The 5 Elements of Dramatic Structure: Understanding Freytag’s Pyramid

Sean Glatch | November 17, 2023 | 15 Comments

What is Freytag’s Pyramid, and how can it help you write better stories? In simple terms, Freytag’s Pyramid is a five-part map of dramatic structure itself. Understanding the five steps of Freytag’s Pyramid will give you a clearer sense of what makes a strong, compelling story.

Most stories follow a simple pattern called Freytag’s Pyramid.

Storytelling is one of the oldest human traditions, and although the art of creative writing traverses dozens of genres and thousands of languages, the actual storytelling formula hasn’t changed all that much. Whether you’re writing short stories, screenplays, nonfiction, or even some narrative poetry, the majority of stories follow a fairly simple pattern called Freytag’s Pyramid.

Introduction to Freytag’s Pyramid

What is Freytag’s Pyramid? Novelist Gustav Freytag developed this narrative pyramid in the 19th century, as a description of a structure fiction writers had used for millennia. It’s quite famous, so you may have heard it mentioned in an old English class, or maybe more recently in one of our online fiction writing courses.

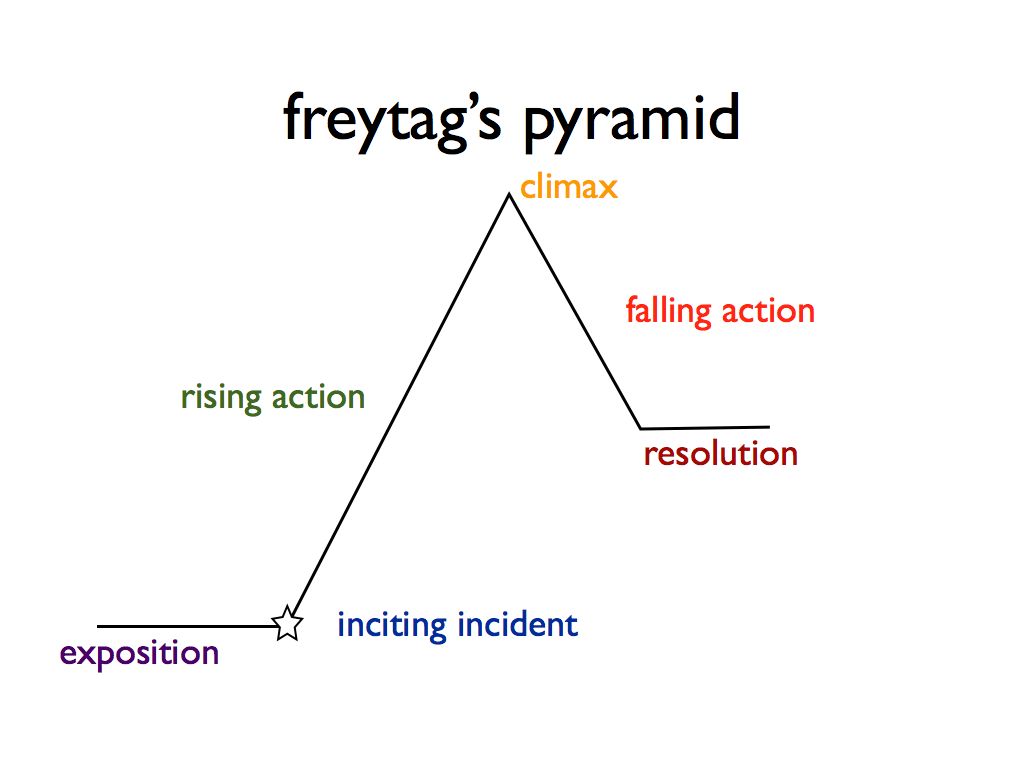

Freytag’s Pyramid describes the five key stages of a story, offering a conceptual framework for writing a story from start to finish. These stages are:

- Rising Action

- Falling Action

Here is the five-part structure of Freytag’s Pyramid in diagram form.

Stages of a Story: Freytag’s Pyramid Diagram

If you’re looking to write your next story or polish one you just wrote, read more on Freytag’s Pyramid and what each element can do for your writing.

1. Freytag’s Pyramid: Exposition

Your story has to start somewhere, and in Freytag’s Pyramid, it starts with the exposition. This part of the story primarily introduces the major fictional elements – the setting, characters, style, etc. In the exposition, the writer’s sole focus is on building the world in which the story’s conflict happens.

The length of your exposition depends on the complexity of the story’s conflict, the extent of the world being written, and the writer’s own personal preference. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is wrought with backstory and exposition, often spanning chapters of pure worldbuilding. By contrast, C. S. Lewis offers very little exposition in the Chronicles of Narnia series, choosing instead to entangle conflict with worldbuilding. Still, whether your exposition is fifty pages or a sentence, use this part of the story to draw readers in. Make your fictional world as real as this one.

Your exposition should end with the “ inciting incident ” – the event that starts the main conflict of the story.

2. Freytag’s Pyramid: Rising Action

The rising action explores the story’s conflict up until its climax. Often, things “get worse” in this part of the story: someone makes a wrong decision, the antagonist hurts the protagonist, new characters further complicate the plot, etc.

For many stories, rising action takes up the most amount of pages. However, while this part of the book explores the story’s conflict and complications, the rising action should investigate much more than just the story’s plot. In rising action, the reader often gains access to key pieces of backstory. As the conflict unfolds, the reader should learn more about the characters’ motives, the world of the story, the themes being explored, and you may want to foreshadow the climax as well.

Finally, when you look back at the story’s rising action, it should be clear how each plot point connects to the story’s climax and aftermath. But first, let’s write the climax.

3. Freytag’s Pyramid: Climax

Of course, every part of your story is important, but if there’s one part where you really want to stick the landing, it’s the climax. Here, the story’s conflict peaks and we learn the fate of the main characters. A lot of writers enter the climax of their story believing that it needs to be short, fast, and action-packed. While some stories might require this style of climax, there’s no strict formula when it comes to climax writing. Think of the climax as the “turning” point in the story – the central conflict is addressed in a way that cannot be undone.

Whether the climax is only one scene or several chapters is up to you, but remember that your climax isn’t just the turning point in the story’s plot structure, but also its themes and ideas. This is your opportunity to comment on whatever concept is driving your story’s narrative, giving the reader an emotional takeaway.

Note: for playwrights, the climax is usually the middle act, though of course not every theatrical production follows the rules.

4. Freytag’s Pyramid: Falling Action

In falling action, the writer explores the aftermath of the climax. Do other conflicts arise as a result? How does the climax comment on the story’s central themes? How do the characters react to the irreversible changes made by the climax?

The story’s falling action is often the trickiest part to write. The writer must start to tie up loose ends from the main conflict, explore broader concepts and themes, and push the story towards some form of a resolution while still keeping the focus on the climax and its aftermath. If the rising action pushes the story away from “normal,” the falling action is a return to a “new normal,” though rising and falling action look dramatically different.

At the same time, the story must still engage the reader. When writing the story’s falling action, be sure to expand on the world of the story, the mysteries that lie within that world, and whatever else makes your story compelling.

5. Freytag’s Pyramid: Resolution/Denouement

How do you end a story? One of the most frustrating parts of writing is figuring out where the narrative ends. Theoretically, the story can continue on forever, especially in the aftermath of a life-altering climax, or even if the story is set in an alternate world.

The resolution of the story involves tying up the loose ends of the climax and falling action. Sometimes, this means following the story’s aftermath to a chilling conclusion—the protagonist dies, the antagonist escapes, a fatal mistake has fatal consequences, etc. Other times, the resolution ends on a lighter note. Maybe the protagonist learns from their mistakes, starts a new life, or else forgives and rectifies whatever incited the story’s conflict. Either way, use the resolution to continue your thoughts on the story’s themes, and give the reader something to think about after the last word is read.

Some writers also use the term “denouement” when discussing the resolution. A denouement [day-new-mawn] refers to the last event that ties up the story’s loose ends, sometimes expressed in the story’s epilogue or closing scene.

Closing Thoughts on Dramatic Structure

Though some literary works break the traditional narrative structure of Freytag’s Pyramid or try to invert it, every story has a relationship to these five dramatic elements. Having a dramatic structure is the first step to a full story outline , which is especially important for longer works of fiction—especially writing the novel . Once you’ve fine-tuned these parts of the story, you’ll have written your next creative work from start to finish!

See Our Upcoming Creative Writing Courses

Sean Glatch

15 comments.

Hello. I am trying to be a playwright. I have written several plays and have a great Mentor, a professional playwright herself. However, she has confused me recently and I wonder if you can settle the issue. When I first started writing she recommended Michael Hauge’s Six Stage Plot Structure. I have been using this to structure my plays. She has recently suggested Freytag’s Pyramid. My confusion is where does the climax come in. Freytag has it in the middle. Hauge clearly has it at Stage V about 90% into the play.

How do I resolve this structure issue?

Hey Ed, great question! It comes down to a difference in philosophies about story structure. Freytag’s structure is heavily influenced by an admiration for Greek plays, which valued symmetry and thought that a climax ought to be in the middle. Some playwrights, like Henrik Ibsen, subscribed to this notion very intensely.

Hauge, as you mentioned, puts the climax way later, which is a more modern idea of the climax – the idea that climax and resolution go hand-in-hand, and also that climax should provide a certain level of entertainment and suspense.

I think your question is best answered by what you’re trying to accomplish. If you’re looking for symmetry, choose Freytag; if you’re looking for suspense or modernity, choose Hauge.

I thought this story structure originally came from Aristotle?

Hi Becky! You’re right in a way. Aristotle originally mapped a story triangle in his Poetics , based on his observations of Greek literature. However, his triangle only included (in translation) the Exposition, Climax, and Resolution. Freytag adapted this triangle and added two more sections–the Rising Action and the Denouement. These structures have existed far before even Aristotle’s time, we just credit Aristotle and Freytag for observing and mapping those structures. Thanks for your comment!

Thanks so much for clarifying so many issues. I am writing a true story of which I am part, but with multiple characters. My struggle has been writing from first person point of view or third person. In the process of searching, I landed on this page and what a blessing. You have explained more and helped me understand writing a story using Freytag’s Pyramid. My online course explained it in fundamentals of fiction and memoir writing using; the set up, inciting incident, first slap, second slap ( I think), climax and then resolution, but herein, I get a better picture I believe. Thanks so much. If you have any suggestions on which point of view to use in a story I am involved in with other characters, please let me know. Thanks again.

Hi Victoria,

I’m so glad this article was helpful! We have another article related to point of view that may interest you, check it out here .

Best of luck writing your story!

[…] Why four? Well, originally it was because I figured that the Falling Action and Resolution from Freytag’s Pyramid could be combined; both are usually relatively short in novels (and just about anything that […]

[…] you can follow. There’s the synopsis outline, the snowflake method, the Hero’s Journey, Freytag model, or the three-act structure, among many others. My personal favorite is the three-act structure […]

[…] plot structure to use in narrative fiction: some people swear by a standard three-act, some find Freytag’s Pyramid useful, you’ve probably heard about “the hero’s journey” a million times. They all tend to […]

[…] if a story has a long resolution in terms of the Freytag plot triangle, it is a sign that the author is (1) signaling a sense of long-term stability, indicating the […]

[…] movies is nothing new, often citing the studios frequent use of the Hero’s Journey and Freytag’s Pyramid theories of narrative structure. Even veteran Hollywood director Martin Scorsese had something to […]

[…] of fiction: plot, character, setting, theme, and structure. “Night Train” fits into Freytag’s plot triangle although many of the segments are very […]

[…] (2020) The 5 Stages of Freytag’s Pyramid: Introduction to Dramatic Structure. Available at: https://writers.com/freytags-pyramid (Accessed: 15th April […]

“When he’s not writing, which is often, he thinks he should be writing.” Haha, that is totally me! I am teaching my students personal narratives and am using Freytag’s Pyramid to help them craft their stories. Additionally, I hope they connect the theory to a “growth mindset” too.

Thank you for giving us a contemporary take on the story shape.

[…] Stories are often lovable because of the troubles and trials you watch and overcome together with the protagonist. Why else would most stories would follow Freytag’s pyramid structure? […]

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Entertainism

The Elements of Drama: Theme, Plot, Characters, Dialog, and More

Drama is a composition of prose or poetry that is transformed into a performance on stage. The story progresses through interactions between its characters and ends with a message for the audience. What are the different elements of drama? How are they related to each other? How do they affect the quality and thereby the popularity of a play? Read on to find out.

The six Aristotelian elements of drama are, plot , character , thought , diction , spectacle , and song . Out of these, the first two are the most important ones according to Aristotle.

Drama can be defined as a dramatic work that actors present on stage. A story is dramatized, which means the characters and events in the story are brought to life through a stage performance by actors who play roles of the characters in the story and act through its events, taking the story forward. In enacting the roles, actors portray the character’s emotions and personalities. The story progresses through verbal and non-verbal interactions between the characters, and the presentation is suitably supplemented by audio and visual effects.

Through the characters involved, the story has a message to give. It forms the central theme of the play around which the plot is built. While some consider music and visuals as separate elements, others prefer to club them under staging which can be regarded as an independent element of drama. Lighting, sound effects, costumes, makeup, gestures or body language given to characters, the stage setup, and the props used can together be considered as symbols that are elements of drama. What dictates most other dramatic elements is the setting; that is the time period and location in which the story takes place. This Buzzle article introduces you to the elements of drama and their importance.

The theme of a play refers to its central idea. It can either be clearly stated through dialog or action, or can be inferred after watching the entire performance. The theme is the philosophy that forms the base of the story or a moral lesson that the characters learn. It is the message that the play gives to the audience. For example, the theme of a play could be of how greed leads to one’s destroyal, or how the wrong use of authority ultimately results in the end of power. The theme of a play could be blind love or the strength of selfless love and sacrifise, or true friendship. For example, the play Romeo and Juliet , is based on a brutal and overpowering romantic love between Romeo and Juliet that forces them to go to extremes, finally leading them to self-destruction.

The order of events occurring in a play make its plot. Essentially, the plot is the story that the play narrates. The entertainment value of a play depends largely on the sequence of events in the story. The connection between the events and the characters in them form an integral part of the plot. What the characters do, how they interact, the course of their lives as narrated by the story, and what happens to them in the end, constitutes the plot. A struggle between two individuals, the relation between them, a struggle with self, a dilemma, or any form of conflict of one character with himself or another character in the play, goes into forming the story’s plot. The story unfolds through a series of incidents that share a cause-and-effect relationship. Generally, a story begins with exposing the past or background of the main and other characters, and the point of conflict, then proceeds to giving the central theme or climax. Then come the consequences of the climax and the play ends with a conclusion.

The characters that form a part of the story are interwoven with the plot of the drama. Each character in a play has a personality of its own and a set of principles and beliefs. Actors in the play have the responsibility of bringing the characters to life. The main character in the play who the audience identifies with, is the protagonist. He/she represents the theme of the play. The character that the protagonist conflicts with, is the antagonist or villain. While some characters play an active role throughout the story, some are only meant to take the story forward and some others appear only in certain parts of the story and may or may not have a significant role in it. Sometimes, these characters are of help in making the audiences focus on the play’s theme or main characters. The way in which the characters are portrayed and developed is known as characterization. Here is a list of characters in Romeo and Juliet .

The story of a play is taken forward by means of dialogs. The story is narrated to the audiences through the interaction between the play’s characters, which is in the form of dialogs. The contents of the dialogs and the quality of their delivery have a major role to play in the impact that the play has on the audiences. It is through the dialogs between characters that the story can be understood. They are important in revealing the personalities of the characters. The words used, the accent, tone, pattern of speech, and even the pauses in speech, say a lot about the character and help reveal not just his personality, but also his social status, past, and family background as given by the play. Monologues and soliloquies that are speeches given to oneself or to other characters help put forward points that would have been difficult to express through dialogs. “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose By any other name would smell as sweet” from Romeo and Juliet in which Juliet tells Romeo of the insignificance of names or “To be, or not to be”, a soliloquy from Hamlet are some of the greatest lines in literature.

The time and place where a story is set is one of its important parts. The era or time in which the incidents in the play take place, influence the characters in their appearance and personalities. The time setting may affect the central theme of the play, the issues raised (if any), the conflict, and the interactions between the characters. The historical and social context of the play is also defined by the time and place where it is set. The time period and the location in which the story is set, affect the play’s staging. Costumes and makeup, the backgrounds and the furniture used, the visuals (colors and kind of lighting), and the sound are among the important elements of a play that dictate how the story is translated into a stage performance. The Merchant of Venice has been set in the 16th century Venice. Romeo and Juliet has been set in the era between 1300 and 1600, perhaps the Renaissance period which is the 14th and 15th centuries.

Performance

It is another important element of drama, as the impact that a story has on the audiences is largely affected by the performances of the actors. When a written play is transformed into a stage performance, the actors cast for different roles, the way they portray the characters assigned to them, and the way their performances are directed are some important factors that determine the play’s impact. Whether an actor’s appearance (includes what he wears and how he carries himself on stage) suits the role he is playing, and how well he portrays the character’s personality are determinants of how well the play would be taken by the audiences. Different actors may play the same roles in different renditions of a play. A particular actor/actress in a certain role may be more or less accepted and appreciated than another actor in the same role. As different actors are cast for different roles, their roles are more or less appreciated depending on their performances. The stage performances of a play’s characters, especially those in lead roles, directly affect the success and popularity of a play.

Although considered as a part of the staging, factors such as music and visuals can be discussed separately as the elements of drama.

This element includes the use of sounds and rhythm in dialogs as well as music compositions that are used in the plays. The background score, the songs, and the sound effects used should complement the situation and the characters in it. The right kind of sound effects or music, if placed at the right points in the story, act as a great supplement to the high and low points in the play. The music and the lyrics should go well with the play’s theme. If the scenes are accompanied by pieces of music, they become more effective on the audiences.

Visual Element

While the dialog and music are the audible aspects of drama, the visual element deals with the scenes, costumes, and special effects used in it. The visual element of drama, also known as the spectacle, renders a visual appeal to the stage setup. The costumes and makeup must suit the characters. Besides, it is important for the scenes to be dramatic enough to hold the audiences to their seats. The special effects used in a play should accentuate the portion or character of the story that is being highlighted.

Apart from these elements, the structure of the story, a clever use of symbolism and contrast, and the overall stagecraft are some of the other important elements of drama.

The structure of the story comprises the way in which it is dramatized. How well the actors play their roles and the story’s framework constitute the structure of drama. Direction is an essential constituent of a play. A well-directed story is more effective. Stagecraft defines how the play is presented to the audiences. The use and organization of stage properties and the overall setting of a play are a part of stagecraft, which is a key element of drama.

Symbols are often used to give hints of the future events in the story. They complement the other elements of a scene and make it more effective. The use of contrasts adds to the dramatic element of a play. It could be in the form of contrasting colors, contrasting backdrops, an interval of silence followed by that of activity and noise, or a change in the pace of the story.

The dramatization of a story cannot be called successful unless the audiences receive it well. It may improve through constructive criticism or due to improvisations introduced by the actors. And a generous appreciation from the audiences encourages everyone involved in the making of a play, to continue doing good work.

Like it? Share it!

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Further insights.

Privacy Overview

Elements of Creative Writing

J.D. Schraffenberger, University of Northern Iowa

Rachel Morgan, University of Northern Iowa

Grant Tracey, University of Northern Iowa

Copyright Year: 2023

ISBN 13: 9780915996179

Publisher: University of Northern Iowa

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Robert Moreira, Lecturer III, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 3/21/24

Unlike Starkey's CREATIVE WRITING: FOUR GENRES IN BRIEF, this textbook does not include a section on drama. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

Unlike Starkey's CREATIVE WRITING: FOUR GENRES IN BRIEF, this textbook does not include a section on drama.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

As far as I can tell, content is accurate, error free and unbiased.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The book is relevant and up-to-date.

Clarity rating: 5

The text is clear and easy to understand.

Consistency rating: 5

I would agree that the text is consistent in terms of terminology and framework.

Modularity rating: 5

Text is modular, yes, but I would like to see the addition of a section on dramatic writing.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Topics are presented in logical, clear fashion.

Interface rating: 5

Navigation is good.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

No grammatical issues that I could see.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

I'd like to see more diverse creative writing examples.

As I stated above, textbook is good except that it does not include a section on dramatic writing.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One: One Great Way to Write a Short Story

- Chapter Two: Plotting

- Chapter Three: Counterpointed Plotting

- Chapter Four: Show and Tell

- Chapter Five: Characterization and Method Writing

- Chapter Six: Character and Dialouge

- Chapter Seven: Setting, Stillness, and Voice

- Chapter Eight: Point of View

- Chapter Nine: Learning the Unwritten Rules

- Chapter One: A Poetry State of Mind

- Chapter Two: The Architecture of a Poem

- Chapter Three: Sound

- Chapter Four: Inspiration and Risk

- Chapter Five: Endings and Beginnings

- Chapter Six: Figurative Language

- Chapter Seven: Forms, Forms, Forms

- Chapter Eight: Go to the Image

- Chapter Nine: The Difficult Simplicity of Short Poems and Killing Darlings

Creative Nonfiction

- Chapter One: Creative Nonfiction and the Essay

- Chapter Two: Truth and Memory, Truth in Memory

- Chapter Three: Research and History

- Chapter Four: Writing Environments

- Chapter Five: Notes on Style

- Chapter Seven: Imagery and the Senses

- Chapter Eight: Writing the Body

- Chapter Nine: Forms

Back Matter

- Contributors

- North American Review Staff

Ancillary Material

- University of Northern Iowa

About the Book

This free and open access textbook introduces new writers to some basic elements of the craft of creative writing in the genres of fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. The authors—Rachel Morgan, Jeremy Schraffenberger, and Grant Tracey—are editors of the North American Review, the oldest and one of the most well-regarded literary magazines in the United States. They’ve selected nearly all of the readings and examples (more than 60) from writing that has appeared in NAR pages over the years. Because they had a hand in publishing these pieces originally, their perspective as editors permeates this book. As such, they hope that even seasoned writers might gain insight into the aesthetics of the magazine as they analyze and discuss some reasons this work is so remarkable—and therefore teachable. This project was supported by NAR staff and funded via the UNI Textbook Equity Mini-Grant Program.

About the Contributors

J.D. Schraffenberger is a professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. He is the author of two books of poems, Saint Joe's Passion and The Waxen Poor , and co-author with Martín Espada and Lauren Schmidt of The Necessary Poetics of Atheism . His other work has appeared in Best of Brevity , Best Creative Nonfiction , Notre Dame Review , Poetry East , Prairie Schooner , and elsewhere.

Rachel Morgan is an instructor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. She is the author of the chapbook Honey & Blood , Blood & Honey . Her work is included in the anthology Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in American and has appeared in the Journal of American Medical Association , Boulevard , Prairie Schooner , and elsewhere.

Grant Tracey author of three novels in the Hayden Fuller Mysteries ; the chapbook Winsome featuring cab driver Eddie Sands; and the story collection Final Stanzas , is fiction editor of the North American Review and an English professor at the University of Northern Iowa, where he teaches film, modern drama, and creative writing. Nominated four times for a Pushcart Prize, he has published nearly fifty short stories and three previous collections. He has acted in over forty community theater productions and has published critical work on Samuel Fuller and James Cagney. He lives in Cedar Falls, Iowa.

Contribute to this Page

ENG 125 & 126 - Creative Writing: Drama

- Short Fiction

- Long Fiction

- Non-fiction

- Research Process

Drama Defined

Definition: A prose or verse composition, especially one telling a serious story, that is intended for representation by actors impersonating the characters and performing the dialogue and action.

Elements:

- Structure -- This deals with how to setup the beginning, middle and end of a play and is even more crucial in drama than any other genre of writing.

- Characters -- People will act out the story on stage. Characters should be well-developed and not appear as stereotypes.

- Dialogue -- This is crucial in plays because everything happens through the spoken word.

- Theme -- Plays often deal with universal themes which encourage discussion of ideas.

- Production -- Costumes, props and lighting are some of the necessary items for putting on a play.

Find Plays & Criticism

Video Searching

Library collections (dvd & videotape):.

Search our Card Catalog to find videos housed in the Library-IC collection.

Audiovisual Search:

Streaming Media

Featured Drama

- << Previous: Poetry

- Next: Research Process >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 2:50 PM

- URL: https://libguides.rccc.edu/creative

Jump to navigation

- Fellows and Core Writers

- Affiliated Writers

- Member Directory

- How To Apply

- Our 2023-24 Season

- Ruth Easton New Play Series

- PlayLabs Festival

- Artists in Conversation

- Membership Podcast: Theater Begins Here

- Script Club

- Member Open Play

- University Courses

- Playwriting Toolkit

- Opportunities

- Latest News

- Enewsletter Sign-up

- A Campaign for All Narratives

- Our Supporters

- The Dominic Orlando Fund

- Staff & Board

- Mission, Vision & Values

- LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

- Accessibility

- Jobs & Auditions

- Apprenticeships

- Facility Rental

- MEMBERSHIP PARTICIPATION AGREEMENTS

- Core Writers

- Jerome Fellows

- Many Voices Fellows

- McKnight Fellows in Playwriting

- McKnight National Residency & Commission Recipient

- McKnight Theater Artist Fellows

- Member Playwrights

- Core Apprentices

- Core Writer Program

- Jerome Fellowships

- Many Voices Program

- McKnight Fellowships in Playwriting

- McKnight National Residency & Commission

- McKnight Theater Artist Fellowships

- New Plays on Campus

- Partnerships

- Venturous Playwright Fellowship

- 2022-23 Season

- eNewsletter Sign-up

- Mission & History

- Internships

Become a member

Exclusive access to our playwriting opportunities database, advice from experts, and chances to connect with other writers.

learn more sign up today

2301 East Franklin Avenue Minneapolis, MN 55406-1099 (612) 332-7481

Search form

Log in to the playwrights' center, decoding the 6 aristotelean elements of drama.

Most of us encounter the 6 Aristotelean elements of Drama in an English course in high school in concert with a handful of creative writing standards we are taught like Gustav Freytag’s Pyramid of Dramatic Structure , or Northrop Frye’s U-shaped patterns of dramatic structure , etc.

These were essentially the tools utilized to assess our ability to comprehend the stories we read in high school, and ultimately to measure the efficacy of our ability to imitate these structures through creative writing exercises like writing prompts and short stories.

But like many lessons in secondary education, these tools are absorbed, assessed, and rarely revisited explicitly unless the student pursues higher education in a field that demands continued exploration of the subject. Since the recent academicization of playwriting, more and more dramatic writing scholars are met with Poetics by Aristotle, and certain aspects of its content are reviewed, referenced, and reinforced to both comprehend and measure the efficacy of our plays. We are met with questions like, “Could you identify the plot?” and “Who is the main character?” Some of these questions cause anxiety and lead to creative roadblocks because the process of creative writing can become intimate and such interrogation quite often appears intrusive. While it is a skill we must develop in our field, not everyone is comfortable discussing their intimate life in public. In this essay, I intend to provide a brief elemental breakdown of the 6 Aristotelean elements of Drama to hopefully eliminate some of the anxiety around its use in academia and other writing workshops we frequent in our respective playwriting careers.

The 6 Aristotelean elements are plot, character, thought, diction, spectacle, and song. Below are the definitions I utilize to better understand the way in which each element helps me build a play. It is important to note that these elements are already at work in our playwriting, but the more we can identify them, the better we can employ each element, or not.

1) PLOT = What , the main action , which can be described through the character’s objectives. For example, in Lorraine Hansberry’s definitive play, A Raisin in the Sun , the patriarch is dead and his financially fraught family awaits his life insurance check. The eldest son Walter Lee wants to utilize the check to open a liquor store, while his sister Beneatha wants to use the money to pay her college tuition, and their mother Lena Younger, the lawful beneficiary of the coveted insurance check, and therefore has the authority to make the ultimate decision about how to invest it and why. The major dramatic question that is explored through the action in the play is: What to do with dad’s life insurance check?

2) CHARACTER (COMMUNITY) = Who , the protagonist and their relationship to the other characters and to the world they inhabit. I tend to substitute the Aristotelean term character for community to describe more ensemble driven plays. In a rare interview, Hansberry discusses how a traditional protagonist never fully emerges in A Raisin in the Sun ; ( https://youtu.be/ZkFR_6DGJ3o ). While Walter Lee talks the most, his sister Beneatha is certainly an ambitious runner up, and similar arguments are made for their mother Lena. I suppose it depends on the production.

At any rate, this is an example of an ensemble driven play where the stakes are high for all, and the playwright has created space for each character we meet to articulate and defend their ambitions respectively. Such plays are often created by historically marginalized playwrights (e.g. August Wilson, Pearl Cleage) who are more interested in equity than centering one voice. There is something inherently political about it, but I digress.

3) THOUGHT = Why , the psychology behind the character’s action. Why does a character want what he wants? In A Raisin in The Sun , both Walter Lee and Beneatha want to secure upward mobility. Which (sidebar) is a masterclass in creating conflict, because both characters want to utilize a shared inheritance to mobilize their respective career objectives, in order to meet the same psychological need, financial security.

4) DICTION = How , the dialogue , which in addition to action, is a tactic characters utilize to achieve their, often opposing, objectives. Think of the debates between Walter Lee and Beneatha. The dialogue is used to delineate their psychology and defend their plans for the money.

5) SPECTACLE = Where , that which we can see on stage, also known as setting. A Raisin in the Sun is set in a crowded 1950’s tenement apartment on the South Side of Chicago. All of which informs the narrative that will unfold.

6) SONG = Rhythm of speech or the use of literal music. Both of which are utilized to drive a narrative forward, or delineate character and emotion. Or all of that! The rhythm of speech quite often reveals, urgency, mood, culture, etc. Hansberry’s realism is partly driven by declarative speeches (e.g. Walter Lee), and lectures and lessons from Beneatha and Lena Younger.

Thus the 6 elements we utilize to build drama are what , who , why , how , where , and rhythm of speech. This is in part a journalistic approach to playwriting in which we can begin to ask ourselves questions about a play before entering a workshop.

Lastly, there are of course differing genres which inform a plot like tragedy, comedy, procedurals, etc. But I maintain that a plot also inherently unfolds in the relationships we establish in our plays. For example, in A Raisin in The Sun we meet a set of ambitious siblings who need all or part of their collective inheritance to achieve their respective goals. A plot is already made evident in their relationship.

In conclusion, it is important for playwrights to remember that the poets taught Aristotle. He did not teach the poets. He analyzed their work and wrote critically about it. Essentially, he is an ancient critic we are taught to revere. Again, it is important to note that these elements are already at work in our playwriting, but the more we can identify them the better we can describe a play to collaborators who utilize the 6 Aristotelean elements of drama as a frame of reference to interpret modern drama. []

About the author

Tylie Shider is a Jerome Fellow at the Playwrights’ Center and a 2019 - 2021 I Am Soul Playwright in Residence at the National Black Theatre . He holds a BA in Journalism from Delaware State University and an MFA in dramatic writing from NYU.

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, overview of playwriting.

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by Mark Leib

Successful playwriting depends not only on dialogue, but on intelligent plotting, credible characterization, and the ability to develop a theme through 70 to 90 pages of encounters and exchanges (in a full-length play). The pleasures of writing drama can be significant. Writers for the stage can have the satisfying experience of watching an audience hang on every word, laugh at every witticism, and show their appreciation at the play’s end with grateful applause.

Writing for the theater also allows the playwright the advantage of having actors, designers, and a director with whom to collaborate; it’s the rare playwright who hasn’t learned more about their play during rehearsals. Of course, there are difficulties too: at first, the necessity of writing only what can be seen or heard within the walls of a small theater may seem to limit the playwright in comparison with, say, a novelist or screenwriter. But with practice, it turns out that there are solutions to most of these problems and that the ingenuity with which the writer finds these answers can be part of the magic of the stage experience. In fact, “magic” is the right word to describe a successful play: somehow it rises above its flesh-and-blood interpreters and becomes urgently important, funny, inspiring, or devastating. The writer who chooses to work in dramatic or comedic plays can, at best, deliver an experience that will never be forgotten.

Intelligent plotting is essential. Most plays are constructed around the idea of someone who wants something, who faces an obstacle (external or internal) and then struggles with this obstacle until a result is reached. For example, Hamlet wants to kill his uncle Claudius but faces obstacles within himself ( Hamlet , Prince of Darkness ); Blanche DuBois wants to settle down in a conventional marriage in New Orleans but is opposed in this by Stanley Kowalski ( A Streetcar Named Desire ). The playwright must provide desires for their characters and then determine which ones will be fulfilled and which stymied. If the obstacles are too small, the play will lack suspense; if they’re unreasonably great, the play will lack credibility. In a play with more than a few characters, the playwright must manipulate the action so that all the various desires and struggles on the stage can be interwoven. It’s no coincidence that one of the definitions of drama is “conflict.” The playwright must know how to write thinkable conflicts and grab the spectator’s attentions therewith.

Characterization

Characterization is another skill that the writer for the stage must come to master. In realistic drama—still the most popular sort—characters must be “round” and not “flat,” meaning that they must have multiple dimensions, a thinkable combination of virtues and vices, as well as the needs, hopes, inhibitions, and fears of real human beings. Every good playwright is a good psychologist, understanding that, for example, despite all his anger, Biff Loman still loves Willy Loman ( Death of a Salesman ); Amanda Wingfield is not merely a harridan ( The Glass Menagerie ); and Iago’s varied explanations for his hatred of Othello ( Othello , the Moor of Venice ) are the products of a man who fundamentally doesn’t know himself. With less than a hundred pages to work within, the dramatist must learn to sketch characters in such a way that a whole personality can appear once a performer takes the role. This is a talent best developed when working with the actors and the director: there’s no substitute for the writer of seeing their characters actually on stage. Still, much can be learned from the comments of intelligent readers or even from a cold reading with non-professionals taking the play’s parts.

And then there’s dialogue. Here the playwright must strive to find a credible form of discourse that avoids cliché and artificiality and that varies just as characters do: a professor of philosophy shouldn’t sound like a dog trainer, and a harried urban shop girl shouldn’t sound like a wealthy heiress. The secret of good dialogue is selectivity—finding the conversation that most reveals the lives of the speakers, finding the expression that means more than itself, finding the word that the audience can instantly absorb and interpret. The playwright needs to be aware that “realistic” dialogue isn’t always the most suitable choice–that that the absurdities of Ionesco , the elegance of Shaw , the repeated expletives of Mamet are sometimes more appropriate than the more “authentic” sounds of the real world outside the theater. Further, “on-the-nose” dialogue, with which characters say precisely what they mean, isn’t nearly as interesting as “off-the-nose” dialogue, that which proceeds through indirection and ambiguity. Some playwrights, like Chekhov and Pinter , employ what might be called “pause-and-effect.” Others, like Beckett , use a highly charged poetic diction that packs far more energy than a more conventional vocabulary. Every play, the playwright will find, makes its own special demands where dialogue is concerned, and the writer must learn to readjust with each new work.

Finally, there’s theme. It’s not enough to present characters speaking interestingly with each other while engaged in some action; the playwright must have something to say. A typical play might demand two precious hours from a busy, burdened spectator. In this regard, the playwright is no different from the novelist or poet: they must have a purpose that the literary work embodies, a theme or conviction that the drama communicates. Sometimes the idea might be socio-political, as in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House ; sometimes it’s psychological, as in that same playwright’s Hedda Gabler , or even metaphysical, as in his late play The Master Builder . The primary commandment for playwrights is “Thou shalt not waste the audience’s time.” Theatergoers, like readers of short stories or novels, want to be rewarded for investing attention (and often money) in a play: if they’re lucky, they’ll find that the dramatist has illuminated some area of human life, perhaps made existence a little more comprehensible. A playwright who’s able to shed a little light on a spectator’s life has lived up to a high calling. Such a writer need not worry that their efforts are misspent.

“The Play’s the Thing”

The art of the dramatist has been practiced in the Western world for 2,500 years and has given us the great works of Sophocles , Shakespeare , Strindberg , and Shaw . But this history is not enough: every age has its own truths and needs the artists who can express them in a contemporary way, employing recognizable characters. If they will learn to develop plots that express a well-considered theme, characters that win the spectators’ credence, and dialogue that leads an audience to think and feel deeply, the result can be riveting. Four hundred years after the Bard first said it, the play’s still the thing. The scribe who chooses to write for the stage is taking on a venerable—and potentially powerful—occupation.

Brevity – Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence – How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow – How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity – Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style – The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

- TRAGEDY : The imitation of an action , not the telling of an action; that is, it is a dramatic recreation (mimesis) rather than narration or simply telling. It demonstrates what has happened and what may happen under the laws of probability, of cause-effect; thus, tragedy is different from and superior to history. The “fear” aroused and purged in the catharsis relates to these laws.

- 6 BASIC ELEMENTS :

- arising from the actions of Tragic Hero

- (laws of probability & necessity)

- with Recognition ( anagnorisis )

- with Reversal of Fortune ( peripeteia )

- with suffering

- --> arouses pity & fear in audience ( catharsis )

- Character = #2

- The best plots are those whose resolutions arise from the construction of the events rather than from characterization—the laws of probability and necessity, cause and effect.

- a beginning, middle, and end: ( Freytag's Pyramid )

- EXPOSITION --> COMPLICATION --> CLIMAX -->

- The plot must also be self-contained , with a unity of action, its events operating under the rules of necessity. Thus, Aristotle frowned upon the reliance of DEUS EX MACHINA (see below).

- Aristotle also mentions that tragic plots should be “of a certain magnitude”; that is, they should possess universality as well as complexity.

- Complex plots should also have PERIPETEIA (see below) and ANAGNORISIS (see below), the former leading to the latter in a matter of cause and effect.

ARISTOTELIAN TRAGEDY

- The tragic character, secondary to plot, should possess a moral quality, for who should pity the fall of an evil man?

- The tragic heroes should also be realistic and true to their type (gender), to themselves (consistency of character), and to the laws of necessity and probability.

- While the characters should be realistic, Aristotle suggests that they should also be “more beautiful,” idealized, elevated, or ennobled.

- These elements are below Plot and Character in order of importance.

- If the construction, or Plot, of the play is sound, then the superior poet will not need to rely upon these or, at the very least, they will take care of themselves.

- the media of imitation

- words appropriate to character, plot, tragedy

- metaphor = mark of genius

- Chorus' songs should be part of the plot, not mere interludes

- tragedy does not need to be performed to be effective

- tragedy can be read for the same effect

- (sensory effects)

- "stagecraft"

- A sudden reversal of fortune, or circumstances, leading to the protagonist’s downfall.

- The peripeteia should be closely related to the anagnorisis ( recognition ).

- It means “ recognition ” or “ discovery ,” and Aristotle uses these to denote the turning point in a drama at which the protagonist recognizes the true state of affairs, having previously been in error or ignorance.

- We might say this is the moment in which the “tragic hero” recognizes his “tragic error” or “tragic mistake.”

- Perhaps, too, we can call this a “moment of clarity.” For example, Oedipus recognizes that he killed his father, married his mother, and brought a plague upon his people.

- A weakness in a tragedy or a writer who relies upon this artifice to resolve the Plot, rather than the action resolving itself according to the laws of probability and necessity.

- Literally, it means “ god in/from the machine, ” and it involved the lowering of a god onto the stage via machinery in order to resolve the entanglements of the situation/plot.

- The “ purging ” of pity and fear in the tragic audience.

- PITY = eleos: compassion for Pathos bearer

- TERROR - FEAR = identification with Pathos bearer

- PATHOS = Passion, key/religious suffering

- that is, it is a dramatic recreation (mimesis)

- rather than narration or simply telling.

- thus, tragedy is different from and superior to history.

- The “ fear ” aroused and purged in the catharsis relates to these laws.

- The most fundamental and important aspect of tragedy, referring more to the structure or organization of the play than merely “what happens.”

- ( laws of probability & necessity )

- character = #2

- the laws of probability and necessity ,

- cause and effect.

- a beginning, middle, and end :

- ( Freytag's Pyramid )

- DENOUEMENT --> RESOLUTION

- Thus, Aristotle frowned upon the reliance of DEUS EX MACHINA ( see below ).

- that is, they should possess universality as well as complexity .

- Complex plots should also have PERIPETEIA ( see below ) and ANAGNORISIS ( see below ), the former leading to the latter in a matter of cause and effect.

- The tragic character, secondary to plot , should possess a moral quality, for who should pity the fall of an evil man?

- The tragic heroes should also be realistic and true to their type (gender), to themselves (consistency of character), and to the laws of necessity and probability .

- While the characters should be realistic, Aristotle suggests that they should also be “more beautiful,” idealized, elevated, or ennobled .

- costuming, scenery, gestures, voice

- A sudden reversal of fortun e, or circumstances, leading to the protagonist’s downfall.

- The peripeteia should be closely related to the anagnorisis (recognition).

- Meaning “ recognition ” or “ discovery ,” Aristotle uses these to denote the turning point in a drama at which the protagonist recognizes the true state of affairs, having previously been in error or ignorance.

- Perhaps, too, we can call this a “ moment of clarity .”

- For example , Oedipus recognizes that he killed his father, married his mother, and brought a plague upon his people .

- Literally, it means “ god in/from the machine ,” and it involved the lowering of a god onto the stage via machinery in order to resolve the entanglements of the situation/plot.

- eleos : compassion for Pathos bearer

- identification with Pathos bearer

- Passion, key/religious suffering

CHARACTERIZATION:

- Melodrama, Tragi-comedy

- Theater of the Absurd

- stage directions

- dramatis personae

- in the round (arena stage)

- black box (flexible stage)

- link (w/pix), link

- scenery & props

- lights & sound

- inflection, projection, diction,...

- gesture, facial expressions, body posture/alignment, blocking, movement

- Post-Modern

Elements of Drama – Lesson Plan

Students explore plot development and rising action, turning point, and falling action by viewing a short play written and performed by high school students.

- Length: Two class periods: one for introduction, one for application.

Concepts/Objectives:

- Students will explore, analyze, and use the literary elements of drama.

Resource Used: Basics Found On: Performance Excerpts

Vocabulary, Resources, and Handouts

Vocabulary discovery, empathy, falling action, language, literary elements, motivation, plot development, rising action, suspense, theme, turning point Materials TV/VCR or DVD player Optional: graphic organizers Handouts:

- Multiple-Choice Questions

↑ Top

Instructional Strategies and Activities

Before viewing the video excerpt Introduce the topic by reminding students that dramatic situations are all around us. Tell them to picture an argument between a basketball coach and a referee in a championship game. Imagine a situation in which two students are competing for the lead in the class play. Ask what they would do if a friend were falsely accused of cheating. Any one of these situations could be the basis for a short play, but first we have to understand what must happen to transfer personal experiences or feelings to the stage. No matter what the subject matter, plays are constructed around three important literary elements: rising action, turning point, and falling action. Write on the board or an overhead:

- Rising Action: Main problems are introduced (characters, issues, the exposition).

- Turning Point: The problem or conflict occurs.

- Falling Action: Repercussions occur (a result of the conflict or a resolution to it).

Give each student a graphic organizer divided into three columns, or ask them to divide a piece of paper into three columns. Label the columns Rising Action, Turning Point, and Falling Action. Students can note the information being written on the board and discussed. They can also note the elements on the sheet as they watch the video. For LEP students, you can add a visual clue before each label to facilitate understanding. And if you have students for whom note taking is difficult, consider providing a completed page for them to check as they hear or see the information noted. Viewing activity Watch “Basics.” Ask students to consider and note when and where each of the three elements occurs. Student responses may vary, but here are some possibilities: Rising Action: Jade and Taylor both ask, “Do you ever get really confused?” They explain their feelings and the situation: Both have dated others, but “nothing deep.” They’re both unsure of some things, but sure of others. Both Jade and Taylor believe the other has purity of heart. Both are alone and need someone. Both are scared by how they feel. These thoughts set up the main problem: They think they may be falling in love, but are not sure how to deal with it. Should they tell the other person? The action peaks as both Taylor and Jade say, “I’m going to call … definitely.” Turning point: Jade and Taylor simultaneously phone each other and get busy signals. Falling action: Each says, “Maybe we should just be friends.” The play ends as it began, with both asking, “Do you ever get confused?” Wrap-up Remind students that this short but effective play was developed around a simple framework of rising action, turning point, and falling action. Elaborate dramas by Shakespeare or Broadway plays, as well as short stories and novels, often use the same key elements to capture and maintain the audience’s attention. Other possibilities Depending upon the needs of your classroom, consider these options for extending or applying the lesson: Further discussion: Divide the students who have viewed “Basics” into groups. Let them discuss the following questions and summarize their findings to share with the class:

- What specific techniques keep us in suspense and make us want to keep watching “Basics”?

- Empathy allows us to identify with the characters. It happens when the playwright and actors create characters that mirror our own concerns. What moment could you identify with as most empathetic?

- How does the language used by Taylor and Jade help us identify with their feelings?

- What motivates or propels the characters to action? Do you think characters of another generation or even another culture could be motivated by the same needs?

- Do the characters make any discoveries about each other or themselves?

- It seems as if the characters begin with confusion and end with confusion. If so, what was the point, the theme, or the dominant idea of this dramatic work?

- Was this a successful work? Why or why not?

- What suggestions would you make to improve this short drama based on the elements?

A group project: In a second class period, divide the class into three groups to draft 3- to 5-minute dramas modeled after “Basics.” Here’s a process they might use:

- Each group brainstorms ideas, personal experiences, or feelings that might have dramatic potential in a short two-character drama.

- Each group develops the rising action for a short two-character drama.

- Students exchange papers with another group who will construct a turning point.

- Students exchange papers again with a third group to create the falling action and possibly a resolution for the drama.

- Papers are returned to the original groups. Each group selects two people to perform the short drama that has been written in this three-step process.

- Students note and discuss the rising action, turning point, and falling action of each play.

Writing To Communicate

- The Performance Assessment can also be a portfolio writing activity.

- Write a review of “Basics,” discussing the elements of drama.

Open Response Assessment

Prompt: “Basics” lasts just a few minutes, yet it incorporates central dramatic elements of a full-length play: rising action, turning point, and falling action. Directions:

- Identify and describe how each of these elements occurs in “Basics.”

- Using appropriate vocabulary, explain why you think “Basics” is or is not an effective drama.

Open Response Scoring Guide

Performance Assessment

Performance Event: Personal experiences and everyday feelings can be the subject matter for short dramas. Directions: Write a 3- to 5-minute drama modeled after “Basics.” Include rising action, turning point, falling action, and at least one more of the elements of drama (suspense, theme, language, empathy, motivation, discovery). Rely on your personal experiences to create dialogue and to shape your point of view. If you need help with an idea, here are three suggestions:

- Two athletes discuss the game they just played.

- A boy and a girl debate who should pay the check for lunch.

- Two strangers in a cab argue a political point.

Performance Scoring Guide

Support - Connections - Resources - Author

- Robbins, Bruce. “Creative Dramatics in the Language Arts Classroom.” ERIC Digest No. 7, www.vtaide.com/png/ERIC/Creative-Dramatics.htm.

- Schanker, Harry H. and Ommanney, Katharine. The Stage and the School. 8th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989.

- Sporre, Dennis. Reality Through the Arts. 3rd edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1997.

- “Theatrical Production.” Encyclopedia Brittanica Online, www.britannica.com.

Author: Elizabeth Jewell, KET

See more resources for:

See more resources about:.

What this handout is about

This handout identifies common questions about drama, describes the elements of drama that are most often discussed in theater classes, provides a few strategies for planning and writing an effective drama paper, and identifies various resources for research in theater history and dramatic criticism. We’ll give special attention to writing about productions and performances of plays.

What is drama? And how do you write about it?

When we describe a situation or a person’s behavior as “dramatic,” we usually mean that it is intense, exciting (or excited), striking, or vivid. The works of drama that we study in a classroom share those elements. For example, if you are watching a play in a theatre, feelings of tension and anticipation often arise because you are wondering what will happen between the characters on stage. Will they shoot each other? Will they finally confess their undying love for one another? When you are reading a play, you may have similar questions. Will Oedipus figure out that he was the one who caused the plague by killing his father and sleeping with his mother? Will Hamlet successfully avenge his father’s murder?

For instructors in academic departments—whether their classes are about theatrical literature, theater history, performance studies, acting, or the technical aspects of a production—writing about drama often means explaining what makes the plays we watch or read so exciting. Of course, one particular production of a play may not be as exciting as it’s supposed to be. In fact, it may not be exciting at all. Writing about drama can also involve figuring out why and how a production went wrong.

What’s the difference between plays, productions, and performances?

Talking about plays, productions, and performances can be difficult, especially since there’s so much overlap in the uses of these terms. Although there are some exceptions, usually plays are what’s on the written page. A production of a play is a series of performances, each of which may have its own idiosyncratic features. For example, one production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night might set the play in 1940’s Manhattan, and another might set the play on an Alpaca farm in New Zealand. Furthermore, in a particular performance (say, Tuesday night) of that production, the actor playing Malvolio might get fed up with playing the role as an Alpaca herder, shout about the indignity of the whole thing, curse Shakespeare for ever writing the play, and stomp off the stage. See how that works?

Be aware that the above terms are sometimes used interchangeably—but the overlapping elements of each are often the most exciting things to talk about. For example, a series of particularly bad performances might distract from excellent production values: If the actor playing Falstaff repeatedly trips over a lance and falls off the stage, the audience may not notice the spectacular set design behind him. In the same way, a particularly dynamic and inventive script (play) may so bedazzle an audience that they never notice the inept lighting scheme.

A few analyzable elements of plays

Plays have many different elements or aspects, which means that you should have lots of different options for focusing your analysis. Playwrights—writers of plays—are called “wrights” because this word means “builder.” Just as shipwrights build ships, playwrights build plays. A playwright’s raw materials are words, but to create a successful play, they must also think about the performance—about what will be happening on stage with sets, sounds, actors, etc. To put it another way: the words of a play have their meanings within a larger context—the context of the production. When you watch or read a play, think about how all of the parts work (or could work) together.

For the play itself, some important contexts to consider are:

- The time period in which the play was written

- The playwright’s biography and their other writing

- Contemporaneous works of theater (plays written or produced by other artists at roughly the same time)

- The language of the play

Depending on your assignment, you may want to focus on one of these elements exclusively or compare and contrast two or more of them. Keep in mind that any one of these elements may be more than enough for a dissertation, let alone a short reaction paper. Also remember that in most cases, your assignment will ask you to provide some kind of analysis, not simply a plot summary—so don’t think that you can write a paper about A Doll’s House that simply describes the events leading up to Nora’s fateful decision.

Since a number of academic assignments ask you to pay attention to the language of the play and since it might be the most complicated thing to work with, it’s worth looking at a few of the ways you might be asked to deal with it in more detail.

There are countless ways that you can talk about how language works in a play, a production, or a particular performance. Given a choice, you should probably focus on words, phrases, lines, or scenes that really struck you, things that you still remember weeks after reading the play or seeing the performance. You’ll have a much easier time writing about a bit of language that you feel strongly about (love it or hate it).

That said, here are two common ways to talk about how language works in a play:

How characters are constructed by their language

If you have a strong impression of a character, especially if you haven’t seen that character depicted on stage, you probably remember one line or bit of dialogue that really captures who that character is. Playwrights often distinguish their characters with idiosyncratic or at least individualized manners of speaking. Take this example from Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest :

ALGERNON: Did you hear what I was playing, Lane? LANE: I didn’t think it polite to listen, sir. ALGERNON: I’m sorry for that, for your sake. I don’t play accurately—anyone can play accurately—but I play with wonderful expression. As far as the piano is concerned, sentiment is my forte. I keep science for Life. LANE: Yes, sir. ALGERNON: And, speaking of the science of Life, have you got the cucumber sandwiches cut for Lady Bracknell?

This early moment in the play contributes enormously to what the audience thinks about the aristocratic Algernon and his servant, Lane. If you were to talk about language in this scene, you could discuss Lane’s reserved replies: Are they funny? Do they indicate familiarity or sarcasm? How do you react to a servant who replies in that way? Or you could focus on Algernon’s witty responses. Does Algernon really care what Lane thinks? Is he talking more to hear himself? What does that say about how the audience is supposed to see Algernon? Algernon’s manner of speech is part of who his character is. If you are analyzing a particular performance, you might want to comment on the actor’s delivery of these lines: Was his vocal inflection appropriate? Did it show something about the character?

How language contributes to scene and mood

Ancient, medieval, and Renaissance plays often use verbal tricks and nuances to convey the setting and time of the play because performers during these periods didn’t have elaborate special-effects technology to create theatrical illusions. For example, most scenes from Shakespeare’s Macbeth take place at night. The play was originally performed in an open-air theatre in the bright and sunny afternoon. How did Shakespeare communicate the fact that it was night-time in the play? Mainly by starting scenes like this:

BANQUO: How goes the night, boy? FLEANCE: The moon is down; I have not heard the clock. BANQUO: And she goes down at twelve. FLEANCE: I take’t, ’tis later, sir. BANQUO: Hold, take my sword. There’s husbandry in heaven; Their candles are all out. Take thee that too. A heavy summons lies like lead upon me, And yet I would not sleep: merciful powers, Restrain in me the cursed thoughts that nature Gives way to in repose!

Enter MACBETH, and a Servant with a torch

Give me my sword. Who’s there?

Characters entering with torches is a pretty big clue, as is having a character say, “It’s night.” Later in the play, the question, “Who’s there?” recurs a number of times, establishing the illusion that the characters can’t see each other. The sense of encroaching darkness and the general mysteriousness of night contributes to a number of other themes and motifs in the play.

Productions and performances

Productions.

For productions as a whole, some important elements to consider are:

- Venue: How big is the theatre? Is this a professional or amateur acting company? What kind of resources do they have? How does this affect the show?

- Costumes: What is everyone wearing? Is it appropriate to the historical period? Modern? Trendy? Old-fashioned? Does it fit the character? What does their costume make you think about each character? How does this affect the show?

- Set design: What does the set look like? Does it try to create a sense of “realism”? Does it set the play in a particular historical period? What impressions does the set create? Does the set change, and if so, when and why? How does this affect the show?

- Lighting design: Are characters ever in the dark? Are there spotlights? Does light come through windows? From above? From below? Is any tinted or colored light projected? How does this affect the show?

- “Idea” or “concept”: Do the set and lighting designs seem to work together to produce a certain interpretation? Do costumes and other elements seem coordinated? How does this affect the show?

You’ve probably noticed that each of these ends with the question, “How does this affect the show?” That’s because you should be connecting every detail that you analyze back to this question. If a particularly weird costume (like King Henry in scuba gear) suggests something about the character (King Henry has gone off the deep end, literally and figuratively), then you can ask yourself, “Does this add or detract from the show?” (King Henry having an interest in aquatic mammals may not have been what Shakespeare had in mind.)

Performances

For individual performances, you can analyze all the items considered above in light of how they might have been different the night before. For example, some important elements to consider are:

- Individual acting performances: What did the actor playing the part bring to the performance? Was there anything particularly moving about the performance that night that surprised you, that you didn’t imagine from reading the play beforehand (if you did so)?

- Mishaps, flubs, and fire alarms: Did the actors mess up? Did the performance grind to a halt or did it continue?

- Audience reactions: Was there applause? At inappropriate points? Did someone fall asleep and snore loudly in the second act? Did anyone cry? Did anyone walk out in utter outrage?

Response papers

Instructors in drama classes often want to know what you really think. Sometimes they’ll give you very open-ended assignments, allowing you to choose your own topic; this freedom can have its advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, you may find it easier to express yourself without the pressure of specific guidelines or restrictions. On the other hand, it can be challenging to decide what to write about. The elements and topics listed above may provide you with a jumping-off point for more open-ended assignments. Once you’ve identified a possible area of interest, you can ask yourself questions to further develop your ideas about it and decide whether it might make for a good paper topic. For example, if you were especially interested in the lighting, how did the lighting make you feel? Nervous? Bored? Distracted? It’s usually a good idea to be as specific as possible. You’ll have a much more difficult time if you start out writing about “imagery” or “language” in a play than if you start by writing about that ridiculous face Helena made when she found out Lysander didn’t love her anymore.

If you’re really having trouble getting started, here’s a three point plan for responding to a piece of theater—say, a performance you recently observed:

- Make a list of five or six specific words, images, or moments that caught your attention while you were sitting in your seat.

- Answer one of the following questions: Did any of the words, images, or moments you listed contribute to your enjoyment or loathing of the play? Did any of them seem to add to or detract from any overall theme that the play may have had? Did any of them make you think of something completely different and wholly irrelevant to the play? If so, what connection might there be?

- Write a few sentences about how each of the items you picked out for the second question affected you and/or the play.

This list of ideas can help you begin to develop an analysis of the performance and your own reactions to it.

If you need to do research in the specialized field of performance studies (a branch of communication studies) or want to focus especially closely on poetic or powerful language in a play, see our handout on communication studies and handout on poetry explications . For additional tips on writing about plays as a form of literature, see our handout on writing about fiction .

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Carter, Paul. 1994. The Backstage Handbook: An Illustrated Almanac of Technical Information , 3rd ed. Shelter Island, NY: Broadway Press.

Vandermeer, Philip. 2021. “A to Z Databases: Dramatic Art.” Subject Research Guides, University of North Carolina. Last updated March 3, 2021. https://guides.lib.unc.edu/az.php?a=d&s=1113 .

Worthen, William B. 2010. The Wadsworth Anthology of Drama , 6th ed. Boston: Cengage.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Studying Here

- Find your course

- Fees and funding

- International students

- Undergraduate prospectus

- Postgraduate prospectus

- Studying abroad

- Foundation Year

- Placement Year

Your future career

- Central London campus

- Distance learning courses

- Prospectuses and brochures

- For parents and supporters

- Schools and colleges

Sign up for more information

Student life, accommodation.

- Being a student

Chat with our students

Support and wellbeing.

- Visit Royal Holloway

- The local area

- Virtual experience

Research & Teaching

Departments and schools.

- COP28 Forum

Working with us

- The library

Our history

- Art Collections

Royal Holloway today

- Equality, Diversity and Inclusion

- Recruiting our students

- Past events

- Environmental Sustainability

- Facts and figures

- Collaborate with us

- Governance and strategy

- Online shops

- How to find us

- Financial information

- Local community

- Legal Advice Centre

In this section

Find the right course

Online undergraduate prospectus

- Student life

What our students say

Explore our virtual experience

- Research and teaching

Research institutes and centres

Our education priorities

Drama and Creative Writing

Site search

Thank you for considering an application.

Here's what you need in order to apply:

- Royal Holloway's institution code: R72

Make a note of the UCAS code for the course you want to apply for:

- Drama and Creative Writing BA - WW48

- Click on the link below to apply via the UCAS website:

Key information

Duration: 3 years full time

UCAS code: WW48

Institution code: R72

Campus: Egham

Drama and Creative Writing (BA)

By combining the study of Creative Writing with Drama, you'll gain a deeper understanding of how theatre performance and creative writing interact - whether you specialise as a playwright, or choose to take the poetry or fiction options in creative writing.

Choosing to study Drama at Royal Holloway will put you at the centre of one of the largest and most influential Drama and Theatre departments in the world. You'll create performances, analyse texts, and bring a range of critical ideas to bear on both. On this course the text and the body, thinking and doing, work together. There's no barrier between theory and practice: theory helps you understand and make the most of practice, while practice sheds light on theory. By moving between the two, you'll find your place as an informed theatre-maker, and by studying a variety of practices, by yourself and with others, you'll get knowledge of the industry as a whole, and learn how your interests could fit into the bigger picture.

We are top-rated for teaching and research, with a campus community recognised for its creativity. Our staff cover a huge range of theatre and performance studies, but we're particularly strong in contemporary British theatre, international and intercultural performance, theatre history, dance and physical theatre, and contemporary performance practices.

Studying Creative Writing at one of the UK's most dynamic English departments will challenge you to develop your own critical faculties. Learning to write creatively, you'll develop your own writing practice.

Course units are taught by nationally and internationally known scholars, authors, playwrights and poets who are specialists in their fields who write ground-breaking books, talk or write in the national media and appear at literary festivals around the world.

- Complementary disciplines for the aspiring playwright.

- Explore creative skills including dance or puppetry.

- Assessment through performance and coursework.

- Specialise in different literary forms: poetry, playwriting or fiction.

- Build a portfolio, creating, critiquing and shaping your own artistic work.