An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

Looking through racism in the nurse–patient relationship from the lens of culturally congruent care: A scoping review

Mojtaba vaismoradi.

1 Faculty of Nursing and Health Sciences, Nord University, Bodø Norway

Cathrine Fredriksen Moe

Gøril ursin, kari ingstad, associated data.

Authors do not want to share the data.

This review aimed to identify the nature of racism in the nurse–patient relationship and summarize international research findings about it.

A scoping review of the international literature.

Data sources

The search process encompassed three main online databases of PubMed (including MEDLINE), Scopus and Embase, from 2009 until 2021.

Review methods

The scoping review was informed by the Levac et al.’s framework to map the research phenomenon and summarize current empirical research findings. Also, the review findings were reflected in the three‐dimensional puzzle model of culturally congruent care in the discussion section.

The search process led to retrieving 149 articles, of which 10 studies were entered into data analysis and reporting results. They had variations in the research methodology and the context of the nurse–patient relationship. The thematical analysis of the studies' findings led to the development of three categories as follows: bilateral ignition of racism, hidden and manifest consequences of racism and encountering strategies.

Racism threatens patients' and nurses' dignity in the healthcare system. There is a need to develop a framework of action based on the principles of culturally congruent care to eradicate racism from the nurse–patient relationship in the globalized context of healthcare.

Racism in the nurse–patient relationship has remained a relatively unexplored area of the nursing literature. It hinders efforts to meet patients' and families' needs and increases their dissatisfaction with nursing care. Also, racism from patients towards nurses causes emotional trauma and enhances job‐related stress among nurses. Further research should be conducted on this culturally variant phenomenon. Also, the participation of patients and nurses should be sought to prohibit racism in healthcare settings.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to the American Nurses Association, racism is defined as ‘assaults on the human spirit in the form of biases, prejudices and an ideology of superiority that persistently cause moral suffering and perpetuate injustices and inequities’ (American Nurses Association, 2021 ) (P.1). Neoliberalism across the globe has made that racism remains invisible in terms of restructuring social classes, producing race categories and racialization (Ahlberg et al., 2019 ). Racism as prejudice and discrimination based on individuals' race and skin colour is a common healthcare problem across the globe. Ever increasing demographics, globalization and cultural changes in the healthcare context have attracted the attention of policy makers and international authorities to this phenomenon (George et al., 2015 ).

1.1. Background

Racism is the main cause of the patient's harm. Those patients who experience racist discriminations often have poor healthcare outcomes and access to health care, and suffer from mental health issues (Stanley et al., 2019 ). Racism in its common form as implicit racial bias specially negative attitudes towards the patient of colour can be pervasively observed in the relationship between patients and healthcare providers leading to healthcare disparities (Hall et al., 2015 ; Sim et al., 2021 ). It can also hinder appropriate and adequate use of health care, following up screening programmes and preventive behaviours, adherence to the therapeutic regimen and trust in healthcare providers (Powell et al., 2019 ; Pugh et al., 2021 ; Rhee et al., 2019 ). Disparity due to racism leads to the development of new disabilities in patients or even can worsen the present one (Rogers et al., 2015 ).

Nurses are located at the forefront of patient advocacy and they are expected to address inequities in the provision of care to their clients. However, structural racism can be observed in nursing practice (Iheduru‐Anderson et al., 2021 ; Villarruel & Broome, 2020 ). The counter racism role of nurses across healthcare settings emphasizes the identification of discriminatory care, and the development of tolerance, respect and empathy models for other healthcare professionals (Willey et al., 2021 ).

Ethics is one part of the anti‐racism paradigm with solutions that prohibit racist attitudes and behaviours in health care (Ho, 2016 ). Racism violates ethical practice among healthcare professions specially among nurses who are committed to the provision of equitable care to patients as the main part of social solidarity (Hamed et al., 2020 ; Weitzel et al., 2020 ).

The international research mainly has addressed racism towards patients. The occurrence of racist behaviours from patients towards healthcare professionals should be also investigated to create an equitable environment that hinders racism from both sides. It has been stated that black, Asian and minority ethnic nurses receive a different treatment from patients as being racially stereotyped and are considered less powerful in comparison with white nurses (Brathwaite, 2018 ; Truitt & Snyder, 2019 ). Patients' prejudicial and discriminative behaviours in terms of rejecting suggested care, verbal abuse and even physical violence have been described by these nurses as very painful and disrespectful behaviours leading to moral distress and reduction in the quality of patient care (Chandrashekar & Jain, 2020 ; Keshet & Popper‐Giveon, 2018 ).

Racism in the healthcare system has a long history. The identification of the nature of racism and its manifestations helps develop appropriate strategies for its elimination from the healthcare system (Mateo & Williams, 2021 ). The development of actions to tackle racism and racial discriminations has been chosen as a high‐level event at the 76th session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in 2021 (World Health Organization, 2021 ). Nevertheless, our knowledge of the extent of racism in healthcare systems and how it can be detected and prevented has remained limited. A probable reason is that racism directly influences the identity and rationality of healthcare professionals, which hinders holding discussions on this phenomenon in public discourses (Hamed et al., 2020 ). Open discussions on the issue of racism within the nursing profession help identify the underlying causes of racism and eradicate it from the healthcare context (Iheduru‐Anderson et al., 2021 ).

Further research is needed to better define racial, ethnic and cultural factors contributing to racism in healthcare systems and develop strategies that minimize their impacts on patient care (Godlee, 2020 ; Paradies et al., 2014 ).

2. THE REVIEW

Previous reviews of the international literature have taken a general perspective towards racism in the multidisciplinary context of health care (Chen et al., 2021 ; Sim et al., 2021 ). None of them have investigated racism in the context of the nurse–patient relationship to articulate its characteristics. Therefore, this review of international literature was undertaken to identify the nature of racism in the context of the nurse–patient relationship and summarize international research findings about it.

2.2. Design

A scoping review was performed. It is a research method by which the breadth of evidence in a field is mapped and the nature of the research phenomenon is identified (Daudt et al., 2013 ). The findings of scoping reviews can inform planning for future research and policy making (Westphaln et al., 2021 ).

This scoping review was carried out based on the review framework suggested by Levac et al. ( 2010 ) consisting of the following steps: identification of the research question; literature search and retrieving relevant studies; selection of studies; charting; collating, summarizing data and reporting results; consultation (Levac et al., 2010 ). These review steps were described under subheadings suggested by the journal's author guidelines.

2.3. Search methods

The review question was identified as follows: ‘what is the nature of racism in the nurse–patient relationship?’ The review question was kept broad enough to identify all aspects of this phenomenon in various caring situations, but it focused on related incidents only within the relationship between nurses and patients. It was also formulated by PICO:

P (Population): patients and nurses; I (Interest): racism, and racist attitudes and behaviours in the nurse–patient relationship; Co (Context): all contexts in healthcare including short‐term, long‐term, acute healthcare settings, child, adult, physical and mental healthcare.

The authors designed the review protocol and agreed on its details (Supporting Information 1 ). They performed a pilot search on Google Scholar and some specialized databases to identify relevant search keywords and phrases. The search process initially was established using the development of keywords, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and thesauruses' entry term that were translated into databases. The Boolean method and truncations with the operators of AND/OR were used to create the search sentence, which was pilot‐tested to ensure of its adequacy for retrieving relevant studies and selection of the most relevant databases for conducting the search.

The search sentence included all variants of terms related to nurse, patient, racism (e.g. racial bias, racial prejudice, racial discrimination, covert racism, racial disparity) and relationship (e.g. communication and interaction) in the context of healthcare. After conducting a pilot search, three main online databases that covered the majority of the peer‐reviewed and scientific international literature on racism in the field of nursing consisting of PubMed (including MEDLINE), Scopus and Embase were chosen for conducting the search. A librarian was also consulted to ensure of the accuracy of the search process.

2.4. Search outcome

Retrieved studies should have met the following inclusion criteria to be included in the review: original and empirical studies (qualitative/quantitative/mixed methods); focused on the phenomenon of racism; the nurse–patient relationship; racism from patients towards nurses and from nurses towards patients; various healthcare contexts such as short‐term, long‐term, acute healthcare settings, child, adult, physical and mental healthcare; being published in English language in scientific peer‐reviewed journals.

The publication date was restricted as from 1 January 2009 until 31 October 2021 to comprehensively access relevant studies. Any article that did not provide empirical data (e.g. reviews, commentaries, letters, conference proceedings, books) and did not overlap the main domains of the review (i.e. nurse, patient, racism) was excluded. The search coverage was enhanced through conducting a manual search inside some reputed journals with the history of publishing relevant studies and cross‐referencing from selected studies' bibliographies and previous reviews. The EndNote software was used for data management.

2.5. Quality appraisal

Risk of Bias assessment and quality appraisal generally are not applicable to scoping reviews. Therefore, all relevant studies were included in the reporting of the review results.

2.6. Data abstraction

To prevent bias, the authors (MV, CFM, GU, KI) independently screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved studies. Also, they independently read the full texts of the studies to make decisions on their inclusion or exclusion based on the pre‐determined eligibility criteria. Discussions were held by the authors to reach agreements on the selection of articles and their inclusion in data analysis and reporting results.

An extraction table was used to chart data, facilitate data importing from the selected studies, and categorize their general characteristics based on the author's name, country, publication year, sample and setting and research design.

2.7. Synthesis

The analytic framework was developed by drawing tables to collate, summarize and compare the studies' findings in relation to the review phenomenon and present an overview of relevant literature's breadth (Levac et al., 2010 ). Also, the studies' findings were thematically analysed by comparing their similarities and differences to gain a more abstract and at a higher lever insight into racism in the nurse–patient relationship.

The consultation step is optional and aims at the provision of stakeholders' involvement by suggesting complementary references and giving insights beyond those found in the reviewed literature. The sensitivity of the research topic and the requirement to obtain ethical permissions for collecting data from nurses and patients hindered the authors to follow this step. Therefore, it was removed from the review process.

The review findings were reflected to the three‐dimensional puzzle model of culturally congruent care by Leininger and McFarland ( 2002 ) via the main aspects of the cultural competence puzzle at the healthcare provider's and patient's levels consisting of ‘cultural diversity’, ‘cultural awareness’, ‘cultural sensitivity’ and ‘cultural competence’ (Leininger & McFarland, 2002 ; Schim et al., 2007 ).

The reason for the selection of culture as the analytical framework in this review lies in its application as the point of reference to the concepts of race and ethnicity. Culture is a dynamic concept, broadly encompasses commonalities and diversities in people and communities, and pervasively influences all aspects of life and healthcare (Schim et al., 2007 ). This synergy can help heal racism in the healthcare system (Hassen et al., 2021 ).

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) was used to guide this review (Tricco et al., 2018 ).

3.1. Search results and selection of studies

In the search process, 149 studies were retrieved (Table 1 ). Duplicates and irrelevant studies were excluded during title screening and abstract reading via holding discussions between the authors. Therefore, 24 articles underwent full‐text reading and assessment, of which 10 studies were entered into data analysis and reporting results given the inclusion criteria (Figure 1 ).

Results of the different phases of the review

The process of search and inclusion of studies in the scoping review

3.2. Characteristics of selected studies

The general characteristics of the selected studies have been presented in Table 2 . They were published between 2009 and 2021 indicating the review coverage for more than one decade. Five studies were conducted in the United States (Benkert et al., 2009 ; Cottingham et al., 2018 ; Martin et al., 2016 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ; Wheeler et al., 2014 ), two in Norway (Debesay et al., 2014 , 2021 ), one each in the United Kingdom (Deacon, 2011 ), Australia (Lyles et al., 2011 ) and Canada (McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ).

List of final articles included in the research synthesis and reporting results

The studies mainly used the qualitative design (Cottingham et al., 2018 ; Deacon, 2011 ; Debesay et al., 2014 , 2021 ; Martin et al., 2016 ; McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ; Wheeler et al., 2014 ), but two studies used the quantitative design (Benkert et al., 2009 ; Lyles et al., 2011 ). They were conducted in hospitals and community healthcare settings and were categorised based on their focuses as follows: patients' trust in nurses in relation to their racial identities (Benkert et al., 2009 ), nurses' confrontation with the racist expression by patients (Deacon, 2011 ), patient‐reported racial discrimination and communication with nurses (Lyles et al., 2011 ), perspectives of internationally educated nurses and American educated nurses about interactions with patients (Wheeler et al., 2014 ); nurses' experiences of home care provision to ethnic minority patients (Debesay et al., 2014 ); satisfaction of various racial groups of parents with neonatal nursing care (Martin et al., 2016 ); experiences of nurses of colour about negotiating with patients (Cottingham et al., 2018 ); health disparities during the nurse–patient relationship (Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ); racializing mothers and breastfeeding (McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ); nurses' critical encounters with ethnic minority patients (Debesay et al., 2021 ).

3.3. Racism in the nurse–patient relationship

The thematic analysis of the studies' findings led to the development of three categories: bilateral ignition of racism, hidden and manifest consequences of racism and encountering strategies.

3.3.1. Bilateral ignition of racism

Pervasive racist perspectives and stereotypies among patients and nurses shaped their racist behaviours and negatively impacted the nurse–patient relationship.

Implicit bias among nurses towards racial and ethnic minorities was available in the form of having a general assumption about minorities, and was reflected through indirect negative racist expressions during the nurse–patient communication rather than direct impolite racist remarks (Debesay et al., 2021 ). From the macro‐perspective, power bias innated in the patient–nurse relationship. Considering patients in a weaker social position was the main cause of racist incidents (Debesay et al., 2021 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ).

Racism in institutional practice and policies also contributed to negative stereotypes. Ethnic minority patients who did not follow institutional guidelines were considered outsiders. They were labelled as clients who could not get integrated into social values, and were subject to racist remarks. Education in terms of hidden curricula and by learning from others when nurses worked in healthcare settings established racist stereotypes and attitudes towards patients (McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ).

From a micro‐perspective, bias and stereotypical attitudes leading to racist behaviours rooted in nurses' personal perspectives towards ethnic minorities who had limited language proficiencies and substance dependencies, and suffered from mental illness (Debesay et al., 2021 ; Lyles et al., 2011 ; McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ). Instead of assessing patients' cultural and ethnic backgrounds and investigating their cultural identities, nurses guessed on patients' cultural characteristics and needs based on their habits and last names to plan healthcare interventions (McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ). Failure to follow‐up nurses' health‐related advice, patients' socio‐economic factors and stereotypical attitudes developed by patients themselves towards their own physical and mental in‐capabilities enhanced racial distortions among nurses (McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ).

On the other hand, patients' racism towards nurses was revealed in the experiences of nurses. Patients committed racial aggression when nurses were unable to meet their needs, which in some cases were unreasonable and beyond the defined nurse–patient relationship. Also, nurses' communication with accent triggered racist behaviours in patients (Cottingham et al., 2018 ; Debesay et al., 2021 ; Wheeler et al., 2014 ).

Nurses did not consider their position higher than patients in the nurse–patient interaction rounds. Nevertheless, some patients placed nurses at the lowest hierarchy of humanistic relationships and labelled them as subordinates. Patients' perspectives of nurses' ethnicity and cultural backgrounds determined the levels of nurses' competencies to provide care and receive respect. Nursing care was rejected by some patients, because of their personal orientations towards nurses' culture and ethnicity (Cottingham et al., 2018 ; Wheeler et al., 2014 ).

3.3.2. Hidden and manifest consequences of racism

Negative consequences of racism in the nurse–patient relationship were reported by both patients and nurses. Working in an environment in which stereotypical and racist attitudes influenced the nurse–patient relationship triggered the feeling of insecurity and uncertainty. Fear of making mistakes and crossing ethnic and cultural boundaries of minorities and the possibility of conflicts between patients' and families' beliefs, and nursing interventions enhanced work‐related stress among nurses (Debesay et al., 2014 , 2021 ). Nurses faced uncertainties with regard to how withhold their own personal prejudices and at the same time provide nursing care according to professional commitments (Debesay et al., 2021 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ).

Apparently, health disparities occurred given tensions between nurses and patients rooted in racist perspectives. They hindered nurses' efforts to provide appropriate care to patients and improve the nurse–patient relationship. When patients were not given opportunities to assert their cultural identities, they were discouraged to follow nurses' interventions and health‐related advice leading to more healthcare issues (Debesay et al., 2021 ; McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ).

Patients mainly were dissatisfied with receiving support by nurses and complained about nurses' superior, cold and without sympathy communication style, inattention to their caring needs, not receiving suitable education, not spending enough time with patients and frequent nurses' turnover (Lyles et al., 2011 ; Martin et al., 2016 ; McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ).

A negative consequence of nurses' racist behaviours was the development of a negative perspective among patients towards the healthcare system. Racism was generalized to the whole healthcare system rather than taking it as a personal matter in the nurse–patient relationship (Benkert et al., 2009 ). Consequently, patients displayed disappointment or anger to all nurses and retaliated it, which damaged the sense of justice and pride even among those nurses who did their best to provide equitable care to patients (Debesay et al., 2021 ).

Those nurses who were subject to racist behaviours from patients experienced job‐related and emotional stress, which depleted their psychological resources and energy to deliver care. Assumption of incompetence due to racism led to emotional shift and encouraged nurses to retaliate. Therefore, instead of concentration on patient care, nurses focused on managing frustration and emotional trauma (Cottingham et al., 2018 ). Social isolation and disconnection, and leaving the nursing profession were some risky consequences of racist incidents (Cottingham et al., 2018 ; Wheeler et al., 2014 ).

3.3.3. Encountering strategies

Nurses and patients used strategies to avoid racism or at least minimize its impact on the nurse–patient relationship. Respect, trust and active participation in nursing care worked quite fine against stereotypical and racist behaviours. Compassionate care and respectful style of communication by nurses, friendliness, patience and taking care of patients' concerns and spending enough time for education were highlighted. These strategies could be all summarized into being patient‐centred (Lyles et al., 2011 ; Martin et al., 2016 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ).

Cultural mistrust as the outcome of racism could be avoided through the development of racial concordance in the nurse–patient relationship. The suggested strategy to achieve concordance was the provision of care by those nurses who had similar cultural and racial backgrounds to those of patients (Benkert et al., 2009 ; Lyles et al., 2011 ). Also, cultural understanding through the acknowledgment of patients' culture and learning about their values, ceremonies and traditions, integration of patients' values into nursing care and setting healthcare goals to preserve patients' cultural identity was required. Avoiding the creation of an unpleasant atmosphere in the nurse–patient relationship through not directly questioning patients' cultural characteristics, and balancing between care delivery and cultural rituals such as touching patients and undressing them helped prevent crossing cultural borders and creating the feeling of racism. Moreover, leading ethnic minority patients in healthcare journey and covering the gap between them and the requirements of the healthcare system were the main strategies for patient advocacy (Debesay et al., 2014 , 2021 ; McFadden & Erikson, 2020 ; Purtzer & Thomas, 2019 ).

When nurses faced racism from patients, they tried to avoid personalizing racist incidents and made jokes of them to control their anger and defend their own emotional well‐being. They considered such sorts of abuses one part of their daily work life that should be coped with (Cottingham et al., 2018 ; Deacon, 2011 ). Given the lack of policies in healthcare settings to manage racism, nurses coped with the situation and rationalized racist behaviours to reduce related emotional burdens. They tried to ignore racism and attributed it to patients' background diseases, age, previous negative life experiences and inability to take the responsibility of their own behaviours. As a confrontation strategy, some nurses reported the racist incident to authorities, used medications to calm patients, applied distraction techniques to patients, asked patients to refrain from being assaultive, and informed patients of their behaviours. In the worst case, some nurses decided to change their workplace (Cottingham et al., 2018 ; Deacon, 2011 ; Wheeler et al., 2014 ).

4. DISCUSSION

This scoping review of the international literature aimed to identify the nature of racism in the nurse–patient relationship and summarize international research findings about it. An overview of the breadth of the international literature on this phenomenon was presented consisting of three categories developed by the authors. Culture is intertwined with the phenomenon of racism and can critically influence the nurse–patient relationship (Crampton et al., 2003 ). Racism as an individual and systemic prejudice is imprinted in cultural artefacts and discourses (Salter et al., 2017 ). Racist perspectives, stereotypies and behaviours from patients and nurses can be attributed to cultural bias as the interpretation of situations and others' actions according to own set of personal perspectives, experiences and cultural standards.

Delivering unbiased and individualized care to culturally diverse patients is influenced by nurses' cultural competencies. Also, patients' personal attitudes and perspectives, and balancing the power between nurses and patients in healthcare situations are crucial to the development of an appropriate climate for patient care (Oxelmark et al., 2018 ; Vaismoradi et al., 2015 ). Accordingly, the findings of this review were discussed using the main aspects of the cultural competence puzzle consisting of cultural diversity, cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity and cultural competence as the elements of the three‐dimensional puzzle model of culturally congruent care at nurses' and patients' levels (Leininger & McFarland, 2002 ; Schim et al., 2007 ). The dimensions of this model have also the capacity to be the part of the patient's participation in the provision of culturally congruent care (Schim et al., 2007 ). Therefore, our discussion using this model covers racist behaviours from both patients and nurses. A summary of the review findings in connection to the culturally congruent care model has been presented in Figure 2 .

The review findings in connection to the culturally congruent care model

4.1. Cultural diversity

According to the review findings, racist behaviours in the nurse–patient relationship rooted in implicit and power biases demonstrating that the patient and the nurse had a low social position. Stereotypical attitudes were developed towards patients with limited language proficiencies, low socio‐economic conditions and different last names and cultural backgrounds.

Globalization is the cause of cultural diversities in health care. Similarities and differences between cultures in terms of race, ethnicity, nationality and ideology shape humanistic relationships in health care (Schim et al., 2007 ). The patient's and healthcare provider's cultural contexts are crucial in the development of the therapeutic relationship. The establishment of a constructive relationship between nurses and patients without the acknowledgment of their cultural diversities is impossible (Gopalkrishnan, 2018 ). Marginalization of ethnicities and minorities in the healthcare system should be avoided and instead their cultural diversities should be acknowledged and respected. All measures should be taken to avoid tensions when contacts between cultures occur. The assessment of cultural diversities is the cornerstone of planning for the provision of culturally congruent care through appropriate exposure to cultural differences and prevention of racism (Schim et al., 2007 ). Diversities in nurses' cultural backgrounds have been shown to be advantageous for the healthcare system in terms of improving the quality of patient care and healthcare economy (Gomez & Bernet, 2019 ).

4.2. Cultural awareness

In this review, education had an influence on the development of racism towards patients through hidden curricula and by learning at the workplace. Nurses felt uncertain about how to provide care that was congruent to patients' cultural backgrounds without having stress about crossing patients' cultural boundaries. Those nurses who faced racism from patients often were unable to manage the situation, were emotionally overloaded, and lost their concetration on the provision of care. Similarly, patients' racist behaviours towards nurses were attributed to a lack of understanding of nurses' cultural backgrounds.

Gaining knowledge about and recognition of other cultures help to identify the uniqueness of each culture and commonalities between the cultures. Cultural awareness aims at identifying similarities and differences between cultures in terms of religious rituals, routines, preferences and behaviours. It recognizes interpersonal comfort zones and customizes care to them, and suggest a method by which people can interact with others' cultures in the caring relationship leading to the delivery of culturally sensitive care (Schim et al., 2007 ).

Cultural awareness often happens in the process of informal nursing education because direct education may not be able to provide sufficient opportunities for nurses to become culturally aware (Hultsjö et al., 2019 ; Kaihlanen et al., 2019 ). Raising awareness about caring situations in which misinterpretations may occur help with the detection of underlying causes and finding a counteraction framework by which an equitable communication is made with patients and their satisfaction is preserved (Crawford et al., 2017 ; Tan & Li, 2016 ). Comparisons of cultures and discovery of common ethical values in the nursing profession help develop skills for the creation of dialogue between individuals' and facilitate integration to the global nursing context (Leung et al., 2020 ).

4.3. Cultural sensitivity

In this review, institutional practice and policies contributed to the development of negative stereotypes by which ethnic minority patients who did not follow institutional guidelines were subject to racist behaviours. Cultural sensitivity consists of individuals' attitudes towards others and themselves and understanding others' cultural characteristics. It motivates individuals to be cross‐cultural and acknowledges others' cultural heritages. Judging others' cultures based on own culture is against the principle of cultural sensitivity (Schim et al., 2007 ). Measures taken in healthcare systems to reduce bias and racism should encompass all types of inequalities among ethnic minorities (Sim et al., 2021 ). Improving cultural sensitivity enhances cultural intelligence and facilitates understanding the impact of culture on health and diseases. Therefore, the provision of intercultural healthcare based on understanding differences and similarities between cultures leads to the reduction of health inequalities and improvement of healthcare quality (Göl & Erkin, 2019 ; Yilmaz et al., 2017 ). Public and social media have important roles to tackle the problem of patients' racist behaviours towards nurses in care situations. They can debate healthcare policies, promote public health behaviours, educate patients and inform them of cultural norms in healthcare settings and engage them in the development of an environment that respects cultural diversities. Improving cultural sensitivity involves an increased focus on human rights. Individuals' equal worth and rights regardless of race, ethnicity, language and religion lay the foundation of human rights (United Nations, 2021 ).

4.4. Cultural competence

The findings of this review showed that patients could not assert their cultural identities and were dissatisfied with nurses' inappropriate communication style and lack of attention to their needs. Although there was no indication of training to nurses about culturally congruent care in our findings, the main focus of strategies to avoid racism by nurses was to acknowledge the patient culture, behave respectfully and provide compassionate care. This coping strategy supported nurses' personal well‐being and at the same time prevented the creation of negative stereotypes towards patients' cultural backgrounds. It is the demonstration of a series of behaviours and taking related actions indicating that healthcare professionals know how to acknowledge cultural diversities and are aware of and sensitive towards the patient's culture (Schim et al., 2007 ).

In the context of health care, it is to adapt care and comply skills to patients' needs. Being culturally competent facilitates culturally congruence care in the nurse–patient relationship. Cultural competence for ethnic minorities requires organizational support (Taylor, 2005 ) and it should include work at the system level (Sharifi et al., 2019 ). Cultural education and training have been emphasized as mitigating strategies that can reduce racism and bias, and enhance cope with cultural diversities. Cultural competence is an important strategy by which health inequities can be addressed (Horvat et al., 2014 ). It requires practising self‐reflexivity on routines that cause racism and bringing implicit bias to own conscious (Bradby et al., 2021 ; Medlock et al., 2017 ; Olukotun et al., 2018 ). Training about diversities and being exposed to cultural differences in practical placements can promote cultural competence and consequently interaction with culturally diverse patients (Levey, 2020 ; McLennon et al., 2019 ). Promoting cultural competence among healthcare providers prevents healthcare encounters and reduces shame and embarrassment among care receivers (Flynn et al., 2020 ).

4.5. Limitations and suggestions for future studies

This scoping review provided an overview of international knowledge about racism in the nurse–patient relationship in spite of retrieving a few empirical studies on this important phenomenon. More studies might have been published in languages other than English that could not be included in this review, and should be considered by future researchers. Racism in the nurse–patient relationship has remained a less explored area of nursing research specially regarding racism from patients towards nurses. Therefore, more studies about racism in the context of the nurse–patient relationship and in various healthcare contexts should be conducted to improve our knowledge of this culturally variant phenomenon and devise a general unified strategy for the eradication of racism from the nurse–patient relationship.

5. CONCLUSION

Racism threatens patients' and nurses' dignity in the healthcare system. It hinders efforts to meet patients' and families' needs and increases their dissatisfaction with nursing care leading to the loss of trust in nurses and reduction of quality of care. Also, racism from patients towards nurses causes emotional trauma and enhances job‐related stress among nurses leading to their turnover. Nurses often apply coping strategies to relieve the emotional pressure of racist incidents and protect their own emotional well‐being.

Racism in the globalized context of healthcare should be prevented and nurses' and patients' well‐being and dignity should be preserved. It needs the establishment of acts and legislations that prohibit racist behaviours and enforce their report to healthcare authorities to seek support and prosecute racist people. Also, there is a need to develop a framework of action based on the principles of culturally congruent care to eradicate racism from the nurse–patient relationship in the globalized context of healthcare.

The practical implications of the review findings based on the culturally congruent care model are as follows:

- Development of a practical guideline to help nurses and patients acknowledge cultural diversities and promote their awareness and sensitivity towards other cultures;

- Improvement of nurses' cultural competence through education and training about how to avoid racism during the provision of care to patients with different cultural backgrounds;

- Development of policies and practical strategies to ensure that patients are held responsible for racist behaviours that create a toxic environment for healthcare professionals;

- Comparing cultures and removing misperceptions about other cultures through communication and dialogue between nurses and patients;

- Rectification of institutional policies contributing to the creation of stereotypies about cultural minorities;

- Use of public and social media to inform patients of cultural norms in healthcare settings;

- Collaboration between associations supporting the human rights of nurses and patients for the development and implementation of zero‐tolerance and anti‐racism policies;

- Emphasis on the equal worth of people and human rights in healthcare settings;

- Cultural socialization of nurses through education and training about customizing care to patients' cultural backgrounds, demonstrating respect and providing compassionate care;

- Active screening and detection of stereotypes, implicit bias and racist attitudes among nurses through self‐reflexivity.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MV was involved in review design. MV, CFM, GU and KI were involved in data acquisition, analysis and interpretation for important intellectual content, drafting the manuscript and revising it for intellectual content and giving final approval of the version to be published in the journal.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15267 .

Supporting information

Vaismoradi, M. , Fredriksen Moe, C. , Ursin, G. & Ingstad, K. (2022). Looking through racism in the nurse–patient relationship from the lens of culturally congruent care: A scoping review . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 78 , 2665–2677. 10.1111/jan.15267 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

The authors have received no financial support the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

- Ahlberg, B. M. , Hamed, S. , Thapar‐Björkert, S. , & Bradby, H. (2019). Invisibility of racism in the global neoliberal era: Implications for researching racism in healthcare [review] . Frontiers in Sociology , 4 ( 61 ). 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00061 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Nurses Association . (2021). National Commission to address racism in nursing: Defining racism . Retrieved November 5, 2021, from https://www.nursingworld.org/~49f737/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/workforce/commission‐to‐address‐racism/final‐defining‐racism‐june‐2021.pdf

- Benkert, R. , Hollie, B. , Nordstrom, C. K. , Wickson, B. , & Bins‐Emerick, L. (2009). Trust, mistrust, racial identity and patient satisfaction in urban African American primary care patients of nurse practitioners . Journal of Nursing Scholarship , 41 ( 2 ), 211–219. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01273.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradby, H. , Hamed, S. , Thapar‐Björkert, S. , & Ahlberg, B. M. (2021). Designing an education intervention for understanding racism in healthcare in Sweden: Development and implementation of anti‐racist strategies through shared knowledge production and evaluation . Scandinavian Journal of Public Health , 14034948211040963. 10.1177/14034948211040963 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brathwaite, B. (2018). Black, Asian and minority ethnic female nurses: Colonialism, power and racism . The British Journal of Nursing , 27 ( 5 ), 254–258. 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.5.254 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chandrashekar, P. , & Jain, S. H. (2020). Addressing patient bias and discrimination against clinicians of diverse backgrounds . Academic Medicine , 95 ( 12S ), S33–S43. 10.1097/acm.0000000000003682 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen, J. , Khazanchi, R. , Bearman, G. , & Marcelin, J. R. (2021). Racial/ethnic inequities in healthcare‐associated infections under the shadow of structural racism: Narrative review and call to action . Current Infectious Disease Reports , 23 ( 10 ), 17. 10.1007/s11908-021-00758-x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cottingham, M. D. , Johnson, A. H. , & Erickson, R. J. (2018). “I can never be too comfortable”: Race, gender, and emotion at the hospital bedside . Qualitative Health Research , 28 ( 1 ), 145–158. 10.1177/1049732317737980 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crampton, P. , Dowell, A. , Parkin, C. , & Thompson, C. (2003). Combating effects of racism through a cultural immersion medical education program . Academic Medicine , 78 ( 6 ), 595–598. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2003/06000/Combating_Effects_of_Racism_Through_a_Cultural.8.aspx [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crawford, T. , Candlin, S. , & Roger, P. (2017). New perspectives on understanding cultural diversity in nurse–patient communication . Collegian , 24 ( 1 ), 63–69. 10.1016/j.colegn.2015.09.001 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Daudt, H. M. , van Mossel, C. , & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter‐professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework . BMC Medical Research Methodology , 13 , 48. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deacon, M. (2011). How should nurses deal with patients' personal racism? Learning from practice . Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing , 18 ( 6 ), 493–500. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01696.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Debesay, J. , Harsløf, I. , Rechel, B. , & Vike, H. (2014). Facing diversity under institutional constraints: Challenging situations for community nurses when providing care to ethnic minority patients . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 70 ( 9 ), 2107–2116. 10.1111/jan.12369 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Debesay, J. , Kartzow, A. H. , & Fougner, M. (2021). Healthcare professionals' encounters with ethnic minority patients: The critical incident approach . Nursing Inquiry , e12421. 10.1111/nin.12421 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flynn, P. M. , Betancourt, H. , Emerson, N. D. , Nunez, E. I. , & Nance, C. M. (2020). Health professional cultural competence reduces the psychological and behavioral impact of negative healthcare encounters . Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology , 26 ( 3 ), 271–279. 10.1037/cdp0000295 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- George, R. , Thornicroft, G. , & Dogra, N. (2015). Exploration of cultural competency training in UK healthcare settings: A critical interpretive review of the literature . Diversity & Equality in Health and Care , 12 . 10.21767/2049-5471.100037 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Godlee, F. (2020). Racism: The other pandemic . British Medical Journal , 369 , m2303. 10.1136/bmj.m2303 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gomez, L. E. , & Bernet, P. (2019). Diversity improves performance and outcomes . Journal of the National Medical Association , 111 ( 4 ), 383–392. 10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.006 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gopalkrishnan, N. (2018). Cultural diversity and mental health: Considerations for policy and practice . Frontiers in Public Health , 6 , 179. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00179 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Göl, İ. , & Erkin, Ö. (2019). Association between cultural intelligence and cultural sensitivity in nursing students: A cross‐sectional descriptive study . Collegian , 26 ( 4 ), 485–491. 10.1016/j.colegn.2018.12.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hall, W. J. , Chapman, M. V. , Lee, K. M. , Merino, Y. M. , Thomas, T. W. , Payne, B. K. , Eng, E. , Day, S. H. , & Coyne‐Beasley, T. (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review . American Journal of Public Health , 105 ( 12 ), e60–e76. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hamed, S. , Thapar‐Björkert, S. , Bradby, H. , & Ahlberg, B. M. (2020). Racism in European health care: Structural violence and beyond . Qualitative Health Research , 30 ( 11 ), 1662–1673. 10.1177/1049732320931430 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hassen, N. , Lofters, A. , Michael, S. , Mall, A. , Pinto, A. D. , & Rackal, J. (2021). Implementing anti‐racism interventions in healthcare settings: A scoping review . International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 18 ( 6 ). 10.3390/ijerph18062993 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ho, A. (2016). Racism and bioethics: Are we part of the problem? The American Journal of Bioethics , 16 ( 4 ), 23–25. 10.1080/15265161.2016.1145293 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Horvat, L. , Horey, D. , Romios, P. , & Kis‐Rigo, J. (2014). Cultural competence education for health professionals . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , ( 5 ), CD009405. 10.1002/14651858.CD009405.pub2 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hultsjö, S. , Bachrach‐Lindström, M. , Safipour, J. , & Hadziabdic, E. (2019). "Cultural awareness requires more than theoretical education"—Nursing students' experiences . Nurse Education in Practice , 39 , 73–79. 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.07.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Iheduru‐Anderson, K. , Shingles, R. R. , & Akanegbu, C. (2021). Discourse of race and racism in nursing: An integrative review of literature . Public Health Nursing , 38 ( 1 ), 115–130. 10.1111/phn.12828 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaihlanen, A. M. , Hietapakka, L. , & Heponiemi, T. (2019). Increasing cultural awareness: Qualitative study of nurses' perceptions about cultural competence training . BMC Nursing , 18 , 38. 10.1186/s12912-019-0363-x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keshet, Y. , & Popper‐Giveon, A. (2018). Race‐based experiences of ethnic minority health professionals: Arab physicians and nurses in Israeli public healthcare organizations . Ethnicity & Health , 23 ( 4 ), 442–459. 10.1080/13557858.2017.1280131 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leininger, M. M. , & McFarland, M. F. (2002). Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research and practice (3rd edition) . Journal of Transcultural Nursing , 13 ( 3 ), 261. 10.1177/104365960201300320 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leung, D. Y. L. , Chan, E. A. , Wong, A. K. C. , Reisenhofer, S. , Stenberg, M. , Pui Sze, C. , Lai, K. H. , Cruz, E. , & Carlson, E. (2020). Advancing pedagogy of undergraduate nursing students' cultural awareness through internationalization webinars: A qualitative study . Nurse Education Today , 93 , 104514. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104514 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levac, D. , Colquhoun, H. , & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology . Implementation Science , 5 , 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levey, J. A. (2020). Teaching online graduate nursing students cultural diversity from an ethnic and nonethnic perspective . Journal of Transcultural Nursing , 31 ( 2 ), 202–208. 10.1177/1043659619868760 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyles, C. R. , Karter, A. J. , Young, B. A. , Spigner, C. , Grembowski, D. , Schillinger, D. , & Adler, N. (2011). Provider factors and patient‐reported healthcare discrimination in the diabetes study of California (DISTANCE) . Patient Education and Counseling , 85 ( 3 ), e216–e224. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.04.031 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martin, A. E. , D'Agostino, J. A. , Passarella, M. , & Lorch, S. A. (2016). Racial differences in parental satisfaction with neonatal intensive care unit nursing care . Journal of Perinatology , 36 ( 11 ), 1001–1007. 10.1038/jp.2016.142 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mateo, C. M. , & Williams, D. R. (2021). Racism: A fundamental driver of racial disparities in health‐care quality . Nature Reviews Disease Primers , 7 ( 1 ), 20. 10.1038/s41572-021-00258-1 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McFadden, A. , & Erikson, S. L. (2020). How nurses come to race: Racialization in public health breastfeeding promotion . Advances in Nursing Science , 43 ( 1 ), E11–e24. 10.1097/ans.0000000000000288 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McLennon, S. M. , Rogers, T. L. , & Davis, A. (2019). Predictors of hospital Nurses' cultural competence: The value of diversity training . Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing , 50 ( 10 ), 469–474. 10.3928/00220124-20190917-09 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Medlock, M. , Weissman, A. , Wong, S. S. , Carlo, A. , Zeng, M. , Borba, C. , Curry, M. , & Shtasel, D. (2017). Racism as a unique social determinant of mental health: Development of a didactic curriculum for psychiatry residents . MedEdPORTAL , 13 . 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10618 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Olukotun, O. , Mkandawire‐Vahlmu, L. , Kreuziger, S. B. , Dressel, A. , Wesp, L. , Sima, C. , Scheer, V. , Weitzel, J. , Washington, R. , Hess, A. , Kako, P. , & Stevens, P. (2018). Preparing culturally safe student nurses: An analysis of undergraduate cultural diversity course reflections . Journal of Professional Nursing , 34 ( 4 ), 245–252. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2017.11.011 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oxelmark, L. , Ulin, K. , Chaboyer, W. , Bucknall, T. , & Ringdal, M. (2018). Registered Nurses' experiences of patient participation in hospital care: Supporting and hindering factors patient participation in care . Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences , 32 ( 2 ), 612–621. 10.1111/scs.12486 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paradies, Y. , Truong, M. , & Priest, N. (2014). A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 29 ( 2 ), 364–387. 10.1007/s11606-013-2583-1 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Powell, W. , Richmond, J. , Mohottige, D. , Yen, I. , Joslyn, A. , & Corbie‐Smith, G. (2019). Medical mistrust, racism, and delays in preventive health screening among African‐American men . Behavioral Medicine , 45 ( 2 ), 102–117. 10.1080/08964289.2019.1585327 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pugh, M., Jr. , Perrin, P. B. , Rybarczyk, B. , & Tan, J. (2021). Racism, mental health, healthcare provider trust, and medication adherence among black patients in safety‐net primary care . Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings , 28 ( 1 ), 181–190. 10.1007/s10880-020-09702-y [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Purtzer, M. A. , & Thomas, J. J. (2019). Intentionality in reducing health disparities: Caring as connection . Public Health Nursing , 36 ( 3 ), 276–283. 10.1111/phn.12594 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rhee, T. G. , Marottoli, R. A. , Van Ness, P. H. , & Levy, B. R. (2019). Impact of perceived racism on healthcare access among older minority adults . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 56 ( 4 ), 580–585. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.010 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rogers, S. E. , Thrasher, A. D. , Miao, Y. , Boscardin, W. J. , & Smith, A. K. (2015). Discrimination in healthcare settings is associated with disability in older adults: Health and retirement study, 2008–2012 . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 30 ( 10 ), 1413–1420. 10.1007/s11606-015-3233-6 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Salter, P. S. , Adams, G. , & Perez, M. J. (2017). Racism in the structure of everyday worlds: A cultural‐psychological perspective . Current Directions in Psychological Science , 27 ( 3 ), 150–155. 10.1177/0963721417724239 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schim, S. M. , Doorenbos, A. , Benkert, R. , & Miller, J. (2007). Culturally congruent care: Putting the puzzle together . Journal of Transcultural Nursing , 18 ( 2 ), 103–110. 10.1177/1043659606298613 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sharifi, N. , Adib‐Hajbaghery, M. , & Najafi, M. (2019). Cultural competence in nursing: A concept analysis . International Journal of Nursing Studies , 99 , 103386. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103386 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sim, W. , Lim, W. H. , Ng, C. H. , Chin, Y. H. , Yaow, C. Y. L. , Cheong, C. W. Z. , Khoo, C. M. , Samarasekera, D. D. , Devi, M. K. , & Chong, C. S. (2021). The perspectives of health professionals and patients on racism in healthcare: A qualitative systematic review . PLoS One , 16 ( 8 ), e0255936. 10.1371/journal.pone.0255936 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stanley, J. , Harris, R. , Cormack, D. , Waa, A. , & Edwards, R. (2019). The impact of racism on the future health of adults: Protocol for a prospective cohort study . BMC Public Health , 19 ( 1 ), 346. 10.1186/s12889-019-6664-x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tan, N. , & Li, S. (2016). Multiculturalism in healthcare: A review of current research into diversity found in the healthcare professional population and the patient population . International Journal of Medical Students , 4 ( 3 ), 112–119. 10.5195/ijms.2016.163 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Taylor, R. (2005). Addressing barriers to cultural competence . Journal for Nurses in Staff Development , 21 ( 4 ), 135‐142; quiz 143–144. 10.1097/00124645-200507000-00001 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tricco, A. C. , Lillie, E. , Zarin, W. , O'Brien, K. K. , Colquhoun, H. , Levac, D. , Moher, D. , Peters, M. D. J. , Horsley, T. , Weeks, L. , Hempel, S. , Akl, E. A. , Chang, C. , McGowan, J. , Stewart, L. , Hartling, L. , Aldcroft, A. , Wilson, M. G. , Garritty, C. , … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): Checklist and explanation . Annals of Internal Medicine , 169 ( 7 ), 467–473. 10.7326/m18-0850 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Truitt, A. R. , & Snyder, C. R. (2019). Racialized experiences of black nursing professionals and certified nursing assistants in long‐term care settings . Journal of Transcultural Nursing , 31 ( 3 ), 312–318. 10.1177/1043659619863100 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- United Nations (UN) . (2021). Peace, dignity and equality on a healthy planet . Retrieved November 26, 2021, from . https://www.un.org/en/global‐issues/human‐rights

- Vaismoradi, M. , Jordan, S. , & Kangasniemi, M. (2015). Patient participation in patient safety and nursing input—A systematic review . Journal of Clinical Nursing , 24 ( 5–6 ), 627–639. 10.1111/jocn.12664 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Villarruel, A. M. , & Broome, M. E. (2020). Beyond the naming: Institutional racism in nursing . Nursing Outlook , 68 ( 4 ), 375–376. 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.06.009 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weitzel, J. , Luebke, J. , Wesp, L. , Graf, M. D. C. , Ruiz, A. , Dressel, A. , & Mkandawire‐Valhmu, L. (2020). The role of nurses as allies against racism and discrimination: An analysis of key resistance movements of our time . Advances in Nursing Science , 43 ( 2 ), 102–113. 10.1097/ans.0000000000000290 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Westphaln, K. K. , Regoeczi, W. , Masotya, M. , Vazquez‐Westphaln, B. , Lounsbury, K. , McDavid, L. , Lee, H. , Johnson, J. , & Ronis, S. D. (2021). From Arksey and O'Malley and beyond: Customizations to enhance a team‐based, mixed approach to scoping review methodology . Methods X , 8 , 101375. 10.1016/j.mex.2021.101375 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wheeler, R. M. , Foster, J. W. , & Hepburn, K. W. (2014). The experience of discrimination by US and internationally educated nurses in hospital practice in the USA: A qualitative study . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 70 ( 2 ), 350–359. 10.1111/jan.12197 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Willey, S. , Desmyth, K. , & Truong, M. (2021). Racism, healthcare access and health equity for people seeking asylum . Nursing Inquiry , 29 , e12440. 10.1111/nin.12440 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization . (2021). WHO at the high‐level session of the 76th UN General Assembly (UNGA) . Retrieved November 5, 2021, from . https://www.who.int/news‐room/events/detail/2021/09/14/default‐calendar/who‐at‐the‐high‐level‐session‐of‐the‐76th‐un‐general‐assembly‐(unga)

- Yilmaz, M. , Toksoy, S. , Direk, Z. D. , Bezirgan, S. , & Boylu, M. (2017). Cultural sensitivity among clinical nurses: A descriptive study . Journal of Nursing Scholarship , 49 ( 2 ), 153–161. 10.1111/jnu.12276 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Honor Society

- [ Member Login ]

- Search for: Search Button

National Commission to Address Racism in Nursing Releases Foundational Report

June 2, 2022

The National Commission to Address Racism in Nursing has issued a new foundational report that explores the impact of systemic racism on the nursing workforce and delivery of nursing care. The report closely examines the effects that racism has on nursing education, policy, research, and practice.

“These reports explore how racism shows up in our profession. We invite you to read each document with an open mind and heart, and with the empathy and thirst for knowledge that define excellence in nursing. How might this information influence you and your nursing practice? How might it be fuel for improving our profession, and the health, educational, and social systems in which we engage and work?”

OADN was invited to be an inaugural member of the Commission in January of 2021, and OADN members were asked to provide comments on the report’s initial draft in early 2022. OADN CEO Donna Meyer, MSN, RN, ANEF, FAADN, FAAN served as a commissioner for the report’s education workgroup, with Teaching and Learning in Nursing Editor-in-Chief Anna Valdez, Ph.D., RN, PHN, CEN, CNE, CFRN, FAEN, FAADN and OADN Board of Directors Member Jayson T. Valerio, DNP, RN serving as subject matter experts for the report’s education section.

Download The Full Report

The history of racism in nursing.

This report centers the experiences of nurses of color in U.S. history and how structural and systemic racism have hindered access to educational and professional opportunities as well as institutional power. The report also reviews some of the ways in which these nurses resisted, challenged, and achieved within the structures of racism.

Additionally, the report explains and critiques the central place that whiteness has occupied in histories of American nursing. More contextualized historical studies about the experiences of nurses of color and studies that explore the complicity of the nursing profession in perpetuating racism are needed.

Read this section

Contemporary Context

What does racism look like in the 21st Century? This essay examines power, privilege, and prejudice in nursing today. By looking at our history, we can understand the current inequities and discriminatory practices that hinder the progress of nurses of color.

Racism in nursing education has been prevalent since its beginning with roots in white supremacy. Today both students and faculty of color experience negative environments and limited opportunities.

Creating equitable and inclusive learning environments will lead to increased access and opportunities for students, faculty, and staff. This will eliminate many barriers and gaps that prevent success.

Due to the systemic nature of policies, they are a significant means by which racism within nursing is perpetuated.

A commitment must be made to eliminate racism in existing policy. Additionally, new policies that address past harms and advance the nursing profession are needed.

The impact of racism in the nurse’s work environment has significant implications on staff retention and physical and psychological safety. By viewing racism as a preventable harm, it is possible to see how it can be confronted through changes to structures, beliefs, policies, and practices.

This report also explores the ethical obligations to develop a culture where all staff and patients are treated fairly. Included are suggestions for how health care organizations can create an inclusive and civil culture.

Nursing research is overwhelmingly conducted by white nurse researchers. Research done with minoritized communities leaves impressions of exploitation and mistrust. Minority nurse researchers are key to address health disparities and inequities.

Current structures for research funding from healthcare institutions and governmental agencies are inequitable and must change. Bold funding decisions can level the field and lead to positive disruption.

PRESENTED BY:

- Julie Zerwic , PhD, FAHA, FAAN, Kelting Dean and Professor, College of Nursing, University of Iowa

- Kathy Dolter , PhD, RN Dean of Nursing, Kirkwood Community College

- Sarah Phipps , MSHSA, BSN, RN, Associate Executive Director, Idaho Board of Nursing

- Open access

- Published: 10 June 2022

Racism and antiracism in nursing education: confronting the problem of whiteness

- Sharissa Hantke 1 ,

- Verna St. Denis 1 &

- Holly Graham 1

BMC Nursing volume 21 , Article number: 146 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

6 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Systemic racism in Canadian healthcare may be observed through racially inequitable outcomes, particularly for Indigenous people. Nursing approaches intending to respond to racism often focus on culture without critically addressing the roots of racist inequity directly. In contrast, the critical race theory approach used in this study identifies whiteness as the underlying problem; a system of racial hierarchy that accords value to white people while it devalues everyone else.

This qualitative study seeks to add depth to the understanding of how whiteness gets performed by nursing faculty and poses antiracism education as a necessary tool in addressing the systemic racism within Canadian healthcare. The methodology of poststructural discourse analysis is used to explore the research question: how do white nursing faculty draw on common discourses to produce themselves following introductory antiracism education?

Analysis of data reveals common patterns of innocent and superior white identity constructions including benevolence, neutrality, Knowing, and exceptionalism. While these patterns are established in other academic fields, the approaches and results of this study are not yet common in nursing literature.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the need for antiracism education at personal and policy levels beginning in nursing programs.

Peer Review reports

Racist health outcomes

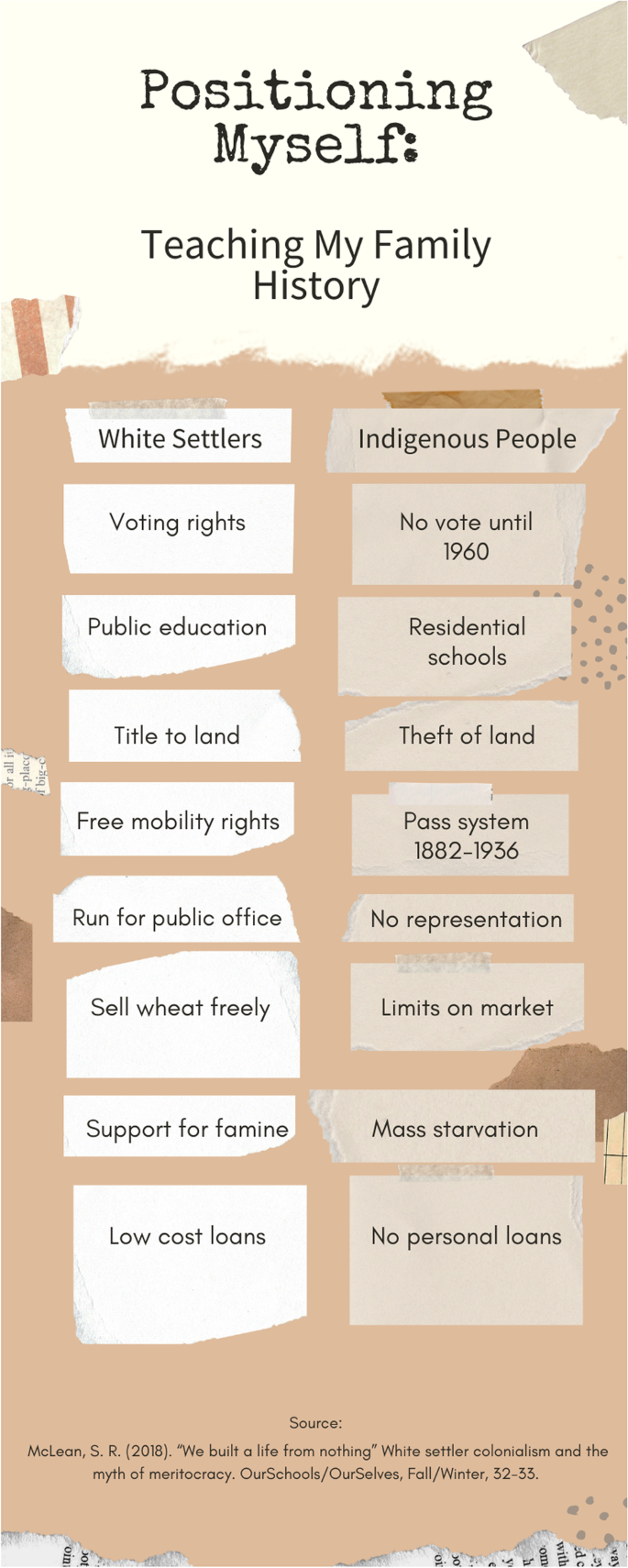

The publicly funded Canadian healthcare system could be considered a point of national pride distinguishing us from the United States of America (USA) [ 1 ]. However, the outcomes of this system demonstrate that equal care and equal health are not made accessible for everyone. Indigenous people are frequently provided with substandard care, [ 2 , 3 ], and are subjected to disproportionate rates of poverty and illnesses including tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and diabetes [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. The horrific death of Joyce Echaquan at the hands of Quebec nurses after they taunted her with anti-Indigenous stereotypes [ 3 ] has caused more nurses, managers, and nurse educators to recognize the widespread harms of racism within Canadian healthcare and the dire need for action. Despite national narratives of Canada as an accepting, diverse, multicultural country, our history demonstrates that from the early policies shaping the health of Canadians the healthcare system was created for, and continues to be for, the benefit of the white settler population and the simultaneous exclusion of Indigenous people, citizens of Colour, and immigrants of Colour [ 7 ]. A lack of public understanding of policies enacting racial exclusion enables white settler Canadians, including healthcare professionals, to participate in racist systems without seeing or understanding the racialized harms.

The racist violence of our system and its resulting harm, such as the numerous instances made evident in the In Plain Sight report [ 3 ], ought to be at the forefront of efforts to improve Canadian healthcare.

Why not focus on culture?

Nursing approaches attempting to respond to systemic racism in healthcare frequently focus on cultural learning, as in increasing one’s knowledge about ethnic minority cultures [ 8 , 9 ]. Healthcare could learn from what antiracist education scholar St. Denis [ 10 ] describes: “We started out a few decades ago in Aboriginal education believing that we could address the effects of racialization and colonization by affirming and validating the cultural traditions and heritage of Aboriginal peoples. There is increasing evidence that those efforts have limitations” (p. 178). Focusing on cultural education misdiagnoses the underlying problem, puts the onus for change onto the oppressed group, and absolves white people of responsibility for making changes [ 10 ]. Culturalist approaches within nursing reify discourses which other oppressed groups while either ignoring or inadequately focusing on race and racism [ 8 ]. Instead of focusing on learning about the Other, nursing needs anti-oppressive approaches which are critical of othering and approaches that seek to change students and society [ 11 ].

Sometimes cultural safety and cultural competence get conflated, as Curtis et al. [ 9 ] identify. While cultural competence more narrowly focuses on cross-cultural behaviours and acquiring knowledge about ethnic minority groups, cultural safety critically considers biases, stereotypes, power, and colonialism [ 9 ]. Bell [ 8 ] notes that “cultural safety and cultural humility pedagogies employ a more critical lens than previous iterations of culturally based approaches” (p. 3) such as cultural competence, transculturalism, and cultural sensitivity. Furthermore, Bell [ 8 ] argues that “cultural safety will not be possible to attain without explicit deconstruction of the white supremacist ideology that people in colonial and post-colonial states are socialized into so that people fundamentally understand and become accountable for their (our) oppressive and/or privileged behaviour” (p. 4).

To create an outcome of cultural safety for racially oppressed groups, we must address the racism underlying the harm. To address racism in the healthcare system, all healthcare workers, educators, and decision makers need the tools of antiracism education grounded in critical race theory and critical whiteness studies. We must work on understanding the attitudes and priorities of the healthcare system and how they enact harm so that instead of focusing on cultural learning as a solution to racist harm, we work to understand and address the underlying problem at the core of racialized health outcomes: whiteness.

Relevant nursing literature

Since Vaughan’s 1997 article [ 12 ] asks if there really is racism in nursing and answers with a definitive “yes”, very little nursing literature has explored racism in nursing, and less still has named whiteness as underlying racism. Prior to 2020, searching for nursing literature that critically addresses racism revealed few results. Exceptions include: Blanchet Garneau, Browne, and Varcoe [ 13 ] highlighting the need for antiracist pedagogy in nursing; Hilario, Browne, and McFadden [ 14 ] identify democratic racism in nursing—discourses that attempt to justify contradictions between Canadian values of tolerance and equity, and Canadian racism; Tang and Browne’s [ 15 ] study identify various ways that racist stereotypes impact Indigenous patients’ access to care; Scammell and Olumide [ 16 ] describe white nurses as “unwittingly” perpetuating racism; Van Herk, Smith, and Andrew [ 17 ] urgently suggest that intersectionality and critical pedagogy become part of nursing education and practice; and Walker’s dissertation [ 18 ] demonstrates the need for cultural safety training and delineating important differences between cultural competence and cultural safety.

How whiteness underpins racism

This study uses the term “whiteness” to point to the system of racial hierarchy that positions white racial identity at the top and thereby affords disproportionate power and privilege to people racialized as white at the expense of everyone not racialized as white [ 19 ]. The theoretical bases underpinning this research are Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Critical Whiteness Studies (CWS). Three particularly relevant shared tenets of these fields include (1) understanding racism as systemic and often invisible to white people [ 20 ]; (2) race and whiteness as socially constructed to serve white interests [ 21 , 22 , 23 ] as opposed to primarily biologically or genetically [ 24 ]; and (3) the necessity of directing the critical gaze away from those subjected to racism and toward those who are unduly privileged by racial dominance [ 20 , 25 ]. As such, this study understands racial categories as having been constructed in the eighteenth century to serve an exploitative agenda which still causes widespread health inequity [ 26 ]. Although the concept of races as biologically distinct categories is outdated and disproven, underlying biases based on these debunked ideas still get reified in science and health fields [ 8 , 27 ]. This study understands race to be immensely impactful because of its social construction and maintenance and therefore aims to keep a critical focus on how race and racism get produced.

Instead of recognizing racism as a primarily interpersonal phenomenon, this study urges readers to consider how systemic racism is constructed and maintained systemically through discourses. Of particular interest are discourses which function to position whiteness as superior and as innocent. Through identifying and analyzing the discursive resources [ 28 ] utilized by white settler nursing faculty, this study aims to highlight the need for personal antiracism learning for individual white nursing faculty, the need for inclusion of antiracism curriculum into nursing programs, and the need for an antiracism lens at the policy level of nursing programs.

Although this study examines Canadian healthcare and Canadian data, the findings may have relevance more broadly. The Canadian context has been shaped by colonization, and the resulting racial dynamics may have parallels wherever colonialism and European imperialism oppress Indigenous peoples with a “huge legacy of suffering and destruction” (p. 20) [ 29 ].

Researcher context and reflexivity

This research and the antiracism education preceding it were undertaken as part of Sharissa Hantke’s master’s thesis. Sharissa is a white settler cisgender woman and worked under the supervision of Indigenous scholar and antiracism education expert Dr. Verna St. Denis and Indigenous scholar, psychologist, and nursing faculty Dr. Holly Graham. Since Sharissa is a white settler critically studying how white nursing faculty perform whiteness, guidance and mentorship from Indigenous scholars was critical in mitigating the risks of perpetuating settler colonialism.

Study design

This study seeks to add depth to understanding how whiteness gets performed by nursing faculty and thereby to examine how the performance of whiteness functions to uphold racism within nursing education. The research question is therefore: how do white nursing faculty draw on common discourses to produce themselves following introductory antiracism education?

Following approval from the behavioural research ethics board, nursing faculty were recruited to a focus group interview to discuss their experience of a workshop introducing antiracism education. Such education is new to Saskatchewan nursing faculty, and the workshop sessions were made possible through funding from the Indigenous Research Chair of Canadian Institute of Health Research through the Dr. Graham’s wahkohtowin project. Although the entire workshop was 6 full days long, the training was offered in three two-day chunks, with four month breaks between. Due to time constraints, the 1.5 h focus group session was held after the first two-day workshop where participants had learned about race as a social construct, intersectionality, racism as systemic, history of racism in Canadian health care, debunking meritocracy, and exploring resistance to antiracist education. Recruitment occurred at the end of day two of the workshop session by inviting white nursing faculty to participate in the research study. Of the 24 registrants who met eligibility requirements for being white nursing faculty, three volunteered to participate in the focus group, and informed consent was obtained. These three white nursing faculty teach in different nursing programs, and their voluntary participation demonstrates their keenness to continue learning antiracism. These participants were provided with open ended reflection questions in advance which asked them about difficult/uncomfortable parts of the education, their anticipation of how the education may impact their teaching, and their next steps on their antiracism journey. The focus group interview was semi structured to allow for participants to respond to each other and build off each other’s responses in the group context. One strength of a focus group approach was that the conversation allowed participants to continue to learn from and to build relationships with each other. The focus group was facilitated by the primary author. These participants were at different points in their antiracism learning and this is reflected in the data which came from all three participants.

The focus group dialogue was transcribed and then discourses were identified consistent with critical race theory (CRT) literature [ 30 ]. Concept mapping was used to track discourses which connect to CRT. Data was interpreted from the poststructural discourse analysis perspective of language as not simply a means of neutrally describing reality—rather of discourses as doing particular things [ 28 ].

Wetherell [ 28 ] says that identities are “constituted as they are formulated in discourse” (p. 12). Focus group participants used their words to produce their own white nursing faculty identities in patterns consistent with literature in the field of Critical Whiteness Studies [ 21 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Critically examining how white people construct identity is imperative because of the connections to racialized health disparities.

Inequality is not first a fact of nature and then a topic of talk. Discourse is intimately involved in the construction and maintenance of inequality. Inequality is constructed and maintained when enough discursive resources can be mobilized to make colonial practices of land acquisition, for instance, legal, natural, normal, and ‘the way we do things.’ (p. 13) [ 28 ]

Therefore it is imperative to examine the sorts of discourses white nursing faculty employ so that we can learn how to identify deeply held beliefs which find their way into nursing practices and into policy, thereby producing racist outcomes (see Structural Determinism framework [ 35 ]). In seeking out these discourses, this research aims to gain more understanding of how white settlers contribute to racist harm and how to work toward both personal and policy level change.

As such, this study examines common, well-intentioned, and seemingly benign discursive maneuvers present in the focus group interview not for the purpose of critiquing the individuals who made the statements in the time they generously volunteered to the study, but rather to examine what these common statements and sentiments do in regards to race.