Revolutionize Your Research with Jenni AI

Literature Review Generator

Welcome to Jenni AI, the ultimate tool for researchers and students. Our AI Literature Review Generator is designed to assist you in creating comprehensive, high-quality literature reviews, enhancing your academic and research endeavors. Say goodbye to writer's block and hello to seamless, efficient literature review creation.

Loved by over 1 million academics

Endorsed by Academics from Leading Institutions

Join the Community of Scholars Who Trust Jenni AI

Elevate Your Research Toolkit

Discover the Game-Changing Features of Jenni AI for Literature Reviews

Advanced AI Algorithms

Jenni AI utilizes cutting-edge AI technology to analyze and suggest relevant literature, helping you stay on top of current research trends.

Get started

Idea Generation

Overcome writer's block with AI-generated prompts and ideas that align with your research topic, helping to expand and deepen your review.

Citation Assistance

Get help with proper citation formats to maintain academic integrity and attribute sources correctly.

Our Pledge to Academic Integrity

At Jenni AI, we are deeply committed to the principles of academic integrity. We understand the importance of honesty, transparency, and ethical conduct in the academic community. Our tool is designed not just to assist in your research, but to do so in a way that respects and upholds these fundamental values.

How it Works

Start by creating your account on Jenni AI. The sign-up process is quick and user-friendly.

Define Your Research Scope

Enter the topic of your literature review to guide Jenni AI’s focus.

Citation Guidance

Receive assistance in citing sources correctly, maintaining the academic standard.

Easy Export

Export your literature review to LaTeX, HTML, or .docx formats

Interact with AI-Powered Suggestions

Use Jenni AI’s suggestions to structure your literature review, organizing it into coherent sections.

What Our Users Say

Discover how Jenni AI has made a difference in the lives of academics just like you

· Aug 26

I thought AI writing was useless. Then I found Jenni AI, the AI-powered assistant for academic writing. It turned out to be much more advanced than I ever could have imagined. Jenni AI = ChatGPT x 10.

Charlie Cuddy

@sonofgorkhali

· 23 Aug

Love this use of AI to assist with, not replace, writing! Keep crushing it @Davidjpark96 💪

Waqar Younas, PhD

@waqaryofficial

· 6 Apr

4/9 Jenni AI's Outline Builder is a game-changer for organizing your thoughts and structuring your content. Create detailed outlines effortlessly, ensuring your writing is clear and coherent. #OutlineBuilder #WritingTools #JenniAI

I started with Jenni-who & Jenni-what. But now I can't write without Jenni. I love Jenni AI and am amazed to see how far Jenni has come. Kudos to http://Jenni.AI team.

· 28 Jul

Jenni is perfect for writing research docs, SOPs, study projects presentations 👌🏽

Stéphane Prud'homme

http://jenni.ai is awesome and super useful! thanks to @Davidjpark96 and @whoisjenniai fyi @Phd_jeu @DoctoralStories @WriteThatPhD

Frequently asked questions

What exactly does jenni ai do, is jenni ai suitable for all academic disciplines, is there a trial period or a free version available.

How does Jenni AI help with writer's block?

Can Jenni AI write my literature review for me?

How often is the literature database updated in Jenni AI?

How user-friendly is Jenni AI for those not familiar with AI tools?

Jenni AI: Standing Out From the Competition

In a sea of online proofreaders, Jenni AI stands out. Here’s how we compare to other tools on the market:

Feature Featire

COMPETITORS

Advanced AI-Powered Assistance

Uses state-of-the-art AI technology to provide relevant literature suggestions and structural guidance.

May rely on simpler algorithms, resulting in less dynamic or comprehensive support.

User-Friendly Interface

Designed for ease of use, making it accessible for users with varying levels of tech proficiency.

Interfaces can be complex or less intuitive, posing a challenge for some users.

Transparent and Flexible Pricing

Offers a free trial and clear, flexible pricing plans suitable for different needs.

Pricing structures can be opaque or inflexible, with fewer user options.

Unparalleled Customization

Offers highly personalized suggestions and adapts to your specific research needs over time.

Often provide generic suggestions that may not align closely with individual research topics.

Comprehensive Literature Access

Provides access to a vast and up-to-date range of academic literature, ensuring comprehensive research coverage.

Some may have limited access to current or diverse research materials, restricting the scope of literature reviews.

Ready to Transform Your Research Process?

Don't wait to elevate your research. Sign up for Jenni AI today and discover a smarter, more efficient way to handle your academic literature reviews.

Something went wrong when searching for seed articles. Please try again soon.

No articles were found for that search term.

Author, year The title of the article goes here

LITERATURE REVIEW SOFTWARE FOR BETTER RESEARCH

“Litmaps is a game changer for finding novel literature... it has been invaluable for my productivity.... I also got my PhD student to use it and they also found it invaluable, finding several gaps they missed”

Varun Venkatesh

Austin Health, Australia

As a full-time researcher, Litmaps has become an indispensable tool in my arsenal. The Seed Maps and Discover features of Litmaps have transformed my literature review process, streamlining the identification of key citations while revealing previously overlooked relevant literature, ensuring no crucial connection goes unnoticed. A true game-changer indeed!

Ritwik Pandey

Doctoral Research Scholar – Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning

Using Litmaps for my research papers has significantly improved my workflow. Typically, I start with a single paper related to my topic. Whenever I find an interesting work, I add it to my search. From there, I can quickly cover my entire Related Work section.

David Fischer

Research Associate – University of Applied Sciences Kempten

“It's nice to get a quick overview of related literature. Really easy to use, and it helps getting on top of the often complicated structures of referencing”

Christoph Ludwig

Technische Universität Dresden, Germany

“This has helped me so much in researching the literature. Currently, I am beginning to investigate new fields and this has helped me hugely”

Aran Warren

Canterbury University, NZ

“I can’t live without you anymore! I also recommend you to my students.”

Professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong

“Seeing my literature list as a network enhances my thinking process!”

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium

“Incredibly useful tool to get to know more literature, and to gain insight in existing research”

KU Leuven, Belgium

“As a student just venturing into the world of lit reviews, this is a tool that is outstanding and helping me find deeper results for my work.”

Franklin Jeffers

South Oregon University, USA

“Any researcher could use it! The paper recommendations are great for anyone and everyone”

Swansea University, Wales

“This tool really helped me to create good bibtex references for my research papers”

Ali Mohammed-Djafari

Director of Research at LSS-CNRS, France

“Litmaps is extremely helpful with my research. It helps me organize each one of my projects and see how they relate to each other, as well as to keep up to date on publications done in my field”

Daniel Fuller

Clarkson University, USA

As a person who is an early researcher and identifies as dyslexic, I can say that having research articles laid out in the date vs cite graph format is much more approachable than looking at a standard database interface. I feel that the maps Litmaps offers lower the barrier of entry for researchers by giving them the connections between articles spaced out visually. This helps me orientate where a paper is in the history of a field. Thus, new researchers can look at one of Litmap's "seed maps" and have the same information as hours of digging through a database.

Baylor Fain

Postdoctoral Associate – University of Florida

Literature Review Generator by AcademicHelp

Features of Our Literature Review Generator

Advanced power of AI

Simplified information gathering

Enhanced quality

Rrl generator – your friend in academic writing.

Literature reviews can be tricky. They require your full attention and dedication, leaving no place for distractions. And with so many assignments on your hands, it must be very hard to concentrate just on this one thing.

No need to worry though. With our RRL AI Generator creating any type of paper that requires scrupulous literature will be as easy as it gets.

How to Work With Literature Review Generator

We designed our platform in a way that wouldn’t require you to spend much time figuring out how to work with it. What you have to do is just specify your topic, the subject of your literature review, and any further instructions on the style, formatting, and structure. After that you enter the number of pages you need to be written and, if there’s a requirement for that, formatting style. Wait for around 2 minutes and that’s all – our AI will give you the paper crafted according to your specifications.

What Makes AI Literature Review Generator Special

You are probably wondering how our AI bot is better than basically any other AI-powered solution you can find online. Well, we won’t say that our tool is a magical service that can do everything better. To be fair, as any AI it is not yet ideal. Still, our platform is more tailored to academic writing than most of the other bots. With its help, you can not just simply produce text, but also receive a paper with sources and properly organized formatting. This makes it a perfect match for those who specifically need help with tough papers, such as literature reviews, research abstracts, and analysis essays.

Why Use the Free Online Literature Review Generator

With our Free Online Literature Review you will be able to finish your literature review assignments in just a few minutes. This will allow you to dedicate your free time to a) proofreading, and b) finishing or starting on more important tasks and projects. This tool can also help you understand the direction of your work, its structure, and possible sources you can use. In general, it is a more efficient way of doing your homework and organizing the writing process that can help you get better grades and improve your writing skills.

Free Literature Review Generator

Is there a free AI tool for literature review?

Yes, of course, some tools will help you with your literature review. One of the great solutions is the AcademicHelp Literature Review Generator. It offers a quick and simple work process, where you can specify all the requirements for your paper, and then receive a fully completed task in just 2 minutes. It is a specially fitting service for those looking for a budget-friendly tool.

How to create a literature review?

Crafting a literature review calls for a systematic approach to examining existing scholarly work on a specific topic. Thus, start by defining a clear research question or thesis statement to guide your focus. Conduct a thorough search of relevant databases and academic journals to gather sources that address your topic. Read and analyze these sources, noting key themes, methodologies, and conclusions. Organize the literature by themes or methods, and synthesize the findings to provide a critical overview of the existing research. Your review should give context to the research within the field, noting areas of consensus, debate, and gaps in knowledge. Finally, write your literature review, integrating your analysis with your thesis statement, providing a clear and structured narrative that offers insights into the research topic.

Can I write a literature review in 5 days?

It is possible to write a literature review in 5 days, but you will need careful planning and dedication. Start by quickly defining your topic and research question. Dedicate a day to intensive research, finding and selecting relevant sources. Spend the next two days reading and summarizing these sources. On the fourth day, organize your notes and outline the review, focusing on arranging the main findings around key themes. Use the final day to write and revise your literature review, so that it is logically structured.

What are the 5 rules for writing a literature review?

When writing a literature review, you initially need to follow these essential rules: First, maintain a clear focus and structure. Your review should be organized around your thesis statement or key question, with each section logically leading to the next. Second, be critical and analytical rather than merely descriptive. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the research, the methodologies used, and the conclusions drawn. Third, include credible and versatile sources to represent a balanced view of the topic. Fourth, synthesize the information from your sources to create a narrative that adds value to your field of study. Finally, your writing should be clear, concise, and plagiarism-free, with all the sources appropriately cited.

Remember Me

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

Your all in one AI-powered Reading Assistant

A Reading Space to Ideate, Create Knowledge, & Collaborate on Your Research

- Smartly organize your research

- Receive recommendations that can not be ignored

- Collaborate with your team to read, discuss, and share knowledge

From Surface-Level Exploration to Critical Reading - All at One Place!

Fine-tune your literature search.

Our AI-powered reading assistant saves time spent on the exploration of relevant resources and allows you to focus more on reading.

Select phrases or specific sections and explore more research papers related to the core aspects of your selections. Pin the useful ones for future references.

Our platform brings you the latest research news, online courses, and articles from magazines/blogs related to your research interests and project work.

Speed up your literature review

Quickly generate a summary of key sections of any paper with our summarizer.

Make informed decisions about which papers are relevant, and where to invest your time in further reading.

Get key insights from the paper, quickly comprehend the paper’s unique approach, and recall the key points.

Bring order to your research projects

Organize your reading lists into different projects and maintain the context of your research.

Quickly sort items into collections and tag or filter them according to keywords and color codes.

Experience the power of sharing by finding all the shared literature at one place

Decode papers effortlessly for faster comprehension

Highlight what is important so that you can retrieve it faster next time

Find Wikipedia explanations for any selected word or phrase

Save time in finding similar ideas across your projects

Collaborate to read with your team, professors, or students

Share and discuss literature and drafts with your study group, colleagues, experts, and advisors. Recommend valuable resources and help each other for better understanding.

Work in shared projects efficiently and improve visibility within your study group or lab members.

Keep track of your team's progress by being constantly connected and engaging in active knowledge transfer by requesting full access to relevant papers and drafts.

Find Papers From Across the World's Largest Repositories

Testimonials

Privacy and security of your research data are integral to our mission..

Everything you add or create on Enago Read is private by default. It is visible only if and when you share it with other users.

You can put Creative Commons license on original drafts to protect your IP. For shared files, Enago Read always maintains a copy in case of deletion by collaborators or revoked access.

We use state-of-the-art security protocols and algorithms including MD5 Encryption, SSL, and HTTPS to secure your data.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

How I fled bombed Aleppo to continue my career in science

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

US halts funding to controversial virus-hunting group: what researchers think

News 16 MAY 24

Japan can embrace open science — but flexible approaches are key

Correspondence 07 MAY 24

US funders to tighten oversight of controversial ‘gain of function’ research

News 07 MAY 24

Mount Etna’s spectacular smoke rings and more — April’s best science images

News 03 MAY 24

Research Associate - Metabolism

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoc Fellowships

Train with world-renowned cancer researchers at NIH? Consider joining the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, Maryland

NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

PhD/master's Candidate

PhD/master's Candidate Graduate School of Frontier Science Initiative, Kanazawa University is seeking candidates for PhD and master's students i...

Kanazawa University

Senior Research Assistant in Human Immunology (wet lab)

Senior Research Scientist in Human Immunology, high-dimensional (40+) cytometry, ICS and automated robotic platforms.

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston University Atomic Lab

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

AI Literature Review Generator

Generate high-quality literature reviews fast with ai.

- Academic Research: Create a literature review for your thesis, dissertation, or research paper.

- Professional Research: Conduct a literature review for a project, report, or proposal at work.

- Content Creation: Write a literature review for a blog post, article, or book.

- Personal Research: Conduct a literature review to deepen your understanding of a topic of interest.

New & Trending Tools

In-cite ai reference generator, legal text refiner, job search ai assistant.

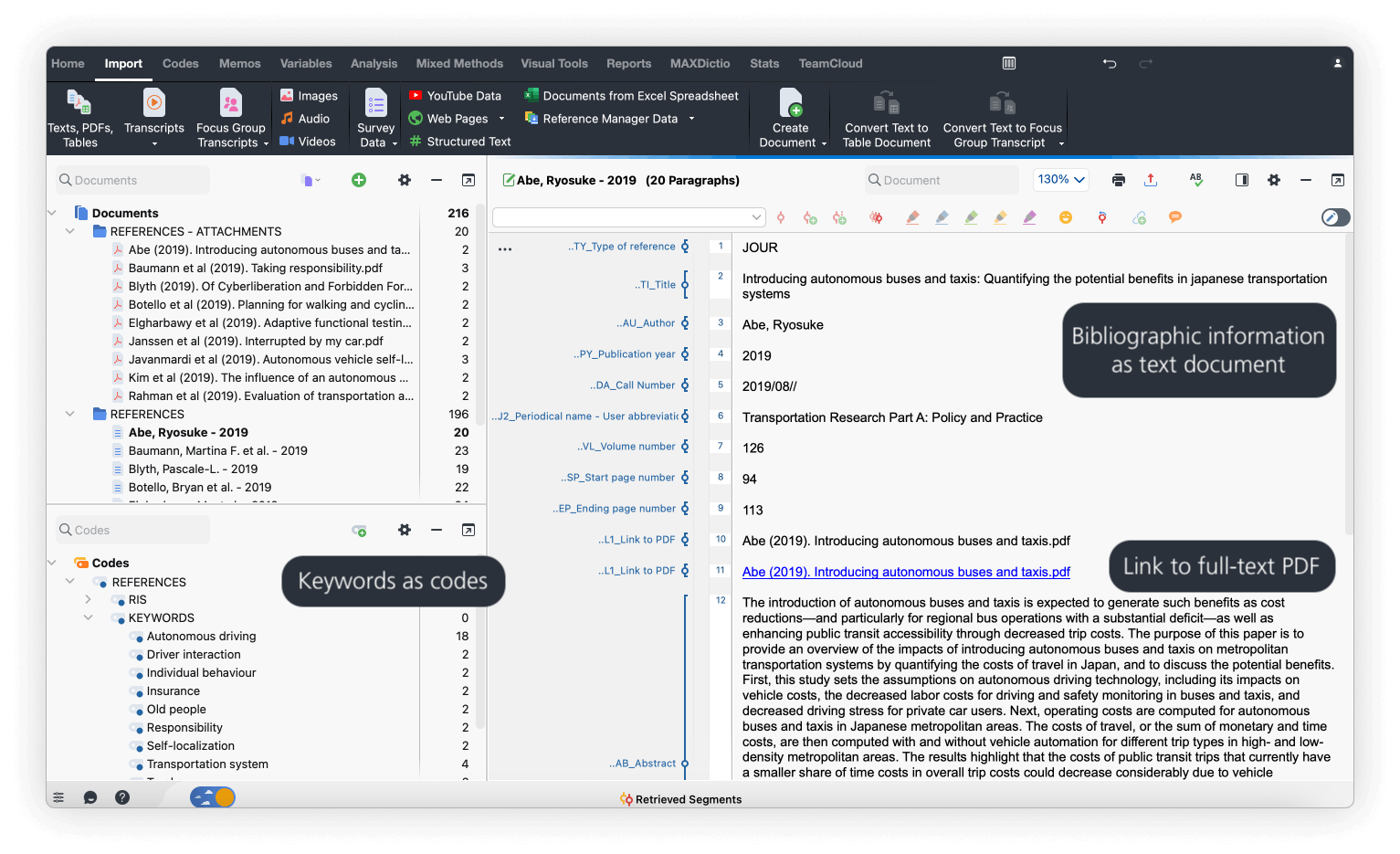

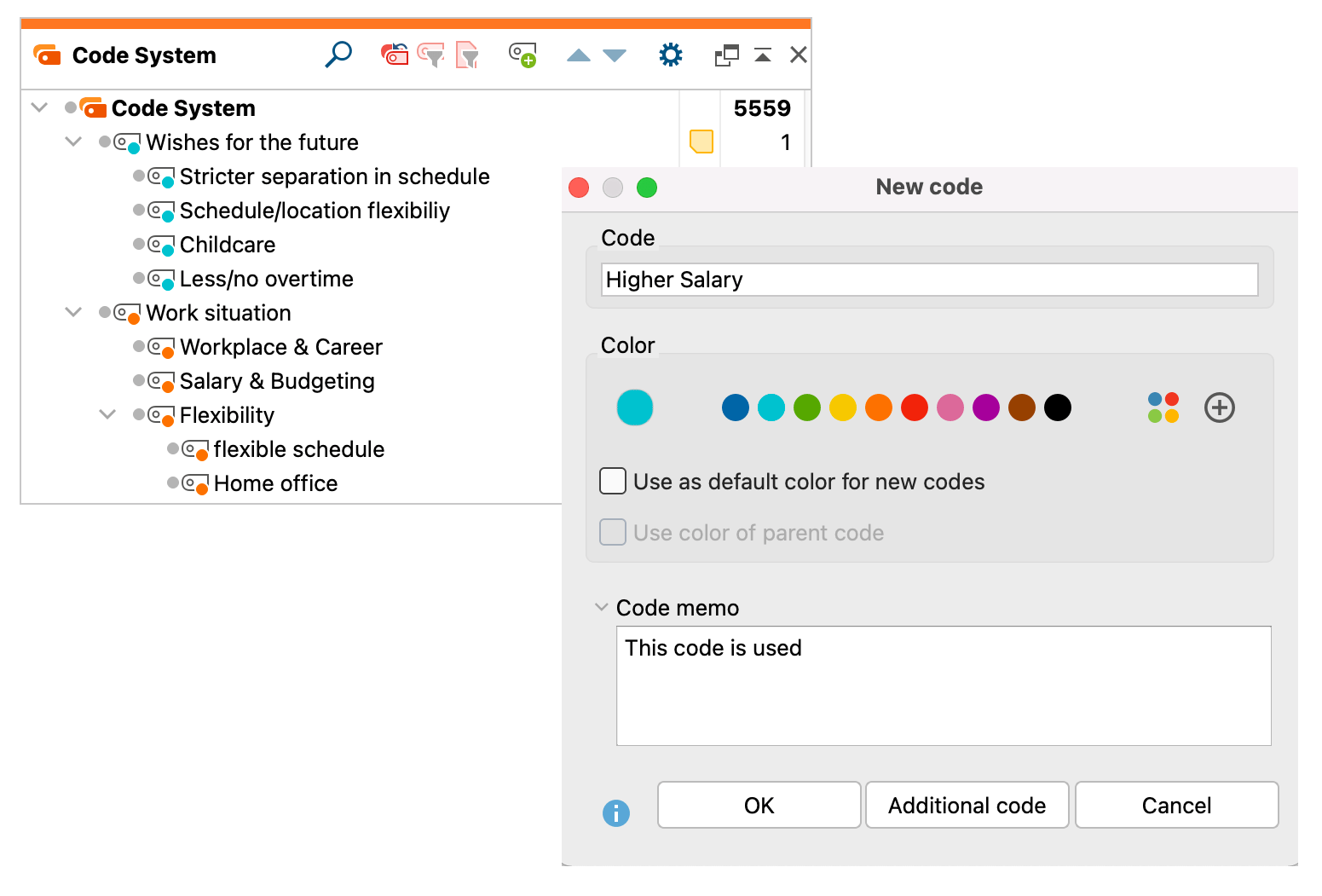

Literature Review with MAXQDA

Interview transcription examples, make the most out of your literature review.

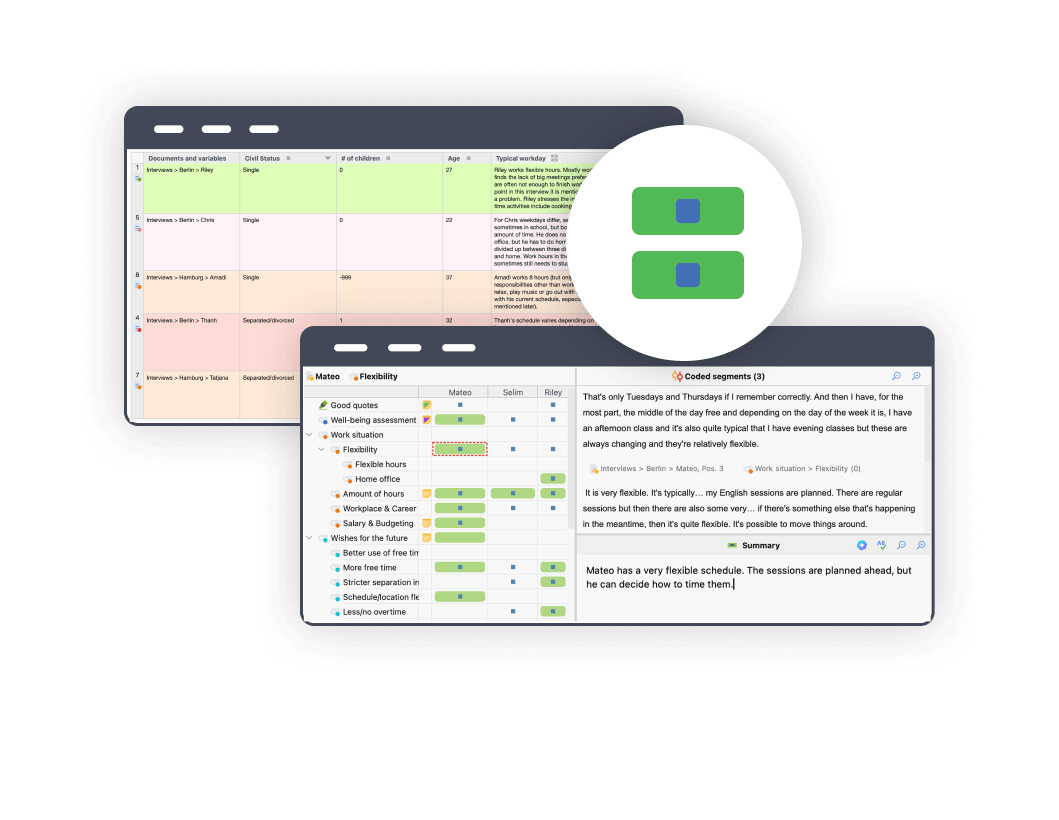

Literature reviews are an important step in the data analysis journey of many research projects, but often it is a time-consuming and arduous affair. Whether you are reviewing literature for writing a meta-analysis or for the background section of your thesis, work with MAXQDA. Our product comes with many exciting features which make your literature review faster and easier than ever before. Whether you are a first-time researcher or an old pro, MAXQDA is your professional software solution with advanced tools for you and your team.

How to conduct a literature review with MAXQDA

Conducting a literature review with MAXQDA is easy because you can easily import bibliographic information and full texts. In addition, MAXQDA provides excellent tools to facilitate each phase of your literature review, such as notes, paraphrases, auto-coding, summaries, and tools to integrate your findings.

Step one: Plan your literature review

Similar to other research projects, one should carefully plan a literature review. Before getting started with searching and analyzing literature, carefully think about the purpose of your literature review and the questions you want to answer. This will help you to develop a search strategy which is needed to stay on top of things. A search strategy involves deciding on literature databases, search terms, and practical and methodological criteria for the selection of high-quality scientific literature.

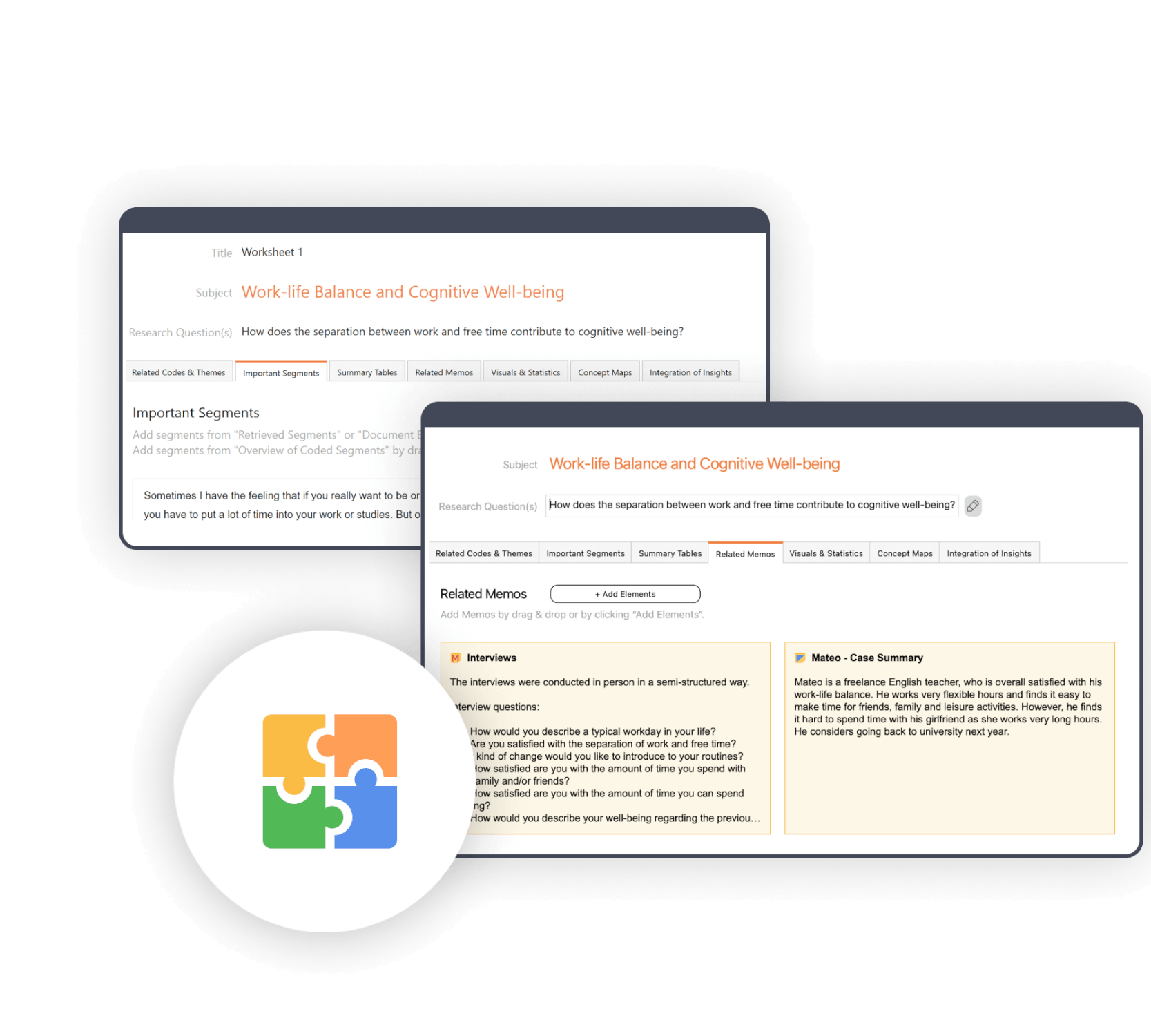

MAXQDA supports you during this stage with memos and the newly developed Questions-Themes-Theories tool (QTT). Both are the ideal place to store your research questions and search parameters. Moreover, the Question-Themes-Theories tool is perfectly suited to support your literature review project because it provides a bridge between your MAXQDA project and your research report. It offers the perfect enviornment to bring together findings, record conclusions and develop theories.

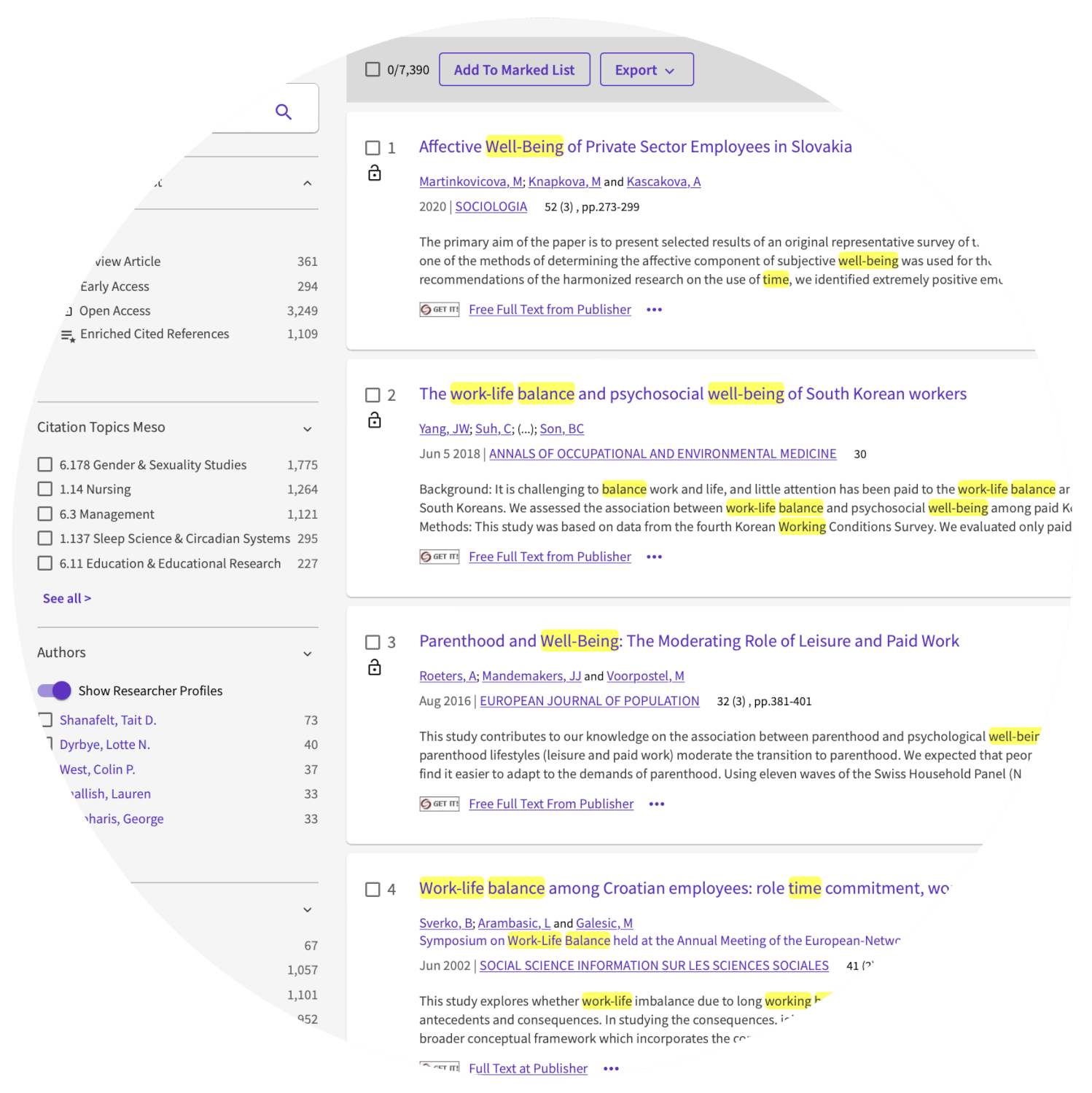

Step two: Search, Select, Save your material

Follow your search strategy. Use the databases and search terms you have identified to find the literature you need. Then, scan the search results for relevance by reading the title, abstract, or keywords. Try to determine whether the paper falls within the narrower area of the research question and whether it fulfills the objectives of the review. In addition, check whether the search results fulfill your pre-specified eligibility criteria. As this step typically requires precise reading rather than a quick scan, you might want to perform it in MAXQDA. If the piece of literature fulfills your criteria and context, you can save the bibliographic information using a reference management system which is a common approach among researchers as these programs automatically extract a paper’s meta-data from the publishing website. You can easily import this bibliographic data into MAXQDA via a specialized import tool. MAXQDA is compatible with all reference management programs that are able to export their literature databases in RIS format which is a standard format for bibliographic information. This is the case with all mainstream literature management programs such as Citavi, DocEar, Endnote, JabRef, Mendeley, and Zotero.

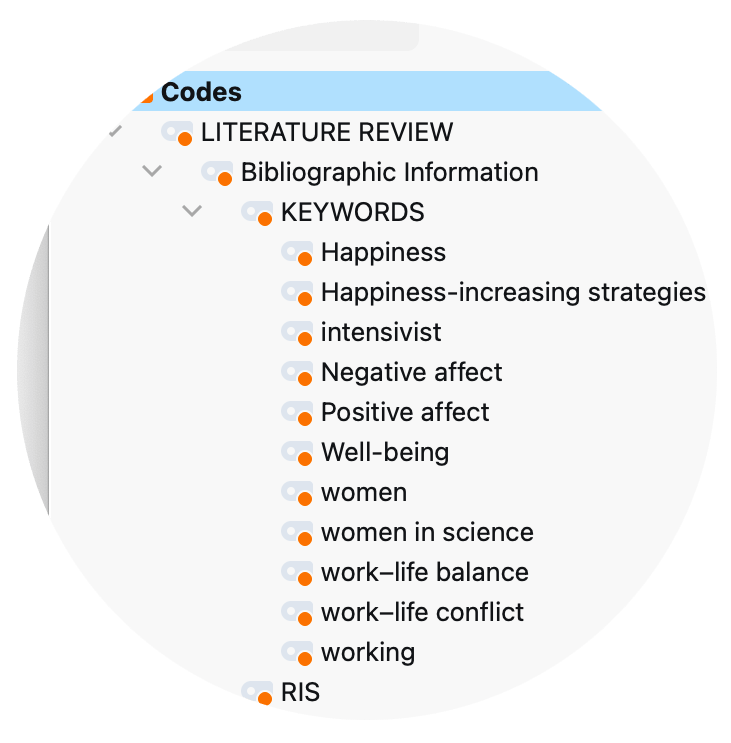

Step three: Import & Organize your material in MAXQDA

Importing bibliographic data into MAXQDA is easy and works seamlessly for all reference management programs that use the standard RIS files. MAXQDA offers an import option dedicated to bibliographic data which you can find in the MAXQDA Import tab. To import the selected literature, just click on the corresponding button, select the data you want to import, and click okay. Upon import, each literature entry becomes its own text document. If full texts are imported, MAXQDA automatically connects the full text to the literature entry with an internal link. The individual information in the literature entries is automatically coded for later analysis so that, for example, all titles or abstracts can be compiled and searched. To help you keeping your literature (review) organized, MAXQDA automatically creates a document group called “References” which contains the individual literature entries. Like full texts or interview documents, the bibliographic entries can be searched, coded, linked, edited, and you can add memos for further qualitative and quantitative content analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2019). Especially, when running multiple searches using different databases or search terms, you should carefully document your approach. Besides being a great place to store the respective search parameters, memos are perfectly suited to capture your ideas while reviewing our literature and can be attached to text segments, documents, document groups, and much more.

Analyze your literature with MAXQDA

Once imported into MAXQDA, you can explore your material using a variety of tools and functions. With MAXQDA as your literature review & analysis software, you have numerous possibilities for analyzing your literature and writing your literature review – impossible to mention all. Thus, we can present only a subset of tools here. Check out our literature about performing literature reviews with MAXQDA to discover more possibilities.

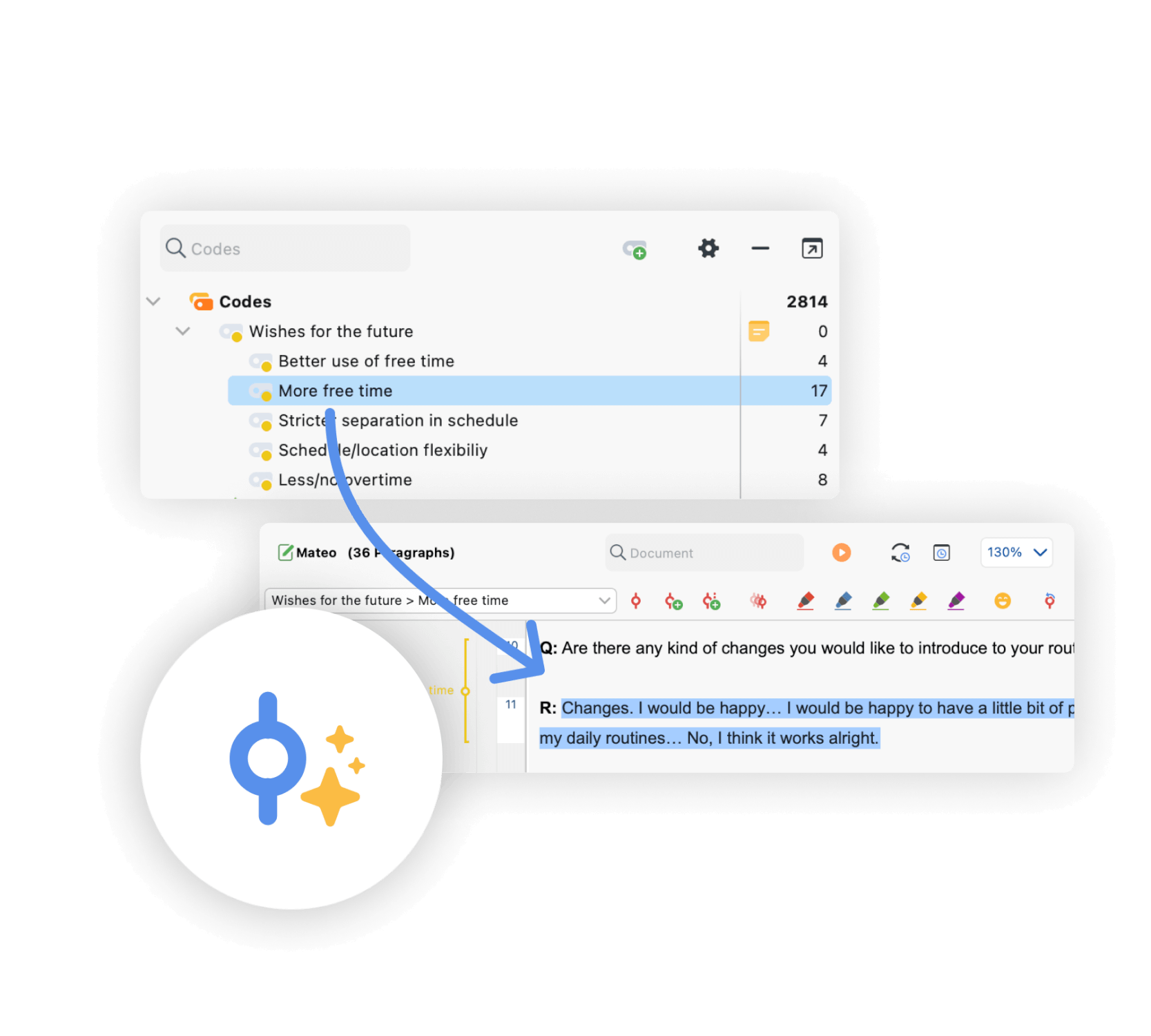

AI Assist: Introducing AI to literature reviews

AI Assist – MAXQDA’s AI-based add-on module – can simplify your literature reviews in many ways. Chat with your data and ask the AI questions about your documents. Let AI Assist automatically summarize entire papers and text segments. Automatically create summaries of all coded segments of a code or generate suggestions for subcodes, and if you don’t know a word’s or concept’s meaning, use AI Assist to get a definition without leaving MAXQDA. Visit our research guide for even more ideas on how AI can support your literature review:

AI for Literature Review

Code & Retrieve important segments

Coding qualitative data lies at the heart of many qualitative data analysis approaches and can be useful for literature reviews as well. Coding refers to the process of labeling segments of your material. For example, you may want to code definitions of certain terms, pro and con arguments, how a specific method is used, and so on. In a later step, MAXQDA allows you to compile all text segments coded with one (or more) codes of interest from one or more papers, so that you can for example compare definitions across papers.

But there is more. MAXQDA offers multiple ways of coding, such as in-vivo coding, highlighters, emoticodes, Creative Coding, or the Smart Coding Tool. The compiled segments can be enriched with variables and the segment’s context accessed with just one click. MAXQDA’s Text Search & Autocode tool is especially well-suited for a literature review, as it allows one to explore large amounts of text without reading or coding them first. Automatically search for keywords (or dictionaries of keywords), such as important concepts for your literature review, and automatically code them with just a few clicks.

Paraphrase literature into your own words

Another approach is to paraphrase the existing literature. A paraphrase is a restatement of a text or passage in your own words, while retaining the meaning and the main ideas of the original. Paraphrasing can be especially helpful in the context of literature reviews, because paraphrases force you to systematically summarize the most important statements (and only the most important statements) which can help to stay on top of things.

With MAXQDA as your literature review software, you not only have a tool for paraphrasing literature but also tools to analyze the paraphrases you have written. For example, the Categorize Paraphrases tool (allows you to code your parpahrases) or the Paraphrases Matrix (allows you to compare paraphrases side-by-side between individual documents or groups of documents.)

Summaries & Overview tables: A look at the Bigger Picture

When conducting a literature review you can easily get lost. But with MAXQDA as your literature review software, you will never lose track of the bigger picture. Among other tools, MAXQDA’s overview and summary tables are especially useful for aggregating your literature review results. MAXQDA offers overview tables for almost everything, codes, memos, coded segments, links, and so on. With MAXQDA literature review tools you can create compressed summaries of sources that can be effectively compared and represented, and with just one click you can easily export your overview and summary tables and integrate them into your literature review report.

Visualize your qualitative data

The proverb “a picture is worth a thousand words” also applies to literature reviews. That is why MAXQDA offers a variety of Visual Tools that allow you to get a quick overview of the data, and help you to identify patterns. Of course, you can export your visualizations in various formats to enrich your final report. One particularly useful visual tool for literature reviews is the Word Cloud. It visualizes the most frequent words and allows you to explore key terms and the central themes of one or more papers. Thanks to the interactive connection between your visualizations with your MAXQDA data, you will never lose sight of the big picture. Another particularly useful tool is MAXQDA’s word/code frequency tool with which you can analyze and visualize the frequencies of words or codes in one or more documents. As with Word Clouds, nonsensical words can be added to the stop list and excluded from the analysis.

QTT: Synthesize your results and write up the review

MAXQDA has an innovative workspace to gather important visualization, notes, segments, and other analytics results. The perfect tool to organize your thoughts and data. Create a separate worksheet for your topics and research questions, fill it with associated analysis elements from MAXQDA, and add your conclusions, theories, and insights as you go. For example, you can add Word Clouds, important coded segments, and your literature summaries and write down your insights. Subsequently, you can view all analysis elements and insights to write your final conclusion. The Questions-Themes-Theories tool is perfectly suited to help you finalize your literature review reports. With just one click you can export your worksheet and use it as a starting point for your literature review report.

Literature about Literature Reviews and Analysis

We offer a variety of free learning materials to help you get started with your literature review. Check out our Getting Started Guide to get a quick overview of MAXQDA and step-by-step instructions on setting up your software and creating your first project with your brand new QDA software. In addition, the free Literature Reviews Guide explains how to conduct a literature review with MAXQDA in more detail.

Getting Started with MAXQDA

Literature Reviews with MAXQDA

A literature review is a critical analysis and summary of existing research and literature on a particular topic or research question. It involves systematically searching and evaluating a range of sources, such as books, academic journals, conference proceedings, and other published or unpublished works, to identify and analyze the relevant findings, methodologies, theories, and arguments related to the research question or topic.

A literature review’s purpose is to provide a comprehensive and critical overview of the current state of knowledge and understanding of a topic, to identify gaps and inconsistencies in existing research, and to highlight areas where further research is needed. Literature reviews are commonly used in academic research, as they provide a framework for developing new research and help to situate the research within the broader context of existing knowledge.

A literature review is a critical evaluation of existing research on a particular topic and is part of almost every research project. The literature review’s purpose is to identify gaps in current knowledge, synthesize existing research findings, and provide a foundation for further research. Over the years, numerous types of literature reviews have emerged. To empower you in coming to an informed decision, we briefly present the most common literature review methods.

- Narrative Review : A narrative review summarizes and synthesizes the existing literature on a particular topic in a narrative or story-like format. This type of review is often used to provide an overview of the current state of knowledge on a topic, for example in scientific papers or final theses.

- Systematic Review : A systematic review is a comprehensive and structured approach to reviewing the literature on a particular topic with the aim of answering a defined research question. It involves a systematic search of the literature using pre-specified eligibility criteria and a structured evaluation of the quality of the research.

- Meta-Analysis : A meta-analysis is a type of systematic review that uses statistical techniques to combine and analyze the results from multiple studies on the same topic. The goal of a meta-analysis is to provide a more robust and reliable estimate of the effect size than can be obtained from any single study.

- Scoping Review : A scoping review is a type of systematic review that aims to map the existing literature on a particular topic in order to identify the scope and nature of the research that has been done. It is often used to identify gaps in the literature and inform future research.

There is no “best” way to do a literature review, as the process can vary depending on the research question, field of study, and personal preferences. However, here are some general guidelines that can help to ensure that your literature review is comprehensive and effective:

- Carefully plan your literature review : Before you start searching and analyzing literature you should define a research question and develop a search strategy (for example identify relevant databases, and search terms). A clearly defined research question and search strategy will help you to focus your search and ensure that you are gathering relevant information. MAXQDA’s Questions-Themes-Theories tool is the perfect place to store your analysis plan.

- Evaluate your sources : Screen your search results for relevance to your research question, for example by reading abstracts. Once you have identified relevant sources, read them critically and evaluate their quality and relevance to your research question. Consider factors such as the methodology used, the reliability of the data, and the overall strength of the argument presented.

- Synthesize your findings : After evaluating your sources, synthesize your findings by identifying common themes, arguments, and gaps in the existing research. This will help you to develop a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge on your topic.

- Write up your review : Finally, write up your literature review, ensuring that it is well-structured and clearly communicates your findings. Include a critical analysis of the sources you have reviewed, and use evidence from the literature to support your arguments and conclusions.

Overall, the key to a successful literature review is to be systematic, critical, and comprehensive in your search and evaluation of sources.

As in all aspects of scientific work, preparation is the key to success. Carefully think about the purpose of your literature review, the questions you want to answer, and your search strategy. The writing process itself will differ depending on the your literature review method. For example, when writing a narrative review use the identified literature to support your arguments, approach, and conclusions. By contrast, a systematic review typically contains the same parts as other scientific papers: Abstract, Introduction (purpose and scope), Methods (Search strategy, inclusion/exclusion characteristics, …), Results (identified sources, their main arguments, findings, …), Discussion (critical analysis of the sources you have reviewed), Conclusion (gaps or inconsistencies in the existing research, future research, implications, etc.).

Start your free trial

Your trial will end automatically after 14 days and will not renew. There is no need for cancelation.

7 open source tools to make literature reviews easy

Opensource.com

A good literature review is critical for academic research in any field, whether it is for a research article, a critical review for coursework, or a dissertation. In a recent article, I presented detailed steps for doing a literature review using open source software .

The following is a brief summary of seven free and open source software tools described in that article that will make your next literature review much easier.

1. GNU Linux

Most literature reviews are accomplished by graduate students working in research labs in universities. For absurd reasons, graduate students often have the worst computers on campus. They are often old, slow, and clunky Windows machines that have been discarded and recycled from the undergraduate computer labs. Installing a flavor of GNU Linux will breathe new life into these outdated PCs. There are more than 100 distributions , all of which can be downloaded and installed for free on computers. Most popular Linux distributions come with a "try-before-you-buy" feature. For example, with Ubuntu you can make a bootable USB stick that allows you to test-run the Ubuntu desktop experience without interfering in any way with your PC configuration. If you like the experience, you can use the stick to install Ubuntu on your machine permanently.

Linux distributions generally come with a free web browser, and the most popular is Firefox . Two Firefox plugins that are particularly useful for literature reviews are Unpaywall and Zotero. Keep reading to learn why.

3. Unpaywall

Often one of the hardest parts of a literature review is gaining access to the papers you want to read for your review. The unintended consequence of copyright restrictions and paywalls is it has narrowed access to the peer-reviewed literature to the point that even Harvard University is challenged to pay for it. Fortunately, there are a lot of open access articles—about a third of the literature is free (and the percentage is growing). Unpaywall is a Firefox plugin that enables researchers to click a green tab on the side of the browser and skip the paywall on millions of peer-reviewed journal articles. This makes finding accessible copies of articles much faster that searching each database individually. Unpaywall is fast, free, and legal, as it accesses many of the open access sites that I covered in my paper on using open source in lit reviews .

Formatting references is the most tedious of academic tasks. Zotero can save you from ever doing it again. It operates as an Android app, desktop program, and a Firefox plugin (which I recommend). It is a free, easy-to-use tool to help you collect, organize, cite, and share research. It replaces the functionality of proprietary packages such as RefWorks, Endnote, and Papers for zero cost. Zotero can auto-add bibliographic information directly from websites. In addition, it can scrape bibliographic data from PDF files. Notes can be easily added on each reference. Finally, and most importantly, it can import and export the bibliography databases in all publishers' various formats. With this feature, you can export bibliographic information to paste into a document editor for a paper or thesis—or even to a wiki for dynamic collaborative literature reviews (see tool #7 for more on the value of wikis in lit reviews).

5. LibreOffice

Your thesis or academic article can be written conventionally with the free office suite LibreOffice , which operates similarly to Microsoft's Office products but respects your freedom. Zotero has a word processor plugin to integrate directly with LibreOffice. LibreOffice is more than adequate for the vast majority of academic paper writing.

If LibreOffice is not enough for your layout needs, you can take your paper writing one step further with LaTeX , a high-quality typesetting system specifically designed for producing technical and scientific documentation. LaTeX is particularly useful if your writing has a lot of equations in it. Also, Zotero libraries can be directly exported to BibTeX files for use with LaTeX.

7. MediaWiki

If you want to leverage the open source way to get help with your literature review, you can facilitate a dynamic collaborative literature review . A wiki is a website that allows anyone to add, delete, or revise content directly using a web browser. MediaWiki is free software that enables you to set up your own wikis.

Researchers can (in decreasing order of complexity): 1) set up their own research group wiki with MediaWiki, 2) utilize wikis already established at their universities (e.g., Aalto University ), or 3) use wikis dedicated to areas that they research. For example, several university research groups that focus on sustainability (including mine ) use Appropedia , which is set up for collaborative solutions on sustainability, appropriate technology, poverty reduction, and permaculture.

Using a wiki makes it easy for anyone in the group to keep track of the status of and update literature reviews (both current and older or from other researchers). It also enables multiple members of the group to easily collaborate on a literature review asynchronously. Most importantly, it enables people outside the research group to help make a literature review more complete, accurate, and up-to-date.

Wrapping up

Free and open source software can cover the entire lit review toolchain, meaning there's no need for anyone to use proprietary solutions. Do you use other libre tools for making literature reviews or other academic work easier? Please let us know your favorites in the comments.

Related Content

We generate robust evidence fast

What is silvi.ai .

Silvi is an end-to-end screening and data extraction tool supporting Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis.

Silvi helps create systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses that follow Cochrane guidelines in a highly reduced time frame, giving a fast and easy overview. It supports the user through the full process, from literature search to data analyses. Silvi is directly connected with databases such as PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov and is always updated with the latest published research. It also supports RIS files, making it possible to upload a search string from your favorite search engine (i.e., Ovid). Silvi has a tagging system that can be tailored to any project.

Silvi is transparent, meaning it documents and stores the choices (and the reasons behind them) the user makes. Whether publishing the results from the project in a journal, sending them to an authority, or collaborating on the project with several colleagues, transparency is optimal to create robust evidence.

Silvi is developed with the user experience in mind. The design is intuitive and easily available to new users. There is no need to become a super-user. However, if any questions should arise anyway, we have a series of super short, instructional videos to get back on track.

To see Silvi in use, watch our short introduction video.

Short introduction video

Learn more about Silvi’s specifications here.

"I like that I can highlight key inclusions and exclusions which makes the screening process really quick - I went through 2000+ titles and abstracts in just a few hours"

Eishaan Kamta Bhargava

Consultant Paediatric ENT Surgeon, Sheffield Children's Hospital

"I really like how intuitive it is working with Silvi. I instantly felt like a superuser."

Henriette Kristensen

Senior Director, Ferring Pharmaceuticals

"The idea behind Silvi is great. Normally, I really dislike doing literature reviews, as they take up huge amounts of time. Silvi has made it so much easier! Thanks."

Claus Rehfeld

Senior Consultant, Nordic Healthcare Group

"AI has emerged as an indispensable tool for compiling evidence and conducting meta-analyses. Silvi.ai has proven to be the most comprehensive option I have explored, seamlessly integrating automated processes with the indispensable attributes of clarity and reproducibility essential for rigorous research practices."

Martin Södermark

M.Sc. Specialist in clinical adult psychology

Silvi.ai was founded in 2018 by Professor in Health Economic Evidence, Tove Holm-Larsen, and expert in Machine Learning, Rasmus Hvingelby. The idea for Silvi stemmed from their own research, and the need to conduct systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses faster.

The ideas behind Silvi were originally a component of a larger project. In 2016, Tove founded the group “Evidensbaseret Medicin 2.0” in collaboration with researchers from Ghent University, Technical University of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, and other experts. EBM 2.0 wanted to optimize evidence-based medicine to its highest potential using Big Data and Artificial Intelligence, but needed a highly skilled person within AI.

Around this time, Tove met Rasmus, who shared the same visions. Tove teamed up with Rasmus, and Silvi.ai was created.

Our story

.png)

Free Trial

No card de t ails nee ded!

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Literature review tool

The following tool will help you learn how to conduct a solid review of literature. To do so, you will have to answer the questions posed in the form you will find on the lower left side, while checking the resources provided on the right side.

Positionality is the notion that identity , paradigmatic views , and location in time and space influence how one understands the world. Consequently, it is essential to take into account positionality before engaging in research, including research synthesis. Learn more about identity, approaches or paradigmatic views such as positivism, interpretivism, constructivism, and others here

The second step in the generation of the literature review design is setting purposes and objectives that will drive the review process. Your searching strategies, the literature analysis, and even a review structure depend on the purposes of a review, the same way as the goals and research questions in a research study shape its design. Learn more about the purposes and objectives of a traditional literature "nested" in a research study and a research synthesis.

There are key things to think about before you start searching for literature or conduct research synthesis. You should define and narrow your topic. Since each disciplinary domain has its own thesaurus, index, and databases, contemplate in which disciplines or areas of study your research synthesis will be conducted. Formulate the initial research question that you will develop further during the search for the literature and the design step. Learn more here.

The conceptual & theoretical framework of your study is the system of concepts, assumptions, expectations, beliefs, and theories that supports and informs your research. It is a formulation of what you think is going on with what you are studying—a tentative theory of what is happening and why. Read more about "concepts" and how to search for and clarify them, how to find a relevant theory, here .

Secondary data analysis and review of literature involve collecting and analyzing a vast array of information and sources. To help you stay focused, your first step should be to develop a research design or a step-by-step plan or a protocol that guides data collection and analysis. Get familiar with different types if the research designs on this page .

As with any research study, the basic purpose of data collection is to create a systematically organized set of materials that will be analyzed or interpreted. Any type of reviews, not only a systematic review, benefit from applying relatively systematic methods of searching and collecting secondary data. In this part of the guide , I describe sampling methods, instruments (or searching techniques), and organization of sources.

The seventh step regards the selection and definition of the data analysis strategies that will be used in your study, depending on the research approach followed. You can find here resources that might be of help to better understand the way data analysis work.

After analyzing studies or literature in a depth and the systematic way one should move to the iterative process of exploring, commonalities and contradictions across relevant studies, emergent themes in order to build a theory, frame future research, or creating a final integrated presentation of finding. Find out more here.

Ethical considerations of conducting literature reviews and the issues of quality are not widely discussed in the literature. Consult t his guide where you will find references to work on ethics of conducting systematic reviews, checklists for quality of meta-analysis and research synthesis.

The following AI tools can assist you in step 9 of the process of generating your design:

Google Bard can be used to identify potential ethical principles a researcher could define to ethically conduct a given study.

For instance, we could use the following prompt: What principles could a researcher define to ethically conduct a qualitative case study regarding the long-term impact of competency-based assessment on secondary education students in a secondary school in Marietta (Georgia)?

The following AI tools can assist you in step 8 of the process of generating your design:

Google Bard can be used to identify potential strategies we could implement as researchers to ensure the trustworthiness/validity of a given study.

For instance, we could use the following prompt: What strategies could a researcher use to ensure the trustworthiness qualitative case study regarding the long-term impact of competency-based assessment on secondary education students in a secondary school in Marietta (Georgia).

The following AI tools can assist you in step 7 of the process of generating your design:

AI data analysis is on the rise. For instance, the AI module of Atlas.ti can be used to analyze qualitative data.

The following AI tools can assist you in step 5 of the process of generating your design:

Consensus could be used to identify research questions that have been used in previously published studies. Consensus is an AI-powered search engine designed to take in research questions, find relevant insights within research papers, and synthesize the results using large language models. It is not a chatbot. Consensus only searches through peer-reviewed scientific research articles to find the most credible insights to your queries.

AI: Google Bard could be used to identify potential questions for a particular research tradition or design.

For instance, we could use the following prompt: Generate examples of research questions that could be used to drive a qualitative case study regarding the long-term impact of competency-based assessment on secondary education students in a secondary school in Marietta (Georgia).

The following AI tools can assist you in step 4 of the process of generating your design:

Google Bard could be used to help users of Hopscotch understand the differences between research traditions for a certain topic.

For instance, we could use the following prompt: Generate a brief description of the key elements of a qualitative case study research design regarding the long-term impact of competency-based assessment on secondary education students in a secondary school in Marietta (Georgia). To do this, use the following nine steps proposed by the Hopscotch Model:

Step 1: Paradigmatic View of the Researcher

Step 2: Topics & Goals of the Study

Step 3: Conceptual framework of the study

Step 4: Research Design/tradition

Step 5: Research Questions

Step 6: Data Gathering Methods

Step 7: Data Analysis

Step 8: Trustworthiness/Validity

Step 9: Ethics driving the study

The following AI tools can assist you in step 3 of the process of generating your design:

AI: ResearchRabbit is a scholarly publication discovery tool supported by artificial intelligence (AI). The tool is designed to support your research without you switching between searching modes and databases, a process that is time-consuming and often escalates into further citation mining; a truly unpleasant rabbit hole (and that’s what inspired the name ResearchRabbit)

AI: 2Dsearch is a radical alternative to conventional ‘advanced search’. Instead of entering Boolean strings into one-dimensional search boxes, queries are formulated by manipulating objects on a two-dimensional canvas. This eliminates syntax errors, makes the query semantics more transparent, and offers new ways to collaborate, share, and optimize search strategies and best practices.

Welcome to ResearchRabbit from ResearchRabbit on Vimeo .

The following AI tools can assist you in step 2 of the process of generating your design:

AI: Consensus could be used to assist users in the identification of relevant topics that have been published in peer-reviewed articles. Consensus is an AI-powered search engine designed to take in research questions, find relevant insights within research papers, and synthesize the results using large language models. It is not a chatbot. Consensus only searches through peer-reviewed scientific research articles to find the most credible insights to your queries.

AI: Carrot2 could be used to identify potential research topics. Carrot2 organizes your search results into topics. With an instant overview of what’s available, you will quickly find what you’re looking for.

The following AI tools can assist you in step 1 of the process of generating your design:

You could use Google Bard , Perplexity , or ChatGPT , to ask for the differences between the key wordlviews that a researcher can bring to a given study.

For instance, we could use the following prompt: What are the defining characteristics of the main worldviews or paradigmatic positioning (positivistic worldviews, post-positivistic worldview; constructivistic worldview; transformative worldview, and; pragmatic worldview) a researcher can bring to a given study?

The following AI tools can assist you in step 6 of the process of generating your design:

We could use Google Bard to develop a draft of a data collection protocol for a given study.

For instance, we could use the following prompt: Generate an interview protocol for students involved in a qualitative case study regarding the long-term impact of competency-based assessment on secondary education students in a secondary school in Marietta (Georgia).

You can use the following AI tools to assist you in the process of generating your design:

Step 1: Paradigmatic View of the Researcher

AI: You could use Google Bard , Perplexity , or ChatGPT , to ask for the differences between the key wordlviews that a researcher can bring to a given study.

Step 2: Topics & Goals of the Study

AI: Google Bard could be used to help users of Hopscotch understand the differences between research traditions for a certain topic.