- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- United States

AD Classics: Stahl House / Pierre Koenig

- Written by Andrew Kroll

- Architects: Pierre Koenig

- Year Completion year of this architecture project Year: 1959

- Photographs Photographs: Flickr User: dalylab

Text description provided by the architects. The Case Study House Program produced some of the most iconic architectural projects of the 20th Century, but none more iconic than or as famous as the Stahl House, also known as Case Study House #22 by Pierre Koenig. The modern residence overlooks Los Angeles from the Hollywood Hills. It was completed in 1959 for Buck Stahl and his family.

Buck Stahl had envisioned a modernist glass and steel constructed house that offered panoramic views of Los Angeles when he originally purchased the land for the house in 1954 for $13,500. Stahl had originally begun to excavate and take on the duties of architect and contractor; it was not until 1957 when Stahl hired Pierre Koenig to take over the design of the family’s residence.

The two-bedroom, 2,200 square foot residence is a true testament to modernist architecture and the Case Study House Program. The program was set in place by John Entenza and sponsored by the Arts & Architecture magazine. The aim of the program was to introduce modernist principles into residential architecture, not only to advance the aesthetic, but to introduce new ways of life both in a stylistic sense and one that represented the lifestyles of the modern age.

Pierre Koenig was able to hone in on the vision of Buck Stahl and transform that vision into a modernist icon. The glass and steel construction is understandably the most identifiable trait of architectural modernism, but it is the way in which Koenig organized the spatial layout of the house taking the public and private aspects of the house into great consideration. As much as architectural modernism is associated with the materials and methods of construction, the juxtaposition of program and organization are important design principles that evoke utilitarian characteristics.

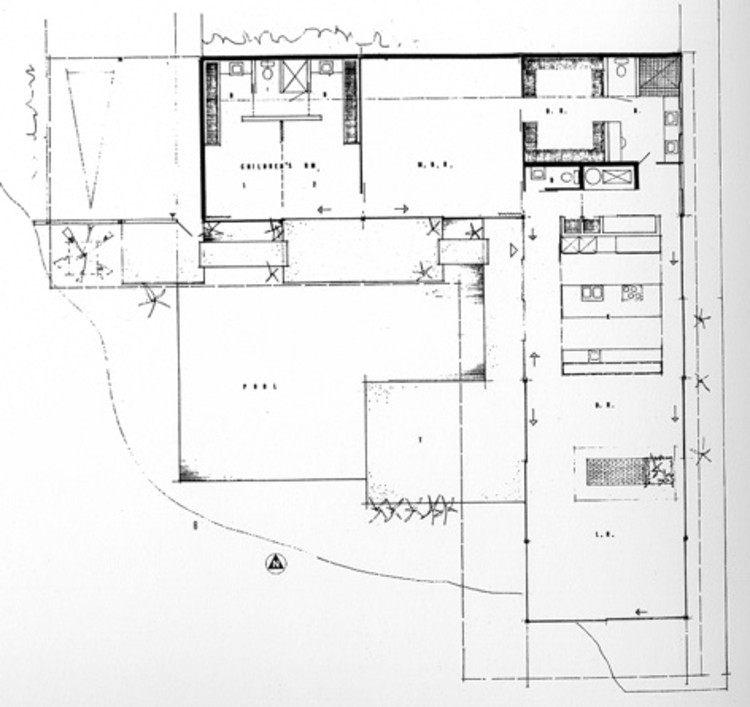

The house is “L” shaped in that the private and public sectors are completely separated save for a single hallway that connects the two wings. Compositionally adjacent is the swimming pool that one must cross in order to get into the house; it is not only a spatial division of public and private but its serves as the interstitial space that one must pass through in order to experience the panoramic views.

The living space of the house is set back behind the pool and is the only part of the house that has a solid wall, which backs up to the carport and the street. The entire house is understood to be one large viewing box that captures amazing perspectives of the house, the landscape, and Los Angeles.

Oddly enough, the Stahl house was fairly unknown and unrecognized for its advancement of modern American residential architecture, until 1960 when Julius Shulman captured the pure architectural essence of the house. It was the night shot of two women sitting in the living room overlooking the bright lights of the city of Los Angeles.

That photo put the Stahl House on the architectural radar as being an architectural gem hidden up in the Hollywood Hills.

The Stahl House is still one of the most visited and admired buildings today. It has undergone many interior transformations, so you will not find the same iconic 1960s furniture, but the architecture, the view, and the experience still remain. You can make reservations and a small fee with the Stahl family, and even get a tour with Buck Stahl’s wife, Carlotta, or better recognized as Mrs. Stahl.

This building is part of our Architecture City Guide: Los Angeles . Check all the other buildings on this guide right here.

Project gallery

Materials and Tags

- Sustainability

世界上最受欢迎的建筑网站现已推出你的母语版本!

想浏览archdaily中国吗, you've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

Check the latest Bistro Tables

Check the latest Dining Tables

- Entertainment

- Here’s the Story Behind Netflix’s Latest True Crime Docuseries <i>The Staircase</i>

Here’s the Story Behind Netflix’s Latest True Crime Docuseries The Staircase

N etflix‘s newest docuseries, The Staircase , dives into the twisty case of Michael Peterson, a novelist who was convicted in 2003 of murdering his wife, Kathleen Peterson, after she was found unconscious at the bottom of a staircase in their home.

The series has consumed director Jean-Xavier de Lestrade’s life for the last 15 years. De Lestrade first debuted the series in 2004, with eight episodes that closely followed Peterson, his family and defense team as they prepared for and went through the murder trial (an abbreviated version aired on ABC’s Primetime that year). He followed up with two more episodes in 2013, after Peterson was released from prison pending a retrial.

Now, de Lestrade is closing out The Staircase series on Netflix with the addition of three new episodes that document Peterson’s last trial and where he is today.

And after all that time, de Lestrade tells TIME he’s not sure whether Peterson is innocent or guilty.

“Michael Peterson himself is a very strange, very complex character,” de Lestrade said. “Of course, the man I spent many days, weeks, months and years with — the man I know, it’s like it’s not possible that he’s capable of killing someone in that way. But human beings are so strange and you never know.”

De Lestrade initially thought he’d tell Peterson’s story as a two-hour movie for HBO, as a followup of sorts to his Oscar-winning documentary Murder on a Sunday Morning , which covered the case of a poor black teenager who was wrongfully accused of killing a woman. He sought out Peterson — a wealthy, white man highly regarded in the public eye — to show how the justice system can upend anyone’s life, and soon had enough information to make a multi-part series instead.

De Lestrade landed on Peterson’s case after reviewing about 400 criminal cases. There was just something about Peterson that piqued his interest, de Lestrade said.

“When he was talking about Kathleen, I really felt that he was very sincere about their relationship, about the love they shared,” he said. “But at the same time, I kind of formed an intuition that there was something else. I’m not saying he was guilty, but I had a feeling there was something else.”

Peterson’s nearly two-decade long battle with the justice system started in 2001, when he placed a frantic 911 call, during which Peterson said he found his wife unconscious at the bottom of a staircase at their North Carolina home. He has maintained that Kathleen Peterson slipped on the stairs and fell to her death after drinking wine and taking valium earlier in the evening. Authorities, however, found the amount of blood spilled on the stairs suspicious. Focus quickly shifted to Peterson, who was the only one at home at the time of her death.

Further probing into Peterson brought up two pieces of information that prosecutors used against him during his trial. The first, it emerged that Peterson was bisexual and had carried on relationships with men outside of his marriage. While he claimed that Kathleen knew about and accepted his other relationships, prosecutors said during the trial that she had discovered it recently and confronted him on the night of her death.

The way de Lestrade sees it, had Peterson’s sexuality not come up, the prosecution may not have gone after him at all.

“For them, it was clear that was the motive of the killing,” he said. “They have always thought that Kathleen discovered that night the emails on his desk, that they had an argument about that, that he lost his temper and hit her.”

The second piece of information that investigation uncovered was that a close family friend Elizabeth Ratliff, whose daughters were later raised by the Petersons, had been found dead at the bottom of a staircase years before Kathleen Peterson died. During Peterson’s trial, her body was exhumed and a new autopsy determined her death was a homicide as well.

Peterson was convicted in 2003 of beating his wife to death and sentenced to life in prison. Eight years later, he was released on house arrest after a judge found that the blood analyst who had provided essential evidence in the case against Peterson had given misleading and false testimony about the bloodstain evidence. The final three episodes of The Staircase catch up with Peterson in his life outside of prison before he entered an Alford plea in 2017. Under the plea, Peterson is free as as a convicted felon after pleading guilty to murdering his wife.

Taken as a whole, with all 13 episodes available together on Netflix for the first time ever, the series paints a grim portrait of the criminal justice system. De Lestrade’s interest was never in the questioning Peterson’s guilt — his intent was to paint a broad picture of how Peterson would be treated inside the system until his final plea deal.

While he’s not convinced of Peterson’s innocence, de Lestrade said the process of making the series made it clear to him that Peterson did not receive a fair trial. Peterson was the only suspect they were interested in, he said. No matter how much money a person has, it’s tough to fight a whole system.

“Even when you have thousands of dollars to defend yourself and you have a smart lawyer, you have to get very lucky to get out,” he said. “And it took 15 years.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Mahita Gajanan at [email protected]

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Story of Genie Wiley

What her tragic story revealed about language and development

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Who Was Genie Wiley?

Why was the genie wiley case so famous, did genie learn to speak, ethical concerns.

While there have been a number of cases of feral children raised in social isolation with little or no human contact, few have captured public and scientific attention, like that of Genie Wiley.

Genie spent almost her entire childhood locked in a bedroom, isolated, and abused for over a decade. Her case was one of the first to put the critical period theory to the test. Could a child reared in utter deprivation and isolation develop language? Could a nurturing environment make up for a horrifying past?

In order to understand Genie's story, it is important to look at what is known about her early life, the discovery of the abuse she had endured, and the subsequent efforts to treat and study her.

Early Life (1957-1970)

Genie's life prior to her discovery was one of utter deprivation. She spent most of her days tied naked to a potty chair, only able to move her hands and feet. When she made noise, her father would beat her. The rare times her father did interact with her, it was to bark or growl. Genie Wiley's brother, who was five years older than Genie, also suffered abuse under their father.

Discovery and Study (1970-1975)

Genie's story came to light on November 4, 1970, in Los Angeles, California. A social worker discovered the 13-year old girl after her mother sought out services for her own health. The social worker soon discovered that the girl had been confined to a small room, and an investigation by authorities quickly revealed that the child had spent most of her life in this room, often tied to a potty chair.

A Genie Wiley documentary was made in 1997 called "Secrets of the Wild Child." In it, Susan Curtiss, PhD, a linguist and researcher who worked with Genie, explained that the name Genie was used in case files to protect the girl's identity and privacy.

The case name is Genie. This is not the person's real name, but when we think about what a genie is, a genie is a creature that comes out of a bottle or whatever but emerges into human society past childhood. We assume that it really isn't a creature that had a human childhood.

Both parents were charged with abuse , but Genie's father died by suicide the day before he was due to appear in court, leaving behind a note stating that "the world will never understand."

The story of Genie's case soon spread, drawing attention from both the public and the scientific community. The case was important, said psycholinguist and author Harlan Lane, PhD, because "our morality doesn’t allow us to conduct deprivation experiments with human beings; these unfortunate people are all we have to go on."

With so much interest in her case, the question became what should be done to help her. A team of psychologists and language experts began the process of rehabilitating Genie.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) provided funding for scientific research on Genie’s case. Psychologist David Rigler, PhD, was part of the "Genie team" and he explained the process.

I think everybody who came in contact with her was attracted to her. She had a quality of somehow connecting with people, which developed more and more but was present, really, from the start. She had a way of reaching out without saying anything, but just somehow by the kind of look in her eyes, and people wanted to do things for her.

Genie's rehabilitation team also included graduate student Susan Curtiss and psychologist James Kent. Upon her initial arrival at UCLA, Genie weighed just 59 pounds and moved with a strange "bunny walk." She often spat and was unable to straighten her arms and legs. Silent, incontinent, and unable to chew, she initially seemed only able to recognize her own name and the word "sorry."

After assessing Genie's emotional and cognitive abilities, Kent described her as "the most profoundly damaged child I've ever seen … Genie's life is a wasteland." Her silence and inability to use language made it difficult to assess her mental abilities, but on tests, she scored at about the level of a 1-year-old.

Genie Wiley's Rehabilitation and the Forbidden Experiment

She soon began to rapidly progress in specific areas, quickly learning how to use the toilet and dress herself. Over the next few months, she began to experience more developmental progress but remained poor in areas such as language. She enjoyed going out on day trips outside of the hospital and explored her new environment with an intensity that amazed her caregivers and strangers alike.

Curtiss suggested that Genie had a strong ability to communicate nonverbally , often receiving gifts from total strangers who seemed to understand the young girl's powerful need to explore the world around her.

Psychiatrist Jay Shurley, MD, helped assess Genie after she was first discovered, and he noted that since situations like hers were so rare, she quickly became the center of a battle between the researchers involved in her case. Arguments over the research and the course of her treatment soon erupted. Genie occasionally spent the night at the home of Jean Butler, one of her teachers.

After an outbreak of measles, Genie was quarantined at her teacher's home. Butler soon became protective and began restricting access to Genie. Other members of the team felt that Butler's goal was to become famous from the case, at one point claiming that Butler had called herself the next Anne Sullivan, the teacher famous for helping Helen Keller learn to communicate.

Genie was partially treated like an asset and an opportunity for recognition, significantly interfering with their roles, and the researchers fought with each other for access to their perceived power source.

Eventually, Genie was removed from Butler's care and went to live in the home of psychologist David Rigler, where she remained for the next four years. Despite some difficulties, she appeared to do well in the Rigler household. She enjoyed listening to classical music on the piano and loved to draw, often finding it easier to communicate through drawing than through other methods.

After Genie was discovered, a group of researchers began the process of rehabilitation. However, this work also coincided with research to study her ability to acquire and use language. These two interests led to conflicts in her treatment and between the researchers and therapists working on her case.

State Custody (1975-Present)

NIMH withdrew funding in 1974, due to the lack of scientific findings. Linguist Susan Curtiss had found that while Genie could use words, she could not produce grammar. She could not arrange these words in a meaningful way, supporting the idea of a critical period in language development.

Rigler's research was disorganized and largely anecdotal. Without funds to continue the research and care for Genie, she was moved from the Riglers' care.

In 1975, Genie returned to live with her birth mother. When her mother found the task too difficult, Genie was moved through a series of foster homes, where she was often subjected to further abuse and neglect .

Genie’s situation continued to worsen. After spending a significant amount of time in foster homes, she returned to Children’s Hospital. Unfortunately, the progress that had occurred during her first stay had been severely compromised by the subsequent treatment she received in foster care. Genie was afraid to open her mouth and had regressed back into silence.

Genie’s birth mother then sued the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles and the research team, charging them with excessive testing. While the lawsuit was eventually settled, it raised important questions about the treatment and care of Genie. Did the research interfere with the girl's therapeutic treatment?

Psychiatrist Jay Shurley visited her on her 27th and 29th birthdays and characterized her as largely silent, depressed , and chronically institutionalized. Little is known about Genie's present condition, although an anonymous individual hired a private investigator to track her down in 2000 and described her as happy. But this contrasts with other reports.

Genie Wiley Today

Today, Genie Wiley's whereabouts are unknown; though, if she is still living, she is presumed to be a ward of the state of California, living in an adult care home. As of 2024, Genie would be 66-67 years old.

Part of the reason why Genie's case fascinated psychologists and linguists so deeply was that it presented a unique opportunity to study a hotly contested debate about language development.

Essentially, it boils down to the age-old nature versus nurture debate. Does genetics or environment play a greater role in the development of language?

Nativists believe that the capacity for language is innate, while empiricists suggest that environmental variables play a key role. Nativist Noam Chomsky suggested that acquiring language could not be fully explained by learning alone.

Instead, Chomsky proposed that children are born with a language acquisition device (LAD), an innate ability to understand the principles of language. Once exposed to language, the LAD allows children to learn the language at a remarkable pace.

Critical Periods

Linguist Eric Lenneberg suggests that like many other human behaviors, the ability to acquire language is subject to critical periods. A critical period is a limited span of time during which an organism is sensitive to external stimuli and capable of acquiring certain skills.

According to Lenneberg, the critical period for language acquisition lasts until around age 12. After the onset of puberty, he argued, the organization of the brain becomes set and no longer able to learn and use language in a fully functional manner.

Genie's case presented researchers with a unique opportunity. If given an enriched learning environment, could she overcome her deprived childhood and learn language even though she had missed the critical period?

If Genie could learn language, it would suggest that the critical period hypothesis of language development was wrong. If she could not, it would indicate that Lenneberg's theory was correct.

Despite scoring at the level of a 1-year-old upon her initial assessment, Genie quickly began adding new words to her vocabulary. She started by learning single words and eventually began putting two words together much the way young children do. Curtiss began to feel that Genie would be fully capable of acquiring language.

After a year of treatment, Genie started putting three words together occasionally. In children going through normal language development, this stage is followed by what is known as a language explosion. Children rapidly acquire new words and begin putting them together in novel ways.

Unfortunately, this never happened for Genie. Her language abilities remained stuck at this stage and she appeared unable to apply grammatical rules and use language in a meaningful way. At this point, her progress leveled off and her acquisition of new language halted.

While Genie was able to learn some language after puberty, her inability to use grammar (which Chomsky suggests is what separates human language from animal communication) offers evidence for the critical period hypothesis.

Of course, Genie's case is not so simple. Not only did she miss the critical period for learning language, but she was also horrifically abused. She was malnourished and deprived of cognitive stimulation for most of her childhood.

Researchers were also never able to fully determine if Genie had any pre-existing cognitive deficits. As an infant, a pediatrician had identified her as having some type of mental delay. So researchers were left to wonder whether Genie had experienced cognitive deficits caused by her years of abuse or if she had been born with some degree of intellectual disability.

There are many ethical concerns surrounding Genie's story. Arguments among those in charge of Genie's care and rehabilitation reflect some of these concerns.

"If you want to do rigorous science, then Genie's interests are going to come second some of the time. If you only care about helping Genie, then you wouldn't do a lot of the scientific research," suggested psycholinguist Harlan Lane in the NOVA documentary focused on her life.

In Genie's case, some of the researchers held multiple roles of caretaker-teacher-researcher-housemate. which, by modern standards, we would deem unethical. For example, the Riglers benefitted financially by taking Genie in (David received a large grant and was released from certain duties at the children's hospital without loss of pay). Butler also played a role in removing Genie from the Riglers' home, filing multiple complaints against him.

While Genie's story may be studied for its implications in our understanding of language acquisition and development, it is also a case that will continue to be studied over its serious ethical issues.

"I think future generations are going to study Genie's case not only for what it can teach us about human development but also for what it can teach us about the rewards and the risks of conducting 'the forbidden experiment,'" Lane explained.

Bottom Line

Genie Wiley's story perhaps leaves us with more questions than answers. Though it was difficult for Genie to learn language, she was able to communicate through body language, music, and art once she was in a safe home environment. Unfortunately, we don't know what her progress could have been had adequate care not been taken away from her.

Ultimately, her case is so important for the psychology and research field because we must learn from this experience not to revictimize and exploit the very people we set out to help. This is an important lesson because Genie's original abuse by her parents was perpetuated by the neglect and abandonment she faced later in her life. We must always strive to maintain objectivity and consider the best interest of the subject before our own.

Frequently Asked Questions

Genie, now in her 60s, is believed to be living in an adult care facility in California. Efforts by journalists to learn more about her location and current condition have been rejected by authorities due to confidentiality rules. Curtiss has also reported attempting to contact Genie without success.

Along with her husband, Irene Wiley was charged with abuse, but these charges were eventually dropped. Irene was blind and reportedly mentally ill, so it is believed that Genie's father was the child's primary caretaker. Genie's father, Clark Wiley, also abused his wife and other children. Two of the couple's children died in infancy under suspicious circumstances.

Genie's story suggests that the acquisition of language has a critical period of development. Her case is complex, however, since it is unclear if her language deficits were due to deprivation or if there was an underlying mental disability that played a role. The severe abuse she experienced may have also affected her mental development and language acquisition.

Collection of research materials related to linguistic-psychological studies of Genie (pseudonym) (collection 800) . UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

Schoneberger T. Three myths from the language acquisition literature . Anal Verbal Behav. 2010;26(1):107–131. doi:10.1007/bf03393086

APA Dictionary of Psychology. Language acquisition device . American Psychological Association.

Vanhove J. The critical period hypothesis in second language acquisition: A statistical critique and a reanalysis . PLoS One . 2013;8(7):e69172. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069172

Carroll R. Starved, tortured, forgotten: Genie, the feral child who left a mark on researchers . The Guardian .

James SD. Raised by a tyrant, suffering a sibling's abuse . ABC News .

NOVA . The secret of the wild child [transcript]. PBS,

Pines M. The civilizing of Genie. In: Kasper LF, ed., Teaching English Through the Disciplines: Psychology . Whittier.

Rolls G. Classic Case Studies in Psychology (2nd ed.). Hodder Arnold.

Rymer R. Genie: A Scientific Tragedy. Harper-Collins.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Case Study House Program

The case study house program: origins, meanings, and protagonists, on the participation of northern california architects to the case study house program.

________________________________________

Case Study House #3

Information Description Plan Photos Architect’s Biography

Case Study House #19

Case study house #26.

Information Description Plans Photos Architect’s Biography

Case Study House #27

References & further reading, bay area architects’ designs for the, case study house program, 1949 – 1963.

By Pierluigi Serraino

The Case Study House program and the magazine Arts and Architecture are two inseparable twins in the historical narratives of California Modernism in its post-war phase. Common denominator of both was John Entenza (1905-1984), as editor from 1940 to 1962 of the magazine California Arts and Architecture, a title he changed in 1945 to Arts and Architecture, gave an international manner — both in terms of its compellingly lanky graphics and its cerebral content — to what had been mostly a regional periodical of limited distribution. Both the magazine and the Case Study House Program he masterminded hinged upon the recognition that the architecture of his time was rooted in technology, a symbolic source of its outer expression in the public realm.

The long span, steel, joinery, plywood, modularity, open plan, car mobility, aluminum, and glazing systems, were the tools and the lexicon of the post-war architect and the citizen of a technological society. For Entenza, the environmental habitat of California had to arise from the civilian application of the radical innovations in mechanical systems, new materials, and building science advancements gained during the World War II, especially because of the military industry’s major presence in California.

The Case Study House program started as Entenza’s personal project, partially financed through his own resources, that lasted two decades. This initiative was the game-changer in the authoritative aura that California Modernism acquired worldwide. Entenza led the program from 1945 to 1962 till he moved to Chicago to head the Graham Foundation. David Travers continued it from 1962 until its end in 1966. They both handpicked the architects that were going to be included in the program, absent of a truly objective criteria or checklist. While Entenza wrote the program’s manifesto himself and published it, the houses and architects chosen for inclusion are an eclectic mix of design expressions.

While most of the built (and unbuilt) residential projects of the Case Study House program are located in Southern California, the design community behind this renown cultural initiative is far from regional. In fact, the roaster of architects Entenza and Travers selected during their respective tenure offers a revealing picture of both the composite nature of signatures called to fulfill the promises of the January 1st , 1945, manifesto and of what flavor of modernism was being disseminated for the post-war home.

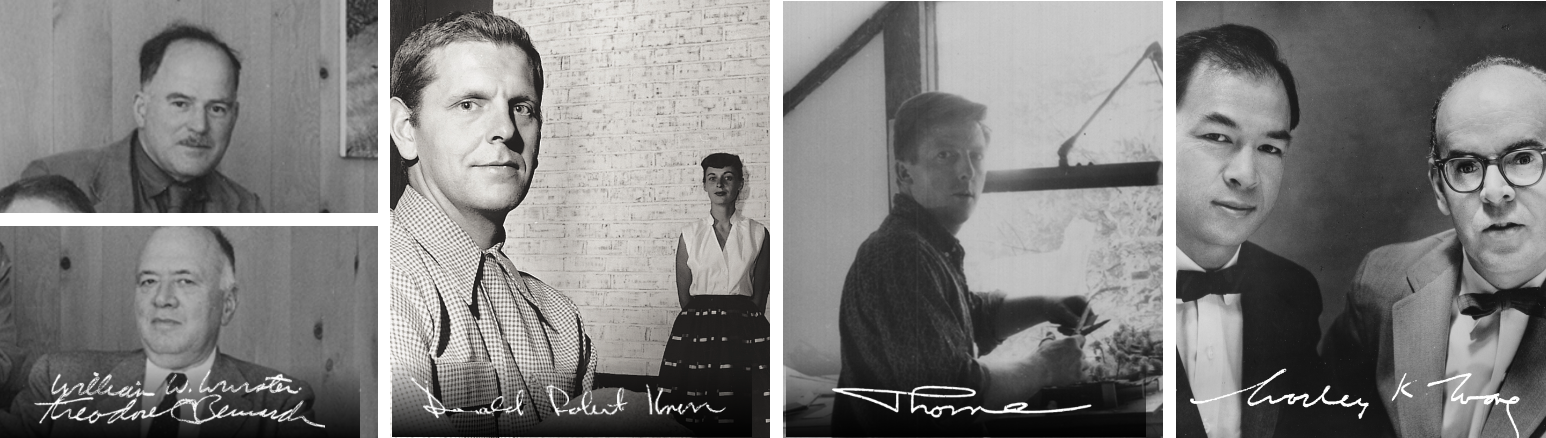

Some household names are from California- William Wurster from Stockton, Ray Kaiser from Sacramento, Pierre Koenig from San Francisco- as well as some lesser-known, such as Ed Killingsworth. John Rex, Worley Wong, and Calvin Straub, among others. A sizeable group of CSH architects was from out of state and had a cultural connection with the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, the legendary design school founded by Eliel Saarinen. From that milieu, the list is truly impressive: Charles Eames, Eero Saarinen, Ralph Rapson, Don Knorr. Others were from other parts of the country and landed either for family reasons or for college to Southern California. Additionally, others

came from Europe, most notably Richard Neutra from Vienna, Julius Ralph Davidson from Berlin, and Raphael Soriano from Rhodes, Greece. In this eclectic mix, various gradations of common themes- relationship with WWII technology, and material, open planning, one-level single-family homes, and an overall permeable relationship between indoor and outdoor, found specific manifestations in the talent of these creatives. These prototypes for living were conceived as models to shape much of post-war living for present and future generations.

Four teams of Bay Area architects were involved in the CSH Program. Under the Entenza’s era, there was the now-demolished CSH #3 in Los Angeles designed and built in 1945 by William Wurster and Theodore Bernardi and the unbuilt CSH #19 by Don Knorr for a site in the San Francisco South Bay in 1957. During the Traver’s lead, Beverley David Thorne’s CSH #26 was realized in 1962 in San Rafael, whereas CSH #27 by Campbell & Wong, in association with Don Allen Fong, of 1963 for a site in Smoke Rise, New Jersey, remained on paper. These Bay Area contributions have been intermittently acknowledged in the publications surrounding this one-of-a-kind initiative.

Yet, they provide documentary evidence of the commitment of the local community of designers to offering updated architectural propositions consistent with the changing needs of the California, and American, post-war society.

Past Exhibitions

Architecture + the City Festival

Whitney Young Jr.

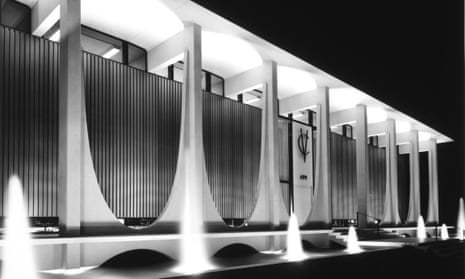

Julius Shulman’s Case Study House #22

The Greatest American Architectural Photographer of the 20th Century

Julius Shulman is often considered the greatest American architectural photographer of the 20th century. His photography shaped the image of South Californian lifestyle of midcentury America. For 70 years, he created on of the most comprehensive visual archives of modern architecture, especially focusing on the development of the Los Angeles region. The designs of some of the world’s most noted architectures including Richard Neutra, Ray Eames and Frank Lloyd Wright came to life though his photographs. To this day, it is through Shulman’s photography that we witness the beauty of modern architecture and the allure of Californian living.

Neutra and Beyond

Born in 1910 in Brooklyn, Julius Shulman grew up in a small farm in Connecticut before his family moved to Los Angeles at the age of ten. While in Los Angeles, Shulman was introduced to Boy Scouts and often went hiking in Mount Wilson. This allowed him to organically study light and shadow, and be immersed in the outdoors. While in college between UCLA and Berkeley, he was offered to photograph the newly designed Kun House by Richard Neutra. Upon photographing, Shulman sent the six images to the draftsman who then showed them to Neutra. Impressed, Richard Neutra asked Shulman to photograph his other houses and went on to introduce him to other architectures.

The Case Study Houses

Julius Shulman’s photographs revealed the true essence of the architect’s vision. He did not merely document the structures, but interpreted them in his unique way which presented the casual residential elegance of the West Coast. The buildings became studies of light and shadow set against breathtaking vistas. One of the most significant series in Shulman’s portfolio is without a doubt his documentation of the Case Study Houses. The Case Study House Program was established under the patronage of the Arts & Architectue magazine in 1945 in an effort to produce model houses for efficient and affordable living during the housing boom generated after the Second World War. Southern California was used as the location for the prototypes and the program commissioned top architects of the day to design the houses. Julius Shulman was chosen to document the designs and throughout the course of the program he photographed the majority of the 36 houses. Shulman’s photography gave new meaning to the structures, elevating them to a status of international recognition in the realm of architecture and design. His way of composition rendered the structures as inviting places for modern living, reflecting a sense of optimism of modern living.

Case Study House #22

Case Study House #22, also known as the Stahl House was one of the designs Julius Shulman photographed which later become one of the most iconic of his images. Designed by architect Pierre Koenig in 1959, the Stahl House was the residential home of American football player C.H Buck Stahl located in the Hollywood Hills. The property was initially regarded as undevelopable due to its hillside location, but became an icon of modern Californian architecture. Regarded as one of the most interesting masterpieces of contemporary architecture, Pierre Koenig preferred merging unconventional materials for its time such as steel with a simple, ethereal, indoor-outdoor feel. Julius’s dramatic image, taking in a warm evening in the May of 1960, shows two young ladies dressed in white party dresses lounging and chatting. The lights of the city shimmer in the distant horizon matching the grid of the city, while the ladies sit above the distant bustle and chaos. Pierre Koenig further explains in the documentary titled Case Study Houses 1945-1966 saying;

“When you look out along the beam it carries your eye right along the city streets, and the (horizontal) decking disappears into the vanishing point and takes your eye out and the house becomes one with the city below.”

The Los Angeles Good Life

The image presents a fantasy and is a true embodiment of the Los Angeles good life. By situating two models in the scene, Shulman creates warmth, helping the viewer to imagine scale as well as how life would be like living in this very house. In an interview with Taina Rikala De Noriega for the Archives of American Art Shulman recalls the making of the photograph;

“ So we worked, and it got dark and the lights came on and I think somebody had brought sandwiches. We ate in the kitchen, coffee, and we had a nice pleasant time. My assistant and I were setting up lights and taking pictures all along. I was outside looking at the view. And suddenly I perceived a composition. Here are the elements. I set up the furniture and I called the girls. I said, ‘Girls. Come over sit down on those chairs, the sofa in the background there.’ And I planted them there, and I said, ‘You sit down and talk. I’m going outside and look at the view.’ And I called my assistant and I said, ‘Hey, let’s set some lights.’ Because we used flash in those days. We didn’t use floodlights. We set up lights, and I set up my camera and created this composition in which I assembled a statement. It was not an architectural quote-unquote “photograph.” It was a picture of a mood.”

Purity in Line and Design to Perfection

Shulman’s preference to shoot in black and white reduces the subject to its geometrical essence allowing the viewer to observe the reflections, shadows and forms. A Shulman signature, horizontal and vertical lines appear throughout the image to create depth and dimensional perspective. A mastery in composition, the photograph catches purity in line and design to perfection.

A Lifetime of Achievements

Julius Shulman retired from active architectural work in 1989, leaving behind an incredibly rich archive chronicling the development of modern living in Southern California. A large part of his archive resides at the Getty Museum in California. For the next twenty years he participated in major museum and gallery exhibitions around the world, and created numerous books by publishers such as Taschen and Nazraeli Press. Among his honors, Shulman is the only photographer to have been granted honorary lifetime membership in the American Institute of Architects. In 1998 he was given a lifetime achievement award by ICP. Julius passed away in 2009 in his home in Los Angeles.

Milton Greene's Marilyn Monroe – Ballerina Sitting

Simple pleasures: seeing the world through rose-tinted glasses, join our newsletter.

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in any emails.

Cookie banner

We use cookies and other tracking technologies to improve your browsing experience on our site, show personalized content and targeted ads, analyze site traffic, and understand where our audiences come from. To learn more or opt-out, read our Cookie Policy . Please also read our Privacy Notice and Terms of Use , which became effective December 20, 2019.

By choosing I Accept , you consent to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies.

Filed under:

Creating the iconic Stahl House

Two dreamers, an architect, a photographer, and the making of America’s most famous house

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/56342955/gri_2004_r_10_b190_f007_2980_17.0.jpg)

In 1953 a mutual friend introduced Clarence Stahl, better known as Buck, to Carlotta Gates. They met at the popular Mike Lyman’s Flight Deck restaurant, off Century Boulevard, which overlooked the runways at Los Angeles International Airport. Buck was 41 and Carlotta 24. The couple married a year later and remained together for more than 50 years, until Buck’s death in 2005.

Working with Pierre Koenig, an independent young architect whose primary materials were glass, steel, and concrete, the couple created perhaps the most widely recognized house in Los Angeles, and one of the most iconic homes ever built. No one famous ever lived in it, nor was it the site of a Hollywood scandal or constructed for a wealthy owner. It was just the Stahls’ dream home. And it almost did not come true.

As a newlywed, Carlotta moved into the house Buck was renting—the lower half of a two-story wood-frame house on Hillside Avenue in the Hollywood Hills, just west of Crescent Heights Boulevard and north of Sunset Boulevard. From the house, Buck and Carlotta looked across a ridge toward a promontory that drew their attention every morning and evening. As Carlotta explained during an interview with USC history professor Philip Ethington, this is how the dream of building their own home started: simply and incidentally. Although they felt emotionally and psychically drawn to the promontory, they did not have the financial means to buy the lot, even if it were available.

For months they looked intently across the ridge. Then, in May 1954, the couple decided “Let’s go over and see our lot. We’d already claimed it even though we’d never been here,” Carlotta told Ethington, adding, “And when we came up that day George Beha [the owner of the lot] was in from La Jolla. He and Buck talked, then, I would say an hour, hour and [a] half later, they shook hands. We bought the lot and he agreed to carry the mortgage.” They settled on a price of $13,500. At the end of their meeting, Buck gave Beha $100 as payment to make the agreement binding.

There were no houses along the hillside near the site that would become the Stahl House on Woods Drive, although the land was getting graded in anticipation of development. Richard D. Larkin, a real estate developer, acquired the lots on the ridge in a tax sale from the city of Los Angeles around 1958 and arranged to subdivide and grade them. The city hauled away the dirt without charge to use the decomposed granite for runway construction at LAX. In the process, the city made the road for Woods Drive.

The Stahls’ chance meeting with Beha abruptly made their vision more of a reality, but building was still a long way away. After nearly four years of mortgage payments to Beha, Buck prepared the lot for construction. He did this without having building specs, but knowing it would be necessary to shape the difficult hillside lot. In the first of many do-it-yourself accomplishments, he built up the edges to make the lot flat and level. To create a larger buildable area he laid the edge of the foundation with broken concrete, which was readily available at no cost from construction sites and provided Buck with flexibility for his layout. He could also lift and move the pieces without heavy equipment. He constructed a concrete wall and terracing with broken pieces of concrete. But he was told by architects and others that his effort would not improve the buildability of the property.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102365/gri_2004_r_10_b190_f006_2980_05.jpg)

The developer, Larkin, showed Buck how to lay out and stack the concrete, Buck recalled to Ethington. It was not a completely new concept, as photographer Julius Shulman, whose photograph of the Stahl House would later become internationally recognized, used broken concrete in the landscaping on his property. But Buck’s use was far more labor-intensive and consuming. On evenings and weekends he managed to pick up discarded concrete from construction sites around Los Angeles, asking the foremen if he could haul the debris away. He did this dozens of times before collecting enough for the concrete wall.

Buck used decomposed granite from the lot and surrounding area, instead of fresh cement, to fill in the gaps between the concrete pieces. The result was a solid form that remains intact and stable today, almost 60 years later. What had been the underlying layer for a man-made structure became the underlying layer for a new man-made structure—Buck’s layers of broken concrete added another facet to the topography of the house and the city, and this hands-on development of the lot connected the Stahls to the land and house.

As they completed their final monthly payments, Buck finished a scale model of their dream home, and the couple began to look for an architect. The central architectural feature of the model was a butterfly roof combined with flat-roofed areas. From the beginning, Buck and Carlotta envisioned a glass house without walls blocking the panoramic view.

Their frequent visits to the lot intensified their desire to build a home of their own design. Like an architect, Buck studied the composition of the land, the shape of the lot, the direction of light, and the best way to ensure the views. Perhaps most importantly, he considered the architectural style that would ideally highlight these qualities.

Carlotta told Ethington they decided to meet with three architects whose work they had seen in different publications: Craig Ellwood, Pierre Koenig, and one more whom she did not remember. She said Ellwood and the unidentified architect “came to the lot [and] said we were crazy. ‘You’ll never be able to build up here.’”

When Koenig visited the site with the Stahls, he and Buck “just clicked right away,” according to Carlotta. In the 1989 documentary The Case Study House Program, 1945-1966: An Anecdotal History & Commentary , Koenig recalled how Buck “wanted a 270-degree panorama view unobstructed by any exterior wall or sheer wall or anything at all, and I could do it.” The Stahls appreciated Koenig’s enthusiasm and willingness to work with them. They had a written agreement in November of 1957.

The massive spans of glass and the cantilevering of the structure, essential aspects of the design to Koenig, precluded traditional wood-frame house construction. To ensure the open floorplan, uninterrupted views, and the structure required to create those features, steel became inevitable. Steel would also offer greater stability than wood during an earthquake. The use of exposed glass, steel, and concrete was a functional and economic decision that defined the aesthetics of the house. In combination, these industrial materials were not then common choices in home construction, though they were materials Koenig used frequently. Exposing the material structure of the house illuminated its transparency as an indoor-outdoor living space.

Koenig kept the spirit of Buck’s model, but removed a key aspect: the butterfly roof. Koenig flattened the roof and removed the curves from Buck’s design, so the house consisted of two rectangular boxes that formed an L.

When he sited the house and drew his preliminary plans, Koenig aligned the house so that the roof and structural cantilever mirrored the grid-like arrangement of the streets below the lot. Once completed, the house visually extended into the Los Angeles cityscape. The symmetry enhanced the connection between the house and the land. In The Case Study House Program 1945-1966 documentary, Koenig says, “When you look out along the beams it carries your eye out right along the city streets, and the [horizontal] decking disappears into the vanishing point and takes your eye out and the house becomes one with the city below.”

With the design completed, the Stahls’ dream was closer to coming to life, but there were further obstacles. The unconventional design of the house and its hillside construction made it difficult to secure a traditional home loan; banks repeatedly turned down Buck because it was considered too risky. As Buck explained to Ethington, “Pierre [kept] looking [for financing] and he had his rounds of contacts.” Koenig was finally able to arrange financing for the Stahls through Broadway Federal Savings and Loan Association, an African-American-owned bank in Los Angeles.

Broadway Federal had one unusual condition for the construction loan: The Stahls were required to secure a second loan for the construction of a pool and would need another bank to finance it. They had had a yard in mind, but a pool would increase the overall cost of the home—for the bank, it added value to the property and made the loan less risky.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102373/gri_2004_r_10_b199_2980_02k.jpg)

After more searching, Buck found a lender for the pool construction so both projects could proceed. Broadway Federal loaned the Stahls $34,000. The second lender financed the pool at a cost of approximately $3,800.

Broadway Federal’s loan is ironic and extraordinary. Although it was not a reflection of the Stahls’ own values, the area that included their lot had legally filed Covenants, Conditions, and Restrictions from 1948 that indicated “the property shall not, nor shall any part thereof be occupied at any time by any person not of the Caucasian race, except that servants of other than the Caucasian race may be employed and kept thereon.” It was a discriminatory restriction against African Americans, and yet an African-American-owned bank made it possible for a Caucasian couple to build their home there.

When Pierre Koenig began work on the Stahl House, he was 32 years old and had built seven of the more than 40 projects he would design in his career. The Stahl House is the best known and is considered his masterwork, although Koenig considered the Gantert House (1981) in the Hollywood Hills the most challenging house he built. The long-term influence of the Stahl House is apparent in Gantert House and many of Koenig’s other projects.

Koenig built his first house in 1950—for himself—during his third year of architecture school at USC. It was a steel, glass, and cement structure. Although the architecture program had dropped its focus on Beaux Arts studies and modernism was coming to the fore, residential use of steel was not part of Koenig’s curriculum. But when he looked at the post-and-beam architecture then considered the standard of modern architecture, he felt the wood structures looked thin and fragile, and should be made of steel instead.

Koenig later told interviewer Michael LaFetra about a conversation with his instructor: “He said ‘No, you cannot use steel as an industrial material for domestic architecture. You cannot mix them up. The housewife won’t like [steel houses].’ The more he said I couldn’t do it, the more I wanted to do it. That’s my nature. He failed me. I got absolutely no help from him.”

But wartime production methods, particularly arc welding, were a source of inspiration for Koenig’s use of steel. Electric arc welding did not require bolts or rivets and instead created a rigid connection between beams and columns. Cross-bracing was not required, which opened greater possibilities: Aesthetically, it offered a streamlined look and allowed him to design a large open framework for unobstructed glass walls. The thin lines of the steel looked incidental compared to their strength.

His first house was originally designed as a wood building, but redesigned for steel construction. He commented years later that that was not the way to do it—he learned how to design for steel by taking an entirely new approach. There was little precedent to support his efforts: Such discoveries were an education for him, and he worked to resolve issues on his own. In Esther McCoy’s book Modern California Houses: Case Study Houses, 1945-1962 , Koenig declares, “Steel is not something you can put up and take down. It is a way of life.”

From then on, Koenig continued to develop his architectural vision—both pragmatic and philosophical. Prefabricated housing was a promising development following the war, but consumers found the homes’ cookie-cutter, invariable design unappealing. Koenig’s goal was to use industrialized components in different ways to create unique, innovative buildings using the same standard parts: endless variations with the core materials of glass, steel, and cement. Koenig’s intention, as captured in James Steel’s biography Pierre Koenig , “was to be part of a mechanism that could produce billions of homes, like sausages or cars in a factory.”

“The basic problem is whether the product is well designed in the first place,” Koenig further explained in a 1957 Los Angeles Times article by architectural historian Esther McCoy. “There are too many advantages to mass production to ignore it. We must accept mass production but we must insist on well-designed products.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102379/gri_2004_r_10_b190_f008_2980_24.jpg)

Reducing the number of parts and avoiding small parts were ways to reduce costs and streamline construction. In the case of the Stahl House, the efficiencies generated by the minimal-parts approach led to an inventory of fewer than 60 building components. In 1960, in an interview for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner , Koenig said:

“All I have done is to take what we know about industrial methods and bring it to people who would accept it. You can make anything beautiful given an unlimited amount of money. But to do it within the limits of economy is different. That’s why I never have steel fabricated especially to my design. I use only stock parts. That is the challenge—to take these common everyday parts and work them into an aesthetically pleasing concept.”

Although Koenig completed a plot plan for the Stahl House in January 1958, he did not submit blueprints to the city of Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety until that July. Due to the extensive use of steel and glass in a residential plan, combined with the hillside lot and dimensions and form that the department found irregular, the city did not consider the house up to code and would not approve construction. Instead they noted, “Board Action required to build on this site because of the extremely high steep slopes on the east and south sides.”

In a move typical of Koenig’s intellect and his ability to understand all details of construction, he prepared the technical drawings so he was able to discuss details with the planners. He spent several months explaining his design and material specifications to the city. Since they had not seen many plans for the extensive use of steel in home construction, the building officials asked him, “Why steel?”

In his interview with LaFetra, Koenig explained that he thought steel would last longer than wood and knew “building departments were not used to the ideas of modern architecture.” They would frown on “doing away with hip roof, shingles, you had to have a picket fence, window shutters.”

“The Building Department thought I was crazy,” Koenig said. “I can remember one of the engineers saying, ‘Why are you going to all this trouble? All you have to do is open up the code book and put down what’s in the code book. You could have a permit tomorrow.’ I asked myself, Why am I doing this?! I was motivated by some subconscious thing.” Koenig reduced the living room cantilever by 10 feet and removed the walkway around the house in order to move the plans forward.

He finally received approval in January 1959. Carlotta remembers, “One of the officials … said [there’ll] never be another house built like this ’cause they didn’t like the big windows. That was one of the things that bothered them more than anything, and the fact that we’re cantilevered.”

The city’s lengthy approval process contrasted with Koenig’s quick construction of the house. Due to its minimalist structural design and reduced number of building components compared to traditional wood construction, framing of the house was simplified. A crew of five men completed the job in one day.

The challenges of building were known, and they primarily related to the lot. “There’s very little land situated on this eagle nest high above Sunset Boulevard,” Koenig explained in the documentary film about the Case Study House Program. “So the swimming pool and the garage went on the best part, mainly because who wants to spend a lot of money supporting swimming pools and garages? And it’s very hard to support a pool on the edge of a cliff. The house it could handle. So the house is on the precarious edge.”

With the exception of the steel-frame fireplace (chimney and flue were prefabricated and brought to the site), Koenig used only two types of standard structural steel components: 12-inch beams and 4-inch H columns. The result is a profound demonstration of Koenig’s technical and aesthetic expertise with rigid-frame construction. The elimination of load-bearing walls on this scale represented the most advanced use of technology and materials for residential architecture ever.

Koenig’s success with steel-frame construction is partially due to William Porush, the structural engineer for the Stahl House. Porush engineered more than half of Koenig’s projects, beginning with Koenig’s first house in 1950.

A native of Russia, Porush emigrated to the U.S. in 1922 and graduated with a degree in civil engineering from the California Institute of Technology in 1926. After working for a number of firms in Los Angeles and later with the LA Department of Building and Safety during World War II, Porush opened his own office in 1946 and eventually designed his own post-and-beam house in Pasadena in 1956.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102383/gri_2004_r_10_b199_2980_09k.jpg)

The scale of his projects ranged from commercial buildings using concrete tilt-up construction in downtown Los Angeles to professional offices in Glendale, light industrial engineering, and a number of schools in Southern California—including traditional wood and brick, glass, and steel schools in Riverside.

Love midcentury homes?

Compare notes with other obsessives in our private Facebook group.

When Porush retired at 89 years old, his son Ted ran the practice for several years before retiring himself. Speaking of both his and his father’s experience working with Koenig in 2012, Ted said, “Koenig was quite devoted and always had something in mind all the time without being unreasonable or obstinate, really an artist perhaps,” and added that he and his father “welcomed Koenig’s engineering challenges—whether related to innovations, materials, or budget constraints.”

General contractor Robert J. Brady was the other key member of Koenig’s Stahl House crew. Brady gained industry experience running a construction business in Ojai, California, where he was a school teacher. This was the only time Brady and Koenig worked together, as Koenig was dissatisfied, he later wrote, with Brady’s management of the Stahl House, as indicated in a letter to Brady himself in the Pierre Koenig papers at the Getty Research Institute.

In 1957, Koenig approached Bethlehem Steel about the development of a program for architects using light-steel framing in home construction. At the time, Bethlehem Steel did not see a market or need to formalize a program. Residential use of steel, while known, was still very uncommon.

“The steel house is out of the pioneering stage, but radically new technologies are long past due,” Koenig explained in an interview with Esther McCoy. “Any large-scale experiment of this nature must be conducted by industry, for the architect cannot afford it. Once it is undertaken, the steel house will cost less than the wood house.”

By 1959, Bethlehem Steel saw how quickly the market was changing and started a Pacific Coast Steel Division in Los Angeles to work specifically with architects. The division then shared their preliminary specifications with Koenig for architecturally exposed steel and solicited his comments and opinions.

To introduce Bethlehem’s new marketing effort, they published a booklet in 1960, “The Steel-Framed House: A Bethlehem Steel Report Showing How Architects and Designers Are Making Imaginative Use of Light-Steel Framing In Houses.” Koenig’s Bailey House (CSH No. 21) and the Stahl House both appeared in the booklet. Bethlehem promoted Koenig’s architecture with Shulman photographs and accompanying text: “What could be more sensible than to make this magnificent view of Los Angeles a part of the house—to ‘paper the walls’ with it?” and “Problem Sites? Not with steel framing!” The brochure showed multiple views of the Stahl House.

For architects, having work published during this time led to recognition and often translated to future projects. Arts & Architecture magazine and its publisher John Entenza played an essential role in promoting Koenig’s architecture. Entenza conceived of the Case Study House Program in the months prior to the end of World War II, in anticipation of the demand for affordable, thoughtfully designed middle-class housing, and introduced it in the magazine’s January 1945 issue. The purpose of the program was to promote new ways of living based on advances in design, construction, building methods, and materials.

After the war, an impetus to produce new forms emerged. In architecture, that meant a move away from traditionally built homes and toward modern design. The postwar availability of industrial and previously restricted materials, especially glass, steel, and cement, offered architects freedom to pursue new ideas. In addition to materials, the modern approach in home design resulted in less formal floor plans that could offer continuity, ease of flow, multipurpose spaces, fewer interior walls, sliding glass walls and doors, entryways, and carports. Homes were generally built with a flat roof, which helped define a horizontal feel. Interior finishes were simple and unadorned, and there was no disguising of materials.

The absence of traditional details became part of the new aesthetic. Both exterior and interior structures were simplified. This all contributed to perhaps the most significant appeal of postwar architecture in Southern California: indoor-outdoor living. By physically, visually, and psychologically integrating the indoors and outdoors, it offered a new, casual way of life that more actively connected people to their environment. Combined with year-round mild weather, these new houses afforded a growing sense of independence and freedom of expression.

Arts & Architecture presented works-in-progress and completed homes throughout its pages, devoting more space in the magazine to the modern movement than other publications. Trends with finishes, built-ins, and low-cost materials spread across homes in Southern California after publication in Arts & Architecture . The magazine’s modern aesthetic extended across the country, where architects developed new solutions based on what they had seen in its pages. And since it reached dozens of countries, the international influence of California modernism through Entenza’s editorial eye was profound.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102411/gri_2004_r_10_b190_f006_2980_08.jpg)

The Case Study House Program provided a point of focus. As noted by Elizabeth Smith, art historian and museum curator, all 36 of the Case Study houses were featured in the magazine, although only 24 were built. With the exception of one apartment building, they were all single-family residences completed between 1945 and 1966.

“John Entenza’s idea was that people would not really understand modern architecture unless they saw it, and they weren’t going to see it unless it was built,” Koenig said in James Steel’s monograph. “[Entenza’s] talent was to promulgate ideas that many architects had at that time.”

In conjunction with the magazine, Entenza sponsored open houses at recently completed Case Study houses, giving visitors the opportunity to experience the modern aesthetic. Contemporary design pieces such as furniture, lamps, floor coverings, and decorative objects created a context for everyday living. The open houses took on a realistic dimension that generated a range of responses: “Oh, steel, glass and cement are cold.” “This is not homey.” “Could I live here?” “How would I live here?”

The program gave architects exposure and in many cases brought them credibility and a new clientele—although it was not a wealth-generating endeavor for the architects. For manufacturers and suppliers, it was a convenient way to receive publicity since people could see their products or services in use.

The Case Study House Program did not achieve Entenza’s goal: the development of affordable housing based on the design of houses in the program. None of the houses spurred duplicates or widespread construction of like-designed homes. The motivation from the building industry to apply the program’s new approaches was short-lived and not widely adopted.

Speaking many years later, Koenig stated in Steel’s monograph that “in the end the program failed because it addressed clients and architects, rather than contractors, who do 95 percent of all housing.” Instead, the known, accepted, and traditional design, methods of construction, and materials continued to prevail. Buyers still largely preferred conventional homes—a fact reinforced by the standard type of construction taught in many architecture schools during the postwar years.

However, today the program must be considered highly successful for its impact on residential architecture, and for initiating the California Modern Movement. The program influenced architects, designers, manufacturers, homeowners, and future home buyers. As McCoy reported, “The popularity of the Case Studies exceeded all expectations. The first six houses to be opened [built between 1946 and 1949] received 368,554 visitors.” The houses in the program, and their respective architects, now characterize their architectural era, representing the height of midcentury modern residential design.

The Stahl House became Case Study House No. 22 in the most informal way. With the success of Koenig’s Bailey House (CSH No. 21), Entenza told Koenig if he had another house for the program, to let him know. Koenig told him about his next project, the Stahl House.

In April 1959, months before construction started, Entenza and the Stahls signed an exclusive agreement indicating the house would become known as Case Study House No. 22 and appear in Arts & Architecture magazine. This also meant the house would be made available for public viewings over eight consecutive weekends and Entenza had the rights to publish photographs and materials in connection with the house. Additionally, he had approval of the furnishings. (He included an option for the Stahls to buy any or all of the furnishings at a discount.)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102405/gri_2004_r_10_b199_2980_13k.jpg)

By agreeing to make their house CSH No. 22, the Stahls were making their dream home more affordable. Equipment and material suppliers sold at cost in exchange for advertising space in the magazine. The arrangement gave Koenig the opportunity to negotiate further with vendors, since he was likely to use them in the future. Buck estimated in his interview with Ethington that it “ended up saving us conservatively $10,000 or $15,000” on the construction.

The house was featured in Arts & Architecture four times between May 1959 and May 1960, in articles documenting its progress and completion.

Arts & Architecture only ended up opening the house for public viewings on four weekends, from May 7 to May 29, 1960. The showings were well attended, and the shorter schedule meant the Stahls could move into the house sooner.

The Stahl House is a 2,200-square-foot home with two bedrooms and two bathrooms, built on an approximately 12,000-square-foot lot.

Construction began in May 1959 and was completed a year later, in May 1960. The pre-construction built estimate was $25,000, with Koenig to receive his usual 10 percent architect’s fee. His agreement with the Stahls additionally provided him 10 percent of any savings he secured on construction materials. The budget for the house was revised to $34,000, but Koenig’s fee of $2,500 did not change.

The final cost was over $15 per square foot—notably more than the average cost per square foot of $10 to $12 in Southern California at the time.

During its lifetime, the Stahl House has had very few modifications. For a short time, AstroTurf surrounded the pool area to serve as a lawn and make the area less slippery for the Stahls’ three children. There have been minor kitchen remodels with necessary updates to appliances. The kitchen cabinets, which were originally dark mahogany, were replaced with matched-grain white-oak cabinets due to fading caused by heavy exposure to sunlight. A catwalk along the outside of the living room, on the west side, was added to make it easier to wash the windows. Stones were applied to the fireplace, which was originally white-painted gypsum board with a stone base. A stone planter was also added to match the base. The pool was converted to solar heat.

These changes maintain the spirit of the house. Perhaps without effort, Koenig activated what architect William Krisel termed “defensive architecture”: building to preempt alterations and keep a structure as originally designed. Koenig's original steel design, comprehending potential earthquake risk, remains superior to traditional building materials.

The Stahl House has served as the setting for dozens of films, television shows, music videos, and commercials. Its appearances in print advertisements number in the hundreds. By Koenig’s count, the house can be seen in more than 1,200 books.

At times, the house has played a leading role. Its first commercial use was in 1962, when the Stahls made the house available for the Italian film Smog not long after they moved in.

Movies featuring the Stahl House

The First Power (1990)

The Marrying Man (1991)

Corina Corina (1994)

Playing By Heart (1998)

Why Do Fools Fall In Love (1998)

Galaxy Quest (1999)

The Thirteenth Floor (1999)

Nurse Betty (2000)

Where the Truth Lies (2005)

In Los Angeles magazine, years later, Carlotta recalled the production: “One of the days they were shooting, the view was too clear, so they got spray and smogged the windows.” The Stahls grew to accept such requests, and the result has been decades of commercial use.

Koenig explained its attraction in the New York Times : “The relationship of the house to the city below is very photogenic … the house is open and has simple lines, so it foregrounds the action. And it’s malleable. With a little color change or different furniture, you can modify its emotional content, which you can’t do in houses with a fixed mood and image.”

This versatility offers a wide range of settings, from kitsch to urbane, comedy to drama. The house has also been rendered in 3D software for various architectural studies and appears in the game The Sims 3 , perhaps the most revealing proof of its demographic reach.

In nearly all appearances, the Stahl House conveys a sense of livability that is aspirational while remaining accessible. It reflects Koenig’s skillful architectural purpose. The architect is invisible by design. Understandably, Koenig was very pleased to see the frequent and varied use of the Stahl House. However, as he said in the New York Times , “My gripe is the movies use [houses] as props but never list the architect in the credits.” He added, “Architects, of course, get no residuals from it. The Stahls paid off the original $35,000 mortgage for the house and pool in a couple of years through location rentals, and now the house is their entire income.”

Once Buck retired in 1978, renting the house for commercial use became an especially helpful way to supplement their income. Today the family offers tours and rents the house for events and media activities. They also honor Carlotta’s restriction, noted in a 2001 interview with Los Angeles magazine: “I will not allow nudity. My Case Study House is not going to be associated with that.”

“Julius Shulman called. ... He’ll be there tonight. Call him at 6 p.m. and make arrangements for tonite. By then he’d appreciate it if you would know if Stahl could put off moving in until pictures are shot.”

This ordinary call logged in Koenig’s office journal eventually led to the creation of one of the most iconic photographs of the postwar modern era.

However, delays with completing interior details almost prevented Shulman from photographing the house and meeting his publication deadline, even after he negotiated with his editor to change it several times. The potential of missing an opportunity to promote the house frustrated Koenig. “As you know we were supposed to shoot Monday [April 18, 1960],” he wrote to his general contractor, Robert Brady:

“The deadline has been changed once but it is impossible to change it again. The die is set. Mr. Van Keppel is waiting to move furniture in. Shulman comes by the job every day to see when he can shoot. Mr. Entenza is shouting for photos so he can print the next issue. The president of Bethlehem is supposed to visit the finished house this Friday [April 22]. There is to be a press conference this week-end. Not to mention Mr. Stahl. This will give you some idea of the pressure being put on.”

After Brady completed the finishing work, and months after it was originally scheduled, Shulman photographed the house over the course of a week. There was still construction material in the carport, and the master bathroom was not complete.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9102435/gri_2004_r_10_b199_2980_20k.jpg)

The color image of the two women sitting in the house with the city lights at night first appeared on the cover of the July 17, 1960, Los Angeles Examiner Pictorial Living section, a pull-out section in the Sunday edition of the newspaper. The article about the house, “Milestone on a Hilltop,” also included additional Shulman photographs.

By the time Shulman photographed the Stahl House he was an internationally recognized photographer. He was indirectly becoming a documentarian, historian, participant, witness, and promulgator of modern architecture and design in Los Angeles.

The Stahl House photograph, taken Monday, May 9, 1960, has the feel of a Saturday night, projecting enjoyment and life in a modern home. Shulman reinforces the open but private space by minimizing the separation of indoor and outdoor. The photograph achieves a visual balance through lighting that is both conventional and dramatic. As with much of Shulman’s signature work, horizontal and vertical lines and corners appear in the frame to create depth and direct the viewer’s eye, creating a dimensional perspective instead of a flat, straightforward position. The effect is a narrative that emphasizes Koenig’s architecture.

“What’s so amazing is that the house is completely ethereal,” architect Leo Marmol said in an interview with LaFetra in 2007. “It’s almost as though it’s not there. We talk about it as though it’s a photograph of an architectural expression but really, there’s very little architecture and space. It’s a view. It’s two people. It’s a relationship.”

Shulman recalled how the image came about in an interview with Taina Rikala De Noriega for the Archives of American Art:

So we worked, and it got dark and the lights came on and I think somebody had brought sandwiches. We ate in the kitchen, coffee, and we had a nice pleasant time. My assistant and I were setting up lights and taking pictures all along. I was outside looking at the view. And suddenly I perceived a composition. Here are the elements. I set up the furniture and I called the girls. I said, “Girls. Come over sit down on those chairs, the sofa in the background there.” And I planted them there, and I said, “You sit down and talk. I'm going outside and look at the view.” And I called my assistant and I said, “Hey, let's set some lights.” Because we used flash in those days. We didn't use floodlights. We set up lights, and I set up my camera and created this composition in which I assembled a statement. It was not an architectural quote-unquote “photograph.” It was a picture of a mood.

The two girls in the photograph were Ann Lightbody, a 21-year-old UCLA student, and her friend, Cynthia Murfee (now Tindle), a senior at Pasadena High School. At Shulman’s suggestion, Koenig told his assistant Jim Jennings, a USC architecture student, and his friend, fellow architecture student Don Murphy, to bring their girlfriends to the house. Shulman liked to include people in his photographs and intuitively felt the girls’ presence would offer more options. As for their white dresses, Tindle explains, “… in 1960, you didn't go out without wearing a dress. You would never have gone out wearing jeans or pants.”