- Chapter Seven: Presenting Your Results

This chapter serves as the culmination of the previous chapters, in that it focuses on how to present the results of one's study, regardless of the choice made among the three methods. Writing in academics has a form and style that you will want to apply not only to report your own research, but also to enhance your skills at reading original research published in academic journals. Beyond the basic academic style of report writing, there are specific, often unwritten assumptions about how quantitative, qualitative, and critical/rhetorical studies should be organized and the information they should contain. This chapter discusses how to present your results in writing, how to write accessibly, how to visualize data, and how to present your results in person.

- Chapter One: Introduction

- Chapter Two: Understanding the distinctions among research methods

- Chapter Three: Ethical research, writing, and creative work

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 2 - Doing Your Study)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 3 - Making Sense of Your Study)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Data (Part 2)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 2)

Written Presentation of Results

Once you've gone through the process of doing communication research – using a quantitative, qualitative, or critical/rhetorical methodological approach – the final step is to communicate it.

The major style manuals (the APA Manual, the MLA Handbook, and Turabian) are very helpful in documenting the structure of writing a study, and are highly recommended for consultation. But, no matter what style manual you may use, there are some common elements to the structure of an academic communication research paper.

Title Page :

This is simple: Your Paper's Title, Your Name, Your Institutional Affiliation (e.g., University), and the Date, each on separate lines, centered on the page. Try to make your title both descriptive (i.e., it gives the reader an idea what the study is about) and interesting (i.e., it is catchy enough to get one's attention).

For example, the title, "The uncritical idealization of a compensated psychopath character in a popular book series," would not be an inaccurate title for a published study, but it is rather vague and exceedingly boring. That study's author fortunately chose the title, "A boyfriend to die for: Edward Cullen as compensated psychopath in Stephanie Meyer's Twilight ," which is more precisely descriptive, and much more interesting (Merskin, 2011). The use of the colon in academic titles can help authors accomplish both objectives: a catchy but relevant phrase, followed by a more clear explanation of the article's topic.

In some instances, you might be asked to write an abstract, which is a summary of your paper that can range in length from 75 to 250 words. If it is a published paper, it is useful to include key search terms in this brief description of the paper (the title may already have a few of these terms as well). Although this may be the last thing your write, make it one of the best things you write, because this may be the first thing your audience reads about the paper (and may be the only thing read if it is written badly). Summarize the problem/research question, your methodological approach, your results and conclusions, and the significance of the paper in the abstract.

Quantitative and qualitative studies will most typically use the rest of the section titles noted below. Critical/rhetorical studies will include many of the same steps, but will often have different headings. For example, a critical/rhetorical paper will have an introduction, definition of terms, and literature review, followed by an analysis (often divided into sections by areas of investigation) and ending with a conclusion/implications section. Because critical/rhetorical research is much more descriptive, the subheadings in such a paper are often times not generic subheads like "literature review," but instead descriptive subheadings that apply to the topic at hand, as seen in the schematic below. Because many journals expect the article to follow typical research paper headings of introduction, literature review, methods, results, and discussion, we discuss these sections briefly next.

Introduction:

As you read social scientific journals (see chapter 1 for examples), you will find that they tend to get into the research question quickly and succinctly. Journal articles from the humanities tradition tend to be more descriptive in the introduction. But, in either case, it is good to begin with some kind of brief anecdote that gets the reader engaged in your work and lets the reader understand why this is an interesting topic. From that point, state your research question, define the problem (see Chapter One) with an overview of what we do and don't know, and finally state what you will do, or what you want to find out. The introduction thus builds the case for your topic, and is the beginning of building your argument, as we noted in chapter 1.

By the end of the Introduction, the reader should know what your topic is, why it is a significant communication topic, and why it is necessary that you investigate it (e.g., it could be there is gap in literature, you will conduct valuable exploratory research, or you will provide a new model for solving some professional or social problem).

Literature Review:

The literature review summarizes and organizes the relevant books, articles, and other research in this area. It sets up both quantitative and qualitative studies, showing the need for the study. For critical/rhetorical research, the literature review often incorporates the description of the historical context and heuristic vocabulary, with key terms defined in this section of the paper. For more detail on writing a literature review, see Appendix 1.

The methods of your paper are the processes that govern your research, where the researcher explains what s/he did to solve the problem. As you have seen throughout this book, in communication studies, there are a number of different types of research methods. For example, in quantitative research, one might conduct surveys, experiments, or content analysis. In qualitative research, one might instead use interviews and observations. Critical/rhetorical studies methods are more about the interpretation of texts or the study of popular culture as communication. In creative communication research, the method may be an interpretive performance studies or filmmaking. Other methods used sometimes alone, or in combination with other methods, include legal research, historical research, and political economy research.

In quantitative and qualitative research papers, the methods will be most likely described according to the APA manual standards. At the very least, the methods will include a description of participants, data collection, and data analysis, with specific details on each of these elements. For example, in an experiment, the researcher will describe the number of participants, the materials used, the design of the experiment, the procedure of the experiment, and what statistics will be used to address the hypotheses/research questions.

Critical/rhetorical researchers rarely have a specific section called "methods," as opposed to quantitative and qualitative researchers, but rather demonstrate the method they use for analysis throughout the writing of their piece.

Helping your reader understand the methods you used for your study is important not only for your own study's credibility, but also for possible replication of your study by other researchers. A good guideline to keep in mind is transparency . You want to be as clear as possible in describing the decisions you made in designing your study, gathering and analyzing your data so that the reader can retrace your steps and understand how you came to the conclusions you formed. A research study can be very good, but if it is not clearly described so that others can see how the results were determined or obtained, then the quality of the study and its potential contributions are lost.

After you completed your study, your findings will be listed in the results section. Particularly in a quantitative study, the results section is for revisiting your hypotheses and reporting whether or not your results supported them, and the statistical significance of the results. Whether your study supported or contradicted your hypotheses, it's always helpful to fully report what your results were. The researcher usually organizes the results of his/her results section by research question or hypothesis, stating the results for each one, using statistics to show how the research question or hypothesis was answered in the study.

The qualitative results section also may be organized by research question, but usually is organized by themes which emerged from the data collected. The researcher provides rich details from her/his observations and interviews, with detailed quotations provided to illustrate the themes identified. Sometimes the results section is combined with the discussion section.

Critical/rhetorical researchers would include their analysis often with different subheadings in what would be considered a "results" section, yet not labeled specifically this way.

Discussion:

In the discussion section, the researcher gives an appraisal of the results. Here is where the researcher considers the results, particularly in light of the literature review, and explains what the findings mean. If the results confirmed or corresponded with the findings of other literature, then that should be stated. If the results didn't support the findings of previous studies, then the researcher should develop an explanation of why the study turned out this way. Sometimes, this section is called a "conclusion" by researchers.

References:

In this section, all of the literature cited in the text should have full references in alphabetical order. Appendices: Appendix material includes items like questionnaires used in the study, photographs, documents, etc. An alphabetical letter is assigned for each piece (e.g. Appendix A, Appendix B), with a second line of title describing what the appendix contains (e.g. Participant Informed Consent, or New York Times Speech Coverage). They should be organized consistently with the order in which they are referenced in the text of the paper. The page numbers for appendices are consecutive with the paper and reference list.

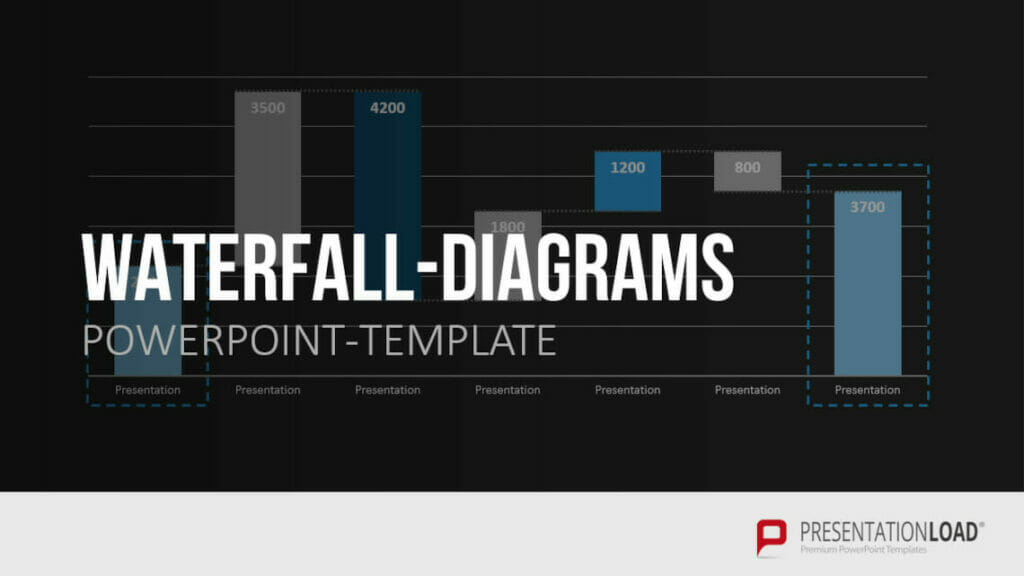

Tables/Figures:

Tables and figures are referenced in the text, but included at the end of the study and numbered consecutively. (Check with your professor; some like to have tables and figures inserted within the paper's main text.) Tables generally are data in a table format, whereas figures are diagrams (such as a pie chart) and drawings (such as a flow chart).

Accessible Writing

As you may have noticed, academic writing does have a language (e.g., words like heuristic vocabulary and hypotheses) and style (e.g., literature reviews) all its own. It is important to engage in that language and style, and understand how to use it to communicate effectively in an academic context . Yet, it is also important to remember that your analyses and findings should also be written to be accessible. Writers should avoid excessive jargon, or—even worse—deploying jargon to mask an incomplete understanding of a topic.

The scourge of excessive jargon in academic writing was the target of a famous hoax in 1996. A New York University physics professor submitted an article, " Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity ," to a special issue of the academic journal Social Text devoted to science and postmodernism. The article was designed to point out how dense academic jargon can sometimes mask sloppy thinking. As the professor, Alan Sokal, had expected, the article was published. One sample sentence from the article reads:

It has thus become increasingly apparent that physical "reality", no less than social "reality", is at bottom a social and linguistic construct; that scientific "knowledge", far from being objective, reflects and encodes the dominant ideologies and power relations of the culture that produced it; that the truth claims of science are inherently theory-laden and self-referential; and consequently, that the discourse of the scientific community, for all its undeniable value, cannot assert a privileged epistemological status with respect to counter-hegemonic narratives emanating from dissident or marginalized communities. (Sokal, 1996. pp. 217-218)

According to the journal's editor, about six reviewers had read the article but didn't suspect that it was phony. A public debate ensued after Sokal revealed his hoax. Sokal said he worried that jargon and intellectual fads cause academics to lose contact with the real world and "undermine the prospect for progressive social critique" ( Scott, 1996 ). The APA Manual recommends to avoid using technical vocabulary where it is not needed or relevant or if the technical language is overused, thus becoming jargon. In short, the APA argues that "scientific jargon...grates on the reader, encumbers the communication of information, and wastes space" (American Psychological Association, 2010, p. 68).

Data Visualization

Images and words have long existed on the printed page of manuscripts, yet, until recently, relatively few researchers possessed the resources to effectively combine images combined with words (Tufte, 1990, 1983). Communication scholars are only now becoming aware of this dimension in research as computer technologies have made it possible for many people to produce and publish multimedia presentations.

Although visuals may seem to be anathema to the primacy of the written word in research, they are a legitimate way, and at times the best way, to present ideas. Visual scholar Lester Faigley et al. (2004) explains how data visualizations have become part of our daily lives:

Visualizations can shed light on research as well. London-based David McCandless specializes in visualizing interesting research questions, or in his words "the questions I wanted answering" (2009, p. 7). His images include a graph of the peak times of the year for breakups (based on Facebook status updates), a radiation dosage chart , and some experiments with the Google Ngram Viewer , which charts the appearance of keywords in millions of books over hundreds of years.

The public domain image below creatively maps U.S. Census data of the outflow of people from California to other states between 1995 and 2000.

Visualizing one's research is possible in multiple ways. A simple technology, for example, is to enter data into a spreadsheet such as Excel, and select Charts or SmartArt to generate graphics. A number of free web tools can also transform raw data into useful charts and graphs. Many Eyes , an open source data visualization tool (sponsored by IBM Research), says its goal "is to 'democratize' visualization and to enable a new social kind of data analysis" (IBM, 2011). Another tool, Soundslides , enables users to import images and audio to create a photographic slideshow, while the program handles all of the background code. Other tools, often open source and free, can help visual academic research into interactive maps; interactive, image-based timelines; interactive charts; and simple 2-D and 3-D animations. Adobe Creative Suite (which includes popular software like Photoshop) is available on most computers at universities, but open source alternatives exist as well. Gimp is comparable to Photoshop, and it is free and relatively easy to use.

One online performance studies journal, Liminalities , is an excellent example of how "research" can be more than just printed words. In each issue, traditional academic essays and book reviews are often supported photographs, while other parts of an issue can include video, audio, and multimedia contributions. The journal, founded in 2005, treats performance itself as a methodology, and accepts contribution in html, mp3, Quicktime, and Flash formats.

For communication researchers, there is also a vast array of visual digital archives available online. Many of these archives are located at colleges and universities around the world, where digital librarians are spearheading a massive effort to make information—print, audio, visual, and graphic—available to the public as part of a global information commons. For example, the University of Iowa has a considerable digital archive including historical photos documenting American railroads and a database of images related to geoscience. The University of Northern Iowa has a growing Special Collections Unit that includes digital images of every UNI Yearbook between 1905 and 1923 and audio files of UNI jazz band performances. Researchers at he University of Michigan developed OAIster , a rich database that has joined thousands of digital archives in one searchable interface. Indeed, virtually every academic library is now digitizing all types of media, not just texts, and making them available for public viewing and, when possible, for use in presenting research. In addition to academic collections, the Library of Congress and the National Archives offer an ever-expanding range of downloadable media; commercial, user-generated databases such as Flickr, Buzznet, YouTube and Google Video offer a rich resource of images that are often free of copyright constraints (see Chapter 3 about Creative Commons licenses) and nonprofit endeavors, such as the Internet Archive , contain a formidable collection of moving images, still photographs, audio files (including concert recordings), and open source software.

Presenting your Work in Person

As Communication students, it's expected that you are not only able to communicate your research project in written form but also in person.

Before you do any oral presentation, it's good to have a brief "pitch" ready for anyone who asks you about your research. The pitch is routine in Hollywood: a screenwriter has just a few minutes to present an idea to a producer. Although your pitch will be more sophisticated than, say, " Snakes on a Plane " (which unfortunately was made into a movie), you should in just a few lines be able to explain the gist of your research to anyone who asks. Developing this concise description, you will have some practice in distilling what might be a complicated topic into one others can quickly grasp.

Oral presentation

In most oral presentations of research, whether at the end of a semester, or at a research symposium or conference, you will likely have just 10 to 20 minutes. This is probably not enough time to read the entire paper aloud, which is not what you should do anyway if you want people to really listen (although, unfortunately some make this mistake). Instead, the point of the presentation should be to present your research in an interesting manner so the listeners will want to read the whole thing. In the presentation, spend the least amount of time on the literature review (a very brief summary will suffice) and the most on your own original contribution. In fact, you may tell your audience that you are only presenting on one portion of the paper, and that you would be happy to talk more about your research and findings in the question and answer session that typically follows. Consider your presentation the beginning of a dialogue between you and the audience. Your tone shouldn't be "I have found everything important there is to find, and I will cram as much as I can into this presentation," but instead "I found some things you will find interesting, but I realize there is more to find."

Turabian (2007) has a helpful chapter on presenting research. Most important, she emphasizes, is to remember that your audience members are listeners, not readers. Thus, recall the lessons on speech making in your college oral communication class. Give an introduction, tell them what the problem is, and map out what you will present to them. Organize your findings into a few points, and don't get bogged down in minutiae. (The minutiae are for readers to find if they wish, not for listeners to struggle through.) PowerPoint slides are acceptable, but don't read them. Instead, create an outline of a few main points, and practice your presentation.

Turabian suggests an introduction of not more than three minutes, which should include these elements:

- The research topic you will address (not more than a minute).

- Your research question (30 seconds or less)

- An answer to "so what?" – explaining the relevance of your research (30 seconds)

- Your claim, or argument (30 seconds or less)

- The map of your presentation structure (30 seconds or less)

As Turabian (2007) suggests, "Rehearse your introduction, not only to get it right, but to be able to look your audience in the eye as you give it. You can look down at notes later" (p. 125).

Poster presentation

In some symposiums and conferences, you may be asked to present at a "poster" session. Instead of presenting on a panel of 4-5 people to an audience, a poster presenter is with others in a large hall or room, and talks one-on-one with visitors who look at the visual poster display of the research. As in an oral presentation, a poster highlights just the main point of the paper. Then, if visitors have questions, the author can informally discuss her/his findings.

To attract attention, poster presentations need to be nicely designed, or in the words of an advertising professor who schedules poster sessions at conferences, "be big, bold, and brief" ( Broyles , 2011). Large type (at least 18 pt.), graphics, tables, and photos are recommended.

A poster presentation session at a conference, by David Eppstein (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 ( www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0 )], via Wikimedia Commons]

The Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) has a template for making an effective poster presentation . Many universities, copy shops, and Internet services also have large-scale printers, to print full-color research poster designs that can be rolled up and transported in a tube.

Judging Others' Research

After taking this course, you should have a basic knowledge of research methods. There will still be some things that may mystify you as a reader of other's research. For example, you may not be able to interpret the coefficients for statistical significance, or make sense of a complex structural equation. Some specialized vocabulary may still be difficult.

But, you should understand how to critically review research. For example, imagine you have been asked to do a blind (i.e., the author's identity is concealed) "peer review" of communication research for acceptance to a conference, or publication in an academic journal. For most conferences and journals , submissions are made online, where editors can manage the flow and assign reviews to papers. The evaluations reviewers make are based on the same things that we have covered in this book. For example, the conference for the AEJMC ask reviewers to consider (on a five-point scale, from Excellent to Poor) a number of familiar research dimensions, including the paper's clarity of purpose, literature review, clarity of research method, appropriateness of research method, evidence presented clearly, evidence supportive of conclusions, general writing and organization, and the significance of the contribution to the field.

Beyond academia, it is likely you will more frequently apply the lessons of research methods as a critical consumer of news, politics, and everyday life. Just because some expert cites a number or presents a conclusion doesn't mean it's automatically true. John Allen Paulos, in his book A Mathematician reads the newspaper , suggests some basic questions we can ask. "If statistics were presented, how were they obtained? How confident can we be of them? Were they derived from a random sample or from a collection of anecdotes? Does the correlation suggest a causal relationship, or is it merely a coincidence?" (1997, p. 201).

Through the study of research methods, we have begun to build a critical vocabulary and understanding to ask good questions when others present "knowledge." For example, if Candidate X won a straw poll in Iowa, does that mean she'll get her party's nomination? If Candidate Y wins an open primary in New Hampshire, does that mean he'll be the next president? If Candidate Z sheds a tear, does it matter what the context is, or whether that candidate is a man or a woman? What we learn in research methods about validity, reliability, sampling, variables, research participants, epistemology, grounded theory, and rhetoric, we can consider whether the "knowledge" that is presented in the news is a verifiable fact, a sound argument, or just conjecture.

American Psychological Association (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Broyles, S. (2011). "About poster sessions." AEJMC. http://www.aejmc.org/home/2013/01/about-poster-sessions/ .

Faigley, L., George, D., Palchik, A., Selfe, C. (2004). Picturing texts . New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

IBM (2011). Overview of Many Eyes. http://www.research.ibm.com/social/projects_manyeyes.shtml .

McCandless, D. (2009). The visual miscellaneum . New York: Collins Design.

Merskin, D. (2011). A boyfriend to die for: Edward Cullen as compensated psychopath in Stephanie Meyer's Twilight. Journal of Communication Inquiry 35: 157-178. doi:10.1177/0196859911402992

Paulos, J. A. (1997). A mathematician reads the newspaper . New York: Anchor.

Scott, J. (1996, May 18). Postmodern gravity deconstructed, slyly. New York Times , http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/11/15/specials/sokal-text.html .

Sokal, A. (1996). Transgressing the boundaries: towards a transformative hermeneutics of quantum gravity. Social Text 46/47, 217-252.

Tufte, E. R. (1990). Envisioning information . Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Tufte, E. R. (1983). The visual display of quantitative information . Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Turabian, Kate L. (2007). A manual for writers of research papers, theses, and dissertations: Chicago style guide for students and researchers (7th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Table of Contents

Research Report

Definition:

Research Report is a written document that presents the results of a research project or study, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions, in a clear and objective manner.

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the findings of the research to the intended audience, which could be other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public.

Components of Research Report

Components of Research Report are as follows:

Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for the research report and provides a brief overview of the research question or problem being investigated. It should include a clear statement of the purpose of the study and its significance or relevance to the field of research. It may also provide background information or a literature review to help contextualize the research.

Literature Review

The literature review provides a critical analysis and synthesis of the existing research and scholarship relevant to the research question or problem. It should identify the gaps, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the literature and show how the current study addresses these issues. The literature review also establishes the theoretical framework or conceptual model that guides the research.

Methodology

The methodology section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used to collect and analyze data. It should include information on the sample or participants, data collection instruments, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques. The methodology should be clear and detailed enough to allow other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the study in a clear and objective manner. It should provide a detailed description of the data and statistics used to answer the research question or test the hypothesis. Tables, graphs, and figures may be included to help visualize the data and illustrate the key findings.

The discussion section interprets the results of the study and explains their significance or relevance to the research question or problem. It should also compare the current findings with those of previous studies and identify the implications for future research or practice. The discussion should be based on the results presented in the previous section and should avoid speculation or unfounded conclusions.

The conclusion summarizes the key findings of the study and restates the main argument or thesis presented in the introduction. It should also provide a brief overview of the contributions of the study to the field of research and the implications for practice or policy.

The references section lists all the sources cited in the research report, following a specific citation style, such as APA or MLA.

The appendices section includes any additional material, such as data tables, figures, or instruments used in the study, that could not be included in the main text due to space limitations.

Types of Research Report

Types of Research Report are as follows:

Thesis is a type of research report. A thesis is a long-form research document that presents the findings and conclusions of an original research study conducted by a student as part of a graduate or postgraduate program. It is typically written by a student pursuing a higher degree, such as a Master’s or Doctoral degree, although it can also be written by researchers or scholars in other fields.

Research Paper

Research paper is a type of research report. A research paper is a document that presents the results of a research study or investigation. Research papers can be written in a variety of fields, including science, social science, humanities, and business. They typically follow a standard format that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion sections.

Technical Report

A technical report is a detailed report that provides information about a specific technical or scientific problem or project. Technical reports are often used in engineering, science, and other technical fields to document research and development work.

Progress Report

A progress report provides an update on the progress of a research project or program over a specific period of time. Progress reports are typically used to communicate the status of a project to stakeholders, funders, or project managers.

Feasibility Report

A feasibility report assesses the feasibility of a proposed project or plan, providing an analysis of the potential risks, benefits, and costs associated with the project. Feasibility reports are often used in business, engineering, and other fields to determine the viability of a project before it is undertaken.

Field Report

A field report documents observations and findings from fieldwork, which is research conducted in the natural environment or setting. Field reports are often used in anthropology, ecology, and other social and natural sciences.

Experimental Report

An experimental report documents the results of a scientific experiment, including the hypothesis, methods, results, and conclusions. Experimental reports are often used in biology, chemistry, and other sciences to communicate the results of laboratory experiments.

Case Study Report

A case study report provides an in-depth analysis of a specific case or situation, often used in psychology, social work, and other fields to document and understand complex cases or phenomena.

Literature Review Report

A literature review report synthesizes and summarizes existing research on a specific topic, providing an overview of the current state of knowledge on the subject. Literature review reports are often used in social sciences, education, and other fields to identify gaps in the literature and guide future research.

Research Report Example

Following is a Research Report Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Academic Performance among High School Students

This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students. The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The findings indicate that there is a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students. The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers, as they highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities.

Introduction:

Social media has become an integral part of the lives of high school students. With the widespread use of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat, students can connect with friends, share photos and videos, and engage in discussions on a range of topics. While social media offers many benefits, concerns have been raised about its impact on academic performance. Many studies have found a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance among high school students (Kirschner & Karpinski, 2010; Paul, Baker, & Cochran, 2012).

Given the growing importance of social media in the lives of high school students, it is important to investigate its impact on academic performance. This study aims to address this gap by examining the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students.

Methodology:

The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The questionnaire was developed based on previous studies and was designed to measure the frequency and duration of social media use, as well as academic performance.

The participants were selected using a convenience sampling technique, and the survey questionnaire was distributed in the classroom during regular school hours. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

The findings indicate that the majority of high school students use social media platforms on a daily basis, with Facebook being the most popular platform. The results also show a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students.

Discussion:

The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. The negative correlation between social media use and academic performance suggests that strategies should be put in place to help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. For example, educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this study provides evidence of the negative impact of social media on academic performance among high school students. The findings highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. Further research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which social media use affects academic performance and to develop effective strategies for addressing this issue.

Limitations:

One limitation of this study is the use of convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future studies should use random sampling techniques to increase the representativeness of the sample. Another limitation is the use of self-reported measures, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Future studies could use objective measures of social media use and academic performance, such as tracking software and school records.

Implications:

The findings of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. Educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. For example, teachers could use social media platforms to share relevant educational resources and facilitate online discussions. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. They could also engage in open communication with their children to understand their social media use and its impact on their academic performance. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students. For example, schools could implement social media policies that restrict access during class time and encourage responsible use.

References:

- Kirschner, P. A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2010). Facebook® and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1237-1245.

- Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Journal of the Research Center for Educational Technology, 8(1), 1-19.

- Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(10), 652-657.

- Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., & Cheever, N. A. (2013). Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 948-958.

Note*: Above mention, Example is just a sample for the students’ guide. Do not directly copy and paste as your College or University assignment. Kindly do some research and Write your own.

Applications of Research Report

Research reports have many applications, including:

- Communicating research findings: The primary application of a research report is to communicate the results of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public. The report serves as a way to share new knowledge, insights, and discoveries with others in the field.

- Informing policy and practice : Research reports can inform policy and practice by providing evidence-based recommendations for decision-makers. For example, a research report on the effectiveness of a new drug could inform regulatory agencies in their decision-making process.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research in a particular area. Other researchers may use the findings and methodology of a report to develop new research questions or to build on existing research.

- Evaluating programs and interventions : Research reports can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and interventions in achieving their intended outcomes. For example, a research report on a new educational program could provide evidence of its impact on student performance.

- Demonstrating impact : Research reports can be used to demonstrate the impact of research funding or to evaluate the success of research projects. By presenting the findings and outcomes of a study, research reports can show the value of research to funders and stakeholders.

- Enhancing professional development : Research reports can be used to enhance professional development by providing a source of information and learning for researchers and practitioners in a particular field. For example, a research report on a new teaching methodology could provide insights and ideas for educators to incorporate into their own practice.

How to write Research Report

Here are some steps you can follow to write a research report:

- Identify the research question: The first step in writing a research report is to identify your research question. This will help you focus your research and organize your findings.

- Conduct research : Once you have identified your research question, you will need to conduct research to gather relevant data and information. This can involve conducting experiments, reviewing literature, or analyzing data.

- Organize your findings: Once you have gathered all of your data, you will need to organize your findings in a way that is clear and understandable. This can involve creating tables, graphs, or charts to illustrate your results.

- Write the report: Once you have organized your findings, you can begin writing the report. Start with an introduction that provides background information and explains the purpose of your research. Next, provide a detailed description of your research methods and findings. Finally, summarize your results and draw conclusions based on your findings.

- Proofread and edit: After you have written your report, be sure to proofread and edit it carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, and make sure that your report is well-organized and easy to read.

- Include a reference list: Be sure to include a list of references that you used in your research. This will give credit to your sources and allow readers to further explore the topic if they choose.

- Format your report: Finally, format your report according to the guidelines provided by your instructor or organization. This may include formatting requirements for headings, margins, fonts, and spacing.

Purpose of Research Report

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the results of a research study to a specific audience, such as peers in the same field, stakeholders, or the general public. The report provides a detailed description of the research methods, findings, and conclusions.

Some common purposes of a research report include:

- Sharing knowledge: A research report allows researchers to share their findings and knowledge with others in their field. This helps to advance the field and improve the understanding of a particular topic.

- Identifying trends: A research report can identify trends and patterns in data, which can help guide future research and inform decision-making.

- Addressing problems: A research report can provide insights into problems or issues and suggest solutions or recommendations for addressing them.

- Evaluating programs or interventions : A research report can evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions, which can inform decision-making about whether to continue, modify, or discontinue them.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies.

When to Write Research Report

A research report should be written after completing the research study. This includes collecting data, analyzing the results, and drawing conclusions based on the findings. Once the research is complete, the report should be written in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

In academic settings, research reports are often required as part of coursework or as part of a thesis or dissertation. In this case, the report should be written according to the guidelines provided by the instructor or institution.

In other settings, such as in industry or government, research reports may be required to inform decision-making or to comply with regulatory requirements. In these cases, the report should be written as soon as possible after the research is completed in order to inform decision-making in a timely manner.

Overall, the timing of when to write a research report depends on the purpose of the research, the expectations of the audience, and any regulatory requirements that need to be met. However, it is important to complete the report in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

Characteristics of Research Report

There are several characteristics of a research report that distinguish it from other types of writing. These characteristics include:

- Objective: A research report should be written in an objective and unbiased manner. It should present the facts and findings of the research study without any personal opinions or biases.

- Systematic: A research report should be written in a systematic manner. It should follow a clear and logical structure, and the information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand and follow.

- Detailed: A research report should be detailed and comprehensive. It should provide a thorough description of the research methods, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research report should be accurate and based on sound research methods. The findings and conclusions should be supported by data and evidence.

- Organized: A research report should be well-organized. It should include headings and subheadings to help the reader navigate the report and understand the main points.

- Clear and concise: A research report should be written in clear and concise language. The information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand, and unnecessary jargon should be avoided.

- Citations and references: A research report should include citations and references to support the findings and conclusions. This helps to give credit to other researchers and to provide readers with the opportunity to further explore the topic.

Advantages of Research Report

Research reports have several advantages, including:

- Communicating research findings: Research reports allow researchers to communicate their findings to a wider audience, including other researchers, stakeholders, and the general public. This helps to disseminate knowledge and advance the understanding of a particular topic.

- Providing evidence for decision-making : Research reports can provide evidence to inform decision-making, such as in the case of policy-making, program planning, or product development. The findings and conclusions can help guide decisions and improve outcomes.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research on a particular topic. Other researchers can build on the findings and conclusions of the report, which can lead to further discoveries and advancements in the field.

- Demonstrating expertise: Research reports can demonstrate the expertise of the researchers and their ability to conduct rigorous and high-quality research. This can be important for securing funding, promotions, and other professional opportunities.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies. Producing a high-quality research report can help ensure compliance with these requirements.

Limitations of Research Report

Despite their advantages, research reports also have some limitations, including:

- Time-consuming: Conducting research and writing a report can be a time-consuming process, particularly for large-scale studies. This can limit the frequency and speed of producing research reports.

- Expensive: Conducting research and producing a report can be expensive, particularly for studies that require specialized equipment, personnel, or data. This can limit the scope and feasibility of some research studies.

- Limited generalizability: Research studies often focus on a specific population or context, which can limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or contexts.

- Potential bias : Researchers may have biases or conflicts of interest that can influence the findings and conclusions of the research study. Additionally, participants may also have biases or may not be representative of the larger population, which can limit the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Accessibility: Research reports may be written in technical or academic language, which can limit their accessibility to a wider audience. Additionally, some research may be behind paywalls or require specialized access, which can limit the ability of others to read and use the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Report Writing Format, Tips, Samples and Examples

Pankaj dhiman.

- Created on December 11, 2023

How to Write a Report: A Complete Guide (Format, Tips, Common Mistakes, Samples and Examples of Report Writing)

Struggling to write clear, concise reports that impress? Fear not! This blog is your one-stop guide to mastering report writing . Learn the essential format, uncover impactful tips, avoid common pitfalls, and get inspired by real-world examples.

Whether you’re a student, professional, or simply seeking to communicate effectively, this blog empowers you to craft compelling reports that leave a lasting impression.

Must Read: Notice Writing: How to write, Format, Examples

What is Report Writing ?

Report Writing – Writing reports is an organized method of communicating ideas, analysis, and conclusions to a target audience for a predetermined goal. It entails the methodical presentation of information, statistics, and suggestions, frequently drawn from study or inquiry.

Its main goal is to inform, convince, or suggest actions, which makes it a crucial ability in a variety of professional domains.

A well-written report usually has a concise conclusion, a well-thought-out analysis, a clear introduction, a thorough methodology, and a presentation of the findings.

It doesn’t matter what format is used as long as information is delivered in a logical manner, supports decision-making, and fosters understanding among stakeholders.

Must Read : Article Writing Format, Objective, Common Mistakes, and Samples

Format of Report Writing

- Title Page:

- Title of the report.

- Author’s name.

- Date of submission.

- Any relevant institutional affiliations.

- Abstract/Summary:

- A brief overview of the report’s key points.

- Summarizes the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions.

- Table of Contents:

- Lists all sections and subsections with corresponding page numbers.

Introduction:

- Provides background information on the subject.

- Clearly states the purpose and objectives of the report.

- Methodology:

- Details how the information was gathered or the experiment conducted.

- Includes any relevant procedures, tools, or techniques used.

- Findings/Results:

- Presents the main outcomes, data, or observations.

- Often includes visual aids such as charts, graphs, or tables.

- Discussion:

- Analyzes and interprets the results.

- Provides context and explanations for the findings.

Conclusion:

- Summarizes the key points.

- May include recommendations or implications.

Must Read: Directed Writing: Format, Benefits, Topics, Common Mistakes and Examples

Report Writing Examples – Solved Questions from previous papers

Example 1: historical event report.

Question : Write a report on the historical significance of the “ Battle of Willow Creek ” based on the research of Sarah Turner. Analyze the key events, outcomes, and the lasting impact on the region.

Solved Report:

Title: Historical Event Report – The “Battle of Willow Creek” by Sarah Turner

This report delves into the historical significance of the “Battle of Willow Creek” based on the research of Sarah Turner. Examining key events, outcomes, and the lasting impact on the region, it sheds light on a pivotal moment in our local history.

Sarah Turner’s extensive research on the “Battle of Willow Creek” provides a unique opportunity to explore a critical chapter in our local history. This report aims to unravel the intricacies of this historical event.

Key Events:

The Battle of Willow Creek unfolded on [date] between [opposing forces]. Sarah Turner’s research meticulously outlines the sequence of events leading to the conflict, including the political climate, disputes over resources, and the strategies employed by both sides.

Through Turner’s insights, we gain a nuanced understanding of the immediate outcomes of the battle, such as changes in territorial control and the impact on the local population. The report highlights the consequences that rippled through subsequent years.

Lasting Impact:

Sarah Turner’s research underscores the enduring impact of the Battle of Willow Creek on the region’s development, cultural identity, and socio-political landscape. The report examines how the event shaped the community we know today.

The “Battle of Willow Creek,” as explored by Sarah Turner, emerges as a significant historical event with far-reaching consequences. Understanding its intricacies enriches our appreciation of local history and its role in shaping our community.

Access the Learning Platform

Report writing Samples

book review report.

Title: Book Review – “The Lost City” by Emily Rodriguez

“The Lost City” by Emily Rodriguez is an enthralling adventure novel that takes readers on a captivating journey through uncharted territories. The author weaves a tale of mystery, discovery, and self-realization that keeps the reader engaged from beginning to end.

Themes and Characters:

Rodriguez skillfully explores themes of resilience, friendship, and the pursuit of the unknown. The characters are well-developed, each contributing uniquely to the narrative. The protagonist’s transformation throughout the story adds depth to the overall theme of self-discovery.

Plot and Pacing:

The plot is intricately crafted, with twists and turns that maintain suspense and intrigue. Rodriguez’s ability to balance action scenes with moments of introspection contributes to the novel’s well-paced narrative.

Writing Style:

The author’s writing style is engaging and descriptive, allowing readers to vividly envision the settings and empathize with the characters. Dialogue flows naturally, enhancing the overall readability of the book.

“The Lost City” is a commendable work by Emily Rodriguez, showcasing her storytelling prowess and ability to create a captivating narrative. This novel is recommended for readers who enjoy adventure, mystery, and character-driven stories.

Must Read: What is Descriptive Writing? Learn how to write, Examples and Secret Tips

Report Writing Tips

Recognise your audience:

Take into account your target audience’s expectations and degree of knowledge. Adjust the content, tone, and language to the readers’ needs.

Precision and succinctness:

To communicate your point, use language that is simple and unambiguous. Steer clear of convoluted sentences or needless jargon that could confuse the reader.

Logical Structure:

Organize your report with a clear and logical structure, including sections like introduction, methodology, findings, discussion, and conclusion.

Use headings and subheadings to improve readability.

Introduction with Purpose:

Clearly state the purpose, objectives, and scope of the report in the introduction.

Provide context to help readers understand the importance of the information presented.

Methodology Details:

Clearly explain the methods or processes used to gather information.

Include details that would allow others to replicate the study or experiment.

Presentation of Findings:

Give a well-organized and structured presentation of your findings.

Employ graphics (tables, graphs, and charts) to support the text and improve comprehension.

Talk and Interpretation:

Examine the findings and talk about the ramifications.

Explain the significance of the results and how they relate to the main goal.

Brief Conclusion:

Recap the main ideas in the conclusion.

Indicate in detail any suggestions or actions that should be implemented in light of the results.

Explore the Access Platform

Common mistakes for Report Writing

Insufficient defining:.

Error: Employing ambiguous or imprecise wording that could cause misunderstandings.

Impact: It’s possible that readers won’t grasp the content, which could cause misunderstandings and confusion.

Solution: Explain difficult concepts, use clear language, and express ideas clearly.

Inadequate Coordination:

Error: Not adhering to a coherent and systematic format for the report.

Impact: The report’s overall effectiveness may be lowered by readers finding it difficult to follow the information’s flow due to the report’s lack of structure.

Solution: Make sure the sections are arranged clearly and sequentially, each of which adds to the report’s overall coherence.

Inadequate Research:

Error: Conducting insufficient research or relying on incomplete data.

Impact: Inaccuracies in data or lack of comprehensive information can weaken the report’s credibility and reliability.

Solution: Thoroughly research the topic, use reliable sources, and gather comprehensive data to support your findings.

Inconsistent Formatting:

Error: Using inconsistent formatting for headings, fonts, or spacing throughout the report.

Impact: Inconsistent formatting can make the report look unprofessional and distract from the content.

Solution: Maintain a uniform format for headings, fonts, and spacing to enhance the visual appeal and professionalism of the report.

Unsubstantiated Conclusions:

Error: Drawing conclusions that are not adequately supported by the evidence or findings presented.

Impact: Unsubstantiated conclusions can undermine the report’s credibility and weaken the overall argument.

Solution: Ensure that your conclusions are directly derived from the results and are logically connected to your research objectives, providing sufficient evidence to support your claims.

To sum up, proficient report writing necessitates precision, organization, and clarity. Making impactful reports requires avoiding common errors like ambiguous wording, shoddy organization, inadequate research, inconsistent formatting, and conclusions that are not supported by evidence.

One can improve the caliber and legitimacy of their reports by following a logical format, carrying out extensive research, staying clear, and providing conclusions that are supported by evidence.

Aiming for linguistic accuracy and meticulousness guarantees that the desired meaning is communicated successfully, promoting a deeper comprehension of the topic among readers.

See author's posts

Recent Posts

- Tutopiya Unveils AI Tutor for IGCSE Maths Exams

- Educate and Empower: Subscribe to Tutopiya, Gift Education to Africa

- IGCSE Curriculum: Top 10 Benefits for Students

- Edexcel IGCSE: Benefits, Subjects, Syllabus, Pricing, and Tips for Edexcel IGCSE Success

- Navigating the AI Education Landscape: Trends in Singapore

- IGCSE Tutors Dubai: Affordable Group Classes, Boost Grades, Expert Tutors, Proven Results

- Empowering Minds: The Inspiring Journey of Fathima Safra Azmi

- Mastering IGCSE: Ace Your Exams in 3 Months with Our Unlimited Learning Program

- IGCSE Exam 2024 Revision: 10 Tips and Tricks to Score A*

- How to Ace Your IGCSE Exam in 3 Months: A Comprehensive Guide to Score A*

Get Started

Learner guide

Tutor guide

Curriculums

IGCSE Tuition

PSLE Tuition

SIngapore O Level Tuition

Singapore A Level Tuition

SAT Tuition

Math Tuition

Additional Math Tuition

English Tuition

English Literature Tuition

Science Tuition

Physics Tuition

Chemistry Tuition

Biology Tuition

Economics Tuition

Business Studies Tuition

French Tuition

Spanish Tuition

Chinese Tuition

Computer Science Tuition

Geography Tuition

History Tuition

TOK Tuition

Privacy policy

22 Changi Business Park Central 2, #02-08, Singapore, 486032

All rights reserved

©2022 tutopiya

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement

- Giving Opportunities

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

Many believe that a scientist’s most difficult job is not conducting an experiment but presenting the results in an effective and coherent way. Even when your methods and technique are sound and your notes are comprehensive, writing a report can be a challenge because organizing and communicating scientific findings requires patience and a thorough grasp of certain conventions. Having a clear understanding of the typical goals and strategies for writing an effective lab report can make the process much less troubling.

General Considerations

It is useful to note that effective scientific writing serves the same purpose that your lab report should. Good scientific writing explains:

- The goal(s) of your experiment

- How you performed the experiment

- The results you obtained

- Why these results are important

While it’s unlikely that you’re going to win the Nobel Prize for your work in an undergraduate laboratory course, tailoring your writing strategies in imitation of professional journals is easier than you might think, since they all follow a consistent pattern. However, your instructor has the final say in determining how your report should be structured and what should appear in each section. Please use the following explanations only to supplement your given writing criteria, rather than thinking of them as an indication of how all lab reports must be written.

In Practice

The Structure of a Report

The traditional experimental report is structured using the acronym “IMRAD” which stands for I ntroduction, M ethods, R esults and D iscussion. The “ A ” is sometimes used to stand for A bstract. For help writing abstracts, please see Sweetland’s resource entitled “What is an abstract, and how do I write one?”

Introduction: “What am I doing here?” The introduction should accomplish what any good introduction does: draw the reader into the paper. To simplify things, follow the “inverted pyramid” structure, which involves narrowing information from the most broad (providing context for your experiment’s place in science) to the most specific (what exactly your experiment is about). Consider the example below.

Most broad: “Caffeine is a mild stimulant that is found in many common beverages, including coffee.”

Less broad: “Common reactions to caffeine use include increased heart rate and increased respiratory rate.”

Slightly more specific (moving closer to your experiment): Previous research has shown that people who consume multiple caffeinated beverages per day are also more likely to be irritable.

Most specific (your experiment): This study examines the emotional states of college students (ages 18-22) after they have consumed three cups of coffee each day.

See how that worked? Each idea became slightly more focused, ending with a brief description of your particular experiment. Here are a couple more tips to keep in mind when writing an introduction:

- Include an overview of the topic in question, including relevant literature A good example: “In 1991, Rogers and Hammerstein concluded that drinking coffee improves alertness and mental focus (citation 1991).

- Explain what your experiment might contribute to past findings A good example: “Despite these established benefits, coffee may negatively impact mood and behavior. This study aims to investigate the emotions of college coffee drinkers during finals week.”

- Keep the introduction brief There’s no real advantage to writing a long introduction. Most people reading your paper already know what coffee is, and where it comes from, so what’s the point of giving them a detailed history of the coffee bean? A good example: “Caffeine is a psychoactive stimulant, much like nicotine.” (Appropriate information, because it gives context to caffeine—the molecule of study) A bad example: “Some of the more popular coffee drinks in America include cappuccinos, lattés, and espresso.” (Inappropriate for your introduction. This information is useless for your audience, because not only is it already familiar, but it doesn’t mention anything about caffeine or its effects, which is the reason that you’re doing the experiment.)

- Avoid giving away the detailed technique and data you gathered in your experiment A good example: “A sample of coffee-drinking college students was observed during end-of-semester exams.” ( Appropriate for an introduction ) A bad example: “25 college students were studied, and each given 10oz of premium dark roast coffee (containing 175mg caffeine/serving, except for Folgers, which has significantly lower caffeine content) three times a day through a plastic straw, with intervals of two hours, for three weeks.” ( Too detailed for an intro. More in-depth information should appear in your “Methods” or “Results” sections. )

Methods: “Where am I going to get all that coffee…?”

A “methods” section should include all the information necessary for someone else to recreate your experiment. Your experimental notes will be very useful for this section of the report. More or less, this section will resemble a recipe for your experiment. Don’t concern yourself with writing clever, engaging prose. Just say what you did, as clearly as possible. Address the types of questions listed below:

- Where did you perform the experiment? (This one is especially important in field research— work done outside the laboratory.)

- How much did you use? (Be precise.)

- Did you change anything about them? (i.e. Each 5 oz of coffee was diluted with 2 oz distilled water.)

- Did you use any special method for recording data? (i.e. After drinking coffee, students’ happiness was measured using the Walter Gumdrop Rating System, on a scale of 1-10.)

- Did you use any techniques/methods that are significant for the research? (i.e. Maybe you did a double blinded experiment with X and Y as controls. Was your control a placebo? Be specific.)

- Any unusual/unique methods for collecting data? If so, why did you use them?

After you have determined the basic content for your “methods” section, consider these other tips:

- Decide between using active or passive voice

There has been much debate over the use of passive voice in scientific writing. “Passive voice” is when the subject of a sentence is the recipient of the action.

- For example: Coffee was given to the students.

“Active voice” is when the subject of a sentence performs the action.

- For example: I gave coffee to the students.

The merits of using passive voice are obvious in some cases. For instance, scientific reports are about what is being studied, and not about YOU. Using too many personal pronouns can make your writing sound more like a narrative and less like a report. For that reason, many people recommend using passive voice to create a more objective, professional tone, emphasizing what was done TO your subject. However, active voice is becoming increasingly common in scientific writing, especially in social sciences, so the ultimate decision of passive vs. active voice is up to you (and whoever is grading your report).

- Units are important When using numbers, it is important to always list units, and keep them consistent throughout the section. There is a big difference between giving someone 150 milligrams of coffee and 150 grams of coffee—the first will keep you awake for a while, and the latter will put you to sleep indefinitely. So make sure you’re consistent in this regard.

- Don’t needlessly explain common techniques If you’re working in a chemistry lab, for example, and you want to take the melting point of caffeine, there’s no point saying “I used the “Melting point-ometer 3000” to take a melting point of caffeine. First I plugged it in…then I turned it on…” Your reader can extrapolate these techniques for him or herself, so a simple “Melting point was recorded” will work just fine.

- If it isn’t important to your results, don’t include it No one cares if you bought the coffee for your experiment on “3 dollar latte day”. The price of the coffee won’t affect the outcome of your experiment, so don’t bore your reader with it. Simply record all the things that WILL affect your results (i.e. masses, volumes, numbers of trials, etc).

Results: The only thing worth reading?

The “results” section is the place to tell your reader what you observed. However, don’t do anything more than “tell.” Things like explaining and analyzing belong in your discussion section. If you find yourself using words like “because” or “which suggests” in your results section, then STOP! You’re giving too much analysis.

A good example: “In this study, 50% of subjects exhibited symptoms of increased anger and annoyance in response to hearing Celine Dion music.” ( Appropriate for a “results” section—it doesn’t get caught up in explaining WHY they were annoyed. )

In your “results” section, you should:

- Display facts and figures in tables and graphs whenever possible. Avoid listing results like “In trial one, there were 5 students out of 10 who showed irritable behavior in response to caffeine. In trial two…” Instead, make a graph or table. Just be sure to label it so you can refer to it in your writing (i.e. “As Table 1 shows, the number of swear words spoken by students increased in proportion to the amount of coffee consumed.”) Likewise, be sure to label every axis/heading on a chart or graph (a good visual representation can be understood on its own without any textual explanation). The following example clearly shows what happened during each trial of an experiment, making the trends visually apparent, and thus saving the experimenter from having to explain each trial with words.

- Identify only the most significant trends. Don’t try to include every single bit of data in this section, because much of it won’t be relevant to your hypothesis. Just pick out the biggest trends, or what is most significant to your goals.

Discussion: “What does it all mean?”

The “discussion” section is intended to explain to your reader what your data can be interpreted to mean. As with all science, the goal for your report is simply to provide evidence that something might be true or untrue—not to prove it unequivocally. The following questions should be addressed in your “discussion” section:

- Is your hypothesis supported? If you didn’t have a specific hypothesis, then were the results consistent with what previous studies have suggested? A good example: “Consistent with caffeine’s observed effects on heart rate, students’ tendency to react strongly to the popping of a balloon strongly suggests that caffeine’s ability to heighten alertness may also increase nervousness.”

- Was there any data that surprised you? Outliers are seldom significant, and mentioning them is largely useless. However, if you see another cluster of points on a graph that establish their own trend, this is worth mentioning.

- Are the results useful? If you have no significant findings, then just say that. Don’t try to make wild claims about the meanings of your work if there is no statistical/observational basis for these claims—doing so is dishonest and unhelpful to other scientists reading your work. Similarly, try to avoid using the word “proof” or “proves.” Your work is merely suggesting evidence for new ideas. Just because things worked out one way in your trials, that doesn’t mean these results will always be repeatable or true.

- What are the implications of your work? Here are some examples of the types of questions that can begin to show how your study can be significant outside of this one particular experiment: Why should anyone care about what you’re saying? How might these findings affect coffee drinkers? Do your findings suggest that drinking coffee is more harmful than previously thought? Less harmful? How might these findings affect other fields of science? What about the effects of caffeine on people with emotional disorders? Do your findings suggest that they should or should not drink coffee?

- Any shortcomings of your work? Were there any flaws in your experimental design? How should future studies in this field accommodate for these complications. Does your research raise any new questions? What other areas of science should be explored as a result of your work?

Resources: Hogg, Alan. "Tutoring Scientific Writing." Sweetland Center for Writing. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. 3/15/2011. Lecture. Swan, Judith A, and George D. Gopen. "The Science of Scientific Writing." American Scientist . 78. (1990): 550-558. Print. "Scientific Reports." The Writing Center . University of North Carolina, n.d. Web. 5 May 2011. http://www.unc.edu/depts/wcweb/handouts/lab_report_complete.html

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

Project Report Writing and Presentations

- First Online: 20 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Habeeb Adewale Ajimotokan 2

Part of the book series: SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology ((BRIEFSAPPLSCIENCES))

940 Accesses

The objectives of this chapter are to

Specify and discuss the basic chapter titles and sub-titles in a research project report;

Prepare a research project report based on the basic format;

Specify and explain the basic methods of writing bibliography, citing and listing references;

Discuss research presentations;

Describe plagiarism and citation; and

Discuss citation and its management.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Thiel, D. V. (2014). Research methods for engineers . Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Lues, L., & Lategan, L. O. K. (2006). RE: Search ABC (1st ed.). Sun Press.

Google Scholar

Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. C., & Williams, J. M. (2008). The craft of research . University of Chicago Press.

Snieder, R., & Lamer, K. (2009). The art of being a scientist: A guide for graduate students and their mentors . University Printing House, University of Cambridge.

Alley, M. (2003). The craft of scientific presentations: Critical steps to succeed and critical errors to avoid . Springer-Verlag.

Hofmann, A. H. (2009). Scientific writing and communications: Papers, proposals and presentations . Oxford University Press.

University of Oxford. (2019). Plagiarism. Retrieved from https://www.ox.ac.uk/students/academic/guidance/skills/plagiarism?wssl=1

Neville, C. (2007). The complete guide to referencing and avoiding plagiarism . Open University Press.

Walliman, N. (2011). Research methods: The basics . Routledge—Taylor and Francis Group.