- Privacy Policy

Home » Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Context of the Study

The context of a study refers to the set of circumstances or background factors that provide a framework for understanding the research question , the methods used, and the findings . It includes the social, cultural, economic, political, and historical factors that shape the study’s purpose and significance, as well as the specific setting in which the research is conducted. The context of a study is important because it helps to clarify the meaning and relevance of the research, and can provide insight into the ways in which the findings might be applied in practice.

Structure of Context of the Study

The structure of the context of the study generally includes several key components that provide the necessary background and framework for the research being conducted. These components typically include:

- Introduction : This section provides an overview of the research problem , the purpose of the study, and the research questions or hypotheses being tested.

- Background and Significance : This section discusses the historical, theoretical, and practical background of the research problem, highlighting why the study is important and relevant to the field.

- Literature Review: This section provides a comprehensive review of the existing literature related to the research problem, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies and identifying gaps in the literature.

- Theoretical Framework : This section outlines the theoretical perspective or perspectives that will guide the research and explains how they relate to the research questions or hypotheses.

- Research Design and Methods: This section provides a detailed description of the research design and methods, including the research approach, sampling strategy, data collection methods, and data analysis procedures.

- Ethical Considerations : This section discusses the ethical considerations involved in conducting the research, including the protection of human subjects, informed consent, confidentiality, and potential conflicts of interest.

- Limitations and Delimitations: This section discusses the potential limitations of the study, including any constraints on the research design or methods, as well as the delimitations, or boundaries, of the study.

- Contribution to the Field: This section explains how the study will contribute to the field, highlighting the potential implications and applications of the research findings.

How to Write Context of the study

Here are some steps to write the context of the study:

- Identify the research problem: Start by clearly defining the research problem or question you are investigating. This should be a concise statement that highlights the gap in knowledge or understanding that your research seeks to address.

- Provide background information : Once you have identified the research problem, provide some background information that will help the reader understand the context of the study. This might include a brief history of the topic, relevant statistics or data, or previous research on the subject.

- Explain the significance: Next, explain why the research is significant. This could be because it addresses an important problem or because it contributes to a theoretical or practical understanding of the topic.

- Outline the research objectives : State the specific objectives of the study. This helps to focus the research and provides a clear direction for the study.

- Identify the research approach: Finally, identify the research approach or methodology you will be using. This might include a description of the data collection methods, sample size, or data analysis techniques.

Example of Context of the Study

Here is an example of a context of a study:

Title of the Study: “The Effectiveness of Online Learning in Higher Education”

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced many educational institutions to adopt online learning as an alternative to traditional in-person teaching. This study is conducted in the context of the ongoing shift towards online learning in higher education. The study aims to investigate the effectiveness of online learning in terms of student learning outcomes and satisfaction compared to traditional in-person teaching. The study also explores the challenges and opportunities of online learning in higher education, especially in the current pandemic situation. This research is conducted in the United States and involves a sample of undergraduate students enrolled in various universities offering online and in-person courses. The study findings are expected to contribute to the ongoing discussion on the future of higher education and the role of online learning in the post-pandemic era.

Context of the Study in Thesis

The context of the study in a thesis refers to the background, circumstances, and conditions that surround the research problem or topic being investigated. It provides an overview of the broader context within which the study is situated, including the historical, social, economic, and cultural factors that may have influenced the research question or topic.

Context of the Study Example in Thesis

Here is an example of the context of a study in a thesis:

Context of the Study:

The rapid growth of the internet and the increasing popularity of social media have revolutionized the way people communicate, connect, and share information. With the widespread use of social media, there has been a rise in cyberbullying, which is a form of aggression that occurs online. Cyberbullying can have severe consequences for victims, such as depression, anxiety, and even suicide. Thus, there is a need for research that explores the factors that contribute to cyberbullying and the strategies that can be used to prevent or reduce it.

This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and cyberbullying among adolescents in the United States. Specifically, the study will examine the following research questions:

- What is the prevalence of cyberbullying among adolescents who use social media?

- What are the factors that contribute to cyberbullying among adolescents who use social media?

- What are the strategies that can be used to prevent or reduce cyberbullying among adolescents who use social media?

The study is significant because it will provide valuable insights into the relationship between social media use and cyberbullying, which can be used to inform policies and programs aimed at preventing or reducing cyberbullying among adolescents. The study will use a mixed-methods approach, including both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of cyberbullying among adolescents who use social media.

Context of the Study in Research Paper

The context of the study in a research paper refers to the background information that provides a framework for understanding the research problem and its significance. It includes a description of the setting, the research question, the objectives of the study, and the scope of the research.

Context of the Study Example in Research Paper

An example of the context of the study in a research paper might be:

The global pandemic caused by COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the mental health of individuals worldwide. As a result, there has been a growing interest in identifying effective interventions to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic on mental health. In this study, we aim to explore the impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on the mental health of individuals who have experienced increased stress and anxiety due to the pandemic.

Context of the Study In Research Proposal

The context of a study in a research proposal provides the background and rationale for the proposed research, highlighting the gap or problem that the study aims to address. It also explains why the research is important and relevant to the field of study.

Context of the Study Example In Research Proposal

Here is an example of a context section in a research proposal:

The rise of social media has revolutionized the way people communicate and share information online. As a result, businesses have increasingly turned to social media platforms to promote their products and services, build brand awareness, and engage with customers. However, there is limited research on the effectiveness of social media marketing strategies and the factors that contribute to their success. This research aims to fill this gap by exploring the impact of social media marketing on consumer behavior and identifying the key factors that influence its effectiveness.

Purpose of Context of the Study

The purpose of providing context for a study is to help readers understand the background, scope, and significance of the research being conducted. By contextualizing the study, researchers can provide a clear and concise explanation of the research problem, the research question or hypothesis, and the research design and methodology.

The context of the study includes information about the historical, social, cultural, economic, and political factors that may have influenced the research topic or problem. This information can help readers understand why the research is important, what gaps in knowledge the study seeks to address, and what impact the research may have in the field or in society.

Advantages of Context of the Study

Some advantages of considering the context of a study include:

- Increased validity: Considering the context can help ensure that the study is relevant to the population being studied and that the findings are more representative of the real world. This can increase the validity of the study and help ensure that its conclusions are accurate.

- Enhanced understanding: By examining the context of the study, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the factors that influence the phenomenon under investigation. This can lead to more nuanced findings and a richer understanding of the topic.

- Improved generalizability: Contextualizing the study can help ensure that the findings are applicable to other settings and populations beyond the specific sample studied. This can improve the generalizability of the study and increase its impact.

- Better interpretation of results: Understanding the context of the study can help researchers interpret their results more accurately and avoid drawing incorrect conclusions. This can help ensure that the study contributes to the body of knowledge in the field and has practical applications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Place matters: geographical context, place belonging and the production of locality in Mediterranean Noirs

- Open access

- Published: 25 July 2021

- Volume 87 , pages 3895–3913, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Nicola Gabellieri 1

4330 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Scholars have been investigating detective stories and crime fiction mostly as literary works reflecting the societies that produced them and the movement from modernism to postmodernism. However, these genres have generally been neglected by literary geographers. In the attempt to fill such an epistemological vacuum, this paper examines and compare the function and importance of geography in both classic and late 20th century detective stories. Arthur Conan Doyle’s and Agatha Christie’s detective stories are compared to Mediterranean noir books by Manuel Montalbán, Andrea Camilleri and Jean Claude Izzo. While space is shown to be at the center of the investigations in the former two authors, the latter rather focus on place, that is space invested by the authors with meaning and feelings of identity and belonging. From this perspective, the article argues that detective investigations have become a narrative medium allowing the readership to explore the writer’s representation/construction of his own territorial context, or place-setting, which functions as a co-protagonist of the novel. In conclusion, the paper suggests that the emerging role of place in some of the later popular crime fiction can be interpreted as the result of writer’s sentiment of belonging and, according to Appadurai’s theory, as a literary and geographical discourse aimed at the production of locality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Place Becoming Space: Nation and Deterritorialisation in Cuban Narrative of the Twenty-First Century

Geography and Power: Mapping The Murderer’s Ape

Cities, Territories and Conflict: Narrative and the Colombian City in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last few decades, detective novels have become one of the most successful literary genres in terms of both production and sales (Rushing, 2007 ; Worthington, 2011 ; Perez, 2013 ). Footnote 1 This achievement largely depends on the possibility to resort to the investigative plot as a narrative expedient to expose individual psychological introspection, while at the same time representing the social mechanisms of the place where the crime is committed. As a result, detective stories can incorporate reflections on issues such as gender, multiculturalism and class struggles, which have increased the genre’s appeal to a wider public (Priestman, 2003 ). Furthermore, the renewal of this genre has not been limited to including new characters or articulating new plots, but has also involved geographical contents into the books.

Literary geography is that part of the discipline that studies the way in which certain landscapes or territories influence writers and artists, as well as the way in which these are described in literary works (Lando, 1996 ; Hones, 2014 ; Brosseau, 2017 ). Given the importance of geography as a literary topos (Peraldo, 2016 ), it is yet surprising that the role of spatial descriptions in detective novels has been little considered by the researchers. Notwithstanding some important pioneering contributions, there is still an epistemological gap that needs to be filled. In recent times, scholars have become increasingly interested in approaching the subject of space in detective stories through different heuristic frameworks, including the contemporary problems of place, identity and locality (Tuan, 1985 ; Rosemberg, 2007 ; Rosember 2008 ; Erdmann, 2011 ; Pezzotti, 2012 ; Pichler, 2015 ; Brosseau & Le Bel, 2016 ; Giorda, 2019 ).

Following Roland Barthes ( 1964 ) and Jacques Dubois’s ( 1992 ) suggestions on crime fiction as mirror and expression of social and cultural dynamics, this work explores detective novels from the standpoint of literary geography, considering literature as one source to investigate relations between people and place (Anderson, 2015 ) and focusing on the way in which “space” and “place” are represented as well as the role that geographical space plays in structuring the crime fiction narrative. Geographers have shown that these categories are not just synonymous, nor they merely represent settings for action: they are tools with which people define their identity. The different terms are used to distinguish between the two concepts of neutral Cartesian space and of place as “lived space” invested with meaning by the observer (Tuan, 1974 ; Frémont 1976 ; Paasi, 2002 ; Harvey, 2012 ). In this respect, different and sometime contested definitions of “place” agree in considering the term both as a means that people use to collectively define territory and as a produced symbolic representation for different purposes (Seamon & Sowers, 2008 ; Antonsich, 2010a ).

This study has two main aims. First, to demonstrate that, in late 20th century literature, detective investigations have become a narrative medium allowing the readership to explore the writer’s representation/construction of his own territorial context, or place-setting, which functions as a co-protagonist of the novel. Second, by focusing on the genre known as Mediterranean noir, the paper aims at shedding new light on the way in which popular literature narrates and contributes to construct the ideas of place according to the category of production of localities suggested by Arjun Appadurai.

In geography, the study of novel settings has a long tradition. Scholars have pointed out that short stories, poems and fiction can capture features of the local reality which are generally overlooked by purely quantitative approaches (Lando, 1996 ; Squire, 1996 ). In the 1960s and 1970s, in the wake of the studies on regionalism – which aim to define the regions’ local identities – regional literature (i.e. stories taking place at a regional scale, as well as novels produced by local authors) was deemed a fundamental means for revealing the uniqueness of each geographical area (Gilbert, 1960 ). In search of descriptions that could prove useful to grasp the local dimension and “typical” elements of the regions, much research has been dedicated in particular to rural environments and the countryside, often with a critical approach focusing on the discussion of constructed myths (Aiken, 1977 ; Withers, 1984 ; 2018 Frémont, 1990 ; Fournier, 2018 ; 2020 ; Ridanpää, 2019 ; Gope, 2020 ).

More recently, the emphasis has been placed on the capacity of literature to participate in the construction of “imagined communities” (Anderson, 1983 ). Texts are acknowledged as phenomena, results and producers of complex and different meanings and effects. Defining fiction as “spatial event”, Sheila Hones invites to consider connected spatial and temporal events proceeding and following the publications from a relational perspective (Hones, 2008 , 2014 ), implying that a book can affect the space where its story is settled, endowing it with new significance and identities (Anderson, 2010 ; Briwa, 2018 ).

To build on this line of research, I would link Literary Geography with Arjun Appadurai’s notion of “production of localities”. Appadurai demonstrates that “places” do not represent a permanent natural datum, but rather a context generated by the actions through which different social actors build their relational systems in space, and do so by using various strategies for identifying and mapping accordingly the identity elements that characterize each locality; in turn, places are context-generating agents, because they create relationships between many social actors (Appadurai, 1996 , 2010 ).

To explore the geographical discourse of contemporary detective novels as production of localities, this essay deals with three authors who can be classified in the sub-genre of Mediterranean noir. The term was coined in 2000 by one of its protagonists, Jean-Claude Izzo, to qualify contemporary crime and detective fiction by writers who shared common ground, geographic and otherwise, such as Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Andrea Camilleri and Petros Markaris. These authors are representatives of a new current of detective stories based on postmodernism (Holquist, 1971 ) that has already been approached by literary geographers to examine the construction of the idea of Marseille (Rosemberg, 2007 , 2008 ).

To assess the hypothesis of an emerging role of place in recent detective fiction, this work adopts a comparative method. The first part presents some excerpts from detective fiction falling within an assumed “classic” phase, with the purpose of calling attention to the relationship between detectives and space during the deductive process that guides the story. Footnote 2 In the second and third part, the focus shifts to three prominent authors of Mediterranean detective novels who can be considered as exponents of the Mediterranean Noir. Montalbán, Camilleri and Izzo have been selected as case studies because of their respective relevance to Spanish, Italian and French readerships, alongside their recognition as milestone authors in crime fiction historiography. Their popularity at international level has crossed the boundaries of the literary sphere, making them prime representatives of the places where their novels lure tourism (Di Betta, 2015 ; Ponton & Asero, 2015 ; Redondo, 2017 ; Rosemberg & Troin, 2017 ).

Methodologically, according to Brosseau ( 1994 ), literary geography may, in first instance, approach the “text as text”.In the first part of this paper plot summaries are thus presented together with some excerpts from famous detective fiction which have been selected in order to identify space descriptions and their geographical elements.

The following part focuses on the evolution of the function and significance of generic setting in relation to story plot and narrative style. To this end, a relational approach has been adopted (Hones, 2014 ), considering the significance of local place settings and the contribution of writers and readers in reflecting and creating territorial meaning and images beyond the story itself.

Space in classic detective stories: Poe, Conan Doyle and Christie

In 1841, Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) published The Murders in the Rue Morgue , traditionally considered the first detective story in the modern sense of the term. The plot hinges on the solving of a crime that has taken place in a closed room. To present C. Auguste Dupin’s (the main character) exceptional deductive abilities, Poe dwells on some specific details of him strolling on the streets of Paris. The focus then shifts to the closed room where a terrible crime has been committed and which the author describes in detail, focusing on some morbid elements and on some objects that will play a key role in the investigation:

“The apartment was in the wildest disorder—the furniture broken and thrown about in all directions. There was only one bedstead; and from this the bed had been removed, and thrown into the middle of the floor. On a chair lay a razor, besmeared with blood. On the hearth were two or three long and thick tresses of grey human hair, also dabbled in blood, and seeming to have been pulled out by the roots. Upon the floor were found four Napoleons, an ear-ring of topaz, three large silver spoons, three smaller of métal d'Alger, and two bags, containing nearly four thousand francs in gold. […] Four of the above-named witnesses, being recalled, deposed that the door of the chamber in which was found the body of Mademoiselle L. was locked on the inside when the party reached it” (Poe, 1841 , 169).

Dupin eventually manages to tie up loose ends by combining ground observation, comparative analysis of evidence and inductive logic. In fact, the real plot twist is the discovery of the murderer thanks to the detective’s skills. The surprise lies in the geographical estrangement of the reader, that is the introduction in a known context of an unexpected foreign element: a Bornean orangutan who is later found guilty of the murder.

Starting from this pioneering experiment, detective stories have grown significantly as a genre in the Anglo-Saxon literary tradition, where the most representative authors are Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) and Agatha Christie Mallowan (1890–1976) (Rzepka, 2005 ).

Despite his vast production of fiction and non-fiction, Conan Doyle is most famed as the forerunner of the subgenre of deductive thriller, undoubtedly thanks to the Sherlock Holmes cycle. The adventures of one of the most famous detectives in the world are narrated in four novels: A Study in Scarlet , The Sign of the Four , The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Valley of the Fear , all published between 1887 and 1915, in addition to other 50 short stories and 3 theater plays.

The logical and deductive abilities that underlie the protagonist’s scientific method are explained in the opening pages of the first novel. The first geographical descriptions, however, emerge only in the third chapter, during the inspection of the crime site, a small cottage near London:

“Number 3, Lauriston Gardens wore an ill-omened and minatory look […] A small garden sprinkled over with a scattered eruption of sickly plants separated each of these houses from the street, and was traversed by a narrow pathway, yellowish in colour, and consisting apparently of a mixture of clay and of gravel. The whole place was very sloppy from the rain which had fallen through the night. […] It was a large square room, looking all the larger from the absence of all furniture. A vulgar flaring paper adorned the walls, but it was blotched in places with mildew; and here and there great strips had become detached and hung down, exposing the yellow plaster beneath. Opposite the door was a showy fireplace, surmounted by a mantelpiece of imitation white marble. On one corner of this was stuck the stump of a red wax candle. […] I have remarked that the paper had fallen away in parts. In this particular corner of the room a large piece had peeled off, leaving a yellow square of coarse plastering. Across this bare space there was scrawled in blood-red letters a single word—RACHE” (Conan Doyle, 1887 , 27–31).

A full-fledged landscape representation appears only in the second part of the novel, once the killer has been identified and captured. The explanation of the reasons that led him to commit the crime is introduced by an extensive description of the inhospitable habitat where the story had begun – the Colorado desert:

“In the central portion of the great North American Continent there lies an arid and repulsive desert, which for many a long year served as a barrier against the advance of civilization. From the Sierra Nevada to Nebraska, and from the Yellowstone River in the north to the Colorado upon the south, is a region of desolation and silence. Nor is Nature always in one mood throughout this grim district. It comprises snow-capped and lofty mountains, and dark and gloomy valleys. There are swift-flowing rivers which dash through jagged cañons; and there are enormous plains, which in winter are white with snow, and in summer are grey with the saline alkali dust. They all present however, the common characteristics of bareness, inhospitality, and misery. […] In the whole world there can be no more dreary view than that from the northern slope of the Sierra Blanco” (Conan Doyle, 1887 , 56).

Unlike the first book, in The Hound of the Baskervilles many pages are dedicated to illustrating the gloomy atmosphere of the Devonshire moor since the arrival of Dr. Watson at the castle:

“We had left the fertile country behind and beneath us. We looked back on it now, the slanting rays of a low sun turning the streams to threads of gold and glowing on the red earth new turned by the plough and the broad tangle of the woodlands. The road in front of us grew bleaker and wilder over huge russet and olive slopes, sprinkled with giant boulders. Now and then we passed a moorland cottage, walled and roofed with stone, with no creeper to break its harsh outline. Suddenly we looked down into a cup-like depression, patched with stunted oaks and furs which had been twisted and bent by the fury of years of storm. Two high, narrow towers rose over the trees” (Conan Doyle, 1902 , 116).

During his stay at the castle, landscape descriptions are part of Watson’s musings and the gloomy climate, along with the desolate environment, help reinforce the suggestion of a family curse, until Holmes carries out the investigation according to the classic deductive method.

As famous and prolific as Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie is another outstanding author in this phase of the Anglo-Saxon mystery novel tradition (Bargainnier, 1980 ). Through her vast literary output, including nearly 66 novels and 14 collections of short stories as well as some romance novels and plays, she introduced worldwide famous detectives such as Hercule Poirot (who appeared in about 36 novels and collections of short stories between 1920 and 1975) and Jane Marple (who appeared in 12 novels and 4 collections of short stories published between 1930 and 1976).

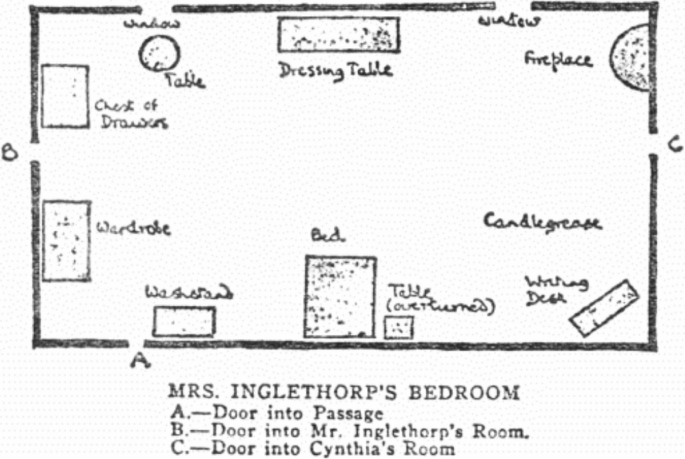

The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920) is Christie’s first detective novel featuring Poirot, a Belgian gentleman who has taken refuge in England and possesses remarkable logic skills, which he uses to solve mysterious crimes. In the novel, few lines are spent to describe the English countryside landscape of Essex where the victim’s villa and the cottages of the different characters are located. The first actual geographical overview can be found in the fourth chapter, shortly after the introduction of the protagonist: the reader is presented with an actual topographic map of the room where the victim was found. The sketch pinpoints the location of the furniture as well as some of the passageways through which the investigator will move in search of clues in the following pages (Fig. 1 ). These are the only moments of geographical interest in the text, except for a few descriptions of the surrounding landscape which serve to highlight some features of Poirot’s personality, who is as hostile towards the disorderly countryside as amazed in front of the landscapes ruled by the human touch: “‘Admirable!’ he murmured. ‘Admirable! What symmetry! Observe that crescent; and those diamonds—their neatness rejoices the eye. The spacing of the plants, also, is perfect’” (Christie, 1920 , 50), he whispers while observing an English-style garden.

Map of the crime scene drawn for investigation purposes and published in Christie, 1920

By connecting the various clues with the information that he has gathered and by using his skills in chemical sciences, Poirot is able to reconstruct the events that led to the woman’s death and to uncover the identity of the killer, her unfaithful husband. This deductive investigation procedure – inspired by his counterpart’s, Holmes – is also applied in subsequent books, such as Murder on the Orient Express ( 1934 ). In this case, the crime is committed in a setting that is more exotic for the English reader. Poirot, who happens to be on the famous Orient Express train traveling from Istanbul to Calais, finds himself involved in a murder case for which he is asked to question all the passengers in the victim’s wagon. Despite the fascination of the journey, only few words are spent to depict the landscapes visible from the windows and for the territories traversed by the train; besides, the description of the crime scene is limited to the few false leads that the detective manages to identify. The investigation proceeds by way of a detailed analysis and comparison between the different versions, statements and alibis provided by the passengers. The train remains a closed world consisting solely of its passengers, among which Poirot continues to search for a culprit until he finds twelve; but the narration ends without providing any information on the route traveled.

Montalbán and Carvalho’s Barcelona

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán (1939–2003) is acknowledged as the most important crime fiction writer of Spain, as well as the author of numerous historical novels and literary treatises. Born in Barcelona into a family of socialist tradition, in 1962 he was himself sentenced to three years in prison for anti-Franco activities. With a degree in philosophy and journalism, after the fall of the Regime he began to work for local and national newspapers. His name is associated in particular with the character of Pepe Carvalho, the chief investigator in 18 novels, 6 collections of short stories and a cookbook, all written in Castilian between the 1970s and the 2000s (Bayó Belenguer, 2006 ; Garcia, 2014 ; Tosik, 2020 ).

Pepe Carvalho made his first appearance in the uchronic novel Yo maté a Kennedy ( 1972 ), where the motley court of the Kennedys and the most widespread left-wing cultural theories of the time are presented with a unique fragmentary style and in a visionary, ironic and critical way. This is also where the author introduces the character of a CIA agent of Spain Galician origins, who has a past as a leftist activist and is now a cynical and ruthless double agent.

Starting from the second novel, Tatuaje ( 1974 ), the narrative style, the character of Carvalho and the Catalan setting are consolidated and become the leitmotiv of all subsequent publications. Shortly described as “that tall, dark man, already over thirty, a little neglected despite wearing expensive Ensache tailoring clothes”, Footnote 3 Carvalho is a paradigmatic example of the anti-hero, openly inspired to Philip Marlowe by Raymond Chandler (1888–1959). In fact, the work of these two authors is generally considered as a watershed in the history of detective stories, on account of their devising of complex plots in complex worlds where the investigator’s psychological prospects are put to the fore.

Carvalho is a private detective as well as a bon vivant , an educated man who loves women and adores cooking. At the same time, he is deeply tormented, cynical, disenchanted, someone who bears within himself the wounds of dictatorship. Left-wing activist in his youth and a troubled past in the CIA, he dedicates himself to postmodern rebellious practices, such as burning literary works. He also gladly mingles with those who live on the fringes of society, including criminals, prostitutes, fences and former Francoists, which allows Montalbán to bring forth a diverse humanity during the investigations, under a light that is never totally negative, except for the great Catalan capitalists.

In Montalbán, the investigation is an immersion in the social and cultural context where the action unfolds (Bayó Belenguer, 2006 ). Carvalho himself wonders whether “a policeman like me is not perhaps a sociologist?”. Footnote 4 This attention to the surrounding world emerges in the representation of the crime scenes, as in Los mares del sur : while describing the study of the victim, Stuart Pedrell, the narrator focuses especially on listing the titles of the books that are placed in the library, which do not contain any clues for solving the case but offer an insight into the life of a Barcelonan leftist upper-middleclass businessman. Few well-defined elements portray the psychology of the characters: education, social class, and geographic background, as with Carvalho who is described as stubborn because of his Galician origins. Explicitly mentioning the names of the city’s streets and neighborhoods, urban landscape descriptions are rich in details and combine historical and social contextualization with the representation of the protagonist’s feelings and observations:

“The Via Layetana aroused quite another feeling in him with its appearance as an undecided first step in the creation of a Barcelona-based Manhattan, never finished. It was a road built in the interwar period, with the port at one end and the artisan Barcelona of Gracia on the other, artificially open to ease the commercial tension of the metropolis, and over time it had become a road of trade unions and patronages, of policemen and their victims, with the addition of a few savings banks and in the Gothicizing background the monument in the middle of the gardens, dedicated to one of the most solid counts in Catalonia”. Footnote 5

Fundamental topoi for the characterization of the novel’s setting are food and local cuisine, which can be seen as the very element of Spanish identity: “If the Thirty Years War had not determined the hegemony of France over Europe, French cuisine today would have fallen under the hegemony of the various Spanish cuisines. His only patriotism was gastronomic”. Footnote 6 It seems therefore unsurprising that, for instance, the new striker of the Barcelona football team has to eat different Catalan dishes in order to seal his membership to the city community and thereby be introduced to “the matrix of essential Catalonia: bread and tomato, cava , seques amb botifarra , escudella i carn d'olla ”. Footnote 7 When he gets involved in a Catalanist conspiracy, Carvalho too decides to “eat Catalan cuisine to begin to totally identify with the cause, and asked for an escudella barrajada and peus de porc amb cargols , aware of the fact that the escudella barrejada is made with leftovers of the best escudellas , the remains of their splendor, and that the pig’s feet with snails are low in calories and completely free of cholesterol”. Footnote 8

Carvalho is also a skilled cook. Several pages in the novels illustrate the preparation of complex recipes that come from the Catalan culture as from other Iberian areas. Not only the dishes, but each and every ingredient is carefully reported and geographically localized, thus reflecting the author’s critical stance against any geographic-culinary generalization: “Nowadays they pass off any ham as if it were from Salamanca. Any ham who is not from Jabugo or Trevelez is called Salamanca ham. There is to be indignant. And so it is no longer clear whether you eat Salamanca or Totana ham”. Footnote 9

In spite of the identification with Barcelona, Montalbán chose not to write in Catalan but in the Castilian language, which allowed him to reach a wider audience. However, some words in Catalan gradually surface in the dialogues between his characters: the language marks the emergence of an identity that has occurred over the last decades.

The character of Carvalho, who has been regarded as an alter ego of the author, progressively ages over the course of the fiction. Even the city of Barcelona changes, reflecting the evolution of a post-regime city which becomes one of the economic, social and cultural hubs of the Mediterranean, although through an urban gentrification process that happens at the expense of the weakest:

“Perecamps Street had to be lengthened to cut through the streets of the old city in search of the Ensanche, making its way for the destroyed meats and calcined skeletons of the most miserable architecture in the city. A gigantic bulldozer with an insect head would have transformed the archeology of misery […] but also after the demolition of homes and the elderly, addicts, petty drug dealers, poor whores, blacks, Moroccans, after having made them escape pushed from the mechanical excavator, somewhere they would have brought their misery, perhaps in the hinterland, where the city loses its name and is no longer responsible for its disasters”. Footnote 10

As a matter of fact, in Montalbán, time assumes a central role (Tosik, 2020 ) which also affects the representation of spaces. A melancholic and nostalgic Carvalho witnesses the progressive destruction and redevelopment of those urban districts with which he identifies and which he cannot help but love:

“Carvalho set out there with a desire to re-read the city, to reconcile himself with Barcelona’s desire to transform itself into a pasteurized city, despite the smell of fried shrimp that came from the metastases of the restaurants of the Villa Olimpica […] Every metaphor of the city was become useless: it was no longer the widowed city, widow of power, because it had now acquired this power through the institutions of Autonomy; it was no longer even the Rose of Fire of the anarchists, because the bourgeoisie had definitively won with the system of changing its name […] Barcelona had become a beautiful city but without a soul, like certain statues, or perhaps it had a new soul that Carvalho neglected in his walks until he admitted that perhaps age no longer allowed him to discover the spirit of the new times [….] but he was falling in love with his city again, and above all he had to restrain the tendency to feel satisfied as he descended the Ramblas”. Footnote 11

The setting of the novel shifts therefore from urban slums to rich bourgeois neighborhoods, in a perpetually changing city which evolves from a 1970s town to one of the richest metropolises in the Mediterranean. Barcelona becomes indeed the stage of an intense cultural ferment and nightlife, reclaiming its role as an economic hub and developing instances of cultural and political independence from Madrid, to which Montalbán spares no fierce criticism (Afinoguénova, 2006 ). Unsurprisingly, Carvalho will leave Barcelona to go on his odyssey around the world only in the last two books, finding death (Montalbán, 2004 ).

Camilleri and Montalbano’s Sicily

Andrea Camilleri (1925–2019) can be considered as the most famous Italian crime writer, owing to the enormous success of his books starring police commissioner Salvo Montalbano and of their screen adaptation (Pieri, 2011 ). Originally from Porto Empedocle, in the province of Agrigento in Sicily, Camilleri began working for RAI national broadcasting in 1957 as a screenwriter and director. His first successful novel, Un filo di fumo ( 1980 ), tells the story of some events that took place in the late 19th century imaginary town of Vigata, in the Agrigento area. The town later became the setting of Commissioner Montalbano’s investigations, narrated in 28 novels and 5 collections of short stories that were published between 1994 and 2020. The influence that Montalbán had on the Italian author is manifestly spelled out in the detective’s name (Lyria, 2003 ). Like his Spanish peer, Camilleri too has often been considered as a committed writer (Chu, 2011 ). Moreover, he has repeatedly claimed to owe an intellectual debt to Italian regionalist writers such as Emilio Gadda and Leonardo Sciascia (Cicioni and Di Ciolla, 2008 ).

All of Camilleri’s literary production is set in Sicily, both crime fiction and historical novels. The writer stated numerous times in his interviews that he does “not possess the fantasy of, say, a Verne” and therefore “after he had imagined a fictional story, all he could do was set it, as it was, in the houses and streets that he already knew well” (Camilleri, cit. in Cicioni and Di Ciolla 2008 , 11). The preferential location for his stories is Vigata, a big city in the province of Montelusa: both are fictitious names for the author’s hometown, Porto Empedocle, and the province of Agrigento respectively (Pezzotti, 2015 ). Other toponyms are also altered in the novels, including the island of Lampedusa, renamed Sampedusa.

Montalbano and his Catalan counterpart share certain identifying features: they are both well-educated, gourmand, tendentially left-wing, grumpy; they are men of insight, gifted with the wit to unfailingly solve the most complicated cases; they are both women lovers in a complicated relationship with their historical partner.

Camilleri’s debut novel, La forma dell’acqua , begins with the description of the site where a corpse is found:

“It was the area called “la mannara”, because many years ago a shepherd was used to maintain his sheep there. It was a large stretch of Mediterranean scrub between the outskirts of the town and the beach, with the remains of a large chemical plant behind it, inaugurated by the omnipresent Deputy Cusumano when it seemed that the wind of the magnificent and progressive fortunes was pulling strong, then that breeze quickly changed into a trickle of breeze and therefore fell completely”. Footnote 12

In few lines, Camilleri introduces the readers to the contradictions of living in a rural environment that is undergoing a discontinuous process of industrialization and modernization, but is at the same time characterized by a traditional and corrupt system of power. Coincidentally, the corpse found by the police belongs to an important local businessman and politician. During the investigation, by exposing the political mafia games behind the murder, Montalbano manages to rule out as a suspect the victim’s lover. In the following books, the narrative structure is progressively established: parallel storylines originate from one or more crimes and then gradually intertwine. However, it is not always about mafia murders. The investigation often revolves around crimes of passion perpetrated after the break of some codes of honor in a traditional and patriarchal society on the periphery of Italy, where violence is daily fare:

‘Any news today?’ ‘Nothing to be taken seriously, Commissioner. Someone’s set fire to Sebastiano Lo Monaco’s garage, the fire brigade went there and put out the fire. Then someone shot at Quarantino Filippo, but it goes wrong and took the window of which is inhabited by Mrs. Pizzuto Saveria. After that there was another fire, certainly fraudulent. In short, doctor, bullshits’. Footnote 13

Anthropological cultural features are not presented invariably under a negative light. Local codes of conduct can often be associated with positive character traits that define Sicilian society: “Montalbano was touched. That was the Sicilian friendship, the true one, which is based on the unspoken, on intuition; one friend does not need to ask, it is the other who autonomously understands and acts accordingly”. Footnote 14

For this reason, the many landscape descriptions in the novels are always complemented by a lucid, sometimes even cynical reflection on society, avoiding any aura of myth:

“Around there were lands planted with vineyards, and as far as the eye could see there were almond trees between which, from time to time, the white of rural huts stood out. It was an enchanting landscape that reassured the hearth and the soul, but in Montalbano arose a tinged thought. Let’s wonder how many mafia fugitives were still living in these houses of apparently innocent traits”. Footnote 15

Montalbano is inextricably attached to his land, to the point that he feels profoundly homesick on the few occasions he goes to Genoa, where his partner lives: “Two or three times, by betrayal, the smell, the speech, the things of his hometown seized him, they lifted him in the air without weight, they brought him back, for a few moments, to Vigata”. Footnote 16 Vigata is not just a rural city but a frontier on the Mediterranean, affected by migration from North Africa, as the readers are told in Il ladro di merendine ( 1996 ). In this book, several narrative storylines intertwine, recounting the investigations on the murder of a retired man, the disappearance of a young Tunisian mother and her son, and the eventful search for an international terrorist. Camilleri emphasizes the existence of a common identity between the two sides of the sea, sometimes dwelling on those elements that testify to the Arab domination of the past while also depicting the poor conditions of the new immigrants:

“In the era of Muslims Sicily, when Montelusa was called Kerkent, the Arabs had built a neighborhood on the edge of the town where they lived together. When the Mulsumans had fled, the Montelusans had gone to live in their homes and the name of the neighborhood had been Sicilianized in Rabatu. In the second half of this century a gigantic landslide destroyed it. The few houses still standing were damaged, lopsided, held in absurd balances. The Arabs, having returned this time as poor people, had resumed living there, putting pieces of sheet metal in place of the tiles”. Footnote 17

Furthermore, the hybrid language of the novel is heavily layered with elements of the Sicilian dialect that are virtually incomprehensible to the average Italian reader, so much so that infratextual explanations are often needed: “’Now I'm going to tambasiare ’ he thought as soon as he arrived home. Tambasiare was a verb he liked, it meant wandering from room to room without a specific purpose, indeed dealing with futile things”. Footnote 18

Despite his great passion for regional cuisine, Montalbano is not the best cook, unlike his Catalan colleague. Consequently, to enjoy the many Sicilian dishes mentioned throughout the books, he relies on Adelina’s – his housekeeper – cooking skills and on his friendship with the owners of Trattoria San Calogero and Trattoria da Enzo, two typical restaurants serving local food: “At the San Calogero Restaurant they respected him, not because he was the Commissioner but because he was a good customer, one of those who know how to appreciate. They made him eat very fresh red mullet, crispy fried and left a time to drain on the paper”. Footnote 19 The act of eating takes on hedonistic and almost ritual connotations, with detailed descriptions of the tasting:

“He received the eight pieces of hake, a portion clearly for four people. They screamed, the pieces of hake, their joy at having been cooked as God commands. The dish smell demonstrated its perfection, obtained with the right amount of breadcrumbs, with the delicate balance between anchovy and beaten egg. He took the first bite to his mouth, but he didn’t swallow it immediately. He allowed the taste to spread gently on the tongue and palate, so that the tongue and palate became more aware of the gift offered to them”. Footnote 20

In Camilleri’s stories Sicily seems destined to unvarying immobility, as if it were frozen in traditional millenary codes. Nevertheless, although more slowly than Montalbán’s Barcelona, the region gradually begins to change along with the society it represents. Over time, rural Sicily starts to disappear:

“When he had arrived in Vigata he had made himself aware of the territory in which he had to struggle. So he had made a long and wide round of reconnaissance. In those time, the countryside was fruitful, green and full of life because was cared for and respected by man. Now a desert was in sight, a kingdom of snakes and yellowish grass. It seemed that that land had been touched by a biblical malice that sentenced it to sterility and that even the houses, ill as they were, had been affected by it”. Footnote 21

While Montalbano himself ages book after book, feeling increasingly incapable of facing the challenges of modernity, such as the spread of computers first and of smartphones later, the narrative touches on current issues in the contemporary public debate, including the tragedy of the deaths in the Mediterranean:

“That little rubbish it would not have caused the sea great suffering compared to everything that was thrown into every day: plastic, toxic waste, sewage purging. But it certainly had suffered for the thousands of thousands of bodies of desperate people, of people dead in the sea while the were trying to reach the Italian coast to escape from war or to obtain a piece of bread”. Footnote 22

In Camilleri’s work, modernity reaches even the most remote areas of Sicily; but it does so through a process of cultural negotiation that requires bending, in turn, to the Sicilian context.

Izzo and Montale’s Marsiglia

The inventor of the very definition of Mediterranean noir, Jean Claude Izzo (1945–2000) is the third exponent of the sub-genre here in question. He was born in Marseille to a family that represents a perfect example of the many migratory waves coming from across the Mediterranean to settle in the city. His father, Gennaro, came from Southern Italy; his mother Isabelle, of French citizenship, descended from a Spanish family. In his youth he was active in several pacifist and socialist movements, until he became a municipal candidate for the French Communist Party. Although trained in professional schools, at the age of 24 he began to collaborate with the communist newspaper La Maseillaise Dimanche , of which he was editor-in-chief until 1980, when he moved to La Vie Mutualiste. Within French cultural circles, his renown as a poet grew to the point that he moved to Paris where he worked as a columnist, became the organizer of literary events and a film author (Dhoukhar, 2006 ).

In 1993, he made his debut in the world of detective stories with a short story featuring the investigator Fabio Montale, who was to become the protagonist of the so-called “Marseille Trilogy”, published between 1995 and 1998. In 2000, at the age of 54, an illness took his life. After his death, a collection of short writings and articles was published in the volume Marseille , which represents a sort of poetic manifesto of his cultural vision of the Mediterranean (Matalon, 2020 ).

The three books share the same setting, Marseille. In chronological succession, the plots follow the events around the protagonist Montale (a surname inspired by the Italian poet, winner of the Nobel Prize) as he has to deal with French, Italian and Algerian organized crime, collusive politicians, and the rise of new social actors amidst the rapid urban developments of the largest port of the Mediterranean. Montale too comes from a social context of immigration and marginalization. Unlike his childhood friends, however, he chooses to join the police in order to fight the injustice that has lead his peers to criminal life, while trying to keep his values intact. A shy and tormented antihero according to the Chandlerian paradigm, just as his counterparts Carvalho and Montalbano he has a passion for women, literature, good food and wine.

Because of the death of two friends and of a beloved woman in the first volume of the trilogy, as an outsider policeman with acquaintances in the suburbs Montale feels compelled to dive into the local underworld: the Neapolitan mafia and the Front National. Instead of a positive resolution of the case, the mutual killing between the antagonistic factions in the ending leads him to the bitter conclusion that “the only plot is the hatred of the world”. Footnote 23 The sense of loathing induced by the epilogue is so strong that in the second book Montale has resigned from the police force and retired to private life. Yet the accidental murder of his cousin’s son forces him to contend with the criminal world again. In this case as well, two parallel stories intertwine, leading Montale to eventually confronting his past in addition to Arab fundamentalism and the Italian-French mafia. In the course of his personal war against organized crime, while trying to help an old lover, he will find his end in the epilogue of the third volume.

Methodologically, Montale is not a good deducer and often comes to wrong conclusions. He harshly admits that “as a detective, I was still not worth shit. I went forward by intuition, but without ever giving myself time to reflect”. Footnote 24 The storyline is rather to be found in the action, in the exploration of all layers of Marseillaise society, in the scattered search of a bundle to unravel. That is the reason why it has been noted about Izzo’s novels that “la ville n’y est pas un décor où se déroule l'enquête […] est l'object de la quête du héros qui redécouvre la ville” (Rosemberg & Troin, 2017 , 3). Montale travels across all the most famous areas of Marseille, from the port to the Calanques, topographically described in such detail that the Triology texts can be seen as a laboratory for experimenting with methodologies of literary cartography (Rosemberg, 2007 ; Rosemberg & Troin, 2017 ), which can also be consulted through GoogleMaps. Footnote 25 Besides, the stories involve conflictual spaces such as the suburbs with a high concentration of immigrants, where the social and intercultural conflict emerges at its fullest: spaces like La Paternelle, hastily described as “A Magrebin town. Not the hardest […] Like another continent”, Footnote 26 or the historic city center, where “the fear of the Arabs had made the Marseillais flee towards less central neighborhoods, where they felt safer […] Streets of whores. With unhealthy buildings and lousy hotels. Every migration had passed through those streets. Until a restructuring would have sent everyone to the suburbs”. Footnote 27

However, any social criticism in the books fails to hide the extremely positive appreciation about the aesthetics of the social and urban context, mainly due to Marseille’s vocation as a port and “gateway to the East. Other place, Adventure, dream” Footnote 28 as well as space of communication, “crossroads of all human mixes”, Footnote 29 historically open and tolerant. The city is favorably presented as the actual synthesis of the exchanges between the myriad cultures of the Mediterranean, which make it resemble more to the Italian seaside towns than to the northern French: “Italian Marseille. The same smells, the same laughter, the same bursts of voices from the streets of Naples, Palermo or Rome”). Footnote 30 Traces of such multicultural crossbreeding can therefore be found in many elements of the urban landscape and life: in the language, “a curious French, a mixture of Provençal, Italian, Spanish, Arabic, with a hint of slang and some of verlan” Footnote 31 ; in its characteristic smells, as “sometimes until the end of October, autumn retains an aftertaste of summer. A draft of air is enough to revive the scents of thyme, mint and basil” Footnote 32 ; in its music, “Arab music […] Oud spread through the bush like a smell. The sweet smell of oases. Dates, dried figs, almonds” Footnote 33 ; in the cuisine, fusing local dishes with those imported by migrants. Food plays a vital role in the narrative: cooking, eating and drinking is the moment of collective sharing and of inner catharsis at the same time, a sanctuary which Montale seeks every time he finds himself the witness to a heinous act.

Montale presents himself as the guardian (who will ultimately be defeated) of a world at its sunset hour, threatened not only by crime and corruption, but also by a process of cultural globalization that aims to erase Mediterranean traditions in the name of an alleged European homogeneity:

“Marseille had a future only if it gave up its history. This they explained to us. And when we talked about port renewal, it was to legitimize the necessity to finish with this port as it was today. The symbol of ancient glory […] they would raze the hangars to the ground […] And remodeled the maritime landscape. This was the last great idea. The new big priority. The maritime landscape […] ‘now I’ll explain. When they start talking to you about city center generosity, you can be shure they mean everyone out. Away! The Arabs, the Comorians, the blacks. In short, everything that tarnishes. And the unemployed, and the poor … Out!’”. Footnote 34

Discussion: from the crime space to the crime place

Literary criticism on crime fiction has long remarked that over the years the genre has undergone a fundamental transformation in terms of form and content, interpreted as the result of the postmodernist crisis of reason (Rzepka, 2005 ).

The initial phase of the detective novel history referred to in the second paragraph above reflected an absolute rationalist faith in the mind’s power. In the second chapter of A Study in Scarlet , Conan Doyle has Holmes explain the science of investigative deduction: according to the investigator, “deceit is an impossibility in the case of one trained to observation and analysis” ( 1887 , 23–24). With respect to this stage of evolution of detective stories, Julian Symons points out that writers had to structure the plot development so as to answer three essential questions: “Who, Why and When” (Symons, 1962 , 8), while Roger Callois claims that “How” was at the core of the questioning (Callois, 1983 , 4).

Admittedly, Dupin, Holmes and Poirot all adopt a comparable approach in analyzing the crime scene. The detective story unfolds in a space that is intended as a frame for tangible elements (objects and people) through which the rational mind logically reconstructs the causal relationships that connect clues, facts and events.

The first geographer who considered detective fiction as a case study was Yi -Fu Tuan, who addressed Holmes stories. While highlighting the important role of the Victorian world in the narrative defined by a “dark London” metropolis, exotic characters, and worldwide travels, Tuan ( 1985 ) argued that Conan Doyle’s success lies in the reason’s capacity to solve mysteries and restore order in a rapidly changing world (Hones, 2010 ). In addition, as a specific literary feature in the canon, he noticed that murder scenes are always described as obscure and sinister; so are criminals, who “are marked by some sinister physiognomic trait” (Tuan, 1985 , 59).

In fact, the territorial context identified by Tuan is always a background aspect. When looking only at the storyline – the collection of evidence and the deductive process – the murder of the Rue Morgue could have been committed anywhere, just as the investigation on the Orient Express could have been conducted in any enclosed space. Even in the stories where the setting holds a greater importance, such as the Colorado desert in A Study in Scarlett or the moor of the Baskervilles, the landscape descriptions mainly serve a decorative purpose, as backdrop for the plot.

As subsequently shown in this paper, however, the role of geography in later crime fiction changed completely. Sheila Hones ( 2011 ) has acutely pointed out that the story setting is not any more merely a “general socio-historico-geographical environment” working as framework for the action. In the examples considered in previous paragraphs about the selected cycles, Pepe Carvalho, Salvo Montalbano and Fabio Montale are one with their home territories – Barcelona, Sicily, and Marseille respectively.

The connection between the description of the crime scene and the deductive process is missing for the most part, as becomes clear already from Camilleri’s first book where the inspector’s surveys leave out any details so as to give prominence to the landscape context: “the Commissioner lit a cigarette, turned to look towards the chemical factory. That ruin fascinated him. He decided that one day he would return to take photographs”. Footnote 35 As a matter of fact, Carvalho, Montalbano, and Montale succeed in solving cases not so much because they are good at piecing clues together, but mostly because they are able to interpret them in the light of the practices and conduct laws that govern the local society and mindset, of which they have a deep understanding. In a metafictional passage, Montalbano himself says:

“‘Priestley is an author known for his ability to write para-detective works. What does it mean? It means that on the surface they look like crime plots but in reality they are profound investigations into the soul of contemporary man’. Montabano argued that a cop not able to understand the soul of the human beings would not be a good cop”. Footnote 36

To analyze social, political and cultural problems of their territories, Montalbán, Camilleri and Izzo need the topographical description of Barcelona, of the imaginary Vigata or of Marseille as a privileged observatory from which constructing the representation of the society they know so well (Pezzotti, 2012 ). Therefore, the investigation continues to function as the narrative guiding thread, but it loses its primary relevance: murder and theft are only the trigger for the detectives’ work, which involves reading the landscape, self-reflection, and socio-geographical and psychological analyses.

It has been pointed out that “rather than the crime perpetrator, Montalbano investigates the Sicilian territory and identity” (Pezzotti, 2012 ). As a matter of fact, Mediterranean noirs also introduce new variations on the themes typical to classic noir, such as the problem of the isolation of the individual and the crisis of the subject in its relationship with the world. Investigation as a narrative key is retained, but with the aim of recontextualizing it. The plot is triggered by strolls in the local territory, sometimes even depicted in a nostalgic vein with different narrative techniques. The new canons tend to externalize what classic noir had internalized, extending the investigation out of the individual and into society. Behind the description of the setting emerges a need to reflect on the context itself and do so through the narrative involvement of the investigation, seeking to reach deeper insight and hidden truths. The investigation continues to function as a narrative guideline, but it loses its primary relevance: murder and theft are only the trigger for the detectives’ work, which involves reading the landscape, self-reflection, and socio-geographical and psychological analyses.

In fact, what differentiates Mediterranean writers from classical ones and partially explains the importance of locality is the strong sentiment of belonging with which place-settings are invested. As Elaine Stratford and Marco Antonsich suggest, “belonging” could be interpreted as an intimate identification process involving personal biography and symbolic or material spaces (Antonsich, 2010b ; Stratford, 2009 ). Such connection appears to be crucial in Montalban, Camilleri and Izzo’s act of writing: not only they all have settled their stories in the place where they come from, but have also acknowledged similarities between the protagonists’ lives and their own.

From the analysis of these authors’ writings, it is therefore possible to shed new light on the development of those literary topoi which have become the books hallmarks and that stem from the authors’ attachment to their home-region. In this regard, the Izzo’s collection of essays Marseille ( 2000 ) represents a sort of manifesto pinpointing most of the topoi that characterize space. A common thread throughout the three cycles thereby becoming an intrinsic part of the local culture in the collective imagination, such topoi include different territorial elements.

First, the social struggle within the locality: all three detectives are ideologically left-wing, part of or open to the lower strata of society. After all, Montalbán, Camilleri and Izzo share with Chandler his critique of capitalism based on the underlying assumption that the current economic system increases inequalities, corrupts the people and leads to crime (Broe, 2014 ).

Secondly, the clash between local identities and the consequences of globalization and modernity. Carvalho helplessly witnesses the transformation of his city into a European metropolis that eventually yields to the advocates of an artificial Catalanism, which is in turn fostered by international capital. Montalbano is troubled by the erasure of old Sicily values, uneasy in dealing with new technologies, horrified by the consequences of naval blockades in the Mediterranean. Montale’s ideological aim is to prevent Marseille transformation from a gateway into a frontier between the wealthy North and the poor South. In this sense, Izzo clearly claims the existence of a Mediterranean culture with common roots that is currently in danger (Izzo, 2000 ).

Thirdly, the relationship with the sea as a geographical expression of the common roots. The stories all take place in maritime areas and all three main characters have a habit to plunge into the waters of the sea, especially in difficult times. Swimming in Mediterranean becomes a cathartic purifying process of inner reflection: in the words of Izzo “we know very well that it is our sea which unites us” (Izzo, 2000 , 79).

Fourth, local cuisine. The investigators are all food connoisseurs and their habit of having lunch always in the same places reflects their view of eating as a communitarian, almost familiar action: the rituals that they perform during lunch (i.e. being silent, tasting each flavor, localize ingredients etc.) make the meal an act of conviviality and regional ritualism. Thus, the role attributed to food and to the act of eating as an instrument of identity, a way to create and maintain strong roots, is a paradigmatic example of how space becomes place by assuming the connotation of feelings, culture and traditions (Bakhtiarova, 2020 ; Michelis, 2010 ).

It can therefore be said that these elements, including the landscape descriptions of the countryside and of urban neighborhoods, the language, the sea, the local cuisine, and social classes stratigraphy related to specific spaces are all viewed through the emotional prism of the writers’ attachment to their land, even more so than through the characters’.

Conclusion: the crime place as production of locality

Crime and detective fiction offers to literary geography an intriguing field of research. Firstly, exploration and investigation-based plots facilitate the depiction of space and society in a semi-documentary approach. In the second place, geographies are represented from the protagonist’s (and sometimes from the writer’s) point of view, which allows the identification of personal and collective images, feelings and ideas with which the space is invested. In the third place, due to their popular success, it is possible to consider these books as vectors for the transmission and consolidation of such images.

In his attempt to classify and systematize literary geographies, Anderson ( 2010 ) suggests five key questions for an assemblage approach to intertwined fictional and physical worlds, with regard to intra-textual, intertextual, and extra-textual geographies. Following his line, the paper has explored the relation between narrative and space in crime fiction.

In this respect, crime fiction stories like Montalban, Camilleri and Izzo’s allow the readership to identify a Mediterranean noir inter-textual literary space thanks to the citation of names, to the references to common geographical locations of authors and settings, and to the description of recognisable territorial elements and meanings. The very definition of “Mediterranean noir” used to label them is based on a geographical criterion and would even be incorrect from a formal perspective, at least in the case of Camilleri’s books, which cannot be considered noir strictu sensu.

Regarding the intra-textual perspective, Geoffrey Hartman noted that “to solve a crime in detective stories means to give it an exact location: to pinpoint not merely the murderer and his motives but also the very place, the room, the ingenious or brutal circumstances” (Hartman, 1999 , 212). However, this assumption seems inadequate to define more recent detective stories, where the solving of the crime is not as central as it used to be. What we argue is that the very center is now the location itself: the place needs a crime story just to be showcased. The identification of the detective with a specific place is reinforced by the reiteration of crime stories settled in the same area over different cycles. In this sense, Rosemberg and Troin ( 2017 ) have observed that recent detective stories are more similar to travel stories than to investigations. A different geography supports the novels, where the topography of space is no longer as relevant as the chorography of place, that is to say the social, cultural, environmental, collective and psychological structures that shaped it. As opposed to the investigations of Sherlock Holmes or Poirot, Carvalho, Montalbano and Montale’s stories could not be set elsewhere, because they originate from the very context of the narrative. Unlike American detective stories where the detective represents the centrality of the individual in a mass society, the characteristic that enhances the ability of Mediterranean noir to spur ideas of locality is the celebration of a collective sense of community.

In Carvalho, Montalbano and Montale’s investigations, belonging and local identities emerge as key components of the story and the plot, resulting in the construction of new ideas of narrated territories. Consequently, due to the genre’s popularity in mass culture, the making of extra-textual geographies and of relations between people and place – in other words, their literary or factual impact on a specific place – needs to be studied with an eye on text reception. This particular type of narrative structure responded to the necessity of Italian, Spanish, and French readers, confronted with globalisation processes, to recognise chosen elements of identity as keys to read their territory while taking into account their cultural roots. In the same years in which the discussion about locality was growing, Mediterranean noir then claimed a vantage point to reflect on and interpret these processes.

Literature has been acknowledged to possess the potential to create discourses of local identity (Hones, 2008 ; Ridanpää, 2019 ). Such anthropological theory can be effectively applied to the new trends in crime fiction in order to explain their genesis and the success which they have met with the general public, even as cinematographic transpositions. In this respect, the adventures of Carvalho, Montalbano and Montale have also been reified as promotional tools for the territories they represent. In Barcelona, for instance, many package tours have been organized to let tourists rediscover the places of Montalbán (Redondo, 2017 ). Similarly, in Italy, the significant increase in tourist flux to the province of Agrigento – where the Montalbano television series was shot – has even led tourism sciences to coin the expression “Montalbano effect” (Di Betta, 2015 ; Ponton & Asero, 2015 ). Unlike Sherlock Holmes’, however, the author’s and the character’s houses are not the only tourist attractions: the entire territory narrated in the fiction continues to capture the interest of the public. While Robert Rushing has explained the success of detective fiction in terms of satisfaction of inner desires ( 2007 ), the very setting should be considered as a crucial factor for the understanding of popular reception. It is not a coincidence that, over the years, several other Italian cities and regions have become the set for detective stories of lesser or greater literary value, the topoi of which were not far from those identified above. As demonstration of the performative power of fiction, in 2003 the Municipality of Porto Empedocle had decided to change the name of the city in “Porto Empedocle Vigata”, a decision later revoked in 2009.

The new role and function assigned to place in Mediterranean crime stories are not only a fascinating practice of literature, but also a cultural and geographical phenomenon. This paper proposes to interpret this phenomenon as a discourse of production of local identities with respect to the problem of globalization. The way in which globalization has, on the one hand, complicated the modern configurations of identity and, on the other, sparked disagreement about the contents of such category, has been widely discussed (Browning and Ferraz de Oliveira, 2017 ; Rembold and Carrier, 2011 ; Terlouw, 2012 ). In Modernity at Large ( 1996 ), Appadurai linked the topics of modernity/modernization and globalization to daily social practices. In contrast to the prediction of a global homogenization and leveling of identities, the anthropologist convincingly argues that in the face of modernization and globalization processes, human groups react by re-producing local identities and seeking affiliations of smaller groups. Appadurai demonstrates that globalization does not necessarily lead to the leveling of differences; on the contrary, it can trigger resilient responses. Thus, locality represents the result of a work of context interpretation and enhancement conducted by agents who develop strategies and construct identity discourses through the selection of social categories, symbols and contents capable of identifying a place (Escobar, 2001 ).

It is interesting to notice that in our case study the production of image happens at multiple levels. At a local scale, by describing the environment as a setting for the ethnographic investigations/journeys of their protagonists in a relational space, Montalbán, Camilleri and Izzo tend to represent their own idea of Barcelona, Sicily and Marseille respectively. For this purpose, they select some of the geographical elements that they perceive as typical, thereby conveying a constructed image and subsequently developing a geographical discourse. At chorographic scale, such selected elements are mostly the same and reinforce the perception of a common and shared Mediterranean, which builds on Fernand Braudel’s concept of a unified culture between the different shores of the sea. Thus, the writers work on a multiple scale, developing a discourse that connects local identities in a broader Mediterranean one: in the words of Izzo, a “Mediterranean creolity” (Izzo, 2000 , 43).

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

In literary sciences there is a wide debate on the different definitions of detective fiction, crime story, thriller and noir. For the purpose of this paper, I adopt the general definition of detective fiction as a “narrative whose principal action concerns the attempt by an investigator to solve a crime and to bring a criminal to justice” (Herman, Jahn and Ryan, 2010 ).

The definition of “classic detective fiction” to define 19th century crime fiction focusing on an investigator and the story of his investigations has been borrowed by Marty Roth ( 1995 ).

“Aquel hombre alto, moreno, treintañero, algo desalineado a pesar de llevar ropas caras de sastrería del Ensanche” (Montalbán, 1974 , 20). A literal translation into English is provided for all quotes in this paper.

“Acaso un policía como yo no es un sociólogo?” (Montalbán, 1974 , 119).

“Sentimiento contrario le despertaba Vía Layetana con su aspecto de primer e indeciso paso para iniciar un Manhattan barcelonés, que nunca llegaría a realizarse. Era una calle de entreguerras, con el puerto en una punta y la Barcelona menestral de Gracia en la otra, artificialmente abierta para hacer circular el nervio comercial de la metrópoli y con el tiempo convertida en una calle de sindicatos y patronos, de policías con sus victimas, mas alguna Caja de Ahorros y el monumento entre jardines sobre fondo gotizante a uno de los condes mas sólidos de Cataluña” (Montalbán, 1979 , 36).

“Si la guerra de los Treinta Años no hubiera sentenciado la hegemonía de Francia en Europa, la cocina francesa a estas horas padecería la hegemonía de las cocinas de España. Su único patriotismo era gastronómico” (Montalbán, 1979 , 63).

“En la matriz de la Cataluña esencial: el pan con tomate, el cava, las seques amb botifarra , la escudella i carn d’olla” (Montalbán, 1988 , 32).