Detail of Eternal Russia (1988) by Ilya Glazunov. Photo courtesy Wikimedia/Mos.ru

The discontent of Russia

Lenin envisioned soviet unity. stalin called russia ‘first among equals’. yet russian nationalism never went away.

by Joy Neumeyer + BIO

On 19 November 1990, Boris Yeltsin gave a speech in Kyiv to announce that, after more than 300 years of rule by the Russian tsars and the Soviet ‘totalitarian regime’ in Moscow, Ukraine was free at last. Russia, he said, did not want any special role in dictating Ukraine’s future, nor did it aim to be at the centre of any future empire. Five months earlier, in June 1990, inspired by independence movements in the Baltics and the Caucasus, Yeltsin had passed a declaration of Russian sovereignty that served as a model for those of several other Soviet republics, including Ukraine. While they stopped short of demanding full separation, such statements asserted that the USSR would have only as much power as its republics were willing to give.

Russian imperial ambitions can appear to be age-old and constant. Even relatively sophisticated media often present a Kremlin drive to dominate its neighbours that seems to have passed from the tsars to Stalin, and from Stalin to Putin. So it is worth remembering that, not long ago, Russia turned away from empire. In fact, in 1990-91, it was Russian secessionism – together with separatist movements in the republics – that brought down the USSR. To defeat the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s attempt at preserving the union, Yeltsin fused the concerns of Russia’s liberal democrats and conservative nationalists into an awkward alliance. Like Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again or Boris Johnson’s Brexit, Yeltsin insisted that Russians, the Soviet Union’s dominant group, were oppressed. He called for separation from burdensome others to bring Russian renewal.

The roots of nationalist discontent lay in Russia’s peculiar status within the Soviet Union. After the Bolsheviks took control over much of the tsarist empire’s former territory, Lenin declared ‘war to the death on Great Russian chauvinism’ and proposed to uplift the ‘oppressed nations’ on its peripheries. To combat imperial inequality, Lenin called for unity, creating a federation of republics divided by nationality. The republics forfeited political sovereignty in exchange for territorial integrity, educational and cultural institutions in their own languages, and the elevation of the local ‘titular’ nationality into positions of power. Soviet policy, following Lenin, conceived of the republics as homelands for their respective nationalities (with autonomous regions and districts for smaller nationalities nested within them). The exception was the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, or RSFSR, which remained an administrative territory not associated with any ethnic or historic ‘Russia’.

Russia was the only Soviet republic that did not have its own Communist Party, capital, or Academy of Sciences. These omissions contributed to the uneasy overlap of ‘Russian’ and ‘Soviet’.

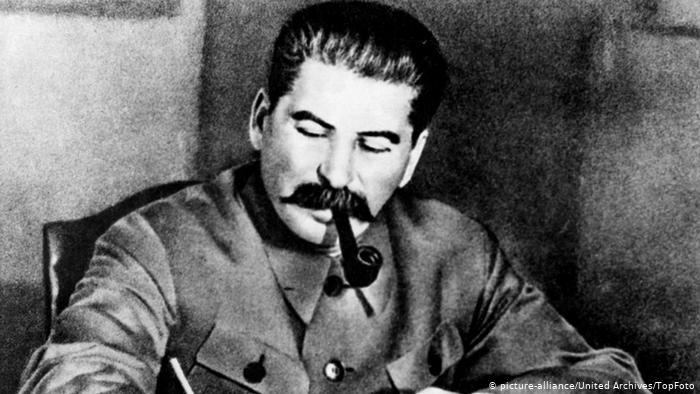

I t was Joseph Stalin, a Georgian, who promoted Russians to ‘first among equals’ in the Soviet Union, confirmed by his postwar toast that credited ‘most of all, the Russian people’ with the Soviet defeat of Nazi Germany. Nikita Khrushchev continued the Soviet commitment to the formation of a multiethnic community that would eventually converge in a shared economic, cultural and linguistic system. In this Soviet melting pot, Russia was a kind of older brother, especially to the purportedly less-advanced peoples of Central Asia. Russian remained the Soviet language of upward mobility, Russian history and culture were the most celebrated, and Russians generally thought of the Soviet Union as ‘theirs’. Like white Americans who marked other groups as ‘ethnic’, Russians saw themselves as the norm in relation to ‘national minorities’.

By the late 1960s, the Soviet Union was a majority urbanised, educated society whose legitimacy had come to rest on its status as a stable welfare state. Freed from the terror, war and mass mobilisation of the previous decades, Soviet citizens spent their leisure time watching TV and listening to records (some officially banned, but easily available thanks to state-produced consumer technologies). After the horrors of the Second World War, in which 20 to 28 million Soviet citizens died, the hard-won stability of the postwar decades led some to wonder what a meaningful life looked like when the era of epic struggle was over. The question was particularly acute for the generation that reached adulthood after Stalin’s death in 1953. They inherited the Soviet state’s crowning achievements – victory over Hitler, the conquest of space – but lacked a unifying world-historical cause. Like their peers in other highly developed societies of the 1970s, they sought answers through self-improvement quests, spiritual awakening, aimless hedonism and environmental activism. Some Soviet citizens idealised the inaccessible West. Still others looked for ‘roots’ in different national pasts. The Soviet empire subsidised distinct ethnocultural identities that were subordinate to a universalising Communist (Russian) one. As the latter grew hollow, the former was ready to fill the void.

The ‘village prose’ writers expressed various nationalities’ sense that they were losing their patrimony. These authors, who were born in rural areas and studied in Moscow, framed village-dwellers as authentic bearers of tradition, in an elegiac key equivalent to foreign contemporaries such as Wendell Berry in the United States or the Irish writer John McGahern. The most catastrophist feared that Russia’s land and people were imperilled by forces beyond their control. Valentin Rasputin’s apocalyptic novel Farewell to Matyora (1976) was inspired by the flooding of his native village to create the Bratsk Hydroelectric Power Station. In the novel, the old widow Darya condemns the project as an ecological and spiritual catastrophe. She mourns the destruction of her ancestral home but, rather than relocating to the city, she and several others stay behind and drown.

Solzhenitsyn saw Communism as a foreign ideology that separated Russia from its Orthodox heritage

The ‘village prose’ movement was not alone in perceiving Russian identity as under existential threat in the Soviet Union. Their concern was shared by Russian apparatchiks such as the Politburo member Dmitry Polyansky and members of the intelligentsia such as the October magazine editor Vsevolod Kochetov. In their view, the Soviet Union was the reincarnation of the Russian empire, destined to take up its historic mantle as an anti-Western autocracy rooted in a revitalised peasantry. It was supposedly held back by Jews (and, increasingly, people from the Caucasus and Central Asia), who leeched off Russians’ labour and resources, and impeded their advancement. Beginning in the 1960s, the Soviet party-state turned to co-opting Russian nationalist sentiments in order to fortify its weakening legitimacy. Official institutions such as the Young Guard publishing house and the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Culture and Monuments served as key recruitment centres for the Russian nationalist cause.

Much of the culture that Russian nationalists produced was compatible with the Soviet Union’s self-image. The painter Ilya Glazunov glorified figures such as Ivan the Terrible and St Sergius of Radonezh alongside portraits of Leonid Brezhnev, the Communist Party’s General Secretary. The Slavophile critic Vadim Kozhinov declared that Russia had saved the world three times: from Genghis Khan, Napoleon, and Hitler. Importantly, praise for Russians’ achievements was sometimes paired with indignation about their mistreatment, and more radical materials circulated in samizdat (self-published form). Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who viewed Communism as a foreign ideology that separated Russia from its Orthodox heritage, was stripped of his Soviet citizenship after a vicious press campaign that accused him of ‘choking with pathological hatred’ for the country and its people.

While Russian nationalists such as Solzhenitsyn were punished for directly challenging the Soviet claim to rule, Soviet rulers were punished for directly challenging Russian nationalism. In 1972, Alexander Yakovlev, the acting head of the Central Committee’s Propaganda Department and later a top advisor to Gorbachev, published a letter in a Soviet newspaper that attacked both dissident and officially aligned forms of Russian nationalism. The article led to Yakovlev’s demotion to an ambassadorship in Ottawa.

The most popular and broadly relatable image of Russian victimisation was created by the writer, director and actor Vasily Shukshin. Shukshin was born in the Altai region of Siberia to a peasant father executed during Stalin’s forced collectivisation of agriculture (a fact that was excluded from his official biography as unbefitting for a Communist Party member). After moving to Moscow, he became known for playful short stories about eccentric rural men who resist conforming to modern life by playing the balalaika or steaming in the bathhouse. By the early 1970s, however, his characters were increasingly lost and marginalised. Shukshin’s last effort as a film director and his biggest hit, Kalina Krasnaya (1974) – released in English as The Red Snowball Tree – was centred on Egor, an ex-convict who struggles to find his place after fleeing hunger in the countryside as a young man. ‘I don’t know what to do with this life,’ Egor tells the saintly pen-pal who takes him in after his release from prison. Egor ultimately reconnects with his rural roots and takes up a new life as a tractor driver, but his redemption is cut short when his former gang shows up and shoots him dead in an open field. ‘Don’t pity him,’ Egor’s murderer says coolly as he smokes a cigarette. ‘He was never a person – he was a muzhik [peasant man]. And there are plenty of them in Russia.’

Shukshin’s allegory of emasculation and deracination reflected his darkening outlook: in private remarks, he lamented the poor and depopulated state of Russia’s countryside, noting that most of his male relatives were alcoholics or in jail. ‘There’s trouble in Rus’, great trouble,’ he wrote in his notebook. ‘I feel it in my heart.’ But his work was wryly sentimental rather than angry or accusatory, and his rise from the peasantry to the intelligentsia modelled official myths of upward mobility. Shukshin won top prizes and benefited from extensive state support.

However, when Shukshin died of a heart attack shortly after Kalina Krasnaya ’s release, some nationalists whispered that he, like his most famous hero, was the victim of predation. The village prose writer Vasily Belov, a close friend, wrote in his diary that ‘if [Jews] didn’t poison [Shukshin] directly, then they certainly poisoned him indirectly. His entire life was poisoned by Jews.’ Shukshin’s cinematographer Anatoly Zabolotsky claimed in the draft of his memoirs (written in the early 1980s) that Shukshin had read the Protocols of the Elders of Zion before his death and was shocked to learn that a ‘genocide’ was being committed against the Russian people. Zabolotsky suggested that the actor who played Egor’s killer and his (Jewish) wife had murdered Shukshin to protect the secret.

U ntil the late 1980s, Russian nationalists’ paranoid xenophobia (which included broadsides against disco music and aerobics) was semi-covert and irrelevant to most. During Gorbachev’s perestroika (reform) and glasnost (openness), however, when everything from Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago (1973) to astrology was openly permitted, nationalist intellectuals’ concerns found freer and wider expression in political life, where they latched on to broader dissatisfaction. As activists in the Caucasus and the Baltics began demanding greater cultural and political autonomy, in April 1989 Soviet troops crushed a large demonstration in Tbilisi.

Denunciations of this repression kicked off the opening sessions at the televised First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR in May 1989. Valentin Rasputin, author of Farewell to Matyora , was among the delegates. After listening to Baltic and Georgian deputies’ complaints about Russian imperialism, Rasputin took the floor to bitterly suggest that

perhaps it is Russia that should secede from the Union, since you accuse her of all your misfortunes and since her backwardness and awkwardness obstruct your progressive aspirations? … We could then pronounce the word ‘Russian’ without fear of being rebuked for nationalism, we could talk openly about our national identity … Believe me, we’re fed up with being scapegoats, with being mocked and spat upon.

Under the influence of other republics’ demands, Russian nationalists’ long-running resentment was rapidly turning into separatism.

‘Enough feeding the other republics!’ he exclaimed in a speech to industrial workers

Gorbachev’s political and economic devolution of the USSR produced chaos, including severe food shortages. The suddenly uncensored media exposed violence and degradation ranging from Stalinist repressions to the flailing war in Afghanistan. In response to the rush of bad news, the intelligentsia lamented Russia’s ‘total ruin’. The cultural historian and Gulag survivor Dmitry Likhachev said that the communist regime ‘humiliated and robbed Russia so much, that Russians can hardly breathe’. In Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (2021), Vladislav Zubok recounts how the separatist idea gained momentum in the first half of 1990 thanks to three ‘mutually hostile’ forces: Russian nationalists inside the party and elites; the democratic opposition that dominated Moscow politics; and the masses behind Gorbachev’s rival, Yeltsin, a charismatic apparatchik who transformed into the ‘people’s tsar’.

Yeltsin, who was elected the first head of the Russian Supreme Soviet, riled up crowds by declaring that the Soviet Union was stealing from Russians to subsidise Central Asia. ‘Enough feeding the other republics!’ he exclaimed in a speech to industrial workers, who responded with a chant against Gorbachev. Yeltsin called for Russia’s ‘democratic, national, and spiritual resurrection’ and promised to redistribute resources to the people. Though Yeltsin adopted elements of conservative nationalists’ ideas, he was also pro-Western and pushed for further democratisation and marketisation, which they opposed.

In contrast to Yeltsin, Gorbachev dreamed of creating a ‘common European home’ that would include all peoples of the USSR in a closer relationship with the West. By the end of 1990, all of the Soviet republics had responded to the vacuum of central authority and the example set by former Soviet satellites in eastern Europe by declaring themselves sovereign (and in several cases independent). Yet the future shape of their relationship with the union remained unclear, and possibly still compatible with Gorbachev’s vision of a more equal federation.

I n November 1990, Yeltsin travelled to Kyiv as part of a strategy to undermine Gorbachev by building a new union from below based on ‘horizontal’ ties between Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan. Like other political elites at the time, Yeltsin’s use of the word ‘sovereignty’ in his speeches and promotional materials was ambiguous. According to his advisor Gennady Burbulis, Yeltsin was under the heavy influence of Solzhenitsyn’s recently published essay ‘Rebuilding Russia’, which claimed that the Russian people were exhausted, and proposed dissolving the USSR while retaining a Slavic core of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, along with Russian-populated parts of Kazakhstan. Solzhenitsyn’s view that all three of these peoples ‘sprang from precious Kyiv’ was shared by many Russians who did not necessarily identify as nationalists but assumed they would stay together.

Yeltsin’s expectations for a rapprochement with Ukraine were soon disappointed. In August 1991, the Communist hardliners’ failed coup put an end to Gorbachev’s hopes for a revitalised union and consolidated the power of Yeltsin, who was now the first elected president of the RSFSR. The Verkovna Rada, Ukraine’s parliament, passed an act proclaiming an independent state of Ukraine with ‘indivisible and inviolable’ territory. Particularly panicked at the thought of losing Crimea, Yeltsin had his press officer announce that the Russian republic reserved the right to reconsider its borders, angering the Ukrainian leader Leonid Kravchuk. Yeltsin’s administration backtracked and recognised all existing borders, and in December 1991 Yeltsin joined the heads of Ukraine and Belarus in the Belavezha forest to officially dissolve the USSR. Conservative Russian nationalists were outraged by the sudden end of Moscow’s control over the region but, as Zubok notes, it was they who had initially raised the question of Russian sovereignty and opposed Gorbachev when he was struggling to save the union.

The Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev learned about Belavezha only after the fact. Yeltsin thought that Kazakhstan should be part of a new commonwealth of independent states but wanted to keep out the ‘Muslim’ republics of Central Asia. Nazarbayev insisted on their inclusion, and prevailed. According to Adeeb Khalid’s book Central Asia (2021), full independence from the Soviet Union was ‘unexpected and, in many ways, unwanted by both the people and the political elites of Central Asia’. As a supplier of raw materials, the region was ill-served by isolation from the union’s economic structures. However great their enthusiasm for strengthening national identity and autonomy, some politicians and members of the intelligentsia still saw weaker union with Russia as preferable to separation. The surprise dissolution at Belavezha was the final irony of Soviet empire: for peoples seen as inferior, even freedom was dictated by Moscow.

Yeltsin’s administration announced a contest for a new ‘national idea’. It never chose a winner

As other countries in the former Eastern Bloc celebrated a ‘return to Europe’, the fusion of the Russian and the Soviet prevented the creation of a national identity based on casting off an oppressive foreign yoke. Yeltsin expected that Russia would be welcomed into the ‘West’ with a massive aid package and NATO membership. Instead, it was left in the ‘East’ and received meagre humanitarian assistance. After decades of being told that they represented the world’s leading civilisation, Russians were reduced to eating expired US military rations. The Yeltsin administration’s economic ‘shock therapy’, carried out in consultation with Western advisors, brought an atmosphere of brutal lawlessness that enriched a few and impoverished many others. The neoliberal Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs and the Harvard Institute for International Development in Moscow helped design Yeltsin’s market reform and privatisation package, and implement it at dizzying speed. Crime and mortality rates skyrocketed as savings vanished overnight.

Reeling from inflation and shortages, several Russian republics and regions developed sovereignty movements aimed at achieving political and economic advantages over other territories (including Yeltsin’s native Sverdlovsk Oblast, which briefly declared itself the ‘Urals Republic’). These were largely brought to heel by Yeltsin’s December 1993 constitution. The republic of Chechnya, however, pressed for full independence, prompting Yeltsin’s disastrous decision to invade in 1994. The Russian Federation was a web of nationality-based republics, autonomous districts and territorial regions without a unifying concept. In June 1996, Yeltsin’s administration announced a contest to generate a new ‘national idea’. It never chose a winner.

Russian nationalist politicians attempted to turn poverty and disillusionment into votes against Yeltsin. Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a racist and antisemitic provocateur and head of the misleadingly named Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR), argued for the re-establishment of an autocratic Russian state within Soviet-era borders. Gennady Zyuganov’s Communist Party of the Russian Federation offered a Stalinist brand of Russian imperialism influenced by Lev Gumilev’s concept of ‘Eurasianism’. These parties achieved moderate electoral success: LDPR performed well in the 1993 elections, and Zyuganov trailed Yeltsin by only three percentage points in the 1996 presidential race. But most Russians, especially in the younger generation, were more interested in the problems and possibilities of the present (including foreign travel and consumer goods) than chauvinist messianism that looked to the past.

T hrough the 1990s, visions of national disempowerment and revenge gained more traction in Russian popular culture. The lost men of Shukshin’s stories, for example, morphed into action heroes who offered redemptive masculinity through violence. Danila, the protagonist of the hit movies Brother (1997) and Brother 2 (2000), is a young veteran of Yeltsin’s war in Chechnya from a poor provincial town. In an early scene, his grandmother tells Danila he’s a hopeless case and will die in prison like his father. She sends him to Saint Petersburg to be mentored by his big brother, who turns out to be a contract killer for the mafia. Rather than falling victim, Danila becomes an earnest vigilante who hurts the bad guys (especially men from the Caucasus) and protects the weak (poor Russian women and men).

In the sequel, Danila travels to the US to rescue the victims of an evil empire run by American businessmen in cahoots with Chicago’s Ukrainian mafia and ‘new Russians’ in Moscow. Stereotyped Others embody the threats facing the Russian people; in Chicago, he meets a sex worker named Dasha who is controlled by an abusive Black pimp. In the climactic scene, Danila takes revenge by committing a mass shooting at a nightclub in the city’s Ukrainian district. Moral righteousness is clearly on his side: Danila declares his love for the motherland and repeats Second World War-era slogans such as ‘Russians in war don’t abandon their own.’ At the end, he and Dasha drink vodka on a flight back home as the song ‘Goodbye, America’ (sung by a children’s choir) plays in the background. Brother 2 was released in 2000, the year that Vladimir Putin ascended to the presidency.

Putin kept his distance from nationalists, affirming that Russia was part of ‘European culture’ and cooperating with the US invasion of Afghanistan, while maintaining LDPR and the Communists as a loyal opposition in parliament. Like Yeltsin, he selectively incorporated aspects of their ideas, for example, in his decision to bring back the Soviet national anthem. He rejected other Russian nationalist hobby horses, including open racism and antisemitism. The booming oil and gas prices of Putin’s first two terms (2000-08) significantly improved Russians’ quality of life. Putin increasingly espoused the country’s mission as a bastion of traditional values that was ready to seek payback for the indignities of the preceding years.

An ex-convict considers killing a man he feels has humiliated him, but takes his own life instead

Putin’s 2014 annexation of Crimea pushed his approval ratings to record highs among ethnic Russians as well as Tatars, Chechens and other groups in the Russian Federation. Yet public enthusiasm for further expansionism remained limited. In January 2020, a poll by the Levada Center found that 82 per cent of Russians thought that Ukraine should be an independent state. Annual surveys have consistently shown that Russians prefer a higher standard of living to great power status (except in the post-Crimea afterglow of 2014). Now, as Putin tries to channel national aggrievement into support for a full-scale war against the neighbour who was once promised freedom, the late-Soviet case serves as a reminder that resentment is an unpredictable tool. Russians’ sense of pride and victimisation propped up the Soviet empire when Communist orthodoxy lost the power to convince. But it ultimately fuelled claims that imperial ambition came at too high a cost for the Russian people, turning them into a disposable resource.

Shukshin died in the relative torpor of the Soviet 1970s, when a sense of national disorientation wasn’t necessarily hitched to a political programme. His work didn’t idealise a vanishing past or a bright future. There are no scapegoats or saviours, and attempts at revenge end in self-destruction. In Shukshin’s short story ‘Bastard’ (1970), an ex-convict from the countryside considers killing a man he feels has humiliated him, but takes his own life instead. During his final moments, he feels ‘the peace of a lost person who understands he is lost.’

Putin came of age in Shukshin’s heyday and knows of his work. Like the Russian nationalists who once whispered about murder, he has tried to appropriate Shukshin’s memory for his own ends. In November 2014, he made an appearance at a theatre adaptation of Shukshin’s stories in central Moscow. The occasion was the Day of National Unity, an imperial holiday brought back by his administration, marking the expulsion of Polish-Lithuanian forces from the Kremlin in 1612 and the founding of the Romanov dynasty. In his onstage remarks, Putin praised Shukshin for showing ‘a simple man, for this is the essence of Russia.’

‘It’s a shame that Shukshin is no longer with us,’ Putin concluded. ‘But at least we have his heroes.

‘Russia depends on them.’

Stories and literature

On Jewish revenge

What might a people, subjected to unspeakable historical suffering, think about the ethics of vengeance once in power?

Shachar Pinsker

Consciousness and altered states

How perforated squares of trippy blotter paper allowed outlaw chemists and wizard-alchemists to dose the world with LSD

The environment

We need to find a way for human societies to prosper while the planet heals. So far we can’t even think clearly about it

Ville Lähde

Archaeology

Why make art in the dark?

New research transports us back to the shadowy firelight of ancient caves, imagining the minds and feelings of the artists

Izzy Wisher

Do liberal arts liberate?

In Jack London’s novel, Martin Eden personifies debates still raging over the role and purpose of education in American life

Politics and government

India and indigeneity

In a country of such extraordinary diversity, the UN definition of ‘indigenous’ does little more than fuel ethnic violence

Dikshit Sarma Bhagabati

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World History Project - 1750 to the Present

Course: world history project - 1750 to the present > unit 7.

- READ: The Global Story of the 1930s

- READ: Fascism in Germany

- READ: Fascism in Italy

READ: Communism in the Soviet Union

- READ: Authoritarianism in Japan

- READ: Fascist Histories, Part II - Exercising Authoritarianism

- READ: Appeasement

- The Road to War

First read: preview and skimming for gist

Second read: key ideas and understanding content.

- What big challenges did Lenin and the Bolshevik (communist) leadership face in the first stages of their revolution?

- How does the author characterize the Bolshevik party during the early part of their rule?

- How did Stalin’s rise to power change the way the Bolsheviks ruled?

- What were some consequences for everyday life under the Soviet command economy?

- How were fascism and communism under Stalin similar and different?

Third read: evaluating and corroborating

- Communism under Stalin was certainly different from fascism. But Italian Fascism, as you now know, was different from German fascism. Why do we call Mussolini and Hitler’s approaches fascism, but use the term communism for Stalin’s regime?

- Think about the last time you heard someone called a “communist” or a “fascist”. Do you think the term was used correctly?

- In this unit we see the rise of governments that have certain political characteristics. We call these characteristics fascism, authoritarianism, and totalitarianism. Using these definitions, evaluate which of these terms can appropriately be applied to this government. It may be all, some, or none:

- A totalitarian regime has a highly centralized system of government that requires strict obedience.

- An authoritarian regime focuses on the maintenance of order at the expense of personal freedom.

- A fascist regime is a government that embraces extreme nationalism, violence, and action with the goal of internal cleansing and external expansion.

Communism in the Soviet Union

Introduction, the rise of stalin, communism and fascism.

- Both, of course, exhibited an authoritarian impulse to bring the population into line with the aims of the state.

- Both sought to install a totalitarian system that could do as it pleased.

- Both used violence to achieve political ends.

- Both rejected liberalism.

- The fascist “new man” even had a counterpart in the “new Soviet man”. Each was a mythic symbol of their movement’s values.

- The Soviets embraced left-wing socialist internationalism, while fascists embraced right-wing ethnic nationalism.

- The Soviets, in theory at least, rejected the doctrines of racism and ethnic nationalism, while these doctrines were central to fascism.

- Soviet communism wanted to erase class and gender inequalities, while fascists wanted to affirm social and gender hierarchies that limited women to marriage and motherhood and promoted a violent cult of masculinity for men.

- A premier is a head of a government, like a prime minister.

- Collectivization is the idea that, within a state, nothing can be privately owned because everything is meant to be shared with all members of the state.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Linguistics

- Browse content in Literature

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Technology and Society

- Browse content in Law

- Company and Commercial Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Local Government Law

- Criminal Law

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Public International Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Police Regional Planning

- Property Law

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Microbiology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Palaeontology

- Environmental Science

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Browse content in Environment

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Environmental Politics

- International Relations

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Economy

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Russian Politics

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- Native American Studies

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Migration Studies

- Organizations

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

The Rise and Fall of Communism in Russia

- Cite Icon Cite

This book offers a survey of the evolution of the Soviet system and its ideology. In a tightly woven series of analyses written during a career-long inquiry into the Soviet Union, the book explores the Soviet experience from Karl Marx to Boris Yeltsin and shows how key ideological notions were altered as Soviet history unfolded. The book exposes a long history of the United States' misunderstanding of the Soviet Union, leading up to the “grand surprise” of its collapse in 1991. The book's assessments, some worked out years ago, are prescient in the light of post-1991 archival revelations. Soviet Communism evolved and decayed over the decades, the book argues, through a prolonged revolutionary process, combined with the challenges of modernization and the personal struggles between ideologues and power-grabbers.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Russian Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 27, 2024 | Original: March 12, 2024

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was one of the most explosive political events of the 20th century. The violent revolution marked the end of the Romanov dynasty and centuries of Russian Imperial rule. Economic hardship, food shortages and government corruption all contributed to disillusionment with Czar Nicholas II. During the Russian Revolution, the Bolsheviks, led by leftist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, seized power and destroyed the tradition of czarist rule. The Bolsheviks would later become the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

When Was the Russian Revolution?

In 1917, two revolutions swept through Russia, ending centuries of imperial rule and setting into motion political and social changes that would lead to the eventual formation of the Soviet Union .

However, while the two revolutionary events took place within a few short months of 1917, social unrest in Russia had been brewing for many years prior to the events of that year.

In the early 1900s, Russia was one of the most impoverished countries in Europe with an enormous peasantry and a growing minority of poor industrial workers. Much of Western Europe viewed Russia as an undeveloped, backwards society.

The Russian Empire practiced serfdom—a form of feudalism in which landless peasants were forced to serve the land-owning nobility—well into the nineteenth century. In contrast, the practice had disappeared in most of Western Europe by the end of the Middle Ages .

In 1861, the Russian Empire finally abolished serfdom. The emancipation of serfs would influence the events leading up to the Russian Revolution by giving peasants more freedom to organize.

What Caused the Russian Revolution?

The Industrial Revolution gained a foothold in Russia much later than in Western Europe and the United States. When it finally did, around the turn of the 20th century, it brought with it immense social and political changes.

Between 1890 and 1910, for example, the population of major Russian cities such as St. Petersburg and Moscow nearly doubled, resulting in overcrowding and destitute living conditions for a new class of Russian industrial workers.

A population boom at the end of the 19th century, a harsh growing season due to Russia’s northern climate, and a series of costly wars—starting with the Crimean War —created frequent food shortages across the vast empire. Moreover, a famine in 1891-1892 is estimated to have killed up to 400,000 Russians.

The devastating Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 further weakened Russia and the position of ruler Czar Nicholas II . Russia suffered heavy losses of soldiers, ships, money and international prestige in the war, which it ultimately lost.

Many educated Russians, looking at social progress and scientific advancement in Western Europe and North America, saw how growth in Russia was being hampered by the monarchical rule of the czars and the czar’s supporters in the aristocratic class.

Russian Revolution of 1905

Soon, large protests by Russian workers against the monarchy led to the Bloody Sunday massacre of 1905 . Hundreds of unarmed protesters were killed or wounded by the czar’s troops.

The Bloody Sunday massacre sparked the Russian Revolution of 1905, during which angry workers responded with a series of crippling strikes throughout the country. Farm laborers and soldiers joined the cause, leading to the creation of worker-dominated councils called “soviets.”

In one famous incident, the crew of the battleship Potemkin staged a successful mutiny against their overbearing officers. Historians would later refer to the 1905 Russian Revolution as ‘the Great Dress Rehearsal,” as it set the stage for the upheavals to come.

Nicholas II and World War I

After the bloodshed of 1905 and Russia’s humiliating loss in the Russo-Japanese War, Nicholas II promised greater freedom of speech and the formation of a representative assembly, or Duma, to work toward reform.

Russia entered into World War I in August 1914 in support of the Serbs and their French and British allies. Their involvement in the war would soon prove disastrous for the Russian Empire.

Militarily, imperial Russia was no match for industrialized Germany, and Russian casualties were greater than those sustained by any nation in any previous war. Food and fuel shortages plagued Russia as inflation mounted. The already weak economy was hopelessly disrupted by the costly war effort.

Czar Nicholas left the Russian capital of Petrograd (St. Petersburg) in 1915 to take command of the Russian Army front. (The Russians had renamed the imperial city in 1914, because “St. Petersburg” sounded too German.)

Rasputin and the Czarina

In her husband’s absence, Czarina Alexandra—an unpopular woman of German ancestry—began firing elected officials. During this time, her controversial advisor, Grigory Rasputin , increased his influence over Russian politics and the royal Romanov family .

Russian nobles eager to end Rasputin’s influence murdered him on December 30, 1916. By then, most Russians had lost faith in the failed leadership of the czar. Government corruption was rampant, the Russian economy remained backward and Nicholas repeatedly dissolved the Duma , the toothless Russian parliament established after the 1905 revolution, when it opposed his will.

Moderates soon joined Russian radical elements in calling for an overthrow of the hapless czar.

February Revolution

The February Revolution (known as such because of Russia’s use of the Julian calendar until February 1918) began on March 8, 1917 (February 23 on the Julian calendar).

Demonstrators clamoring for bread took to the streets of Petrograd. Supported by huge crowds of striking industrial workers, the protesters clashed with police but refused to leave the streets.

On March 11, the troops of the Petrograd army garrison were called out to quell the uprising. In some encounters, the regiments opened fire, killing demonstrators, but the protesters kept to the streets and the troops began to waver.

The Duma formed a provisional government on March 12. A few days later, Czar Nicholas abdicated the throne, ending centuries of Russian Romanov rule.

Alexander Kerensky

The leaders of the provisional government, including young Russian lawyer Alexander Kerensky, established a liberal program of rights such as freedom of speech, equality before the law, and the right of unions to organize and strike. They opposed violent social revolution.

As minister of war, Kerensky continued the Russian war effort, even though Russian involvement in World War I was enormously unpopular. This further exacerbated Russia’s food supply problems. Unrest continued to grow as peasants looted farms and food riots erupted in the cities.

Bolshevik Revolution

On November 6 and 7, 1917 (or October 24 and 25 on the Julian calendar, which is why the event is often referred to as the October Revolution ), leftist revolutionaries led by Bolshevik Party leader Vladimir Lenin launched a nearly bloodless coup d’état against the Duma’s provisional government.

The provisional government had been assembled by a group of leaders from Russia’s bourgeois capitalist class. Lenin instead called for a Soviet government that would be ruled directly by councils of soldiers, peasants and workers.

The Bolsheviks and their allies occupied government buildings and other strategic locations in Petrograd, and soon formed a new government with Lenin as its head. Lenin became the dictator of the world’s first communist state.

Russian Civil War

Civil War broke out in Russia in late 1917 after the Bolshevik Revolution. The warring factions included the Red and White Armies.

The Red Army fought for the Lenin’s Bolshevik government. The White Army represented a large group of loosely allied forces, including monarchists, capitalists and supporters of democratic socialism.

On July 16, 1918, the Romanovs were executed by the Bolsheviks. The Russian Civil War ended in 1923 with Lenin’s Red Army claiming victory and establishing the Soviet Union.

After many years of violence and political unrest, the Russian Revolution paved the way for the rise of communism as an influential political belief system around the world. It set the stage for the rise of the Soviet Union as a world power that would go head-to-head with the United States during the Cold War .

The Russian Revolutions of 1917. Anna M. Cienciala, University of Kansas . The Russian Revolution of 1917. Daniel J. Meissner, Marquette University . Russian Revolution of 1917. McGill University . Russian Revolution of 1905. Marxists.org . The Russian Revolution of 1905: What Were the Major Causes? Northeastern University . Timeline of the Russian Revolution. British Library .

Photo Galleries

HISTORY Vault: Vladimir Lenin: Voice of Revolution

Called treacherous, deluded and insane, Lenin might have been a historical footnote but for the Russian Revolution, which launched him into the headlines of the 20th century.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Social Sciences

© 2024 Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse LLC . All rights reserved. ISSN: 2153-5760.

Disclaimer: content on this website is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to provide medical or other professional advice. Moreover, the views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of Inquiries Journal or Student Pulse, its owners, staff, contributors, or affiliates.

Home | Current Issue | Blog | Archives | About The Journal | Submissions Terms of Use :: Privacy Policy :: Contact

Need an Account?

Forgot password? Reset your password »

More results...

War Communism

War Communism was the name given to the economic system that existed in Russia from 1918 to 1921. War Communism was introduced by Lenin to combat the economic problems brought on by the civil war in Russia. It was a combination of emergency measures and socialist dogma.

One of the first measures of War Communism was the nationalisation of land . Banks and shipping were also nationalised and foreign trade was declared a state monopoly. This was the response when Lenin realised that the Bolsheviks were simply unprepared to take over the whole economic system of Russia. Lenin stressed the importance of the workers showing discipline and a will to work hard if the revolution was to survive. There were those in the Bolshevik hierarchy who wanted factory managers removed and the workers to take over the factories for themselves but on behalf of the people. It was felt that the workers would work better if they believed they were working for a cause as opposed to a system that made some rich but many poor. The civil war had made many in the Bolsheviks even more class antagonistic, as there were many of the old guard who were fighting to destroy the Bolsheviks.

On June 28th, 1918, a decree was passed that ended all forms of private capitalism. Many large factories were taken over by the state and on November 29th, 1920, any factory/industry that employed over 10 workers was nationalised.

War Communism also took control of the distribution of food. The Food Commissariat was set up to carry out this task. All co-operatives were fused together under this Commissariat.

War Communism had six principles:

1) Production should be run by the state. Private ownership should be kept to the minimum. Private houses were to be confiscated by the state.

2) State control was to be granted over the labour of every citizen. Once a military army had served its purpose, it would become a labour army.

3) The state should produce everything in its own undertakings. The state tried to control the activities of millions of peasants.

4) Extreme centralisation was introduced. The economic life of the area controlled by the Bolsheviks was put into the hands of just a few organisations. The most important one was the Supreme Economic Council. This had the right to confiscate and requisition. The speciality of the SEC was the management of industry. Over 40 head departments (known as glavki) were set up to accomplish this. One glavki could be responsible for thousands of factories. This frequently resulted in chronic inefficiency. The Commissariat of Transport controlled the railways. The Commissariat of Agriculture controlled what the peasants did.

5) The state attempted to become the soul distributor as well as the sole producer. The Commissariats took what they needed to meet demands. The people were divided into four categories – manual workers in harmful trades, workers who performed hard physical labour, workers in light tasks/housewives and professional people. Food was distributed on a 4:3:2:1 ratio. Though the manual class was the favoured class, it still received little food. Many in the professional class simply starved. It is believed that about 0% of all food consumed came from an illegal source. On July 20th 1918, the Bolsheviks decided that all surplus food had to be surrendered to the state. This led to an increase in the supply of grain to the state. From 1917 to 1928, about ¾ million ton was collected by the state. In 1920 to 1921, this had risen to about 6 million tons. However, the policy of having to hand over surplus food caused huge resentment in the countryside, especially as Lenin had promised “all land to the people” pre-November 1917. While the peasants had the land, they had not been made aware that they would have to hand over any extra food they produced from their land. Even the extra could not meet demand. In 1933, 25 million tons of grain was collected and this only just met demand.

6) War Communism attempted to abolish money as a means of exchange. The Bolsheviks wanted to go over to a system of a natural economy in which all transactions were carried out in kind. Effectively, bartering would be introduced. By 1921, the value of the rouble had dropped massively and inflation had markedly increased. The government’s revenue raising ability was chronically poor, as it had abolished most taxes. The only tax allowed was the ‘Extraordinary Revolutionary Tax’, which was targeted at the rich and not the workers.

War Communism was a disaster. In all areas, the economic strength of Russia fell below the 1914 level. Peasant farmers only grew for themselves, as they knew that any extra would be taken by the state. Therefore, the industrial cities were starved of food despite the introduction of the 4:3:2:1 ratio. A bad harvest could be disastrous for the countryside – and even worse for cities. Malnutrition was common, as was disease. Those in the cities believed that their only hope was to move out to the countryside and grow food for themselves. Between 1916 and 1920, the cities of northern and central Russia lost 33% of their population to the countryside. Under War Communism, the number of those working in the factories and mines dropped by 50%.

In the cities, private trade was illegal, but more people were engaged in this than at any other time in Russia’s history. Large factories became paralysed through lack of fuel and skilled labour.

Small factories were in 1920 producing just 43% of their 1913 total. Large factories were producing 18% of their 1913 figure. Coal production was at 27% of its 1913 figure in 1920. With little food to nourish them, it could not be expected that the workers could work effectively. By 1920, the average worker had a productivity rate that was 44% less than the 1913 figure.

Even if anything of value could be produced, the ability to move it around Russia was limited. By the end of 1918, Russia’s rail system was in chaos.

In the countryside, most land was used for the growth of food. Crops such as flax and cotton simply were not grown. Between 1913 and 1920, there was an 87% drop in the number of acres given over to cotton production. Therefore, those factories producing cotton related products were starved of the most basic commodity they needed.

How did the people react to War Communism? Within the cities, many were convinced that their leaders were right and the failings being experienced were the fault of the Whites and international capitalists. There were few strikes during War Communism – though Lenin was quick to have anyone arrested who seemed to be a potential cause of trouble. Those in Bolshevik held territory were also keen to see a Bolshevik victory in the civil war, so they were prepared to do what was necessary. The alternate – a White victory – was unthinkable.

Also the Bolshevik hierarchy could blame a lot of Russia’s troubles on the Whites as they controlled the areas, which would have supplied the factories with produce. The Urals provided Petrograd and Tula with coal and iron for their factories. The Urals was completely separated from Bolshevik Russia from the spring of 1918 to November 1919. Oil fields were in the hands of the Whites. Also the Bolshevik’s Red Army took up the majority of whatever supplies there were in their fight against the Whites.

No foreign country was prepared to trade with the Russia controlled by the Bolsheviks, so foreign trade ceased to exist. Between 1918 and November 1920, the Allies formally blockaded Russia.

The harshness of War Communism could be justified whilst the civil war was going on. When it had finished, there could be no such justification. There were violent rebellions in Tambov and in Siberia. The sailors in Kronstadt mutinied. Lenin faced the very real risk of an uprising of workers and peasants and he needed to show the type of approach to the problem that the tsarist regime was incapable of doing. In February 1921, Lenin had decided to do away with War Communism and replace it with a completely different system – the New Economic Policy . This was put to the 10th Party Conference in March and accepted. War Communism was swept away. During War Communism, the people had no incentive to produce as money had been abolished. They did what needed to be done because of the civil war, but once this had ended Lenin could not use it as an excuse any longer.

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

History Grade 11 - Topic 1 Contextual Overview

What is Communism?

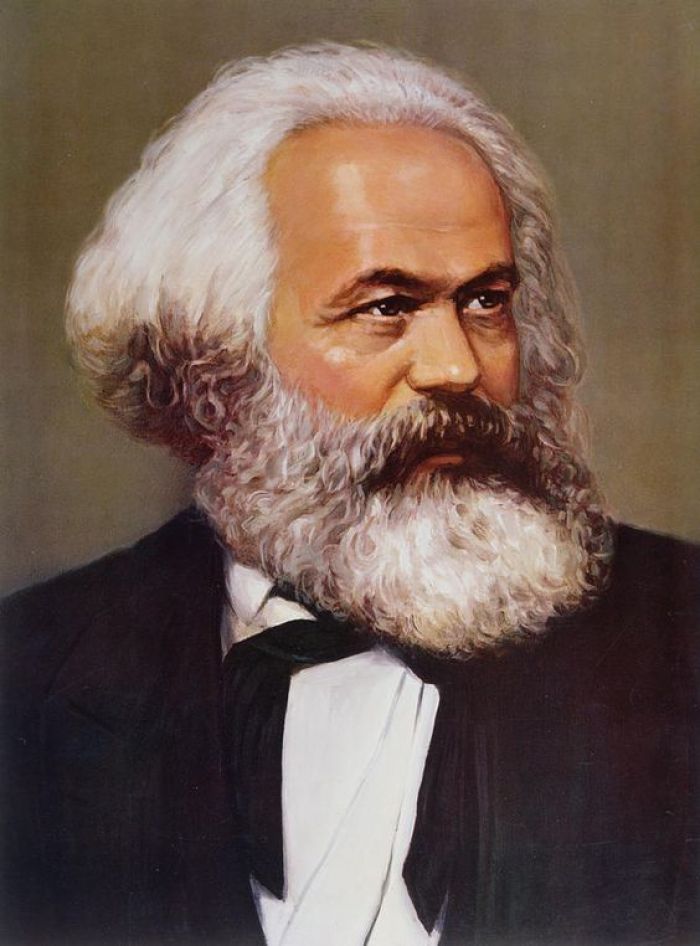

Communism is a social, economic, and political ideology whose aim is to establish a communist society in which there is a collective ownership of the means of production [1] . The goal of communism is to eliminate social classes in society. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels are considered the founding fathers of communism [2] . Communism believes that the current order of society comes from capitalism. Communism views capitalism as a system which mainly consists of class struggles between the proletariat (working class) who make up the majority of the population and the bourgeoise (capitalists), who make profit from exploiting the working class through private ownership of the means of production and they form the minority of the population. Communism believes that through a revolution , the working class could seize power and establish social ownership of the means of production where the main goal would be to transform society into a more equitable one towards communism). Karl Marx was a key figure in conceptualising this ideology.

Karl Marx Writings:

Karl Heinrich Marx was born in Germany (5 May 1818- 14 March 1883) and was an economist, political theorist, and philosopher. Karl Marx became stateless because of his work that mainly consisted of political publications which forced him to live in exile with his wife and children [3] . Marx’s best-known works include the 1848 pamphlet titled The Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital which consisted of 3 volumes of this work. His works have had and continue to have a significant influence on intellectual, economic, and political history.

Marxism is collectively understood as Karl Marx’s criticisms of existing societal arrangements, economic and political systems as well as his offerings of alternative arrangements. Marxists believe that all human civilization has come out of conflict, more specifically, class conflicts. Class conflicts show themselves in the capitalist mode of production. In this mode of production, class conflicts arise from the differences between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The bourgeoisie is better understood as the ruling class that owns and controls the means of production (land) and the proletariat would be the working class that exchange their time and labour for living wages, thus, allowing for production in the capitalist mode of production.

Part of Marx’s predictions around capitalism are that it would produce internal tensions that would lead to its own destruction followed by the replacement of that system by a new communist mode of production. The contradictions under capitalism would drive the proletariat to revolt against the capitalist system in a quest for political power and a classless and communist society categorised by a free association of producers. Marx actively advocated for this ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’, arguing that they (the proletariat) have the power to organise a proletarian revolution that would eventually lead to the capitalist system overthrown and begin to promote economic and political freedoms.

1905 Revolution: Issues that led to the Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905 which was also known as the First Russian Revolution was a time of mass social and political unrest which took place in various parts of the Russian government, some of which were aimed at the government [4] . The unrests took the form of worker strikes, peasant unrest and military rebels who wanted to overthrow the government. These strikes led to many constitutional reforms in Russia such as the establishment of a State Duma , the multi-party system, and the Russian Constitution of 1906.

The 1905 revolution was propelled and fuelled by various causes such as the Russian defeat in the war against Japan which ended in 1905. The revolution was also caused by a growing realisation by many sectors of society for the need for reform in Russia. In addition to this, the revolution was spurred on by newly emancipated peasants who were earning low wages with limited land rights and ownership. Ethnic and national minorities also added to the discontent in Russia as they resented the government because of how it oppressed and discriminated against them such as stripping them of voting rights and limiting their schooling options. Another sector of society were the industrial working class who hated the government for not protecting them and suppressing their voices by banning their strikes and labour unions. University students developed a new consciousness with growing radical ideas to overthrow the government was another major course of the revolution [5] . Collectively these issues created the recipe for the 1905 revolution.

Link between the 1905 and the 1917 revolution including political, economic and social causes:

Following the 1905 revolution, Nicholas 2nd (Russia’s last Emperor) promised the Russian people changes and better living conditions, however, he failed to do this and Russia’s social and economic problems continued. In 1914, Russia entered World War one to support their French and British allies (Wade, 2017) [6] . However, Russia’s involvement in the war became disastrous as their military was inferior to Germanies military which resulted in mass casualties that they had never faced before in previous wars. This war caused food and fuel shortages in Russia which significantly increased inflation which crippled Russia’s economy (Wade, 2017).

Like the 1905 revolution, these conditions in 1917 caused demonstrations for bread and better living conditions by way of mass participation of workers and peasants. Even though authorities opened fire and killed protesters, they continued to protest and gained momentum. Eventually, the revolution brought an end to the Tsarist monarchy on February 1917. This victory saw Trotsky return to Russia and became the leader of the Bolsheviks [7] . Here Trotsky played a pivotal role in the October Revolution where they orchestrated the overthrow of the new provincial government. Following this, Trotsky was appointed the Commissar of foreign affairs in government and played an instrumental role in pulling Russia out of World War one. From 1918-1925 he oversaw the Red Army .

The civil war and war communism:

After establishing peace with Germany, the Soviet state soon saw disgruntlement within itself from dissatisfied sections which did not approve of the radical policies of the Bolsheviks (Raleigh, 2002) [8] . To show their discontent, centres of resistance were formed in southern and Siberian Russia by anti-Communist forces who called themselves the whites who were led by former officers of the tsarist army. The Whites and the Red Army soon waged a civil war which would determine Russians future. By 1920, the communist were the clear victors of the Civil War (Raleigh, 2002). The White Army had been defeated and were divided and had not clear cause which led to their demise.

The Soviets state communists applied control in the economic life of the country by applying extreme measures which became known as war communism (economic policies applied by Bolsheviks during the cold war) [9] . This war communism meant coordinating Russia’s economic resources such as nationalising industry across Russia and rejecting workers control of these factories and brining in experts to run these.

Lenin’s seizure of control of the State:

After the overthrow of the Tsar in 1917, Russia came under the command of a Provisional Government which was against violent social reform and who continued Russia’s involvement in WW1. While this was happening, Lenin began planning a coup d'etat of the Provincial Government (Medvedev, 1979) [10] . His selling point of this overthrow was advancing that workers and peasants should directly rule. This was welcomed by workers and peasants as they demanded immediate change in what became known as the October Revolution . Lenin secretly organised factory workers, peasants and soldiers in a successful coup d'etat which was bloodless (Medvedev, 1979). The Bolsheviks seized power of the government and by extension of the Soviet state and made Lenin the leader of the communist state.

Lenin’s economic policy:

In 1921, Lenin adopted the New Economic Policy (NEP) as a temporary retreat from its previous policy of extreme centralization and doctrinaire socialism. Lenin saw this economic policy as the one that would include a “free-market” and “capitalism”. These are assumed to be subject to state administration, whilst socialized state enterprises would function on a “profit-basis”. [11] In the light of the depressed Russian economy, the NEP and its insistence on market-oriented economic policies were deemed necessary after the Russian Civil War which dated from 1918 to 1922. In this context, the nationalization of industry (formed during the War Communism of 1918-1921) was partially withdrawn by the Soviet authorities and had thus implemented a system of mixed economy. On the one hand, this system allowed private individuals to own small enterprises . On the other hand, the state continued to regulate banks, foreign trade, and large industries . Furthermore, the NEP has dismantled prodrazvyorstka (forced grain-acquisition) and introduced a system known as prodnalog which basically imposed taxes on farmers, payable in the form of raw agricultural product. [12] This allowed them to keep and trade part of their produce. It is argued that, initially, this tax was paid in kind.

Thus, the adoption of the NEP signalled the promulgation of a new agricultural policy. For example, the Bolsheviks saw traditional village as ‘pre-modern’ and ‘backward’. Hence, the NEP only permitted private landholdings because the idea of the collectivized farming met strong backlash. In the light of severe economic conditions in Russia, Lenin’s policies opened up markets to the greater degree of free trade, hoping to lure the large population to increase production. However, James Gregor argues that Lenin’s policies did not only restore private property rights, profits, and a whole range of other capitalist enterprises, but his policies turned to international capitalist markets for support and aid. [13] Lenin had the belief that in order to achieve socialism, he had to create the “missing material prerequisites” of modernization and industrial development that made it possible for Soviet Russia "fall back on a centrally supervised market-influenced program of state capitalism". [14] In this regard, Lenin followed the logic of Marxist vision that a society must first reach the full stage of capitalism as a pre-condition for socialism to be inaugurated. Zickel, Raymond postulates the use of Marxism-Leninism as a concept to describe Lenin’s approach to economic policies which were seen to support policies that paved the way towards the realization of communism. [15] However, the death of Lenin in 1924 brought the NEP to an end.

At the start of the 1930s, Stalin implemented a host of radical that completely changed industrial and agricultural face of the Soviet Union. This came to be known as the Great Turn as Russia moved away from the near-capitalist NEP and instead adopted a command economy. The NEP adopted by Lenin was implemented in order to ensure the survival of the socialist state following seven years of war (World War I, 1914–1917, and the subsequent Civil War, 1917–1921) and had reconstituted the Soviet production to its 1913 levels. However, Stalin and the majority of the Communist party felt that the NEP compromised communist ideals and did not deliver adequate economic performance, and this rendered the policy inadequate to create a socialist state. It was thus believed that the pace of industrialization had to be increased in order to catch up with the west.

In reading these important debates in the history of the Russian revolution, how and where do we position women’s involvement in these male-dominated spaces? The Russian Revolutions of 1917 saw the collapse of the Russian empire – a temporary government and the establishment of the world’s first socialist state under the Bolsheviks. In this regard, explicit comments were made to promote the equality of men and women. It has been an article of faith in history writing in that men in society are considered the legitimate political subject, whilst women remain domesticated, confined to the home, and thus defined outside the domain of politics and economics. There is a clear line demarcated here between the private and the public sphere. The former is understood to be the mere zone of passivity, and thus its primary constituents (women) are rendered as ‘pre-revolutionary’ and ‘pre-political’ subjects in this regard. The latter is assumed to constitute the domain of politics. The experiences of women before the Russian revolution are no exception to these male dominated narratives of ‘formal’ political participation in public life. It was thus believed that the revolution would grant women the decorum to move out of the private realm and enter the public realm as revolutionary subjects.

These ideas underwrote the communist vision of women’s emancipation in Russia and elsewhere in the world. Katie McElvanney’s work complicates this understanding and shows how women’s involvement in the Russian revolution merely put burden on them as they were expected to perform dual duties. On the one hand, they were expected to perform traditional demands of the private sphere i.e., taking care of children and a host of related traditional gender roles. On the other hand, they were expected to be active in the demanding politics of public life. It was mainly urban based, educated, and wealthy women who actively participated in the Russian revolution. As mentioned above, the traditional village life was viewed outside the domain of politics and economics. As a result, towards the end of the 19th century, many women began to migrate to industrial urban cities to work in factories or domestic service. It is in this context; they began to affiliate themselves to the revolutionary movements and furthered the project of women’s liberation.

Lenin’s interpretation of Marxism:

Karl Marx assumed and theorised that the working class would gain a collective class consciousness and be powerful enough because of their numerical advantage and be able to control the most vital sectors of industry to gain social and political power to form a classless and stateless society which was equal (Evans, 1993) [16] . Lenin’s theory can be considered a development of Marx’s theory. Lenin on the other hand had theorised that the minority working class of the Soviet Union could be able to conscientize and inspire peasants and other workers in other countries to seize state power and not abolish the state as in Marx’s analysis and political thinking

Lenin’s government deviated from Marxism temporarily by introducing the New Economic Policy (NEP) which was an economic policy adopted by the government from 1921-1928 which was a temporal retreat from their exclusive centralization and doctrinaire socialism (Richman, 1981) [17] . The NEP replaced war communism as the official economic policy and war communism almost brought the Soviet economy near collapse. The NEP ended gran confiscation and replaced it with a fixed tax and people to own small businesses and allowed them to sell surplus goods which meant a return of market (Richman, 1981).

Women and the Russian revolution:

In 1905 the young Russian feminist movement were delighted by the uprising of 1905 which was followed by a loosening of some of the restrictions that women were subjected to and the creation of the national parliament. In 1908, there was a pushback to this and feminists had to retreat (Ruthchild & Goldberg, 2007) [18] . This meant that women were not allowed in institutions of higher learning and moral among liberal forces was low.

However, the outbreak of the war in August in 1914 came as a surprise and as a result the Empire was not adequately prepared for this. While men enrolled into the army, millions of women assumed new roles which were vacated by the men. Industrial centres saw a significant increase from 1914 to 1917. Women were assuming work roles and came out of domesticated roles as peasant women also took new roles taking over some of their husbands’ farm work. Some women fought directly in the war often disguised as men and thousands more served as nurses. These new roles women assumes during the war affected the subsequent roles women would play in the coming revolutions.

Following the collapse of the Provisional Government, the Bolsheviks created the world’s first socialist state. The Bolsheviks made conscious and explicit commitments to promote the equality of men and women. Even before this, many Russian working women and feminists actively participated in the war and were affected by the events of the war and thus were included in the new policies of the new government. The Bolsheviks advocated for liberalism and made Russia one of the first countries to allow women to vote. Amongst the laws the Bolsheviks implemented that liberated women were: liberalizing laws on divorce and abortion. decriminalising homosexuality and giving women a higher status in society.

The role of the Bolsheviks Government in changing the lives of women: