- Politics & Social Sciences

- Politics & Government

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Return this item for free

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Zelensky: A Biography Hardcover – August 8, 2022

Purchase options and add-ons.

Three years after the political novice Volodymyr Zelensky was elected to Ukraine’s highest office, he found himself catapulted into the role of war-time leader. The former comedian has become the public face of his country’s courageous and bloody struggle against a brutal invasion. Zelensky’s extraordinary leadership in the face of Russia’s aggression is an inspiration to everyone who stands opposed to the appalling violence unleashed on Ukraine. This book – the first biography of Zelensky published in English – tells his astonishing story. It has been revised and updated for this new paperback edition.

- Print length 200 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Polity

- Publication date August 8, 2022

- Dimensions 5.7 x 0.9 x 8.6 inches

- ISBN-10 1509556389

- ISBN-13 978-1509556380

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

Selected as one of The New Statesman’s Best Books of 2023

"War is a rupture―in a country's life and a leader's. Amid the calamity, Ukrainians have proven lucky in theirs. As Mr Rudenko writes at the close, the man who was 'visibly nervous' in his early bouts of diplomacy, the ingénue and clown, now has an experience of statecraft that no modern Western leader can match, nor would wish to." The Economist

"From voice of Paddington to global giant... the man behind the wartime façade" The Observer

"The first English-language biography of Zelensky reveals what Ukrainians really think of him" The Telegraph

"Serhii Rudenko's biography is a portrait of a wartime hero whose troubled past may return to haunt him... [It is] an extraordinary life story, which is still being written. Reading this biography now, in the wake of a war that upended our understanding of both Zelensky and Ukraine, presents his personal history in a new light." Lyse Doucet, The New Statesman

"Fascinating" The Guardian

"A fast-paced biography of an unexpected world leader... the author capably shows how Zelensky has displayed an astonishing transformation in the face of continued Russian aggression." Kirkus

"Rudenko has written a succinct political biography that plunges readers right into the middle of the Ukrainian political scene" Prospect Magazine

"... important and detailed...: Zelensky is easily the equal of the most impressive wartime leaders the West has ever had." Owen Matthews, The Spectator "deftly charts the transformation of a former comedian into a reforming president and then, swiftly, into a charismatic wartime leader and global figure." The New Statesman

About the Author

Serhii Rudenko is a Ukrainian journalist and political commentator who has published several books on Ukrainian politicians.

Product details

- Publisher : Polity; 1st edition (August 8, 2022)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 200 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1509556389

- ISBN-13 : 978-1509556380

- Item Weight : 14.4 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.7 x 0.9 x 8.6 inches

- #2,557 in European Politics Books

- #4,277 in Political Philosophy (Books)

- #7,328 in Political Leader Biographies

About the author

Sergii rudenko.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Ukraine invasion — explained

The roots of Russia's invasion of Ukraine go back decades and run deep. The current conflict is more than one country fighting to take over another; it is — in the words of one U.S. official — a shift in "the world order." Here are some helpful stories to make sense of it all.

Volodymyr Zelenskyy went from comedian to icon of democracy. This is how he did it

Frank Langfitt

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy delivers a virtual address to Congress at the U.S. Capitol on March 16, 2022, less than a month after Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Drew Angerer/Getty Images hide caption

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy delivers a virtual address to Congress at the U.S. Capitol on March 16, 2022, less than a month after Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

KYIV, Ukraine — Over the past year, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has undergone one of the most dramatic political transformations in modern history.

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, Zelenskyy was polling around 25%. Today, some compare him to Winston Churchill.

But as Ukraine marks the first anniversary of Russia's invasion this week, some Ukrainians still have doubts about the president's leadership.

Zelenskyy's turnaround began the morning of Feb. 24, 2022, as Russian soldiers headed toward Kyiv, intent on capturing or killing him. The president decided to stay put.

Oleksiy Arestovych, a former adviser to the office of the president, was with Zelenskyy at the beginning of the war. He says he and others urged the president to move somewhere safer.

"We said, 'What about cruise missiles?'" Arestovych recalled. "He said, 'I'll stay here.'" Arestovych says he raised the specter of Russian saboteurs and assassins. He says Zelenskyy again refused.

"Give me a machine gun," he recalled the president saying at last. "I stay here.'"

Arestovych says the military was just trying to do its job and protect the leader of the country, but Zelenskyy was thinking more broadly.

"He understood if we left Kyiv, it would put great stress on the defenders of Ukraine," Arestovych says. "He's thinking like the head of the nation."

On the second day of the war, Zelenskyy stood with his chief of staff as well as Ukraine's prime minister, next to a baroque building in the heart of Kyiv that all Ukrainians would recognize. Recording on his iPhone, Zelenskyy sent a defiant message.

"We are all here," he said. "Our soldiers are here. The citizens are here. We defend our independence."

People had wondered if Zelenskyy would flee. Daria Kaleniuk, who runs the Anti-Corruption Action Center, a public watchdog group, pointed out that Zelenskyy had downplayed the threat of war and seemed unprepared. That he stood his ground in Kyiv, she says, "honestly, it was a surprise for me."

Zelenskyy's career began in the business of entertainment

Zelenskyy became a household name in Ukraine as a comedic actor, TV star, film producer and entertainment mogul. He ran for office in 2019 based on a character he'd created for a TV show called Servant of the People .

It's about an earnest high school history teacher who rails against Ukraine's corruption and corrosive politics. When a student captures the rant on video and posts it on social media, Zelenskyy's character becomes a sensation and is swept into office.

As a real-life candidate, Zelenskyy was also a sensation, winning in a landslide with 73% of the vote. He named his political party Servant of the People.

During the campaign, Zelenskyy pledged to end the war with Russia in the east of the country, boost the economy and attack corruption. He did not govern as many had hoped.

As president, he placed friends from his entertainment career into key government posts for which they had no experience.

Critics say he embraced oligarchs and undermined government oversight. People became disillusioned.

Before he became Ukraine's president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy was a comedian and is seen here performing during the 95th Quarter comedy show, in Brovary, Ukraine. Pavlo Conchar/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images hide caption

Before he became Ukraine's president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy was a comedian and is seen here performing during the 95th Quarter comedy show, in Brovary, Ukraine.

"Zelenskyy has a controversial reputation," says Kaleniuk. "He is a good visionary, but not a very good manager. He surrounds himself with 'yes men.'"

But his decision to stay in Kyiv in the early days of the war quickly turned public opinion around. By August, about 90% of Ukrainians said they approved of his job performance. The character actor understood what the Ukrainian people needed in a time of crisis.

As if taking on a new role, Zelenskyy dressed the part. He began wearing military olive green.

"There was a transformation," says Volodymyr Yermolenko, a philosopher and journalist who runs the website Ukraine World . "Zelenskyy is a person who has this capacity of empathy. He creates this image that I'm one of you. The war only enhanced this feeling."

Yermolenko also remarks on the president's physical changes.

"He became much more mature. He has a beard right now. He's doing physical exercise. He's really trying to look like a warrior," he says.

Zelenskyy rallied international support. Six days into the invasion, he addressed the European parliament by video and brought the English interpreter to tears.

Zelenskyy's team tailored each address to its audience.

Speaking to the U.S. Congress in December, this time in English, he quoted another wartime leader, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, drawing huge rounds of applause.

The relentless, carefully crafted messages paid off. NATO allies have sent more than $40 billion in weapons to Ukraine.

Zelenskyy's start as a wartime president was faltering

To appreciate how much Zelenskyy's image and stature have changed in the past year, consider his performance leading up to the war.

I saw him in the Kherson region less than two weeks before the invasion. He was there to observe drills to defend against Russian sabotage. Afterward, Zelenskyy gave an impromptu news conference in which he was defensive and confusing. U.S. officials had warned Russia would launch a massive invasion, but Zelenskyy downplayed it.

"I believe that today in the information space there is too much information about a full-scale war," said the president, standing in the middle of a street before a table stacked with microphones.

Then, he told the assembled foreign reporters that if they knew something he didn't, they should provide him with intelligence.

"Please give us this information," he said.

In a later interview with the Washington Post , Zelenskyy acknowledged he had known an invasion was coming. He said he didn't tell the Ukrainian people to prevent panic and damage to the country's economy.

Many in Ukraine seem to accept his explanation, but they also say Zelenskyy's government failed to prepare the country to defend itself. That has made a lot of people angry, including Tetiana Chornovol.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy arrives for a press conference on April 23, 2022, in Kyiv, Ukraine. John Moore/Getty Images hide caption

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy arrives for a press conference on April 23, 2022, in Kyiv, Ukraine.

Chornovol served in Ukraine's parliament from 2014 to 2019. Later, she joined the military. I met her in the Kherson region last fall, where her job was to fire small missiles at Russian armor.

Chornovol says that – before the war – the Ukrainian army left the route north of Kyiv open to invasion, even failing to mine bridges to stop a Russian advance.

"What was done was simply criminal," said Chornovol, who proudly showed me her missile launcher which was camouflaged with Astroturf. "There was no preparation for the invasion. Kyiv was not fortified in any way."

Collaborators helped Russia in the early days of the war

The situation was even worse in the south, where the Russians rolled into Kherson almost unimpeded.

Jack Watling, senior researcher in land warfare at the Royal United Services Institute in London, says a brigade and a half of troops were supposed to be deployed to the area, but weren't. Ukrainian officers warned higher-ups the south was vulnerable to a Russian attack.

"Certainly in the south, the level of collaboration with the Russians was higher than in other areas," says Watling.

Former leaders in the region also say an area near the border with Crimea was de-mined before the Russians invaded.

Because Ukraine remains at war, parliamentarians are careful not to launch domestic political attacks. But Ivanna Klympush-Tsintsadze, a Ukrainian lawmaker with the opposition European Solidarity party, says she and others will be asking tough questions about what happened in the south as soon as — she says — Ukraine defeats Russia.

People here blame the swift loss of the region on the SBU, Ukraine's intelligence service. In July, Zelenskyy fired the head of the SBU, Ivan Bakanov, a longtime friend who had no security experience.

Kaleniuk says the episode illustrates Zelenskyy's limitations.

"He's a good president during war," she says. "He's not a very good president during a non-war period. His largest weakness is that he trusts people who are his friends and he is not tolerating different opinions."

As a young adult, Zelenskyy focused on show business, not politics

Zelenskyy grew up in the southern industrial city of Kryvyi Rih.

Alina Fialko-Smal was an actor there at the time. She says Zelenskyy used to watch her troupe perform and sought advice on becoming a dramatic actor. She discouraged Zelenskyy, who is under 5-foot-6.

"You are small, you have a hoarse voice, you are useless," she recalls telling him. "Go in some other direction."

She says she suggested comedy.

Zelenskyy studied law at Kryvyi Rih Economic Institute, where his father is a renowned educator. Natalya Voloshanyuk, a finance professor, recalls Volodymyr as clever, funny and self-confident.

One day, she says, another professor confronted him in a hallway over behavior she didn't like.

"She said, 'You should be proud that you study at this university,' " Voloshanyuk recalls, "to which he replied, 'One day you will be proud that you taught me.' "

Zelenskyy's career path has been audacious and inventive, moving from entertainment to his improbable role as global symbol of democracy. Yermolenko, the philosopher, thinks Zelenskyy's shape-shifting nature is a way to understand him and to understand Ukraine since it became an independent country some three decades ago.

"The Soviet Union collapsed and out of this anarchy, you can create something new," Yermolenko says. "I think Zelenskyy's one of one of those people. The good thing is that these people think that impossible is nothing and you can create anything."

The bad thing, he says, is that amateurs can end up in crucial positions. Yermolenko didn't vote for Zelenskyy.

He's not sure he will vote for him in the next election, whenever that is.

But he says this of Ukraine's president:

"People really recognize themselves in him, identify themselves with him, or he identifies himself with the people. And I think this is the most important thing."

Kateryna Malofieieva, Ross Pelekh and NPR London producer Morgan Ayre contributed to this story.

- Russia-Ukraine war

- volodymyr zelenskyy

- Russia Ukraine

Support 110 years of independent journalism.

Volodymyr Zelensky behind the mask

Serhii Rudenko’s biography is a portrait of a wartime hero whose troubled past may return to haunt him.

By Lyse Doucet

“Good evening friends,” began Volodymyr Zelensky . It was five minutes to midnight. Ukraine’s wartime president, hailed the world over for his masterclass in leadership, now speaks every night to the people of Ukraine, and many beyond. But this address on New Year’s Eve 2018, on the independent TV channel 1+1, came as a surprise to everyone, including the then-president, Petro Poroshenko.

“Dear Ukrainians, I’m promising you I will run for president. And I’m doing it right away.”

Ukrainian social media exploded. Poroshenko supporters who’d been settling in, Champagne glasses at the ready, for the traditional interruption of regular programming for a presidential New Year’s greeting, were incensed. “Who? This clown?” they asked. “Who is he to run for president?”

That was the night Ukraine’s star comedian and actor – famed for his cheeky, at times crude, comedic routines – entered the political stage. Was it just a publicity stunt, people wondered – another Zelensky antic to promote his popular TV serie s Servant of the People produced by his media company Kvartal 95 Studio, in which his character, the history teacher Vasiliy Holoborodko, is catapulted into the presidency?

It was no joke. Poroshenko was soon crushed by a whopping 73 per cent of the vote by a fresh-faced, clean-shaven 41-year-old – the same guy who’d spent years making jokes about him. Now Zelensky was promising to end cronyism and stop a shooting war in eastern Ukraine where Russian boots first crossed the border in 2014.

The Saturday Read

Morning call, events and offers, the green transition.

- Administration / Office

- Arts and Culture

- Board Member

- Business / Corporate Services

- Client / Customer Services

- Communications

- Construction, Works, Engineering

- Education, Curriculum and Teaching

- Environment, Conservation and NRM

- Facility / Grounds Management and Maintenance

- Finance Management

- Health - Medical and Nursing Management

- HR, Training and Organisational Development

- Information and Communications Technology

- Information Services, Statistics, Records, Archives

- Infrastructure Management - Transport, Utilities

- Legal Officers and Practitioners

- Librarians and Library Management

- OH&S, Risk Management

- Operations Management

- Planning, Policy, Strategy

- Printing, Design, Publishing, Web

- Projects, Programs and Advisors

- Property, Assets and Fleet Management

- Public Relations and Media

- Purchasing and Procurement

- Quality Management

- Science and Technical Research and Development

- Security and Law Enforcement

- Service Delivery

- Sport and Recreation

- Travel, Accommodation, Tourism

- Wellbeing, Community / Social Services

[See also: The Zelensky myth: why we should resist hero-worshipping Ukraine’s president ]

Now the world knows this Zelensky, his face bearded and lined, the supreme commander-in-chief uniting his compatriots, inspiring people the world over as he stands up to the shadowy figure of Vladimir Putin , bent on bombing and besieging Ukraine into submission. In those first breathtaking weeks after Russian tanks rumbled across the borders, the internet sparkled with every Zelensky gem. “Did you know he was the Ukrainian voice of Paddington Bear?” “He won Ukraine’s Dancing with the Stars in 2006!”

But today this conflict drags on with no end in sight; it’s everyone’s war now. The cost of the food on our tables and the power keeping the lights on in our homes connects to this barbaric conflagration in Europe’s far corner.

Zelensky now disrupts the world’s media landscape, addressing parliaments from Germany to Japan via video, popping up everywhere from the Grammys to Glastonbury . A consummate communicator, he hits all the right notes: in Britain, he channels his inner Churchill; in Germany, he invokes Ronald Reagan’s “tear down this wall” Berlin speech; in America, Pearl Harbour and 9/ll. One of the few rebukes came from Israel when Ukraine’s Jewish leader tried to draw history lessons from the Holocaust. A team of former top journalists and old TV buddies helps shape this stream. But the first and last word is said to come from Zelensky – a president who films his own video selfies, urging his nation to hold its nerve and berating Western allies to send ever more weapons in a war he’s fighting to secure their future too.

It was only a matter of time before a publisher rushed something into print about this man of the moment. The first, by the Ukrainian writer and commentator Serhii Rudenko, known for his political biographies , was initially published in Ukrainian in 2021, with a title that translates as “Zelensky without Make-Up”. Comprising 38 small chapters, some just a few pages long, the text has been updated with a preface, “Zelensky’s Political Oscar”, and an epilogue, “The President of War” – bookends of an extraordinary life story, which is still being written. Reading this biography now, in the wake of a war that upended our understanding of both Zelensky and Ukraine, presents his personal history in a new light.

It’s not a tidy chronology: Rudenko takes us back and forth in time, offering us Zelensky’s story as if it were a chocolate box, a morsel at a time. But this is no fairy tale. Some chapters tell of endearing childhood dreams. Of course, there’s a section on his entanglement with Donald Trump, who famously telephoned the unsuspecting Zelensky in 2019 looking for a little help to bring down his rival Joe Biden by asking for Biden’s son Hunter to be investigated. And there are the anecdotes of corruption, betrayals and break-ups – the unfinished business of Ukraine’s day-to-day politics that was pushed to the bottom of the pile once the task of fighting an existential war took over.

Every once in a while, the old stories creep in. This month, the European Commission’s beaming president, Ursula von der Leyen, dressed in the brilliant yellow and blue of the Ukrainian flag, announced Ukraine’s candidacy to join this European club. But behind the effusive statements, there are the whispered warnings. Although Zelensky pushed for the fast track for EU membership, Ukraine will be on a very slow road to rein in its oligarchs, crack down on corruption and build far more effective institutions of state. Cynics say it will never get to the end of that road.

“Ukraine’s packaging is great,” an international adviser in Kyiv recently told me. “But there’s not much beneath the president and all his advisers.”

Zelensky was born to Jewish parents in 1978, in Kryvyi Rih in southern central Ukraine, a “city of miners and metallurgists” and at the time one of the most polluted places in the USSR. Zelensky’s father wanted him to excel in sciences: a “B” grade in maths for Zelensky was “a day of mourning” in their home. But, in Rudenko’s telling, all his school teachers “without exception mention Zelensky as a diligent and intelligent child whose ambition was to be on the stage”. He studied law but dazzled in the KVK championships, a popular contest of comedy and song on Russian television.

But this book about the making of a charismatic communicator is also about his unmaking – at least until a war got in the way. Like the schoolteacher-turned-president he once played on the screen, Zelensky came to power promising “no to nepotism and friends in power”. But kumy – cronies or close buddies – soon turned up everywhere. They included staff from Zelensky’s production company. As Rudenko describes it, “a year after [Zelensky’s] election, the Poroshenko family was replaced by the Zelensky family – or, more precisely, by Kvartal 95 Studio”.

And it wasn’t just talented TV types. That 1+1 TV channel which broadcast Zelensky’s first election campaign speech on New Year’s eve was controlled by Ihor Kolomoisky, one of Ukraine’s wealthiest oligarchs. He had funded a private army to fight in the region bordering the Donbas in eastern Ukraine when Russian-backed separatists grabbed territory in 2014. Rudenko asks, but doesn’t answer, whether Kolomoisky (who happened to be Poroshenko’s nemesis) and Zelensky launched the TV series Servant of the People as a rehearsal for the real political party that eventually emerged and took the same name.

But Kolomoisky’s relationship with “his” president soon started unravelling, fuelled by his unsuccessful attempts to regain control, and compensation, for his nationalised PrivatBank. And now he is being investigated in the US for money laundering.

[See also: Putin and Zelensky offer contrasting visions of the future ]

In the book’s last pages we read how, the day before Russia’s invasion, Zelensky gathered 50 of Ukraine’s most prosperous citizens to urge them to play their part in the coming conflict. They’d been fighting another battle since last September, when Ukraine’s parliament passed a law directed at them. Zelensky had described the register, meant to be put in place this spring, as a way of resolving, once and for all, the relationship between the state and the oligarchs. “Or… more accurately,” as Rudenko puts it, “Zelensky’s own relationship with them.” Rudenko details how Zelensky’s team repeatedly tried to send Poroshenko to jail but concludes that “there are considerable doubts about whether Zelensky actually wants to put Poroshenko behind bars”.

The comedian who did everything possible to make Ukrainians smile had promised, “I will do everything possible so Ukrainians at least do not cry.” But now he is the nation’s consoler-in-chief as entire cities are wiped off the map, countless lives shredded, soldiers slaughtered. He keeps repeating his election pledge to do everything he can to end this conflict – including attempting talks with the man in Moscow.

Rudenko reveals that, in 2019, “Zelensky sincerely believed that, if he looked into the eyes of the Russian president he would at least see some sign of sadness about the 14,000 dead in the Donbas.” Even more, he “seemed convinced that his actor’s charisma and unique charm would work wonders”. No more.

Zelensky’s first, and so far only, opportunity to look into Putin’s eyes came in the December 2019 Normandy Format talks in Paris, which grouped together Ukraine, Russia, France and Germany. But when the fateful moment came, Ukraine’s novice “was noticeably nervous”.

The French president, Emmanuel Macron, who is given a rough ride by Ukrainians for daring to hint at the need for territorial compromise, had struck up a relationship with Zelensky long before others did. In April 2019, between the first and second rounds of Ukraine’s presidential election, he invited both Poroshenko and Zelensky to the Elysée Palace. Again, Zelensky was “visibly nervous”. But Rudenko also notes that “Zelensky and Macron understood each other almost instantaneously”.

Fast-forward to June 2022 when Zelensky, in trademark T-shirt, confidently stands outside his office in the Kyiv sunshine to welcome the finely suited Macron, along with German, Italian and Lithuanian leaders. He extends his visibly muscled arms for firm handshakes and fraternal hugs. His visitors’ admiration is palpable. So many, including Putin, had misjudged Zelensky. They expected – even urged – him to flee on the first flight out of Kyiv in those early jaw-dropping days as Russian forces closed in. Ukraine’s military prowess was underestimated; Russia’s overestimated. War is the stuff of metal – and mettle.

It’s much the same on the home front. Critics, among them Zelensky’s close friends and senior officials who had turned against him within months of his electoral triumph, made snide remarks off camera about the president’s inexperience and understanding when I interviewed them in the run-up to Russia’s invasion. Now even the ex-president Poroshenko, who, like Zelensky, has taken to wearing military garb, has rallied behind his former opponent. He recently told me, “Our unity is our most effective weapon against Putin because he’s trying to undermine us from within.” “We’re all soldiers now,” he insisted as he stood in his sandbagged position.

And Rudenko, who watched Zelensky’s early political acrobatics close-up, also can’t resist the swell of patriotic feeling. In his updated biography, he hails a leader who came to power when “few if any believed in the fighting abilities of the president… who didn’t have a clue what the Ukrainian army was”.

He doesn’t take us inside Zelensky’s head; he just gives us the stories behind his presidency. “These tribulations showed us the real Zelensky,” is his conclusion after the invasion.

But now this performer turned president turned wartime leader speaks, visibly pained, of a new stage in a grinding war which is “spiritually difficult, emotionally difficult… We don’t have a sense of how long it will last, how many more blows, losses and efforts will be needed before we see victory is on the horizon.” This phase of the conflict may be Zelensky’s toughest test yet. He’s already shown himself to be less sure-footed as he veers from vague talk of compromises to save lives to vowing to take back every inch of Ukrainian land. As a leader who can read the room, he knows Ukrainian views are hardening in this miasma of Russian war crimes. But he also senses – and warns against – the “war fatigue” in some capitals; one day it will overwhelm his own. It’s the hardest of high-wire acts, even for Zelensky.

Zelensky: A Biography Serhii Rudenko Polity Press, 200pp, £20

Purchasing a book may earn the NS a commission from Bookshop.org, who support independent bookshops

[See also: What Antony Beevor gets wrong about Russia ]

Content from our partners

How can a preventative approach to health and care help Labour deliver for patients?

The missing ingredient for future growth

The case for one million new social homes

Inside the mind of Kevin Spacey

From Willy Vlautin to Corinne Fowler: new books reviewed in short

La Chimera is a charming tale of history and myth

This article appears in the 29 Jun 2022 issue of the New Statesman, American Darkness

- OH&S, Risk Management

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Showman by Simon Shuster review – Zelenskiy’s performance of a lifetime

The definitive biography of Ukraine’s leader, from a reporter with exceptional access and a healthy lack of deference

R eal life is, of course, never as tidy or satisfying as fiction. The good guys don’t necessarily finish first, the villains don’t always get their just deserts, and the gutsy little character who no one thought would achieve anything doesn’t end up the winner merely because we want him to. Volodymyr Zelenskiy would make a tremendous hero in an undemanding Hollywood movie along the lines of Independence Day: Mr Ordinary Saves the Nation. If Russia’s ugly, wholly unnecessary war against Ukraine were something out of a blockbuster, the eighth reel would see Crimea falling to Ukraine’s victorious armed forces, Putin being chased out of office by a democratic uprising, and Zelenskiy going back to being a television comedy star, with his wife and children standing in the darkness behind the studio cameras, watching in loving admiration.

That last bit could still happen, but probably not the rest of it. Ukraine’s counteroffensive has come to nothing, Russia’s huge manpower advantages are starting to tell, Putin has faced down the only challenge to his power, and Zelenskiy is touring the world like Haile Selassie in the 1930s, appealing for help from countries that increasingly have other things to think about. Far from watching good triumph over evil, we’ll see a sordid negotiation over which bits of territory, stolen from a sovereign nation, Russia can keep hold of; while Donald Trump, re-elected, does one of his trademark deals in which he surrenders his best card in exchange for promises that, as happened with North Korea and Afghanistan, the other side doesn’t keep. This, rather than a heart-warming Hollywood ending, seems most likely now. And in Kyiv, the political opponents who’ve had to keep quiet ever since the Russian invasion are now starting to criticise Zelenskiy in increasingly sharp terms. The ethos of the superhero movie is giving way to the greyness of ordinary life.

But we mustn’t forget how well Zelenskiy has played his part. Genuinely normal and decent and without pretension, he has never forgotten where he came from: TV comedy and soap opera. When Simon Shuster calls this definitive, thoroughly researched and deeply insightful biography The Showman, he is exactly right. As a professional actor, Zelenskiy always seems to be asking himself, “What would a real leader do in my position?” It makes him a real human being – a mensch. I’ve met and interviewed something like 200 presidents, prime ministers and other assorted leaders, but I’ve only really liked three of them: Nelson Mandela, Václav Havel and Zelenskiy. In person, Zelenskiy is as warm, emotional and genuine as the other two. There’s no imperiousness, no pride of office, no standing on dignity. He treats you as an equal, and when you ask him sharp questions he doesn’t retreat into irritability or try to dodge them. If it’s an act, it’s something he’s made his own.

The Showman is a far more intimate and much better informed biography than most politicians get from journalists. Shuster is an honest and frank biographer, thoroughly equipped for the job. He was born in Moscow, the son of a Ukrainian father who had grown up near Zelenskiy’s home town, and a Russian mother. In 1989 they fled to the US, where Shuster grew up and became a staff writer for Time magazine . In 2014, when Putin’s men seized Crimea, Shuster was the first foreign journalist to get there and start reporting. He met and interviewed Zelenskiy during the presidential campaign of 2019, and after Zelenskiy was elected he spent months embedded with the presidential team: the kind of access most foreign correspondents can only dream of.

This relationship, of course, often makes reporters go soft. In order to keep the enviable position of trust they find themselves pumping out the kind of thing that their hosts want to hear. It says a great deal for Shuster, and for Zelenskiy and his team, that this hasn’t happened. Anyone who wants to know what Zelenskiy and his administration are doing and thinking reads Time, and this is thanks to Shuster. Even before Putin’s flacks started yelling that Ukraine was neo-Nazi on Russian television, Shuster was writing about the Hitlerian proclivities of the Azov Brigade. He wrote bitingly of the corruption that has been endemic inpost-Soviet Ukraine, and he was completely honest about the way Zelenskiy flirted with the thought of suppressing political opposition. Yet the president’s men and women continue to trust him.

Shuster is particularly good in describing Zelenskiy’s courage in staying put in Kyiv with his family on the morning the Russian army invaded. That ensured the failure of the initial assault. Ever since, it’s been a slogging match between Russian numbers, Nato weaponry and Ukrainian stubbornness; and as Trump’s shadow has grown and US Republicans have chosen to ignore the threat that Putin poses, the balance of the war has shifted against Ukraine. As a result, Zelenskiy’s political position is weaker. If, like some showbiz Cincinnatus, he returns to his farm, or maybe to some new television series, he’ll thoroughly deserve the honours that will be showered on him.

And presumably he’ll remain the ingenu he’s always been. One of the most arresting passages in this insightful book comes when Shuster quotes an interview Zelenskiy gave to a German reporter immediately after he had seen some appalling photographs of dead Ukrainian civilians. A few days before, Zelenskiy had visited the dormitory town of Bucha, outside Kyiv, which had been captured by Putin’s men at the start of the invasion; they had executed the inhabitants at random and tortured dozens in the most bestial fashion. And yet, in his interview, Zelenskiy didn’t express any hatred towards Putin himself. “It was,” Shutter writes, “as though Zelensky was still clinging to the illusion he had brought with him to the presidency. He seemed to believe that if he could only take Putin on a tour of Bucha, if he could bring him to the edge of that pit in the churchyard and let him peer down at the bodies, the war might stop. ‘I don’t think we have any other choice,’ he said. ‘Even though we’re fighting very hard, I don’t see any option, other than to sit with him at the negotiating table, and to talk.’”

Sadly, that’s naive. When this war ends, the result will be an angry, armed peace. Russia will hang on to most of the land it has seized, and Putin will be able to use its Ukrainian territories to stir up trouble against Kyiv whenever he needs to. The idea that he can be made to confront the horrors he has unleashed, and that this will change him, is pure sentimentality.

And Zelenskiy? He doesn’t need fame and admiration, because he had plenty of that before he stood for the presidency, and he’ll keep it for the rest of his life. He tells Shuster it’s his life’s work to get Ukraine out from Russia’s imperial shadow, and in that he has surely succeeded: eventual membership of the EU and Nato will entrench that. But the price has been shocking and savage – and though the good guys won’t have lost, they certainly won’t have triumphed.

after newsletter promotion

- Biography books

- Book of the day

- Volodymyr Zelenskiy

Most viewed

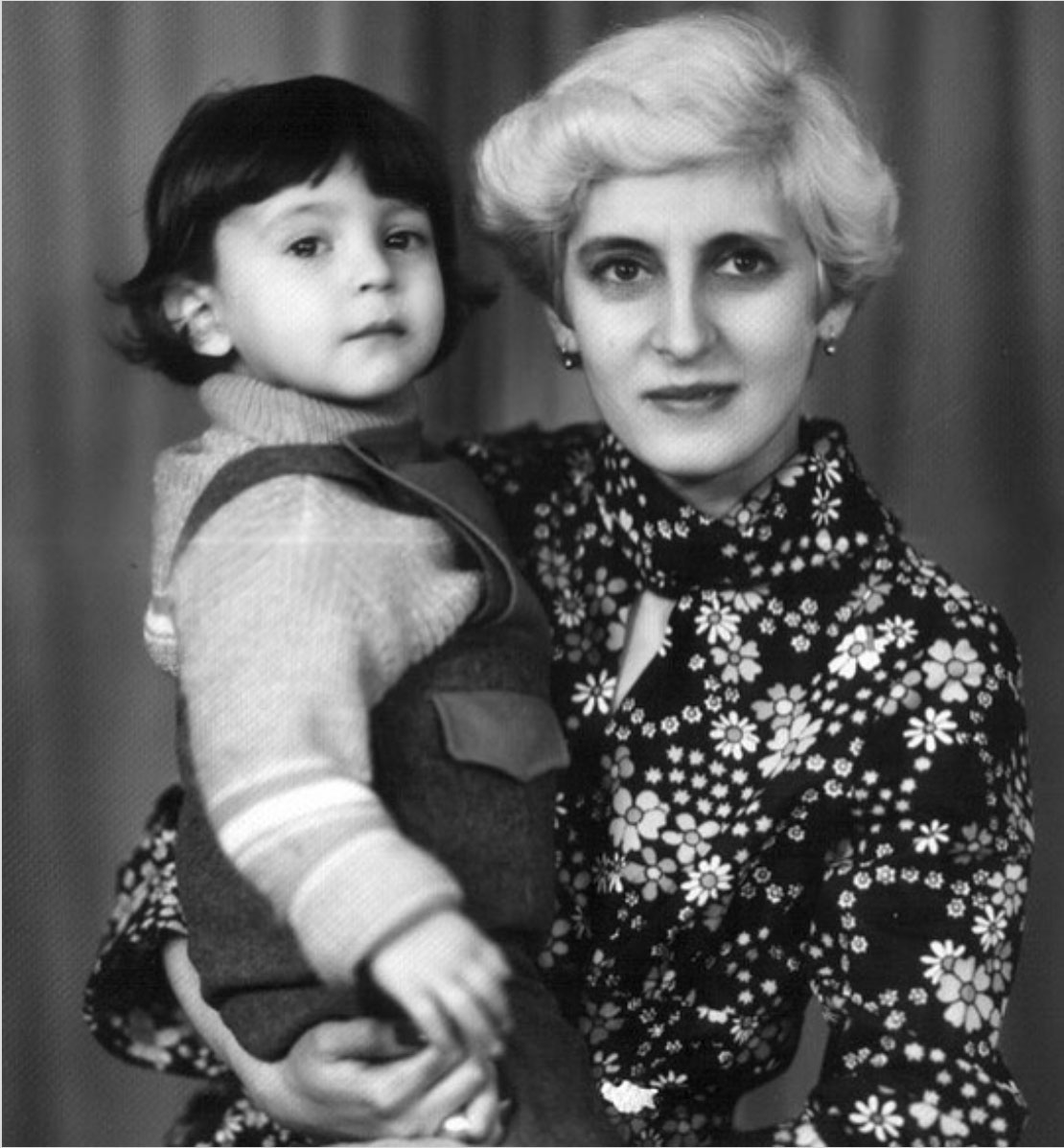

Where Zelensky Comes From

V olodymyr Zelensky was already a celebrity when his first child was born in 2004. Back then, he and his wife Olena Zelenska often lived apart. He spent his days touring and promoting his comedy troupe in Kyiv, while she often stayed with her parents in their hometown of Kryvyi Rih, the city that Zelensky would later credit with forging his character. “My big soul, my big heart,” he once called it. “Everything I have I got from there.”

The name of the town translates as “Crooked Horn,” and in conversation Zelensky and his wife tend to refer to it in Russian as Krivoy—“the crooked place,” where both of them were born in the winter of 1978, about two weeks apart.

Few if any places in Ukraine had a worse reputation in those years for violence and urban decay. The main employer in the city was the metallurgical plant, whose gargantuan blast furnaces churned out more hot steel than any other facility in the Soviet Union. During World War II, the plant was leveled by the Luftwaffe as the Nazis began their occupation of Ukraine. It was rebuilt in the 1950s and ’60s, and many thousands of veterans went to work there. So did convicts released from Soviet labor camps .

Read More: How Volodymyr Zelensky Defended Ukraine and United the World

Most of them settled into blocks of industrial housing, hives of reinforced concrete that offered almost nothing in the way of leisure, culture, or self-development. There were not nearly enough theaters, gyms, or sports facilities to occupy the local kids. By the late 1980s, when the population peaked at over 750,000, the city devolved into what Zelensky would later describe as a “banditsky gorod” —a city of bandits.

More From TIME

Olena remembers it more fondly than that. “It wasn’t full of bandits in my eyes,” she told me. “Maybe boys and girls run in different circles when they’re growing up. But yes, it’s true. There was a period in the ’90s when there was a lot of crime, especially among young people. There were gangs.”

The boys who joined these gangs, mostly teenagers, were known as beguny —literally, “runners”—because groups of them would run through the streets, beating and stabbing their rivals, flipping over cars, and smashing windows. Some of the gangs were known for using homemade explosives and improvised firearms, which they learned to fashion out of metal pipes stuffed with gunpowder and fishhooks. “Some of them got killed,” Olena said. According to local news reports, the death toll reached into the dozens by the mid-1990s.

Many more runners were maimed, beaten with clubs, or blinded with shrapnel from their homemade bombs. “Every neighborhood was in on it,” the First Lady said. “When kids of a certain age wandered into the wrong neighborhood, they could run up against a question: What part of town you from? And then the problems could start.” It was nearly impossible, she said, for teenage boys to avoid joining one of the gangs. “You could even be walking home in your own part of town, and they’d come up and ask what gang you’re with, what are you doing here. Just being on your own was scary. It wasn’t done.”

The gangs had their heyday in the late 1980s, when there were dozens of them around the city, with thousands of runners in all. Many of those who survived into the 1990s graduated into organized crime, which flourished in Kryvyi Rih during the sudden transition from communism to capitalism. Parts of the city turned into wastelands of racketeers and alcoholics. But Zelensky, thanks in large part to his family, avoided the pull of the streets.

His paternal grandfather, Semyon Zelensky, served as a senior officer in the city’s police force, investigating organized crime or, as his grandson later put it, “catching bad guys.” Stories of his service in the Second World War made a profound impression on the young Zelensky, as did the traumas of the Holocaust. Both sides of his family are Jewish, and they lost many of their own during the war.

Read More: Historians on What Putin Gets Wrong About ‘Denazification’ in Ukraine

His mother’s side of the family survived in large part because they were evacuated to Central Asia as the German occupation began in 1941. The following year, when he was still a teenager, Semyon Zelensky went to fight in the Red Army and wound up in command of a mortar platoon. All three of his brothers fought in the war, and none of them survived. Neither did their parents, Zelensky’s great-grandparents, who were killed during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine , along with over a million other Ukrainian Jews, in what became known as the “Holocaust by Bullets.”

Around their kitchen table, Zelensky’s relatives often brought up these tragedies and the crimes of the German occupiers. But little was ever said about the torments that Joseph Stalin inflicted on Ukraine. As a child, Zelensky remembers his grandmothers talking in vague terms about the years when Soviet soldiers came to confiscate the food grown in Ukraine, its vast harvests of grain and wheat all carted away at gunpoint. It was part of Stalin’s attempt in the early 1930s to remake Soviet society, and it led to a catastrophic famine known as the Holodomor —“murder by hunger”—that killed at least 3 million people in Ukraine.

In Soviet schools, the topic was taboo, including the schools where both of Zelensky’s grandmothers worked as teachers; one taught the Ukrainian language, the other taught Russian. When it came to the famine, Zelensky said, “They talked about it very carefully, that there was this period when the state took away everything, all the food.”

If they harbored any ill will toward Soviet authorities, Zelensky’s family knew better than to voice it in public. But his father Oleksandr, a stocky man of stubborn principles, refused throughout his life to join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. “He was categorically against it,” Zelensky told me, “even though that definitely hurt his career.” As a professor of cybernetics, Oleksandr Zelensky worked most of his life in the fields of mining and geology. Zelensky’s mother Rymma, an engineer by training, was closer to their only son and gentler toward him, doting on the boy much more often than she punished him.

In 1982, when Zelensky was 4 years old, his father accepted a prestigious job at a mining development in northern Mongolia, and the family moved to the town of Erdenet, which had been founded only eight years earlier to exploit one of the world’s largest deposits of copper. (The name of the town in Mongolian means “with treasure.”) The job was well paid by Soviet standards, but it forced the family to endure the pollution around the mines and the hardships of life in a frontier town. The food was bland and unfamiliar. Fermented horse milk was a local staple, and the family’s diet was heavy on mutton, with the occasional summer watermelon for which Zelensky and his mother had to stand in line for hours.

Read More: How Ukraine is Pioneering New Ways to Prosecute War Crimes

Rymma, who was slender and frail, with a long nose and beautiful features, found her health deteriorating in the harsh climate, and she soon decided to move back to Ukraine. Zelensky was a first-grader in a Mongolian school, just beginning to pick up the local language, when they traveled home in 1987. His father stayed behind, and for the next 15 years—virtually all of Zelensky’s childhood—he split his time between Erdenet, where he continued to develop his automated system for managing the mines, and Kryvyi Rih, where he taught computer science at a local university. Zelensky’s parents were often separated in those years by five time zones and around 6,000 kilometers. Even at that distance, his father continued to be a dominant presence in Zelensky’s life.

“My parents gave me no free time,” he later said. “They were always signing me up for something.” His father enrolled Zelensky in one of his math courses at the university and began to prime the boy for a career in computer science. His mother sent him to piano lessons, ballroom-dance classes, and gymnastics. To make sure he could hold his own against the local toughs, Zelensky’s parents also got him into a class for Greco-Roman wrestling.

None of these activities were really his choice, but he went along with them out of a sense of duty to his parents. “They were always quick with the discipline,” he said. The approach his father took to education was particularly severe. Zelensky called it “maximalist.” But it was typical of Jewish families in the Soviet Union, who often felt that overachievement was the only way to get a fair shake in a system rigged against them. “You have to be better than everyone else,” Zelensky said in summarizing his parents’ approach to education. “Then there might be a space for you left among the best.”

Zelensky was the product of an era of change. He was too young to experience the Soviet Union as the stagnant, repressive gerontocracy his parents had known. By the time he returned to Ukraine with his mother, the stage was set for the empire’s collapse. Moscow was broke. Its grand experiment in socialism had failed. Mikhail Gorbachev , the reluctant reformer with the soft southern accent, had already begun his doomed attempts to reform the system without breaking it apart.

Even for someone Zelensky’s age, these changes were hard to miss. He could see them in the empty grocery shelves, the endless lines for basic goods, like sausage and toilet paper. And he saw them, clear as day, on television. Under Gorbachev, the censors on Soviet TV became a lot more permissive, reflecting the wider push to relax the state’s control over the media. One of the most popular TV shows of the era was known as KVN, which stands for “The Club of the Funny and Inventive.”

It was a comedy show, but not the kind that most people in the U.S. and Europe would associate with that term. This was not the stand-up of Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy. There was no minimalism here, no lonely cynic at the microphone, breaking taboos. KVN was more like a sports league for young comedians. It involved competing troupes of performers, often made up of college students, doing sketch acts and improv in front of a panel of judges, who decided at the end of the show which team was the funniest.

By the mid-1990s, the average university and many high schools in the Russian-speaking world had at least one KVN team. Many big cities had a dozen or more, all facing off in local competitions and vying for a place in the championship league. The material was mostly wooden, with a lot of knee slappers and humdingers. The teams were also expected to sing and dance. Still, in its own hokey way, KVN could be fun to watch. For Zelensky and his friends, it was an obsession.

Read More: Inside Zelensky’s World

Most of them went to School No. 95, about a block from the central bazaar in their hometown, and not far from the university where Zelensky’s father worked as a professor. Between classes and after school, they rehearsed sketches and comedy routines, riffing off the ones they saw in the professional league on TV. “We loved it all, the KVN, the humor, and we just did it for the soul, for the fun of it,” said Vadym Pereverzev, who met Zelensky in their seventh-grade English class.

The top KVN competitions in Moscow also offered a ticket to stardom that seemed a lot more accessible to them than Hollywood, and a lot more fun than the careers available to kids in a dead-end town like theirs. “It was a rough, working-class place, and you just wanted to escape,” Pereverzev told me. “I think that was one of our main motivations.”

Their amateur shows in the school auditorium soon got the attention of a local comedy troupe that performed at a theater for college students. One of them, Oleksandr Pikalov, a handsome kid with an infectious, dimply smile, came down to School No. 95 to scout the talent. He happened upon a rehearsal in which Zelensky played a fried egg, with something stuffed under his shirt to represent the yolk. The act impressed Pikalov, and they soon began performing together.

Two years older and already in college, Pikalov introduced Zelensky to a few of the movers and shakers from the local comedy scene, including the Shefir brothers, Boris and Serhiy, who were both around 30 years old at the time. They saw Zelensky’s potential, and they became his lifelong friends, mentors, producers, and, eventually, political advisers.

Around their neighborhood in the 1990s, Zelensky’s crew stood out from the start. Instead of the track pants and leather jackets that local hoodlums wore to school, their look was a kind of ’50s retro: plaid blazers and polka-dot ties, slacks with suspenders, pressed white shirts, long hair slicked back with too much gel. Zelensky wore a ring in his ear. At a time when Nirvana was on the radio, he and his friends sang Beatles songs and listened to old-timey rock ’n’ roll.

To them this felt like a form of rebellion, mostly because it was their own. Nobody acted like that in their city, and it didn’t always go over well. Once, in his late teens, Zelensky wanted to try busking in an underpass with his guitar. He had seen people do it in the movies. It looked romantic. But Pikalov warned him that he wouldn’t make it past the second song before somebody came over to kick his ass.

“Sure enough, half an hour goes by,” Pikalov told me. “Somebody comes over and busts the guitar.” But Zelensky was laughing. He had won the bet. “He said he made it through the third song.”

Soon his performances caught the attention of his future wife, Olena. The two of them had crossed paths in the hallways of School No. 95 in Kryvyi Rih. But their homeroom classes were rivals—“like the Montagues and the Capulets,” she once told the Guardian. It was only after graduation, when Zelensky was on his way to becoming a local celebrity, that they took a liking to each other.

Olena was also involved in the KVN scene. To make the connection, Pikalov, their mutual friend, borrowed a videocassette from her, a copy of Basic Instinct, and Zelensky used it as an excuse to visit her at home and return the tape. “Then we became more than friends,” she later told me. “We were also creative colleagues.” Their performances began winning competitions around Kryvyi Rih and in other parts of Ukraine. “We were together all the time,” Olena said. “And everything sort of developed in parallel.”

Their big break came at the end of 1997, when they performed at an international KVN contest in Moscow. More than 200 teams took part from around the former Soviet Union, and Zelensky’s team, then called Transit, tied for first place with a rival team from Armenia. It was a remarkable debut for Zelensky, but he felt robbed. A video survives of him in that period, a teenage heartthrob with a raspy voice, wiping his palms against his knees as he explains his anger to the camera: the show-runner had cheated, he said, by refusing to let the judges break the tie.

Though he catalogued such gripes with an endearing smile, Zelensky was clearly unwilling to share the crown with anyone. He needed to win. Years later, when he recalled these competitions from his childhood, Zelensky admitted that, for him, “Losing is worse than death.”

Read More: TIME’s Interview with Volodymyr Zelensky

Even if the championship in Moscow did not end in an outright victory for Zelensky, it put him within reach of stardom. One of his team members, Olena Kravets, said they could hardly imagine getting that kind of opportunity. To young comedians from a place like Kryvyi Rih, she said, the major league of KVN “was not just the foot of Mount Parnassus”—the home of the muses in Greek mythology—“this was Parnassus itself.”

Its summit stood in the northern part of Moscow, in the studios and greenrooms around the Ostankino television tower, home to the biggest broadcasters in the Russian-speaking world. The major league of KVN had its main production headquarters there, and Zelensky soon made it inside. The year after their breakout performance in Moscow, they competed for the first time under the name Kvartal 95—or District 95, a nod to the neighborhood where they grew up.

Along with the Shefir brothers, who served as the team’s lead writers and producers, Zelensky soon rented an apartment in the north of Moscow and devoted himself to -becoming the champion. For all KVN teams, that required winning the favor of the league’s perennial master of ceremonies, Alexander Maslyakov. A dapper old man with a Cheshire smile, Maslyakov owned the rights to the KVN brand and hosted all the biggest competitions. His nickname among the performers was the Baron, and he and his wife, the Baroness, ran the league like a family business.

“ KVN was their empire,” Pereverzev told me. “It was their show.” At first, the Baron took a liking to Zelensky and his crew, granting them admission to the biggest stage in Moscow and the touches of fame that it brought. But there were hundreds of other teams vying for his attention, and the competition among them was vicious. “Everyone there lived with this constant emotional tension,” Olena Zelenska told me. “You were always told to know your place. The whole time we were performing in Moscow, they always told us: ‘Remember where you came from. Learn to hold a microphone. This is Central Television. You should feel lucky.’ And that’s how all the teams lived, though not so much the lucky ones from Moscow. They were loved.”

In the major league of KVN, Zelensky came face-to-face with a brand of Russian chauvinism that would, in far uglier form, manifest itself about two decades later in the Russian invasion of Ukraine. As Zelenska put it when we talked about the KVN league, “Those who were not from Moscow were always treated like slaves.”

The informal hierarchy, she said, corresponded to Moscow’s vision of itself as an imperial capital. “Teams from Ukraine were of course even farther down the ladder than all the Russian cities. They could, for instance, put up with Ryazan”—a city in western Russia—“but a place like Kryvyi Rih was something else. They’d never even seen it on a map. So we always needed to prove ourselves.”

The unwritten rules within the league reflected the role KVN played in the Russian-speaking world. Amid the ruins of the Soviet Union, it stood out as a rare institution of culture that still bound Moscow to its former vassal states. It gave kids a reason to stay within Russia’s cultural matrix rather than gravitating westward, toward Hollywood. The league had outposts in every corner of the former empire, from Moldova to Tajikistan, and all of them performed in the Russian language.

Even teams from the Baltic states, the first countries to break away from Moscow’s rule in 1990 and 1991, took part in the KVN league; its biggest annual gathering was held in Latvia, on the shores of the Baltic Sea. Viewed in a generous light, these contests could be seen as a vehicle for Russian soft power in much the same way that American movies defined what good guys and bad guys are supposed to look like for viewers around the world. To be less generous, the league could be construed as a Kremlin-backed program of cultural colonialism.

In either case, the center of gravity for KVN was always Moscow, and nostalgia for the Soviet Union was a touchstone for every team that hoped to win. Zelensky’s team was no exception, especially since their best shot at victory in the early 2000s coincided with a change of power in the Kremlin. With the election of Vladimir Putin in 2000, the Russian state embraced the symbols and icons of its imperial past, and it encouraged its people to stop being ashamed of the Soviet Union. One of Putin’s first acts in office was to change the melody of the Russian national anthem back to the Soviet one.

When it came to KVN, Putin was always an ardent supporter. He often attended KVN championships, and he liked to take the stage and offer pep talks to the performers. In return, they made him the occasional subject of jokes, though none were ever very pointed. One of the first, when he was still the Prime Minister in 1999, made fun of his soaring poll numbers after the Russian bombing campaign of Chechnya began that summer: “His popularity has already outpaced that of Mickey Mouse,” said the performer, “and is approaching that of Beavis and Butt-Head.”

Seated in the hall next to his bodyguard, Putin snickered and slumped in his chair. Less than a year later, he made clear that sharper jokes in his direction would not be tolerated. In February 2000, during Putin’s first presidential campaign, a satirical TV show called Kukly, or Puppets, depicted him as a gnome whose evil spell makes people believe he is a beautiful princess. Several of Putin’s campaign surrogates called for the Russian authors of the sketch to be imprisoned. The show soon got canceled, and the network that aired it was taken over by a state-run firm.

Read More: Column: How Putin Cannibalizes Russian Economy to Survive Personally

Zelensky, living and working in Moscow at the time, watched the turn toward authoritarianism in Russia with the same concern as all his peers in show business, and, like everyone else, he adapted. To stay on top, his team understood it would not be wise to make fun of Russia’s new leader. During one sketch in 2001, Zelensky’s character appealed to Putin as the decider “not only of my fate, but that of all Ukraine.” A year later, in a performance that brimmed with nostalgia for the Soviet Union, a member of Zelensky’s team said Putin “turned out to be a decent guy.”

But such direct references to the Russian President were rare in Zelensky’s early comedy. More often he joked about the fraught relationship between Ukraine and Russia , as in his most famous sketch from 2001, performed during the Ukrainian KVN championships. Titled “Man Born to Dance,” it cast Zelensky in the role of a Russian who can’t stop dancing as he tells a Ukrainian about his life. The script is bland and the humor juvenile. Zelensky grabs his crotch like Michael Jackson and borrows the mime-in-a-box routine from Bip the Clown.

At the end of the scene, the Russian and the Ukrainian take turns humping each other from behind. “Ukraine is always screwing Russia,” says Zelensky. “And Russia always screws Ukraine.” The punch line did not come close to the kind of satire Putin’s Russia needed and deserved. But as a piece of physical comedy, the sketch is memorable, even brilliant. Zelensky’s movements, much more than his words, seem to infect the audience with a kind of wide-mouthed glee as he shimmies and high-kicks his way through the lines in a pair of skintight leather pants.

The most magnetic thing about the sketch is him, the grin on his face, the obvious pleasure he gets from every second on the stage. The judges loved it, and that night, before a TV audience of millions, Zelensky’s team became the undisputed champions of the league in their native Ukraine. But, on the biggest stages in Moscow, victory would continue to elude them, and their troupe did not last long in the major leagues of KVN.

After competing and losing in the international championships three years in a row, they gathered up their props and left Moscow in 2003. Members of Zelensky's team agree their departure was far from amicable, though they all seem to remember it a little differently. One of them told me the breaking point with KVN was an antisemitic slur. During a rehearsal, a Russian producer stood on the stage and said loudly, in reference to Zelensky, “Where’s that little yid?”

In Zelensky’s version of the story, the management in Moscow offered him a job as a producer and writer on Russian television. It would require him to disband his troupe and send them back to Ukraine without him. Zelensky refused, and they all went home together. Halfway through their 20s, they were now successful showmen and celebrities across Ukraine. But it was still difficult for Zelensky’s parents to accept comedy as his career.

“Without a doubt,” his father said years later, “we advised him to do something different, and we thought the interest in KVN was temporary, that he would change, that he would choose a profession. After all, he’s a lawyer. He finished our institute.” Indeed, Zelensky had completed his studies and earned a law degree while performing in KVN. But he had no intention of practicing law. He found it boring.

When he got back home to Ukraine, Zelensky and his friends staged a series of weddings in their hometown of Kryvyi Rih, three Saturdays in a row. Olena Kiyashko married Volodymyr Zelensky on Sept. 6, 2003, and Pikalov and Pereverzev married their respective girlfriends. By the end of the year, when Olena was pregnant with their daughter, Zelensky moved to Kyiv to build up his new production company, Studio Kvartal 95.

Even at this early stage in his career, Zelensky’s confidence went beyond the typical swagger of a young man smitten with success. He betrayed no doubts in his team’s ability to make it big, and if he felt any fear he hid it from everyone, including his wife. For an expectant father in his mid-20s, the job offered to him in Moscow must have been more tempting than he let on. Apart from the money, it would have placed him among the glitterati, the producers and showrunners in the biggest market in the Russian-speaking world.

Read More: Inside Zelensky’s Plan to Beat Putin’s Propaganda in Russian-Occupied Ukrain e

Instead he took a risk and struck out in a much smaller pond, relying on the team of friends who looked to him for leadership and made him feel at home wherever he went. Upon arriving in Kyiv, Zelensky scored a meeting with one of the country’s biggest media executives, Alexander Rodnyansky, the head of the network that produced and broadcast the KVN league in Ukraine. The executive knew Zelensky from that circuit as a “bright young Jewish kid,” he told me. But he didn’t expect the kid to stride into his office with a risky business proposition.

Accompanied by the Shefir brothers, who were a decade older and more experienced in the industry, Zelensky did the talking. He wanted to appear with his troupe on the biggest stage in Kyiv for a nationally televised performance, and he needed Rodnyansky to give him the airtime and bankroll part of the production, marketing, and other costs. “The chutzpah on this guy, that’s what I remember,” the executive told me. “He had this bulletproof belief in himself, with these burning eyes.”

Many years later, Rodnyansky would come to see the danger hidden in that quality. It would lead Zelensky to the false belief that in the role of President , he could outmaneuver Putin and negotiate his way out of a full-scale war. “I think that confidence of his betrayed him in the end,” he said. But at the time, Zelensky’s charm won out in the negotiations with Rodnyansky, who agreed to take a risk on the performance.

It proved to be such a success that, shortly after, the team at Kvartal 95 reached a deal to make a series of variety shows that would air in Russia and Ukraine. Their tone departed from the more wholesome, aw-shucks style of KVN. The jokes took on a harder edge, and they became much more overtly political. Pereverzev, who was a writer on the shows, told me their aim was to make a version of Saturday Night Live with elements of Monty Python.

It was an untested concept on Ukrainian TV. There was no way to tell whether the audience was ready. “That was Green’s style,” he said, using Zelensky’s nickname. (The word for “green” in Ukrainian and Russian is the same: zeleny. ) “That was his main quality as a leader. He’d just say, ‘Let’s do it.’ Then we’d all get scared, and he would just tell us to trust him. All our lives it was like that. And at some point we just started to trust him, because when he said it would work out, it did.”

Excerpted from THE SHOWMAN: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr Zelensky by Simon Shuster, to be published January 23 by William Morrow. Copyright © 2024 by Simon Shuster. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers.

Correction, Jan. 5: The original version of this story misstated when Zelensky's first child was born. It was 2004, not 2003.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Zelensky: A biography by Serhii Rudenko

Book review: workmanlike telling of the ukrainian president’s story suffers from a lack of analysis of the broad forces that shaped his life.

Volodymyr Zelenskiy, centre, meets fellow European leaders, left to right, Mario Draghi of Italy, Olaf Scholz of Germany, Emmanuel Macron of France and Klaus Iohannis of Romania. Photograph: Ludovic Marin/Pool via AP

Had his presidency petered out six months ago, the political career of Volodymyr Zelenskiy would have been remembered as little more than a historical curiosity. The comic actor caused a sensational upset in 2019, when he unseated the incumbent Petro Poroshenko to win the Ukrainian presidency by a landslide, but exercising power had tested him more than winning it.

Almost two years into Zelenskiy’s term, his two campaign promises – to crack down on corruption and to end the military conflict with Russia in the east – were no closer to being realised. Aside from symbolic changes aimed at bringing his office closer to the people, such as reducing the long presidential motorcade to two cars with no sirens, his policy agenda remained as vague as it had been during his campaign. His own prime minister was secretly recorded saying the head of state had “a fog in his head” when it came to economics, and foreign diplomats who met him were struck by his intelligence but also by how much he had yet to learn.

On the international scene, Zelenskiy was perhaps best known for his unwitting cameo in the Trump impeachment. The then US president had withheld military aid to Ukraine while pressing Zelenskiy to pursue a baseless investigation into Joe Biden – a farce worthy of Servant of the People, the TV comedy in which Zelenskiy plays a history teacher who unexpectedly becomes president of Ukraine.

We know now, of course, that those two years will amount to little more than a footnote in the story of Volodymyr Zelenskiy. With Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the 44-year-old Zelenskiy has found himself at the centre of a world-historical crisis on a scale that few leaders ever face. Russia’s unprovoked aggression threatens the very existence of Ukraine; Zelenskiy is in charge of saving it. Instead of buckling under that pressure, he has risen to the moment in the most remarkable way.

Fake online shops scam: Half a million people have shared their credit card security codes

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/DQBAKGQEB6XYVPURQYF7CPMKUA.jpg)

The low-cost airline chief battling Ryanair for control of Europe’s skies

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/ZA4EQ7OMVA4JIBVFEBUFHIXU3Y.jpg)

€600 Communion money: Is it just a bribe to get people to keep the faith?

:quality(70):focal(1065x959:1075x969)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/NOP2ZPZXTBPX3LJUZNBAT5EUWI.jpg)

Meta’s Dublin docklands office for sale at knockdown price of €35m

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/CO5PVQOCIBCI5C5M44N2C36F2E.jpg)

Offered a route into exile when Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine on February 24th, he opted to stay at the presidential complex to lead the country’s resistance. He defied threats to his life in the early days of the invasion by walking the streets of the capital, recording pitch-perfect videophone messages that sought to reassure and rally Ukrainians. His tireless diplomatic efforts have won him global admiration and forced world leaders into radical policy shifts at unprecedented speed. He has come to embody Ukrainian resolve, and is perhaps the world leader whose approval his counterparts covet the most.

But beyond this wartime persona and the key points of his unusual backstory, Zelenskiy is relatively little known in the West. The thirst for information about him explains the quick translation into English of a biography by the Ukrainian journalist and political commentator Serhii Rudenko. Originally published in Ukrainian in 2021 and updated to include the early stages of the invasion, Rudenko’s conversational narrative, written in a gossipy tone, chronicles Zelenkiy’s rise in short, staccato chapters, from his childhood in Kryvyi Rih, a centre of iron mining and metallurgy in the southeast, through his wildly successful career as an actor and comedian and his insurgent campaign for the presidency.

The book is good on the febrile atmosphere of Ukrainian politics, a world of blackmail and double-crossing, where members of a small business-political elite vie for advantage by means legal and otherwise. To understand the overweening influence of oligarchs in Ukrainian public life is to see why Zelenskiy won so emphatically in 2019. Running as a Ukrainian Everyman fighting the prevailing culture of hucksterism, he spoke to a deep yearning for a clean, principled politics focusing on ordinary people’s concerns.

Rudenko writes approvingly of his subject, although he is critical of the president’s limited progress in reining in the oligarchs and outright dismissive of his pledge to eliminate nepotism in government, showing how Zelenskiy filled key positions in his administration with allies from Kvartal 95, his comedy troupe. It’s also clear that Zelenskiy was indebted to one of those oligarchs, Ihor Kolomoisky, whose 1+1 TV channel aired Servant of the People and supported Zelenskiy’s presidential campaign.

Domestic audience

The book is written primarily for a domestic audience. Foreign readers will be interested less in the minor characters from Kyiv’s political scene than in the broader forces shaping Zelenskiy’s life and thinking. In its focus on the former, the book frequently loses sight of the latter. Rudenko in general eschews analysis, making clear in the preface that he will focus on facts over “moralising, prejudice or manipulation”.

But there are some facts that call out for deeper analysis, not least Zelenskiy’s relationship with Russia. He was raised in a Russian-speaking family in the east and became a star in Russia thanks to his television shows. On the campaign trail he was accused of being too accommodating towards Moscow – he promised a Ukraine that was neither “a corrupt partner of the West” nor “Russia’s little sister” – and too willing to believe that Russia would strike a deal to end the war in the east.

At some point, it is clear, Zelenskiy realised that Russia was negotiating in bad faith and began to turn more decisively to the West, but the book does not shed much light on that process. Also absent is any exploration of the role of religion or history in shaping Zelenskiy’s worldview. Putin claims to be out to “de-Nazify” Ukraine; Zelenskiy is Jewish, and many of his relatives were killed by Nazis in the Holocaust.

Zelenskiy emerges from Rudenko’s book as likeable, canny and idealistic. As the world has seen, he has charisma and a gift for communication. But, shifting all the time from one persona to another – comedian, actor, businessman, candidate, president – he is also rather elusive.

Ultimately, it is the one role he never chose – war leader – that will define him.

Ruadhán Mac Cormaic

Ruadhán Mac Cormaic is the Editor of The Irish Times

IN THIS SECTION

Peace comes dropping slow by denis bradley: a no-frills account of the troubles and its legacy, claire keegan wins prestigious german award, openings by lucy caldwell: enlightening and enriching collection of stories that closes a loose triptych, oisín mckenna on his intoxicating debut novel: ‘i thought of it as writing in a big key, the way a pop song might be’, ukrainian author tanja maljartschuk: ‘our national memory is a mass grave ... no one was ever punished for all these crimes’, ‘a stranger entered our family and turned them all against us’, man shot dead in drimnagh gang-related violence was facing cocaine-dealing charges, asylum seekers transferred out of citywest and crooksling ahead of expected grand canal clearance, ‘a tragedy of the worst kind’: families in mourning as 18-month-old boy is killed in clare road incident, eurovision semi-final: euphoria for ireland as bambie thug qualifies for saturday’s final, latest stories, many people do not understand the link between eating and climate change, esri finds, ‘a risk to human health and the environment’: almost half of septic tanks inspected by local authorities last year failed, may is a festive month and a highlight is national biodiversity week, comeback kings real madrid stun bayern to reach champions league final, ireland moving forward with plans to recognise palestinian state in coming weeks, says tánaiste.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/sandbox.irishtimes/5OB3DSIVAFDZJCTVH2S24A254Y.png)

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Information

- Cookie Settings

- Community Standards

- Countries & Regions

Return this item for free

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. For a full refund with no deduction for return shipping, you can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition.

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet or computer – no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player