An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.12(6); 2020 Jun

Social Media Use and Its Connection to Mental Health: A Systematic Review

Fazida karim.

1 Psychology, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences and Psychology, Fairfield, USA

2 Business & Management, University Sultan Zainal Abidin, Terengganu, MYS

Azeezat A Oyewande

3 Family Medicine, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences and Psychology, Fairfield, USA

4 Family Medicine, Lagos State Health Service Commission/Alimosho General Hospital, Lagos, NGA

Lamis F Abdalla

5 Internal Medicine, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences and Psychology, Fairfield, USA

Reem Chaudhry Ehsanullah

Safeera khan.

Social media are responsible for aggravating mental health problems. This systematic study summarizes the effects of social network usage on mental health. Fifty papers were shortlisted from google scholar databases, and after the application of various inclusion and exclusion criteria, 16 papers were chosen and all papers were evaluated for quality. Eight papers were cross-sectional studies, three were longitudinal studies, two were qualitative studies, and others were systematic reviews. Findings were classified into two outcomes of mental health: anxiety and depression. Social media activity such as time spent to have a positive effect on the mental health domain. However, due to the cross-sectional design and methodological limitations of sampling, there are considerable differences. The structure of social media influences on mental health needs to be further analyzed through qualitative research and vertical cohort studies.

Introduction and background

Human beings are social creatures that require the companionship of others to make progress in life. Thus, being socially connected with other people can relieve stress, anxiety, and sadness, but lack of social connection can pose serious risks to mental health [ 1 ].

Social media

Social media has recently become part of people's daily activities; many of them spend hours each day on Messenger, Instagram, Facebook, and other popular social media. Thus, many researchers and scholars study the impact of social media and applications on various aspects of people’s lives [ 2 ]. Moreover, the number of social media users worldwide in 2019 is 3.484 billion, up 9% year-on-year [ 3 - 5 ]. A statistic in Figure 1 shows the gender distribution of social media audiences worldwide as of January 2020, sorted by platform. It was found that only 38% of Twitter users were male but 61% were using Snapchat. In contrast, females were more likely to use LinkedIn and Facebook. There is no denying that social media has now become an important part of many people's lives. Social media has many positive and enjoyable benefits, but it can also lead to mental health problems. Previous research found that age did not have an effect but gender did; females were much more likely to experience mental health than males [ 6 , 7 ].

Impact on mental health

Mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which people understand their abilities, solve everyday life problems, work well, and make a significant contribution to the lives of their communities [ 8 ]. There is debated presently going on regarding the benefits and negative impacts of social media on mental health [ 9 , 10 ]. Social networking is a crucial element in protecting our mental health. Both the quantity and quality of social relationships affect mental health, health behavior, physical health, and mortality risk [ 9 ]. The Displaced Behavior Theory may help explain why social media shows a connection with mental health. According to the theory, people who spend more time in sedentary behaviors such as social media use have less time for face-to-face social interaction, both of which have been proven to be protective against mental disorders [ 11 , 12 ]. On the other hand, social theories found how social media use affects mental health by influencing how people view, maintain, and interact with their social network [ 13 ]. A number of studies have been conducted on the impacts of social media, and it has been indicated that the prolonged use of social media platforms such as Facebook may be related to negative signs and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress [ 10 - 15 ]. Furthermore, social media can create a lot of pressure to create the stereotype that others want to see and also being as popular as others.

The need for a systematic review

Systematic studies can quantitatively and qualitatively identify, aggregate, and evaluate all accessible data to generate a warm and accurate response to the research questions involved [ 4 ]. In addition, many existing systematic studies related to mental health studies have been conducted worldwide. However, only a limited number of studies are integrated with social media and conducted in the context of social science because the available literature heavily focused on medical science [ 6 ]. Because social media is a relatively new phenomenon, the potential links between their use and mental health have not been widely investigated.

This paper attempt to systematically review all the relevant literature with the aim of filling the gap by examining social media impact on mental health, which is sedentary behavior, which, if in excess, raises the risk of health problems [ 7 , 9 , 12 ]. This study is important because it provides information on the extent of the focus of peer review literature, which can assist the researchers in delivering a prospect with the aim of understanding the future attention related to climate change strategies that require scholarly attention. This study is very useful because it provides information on the extent to which peer review literature can assist researchers in presenting prospects with a view to understanding future concerns related to mental health strategies that require scientific attention. The development of the current systematic review is based on the main research question: how does social media affect mental health?

Research strategy

The research was conducted to identify studies analyzing the role of social media on mental health. Google Scholar was used as our main database to find the relevant articles. Keywords that were used for the search were: (1) “social media”, (2) “mental health”, (3) “social media” AND “mental health”, (4) “social networking” AND “mental health”, and (5) “social networking” OR “social media” AND “mental health” (Table 1 ).

Out of the results in Table 1 , a total of 50 articles relevant to the research question were selected. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, duplicate papers were removed, and, finally, a total of 28 articles were selected for review (Figure 2 ).

PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed, full-text research papers from the past five years were included in the review. All selected articles were in English language and any non-peer-reviewed and duplicate papers were excluded from finally selected articles.

Of the 16 selected research papers, there were a research focus on adults, gender, and preadolescents [ 10 - 19 ]. In the design, there were qualitative and quantitative studies [ 15 , 16 ]. There were three systematic reviews and one thematic analysis that explored the better or worse of using social media among adolescents [ 20 - 23 ]. In addition, eight were cross-sectional studies and only three were longitudinal studies [ 24 - 29 ].The meta-analyses included studies published beyond the last five years in this population. Table 2 presents a selection of studies from the review.

IGU, internet gaming disorder; PSMU, problematic social media use

This study has attempted to systematically analyze the existing literature on the effect of social media use on mental health. Although the results of the study were not completely consistent, this review found a general association between social media use and mental health issues. Although there is positive evidence for a link between social media and mental health, the opposite has been reported.

For example, a previous study found no relationship between the amount of time spent on social media and depression or between social media-related activities, such as the number of online friends and the number of “selfies”, and depression [ 29 ]. Similarly, Neira and Barber found that while higher investment in social media (e.g. active social media use) predicted adolescents’ depressive symptoms, no relationship was found between the frequency of social media use and depressed mood [ 28 ].

In the 16 studies, anxiety and depression were the most commonly measured outcome. The prominent risk factors for anxiety and depression emerging from this study comprised time spent, activity, and addiction to social media. In today's world, anxiety is one of the basic mental health problems. People liked and commented on their uploaded photos and videos. In today's age, everyone is immune to the social media context. Some teens experience anxiety from social media related to fear of loss, which causes teens to try to respond and check all their friends' messages and messages on a regular basis.

On the contrary, depression is one of the unintended significances of unnecessary use of social media. In detail, depression is limited not only to Facebooks but also to other social networking sites, which causes psychological problems. A new study found that individuals who are involved in social media, games, texts, mobile phones, etc. are more likely to experience depression.

The previous study found a 70% increase in self-reported depressive symptoms among the group using social media. The other social media influence that causes depression is sexual fun [ 12 ]. The intimacy fun happens when social media promotes putting on a facade that highlights the fun and excitement but does not tell us much about where we are struggling in our daily lives at a deeper level [ 28 ]. Another study revealed that depression and time spent on Facebook by adolescents are positively correlated [ 22 ]. More importantly, symptoms of major depression have been found among the individuals who spent most of their time in online activities and performing image management on social networking sites [ 14 ].

Another study assessed gender differences in associations between social media use and mental health. Females were found to be more addicted to social media as compared with males [ 26 ]. Passive activity in social media use such as reading posts is more strongly associated with depression than doing active use like making posts [ 23 ]. Other important findings of this review suggest that other factors such as interpersonal trust and family functioning may have a greater influence on the symptoms of depression than the frequency of social media use [ 28 , 29 ].

Limitation and suggestion

The limitations and suggestions were identified by the evidence involved in the study and review process. Previously, 7 of the 16 studies were cross-sectional and slightly failed to determine the causal relationship between the variables of interest. Given the evidence from cross-sectional studies, it is not possible to conclude that the use of social networks causes mental health problems. Only three longitudinal studies examined the causal relationship between social media and mental health, which is hard to examine if the mental health problem appeared more pronounced in those who use social media more compared with those who use it less or do not use at all [ 19 , 20 , 24 ]. Next, despite the fact that the proposed relationship between social media and mental health is complex, a few studies investigated mediating factors that may contribute or exacerbate this relationship. Further investigations are required to clarify the underlying factors that help examine why social media has a negative impact on some peoples’ mental health, whereas it has no or positive effect on others’ mental health.

Conclusions

Social media is a new study that is rapidly growing and gaining popularity. Thus, there are many unexplored and unexpected constructive answers associated with it. Lately, studies have found that using social media platforms can have a detrimental effect on the psychological health of its users. However, the extent to which the use of social media impacts the public is yet to be determined. This systematic review has found that social media envy can affect the level of anxiety and depression in individuals. In addition, other potential causes of anxiety and depression have been identified, which require further exploration.

The importance of such findings is to facilitate further research on social media and mental health. In addition, the information obtained from this study can be helpful not only to medical professionals but also to social science research. The findings of this study suggest that potential causal factors from social media can be considered when cooperating with patients who have been diagnosed with anxiety or depression. Also, if the results from this study were used to explore more relationships with another construct, this could potentially enhance the findings to reduce anxiety and depression rates and prevent suicide rates from occurring.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Mental health and the pandemic: What U.S. surveys have found

The coronavirus pandemic has been associated with worsening mental health among people in the United States and around the world . In the U.S, the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020 caused widespread lockdowns and disruptions in daily life while triggering a short but severe economic recession that resulted in widespread unemployment. Three years later, Americans have largely returned to normal activities, but challenges with mental health remain.

Here’s a look at what surveys by Pew Research Center and other organizations have found about Americans’ mental health during the pandemic. These findings reflect a snapshot in time, and it’s possible that attitudes and experiences may have changed since these surveys were fielded. It’s also important to note that concerns about mental health were common in the U.S. long before the arrival of COVID-19 .

Three years into the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States , Pew Research Center published this collection of survey findings about Americans’ challenges with mental health during the pandemic. All findings are previously published. Methodological information about each survey cited here, including the sample sizes and field dates, can be found by following the links in the text.

The research behind the first item in this analysis, examining Americans’ experiences with psychological distress, benefited from the advice and counsel of the COVID-19 and mental health measurement group at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

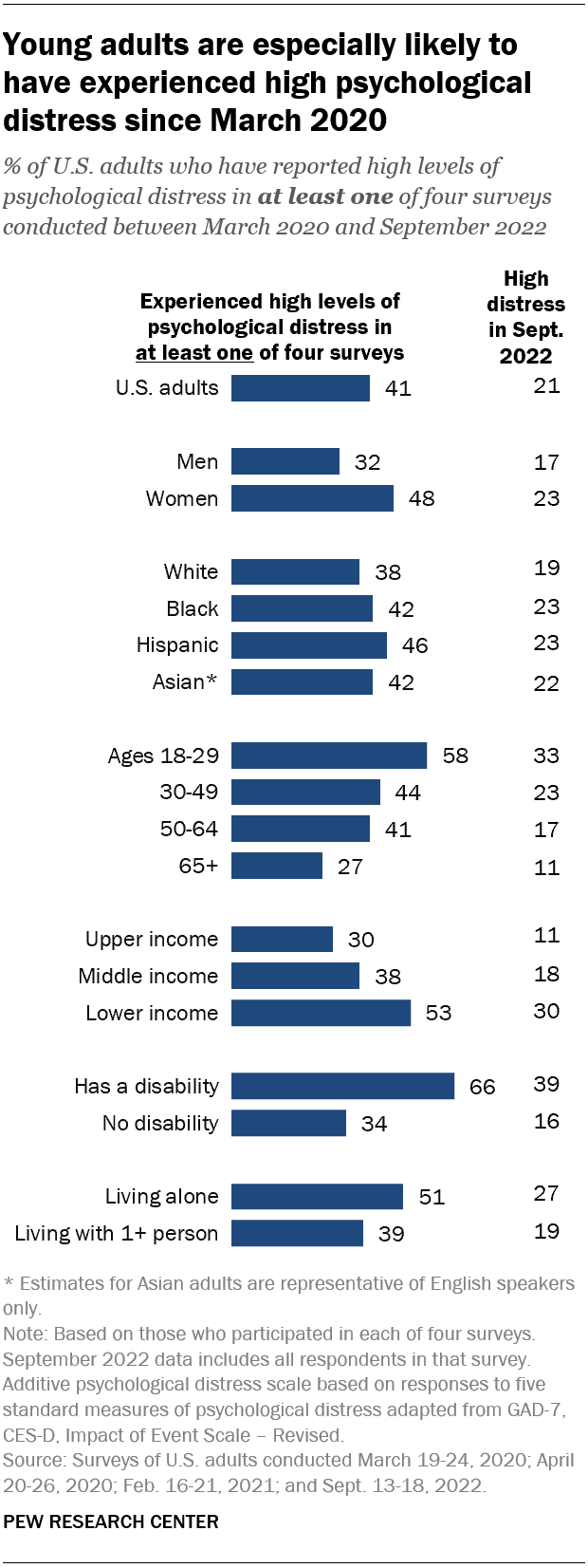

At least four-in-ten U.S. adults (41%) have experienced high levels of psychological distress at some point during the pandemic, according to four Pew Research Center surveys conducted between March 2020 and September 2022.

Young adults are especially likely to have faced high levels of psychological distress since the COVID-19 outbreak began: 58% of Americans ages 18 to 29 fall into this category, based on their answers in at least one of these four surveys.

Women are much more likely than men to have experienced high psychological distress (48% vs. 32%), as are people in lower-income households (53%) when compared with those in middle-income (38%) or upper-income (30%) households.

In addition, roughly two-thirds (66%) of adults who have a disability or health condition that prevents them from participating fully in work, school, housework or other activities have experienced a high level of distress during the pandemic.

The Center measured Americans’ psychological distress by asking them a series of five questions on subjects including loneliness, anxiety and trouble sleeping in the past week. The questions are not a clinical measure, nor a diagnostic tool. Instead, they describe people’s emotional experiences during the week before being surveyed.

While these questions did not ask specifically about the pandemic, a sixth question did, inquiring whether respondents had “had physical reactions, such as sweating, trouble breathing, nausea, or a pounding heart” when thinking about their experience with the coronavirus outbreak. In September 2022, the most recent time this question was asked, 14% of Americans said they’d experienced this at least some or a little of the time in the past seven days.

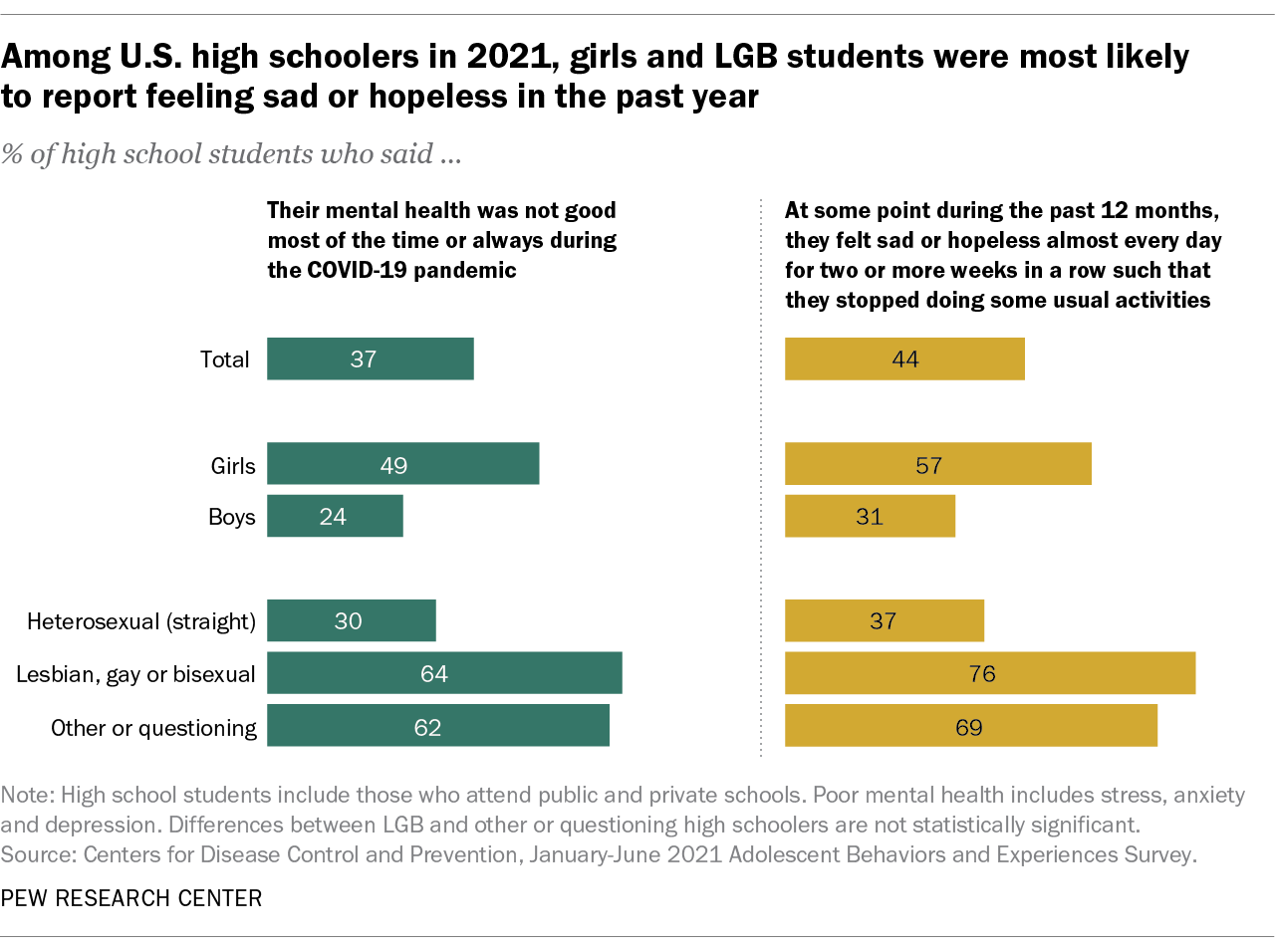

More than a third of high school students have reported mental health challenges during the pandemic. In a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from January to June 2021, 37% of students at public and private high schools said their mental health was not good most or all of the time during the pandemic. That included roughly half of girls (49%) and about a quarter of boys (24%).

In the same survey, an even larger share of high school students (44%) said that at some point during the previous 12 months, they had felt sad or hopeless almost every day for two or more weeks in a row – to the point where they had stopped doing some usual activities. Roughly six-in-ten high school girls (57%) said this, as did 31% of boys.

On both questions, high school students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, other or questioning were far more likely than heterosexual students to report negative experiences related to their mental health.

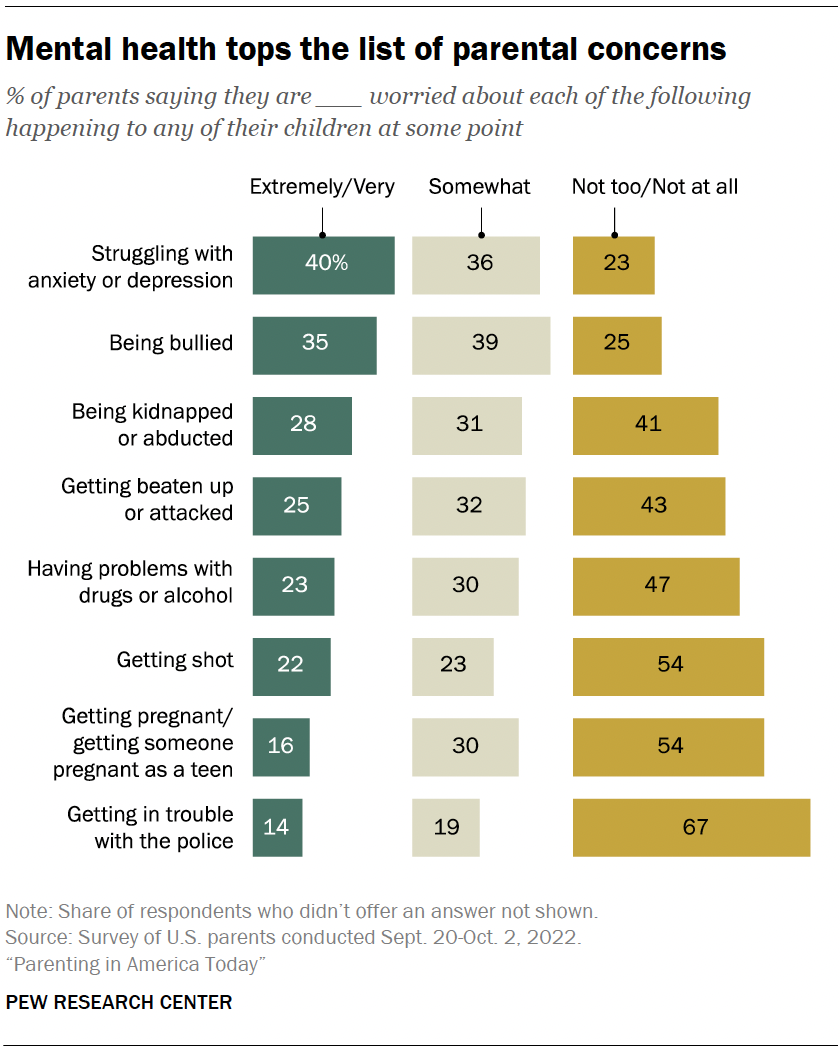

Mental health tops the list of worries that U.S. parents express about their kids’ well-being, according to a fall 2022 Pew Research Center survey of parents with children younger than 18. In that survey, four-in-ten U.S. parents said they’re extremely or very worried about their children struggling with anxiety or depression. That was greater than the share of parents who expressed high levels of concern over seven other dangers asked about.

While the fall 2022 survey was fielded amid the coronavirus outbreak, it did not ask about parental worries in the specific context of the pandemic. It’s also important to note that parental concerns about their kids struggling with anxiety and depression were common long before the pandemic, too . (Due to changes in question wording, the results from the fall 2022 survey of parents are not directly comparable with those from an earlier Center survey of parents, conducted in 2015.)

Among parents of teenagers, roughly three-in-ten (28%) are extremely or very worried that their teen’s use of social media could lead to problems with anxiety or depression, according to a spring 2022 survey of parents with children ages 13 to 17 . Parents of teen girls were more likely than parents of teen boys to be extremely or very worried on this front (32% vs. 24%). And Hispanic parents (37%) were more likely than those who are Black or White (26% each) to express a great deal of concern about this. (There were not enough Asian American parents in the sample to analyze separately. This survey also did not ask about parental concerns specifically in the context of the pandemic.)

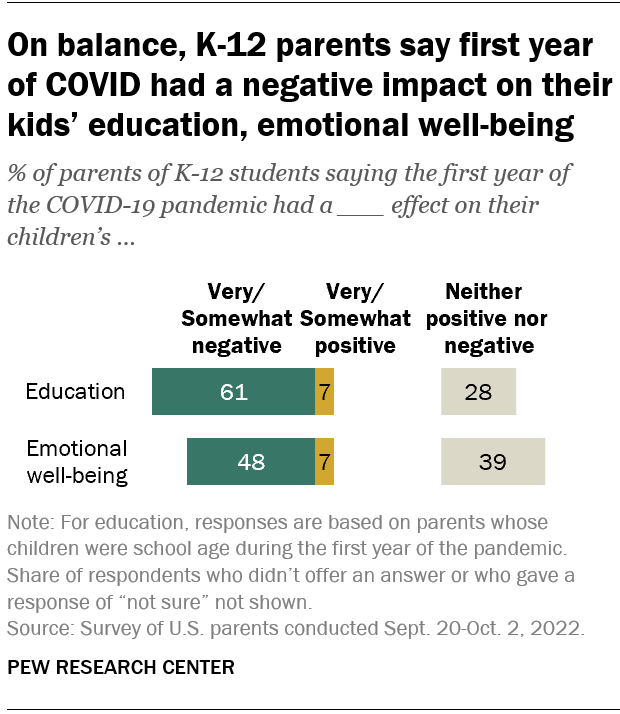

Looking back, many K-12 parents say the first year of the coronavirus pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s emotional health. In a fall 2022 survey of parents with K-12 children , 48% said the first year of the pandemic had a very or somewhat negative impact on their children’s emotional well-being, while 39% said it had neither a positive nor negative effect. A small share of parents (7%) said the first year of the pandemic had a very or somewhat positive effect in this regard.

White parents and those from upper-income households were especially likely to say the first year of the pandemic had a negative emotional impact on their K-12 children.

While around half of K-12 parents said the first year of the pandemic had a negative emotional impact on their kids, a larger share (61%) said it had a negative effect on their children’s education.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Happiness & Life Satisfaction

- Medicine & Health

- Teens & Youth

John Gramlich is an associate director at Pew Research Center .

How Americans View the Coronavirus, COVID-19 Vaccines Amid Declining Levels of Concern

Online religious services appeal to many americans, but going in person remains more popular, about a third of u.s. workers who can work from home now do so all the time, how the pandemic has affected attendance at u.s. religious services, economy remains the public’s top policy priority; covid-19 concerns decline again, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

- Open access

- Published: 20 September 2022

Factors that influence mental health of university and college students in the UK: a systematic review

- Fiona Campbell 1 ,

- Lindsay Blank 1 ,

- Anna Cantrell 1 ,

- Susan Baxter 1 ,

- Christopher Blackmore 1 ,

- Jan Dixon 1 &

- Elizabeth Goyder 1

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 1778 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

105k Accesses

52 Citations

89 Altmetric

Metrics details

Worsening mental health of students in higher education is a public policy concern and the impact of measures to reduce transmission of COVID-19 has heightened awareness of this issue. Preventing poor mental health and supporting positive mental wellbeing needs to be based on an evidence informed understanding what factors influence the mental health of students.

To identify factors associated with mental health of students in higher education.

We undertook a systematic review of observational studies that measured factors associated with student mental wellbeing and poor mental health. Extensive searches were undertaken across five databases. We included studies undertaken in the UK and published within the last decade (2010–2020). Due to heterogeneity of factors, and diversity of outcomes used to measure wellbeing and poor mental health the findings were analysed and described narratively.

We included 31 studies, most of which were cross sectional in design. Those factors most strongly and consistently associated with increased risk of developing poor mental health included students with experiences of trauma in childhood, those that identify as LGBTQ and students with autism. Factors that promote wellbeing include developing strong and supportive social networks. Students who are prepared and able to adjust to the changes that moving into higher education presents also experience better mental health. Some behaviours that are associated with poor mental health include lack of engagement both with learning and leisure activities and poor mental health literacy.

Improved knowledge of factors associated with poor mental health and also those that increase mental wellbeing can provide a foundation for designing strategies and specific interventions that can prevent poor mental health and ensuring targeted support is available for students at increased risk.

Peer Review reports

Poor mental health of students in further and higher education is an increasing concern for public health and policy [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. A 2020 Insight Network survey of students from 10 universities suggests that “1 in 5 students has a current mental health diagnosis” and that “almost half have experienced a serious psychological issue for which they felt they needed professional help”—an increase from 1 in 3 in the same survey conducted in 2018 [ 5 ]. A review of 105 Further Education (FE) colleges in England found that over a three-year period, 85% of colleges reported an increase in mental health difficulties [ 1 ]. Depression and anxiety were both prevalent and widespread in students; all colleges reported students experiencing depression and 99% reported students experiencing severe anxiety [ 5 , 6 ]. A UK cohort study found that levels of psychological distress increase on entering university [ 7 ], and recent evidence suggests that the prevalence of mental health problems among university students, including self-harm and suicide, is rising, [ 3 , 4 ] with increases in demand for services to support student mental health and reports of some universities finding a doubling of the number of students accessing support [ 8 ]. These common mental health difficulties clearly present considerable threat to the mental health and wellbeing of students but their impact also has educational, social and economic consequences such as academic underperformance and increased risk of dropping out of university [ 9 , 10 ].

Policy changes may have had an influence on the student experience, and on the levels of mental health problems seen in the student population; the biggest change has arguably been the move to widen higher education participation and to enable a more diverse demographic to access University education. The trend for widening participation has been continually rising since the late 1960s [ 11 ] but gained impetus in the 2000s through the work of the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). Macaskill (2013) [ 12 ] suggests that the increased access to higher education will have resulted in more students attending university from minority groups and less affluent backgrounds, meaning that more students may be vulnerable to mental health problems, and these students may also experience greater challenges in making the transition to higher education.

Another significant change has been the introduction of tuition fees in 1998, which required students to self fund up to £1,000 per academic year. Since then, tuition fees have increased significantly for many students. With the abolition of maintenance grants, around 96% of government support for students now comes in the form of student loans [ 13 ]. It is estimated that in 2017, UK students were graduating with average debts of £50,000, and this figure was even higher for the poorest students [ 13 ]. There is a clear association between a student’s mental health and financial well-being [ 14 ], with “increased financial concern being consistently associated with worse health” [ 15 ].

The extent to which the increase in poor mental health is also being seen amongst non-students of a similar age is not well understood and warrants further study. However, the increase in poor mental health specifically within students in higher education highlights a need to understand what the risk factors are and what might be done within these settings to ensure young people are learning and developing and transitioning into adulthood in environments that promote mental wellbeing.

Commencing higher education represents a key transition point in a young person’s life. It is a stage often accompanied by significant change combined with high expectations of high expectations from students of what university life will be like, and also high expectations from themselves and others around their own academic performance. Relevant factors include moving away from home, learning to live independently, developing new social networks, adjusting to new ways of learning, and now also dealing with the additional greater financial burdens that students now face.

The recent global COVID-19 pandemic has had considerable impact on mental health across society, and there is concern that younger people (ages 18–25) have been particularly affected. Data from Canada [ 16 ] indicate that among survey respondents, “almost two-thirds (64%) of those aged 15 to 24 reported a negative impact on their mental health, while just over one-third (35%) of those aged 65 and older reported a negative impact on their mental health since physical distancing began” (ibid, p.4). This suggests that older adults are more prepared for the kind of social isolation which has been brought about through the response to COVID-19, whereas young adults have found this more difficult to cope with. UK data from the National Union of Students reports that for over half of UK students, their mental health is worse than before the pandemic [ 17 ]. Before COVID-19, students were already reporting increasing levels of mental health problems [ 2 ], but the COVID-19 pandemic has added a layer of “chronic and unpredictable” stress, creating the perfect conditions for a mental health crisis [ 18 ]. An example of this is the referrals (both urgent and routine) of young people with eating disorders for treatment in the NHS which almost doubled in number from 2019 to 2020 [ 19 ]. The travel restrictions enforced during the pandemic have also impacted on student mental health, particularly for international students who may have been unable to commence studies or go home to see friends and family during holidays [ 20 ].

With the increasing awareness and concern in the higher education sector and national bodies regarding student mental health has come increasing focus on how to respond. Various guidelines and best practice have been developed, e.g. ‘Degrees of Disturbance’ [ 21 ], ‘Good Practice Guide on Responding to Student Mental Health Issues: Duty of Care Responsibilities for Student Services in Higher Education’ [ 22 ] and the recent ‘The University Mental Health Charter’ [ 2 ]. Universities UK produced a Good Practice Guide in 2015 called “Student mental wellbeing in higher education” [ 23 ]. An increasing number of initiatives have emerged that are either student-led or jointly developed with students, and which reflect the increasing emphasis students and student bodies place on mental health and well-being and the increased demand for mental health support: Examples include: Nightline— www.nightline.ac.uk , Students Against Depression— www.studentsagainstdepression.org , Student Minds— www.studentminds.org.uk/student-minds-and-mental-wealth.html and The Alliance for Student-Led Wellbeing— www.alliancestudentwellbeing.weebly.com/ .

Although requests for professional support have increased substantially [ 24 ] only a third of students with mental health problems seek support from counselling services in the UK [ 12 ]. Many students encounter barriers to seeking help such as stigma or lack of awareness of services [ 25 ], and without formal support or intervention, there is a risk of deterioration. FE colleges and universities have identified the need to move beyond traditional forms of support and provide alternative, more accessible interventions aimed at improving mental health and well-being. Higher education institutions have a unique opportunity to identify, prevent, and treat mental health problems because they provide support in multiple aspects of students’ lives including academic studies, recreational activities, pastoral and counselling services, and residential accommodation.

In order to develop services that better meet the needs of students and design environments that are supportive of developing mental wellbeing it is necessary to explore and better understand the factors that lead to poor mental health in students.

Research objectives

The overall aim of this review was to identify, appraise and synthesise existing research evidence that explores the aetiology of poor mental health and mental wellbeing amongst students in tertiary level education. We aimed to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms that lead to poor mental health amongst tertiary level students and, in so doing, make evidence-based recommendations for policy, practice and future research priorities. Specific objectives in line with the project brief were to:

To co-produce with stakeholders a conceptual framework for exploring the factors associated with poorer mental health in students in tertiary settings. The factors may be both predictive, identifying students at risk, or causal, explaining why they are at risk. They may also be protective, promoting mental wellbeing.

To conduct a review drawing on qualitative studies, observational studies and surveys to explore the aetiology of poor mental health in students in university and college settings and identify factors which promote mental wellbeing amongst students.

To identify evidence-based recommendations for policy, service provision and future research that focus on prevention and early identification of poor mental health

Methodology

Identification of relevant evidence.

The following inclusion criteria were used to guide the development of the search strategy and the selection of studies.

We included students from a variety of further education settings (16 yrs + or 18 yrs + , including mature students, international students, distance learning students, students at specific transition points).

Universities and colleges in the UK. We were also interested in the context prior to the beginning of tertiary education, including factors during transition from home and secondary education or existing employment to tertiary education.

Any factor shown to be associated with mental health of students in tertiary level education. This included clinical indicators such as diagnosis and treatment and/or referral for depression and anxiety. Self-reported measures of wellbeing, happiness, stress, anxiety and depression were included. We did not include measures of academic achievement or engagement with learning as indicators of mental wellbeing.

Study design

We included cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that looked at factors associated with mental health outcomes in Table 5 .

Data extraction and quality appraisal

We extracted and tabulated key data from the included papers. Data extraction was undertaken by one reviewer, with a 10% sample checked for accuracy and consistency The quality of the included studies were evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [ 26 ] and the findings of the quality appraisal used in weighting the strength of associations and also identifying gaps for future high quality research.

Involvement of stakeholders

We recruited students, ex-students and parents of students to a public involvement group which met on-line three times during the process of the review and following the completion of the review. During a workshop meeting we asked for members of the group to draw on their personal experiences to suggest factors which were not mentioned in the literature.

Methods of synthesis

We undertook a narrative synthesis [ 27 ] due to the heterogeneity in the exposures and outcomes that were measured across the studies. Data showing the direction of effects and the strength of the association (correlation coefficients) were recorded and tabulated to aid comparison between studies.

Search strategy

Searches were conducted in the following electronic databases: Medline, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), International Bibliography of Social Sciences (IBSS), Science,PsycINFO and Science and Social Sciences Ciatation Indexes. Additional searches of grey literature, and reference lists of included studies were also undertaken.

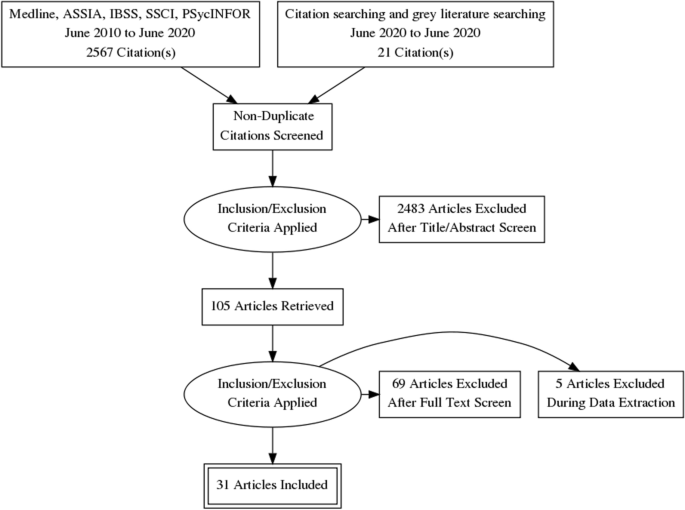

The search strategy combined a number of terms relating to students and mental health and risk factors. The search terms included both subject (MeSH) and free-text searches. The searches were limited to papers about humans in English, published from 2010 to June 2020. The flow of studies through the review process is summarised in Fig. 1 .

Flow diagram

The full search strategy for Medline is provided in Appendix 1 .

Thirty-one quantitative, observational studies (39 papers) met the inclusion criteria. The total number of students that participated in the quantitative studies was 17,476, with studies ranging in size from 57 to 3706. Eighteen studies recruited student participants from only one university; five studies (10 publications) [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ] included seven or more universities. Six studies (7 publications) [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ] only recruited first year students, while the majority of studies recruited students from a range of year groups. Five studies [ 39 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ] recruited only, or mainly, psychology students which may impact on the generalisability of findings. A number of studies focused on students studying particular subjects including: nursing [ 46 ] medicine [ 47 ], business [ 48 ], sports science [ 49 ]. One study [ 50 ] recruited LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer/questioning) students, and one [ 51 ] recruited students who had attended hospital having self-harmed. In 27 of the studies, there were more female than male participants. The mean age of the participants ranged from 19 to 28 years. Ethnicity was not reported in 19 of the studies. Where ethnicity was reported, the proportion that were ‘white British’ ranged from 71 – 90%. See Table 1 for a summary of the characteristics of the included studies and the participants.

Design and quality appraisal of the included studies

The majority of included studies ( n = 22) were cross-sectional surveys. Nine studies (10 publications) [ 35 , 36 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 62 ] were longitudinal in design, recording survey data at different time points to explore changes in the variables being measured. The duration of time that these studies covered ranged from 19 weeks to 12 years. Most of the studies ( n = 22) only recruited participants from a single university. The use of one university setting and the large number of studies that recruited only psychology students weakens the wider applicability of the included studies.

Quantitative variables

Included studies ( n = 31) measured a wide range of variables and explored their association with poor mental health and wellbeing. These included individual level factors: age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity and a range of psychological variables. They also included factors that related to mental health variables (family history, personal history and mental health literacy), pre-university factors (childhood trauma and parenting behaviour. University level factors including social isolation, adjustment and engagement with learning. Their association was measured against different measures of positive mental health and poor mental health.

Measurement of association and the strength of that association has some limitations in addressing our research question. It cannot prove causality, and nor can it capture fully the complexity of the inter-relationship and compounding aspect of the variables. For example, the stress of adjustment may be manageable, until it is combined with feeling isolated and out of place. Measurement itself may also be misleading, only capturing what is measureable, and may miss variables that are important but not known. We included both qualitative and PPI input to identify missed but important variables.

The wide range of variables and different outcomes, with few studies measuring the same variable and outcomes, prevented meta-analyses of findings which are therefore described narratively.

The variables described were categorised during the analyses into the following categories:

Vulnerabilities – factors that are associated with poor mental health

Individual level factors including; age, ethnicity, gender and a range of psychological variables were all measured against different mental health outcomes including depression, anxiety, paranoia, and suicidal behaviour, self-harm, coping and emotional intelligence.

Six studies [ 40 , 42 , 47 , 50 , 60 , 63 ] examined a student’s ages and association with mental health. There was inconsistency in the study findings, with studies finding that age (21 or older) was associated with fewer depressive symptoms, lower likelihood of suicide ideation and attempt, self-harm, and positively associated with better coping skills and mental wellbeing. This finding was not however consistent across studies and the association was weak. Theoretical models that seek to explain this mechanism have suggested that older age groups may cope better due to emotion-regulation strategies improving with age [ 67 ]. However, those over 30 experienced greater financial stress than those aged 17-19 in another study [ 63 ].

Sexual orientation

Four studies [ 33 , 40 , 64 , 68 ] examined the association between poor mental health and sexual orientation status. In all of the studies LGBTQ students were at significantly greater risk of mental health problems including depression [ 40 ], anxiety [ 40 ], suicidal behaviour [ 33 , 40 , 64 ], self harm [ 33 , 40 , 64 ], use of mental health services [ 33 ] and low levels of wellbeing [ 68 ]. The risk of mental health problems in these students compared with heterosexual students, ranged from OR 1.4 to 4.5. This elevated risk may reflect the greater levels of isolation and discrimination commonly experienced by minority groups.

Nine studies [ 33 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 42 , 47 , 50 , 60 , 63 ] examined whether gender was associated mental health variables. Two studies [ 33 , 47 ] found that being female was statistically significantly associated with use of mental health services, having a current mental health problem, suicide risk, self harm [ 33 ] and depression [ 47 ]. The results were not consistent, with another study [ 60 ] finding the association was not significant. Three studies [ 39 , 40 , 42 ] that considered mediating variables such as adaptability and coping found no difference or very weak associations.

Two studies [ 47 , 60 ] examined the extent to which ethnicity was associated with mental health One study [ 47 ] reported that the risks of depression were significantly greater for those who categorised themselves as non-white (OR 8.36 p = 0.004). Non-white ethnicity was also associated with poorer mental health in another cross-sectional study [ 63 ]. There was no significant difference in the McIntyre et al. (2018) study [ 60 ]. The small number of participants from ethnic minority groups represented across the studies means that this data is very limited.

Family factors

Six studies [ 33 , 40 , 42 , 50 , 60 ] explored the association of a concept that related to a student’s experiences in childhood and before going to university. Three studies [ 40 , 50 , 60 ] explored the impact of ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) assessed using the same scale by Feletti (2009) [ 69 ] and another explored the impact of abuse in childhood [ 46 ]. Two studies examined the impact of attachment anxiety and avoidance [ 42 ], and parental acceptance [ 46 , 59 ]. The studies measured different mental health outcomes including; positive and negative affect, coping, suicide risk, suicide attempt, current mental health problem, use of mental health services, psychological adjustment, depression and anxiety.

The three studies that explored the impact of ACE’s all found a significant and positive relationship with poor mental health amongst university students. O’Neill et al. (2018) [ 50 ] in a longitudinal study ( n = 739) showed that there was in increased likelihood in self-harm and suicidal behaviours in those with either moderate or high levels of childhood adversities (OR:5.5 to 8.6) [ 50 ]. McIntyre et al. (2018) [ 60 ] ( n = 1135) also explored other dimensions of adversity including childhood trauma through multiple regression analysis with other predictive variables. They found that childhood trauma was significantly positively correlated with anxiety, depression and paranoia (ß = 0.18, 0.09, 0.18) though the association was not as strong as the correlation seen for loneliness (ß = 0.40) [ 60 ]. McLafferty et al. (2019) [ 40 ] explored the compounding impact of childhood adversity and negative parenting practices (over-control, overprotection and overindulgence) on poor mental health (depression OR 1.8, anxiety OR 2.1 suicidal behaviour OR 2.3, self-harm OR 2.0).

Gaan et al.’s (2019) survey of LGBTQ students ( n = 1567) found in a multivariate analyses that sexual abuse, other abuse from violence from someone close, and being female had the highest odds ratios for poor mental health and were significantly associated with all poor mental health outcomes [ 33 ].

While childhood trauma and past abuse poses a risk to mental health for all young people it may place additional stresses for students at university. Entry to university represents life stage where there is potential exposure to new and additional stressors, and the possibility that these students may become more isolated and find it more difficult to develop a sense of belonging. Students may be separated for the first time from protective friendships. However, the mechanisms that link childhood adversities and negative psychopathology, self-harm and suicidal behaviour are not clear [ 40 ]. McLafferty et al. (2019) also measured the ability to cope and these are not always impacted by childhood adversities [ 40 ]. They suggest that some children learn to cope and build resilience that may be beneficial.

McLafferty et al. (2019) [ 40 ] also studied parenting practices. Parental over-control and over-indulgence was also related to significantly poorer coping (OR -0.075 p < 0.05) and this was related to developing poorer coping scores (OR -0.21 p < 0.001) [ 40 ]. These parenting factors only became risk factors when stress levels were high for students at university. It should be noted that these studies used self-report, and responses regarding views of parenting may be subjective and open to interpretation. Lloyd et al.’s (2014) survey found significant positive correlations between perceived parental acceptance and students’ psychological adjustment, with paternal acceptance being the stronger predictor of adjustment.

Autistic students may display social communication and interaction deficits that can have negative emotional impacts. This may be particularly true during young adulthood, a period of increased social demands and expectations. Two studies [ 56 ] found that those with autism had a low but statistically significant association with poor social problem-solving skills and depression.

Mental health history

Three studies [ 47 , 51 , 68 ] investigated mental health variables and their impact on mental health of students in higher education. These included; a family history of mental illness and a personal history of mental illness.

Students with a family history or a personal history of mental illness appear to have a significantly greater risk of developing problems with mental health at university [ 47 ]. Mahadevan et al. (2010) [ 51 ] found that university students who self-harm have a significantly greater risk (OR 5.33) of having an eating disorder than a comparison group of young adults who self-harm but are not students.

Buffers – factors that are protective of mental wellbeing

Psychological factors.

Twelve studies [ 29 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 46 , 49 , 54 , 58 , 64 ] assessed the association of a range of psychological variables and different aspects of mental wellbeing and poor mental health. We categorised these into the following two categories: firstly, psychological variables measuring an individual’s response to change and stressors including adaptability, resilience, grit and emotional regulation [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 46 , 49 , 54 , 58 ] and secondly, those that measure self-esteem and body image [ 29 , 64 ].

The evidence from the eight included quantitative studies suggests that students with psychological strengths including; optimism, self-efficacy [ 70 ], resilience, grit [ 58 ], use of positive reappraisal [ 49 ], helpful coping strategies [ 42 ] and emotional intelligence [ 41 , 46 ] are more likely to experience greater mental wellbeing (see Table 2 for a description of the psychological variables measured). The positive association between these psychological strengths and mental well-being had a positive affect with associations ranging from r = 0.2–0.5 and OR1.27 [ 41 , 43 , 46 , 49 , 54 ] (low to moderate strength of association). The negative associations with depressive symptoms are also statistically significant but with a weaker association ( r = -0.2—0.3) [ 43 , 49 , 54 ].

Denovan (2017a) [ 43 ] in a longitudinal study found that the association between psychological strengths and positive mental wellbeing was not static and that not all the strengths remained statistically significant over time. The only factors that remained significant during the transition period were self-efficacy and optimism, remaining statistically significant as they started university and 6 months later.

Parental factors

Only one study [ 59 ] explored family factors associated with the development of psychological strengths that would equip young people as they managed the challenges and stressors encountered during the transition to higher education. Lloyd et al. (2014) [ 59 ] found that perceived maternal and paternal acceptance made significant and unique contributions to students’ psychological adjustment. Their research methods are limited by their reliance on retrospective measures and self-report measures of variables, and these results could be influenced by recall bias.

Two studies [ 29 , 64 ] considered the impact of how individuals view themselves on poor mental health. One study considered the impact of self-esteem and the association with non-accidental self-injury (NSSI) and suicide attempt amongst 734 university students. As rates of suicide and NSSI are higher amongst LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) students, the prevalence of low self-esteem was compared. There was a low but statistically significant association between low self-esteem and NSSI, though not for suicide attempt. A large survey, including participants from seven universities [ 42 ] compared depressive symptoms in students with marked body image concerns, reporting that the risk of depressive symptoms was greater (OR 2.93) than for those with lower levels of body image concerns.

Mental health literacy and help seeking behaviour

Two studies [ 48 , 68 ] investigated attitudes to mental illness, mental health literacy and help seeking for mental health problems.

University students who lack sufficient mental health literacy skills to be able to recognise problems or where there are attitudes that foster shame at admitting to having mental health problems can result in students not recognising problems and/or failing to seek professional help [ 48 , 68 ]. Gorcyznski et al. (2017) [ 68 ] found that women and those who had a history of previous mental health problems exhibited significantly higher levels of mental health literacy. Greater mental health literacy was associated with an increased likelihood that individuals would seek help for mental health problems. They found that many students find it hard to identify symptoms of mental health problems and that 42% of students are unaware of where to access available resources. Of those who expressed an intention to seek help for mental health problems, most expressed a preference for online resources, and seeking help from family and friends, rather than medical professionals such as GPs.

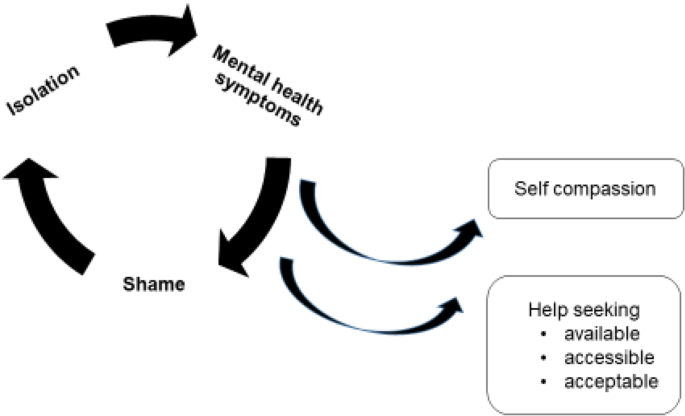

Kotera et al. (2019) [ 48 ] identified self-compassion as an explanatory variable, reducing social comparison, promoting self-acceptance and recognition that discomfort is an inevitable human experience. The study found a strong, significant correlation between self-compassion and mental health symptoms ( r = -0.6. p < 0.01).

There again appears to be a cycle of reinforcement, where poor mental health symptoms are felt to be a source of shame and become hidden, help is not sought, and further isolation ensues, leading to further deterioration in mental health. Factors that can interrupt the cycle are self-compassion, leading to more readiness to seek help (see Fig. 2 ).

Poor mental health – cycles of reinforcement

Social networks

Nine studies [ 33 , 38 , 41 , 46 , 51 , 54 , 60 , 64 , 65 ] examined the concepts of loneliness and social support and its association with mental health in university students. One study also included students at other Higher Education Institutions [ 46 ]. Eight of the studies were surveys, and one was a retrospective case control study to examine the differences between university students and age-matched young people (non-university students) who attended hospital following deliberate self-harm [ 51 ].

Included studies demonstrated considerable variation in how they measured the concepts of social isolation, loneliness, social support and a sense of belonging. There were also differences in the types of outcomes measured to assess mental wellbeing and poor mental health. Grouping the studies within a broad category of ‘social factors’ therefore represents a limitation of this review given that different aspects of the phenomena may have been being measured. The tools used to measure these variables also differed. Only one scale (The UCLA loneliness scale) was used across multiple studies [ 41 , 60 , 65 ]. Diverse mental health outcomes were measured across the studies including positive affect, flourishing, self-harm, suicide risk, depression, anxiety and paranoia.

Three studies [ 41 , 60 , 62 ] measuring loneliness, two longitudinally [ 41 , 62 ], found a consistently positive association between loneliness and poor mental health in university students. Greater loneliness was linked to greater anxiety, stress, depression, poor general mental health, paranoia, alcohol abuse and eating disorder problems. The strength of the correlations ranged from 0–3-0.4 and were all statistically significant (see Tables 3 and 4 ). Loneliness was the strongest overall predictor of mental distress, of those measured. A strong identification with university friendship groups was most protective against distress relative to other social identities [ 60 ]. Whether poor mental health is the cause, or the result of loneliness was explored further in the studies. The results suggest that for general mental health, stress, depression and anxiety, loneliness induces or exacerbates symptoms of poor mental health over time [ 60 , 62 ]. The feedback cycle is evident, with loneliness leading to poor mental health which leads to withdrawal from social contacts and further exacerbation of loneliness.

Factors associated with protecting against loneliness by fostering supportive friendships and promoting mental wellbeing were also identified. Beliefs about the value of ‘leisure coping’, and attributes of resilience and emotional intelligence had a moderate, positive and significant association with developing mental wellbeing and were explored in three studies [ 46 , 54 , 66 ].

The transition to and first year at university represent critical times when friendships are developed. Thomas et al. (2020) [ 65 ] explored the factors that predict loneliness in the first year of university. A sense of community and higher levels of ‘social capital’ were significantly associated with lower levels of loneliness. ‘Social capital’ scales measure the development of emotionally supportive friendships and the ability to adjust to the disruption of old friendships as students transition to university. Students able to form close relationships within their first year at university are less likely to experience loneliness (r-0.09, r- 0.36, r- 0.34). One study [ 38 ] investigating the relationship between student experience and being the first in the family to attend university found that these students had lower ratings for peer group interactions.

Young adults at university and in higher education are facing multiple adjustments. Their ability to cope with these is influenced by many factors. Supportive friendships and a sense of belonging are factors that strengthen coping. Nightingale et al. (2012) undertook a longitudinal study to explore what factors were associated with university adjustment in a sample of first year students ( n = 331) [ 41 ]. They found that higher skills of emotion management and emotional self-efficacy were predictive of stable adjustment. These students also reported the lowest levels of loneliness and depression. This group had the skills to recognise their emotions and cope with stressors and were confident to access support. Students with poor emotion management and low levels of emotional self-efficacy may benefit from intervention to support the development of adaptive coping strategies and seeking support.

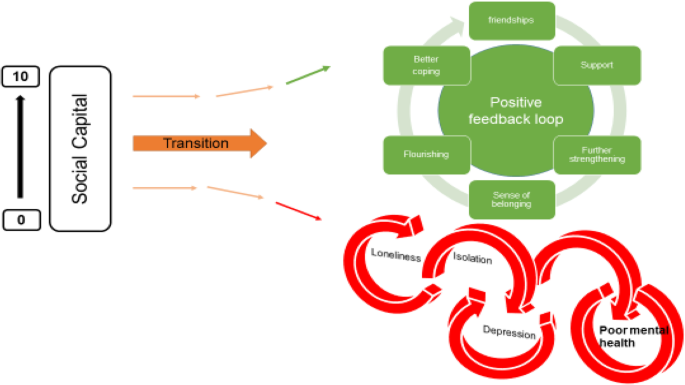

The positive and negative feedback loops

The relationship between the variables described appeared to work in positive and negative feedback loops with high levels of social capital easing the formation of a social network which acts as a critical buffer to stressors (see Fig. 3 ). Social networks and support give further strengthening and reinforcement, stimulating positive affect, engagement and flourishing. These, in turn, widen and deepen social networks for support and enhance a sense of wellbeing. Conversely young people who enter the transition to university/higher education with less social capital are less likely to identify with and locate a social network; isolation may follow, along with loneliness, anxiety, further withdrawal from contact with social networks and learning, and depression.

Triggers – factors that may act in combination with other factors to lead to poor mental health

Stress is seen as playing a key role in the development of poor mental health for students in higher education. Theoretical models and empirical studies have suggested that increases in stress are associated with decreases in student mental health [ 12 , 43 ]. Students at university experience the well-recognised stressors associated with academic study such as exams and course work. However, perhaps less well recognised are the processes of transition, requiring adapting to a new social and academic environment (Fisher 1994 cited by Denovan 2017a) [ 43 ]. Por et al. (2011) [ 46 ] in a small ( n = 130 prospective survey found a statistically significant correlation between higher levels of emotional intelligence and lower levels of perceived stress ( r = 0.40). Higher perceived stress was also associated with negative affect in two studies [ 43 , 46 ], and strongly negatively associated with positive affect (correlation -0.62) [ 54 ].

University variables

Eleven studies [ 35 , 39 , 47 , 51 , 52 , 54 , 60 , 63 , 65 , 83 , 84 ] explored university variables, and their association with mental health outcomes. The range of factors and their impact on mental health variables is limited, and there is little overlap. Knowledge gaps are shown by factors highlighted by our PPI group as potentially important but not identified in the literature (see Table 5 ). It should be noted that these may reflect the focus of our review, and our exclusion of intervention studies which may evaluate university factors.

High levels of perceived stress caused by exam and course work pressure was positively associated with poor mental health and lack of wellbeing [ 51 , 52 , 54 ]. Other potential stressors including financial anxieties and accommodation factors appeared to be less consistently associated with mental health outcomes [ 35 , 38 , 47 , 51 , 60 , 62 ]. Important mediators and buffers to these stressors are coping strategies and supportive networks (see conceptual model Appendix 2 ). One impact of financial pressures was that students who worked longer hours had less interaction with their peers, limiting the opportunities for these students to benefit from the protective effects of social support.

Red flags – behaviours associated with poor mental health and/or wellbeing

Engagement with learning and leisure activities.

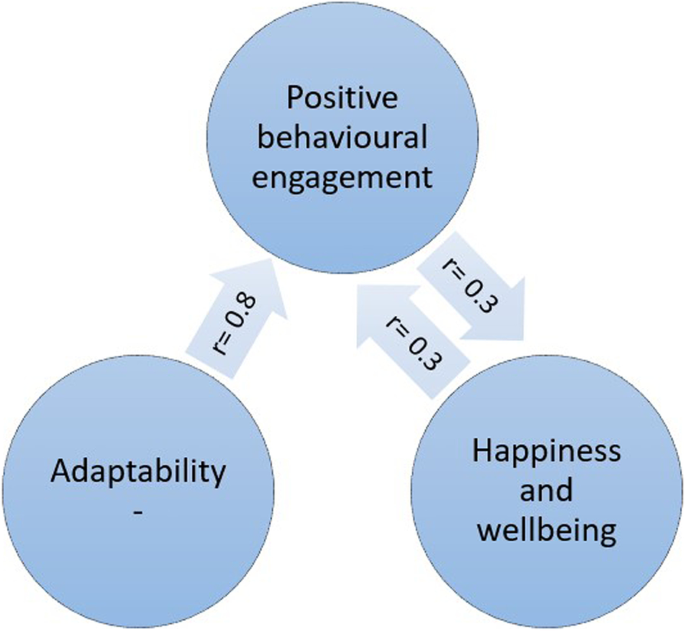

Engagement with learning activities was strongly and positively associated with characteristics of adaptability [ 39 ] and also happiness and wellbeing [ 52 ] (see Fig. 4 ). Boulton et al. (2019) [ 52 ] undertook a longitudinal survey of undergraduate students at a campus-based university. They found that engagement and wellbeing varied during the term but were strongly correlated.

Engagement and wellbeing

Engagement occurred in a wide range of activities and behaviours. The authors suggest that the strong correlation between all forms of engagement with learning has possible instrumental value for the design of systems to monitor student engagement. Monitoring engagement might be used to identify changes in the behaviour of individuals to assist tutors in providing support and pastoral care. Students also were found to benefit from good induction activities provided by the university. Greater induction satisfaction was positively and strongly associated with a sense of community at university and with lower levels of loneliness [ 65 ].

The inte r- related nature of these variables is depicted in Fig. 4 . Greater adaptability is strongly associated with more positive engagement in learning and university life. More engagement is associated with higher mental wellbeing.

Denovan et al. (2017b) [ 54 ] explored leisure coping, its psychosocial functions and its relationship with mental wellbeing. An individual’s beliefs about the benefits of leisure activities to manage stress, facilitate the development of companionship and enhance mood were positively associated with flourishing and were negatively associated with perceived stress. Resilience was also measured. Resilience was strongly and positively associated with leisure coping beliefs and with indicators of mental wellbeing. The authors conclude that resilient individuals are more likely to use constructive means of coping (such as leisure coping) to proactively cultivate positive emotions which counteract the experience of stress and promote wellbeing. Leisure coping is predictive of positive affect which provides a strategy to reduce stress and sustain coping. The belief that friendships acquired through leisure provide social support is an example of leisure coping belief. Strong emotionally attached friendships that develop through participation in shared leisure pursuits are predictive of higher levels of well-being. Friendship bonds formed with fellow students at university are particularly important for maintaining mental health, and opportunities need to be developed and supported to ensure that meaningful social connections are made.

The ‘broaden-and-build theory’ (Fredickson 2004 [ 85 ] cited by [ 54 ]) may offer an explanation for the association seen between resilience, leisure coping and psychological wellbeing. The theory is based upon the role that positive and negative emotions have in shaping human adaptation. Positive emotions broaden thinking, enabling the individual to consider a range of ways of dealing with and adapting to their environment. Conversely, negative emotions narrow thinking and limit options for adapting. The former facilitates flourishing, facilitating future wellbeing. Resilient individuals are more likely to use constructive means of coping which generate positive emotion (Tugade & Fredrickson 2004 [ 86 ], cited by [ 54 ]). Positive emotions therefore lead to growth in coping resources, leading to greater well-being.

Health behaviours at university

Seven studies [ 29 , 31 , 38 , 45 , 51 , 54 , 66 ] examined how lifestyle behaviours might be linked with mental health outcomes. The studies looked at leisure activities [ 63 , 80 ], diet [ 29 ], alcohol use [ 29 , 31 , 38 , 51 ] and sleep [ 45 ].

Depressive symptoms were independently associated with problem drinking and possible alcohol dependence for both genders but were not associated with frequency of drinking and heavy episodic drinking. Students with higher levels of depressive symptoms reported significantly more problem drinking and possible alcohol dependence [ 31 ]. Mahadevan et al. (2010) [ 51 ] compared students and non-students seen in hospital for self-harm and found no difference in harmful use of alcohol and illicit drugs.

Poor sleep quality and increased consumption of unhealthy foods were also positively associated with depressive symptoms and perceived stress [ 29 ]. The correlation with dietary behaviours and poor mental health outcomes was low, but also confirmed by the negative correlation between less perceived stress and depressive symptoms and consumption of a healthier diet.

Physical activity and participation in leisure pursuits were both strongly correlated with mental wellbeing ( r = 0.4) [ 54 ], and negatively correlated with depressive symptoms and anxiety ( r = -0.6, -0.7) [ 66 ].

Thirty studies measuring the association between a wide range of factors and poor mental health and mental wellbeing in university and college students were identified and included in this review. Our purpose was to identify the factors that contribute to the growing prevalence of poor mental health amongst students in tertiary level education within the UK. We also aimed to identify factors that promote mental wellbeing and protect against deteriorating poor mental health.

Loneliness and social isolation were strongly associated with poor mental health and a sense of belonging and a strong support network were strongly associated with mental wellbeing and happiness. These associations were strongly positive in the eight studies that explored them and are consistent with other meta-analyses exploring the link between social support and mental health [ 87 ].

Another factor that appeared to be protective was older age when starting university. A wide range of personal traits and characteristics were also explored. Those associated with resilience, ability to adjust and better coping led to improved mental wellbeing. Better engagement appeared as an important mediator to potentially explain the relationship between these two variables. Engagement led to students being able to then tap into those features that are protective and promoting of mental wellbeing.

Other important risk factors for poor mental wellbeing that emerged were those students with existing or previous mental illness. Students on the autism spectrum and those with poor social problem-solving also were more likely to suffer from poor mental health. Negative self-image was also associated with poor mental health at university. Eating disorders were strongly associated with poor mental wellbeing and were found to be far more of a risk in students at university than in a comparative group of young people not in higher education. Other studies of university students also found that pre-existing poor mental health was a strong predictor of poor mental health in university students [ 88 ].

At a family level, the experience of childhood trauma and adverse experiences including, for example, neglect, household dysfunction or abuse, were strongly associated with poor mental health in young people at university. Students with a greater number of ‘adverse childhood experiences’ were at significantly greater risk of poor mental health than those students without experience of childhood trauma. This was also identified in a review of factors associated with depression and suicide related outcomes amongst university undergraduate students [ 88 ].

Our findings, in contrast to findings from other studies of university students, did not find that female gender associated with poor mental health and wellbeing, and it also found that being a mature student was protective of mental wellbeing.

Exam and course work pressure was associated with perceived stress and poor mental health. A lack of engagement with learning activities was also associated with poor mental health. A number of variables were not consistently shown to be associated with poor mental health including financial concerns and accommodation factors. Very little evidence related to university organisation or support structures was assessed in the evidence. One study found that a good induction programme had benefits for student mental wellbeing and may be a factor that enables students to become a part of a social network positive reinforcement cycle. Involvement in leisure activities was also found to be associated with improved coping strategies and better mental wellbeing. Students with poorer mental health tended to also eat in a less healthy manner, consume more harmful levels of alcohol, and experience poorer sleep.

This evidence review of the factors that influence mental health and wellbeing indicate areas where universities and higher education settings could develop and evaluate innovations in practice. These include:

Interventions before university to improve preparation of young people and their families for the transition to university.

Exploratory work to identify the acceptability and feasibility of identifying students at risk or who many be exhibiting indications of deteriorating mental health

Interventions that set out to foster a sense of belonging and identify

Creating environments that are helpful for building social networks

Improving mental health literacy and access to high quality support services

This review has a number of limitations. Most of the included studies were cross-sectional in design, with a small number being longitudinal ( n = 7), following students over a period of time to observe changes in the outcomes being measured. Two limitations of these sources of data is that they help to understand associations but do not reveal causality; secondly, we can only report the findings for those variables that were measured, and we therefore have to support causation in assuming these are the only factors that are related to mental health.

Furthermore, our approach has segregated and categorised variables in order to better understand the extent to which they impact mental health. This approach does not sufficiently explore or reveal the extent to which variables may compound one another, for example, feeling the stress of new ways of learning may not be a factor that influences mental health until it is combined with a sense of loneliness, anxiety about financial debt and a lack of parental support. We have used our PPI group and the development of vignettes of their experiences to seek to illustrate the compounding nature of the variables identified.

We limited our inclusion criteria to studies undertaken in the UK and published within the last decade (2009–2020), again meaning we may have limited our inclusion of relevant data. We also undertook single data extraction of data which may increase the risk of error in our data.

Understanding factors that influence students’ mental health and wellbeing offers the potential to find ways to identify strategies that enhance the students’ abilities to cope with the challenges of higher education. This review revealed a wide range of variables and the mechanisms that may explain how they impact upon mental wellbeing and increase the risk of poor mental health amongst students. It also identified a need for interventions that are implemented before young people make the transition to higher education. We both identified young people who are particularly vulnerable and the factors that arise that exacerbate poor mental health. We highlight that a sense of belonging and supportive networks are important buffers and that there are indicators including lack of engagement that may enable early intervention to provide targeted and appropriate support.

Availability of data and materials

Further details of the study and the findings can be provided on request to the lead author ([email protected]).

Association of Colleges. Association of Colleges’ survey on students with mental health conditions in further education. London: 2017.

Google Scholar

Hughes G, Spanner L. The University Mental Health Charter. Leeds: Student Minds; 2019.

Sivertsen B, Hysing M, Knapstad M, Harvey AG, Reneflot A, Lønning KJ, et al. Suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm among university students: prevalence study. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(2):e26.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Storrie K, Ahern K, Tuckett A. A systematic review: students with mental health problems—a growing problem. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16(1):1–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pereira S, Reay K, Bottell J, Walker L, Dzikiti C, Platt C, Goodrham C. Student Mental Health Survey 2018: A large scale study into the prevalence of student mental illness within UK universities. 2019.

Bayram N, Bilgel N. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(8):667–72.

Bewick B, Koutsopoulou G, Miles J, Slaa E, Barkham M. Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they progress through university. Stud High Educ. 2010;35(6):633–45.

Article Google Scholar

Thorley C. Not By Degrees: Not by degrees: Improving student mental health in the UK’s universities. London: IPPR; 2017.

Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, Hunt JB. Mental health and academic success in college. BE J Econ Anal Pol. 2009;9(1):1–37.

Hysenbegasi A, Hass SL, Rowland CR. The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2005;8(3):145.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chowdry H, Crawford C, Dearden L, Goodman A, Vignoles A. Widening participation in higher education: analysis using linked administrative data. J R Stat Soc A Stat Soc. 2013;176(2):431–57.

Macaskill A. The mental health of university students in the United Kingdom. Br J Guid Couns. 2013;41(4):426–41.

Belfield C, Britton J, van der Erve L. Higher Education finance reform: Raising the repayment threshold to£ 25,000 and freezing the fee cap at £ 9,250: Institute for Fiscal Studies Briefing note. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2017. Available from https://ifs.org.uk/publications/9964 .

Benson-Egglenton J. The financial circumstances associated with high and low wellbeing in undergraduate students: a case study of an English Russell Group institution. J Furth High Educ. 2019;43(7):901–13.

Jessop DC, Herberts C, Solomon L. The impact of financial circumstances on student health. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10(3):421–39.

(2020) SCSC. Canadians’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020.

(NUS) NUoS. Coronavirus Student Survey phase III November 2020. 2020.

Hellemans K, Abizaid A, Gabrys R, McQuaid R, Patterson Z. For university students, COVID-19 stress creates perfect conditions for mental health crises. The Conversation. 2020. Available from: https://theconversation.com/for-university-students-covid-19-stress-creates-perfect-conditions-for-mental-health-crises-149127 .

England N. Children and Young People with an Eating Disorder Waiting Times: NHS England; 2021 [Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/cyped-waiting-times/

King JA, Cabarkapa S, Leow FH, Ng CH. Addressing international student mental health during COVID-19: an imperative overdue. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28(4):469.

Rana R, Smith E, Walking J. Degrees of disturbance: the new agenda; the Impact of Increasing Levels of Psychological Disturbance Amongst Students in Higher Education. England: Association for University and College Counselling Rugby; 1999.

AMOSSHE. Responding to student mental health issues: 'Duty of Care' responsibilities for student services in higher education. https://www.amosshe.org.uk/resources/Documents/AMOSSHE_Duty_of_Care_2001.pdf [accessed 24.12.2020]. (2001).

Universities UK. Student mental wellbeing in higher education. Good practice guide. London: Universities UK; 2015.

Williams M, Coare P, Marvell R, Pollard E, Houghton A-M, Anderson J. 2015. Understanding provision for students with mental health problems and intensive support needs: Report to HEFCE by the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) and Researching Equity, Access and Partnership (REAP). Institute for Employment Studies.

Hunt J, Eisenberg D. Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(1):3–10.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. In.: Oxford; 2000.

Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890.

El Ansari W, Adetunji H, Oskrochi R. Food and mental health: relationship between food and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among university students in the United Kingdom. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2014a;22(2):90–7.