Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 21 February 2018

Media use and brain development during adolescence

- Eveline A. Crone 1 &

- Elly A. Konijn 2

Nature Communications volume 9 , Article number: 588 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

188k Accesses

196 Citations

256 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive neuroscience

The current generation of adolescents grows up in a media-saturated world. However, it is unclear how media influences the maturational trajectories of brain regions involved in social interactions. Here we review the neural development in adolescence and show how neuroscience can provide a deeper understanding of developmental sensitivities related to adolescents’ media use. We argue that adolescents are highly sensitive to acceptance and rejection through social media, and that their heightened emotional sensitivity and protracted development of reflective processing and cognitive control may make them specifically reactive to emotion-arousing media. This review illustrates how neuroscience may help understand the mutual influence of media and peers on adolescents’ well-being and opinion formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Emotions and brain function are altered up to one month after a single high dose of psilocybin

Cortico-cortical transfer of socially derived information gates emotion recognition

Mechanisms linking social media use to adolescent mental health vulnerability

Introduction.

Media play a tremendously important role in the lives of today’s youth, who grow up with tablets and smartphones, and do not remember a time before the internet, and are hence called ‘digital natives’ 1 , 2 . The current generation of the adolescents lives in a media-saturated world, where media is used not only for entertainment purposes, such as listening to music or watching movies, but is also used increasingly for communicating with peers via WhatsApp, Instagram, SnapChat, Facebook, etc. Taken together, these media-related activities comprise roughly 6–9 h of an American youth’s day, excluding home- and schoolwork ( https://www.commonsensemedia.org/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-infographic ) 3 , 4 . Social media enable people to share information, ideas or opinions, messages, images and videos. Today, all kinds of media formats are constantly available through portable mobile devices such as smartphones and have become an integrated part of adolescents’ social life 5 .

Adolescence, which is defined as the transition period between childhood and adulthood (approximately ages 10–22 years, although age bins differ between cultures), is a developmental stage in which parental influence decreases and peers become more important 6 . Being accepted or rejected by peers is highly salient in adolescence, also there is a strong need to fit into the peer group and they are highly influenced by their peers 7 . Therefore, it is imperative that we understand how adolescents process media content and peers’ feedback provided on such platforms. Adolescents’ social lives in particular seem to occur for a large part through smartphones that are filled with friends with whom they are constantly connected (cf. “A day not wired is a day not lived” 5 , 8 ). This is where they monitor their peer status, check peers’ feedback, rejection and acceptance messages, and encounter peers as (idealized) images 9 on screens 5 , 8 , 10 . Likely, this plays an important role in adolescent development, and we therefore focus primarily on adolescents’ social media use 11 . Most media research to date is based on correlational and self-report data, and would be strengthened by integrating experimental paradigms and more objectively assessed behavioral, emotional, and neural consequences of experimentally induced media use.

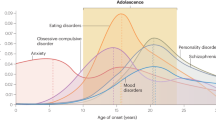

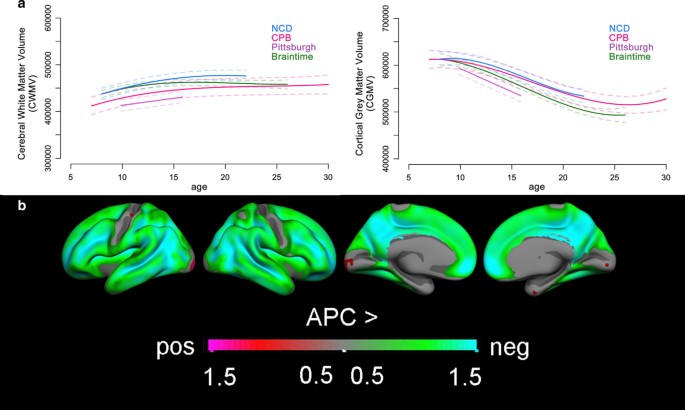

Recently, cognitive neuroscience studies have used structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine how the adolescent brain changes over the course of the adolescent years 6 . The results of several studies demonstrate that cognitive and socio-affective development in adolescence is accompanied by extensive changes in the structure and function of the adolescent brain 6 . Structurally, white matter connections increase, allowing for more successful communication between different areas of the brain 12 . The maturation of these connections is related to behavioral control, for example, connections between the prefrontal cortex and the subcortical striatum mediate age-related improvements in the ability to wait for a reward 13 . In addition to these changes in white matter connections, neurons in the brain grow in number between conception and childhood, with greatest synaptic density in early childhood. This increase in synaptic density co-occurs with synaptic pruning, and pruning rates increase in adolescence, resulting in a decrease in synaptic density in late childhood and adolescence 14 . Structural MRI research revealed that the peak in grey matter volume probably occurs before the age of 10 years, but dynamic non-linear changes in grey matter volume continue over the whole period of adolescence, and the timing is region-specific 15 . Interestingly, changes in grey matter volume are observed most extensively in brain regions that are important for social understanding and communication such as the medial prefrontal cortex, superior temporal cortex and temporal parietal junction 16 . Figure 1 displays the extensive changes in the human cortex during adolescence.

Longitudinal changes in brain structure across adolescence (ages 8–30). a Consistent patterns of change across four independent longitudinal samples (391 participants, 852 scans), with increases in cerebral white matter volume and decreases in cortical grey matter volume (adapted from Mills et al., 2016, NeuroImage 105 ). b Of the two main components of cortical volume, surface area and thickness, thinning across ages 8 to 25 years is the main contributor to volume reduction across adolescence, here displayed in the Braintime sample (209 participants, 418 scans). Displayed are regional differences in annual percentage change (APC) across the whole brain, the more the color changes in the direction of green to blue, the larger the annual decrease in volume (adapted from Tamnes et al., 2017, J Neuroscience 15 )

Given that brain regions involved in many social aspects of life are undergoing such extensive changes during adolescence, it is likely that social influences—which also occur through the use of social media as the internet connects adolescents to many people at once—are particularly potent at this age in coalescence with their media use. Also, subcortical brain regions undergo pronounced changes during adolescence 17 . There is evidence that the density of grey matter volume in the amygdala, a structure associated with emotional processing, is related to larger offline social networks 18 , as well as larger online social networks 19 , 20 . This suggests an important interplay between actual social experiences, both offline and online, and brain development.

This review brings together research on media use among adolescents with neural development during adolescence. We will specifically focus on the following three aspects of media exposure of interest to adolescent development 21 : (1) social acceptance or rejection, (2) peer influence on self-image and self-perception, and (3) the role of emotions in media use. Finally, we discuss new perspectives on how the interplay between media exposure and sensitive periods in brain development may make some individuals more susceptible to the consequences of media use than others.

Being accepted or rejected online

Experiencing acceptance or rejection when communicating via digital media is an impactful social experience. Extensive research, including large meta-analyses, has demonstrated that social rejection in a computerized environment can be experienced similarly as face-to-face rejection and bullying, although the prevalence of cyberbullying is generally lower 22 , 23 (and studies vary widely: prevalence rates depend on how cyberbullying is defined and measured). In all, cyberbullying peaks during adolescence 24 and large overlap has been found between victims and bullies. In part, this overlap could be explained by victimized adolescents seeking exposure to antisocial and risk behavior media content 25 . The next subsections will describe recent discoveries in neuroscience on the neural responses to online rejection and acceptance.

Neural responses to online social rejection

The emotional and neural effects of being socially excluded have been well captured by research involving the Cyberball Paradigm 26 ( https://cyberball.wikispaces.com/ ). Cyberball is a virtual ball-toss game in which the study participant tosses a ball with two simulated players (so-called confederates) via a screen. After a round of fair play, the confederates, who only throw the ball to each other, exclude the participant in the rejection condition. This results in pronounced negative effects on the participants’ feeling to belong, ostracism, sense of control, and self-esteem 26 . Even though the paradigm was not designed to study online rejection as it occurs today on social media, the findings of prior Cyberball studies may provide an important starting point for understanding the processes involved in online rejection. In fact, inspired by Cyberball, a Social Media Ostracism paradigm has recently been developed by applying a Facebook format to study the effects of online social exclusion 27 .

Using functional MRI (fMRI), researchers have observed increased activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and insula after participants experienced exclusion, possibly signaling increased arousal and negative affect 28 . In addition, stronger activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is observed in adolescents and young adults with a history of being socially excluded 29 , maltreated 30 , or insecure attachment, whereas spending more time with friends reduced ACC response in adolescents to social exclusion 31 . This may possibly protect adolescents against the negative influence of ostracism or cyberbullying, although all these studies are correlational. Therefore, it remains to be determined whether environment influences brain development or vice versa. Moreover, ACC and insula activity have also been explained as signaling a highly significant event because the same regions are also active when participants experience inclusion 32 . Furthermore, studies with adolescents observed specific activity in the ventral striatum 33 , and in the subgenual ACC when adolescents were excluded in the online Cyberball computer game 34 , 35 , the latter region is often implicated in depression 36 . Thus, being rejected was associated with activity in brain regions that are also activated when experiencing salient emotions 37 , 38 . These studies may indicate a specific window of sensitivity to social rejection in adolescence, which may be associated with the enhanced activity of striatum and subgenual ACC in adolescence 33 , 36 .

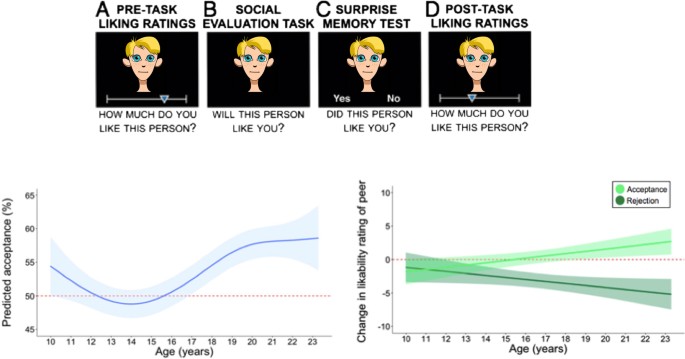

Social rejection has also been studied using task paradigms that mirror online communication more specifically. In the social judgment paradigm, participants enter a chat room, where others can judge their profile pictures based on first impression 39 . This can result in being rejected or accepted by others in a way that is directly comparable to social media environments where individuals connect based on first impression (for example,’liking’ on Instagram). A developmental behavioral study (participants between 10 and 23 years) showed that young adults expected to be accepted more than adolescents. Moreover, these adults, relative to adolescents, adjusted their evaluations of others more based on whether others accepted or rejected them, possibly indicating self-protecting biases 40 (Fig. 2 ). Neuroimaging studies revealed that, being rejected based only on one’s profile pictures resulted in increased activity in the medial frontal cortex, in both adults 41 and children 42 , and studies in adolescents showed enhanced pupil dilation, a response to greater cognitive load and emotional intensity, to rejection 43 .

Adolescents’ expectations and adjustments of being liked and liking others. Social evaluation study in which participants between ages 10 and 23 years rated other peers on whether they liked the other person, whether they believed the other would like them, and a post scan rating of liking the other person after having received acceptance or rejection feedback from the other person. The faces used in this adaptation of figure are cartoon approximations of the original stimuli used in ref. 40 ; to see the original stimuli, please refer to ref. 40 . The left graph shows that adolescents expect least to be liked by the other before receiving feedback (question B). The right graph shows a developmental increase in distinguishing between liking and disliking based on feedback from the other person (question D). (Adapted with permission from Rodman, 2017, PNAS 40 )

Taken together, these studies suggest that adolescents show stronger rejection expectation than adults, and subgenual ACC and medial frontal cortex are critically involved when processing online exclusion or rejection. In the next section, we describe how the brain of adolescents and adults respond to receiving positive feedback and likes from others.

Neural responses to online social acceptance

The positive feeling of social acceptance online is endorsed through the receipt of likes, one’s cool ratio (i.e., followers > following; Business Insider, 11 June 2014: http://www.businessinsider.com/instagram-cool-ratio-2014–6?international=true&r=US&IR=T .) or popularity, positive comments and hashtags, among other forms of reward 44 , 45 . Neuropsychological research showed that being accepted evokes activation in similar brain regions, as when receiving other rewards such as money or pleasant tastes 38 . Most pronounced activity was found in the ventral striatum, together with the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and ventral tegmental area, which is consistently reported as a key region in the brain for the subjective experience of pleasure and reward 46 , including social rewards 47 . Likewise, being socially accepted through likes in the chat room task resulted in increased activity in the ventral striatum in children 42 , adolescents 48 , 49 and adults 41 , 50 . This response is blunted in adolescents who experience depression 36 , or who have experienced a history of maternal negative affect 51 . Apparently, prior social experiences—such as parental relations—are an important factor for understanding which adolescents are more sensitive to the impact of social media 51 . In this regard, media research showed that popularity moderates depression 10 and that attachment styles and loneliness increases the likelihood to seek socio-affective bonding with media figures 52 .

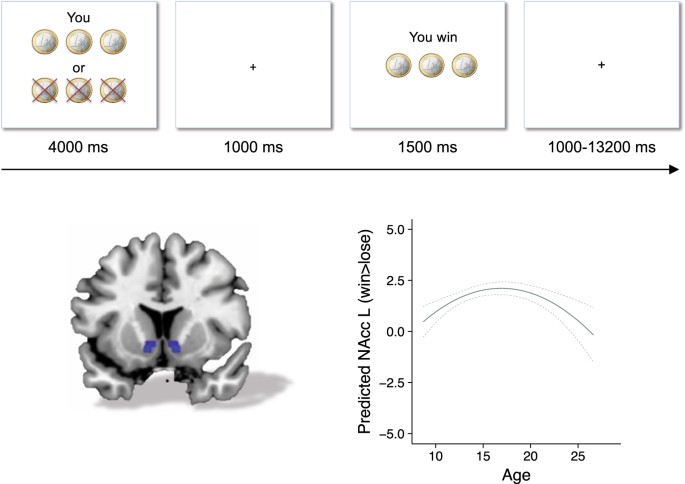

Interestingly, several studies and meta-analyses using gambling and reward paradigms have reported that activity in the ventral striatum to monetary rewards peaks in mid-adolescence 53 , 54 , 55 (Fig. 3 ; see Box 1 for views on adolescent risk taking in various contexts). These findings may suggest general reward sensitivity in adolescence such that reward centers that respond to monetary reward may also show increased sensitivity to social reward in adolescence. Social reward sensitivity may be a strong reinforcer in social media use. A prior study in adults showed that activity in the ventral striatum in response to an increase in one’s reputation, but not wealth, predicted frequency of Facebook use 56 . In a similar vein, adolescents showed sensitivity to “likes” of peers on social media 44 , 57 . In a controlled experimental study, adolescents showed more activity in the ventral striatum when viewing images with many vs. few likes, and this activation was stronger for older adolescents and college students compared to younger adolescents 57 . Thus, the same region that is active when being liked on the basis of first impression of a profile picture 48 , is also activated when viewing images that are liked by others, especially in mid-to-late adolescence, possibly extending into adulthood 57 (see also ref. 58 for similar findings on music preference). These findings suggest that heightened reward sensitivity in mid-adolescence that was previously observed for monetary rewards 53 may also be present for social rewards such as likes on Instagram. However, further research is needed to examine whether this is a specific sensitivity in early, mid or late adolescence, or perhaps this social reward sensitivity emerges in adolescence and remains in adulthood.

Longitudinal neural developmental pattern of reward activity in adolescence. Longitudinal two-wave neural developmental pattern of nucleus accumbens activation during winning vs. losing, based on 249, and 238 participants who were included on the first and second time point, respectively (leading to 487 included brain scans in total). A quadratic pattern of brain activity was observed in the nucleus accumbens for the contrast winning > losing money in a gambling task, with highest reward activity in mid-adolescence. (Adapted with permission from Braams et al. 55 )

Online peer influence

In addition to adolescents’ sensitivity to the feeling of belonging to the peer group 59 , the peer group also has a strong influence on opinions and decision-making 60 . Peers can exert a strong influence on adolescents through user-generated content on social media 5 , 61 . Co-viewing, sharing, and discussing media content with peers is common practice among adolescents in line with their developmental stage in which peers become more important than others. For example, adolescent girls often share pictures and comment on the “ideal” degree of slimness of the models they see via media when deciding how a ‘normal’ body should actually look 62 , 63 . Several recent neuroimaging studies, summarized below, have examined how the adolescent brain responds to peer comments about others and self, and subsequent behavioral adjustments and opinion changes. Even though not all of these designs were specific for online environments, the findings provide important starting points for understanding how adolescents are influenced by peer feedback in an online environment.

Neural responses to online peer feedback

Neuroimaging studies in adolescents showed that peer feedback indeed influences adolescents’ behavior. Neural correlates may provide more insight in the specific parts of the feedback that drives these behavioral sensitivities 64 . One way this is demonstrated is by having individuals rate certain products such as music preference or facial attractiveness. After their initial rating, participants received feedback from others, which was either congruent or incongruent with their initial rating. Afterwards, individuals made their ratings again, and the researchers analyzed whether behavior changed in the direction of the peer feedback. Indeed, both adults and adolescents adjusted their behavior towards the group norm 58 , 64 , demonstrating general sensitivity to peer influence. Furthermore, when receiving peer feedback that did not match their own initial rating, participants showed enhanced activity in the ACC and insula, two regions involved in detecting norm violations 58 , 65 . More specifically, increased ACC activity was associated with more adjustment to fit peer feedback norms in adolescents 58 .

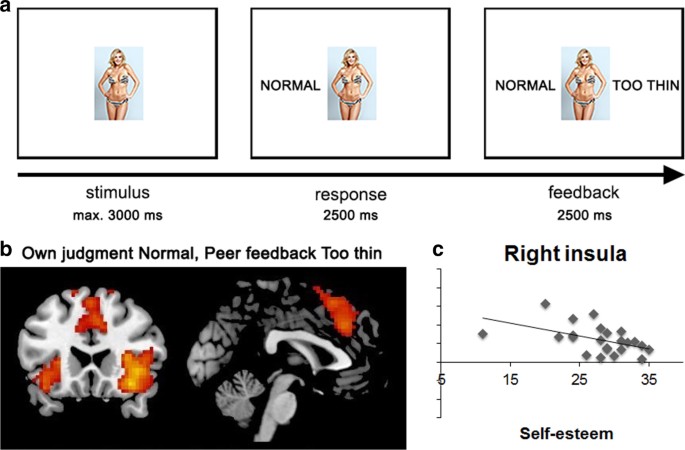

Peer feedback effects are not only found for how individuals rate products, but also can strongly influence how they view themselves. Girls are especially sensitive to pressure for media’s thin-body ideal, and peer feedback supporting this ideal is associated with more body dissatisfaction 62 , 63 . We recently showed that norm-deviating feedback on ideal body images resulted in activity in the ACC-insula network in young females (18–19-years), which was stronger for females with lower self-esteem 66 (Fig. 4 ). Interestingly, the girls also adjusted their ratings on what they believed was a normal or too-thin looking body in the direction of the group norm. Together, these findings suggest that peer feedback through social media can influence the way adolescents look at themselves and others.

The Body Image Paradigm to study combined media and peer influence. This paradigm is designed for experiments to study the influence of peers on body image perception. a Participants are presented with a bikini model, and they can make a judgment whether the model is too thin or of normal weight. Their response appears on the left side of the model. Then, they are presented with ostensible peer feedback (the peer norm). b When this feedback deviates from their own judgment, this is associated with increased activity in dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and bilateral insula, regions often implicated in processing norm violations. c Responses are larger for participants with lower self-esteem (Adapted from Van der Meulen et al. 66 )

Neural responses to prosocial peer feedback

Interestingly, however, we also found that peer feedback can influence social behavior in a prosocial direction, for example, by having peers positively evaluate prosocial behavior that benefits the group. Neuroimaging studies of social cognition have demonstrated that thinking about other peoples’ intentions or feelings is associated with activity in a network of regions, including medial prefrontal cortex, the superior temporal sulcus and the temporal parietal junction, also referred to as the social brain network 67 . In an online peer influence study, adolescents could donate money to the group, which would benefit not only themselves but also others. Prior to the study, the participants met the other participants (confederate peers) that were not part of the group that was dividing the money. These peers, however, gave online feedback through likes on the participants’ choices. More likes were given when participants donated more to the group. This feedback was followed by higher donations 68 , and was associated with enhanced activation in the social brain network, such as the medial frontal cortex, temporal parietal junction and superior temporal sulcus 69 . Notably, the change in social brain activity in the peer feedback condition was more pronounced for younger adolescents (ages 12–13-years) compared to mid-adolescents (15–16-years) 69 . Together, these studies suggest that early adolescence may be an especially sensitive period for social media influences in risk-perception 60 as well as prosocial directions 69 . These findings fit well with Blakemore and Mills’ 6 suggestion that, adolescence may be a sensitive period for social reorientation and social brain development, although results vary regarding whether sensitive periods are more pronounced in early or mid-adolescence. Understanding the specific sensitive windows may be important to target future interventions. Therefore, future research is needed to examine whether this is a specific sensitivity in early-to-mid-adolescence, or whether and how social reward sensitivity remains in adulthood.

Precedence of emotions and impulsivity

A third factor that affects how adolescents process (social) media relates to the intense emotional experiences that usually accompany adolescence 70 . Emotional needs may guide adolescents’ media use and processing; for example, feeling lonely may ease the path to connect to a media figure or to rely on social media for one’s social interaction 52 , 71 , 72 . Furthermore, being engaged in media fare may evoke strong emotional reactions, such as when playing violent video games or when experiencing online rejection 73 , 74 . Adolescents in particular appear to be guided by their emotions in how they use and process media 5 . For example, the degree of anger and frustration experienced by early-to-mid adolescent victims of bullying was associated with increased exposure to media fare portraying antisocial, norm-crossing and risk-taking behaviors over time, making these youngsters more likely to become bullies themselves 25 . Another study showed that anger instigated a more lenient moral tolerance of antisocial media content in early adolescents but not in young adults 74 . Furthermore, adolescent victims of bullying who regulated their anger through maladaptive strategies (e.g., other-blame, rumination) showed higher levels of cyberbullying themselves 25 .

Neural responses related to retaliation and emotion regulation

Neuroscience studies can potentially provide more insight in the moral leniency following adolescents’ anger. Neuroscience research on adolescent development has shown that the development of the prefrontal cortex, an important region for emotion regulation, matures until early adulthood 15 , 75 . A better understanding of the interactions between brain regions that show direct responses to emotional content, and brain regions that help to regulate these responses can possibly elucidate how adolescents regulate their behavior related to media-based interactions.

Several studies examined this question by focusing on anger following rejection. Rejected-based anger often leads to retaliatory actions. Several paradigms have also shown that adolescents are more aggressive after being rejected online. For example, they gave longer noise blasts and shared less of their resources with people who previously rejected them in an online environment 41 , 73 , 76 . More activity in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) after rejection was associated with less subsequent aggression 41 and more giving 76 , possibly indicating that increased activity in the DLPFC helps individuals to control their anger following rejection. Other research showed changes in neural coupling when young men played violent video games 77 . Thus, social rejection can evoke anger, but some adolescents may be better at regulating these emotions than others. Adolescents who regulate these emotions better show stronger activity in DLPFC, a region known to be involved in self-control 41 , 75 .

Applying adaptive emotion regulation strategies (e.g., putting into perspective, refocusing, reappraisal) possibly requires enhanced demands on DLPFC 78 . Possibly, the late maturation of the DLPFC, together with heightened emotional reactivity, may make adolescents more likely to be influenced by media content. For example, research showed that emotional experiences biased participants’ perception of media footage: despite being told beforehand that the footage contained fiction-based materials, they attributed significantly higher levels of realism to it under conditions of emotional arousal than in a neutral state 79 . Subsequently, participants attributed more information value to the fiction-based footage up to similar levels as to the reality-based clip.

One possible direction to better understand how adolescents deal with emotional media content is by examining parallel processes. It is likely that engaging in media is associated with multiple processes 79 such as the fast processing of emotions associated with engagement, sensation-seeking and emotional responses to media content, as well as more reflective and relatively slower processes, such as perspective taking and emotion regulation 80 . We interpret such parallel processing as coordinated networks of an inter-related imbalance between heightened emotional responsivity and protracted development of reflective processing and cognitive control 75 . For example, adolescents show a peak in neural responsivity to emotional faces in the ventral striatum and anterior insula, compared to children and adults 81 , 82 . In addition, adolescents show protracted development of social brain regions implicated in perspective taking 6 , 83 , and flexible engagement of lateral prefrontal cortex, possibly depending on personal goals 84 . When media encounters are emotionally gripping, such parallel processing may explain why people may take (fake) information from media as real—‘it just feels real’ 79 . The emotional response seems to blur the borders between fact and fake; the instantaneous response based on emotional or accompanying sensory feedback apparently takes (momentary) control precedence over cognitive reflection and biases subsequent information processing 79 . These findings may perhaps also explain how social reality can be perceived in accordance to how the world is represented in emotion-arousing, sensationalist or populist media messages, even when it concerns so-called “fake news”. In all, these suggestions call for further empirical testing, specifically also comparing adolescents and adults, in which the pattern of brain changes is combined with behavioral research and opinion formation.

Another intriguing question for future research is whether regulation or control of media-generated emotions can be trained. It was previously found that training of executive functions is associated with increased activity in DLPFC 85 , but it remains an open question whether activity in DLPFC can be influenced by (aggression) regulation training and behavioral control, and whether this results in changes in the functional and structural properties of the brain. If such training were possible, video games and immersive virtual environments might provide even more useful training environments. In this respect, promising projects are ongoing, testing the use of biofeedback videogames to help youth cope with stress and anxiety and identify physiological markers, and patterns of emotion regulation 86 . Game interventions are also developed to help children to cope effectively with anxiety-inducing situations 87 . These enrichment and training programs may also be useful to test specific media sensitivities by controlling the amount of media exposure. Such designs will have important benefits over studies examining correlations between naturally occurring behaviors and developmental outcomes, which often do not allow for control of other variables such as temperament or environmental changes.

Taken together, individuals differ in how they respond to media content, especially when these evoke emotional responses or are evaluated in an emotion-aroused state. There are only preliminary studies available that link these individual differences to brain development, but possibly the regulating role of DLPFC is important to control emotional responses to rejection, fake news, violent video games, or appealing ideals. These are all questions that need to be addressed in future research, but are highly relevant given the developmental stage and time adolescents engage with these prevalent forms of media.

Outlook for future studies

We described research in three directions that we believe are crucial in understanding how the omnipresent use of (social) media among today’s adolescents may influence them, through the following: (1) social rejection and acceptance, (2) peer influence on opinions of self and others, and (3) emotion precedence in media use and effects. We have provided a first overview of how neuroscience research may aid in a better understanding of these influences in a mediated context. However, study results appear to vary regarding the specific adolescent age ranges; sometimes effects seem specific for early- or mid-adolescents, while in other studies adolescents and (young) adults do not differ and the indicated age ranges also vary widely (e.g., for some, ‘late adolescence’ is between 13 and 17 years old, whereas in other reports, 17–25 years of age is referred to as ‘late’, see also ref. 88 ). Most adolescent samples are relatively older, whereas early adolescents (aged 10–15) are understudied and seem of particular interest in regards of sensitivity in these three areas. Therefore, further research is needed to align specific age ranges to developmental stages.

Current media technology opens possibilities to understand sensitivities to media and peers in adolescence. For example, YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram provide excellent environments to study combined with media content and peers’ feedback in adolescence 27 , 89 . Moreover, such social media platforms introduced so-called user-generated content 90 and options to present and express oneself in media environments have increased tremendously, thereby increasing media’s social functions. Taking the ethical aspects of performing social media research into account, as it can impinge on users’ privacy, social media devices also provide great opportunities to understand how media exposure affects day-to-day fluctuations in mood and self-esteem.

A critical question that remains largely unanswered is how adolescents’ abundant media use may impact them developmentally in terms of structural brain development, functional brain development, and related behavior. The scientific evidence thus far is still scarce and results are mixed 91 , 92 . For example, digital-screen time and mental well-being appear to be best described by quadratic functions with moderate use not intrinsically harmful 93 . Several recent studies have shown that habitual use is associated with a reduced ability to delay gratification 94 , but can also have positive consequences such as increased ability to flexibly switch between tasks 95 and feeling socially connected 96 . Adolescents who spend more time on their mobile devices may engage less in ‘real’ offline social interactions and the consequences of these communication changes are not yet well understood. Perhaps, consequences differ among those who experience their online interactions as similar to their offline interactions, or as separate worlds. Important moderators and mediators should also be taken into account to understand how online communication is processed. Finally, being constantly online also affects sleep patterns, which impacts mood as well 97 . In all, the majority of these studies are based on self-reported new media use and outcomes. Integrating both experimental methods and neuroscientific insights may advance our understanding of who is susceptible under which circumstances to which effects, positive or negative.

In this review, we described the emerging body of research focused on how new media use is processed by the still developing adolescent brain. In particular, we highlighted the neural systems that are associated with behaviors that are important for social media use, including social reward processing, emotion-based processing, regulation, and mentalizing about others 98 . As these neural systems are still underdeveloped and undergoing significant changes during adolescence, they may contribute to sensitivity to online rejection, acceptance, peer influence, and emotion-loaded interactions in media-environments. In future research, it will be important to understand these processes better, especially the specific developmental sensitivities, as well as to understand which adolescents are more and less susceptible for beneficial or undesirable media influences.

The review of the literature suggests that peer sensitivities are possibly larger in adolescents than in older age groups. Peer influence effects have been well demonstrated in adolescent decision-making research, showing that adolescents take more risks in the presence of peers and when peers stimulate risk-taking 99 . This seems to hold similarly for peer influence online through online comments, also with less risky behaviors 62 . These findings have been interpreted to suggest that adolescents have a strong need to follow norms of their peer group and show in-group adherence 100 . There is a strong need for studies that experimentally test whether increased influence of peers, possibly through developing social brain regions, combined with strong sensitivity to acceptance and rejection, makes adolescence a tipping point in development for how social media can influence their self-concept and expectations of self and others. It is likely that these sensitivities are not related to one process specifically, but the combination of developmental brain networks and associated behaviors 75 , 84 . A critical question for future research is how neural correlates observed in this review predict future behavior or emotional responses in adolescents.

Social media have at least the following two important functions: (i) socially connect with others (the need to belong) and (ii) manage the impression individuals make on others (reputation building, impression management, and online self-presentation) 98 . The emerging trajectory of acceptance sensitivity, peer ‘obedience’, and emotion precedence may make adolescents specifically susceptible to sensationalist and fake news, unrealistic self-expectations, or regulating emotions through adverse use of media. Important questions for future research relate to unraveling whether adolescents are more sensitive to these news items than children and adults, who is most sensitive to which kind of media influence, how (one-sided) media use may influence adolescent development over time, and understand not only the risks but also how media provides opportunities for positive development, such as engaging with friends, forming new peer relations, and experiment with uncertainties or overcoming fears. Studying the interplay between media use and sensitive periods in brain development will provide important directions for understanding how media may impact youth and who is most vulnerable and under which conditions. Key questions for future research are to understand whether recent changes in media usage, delivery, dosage, and levels of engagement (e.g., as more active creators and participants, for example) are leading to different or amplified neural responses in adolescents relative to adults. Using longitudinal research, it will be important to test whether there is evidence that the still developing adolescent brain is more sensitive to, or more likely to be shaped by these changing patterns of media usage. 1

Box 1 Multiple perspectives on adolescent risk-taking

Adolescence is often defined as a period of increased risk taking and sensation-seeking, this is observed across cultures 101 and across species 102 . However, the way risk-taking is expressed differs across generations. In middle ages, risk-taking in adolescence took place through reckless fights and wars. In contrast, in the late 20th century and early 21st century, adolescents were more prone towards risk-taking in context of alcohol, sex, and drug experimentation 103 . Recently, through social media, new forms of risk-taking are expressed, such as excessive or unlimited self-disclosure or sexting 104 . These observations suggest that social media may be the new way in which sensation-seeking behavior is expressed, which is possibly an adolescent-specific tendency to explore and learn to adapt to new social environments.

Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. Horizon 9 , 1–6 (2001).

Google Scholar

Ståhl, T. How ICT savvy are digital natives actually? Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 12 , 89–108 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Rideout, V. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens (Common Sense Media, San Francisco, 2015).

Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., Ólafsson, K. & Haddon, L. Children’s online risks and opportunities: Comparative findings from EU Kids Online and Net Children Go Mobile http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/60513/ . (2014).

Konijn, E. A., Veldhuis, J., Plaisier, X. S., Spekman, M. & den Hamer, A. H. in The Handbook of Psychology of Communication Technology (ed. Sundar. S.) (Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ, 2015).

Blakemore, S. J. & Mills, K. L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 65 , 187–207 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Sebastian, C. L. et al. Developmental influences on the neural bases of responses to social rejection: implications of social neuroscience for education. Neuroimage 57 , 686–694 (2011).

Valkenburg, P. M. & Taylor Piotrowski, J. How Media Attract and Affect Youth (Yale University Press., Yale, 2017).

Ma, J. & Yang, Y. What can we know from selfies - An exploratory study on selfie and the implication for marketers. In Global Marketing Conference at Hong Kong Proceedings 597–601 (Global Alliance of Marketing & Management Associations, 2016).

Nesi, J. & Prinstein, M. J. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 43 , 1427–1438 (2015).

Wartella, E. et al. What kind of adults will our children become? the impact of growing up in a media-saturated world. J. Child. Media 10 , 13–20 (2016).

Ladouceur, C. D., Peper, J. S., Crone, E. A. & Dahl, R. E. White matter development in adolescence: the influence of puberty and implications for affective disorders. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2 , 36–54 (2012).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Achterberg, M., Peper, J. S., Van Duijvenvoorde, A. C., Mandl, R. C. & Crone, E. A. Fronto-striatal white matter integrity predicts development in delay of gratification: a longitudinal study. J. Neurosci. 36 , 1954–1961 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Huttenlocher, P. R. Morphometric study of human cerebral cortex development. Neuropsychologia 28 , 517–527 (1990).

Tamnes, C. K. et al. Development of the cerebral cortex across adolescence: a multisample study of inter-related longitudinal changes in cortical volume, surface area, and thickness. J. Neurosci. 37 , 3402–3412 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mills, K. L., Lalonde, F., Clasen, L. S., Giedd, J. N. & Blakemore, S. J. Developmental changes in the structure of the social brain in late childhood and adolescence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9 , 123–131 (2014).

Goddings, A. L. et al. The influence of puberty on subcortical brain development. Neuroimage 88 , 242–251 (2014).

Bickart, K. C., Wright, C. I., Dautoff, R. J., Dickerson, B. C. & Barrett, L. F. Amygdala volume and social network size in humans. Nat. Neurosci. 14 , 163–164 (2011).

Von Der Heide, R., Vyas, G. & Olson, I. R. The social network-network: size is predicted by brain structure and function in the amygdala and paralimbic regions. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9 , 1962–1972 (2014).

Kanai, R., Bahrami, B., Roylance, R. & Rees, G. Online social network size is reflected in human brain structure. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279 , 1327–1334 (2012).

Pfeifer, J. H. & Blakemore, S. J. Adolescent social cognitive and affective neuroscience: past, present, and future. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 7 , 1–10 (2012).

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N. & Lattanner, M. R. Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 140 , 1073–1137 (2014).

Modecki, K. L., Minchin, J., Harbaugh, A. G., Guerra, N. G. & Runions, K. C. Bullying prevalence across contexts: a meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. J. Adolesc. Health 55 , 602–611 (2014).

Tokunaga, R. S. Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comput. Human. Behav. 26 , 277–287 (2010).

den Hamer, A. H. & Konijn, E. A. Adolescents’ media exposure may increase their cyberbullying behavior: a longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. Health 56 , 203–208 (2015).

Williams, K. D. & Jarvis, B. Cyberball: a program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behav. Res. Methods 38 , 174–180 (2006).

Wolf, W. et al. Ostracism online: a social media ostracism paradigm. Behav. Res. Method 47 , 361–373 (2014).

Cacioppo, S. et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of functional imaging studies of social rejection. Sci. Rep. 3 , 2027 (2013).

Will, G. J., van Lier, P. A., Crone, E. A. & Guroglu, B. Chronic childhood peer rejection is associated with heightened neural responses to social exclusion during adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 44 , 43–55 (2015).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

van Harmelen, A. L. et al. Childhood emotional maltreatment severity is associated with dorsal medial prefrontal cortex responsivity to social exclusion in young adults. PLoS ONE 9 , e85107 (2014).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Masten, C. L., Telzer, E. H., Fuligni, A. J., Lieberman, M. D. & Eisenberger, N. I. Time spent with friends in adolescence relates to less neural sensitivity to later peer rejection. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 7 , 106–114 (2012).

Dalgleish, T. et al. Social pain and social gain in the adolescent brain: A common neural circuitry underlying both positive and negative social evaluation. Sci. Rep. 7 , 42010 (2017).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Vijayakumar, N., Cheng, T. W. & Pfeifer, J. H. Neural correlates of social exclusion across ages: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of functional MRI studies. Neuroimage 153 , 359–368 (2017).

Masten, C. L. et al. Neural correlates of social exclusion during adolescence: understanding the distress of peer rejection. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 4 , 143–157 (2009).

Moor, B. G. et al. Social exclusion and punishment of excluders: neural correlates and developmental trajectories. Neuroimage 59 , 708–717 (2012).

Silk, J. S. et al. Increased neural response to peer rejection associated with adolescent depression and pubertal development. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9 , 1798–1807 (2014).

Lieberman, M. D. & Eisenberger, N. I. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex is selective for pain: Results from large-scale reverse inference. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 15250–15255 (2015).

Lieberman, M. D. & Eisenberger, N. I. Neuroscience. Pains and pleasures of social life. Science 323 , 890–891 (2009).

Guyer, A. E., McClure-Tone, E. B., Shiffrin, N. D., Pine, D. S. & Nelson, E. E. Probing the neural correlates of anticipated peer evaluation in adolescence. Child. Dev. 80 , 1000–1015 (2009).

Rodman, A. M., Powers, K. E. & Somerville, L. H. Development of self-protective biases in response to social evaluative feedback. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114 , 13158–13163 (2017).

Achterberg, M., van Duijvenvoorde, A. C., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. & Crone, E. A. Control your anger! the neural basis of aggression regulation in response to negative social feedback. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11 , 712–720 (2016).

Achterberg, M. et al. The neural and behavioral correlates of social evaluation in childhood. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 24 , 107–117 (2017).

Silk, J. S. et al. Peer acceptance and rejection through the eyes of youth: pupillary, eyetracking and ecological data from the Chatroom Interact task. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 7 , 93–105 (2012).

Sherman, L. E., Payton, A. A., Hernandez, L. M., Greenfield, P. M. & Dapretto, M. The power of the like in adolescence: effects of peer influence on neural and behavioral responses to social media. Psychol. Sci. 27 , 1027–1035 (2016).

Burrow, A. L. & Rainone, N. How many likes did I get? purpose moderates links between positive social medial feedback and self-esteem. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 69 , 232–236 (2017).

Haber, S. N. & Knutson, B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology 35 , 4–26 (2010).

Guroglu, B. et al. Why are friends special? Implementing a social interaction simulation task to probe the neural correlates of friendship. Neuroimage 39 , 903–910 (2008).

Gunther Moor, B., van Leijenhorst, L., Rombouts, S. A., Crone, E. A. & Van der Molen, M. W. Do you like me? Neural correlates of social evaluation and developmental trajectories. Soc. Neurosci. 5 , 461–482 (2010).

Guyer, A. E., Choate, V. R., Pine, D. S. & Nelson, E. E. Neural circuitry underlying affective response to peer feedback in adolescence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 7 , 81–92 (2012).

Davey, C. G., Allen, N. B., Harrison, B. J., Dwyer, D. B. & Yucel, M. Being liked activates primary reward and midline self-related brain regions. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 31 , 660–668 (2010).

PubMed Google Scholar

Tan, P. Z. et al. Associations between maternal negative affect and adolescent’s neural response to peer evaluation. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 8 , 28–39 (2014).

Konijn, E. A. & Hoorn, J. F. in The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects (ed. Roessler, P., Hoffner, C. A. & Zoonen, L. v.) 1–15 (Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, Hoboken, NJ, 2017).

Silverman, M. H., Jedd, K. & Luciana, M. Neural networks involved in adolescent reward processing: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage 122 , 427–439 (2015).

Schreuders, L., Braams, B. R., Peper, J. S., Guroglu, B. & Crone, E. A. Contributions of reward sensitivity to ventral striatum activity across adolescence and adulthood. Child Dev. In press (2018).

Braams, B. R., van Duijvenvoorde, A. C., Peper, J. S. & Crone, E. A. Longitudinal changes in adolescent risk-taking: a comprehensive study of neural responses to rewards, pubertal development, and risk-taking behavior. J. Neurosci. 35 , 7226–7238 (2015).

Meshi, D., Morawetz, C. & Heekeren, H. R. Nucleus accumbens response to gains in reputation for the self relative to gains for others predicts social media use. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7 , 439 (2013).

Sherman, L. E., Greenfield, P. M., Hernandez, L. M. & Dapretto, M. Peer Influence via instagram: effects on brain and behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Child. Dev. 89 , 37–47 (2017).

Berns, G. S., Capra, C. M., Moore, S. & Noussair, C. Neural mechanisms of the influence of popularity on adolescent ratings of music. Neuroimage 49 , 2687–2696 (2010).

Will, G. J., Crone, E. A., van den Bos, W. & Guroglu, B. Acting on observed social exclusion: developmental perspectives on punishment of excluders and compensation of victims. Dev. Psychol. 49 , 2236–2244 (2013).

Knoll, L. J., Magis-Weinberg, L., Speekenbrink, M. & Blakemore, S. J. Social influence on risk perception during adolescence. Psychol. Sci. 26 , 583–592 (2015).

Rodgers, R., McLean, S. & Paxton, S. Longitudinal relationships among internalization of the media ideal, peer social comparison, and body dissatisfaction: Implications for the tripartite influence model. Dev. Psychol. 51 , 706–713 (2015).

Veldhuis, J., Konijn, E. A. & Seidell, J. C. Negotiated media effects. peer feedback modifies effects of media’s thin-body ideal on adolescent girls. Appetite 73 , 172–182 (2014).

Veldhuis, J., Konijn, E. A. & Seidell, J. C. Weight information labels on media models reduce body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. Health 50 , 600–606 (2012).

Zaki, J., Schirmer, J. & Mitchell, J. P. Social influence modulates the neural computation of value. Psychol. Sci. 22 , 894–900 (2011).

Campbell-Meiklejohn, D. K., Bach, D. R., Roepstorff, A., Dolan, R. J. & Frith, C. D. How the opinion of others affects our valuation of objects. Curr. Biol. 20 , 1165–1170 (2010).

van der Meulen, M. et al. Brain activation upon ideal-body media exposure and peer feedback in late adolescent girls. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 17 , 712–723 (2017).

Blakemore, S. J. The social brain in adolescence. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 , 267–277 (2008).

Van Hoorn, J., Van Dijk, E., Meuwese, R., Rieffe, C. & Crone, E. A. Peer influence on prosocial behavior in adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 26 , 90–100 (2016).

Van Hoorn, J., Van Dijk, E., Guroglu, B. & Crone, E. A. Neural correlates of prosocial peer influence on public goods game donations during adolescence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11 , 923–933 (2016).

Dahl, R. E. & Vanderschuren, L. J. The feeling of motivation in the developing brain. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 1 , 361–363 (2011).

Knowles, M. L. in The Oxford Handbook of Social Exclusion (ed. DeWall, C. N.) (Oxford University Press., Oxford/New York, 2013).

Nowland, R., Necka, E. A. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness and social internet use: pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13 , 70–87 (2017). 1745691617713052.

Konijn, E. A., Bijvank, M. N. & Bushman, B. J. I wish I were a warrior: the role of wishful identification in the effects of violent video games on aggression in adolescent boys. Dev. Psychol. 43 , 1038–1044 (2007).

Plaisier, X. S. & Konijn, E. A. Rejected by peers-attracted to antisocial media content: rejection-based anger impairs moral judgment among adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 49 , 1165–1173 (2013).

Casey, B. J. Beyond simple models of self-control to circuit-based accounts of adolescent behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66 , 295–319 (2015).

Will, G. J., Crone, E. A., van Lier, P. A. & Guroglu, B. Neural correlates of retaliatory and prosocial reactions to social exclusion: Associations with chronic peer rejection. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 19 , 288–297 (2016).

Zvyagintsev, M. et al. Violence-related content in video game may lead to functional connectivity changes in brain networks as revealed by fMRI-ICA in young men. Neuroscience 320 , 247–258 (2016).

Olsson, A. & Ochsner, K. N. The role of social cognition in emotion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 12 , 65–71 (2008).

Konijn, E. A., Walma van der Molen, J. H. & Van Nes, S. Emotions bias perceptions of realism in audiovisual media. Why we may take Fict. Real. Discourse Process. 46 , 309–340 (2009).

LeDoux, J. The emotional brain: past, present, future. Neurosci. Res. 68 , e1–e2 (2010).

Pfeifer, J. H. et al. Entering adolescence: resistance to peer influence, risky behavior, and neural changes in emotion reactivity. Neuron 69 , 1029–1036 (2011).

Rosen, M. L. et al. Salience network response to changes in emotional expressions of others is heightened during early adolescence: relevance for social functioning. Dev. Sci . https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12571 (2017).

Guroglu, B., van den Bos, W., van Dijk, E., Rombouts, S. A. & Crone, E. A. Dissociable brain networks involved in development of fairness considerations: understanding intentionality behind unfairness. Neuroimage 57 , 634–641 (2011).

Crone, E. A. & Dahl, R. E. Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13 , 636–650 (2012).

Constantinidis, C. & Klingberg, T. The neuroscience of working memory capacity and training. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17 , 438–449 (2016).

Weerdmeester, J., Cima, M., Granic, I., Hashemian, Y. & Gotsis, M. A feasibility study on the effectiveness of a full-body videogame intervention for decreasing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms. Games Health J. 5 , 258–269 (2016).

Schoneveld, E. A. et al. A neurofeedback video game (mindlight) to prevent anxiety in children: a randomized controlled trial. Comput. Human. Behav. 63 , 321–333 (2016).

van Duijvenvoorde, A. C., Peters, S., Braams, B. R. & Crone, E. A. What motivates adolescents? Neural responses to rewards and their influence on adolescents’ risk taking, learning, and cognitive control. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 70 , 135–147 (2016).

Konijn, E. A., Veldhuis, J. & Plaisier, X. S. YouTube as a research tool: three approaches. Cyber. Behav. Soc. Netw. 16 , 695–701 (2013).

Sundar, S. S. Handbook of the Psychology of Communication Technology (Wiley-Blackwell., Hoboken, NJ:, 2015).

Book Google Scholar

Huang, C. Time Spent on social network sites and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. Cyber. Behav. Soc. Netw. 20 , 346–354 (2017).

Baker, D. A. & Algorta, G. P. The relationship between online social networking and depression: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Cyber. Behav. Soc. Netw. 19 , 638–648 (2016).

Przybylski, A. K. & Weinstein, N. A large-scale test of the goldilocks hypothesis. Psychol. Sci. 28 , 204–215 (2017).

Wilmer, H. H. & Chein, J. M. Mobile technology habits: patterns of association among device usage, intertemporal preference, impulse control, and reward sensitivity. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 23 , 1607–1614 (2016).

Wilmer, H. H., Sherman, L. E. & Chein, J. M. Smartphones and Cognition: a review of research exploring the links between mobile technology habits and cognitive functioning. Front. Psychol. 8 , 605 (2017).

Reich, S. M., Subrahmanyam, K. & Espinoza, G. Friending, IMing, and hanging out face-to-face: overlap in adolescents’ online and offline social networks. Dev. Psychol. 48 , 356–368 (2012).

Lemola, S., Perkinson-Gloor, N., Brand, S., Dewald-Kaufmann, J. F. & Grob, A. Adolescents’ electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. J. Youth Adolesc. 44 , 405–418 (2015).

Meshi, D., Tamir, D. I. & Heekeren, H. R. The emerging neuroscience of social media. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19 , 771–782 (2015).

Chein, J., Albert, D., O’Brien, L., Uckert, K. & Steinberg, L. Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Dev. Sci. 14 , F1–F10 (2011).

Van Hoorn, J., Crone, E. A. & Van Leijenhorst, L. Hanging out with the right crowd: peer influence on risk-taking behavior in adolescence. J. Res Adolesc. 27 , 189–200 (2017).

Duell, N. et al. Interaction of reward seeking and self-regulation in the prediction of risk taking: a cross-national test of the dual systems model. Dev. Psychol. 52 , 1593–1605 (2016).

Sisk, C. L. & Foster, D. L. The neural basis of puberty and adolescence. Nat. Neurosci. 7 , 1040–1047 (2004).

Gladwin, T. E., Figner, B., Crone, E. A. & Wiers, R. W. Addiction, adolescence, and the integration of control and motivation. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 1 , 364–376 (2011).

van Oosten, J. M. & Vandenbosch, L. Sexy online self-presentation on social network sites and the willingness to engage in sexting: a comparison of gender and age. J. Adolesc. 54 , 42–50 (2017).

Mills, K. L. et al. Structural brain development between childhood and adulthood: convergence across four longitudinal samples. Neuroimage 141 , 273–281 (2016).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers for their detailed and insightful comments on the manuscript, and Lara Wierenga for providing helpful comments on previous versions of the manuscript. This work was supported by The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-VICI 453-14-001 E.A.C.) and by an innovative ideas grant of the European Research Council (ERC CoG PROSOCIAL 681632 to E.A.C.). Both authors were supported by the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS: September 2013–September 2014).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Leiden University, Wassenaarseweg 52, 2333AK, Leiden, Netherlands

Eveline A. Crone

Department of Communication Science, Media Psychology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1105, 1081 HV, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Elly A. Konijn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eveline A. Crone .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Crone, E.A., Konijn, E.A. Media use and brain development during adolescence. Nat Commun 9 , 588 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03126-x

Download citation

Received : 10 October 2017

Accepted : 22 January 2018

Published : 21 February 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03126-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

- Adrian Meier

- Sarah-Jayne Blakemore

Nature Reviews Psychology (2024)

Digitale Mediennutzung und psychische Gesundheit bei Adoleszenten – eine narrative Übersicht

- Kerstin Paschke

- Rainer Thomasius

Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (2024)

Social Media and Youth Mental Health

- Paul E. Weigle

- Reem M. A. Shafi

Current Psychiatry Reports (2024)

The associations between screen time and mental health in adolescents: a systematic review

- Renata Maria Silva Santos

- Camila Guimarães Mendes

- Marco Aurélio Romano-Silva

BMC Psychology (2023)

How social media affects teen mental health: a missing link

Nature (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Social and Cultural History

- Urban History

- Language Teaching and Learning

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- Language Evolution

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Browse content in Literature

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musicology and Music History

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Technology and Society

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Biochemistry

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Programming Languages

- Browse content in Computing

- Computer Games

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Maps and Map-making

- Environmental Science

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- Probability and Statistics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- History of Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Corporate Governance

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Browse content in Environment

- Climate Change

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Environmental Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- International Relations

- Latin American Politics

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Public Policy

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- US Politics

- Browse content in Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Sport and Leisure

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society

- Cite Icon Cite

In recent years, scholarship around media technologies has finally shed the assumption that they are separate from and powerfully determining of social life, to look at them rather as the product of and embedded in distinct social, cultural and political practices. To better examine them in this light, communication and media scholars have increasingly taken theoretical perspectives originating in science and technology studies (STS), while at the same time some STS scholars interested in information technologies have linked their research to media studies questions about their symbolic dimensions. In this volume, scholars from both fields come together to advance this view of media technologies as complex socio-material phenomena. The first four contributors address the relationship between materiality and mediation, highlighting the linkages between the symbolic and the artifactual by considering such topics as the lived realities of network infrastructure and the informational embodiment of networked knowledge. A second set of four contributors highlight media technologies as always in motion, held together through the minute, unobserved work of many. This includes examining how the meanings of media technologies came to be and the work involved to keep them alive. After each of the two sets of essays, comments by senior scholars respond to the essays and articulate overarching themes. The volume intends to initiate conversations about the state of current scholarship around media technologies, as well as identify directions for future research.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.6 Globalization of Media

Learning objectives.

- Identify three ways that technology has helped speed globalization.

- Explain how media outlets employ globalization to their advantage.

- Describe some advances that can be made in foreign markets.

The media industry is, in many ways, perfect for globalization, or the spread of global trade without regard for traditional political borders. As discussed above, the low marginal costs of media mean that reaching a wider market creates much larger profit margins for media companies. Because information is not a physical good, shipping costs are generally inconsequential. Finally, the global reach of media allows it to be relevant in many different countries.

However, some have argued that media is actually a partial cause of globalization, rather than just another globalized industry. Media is largely a cultural product , and the transfer of such a product is likely to have an influence on the recipient’s culture. Increasingly, technology has also been propelling globalization. Technology allows for quick communication, fast and coordinated transport, and efficient mass marketing, all of which have allowed globalization—especially globalized media—to take hold.

Globalized Culture, Globalized Markets

Much globalized media content comes from the West, particularly from the United States. Driven by advertising, U.S. culture and media have a strong consumerist bent (meaning that the ever-increasing consumption of goods is encouraged as an economic virtue), thereby possibly causing foreign cultures to increasingly develop consumerist ideals. Therefore, the globalization of media could not only provide content to a foreign country, but may also create demand for U.S. products. Some believe that this will “contribute to a one-way transmission of ideas and values that result in the displacement of indigenous cultures (Santos, 2001).”

Globalization as a world economic trend generally refers to the lowering of economic trade borders, but it has much to do with culture as well. Just as transfer of industry and technology often encourages outside influence through the influx of foreign money into the economy, the transfer of culture opens up these same markets. As globalization takes hold and a particular community becomes more like the United States economically, this community may also come to adopt and personalize U.S. cultural values. The outcome of this spread can be homogenization (the local culture becomes more like the culture of the United States) or heterogenization (aspects of U.S. culture come to exist alongside local culture, causing the culture to become more diverse), or even both, depending on the specific situation (Rantanen, 2005).

Making sense of this range of possibilities can be difficult, but it helps to realize that a mix of many different factors is involved. Because of cultural differences, globalization of media follows a model unlike that of the globalization of other products. On the most basic level, much of media is language and culture based and, as such, does not necessarily translate well to foreign countries. Thus, media globalization often occurs on a more structural level, following broader “ways of organizing and creating media (Mirza, 2009).” In this sense, a media company can have many different culturally specific brands and still maintain an economically globalized corporate structure.

Vertical Integration and Globalization

Because globalization has as much to do with the corporate structure of a media company as with the products that a media company produces, vertical integration in multinational media companies becomes a necessary aspect of studying globalized media. Many large media companies practice vertical integration: Newspaper chains take care of their own reporting, printing, and distribution; television companies control their own production and broadcasting; and even small film studios often have parent companies that handle international distribution.