- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 25 November 2008

A case of PTSD presenting with psychotic symptomatology: a case report

- Georgios D Floros 1 ,

- Ioanna Charatsidou 1 &

- Grigorios Lavrentiadis 1

Cases Journal volume 1 , Article number: 352 ( 2008 ) Cite this article

30k Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

A male patient aged 43 presented with psychotic symptomatology after a traumatic event involving accidental mutilation of the fingers. Initial presentation was uncommon although the patient responded well to pharmacotherapy. The theoretical framework, management plan and details of the treatment are presented.

Recent studies have shown that psychotic symptoms can be a hallmark of post-traumatic stress disorder [ 1 , 2 ]. The vast majority of the cases reported concerned war veterans although there were sporadic incidents involving non-combat related trauma (somatic or psychic). There is a biological theoretical framework for the disease [ 3 ] as well as several psychological theories attempting to explain cognitive aspects [ 4 ].

Case presentation

A male patient, aged 43, presented for treatment with complaints tracing back a year ago to a traumatic work-related event involving mutilation of the distal phalanges of his right-hand fingers. Main complaints included mixed hallucinations, irritability, inability to perform everyday tasks and depressive mood. No psychic symptomatology was evident before the event to him or his social milieu.

Mental state examination

The patient was a well-groomed male of short stature, sturdy build and average weight. He was restless but not agitated, with a guarded attitude towards the interviewer. His speech pattern was slow and sparse, his voice low. He described his current mood as 'anxious' without being able to provide with a reason. Patient appeared dysphoric and with blunted affect. He was able to maintain a linear train of thought with no apparent disorganization or irrational connections when expressing himself. Thought content centred on his amputated fingers with a semi-compulsive tendency to gaze to his (gloved) hand. The patient was typically lost in ruminations about his accident with a focus on the precise moment which he experienced as intrusive and affectively charged in a negative and painful way. He could remember wishing for his fingers to re-attach to his hand almost as the accident took place. A trigger in his intrusive thoughts was the painful sensation of neuropathic pain from his half-mutilated fingers, an artefact of surgery.

He denied and thoughts of harming himself and demonstrated no signs of aggression towards others. Hallucinations had a predominantly depressive and ego-dystonic character. He denied any perceptual disturbances at the time of the examination. Their appearance was typically during nighttime especially in the twilight. Initially they were visual only, involving shapes and rocks tumbling down towards the patient, gradually becoming more complex and laden with significance. A mixed visual and tactile hallucination of burning rain came afterwards while in the time of examination a tall stranger clad in black and raiding a tall steed would threaten and ridicule the patient. He scored 21 on a MMSE with trouble in the attention, calculation and recall categories. The patient appeared reliable and candid to the extent of his self-disclosure, gradually opening up to the interviewer but displayed a marked difficulty on describing his emotions and memories of the accident, apparently independent of his conscious will. His judgement was adequate and he had some limited Insight into his difficulties, hesitantly attributing them to his accident.

He was married and a father of three (two boys and a girl aged 7–12) He had no prior medical history for mental or somatic problems and received no medication. He admitted to occasional alcohol consumption although his relatives confirmed that he did not present addiction symptoms. He had some trouble making ends meet for the past five years. Due to rampant unemployment in his hometown, he was periodically employed in various jobs, mostly in the construction sector. One of his children has a congenital deformity, underwent several surgical procedures with mixed results and, before the time of the patient's accident, it was likely that more surgery would be forthcoming. The patient's father was a proud man who worked hard but reportedly was victimized by his brothers, they reaping the benefits of his work in the fields by manipulating his own father. He suffered a nervous breakdown attributed to his low economic status after a failed economic endeavour ending in him being robbed of the profits, seven years before the accident. There was no other relevant family history.

Before the accident the patient was a lively man, heavily involved as a participant and organizer in important local social events from a young age. He was respected by his fellow villagers and felt his involvement as a unique source of pride in an otherwise average existence. Prior to his accident, the patient was repeatedly promised a permanent job as a labourer and fate would have it that his appointment was supposedly approved immediately after the accident only to be subsequently revoked. He viewed himself as an exploited man in his previous jobs, much the same way his father was, while he harboured an extreme bitterness over the unavailability of support for his long-standing problems. His financial status was poor, being in sick-leave from his previous job for the last four months following the accident and hoping to receive some compensation. Although his injuries were considered insufficient for disability pension he could not work to his full capacity since the hand affected was his primary one and he was a manual labourer.

Given that the patient clearly suffered a high level of distress as a result of his hallucinatory experiences he was voluntary admitted to the 2nd Psychiatric Department of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki for further assessment, observation and treatment. A routine blood workup was ordered with no abnormalities. A Rorschach Inkblot Test was administered in order to gain some insight into patient's dynamics, interpersonal relations and underlying personality characteristics while ruling out any malingering or factitious components in the presentation as suggested in Wilson and Keane [ 5 ]. Results pointed to inadequate reality testing with slight disturbances in perception and a difficulty in separating reality from fantasy, leading to mistaken impressions and a tendency to act without forethought in the face of stress. Uncertainty in particular was unbearable and adjustment to a novel environment hard. Cognitive functions (concentration, attention, information processing, executive functions) were impaired possibly due to cognitive inability or neurological disease. Emotion was controlled with a tendency for impulsive behaviour; however there was difficulty in processing and expressing emotions in an adaptive manner. There were distinct patterns of aggression and anger towards others but expressing those patterns was avoided, switching to passivity and denial rather than succumbing to destructive urges or mature competitiveness. Self-esteem was low with feelings of inferiority and inefficiency.

A neurological examination revealed a left VI cranial nerve paresis, reportedly congenital, resulting in diplopia while gazing to the extreme left, which did not significantly affect the patient. The patient had a chronic complaint of occasional vertigo, to which he partly attributed his accident, although the symptoms were not of a persisting nature.

Initial diagnosis at this stage was 'Psychotic disorder NOS' and pharmacological treatment was initiated. An MRI scan of the brain with gadolinium contrast was ordered to rule out any focal neurological lesions. It was performed fifteen days later and revealed no abnormalities.

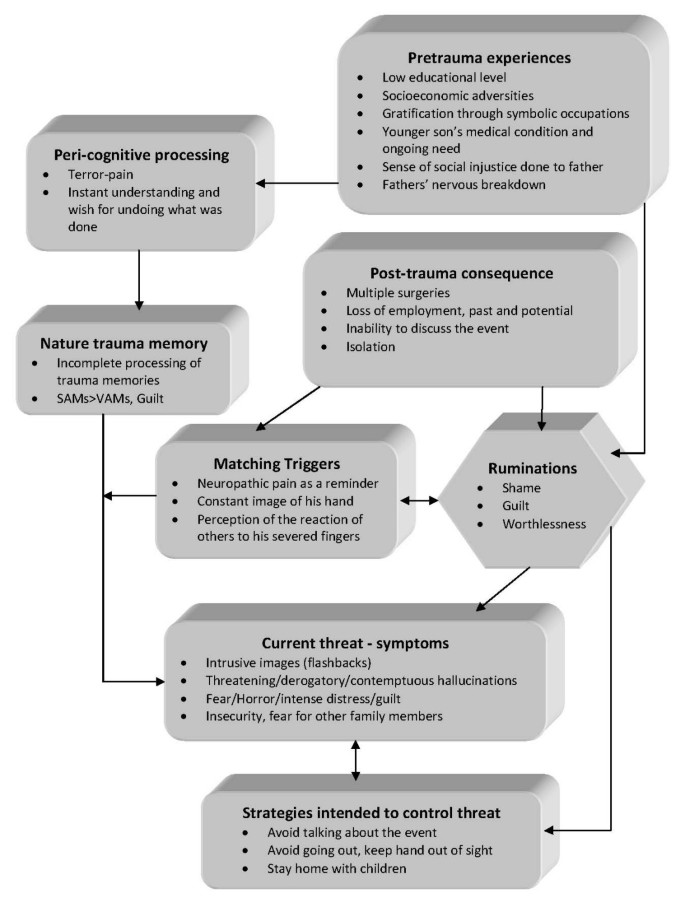

Patient was placed on ziprasidone 40 mg bid and lorazepam 1 mg bid. He reported an immediate improvement but when the attending physician enquired as to the nature of the improvement the patient replied that in his hallucinations he told the tall raider that he now had a tall doctor who would help him and the raider promptly left (sic). Apparently, the random assignment of a strikingly tall physician had an unexpected positive effect. Ziprasidone gradually increased to 80 mg bid within three days with no notable effect to the perceptual disturbances but with the development of akathisia for which biperiden was added, 1 mg tid. Duloxetine was added, 60 mg once-daily, in a hope that it could have a positive effect to his mood but also to this neuropathic pain which was frequent and demoralising. The patient had a tough time accommodating to the hospital milieu, although the grounds were extended and there was plenty of opportunity for walks and other activities. He preferred to stay in bed sometimes in obvious agony and with marked insomnia. He presented a strong fear for the welfare of his children, which he could not reason for. Due to the apparent inability of ziprasidone to make a dent in the psychotic symptomatology, medication was switched to amisulpride 400 mg bid and the patient was given a leave for the weekend to visit his home. On his return an improvement in his symptoms was reported by him and close relatives, although he still had excessive anxiety in the hospital setting. It was decided that his leave was to be extended and the patient would return for evaluation every third day. After three appointments he had a marked improvement, denied any psychotic symptoms while his sleep pattern improved. A good working relationship was established with his physician and the patient was with a schedule of follow-up appointments initially every fifteen days and following two months, every thirty days. His exit diagnosis was "Psychotic disorder Not Otherwise Specified – PTSD". He remained asymptomatic for five months and started making in-roads in a cognitively-oriented psychotherapeutic approach but unfortunately further trouble befell him, his wife losing a baby and his claim to an injury compensation rejected. He experienced a mood loss and duloxetine was increased to 120 mg per day to some positive effect. His status remains tenuous but he retains a strong will to make his appointments and work with his physician. A case conceptualization following a cognitive framework [ 6 ] is presented in Figure 1 .

Case formulation – (Persistent PTSD, adapted from Ehlers and Clark [ 6 ] ) . Case formulation following the persistent PTSD model of Ehlers and Clark [ 6 ]. It is suggested that the patient is processing the traumatic information in a way which a sense of immediate threat is perpetuated through negative appraisals of trauma or its consequences and through the nature of the traumatic experience itself. Peri-traumatic influences that operate at encoding, affect the nature of the trauma memory. The memory of the event is poorly elaborated, not given a complete context in time and place, and inadequately integrated into the general database of autobiographical knowledge. Triggers and ruminations serve to re-enact the traumatic information while symptoms and maladaptive coping strategies form a vicious circle. Memories are encoded in the SAM rather than the VAM system, thus preventing cognitive re-appraisal and eventual overcoming of traumatic experience [ 4 ].

The value of a specialized formulation is made clear in complex cases as this one. There is a relationship between the pre-existing cognitive schemas of the individual, thought patterns emerging after the traumatic event and biological triggers. This relationship, best described as a maladaptive cognitive processing style, culminates into feelings of shame, guilt and worthlessness which are unrelated to similar feelings, which emerge during trauma recollection, but nonetheless acts in a positive feedback loop to enhance symptom severity and keep the subject in a constant state of psychotic turmoil. Its central role is addressed in our case formulation under the heading "ruminations" which best describes its ongoing and unrelenting character. The "what if" character of those ruminations may serve as an escape through fantasy from an unbearably stressful cognition. Past experience is relived as current threat and the maladaptive coping strategies serve as negative re-enforcers, perpetuating the emotional suffering.

The psychosocial element in this case report, the patient's involvement with a highly symbolic activity, demonstrates the importance of individualising the case formulation. Apparently the patient had a chronic difficulty in expressing his emotions and integrating into his social surroundings, a difficulty counter-balanced somewhat with his involvement in the local social events which gave him not only a creative way out from any emotional impasse but also status and recognition. His perceived inability to continue with his symbolic activities was not only an indicator of the severity of his troubles but also a stressor in its own right.

Complex cases of PTSD presenting with hallucinatory experiences can be effectively treated with pharmacotherapy and supportive psychotherapy provided a good doctor-patient relationship is established and adverse medication effects rapidly dealt with. A cognitive framework and a Rorschach test can be valuable in deepening the understanding of individuals and obtaining a personalized view of their functioning and character dynamics. A biopsychosocial approach is essential in integrating all aspects of the patients' history in a meaningful way in order to provide adequate help.

Patient's perspective

"My life situation can't seem to get any better. I haven't had any support from anyone in all my life. Leaving home to go anywhere nowadays is hard and I can't seem to be able to stay anyplace else for a long time either. Just getting to the hospital [where the follow-up appointments are held] makes me very nervous, especially the minute I walk in. Can't seem to stay in place at all, just keep pacing while waiting for my appointment. I am only able to open up somewhat to my doctor, whom I thank for his support. Staying in hospital was close to impossible; I was very stressed and particularly concerned for my children, not being able to be close to them. I still need to have them near-by. Getting the MRI scan was also a stressful experience, confined in a small space with all that noise for so long. I succeeded only after getting extra medication.

I hope that things will get better. I don't trust anyone for any help any more; they should have helped me earlier."

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

stands for 'Post Traumatic Stress Disorder'

for 'Verbally Accessible Memory'

for 'Situationally Accessible Memory'

Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, Braff DL: Positive symptoms of psychosis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1996, 39: 839-844. 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00314-2.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Seedat S, Stein MB, Oosthuizen PP, Emsley RA, Stein DJ: Linking Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Psychosis: A Look at Epidemiology, Phenomenology, and Treatment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003, 191: 675-10.1097/01.nmd.0000092177.97317.26.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Nutt DJ: The psychobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000, 61: 24-29.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brewin CR, Holmes EA: Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003, 23: 339-376. 10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00033-3.

Wilson JP, Keane TM: Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. 2004, The Guilford Press

Google Scholar

Ehlers A, Clark DM: A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000, 38: 319-345. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable support and direction offered by the department's chair, Professor Ioannis Giouzepas who places the utmost importance in creating a suitable therapeutic environment for our patients and a superb learning environment for the SHO's and registrars in his department.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

2nd Department of Psychiatry, Psychiatric Hospital of Thessaloniki, 196 Langada str., 564 29, Thessaloniki, Greece

Georgios D Floros, Ioanna Charatsidou & Grigorios Lavrentiadis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Georgios D Floros .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GF was the attending SHO and the major contributor in writing the manuscript. IC performed the psychological evaluation and Rorschach testing and interpretation. GL provided valuable guidance in diagnosis and handling of the patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Floros, G.D., Charatsidou, I. & Lavrentiadis, G. A case of PTSD presenting with psychotic symptomatology: a case report. Cases Journal 1 , 352 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-352

Download citation

Received : 12 September 2008

Accepted : 25 November 2008

Published : 25 November 2008

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-1-352

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Ziprasidone

- Psychotic Disorder

- Amisulpride

- Hallucinatory Experience

Cases Journal

ISSN: 1757-1626

CBT Case Studies

Case Study: CBT Treatment – Abby

Case Study: CBT Treatment – Abby Abby witnessed the suicide of a stranger and went on to develop PTSD along with enormous amounts of guilt.

Case Study: CBT Treatment – Holly

Case Study: CBT Treatment – Holly Holly developed PTSD after seeing her Dad who received fatal crush injuries. Following intense flashbacks and intrusive memories, she

Case Study: CBT Treatment – Darren

Case Study: CBT Treatment – Darren Darren lived with PTSD for 8 years before he opened up to his wife about how he was feeling

Hello! Did you find this information useful?

Please consider supporting ptsd uk with a donation to enable us to provide more information & resources to help us to support everyone affected by ptsd, no matter the trauma that caused it, ptsd uk blog.

You’ll find up-to-date news, research and information here along with some great tips to ease your PTSD in our blog.

Rebellious Rebirth – Oran: Guest Blog

Rebellious Rebirth – Oran: Guest Blog In this moving guest blog, PTSD UK Supporter Oran shares her personal story after a traumatic event brought childhood traumas to the surface. Dealing with Complex PTSD, Oran found solace in grounding techniques and

Ralph Fiennes – Trigger Warnings Response

Guest Blog: Response to Ralph Fiennes – Trigger warnings in theatres This thought-provoking article has been written for PTSD UK by one of our supporters, Alex C, and addresses Ralph Fiennes’ recent remarks on trigger warnings in Theatre. Alex sheds

Please don’t tell me I’m brave

Guest Blog: Living With PTSD – Please don’t tell me I’m brave ‘Adapting to living in the wake of trauma can mean maybe you aren’t ready to hear positive affirmations, and that’s ok too.’ and at PTSD UK, we wholeheartedly

Emotional Flashbacks – Rachel

Emotional Flashbacks: Putting Words to a Lifetime of Confusing Feelings PTSD UK was founded with the desire to do what was possible to make sure nobody ever felt as alone, isolated or helpless as our Founder did in the midst

Guest Blog: Calming the ‘riot’ in my head

Guest Blog: ‘Calming the riot’ in my head: Anna In our collective journey to navigate the complexities of PTSD and C-PTSD, finding peace and space within the internal turbulence is vital. In this insightful guest blog, author Anna sheds light

Morning Mile March Challenge

events | walk PTSD UK’s Morning Mile March Challenge Sign up now PTSD UK’s Morning Mile March Challenge The challenge We all know ‘exercise is good for you’, and even a small amount can make a big difference. There are

Treatments for PTSD

It is possible for PTSD to be successfully treated many years after the traumatic event occurred, which means it is never too late to seek help. For some, the first step may be watchful waiting, then exploring therapeutic options such as individual or group therapy – but the main treatment options in the UK are psychological treatments such as Eye Movement Desensitisation Reprogramming (EMDR) and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).

Traumatic events can be very difficult to come to terms with, but confronting and understanding your feelings and seeking professional help is often the only way of effectively treating PTSD. You can find out more in the links below, or here .

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Is this actually PTSD? Clinicians divided over redefining borderline personality disorder

Some have argued BPD should be reclassified as a trauma disorder, maintaining those diagnosed are typically women with abuse in their past

- Get our morning and afternoon news emails , free app or daily news podcast

When Prof Andrew Chanen was a trainee psychiatrist in 1993, patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) who had self-harmed were “vilified” and “treated appallingly”.

“There was this myth that somehow they were indestructible,” he says. Despite what his teachers told him, “most were dead by the end of my training”.

More than three decades later, Chanen is the chief of clinical practice and head of personality disorder research at Orygen, the National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health at the University of Melbourne, and he says BPD remains the most stigmatised and discriminated against mental health disorder in Australia and internationally.

Overwhelmingly diagnosed in women , BPD is characterised by difficulty managing emotions, rapid mood changes, self-harm often accompanied by suicidal thoughts, and an unstable self image.

Some Australian clinicians are calling for BPD to be recognised as a trauma disorder rather than a personality disorder, arguing this would lead to better treatment and outcomes.

The argument for rethinking BPD

American psychoanalyst Adolph Stern introduced the word “borderline” to psychiatric terminology in 1938, using it to describe a group of patients who fitted neither the neurotic nor the psychotic diagnostic categories.

Several studies have shown BPD is associated with child abuse and neglect more than any other personality disorders, but the rates can vary from as high as 90% to as low as 30% . An analysis of 97 studies found 71.1% of people who were diagnosed with the condition reported at least one traumatic childhood experience.

Dr Karen Williams, who runs New South Wales’s Ramsay Clinic Thirroul – Australia’s first women-only trauma hospital – believes BPD “is a gendered diagnosis that is given to women who have got histories of abuse, whereas when we see a man come back from a traumatic event, we [say] he’s got PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]”.

“There is no symptom that a borderline personality disordered person has that a PTSD patient doesn’t also have.”

Williams says it often takes several sessions before she can uncover a patient’s abuse. The response of dissociation and forgetting trauma is very common, she says. Also, not all patients recognise their experiences as trauma.

Despite there being no clinical difference between PTSD and BPD, Williams says the clinical response varies markedly. PTSD, particularly among veterans, is treated with sympathy, while women with the diagnosis of BDP are considered “difficult”.

Williams prefers the term “complex post-traumatic stress disorder” to BPD, as does Prof Jayashri Kulkarni, the director of the Monash Alfred Psychiatry Research Centre. Kulkarni says the BPD label implies the behaviour is part of a personality style. There’s an implied “stern moralistic approach” that these people should just be able to control themselves – and that attitude contributes to stigma.

But she says the more she has researched BPD, “the more obvious it seems the women and the men who have been labelled with this condition often have dreadful early life trauma”.

“I really think this is injustice, to say to somebody who’s gone through hell in their early life and onwards, that they’ve got a significant flaw of their inner core.”

The case for the term personality disorder

To Chanen, the term “personality disorder” is useful because it captures the identity and relationship difficulties he says are at the heart of the issue.

He points to a national study of childhood maltreatment published in 2023 which showed nearly two-thirds of the population experience some form of childhood adversity. Despite that, BPD is comparatively rare, occurring in only 1% to 3% of the population.

“There’s something important going on in each individual that interacts with the experience of adversity. While that interaction might give rise to borderline personality disorder, it might also give rise to another disorder, such as depression, or no mental disorder,” he says.

“That’s not to say that the adversity is unimportant, but it’s not inevitable that a person will develop a mental disorder, and certainly not inevitable that they will develop borderline personality disorder.”

Chanen believes any reductionist arguments about causes are “oversimplified, wrong and unfortunately harmful for people living with personality disorder”. He believes the debate around re-naming the disorder as complex PTSD is “not really supported by the science and weakens the moral argument for respect, dignity and equality of access to effective services”.

Chanen is concerned a name change may have the unintended consequence of invalidating the experiences of patients who have not experienced trauma, or prompt clinicians to assume that trauma is present without any evidence. Instead, he believes early intervention is key.

An associate professor at the University of Sydney, Loyola McLean, who identifies as a Yamatji woman, says of the divided opinions within her profession: “It could well be that we’re talking about two halves of the same whole.

“I think we’ve got to keep an open mind that this adverse experience may be contributing, triggering, and for some people will have a causal element,” says McLean, who is a consultation-liaison psychiatrist and psychotherapist.

“Trauma – in particular early trauma, because that’s where the body and brain are really developing – we know that it’s such a huge risk factor for downstream health problems across the spectrum of health problems.”

The physical and the psychological are deeply connected , she says, but “the whole of the western world is still suffering from a kind of a Cartesian divide”.

A shifting approach

The discussion about using BPD or complex post-traumatic stress disorder is about more than words – according to Kulkarni, it changes the whole direction and focus for treatment.

Historically, treatment for BPD has relied upon antidepressants to treat low mood and antipsychotics for paranoid thinking, but it has not addressed underlying cognitive symptoms such as difficulty managing emotions, a disturbed sense of identity, disturbed relationships and impulsivity.

Those symptoms tend to be treated with psychosocial approaches, such as dialectical behaviour therapy, mentalisation-based treatment and high quality care.

Kulkarni and Dr Eveline Mu at Monash Alfred Psychiatry Research Centre are running clinical trials for new drugs to target the neurochemistry they believe drives the symptoms of BPD/complex post-traumatic stress disorder.

The effects of trauma on the body’s stress levels mean the glutamate system – the primary neurotransmitters of the nervous system – is in overdrive, Mu says. Her theory is that this drives cognitive dysfunction.

Since it began in 2022, 200 people have participated in the randomised controlled double blinded clinical trial of memantine, a drug that the regulator has approved for treatment of Alzheimer’s patients, and which blocks the body’s glutamate receptors.

Williams’ women’s-only trauma hospital is also examining new ways of responding to those with acute symptoms. She says the only place where acutely suicidal patients can go are mixed-gender rooms in hospital psychiatric wards , which have no locks and can lack supervision of male patients who are often psychotic, drunk and detoxing. Sexual assault is often rife in such wards.

It’s an environment that exacerbates symptoms, she says.

By contrast, the three-week program her patients undergo involves exercise, self-care, and education about healthy relationships.

“Almost all the time, they don’t just have trauma from their childhood, but they’ve still got it now,” Williams says. “We know that people who have been abused tend to end up in abusive relationships again, because they have such little self value and they don’t know that they deserve to be treated better.”

The hospital’s beds are constantly full with patients who can afford private treatment, with some even coming from interstate. Only one of the hospital’s 40 beds is publicly funded.

Williams says her program has improved the quality of life of her patients, with many able to take on full-time work or go back to study. “Many of them have said: ‘I want to be a nurse, I want to come back and work here.’”

Kulkarni says one of the other new solutions is to get rid of the label. “It’s hurting people … Taking a new look offers us new compassion and new understanding.”

This article was amended on 12 May 2024 to correct the year in which Prof Andrew Chanen was a trainee psychiatrist. It was 1993, not 1983.

In Australia, support is available at Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636, Lifeline on 13 11 14, and at MensLine on 1300 789 978.

- Mental health

- mental health challenges

Most viewed

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Evid Based Complement Alternat Med

- v.2(4); 2005 Dec

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Evidence-Based Research for the Third Millennium

Javier iribarren.

3 David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Paolo Prolo

1 UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2 Psychoneuroimmunology Group, Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA

Negoita Neagos

Francesco chiappelli.

The online version of this article has been published under an open access model. Users are entitled to use, reproduce, disseminate, or display the open access version of this article for non-commercial purposes provided that: the original authorship is properly and fully attributed; the Journal and Oxford University Press are attributed as the original place of publication with the correct citation details given; if an article is subsequently reproduced or disseminated not in its entirety but only in part or as a derivative work this must be clearly indicated. For commercial re-use, please contact [email protected]

The stress that results from traumatic events precipitates a spectrum of psycho-emotional and physiopathological outcomes. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric disorder that results from the experience or witnessing of traumatic or life-threatening events. PTSD has profound psychobiological correlates, which can impair the person's daily life and be life threatening. In light of current events (e.g. extended combat, terrorism, exposure to certain environmental toxins), a sharp rise in patients with PTSD diagnosis is expected in the next decade. PTSD is a serious public health concern, which compels the search for novel paradigms and theoretical models to deepen the understanding of the condition and to develop new and improved modes of treatment intervention. We review the current knowledge of PTSD and introduce the role of allostasis as a new perspective in fundamental PTSD research. We discuss the domain of evidence-based research in medicine, particularly in the context of complementary medical intervention for patients with PTSD. We present arguments in support of the notion that the future of clinical and translational research in PTSD lies in the systematic evaluation of the research evidence in treatment intervention in order to insure the most effective and efficacious treatment for the benefit of the patient.

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorders.

The twenty-first century rose in a ray of hope. The belief was commonly held that an age of worldwide prosperity was beginning with the new millennium. Only a few years ago, people spoke of peace. Today, the general trend in many populations across the globe is fear and anxiety about self and neighbor. Socio-political events have cast a shadow of uneasiness about one's own security and that of significant others at a personal as well as a societal level. (Case in point is Greg, a businessman from Southern California, who happened to be on a business trip in New York city scheduled for September 10–12, 2001. Following the 9/11 attack, which he barely escaped, he immediately attempted to contact his family in the Southland and to leave New York city. He was on the first plane out: but the plane never took off, instead it was boarded by the New York city SWAT team who, at gun point, arrested a passenger seated four seats in front of Greg's. Greg then drove at night to Philadelphia, where he was eventually able to board a plane and return to his anxious family. To this day, Greg does not fly as often as before, is reticent to fly to the east coast and will not return to do business in New York city. His Type II diabetes has considerably worsened.)

Traumatic events are profoundly stressful. The stress that results from traumatic events precipitates a spectrum of psycho-emotional and physiopathological outcomes. In its gravest form, this response is diagnosed as a psychiatric disorder consequential to the experience of traumatic events.

Post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, is the psychiatric disorder that can result from the experience or witnessing of traumatic or life-threatening events such as terrorist attack, violent crime and abuse, military combat, natural disasters, serious accidents or violent personal assaults. Exposure to environmental toxins (e.g. Agent orange, electromagnetic radiation) may result in immune symptoms akin to PTSD in many susceptible patients ( 1 , 2 ).

Subjects with PTSD often relive the experience through nightmares and flashbacks. They report difficulty in sleeping. Their behavior becomes increasingly detached or estranged and is frequently aggravated by related disorders such as depression, substance abuse and problems of memory and cognition. The disorder soon leads to impairment of the ability to function in social or family life, which more often than not results in occupational instability, marital problems and divorces, family discord and difficulties in parenting. The disorder can be severe enough and last long enough to impair the person's daily life and, in the extreme, lead the patient to suicidal tendencies. PTSD is marked by clear biological changes, in addition to the psychological symptoms noted above, and is consequently complicated by a variety of other problems of physical and mental health.

PTSD—A Brief History

Whereas the terminology of PTSD arose relatively soon following the Vietnam conflict, the observation that traumatic events can lead to this plethora of psychobiological manifestations is not new. During the Civil War, a PTSD-like disorder was referred to as the ‘Da Costa's Syndrome’ ( 3 ), from the American internist Jacob Mendez Da Costa (1833–1900; Civil War duty: military hospital in Philadelphia).

The syndrome was first described by ABR Myers (1838–1921) in 1870 as combining effort fatigue, dyspnea, a sighing respiration, palpitation, sweating, tremor, an aching sensation in the left pericardium, utter fatigue, an exaggeration of symptoms upon efforts and occasionally complete syncope. It was noted that the syndrome resembled more closely an abandonment to emotion and fear, rather than the ‘effort’ that normal subjects engage to overcome challenges ( 4 ). This classic observation pertains to what we now know of allostasis, as we discuss below. Da Costa reported in 1871 that the disorder is most commonly seen in soldiers during time of stress, especially when fear was involved ( 3 ). The syndrome became increasingly observed during the Civil War and during World War I.

PTSD in the US Population Today

The National Center for PTSD (US Department of Veterans Affairs) made public estimates that whereas the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in the US population was 5% in men and 10% in women in the mid-to-late 1990s, the prevalence of PTSD among Vietnam veterans at this same time was at 15.2%. About 30% of the men and women who have spent time in more recent war zones experience PTSD.

Whereas the onset and progression of PTSD is characteristic for every individual subject, data suggest that most people who are exposed to a traumatic, stressful event will exhibit early symptoms of PTSD in the days and weeks following exposure. Available data from the National Center for PTSD suggest that ∼8% of men and 20% of women go on to develop PTSD and ∼30% of these individuals develop a chronic form that persists throughout their lifetimes. Complex PTSD, which is also referred to as ‘disorder of extreme stress’, results from exposure to prolonged traumatic circumstances, such as the year-on end threat of insurgent attacks among our military personnel currently in active deployment.

The National Center for PTSD also estimates that under normal and usual socio-political conditions 8% of the US population will experience PTSD at some point in their lives, with women (10.4%) twice as likely as men (5%) to develop PTSD. At the beginning of the millennium, it was estimated that 5–6 million US adults suffered from PTSD. Because of the traumatic developments of recent years, and of ongoing turmoil worldwide, it is possible and even probable that the incidence of PTSD will sharply increase within the next decade and that it may become one among the most significant public health concerns of this new century. This threat is all the more serious considering the fact that PTSD symptoms seldom disappear completely; recovery from PTSD is a lengthy, ongoing, gradual and costly process, which is often hampered by continuing reaction to memories. Treatment usually aims at reducing reactions and to diminishing the acuity of the reactions. Treatments also seek to increase the subject's ability to manage trauma-related emotions and to greater confidence in coping abilities.

Focus of this Review

This work discusses our current understanding about PTSD. It explores current developments in stress research and discusses its applications and implication to the complex psychobiological prognosis of PTSD. The work concludes by presenting a view into the future of PTSD treatment from the perspective of evidence-based medicine, which many regard as the break-open research of the next decades—systematic and critical research on research to establish and determine what is the best available evidence for treatment for the patients. Indeed, this will be particularly true in the case of subjects with PTSD, if the austere predictions of a sharp rise in prevalence consequential to most recent terrorist and war events worldwide that involve US soldiers and civilians prove true.

Current Views on PTSD

There are different psychiatric rating instruments and scales that can be used to assess adult PTSD. Some are part of comprehensive diagnostic manuals or instruments: DSM-IV TR (diagnostic criteria for 309.81 PTSD) ( 5 ); ICD-10 (F43.1 PTSD, from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision); the PTSD module, within the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV ( 6 ) or the PTSD Keane scale (PK scale) ( 7 ), within the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2).

Some are designed as either self-reports or as clinician-administered instruments specifically assessing adult PTSD: Davidson Trauma Scale ( 8 ); Distressing Event Questionnaire ( 9 ); Impact of Event Scale-Revised ( 10 ); Trauma Symptom Checklist-40 ( 11 ); PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version ( 12 ); Revised Civilian Mississippi Scale for PTSD ( 13 ); the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale ( 14 ); Trauma Symptom Inventory ( 11 ); Los Angeles Symptom Checklist ( 15 ) or the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) ( 16 ).

The underlying phenomena of PTSD are probably centrally mediated. Case in point is a study targeting women with early childhood abuse-related PTSD that found correlates of the emotional Stroop ( 17 ). Subjects with and without PTSD were compared. Both groups underwent PET scanning while performing in the color and emotional Stroop tasks and control condition. The control condition involved naming the color of rows of XXs (red, blue, green and yellow). The active color condition involved naming the color of color words (again with the same four colors), while the semantic context of the word was incongruous with the color. The active emotional condition involved naming the color (again the same four colors) of emotionally charged words (rape, bruise, weapon, and stench). These words have been shown to produce emotional arousal ( 18 ). The study examined the effectiveness of the Stroop task as a probe of anterior cingulate function in PTSD, because of the role of the anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex in stress response and emotional regulation. After comparing it with the color Stroop, the emotional Stroop displayed significantly decreased blood flow among the PTSD subjects in the anterior cingulate. Performance in the color Stroop task produced a non-specific activation of the anterior cingulate in both the PTSD and non-PTSD abused women. However, the emotional Stroop produced a relatively lower level blood flow response of anterior cingulate among PTSD abused women. These observations may indicate that PTSD anterior cingulate dysfunction is specific to the neural circuitry of the processing of emotional stimuli. Shin et al . ( 19 ) confirmed a relative decrease in blood flow in anterior cingulate activation in combat-related PTSD and also displayed a decreased blood flow for the emotional (but not color) Stroop. Taken together, these findings indicate that PTSD may have a neural component, which could significantly alter psychoneuroendocrine-immune regulation, as discussed below.

PTSD Assessment in the Military

Certain scales have been developed that specifically target military personnel.

- PTSD Checklist-Military Version ( 12 ).

- The Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD), specifically a screening and diagnostic instrument for combat-related PTSD ( 20 ), which validated as well for treatment seeking ( 21 ) and community samples ( 22 ).

- The Combat Exposure Scale measures the level of war time stress of veterans, an instrument with strong internal consistency (α = 0.85) as well as a high test–retest reliability ( r = 0.97) ( 23 ).

- The PK scale, a subscale of the MMPI-2, whose items were selected based on their ability to differentiate among veterans diagnosed with PTSD and those who were not. This scale has strong reliability (α = 0.95) and good test–retest reliability ( r = 0.94) ( 7 ).

- The SCID PTSD module is frequently used to assess presence of PTSD among veterans as well ( 24 , 25 ).

- Additional scales have been used to target assessment of PTSD among veterans, including the M-PTSD ( 26 – 29 ), the PK scale ( 30 , 31 ) or the CAPS ( 29 , 32 ).

The prevalence of PTSD diagnosis varies depending on the assessment method. One study compared three measures of PTSD among American and Korean War prisoners of war (POWs). It compared an unstructured self-report interview measure, the M-PTSD and the DSM-III-R SCID instrument. The data showed that partially unstructured interviews and the M-PTSD yielded PTSD prevalence rates of 31 and 33%, respectively, which were significantly higher than the rate of 26% yielded by the SCID. Both the unstructured clinical interview and the M-PTSD had equal accuracy, consistently disagreeing with the SCID from 7 to 15% of assessed cases ( 33 ).

Such differences in rates, depending on the assessment instrument may hold significance. According to the study ( 33 ) there may be different explanations; self-report instruments like the M-PTSD do not reflect DSM criteria as comprehensibly as the SCID. Symptoms may differ in both intensity and kind among older and younger prisoners of war. In the paradoxical side, it is possible for an individual to be diagnosed with PTSD while reporting minimal stress levels; in fact, subjective stress can be seen as a confounding factor that can have an influence on diagnosis ( 34 ).

A PTSD-negative clinical interview occurring simultaneously with a PTSD confirmation of PTSD (or also with a moderate-to-low M-PTSD score) may be indicative of chronic, but stable, PTSD. Such chronic and stable PTSD may not be clinically relevant and may not require focused intervention. They recommend to measure symptom intensity with such instruments as the CAPS ( 16 ). Such an approach could decrease PTSD-positive diagnoses among subjects with low levels of distress ( 33 ).

Allostasis and PTSD

Allostasis and the response to stress.

Allostasis refers to the psychobiological regulatory process that brings about stability through change of state consequential to stress. Psycho-emotional stress can be defined as a perceived lack, or loss of fit of one's perceived abilities and the demands of one's inner world or the surrounding environment (i.e. person/environment fit). Traumatic events that trigger PTSD are perfect examples of such onerous demands that lead to the conscious or unconscious perception on the part of the subject of not being able to cope ( 35 ).

The perception of stress is often associated with psychological manifestations of anxiety, irritability and anger, sad and depressed moods, tension and fatigue, and with certain bodily manifestations, including perspiration, blushing or blanching of the face, increased heart beat or decreased blood pressure, and intestinal cramps and discomfort. These signs mirror the spectrum of psychobiological symptoms in PTSD. These manifestations are generally associated with the nature of the stress, its duration, chronicity and severity. A group of symptoms, now referred to as the sickness behavior, is also noted that is associated with clinically relevant changes in the balance between the psychoneuroendocrine and the immune systems ( 35 – 37 ).

It was the renowned nineteenth-century French physiologist, Claude Bernard (1813–1878) who first proposed that defense of the internal milieu ( le milieu intérieur, 1856 ) is a fundamental feature of physiological regulation in mammalian systems, whence the phrase ‘homeostasis’ was coined. By the early 1930s, Walter Cannon (1871–1945) proposed that organisms engage in a dynamic process of adjustment of the physiological balance of the internal milieu in response to changing environmental conditions. Hans Selye (1907–1982) established the cardinal points of the ‘Generalized Stress Response’ in his demonstration of concerted physiological responses to stressful challenges.

Stress alters the regulation of both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system, with consequential alterations in hypothalamic control of the endocrine response controlled by the pituitary gland. Autonomic activation and the elevation of hormones, including those produced by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, play a pivotal role in regulating cell-mediated immune surveillance mechanisms, including the production of cytokines that control inflammatory and healing events ( 35 , 36 ). In brief, the perception of stress leads to a significant load upon physiological regulation, including circadian regulation, sleep and psychoneuroendocrine-immune interaction.

In brief, stress is profound alterations in the cross-regulation and interaction of the hormonal-immune regulatory axis. The experience of stress, as well as that of traumatic events and the anxiety-laden recollections thereof, produce a primary endocrine response, which involves the release of glucocorticoids (GCs). GCs regulate cellular immune activity in vivo systemically and locally. They block the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. interleukin[IL]-1β IL-6) and TH1 cytokines (e.g. IL-2) at the molecular level in vitro and in vivo , but may have little effects upon TH2 cytokines (e.g. IL-4). The net effect of challenging immune cells with GC is to impair immune T cell activation and proliferation, while maintaining antibody production. The secretion of GC by the adrenal cortex is under the control of the anterior pituitary adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH). Immune challenges release pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β, IL-6), which induce hypothalamic secretion of the ACTH inducing factor corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) in animal and in human subjects. Stressful stimuli also lead to the significant activation of the sympathetic nervous system and a rise in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e. IL-1β and IL-6). It follows that the consequences of stress are not uniform. The psychopathological and the physiopathological impacts of stress may be significantly greater in certain people, compared with those of others. The impact of stress is dynamic and multifaceted and the same person may exhibit a variety of manifestations of the psychoneuroendocrine-immune stress response with varying degrees of severity at different times. The outcome of stress can be multivalent ( 35 ).

Allostasis and Heterostasis

The term ‘heterostasis’ arose from stress research to describe the situation where the demands upon the organism exceed its inherent physiological limiting capacity. Sterling and Eyer ( 38 ) used the term ‘allostasis’ to describe the events that involve mind–body systemic regulation to recover from stress, rather than local feedback. Allostatic regulation now signifies the recovery and the maintenance of internal balance and viability amidst changing circumstances consequential to stress. It encompasses a range of behavioral and physiological functions that direct the adaptive function of regulating homeostatic systems in response to challenges ( 37 – 39 ).

The cumulative load of the allostatic process is the allostatic load. The pathological side effects of failed adaptation are the allostatic overload. Allostasis pertains to the psychobiological regulatory system with variable set points. These set points are characterized by individual differences. They are associated with anticipatory behavioral and physiological responses and are vulnerable to physiological overload and breakdown of regulatory capacities ( 39 , 40 ).

Type 1 allostatic load utilizes, as it were, stress responses as a means of self-preservation by developing and establishing temporary or permanent adaptation skills. The organism aims at surviving the perturbation in the best condition possible and at normalizing the normal life cycle. In Type 2 allostatic load, the stressful challenge is excessive, sustained or continued and drives allostasis chronically. An escape response cannot be found. Type I versus type II allostatic responses curiously reiterate Myers' observations that his patients seem to abandon themselves to the emotion and the fear that assailed them, rather than engage in the effort to counter and to overcome the challenge, which normal subjects typically undertook. Future research in PTSD from the perspective of allostasis may reveal a learned helplessness component, which could become key in the development and evaluation of treatment interventions ( Fig. 1 ).

Allostasis refers to the psychobiological regulatory process that brings about stability through change of state consequential to stress. Allostatic regulation describes the recovery and the maintenance of internal balance and viability amidst changing circumstances consequential to stress. It encompasses the Type 1 allostatic load that reflects the utilization by the organism of the range of behavioral and physiological functions that direct the adaptive function of regulating homeostatic systems in response to challenges (i.e. stress response) to develop temporary or permanent adaptation skills by means of self-preservation. Type 1 allostatic responses translate the organism aims at surviving the perturbation in the best condition possible and at normalizing the normal life cycle. By contrast, the Type 2 allostatic responses reflect a load to the organism that is excessive, sustained, or continued, and drives allostasis chronically and that precludes effective escape from the stress. The Type 1 and Type 2 allostatic response dichotomy provides a theoretical model for future research and treatment of PTSD and complex PTSD.

It is clear that stress research and PTSD research are intertwined. Psychobiological manifestations in PTSD and in complex PTSD (disorder of extreme stress) evidently pertain to the same domain of mind–body interactions, which are elucidated in psychoneuroimmunology research.

The stress response, more than likely, underlies the psychobiological sequelae of PTSD. The relevance of the field of current research on allostasis to PTSD is all the more evident when one considers that subjects position themselves along a spectrum of allostatic regulation, somewhere between allostasis (i.e. toward regaining physiological balance) and the allostatic overload (i.e. toward physiological collapse and associated potential onset of varied pathologies).

In brief, the recent advances in our understanding of the adaptation of the organism to stressful challenges, the allostatic process, present a new and a rich paradigm for research in the psychobiology of PTSD. Future research must investigate whether or not the dichotomy of Type I and Type II allostatic responses will provide an effective theoretical model for the development of novel and improved modes of intervention to treat PTSD.

PTSD—Paving the Future

The treatment of PTSD is complex, both in terms of available treatments and the myriad of trauma possibilities that cause it. Properly diagnosing PTSD according to DSM-IV criteria should be the first step, including assessing for co-morbidity. This should be followed by treatments with various degrees of demonstrated efficacy ( 41 ).

Historically, it was in the early eighties when research on the treatment efficacy for PTSD began, with multitude of case studies dealing with different kinds of PTSD having been produced since then. Overall, both cognitive behavioral approaches and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor regimes have been proved to be effective to deal with different kinds of PTSD. At the same time, there is also evidence that other treatment modalities, such as psychodynamic psychotherapy, hypnotherapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing can be effective as well; albeit their evidence is derived from less numerous and less well-controlled studies (i.e. open trials or case reports) ( 41 , 42 ). In terms of combined treatments, historically there has not been a systematic effort to address the value of combining medication with psychotherapy and/or combinations of medications. PTSD intervention is complicated further by the fact that co-morbidities (e.g. substance abuse, over-the-counter medication abuse, psychiatric disorders including major depression) are common. Particularly in situations where co-morbidity exists, a combined approached should be considered.

In addition, there are other considerations affecting the treatment appropriateness:

- type of PTSD inducing trauma;

- PTSD chronicity and

- gender, number of times being exposed to trauma and age.

Of interest due to the perilous state of the world (i.e. wars and terrorism) is the issue of the type of PTSD inducing trauma. Combat causes high rates of PTSD and makes it more refractory to treatment than other PTSD-inducing traumas ( 43 ). According to experts, combat veterans with PTSD may be less responsive to treatment that other victims of other traumatic exposures ( 41 , 42 ). It is still unclear why combat-related PTSD is more resistant to treatment than PTSD caused by other traumas. Following is a list of possible reasons:

- a great degree of psychopathology presented by patients seeking help at Veterans Administration hospitals;

- isolation from support and help upon returning home and

- potential for secondary gain, such as disability benefits ( 42 ).

Combat-caused PTSD is often associated with other psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, mood disorders and substance abuse disorders ( 22 ). More specifically, 57–62% of Croatian Balkan war veterans diagnosed with PTSD also met co-morbid diagnoses criteria ( 44 ), with the most common being depression (Muck-Seller et al ., 2003), alcohol, drug abuse, phobias, panic disorders and psychosomatic and psychotic disorders ( 45 ). In terms of PTSD-associated psychotic symptomatology, between 30 and 40% of combat-related PTSD subjects may go on to develop psychotic symptomatology ( 45 , 46 ).

It is usually believed that the most effective treatment results are obtained when both PTSD and the other disorder(s) are treated together rather than one after the other. It is becoming increasingly critical to ascertain this position because the prevalence of PTSD and disorder of complex stress is bound to rise sharply in the next decade consequential to the present multinational state of alert and anxiety following ongoing tragic, wanton and widespread terrorism and particularly with respect to combat-related PTSD in present times.

Psychotherapeutic Interventions

Psychotherapeutic approaches have a long tradition in PTSD treatment, including combat-induced PTSD. Some have more proven efficacy than others. Some of these approaches may be appropriate to address the initial stages of trauma. Psychological debriefing is an intervention given shortly after the occurrence of a traumatic event. The goal is to prevent the subsequent development of negative psychological effects. In fact, psychological debriefing approaches to PTSD can be described as semi-structured interventions aimed at reducing initial psychological stress. Strategies include emotional processing via catharsis, normalization and preparation for future contingencies ( 47 ). Gulf War veterans who underwent psychological debriefing showed no significant differences in their scores of two scales measuring PTSD when compared with the control group ( 48 ). In general, there is little evidence of psychological debriefing approaches effectively acting to prevent psychopathology, although participants seem to be open to it, which may indicate its usefulness as a rapport builder or as a screening tool. In general however, there is a lack of rigorously conducted research in this area. To this day there is paucity in the data to orient the treatment of combat-related PTSD for veterans ( 49 ). The International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety supports that exposure psychotherapy is the most appropriate approach for this disorder ( 41 ), although this approach does not show a significant influence on PTSD's negative symptomatology, such as avoidance, impaired relationships or anger control ( 49 ).

In terms of proven efficacy, cognitive behavior therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing are effective approaches to deal with PTSD ( 50 – 54 ), while other psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g. humanistic or psychodynamic interventions) do not have enough evidence to draw strong conclusions on their utility ( 42 ). Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy encompasses a myriad of approaches (i.e. systematic desensitization, relaxation training, biofeedback, cognitive processing therapy, stress inoculation training, assertiveness training, exposure therapy, combined stress inoculation training and exposure therapy, combined exposure therapy and relaxation training and cognitive therapy). There are empirical studies focusing on PTSD treatment dealing with combat-related PTSD. Vietnam veterans receiving exposure therapy displayed improvement as evidenced in terms of reducing intrusive combat memories ( 55 ), physiological responding, anxiety ( 56 ), depression and feelings of alienation, while also promoting increased vigor and skills confidence ( 57 ). Exposure therapy, combined with a standard treatment also showed effectiveness with other Vietnam veterans in terms of subject self-report symptoms related to the traumatic experiences, sleep and subjective anxiety responding to trauma stimuli ( 58 ).

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy is another approach utilized to deal with PTSD, including combat-induced PTSD. In fact, typically, there is a combination of psychotherapy and medication treatments to treat chronic PTSD ( 59 ). In general, the different co-morbidities associated with PTSD play a role in the kinds of pharmacotherapeutic treatments used for its treatment.

Antidepressants and other medications commonly used are tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antianxiety and adrenergic agents and mood stabilizers ( 60 ). Sertraline has been found effective to reduce PTSD symptomatology ( 61 , 62 ). In 1999, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sertraline as an appropriate treatment for PTSD. In fact it is the only drug to receive FDA approval to specifically combat PTSD. Sertraline and fluoxetine have produced clinical improvements among PTSD patients in randomized clinical trials ( 63 ). Paroxetine, another selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor like sertraline, is also habitually used to treat chronic PTSD ( 59 ). Mirtazapine was another successful agent when used in the treatment of PTSD afflicted Korean veterans ( 64 ). In addition, Olanzapine and fluphenazine have been successfully used with combat-induced PTSD subjects from the Balkans. Both medicines were successful in ameliorating both PTSD and psychotic symptomatology ( 43 ).

Rigorous, well-controlled methods are necessary for conducting studies on the efficacy of PTSD treatments. Well-controlled studies are characterized by the following characteristics:

- clearly defined symptoms, as well as inclusion/exclusion criteria;

- measures used are reliable and valid, with solid psychometric properties;

- utilization of blind evaluators in order to minimize expectancy and demand biases;

- properly trained evaluators to ensure reliability and validity;

- the chosen intervention programs are specific, replicable and manualized in order to maximize consistent intervention delivery;

- there is no biased assignment to treatment, which helps maximize that any detected differences and/or similarities are attributable to the treatment technique and not to other causes and

- use of treatment adherence ratings in order to ascertain if intervention parameters were followed ( 41 ).

Research on Research in PTSD: Role of Evidence-Based Research and Complementary Alernative Medicine

Future clinical research in PTSD requires the stringent, rigorous and systematic approach provided by evidence-based medicine. Evidence-based research in medicine goes beyond the routine narrative literature review. It systematically evaluates the strength of the available evidence and generates a consensus statement of the best available evidence in the form of a systematic review of the available research ( Fig. 2 ).

Evidence-based research in medicine follows the 5-step scientific process that includes stating the research question, which in evidence-based research consists of the PIC/PO question (What is the population being examined, e.g. patients with PTSD? What are the interventions being looked at, e.g. conventional treatment versus complementary medicine? Are the interventions being compared or are predictions being drawn, i.e. meta-analysis versus meta-regression approach? What is the outcome of interest, e.g. activities of daily living?). The second step involves methodology, including the sampling of the research literature, and the tools for the critical analysis of the reports. The third step refers to design which usually fall under the acronym CONSORT (i.e. consolidated standards of clinical trials). The fourth step is concerned with the analysis of the data gathered in the evidence-based research process. This commonly entails meta-analytical and meta-regression techniques, as well as individual patient data analysis (e.g. number needed to treat, NNT). Depending upon the tools utilized to evaluate the scientific literature, scores about the completeness and quality of research methodology, design and statistical handling of the findings are generated (SESTA, systematic evaluation of the statistical analysis). These values are analyzed by acceptable sampling statistical protocols to establish whether or not the sample of research reports studied by means of the evidence-based process was statistically acceptable to produce reliable inferences. The last step is a cumulative synthesis, which summarizes the process and the findings. The consensus statement reflects the best available evidence with respect to the stated PIC/PO question. The process is applied to the performance of systematic reviews, which are all-encompassing of the available literature. Best case studies in evidence-based research entail a random performance of the process of evidence-based research with a random sample of the available literature.

The future of clinical and translational research in PTSD lies in the systematic evaluation of the research evidence in treatment intervention for the patients. This type of ‘research on research’ endeavor requires attentive library search of the published materials (e.g. clinical trials) and informal individual communications with the individual researchers and authors. The collected evidence is then evaluated for research quality along certain standards [e.g. the consolidated standards of randomized trials (CONSORT)] and by means of validated instruments (e.g. Timmer scale, Jadad scale and Wong scale) ( 65 ).

The data from separate reports are pooled, when appropriate, for meta-analysis, meta-regression and individual patient data analyses. The data are analyzed from the perspective of Bayesian modeling in order to interpret data from research in the context of external evidence and judgments ( 65 ).

In the context of the treatment of patients with PTSD and co-morbidities, it is important and timely to generate a systematic review of the clinical research evidence for joint and simultaneous treatment of PTSD and the co-morbidities versus a staggered approach. The summative evaluation of the outcome of such a systematic review will generate a consensus statement that will establish whether or not the problem was framed in a clinically relevant manner (e.g. were the patient population, predictor variables and outcome measures clearly identified and relevant to the treatment of PTSD and its co-morbidities within the confines of the research?). The statement must discuss the validity of the process of integration (e.g. were the prospective inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly identified? Was the search comprehensive and explicitly described? Was the validity of the individual studies adequately assessed? Were the process of study selection, searching, assessing validity and data abstraction reliable?). The statement also produces evidence about the rigor of the process by which information was integrated (e.g. were the individual studies sufficiently similar to warrant their combination in an over-arching hypothesis-driven analysis? Are the summary findings representative of the largest and most rigorously performed studies?). The quality, presentation and relevance of the findings must be discussed (e.g. Are the key elements of each study clearly displayed? Is the magnitude of the findings statistically significant? Are the findings homogeneous or heterogeneous? Are sensitivity analyses presented and discussed? Do the findings suggest an overall net benefit for patients with PTSD?). This concerted, systematic and scientific-process driven mode of evaluating current treatment interventions for subjects with PTSD is timely and urgent to insure that the medical establishment will be prepared to handle the fast-approaching wave of PTSD cases in the next decade.

This method-driven approach for the evaluation of clinical data has merit that its product, the consensus statement, must also generate a cost-effectiveness analysis (i.e. a process of decision analysis that incorporates cost) e.g. by a step approach similar as the above method to assess the following:

- whether the problem was framed in a clinically relevant manner,

- the validity of integrated information,

- the rigor of process of integration and

- the presentation and quality of the findings.

The relevant findings in this cost-effectiveness analysis are usually expressed as the incremental cost-effectiveness between joint and simultaneous treatment of PTSD and its co-morbidities versus a staggered approach. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, i.e. the difference in costs between the two strategies divided by the difference in effectiveness between the two strategies, is often presented as well.

The consensus statement evaluates each competitive strategy, usually by means of the Markov model-based decision tree. This approach permits to model events that may occur in the future as a direct effect of treatment or as a side effect. The model produces a decision tree that cycles over fixed intervals in time and incorporates probabilities of occurrence. Even if the difference between the two treatment strategies appears quantitatively small, the Markov model outcome reflects the optimal clinical decision, because it is based on the best possible values for probabilities and utilities incorporated in the tree. The outcome produced by the Markov decision analysis is generally obtained by means of the sensitivity analysis to test the stability over a range of probability estimates and thus reflects the most rational treatment choice ( Fig. 3 ).

The purpose of evidence-based research in medicine is to elucidate the best available evidence in response to a stated clinical problem (e.g. is complementary medicine effective with patients with PTSD?). Following the scientific process of evidence-based research and the generation of the consensus statement ( Fig. 2 ), the information is implemented and evaluated by the clinician. Effectiveness and utilities data are estimated (e.g. Markov model) to aid the final clinical decision-making process ( 74 ).

The process of evidence-based research in medicine has begun its integration in the domain of PTSD. Rose et al . ( 66 ) have established by means of a systematic review of the literature that the early optimism about brief early psychological interventions, including debriefing, is actually unfounded and not supported by the research evidence. These findings confirmed earlier Cochrane-based systematic reviews ( 67 , 68 ). In a separate line of study, systematic reviews established clear support of the research evidence for serotonin reuptake inhibitors as the preferred first line treatment for PTSD, whereas mood stabilizers, atypical neuroleptics, adrenergic agents and newer antidepressants were shown to show promise, but to require further controlled trials to establish their efficacy and efficaciousness ( 60 , 69 ).

The future of clinical and translational research in PTSD also lies in its judicious integration of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). For instance, whereas PTSD symptoms are common in patients with breast cancer, this symptomatology is more effectively reduced by traditional psychosocial interventions compared with CAM-oriented intervention ( 70 ). Research will determine whether this observation is true across all forms of PTSD-inducing stress and trauma and across all subjects.

In conclusion, it is timely to design similar evidence-based research studies to establish the strength of the evidence in support of complementary approaches for the treatment of PTSD. For example, use of complementary therapies (e.g. massage and herbal/food supplements) is widespread among active military veterans and their spouses for stress and co-morbid pain and anxiety. Data indicate that up to 70% of the surveyed subjects want these interventions available at the medical treatment facility (e.g. Veterans Administration Medical Center, VAMC), despite sound supportive research data ( 71 ). This trend appears to be particularly evident among native American veterans, who usually choose not to seek treatment at VAMC facilities, in part because of the preference they hold for alternative and complementary treatments, which are usually not available at those facilities ( 72 ). This population of patients is therefore at serious risk of remaining underserved. Among the civilian population, the need for systematic reviews on the benefit of complementary medicine in the treatment of PTSD is also becoming evident in light of the increasing reports proposing the benefits of massage and acupuncture in individuals exposed to the traumatic events of 9/11 ( 73 ).

Taken together, these developments should produce important novel information about the fundamental nature of PTSD from the perspective of allostasis and about its optimal treatment using the best available evidence obtained from systematic reviews. This concerted approach will be particularly important as the prevalence of PTSD with its complex psychobiological co-morbidity rises and as alternative and complementary medical treatments for PTSD emerge and take hold. Such is, in our view, the future of research in PTSD, in order to establish a registry of regular critical evaluation updates of the available evidence for the immediate service of the clinical research community and the benefit of patients with PTSD, their families and society at large.

Study shows heightened sensitivity to PTSD in autism

For the first time, researchers from the Queensland Brain Institute have proven that a mild stress is enough to trigger post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in mouse models of autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Dr Shaam Al Abed and Dr Nathalie Dehorter have demonstrated that the two disorders share a reciprocal relationship, identifying a predisposition to PTSD in ASD, and discovering that core autism traits are worsened when traumatic memories are formed.

While recent studies in humans have highlighted the co-occurrence of ASD and PTSD, the link between the disorders is often overlooked and remains poorly understood.

"We set out to determine the occurrence of traumatic stress in ASD, and to understand the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the reported predisposition to PTSD," said Dr Al Abed.

ASD and PTSD share common features, including impaired emotional regulation, altered explicit memory, and difficulties with fear conditioning.

"We demonstrated in four mouse models of ASD that a single mild stress can form a traumatic memory."

"In a control population, on the other hand, PTSD is triggered by extreme stress."

"We wanted to understand this unique perception of stress in ASD that leads to the formation of PTSD."

The prefrontal cortex is a highly specialised area in the front part of the brain that plays a crucial role in social cognition and behaviour.

According to Dr Dehorter, dysfunction in the prefrontal cortex has been linked to both disorders.

"We identified specific cortical circuit alterations that trigger the switch between the formation of a normal memory and a PTSD-like memory during stress," said Dr Dehorter.

The prefrontal cortex contains specialised cells called interneurons, which are crucial for adapted fear memorisation and normal sensory function and play a key role in stress-related disorders.

The formation of PTSD-like memories is triggered by over activation of the prefrontal cortex that is present in ASD and throws out the balance of these cortical circuits.

The capabilities of interneurons to respond to stress is altered in ASD. This alteration worsens autism traits following the formation of a traumatic memory.

"We didn't anticipate that forming a traumatic memory would aggravate the social and behavioural difficulties in ASD."