Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Social Science — The Vital Significance of Social Science in Our Daily Lives

The Vital Significance of Social Science in Our Daily Lives

- Categories: Personal Life Social Science

About this sample

Words: 800 |

Published: Sep 12, 2023

Words: 800 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Understanding human behavior, shaping public policy, enhancing personal finance, addressing social issues, fostering global citizenship, enhancing critical thinking and problem-solving, informing personal values and ethics.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 968 words

3 pages / 1372 words

3 pages / 1314 words

7 pages / 3213 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Social Science

The realms of knowledge encompass a vast array of disciplines, each with its own unique methods and approaches. Two broad categories within this spectrum are the natural sciences and the social sciences. While they may appear [...]

The political landscape of the United States has evolved significantly over the past few decades. Among the most notable shifts is the emergence of a new generation of left-leaning individuals who are more vocal, more radical, [...]

The distinction between natural science and social science has been a topic of debate for centuries. Both fields seek to understand the world around us, but they do so through different lenses and methodologies. Natural science [...]

Penelope Eckert and Sally McConnell-Ginet's essay, "Learning to Be..." delves into the complex and multifaceted nature of gender identity and its development. The authors explore the ways in which individuals learn to perform [...]

Globalization is the process of greater interdependence among countries and their citizens. It consists of increased integration of product and resource market across nations via trade, immigration and foreign investment. Via [...]

Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded and William Godwin’s Caleb Williams are both novels that deal with the influence of social hierarchy on the characters’ psychologies. In Caleb Williams, the protagonist is a young [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Communication

What is a Social Science Essay?

[Ed. – We present this article, adapted from a chapter of Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide , as a resource for Academic Writing Month.]

There are different types of social science essay, and essays of different lengths require slightly different approaches (these will be addressed later). However, all social science essays share a basic structure which is common to many academic subject areas. At its simplest, a social science essay looks something like this:

Title | Every essay should begin with the title written out in full. In some cases this will simply be the set question or statement for discussion.

Introduction | The introduction tells the reader what the essay is about.

Main section | The main section, or ‘body’, of the essay develops the key points of the argument in a ‘logical progression’. It uses evidence from research studies (empirical evidence) and theoretical arguments to support these points.

Conclusion | The conclusion reassesses the arguments presented in the main section in order to make a final statement in answer to the question.

List of references | This lists full details of the publications referred to in the text.

What is distinctive about a social science essay?

As you are no doubt aware, essay writing is a common feature of undergraduate study in many different subjects. What, then, is distinctive about essay writing in the social sciences? There are particular features that characterize social science essays and that relate to what is called the epistemological underpinning of work in this area (that is, to ideas about what constitutes valid social scientific knowledge and where this comes from). Among the most important of these characteristics are:

• the requirement that you support arguments with evidence, particularly evidence that is the product of systematic and rigorous research;

• the use of theory to build explanations about how the social world works.

Evidence is important in social scientific writing because it is used to support or query beliefs, propositions or hypotheses about the social world. Let’s take an example. A social scientist may ask: ‘Does prison work?’ This forms an initial question, but one that is too vague to explore as it stands. (This question might be about whether prison ‘works’ for offenders, in terms of providing rehabilitation, or re-education; or it might be about whether it ‘works’ for victims of crime who may wish to see retribution – or any number of other issues.) To answer the question in mind, the social scientist will need to formulate a more specific claim, one that can be systematically and rigorously explored. Such a claim could be formulated in the following terms:

‘Imprisonment reduces the likelihood of subsequent reoffending’. This claim can now be subjected to systematic research. In other words, the social scientist will gather evidence for and against this claim, evidence that she or he will seek to interpret or evaluate. This process of evaluation will tend to support or refute the original claim, but it may be inconclusive, and/or it may generate further questions. Together, these processes of enquiry can be described as forming a ‘circuit of social scientific knowledge’. This circuit can be represented as in this figure.

Undergraduates may sometimes be asked to conduct their own small-scale research, for instance a small number of interviews, or some content analysis. However, the focus of social science study at undergraduate level, and particularly in the first two years of study, will be largely on the research of others. Generally, in preparing for writing your essays, the expectation will be that you will identify and evaluate evidence from existing research findings. However, the principle holds good: in writing social science essays you will need to find evidence for and against any claim, and you will need to evaluate that evidence.

Theory is important in social scientific writing because the theoretical orientation of the social scientist will tend to inform the types of question she or he asks, the specific claims tested, the ways in which evidence is identified and gathered, and the manner in which this evidence is interpreted and evaluated. In other words, the theoretical orientation of the social scientist is liable to impact upon the forms of knowledge she or he will produce.

Take, for example, the research question we asked above: ‘Does prison work?’ A pragmatic, policy-oriented social scientist may seek to answer this question by formulating a specific claim of the sort we identified, ‘Imprisonment reduces the likelihood of reoffending’. She or he may then gather evidence of reoffending rates among matched groups of convicted criminals, comparing those who were imprisoned with those who were given an alternative punishment such as forms of community service. Evidence that imprisonment did not produce significantly lower rates of reoffending than punishment in the community may then be interpreted as suggesting that prison does not work, or that it works only up to a point. However, another social scientist might look at the same research findings and come to a different conclusion, perhaps that the apparent failure of prison to reduce reoffending demonstrates that its primary purpose lies elsewhere. Indeed, more ‘critically’ oriented social scientists (for example, those informed by Marxism or the work of Michel Foucault) have sought to argue that the growth of prisons in the nineteenth century was part of wider social attempts to ‘discipline’, in particular, the working class.

The issue here is not whether these more ‘critical’ arguments are right or wrong but that a social scientist’s theoretical orientation will inform how she or he evaluates the available evidence. In fact, it is likely that a ‘critical’ social scientist of this sort would even have formulated a different research ‘claim’. For example, rather than seeking to test the claim, ‘Imprisonment reduces the likelihood of reoffending’, the critical social scientist might have sought to test the proposition, ‘Prisons are part of wider social strategies that aim to produce “disciplined” subjects’. The point for you to take away from this discussion is, then, that the theories we use shape the forms of social scientific knowledge we produce (see Figure 2).

There is considerable debate within the social sciences about the exact relationship between theory and evidence. To simplify somewhat, some social scientists tend to argue that evidence can be used to support or invalidate the claims investigated by research and thereby produce theoretical accounts of the social world that are more or less accurate. Other social scientists will tend to argue that our theoretical orientations (and the value judgements and taken-for-granted assumptions that they contain) shape the processes of social scientific enquiry itself, such that we can never claim to produce a straightforwardly ‘accurate’ account of the social world. Instead, they suggest that social scientific knowledge is always produced from a particular standpoint and will inevitably reflect its assumptions.

What you need to grasp is that essay writing in the social sciences is distinguished by its emphasis on: the use of researched evidence to support arguments and on theory as central to the process by which we build accounts of social worlds. Your own writing will need to engage with both elements.

Common errors in essays

Having identified what distinguishes a social science essay we can return to the more practical task of how to write one. This process is elaborated in the chapters that follow, but before getting into the details of this, we should think about what commonly goes wrong in essay writing.

Perhaps the most common mistakes in essay writing, all of which can have an impact on your marks, are:

• failure to answer the question;

• failure to write using your own words;

• poor use of social scientific skills (such as handling theory and evidence);

• poor structure;

• poor grammar, punctuation and spelling; and

• failure to observe the word limit (where this is specified).

Failing to answer the question sounds easy enough to avoid, but you might be surprised how easy it is to write a good answer to the wrong question. Most obviously, there is always the risk of misreading the question. However, it is frequently the case that questions will ‘index’ a wider debate and will want you to review and engage with this. Thus, you need to avoid the danger of understanding the question but failing to connect it to the debate and the body of literature to which the question refers. Equally, particularly on more advanced undergraduate courses, you are likely to be asked to work from an increasing range of sources. The dangers here include failing to select the most relevant material and failing to organize the material you have selected in a way that best fits the question. Therefore, make sure that you take time to read the question properly to ensure that you understand what is being asked. Next, think carefully about whether there is a debate that ‘lies behind’ the question. Then be sure to identify the material that addresses the question most fully.

Writing in your own words is crucial because this is the best way in which you can come to understand a topic, and the only way of demonstrating this understanding to your tutor. The important point to remember is that if you do plagiarize, your essay risks receiving a fail grade, and if you plagiarize repeatedly you risk further sanctions. You must therefore always put arguments in your own words except when you are quoting someone directly (in which case you must use the appropriate referencing conventions). The positive side of what might seem like a draconian rule is that you will remember better what you have put in your own words. This ensures that you will have the fullest possible understanding of your course. If there is an end-of-course exam, such an understanding will be a real asset.

Social science essays also need to demonstrate an effective use of social scientific skills. Perhaps the most obvious of these skills is the ability to deploy theory and evidence in an appropriate manner (as you saw in the previous section, this is what distinguishes social scientific essay writing). However, particularly as you move on to more advanced undergraduate courses, you should also keep in mind the need to demonstrate such things as confidence in handling social scientific concepts and vocabulary; an awareness of major debates, approaches and figures in your field; the ability to evaluate competing arguments; and an awareness of potential uncertainty, ambiguity and the limits of knowledge in your subject. These are important because they indicate your ability to work creatively with the tools of the social scientist’s trade.

An effective structure is important and pragmatic because it helps the person who marks your essay to understand what is going on. By contrast, a list of unconnected ideas and examples is likely to confuse, and will certainly fail to impress. The simplest way to avoid this is to follow the kind of essay writing conventions briefly outlined above and discussed in later chapters of this guide. Chapter 8, on the main body of the essay, is particularly relevant here, but you will also need to keep in mind the importance of a well-written introduction and conclusion to an effectively structured argument.

The ability to spell, punctuate and use grammar correctly is, generally speaking, something you are expected to have mastered prior to embarking on a degree-level course. This is really a matter of effective communication. While it is the content of your essay that will win you the most marks, you need to be able spell, punctuate and use grammar effectively in order to communicate what you have to say. Major problems in this area will inevitably hold down your marks, so if this is an issue in your work, it will be a good idea to seek further help.

Finally, observing the word limit is important – and, as you probably realize, more difficult than it sounds. The simplest advice is always to check whether there is a word limit and what this is, and then to be ruthless with yourself, focusing only on the material that is most pertinent to the question. If you find that you have written more words than is allowed, you will need to check for irrelevant discussions, examples, or even wordy sentence construction. Too few words may indicate that you haven’t provided the depth of discussion required, or that you have omitted essential points or evidence.

In the light of the above, we can identify four golden rules for effective social scientific essay writing.

Rule 1: Answer the question that is asked.

Rule 2: Write your answer in your own words.

Rule 3: Think about the content of your essay, being sure to demonstrate good social scientific skills.

Rule 4: Think about the structure of your essay, being sure to demonstrate good writing skills, and observing any word limit.

Why an essay is not a report, newspaper article or an exam answer

This section has mainly focused on what is distinctive about a social science essay, but there is something distinctive about essays in general that is worth keeping in mind. Many students come from professional backgrounds where report writing is a common form of communication. For other students a main source of information is newspapers or online websites. These are all legitimate forms of writing that serve useful purposes – but, apart from some of the content on academic websites, they just aren’t essays. There are exam conventions that make exam writing – even ‘essay style’ exams – different from essay writing.

In part, this is to do with ‘academic register’ or ‘voice’. Part of what you will develop as you become a stronger essay writer is a ‘voice’ that is your own, but that conforms to the conventions of academic practice. For social scientists, as we have noted above, this practice includes the use of evidence to support an argument and providing references that show where your ideas and evidence have come from. It also includes the ability to write with some confidence, using the vernacular – or language – of your subject area. Different forms of writing serve different purposes. The main purpose of academic writing is to develop and share knowledge and understanding. In some academic journals this can take the form of boisterous debate, with different academics fully and carefully defending, or arguing for, one position or another. For students of social science, however, there may be less at stake, but essays should nevertheless demonstrate knowledge and understanding of a particular issue or area. Conforming to some basic conventions around how to present ideas and arguments, helps us more easily to compare those ideas, just as conforming to the rules of a game makes it easier for one sports team to play against another: if one team is playing cricket and the other baseball, we will find there are similarities (both use bats, have innings, make runs), but there will also be lots of awkward differences. In the end, neither the players nor the spectators are likely to find it a very edifying experience. The following looks at other forms of serious writing that you may be familiar with, but that just aren’t cricket.

Report writing

Reports take a variety of forms, but typically involve: an up-front ‘executive summary’, a series of discussions, usually with numbered headings and subheadings. They are also likely to include ‘bullet points’ that capture an idea or argument in a succinct way. Professional reports may include evidence, arguments, recommendations and references. You may already have spotted some of the similarities with essays – and the crucial differences. Let’s begin with the similarities. Reports and essays both involve discussion, the use of evidence to support (or refute) a claim or argument, and a list of references. Both will have an introductory section, a main body and a conclusion. However, the differences are important. With the exception of very long essays (dissertations and the like), essays do not generally have numbered headings and subheadings. Nor do they have bullet points. They also don’t have executive summaries. And, with some notable exceptions (such as essays around areas of social policy perhaps), social science essays don’t usually require you to produce policy recommendations. The differences are significant, and are as much about style as they are about substance.

Journalistic writing

For many students, journalistic styles of writing are most familiar. Catchy headlines (or ‘titles’) are appealing, and newspapers’ to-the-point presentation may make for easier reading. News stories, however, follow a different set of requirements to essays – a different set of ‘golden rules’. In general, newspaper and website news articles foreground the ‘who, what, where, when and why’ of a story in the first paragraph. The most important information is despatched immediately, with the assumption that all readers will read the headline, most readers will read the first paragraph, and dwindling numbers will read the remainder of the article. Everyday newspaper articles often finish with a ‘whimper’ for this reason, and there may be no attempt to summarize findings or provide a conclusion at the end – that’s not the role of news journalists. (Though there is quite a different set of rules for ‘Op Ed’ or opinion pieces.) Student essays, by contrast, should be structured to be read from beginning to end. The introduction should serve to ‘outline’ or ‘signpost’ the main body of the essay, rather than cover everything in one fell swoop; the main body should proceed with a clear, coherent and logical argument that builds throughout; and the essay should end with a conclusion that ties the essay together.

Exam writing

Again, exam writing has similarities and differences with essay writing. Perhaps the main differences are these: under exam conditions, it is understood that you are writing at speed and that you may not communicate as effectively as in a planned essay; you will generally not be expected to provide references (though you may be expected to link clearly authors and ideas). Longer exam answers will need to include a short introduction and a conclusion, while short answers may omit these. Indeed, very short answers may not resemble essays at all as they may focus on factual knowledge or very brief points of comparison.

Peter Redman and Wendy Maples

Peter Redman is a senior lecturer in sociology at The Open University. With Stephen Frosh and Wendy Hollway, he edit the Palgrave book series, Studies in the Psychosocial and is a former editor of the journal, Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society . Academic consultant Wendy Maples is a research assistant in anthropology at the University of Sussex. Together they co-authored Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide (Sage, 2017) now in its fifth edition.

Related Articles

Young Explorers Award Honors Scholars at Nexus of Life and Social Science

Celebrating 20 Years of an Afrocentric Small Scholarly Press

Striving for Linguistic Diversity in Scientific Research

Third Edition of ‘The Evidence’: How Can We Overcome Sexism in AI?

Second Edition of ‘The Evidence’ Examines Women and Climate Change

The second issue of The Evidence explores the intersection of gender inequality and the global climate crisis. Author Josephine Lethbridge recounts the […]

New Funding Opportunity for Criminal and Juvenile Justice Doctoral Researchers

A new collaboration between the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) and the U.S. National Science Foundation has founded the Graduate Research Fellowship […]

Economist Kaye Husbands Fealing to Lead NSF’s Social Science Directorate

Kaye Husbands Fealing, an economist who has done pioneering work in the “science of broadening participation,” has been named the new leader of the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

NIH Matilda White Riley Behavioral and Social Sciences Honors

Mark kleiman innovation for public policy memorial lecture , talk: the evidence-to-policy pipeline, webinar – navigating the era of artificial intelligence: achieving human-ai harmony, webinar: how to write and structure an article’s front matter, webinar: how to get more involved with a journal and develop your career, science of team science 2024 virtual conference, webinar: how to collaborate across paradigms – embedding culture in mixed methods designs, american psychological association annual convention, societal impact of social sciences, humanities, and arts 2024, cspc 2024: 16th canadian science policy conference.

Customize your experience

Select your preferred categories.

- Announcements

- Business and Management INK

Higher Education Reform

Open access, recent appointments, research ethics, interdisciplinarity, international debate.

- Academic Funding

Public Engagement

- Recognition

Presentations

Science & social science, social science bites, the data bulletin.

New Fellowship for Community-Led Development Research of Latin America and the Caribbean Now Open

Thanks to a collaboration between the Inter-American Foundation (IAF) and the Social Science Research Council (SSRC), applications are now being accepted for […]

Social, Behavioral Scientists Eligible to Apply for NSF S-STEM Grants

Solicitations are now being sought for the National Science Foundation’s Scholarships in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics program, and in an unheralded […]

With COVID and Climate Change Showing Social Science’s Value, Why Cut it Now?

What are the three biggest challenges Australia faces in the next five to ten years? What role will the social sciences play in resolving these challenges? The Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia asked these questions in a discussion paper earlier this year. The backdrop to this review is cuts to social science disciplines around the country, with teaching taking priority over research.

Aiming to spur greater connections between the life and social sciences, Science magazine and NOMIS look to recognize young researchers through the NOMIS and Science Young Explorers Award.

AAPSS Names Eight as 2024 Fellows

The American Academy of Political and Social Science today named seven scholars and one journalist as its 2024 fellows class.

Apply for Sage’s 2024 Concept Grants

Three awards are available through Sage’s Concept Grant program, which is designed to support innovative products and tools aimed at enhancing social science education and research.

New Podcast Series Applies Social Science to Social Justice Issues

Sage (the parent of Social Science Space) and the Surviving Society podcast have launched a collaborative podcast series, Social Science for Social […]

Big Think Podcast Series Launched by Canadian Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences

The Canadian Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences has launched the Big Thinking Podcast, a show series that features leading researchers in the humanities and social sciences in conversation about the most important and interesting issues of our time.

The We Society Explores Intersectionality and Single Motherhood

In a recently released episode of The We Society podcast, Ann Phoenix, a psychologist at University College London’s Institute of Education, spoke […]

This month’s installment of The Evidence explores how leading ethics experts are responding to the urgent dilemma of gender bias in AI. […]

New Report Finds Social Science Key Ingredient in Innovation Recipe

A new report from Britain’s Academy of Social Sciences argues that the key to success for physical science and technology research is a healthy helping of relevant social science.

A Social Scientist Looks at the Irish Border and Its Future

‘What Do We Know and What Should We Do About the Irish Border?’ is a new book from Katy Hayward that applies social science to the existing issues and what they portend.

Brexit and the Decline of Academic Internationalism in the UK

Brexit seems likely to extend the hostility of the UK immigration system to scholars from European Union countries — unless a significant change of migration politics and prevalent public attitudes towards immigration politics took place in the UK. There are no indications that the latter will happen anytime soon.

Brexit and the Crisis of Academic Cosmopolitanism

A new report from the Royal Society about the effects on Brexit on science in the United Kingdom has our peripatetic Daniel Nehring mulling the changes that will occur in higher education and academic productivity.

Motivation of Young Project Professionals: Their Needs for Autonomy, Competence, Relatedness, and Purpose

Young professionals born between the early 1980s and mid-1990s now constitute a majority of the project management workforce. Having grown up connected, collaborative, and mobile, they have specific motivations and needs, which are explored in this study.

A Complexity Framework for Project Management Strategies

Contemporary projects frequently pose complexities that cannot be adequately tackled by the classical project management tradition. This article offers a diagnostic tool to help identify the type of complexity of a project and determine the most suitable strategy for addressing it.

Bringing Theories into Conversation to Strategize for a Better World

In this article, Ann Langley, Rikkie Albertsen, Shahzad (Shaz) Ansari, Katrin Heucher, Marc Krautzberger, Pauline Reinecke, Natalie Slawinski, and Eero Vaara reflect on the inspiration behind their research article, “Strategizing Together for a Better World: Institutional, Paradox and Practice Theories in Conversation,” found in the Journal of Management Inquiry.

2024 Holberg Prize Goes to Political Theorist Achille Mbembe

Political theorist and public intellectual Achille Mbembe, among the most read and cited scholars from the African continent, has been awarded the 2024 Holberg Prize.

Edward Webster, 1942-2024: South Africa’s Pioneering Industrial Sociologist

Eddie Webster, sociologist and emeritus professor at the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, died on March 5, 2024, at age 82.

Charles V. Hamilton, 1929-2023: The Philosopher Behind ‘Black Power’

Political scientist Charles V. Hamilton, the tokenizer of the term ‘institutional racism,’ an apostle of the Black Power movement, and at times deemed both too radical and too deferential in how to fight for racial equity, died on November 18, 2023. He was 94.

National Academies Seeks Experts to Assess 2020 U.S. Census

The National Academies’ Committee on National Statistics seeks nominations for members of an ad hoc consensus study panel — sponsored by the U.S. Census Bureau — to review and evaluate the quality of the 2020 Census.

Will the 2020 Census Be the Last of Its Kind?

Could the 2020 iteration of the United States Census, the constitutionally mandated count of everyone present in the nation, be the last of its kind?

Will We See A More Private, But Less Useful, Census?

Census data can be pretty sensitive – it’s not just how many people live in a neighborhood, a town, a state or […]

To mark the Black- and female-owned Universal Write Publications’ 20th anniversary, Sage’s Geane De Lima asked UWP fonder Ayo Sekai some questions about UWP’s past, present and future.

Each country has its own unique role to play in promoting greater linguistic diversity in scientific communication.

Free Online Course Reveals The Art of ChatGPT Interactions

You’ve likely heard the hype around artificial intelligence, or AI, but do you find ChatGPT genuinely useful in your professional life? A free course offered by Sage Campus could change all th

The Importance of Using Proper Research Citations to Encourage Trustworthy News Reporting

Based on a study of how research is cited in national and local media sources, Andy Tattersall shows how research is often poorly represented in the media and suggests better community standards around linking to original research could improve trust in mainstream media.

Research Integrity Should Not Mean Its Weaponization

Commenting on the trend for the politically motivated forensic scrutiny of the research records of academics, Till Bruckner argues that singling out individuals in this way has a chilling effect on academic freedom and distracts from efforts to address more important systemic issues in research integrity.

What Do We Know about Plagiarism These Days?

In the following Q&A, Roger J. Kreuz, a psychology professor who is working on a manuscript about the history and psychology of plagiarism, explains the nature and prevalence of plagiarism and the challenges associated with detecting it in the age of AI.

This two-part webinar series, funded through the Hauser Policy Impact Fund, will explore the Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education’s […]

Recent years have seen a large increase in the availability of rigorous impact evaluations that could inform policy decisions. However, it is […]

Discussion: Promoting a Culture of Research Impact

This discussion on the importance of research impact with Tamika Heiden and Melinda Mills aims to demystify the various pathways through which […]

Exploring ‘Lost Person Behavior’ and the Science of Search and Rescue

What is the best strategy for finding someone missing in the wilderness? It’s complicated, but the method known as ‘Lost Person Behavior’ seems to offers some hope.

New Opportunity to Support Government Evaluation of Public Participation and Community Engagement Now Open

The President’s Management Agenda Learning Agenda: Public Participation & Community Engagement Evidence Challenge is dedicated to forming a strategic, evidence-based plan that federal agencies and external researchers can use to solve big problems.

The Power of Fuzzy Expectations: Enhancing Equity in Australian Higher Education

Having experienced firsthand the transformational power of education, the authors wanted to shed light on the contemporary challenges faced by regional and remote university students.

Using Translational Research as a Model for Long-Term Impact

Drawing on the findings of a workshop on making translational research design principles the norm for European research, Gabi Lombardo, Jonathan Deer, Anne-Charlotte Fauvel, Vicky Gardner and Lan Murdock discuss the characteristics of translational research, ways of supporting cross disciplinary collaboration, and the challenges and opportunities of adopting translational principles in the social sciences and humanities.

Survey Suggests University Researchers Feel Powerless to Take Climate Change Action

To feel able to contribute to climate action, researchers say they need to know what actions to take, how their institutions will support them and space in their workloads to do it.

Three Decades of Rural Health Research and a Bumper Crop of Insights from South Africa

A longitudinal research project project covering 31 villages in rural South Africa has led to groundbreaking research in many fields, including genomics, HIV/Aids, cardiovascular conditions and stroke, cognition and aging.

Why Social Science? Because It Makes an Outsized Impact on Policy

Euan Adie, founder of Altmetric and Overton and currently Overton’s managing director, answers questions about the outsized impact that SBS makes on policy and his work creating tools to connect the scholarly and policy worlds.

Infrastructure

To Better Forecast AI, We Need to Learn Where Its Money Is Pointing

By carefully interrogating the system of economic incentives underlying innovations and how technologies are monetized in practice, we can generate a better understanding of the risks, both economic and technological, nurtured by a market’s structure.

Maybe You Can’t Buy Happinesss, But You Can Teach About It

When you deliver a university course that makes students happier, everybody wants to know what the secret is. What are your tips? […]

There’s Something in the Air, Part 2 – But It’s Not a Miasma

Robert Dingwall looks at the once dominant role that miasmatic theory had in public health interventions and public policy.

The Fog of War

David Canter considers the psychological and organizational challenges to making military decisions in a war.

Civilisation – and Some Discontents

The TV series Civilisation shows us many beautiful images and links them with a compelling narrative. But it is a narrative of its time and place.

Philip Rubin: FABBS’ Accidental Essential Man Linking Research and Policy

As he stands down from a two-year stint as the president of the Federation of Associations in Behavioral & Brain Sciences, or FABBS, Social Science Space took the opportunity to download a fraction of the experiences of cognitive psychologist Philip Rubin, especially his experiences connecting science and policy.

The Long Arm of Criminality

David Canter considers the daily reminders of details of our actions that have been caused by criminality.

Why Don’t Algorithms Agree With Each Other?

David Canter reviews his experience of filling in automated forms online for the same thing but getting very different answers, revealing the value systems built into these supposedly neutral processes.

A Black History Addendum to the American Music Industry

The new editor of the case study series on the music industry discusses the history of Black Americans in the recording industry.

A Behavioral Scientist’s Take on the Dangers of Self-Censorship in Science

The word censorship might bring to mind authoritarian regimes, book-banning, and restrictions on a free press, but Cory Clark, a behavioral scientist at […]

Jonathan Breckon On Knowledge Brokerage and Influencing Policy

Overton spoke with Jonathan Breckon to learn about knowledge brokerage, influencing policy and the potential for technology and data to streamline the research-policy interface.

Research for Social Good Means Addressing Scientific Misconduct

Social Science Space’s sister site, Methods Space, explored the broad topic of Social Good this past October, with guest Interviewee Dr. Benson Hong. Here Janet Salmons and him talk about the Academy of Management Perspectives journal article.

NSF Looks Headed for a Half-Billion Dollar Haircut

Funding for the U.S. National Science Foundation would fall by a half billion dollars in this fiscal year if a proposed budget the House of Representatives’ Appropriations Committee takes effect – the first cut to the agency’s budget in several years.

NSF Responsible Tech Initiative Looking at AI, Biotech and Climate

The U.S. National Science Foundation’s new Responsible Design, Development, and Deployment of Technologies (ReDDDoT) program supports research, implementation, and educational projects for multidisciplinary, multi-sector teams

Digital Transformation Needs Organizational Talent and Leadership Skills to Be Successful

Who drives digital change – the people of the technology? Katharina Gilli explains how her co-authors worked to address that question.

Six Principles for Scientists Seeking Hiring, Promotion, and Tenure

The negative consequences of relying too heavily on metrics to assess research quality are well known, potentially fostering practices harmful to scientific research such as p-hacking, salami science, or selective reporting. To address this systemic problem, Florian Naudet, and collegues present six principles for assessing scientists for hiring, promotion, and tenure.

Book Review: The Oxford Handbook of Creative Industries

Candace Jones, Mark Lorenzen, Jonathan Sapsed , eds.: The Oxford Handbook of Creative Industries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. 576 pp. $170.00, […]

Daniel Kahneman, 1934-2024: The Grandfather of Behavioral Economics

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, whose psychological insights in both the academic and the public spheres revolutionized how we approach economics, has died […]

Canadian Librarians Suggest Secondary Publishing Rights to Improve Public Access to Research

The Canadian Federation of Library Associations recently proposed providing secondary publishing rights to academic authors in Canada.

Webinar: How Can Public Access Advance Equity and Learning?

The U.S. National Science Foundation and the American Association for the Advancement of Science have teamed up present a 90-minute online session examining how to balance public access to federally funded research results with an equitable publishing environment.

Open Access in the Humanities and Social Sciences in Canada: A Conversation

Five organizations representing knowledge networks, research libraries, and publishing platforms joined the Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences to review the present and the future of open access — in policy and in practice – in Canada

A Former Student Reflects on How Daniel Kahneman Changed Our Understanding of Human Nature

Daniel Read argues that one way the late Daniel Kahneman stood apart from other researchers is that his work was driven by a desire not merely to contribute to a research field, but to create new fields.

Four Reasons to Stop Using the Word ‘Populism’

Beyond poor academic practice, the careless use of the word ‘populism’ has also had a deleterious impact on wider public discourse, the authors argue.

The Added Value of Latinx and Black Teachers

As the U.S. Congress debates the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, a new paper in Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences urges lawmakers to focus on provisions aimed at increasing the numbers of black and Latinx teachers.

A Collection: Behavioral Science Insights on Addressing COVID’s Collateral Effects

To help in decisions surrounding the effects and aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the the journal ‘Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences’ offers this collection of articles as a free resource.

Susan Fiske Connects Policy and Research in Print

Psychologist Susan Fiske was the founding editor of the journal Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences. In trying to reach a lay audience with research findings that matter, she counsels stepping a bit outside your academic comfort zone.

Mixed Methods As A Tool To Research Self-Reported Outcomes From Diverse Treatments Among People With Multiple Sclerosis

What does heritage mean to you?

Personal Information Management Strategies in Higher Education

Working Alongside Artificial Intelligence Key Focus at Critical Thinking Bootcamp 2022

SAGE Publishing — the parent of Social Science Space – will hold its Third Annual Critical Thinking Bootcamp on August 9. Leaning more and register here

Watch the Forum: A Turning Point for International Climate Policy

On May 13, the American Academy of Political and Social Science hosted an online seminar, co-sponsored by SAGE Publishing, that featured presentations […]

Event: Living, Working, Dying: Demographic Insights into COVID-19

On Friday, April 23rd, join the Population Association of America and the Association of Population Centers for a virtual congressional briefing. The […]

Connecting Legislators and Researchers, Leads to Policies Based on Scientific Evidence

The author’s team is developing ways to connect policymakers with university-based researchers – and studying what happens when these academics become the trusted sources, rather than those with special interests who stand to gain financially from various initiatives.

Public Policy

Tavneet Suri on Universal Basic Income

Economist Tavneet Suri discusses fieldwork she’s done in handing our cash directly to Kenyans in poor and rural parts of Kenya, and what the generally good news from that work may herald more broadly.

Jane M. Simoni Named New Head of OBSSR

Clinical psychologist Jane M. Simoni has been named to head the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research

Canada’s Federation For Humanities and Social Sciences Welcomes New Board Members

Annie Pilote, dean of the faculty of graduate and postdoctoral studies at the Université Laval, was named chair of the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences at its 2023 virtual annual meeting last month. Members also elected Debra Thompson as a new director on the board.

Britain’s Academy of Social Sciences Names Spring 2024 Fellows

Forty-one leading social scientists have been named to the Spring 2024 cohort of fellows for Britain’s Academy of Social Sciences.

National Academies Looks at How to Reduce Racial Inequality In Criminal Justice System

To address racial and ethnic inequalities in the U.S. criminal justice system, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine just released “Reducing Racial Inequality in Crime and Justice: Science, Practice and Policy.”

Survey Examines Global Status Of Political Science Profession

The ECPR-IPSA World of Political Science Survey 2023 assesses political science scholar’s viewpoints on the global status of the discipline and the challenges it faces, specifically targeting the phenomena of cancel culture, self-censorship and threats to academic freedom of expression.

Report: Latest Academic Freedom Index Sees Global Declines

The latest update of the global Academic Freedom Index finds improvements in only five countries

Analyzing the Impact: Social Media and Mental Health

The social and behavioral sciences supply evidence-based research that enables us to make sense of the shifting online landscape pertaining to mental health. We’ll explore three freely accessible articles (listed below) that give us a fuller picture on how TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and online forums affect mental health.

The Risks Of Using Research-Based Evidence In Policymaking

With research-based evidence increasingly being seen in policy, we should acknowledge that there are risks that the research or ‘evidence’ used isn’t suitable or can be accidentally misused for a variety of reasons.

Surveys Provide Insight Into Three Factors That Encourage Open Data and Science

Over a 10-year period Carol Tenopir of DataONE and her team conducted a global survey of scientists, managers and government workers involved in broad environmental science activities about their willingness to share data and their opinion of the resources available to do so (Tenopir et al., 2011, 2015, 2018, 2020). Comparing the responses over that time shows a general increase in the willingness to share data (and thus engage in Open Science).

Maintaining Anonymity In Double-Blind Peer Review During The Age of Artificial Intelligence

The double-blind review process, adopted by many publishers and funding agencies, plays a vital role in maintaining fairness and unbiasedness by concealing the identities of authors and reviewers. However, in the era of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data, a pressing question arises: can an author’s identity be deduced even from an anonymized paper (in cases where the authors do not advertise their submitted article on social media)?

Hype Terms In Research: Words Exaggerating Results Undermine Findings

The claim that academics hype their research is not news. The use of subjective or emotive words that glamorize, publicize, embellish or exaggerate results and promote the merits of studies has been noted for some time and has drawn criticism from researchers themselves. Some argue hyping practices have reached a level where objectivity has been replaced by sensationalism and manufactured excitement. By exaggerating the importance of findings, writers are seen to undermine the impartiality of science, fuel skepticism and alienate readers.

Five Steps to Protect – and to Hear – Research Participants

Jasper Knight identifies five key issues that underlie working with human subjects in research and which transcend institutional or disciplinary differences.

New Tool Promotes Responsible Hiring, Promotion, and Tenure in Research Institutions

Modern-day approaches to understanding the quality of research and the careers of researchers are often outdated and filled with inequalities. These approaches […]

There’s Something In the Air…But Is It a Virus? Part 1

The historic Hippocrates has become an iconic figure in the creation myths of medicine. What can the body of thought attributed to him tell us about modern responses to COVID?

Alex Edmans on Confirmation Bias

In this Social Science Bites podcast, Edmans, a professor of finance at London Business School and author of the just-released “May Contain Lies: How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases – And What We Can Do About It,” reviews the persistence of confirmation bias even among professors of finance.

Alison Gopnik on Care

Caring makes us human. This is one of the strongest ideas one could infer from the work that developmental psychologist Alison Gopnik is discovering in her work on child development, cognitive economics and caregiving.

Tejendra Pherali on Education and Conflict

Tejendra Pherali, a professor of education, conflict and peace at University College London, researches the intersection of education and conflict around the world.

Gamification as an Effective Instructional Strategy

Gamification—the use of video game elements such as achievements, badges, ranking boards, avatars, adventures, and customized goals in non-game contexts—is certainly not a new thing.

Harnessing the Tide, Not Stemming It: AI, HE and Academic Publishing

Who will use AI-assisted writing tools — and what will they use them for? The short answer, says Katie Metzler, is everyone and for almost every task that involves typing.

Immigration Court’s Active Backlog Surpasses One Million

In the first post from a series of bulletins on public data that social and behavioral scientists might be interested in, Gary Price links to an analysis from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

Webinar Discusses Promoting Your Article

The next in SAGE Publishing’s How to Get Published webinar series focuses on promoting your writing after publication. The free webinar is set for November 16 at 4 p.m. BT/11 a.m. ET/8 a.m. PT.

Webinar Examines Open Access and Author Rights

The next in SAGE Publishing’s How to Get Published webinar series honors International Open Access Week (October 24-30). The free webinar is […]

Ping, Read, Reply, Repeat: Research-Based Tips About Breaking Bad Email Habits

At a time when there are so many concerns being raised about always-on work cultures and our right to disconnect, email is the bane of many of our working lives.

New Dataset Collects Instances of ‘Contentious Politics’ Around the World

The European Research Center is funding the Global Contentious Politics Dataset, or GLOCON, a state-of-the-art automated database curating information on political events — including confrontations, political turbulence, strikes, rallies, and protests

Matchmaking Research to Policy: Introducing Britain’s Areas of Research Interest Database

Kathryn Oliver discusses the recent launch of the United Kingdom’s Areas of Research Interest Database. A new tool that promises to provide a mechanism to link researchers, funders and policymakers more effectively collaboratively and transparently.

Watch The Lecture: The ‘E’ In Science Stands For Equity

According to the National Science Foundation, the percentage of American adults with a great deal of trust in the scientific community dropped […]

Watch a Social Scientist Reflect on the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

“It’s very hard,” explains Sir Lawrence Freedman, “to motivate people when they’re going backwards.”

Dispatches from Social and Behavioral Scientists on COVID

Has the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic impacted how social and behavioral scientists view and conduct research? If so, how exactly? And what are […]

Contemporary Politics Focus of March Webinar Series

This March, the Sage Politics team launches its first Politics Webinar Week. These webinars are free to access and will be delivered by contemporary politics experts —drawn from Sage’s team of authors and editors— who range from practitioners to instructors.

New Thought Leadership Webinar Series Opens with Regional Looks at Research Impact

Research impact will be the focus of a new webinar series from Epigeum, which provides online courses for universities and colleges. The […]

- Impact metrics

- Early Career

- In Memorium

- Curated-Collection Page Links

- Science communication

- True Crime: Insight Into The Human Fascination With The Who-Done-It

- Melissa Kearney on Marriage and Children

- Raffaella Sadun on Effective Management

- Norman Denzin, 1941-2023: The Father of Qualitative Research

Subscribe to our mailing list

Get the latest news from the social and behavioral science community delivered straight to your inbox.

Thanks! Please check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

The Critical Turkey

Essay Writing Hacks for the Social Sciences

What Should Be in a Social Science Essay? Fundamentals and Essential Techniques

This blogpost is also available as a PDF download , so it can be stored on your desktop and used as a checklist before submitting your essay.

The following is a condensed overview of the most important features of social science essay writing. Its aim is to cut through the noise, and focus on the most essential (and important) elements of essay writing. Read it carefully, and use it as a check-list once you have completed your essay.

Before we get into the details, however, be aware: The purpose of writing essays in the social and political sciences is not so much to just demonstrate your knowledge. Rather, it is about applying this knowledge, using it to make a well-informed, well-reasoned, independently-reflected argument that is based on verified (and verifiable) evidence. What should be in an essay, and how you should write it, is all informed by this purpose.

What’s in an Essay?

The main focus of an academic essay, article or book is to address a research or essay question. Therefore, make sure you have read the essay question carefully, think about what aspects of the topic you need to address, and organize the essay accordingly. Your essay should have three parts:

- Introduction

- Provide context to the question. Be specific (not ‘since the dawn of time, social scientists have been arguing…’, but ‘one of the key debates in the study of revolutions revolves around…’, ideally providing references to the key authors of said debate).

- It is almost always a good idea to formulate an argument – an arguable statement – in relation to the essay question (e.g. if the question is ‘Evaluate Weber and Marx’s accounts of capitalism’, an argument could be ‘I am going to argue that Weber is most insightful on X, but Marx is important for Y’). This builds a nice critical element into your essay, your own take on things, going beyond merely describing what others have written.

- Essay plan: Tell the reader about the points you are going to cover, and the order in which you are going to do this (e.g. ‘First, the essay looks at…, second… third…’ etc.). Think of it as a roadmap to the essay.

- Define key concepts as necessary for understanding. Do not use general dictionaries, as they often contain notions that social scientists try to challenge. Use definitions from the readings, and from sociological dictionaries.

- Length: Intro should be between 5 to 10%, and no more than about 10 per cent of the overall word count.

- Main Part / Body

- The structure of the essay body is informed by the research/essay question: What points do you need to include in order to address the question? What sub-questions are there to the big question? Concentrate on the ‘need-to-knows’ rather than the ‘nice-to-knows’ .

- The order in which you arrange these points depends on what makes the most convincing line of argument. This depends on the essay question, but as a rule of thumb you want to build up your argument, from the basics to the more elaborate points, from the weaker to the stronger, from what contradicts your argument to what supports it.

- The different points should be addressed in appropriate depth. Make sure you explain not just what something is, but also how it works, and use examples and illustration.

- There should be a coherent thread running through the essay and connecting the various points to one another and the overall argument. Indicate these connections in strategic places with appropriate signposting. These signpostings should also help you develop your argument as you proceed.

- Excellent essays often raise counter-arguments to the argument presented, and then provide arguments against those counter-arguments. Think about why and how someone might disagree about what you are saying, and how you would respond to them.

- Use peer-reviewed academic sources and present evidence for the points you make, using references, reliable statistics, examples etc. Any opinion you express should be built on reliable evidence and good reasoning.

- What, finally, is your answer to the question? Bring the various strings of the essay together, summarize them briefly in the context of the essay question, and round off by connecting to the bigger discussion that the essay question is part of. It is usually a good idea to have a differentiated conclusion, in which you e.g. agree with a statement to a certain extent or under specific circumstances (and explain which and why), but disagree with some other aspects of it, rather than making undifferentiated black-or-white statements. You can also contextualise your argument with your ideas from the introduction. It is normally not a good idea to introduce new material in the conclusion. You are wrapping up here, and rounding off, not starting new discussions.

- Conclusion should be about, and no longer than, 10 per cent of the overall word count.

Notes on Writing Style

- Find the right balance between formal and informal. Avoid being too informal and conversational on the one hand. But also don’t use overly convoluted and complicated language, as it makes your writing inaccessible, and can lead to a lack of clarity. You may at times encounter academic writing that seems deliberately obscure or overcomplicated, but those are not examples you should try to emulate.

- Clarity and specificity should indeed be a top priority. Are the words you are using expressing what you want to express? Is it clear who specifically is doing what or saying what? Pay attention to this when proofreading the essay. Could someone understand this differently? Avoid ambiguities.

- Key concepts should be clearly defined and used throughout the essay in the way you defined them. Choose the definitions that are most useful for your discussion.

- Avoid hyperbole (don’t do ‘shocking statistics’ or ‘dire consequences’ etc.).

Notes on the Writing Process

- Proofreading: When you are first writing, don’t think of it as the final product, but treat it as a first draft. Go through several drafts until you are happy with it. At a minimum, proofread the entire essay once or twice. Don’t be perfectionist when you start out, as you can always come back and improve on whatever you’ve written.

- Small steps: Focussing on the small, concrete steps of your writing process rather than constantly thinking of the big task at hand will help you feel in control.

- Procrastination: Feeling overwhelmed, as well as being too perfectionist, are among the leading causes for procrastination. The two previous points should therefore help you address this issue as well. Don’t be too harsh on yourself when you do procrastinate – almost everyone does it to some extent .

- Over the years, keep addressing areas you want to improve on, and keep looking for information. Search online, for example ‘how to cite a book chapter in Harvard Sage’, ‘developing an argument’, ‘ using quotations ’, ‘memory techniques’, ‘how to read with speed’, ‘understanding procrastination’, or ‘ what does peer-reviewed mean ’. There is plenty of information, and some seriously good advice out there. See what works for you. Read the feedback you get on your writing, and incorporate it into your next essay.

Final Thoughts

Essay Writing skills are good skills to have in any situation (except maybe in a zombie apocalypse). They will make the studying process easier over time, and hopefully also more fun. But in a wider sense, they are general skills of critical engagement with the world around you, and will help you filter and prioritise the overload of information you are confronted with on an everyday basis. In that sense, they might actually even be helpful in a zombie apocalypse.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

HTML Text What Should Be in a Social Science Essay? Fundamentals and Essential Techniques / The Critical Turkey by blogadmin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Plain text What Should Be in a Social Science Essay? Fundamentals and Essential Techniques by blogadmin @ is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Report this page

To report inappropriate content on this page, please use the form below. Upon receiving your report, we will be in touch as per the Take Down Policy of the service.

Please note that personal data collected through this form is used and stored for the purposes of processing this report and communication with you.

If you are unable to report a concern about content via this form please contact the Service Owner .

1 What are the social sciences?

Learning Objectives for this Chapter

After reading this Chapter, you should be able to:

- understand what the social sciences are, including some fundamental concepts and values,

- understand and apply the concept of ‘phronesis’ to thinking about the purpose and value of the social sciences.

History and philosophy of the social sciences

Some of the earliest written and spoken accounts of human action, values, and the structure of society can be found in Ancient Greek, Islamic, Chinese and indigenous cultures. For example, Ibn Khaldoun , a 14th-century North African philosopher, is considered a pioneer in the field of social sciences. He wrote the book Muqaddimah , which is regarded as the first comprehensive work in the social sciences. It charts an attempt to create a universal history based on studying and explaining the economic, social, and political factors that shape society and discussed the cyclical rise and fall of civilisations. Moreover, indigenous peoples across the world have contributed in various and significant ways to the development of scientific knowledge and practices (e.g., see this recent article by Indigenous scholar, Jesse Popp – How Indigenous knowledge advances modern science and technology ). Indeed, contemporary social science has much to learn from indigenous knowledges and methodologies (e.g., Quinn 2022 ), as well as much reconciling to do in terms of its treatment of indigenous peoples the world over (see Coburn, Moreton-Robinson, Sefa Dei, and Stewart-Harawira, 2013 ).

Nevertheless, the dominant Western European narrative of the achievements of the enlightenment still tends to overlook and discredit much of this knowledge. Additionally, male thinkers have tended to dominate within the Western social sciences, while women have historically been excluded from academic institutions and their perspectives largely omitted from social science history and texts. Therefore, much of the history of the social sciences represent a predominantly white, masculine viewpoint. That is not to say that the concepts and theories developed by these male social scientists should be outright discredited. Nevertheless, in engaging with them we must understand this context; they are not the only voices, nor necessarily the most important. Indeed, it is crucial therefore that the history of the social sciences is continually re-examined through a critical lens, to identify gaps within social scientific knowledge bases and allow space for critical revisions that broaden existing concepts and theories beyond an exclusively masculine, Western-centric perspective. We seek to adopt such an approach throughout this book. However, to critique and question Western social scientific perspectives, we must first understand them.

Social sciences in the Western world

The study of the social sciences, as developed in the Western world, can be said to emerge from the Age of Enlightenment in the late 17th Century. Beginning with René Descartes (1596-1650), both the natural and social sciences developed from the concept of the rational, thinking individual. These early Enlightenment thinkers argued that human beings use reason to understand the world, rather than only referring to religion. Other thinkers around this time such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), M. de Voltaire (1694-1778) and Denis Diderot (1713-1784), began to develop different methodologies to scientifically explain processes in the body, the structure of society, and the limits of human knowledge. It was during this period that the social sciences grew out of moral philosophy, which asks ‘how people ought to live’, and political philosophy, which asks ‘what form societies ought to take’. Rather than only focusing on descriptive scientific questions about ‘how things are’, the social sciences also sought answers to normative questions about ‘how things could be’. This is one of the central differences between the natural sciences and the social sciences. This era of Enlightenment marked an important turning point in history that gave way to further developments in both the natural and social sciences.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is often regarded as one of the most influential philosophers for the development of the social sciences. In his work, Kant develops an epistemology that accounts for the objective validity of knowledge, due to the capacities of the human mind. In other words, how can we as individual people come to know facts about the world that are true for all of us. Social scientists, such as Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) and Max Weber (1864-1920) critically developed the work of Kant to explain social relations between individuals.

Émile Durkheim prioritised the validity of social facts over the values themselves, continuing the tradition of ‘ positivism ‘ (an ontological position that we discuss later in this Chapter). Durkheim argued that there is a distinction between social facts and individual facts. Rather than viewing the structure of the human mind as the basis for knowledge like Kant, Durkheim argued that it is society itself that forms the basis for the social experience of individuals. Social facts should therefore, “be treated as natural objects and can be classified, compared and explained according to the logic of any natural science” (Rose, 1981: 19). Durkheim developed his methodology using analogies to the natural sciences. For example, he borrowed concepts from biology to understand society as a living organism.

TRIGGER WARNING

The following section contains content which may be triggering for certain people. It focuses on the sociology of suicide, including discussion of self-harm and different forms of suicide as it exists within society.

Durkheim and Suicide

Emile Durkheim’s 1879 text ‘Suicide: a Study in Sociology’ is a foundational work for the study of social facts. Durkheim explores the phenomenon of suicide across different time periods, nationalities, religions, genders, and economic groups. Durkheim argues that the problem of suicide can not be explained through purely biological, psychological or environmental means. Suicide must, he concludes, “necessarily depend upon social causes and be in itself a collective phenomenon” (Durkheim 1897: 97). It was and continues to be a work of great impact that demonstrates that, what most would consider an individual act is actually enmeshed in social factors.

In his text, Durkheim identifies some of the different forms suicide can take within society, four of which we discuss below.

Egoistic Suicide

Egoistic suicide is caused by what Durkheim terms “excessive individuation” (Durkheim 1897: 175). A lack of integration within a particular community or society at large leads human beings to feel isolated and disconnected from others. Durkheim argues that “suicide increases with knowledge”(Durkheim 1897: 123). This is not to say that a particular human being kills themselves because of their knowledge; rather it is because of the decline of organised religion that human beings desire knowledge outside of religion. It is thus, for Durkheim the weakening organisation of religion that detaches people from their (religious) community, increasing social isolation. According to Durkheim, the capacity of religion to prevent suicide does not result from a stricter prohibition of self-harm. Religion has the power to prevent someone from committing suicide because it is a community, or a ‘society’ in Durkheim’s words. The collective values of religion increases social integration and is just one example of the importance of community in decreasing rates of suicide. Isolation of individuals, for Durkheim, is a fundamental cause of suicide: “The bond attaching man [sic] to life relaxes because that attaching him [sic] to society is itself slack” (Durkheim 1897: 173).

Altruistic Suicide

Durkheim notes another kind of suicide that stems from “insufficient individuation” (Durkheim 1897: 173). This occurs in social situations where an individual identifies so strongly with their beliefs of a group that they are willing to sacrifice themselves for what they perceive to be the greater good. Examples of altruistic suicide include suicidal sacrifice in certain cultures to honour their particular God, soldiers who go to war and die in honour of their country, or the ancient tradition of Hara-kiri in Japan. As such, Durkheim notes that some people have even refused to consider altruistic suicide a form of self-destruction, because it resembles “some categories of action which we are used to honouring with our respect and even admiration”(Durkheim 1897: 199).

Anomic Suicide

The third kind of suicide Durkheim identifies is termed anomic suicide. This type is the result of the activity of human beings “lacking regulation”, and “the consequent sufferings” that are felt from this situation (Durkheim 1897: 219). Durkheim notes the similarities between egoistic and anomic suicide, however he notes an important distinction: “In egoistic suicide it is deficient in truly collective activity, thus depriving the latter of object and meaning. In anomic suicide, society’s influence is lacking in the basically individual passions, thus leaving them without a check-rein” (Durkheim 1897: 219).

Fatalistic Suicide

There is a fourth type of suicide for Durkheim, one that has more historical meaning than current relevance. Fatalistic suicide is opposed to anomic, and is the result of “excessive regulation, that of persons with futures pitilessly blocked and passions violently choked by oppressive discipline” (Durkheim 1897: 239). These regulations occur during moments of crises, including economic and social upheaval, that destabilise the individual’s sense of meaning. It is the impact of external factors onto the individual, where meaning is thrown to the wind for the individual, that characterises fatalistic suicide.

Durkheim’s sociological study of suicide was a groundbreaking work for social sciences. His methodology, multivariate analysis, provided a way to understand numerous interrelated factors and how they relate to a particular social fact. His findings, particularly the higher suicide rates of Protestants, compared to Jewish and Catholic people, was correlated to the higher rates to individualised consciousness and the lower social control. This study, despite criticisms of the generalisations drawn from the results, has had a remarkable impact on sociology and remains a seminal text for those interested in the social sciences.

Max Weber was also influenced by the work of Kant. Unlike Durkheim, Weber “transformed the paradigm of validity and values into a sociology by giving values priority over validity” (Rose, 1981: 19). Culture is thus understood as a value that structures our understanding of the world. According to Weber, values cannot be spoken about in terms of their truth content. The separation between values and validity means that values can only be discussed in terms of faith rather than scientific reason. For Weber, only when a culture’s underpinning values are defined can facts about the social world be understood.

The philosophy of G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) also greatly shaped the development of the social sciences. As argued by Herbert Marcuse (1941: 251-257), Hegel instigated the shift from abstract philosophy to theories of society. According to Hegel, human beings are not restricted to the pre-existing social order and can understand and change the social world. Our natural ability to reason allows human beings to create theories about our world that are universal and true.

Karl Marx (1818-1883), often regarded as the founder of conflict theory, was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Hegel. For example, Hegel emphasises that labour and alienation are essential characteristics of human experience, and Marx applies this idea more concretely to a material analysis of society, dividing human history along the lines of the forces of production. In other words, Marx understood that labour was divided in capitalist society according to two classes that developed society through a perpetual state of conflict: the working class, or ‘ proletariat’ , and the class of ownership, or ‘ bourgeoisie’ (we talk more about Marx’s conflict theory in Chapter 3).

Overall, the social sciences have a long and complex history, influenced by many different philosophical perspectives. As alluded to earlier, however, any account of the historical beginnings of the social sciences must be understood to be embedded within dominant systems of power, including for example colonisation, patriarchy, and capitalism. Indeed, any history of the social sciences is already situated within a narrative, or ‘discourse’. Maintaining a critical lens will allow for a deeper understanding of the genesis of the social sciences, as well as the important ability to question social scientific approaches, understandings, findings, and methods. It is this disposition that we seek to cultivate throughout this book. After all, as Marx famously wrote, “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.”

Defining Key Terms

Descriptive : A descriptive claim or question seeks to explain how things work, what causes them to work that way, and how things relate to one another.

Normative : A normative claim or question seeks to explain how things ought to work, why they should work a certain way, and what should change for things to work differently.

Labour : For Marx, labour is the natural capacity of human beings to work and create things. Under capitalism, labour primarily produces profits for the ruling class. (Please note, we return to the notion of labour in later chapters, and explore other understandings and definitions of this term.)

Alienation : Workers, separated from the products of their labour and replaceable in the production process, become separated or ‘alienated’ from their creative human essence. (Please also see Chapter 3 for a further explanation of the concept of alienation under Marxism.)

What are the social sciences?

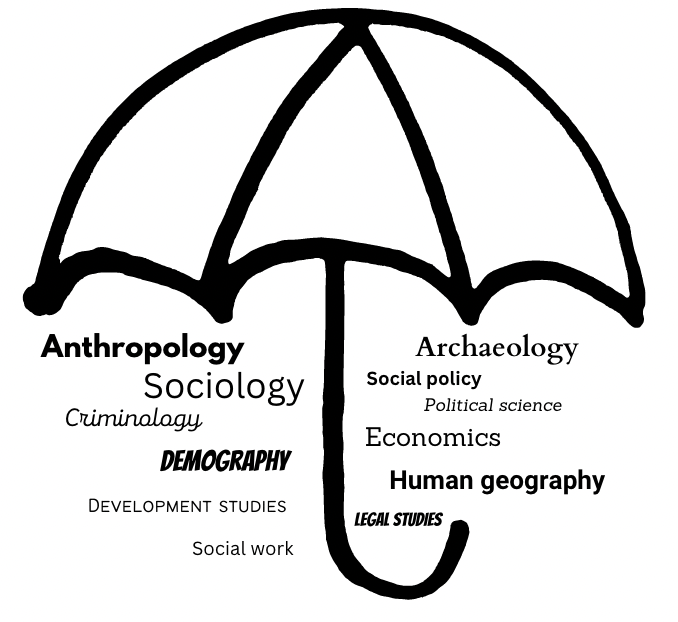

The social sciences are a ‘broad church’, including lots of different disciplinary and sub-disciplinary areas. These include, for example, sociology, anthropology, criminology, archaeology, social policy, human geography, and many more. At their core, they apply the ‘scientific method’ to the analysis of people, societies, power, and social change.

Before we move on, let’s touch briefly on what we mean by the scientific method . At its core, the scientific method is essentially a series of steps that scientists take in order to build and test scientific knowledge. These steps include:

- Observation : Scientists observe the world around them, in order to better understand it.

- Question : Scientists ask ‘research questions’ about how the world works.

- Hypothesis: Scientists come up with ideas or theories about how they think the world works, which they then seek to test through their research.

- Experiment: In experimental research, scientists use a specific experimental design (which includes a control and experimental group) to test hypotheses. This is not always possible or desirable in the social sciences, so social scientists tend to rely on a broader array of methods to collect data that can help them test their hypotheses about the social world.

- Analysis: Scientists use various different approaches to analyse the data they collect; the approach to analysis depends on the kind of data collected, and what questions are being asked of the data.