- Healthcare Executives and Senior Leaders

- Solutions for Physicians and Clinical Staff

- Non-Healthcare Leaders

- Organizational and Cultural Transformation

- Developing Vision and Alignment

- Assessments

- Immersive Experiences

- Coaching and Facilitation

- Speakers and Inspiration

- Academic Journals

- Our Approach

- Solutions for Non-Healthcare Leaders

Lean Management, Patient Experience, Patient Safety, Performance Improvement, Quality and Safety, Quality Improvement

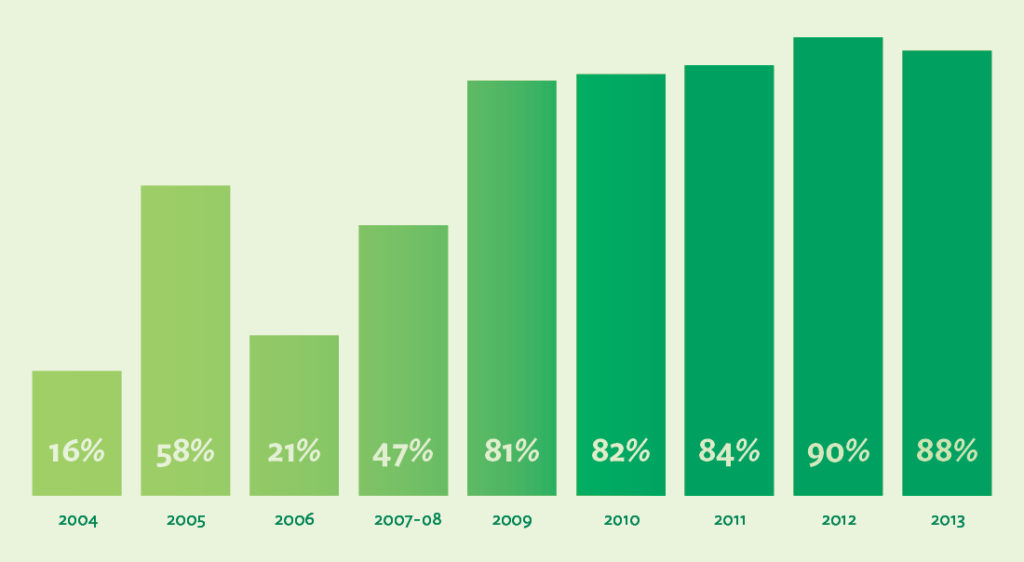

Case study | embedding a system to protect patient safety, patient safety survey participation sharply increases.

Overall staff participation in Virginia Mason’s Culture of Patient Safety survey grew from 16% in 2004 to 88% in the year 2013 alone. Affirmative answers to the survey’s key question — on whether staff speak up freely if they see something that may negatively affect patient safety — were at 80% in 2013.

Protecting Patients, Engaging Staff and Saving Costs

The Patient Safety Alert System™ at Virginia Mason is a project borne of inspiration, innovation, hard work and a dedication to always do what is best for the patient. Virginia Mason employees learn in their first day of employment that it is their duty to report anything that has caused harm or could cause harm to a patient, and the growing number of PSAs support that the organization’s culture of safety is still thriving after more than 10 years. How did Virginia Mason develop the system, and how did they embed it in their culture to continually keep patients safe? How did Virginia Mason meet its goals of dramatically better staff engagement and lower professional liability premiums—and how has the work been sustained?

Inspiration From a Factory Floor in Japan

Before the PSA system was developed, Virginia Mason’s executives viewed their organization as a quality leader that worked every day to best protect its patients. At the turn of the century, however, when they took a hard look at the data, they realized they had a lot of work to do to correct the medical errors that seemed endemic to health care in the U.S. and throughout the world.

In 2002, Virginia Mason executives were tasked with developing new ways to identify and fix the safety problems that threatened the organization’s patients every day. Gary Kaplan, MD, Virginia Mason’s chief executive officer, took them to Japan for two weeks of intensive learning to discover how Toyota had developed the Toyota Production System and worked for decades to create defect-free automobiles that were safe and reliable enough for their customers to drive. Virginia Mason’s team wondered, How did Toyota manage to increase efficiency and eliminate waste, day after day, and sustain this level of excellence?

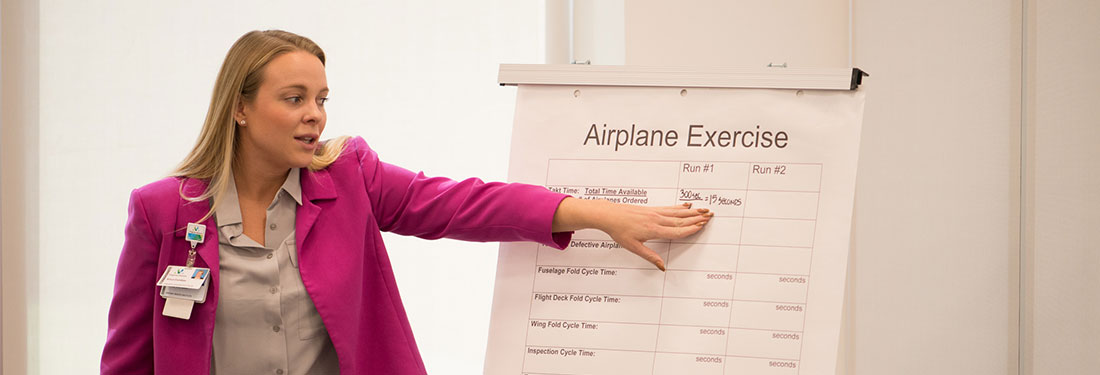

It was on the factory floor, watching the workers stop the line and work with colleagues to fix the problems with the automobiles as soon as they were discovered, that Cathie Furman, RN, the senior vice president of quality and compliance, saw something she had never witnessed before.

We were so impressed with the [Toyota] culture—the empowerment of high-school-trained assembly-line workers who felt completely comfortable stopping a multi-million-dollar line rather than sending a defective product to their teammate,” Furman says. “That was so different from what we experienced in health care, which has historically been a very blaming, hierarchical culture. 1

As much as she admired what she saw, though, she wondered if they could implement the same kind of system at Virginia Mason so that health care workers could stop a process immediately when a defect was discovered and work collaboratively to fix problems to prevent patient harm. Everyone knew that the complexity of health care meant that mistakes happened every day. Therefore, if every worker at Virginia Mason felt empowered to “stop the line,” wouldn’t that mean that the whole system would never get started again? 2

Implementing a New Patient Safety System in Seattle

The leadership team knew that Toyota’s “stop the line” process could be used to keep patients safer—but they had work to do to develop it for health care. The patient safety system they’d been using for years wasn’t working well. Katherine Galagan, MD, director of clinical laboratories, said that some employees did fill out quality improvement reports, but the reports got funneled to various departments and often ended up “lost in the wash.” It was clear to everyone who had gone to Japan that they needed a new way to galvanize the right people to come together and fix the problems right away, just as they did each day on the line at Toyota. 3

With careful planning, testing and implementation, the team modeled Virginia Mason’s new patient safety system on Toyota’s andon system—which enables any employee to alert managers or colleagues of quality or process defects, small or large. The development of the new system was difficult and time-consuming, and leaders discovered that a culture shift required a new focus on leader responsiveness as well as a degree of transparency that was not familiar to most of Virginia Mason’s employees.

Early on, Virginia Mason leaders agreed to support any staff member who called in a patient safety alert, even when the circumstances were charged. In a 2005 incident that later inspired employees to trust and use the system, a nurse observed that a physician did not follow protocol for a patient procedure. Because she believed that a patient could suffer harm from not following the protocol, she asked the physician to stop the procedure. When the physician refused, the nurse called in a PSA. The leader who responded to the alert thanked the nurse, contacted the physician and ordered him to stop the procedure. Surprised, the physician stopped the procedure but sharply berated the nurse for reporting the incident. The nurse then called in a new PSA, explaining the repercussions she received after acting in the best interest of the patient. The leader who responded to this new alert thanked the nurse and immediately took the physician offline. Virginia Mason thoroughly investigated the incident and provided training for the physician on the organization’s patient safety culture, which necessitated that employees need to feel safe whenever they reported an incident that they believed might cause harm to a patient. From that day forward, many employees knew that Virginia Mason’s top leaders truly respected their actions when they summoned the courage to stop the line. 4

For the program to be successful, it was essential not only that employees would be supported but that the problems would get fixed. As Jamie Leviton, a patient safety manager at Virginia Mason, explains, Virginia Mason’s team set out to develop a system that would consistently encourage safety reporting and transparency, result in a rapid team response and enable leaders to address issues directly with their teams. The system was based on a team vision that patient safety begins and ends on the front line, and that reporting should be “simple, easy and intuitive.” Through years of refinements, the system became capable of enabling all employees at all levels of the organization to submit a patient safety alert by phone or online, as soon as they perceived a patient had experienced harm or could potentially experience harm. 5

In September 2014, Virginia Mason’s 50,000th Patient Safety Alert was reported. By the end of 2014 the average number of PSAs was 879 — a record number for the organization. The goal, promoted at meetings and on the company’s intranet, is to reach an average of 1,000 PSAs per month.

Overall staff participation in Virginia Mason’s Culture of Patient Safety survey grew, from 16% in 2004 to 88% in 2013. Affirmative answers to the survey’s question on whether staff speak up freely if they see something that may negatively affect patient safety reached 80% in 2013.

Additionally, from May 2005 to May 2015, professional liability claims saw a 74% reduction, resulting in considerable savings each year.

Continuous Improvement: Sustaining the Gains

For more than a decade, Virginia Mason has monitored the PSA system and conducted improvement events year after year, with all levels of staff, to make it better. Here are the top key components contributing to the PSA system’s sustained success:

Employees feel safe reporting a patient safety event, near miss or potential problem. For employees to feel safe, they must experience a culture of respect in the workplace. Leaders are responsible for promoting and embodying a culture in which employees feel safe not only speaking up about barriers to patient safety but also voicing and following through on ideas for improvement.

Year after year, the organization’s leaders continually look for ways to keep the program going strong. In 2011, leaders and providers were inspired by Lucian Leape’s powerful presentation at Virginia Mason on the tie between respectful behavior and patient safety—and they knew that they had more work to do to empower employees who still did not feel safe making a PSA. Lynne Chafetz, general counsel at Virginia Mason, said that Leape discussed “not just the obvious—surgeons throwing instruments across the room,” but also “the disrespect that’s more covert.” She knew, and others in the audience also knew, that creating a deeply respectful culture was necessary to empower every employee to speak up for patient safety. That’s when Virginia Mason developed a Respect for People initiative to make the organization’s culture feel even safer for employees. 6

Every PSA is important. In the early years, the PSA program was complex, and it required extensive training throughout the organization to take hold. Later Virginia Mason’s leaders realized that if they wanted staff to report any potential threat to patient safety, no matter how small, they had to make this known. In the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Public Safety, Furman and Robert Caplan, MD, discussed the program’s dramatic results both in the terms of number of safety reports and the time it took to fix the problems. They also said that to achieve these benefits, the organization needed to keep the door open to all safety concerns. After all, whether a safety concern is “significant” depends on the point of view of the reporter—and no act of speaking up should be dismissed until the matter is investigated and leaders know that patients are safe. 7

For example, Brenda Simon, an organizational development specialist in human resources, relates how even a nonclinical employee at a health care organization can—and should—be a patient safety inspector:

One day I was walking down a stairwell in one of the hospital buildings and noticed that a long strip of yellow tape on one of the steps had come loose. I immediately thought that a patient or team member might trip on this step, so I called in a PSA and explained the situation. When I took the stairs the next day, I saw that the tape had been fixed. All of us are called upon to be on the lookout for threats to patient safety, so I was doing my part—just as the rest of my 5,000 colleagues do every day. 8

Gary Kaplan reinforces the importance of each report when he speaks to staff and to other organizations. He emphasizes the dual benefits of PSAs: “Each patient safety alert not only protects the individual patient, but gives us the opportunity to improve our processes in real time to assure the safety of every patient, every time.” 9

Staff can self-report a PSA without punitive consequences. One of the main differentiators of a lean system—whether it’s in manufacturing or health care—is that a defect signals there’s a problem not with the employee engaged in the procedure but in the organization’s processes that care for its patients. Therefore, it stands to reason that if an employee realizes that his or her own actions have caused harm—or could cause harm—to a patient, then that employee should be able to make a PSA on the incident without punitive action. In one instance, Henry Otero, MD, reported a PSA after his colleague told him a cancer patient’s magnesium level was low. “I didn’t know how I missed it,” Dr. Otero said. “But I realized it’s not about me, it’s about the patient. The process needs to stop me [from] making a mistake.” 10

Staff are supported when they make a PSA after an adverse event. Virginia Mason expects all staff to call in a PSA as soon as any patient suffers an adverse event, and they know that the way leaders respond to PSAs is crucial to keeping employees engaged and helping them see the process as personally meaningful. For every PSA after an adverse event, the leader who responds to it sincerely thanks the employee for reporting and may engage the employee to talk through the incident to help assess the level of urgency and determine next steps. For some PSAs, though, the support goes further. In a survey response, one physician recalled what happened after he called in a PSA:

Last November I undertook an emergent after-hours procedure which tragically ended in a fatal outcome. That morning I filed a PSA as a matter of course and I was surprised when I received a rapid response from the on-call PSA staff member. She facilitated providing support for the family and me that day as well as in the weeks afterwards. The support process was a much appreciated contribution at that challenging time. 11

Leaders support it. When an employee makes a PSA, the senior executive who is responsible for the area responds by ensuring that patients are safe as soon as possible and instigating a team effort to make the targeted process defect-free. Executives learn about patient safety issues in another way, too—by daily rounding. As they meet with staff on the front line, they ask if they know of any instances of patient harm, near misses and ideas for improvement. The leaders take those ideas and determine whether a process needs to be stopped or a worker needs to be taken offline during an investigation. Kaplan emphasizes that executives can’t simply let go of the process. As he says, “Every staff member can and should be a quality and safety inspector, but [he or she] will only do that if that work is supported 24-7 by the executive leadership.” 12

And because the PSA system is central to Virginia Mason’s patients-first culture, no one is surprised when a process is halted for the good of patient safety. As Denise Dubuque, surgical and procedural services administrator, recalls after one PSA, “We escalated an issue and the senior leaders stood behind the team. The staff saw that they were listened to. It was pretty powerful.” 13

Board members support it. When PSAs are reported, notices are sent to Virginia Mason’s board members. Whether it’s a physician’s error that is quickly corrected or a billing mistake that delays care for a patient, the board members get involved to ensure that leaders and staff are addressing the problems in ways that best support the organization’s patients.

When anything goes wrong at Virginia Mason, says board member Julie Morath, I know immediately what happened and what is being done. Those events are not closed until the board says they are. This is not a rubber stamp board. 14

Staff are part of the improvement process. After a PSA is called, leaders use root-cause analysis to determine whether the incident stemmed from a process problem, an individual error or a behavior issue. “Once you realize what the components are in a patient-safety alert, you can deal with correcting them,” says Lucy Glenn, MD, chair of Virginia Mason’s radiology department.

When a PSA reveals that intensive improvement work must be done to correct the problem and keep patients safe, leaders form teams that work in the affected areas. Richard Lee, administrativ director of radiology operations, describes the way leaders begin the process of engaging staff in the improvement work:

We go to the people who are actually doing the work and are in immediate contact with the patients. We have a process where we ask them to generate ideas as to what could be improved, and that’s where it starts—from identifying how our processes could be made better for the patient. 15

Staff are engaged not only from the beginning, but in subsequent meetings, improvement events, testing, implementation and sustainment.

Individuals and teams are recognized. Even in a culture in which employees are told that they’re expected to speak up for patient safety, the act of actually reporting a PSA can seem risky or overwhelming for some. That’s why the organization’s leaders work hard to respond quickly and positively to employees who report—with thank-yous from supervisors and executives; a monthly Good Catch Program, in which a single employee is recognized for a PSA that led to an exceptional solution; and the Mary L. McClinton Patient Safety Award, which is given annually to the team who has done the most to improve patient safety. This last type of recognition is especially meaningful to employees because the event not only commemorates the tragic death of a beloved patient in 2004, but also marks the time when executives chose to be transparent about the error to the staff and the press. Even more, it solidifies the organization’s fervent commitment to make health care safer for all their patients. 16

Feedback continues to make it better. Since the start, the PSA has evolved to make sure the engagement and response time continue to improve. In August 2015 the PSA system introduced easier navigation to enhance reporting. “We made these changes based on feedback from team members, who told us they wanted a simpler reporting system and a way to track how their PSAs are being handled,” says Leviton. “This new version delivers on both requests.” 17 Additionally, as a way to continue the engagement, leaders and staff were invited to sign up for training sessions to learn about the details, ask questions and continue to keep patient safety at the forefront of their work every day at Virginia Mason.

Similar resources

Lean Management, Optimizing Flow, Quality and Safety

Case study | 36-clinic federally qualified health center saves $600k annually improving patient flow.

Case Study | Building a New Outpatient Surgery Center With Patients and Staff in Mind

Lean Management, Patient Safety, Performance Improvement, Quality and Safety

Case study | surgical setup reduction improves patient outcomes, stay connected.

Sign up for our monthly emails to stay up to date with our latest news, resources, case studies, events and more.

Your information will not be shared. Learn more about our privacy policy here .

ASHRM President O’Sullivan’s March Message

We thrive together at ashrm.

Emerging Roles of Risk Managers in Senior Living and Skilled Nursing

Handling Disagreements Between Telehealth Critical Care and Bedside Providers

Strategies for Communication and Apology Are Critical for Front-line Staff

Risk Professionals Ideal to Lead Health Care ESG Journey

- Uncategorized

Case Studies in Patient Safety

- Google Plus

Storytelling has been key to learning since the beginning of humankind. Case studies are a form of storytelling that often includes learning objectives, reflection and analysis. This book by Julie K. Johnson, Helen W. Haskell and Paul R. Barach uses storytelling to explore medical cases from the viewpoints of surviving family members. The amount of effort to collect such stories must have been astounding, but the reader benefits in incalculable ways.

The book’s stories illuminate how the industry might move from a clinician-centered system of care to a patient and family-centered system of care. The authors refer to Paul Batalden’s quote, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” For example, the results of the current medical educations system are knowledgeable diagnosticians who are focused on the individual physician-patient dyad. The authors examined 153 competencies across disciplines internationally that seem to correlate with good outcomes. The book’s stories are organized by these competencies:

- Medical knowledge, patient care

- Professionalism

- Interpersonal/communication skills

- Practice-based learning and improvement

- System-based practice

- Interprofessional collaboration

- Personal and professional development

One sees where professionalism and interpersonal/communication skills are greater important deficits for the families than knowledge or patient care aspects. This sets up the challenge for the reader, as the authors promote, to think differently about how to emotionally and intellectually engage patients and providers in healthcare transformation.

Discussed are 24 cases resulting from in- and out-patient settings in locations throughout the English-speaking world. One poignant case concerned a routine endoscopic procedure, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Post discharge, the patient began regurgitating, perspiring and was in pain. A telephone call to the office nurse resulted in a Tylenol suggestion. Then the physician called and suggested soup. A family member demanded a direct admission. The patient arrived at the emergency room with no forwarding message from the physician so she waited 12 hours for pain meds, but a full workup was achieved. The physician was not returning any emergency room calls as it was after 5 p.m. and the covering colleague said “not my patient.” As the patient deteriorated, a catheter was inserted. Then she was moved to the ICU and then to CCU. Diagnosis: sepsis. No record was ever found for the catheter order nor the ICU or CCU admissions. By now hospital specialists were attending to the patient with no sign of the original surgeon. The first code blue was noted.

With pneumonia and sepsis prevailing, staff placed a ventilator. Physicians mentioned pancreatitis after ERCP. They said it was not uncommon and the patient should recover. Eleven days later the patient had a cardiac arrest and coded. There were conflicting stories whether this occurred during a bath or during some suctioning. The code was unsuccessful. The family was not called by nursing per the protocol.

The CEO called the family back about a month after the death. New management had taken over the hospital. The CEO was trying to set a meeting with the family and physician, but the physician refused. After a year from the death, the physician accepted a meeting. Evidently, he felt comfortable because the family had not requested an autopsy so there was no way to prove whether the surgeon should have done the procedure in the first place or if he had done it wrong. The family regrets the omission of the autopsy because they saw there was no redress possible without it. After a complaint, the state medical board saw no wrong doing on the part of the surgeon. The state’s health services department did cite the emergency room for the lack of care of the patient.

The family felt abandoned by the surgeon, wrote a book about the event and discovered that adverse events were not nearly as common as they were led to believe. The book reviews further insight and notes ERCP is now widely overused.

In conclusion, this book presents poignant case studies that prompt one to think about various sides of stories and how systems, cultures and technical skills intertwine to affect life and death. One sees how the lack of communication can trump all of the aforementioned items to create a disaster. However, the reader is not left depressed, but instead inspired by the people sharing their stories and by the subsequent critical thinking that can occur after reading them.

Johnson, J., Haskell, H., & Barach, P. (2016) Case Studies in Patient Safety. Subury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning

You may also like

Building a High-Reliability Organization: A Toolkit for Success

ASHRM Whitepaper – Telemedicine: Risk Management Considerations

Stronger: Develop the Resilience You Need to Succeed

Sign up for ashrm forum updates.

Provide your information below to subscribe to ASHRM email communications

ASHRM Forum

- Submit an Article

Recent Articles

- ASHRM President O’Sullivan’s March Message March 20, 2024

- We thrive together at ASHRM January 10, 2024

- Emerging Roles of Risk Managers in Senior Living and Skilled Nursing October 16, 2023

- Handling Disagreements Between Telehealth Critical Care and Bedside Providers September 12, 2023

- Strategies for Communication and Apology Are Critical for Front-line Staff September 7, 2023

- January 2024

- October 2023

- September 2023

- November 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- November 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- February 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- ASHRM Academy

- ASHRM President Message

- ASHRM Updates

- Behavioral Health

- Book Review

- Emergency Preparedness

- Enterprise Risk Management (ERM

- Human Capital

- Legal & Regulatory

- Letter from the Chair

- Member Profile

- Operational

- Patient Safety/Clinical Care

- Sustainibility

- Angela Lucas, MSN, BSN, RN, CCRN-K

- Anne Huben-Kearney, RN, BSN, MPA, CPHRM, CPHQ, CPPS, DFASHRM

- Arlene Luu, RN, BSN, JD, CPHRM

- Barbara McCarthy RN, MPH, CIC, CPHQ, CPHRM, FASHRM

- Benedict Hane

- Chad Follmer, ARM, MBA

- Dan Corcoran

- Dan Groszkruger, JD, MPH, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Deborah Lessard CPHRM, FASHRM, MS and Leigh Ann Yates, AIC, MBA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Deborah Lessard, Esq., RN, JD, MA, BSN, CPHRM, FASHRM

- Denise Shope, RN, MHSA, ARM, CPHRM, DFASHRM and Nancy Connelly, RN, BA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Denise Winiarski JD, CPHRM Emily Klatt, JD Amir Kazerouninia, MD, PhD

- Ferdinando L. Mirarchi, DO, FAAEM, FACEP

- Forum Task Force Chair Leigh Ann Yates, AIC, MBA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Franchesca J. Charney, RN, MS, CPHRM, CPPS, CPSO, DFASHRM and Guy Whittall-Scherfee, MS

- Heidi Harrison, CPHRM

- Jessica J. Ayd, Esq.; Sherri Hobbs, MSM, MSN, RN, CPHQ; Heather Joyce-Byers, MSJ, BS, RN, CCRN-K, CPHRM; Shannon M. Madden, Esq.

- Joan Porcaro, RN, BSN, MM, CPHRM

- John C. West, JD, MHA, DFASHRM, CPHRM,

- John D. Banja, PhD

- Julie Radford, JD, CPHRM

- Karen Garvey, DFASHRM, CPHRM, and CPPS

- Karen Wright RN, BSN, ARM, CPHRM

- Kathleen Shostek, RN ARM FASHRM CPHRM CPPS

- Kenita Hill, MSA, CPHRM, LNHA, LPN

- Larry Veltman, MD, FACOG, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Leigh Ann Yates and Stephanie Nadasi

- Leigh Ann Yates, MBA, CPHRM, AIC, DFASHRM

- Mackenzie C. Monaco

- Maggie Neustadt, JD CPHRM, FASHRM

- Margaret Curtin, MPA, HCA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Mark Dame, MHA, CPHRM, FACHE

- Melanie Osley and Holly Taylor

- Melanie Osley, RN, MBA, CPHRM, CPHQ, CPPS, ARM, DFASHRM

- Melanie Taylor, Esq.

- Melinda Van Niel, BA, MBA and Doug Wojcieszak, MA, MS, BS

- Michael G. Lloyd, MBA, CPCU, ARM, CPHRM

- Monica Cooke BSN, MA, RNC, CPHQ, CPHRM, FASHRM

- Nancy Connelly, RN, BA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Nancy Connelly, RN, BA, CPHRM, DFASHRM and Kenita Hill, MSA, CPHRM, LNHA, LPN

- Paula Caballero

- Rhonda DeMeno, RN, MS,MPM, BSHRM, CBIC, CPHRM and Joan Porcaro, RN, BSN, MM, CPHRM

- Rita Barrett-Cosby, CPHRM

- Robin Diamond

- Ryan Solomon, JD

- Sarah B. Roberts, MPH, CHES, CPHQ, CPHRM, ARM, AIS, AINS

- Scripps La Jolla Memorial Quality Team Memorial Quality Team

- Steven D. Weiner and Mario Giannettino

- Sue Boisvert, BSN, MHSA, CPHRM, FASHRM

- Susan Lucot, MSN RN

- Suzanne Natbony

- Tatum O’Sullivan, RN, BSN, MHSA, CPHRM, DFASHRM, CPPS

- Tricia Brooks-Phillips, MSN, RN, CPHRM

- Vallerie H. Propper, JD, MPH

- Vicki J. Missar

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Patient safety review and response case studies by clinical specialty

This page shows case studies, listed by clinical specialty, of where the National Patient Safety Team worked with partners to address issues identified through its review of recorded patient safety events.

Urgent/emergency care

General medicine, intensive care, obstetrics and gynaecology/midwifery, paediatrics and child health, primary care.

You can find out more about our processes for identifying new and under recognised patient safety issues on our using patient safety events data to keep patients safe and reviewing patient safety events and developing advice and guidance web pages.

- COVID-19 swab snapped in tracheostomy

- Risk of dose error when using intraosseous lidocaine in children

- ePrescribing systems and insulin combinations

- Risks of ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitiser

- Risk of airway obstruction from green anaesthetic swabs

- Dual purpose naso-gastric tubes with ENFit® connectors and the risk of aspiration

- Diagnosis and management of supraglottitis

- Sucrose vial cap identified as potential choking hazard in babies

- The risk of aspiration from orally administered contrast media with spigotted nasogastric tubes

- Metacarpal wrong site surgery – inconsistent terminology used to describe anatomy

- Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome from rapid correction of severe hypo/hypernatraemia

- Ensuring timely updates to clinical risk assessment and management triage tools in emergency departments

- Ingested gel toilet discs

- Delayed oxygenation of neonate during resuscitation when oxygen not ‘flicked’ on

- Equipment falling onto critically ill patients during intrahospital transfers

- Misapplication of spinal collars resulting in harm from unsecured spinal injury

- Ensuring compatibility between defibrillators and associated defibrillator pads

- Ensuring pregnant women with COVID-19 symptoms access appropriate care

- Overdose of oral vitamin D related to frequency and duration of treatment

- Administration of chemotherapy and reactivation of Hepatitis B

- Delay in treatment with prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC)

- Harm from catheterisation in patients with implanted artificial urinary sphincters

- Confusion between different strength preparations of alfentanil

- Distinguishing between haemofilters and plasma filters to reduce mis-selection

- Variation in use of cardiac telemetry

- Ceftazidime as a 24-hour infusion

- Tacrolimus – risk of overdose when converting from oral to intravenous route

- Haloperidol prescribing for confused/agitated/delirious patients

- Ensuring oxygen delivery when using two step humification systems

- Pregnancy tests not performed before anaesthesia

- Ventilator left in standby mode

- Sudden patient deterioration due to secretions blocking heat and moisture exchanger filters

- Anaesthetic machines used as ventilators: issues with circuit set up

- Importance of ‘tug test’ for checking oxygen hose when transferring a patient to a portable ventilator

- Use of trimethoprim in women of child-bearing age

- Assessment of risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) when prescribing combined hormonal contraceptives

- Harm from prescribing and administering Syntometrine when contraindicated to woman with significantly raised BP

- Unnecessary caesarean section for breech presentation if not scanned on the day

- HIV prophylaxis in women and new-borns

- Ensuring the safe use of plastic cord clamps at caesarean section

- Warning on the use of ethyl chloride during fetal blood sampling

- Risk of babies becoming unwell following move to virtual home midwifery visits

- Testing ammonia levels in children

- Unintentional perforation of oesophagus in neonates from invasive procedures

- Chemical burn to a neonate from use of chlorhexidine

- Risk of harm from spinal administration of anaesthetic agent containing preservative

- Hip cement – different expiry dates for separate components in the same pack

- Bone cement implantation syndrome

- Surgical skin preparation solution entering the eye during surgery

- Retained surgical instrumentation and complex procedures involving multiple teams and equipment

- Unintentional retention of bone cement following hip surgery

- Monitoring patients taking nitrofurantoin for potential lung disease

- Unintended bolus of medication if infused at speed from residual space in giving set

- Infrared temperature screening to detect COVID-19

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, case study: more patient safety by design – system-based approaches for hospitals.

Structural Approaches to Address Issues in Patient Safety

ISBN : 978-1-83867-085-6 , eISBN : 978-1-83867-084-9

Publication date: 24 October 2019

Since the publication of the report “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System” by the US Institute of Medicine in 2000, much has changed with regard to patient safety. Many of the more recent initiatives to improve patient safety target the behavior of health care staff (e.g., training, double-checking procedures, and standard operating procedures). System-based interventions have so far received less attention, even though they produce more substantial improvements, being less dependent on individuals’ behavior. One type of system-based intervention that can benefit patient safety involves improvements to hospital design. Given that people’s working environments affect their behavior, good design at a systemic level not only enables staff to work more efficiently; it can also prevent errors and mishaps, which can have serious consequences for patients. While an increasing number of studies have demonstrated the effect of hospital design on patient safety, this knowledge is not easily accessible to clinicians, practitioners, risk managers, and other decision-makers, such as designers and architects of health care facilities. This is why the Swiss Patient Safety Foundation launched its project, “More Patient Safety by Design: Systemic Approaches for Hospitals,” which is presented in this chapter.

- Hospital design

- Information dissemination

- Medical error

- Patient safety

- System-based interventions

- Systemic approach

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments.

We would like to thank the members of the expert group for their commitment to our project and their valuable input. We are also grateful to the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, and the Swiss National Science Foundation for their financial support, which has helped us not only in completing our project but also in producing our brochure, and in organizing the symposium.

Kobler, I. , Angerer, A. and Schwappach, D. (2019), "Case Study: More Patient Safety by Design – System-based Approaches for Hospitals", Structural Approaches to Address Issues in Patient Safety ( Advances in Health Care Management, Vol. 18 ), Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-823120190000018001

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019 Emerald Publishing Limited

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Open access

- Published: 02 May 2024

Associations between patient safety culture and workplace safety culture in hospital settings

- Brandon Hesgrove 1 ,

- Katarzyna Zebrak 1 ,

- Naomi Yount 1 ,

- Joann Sorra 1 &

- Caren Ginsberg 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 568 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

94 Accesses

Metrics details

Strong cultures of workplace safety and patient safety are both critical for advancing safety in healthcare and eliminating harm to both the healthcare workforce and patients. However, there is currently minimal published empirical evidence about the relationship between the perceptions of providers and staff on workplace safety culture and patient safety culture.

This study examined cross-sectional relationships between the core Surveys on Patient Safety Culture™ (SOPS®) Hospital Survey 2.0 patient safety culture measures and supplemental workplace safety culture measures. We used data from a pilot test in 2021 of the Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set, which consisted of 6,684 respondents from 28 hospitals in 16 states. We performed multiple regressions to examine the relationships between the 11 patient safety culture measures and the 10 workplace safety culture measures.

Sixty-nine (69) of 110 associations were statistically significant (mean standardized β = 0.5; 0.58 < standardized β < 0.95). The largest number of associations for the workplace safety culture measures with the patient safety culture measures were: (1) overall support from hospital leaders to ensure workplace safety; (2) being able to report workplace safety problems without negative consequences; and, (3) overall rating on workplace safety. The two associations with the strongest magnitude were between the overall rating on workplace safety and hospital management support for patient safety (standardized β = 0.95) and hospital management support for workplace safety and hospital management support for patient safety (standardized β = 0.93).

Conclusions

Study results provide evidence that workplace safety culture and patient safety culture are fundamentally linked and both are vital to a strong and healthy culture of safety.

Peer Review reports

About 10% of patients internationally have adverse events Footnote 1 in hospitals, and about half of these adverse events are considered to be preventable [ 1 , 2 ]. About 7% of these adverse events result in death and about half result in temporary or permanent disability. As discussed in the seminal publication To err is human , building a culture of safety is a key component of preventing medical errors and harm to patients [ 3 ]. A growing body of domestic and international research has shown associations between better patient safety culture and reduced adverse events and improved patient experience [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ].

In 1993, the Health and Safety Commission defined safety culture in the following manner: “The safety culture of an organisation is the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behaviour that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organisation’s health and safety management. Organisations with a positive safety culture are characterized by communications founded on mutual trust, by shared perceptions of the importance of safety and by confidence in the efficacy of preventative measures” [ 9 ]. Since then, the concept of safety culture has been applied to the healthcare setting, especially hospitals, and it has been demonstrated that the employer’s safety culture influences the attitude and behaviors of both providers and staff, thus contributing to the overall safety of the organization [ 10 ]. To comprehensively assess safety culture in the hospital setting, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) sponsored the development of the Surveys on Patient Safety Culture® (SOPS®) Hospital Survey that assesses provider and staff perceptions of the extent to which the organizational culture in hospitals supports patient safety [ 11 ].

Although safety culture in healthcare has, until recently, focused on patient safety, several major reports and events, including the World Health Organization’s World Patient Safety Day 2020 [ 12 ], the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) National Steering Committee for Patient Safety’s National Actional Plan to Advance Patient Safety [ 13 ], and the National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being [ 14 ], have identified workforce safety as a critical component of advancing patient safety. Workplace safety, including stress and burnout, is a critical issue, as the overexertion injury rate for hospital workers is more than twice the national average of U.S. full time workers [ 15 ]. The most important risk factor for these injuries is the manual lifting, moving, and repositioning of patients [ 16 ]. Further, these injuries are frequently underreported [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Additionally, healthcare workers are four times more likely to be victims of verbal and physical workplace violence and aggression than workers in other private industries [ 20 , 21 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the safety of healthcare workers through shortages of personal protective equipment, high risk and fears over becoming infected and infecting family members with the virus [ 22 , 23 ], and increased patient loads and staffing shortages [ 24 , 25 ].

As a response to this increased concern about the safety of healthcare workers, AHRQ funded the development of the supplemental item set for the SOPS Hospital Survey which focused on the workplace safety of providers and staff in the hospital setting. Recent prominent reports and integrative models of safety culture have shown that not only is workplace safety culture an important factor in patient safety culture, but that they are mutually affected [ 21 , 26 , 27 ]. Both workplace safety culture and patient safety culture are integral to an overall culture of safety and are influenced by overall organizational culture and attitudes toward process improvements, and they are inextricably linked in that improvements in one area influence the other. For example, if providers and staff do not have appropriate equipment or sufficient training to properly use equipment to lift and move patients, patients may fall and providers and staff may also fall or be otherwise injured. Despite this theoretical foundation, there is limited empirical evidence about the crucial relationship between workplace safety culture and patient safety culture. Prior studies have only examined the relationship in single hospitals or hospital units and for a small set of workplace safety culture measures such as workplace violence and burnout [ 28 , 29 , 30 ].

This paper presents evidence regarding this crucial gap by analyzing the associations between workplace safety culture and patient safety culture for a large set of patient safety culture and workplace safety culture measures assessed in a diverse set of hospitals with a wide range of characteristics and geographic locations. To perform this analysis, we used data from a pilot test of the AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture® (SOPS®) Hospital Survey 2.0 Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set, which was conducted in 28 hospitals across 16 states, which allows for more generalizable findings than data from a single hospital or unit. We hypothesize that more positive workplace safety culture is associated with more positive patient safety culture.

Data sources and measures

We employed a cross-sectional study design which assessed the associations between patient safety culture measures which are the core items from the AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture® (SOPS®) Hospital Survey 2.0 [ 31 ] and workplace safety culture measures from the SOPS Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set for Hospitals [ 32 ]. The SOPS Hospital Survey 2.0, released in 2019, is an update of the original survey released in 2004. Designed to assess hospital provider Footnote 2 and staff Footnote 3 perceptions about patient safety issues and event reporting, the core SOPS Hospital Survey 2.0 includes 32 items aggregated into 10 patient safety culture composite measures and one overall patient safety rating item and one item on the number of events reported (not reported in this study), respectively.

Workplace safety culture is assessed using the Hospital Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set. This item set was developed by Westat, under contract with AHRQ, in response both to increased concern about healthcare worker safety as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and a recognition of the importance of workplace safety in ensuring patient safety. The items were developed based on literature on workplace safety in hospitals, interviews with hospital workplace safety experts and researchers, and through feedback from the SOPS Technical Expert Panel (TEP) and workplace safety subject matter experts (SMEs). The development team conducted iterative cognitive testing of the draft survey items with 20 hospital providers and staff and received input from the TEP and SMEs at multiple stages in the development process. The workplace safety supplemental item set includes 16 items aggregated into six composite measures, as well as three single item measures and one overall workplace safety rating.

In 2021, a pilot study was conducted which collected responses to the workplace safety items for 28 hospitals in 16 states across the U.S. The purpose of this pilot study was to obtain data for psychometric analyses to examine the reliability and validity of the Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set for hospitals. This psychometric analysis of the workplace safety culture measures provided evidence that the measures were reliable and valid [ 33 ]. Psychometric analysis of the SOPS Hospital Survey 2.0 have previously shown that the patient safety culture measures are also reliable and valid [ 34 ].

Recruitment of hospitals occurred through AHRQ SOPS email listserv subscribers, users of the survey, webinar participants, and through outreach to hospital stakeholder organizations. From the list of interested hospitals, a convenience sample of 28 hospitals were selected that varied by several characteristics (e.g., bed size, region, ownership, teaching status), but were not statistically representative of all U.S. hospitals. The pilot study was a web-based survey administered to a census of all providers and staff in the selected hospitals with the workplace safety items near the end of the survey. Each provider and staff member of the selected hospitals received an email with a unique survey link. At the beginning of the survey, the following statement was included: “The survey is voluntary, but your feedback will help your hospital identify areas for patient safety and workplace safety improvement. If you do not wish to answer a question, you may leave it blank. Westat will keep your individual responses to this survey confidential. Only group results will be reported.”

Out of 19,979 surveys distributed, 7,037 providers and staff responded, resulting in a 35% overall response rate. Across all pilot study hospitals, respondents had the following category of staff position: 35% nurses; 2% physician or physician assistant; 18% other clinical position; 11% management; 20% support, and 13% other staff position [ 35 ].

The patient safety measures were as follows, with the number of items in parentheses: Teamwork (3); Staffing and Work Pace (4); Organizational Learning-Continuous Improvement (3); Response to Error (4); Supervisor, Manager, or Clinical Leader Support for Patient Safety (3); Communication About Error (3); Communication Openness (4); Reporting Patient Safety Events (2); Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety (3); Handoffs and Information Exchange (3); and Patient Safety Rating (1) [ 36 ].

The workplace safety measures were as follows, with the number of items in parentheses: Protection from Workplace Hazards (3); Moving, Transferring, or Lifting Patients (3); Addressing Workplace Aggression from Patients or Visitors (2); Workplace Aggression Policies, Procedures, and Training (2); Addressing Verbal Aggression From Providers or Staff (1); Supervisor, Manager, or Clinical Leader Support for Workplace Safety (3); Hospital Management Support for Workplace Safety (3); Workplace Safety and Reporting (1); Work Stress/Burnout (1); and Overall Rating on Workplace Safety for Providers and Staff (1) [ 32 ].

We calculated hospital-level percent positive scores as the percentage of respondents within a hospital who answered positively (% Strongly agree/Agree or Always/Most of the time) for positively worded items, and (% Strongly disagree/Disagree) for negatively worded items for each item. Percent positive scores can range from 0 to 100. These hospital-level percent positive scores for the items within each composite measure were equally weighted and averaged to compute hospital-level composite measure scores. There was one exception to this scoring: Work Stress/Burnout was reported as the percentage of respondents that chose the response ‘3’, Footnote 4 ‘4’, Footnote 5 or ‘5’ Footnote 6 , indicating they had one or more symptoms of work stress or burnout.

Hospital characteristics as Covariates

Three hospital characteristics obtained from the 2020 American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey of Hospitals Database were examined as covariates or control variables. The first control variable was bed size which was categorized into seven categories: 6–24 beds, 25–49 beds, 50–99 beds, 100–199 beds, 200–299 beds, 399 beds, and 400 or more beds. The seven categories were coded as 1 through 7 and this variable was included as a continuous variable modeled linearly in the regression models. The second control variable was ownership status, which was either a government-owned hospital or non-government-owned hospital. The third control variable was teaching status, which was either a teaching or non-teaching hospital. These variables were included because hospital characteristics have been demonstrated to show consistent associations with SOPS Hospital Survey scores [ 37 ] and are also likely to be associated with Hospital Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set measures.

Analysis sample

All analyses were conducted using the responses of 6,684 providers and staff respondents (353 of the 7,037 respondents did not answer any workplace safety items) from 28 hospitals that participated in the SOPS Hospital Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set pilot study.

All analyses were conducted using SAS V9 and were at the hospital level.

Descriptive statistics

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for hospital-level percent positive scores (or percent stress/burnout), were calculated for all workplace safety culture and patient safety culture composite measures, as well as the two workplace safety culture single item measures and the overall ratings for both workplace safety culture and patient safety culture. These descriptive statistics show the variation in the patient safety culture and workplace safety culture measures and provide context for interpreting the regression analyses.

Multiple regressions

We conducted a series of multiple regressions to examine the associations between hospital workplace safety culture measures and patient safety culture measures. Specifically, each regression model had one patient safety culture measure as the dependent variable, and one workplace safety culture measure as the independent variable along with the control variables (hospital bed size, teaching status, and ownership). To test a key assumption of linear regression, we confirmed that the percent positive (or negative in the case of burnout) values for each measure were normally distributed.

We included only one workplace safety culture measure in each model because tests of variance inflation factors (VIF) showed substantial evidence of multicollinearity when including all workplace safety culture measures in a single regression. Rules-of-thumb for an indication of substantial multicollinearity are VIFs generally between 4 and 10, with a VIF above 10 indicating substantial multicollinearity [ 38 ]. Tests of VIF when including all workplace safety culture measures in the same regression indicated a VIF of 12.8 for Hospital Management Support for Workplace Safety and a VIF of 12.2 for the Overall Rating on Workplace Safety for Providers and Staff .

Because we are simultaneously conducting multiple hypothesis tests, it is important to adjust the p -values of the hypothesis tests to control the number of false positives due to chance. We adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing by controlling the false discovery rate which is the expected proportion of false rejections (statistically significant estimates) among all rejected tests, using the standard method by Benjamini and Hochberg [ 39 ].

Table 1 shows, for each workplace safety culture and patient safety culture measure, the means and standard deviations for all 28 hospitals of the percentage of individual responses that were positive (except for Work Stress/Burnout ). Percent positive scores for the patient safety culture composite measures ranged from 55.6% ( Staffing and Work Pace ) to 80.6% ( Teamwork) . The Patient Safety Rating percent positive score was 63.9%.

Percent positive scores for the workplace safety composite measures ranged from 58.1% ( Addressing Workplace Aggression From Patients or Visitors ) to 90.3% ( Protection from Workplace Hazards ). Work Stress/Burnout , measured as the overall percentage of respondents in a hospital that reported experiencing symptoms of burnout, was 30.4%. The Overall Rating on Workplace Safety for Providers and Staff percent positive score was 53.1%. These statistics indicate that while the vast majority of providers and staff report they had adequate physical protection, far fewer reported they had adequate protection from workplace aggression from patients or visitors. Further, substantially fewer providers and staff reported positive ratings of overall workplace safety culture than reported positive ratings of overall patient safety culture.

Tables S1 a and S1 b present the results of multiple linear regressions examining associations for workplace safety culture measures with the patient safety culture measures. Table S1 b includes the number of statistically significant associations and the mean and range of the standardized regression coefficients of those statistically significant associations for each workplace safety culture measure. Of the 110 regression estimates, 69 were statistically significant ( p < 0.05). Tables S2 a and S2 b provide model fit statistics of each of the regression models.

Three workplace safety culture measures were significantly associated with all 11 patient safety culture measures and had the largest average magnitude associations ( Overall Rating on Workplace Safety for Providers and Staff , mean β = 0.67; Supervisor, Manager, or Clinical Leader Support for Workplace Safety , mean β = 0.62; and Hospital Management Support for Workplace Safety , mean β = 0.62). These three measures had the largest number of associations with patient safety culture measures on average and represented four of the five largest magnitude associations with patient safety culture measures: Overall Rating on Workplace Safety for Providers and Staff and Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety (β = 0.95); Hospital Management Support for Workplace Safety and Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety ( β = 0.93); Supervisor, Manager, or Clinical Leader for Workplace Safety and Response to Error (β = 0.90); and, Overall Rating on Workplace Safety for Providers and Staff and Overall Patient Safety Rating ( β = 0.85).

Two workplace safety culture measures ( Protection from Workplace Hazards , mean β = 0.57 and Workplace Safety and Reporting , mean β = 0.53) were significantly associated with 10 of the 11 patient safety culture measures. Associations with Protection from Workplace Hazards ranged from 0.39 with Reporting Patient Safety Events to 0.79 with Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety . Associations with Workplace Safety and Reporting ranged from 0.28 with Reporting Patient Safety Events to 0.75 with Response to Error .

Two workplace safety culture measures ( Moving, Transferring, or Lifting Patients and Work Stress/Burnout ) were significantly associated with seven out of 11 patient safety culture measures. Statistically significant associations of Moving, Transferring, or Lifting Patients with patient safety culture measures had an average of β = 0.57, ranging from 0.31 with Reporting Patient Safety Events to 0.87 with Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety . Statistically significant associations of Work Stress/Burnout with patient safety culture measures had an average of β = -0.53, ranging from − 0.47 with Organizational Learning – Continuous Improvement to -0.60 with Staffing and Work Pace . Associations were negative, indicating that higher Work Stress/Burnout was associated with lower patient safety culture.

The three workplace aggression measures ( Addressing Workplace Aggression from Patients or Visitors ; Workplace Aggression Policies, Procedures, and Training ; and Addressing Verbal Aggression from Providers or Staff ) had the lowest number of significant associations and smallest associations on average, with two or fewer significant relationships per measure with the patient safety culture measures. Specifically, Addressing Workplace Aggression from Patients or Visitors was significantly associated with only Communication Openness (β = 0.42); Workplace Aggression Policies, Procedures, and Training was not significantly associated with any patient safety culture measures; and Addressing Verbal Aggression from Providers or Staff was significantly associated with two patient safety culture measures (mean β = 0.56, ranging from 0.50 with Response to Error to 0.61 with Teamwork ).

We examined the relationship between hospital provider and staff perceptions of workplace safety culture and patient safety culture. Our analyses revealed 69 out of 110 statistically significant associations between the workplace safety and patient safety culture measures, while controlling for hospital bed size, ownership, and teaching status, and controlling for multiple comparisons. All workplace safety measures were significantly associated with at least half of the patient safety culture measures, except for the three measures related to addressing workplace aggression from patients or other staff; these measures were only associated with up to two patient safety culture measures.

Theoretical models of organizational culture in health care have posited that the values and strategy of leadership along with characteristics of organizational structure and culture heavily influence the intermediate process domains of staffing; training; employee safety through protection from workplace hazards; resources to safely care for patients and themselves including proper equipment and staffing to move and lift patients safely; and other factors [ 27 ]. These process domains play a key role in how well providers and staff collaborate and are focused on patients and their safety, which in turn influences both satisfaction and intention to leave of providers and staff as well as patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes [ 30 ]. This study provides empirical evidence to support multiple aspects of this model. In particular, hospital management support for and an overall perception of a healthy and robust workplace safety culture have the strongest associations with perceptions of patient safety culture. Additionally, feeling free to report workplace safety incidents without negative consequences, having sufficient resources to protect themselves from hazards, and being able to move and lift patients safely are also strongly associated with staff and providers’ perceptions of patient safety culture.

The strongest association with Work Stress/Burnout was with Staffing and Work Pace , which provides evidence that lower stress and burnout of providers and staff is associated with having sufficient staff, reasonable working hours, and better work pace. The strong relationships between higher burnout and poor patient safety culture are consistent with prior literature [ 29 , 30 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ].

The three measures regarding workplace aggression (policies, procedures, and training; and addressing workplace aggression from patients or visitors and other providers or staff) were not as strongly associated with the patient safety culture measures as the other workplace safety culture measures. We performed a detailed investigation to explore these results and found that two outlier hospitals were the primary reason for the relatively large negative (though nonsignificant) associations between the Workplace Aggression Policies, Procedures, and Training composite measure and the patient safety culture measures. However, these outliers do not explain the low magnitudes and sometimes negative direction of the remaining associations between the workplace aggression and patient safety culture measures. Further research is required to assess why associations between the aggression measures and patient safety culture measures may be smaller or whether these results are limited to this particular sample.

This study has several limitations. First, while the number of hospitals is relatively large among the empirical literature on the relationship between patient safety and workplace safety cultures, the number of hospitals is still relatively small. Second, even though the study hospitals were diverse on a number of characteristics, they were selected as a convenience sample and thus are not representative of all U.S. hospitals. Third, the study is cross-sectional and examines associations, so we were unable to provide evidence on how changes in measures vary with changes in other measures or attribute causal directions to the relationships. That is, although workplace safety culture measures were used as the independent variables in the model, we cannot say definitively that better workplace safety causes better patient safety culture, but only that they are related and likely influence each other.

The analyses presented in this paper revealed relationships between patient safety culture and workplace safety culture measures. We found statistically significant associations between the majority of the workplace safety culture and patient safety culture measures, confirming our hypothesis that these important perceptions would be positively related. Overall, support from hospital management and supervisors, manager, or clinical leaders to ensure workplace safety, being able to report safety problems without negative consequences, and the overall rating of workplace safety culture were the workplace safety culture measures most strongly associated with patient safety culture.

These results provide empirical evidence to support the contention that the concepts of workplace safety culture and patient safety culture are fundamentally linked, and both are integral to a strong and healthy culture of safety. Future research should focus on collecting additional evidence about this relationship using larger sample sizes and additional measures to substantiate these results. This relationship could be assessed outside of hospital settings; nursing homes, for example, could provide fertile ground for additional research, given AHRQ’s recent release of a SOPS Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set for Nursing Homes. Finally, the relationship between measures of aggression and patient safety culture should be further studied conceptually and empirically to determine whether the weak relationship presented in this study is generalizable to other U.S. hospitals.

Data availability

Some of the de-identified SOPS Hospital Survey 2.0 data are available upon request for research purposes.

An adverse event in healthcare is also known as a “patient safety event” which is defined differently by different government agencies and healthcare organizations. On the Surveys on Patient Safety Culture® (SOPS®), a “patient safety event” is defined as “any type of healthcare-related error, mistake, or incident, regardless of whether or not it results in patient harm.”

Provider refers to physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners who diagnose, treat patients, and prescribe medications.

Staff refers to all other individuals who work in the hospital but are not providers. Examples include medical assistants, administrative staff, housekeeping, and nutrition.

Response option 3 for the Work Stress/Burnout item is: “I am beginning to burn out and have one or more symptoms of burnout, e.g.; emotional exhaustion.”

Response option 4 for the Work Stress/Burnout item is: “The symptoms of burnout I am experiencing won’t go away. I think about work frustrations a lot.”

Response option 5 for the Work Stress/Burnout item is: “I feel completely burned out. I am at the point where I may need to seek help.”

De Vries E, Ramrattan M, Smorenburg S, Gouma D, Boermeester M. The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2008;17:216–23.

Article Google Scholar

JHA K, Larizgoitia I, Audera-Lopez C, Prasopa-Plaizier N, Waters H, Bates D. The global burden of unsafe medical care: analytic modelling of observational studies. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:809–15.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy; 1999.

Google Scholar

Bonner A, Castle N, Men A, Handler S. Certified nursing assistants’ perceptions of nursing home patient safety culture: is there a relationship to clinical outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:11–20.

Lawton R, O’Hara J, Sheard L, Reynolds C, Cocks K, Armitage G, Wright J. Can staff and patient perspectives on hospital safety predict harm-free care? An analysis of staff and patient survey data and routinely collected outcomes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:369–76.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mardon R, Khanna K, Sorra J, Dyer N, Famolaro T. Exploring relationships between hospital patient safety culture and adverse events. J Pat Saf. 2010;6:226–32.

Vikan M, Haugen A, Bjørnnes A, Valeberg B, Deilkås E, Danielsen S. The association between patient safety culture and adverse events–a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:1–27.

de Bienassis K, Kristensen S, Burtscher M, Brownwood I, Klazinga N. Culture as a cure: Assessments of patient safety culture in OECD countries. 2020.

Health & Safety Commission. ACSNI Human Factors Study Group third report: organising for safety. 1993.

Morello R, Lowthian J, Barker A, McGinnes R, Dunt D, Brand C. Strategies for improving patient safety culture in hospitals: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:11–8.

Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. https://www.ahrq.gov/sops/surveys/hospital/index.html . Accessed on 3rd March 2023.

Health worker safety: a priority for patient safety. Available online: health-worker-safety-charter-wpsd-17-september-2020-3-1.pdf (who.int). Accessed on. 3rd March 2023.

National Steering Committee for Patient Safety. National Action Plan to Advance Patient Safety ; Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Boston, MA, USA, 2020.

National Academy of Medicine. National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies. 2022. https://doi.org/10.17226/26744

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Injuries, illnesses, and fatalities, table R8 page. Survey of Occupational and Illness Data. Detailed Industry by Selected Events or Exposures (Rate).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Safe Patient Handling and Mobility (SPHM) Page.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Workbook for Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating a Sharps Injury Prevention Program.

Bahat H, Hasidov-Gafnim A, Youngster I, Goldman M, Levtzion-Korach O. The prevalence and underreporting of needlestick injuries among hospital workers: a cross-sectional study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2021:33, mzab009.

Boden L, Petrofsky Y, Hopcia K, Wagner G, Hashimoto D. Understanding the hospital sharps injury reporting pathway. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58:282–9.

Philips J. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1661–9.

The Joint Commission. Physical and verbal violence against health care workers. Sentin Event Alert. 2018;59:1–7.

Rangachari P, Woods J. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during COVID-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:42–67.

De Kock J, Latham H, Leslie S, Grindle M, Munoz S, Ellis L, Polson R, O’Malley C. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implicating for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:104.

Salazar de Pablo G, Vaquerizo-Serrano J, Catalan A, Arango C, Moreno C, Ferre F, Shin J, Sullivan S, Brondino N, Solmi M, et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physician and mental health of healthcare workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:48–57.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Stericycle. Key insights to Safeguard the Environment and the Environment of Care. Healthcare Workplace Safety Trend Report.

Riehle A, Braun B, Hafiz H. Improving patient and worker safety: exploring opportunities for synergy. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013;28:99–102.

Stone P, Harrison M, Feldman P, Linzer M, Peng T, Roblin D, Williams E. Organizational climate of staff working conditions and safety—an integrative model. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation (volume 2: concepts and methodology). 2005.

Mossburg S, Himmelfarb C. The association between professional burnout and engagement with patient safety culture and outcomes: a systematic review. J Pat Saf. 2021;17:e1307–19.

Kim S, Kitzmiller R, Baernholdt M, Lynn M, Jones C. Patient safety culture: the impact on workplace violence and health worker burnout. Work Health Saf. 2022;71:78–88.

Zabin L, Zaitoun R, Sweity E, Tantillo L. The relationship between job stress and patient safety culture among nurses: a systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:39.

SOPS Hospital Survey Version 2.0. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/sops/surveys/hospital/SOPS-Hospital-Survey-2.0-5-26-2021.pdf

SOPS Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set for the SOPS Hospital Survey. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/sops/surveys/hospital/workplace-safety/Workplace-Safety-Hospitals-2022-1215-ENGLISH_508.pdf . Accessed 31 January 2024.

Famolaro T, Yount N, Sorra J, Zebrak K, Gray L, Carpenter D, Caporaso A, Hare R, Fan L, Liu H. Pilot study results from the AHRQ surveys on Patient Safety Culture (SOPS) Workplace Safety Supplemental items for hospitals. 22 – 0008: AHRQ Publication No; 2021. Accessed 31 January 2024.

Sorra J, Famolaro T, Yount N, Zebrak K, Caporaso A, Behm J, Development. Pilot Test, and Psychometric Analysis of the AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture (SOPS™) Hospital Survey Version 2.0. AHRQ Publication. 2018.

Zebrak K, Yount N, Sorra J, Famolaro T, Gray L, Carpenter D, Caporaso A. Development, pilot study, and psychometric analysis of the AHRQ surveys on patient safety culture™(SOPS®) workplace safety supplemental items for hospitals. Int Journ Env Res Public Health. 2022;19:6815.

Article CAS Google Scholar

SOPS Hospital Survey Items and Composite Measures. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/sops/surveys/hospital/hospitalsurvey2-items.pdf . Accessed 31 January 2024.

Sorra J, Famolaro T, Dyer N, Nelson D, Khanna K. Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: 2008 comparative database report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Publication No; 2008. pp. 08–0039.

Menard S. Applied logistic regression analysis. Sage; 2002.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc: Ser B (Methodol). 1995;57:289–300.

Sexton B, Sharek P, Thomas E, Gould J, Nisbet C, Amspoker A, Kowalkowski M, Schwendimann R, Profit J. Exposure to Leadership WalkRounds in neonatal intensive care units is associated with a better patient safety culture and less caregiver burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:814–22.

Halbesleben J, Wakefield B, Wakefield D, Cooper L. Nurse burnout and patient safety outcomes: nurse safety perception versus reporting behavior. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30:560–77.

Profit J, Sharek P, Amspoker A, Kowalkowski M, Nisbet C, Thomas E, Chadwick W, Sexton B. Burnout in the NICU setting and its relation to safety culture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:806–13.

Kim S, Mary R, Baernholdt M, Kitzmiller R, Jones C. How does workplace violence-reporting culture affect workplace violence, nurse burnout, and patient safety? Jour Nurse Care Qual. 2023;38:11–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Sylvia Fisher from AHRQ provided helpful comments on the manuscript. We are also grateful to the hospitals and provider and staff respondents of the survey.

This research was funded by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Contract No. HHSP233201500026I/HHSP23337004T.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Westat, Rockville, MD, USA

Brandon Hesgrove, Katarzyna Zebrak, Naomi Yount & Joann Sorra

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD, USA

Caren Ginsberg

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BH, NY, and JS conceptualized the current study and drafted the manuscript. BH conducted all analyses and prepared all tables. KZ, NY, and JS reviewed and provided guidance on all analyses and tables prior to drafting the manuscript. BH, NY, JS, KZ, and CG reviewed and revised the manuscript for BMCHSR. BH, NY, JS, KZ, and CG have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Brandon Hesgrove .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study used hospital-level data aggregated from individual-level responses from the SOPS Hospital Survey 2.0. Informed consent language was included at the beginning of the SOPS web survey, along with Westat’s IRB contract information, but we received a waiver of written informed consent for the web survey. The informed consent language was “The survey is voluntary, but your feedback will help your hospital identify areas for patient safety and workplace safety improvement. If you do not wish to answer a question, you may leave it blank. Westat will keep your individual responses to this survey confidential. Only group results will be reported.”

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CG from AHRQ reviewed and revised the manuscript. CG has a competing interest because she is employed by AHRQ which owns and creates the survey that is the data source for this manuscript. BH, KZ, JS, and NY do not have any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hesgrove, B., Zebrak, K., Yount, N. et al. Associations between patient safety culture and workplace safety culture in hospital settings. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 568 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10984-3

Download citation

Received : 30 August 2023

Accepted : 11 April 2024

Published : 02 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10984-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health care

- Workplace safety

- Patient safety

- Workforce safety

- Safety culture

- Organizational culture

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia