.

Despite this important distinction, it would be wrong to conclude that variable-based models are intrinsically deductive and case-based models are intrinsically inductive. 6 Both types of reasoning apply to both types of models, but on different levels. Based on a person-space, in a variable-based model one can use deduction to derive statements about individual persons from abstract population laws. There is an analogous way of reasoning for case-based models: because they are based on a behavior space, it is possible to deduce statements about singular behaviors. For example, if we know that Peter is an active learner, we can deduce that he takes notes in the classroom. This kind of deductive reasoning can also be applied on a higher level of abstraction to deduce thematic categories from theoretical assumptions (Braun and Clarke, 2006 ). Similarly, there is an analog for inductive generalization from the perspective of variable-based modeling: since the laws are only quantified over the person-space, generalizations to other behaviors rely on inductive reasoning. For example, it is plausible to assume that highly engaged students tend to do their homework properly–however, in our example this behavior has never been observed. Hence, in variable-based models we usually generalize to other behaviors by means of induction. This kind of inductive reasoning is very common when empirical results are generalized from the laboratory to other behavioral domains.

Although inductive and deductive reasoning are used in qualitative and quantitative research, it is important to stress the different roles of induction and deduction when models are applied to cases. A variable-based approach implies to draw conclusions about cases by means of logical deduction; a case-based approach implies to draw conclusions about cases by means of inductive reasoning. In the following, we build on this distinction to differentiate between qualitative (bottom-up) and quantitative (top-down) strategies of generalization.

Generalization and the Problem of Replication

We will now extend the formal analysis of quantitative and qualitative approaches to the question of generalization and replicability of empirical findings. For this sake, we have to introduce some concepts of formal logic. Formal logic is concerned with the validity of arguments. It provides conditions to evaluate whether certain sentences (conclusions) can be derived from other sentences (premises). In this context, a theory is nothing but a set of sentences (also called axioms). Formal logic provides tools to derive new sentences that must be true, given the axioms are true (Smith, 2020 ). These derived sentences are called theorems or, in the context of empirical science, predictions or hypotheses . On the syntactic level, the rules of logic only state how to evaluate the truth of a sentence relative to its premises. Whether or not sentences are actually true, is formally specified by logical semantics.

On the semantic level, formal logic is intrinsically linked to set-theory. For example, a logical statement like “all dogs are mammals,” is true if and only if the set of dogs is a subset of the set of mammals. Similarly, the sentence “all chatting students doodle” is true if and only if the set of chatting students is a subset of the set of doodling students (compare Figure 3 ). Whereas, the first sentence is analytically true due to the way we define the words “dog” and “mammal,” the latter can be either true or false, depending on the relational structure we actually observe. We can thus interpret an empirical relational structure as the truth criterion of a scientific theory. From a logical point of view, this corresponds to the semantics of a theory. As shown above, variable-based and case-based models both give a formal representation of the same kinds of empirical structures. Accordingly, both types of models can be stated as formal theories. In the variable-based approach, this corresponds to a set of scientific laws that are quantified over the members of an abstract population (these are the axioms of the theory). In the case-based approach, this corresponds to a set of abstract existential statements about a specific class of individuals.

In contrast to mathematical axiom systems, empirical theories are usually not considered to be necessarily true. This means that even if we find no evidence against a theory, it is still possible that it is actually wrong. We may know that a theory is valid in some contexts, yet it may fail when applied to a new set of behaviors (e.g., if we use a different instrumentation to measure a variable) or a new population (e.g., if we draw a new sample).

From a logical perspective, the possibility that a theory may turn out to be false stems from the problem of contingency . A statement is contingent, if it is both, possibly true and possibly false. Formally, we introduce two modal operators: □ to designate logical necessity, and ◇ to designate logical possibility. Semantically, these operators are very similar to the existential quantifier, ∃, and the universal quantifier, ∀. Whereas ∃ and ∀ refer to the individual objects within one relational structure, the modal operators □ and ◇ range over so-called possible worlds : a statement is possibly true, if and only if it is true in at least one accessible possible world, and a statement is necessarily true if and only if it is true in every accessible possible world (Hughes and Cresswell, 1996 ). Logically, possible worlds are mathematical abstractions, each consisting of a relational structure. Taken together, the relational structures of all accessible possible worlds constitute the formal semantics of necessity, possibility and contingency. 7

In the context of an empirical theory, each possible world may be identified with an empirical relational structure like the above classroom example. Given the set of intended applications of a theory (the scope of the theory, one may say), we can now construct possible world semantics for an empirical theory: each intended application of the theory corresponds to a possible world. For example, a quantified sentence like “all chatting students doodle” may be true in one classroom and false in another one. In terms of possible worlds, this would correspond to a statement of contingency: “it is possible that all chatting students doodle in one classroom, and it is possible that they don't in another classroom.” Note that in the above expression, “all students” refers to the students in only one possible world, whereas “it is possible” refers to the fact that there is at least one possible world for each of the specified cases.

To apply these possible world semantics to quantitative research, let us reconsider how generalization to other cases works in variable-based models. Due to the syntactic structure of quantitative laws, we can deduce predictions for singular observations from an expression of the form ∀ i : y i = f ( x i ). Formally, the logical quantifier ∀ ranges only over the objects of the corresponding empirical relational structure (in our example this would refer to the students in the observed classroom). But what if we want to generalize beyond the empirical structure we actually observed? The standard procedure is to assume an infinitely large, abstract population from which a random sample is drawn. Given the truth of the theory, we can deduce predictions about what we may observe in the sample. Since usually we deal with probabilistic models, we can evaluate our theory by means of the conditional probability of the observations, given the theory holds. This concept of conditional probability is the foundation of statistical significance tests (Hogg et al., 2013 ), as well as Bayesian estimation (Watanabe, 2018 ). In terms of possible world semantics, the random sampling model implies that all possible worlds (i.e., all intended applications) can be conceived as empirical sub-structures from a greater population structure. For example, the empirical relational structure constituted by the observed behaviors in a classroom would be conceived as a sub-matrix of the population person × behavior matrix. It follows that, if a scientific law is true in the population, it will be true in all possible worlds, i.e., it will be necessarily true. Formally, this corresponds to an expression of the form

The statistical generalization model thus constitutes a top-down strategy for dealing with individual contexts that is analogous to the way variable-based models are applied to individual cases (compare Table 1 ). Consequently, if we apply a variable-based model to a new context and find out that it does not fit the data (i.e., there is a statistically significant deviation from the model predictions), we have reason to doubt the validity of the theory. This is what makes the problem of low replicability so important: we observe that the predictions are wrong in a new study; and because we apply a top-down strategy of generalization to contexts beyond the ones we observed, we see our whole theory at stake.

Qualitative research, on the contrary, follows a different strategy of generalization. Since case-based models are formulated by a set of context-specific existential sentences, there is no need for universal truth or necessity. In contrast to statistical generalization to other cases by means of random sampling from an abstract population, the usual strategy in case-based modeling is to employ a bottom-up strategy of generalization that is analogous to the way case-based models are applied to individual cases. Formally, this may be expressed by stating that the observed qualia exist in at least one possible world, i.e., the theory is possibly true:

This statement is analogous to the way we apply case-based models to individual cases (compare Table 1 ). Consequently, the set of intended applications of the theory does not follow from a sampling model, but from theoretical assumptions about which cases may be similar to the observed cases with respect to certain relevant characteristics. For example, if we observe that certain behaviors occur together in one classroom, following a bottom-up strategy of generalization, we will hypothesize why this might be the case. If we do not replicate this finding in another context, this does not question the model itself, since it was a context-specific theory all along. Instead, we will revise our hypothetical assumptions about why the new context is apparently less similar to the first one than we originally thought. Therefore, if an empirical finding does not replicate, we are more concerned about our understanding of the cases than about the validity of our theory.

Whereas statistical generalization provides us with a formal (and thus somehow more objective) apparatus to evaluate the universal validity of our theories, the bottom-up strategy forces us to think about the class of intended applications on theoretical grounds. This means that we have to ask: what are the boundary conditions of our theory? In the above classroom example, following a bottom-up strategy, we would build on our preliminary understanding of the cases in one context (e.g., a public school) to search for similar and contrasting cases in other contexts (e.g., a private school). We would then re-evaluate our theoretical description of the data and explore what makes cases similar or dissimilar with regard to our theory. This enables us to expand the class of intended applications alongside with the theory.

Of course, none of these strategies is superior per se . Nevertheless, they rely on different assumptions and may thus be more or less adequate in different contexts. The statistical strategy relies on the assumption of a universal population and invariant measurements. This means, we assume that (a) all samples are drawn from the same population and (b) all variables refer to the same behavioral classes. If these assumptions are true, statistical generalization is valid and therefore provides a valuable tool for the testing of empirical theories. The bottom-up strategy of generalization relies on the idea that contexts may be classified as being more or less similar based on characteristics that are not part of the model being evaluated. If such a similarity relation across contexts is feasible, the bottom-up strategy is valid, as well. Depending on the strategy of generalization, replication of empirical research serves two very different purposes. Following the (top-down) principle of generalization by deduction from scientific laws, replications are empirical tests of the theory itself, and failed replications question the theory on a fundamental level. Following the (bottom-up) principle of generalization by induction to similar contexts, replications are a means to explore the boundary conditions of a theory. Consequently, failed replications question the scope of the theory and help to shape the set of intended applications.

We have argued that quantitative and qualitative research are best understood by means of the structure of the employed models. Quantitative science mainly relies on variable-based models and usually employs a top-down strategy of generalization from an abstract population to individual cases. Qualitative science prefers case-based models and usually employs a bottom-up strategy of generalization. We further showed that failed replications have very different implications depending on the underlying strategy of generalization. Whereas in the top-down strategy, replications are used to test the universal validity of a model, in the bottom-up strategy, replications are used to explore the scope of a model. We will now address the implications of this analysis for psychological research with regard to the problem of replicability.

Modern day psychology almost exclusively follows a top-down strategy of generalization. Given the quantitative background of most psychological theories, this is hardly surprising. Following the general structure of variable-based models, the individual case is not the focus of the analysis. Instead, scientific laws are stated on the level of an abstract population. Therefore, when applying the theory to a new context, a statistical sampling model seems to be the natural consequence. However, this is not the only possible strategy. From a logical point of view, there is no reason to assume that a quantitative law like ∀ i : y i = f ( x i ) implies that the law is necessarily true, i.e.,: □(∀ i : y i = f ( x i )). Instead, one might just as well define the scope of the theory following an inductive strategy. 8 Formally, this would correspond to the assumption that the observed law is possibly true, i.e.,: ◇(∀ i : y i = f ( x i )). For example, we may discover a functional relation between “engagement” and “distraction” without referring to an abstract universal population of students. Instead, we may hypothesize under which conditions this functional relation may be valid and use these assumptions to inductively generalize to other cases.

If we take this seriously, this would require us to specify the intended applications of the theory: in which contexts do we expect the theory to hold? Or, equivalently, what are the boundary conditions of the theory? These boundary conditions may be specified either intensionally, i.e., by giving external criteria for contexts being similar enough to the ones already studied to expect a successful application of the theory. Or they may be specified extensionally, by enumerating the contexts where the theory has already been shown to be valid. These boundary conditions need not be restricted to the population we refer to, but include all kinds of contextual factors. Therefore, adopting a bottom-up strategy, we are forced to think about these factors and make them an integral part of our theories.

In fact, there is good reason to believe that bottom-up generalization may be more adequate in many psychological studies. Apart from the pitfalls associated with statistical generalization that have been extensively discussed in recent years (e.g., p-hacking, underpowered studies, publication bias), it is worth reflecting on whether the underlying assumptions are met in a particular context. For example, many samples used in experimental psychology are not randomly drawn from a large population, but are convenience samples. If we use statistical models with non-random samples, we have to assume that the observations vary as if drawn from a random sample. This may indeed be the case for randomized experiments, because all variation between the experimental conditions apart from the independent variable will be random due to the randomization procedure. In this case, a classical significance test may be regarded as an approximation to a randomization test (Edgington and Onghena, 2007 ). However, if we interpret a significance test as an approximate randomization test, we test not for generalization but for internal validity. Hence, even if we use statistical significance tests when assumptions about random sampling are violated, we still have to use a different strategy of generalization. This issue has been discussed in the context of small-N studies, where variable-based models are applied to very small samples, sometimes consisting of only one individual (Dugard et al., 2012 ). The bottom-up strategy of generalization that is employed by qualitative researchers, provides such an alternative.

Another important issue in this context is the question of measurement invariance. If we construct a variable-based model in one context, the variables refer to those behaviors that constitute the underlying empirical relational structure. For example, we may construct an abstract measure of “distraction” using the observed behaviors in a certain context. We will then use the term “distraction” as a theoretical term referring to the variable we have just constructed to represent the underlying empirical relational structure. Let us now imagine we apply this theory to a new context. Even if the individuals in our new context are part of the same population, we may still get into trouble if the observed behaviors differ from those used in the original study. How do we know whether these behaviors constitute the same variable? We have to ensure that in any new context, our measures are valid for the variables in our theory. Without a proper measurement model, this will be hard to achieve (Buntins et al., 2017 ). Again, we are faced with the necessity to think of the boundary conditions of our theories. In which contexts (i.e., for which sets of individuals and behaviors) do we expect our theory to work?

If we follow the rationale of inductive generalization, we can explore the boundary conditions of a theory with every new empirical study. We thus widen the scope of our theory by comparing successful applications in different contexts and unsuccessful applications in similar contexts. This may ultimately lead to a more general theory, maybe even one of universal scope. However, unless we have such a general theory, we might be better off, if we treat unsuccessful replications not as a sign of failure, but as a chance to learn.

Author Contributions

MB conceived the original idea and wrote the first draft of the paper. MS helped to further elaborate and scrutinize the arguments. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Annette Scheunpflug for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

1 A person × behavior matrix constitutes a very simple relational structure that is common in psychological research. This is why it is chosen here as a minimal example. However, more complex structures are possible, e.g., by relating individuals to behaviors over time, with individuals nested within groups etc. For a systematic overview, compare Coombs ( 1964 ).

2 This notion of empirical content applies only to deterministic models. The empirical content of a probabilistic model consists in the probability distribution over all possible empirical structures.

3 For example, neither the SAGE Handbook of qualitative data analysis edited by Flick ( 2014 ) nor the Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research edited by Leavy ( 2014 ) mention formal approaches to category formation.

4 Note also that the described structure is empirically richer than a nominal scale. Therefore, a reduction of qualitative category formation to be a special (and somehow trivial) kind of measurement is not adequate.

5 It is possible to extend this notion of empirical content to the probabilistic case (this would correspond to applying a latent class analysis). But, since qualitative research usually does not rely on formal algorithms (neither deterministic nor probabilistic), there is currently little practical use of such a concept.

6 We do not elaborate on abductive reasoning here, since, given an empirical relational structure, the concept can be applied to both types of models in the same way (Schurz, 2008 ). One could argue that the underlying relational structure is not given a priori but has to be constructed by the researcher and will itself be influenced by theoretical expectations. Therefore, abductive reasoning may be necessary to establish an empirical relational structure in the first place.

7 We shall not elaborate on the metaphysical meaning of possible worlds here, since we are only concerned with empirical theories [but see Tooley ( 1999 ), for an overview].

8 Of course, this also means that it would be equally reasonable to employ a top-down strategy of generalization using a case-based model by postulating that □(∃ i : XYZ i ). The implications for case-based models are certainly worth exploring, but lie beyond the scope of this article.

- Agresti A. (2013). Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd Edn. Wiley Series In Probability And Statistics . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Borsboom D. (2005). Measuring the Mind: Conceptual Issues in Contemporary Psychometrics . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 10.1017/CBO9780511490026 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology . Qual. Res. Psychol . 3 , 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buntins M., Buntins K., Eggert F. (2017). Clarifying the concept of validity: from measurement to everyday language . Theory Psychol. 27 , 703–710. 10.1177/0959354317702256 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carnap R. (1928). The Logical Structure of the World . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coombs C. H. (1964). A Theory of Data . New York, NY: Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell J. W. (2015). A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dugard P., File P., Todman J. B. (2012). Single-Case and Small-N Experimental Designs: A Practical Guide to Randomization Tests 2nd Edn . New York, NY: Routledge; 10.4324/9780203180938 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edgington E., Onghena P. (2007). Randomization Tests, 4th Edn. Statistics. Hoboken, NJ: CRC Press; 10.1201/9781420011814 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Everett J. A. C., Earp B. D. (2015). A tragedy of the (academic) commons: interpreting the replication crisis in psychology as a social dilemma for early-career researchers . Front. Psychol . 6 :1152. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01152 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flick U. (Ed.). (2014). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis . London: Sage; 10.4135/9781446282243 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman M., Demarrais K., Preissle J., Roulston K., St. Pierre E. A. (2007). Standards of evidence in qualitative research: an incitement to discourse . Educ. Res. 36 , 25–32. 10.3102/0013189X06298009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ganter B. (2010). Two basic algorithms in concept analysis , in Lecture Notes In Computer Science. Formal Concept Analysis, Vol. 5986 , eds Hutchison D., Kanade T., Kittler J., Kleinberg J. M., Mattern F., Mitchell J. C., et al. (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; ), 312–340. 10.1007/978-3-642-11928-6_22 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ganter B., Wille R. (1999). Formal Concept Analysis . Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 10.1007/978-3-642-59830-2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guttman L. (1944). A basis for scaling qualitative data . Am. Sociol. Rev . 9 :139 10.2307/2086306 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hogg R. V., Mckean J. W., Craig A. T. (2013). Introduction to Mathematical Statistics, 7th Edn . Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hughes G. E., Cresswell M. J. (1996). A New Introduction To Modal Logic . London; New York, NY: Routledge; 10.4324/9780203290644 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klein R. A., Ratliff K. A., Vianello M., Adams R. B., Bahník Š., Bernstein M. J., et al. (2014). Investigating variation in replicability . Soc. Psychol. 45 , 142–152. 10.1027/1864-9335/a000178 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krantz D. H., Luce D., Suppes P., Tversky A. (1971). Foundations of Measurement Volume I: Additive And Polynomial Representations . New York, NY; London: Academic Press; 10.1016/B978-0-12-425401-5.50011-8 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leavy P. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research . New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199811755.001.0001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maxwell S. E., Lau M. Y., Howard G. S. (2015). Is psychology suffering from a replication crisis? what does “failure to replicate” really mean? Am. Psychol. 70 , 487–498. 10.1037/a0039400 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miles M. B., Huberman A. M., Saldaña J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd Edn . Los Angeles, CA; London; New Delhi; Singapore; Washington, DC: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Open Science, Collaboration (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science . Science 349 :Aac4716. 10.1126/science.aac4716 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Popper K. (1935). Logik Der Forschung . Wien: Springer; 10.1007/978-3-7091-4177-9 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ragin C. (1987). The Comparative Method : Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies . Berkeley, CA: University Of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rihoux B., Ragin C. (2009). Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (Qca) And Related Techniques . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 10.4135/9781452226569 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scheunpflug A., Krogull S., Franz J. (2016). Understanding learning in world society: qualitative reconstructive research in global learning and learning for sustainability . Int. Journal Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 7 , 6–23. 10.18546/IJDEGL.07.3.02 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schurz G. (2008). Patterns of abduction . Synthese 164 , 201–234. 10.1007/s11229-007-9223-4 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shrout P. E., Rodgers J. L. (2018). Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: broadening perspectives from the replication crisis . Annu. Rev. Psychol . 69 , 487–510. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011845 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith P. (2020). An Introduction To Formal Logic . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781108328999 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Suppes P., Krantz D. H., Luce D., Tversky A. (1971). Foundations of Measurement Volume II: Geometrical, Threshold, and Probabilistic Representations . New York, NY; London: Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tooley M. (Ed.). (1999). Necessity and Possibility. The Metaphysics of Modality . New York, NY; London: Garland Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Trafimow D. (2018). An a priori solution to the replication crisis . Philos. Psychol . 31 , 1188–1214. 10.1080/09515089.2018.1490707 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Watanabe S. (2018). Mathematical Foundations of Bayesian Statistics. CRC Monographs On Statistics And Applied Probability . Boca Raton, FL: Chapman And Hall. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wiggins B. J., Chrisopherson C. D. (2019). The replication crisis in psychology: an overview for theoretical and philosophical psychology . J. Theor. Philos. Psychol. 39 , 202–217. 10.1037/teo0000137 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Dr Deborah Gabriel

Inductive and deductive approaches to research

The main difference between inductive and deductive approaches to research is that whilst a deductive approach is aimed and testing theory, an inductive approach is concerned with the generation of new theory emerging from the data.

A deductive approach usually begins with a hypothesis, whilst an inductive approach will usually use research questions to narrow the scope of the study.

For deductive approaches the emphasis is generally on causality, whilst for inductive approaches the aim is usually focused on exploring new phenomena or looking at previously researched phenomena from a different perspective.

Inductive approaches are generally associated with qualitative research, whilst deductive approaches are more commonly associated with quantitative research. However, there are no set rules and some qualitative studies may have a deductive orientation.

One specific inductive approach that is frequently referred to in research literature is grounded theory, pioneered by Glaser and Strauss.

This approach necessitates the researcher beginning with a completely open mind without any preconceived ideas of what will be found. The aim is to generate a new theory based on the data.

Once the data analysis has been completed the researcher must examine existing theories in order to position their new theory within the discipline.

Grounded theory is not an approach to be used lightly. It requires extensive and repeated sifting through the data and analysing and re-analysing multiple times in order to identify new theory. It is an approach best suited to research projects where there the phenomena to be investigated has not been previously explored.

The most important point to bear in mind when considering whether to use an inductive or deductive approach is firstly the purpose of your research; and secondly the methods that are best suited to either test a hypothesis, explore a new or emerging area within the discipline, or to answer specific research questions.

Citing This Article

Gabriel, D. (2013). Inductive and deductive approaches to research. Accessed on ‘date’ from https://deborahgabriel.com/2013/03/17/inductive-and-deductive-approaches-to-research/

Gabriel, D., 2013. Inductive and deductive approaches to research. Accessed on ‘date’ from https://deborahgabriel.com/2013/03/17/inductive-and-deductive-approaches-to-research/

You May Also Like

How to write a literature review

Whether you are writing a 2000-word literature review for an undergraduate dissertation or something closer to 10,000-words for a PhD thesis, the process is the same.

Using Conceptual Frameworks in Qualitative Research

I recently delivered this presentation to final year undergraduate students about to embark on their dissertation projects.

Qualitative data analysis

The most important task that you will undertake in your PhD research project is the analysis of data. The integrity and rigour of your research is utterly dependent on getting the analysis right and it will be intensely scrutinised by the external examiners.

200 thoughts on “ Inductive and deductive approaches to research ”

- Pingback: Methods and methodology | Deborah Gabriel

- Pingback: PhD research: qualitative data analysis | Deborah Gabriel

Hi, yes the explanation was helpful because it was simple to read and pretty much, straight to the point. It has given me a brief understanding for what I needs. Thanks — Chantal

It was very supportive for me!! thank you!!

thank you so much for the information. it was simple to read and also brief concise and straight to the point. thank you.

Deborah, thanks for this elaboration. but I am asking is it possible to conduct a deductive inclined research and also generate a theory, or add to the theory. I have been asked by my supervisor whether I am just testing hypothesi or my aim is to contribute/generate a theory. my studies is more of a quantitative nature. Thanks

Deductive research is more aimed towards testing a hypothesis and therefore is an approach more suited to working with quantitative data. The process normally involves reproducing a previous study and seeing if the same results are produced. This does not lend itself to generating new theories since that is not the object of the research. Between inductive and deductive approaches there is also a third approach which I will write a post on shortly – abdductive.

Dear Deborah, it has been very long time since you posted this article. However, I can testify that it is very helpful for a novis reseracher like me.

Ms. Deborah, thank you for given info, but i was in confusion reg, differences between deductive, inductive, abductive and (new one) Hypothetico-deductive approaches. Can it be possible to email the differences, its applications, tools used and scientific nature, to build a theory using quantitative survey method. My email Id is: [email protected] Iam writing my PhD thesis based on this . it is part of my 3 chapter. Thanking you awaiting for your mail soon.

Hi Madhu. As a PhD student you need to take the time to read the appropriate literature on research approaches and attend workshops/conferences to better understand methodology. You cannot take short cuts by by asking someone (me) to simply provide you with ready answers to your queries – especially when I do not have the time to do so!

Great saying…every student at every level, should be critical analysts and critical thinkers.

Thank u.. but there is a little mistake which is deductive approach deals with qualitative and inductive appoech deals with quantitative

No – you have it the wrong way round – I suggest you read the article again and also engage in wider reading on research methods to gain a deeper understanding.

A clear cut concept with example.

Deborah I appreciate so much in this article…I got what I am looking for… thanks for your contribution.

Thanks so much

It is simple, easy to differentiate and understandable.

Thank u for the information, it really helps me.

Exactly, your work is simple and clear, that there are two research approaches, Inductive and deductive.Qualitative and Quantative approaches You gave clear differences in a balance, simple to understand, I suppose you are a teacher by profession. This is how we share knowledge,and you become more knowledgable

Thank you Lambawi, I am glad that these posts are proving useful. I will endeavour to add some more in the coming weeks!

This has been helpful. thanks for posting

Thank you very much for sharing knowledge with me. It really much helpful while preparing my college exam. Thank –:)

Thank you ever so much for making it simple and easily understandable. Would love to see more posts.

Best wishes

The explanation is simple and easy to understand it has helped to a lot thank you

very helpful and explained simply. thanks

Explanation is simple…. it was a great help for my exam preparation.

Excellent presentation please!

Very helpful information and a clear, simple explanation. Thank you

Thanks; this has been helpful in preparation for my forthcoming exams

This is fantastic, I have greatly beneffitted from this straight forward illustration

Thanks…i will benifited to read this

Thanks for your help. Keep it like that so that will be our guide towards our destinations.

Thank-you for your academic insights.

Thank you for your clarification. Well understood.

Hi, I had a question would you call process tracing technique an inductive or deductive approach? or maybe both? Hope you can help me with the same.

Hi Achin. Process tracing is a qualitative analytical tool and therefore inductive rather than deductive, since its purpose is to identify new phenomena. You might find this journal article useful:

http://www.ukcds.org.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/Understanding-Process-Tracing.pdf

Preparing for my Research Methods exams and I'm grateful for your explanations. This is a full lecture made simple. Thank you very much.

I am very thankful for this information, madam you are just good. If you are believer, allow me to say, May God bless you with more knowledge and good health.

Hi Rasol, glad that the post was useful and – yes – I am a believer so thank you for the blessing!

Dear Deborah

I am currently doing Btech in forensic with Unisa would you be so kind and help with this question below and may I use your services while Iam doing this degree Please

Hi I have question that goes like these "If the reseacher wanted to conduct reseach in a specific context to see whether it supports an establisblished theory" the reseacher would be conducting

1. case study

2. deductive research

3. exploratory resarch

4. inductive methods

please help me to choose the right one

Yours Faithfully

Baba Temba