- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.6: Essay Type- Comparing and Contrasting Literature

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 101138

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Compare and Contrast Essay Basics

The Compare and Contrast Essay is a literary analysis essay, but, instead of examining one work, it examines two or more works. These works must be united by a common theme or thesis statement. For example, while a literary analysis essay might explore the significance of ghosts in William Shakespeare's Hamlet, a compare/contrast essay might explore the significance of the supernatural in Hamlet and Macbeth .

Literary Analysis Thesis Statement:

While Horatio seems to think the ghost of Old Hamlet is a demon trying to lead Hamlet to death, and Gertrude and Claudius think it is a figment of Hamlet's insanity, Hamlet's status as an unreliable narrator and the ghost actually symbolizes the oppression of Catholics during Shakespeare's time period.

Compare and Contrast Thesis Statement:

The unreliable narrators paired with the ghosts in both Hamlet and Macbeth symbolize the oppression of Catholics in Shakespeare's time period.

Essay Genre Expectations

- Use first-person pronouns sparingly (you, me, we, our)

- Avoid colloquialisms

- Spell out contractions

- Use subject-specific terminology, such as naming literary devices

- Texts: two or more

- Avoid summary. Aim for analysis and interpretation

- MLA formatting and citations

Organization

While the literary analysis essay follows a fairly simple argumentative essay structure, the compare and contrast essay is slightly more complicated. It might be arranged by:

- Literary work (the block method)

- Topics/subtopics (the point-by-point method)

In general, ensure each paragraph supports the thesis statement and that both literary works receive equal attention. Include as many body paragraphs as needed to build your argument.

First Option for Organization: The Block Method

In this first option for organization, you will need to discuss both literary works in the introduction and thesis statement, but then the body of the paper will be divided in half. The first half of the body paragraphs should focus on one literary work, while the second half of the body paragraphs should focus on the other literary work.

- Background of topic

- Background of works related to topic

- Thesis Statement

- Topic sentence

- Introduction of evidence

- Evidence from the first literary work

- Explanation of evidence

- Analysis of evidence

- Evidence from the second literary work

- Restatement of thesis in new words

- Summary of essay arguments

Second Option for Organization: The Point-by-Point Method

With this second option for organization, you may decide to write about both literary works within the same body paragraph every time, or you may choose to consistently alternate back and forth between the literary works in separate body paragraphs.

- Evidence from both literary works

Comparing and Contrasting

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you first to determine whether a particular assignment is asking for comparison/contrast and then to generate a list of similarities and differences, decide which similarities and differences to focus on, and organize your paper so that it will be clear and effective. It will also explain how you can (and why you should) develop a thesis that goes beyond “Thing A and Thing B are similar in many ways but different in others.”

Introduction

In your career as a student, you’ll encounter many different kinds of writing assignments, each with its own requirements. One of the most common is the comparison/contrast essay, in which you focus on the ways in which certain things or ideas—usually two of them—are similar to (this is the comparison) and/or different from (this is the contrast) one another. By assigning such essays, your instructors are encouraging you to make connections between texts or ideas, engage in critical thinking, and go beyond mere description or summary to generate interesting analysis: when you reflect on similarities and differences, you gain a deeper understanding of the items you are comparing, their relationship to each other, and what is most important about them.

Recognizing comparison/contrast in assignments

Some assignments use words—like compare, contrast, similarities, and differences—that make it easy for you to see that they are asking you to compare and/or contrast. Here are a few hypothetical examples:

- Compare and contrast Frye’s and Bartky’s accounts of oppression.

- Compare WWI to WWII, identifying similarities in the causes, development, and outcomes of the wars.

- Contrast Wordsworth and Coleridge; what are the major differences in their poetry?

Notice that some topics ask only for comparison, others only for contrast, and others for both.

But it’s not always so easy to tell whether an assignment is asking you to include comparison/contrast. And in some cases, comparison/contrast is only part of the essay—you begin by comparing and/or contrasting two or more things and then use what you’ve learned to construct an argument or evaluation. Consider these examples, noticing the language that is used to ask for the comparison/contrast and whether the comparison/contrast is only one part of a larger assignment:

- Choose a particular idea or theme, such as romantic love, death, or nature, and consider how it is treated in two Romantic poems.

- How do the different authors we have studied so far define and describe oppression?

- Compare Frye’s and Bartky’s accounts of oppression. What does each imply about women’s collusion in their own oppression? Which is more accurate?

- In the texts we’ve studied, soldiers who served in different wars offer differing accounts of their experiences and feelings both during and after the fighting. What commonalities are there in these accounts? What factors do you think are responsible for their differences?

You may want to check out our handout on understanding assignments for additional tips.

Using comparison/contrast for all kinds of writing projects

Sometimes you may want to use comparison/contrast techniques in your own pre-writing work to get ideas that you can later use for an argument, even if comparison/contrast isn’t an official requirement for the paper you’re writing. For example, if you wanted to argue that Frye’s account of oppression is better than both de Beauvoir’s and Bartky’s, comparing and contrasting the main arguments of those three authors might help you construct your evaluation—even though the topic may not have asked for comparison/contrast and the lists of similarities and differences you generate may not appear anywhere in the final draft of your paper.

Discovering similarities and differences

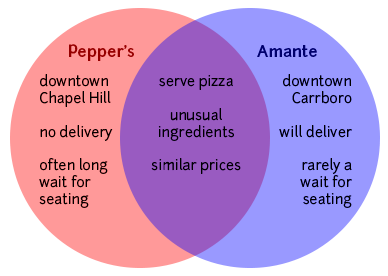

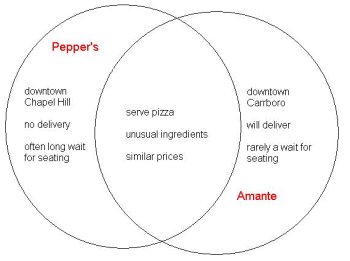

Making a Venn diagram or a chart can help you quickly and efficiently compare and contrast two or more things or ideas. To make a Venn diagram, simply draw some overlapping circles, one circle for each item you’re considering. In the central area where they overlap, list the traits the two items have in common. Assign each one of the areas that doesn’t overlap; in those areas, you can list the traits that make the things different. Here’s a very simple example, using two pizza places:

To make a chart, figure out what criteria you want to focus on in comparing the items. Along the left side of the page, list each of the criteria. Across the top, list the names of the items. You should then have a box per item for each criterion; you can fill the boxes in and then survey what you’ve discovered.

Here’s an example, this time using three pizza places:

As you generate points of comparison, consider the purpose and content of the assignment and the focus of the class. What do you think the professor wants you to learn by doing this comparison/contrast? How does it fit with what you have been studying so far and with the other assignments in the course? Are there any clues about what to focus on in the assignment itself?

Here are some general questions about different types of things you might have to compare. These are by no means complete or definitive lists; they’re just here to give you some ideas—you can generate your own questions for these and other types of comparison. You may want to begin by using the questions reporters traditionally ask: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? If you’re talking about objects, you might also consider general properties like size, shape, color, sound, weight, taste, texture, smell, number, duration, and location.

Two historical periods or events

- When did they occur—do you know the date(s) and duration? What happened or changed during each? Why are they significant?

- What kinds of work did people do? What kinds of relationships did they have? What did they value?

- What kinds of governments were there? Who were important people involved?

- What caused events in these periods, and what consequences did they have later on?

Two ideas or theories

- What are they about?

- Did they originate at some particular time?

- Who created them? Who uses or defends them?

- What is the central focus, claim, or goal of each? What conclusions do they offer?

- How are they applied to situations/people/things/etc.?

- Which seems more plausible to you, and why? How broad is their scope?

- What kind of evidence is usually offered for them?

Two pieces of writing or art

- What are their titles? What do they describe or depict?

- What is their tone or mood? What is their form?

- Who created them? When were they created? Why do you think they were created as they were? What themes do they address?

- Do you think one is of higher quality or greater merit than the other(s)—and if so, why?

- For writing: what plot, characterization, setting, theme, tone, and type of narration are used?

- Where are they from? How old are they? What is the gender, race, class, etc. of each?

- What, if anything, are they known for? Do they have any relationship to each other?

- What are they like? What did/do they do? What do they believe? Why are they interesting?

- What stands out most about each of them?

Deciding what to focus on

By now you have probably generated a huge list of similarities and differences—congratulations! Next you must decide which of them are interesting, important, and relevant enough to be included in your paper. Ask yourself these questions:

- What’s relevant to the assignment?

- What’s relevant to the course?

- What’s interesting and informative?

- What matters to the argument you are going to make?

- What’s basic or central (and needs to be mentioned even if obvious)?

- Overall, what’s more important—the similarities or the differences?

Suppose that you are writing a paper comparing two novels. For most literature classes, the fact that they both use Caslon type (a kind of typeface, like the fonts you may use in your writing) is not going to be relevant, nor is the fact that one of them has a few illustrations and the other has none; literature classes are more likely to focus on subjects like characterization, plot, setting, the writer’s style and intentions, language, central themes, and so forth. However, if you were writing a paper for a class on typesetting or on how illustrations are used to enhance novels, the typeface and presence or absence of illustrations might be absolutely critical to include in your final paper.

Sometimes a particular point of comparison or contrast might be relevant but not terribly revealing or interesting. For example, if you are writing a paper about Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” and Coleridge’s “Frost at Midnight,” pointing out that they both have nature as a central theme is relevant (comparisons of poetry often talk about themes) but not terribly interesting; your class has probably already had many discussions about the Romantic poets’ fondness for nature. Talking about the different ways nature is depicted or the different aspects of nature that are emphasized might be more interesting and show a more sophisticated understanding of the poems.

Your thesis

The thesis of your comparison/contrast paper is very important: it can help you create a focused argument and give your reader a road map so they don’t get lost in the sea of points you are about to make. As in any paper, you will want to replace vague reports of your general topic (for example, “This paper will compare and contrast two pizza places,” or “Pepper’s and Amante are similar in some ways and different in others,” or “Pepper’s and Amante are similar in many ways, but they have one major difference”) with something more detailed and specific. For example, you might say, “Pepper’s and Amante have similar prices and ingredients, but their atmospheres and willingness to deliver set them apart.”

Be careful, though—although this thesis is fairly specific and does propose a simple argument (that atmosphere and delivery make the two pizza places different), your instructor will often be looking for a bit more analysis. In this case, the obvious question is “So what? Why should anyone care that Pepper’s and Amante are different in this way?” One might also wonder why the writer chose those two particular pizza places to compare—why not Papa John’s, Dominos, or Pizza Hut? Again, thinking about the context the class provides may help you answer such questions and make a stronger argument. Here’s a revision of the thesis mentioned earlier:

Pepper’s and Amante both offer a greater variety of ingredients than other Chapel Hill/Carrboro pizza places (and than any of the national chains), but the funky, lively atmosphere at Pepper’s makes it a better place to give visiting friends and family a taste of local culture.

You may find our handout on constructing thesis statements useful at this stage.

Organizing your paper

There are many different ways to organize a comparison/contrast essay. Here are two:

Subject-by-subject

Begin by saying everything you have to say about the first subject you are discussing, then move on and make all the points you want to make about the second subject (and after that, the third, and so on, if you’re comparing/contrasting more than two things). If the paper is short, you might be able to fit all of your points about each item into a single paragraph, but it’s more likely that you’d have several paragraphs per item. Using our pizza place comparison/contrast as an example, after the introduction, you might have a paragraph about the ingredients available at Pepper’s, a paragraph about its location, and a paragraph about its ambience. Then you’d have three similar paragraphs about Amante, followed by your conclusion.

The danger of this subject-by-subject organization is that your paper will simply be a list of points: a certain number of points (in my example, three) about one subject, then a certain number of points about another. This is usually not what college instructors are looking for in a paper—generally they want you to compare or contrast two or more things very directly, rather than just listing the traits the things have and leaving it up to the reader to reflect on how those traits are similar or different and why those similarities or differences matter. Thus, if you use the subject-by-subject form, you will probably want to have a very strong, analytical thesis and at least one body paragraph that ties all of your different points together.

A subject-by-subject structure can be a logical choice if you are writing what is sometimes called a “lens” comparison, in which you use one subject or item (which isn’t really your main topic) to better understand another item (which is). For example, you might be asked to compare a poem you’ve already covered thoroughly in class with one you are reading on your own. It might make sense to give a brief summary of your main ideas about the first poem (this would be your first subject, the “lens”), and then spend most of your paper discussing how those points are similar to or different from your ideas about the second.

Point-by-point

Rather than addressing things one subject at a time, you may wish to talk about one point of comparison at a time. There are two main ways this might play out, depending on how much you have to say about each of the things you are comparing. If you have just a little, you might, in a single paragraph, discuss how a certain point of comparison/contrast relates to all the items you are discussing. For example, I might describe, in one paragraph, what the prices are like at both Pepper’s and Amante; in the next paragraph, I might compare the ingredients available; in a third, I might contrast the atmospheres of the two restaurants.

If I had a bit more to say about the items I was comparing/contrasting, I might devote a whole paragraph to how each point relates to each item. For example, I might have a whole paragraph about the clientele at Pepper’s, followed by a whole paragraph about the clientele at Amante; then I would move on and do two more paragraphs discussing my next point of comparison/contrast—like the ingredients available at each restaurant.

There are no hard and fast rules about organizing a comparison/contrast paper, of course. Just be sure that your reader can easily tell what’s going on! Be aware, too, of the placement of your different points. If you are writing a comparison/contrast in service of an argument, keep in mind that the last point you make is the one you are leaving your reader with. For example, if I am trying to argue that Amante is better than Pepper’s, I should end with a contrast that leaves Amante sounding good, rather than with a point of comparison that I have to admit makes Pepper’s look better. If you’ve decided that the differences between the items you’re comparing/contrasting are most important, you’ll want to end with the differences—and vice versa, if the similarities seem most important to you.

Our handout on organization can help you write good topic sentences and transitions and make sure that you have a good overall structure in place for your paper.

Cue words and other tips

To help your reader keep track of where you are in the comparison/contrast, you’ll want to be sure that your transitions and topic sentences are especially strong. Your thesis should already have given the reader an idea of the points you’ll be making and the organization you’ll be using, but you can help them out with some extra cues. The following words may be helpful to you in signaling your intentions:

- like, similar to, also, unlike, similarly, in the same way, likewise, again, compared to, in contrast, in like manner, contrasted with, on the contrary, however, although, yet, even though, still, but, nevertheless, conversely, at the same time, regardless, despite, while, on the one hand … on the other hand.

For example, you might have a topic sentence like one of these:

- Compared to Pepper’s, Amante is quiet.

- Like Amante, Pepper’s offers fresh garlic as a topping.

- Despite their different locations (downtown Chapel Hill and downtown Carrboro), Pepper’s and Amante are both fairly easy to get to.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

EL Education Curriculum

You are here.

- ELA G5:M2:U2:L3

Reading Literary Texts: Comparing Figurative Language

In this lesson, daily learning targets, ongoing assessment.

- Technology and Multimedia

Supporting English Language Learners

Universal design for learning, closing & assessments, you are here:.

- ELA Grade 5

- ELA G5:M2:U2

Like what you see?

Order printed materials, teacher guides and more.

How to order

Help us improve!

Tell us how the curriculum is working in your classroom and send us corrections or suggestions for improving it.

Leave feedback

These are the CCS Standards addressed in this lesson:

- RL.5.1: Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

- RL.5.4: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative language such as metaphors and similes.

- RL.5.9: Compare and contrast stories in the same genre (e.g., mysteries and adventure stories) on their approaches to similar themes and topics.

- W.5.2: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly.

- W.5.9: Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

- W.5.9a: Apply grade 5 Reading standards to literature (e.g., "Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, or events in a story or a drama, drawing on specific details in the text [e.g., how characters interact]").

- SL.5.1: Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade 5 topics and texts , building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly.

- SL.5.1b: Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions and carry out assigned roles.

- L.5.2: Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English capitalization, punctuation, and spelling when writing.

- L.5.2d: Use underlining, quotation marks, or italics to indicate titles of works.

- L.5.5: Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings.

- L.5.5a: Interpret figurative language, including similes and metaphors, in context.

- L.5.5b: Recognize and explain the meaning of common idioms, adages, and proverbs.

- I can recognize and explain the meaning of similes, metaphors, and idioms in a text. ( RL.5.4, L.5.5a, L.5.5b )

- I can write a paragraph explaining the similarities of the use of figurative language in two literary texts about the rainforest. ( RL.5.1, RL.5.4, RL.5.9, W.5.2, W.5.9a, L.5.2d, L.5.5a, L.5.5b )

- Venn Diagram: Figurative Language graphic organizer ( RL.5.4, RL.5.9, L.5.5a, L.5.5b )

- Comparison Paragraph frame ( RL.5.1, RL.5.4, RL.5.9, W.5.2, W.5.9a, L.5.2d, L.5.5a, L.5.5b )

- Strategically group students for partner work in Work Times A and B.

- Review the Back-to-Back and Face-to-Face, Think-Pair-Share, and Red Light, Green Light protocols. See Classroom Protocols.

- Prepare red, yellow and green objects, for example colored cardstock, one of each color per student.

- Post: Learning targets and Working to Become Effective Learners anchor chart.

Tech and Multimedia

- Work Time A: Digital Venn diagram: Allow students to create the Venn Diagram graphic organizer using Google Docs or other word processing software to refer to when working on their writing outside of class.

- Work Time B: Allow students to type their comparison paragraph using Google Docs or other word processing software.

- Work Times A and B: Students complete their graphic organizers and write their paragraphs in a word processing document, for example a Google Doc using Speech to Text facilities activated on devices, or using an app or software like Dictation.io .

Supports guided by in part by CA ELD Standards 5.I.A.1, 5.I.A.3, 5.I.B.6, 5.I.B.7, 5.I.B.8, 5.I.C.10a, 5.I.C.12a, 5.II.A.1, 5.II.C.6

Important points in the lesson itself

- The basic design of this lesson supports ELLs with opportunities to practice identifying and discussing figurative language, including examples in their home language; use graphic organizers to analyze evidence; and work with a partner to complete a detailed paragraph frame that clarifies expectations of what students should write.

- ELLs may find the volume of unfamiliar language challenging. Though students have been previously exposed to the quotes and texts in this lesson, ELLs may still be largely unfamiliar with the meaning of the language. Help narrow their focus by referring them back to quotes and text they have worked with more extensively, such as the sentence in the Language Dive. If they can start by properly applying one or two pieces of evidence from the texts, they will make excellent progress.

- In Work Time A, ELLs are invited to participate in the second of a series of two connected Language Dive conversations. This second conversation guides them through expanding the meaning of the metaphor in the mystery quote they discussed in Lesson 2. It also provides students with further practice using the language structure from the mystery quote. Students may draw on this sentence when writing about the use of concrete language and sensory detail later in the unit. Preview the Language Dive Guide and consider how to invite conversation among students to address the questions and goals suggested under each sentence strip chunk (see supporting materials). Select from the questions and goals provided to best meet your students' needs.

Levels of support

For lighter support:

- Invite students to continue their Lesson 2 play with the Language Dive sentence and evaluate which versions are most effective, and why.

For heavier support:

- Consider writing the answers from the Venn Diagram: Figurative Language graphic organizer (example, for teacher reference) on separate sticky notes. Invite students to paste the notes into the proper place on a blank Venn diagram.

- In preparation for the Mid-Unit 2 Assessment, provide students with sentence frames and practice to answer the following questions about metaphors:

"What two things are being compared in this simile or metaphor?"

"How does this simile or metaphor help you understand the meaning of the text?"

- Multiple Means of Representation: Some students may need additional support for the abstract thinking required by the figurative language work in this lesson. Consider ways to activate students' background knowledge of figurative language to help them access the learning goals of this lesson. This will help them to generalize skills across lessons and in their own independent reading. This is particularly important because the next lesson includes the mid-unit assessment.

- Multiple Means of Action and Expression: Students demonstrate their learning about figurative language in the Venn diagram activity as well as the partner paragraph writing. Use strategies that will reduce barriers to help students demonstrate their level of comfort with figurative language. Examples:

- Supply sentence starters to help students organize their thoughts before they write them in the Venn diagram.

- Consider varied methods for them to express their thoughts in the Venn diagram (e.g., sticky notes, sketching, etc.).

- Multiple Means of Engagement: Build on the generalization skills promoted through multiple means of representation in the Closing when students reflect on their learning in preparation for the assessment. Students may feel uneasy about sharing their comfort level about the learning targets, so continue to create a supportive and accepting classroom atmosphere. Emphasize that some students will have different comfort levels with different learning targets and that is okay.

Key: Lesson-Specific Vocabulary (L); Text-Specific Vocabulary (T); Vocabulary Used in Writing (W)

- figurative language, simile, metaphor, idiom, similarities, topic sentence, conclusion sentence, context, evidence, concluding sentence (L)

- although, understand, similarly (W)

- Research reading texts (one per student)

- Explaining Quotes: Figurative Language note-catcher (from Lesson 2; one per student and one to display)

- Language Dive Guide II: Part 2 (for ELLs; for teacher reference)

- Language Dive note-catcher II (for ELLs; from Lesson 2; one per student and one to display)

- Sentence strip chunks II (for ELLs; from Lesson 2; one to display)

- Venn Diagram: Figurative Language graphic organizer (one per student and one to display)

- "The Dreaming Tree" (from Lesson 1; one per student)

- The Great Kapok Tree (one to display; for teacher read-aloud)

- The Most Beautiful Roof in the World (one per student)

- Venn Diagram: Figurative Language graphic organizer (example, for teacher reference)

- Comparison Paragraph frame (one per student and one to display)

- Working to Become Effective Learners anchor chart (begun in Module 1)

- Comparison Paragraph frame (example, for teacher reference)

- Red, yellow, and green objects (one of each color per student)

Each unit in the 3-5 Language Arts Curriculum has two standards-based assessments built in, one mid-unit assessment and one end of unit assessment. The module concludes with a performance task at the end of Unit 3 to synthesize their understanding of what they accomplished through supported, standards-based writing.

Copyright © 2013-2024 by EL Education, New York, NY.

Get updates about our new K-5 curriculum as new materials and tools debut.

Help us improve our curriculum..

Tell us what’s going well, share your concerns and feedback.

Terms of use . To learn more about EL Education, visit eleducation.org

compare and contrast 2 texts

All Formats

Resource types, all resource types.

- Rating Count

- Price (Ascending)

- Price (Descending)

- Most Recent

Compare and contrast 2 texts

Compare and Contrast Graphic Organizers, Passages Two Texts 2nd Grade RI. 2 .9

- Google Apps™

- Easel Activity

Paired Passages Compare and Contrast Two Texts Social Media

Compare & Contrast Nonfiction Text - Activities, Passages, Worksheets, 2 Texts

Compare and Contrast Two Texts on the Same Topic Non Fiction Paired Passages

Compare & Contrast 2 Texts on Same Topic, Graphic Organizers, Passages RI.3.9

Compare and Contrast Fiction Texts - Comparing Characters, Stories, Two Texts

Compare and Contrast Two Texts on the Same Topic: Practice and Assessment

Paired Passages PowerPoint Lesson: Compare and Contrast Two Texts

Compare and Contrast Two Texts (RI. 2 .9 and RI.3.9)

RI 2 .9 Compare & Contrast Texts No Prep Tasks for Instruction and Assessment

RI.3.9 Compare and Contrast Two Informational Texts 3rd Grade Compare & Contrast

- Internet Activities

Compare and Contrast Two Texts Multiple Choice 3rd 4th Grade - RL.3.9, RL.4.9

RI. 2 .9 Compare and Contrast Two Texts on the Same Topic- Jackie Robinson

STAAR Paired Passages Task Cards Compare & Contrast Two Text on the Same Topic

Compare and Contrast Task Cards # 2 Tier Two Words Fiction and Informational text

Compare and Contrast Two Texts on the Same Topic

Compare and Contrast Two Texts On The Same Topic, Graphic Organizers, Passages

STAAR Compare & Contrast Two Text on the Same Topic Warm Up Activity Paired

RI 3.9 PowerPoint: Compare and Contrast Two Texts

Compare and Contrast Two Texts on the Same Topic Fiction and Informational Text

Compare & Contrast Two Informational Texts Task Cards +Digital

Close Reading - Compare and Contrast Two Texts FREEBIE (RI. 2 .9, RI.3.9)

4RI.9 Compare and Contrasts Two Texts on the Same Topic

Compare and Contrast 2 Fiction Texts Snowball Fight - Compare Texts Fun

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

Essay Composition

Comparing and contrasting, what this handout is about.

This handout will help you first to determine whether a particular assignment is asking for comparison/contrast and then to generate a list of similarities and differences, decide which similarities and differences to focus on, and organize your paper so that it will be clear and effective. It will also explain how you can (and why you should) develop a thesis that goes beyond “Thing A and Thing B are similar in many ways but different in others.”

Introduction

In your career as a student, you’ll encounter many different kinds of writing assignments, each with its own requirements. One of the most common is the comparison/contrast essay, in which you focus on the ways in which certain things or ideas—usually two of them—are similar to (this is the comparison) and/or different from (this is the contrast) one another. By assigning such essays, your instructors are encouraging you to make connections between texts or ideas, engage in critical thinking, and go beyond mere description or summary to generate interesting analysis: when you reflect on similarities and differences, you gain a deeper understanding of the items you are comparing, their relationship to each other, and what is most important about them.

Recognizing comparison/contrast in assignments

Some assignments use words—like compare, contrast, similarities, and differences—that make it easy for you to see that they are asking you to compare and/or contrast. Here are a few hypothetical examples:

- Compare and contrast Frye’s and Bartky’s accounts of oppression.

- Compare WWI to WWII, identifying similarities in the causes, development, and outcomes of the wars.

- Contrast Wordsworth and Coleridge; what are the major differences in their poetry?

Notice that some topics ask only for comparison, others only for contrast, and others for both.

But it’s not always so easy to tell whether an assignment is asking you to include comparison/contrast. And in some cases, comparison/contrast is only part of the essay—you begin by comparing and/or contrasting two or more things and then use what you’ve learned to construct an argument or evaluation. Consider these examples, noticing the language that is used to ask for the comparison/contrast and whether the comparison/contrast is only one part of a larger assignment:

- Choose a particular idea or theme, such as romantic love, death, or nature, and consider how it is treated in two Romantic poems.

- How do the different authors we have studied so far define and describe oppression?

- Compare Frye’s and Bartky’s accounts of oppression. What does each imply about women’s collusion in their own oppression? Which is more accurate?

- In the texts we’ve studied, soldiers who served in different wars offer differing accounts of their experiences and feelings both during and after the fighting. What commonalities are there in these accounts? What factors do you think are responsible for their differences?

You may want to check out our handout on Understanding Assignments for additional tips.

Using comparison/contrast for all kinds of writing projects

Sometimes you may want to use comparison/contrast techniques in your own pre-writing work to get ideas that you can later use for an argument, even if comparison/contrast isn’t an official requirement for the paper you’re writing. For example, if you wanted to argue that Frye’s account of oppression is better than both de Beauvoir’s and Bartky’s, comparing and contrasting the main arguments of those three authors might help you construct your evaluation—even though the topic may not have asked for comparison/contrast and the lists of similarities and differences you generate may not appear anywhere in the final draft of your paper.

Discovering similarities and differences

Making a Venn diagram or a chart can help you quickly and efficiently compare and contrast two or more things or ideas. To make a Venn diagram, simply draw some overlapping circles, one circle for each item you’re considering. In the central area where they overlap, list the traits the two items have in common. Assign each one of the areas that doesn’t overlap; in those areas, you can list the traits that make the things different. Here’s a very simple example, using two pizza places:

To make a chart, figure out what criteria you want to focus on in comparing the items. Along the left side of the page, list each of the criteria. Across the top, list the names of the items. You should then have a box per item for each criterion; you can fill the boxes in and then survey what you’ve discovered. Here’s an example, this time using three pizza places:

As you generate points of comparison, consider the purpose and content of the assignment and the focus of the class. What do you think the professor wants you to learn by doing this comparison/contrast? How does it fit with what you have been studying so far and with the other assignments in the course? Are there any clues about what to focus on in the assignment itself?

Here are some general questions about different types of things you might have to compare. These are by no means complete or definitive lists; they’re just here to give you some ideas—you can generate your own questions for these and other types of comparison. You may want to begin by using the questions reporters traditionally ask: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? If you’re talking about objects, you might also consider general properties like size, shape, color, sound, weight, taste, texture, smell, number, duration, and location.

Two historical periods or events

- When did they occur—do you know the date(s) and duration? What happened or changed during each? Why are they significant?

- What kinds of work did people do? What kinds of relationships did they have? What did they value?

- What kinds of governments were there? Who were important people involved?

- What caused events in these periods, and what consequences did they have later on?

Two ideas or theories

- What are they about?

- Did they originate at some particular time?

- Who created them? Who uses or defends them?

- What is the central focus, claim, or goal of each? What conclusions do they offer?

- How are they applied to situations/people/things/etc.?

- Which seems more plausible to you, and why? How broad is their scope?

- What kind of evidence is usually offered for them?

Two pieces of writing or art

- What are their titles? What do they describe or depict?

- What is their tone or mood? What is their form?

- Who created them? When were they created? Why do you think they were created as they were? What themes do they address?

- Do you think one is of higher quality or greater merit than the other(s)—and if so, why?

- For writing: what plot, characterization, setting, theme, tone, and type of narration are used?

- Where are they from? How old are they? What is the gender, race, class, etc. of each?

- What, if anything, are they known for? Do they have any relationship to each other?

- What are they like? What did/do they do? What do they believe? Why are they interesting?

- What stands out most about each of them?

Deciding what to focus on

By now you have probably generated a huge list of similarities and differences—congratulations! Next you must decide which of them are interesting, important, and relevant enough to be included in your paper. Ask yourself these questions:

- What’s relevant to the assignment?

- What’s relevant to the course?

- What’s interesting and informative?

- What matters to the argument you are going to make?

- What’s basic or central (and needs to be mentioned even if obvious)?

- Overall, what’s more important—the similarities or the differences?

Suppose that you are writing a paper comparing two novels. For most literature classes, the fact that they both use Calson type (a kind of typeface, like the fonts you may use in your writing) is not going to be relevant, nor is the fact that one of them has a few illustrations and the other has none; literature classes are more likely to focus on subjects like characterization, plot, setting, the writer’s style and intentions, language, central themes, and so forth. However, if you were writing a paper for a class on typesetting or on how illustrations are used to enhance novels, the typeface and presence or absence of illustrations might be absolutely critical to include in your final paper.

Sometimes a particular point of comparison or contrast might be relevant but not terribly revealing or interesting. For example, if you are writing a paper about Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” and Coleridge’s “Frost at Midnight,” pointing out that they both have nature as a central theme is relevant (comparisons of poetry often talk about themes) but not terribly interesting; your class has probably already had many discussions about the Romantic poets’ fondness for nature. Talking about the different ways nature is depicted or the different aspects of nature that are emphasized might be more interesting and show a more sophisticated understanding of the poems.

Your thesis

The thesis of your comparison/contrast paper is very important: it can help you create a focused argument and give your reader a road map so she/he doesn’t get lost in the sea of points you are about to make. As in any paper, you will want to replace vague reports of your general topic (for example, “This paper will compare and contrast two pizza places,” or “Pepper’s and Amante are similar in some ways and different in others,” or “Pepper’s and Amante are similar in many ways, but they have one major difference”) with something more detailed and specific. For example, you might say, “Pepper’s and Amante have similar prices and ingredients, but their atmospheres and willingness to deliver set them apart.”

Be careful, though—although this thesis is fairly specific and does propose a simple argument (that atmosphere and delivery make the two pizza places different), your instructor will often be looking for a bit more analysis. In this case, the obvious question is “So what? Why should anyone care that Pepper’s and Amante are different in this way?” One might also wonder why the writer chose those two particular pizza places to compare—why not Papa John’s, Dominos, or Pizza Hut? Again, thinking about the context the class provides may help you answer such questions and make a stronger argument. Here’s a revision of the thesis mentioned earlier:

You may find our handout Constructing Thesis Statements useful at this stage.

Organizing your paper

There are many different ways to organize a comparison/contrast essay. Here are two:

Subject-by-subject

Begin by saying everything you have to say about the first subject you are discussing, then move on and make all the points you want to make about the second subject (and after that, the third, and so on, if you’re comparing/contrasting more than two things). If the paper is short, you might be able to fit all of your points about each item into a single paragraph, but it’s more likely that you’d have several paragraphs per item. Using our pizza place comparison/contrast as an example, after the introduction, you might have a paragraph about the ingredients available at Pepper’s, a paragraph about its location, and a paragraph about its ambience. Then you’d have three similar paragraphs about Amante, followed by your conclusion.

The danger of this subject-by-subject organization is that your paper will simply be a list of points: a certain number of points (in my example, three) about one subject, then a certain number of points about another. This is usually not what college instructors are looking for in a paper—generally they want you to compare or contrast two or more things very directly, rather than just listing the traits the things have and leaving it up to the reader to reflect on how those traits are similar or different and why those similarities or differences matter. Thus, if you use the subject-by-subject form, you will probably want to have a very strong, analytical thesis and at least one body paragraph that ties all of your different points together.

A subject-by-subject structure can be a logical choice if you are writing what is sometimes called a “lens” comparison, in which you use one subject or item (which isn’t really your main topic) to better understand another item (which is). For example, you might be asked to compare a poem you’ve already covered thoroughly in class with one you are reading on your own. It might make sense to give a brief summary of your main ideas about the first poem (this would be your first subject, the “lens”), and then spend most of your paper discussing how those points are similar to or different from your ideas about the second.

Point-by-point

Rather than addressing things one subject at a time, you may wish to talk about one point of comparison at a time. There are two main ways this might play out, depending on how much you have to say about each of the things you are comparing. If you have just a little, you might, in a single paragraph, discuss how a certain point of comparison/contrast relates to all the items you are discussing. For example, I might describe, in one paragraph, what the prices are like at both Pepper’s and Amante; in the next paragraph, I might compare the ingredients available; in a third, I might contrast the atmospheres of the two restaurants.

If I had a bit more to say about the items I was comparing/contrasting, I might devote a whole paragraph to how each point relates to each item. For example, I might have a whole paragraph about the clientele at Pepper’s, followed by a whole paragraph about the clientele at Amante; then I would move on and do two more paragraphs discussing my next point of comparison/contrast—like the ingredients available at each restaurant.

There are no hard and fast rules about organizing a comparison/contrast paper, of course. Just be sure that your reader can easily tell what’s going on! Be aware, too, of the placement of your different points. If you are writing a comparison/contrast in service of an argument, keep in mind that the last point you make is the one you are leaving your reader with. For example, if I am trying to argue that Amante is better than Pepper’s, I should end with a contrast that leaves Amante sounding good, rather than with a point of comparison that I have to admit makes Pepper’s look better. If you’ve decided that the differences between the items you’re comparing/contrasting are most important, you’ll want to end with the differences—and vice versa, if the similarities seem most important to you.

Our handout on Organization can help you write good topic sentences and transitions and make sure that you have a good overall structure in place for your paper.

Cue words and other tips

To help your reader keep track of where you are in the comparison/contrast, you’ll want to be sure that your transitions and topic sentences are especially strong. Your thesis should already have given the reader an idea of the points you’ll be making and the organization you’ll be using, but you can help her/him out with some extra cues. The following words may be helpful to you in signaling your intentions:

- like, similar to, also, unlike, similarly, in the same way, likewise, again, compared to, in contrast, in like manner, contrasted with, on the contrary, however, although, yet, even though, still, but, nevertheless, conversely, at the same time, regardless, despite, while, on the one hand … on the other hand.

For example, you might have a topic sentence like one of these:

- Compared to Pepper’s, Amante is quiet.

- Like Amante, Pepper’s offers fresh garlic as a topping.

Some additional websites about comparison/contrast papers

https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/how-write-comparative-analysis

http://depts.washington.edu/pswrite/compare.html

- Provided by : The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Located at : https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/comparing-and-contrasting/ . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

Privacy Policy

COMMENTS

B. It shows that he thinks that Conrad is uncomfortable with the idea of African power. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Read the excerpt from "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness." Which statement best explains how the attitudes toward African culture are presented in the two excerpts?, Read ...

Flashcards Comparing the Presentation of Cultures in Literary Texts | Quizlet. Get a hint. Read the excerpt from "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness." Which statement best explains how the attitudes toward African culture are presented in the two excerpts? Click the card to flip. C. Achebe's passage describes hypocritical ...

Quizlet has study tools to help you learn anything. Improve your grades and reach your goals with flashcards, practice tests and expert-written solutions today. Match. Comparing the Presentation of Cultures in Literary Texts. Log in. Sign up. Ready to play?

Compare and Contrast Essay Basics. The Compare and Contrast Essay is a literary analysis essay, but, instead of examining one work, it examines two or more works. These works must be united by a common theme or thesis statement. For example, while a literary analysis essay might explore the significance of ghosts in William Shakespeare's Hamlet ...

We define culture as a collectively formed and shared conceptual understanding of the self, the world, and one's place within the world. Culture is transmitted across generations and is also internalized as a set of perspectives, proclivities, and motivations that underlie human actions (Williams, 1995).Culture impacts our perceptions of ourselves, our world, our place in that world, and ...

Comparing the Presentation of Cultures in Literary Texts Comparing Perspectives: Chinua Achebe Underline the phrase in the excerpt that shows what Achebe thinks Conrad's perspective of Africa is. The difference in the attitude of the novelist to these two women is conveyed in too many direct and subtle ways to need elaboration.

Introduction: your readers with details about the topic or author, and present your . Body paragraph 1: and analyze the biography, providing. relevant details and from the text. Body paragraph 2: Examine and the editorial, providing. relevant and examples from the text.

Cultural studies is often taken to mean a research orientation emphasising contexts and opposing text-centred analysis, or even textual analysis per se. And indeed, early cultural studies emerged as a reaction against immanent and elitist notions of culture and meaning which were prevalent especially in literary studies.

Making a Venn diagram or a chart can help you quickly and efficiently compare and contrast two or more things or ideas. To make a Venn diagram, simply draw some overlapping circles, one circle for each item you're considering. In the central area where they overlap, list the traits the two items have in common.

To clarify, a culture represents the beliefs and practices of a group, while society represents the people who share those beliefs and practices. Neither society nor culture could exist without the other. It is through intercultural communication that you come to create, understand, and transform culture and identity.

Alignment: the way in which elements such as text features, images, and particularly text are placed on a page. Text can be aligned at the left, center, or right. Alignment contributes to organization and how media transitions within a text. Audience: readers or viewers of the composition. Channel: a medium used to communicate a message. Often ...

A thesis statement is the author's educated opinion that can be defended. For a comparative essay, your thesis statement should assert why the similarities and differences between the literary works matter. Step 4: Create a Structure. Before drafting, create an outline. Your introduction should draw the reader in and provide the thesis statement.

A Doll's House. Think about the type of space that you need to do something even just to collect your thoughts. or. consequences of the event. 2. 4. Here are other. structures used in nonfiction texts. Presents an issue or concern, then explains one or several ways to address it.

journey has evolved from a simple literary tool into a cross-cultural touchstone that shapes ... there is an endless bank of mythological and religious texts that are even deeper sources for modern adaptations. When exploring these various mythologies and comparing them to one another, it is easy to see that the collective human experience runs ...

One of the most basic types of contextual analysis is the interpretation of subject matter. Much art is representational (i.e., it creates a likeness of something), and naturally we want to understand what is shown and why. Art historians call the subject matter of images iconography. Iconographic analysis is the interpretation of its meaning.

then it is important that one compare it with the corresponding genre of text from another culture that fulfills the same function there.14 When we come to the matter of the relationship between Ugaritic literature and the OT, the comparison is basically between different genres of literature. As P. C. Craigie says,

These are the CCS Standards addressed in this lesson: RL.5.1: Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. RL.5.4: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative language such as metaphors and similes. RL.5.9: Compare and contrast stories in the same genre (e.g., mysteries and ...

Compare the presentation of in two literary texts. purpose cultures development A. the collection of beliefs, behaviors, arts, and other materials of a group B. the writer's argument or thesis, supported by evidence C. an author's feelings on or opinion of a topic D. a story, usually a short one, that provides interest,

131. $4.00. PDF. Google Apps™. RI 2.9 Compare and Contrast Text on Similar TopicsAvailable with printable PDF version and Google Slides. This product contains 16 short informational reading passages. The texts are in pairs of 2. Each pair has a similar main topic.

This handout will help you first to determine whether a particular assignment is asking for comparison/contrast and then to generate a list of similarities and differences, decide which similarities and differences to focus on, and organize your paper so that it will be clear and effective. It will also explain how you can (and why you should ...