"> img('logo-tagline', [ 'class'=>'full', 'alt'=>'Words Without Borders Logo' ]); ?> -->

- Get Started

- About WWB Campus

- Translationship: Examining the Creative Process Between Authors & Translators

- Ottaway Award

- In the News

- Submissions

Outdated Browser

For the best experience using our website, we recommend upgrading your browser to a newer version or switching to a supported browser.

More Information

Elena Ferrante’s “The Lost Daughter”

“The hardest things to talk about are the ones we ourselves can't understand.” With that simple and unnerving sentence on the second page of this astonishingly economic novel, author Elena Ferrante is giving readers fair warning: brace yourselves, painful, discomforting truths are about to be revealed in this book about daughters and mothers and the women struggling to be both.

The revelations of Leda, a middle-aged Neapolitan-born divorced mother of two and professor of English literature, are all the more unsettling for the sun-drenched idyllic setting—an Italian coastal town—in which her shadowy secrets are revealed. This is not the bel paese of modern marketing mythology, the one imagined by innumerable vacationers and perpetuated as some paradiso-on-earth in everything from glossy travel magazines to books/films like Under the Tuscan Sun , a never-neverland where the inhabitants are full of life, family and amore. Like her compatriot, the late Sicilian writer Leonardo Sciascia, who, in his novels and short fiction, never hesitated to reveal the moral shortcomings of the inhabitants of his native island or Italian society at large that so willingly accepts the political corruption that is fatte in Italia (made In Italy) as much as Gucci, Maserati and a good Barolo, Ferrante pulls back the layers of escapist fantasy and exposes all those disturbing shadows hiding underneath that Mediterranean sun.

With her grown daughters now living in Canada with her ex-husband, Leda is finally alone and free to dedicate herself to her work. But instead of the expected loneliness, she feels oddly secure. She escapes Florence, where she lives, and heads for a small coastal town for an extended summer holiday of books, sun and the sea. What could be more peaceful?

But on the beach she soon encounters an extended Neapolitan family, loud, boisterous, speaking the dialect of her youth, a “tender language of playfulness and sweet nothings.” It is also the native tongue of the tribal family that she escaped from. She recalls her father and uncles and how “every question sounded on their lips like an order barely disguised…if necessary they could be vulgarly insulting and violent.” At eighteen, she had gone to Florence to study and never looked back “into the black well I came from.” From adolescence onward, she aspired to “a bourgeois decorum, proper Italian, a good life, cultured and reflective.” She is both repelled and entranced by the family and acknowledges that despite all the distance she has put between herself and the city of her origin, she could slip right back into the emotional terrain the Neapolitans inhabit.

In the beginning, Leda merely observes Nina, a young mother, and her daughter Elena and the beloved doll that is the object of the child's affection. Over the course of a few days, their lives become intertwined. When Elena goes missing, Leda finds her. Leda remembers how she herself was lost as a child and her panic when one of her own daughters was lost. But when Nani, Elena's doll, goes missing the novel reaches its emotional epicenter. Leda, it turns out in a moment redolent with psychological implications, has taken it.

The taking of the doll isn't just a momentary lapse of judgment but one that reverberates with dangerous possibilities. Nina's husband, who bears a large scar across his stomach, and his brusque family are described by Gino, who happens to be Nina's lover, in a seemingly innocuous phrase: “They're bad people.” The coded language implies that the family is Camorra, or the Naples equivalent of Sicily's Mafia; they are, in other words, the kind of people who are short on forgiveness and long on memory, especially when it comes to slights and theft.

The doll is an emotional Rosetta stone, unleashing a flood of memories from Leda's own unhappy childhood, including her mother's endless threats to leave and her unhappy adulthood when, as a young mother herself, she sacrificed her own dreams in order to raise a family. She recounts to Nina how she finally followed through on her mother's empty threats and walked out on her own daughters. “I abandoned them when the older was six and the younger four,” she says as if she was recounting a weather report.

This is Ferrante's devastating power as a novelist: she navigates the emotional minefields and unsparingly tallies the cycle of psychological damage among multiple generations of women in Leda's family in straightforward, almost curt language (credit must also be given to translator Ann Goldstein's subtle rendering); the author uses blunt words that slice like a rapier to describe Leda's scars. “Everything in those years seemed to me without remedy, I myself was without remedy,” she recounts. And: “How many damaged, lost things did I have behind me, and yet present, now…”

Ultimately, the doll is returned, but it is too late for forgiveness, Nina has none in her; just as it is too late for Leda to forgive her mother and family, and too late for her own daughters to forgive her trespasses. In the end, Ferrante reminds us that there is no escaping the damage that comes with familial love, intentional or not. Perhaps the best we can do is to acknowledge the damage that has been wrought, as bravely as Ferrante does in this mesmerizing novel.

Joseph V. Tirella is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times , Portfolio.com , Esquire and Vibe .

Joseph V. Tirella

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Maggie Gyllenhaal’s “The Lost Daughter” Is Sluggish, Spotty, and a Major Achievement

By Richard Brody

About a month ago, on my first viewing of “The Lost Daughter,” Maggie Gyllenhaal’s adaptation of the novel by Elena Ferrante, I was sure that something was missing. Though I’d never read the book, the film left me with no doubt that the novel had been written as a first-person narrative, filled with the protagonist’s memories, perceptions, ideas, and directly voiced emotions. That impression, borne out in point of fact, highlights the essential failure of this nonetheless accomplished film—the reduction of a literary source to the framework of a plot. What’s more, this replacement of reflective voice with dramatic depiction reduces the emotion, the psychology, and the intellectual power of the story. It leaves the movie feeling simultaneously too short and too long, a slender tale drawn out at extended length and a vast one crammed into a two-hour span with undue brevity and haste.

The movie (which is streaming on Netflix) starts at night, with a woman in white (Olivia Colman) shuffling along a beach and collapsing on the shore. The rest of the film flashes back from that vague catastrophe. The woman is Leda Caruso, a forty-eight-year-old literature professor from Cambridge, Massachusetts. For a stretch of the summer, she rents a floor at a beach house on the fictional Greek island of Kyopeli, where she plans to use the isolation to get some work done. She parks herself on a chaise longue at seaside, pulls out a book (Dante’s Paradiso), scribbles in her notebook (nothing onscreen long enough to read), and asks a friendly young attendant—an Irish business student of twenty-four named Will (Paul Mescal)—for an ice-cream pop. But the arrival of a big, noisy Greek American family from Queens, with many boisterous young men and active little children, becomes a distraction. There’s an ambient, latent violence to the men’s presence, an intrinsic aggression to the loud-voiced women, and Leda soon comes into conflict with the large clan—but it’s amicably smoothed over by the young matriarch Callie (Dagmara Dominczyk), who apologizes and befriends Leda. The professor’s connection to the family tightens when a toddler in the group—a girl whose mother, Nina (Dakota Johnson), is Callie’s younger sister-in-law—gets lost and Leda, joining the search, finds her.

The strongest effect that the family has on Leda is mnemonic: seeing young mothers with young daughters sparks remembrances of her own earlier years, nearly two decades ago, when her two daughters (now in their twenties) were small children. Extensive flashbacks punctuating much of the film show what her life was like then, as the younger Leda (Jessie Buckley) attempted to cope with the demands of raising children while advancing her academic career; her husband, Joe (Jack Farthing), also an academic, faced similar demands but shunted them onto Leda. In her frustration, Leda left the family, divorced her husband, and didn’t see the children for three years. Now, with the large and lusty family in full view, her attention and memories fix on a single detail: the lost girl is fiercely attached to a doll, as one of Leda’s young daughters was, and as Leda herself was. Leda, seeing the doll abandoned on the beach, steals and hides it, turning it into a sort of fetish—bathing it, dressing it, cuddling with it.

These elements all provide harrowing, fascinating, and moving objects of consciousness without the consciousness that holds them together. The movie’s distillation of subjective memory and elaborate reflection into images is suggested without being achieved, because the directorial strategy holding the drama together is vague and diffuse. Leda’s perspective is conjured in point-of-view shots that evoke perception and immediate emotion: images of the men roughhousing in the sea, of the women tightly enmeshed in the tumult of family lives, and of the lost girl alone in a rocky nook all appear redolent not of a mere detailing of facts but of Leda’s varied responses to the events, to the characters. These instant, volatile responses, however, remain unanchored—they are both dramatically and psychologically insubstantial—and that’s as much a function of Gyllenhaal’s direction as of her screenwriting.

The movie offers an urgent sense of proximity, starting with intense (yet unimaginatively composed) closeups of Leda. (The cinematography is by Hélène Louvart, who has shot such remarkable films as “ Just Anybody ,” “ Beach Rats ,” “ Never Rarely Sometimes Always ,” and “ Happy as Lazzaro .”) But many scenes are composed merely to illustrate events and offer little sense of physical presence and action—even in scenes of crucial physicality, as when Leda takes and hides the doll, an event that the movie leaves ambiguous, as if the decisive moment risked either absurdity or villainy. The artifice of that object’s prominence, and that theft’s centrality to the character of Leda and to the plot, cries out for reality at both ends—physically, with a straightforward and detailed view, as in a crime drama, and psychologically, with reference to the layers of Leda’s experience, memory, and emotion. Instead, the visual and dramatic approximations create a symbol signifying little but the cinematic concept of the literary.

There’s a very strange moment that suggests how drastically Gyllenhaal truncates the character of Leda. When, in one of the flashbacks, the younger Leda tells Joe that she’s leaving, he threatens to consign the children to their grandmother, Leda’s mother. Leda reacts with panic, declaring her childhood a “black shithole,” and also with terror and contempt, reminding Joe that her mother never finished school. In the movie, the remark comes off as obliviously classist—there’s no shortage of loving, smart, and wise people with little formal education—and seems weirdly inconsistent with the portrait of Leda’s temperament that the movie constructs. (Another unconsidered matter of the peculiarities of class is that the Greek Americans may out-money Leda—they rent a grand villa whereas she rents a modest flat—but her conspicuous intellectual refinement is her social capital.) I was simply bewildered by Leda’s hard words about her mother until I learned that, in Ferrante’s novel, the character of Leda is from Naples, that the family on the beach is also Neapolitan and implicitly of the criminal underworld, that Leda fled the harshness of her family and her city’s milieu for her studies and her career, and that the appearance of the family on the beach was no mere general menace of aggression and view of maternity but a specific recollection of the terrors of her own childhood.

In detaching Leda (who says that her family origins are in the English town of Shipley) by ethnicity and experience from the cultural and regional specifics of the perturbing beach family, Gyllenhaal reduces the character and the drama drastically—and, above all, thins out the power of the present-day seaside scenes. The overwhelming impact of seeing, on the beach, the virtual return of one’s own dreadful past is replaced by a generic dismay at the beach family’s aggressive clamor. The film centers the drama of Leda’s current, encumbered solitude on the stresses of her life as a young mother and her leap into independence by separating herself from her children. The movie puts significant dramatic weight on Leda’s relationships with the younger women in the rowdy family: to Callie, who’s forty-two and pregnant with her first child, Leda offers a bracingly candid view of the difficulties of motherhood as a “crushing responsibility.” Her bond with Nina revolves around the doll, until other dramatic complications come to the fore, late in the action. Leda’s relationship with Will (for whom she appears to harbor glimmers of sexual or romantic interest) and with her elderly landlord, Lyle (Ed Harris), who awkwardly flirts with her, are mere teases regarding her states of mind, her desires, her present life. Yet these thinly sketched relationships, seemingly tied to the determining events of the past, become major plot points that suggest the mechanics of script construction instead of dramatic necessity.

Gyllenhaal places the most emotional weight on the story of the young professor and rising scholar whose ambitions are at risk of being thwarted by the demands of motherhood. The present-day story framing it is weakened by the transformation of a novel into the bare bones of a plot that tosses aside the voice, the mental activity, that energizes it. There’s a more audacious adaptation struggling to escape from this one—a movie that would develop those scenes at length, turning the drama of Leda as a young mother into something more than a handful of bluntly causal tethers, and would center the voice that gives the present tense life. Instead, the movie of “The Lost Daughter” falls in-between and does justice to neither period in Leda’s life, nor to the character over all.

Its dramatic shortcuts notwithstanding, “The Lost Daughter” is a major achievement, because it is, in its very essence, a sort of meta-movie: it embodies and signifies a kind of film that is itself lamentably rare. It’s a movie that, in adapting a novel by Ferrante, indicates the grievous lack in the current cinema of dramas that do what is done all the time in literary fiction: consider women’s lives in intimate detail and in the light of wide-ranging, deep-rooted experience. The crucial subject of “The Lost Daughter” is the woeful fact that it’s exceptional, that there is no Elena Ferrante of filmmaking. Whatever the conventions and shortcuts of literary adaptation that the movie reflects, Gyllenhaal has thrown down a gauntlet to filmmakers and producers, to the movie industry at large, and to the future of the art.

New Yorker Favorites

They thought that they’d found the perfect apartment. They weren’t alone .

After high-school football stars were accused of rape, online vigilantes demanded that justice be served .

The world’s oldest temple and the dawn of civilization .

What happened to the whale from “Free Willy.”

It was one of the oldest buildings left downtown. Why not try to save it ?

The religious right’s leading ghostwriter .

A comic strip by Alison Bechdel: the seven-minute semi-sadistic workout .

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Katy Waldman

By Justin Chang

By Burkhard Bilger

By Carrie Battan

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

The Lost Daughter Has a Mysterious Ending. The Book Can Help.

Maggie gyllenhaal’s netflix movie adaptation is quite faithful to elena ferrante’s book, with one major exception..

Elena Ferrante said in a 2018 Guardian column that she would never tell a female director adapting her work to stick to the story as written. “I don’t want to say: you have to stay inside the cage that I constructed,” she wrote. “We’ve been inside the male cage for too long—and now that that cage is collapsing, a woman artist has to be absolutely autonomous.”

It would seem then that Maggie Gyllenhaal, who wrote and directed a new adaptation of Ferrante’s 2006 novel The Lost Daughter for Netflix, had carte blanche to change as much of the source material as she wanted. Yet despite getting the reclusive author’s blessing to break out of the cage, Gyllenhaal’s film stays faithful in many ways to the plot of Ferrante’s book—which makes the ways it deviates from the text all the more interesting. We break it down below.

The New Setting

The plot of Ferrante’s novel remains largely the same on both page and screen: Leda is a literature professor, divorced, with two adult daughters. She decides to spend her summer by the sea in a rented apartment and spends much of her time at the beach, where she encounters a large, brash family. In particular, a young mother, Nina (Dakota Johnson), and her daughter, Elena (Athena Martin), catch Leda’s attention, and we learn more about her own background and experiences as she observes—and eventually interferes with—their lives.

Gyllenhaal’s adaptation stays true to all the book’s major plot points in the present and in flashbacks, down to many of the smallest details, like when Leda finds a cicada in her bed. But the director makes one major, overarching change: She de-Italianizes the story. Ferrante’s novel takes place, as her novels so often do, in southern Italy—in this case, in an unspecified town on the Ionian coast. Leda and the family she observes are both Neapolitan, and cultural differences between different regions of Italy motivate some of the tension; Leda has rejected much of her heritage in favor of a more sophisticated life in Florence, and the family serves as an unwelcome reminder even as she sympathizes with Nina.

In Gyllenhaal’s telling, Leda (played by Olivia Colman in the present day and Jessie Buckley in flashbacks) is now an Englishwoman living in Cambridge, Massachusetts who decides to vacation in Greece. Instead of English literature, her specialty is Italian translation. The family who disturbs her holiday become Greek-Americans from Queens, New York, with some associated name changes (Nina’s sister-in-law, Rosaria, becomes Callisto). Even the locals don’t escape anglicization: Gino, the young beach attendant, becomes Will (Paul Mescal), while Giovanni, the elderly caretaker of Leda’s apartment, becomes Lyle (Ed Harris).

Instead of Italian characters in an Italian setting, the story is now about tourists, expats, and immigrants in a foreign land. Not only are Leda and Nina no longer Italian, they no longer share an ethnic background at all, which lends their shared frustration with motherhood a more universal quality, one that transcends cultures. (It also, it must be said, spares the actors from adopting House of Gucci -esque Italian accents .)

[ Read: Who Has the Best—and Worst—Italian Accent in House of Gucci ? A Dialect Coach on Lady Gaga, Jared Leto, and More. ]

The Changes to the Characters

In addition to some name and ethnicity changes, a few characters have been altered in Gyllenhaal’s telling. Most notable of these is Nina’s husband, described in the book as “a heavy, thickset man, between thirty and forty” with a shaved head and “substantial belly” divided by a deep scar. This is a very different description from Nina’s husband in the film, the much hunkier, tattooed Toni (English actor and model Oliver Jackson-Cohen).

Leda is a little different, too. Ferrante’s novel is written in first person from her perspective, but Gyllenhaal forgoes any kind of voiceover, instead letting Colman’s acting convey her feelings most of the time. However, Leda becomes somewhat chattier in the film, voicing some of her inner monologue from the book to other characters, as when she tells Will about the size of her daughters’ breasts. (While we’re on the subject of breasts, Leda says in the book that she had large breasts when she was younger, then after she gave birth she did not. In the movie she says the opposite, perhaps to account for the size of Colman’s own, erm, ample bosom.)

Despite the change in her background, Leda retains her name, an allusion to the Greek myth (and the Yeats poem ) about the rape of Leda by Zeus. In both stories, she lives in a world in which men, whether in Italy or Greece or the United States or England, act with impunity, while women and mothers in particular suffer psychological wounds—which are later made physical.

Viewers might wonder what to make of the film’s ending, in which Leda, having been stabbed with a hatpin by Nina, crashes her car, stumbles to the beach with a bleeding wound, then answers a phone call from her daughters. When they tell her they thought she was dead since she hadn’t answered their calls, she says, “I’m alive, actually.” She then produces an orange, seemingly from nowhere, as she talks to them, to peel it in one go just as she once did for them. Is she actually dead?

This scene plays out differently in the book—taking place in Leda’s apartment rather than on the beach, for one—and yet it’s not any less ambiguous:

I sat down cautiously on the sofa. Maybe the pin had pierced my side the way a sword pierces the body of a Sufi ascetic, doing no harm. I looked at the hat on the table, the crust of blood on the skin. It was dark. I rose and turned on the light. I started to pack my bags, but moving slowly, as if I were gravely injured. When the suitcases were ready, I dressed, put on my sandals, smoothed my hair. At that point the cell phone rang. I saw Marta’s name, I felt a great contentment, I answered. She and Bianca, in unison, as if they had prepared the sentence and were performing it, exaggerating my Neapolitan cadence, shouted gaily into my ear: “Mamma, what are you doing, why haven’t you called? Won’t you at least let us know if you’re alive or dead?” Deeply moved, I murmured: “I’m dead, but I’m fine.”

The phrasing may be different (“I’m alive” vs. “I’m dead”), but the ambiguity remains. Nina reminds Leda of a younger version of herself, from the time when she left her daughters, but when Nina stabs Leda, Nina rejects the choice Leda made to cheat on her husband and abandon her child. In both versions, the question we are left with is the same: Will Leda be able to recover from the wounds inflicted on her by her younger self, or were they fatal?

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE LOST DAUGHTER

by Elena Ferrante & translated by Ann Goldstein ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 1, 2008

Does little to illuminate a familiar conflict.

In this latest from the pseudonymous Italian Ferrante ( Troubling Love , 2006, etc.), a middle-aged woman spends her summer vacation meditating about motherhood.

Leda was born and raised in Naples, but she didn’t feel happy until she escaped at 18 to study in Florence. For her, Florence is a symbol of culture and refinement, while Naples is loud and crude. Now 47, Leda is a university teacher in Florence, long separated from her husband Gianni, another academic, who emigrated to Toronto; her grown daughters, Bianca and Marta, recently joined him, but they stay in close phone contact with their mother. Leda’s summer rental is near the sea in an unspecified town. On the beach she observes an attractive threesome: A young mother (Nina), her small daughter (Elena) and the girl’s doll, with which the pair play. They are part of a larger group of Neapolitans who are sprawled out on the beach. When Elena disappears, Leda finds her and returns her to her grateful mother, but then steals her doll. What’s the reason for this “opaque action”? Does she want to forge a connection to the family, or tap into her own childhood memories? It’s a puzzle; not an interesting one, but there it sits, an indigestible lump. Far more interesting is Leda’s confession, to these total strangers, that she once abandoned her daughters for three years, leaving them with her overworked husband. What triggered her departure was a London academic conference where she was lionized by a professor, who would become her lover, and felt an intoxicating sense of self. Eventually she realized being a mother was her most significant fulfillment. Freedom versus responsibility: This tension underlies Leda’s behavior and ambivalence toward her daughters, which continues to the present. The young mother Nina is Leda’s sounding-board, but Ferrante fails to integrate Leda’s soul-searching with the problems of the fractious Neapolitan family on the beach.

Pub Date: April 1, 2008

ISBN: 978-1-933372-42-6

Page Count: 160

Publisher: Europa Editions

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2008

FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP

Share your opinion of this book

More by Elena Ferrante

BOOK REVIEW

by Elena Ferrante ; translated by Ann Goldstein

by Elena Ferrante translated by Ann Goldstein

More About This Book

BOOK TO SCREEN

THE NIGHTINGALE

by Kristin Hannah ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 3, 2015

Still, a respectful and absorbing page-turner.

Hannah’s new novel is an homage to the extraordinary courage and endurance of Frenchwomen during World War II.

In 1995, an elderly unnamed widow is moving into an Oregon nursing home on the urging of her controlling son, Julien, a surgeon. This trajectory is interrupted when she receives an invitation to return to France to attend a ceremony honoring passeurs : people who aided the escape of others during the war. Cut to spring, 1940: Viann has said goodbye to husband Antoine, who's off to hold the Maginot line against invading Germans. She returns to tending her small farm, Le Jardin, in the Loire Valley, teaching at the local school and coping with daughter Sophie’s adolescent rebellion. Soon, that world is upended: The Germans march into Paris and refugees flee south, overrunning Viann’s land. Her long-estranged younger sister, Isabelle, who has been kicked out of multiple convent schools, is sent to Le Jardin by Julien, their father in Paris, a drunken, decidedly unpaternal Great War veteran. As the depredations increase in the occupied zone—food rationing, systematic looting, and the billeting of a German officer, Capt. Beck, at Le Jardin—Isabelle’s outspokenness is a liability. She joins the Resistance, volunteering for dangerous duty: shepherding downed Allied airmen across the Pyrenees to Spain. Code-named the Nightingale, Isabelle will rescue many before she's captured. Meanwhile, Viann’s journey from passive to active resistance is less dramatic but no less wrenching. Hannah vividly demonstrates how the Nazis, through starvation, intimidation and barbarity both casual and calculated, demoralized the French, engineering a community collapse that enabled the deportations and deaths of more than 70,000 Jews. Hannah’s proven storytelling skills are ideally suited to depicting such cataclysmic events, but her tendency to sentimentalize undermines the gravitas of this tale.

Pub Date: Feb. 3, 2015

ISBN: 978-0-312-57722-3

Page Count: 448

Publisher: St. Martin's

Review Posted Online: Nov. 19, 2014

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 1, 2014

HISTORICAL FICTION | FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP

More by Kristin Hannah

by Kristin Hannah

SEEN & HEARD

THEN SHE WAS GONE

by Lisa Jewell ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 24, 2018

Dark and unsettling, this novel’s end arrives abruptly even as readers are still moving at a breakneck speed.

Ten years after her teenage daughter went missing, a mother begins a new relationship only to discover she can't truly move on until she answers lingering questions about the past.

Laurel Mack’s life stopped in many ways the day her 15-year-old daughter, Ellie, left the house to study at the library and never returned. She drifted away from her other two children, Hanna and Jake, and eventually she and her husband, Paul, divorced. Ten years later, Ellie’s remains and her backpack are found, though the police are unable to determine the reasons for her disappearance and death. After Ellie’s funeral, Laurel begins a relationship with Floyd, a man she meets in a cafe. She's disarmed by Floyd’s charm, but when she meets his young daughter, Poppy, Laurel is startled by her resemblance to Ellie. As the novel progresses, Laurel becomes increasingly determined to learn what happened to Ellie, especially after discovering an odd connection between Poppy’s mother and her daughter even as her relationship with Floyd is becoming more serious. Jewell’s ( I Found You , 2017, etc.) latest thriller moves at a brisk pace even as she plays with narrative structure: The book is split into three sections, including a first one which alternates chapters between the time of Ellie’s disappearance and the present and a second section that begins as Laurel and Floyd meet. Both of these sections primarily focus on Laurel. In the third section, Jewell alternates narrators and moments in time: The narrator switches to alternating first-person points of view (told by Poppy’s mother and Floyd) interspersed with third-person narration of Ellie’s experiences and Laurel’s discoveries in the present. All of these devices serve to build palpable tension, but the structure also contributes to how deeply disturbing the story becomes. At times, the characters and the emotional core of the events are almost obscured by such quick maneuvering through the weighty plot.

Pub Date: April 24, 2018

ISBN: 978-1-5011-5464-5

Page Count: 368

Publisher: Atria

Review Posted Online: Feb. 5, 2018

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 15, 2018

GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE | SUSPENSE | FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | SUSPENSE

More by Lisa Jewell

by Lisa Jewell

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

The Best Fiction Books » Contemporary Fiction

The lost daughter, by elena ferrante, translated by ann goldstein, recommendations from our site.

“Ferrante gets at something profoundly true about parenthood, that it is both a glorious and a torturous bond. One feels a natural resentment about the demands children place on you—a desire to run away from them and live unencumbered by responsibility—yet also a desire never to be separate from them.” Read more...

The Best Metaphysical Thrillers

Greg Jackson , Novelist

“ The Lost Daughter tells the story of a 50-year-old literature professor named Leda who takes herself on a melancholy beach vacation, where she sees a mother and daughter playing together on the beach. Leda’s own daughters are grown, and she’s struck, instantaneously and illogically, with a kind of jealous attraction to the connection between this mother and daughter. The little girl leaves her doll on the beach, and Leda takes the doll, and watches the child suffer its loss, watches the whole family frantically search for the doll on the beach…..it reminds you that belonging is never an easy thing. Belonging has terrible consequences.” Read more...

The Best Elena Ferrante Books

Other books by Ann Goldstein and Elena Ferrante

The lying life of adults: a novel by elena ferrante, frantumaglia: a writer's journey by elena ferrante, the beach at night by elena ferrante, the days of abandonment by elena ferrante, my brilliant friend: the neapolitan quartet by elena ferrante, our most recommended books, riddley walker by russell hoban, underworld by don delillo, blood meridian by cormac mccarthy, the shining by stephen king, the road by cormac mccarthy, the things they carried by tim o’ brien.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce, please support us by donating a small amount .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Lost Daughter review – Olivia Colman shines in Elena Ferrante missing-kid drama

Maggie Gyllenhaal’s stylish directorial debut, adapted from Ferrante’s novel, is led by a central performance of real star quality

A rich, complex and fascinating performance from Olivia Colman is what gives this movie its piercing power: she has some old-school star quality and screen presence. Colman is the centre of a stylish feature debut from Maggie Gyllenhaal as writer-director, adapting a novel by Elena Ferrante: the result is an absorbingly shaped psychological drama, built around a single traumatising event from which the action metastasises. It takes place partly in the present and also in the lead character’s remembered past, triggered by a calamity that she witnesses and in which she decides, insidiously, to participate. These scenes aren’t simply flashbacks; they have their own relevance and urgency which run alongside the immediate action.

The setting is a Greek island where Leonard Cohen is supposed to have hung out in the 1960s. A British academic arrives on holiday: this is Leda, played by Colman, a Yorkshire-born professor of comparative literature at Harvard, and she has clearly been looking forward to this break for ages, settling almost ecstatically into the vacation apartment into which her bags are carried by the property’s housekeeper Lyle (Ed Harris), an expatriate American who is wizened but virile-looking.

Leda is quite happy to do nothing but hang out on the beach, reading Dante and making notes, or journal musings, in a little book. But then her peace and quiet are disrupted by a crassly loud American family, who show up on the beach, treating it as their own private property, including Nina (Dakota Johnson), the mother of a little girl. She is a very young mother, so young you might assume she is the nanny; and there is also the loud and pushy Callie (Dagmara Dominczyk).

At first, relations are wince-makingly strained between Leda and these arrogant newcomers, but Leda becomes a hero to them when Nina’s little girl goes missing and Leda finds her, with a sixth sense for where the child might be. Yet now this little girl is herself upset by a mini-catastrophe of her own, which strangely echoes the grownups’ recent nightmare: her beloved doll has mysteriously vanished. And it all echoes inside the mind of Leda and her own troubled past, her relationship with her partner and now grownup daughters. Jessie Buckley is outstanding as young Leda, a performance that cleverly complements Colman’s.

What is great about Colman’s performance is that it is always teetering on the brink of some new revelation about Leda: her face is subtly trembling with … what? Tears? Laughter? A scowl of scorn? The initial situation might lead you to expect that Leda is basically the shy, reticent decent person and Nina and Callie and their clan are the boorish villains. But is that true?

As for Leda herself, her own sexual life is a worryingly unstable entity. She flirts with handsome young pool attendant Will (Paul Mescal), shamelessly asks him for dinner and then can’t take it the correct way when he tells her she is beautiful. When Lyle attempts to talk to Leda at the bar one evening, she makes strained conversation and finally has to ask him to leave her in peace to enjoy her supper – and then, perhaps ashamed at her rudeness, and perhaps thinking that she might find Lyle attractive after all, she vampishly adjusts her dress, strolls over to where he is hanging out with his friends and attempts a sultry, flirtatious remark which is so ill-judged that I wanted to hide my face in my hands.

The Lost Daughter has a slightly tame ending: a Nabokovian flourish of violence and aggression that is cancelled (rather implausibly) by something more emollient. But it all hangs together and Olivia Colman achieves a subtle sort of grandeur at the end.

- Peter Bradshaw's film of the week

- Drama films

- Film adaptations

- Olivia Colman

- Dakota Johnson

- Maggie Gyllenhaal

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

‘The Lost Daughter’ Review: ‘Unnatural Mother’ Olivia Colman Makes Amends in This Brilliant but Risky Thriller

In this remarkable directorial debut, Maggie Gyllenhaal challenges conventional thinking about motherhood, delivering her most subversive ideas as subtext.

By Peter Debruge

Peter Debruge

Chief Film Critic

- ‘The Kingdom’ Review: The Daughter of a Corsican Big Shot Practices Her Aim in Cannes Standout 12 hours ago

- ‘Emilia Pérez’ Review: Leading Lady Karla Sofía Gascón Electrifies in Jacques Audiard’s Mexican Redemption Musical 2 days ago

- ‘Universal Language’ Review: Matthew Rankin Channels the Best of Iranian Cinema in Absurdist Canadian Comedy 3 days ago

First a little girl goes missing, then her doll, in “ The Lost Daughter ,” a daring psychological drama in which what should have been an idyllic summer vacation on the Greek island of Spetses instead becomes a kind of overdue emotional workout for Olivia Colman ’s character, Leda, who collapses on the beach, bleeding from her abdomen in the opening scene. How these two disappearances might build to such a dire fate is one of the film’s mysteries, though more compelling is why this woman reacts to the incidents as she does, shocked into confronting her own conduct as a wife and parent many years earlier.

“I’m an unnatural mother,” Leda confesses at one point, saying aloud that which women aren’t typically allowed to admit about motherhood — that such a precious gift can be an unwelcome burden for some, and that by extension, not everyone is cut out for the job — in a film that gives any who may have felt this way a rare sense of being seen. That acknowledgement, jagged and potentially confrontational though it may be, is first-time helmer Maggie Gyllenhaal ’s offering to audiences accustomed to a more conventional depiction of the female experience — and also that of Italian author Elena Ferrante (“My Brilliant Friend”), who first put the unspeakable to paper in the tight but insightful novella from which “The Lost Daughter” was adapted.

Gyllenhaal recognized herself in Ferrante’s words, or so she has said, presumably much as Leda sees herself mirrored in the character of Nina (played by Dakota Johnson), simultaneously the same and unknowably different. As an actor, the “Sherrybaby” star has challenged conventional notions of what a “good mother” can be, but with this film, she delves even deeper into those waters, demonstrating that her instincts run as deep and unease-inducing behind the camera as they do on-screen.

Popular on Variety

It helps that Gyllenhaal — who doesn’t appear in the film but seeds aspects of herself among its female characters — has found two terrific surrogates in Colman and Jessie Buckley , who embody older and younger versions of the lead character, a language scholar who turns up on Spetses for a “working vacation.” Leda possesses the sort of intellect that never rests but is easily distracted, which made it difficult to multitask motherhood with her work as a translator of poetry when her children were young and attention-hungry. (An inspired match, Buckley plays the exasperated Leda in these suffocating flashbacks.)

Now in her late 40s and single, Leda does her best to slip into the laid-back atmosphere of the island, flirting with both the older handyman (Ed Harris) who manages her rental apartment and the handsome bartender (Paul Mescal) down by the beach. Leda likes to think she’s still got it, even if she has no overt intention of following through on either man’s attention.

She’s an amateur people-watcher, and while sunbathing one afternoon, she spots Nina, a stunningly attractive young mother accompanied by a disruptive clan of Mafia-like in-laws. It’s hard to know exactly what Leda might be thinking — that’s part of the film’s power, leaving just enough open for audiences to project their own interpretations. Is it envy or admiration that she feels? But she can’t look away; she’s practically indiscreet in her curiosity, a nosiness Colman intuitively conveys through her body language.

The movie is laced with flashbacks — unresolved guilt trips, really, still sharp enough to lacerate the fingertips when handled — which begin when Leda notices Nina. Something about observing this woman has triggered uncomfortable feelings in Leda, who goes out of her way to avoid small talk. Instead, she snaps briskly at strangers, wrapping her terse replies in a kind of combative barbed wire. All the better to maintain a wary distance, but also a clue that she might not be as strong as she believes.

One afternoon at the beach, instead of ingratiating herself to the family when given the chance, Leda risks upsetting Nina’s in-laws by refusing to surrender her spot. Good for her, Nina thinks. And yet, these people — who bristle with sinister entitlement — are not accustomed to being turned down. It would be unwise to make enemies of them. Then the little girl disappears, and Leda emerges a hero, for a time, by helping to locate her.

But the character’s no angel, as the movie gradually reveals, which makes Gyllenhaal’s choice to cast Colman all the more subversive: There’s something inherently agreeable in the actor’s persona, which reads as cheery and pleasant, whereas this role allows her to explore her inner monster. Even today, women are judged harshly by society for acting selfishly — for putting their careers before their kids, pleasure before partners. When adults give dolls to little girls, it is with the assumption that they will grow up to be responsible mothers. The conditioning begins early, but it doesn’t always stick. That symbolism isn’t lost on Ferrante, nor is it lost in translation by Gyllenhaal.

At the risk of revealing too much about Leda’s past, Peter Sarsgaard (the director’s real-life husband) factors into some of the Buckley scenes, giving Gyllenhaal the chance to show a smoldering, seductive side of the actor never before captured on film. An intense sapiosexual attraction arises, so strong that Leda can still conjure the intensity of it all these years later. As Leda’s memories come to occupy a greater part of the film, it becomes clear that she’s still haunted by the impact of her much-earlier actions.

Through it all, Gyllenhaal assumes an unfussy, practically invisible non-style that conveys the essential (like that missing doll, visible in the background of a key scene) while privileging the performances. Working with French DP Hélène Louvart, she trusts in her ensemble, giving them rich reams of subtext to play, rather than putting words in their mouths, although there are some lines viewers may feel as if they’ve been waiting forever to hear, as when she tells Nina, “Children are a crushing responsibility” — permission to be imperfect, as it were. Even mothers make mistakes.

Reviewed at Netflix screening room, Los Angeles, Aug. 24, 2021. (In Venice, Telluride, New York film festivals.) Running time: 122 MIN.

- Production: (U.S.-Greece) A Netflix (in U.S.), eOne (in U.K.) release of an In the Current, Pie House production, in association with Faliro House Prod. Producers: Osnat Handelsman Keren, Talia Kleinhendler, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Charles Dorfman. Executive producers: David Gilbery, Marlon Vogelgesang, Olivia Colman, Christos V. Konstantakopoulos, Tmira Yardeni.

- Crew: Director, writer: Maggie Gyllenhaal, based on the novel by Elena Ferrante. Camera: Hélène Louvart. Editor: Affonso Goncalves. Music: Dickon Hinchliffe.

- With: Olivia Colman, Jessie Buckley, Dakota Johnson, Ed Harris, Peter Sarsgaard, Dagmara Dominczyk, Paul Mescal, Jack Farthing, Robyn Elwell, Ellie Blake, Oliver Jackson-Cohen, Panos Koronis, Alexandros Mylonas, Alba Rohrwacher, Nikos Poursanidis, Athena Martin.

More From Our Brands

Sexual assault lawsuit against former grammy ceo dismisse, this rare 1969 de tomaso was the marque’s second production car. it’s now up for grabs., big ten reclaims revenue lead after earning $880m in fy23, the best loofahs and body scrubbers, according to dermatologists, tvline items: chuck vet in amish affair, lioness promotion and more, verify it's you, please log in.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy . We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

‘The Lost Daughter’ Review: Gyllenhaal’s Take on Ferrante’s Novel Is So Electric It Feels Born a Movie

Jessica kiang.

- Share on Facebook

- Share to Flipboard

- Share on LinkedIn

- Show more sharing options

- Submit to Reddit

- Post to Tumblr

- Print This Page

- Share on WhatsApp

Editor’s note: This review was originally published at the 2021 Venice Film Festival. Netflix will release it in theaters on Friday, December 17, and streaming on Netflix on Friday, December 31.

When Olivia Colman ‘s Leda stumbles and collapses onto the pebbly sand of a twilit Greek beach in the very opening scene of Maggie Gyllenhaal ‘s uncannily accomplished, indefinably disturbing and deeply affecting directorial debut “ The Lost Daughter ,” she is wearing white. This is not unusual for Leda, nor heavily symbolic; it’s a blouse and skirt, not a wedding dress or a shroud. But as the title appears boldly over her prone form, and Dickon Hinchliffe’s melodic, throwback score first plinks out like the never-resolving piano intro to an old pop song, and if you know your Yeats, there’s a chance you might think of some lines of his which talk about a staggering girl and then go “And how can body, laid in that white rush/But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?”

Yeats’ poem, “Leda and the Swan” — from which we later learn that comparative literature professor Leda got her name — is a retelling of the Greek myth of the rape of the Spartan Queen by Zeus who appeared to her in the guise of a swan. “The Lost Daughter,” based on one of Elena Ferrante’s lesser-known books and so electrically adapted for the screen by Gyllenhaal that it feels like it was born a movie, has almost nothing to do with that story, except perhaps for the way it is a tale of violation clad in language so sensual and peculiar that the telling of it becomes a thing of beauty itself. Gyllenhaal’s film is a story of self-ascribed transgression and of shame buried and turned bitterly inward, and it too, is made with such alertness to the power of cinematic language – particularly that of performance – that even as you feel your stomach slowly drop at the implications of what you’re watching, you cannot break its spreading sinister spell.

The performance in question, it will surprise no one who’s been to the movies in the last five years to hear, is given by Olivia Colman, on whom so many superlatives have already been rightly showered that it’s genuinely hard to think of one that doesn’t sound like a cliché. But her Leda is something quite extraordinary even within her already extraordinary catalogue: it’s difficult to imagine that anyone else would be able to take this impossible role, in all its unlikeliness and unlikeability, in all its witchy unpredictability and completely staid normalcy and make it seem not only plausible but more real for all its contradictions. Leda, a 48-year-old mother of two daughters (Bianca is 25 and Martha is 23, as she constantly telling her new acquaintances), is outwardly the very model of ordinary, respectable, perhaps slightly invisible middle-aged womanhood. She has come on holiday alone but for some work, to this secluded place, which is shot by the brilliant Hélène Louvart in gently jittery handheld, so that its prettiness is merely incidental and its coolness despite the hot sun feels palpable. And for the time being at least, Leda is enjoying her indulgent solitude like a mid-morning Cornetto.

So it’s with the entirely relatable annoyance of anyone who’s ever found a quiet spot on a nice beach only to have a crowd of rowdy kids settle in right next to them, that Leda reacts when her little oasis of calm is invaded. The first voice she hears is that of Callie (Dagmara Dominczyk), the pregnant, strident scion of a dubiously wealthy Queens family who summer here every year in a rented pink villa on the outskirts of their ancestral village. But the first person she really notices is Callie’s sister-in-law, the gorgeous, lissome Nina ( Dakota Johnson ), as she nuzzles her daughter Elena and plays with her in the sparkling surf. Already there is something a little off – too rapt, too attentive – in the way Leda observes Nina. It’s a strange connection that cues the revelation of other weird undercurrents that eddy beneath Leda’s placid surface: her dizzy spells, her sudden stubbornnesses, her cold-then-hot-then-cold reaction to the faint but unmistakable advances made on her by Lyle (Ed Harris) her holiday home’s caretaker, and the friendly flirtations of Will (Paul Mescal) the young student working his summer at the beach bar.

Nina and Leda finally talk after Elena, the first of many lost daughters in “The Lost Daughter” goes missing and Leda finds her. We’ve already had the beginnings of Leda’s larger story in a few flashbacks to the time when her daughters were around Elena’s age and when she herself was Jessie Buckley – who despite a physical dissimilarity that Gyllenhaal makes no crass attempt to hide, has a such a synergy of body language and mannerism with Colman, that their performances became one palimpsest, the lines of one showing faintly through onto the other: Buckley an echo of the past for Colman; Colman a ghost of the future for Buckley. These scenes start off as memories of her closeness to her kids but soon morph into more painful reminiscences about all the times she resented them, especially little Bianca, for demanding more of her than she wanted to give. In one such, in a sequence that would be heavy-handed if Gyllenhaal’s touch wasn’t so assured, Buckley’s Leda reacts angrily when Bianca defaces Leda’s own favorite childhood doll. Seldom has the inherent creepiness of giving little girls miniaturized baby-shaped mannequins on which to mimic motherhood been so evocatively mined as it is here.

But even after some fraught flashbacking has introduced notes of unease, Leda could still be just what she seems to Nina: a not especially interesting but useful ally who sympathizes with Nina’s own frustrations with her kid and her controlling family. But then Leda does an inexplicably perverse thing. Having returned Elena to her family, she steals the doll she earlier saw the little girl bite down on savagely, in response to a fight between her tempestuous parents. This tiny, deeply conflicted act – one that we’re never even sure that Leda herself understands – is the pebble in the shoe, the grit in the eye, the bug on the pillow of the rest of the film, unlocking levels of Leda’s fathomless psychology that are dark and troubling and horribly, awfully recognizable.

In every mother a sliver of ambivalence about motherhood; in every pretty doll’s mouth a worm. “How did it feel, to be away from your daughters?” asks Nina, expecting a reply full of angst and regret. The regret is there but the reply that comes – “It felt amazing,” says Leda – is the more honest because it is so unexpected. This is how Gyllenhaal has, with a blazing certainty that seems borderline miraculous in a first-time filmmaker, engineered “The Lost Daughter” to work, so that even though very little actually happens, the way that things don’t happen is somehow an ongoing, gripping surprise. The tension is born of an uncertainty, in any given situation, over how Leda, so unforgettably embodied by Colman, will behave. The suspense is that of an orange being peeled in a long strip that seems like it must break at any moment. And it will surely strike the rawest of nerves in anyone – mother or not – who staggers through the world with the demeanor of an ordinary decent person, when all the while feeling the thump inside of her strange heart beating where it lies.

“The Lost Daughter” premiered at the 2021 Venice Film Festival. Netflix will release it in theaters on Friday, December 17, and then on Netflix on December 31.

Most Popular

You may also like.

Review: ‘The Lost Daughter’ is quintessential Maggie Gyllenhaal, even though she’s never on screen

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

The Times is committed to reviewing theatrical film releases during the COVID-19 pandemic . Because moviegoing carries risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and local health officials .

It always speaks well of actors’ humility when they make their directorial debut with a film in which they do not star. It speaks well of their gifts, however, when you sense their screen presence in the film anyway: a strength and specificity of personality that survives their absence and colors other actors’ performances. Maggie Gyllenhaal makes just such a debut with her slippery, sinuous, subtly electrifying Elena Ferrante adaptation “The Lost Daughter”: She’s never made a film before, and yet you’d already feel comfortable classifying it as “a Gyllenhaal film,” the way you might name-brand Joanna Hogg or François Ozon — to name two other directors briefly (though not derivatively) reflected in this film’s glinting, angular surfaces.

Gyllenhaal’s restraint in staying off-screen is all the more notable given that Leda, the thorny, inconstant heroine of Ferrante’s 2006 novel, is exactly the kind of character with which she typically excels as an actor. From the sadomasochistic office assistant of “Secretary” to the recovering train wreck of “Sherrybaby” to the obsessive classroom Svengali of “The Kindergarten Teacher,” she specializes in women others might call “difficult,” with inscrutable desires and ill-fitting social graces. Sure enough, that sympathy for difficulty surfaces here in all manner of ways.

Gyllenhaal might well have been superb as Leda, a 40-something literature professor vacationing alone on a balmy Greek island yet unable to find psychological peace. Still, it’s hard to imagine she’d have been better than an extraordinary Olivia Colman, who wears the role as naturally and unfussily as the oversize white linen blouse that is Leda’s default beachwear, reveling in the chance to play a “normal” female protagonist after the stiff, stylized work of playing various queens to Oscar- and Emmy-winning effect.

Note those scare quotes, for there’s nothing especially normal about Leda, a woman who tartly rejects any prescriptive model of what a woman should be. The more time we spend with her, the more complications we see in her reserved, polite, slightly skittish demeanor: a first impression that wouldn’t draw a second glance from most people, in large part because middle-aged women are so scantly studied by society at all. Colman, a born character actor who seems as surprised as anyone that she’s become a headlining star in her 40s, plays her with the wary knowledge of what it’s like not to be looked at, to keep largely secret one’s eccentricities and flashes of brilliance.

Maggie Gyllenhaal is a natural-born director. Netflix gives her the spotlight

With her directorial debut “The Lost Daughter,” Maggie Gyllenhaal is ready for the awards season frenzy. But this time she’s staying behind the camera.

Sept. 14, 2021

Leda’s on her best behavior when she arrives at the pebbly island, projecting an air of mummy affability to Lyle (Ed Harris), the awkwardly flirtatious proprietor of the apartment she’s renting, and Will (Paul Mescal), the young, dreamy resort manager she admires from a slightly sheepish distance. But her spinier attributes emerge when her idyll is crashed by a rowdy extended family of holidaymakers with various squealing children in tow. Her initial hostility toward them is met in kind by queen bee Callie (a revelatory Dagmara Domińczyk), though she grows increasingly fixated on Nina (Dakota Johnson), a young mother who never seems entirely at home in the role. Bleary and sporadically detached from her cherubic daughter, she has more of a kindred spirit in Leda than she realizes.

For Leda, we gradually learn, is what she herself terms an “unnatural mother”: She mentions her two adult daughters when asked, and speaks good-naturedly to them on the phone from time to time, yet long stretches go by when they don’t seem to be on her mind at all. The film’s title is just its first feat of clever wrong-footing in this regard, as an increasingly intricate flashback structure — like the continuous, spiraling skin of the oranges she peeled for her daughters as girls, her one maternal party trick — fills us in on Leda’s history of discomfort and disassociation as a mother.

The younger Leda is remarkably played by Jessie Buckley with flinty defiance and an escalating sense of suffocated mania. If she and Colman resemble each other no more than any two women pulled off the sidewalk, that works slyly to the film’s advantage, as if the exhaustion and trauma of Leda’s youth has yielded an entirely new face. Yet the physical and gestural mirroring between the two actors is quite astonishing: Often, Colman’s distinctive expressions emerge as uncanny flashes and flinches in Buckley’s visage, like a ghost of motherhood future. These are performances that feel duly steered by a director with an empathetic understanding of unusual women and unusual actors alike; Gyllenhaal’s cinematographer, the great and prolific Helene Louvart, jaggedly zeroes in on faces and features with equivalent empathy and fascination.

For a film that contains no explicit violence or violations, “The Lost Daughter” nonetheless feels quiveringly, exhilaratingly close to something taboo. It’s a rare film that dares to question the supposedly inviolable value of motherhood — a phenomenon typically held up as so sacred that any women who don’t feel attuned to it are encouraged to doubt themselves. It’s not at all surprising that Gyllenhaal has arrived as a filmmaker with such a bold, conflicted paean to unorthodox femininity. But it’s thrilling just the same.

'The Lost Daughter'

Rating: R, for sexual content/nudity and language Running time: 2 hours, 2 minutes Playing: In general release Dec. 17; streaming on Netflix Dec. 31

More to Read

What Joan Didion’s broken Hollywood can teach us about our own

April 8, 2024

Review: In ‘Wicked Little Letters,’ the shock value feels about a century too late

March 30, 2024

In ‘Four Daughters,’ a shattered Tunisian family braves obstacles in the eye of the camera

Feb. 13, 2024

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Entertainment & Arts

Steve Buscemi’s alleged attacker is due in court on Thursday to face assault charges

Kevin Costner’s ‘Horizon: An American Saga’ should have been a TV show

May 20, 2024

Company Town

OpenAI pauses ChatGPT voice that sounds like Scarlett Johansson

Review: Was the 1964 Venice Biennale rigged? The documentary ‘Taking Venice’ looks at conspiratorial claims

- Literature & Fiction

- Genre Fiction

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -31% $10.99 $ 10 . 99 FREE delivery Tuesday, May 28 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Very Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $9.06 $ 9 . 06 FREE delivery Tuesday, May 28 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Jenson Books Inc

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

The Lost Daughter: A Novel Paperback – February 1, 2022

Purchase options and add-ons.

NOW A MOTION PICTURE NOMINATED FOR THREE OSCARS—Best Actress, Best Supporting Actress, Best Adapted Screenplay—Directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal and starring Olivia Colman, Jesse Buckley, Paul Mescal, and Dakota Johnson Another penetrating Neapolitan story from New York Times best-selling author of My Brilliant Friend and The Lying Life of Adults Leda, a middle-aged divorcée, is alone for the first time in years after her two adult daughters leave home to live with their father in Toronto. Enjoying an unexpected sense of liberty, she heads to the Ionian coast for a vacation. But she soon finds herself intrigued by Nina, a young mother on the beach, eventually striking up a conversation with her. After Nina confides a dark secret, one seemingly trivial occurrence leads to events that could destroy Nina’s family in this “arresting” novel by the author of the New York Times –bestselling Neapolitan Novels, which have sold millions of copies and been adapted into an HBO series ( Publishers Weekly ). “Although much of the drama takes place in [Leda’s] head, Ferrante’s gift for psychological horror renders it immediate and visceral.” — The New Yorker “Ferrante’s prose is stunningly candid, direct and unforgettable. From simple elements, she builds a powerful tale of hope and regret.” — Publishers Weekly

- Print length 144 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Europa Editions

- Publication date February 1, 2022

- Dimensions 5.25 x 0.5 x 8.25 inches

- ISBN-10 1609457692

- ISBN-13 978-1609457693

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

Editorial Reviews

Praise for The Lost Daughter "Elena Ferrante will blow you away."— Alice Sebold, author of The Lovely Bones "Ferrante can do a woman's interior dialogue like no one else, with a ferocity that is shockingly honest, unnervingly blunt." — Booklist

"Ferrante has blown the lid off tempestuous parent-child relations."— The Seattle Times

"So refined, almost translucent, that it seems about to float away. In the end this piercing novel is not so easily dislodged from the memory."— The Boston Globe

"Ferrante's prose is stunningly candid, direct and unforgettable. From simple elements, she builds a powerful tale of hope and regret."— Publishers Weekly

" The Lost Daughter is a resounding success...It is delicate yet daring, precise yet evanescent: it hurts like a cut, and cures like balm." — La Repubblica " The Lost Daughter is a novel about the female condition: the conflicts that can emerge in the sphere of marriage, the extinction of love and passion, the difficult relationships with children, which both obstruct and assist the free expression of one's feelings and the growth towards maturity.” — La Stampa Praise for Elena Ferrante “Elena Ferrante’s decision to remain biographically unavailable is her greatest gift to readers, and maybe her boldest creative gesture.”— David Kurnick, Public Books “Everyone should read anything with Ferrante’s name on it.”— Eugenia Williamson, The Boston Globe “Ferrante has written about female identity with a heft and sharpness unmatched by anyone since Doris Lessing.”— Elizabeth Lowry, The Wall Street Journal “Ferrante has become Italy’s best known writer. In our era of social media accessibility, shameless self-promotion, and hot young celebrity culture, this is nothing short of astounding.”— Gina Frangello, Electric Literature “Ferrante’s writing seems to say something that hasn’t been said before—it isn’t easy to specify what this is—in a way so compelling its readers forget where they are, abandon friends and disdain sleep.”— Joanna Biggs, The London Review of Books “To disagree over the quality of a Ferrante passage is often to run up against what you cannot answer or digest.”— Jedediah Purdy, The Los Angeles Review of Books

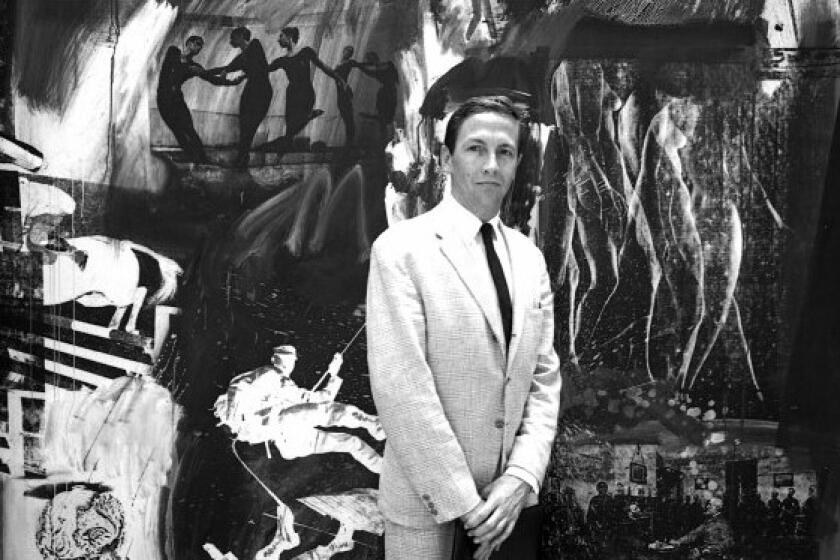

About the Author

Elena Ferrante is the author of The Days of Abandonment (Europa, 2005), Troubling Love (Europa, 2006), and The Lost Daughter (Europa, 2008), now a film directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal and starring Olivia Colman, Dakota Johnson, and Paul Mescal. She is also the author of Incidental Inventions (Europa, 2019), illustrated by Andrea Ucini, Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey (Europa, 2016) and a children’s picture book illustrated by Mara Cerri, The Beach at Night (Europa, 2016). The four volumes known as the “Neapolitan quartet” ( My Brilliant Friend , The Story of a New Name , Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay , and The Story of the Lost Child ) were published by Europa Editions in English between 2012 and 2015. My Brilliant Friend , the HBO series directed by Saverio Costanzo, premiered in 2018. Ferrante’s most recent novel, the New York Times bestselling The Lying Life of Adults , was published in 2020 by Europa Editions.

Ann Goldstein has translated all of Elena Ferrante’s books, including the New York Times bestseller, The Lying Life of Adults , and the international bestseller, My Brilliant Friend . She has been honored with a Guggenheim Fellowship and is the recipient of the PEN Renato Poggioli Translation Award. She lives in New York.

Product details

- Publisher : Europa Editions (February 1, 2022)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 144 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1609457692

- ISBN-13 : 978-1609457693

- Item Weight : 5.6 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.25 x 0.5 x 8.25 inches

- #3,265 in Family Life Fiction (Books)

- #4,042 in Women's Domestic Life Fiction

- #9,576 in Literary Fiction (Books)

About the author

Elena ferrante.

Elena Ferrante is the author of seven novels, including four New York Times bestsellers; The Beach at Night, an illustrated book for children; and, Frantumaglia, a collection of letters, literary essays, and interviews. Her fiction has been translated into over forty languages and been shortlisted for the MAN Booker International Prize. In 2016 she was named one of TIME’s most influential people of the year and the New York Times has described her as “one of the great novelists of our time.” Ferrante was born in Naples.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Review: Maggie Gyllenhaal’s ‘Lost Daughter’ is a stunner

This image released by Netflix shows Jessie Buckley in a scene from “The Lost Daughter.” (Netflix via AP)

This image released by Netflix shows Ed Harris, left, and Olivia Colman in a scene from “The Lost Daughter.” (Yannis Drakoulidis/Netflix via AP)

This image released by Netflix shows Olivia Colman in a scene from “The Lost Daughter.” (Netflix via AP)

This image released by Netflix shows Dakota Johnson in a scene from “The Lost Daughter.” (Netflix via AP)

- Copy Link copied

Motherhood. It’s such a rich subject for art to ponder, you’d think we’d have already seen every kind of mother onscreen.

But actually we haven’t. Sure, we’ve seen good moms, bad moms, crazy moms, selfish moms, generous moms, loving moms, cold moms. But what strikes home so vividly in “The Lost Daughter,” Maggie Gyllenhaal’s gorgeous directorial debut, is how rarely we see a mother who is all those things at once. And yet honestly, what could be more real than that?

On my first viewing of Gyllenhaal’s film, adapted from an Elena Ferrante novel, I was preoccupied with Olivia Colman in yet another blazing performance (is there anything Colman can’t do?), a veritable onion shedding layers as she plays Leda, a prickly yet exceedingly vulnerable 48-year-old academic.