- Knowledge for Change

Agriculture and Rural Development

- WEBSITE World Bank Development Research Programs

Hanan Jacoby

Klaus Deininger

Thea Hilhorst

- GHAZALA MANSURI Lead Economist

Search Documents

You have clicked on a link to a page that is not part of the beta version of the new worldbank.org. Before you leave, we’d love to get your feedback on your experience while you were here. Will you take two minutes to complete a brief survey that will help us to improve our website?

Feedback Survey

Thank you for agreeing to provide feedback on the new version of worldbank.org; your response will help us to improve our website.

Thank you for participating in this survey! Your feedback is very helpful to us as we work to improve the site functionality on worldbank.org.

Rural Development

Related sdgs, end hunger, achieve food security and improve ....

Description

Publications.

As the United Nations Secretary-General, Mr Ban Ki – Moon noted in the Millennium Development Goals Report 2015 , “ disparities between rural and urban areas remain pronounced ” and big gaps persist in different sectors:

- It is estimated that in 2015 still roughly 2.8 billion people worldwide lack access to modern energy services and more than 1 billion do not have access to electricity. For the most part this grave development burden falls on rural areas, where a lack of access to modern energy services negatively affects productivity, educational attainment and even health and ultimately exacerbates the poverty trap.

- In rural areas, only 56 per cent of births are attended by skilled health personnel, compared with 87 per cent in urban areas.

- About 16 per cent of the rural population do not use improved drinking water sources, compared to 4 per cent of the urban population.

- About 50 per cent of people living in rural areas lack improved sanitation facilities, compared to only 18 per cent of people in urban areas.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 of the Post-2015 Development Agenda calls to “ end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture ”. In particular, target 2.a devotes a specific attention to “ Increase investment, including through enhanced international cooperation, in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development and plant and livestock gene banks in order to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular least developed countries ".

Background information

Promoting sustainable agriculture and rural development (SARD) is the subject of chapter 14 of Agenda 21 .

The major objective of SARD is to increase food production in a sustainable way and enhance food security. This will involve education initiatives, utilization of economic incentives and the development of appropriate and new technologies, thus ensuring stable supplies of nutritionally adequate food, access to those supplies by vulnerable groups, and production for markets; employment and income generation to alleviate poverty; and natural resource management and environmental protection.

The Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) first reviewed Rural Development at its third session in 1995, when it noted with concern that, even though some progress had been reported, disappointment is widely expressed at the slow progress in moving towards sustainable agriculture and rural development in many countries.

Sustainable agriculture was also considered at the five-year review of implementation of Agenda 21 in 1997, at which time Governments were urged to attach high priority to implementing the commitments agreed at the World Food Summit , especially the call for at least halving the number of undernourished people in the world by the year 2015. This goal was reinforced by the Millennium Declaration adopted by Heads of State and Government in September 2000, which resolved to halve by 2015 the proportion of the world's people who suffer from hunger.

In accordance with its multi-year programme of work, agriculture with a rural development perspective was a major focus of CSD-8 in 2000, along with integrated planning and management of land resources as the sectoral theme. The supporting documentation and the discussions highlighted the linkages between the economic, social and environmental objectives of sustainable agriculture. The Commission adopted decision 8/4 which identified 12 priorities for action. It reaffirmed that the major objectives of SARD are to increase food production and enhance food security in an environmentally sound way so as to contribute to sustainable natural resource management. It noted that food security-although a policy priority for all countries-remains an unfulfilled goal. It also noted that agriculture has a special and important place in society and helps to sustain rural life and land.

Rural Development was included as one of the thematic areas along with Agriculture, Land, Drought, Desertification and Africa in the third implementation cycle CSD-16/CSD-17 .

A growing emphasis is being placed on the Nexus approach to sustainable rural development, seeking to realize synergies from the links between development factors such as energy, health, education, water, food, gender, and economic growth.

In this regard and as part of the follow up to the 2012 Conference on Sustainable Development or Rio+20 , the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA) , in collaboration with SE4All , UN-Energy and the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) , organized Global Conference on Rural Energy Access: A Nexus Approach to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication , in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Dec 4 – 6, 2013.

For more information and documents on this topic, please visit this link

Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

This Agenda is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom, We recognize that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for su...

Good practices in building innovative rural institutions to increase food security

Continued population growth, urbanization and rising incomes are likely to continue to put pressure on food demand. International prices for most agricultural commodities are set to remain at 2010 levels or higher, at least for the next decade (OECD-FAO, 2010). Small-scale producers in many developi...

Farmer’s organizations in Bangladesh: a mapping and capacity assessment

Farmers’ organizations (FOs) in Bangladesh have the potential to be true partners in, rather than “beneficiaries” of, the development process. FOs bring to the table a deep knowledge of the local context, a nuanced understanding of the needs of their communities and strong social capital. Increasing...

Electricity and education: The benefits, barriers, and recommendations for achieving the electrification of primary and secondary schools

Despite the obvious connection between electricity and educational achievement, however, the troubling scenes in Guinea, South Africa, and Uganda are repeated in thousands and thousands of parking lots, hospitals, and homes across the developing world. As one expert laments, in the educational commu...

A Survey of International Activities in Rural Energy Access and Electrification

The goal of this Survey is to highlight innovative policies that have been put into effect to stimulate electrification in rural areas of poor connection, as well as to present projects and programmes, which strive to meet this rise in energy demand and to assist communities, countries, and regions ...

Trends in Sustainable Development 2008-2009

This report highlights key developments and recent trends in agriculture, rural development, land, desertification and drought, five of the six themes being considered by the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) at its 16th and 17th sessions (2008-2009). A separate Trends Report addresses de...

Sustainable Development Innovation Briefs: Issue 9

Committee on world food security (cfs 46), joint meeting on pesticide specifications.

The "Joint Meeting on Pesticide Specifications" (JMPS) is an expert ad hoc body administered jointly by FAO and WHO, composed of scientists collectively possessing expert knowledge of the development of specifications. Their opinions and recommendations to FAO/WHO are provided in their individual ex

FAO Conference - 39th Session

Overcoming hunger and extreme poverty requires a comprehensive and proactive strategy to complement economic growth and productive approaches. This document focuses on the role of social protection in fighting hunger and extreme poverty, and linking this dimension to productive support. Focus on ru

Global Conference on Rural Energy Access: A Nexus Approach to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication

As part of the follow up to the 2012 Conference on Sustainable Development or Rio+20, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA), in collaboration with Sustainable Energy for All, UN-Energy and the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), organized this important event. The

Multistakeholder Dialogue on Implementing Sustainable Development

- January 2015 SDG 2 SDG2 focuses on ending hunger, achieving food security and improved nutrition and promoting sustainable agriculture. In particular, its targets aims to: end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round by 2030 (2.1); end all forms of malnutrition by 2030, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women and older persons (2.2.); double,by 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment (2.3); ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters and that progressively improve land and soil quality (2.4); by 2020, maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at the national, regional and international levels, and promote access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge, as internationally agreed (2.5); The alphabetical goals aim to: increase investment in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development and plant and livestock gene banks , correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets as well as adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets and their derivatives and facilitate timely access to market information, including on food reserves, in order to help limit extreme food price volatility.

- January 2009 CSD-17(Chap.2B) CSD-17 negotiated policy recommendations for most of the issues under discussion. Delegates adopted by acclamation a “Text as prepared by the Chair,” including all negotiated text as well as proposed language from the Chair for policy options and practical measures to expedite implementation of the issues under the cluster. The text included rising food prices, ongoing negotiations in the World Trade Organization (WTO) on the Doha Development Round, and an international focus on the climate change negotiations under the auspices of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- January 2008 CSD-16 (Chap. 2B) CSD-16 and CSD-17 focused on the thematic cluster of agriculture, rural development, land, drought, desertification and Africa. As far as CSD-16 is concerned, on this occasion delegates were called to review implementation of the Mauritius Strategy for Implementation and the Barbados Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States and the CSD-13 decisions on water and sanitation. A High-level Segment was also held from 14-16 May, with nearly 60 ministers in attendance.

- January 2000 MDG 1 MDG 1 aims at eradicating extreme poverty and hunger. Its three targets respectively read: halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than $1.25 a day (1.A), achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all, including women and young people (1.B), halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger (1.C).

- January 2000 CSD-8 As decided at UNGASS, the economic, sectoral and cross-sectoral themes under consideration for CSD-8 were sustainable agriculture and land management, integrating planning and management of land resources and financial resources, trade and investment and economic growth. CSD-6 to CSD-9 annually gathered at the UN Headquarters for spring meetings. Discussions at each session opened with multi-stakeholder dialogues, in which major groups were invited to make opening statements on selected themes followed by a dialogue with government representatives.

- January 1996 Rome Decl. on World Food Security The Summit aimed to reaffirm global commitment, at the highest political level, to eliminate hunger and malnutrition, and to achieve sustainable food security for all. Thank to its high visibility, the Summit contributed to raise further awareness on agriculture capacity, food insecurity and malnutrition among decision-makers in the public and private sectors, in the media and with the public at large. It also set the political, conceptual and technical blueprint for an ongoing effort to eradicate hunger at global level with the target of reducing by half the number of undernourished people by no later than the year 2015. The Rome Declaration defined seven commitments as main pillars for the achievement of sustainable food security for all whereas its Plan of Action identified the objectives and actions relevant for practical implementation of these seven commitments.

- January 1995 CSD-3 The Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) first reviewed Rural Development at its third session, when it noted with concern that, even though some progress had been reported, disappointment is widely expressed at the slow progress in moving towards sustainable agriculture and rural development in many countries.

- January 1992 Agenda 21 (Chap.14) Agenda 21 – Chapter 14 is devoted to the promotion of sustainable agriculture and rural development and the need for agricultural to satisfy the demands for food from a growing population. It acknowledges that major adjustments are needed in agricultural, environmental and macroeconomic policy, at both national and international levels, in developed as well as developing countries, to create the conditions for sustainable agriculture and rural development (SARD). It also identifies as priority the need for maintaining and improving the capacity of the higher potential agricultural lands to support an expanding population.

Rural development and digital technologies: a collaborative framework for policy-making

Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy

ISSN : 1750-6166

Article publication date: 18 August 2023

Issue publication date: 30 October 2023

The paper aims to define a model for rural development, able to stimulate collaborations between actors involved in the agrifood chain and based on digital technologies as enabling factors for such collaborations.

Design/methodology/approach

An exploratory research, based on a qualitative approach, is conducted, using both constructivist grounded theory and Gioia methodology. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and roundtables administered to Italian key players.

The authors identify five actions (definition of territorial identity, involvement of internal and external supply chain actors, definition of quality standards, cooperation intra and infra supply chains, communication through technology) for collaboration in the development of rural areas that policymakers should encourage and actors in the supply chains must implement. The paper also entails both theoretical and practical implications. From the theoretical point of view, this study contributes to the literature on the relationship between agrifood, local development and the role of technologies. From the managerial point of view, this paper provides insights for policymakers to define strategies and actions aimed at developing collaborations between actors involved in the agrifood chain and leveraging digital technologies to support rural development.

Originality/value

The paper proposes a framework for the collaboration of the actors of the agrifood sector and related food tourism that could be the basis for the development of a digital platform able to connect all the subjects involved in rural development.

- Rural development

- Digital technologies

Monda, A. , Feola, R. , Parente, R. , Vesci, M. and Botti, A. (2023), "Rural development and digital technologies: a collaborative framework for policy-making", Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy , Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 328-343. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-12-2022-0162

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Antonella Monda, Rosangela Feola, Roberto Parente, Massimiliano Vesci and Antonio Botti.

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial & non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Rural development initiatives are often based on strengthening and diversifying the agrifood sector as a mean to stimulate economic growth, generate employment opportunities and improve livelihoods in rural areas. In fact, the agrifood chain, encompassing agricultural production, processing, distribution and marketing, is an integral part of economy of a territory and plays a vital role in rural economies ( Everett and Aitchison, 2008 ). In addition, rural development initiatives often leverage the potential of tourism as a catalyst for economic growth and diversification by attracting visitors to rural areas, creating employment opportunities and stimulating local economies. In sum, synergies among agrifood sector and tourism are well known in literature ( Cafiero et al. , 2020 ): by showcasing unique agrifood products, culinary traditions and rural landscapes, tourism can generate demand for local products, services and experiences, thus contributing to the overall development of the rural communities. The potential contribution of localized agrifood systems to rural development has been emphasized and has also increased its political relevance ( Calenda Conference, 2016 ). In this context, the role of digital technologies in transforming the agrifood system has been emphasized ( Parente, 2020 ; Passarelli et al. , 2023 ). Some recent studies have analyzed the relationship between agrifood, tourism and digitalization ( Parente, 2020 ; Kumar and Shekhar, 2020 ) for the development of rural territories. More specifically, the role of digital technologies as new tools to promote local agrifood sector in the perspective of developing local tourism and rural territory, has been analyzed ( Kumar and Shekhar, 2020 ). In this research area, digital technologies are considered as an ideal tool for putting into practice collaboration strategies and represent an enabler for the development of collaborations between all actors involved in rural development ( Beckmann et al. , 2021 ).

Some studies have focused on the role of digital technologies in promoting collaboration between actors involved in both agrifood and food tourism businesses ( Horng and Tsai, 2010 ; Ashish and Shelley, 2015 ). However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, a collaboration model that puts at its center digital technologies has never been proposed and discussed.

Starting from this premise and with the goal to fill this gap, the paper aims to define a model for the development of rural territory, characterized by collaborative aspects between all actors involved in agrifood chain and related food tourism and based on digital technologies as enabling factor for such collaboration.

The paper is organized as follows. In the paragraph 2, the main literature on the connection between rural development, agrifood and tourism is analyzed. In the paragraph 3, the role of digital technologies for the rural development is discussed. The paragraph 4 discusses the main literature about the role of collaborative approaches. The paragraphs 5 and 6 present the empirical research and its results. Then, in paragraphs 7 and 8, we discuss the main results of our study and its theoretical and practical implications.

2. Rural development, agrifood and tourism

Rural development refers to the process of improving the economic, social and environmental conditions in rural areas ( Elands and Wiersum, 2001 ). It encompasses various strategies and initiatives aimed at enhancing the quality of life for rural communities, promoting economic growth and reducing disparities between rural and urban areas.

Rural development requires collaboration between governments, local authorities, civil society organizations and the private sector ( Neumeier, 2012 ). Integrated approaches that consider the unique characteristics and needs of each rural area are key to achieving sustainable and inclusive development outcomes.

In this sense, key approaches to rural development are linked to rural entrepreneurship and employment. It refers to encouraging entrepreneurship and creating employment opportunities in rural areas, vital for sustainable development. This can be achieved through supporting small- and medium-sized enterprises, promoting local industries and fostering entrepreneurship skills and training. In addition, rural development initiatives can focus on sectors beyond agriculture, such as tourism, to create a diverse range of employment opportunities. Along this vein synergies between agrifood and tourism are related to the availability of restaurants, bars, hotels, B&B and so on that leverage local food and promote the new field of food tourism ( Cafiero et al. , 2020 ; Meneguel et al. , 2022 ; Sidali et al. , 2011 ).

In recent years, researchers and policymakers have devoted great attention to agrifood sector as a key driver of rural development ( Medina et al. , 2018 ; Rachão et al. , 2019 ). More specifically, many studies emphasize the relationship between the agrifood sector and tourism in developing a competitive advantage for rural destinations ( Tsai and Wang, 2017 ; Andersson et al. , 2017 ; Vesci and Botti, 2019 ; Botti et al. , 2018 ).

When rural areas lack flagship attractions such as natural or artistic heritage, they have to focus on other assets to build a destination brand identity and attract travelers. Local food can represent an expression of place identity ( Hernández-Mogollon et al. , 2015 ) becoming a cultural identity marker that provides tourists with an opportunity to get in touch with a part of the intangible heritage of the places they visit ( Björk and Kauppinen-Räisänen, 2014 ).

The potential contribution of agrifood sector to rural development has been emphasized in the context of new rurality approach ( Pita-Morales et al. , 2015 ). New rurality approach is expression of a recent transition in the field of rural development theory from an agricultural sector approach to one which adopts broader territorial vision ( Pisani and Franceschetti, 2018 ; Ramírez-Miranda, 2014 ; Rytkönen, 2014 ), and it has also increased its political relevance ( Calenda Conference, 2016 ). The basic idea of new rurality is the interaction and integration among society, economy, institutions and environment in rural areas as key factors of rural development ( Pisani and Franceschetti, 2018 ).

In this approach, the territory is seen as a socially constructed area where interactions and collaborations between different actors and stakeholders (such as firms, educational institutions, public authorities and consumers) are key elements for rural development ( Pisani and Franceschetti, 2018 ). Thus, another fundamental aspect to consider in rural development is capacity building and participation ( Koopmans et al. , 2018 ) that go also through the awareness of local value ( Rocchi and Romano, 2006 ). Empowering rural communities through capacity building and participatory approaches is crucial for successful rural development. Engaging local communities in decision-making processes and project implementation fosters a sense of ownership and ensures that development initiatives address their specific needs and priorities. To do this, the adoption and integration of information and communication technology in rural areas that can bridge the digital divide and promote inclusive development is needed. Access to internet connectivity, digital literacy programs and e-governance initiatives can facilitate knowledge sharing, access to markets and the delivery of essential services in remote rural regions.

3. Digital technologies and rural development

In the past years, digital technologies have been playing a very important role in transforming territories ( Visvizi and Lytras, 2018 ; Troisi et al. , 2022 ; Visvizi and Pérez-delHoyo, 2021 ; Visvizi et al. , 2019 ; Troisi et al. , 2019a , 2019b ) and producing relevant impact in the rural domain ( Rolandi et al. , 2021 ). Some studies ( Zaballos et al. , 2019 ) suggested that the digitalization process can impact both agriculture (e.g. contributing to efficient use of resources) and rural sectors at all (e.g. defining new and enriched services).

The impact of the digital revolution concerns the production side of the agrifood sector, where new technologies allow customers to have complete traceability and visibility of the production process, producing significant changes in the business models of companies and the behavior of consumers of agricultural products ( Parente, 2020 ; Passarelli et al. , 2023 ).

Digital technologies offer novel instruments to foster real time adaptation of strategies and actions ( D′Aniello et al. , 2016 ) of local agrifood industries and rural territories ( Kumar and Shekhar, 2020 ).

Moreover, they allow the development of collaboration between different actors involved in agrifood tourism and rural development ( Beckmann et al. , 2021 ), acting as enabling factors for the creation of relationship in places where the social fabric is not conducive to the spontaneous creation of networks ( Cafiero et al. , 2020 ). The role of digital technologies can be supportive of rural areas, where often there are numerous small-sized producers with limited coordination or rare cooperation among each other resulting in ineffective development of the rural tourism industry ( Berjan et al. , 2020 ).

In this perspective, the challenge of rural development building on both the agrifood and food-tourism field is represented by the need to connect the actors that populate the value chain focusing on the skills and traditions that each of them use to create the identity dimension of the territory. Digital technologies could provide tools capable of responding to the growing need for interaction between all the stakeholders involved in rural development.

4. The role of collaboration for rural development

The European Union, starting from the 2020 Strategy and the 2014–2020 Cohesion Policy, invites local communities to think from a network perspective to generate territorial development processes. In line with EU dispositions, territorial development processes involve the generation, mobilization and enhancement of endogenous resources, as well as an intense activity aimed at establishing relationships and alliances with different subjects ( Brunori, 2007 ). These processes are increasingly studied through network theory which has now established itself as one of the great models of reference for the social sciences ( Castells and Blackwell, 1998 ).

awareness of territorial value by actors, referring to the recognition among local stakeholders of the inherent value of distinct qualitative attributes of the products and the potential benefits that can be gained through collaborative actions;

collaboration development among actors, referring to the gradual engagement of additional actors who align with the shared understanding of quality and the overarching objectives of the collective initiative;

consolidation of the network, referring to the reinforcement of the network's unity and cohesion around the shared notion of quality, leading to individual actors aligning their behaviors with the collective goals; and

the effective external communication of the unique quality attributes achieved through the collaborative efforts, whereby the network functions as a unified entity to convey the message.

A specific declination of network theory [represented by service theories, that is, service dominant logic ( Vargo and Lusch, 2006 ) and service science ( Maglio and Spohrer, 2008 )] deepens the role of knowledge and technology as essential factors in accomplishing value co-creation among stakeholders belonging to the same system. Service theories argue that the most suitable organizational model to support the emergence of value is the service ecosystem. It is composed by elements whose combination facilitates value co-creation between the actors of the same ecosystem. These elements are ( Polese et al. , 2018 ; Botti and Monda, 2020 ) actors, resource integration, technology and institutions. In particular, actors are all the stakeholders involved in the service exchange; resource integration occurs during actor interactions allowing for the co-learning of the actors which can turn into value co-creation; technology accelerates the passage of shared resources and the creation of new institutions ( Koskela-Huotari et al. , 2016 ); institutions are social rules, norms, shared practices regulating exchanges and acting as prerequisites for resource integration.

Combining the phases of the process of construction and enhancement of a local network according to the actor-network approach ( Rocchi and Romano, 2006 ) and the service ecosystem elements ( Polese et al. , 2018 ; Botti and Monda, 2020 ), we can identify some theoretical macro-areas of investigation that represent the key elements of a local enhancement initiative. In particular, this study assumes five basic investigation areas: (1) awareness of local value, (2) collaboration development among actors, (3) the consolidation of the network, (4) the resource integration and (5) the technology tool.

5. Methodology

5.1 research design.

To develop a proposal for a collaborative model, an exploratory research, based on a qualitative approach, is conducted, using both constructivist grounded theory ( Mills et al. , 2006 ; Glaser, 2007 ) and Gioia methodology ( Gioia et al. , 2013 ; Gioia, 2021 ). The grounded theory involves constant data comparison to develop new classifications and conceptualizations, while the Gioia methodology involves a continuous cycle of interpreting data and connecting it to existing theories and knowledge ( Magnani and Gioia, 2023 ). To achieve this, several stages of data analysis, interpretation and re-elaboration are required, which can lead to the establishment of new valid relationships between concepts and constructs. In particular, the goal is to understand how each theoretical macro-area – awareness of local value; collaboration development among actors; consolidation of the network, resource integration; technology tool – identified in Section 4, worked in the territorial context under investigation achieving the conceptualization of the collaborative model through different investigation steps (see Section 5.2 for the description of each step).

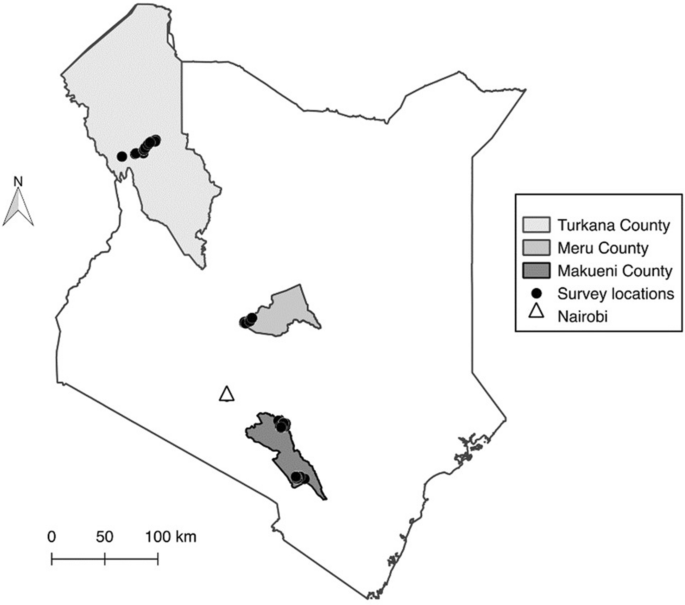

The territorial context chosen as the survey area is Irpinia, a historical-geographical district of southern Italy in the Campania Region. We chose Irpinia as it is a territory with an agricultural vocation, which lacks a cultural identity, with development lag for the tourist identity and industrial areas only in the most important urban centers.

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and roundtables conducted over 12 months, from November 2021 to November 2022, with local entrepreneurs in the agrifood and hospitality sectors, local actors, policymakers, institutional actors and citizens in the Irpinia region. In line with the adopted methodology, the subjects of the sample are selected based on their direct experience and knowledge of the studied phenomenon. Therefore, we chose purposive sampling, preferred over random sampling ( Yin, 2018 ). Each actor was considered a peculiar individual, influenced by the context in which he lives; for this reason, we tried to preserve the previous experiences, knowledge and attitudes of the interviewees in the transcription of the interviews ( Turner, 2010 ; Addeo and Montesperelli, 2007 ).

5.2 Data collection and analysis

Following the methodological principles of semi-structured interviews ( Corbetta, 2003 ), an interview outline was developed using a thematic approach instead of relying solely on structured questions. The use of thematic categories allowed for flexibility and a deeper exploration of relevant topics during the interview process and roundtables. The interview outline and topics covered in the roundtables are based on the five theoretical macro-areas of investigation identified through the literature (awareness of territorial value; collaboration development among actors; consolidation of the network, resource integration; technology tool). Both interviews and roundtables allow the extraction of raw data, recorded and transcribed.

First, we collected six direct interviews with local entrepreneurs and key players in Irpinia. Interviews were conducted both in person and by phone and lasted between 30 and 40 min. Afterward, three roundtables involving 15 key players were organized. Each of the three roundtables lasted about 2 h. Each researcher read the transcriptions autonomously and then shared the results with the others, to reach a common interpretation. To preserve the identity of the interviewees, their names are not revealed in the paper, but the subjects investigated are renamed to their roles in the agrifood chain.

We looked at information we gathered and tried to understand it using the technique of qualitative content analysis, in line with the precepts of the method proposed by Gioia (2021) . The interpretative process required to fulfill this kind of content analysis is neither structured nor codified through specific parameters. Hence, the need to integrate this technique with the criteria laid down in the Gioia methodology. The collected data (raw data) have been analyzed in three steps. The first step of data analysis involved coding the raw data obtained from the interviews to systematize the recurring elements underlying the data corpus. Researchers coded independently to derive first-order concepts and connected them inductively to the dimensions and triggers of data-driven orientation and innovation. The theoretical dimensions were revised and enriched to include novel empirical data.

The second stage of categorization involved classifying the results of the coding into second-order themes, which are more specific topics obtained from the semantic aggregation of first-order concepts. Second-order themes were identified based on the weaknesses of agrifood chains that emerged from the interviews and were connected to the key dimensions of the macro-areas of the research.

The final stage of conceptualization involved aggregating the second-order themes into practical actions aimed at solving the weaknesses identified in the interviews. The final conceptual categories were derived through the re-aggregation of the second-order themes and the results of the roundtables. The three roundtables with the main stakeholders of the sector aim to collect information and suggestions about the role of technologies in the development of collaboration. The roundtables have involved altogether 15 key players: policymakers, entrepreneurs, other institutional actors and citizens. The labels of final conceptual categories were identified through deduction processes that detected the underlying conceptual cores and reconnected them to macro-categories.

Starting from the five theoretical macro-areas of investigation emerging from the literature (awareness of territorial value; collaboration development among actors; consolidation of the network, resource integration; technology tool), raw data were collected and analyzed in three steps: coding, categorization and conceptualization. The following results arise from data collection and analysis process (see Figure 1 ).

6.1 Awareness of the value

Concerning the first investigation area, the most important aspect that emerges from the research is the lack of a territorial brand: many companies operate under their brand, and this represents an element of weakness especially from an international perspective because it does not allow to fully exploit the potential deriving from the quality of local productions offered by the territory.

The lack of a unitary brand is accompanied by limited awareness of the identity of the territory in the local community itself. This is well expressed by the following sentences:

We must activate the local community to increase their knowledge and awareness about their territory. (Local expert in planning, management and reporting of a project financed by European funds)

We need markets and external subjects to be aware of our territory, but this awareness must belong first to the local community. (Olive oil producer)

6.2 Collaboration development among actors

Regarding the second investigation area, the most important theme that emerges from the research is the presence of many small agricultural entrepreneurs and a large fragmentation of production. A fragmentation that does not only concern the production chain in the strict sense but also the broader one including all the other subjects involved internally and externally in the chain.

This aspect has been highlighted by most of the stakeholders interviewed and participating during the roundtables and can be well summarized by the following sentences:

The Irpinia agri-food chain is characterized by many small agricultural entrepreneurs who have highly parceled out their properties so the income is not very high. The goal must be to aggregate several producers to have a unified vision and move compactly on national markets. (Dean of Agricultural Educational Institute)

We must know how to dig into our identity. From the great complexity that emerges from it, we must know how to draw boundaries [..] to do this, we need to get help from external agents. (Anthropologist)

6.3 Network consolidation

The most important aspect that emerges with specific reference to network consolidation, relates to the role of policymaker and the necessity to define a long-term strategy and a vision for the development of the local territory. The role of policymakers also emerges in the need to define a set of common rules that could represent a guide for all actors of the territory. This element is well expressed by the following sentences:

There is a great need for a plan with precise indications of actions and activities to be carried out (this can also guide individuals) which serves to give a vision to the territory. The first task falls to the institution which must have a clear plan. (Local tourism councilor)

We need a forward-looking administration capable of investing and equipping itself in time and be ready when opportunities arise. (Architect)

6.4 Resource integration

Related to resource integration, emerges the low propensity to collaborate between the actors of the value chain.

This aspect has been emphasized by the actors directly involved in the chain and by most of the stakeholders indirectly participating the same.

The collaborations currently developed between the supply chains are collaborations that are the result of a need for individuals but are not systemic and systematic. A model should be built to make connections stable and systematic that in other realities have been going on for years. (Representative of local slow food association)

The level of interaction among firms is very limited and many companies do not collaborate due to cultural and mentality issues. (Dean of Agricultural Educational Institute)

Relations between operators in the supply chain are practically absent and limited to the presence of the Consortium, a body recognized by the Ministry with activities coordination functions. There is no real network between the companies and there is an absence of a cooperation policy between the wineries. (Wine producer)

There is strong individualism that is part of an alas atavistic cultural heritage. There is no consortium spirit also because there is a lack of economic impulses, there is a little predisposition to network. (Founder of a farmhouse)

If the weakness of the Irpinia agri-food chains is the “disconnection” between them, a possible solution is to integrate the elements and resources from several actors: tourist offer, intangible heritage and cultural offer, agri-food and food and wine offer. (Coordinator of first roundtable)

6.5 Technology

What emerges with specific reference to the technology investigation area, is the limited use of digital technology both as a tool to support production and commercial processes and as a tool to accelerate the knowledge exchange.

support in making customers better aware of the original values and quality of products offered;

create synergies between one’s activity, the events and cultural assets present in one's territory which are directly or indirectly connected with the products offered; and

act as a bridge with the development of collateral activities to the agricultural and primary processing ones, which are particularly important in the perspective of tourism development.

These three aspects are well summed up by the following testimonies.

Digital technologies could play a very important role as a place of aggregation and comparison between the players in the supply chain. (Wine producer)

The new digital technologies could represent an enabling factor for the development of the sector through the Application of agriculture 4.0 whose effectiveness moves along two main directions: improve productivity and respect the environment. (Dean of educational institute)

Often, in Irpinia, we have small companies that make products of absolute excellence. They cannot increase production, but they need, precisely because of this quality, that the product on the shelf can cost more to be perceived as added value. A major positioning that applies to wine, oil, beer, cheese, all those agricultural products that can be transformed. Digital technology could provide a tool to communicate products and territory contributing to increase their visibility and their value. (Coordinator of the third roundtable)

The Figure 1 synthesizes the findings discussed above by highlighting the transition from first-order concepts to second-order themes and aggregate dimensions that represent actions that need to be implemented to activate collaborations between actors involved in rural development and that will be discussed in the following paragraphs.

7. Discussion: a proposal for a collaborative framework for policymaking

Starting from the analysis of the literature and from the results of the empirical research, we elaborated a proposal for a collaborative model able to stimulate collaboration and connect all actors that populate the agrifood sectors, through the proposition of a set of actions that policymakers should encourage and actors in the supply chains should implement.

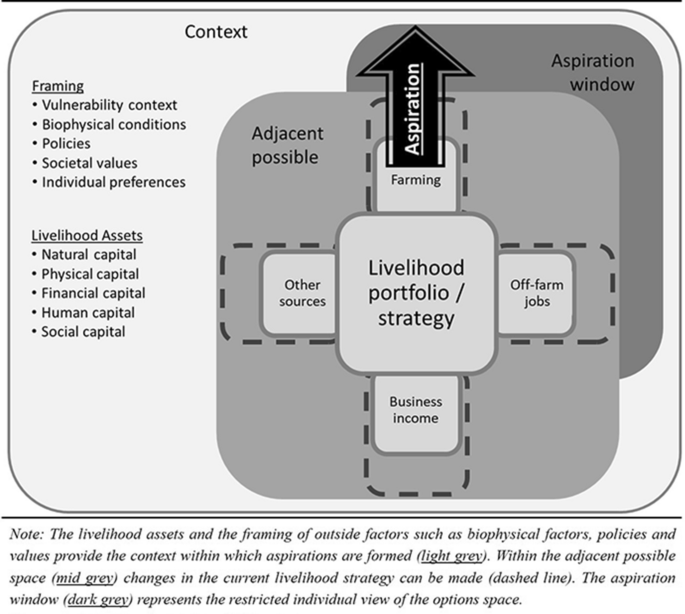

The model, shown in Figure 2 , considers the five elements emerging from the investigation of the agrifood supply chain of Irpinia.

Each of the five elements identified emerges from the literature and from the themes derived from the empirical research. The identified elements represent five practical actions to solve the weaknesses of a local supply chain. The five actions are (1) definition of territorial identity, (2) involvement of internal and external actors, (3) definition of quality standards, (4) cooperation intra and infra supply chains and (5) communication through technology.

In addition, the five elements of the proposed collaborative framework describe the trajectories to run in implementing a digital platform that can represent a collective communication space to give voice to all the actors of the territory in a perspective of enhancement of the agrifood sectors and related tourism.

7.1 Definition of territorial identity

To define a unitary identity of the territory, the genius loci that refer to the specificities and values of the territory must be considered ( Becattini, 2004 ; Vecco, 2020 ).

The concept of identity must refer first of all to the territory as a whole and secondly to typical products. In fact, it is necessary that all actors become aware of the value of the territory ( Rocchi and Romano, 2006 ), of the typical productions and of the specific qualitative attributes of the products. It is essential to have a clear understanding of the richness of the territory, to know which are the food and wine levers, which are the actors involved and the local resources.

7.2 Involvement of internal and external actors

The development of a sense of identity and a common representation of local specificities is the fundamental premise for the development of collaborations and for the implementation of initiatives to enhance local products and services. The awareness of local value is also fundamental for the development of a participatory and collaborative process that starts from the bottom and that involves all the actors of the territory and the local community itself ( Rocchi and Romano, 2006 ). Voice must be given to all the internal and external actors of the single supply chain (producers, consumers, associations, public administrations, school system, civil society and public subjects). The solution to the problem of excessive business fragmentation is the involvement of internal and external actors in supply chains. The collaboration development among actors needs to include actors close to the supply chains which, by experiencing the territory and knowing its history and values, can help create a unified image of the territory. The territory should not be understood as a geographical space but as a “choral subject”, that is, human groups that have their own “productive bump”, matured over time, which shapes, at the same time, the territory and the mindset of the population ( Becattini, 2004 ).

7.3 Definition of quality standards

The definition and maintenance of high-quality levels is essential to promote the development of the tourism and agrifood related sectors. To guarantee high-quality levels, the network should establish rules to define common quality standards ( van der Vorst et al. , 2011 ). Attention to the quality of the offer is however a broad concept that involves three different levels ( Pencarelli and Forlani, 2002 ): the quality of the products, the quality of the hospitality structures and the quality of the context and territory.

Product quality means guaranteeing the quality and typicality of the productions. Cooperation with the agricultural sector is essential to achieve and maintain product quality standards.

Quality of hospitality means attention to the service component by the accommodation facilities, but it also means professionalism of the food tourism operators, which often involves operators who are not touristic and therefore must acquire the appropriate skills in the matter.

Quality assurance of the territorial context means definition of quality standards of the territories and of the structures it offers.

7.4 Cooperation intra and infra supply chains

Cooperation between the actors of the same supply chain (intra-supply chain) and between actors of different supply chains (infra-supply chains) ( Allaoui et al. , 2019 ) belonging to the same territory is the solution to limited propensity for cooperation and lack of synergies among individual producers.

Intra-supply chain and infra-supply chain collaboration lead to resource integration among actors of a network, that is the prerequisite for value co-creation ( Vargo and Lusch, 2016 ). Resource integration represents a joint value creation that benefits all actors of ecosystem.

7.5 Communication through technology

Communication is the necessary tool to promote externally the value of the territory. Digital technology is a leverage for knowledge exchange to reach all stakeholders and to systematically promote innovation ( Polese et al. , 2022 ). Knowledge exchange through technology concerns both the production side of the agrifood sector, where new technologies allow customers to have complete traceability and visibility of the production process, both the identity side, where technologies allow customers to have complete knowledge about territory identity. Therefore, it can represent the plot that brings together the contents of the territory, and it can act as enabling factor for the collaboration development among actors in places where the social fabric is not conducive to the spontaneous creation of networks ( Cafiero et al. , 2020 ).

8. Conclusions and implications

The paper proposes an innovative framework for the collaboration of the actors of the agrifood chain to stimulate rural development. The proposed collaborative model could represent the starting point for the construction of a digital platform that aims to represent a collective communication space to give voice to all the actors of the territory being a tool of support and enablement of enhancing and strengthening the local supply chain. The construction of a digital platform should be driven by the basic idea of the collaborative model according to which the entire agrifood sector will increase its visibility and transparency through increased interconnection and cooperation of resources and the actors who work there.

In other words, the digital platform does not aim to define from above, according to a top-down approach, the actions and activities to be carried out to promote collaboration relationships functional to the development of the supply chains and the territory on which they exist. Rather, it aims to support and empower a communication scheme between a plurality of actors that can stimulate the creation from below, according to a bottom-up approach, of intra-supply chain and between supply chain collaboration strategies.

Furthermore, the digital platform should be based on the assumption that the value creation process does not occur only thanks to the companies directly involved in the production processes but involves entire systems of value creation in a process of value co-creation ( Polese et al. , 2018 ). This happens because the various actors, with their specific and respective roles, contribute to co-create value and not simply add activities along their own chain.

promotion of local places and products;

increase in the visibility of agricultural and agrifood companies in the territory; and

value co-creation processes between broad sets of stakeholders that drive positive social change.

The research entails theoretical and practical implications.

First, the study contributes to the literature on the actor-network approach ( Rocchi and Romano, 2006 ) and the service ecosystem elements ( Polese et al. , 2018 ; Botti and Monda, 2020 ; Troisi et al. , 2019a , 2019b ), demonstrating their integration and identifying basic and supporting components for the development process of the rural area.

Second, it contributes to the rural development literature, expanding the body of knowledge and giving new evidence to the idea that agrifood chain and tourism are clear components of place identity ( Hernández-Mogollon et al. , 2015 ; Vesci and Botti, 2019 ) offering the opportunity to experience the intangible heritage of the visited place ( Björk and Kauppinen-Räisänen, 2014 ).

Third, it gives traction to the conceptualization of “new rurality” ( Pita-Morales et al. , 2015 ; Pisani and Franceschetti, 2018 ; Ramírez-Miranda, 2014 ; Rytkönen, 2014 ) demonstrating how this approach works in real society describing the interactions and the collaborations that can transform a rural area in a socially constructed area.

Fourth, the study proposes an advancement in the local development literature ( Andersson et al. , 2017 ; Botti et al. , 2018 ), proposing a theoretical framework able to support local development. The identification of some actions for fostering effective rural development can improve present understanding of rural development itself and could offer some useful insights on the different kind of real activities and collaborations performed by actors’ network.

Fifth, from a practical point of view, the analysis provides relevant insights for policymakers to define adequate policies able to support rural development. In fact, having identified strategic elements (theoretical macro-areas: awareness of local value, collaboration development among actors, consolidation of the network, resource integration and using digital technology) for rural development and practical actions (definition of territorial identity, involvement of internal and external actors, definition of quality standards, cooperation intra- and infra-supply chains and communication through technology) necessary to solve the weaknesses of a local supply chain, the paper suggests the need for a differentiated use of policy instruments more targeted in relation to the specific objectives to be achieved.

Furthermore, our research suggests the necessity for policymakers to adopt a new approach aimed to create the conditions to develop collaborations between actors involved in rural development. In other terms, the role of institutions and policymakers should also include the capability to enable and to empower local actors and communities to make collaborative choices and actions. This kind of approach is important for two reasons: to create an enabling policy environment for initiatives promoted by local actors; and to allow new institutions and groups to emerge in less active places.

In more general terms, the role of policymakers in the development of a collaborative approach requires a sort of bottom-up approach in which local actors are active subjects and policymakers have to provide the supportive environment for community initiatives.

Finally, by pinpointing the main role of technology, the study highlights the constantly evolving of technology, and how it has a growing importance in rural development. This phenomenon concerns not only the actors involved in the agrifood chain process but also the territories where the agrifood companies operate.

Methodology steps

Conceptual framework for collaboration development of rural areas

Addeo , F. and Montesperelli , P. ( 2007 ), Esperienze Di Analisi Di Interviste Non Direttive , Aracne , Roma .

Allaoui , H. , Guo , Y. and Sarkis , J. ( 2019 ), “ Decision support for collaboration planning in sustainable supply chains ”, Journal of Cleaner Production , Vol. 229 , pp. 761 - 774 .

Andersson , T. , Mossberg , L. and Therkelsen , A. ( 2017 ), “ Food and tourism synergies: perspectives on consumption, production and destination development ”, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 17 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 8 .

Ashish , D. and Shelley , D. ( 2015 ), “ Evaluating the official websites of SAARC countries on their web information on food tourism ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Information Systems , Vol. 25 No. 1 , pp. 145 - 162 .

Becattini , G. ( 2004 ), “ Lo sviluppo locale ”, in Becattini , G. (Ed.), Per Un Capitalismo Dal Volto Umano , Bollati Boringhieri , Torino , pp. 202 - 244 .

Beckmann , M. , Garkisch , M. and Zeyen , A. ( 2021 ), “ Together we are strong? A systematic literature review on how SMEs use relation-based collaboration to operate in rural areas ”, Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship , Vol. 35 No. 4 , pp. 1 - 35 .

Berjan , S. , Bilali , H. , Radovic , G. , Sorajic , B. , Driouech , N. and Radosavac , A. ( 2020 ), “ Rural tourism in the republika srpska: political framework and institutional environment ”, Turkish Journal of Agricultural and Natural Sciences , Vol. 2 , pp. 1805 - 1811 .

Björk , P. and Kauppinen-Räisänen , H. ( 2014 ), “ Culinary-gastronomic tourism – a search for local food experiences ”, Nutrition and Food Science , Vol. 44 No. 4 , pp. 294 - 309 .

Botti , A. and Monda , A. ( 2020 ), “ Sustainable value co-creation and digital health: the case of trentino eHealth ecosystem ”, Sustainability , Vol. 12 No. 13 , pp. 52 - 63 .

Botti , A. , Monda , A. and Vesci , M. ( 2018 ), “ Organizing festivals, events and activities for destination marketing ”, Tourism Planning and Destination Marketing , pp. 213 - 219 .

Brunori , G. ( 2007 ), “ Local food and alternative food networks: a communication perspective ”, Anthropology of Food , No. S2 .

Cafiero , C. , Palladino , M. , Marcianò , C. and Romeo , G. ( 2020 ), “ Traditional agri-food products as a leverage to motivate tourists: a meta-analysis of tourism-information websites ”, Journal of Place Management and Development , Vol. 13 No. 2 , pp. 195 - 214 .

Calenda Conference ( 2016 ), “ Challenges for the new rurality in a changing world ”, Convocatoria de ponencias, Calenda, Publicado el lunes 1 de febrero de 2016 .

Castells , M. and Blackwell , C. ( 1998 ), “ The information age: economy, society and culture. Volume 1. The rise of the network society ”, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design , Vol. 25 , pp. 631 - 636 .

Corbetta , P. ( 2003 ), Social Research: Theory, Methods and Techniques , Sage .

D′Aniello , G. , Gaeta , A. , Gaeta , M. , Lepore , M. , Orciuoli , F. and Troisi , O. ( 2016 ), “ A new DSS based on situation awareness for smart commerce environments ”, Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing , Vol. 7 No. 1 , pp. 47 - 61 .

Elands , B.H. and Wiersum , K.F. ( 2001 ), “ Forestry and rural development in Europe: an exploration of socio-political discourses ”, Forest Policy and Economics , Vol. 3 Nos 1/2 , pp. 5 - 16 .

Everett , S. and Aitchison , C. ( 2008 ), “ The role of food tourism in sustaining regional identity: a case study of cornwall, South West England ”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , Vol. 16 No. 2 , pp. 150 - 167 .

Gioia , D. ( 2021 ), “ A systematic methodology for doing qualitative research ”, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , Vol. 57 No. 1 , pp. 20 - 29 .

Gioia , D. , Corley , K. and Aimee , H. ( 2013 ), “ Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology ”, Organizational Research Methods , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 15 - 31 .

Glaser , B.G. ( 2007 ), “ Constructivist grounded theory? ”, Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung , Vol. 19 (Supplement) , pp. 93 - 105 .

Hernández-Mogollon , J.M. , Di-Clemente , E. and Lopez-Guzmán , T. ( 2015 ), “ Culinary tourism as a culinary experience. The case study of the City of Cáceres (Spain) ”, Boletín De La Asociacion De Geografos Españoles , No. 68 , pp. 549 - 553 .

Horng , J.S. and Tsai , C.T.S. ( 2010 ), “ Government websites for promoting East Asian culinary tourism: a cross-national analysis ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 31 No. 1 , pp. 74 - 85 .

Koopmans , M.E. , Rogge , E. , Mettepenningen , E. , Knickel , K. and Šūmane , S. ( 2018 ), “ The role of multi-actor governance in aligning farm modernization and sustainable rural development ”, Journal of Rural Studies , Vol. 59 , pp. 252 - 262 .

Koskela-Huotari , K. , Edvardsson , B. , Jonas , J.M. , Sörhammar , D. and Witell , L. ( 2016 ), “ Innovation in service ecosystems – breaking, making, and maintaining institutionalized rules of resource integration ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 69 No. 8 , pp. 2964 - 2971 .

Kumar , S. and Shekhar ( 2020 ), “ Technology and innovation: changing concept of rural tourism – a systematic review ”, Open Geosciences , Vol. 12 No. 1 , pp. 737 - 752 .

Maglio , P.P. and Spohrer , J. ( 2008 ), “ Fundamentals of service science ”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , Vol. 36 No. 1 , pp. 18 - 20 .

Magnani , G. and Gioia , D. ( 2023 ), “ Using the gioia methodology in international business and entrepreneurship research ”, International Business Review , Vol. 32 No. 2 , pp. 1 - 22 .

Medina , X. , Leal , M. and Vázquez-Medina , J.A. ( 2018 ), “ Tourism and gastronomy: an introduction ”, Anthropology of Food , Vol. 13 No. 13 .

Meneguel , C.R.D.A. , Hernández-Rojas , R.D. and Mateos , M.R. ( 2022 ), “ The synergy between food and agri-food suppliers, and the restaurant sector in the world heritage City of Córdoba (Spain) ”, Journal of Ethnic Foods , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 13 .

Mills , J. , Bonner , A. and Karen , F. ( 2006 ), “ The development of constructivist grounded theory ”, International Journal of Qualitative Methods , Vol. 5 No. 1 , pp. 25 - 35 .

Murdoch , J. ( 2000 ), “ Networks – a new paradigm of rural development? ”, Journal of Rural Studies , Vol. 16 No. 4 , pp. 407 - 419 .

Neumeier , S. ( 2012 ), “ Why do social innovations in rural development matter and should they be considered more seriously in rural development research? Proposal for a stronger focus on social innovations in rural development research ”, Sociologia Ruralis , Vol. 52 No. 1 , pp. 48 - 69 .

Parente , R. ( 2020 ), “ Digitalization, consumer social responsibility, and humane entrepreneurship: good news from the future? ”, Journal of the International Council for Small Business , Vol. 1 No. 1 , pp. 56 - 63 .

Passarelli , M. , Bongiorno , G. , Cucino , V. and Cariola , A. ( 2023 ), “ Adopting new technologies during the crisis: an empirical analysis of agricultural sector ”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change , Vol. 186 , pp. 1 - 13 .

Pencarelli , T. and Forlani , F. ( 2002 ), “ Il marketing dei distretti turistici–sistemi vitali nell’economia delle esperienze ”.

Pisani , E. and Franceschetti , G. ( 2018 ), “ Territorial approaches for rural development in Latin America: a case study in Chile, Revista de la facultad de ciencias agrarias de la universidad nacional de cuyo ”, Mendoza. Argentina , Vol. 43 No. 1 , pp. 201 - 218 .

Pita-Morales , L.A. , Gonzalez-Santos , W. and Segura-Laiton , E.D. ( 2015 ), “ The rural development: an approach from the new rurality ”, Ciencia Y Agricultura , Vol. 12 No. 1 , pp. 15 - 25 .

Polese , F. , Botti , A. and Monda , A. ( 2022 ), “ Value co-creation and data-driven orientation: reflections on restaurant management practices during COVID-19 in Italy ”, Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy , Vol. 16 No. 2 , pp. 172 - 184 .

Polese , F. , Botti , A. , Grimaldi , M. , Monda , A. and Vesci , M. ( 2018 ), “ Social innovation in smart tourism ecosystems: how technology and institutions shape sustainable value co-creation ”, Sustainability , Vol. 10 No. 2 , pp. 1 - 24 .

Rachão , S. , Breda , Z. , Fernandes , C. and Joukes , V. ( 2019 ), “ Food tourism and regional development: a systematic literature review ”, European Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 21 , pp. 33 - 49 .

Ramírez-Miranda , C. ( 2014 ), “ Critical reflections on the new rurality and the rural territorial development approaches in Latin America ”, Agronomía Colombiana , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 122 - 129 .

Rocchi , B. and Romano , D. ( 2006 ), Tipicamente Buono: concezioni Di Qualità Lungo La Filiera Dei Prodotti Agro-Alimentari in Toscana , Franco Angeli , Milano , Vol. 482 .

Rolandi , S. , Brunori , G. , Bacco , M. and Scotti , I. ( 2021 ), “ The digitalization of agriculture and rural areas: towards a taxonomy of the impacts ”, Sustainability , Vol. 13 No. 9 , pp. 1 - 16 .

Rytkönen , P. ( 2014 ), “ Constructing the new rurality – challenges and opportunities (of a recent shift?) for Swedish rural policies ”, International Agricultural Policy , Vol. 2 , pp. 7 - 19 .

Sidali , K. L. , Spiller , A. and Schulze , B. (Eds) ( 2011 ), Food, Agri-Culture and Tourism: Linking Local Gastronomy and Rural Tourism: Interdisciplinary Perspectives , Springer Science and Business Media .

Troisi , O. , Grimaldi , M. and Monda , A. ( 2019a ), “ Managing smart service ecosystems through technology: how ICTs enable value cocreation ”, Tourism Analysis , Vol. 24 No. 3 , pp. 377 - 393 .

Troisi , O. , Kashef , M. and Visvizi , A. ( 2022 ), “ Managing safety and security in the smart city: Covid-19, emergencies and smart surveillance ”, in Visvizi , A. and Troisi , O. (Eds), Managing Smart Cities , Springer , Cham , pp. 73 - 88 .

Troisi , O. , Sarno , D. and Maione , G. ( 2019b ), “ Service science management engineering and design (SSMED): a semiautomatic literature review ”, Journal of Marketing Management , Vol. 35 Nos 11/12 , pp. 1015 - 1046 .

Tsai , C.-T. and Wang , Y.-C. ( 2017 ), “ Experiential value in branding food tourism ”, Journal of Destination Marketing and Management , Vol. 6 No. 1 , pp. 56 - 65 .

Turner , D.W. III , ( 2010 ), “ Qualitative interview design: a practical guide for novice investigators ”, The Qualitative Report , Vol. 15 No. 3 , p. 754 .

van der Vorst , J.G. , van Kooten , O. and Luning , P.A. ( 2011 ), “ Towards a diagnostic instrument to identify improvement opportunities for quality controlled logistics in agrifood supply chain networks ”, International Journal on Food System Dynamics , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 94 - 105 .

Vargo , S.L. and Lusch , R.F. ( 2006 ), “ Service-dominant logic: what it is, what it is not, what it might be ”, in Lusch , R.F. and Vargo , S.L. (Eds), The Service-dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate, and Directions , ME Sharpe , Armonk, NY , pp. 43 - 56 .

Vargo , S.L. and Lusch , R.F. ( 2016 ), “ Institutions and axioms: an extension and update of service-dominant logic ”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 5 - 23 .

Vecco , M. ( 2020 ), “ Genius loci as a meta-concept ”, Journal of Cultural Heritage , Vol. 41 , pp. 225 - 231 .

Vesci , M. and Botti , A. ( 2019 ), “ Festival quality, theory of planned behavior and revisiting intention: evidence from local and small Italian culinary festivals ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management , Vol. 38 , pp. 5 - 15 .

Visvizi , A. and Lytras , M. ( 2018 ), “ Rescaling and refocusing smart cities research: from mega cities to smart villages ”, Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management , Vol. 9 No. 2 , pp. 134 - 145 .

Visvizi , A. and Pérez-delHoyo , R. ( 2021 ), “ Sustainable development goals (SDGs) in the smart city: a tool or an approach? (An introduction) ”, in Visvizi , A. and Perez del Hoyo , R. (Eds), Smart Cities and the UN SDGs , Elsevier , pp. 1 - 11 .

Visvizi , A. , Lytras , M.D. and Mudri , G. ( 2019 ), “ Introduction: smart villages: relevance, approaches, policymaking implications ”, in Visvizi , A. , Lytras , M.D. and Mudri , G. (Eds), Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond , Emerald Publishing , Bingley , pp. 1 - 12 .

Yin , R.K. ( 2018 ), Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods Sixth Edition , Sage , New York, NY .

Zaballos , A.G. , Rodríguez , E.I. and Adamowicz , A. ( 2019 ), The Impact of Digital Infrastructure on the Sustainable Development Goals: A Study for Selected Latin American and Caribbean Countries , Inter-American Development Bank , Vol. 701 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

The Aspen Institute

©2024 The Aspen Institute. All Rights Reserved

- 0 Comments Add Your Comment

Rural Development: A Scan of Field Practice and Trends

August 9, 2021 • Brian Dabson & Chitra Kumar

What must happen for economic development to foster a more prosperous, healthier, equitable and environmentally sustainable rural America? This scan of field practice begins with an overview of the main economic theories and policy frameworks that guide and influence the practice of economic development, particularly in a rural context. This leads to a presentation of the results of qualitative research on economic development practice and how it is evolving, based on a series of interviews with over 40 experts representing a range of perspectives on economic development. It concludes with a commentary on how economic development can foster a more prosperous, healthier, equitable and environmentally sustainable rural America.

A publication of THRIVE RURAL – an effort of the Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group in partnership with the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute with initial support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation – aims to create a shared framework and understanding about what it will take for communities and Native nations across the rural United States to be healthy places where everyone belongs, lives with dignity, and thrives. Thrive Rural intentionally brings into focus the convergence of racial, economic and geographic inequity in rural America. Thrive Rural elevates what works and what’s needed to bridge health with community and economic development, and connects the shared aims, reality and prospects of rural America with all of America.

Related Posts

May 16, 2024 Economic Opportunities Program

May 14, 2024 The Aspen Partnership for an Inclusive Economy

The best of the Institute, right in your inbox.

Sign up for our email newsletter

Rural rising: Economic development strategies for America’s heartland

In downtown Clarksdale, Mississippi, in a repurposed freight depot built in 1918 for the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad, sits the Delta Blues Museum. The state’s oldest music museum, it is central to the growing tourism industry in the Mississippi Delta, “the land where the blues began”—once home to John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters. Yet on March 18, 2020, as the COVID-19 crisis escalated across the United States, the museum was forced to temporarily close its doors. Tourism across the country slowed to a trickle, and Clarksdale’s Coahoma County—85 miles from Memphis, 77 percent Black, and with 35 percent of its population living in poverty as of 2019—suddenly lost one of its main sources of income and employment. 1 “S1701: Poverty status in the past 12 months,” American Community Survey, US Census Bureau, 2019. By April 2020, the county’s unemployment rate had reached about 20 percent. 2 “Unemployment rate in Coahoma County, MS,” retrieved from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, March 8, 2022.

Meanwhile, about 1,000 miles northwest, in rural Chase County, Nebraska, the unemployment rate in April 2020 was only 2.2 percent. Businesses struggled to fill positions and attract workers; the poverty rate in Chase County was lower than the US average and remains so today. 3 “Unemployment rate in Coahoma County, MS,” retrieved from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, March 8, 2022.

As these stories show, rural America is not one geographical unit but a mosaic of different landscapes, people, and economic realities. 4 America at work: A national mosaic and roadmap for tomorrow , Walmart, February 2019. It includes agricultural powerhouses, postindustrial towns, and popular tourism enclaves. Some rural communities are relatively close to major cities, while others are hundreds of miles from the nearest urban hub. Some have thriving workforces and a handful of economic anchors, while others face declining populations and some of the lowest living standards in the country. Some benefit from endowments such as energy resources and beautiful landscapes, while others have few natural amenities.

Rural America is not one geographical unit but a mosaic of different landscapes, people, and economic realities.

Below, we examine the types of rural communities in the United States and suggest that attention to three foundational elements—sectors, workforce, and community and connectivity—can promote economic success. We then outline a data-driven approach to economic development that can be tailored to meet the needs of different communities and share examples of initiatives that have led to positive outcomes in rural communities throughout North America.

Tracking growth across rural America’s five community archetypes

In collaboration with Walmart, we’ve identified five archetypes of rural American communities (Exhibit 1). 5 America at work: A national mosaic and roadmap for tomorrow , Walmart, February 2019.

Americana. The largest rural community archetype, comprising 879 counties and 40 million Americans, Americana counties have slightly lower GDP and educational outcomes than urban areas. They are relatively close to major cities and often include several major employers.

Distressed Americana. Distressed Americana communities comprise 18 million people living in 973 counties (many in the South) facing high levels of poverty, low labor force participation, and low educational attainment. Historically, these communities have been hubs for agriculture, extractive industries, and manufacturing. Their decline has mirrored the struggles in these sectors.

Rural Service Hubs. Rural Service Hubs are so named because the areas (often close to highways or railways) are home to manufacturing and service industries. Because these hub communities typically serve surrounding counties that are more rural, they tend to specialize in industries such as retail and healthcare.

Great Escapes. Great Escapes are the smallest but most well off of the rural archetypes, home to wealthy enclaves and tourist destinations. They comprise 14 counties and 300,000 people. While the focus on tourism in Great Escapes communities results in many low-paying service jobs, their GDP, household income, and educational attainment outpace their rural peers.

Resource-Rich Regions. This category comprises 177 counties that are home to almost one million people. As the name suggests, these communities are defined by economic reliance on oil and gas or mining, often alongside high rates of agricultural production. Due in part to the value of the resources, household income, GDP per capita, and educational attainment in Resource-Rich Regions tend to be higher than average.

Over the past ten years, the populations of all archetypes except for Distressed Americana have grown (Exhibit 2). Resource-Rich Regions in places such as West Texas and North Dakota have seen some of the fastest growth. For example, since 2010, the populations of McKenzie County, North Dakota, and Loving County, Texas, have grown by 134 percent and 104 percent respectively, while median household incomes have increased by nearly half in nominal terms. 6 Data Buffet, Moody’s Analytics.

Yet while the population of Loving County soared, Concho County, Texas, another Resource-Rich Region, witnessed a 33 percent decline in population over the past decade. Approximately two-thirds of Resource-Rich Region counties faced similar, though often less precipitous, declines. 7 Data Buffet, Moody’s Analytics.

Counties where residents typically have access to world-class natural amenities, which are often among the Great Escapes, have been among the most uniformly successful since 2010. The appropriately named Summit County, Colorado, is home to one of the greatest concentrations of ski resorts in the world, featuring Breckenridge, Copper Mountain, Keystone, and Arapahoe Basin. Over the past decade, the county’s population has grown by 11 percent and median household income has increased by 54 percent. 8 Data Buffet, Moody’s Analytics.

Gallatin County, Montana, home to Bozeman, is a Rural Service Hub, though it also features the world-class natural amenities common to Great Escapes. It contains Big Sky Resort and is one of the gateways to Yellowstone National Park. The county, particularly the city of Bozeman, has seen a significant influx of remote workers during the pandemic, which may have contributed to a jump in housing prices of more than one-third since the beginning of 2020. 9 “Gallatin County home values,” Zillow, updated on January 31, 2022.

Meanwhile, Pender County, an Americana region on the southern coast of North Carolina, achieved 22 percent population growth from 2010 to 2020 while positioning itself as a logistics hub. Pender Commerce Park, a 450-acre industrial center developed as part of a partnership between Pender County and Wilmington Business Development, attracted FedEx Freight in 2018. 10 “FedEx Freight coming to Pender Commerce Park,” Pender County, North Carolina, February 5, 2018.