Example sentences clinical presentation

Definition of 'clinical' clinical.

Definition of 'present' present

Cobuild collocations clinical presentation.

Browse alphabetically clinical presentation

- clinical pharmacology

- clinical phenotype

- clinical practice

- clinical presentation

- clinical professional

- clinical psychologist

- clinical psychology

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'C'

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

Clinical Presentation

Clinical considerations for care of children and adults with confirmed COVID-19

‹ View Table of Contents

- The clinical presentation of COVID-19 ranges from asymptomatic to critical illness.

- An infected person can transmit SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, before the onset of symptoms. Symptoms can change over the course of illness and can progress in severity.

- Uncommon presentations of COVID-19 can occur, might vary by the age of the patient, and are a challenge to recognize.

- In adults, age is the strongest risk factor for severe COVID-19. The risk of severe COVID-19 increases with increasing age especially for persons over 65 years and with increasing number of certain underlying medical conditions .

Incubation Period

Data suggest that incubation periods may differ by SARS-CoV-2 variant. Meta-analyses of studies published in 2020 identified a pooled mean incubation period of 6.5 days from exposure to symptom onset. (1) A study conducted during high levels of Delta variant transmission reported an incubation period of 4.3 days, (2) and studies performed during high levels of Omicron variant transmission reported a median incubation period of 3–4 days. (3,4)

Presentation

People with COVID-19 may be asymptomatic or may commonly experience one or more of the following symptoms (not a comprehensive list) (5) :

- Fever or chills

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Myalgia (Muscle or body aches)

- New loss of taste or smell

- Sore throat

- Congestion or runny nose

- Nausea or vomiting

The clinical presentation of COVID-19 ranges from asymptomatic to severe illness, and COVID-19 symptoms may change over the course of illness. COVID-19 symptoms can be difficult to differentiate from and can overlap with other viral respiratory illnesses such as influenza(flu) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) . Because symptoms may progress quickly, close follow-up is needed, especially for:

- older adults

- people with disabilities

- people with immunocompromising conditions, and

- people with medical conditions that place them at greater risk for severe illness or death.

The NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines group SARS-CoV-2 infection into five categories based on severity of illness:

- Asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic infection : people who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 using a virologic test (i.e., a nucleic acid amplification test [NAAT] or an antigen test) but who have no symptoms that are consistent with COVID-19.

- Mild illness : people who may have any of the various signs and symptoms of COVID-19 but who do not have shortness of breath, dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging.

- Moderate illness : people who have evidence of lower respiratory disease during clinical assessment or imaging and who have an oxygen saturation (SpO 2 ) ≥94% on room air at sea level.

- Severe illness : people who have oxygen saturation <94% on room air at sea level, a ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO 2 /FiO 2 ) <300 mm Hg, a respiratory rate >30 breaths/min, or lung infiltrates >50%

- Critical illness : people who have respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiple organ dysfunction.

Asymptomatic and presymptomatic presentation

Studies have documented SARS-CoV-2 infection in people who never develop symptoms (asymptomatic presentation) and in people who are asymptomatic when tested but develop symptoms later (presymptomatic presentation). ( 6,7 ) It is unclear what percentage of people who initially appear asymptomatic progress to clinical disease. Multiple publications have reported cases of people with abnormalities on chest imaging that are consistent with COVID-19 very early in the course of illness, even before the onset of symptoms or a positive COVID-19 test. (9)

Radiographic Considerations and Findings

Chest radiographs of patients with severe COVID-19 may demonstrate bilateral air-space consolidation. (23) Chest computed tomography (CT) images from patients with COVID-19 may demonstrate bilateral, peripheral ground glass opacities and consolidation. (24,25) Less common CT findings can include intra- or interlobular septal thickening with ground glass opacities (hazy opacity) or focal and rounded areas of ground glass opacity surrounded by a ring or arc of denser consolidation (reverse halo sign). (24)

Multiple studies suggest that abnormalities on CT or chest radiograph may be present in people who are asymptomatic, pre-symptomatic, or before RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in nasopharyngeal specimens. (25)

Common COVID-19 symptoms

Fever, cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, headache, and myalgia are among the most commonly reported symptoms in people with COVID-19. (5) Some people with COVID-19 have gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, sometimes prior to having fever or lower respiratory tract signs and symptoms. (10) Loss of smell and taste can occur, although these symptoms are reported to be less common since Omicron began circulating, as compared to earlier during the COVID-19 pandemic. (11,19-21) People can experience SARS-CoV-2 infection (asymptomatic or symptomatic), even if they are up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines or were previously infected. (8)

Several studies have reported ocular symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, including redness, tearing, dry eye or foreign body sensation, discharge or increased secretions, and eye itching or pain. (13)

A wide range of dermatologic manifestations have been associated with COVID-19; timing of skin manifestations in relation to other COVID-19 symptoms and signs is variable. (14) Some skin manifestations may be associated with increased disease severity. (15) Images of cutaneous findings in COVID-19 are available from the American Academy of Dermatology .

Uncommon COVID-19 symptoms

Less common presentations of COVID-19 can occur. Older adults may present with different symptoms than children and younger adults. Some older adults can experience SARS-CoV-2 infection accompanied by delirium, falls, reduced mobility or generalized weakness, and glycemic changes. ( 12)

Transmission

People infected with SARS-CoV-2 can transmit the virus even if they are asymptomatic or presymptomatic. ( 16) Peak transmissibility appears to occur early during the infectious period (prior to symptom onset until a few days after), but infected persons can shed infectious virus up to 10 days following infection. (22 ) Both vaccinated and unvaccinated people can transmit SARS-CoV-2. ( 17,18) Clinicians should consider encouraging all people to take the following prevention actions to limit SARS-CoV-2 transmission:

- stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccines,

- test for COVID-19 when symptomatic or exposed to someone with COVID-19, as recommended by CDC,

- wear a high-quality mask when recommended,

- avoiding contact with individuals who have suspected or confirmed COVID-19,

- improving ventilation when possible,

- and follow basic health and hand hygiene guidance .

Clinicians should also recommend that people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2, follow CDC guidelines for isolation.

Table of Contents

- › Clinical Presentation

- Clinical Progression, Management, and Treatment

- Special Clinical Considerations

- Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Evans SJ, et al. Factors associated with deaths due to COVID-19 versus other causes: population-based cohort analysis of UK primary care data and linked national death registrations within the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet Reg Health Eur. Jul 2021;6:100109. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100109

- Kim L, Garg S, O'Halloran A, et al. Risk Factors for Intensive Care Unit Admission and In-hospital Mortality among Hospitalized Adults Identified through the U.S. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET). Clin Infect Dis. Jul 16 2020;doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1012

- Kompaniyets L, Pennington AF, Goodman AB, et al. Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020-March 2021. Preventing chronic disease. Jul 1 2021;18:E66. doi:10.5888/pcd18.210123

- Ko JY, Danielson ML, Town M, et al. Risk Factors for COVID-19-associated hospitalization: COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Clin Infect Dis. Sep 18 2020;doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1419

- Wortham JM, Lee JT, Althomsons S, et al. Characteristics of Persons Who Died with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-May 18, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jul 17 2020;69(28):923-929. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6928e1

- Yang X, Zhang J, Chen S, et al. Demographic Disparities in Clinical Outcomes of COVID-19: Data From a Statewide Cohort in South Carolina. Open Forum Infect Dis. Sep 2021;8(9):ofab428. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab428

- Rader B.; Gertz AL, D.; Gilmer, M.; Wronski, L.; Astley, C.; Sewalk, K.; Varrelman, T.; Cohen, J.; Parikh, R.; Reese, H.; Reed, C.; Brownstein J. Use of At-Home COVID-19 Tests — United States, August 23, 2021–March 12, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. April 1, 2022;71(13):489–494. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7113e1

- Pingali C, Meghani M, Razzaghi H, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Among Insured Persons Aged >/=16 Years, by Race/Ethnicity and Other Selected Characteristics - Eight Integrated Health Care Organizations, United States, December 14, 2020-May 15, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jul 16 2021;70(28):985-990. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7028a1

- Wiltz JL, Feehan AK, Molinari NM, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Receipt of Medications for Treatment of COVID-19 - United States, March 2020-August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jan 21 2022;71(3):96-102. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7103e1

- Murthy NC, Zell E, Fast HE, et al. Disparities in First Dose COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage among Children 5-11 Years of Age, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. May 2022;28(5):986-989. doi:10.3201/eid2805.220166

- Saelee R, Zell E, Murthy BP, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Between Urban and Rural Counties - United States, December 14, 2020-January 31, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Mar 4 2022;71(9):335-340. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7109a2

- Burki TK. The role of antiviral treatment in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. Feb 2022;10(2):e18. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00011-X

- Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, et al. Molnupiravir for Oral Treatment of Covid-19 in Nonhospitalized Patients. N Engl J Med. Feb 10 2022;386(6):509-520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2116044

- Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, Gay SE, Valley TS. Racial Bias in Pulse Oximetry Measurement. N Engl J Med. Dec 17 2020;383(25):2477-2478. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2029240

- Jordan TB, Meyers CL, Schrading WA, Donnelly JP. The utility of iPhone oximetry apps: A comparison with standard pulse oximetry measurement in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. May 2020;38(5):925-928. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.07.020

- Iuliano AD, Brunkard JM, Boehmer TK, et al. Trends in Disease Severity and Health Care Utilization During the Early Omicron Variant Period Compared with Previous SARS-CoV-2 High Transmission Periods - United States, December 2020-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jan 28 2022;71(4):146-152. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e4

- Taylor CA, Whitaker M, Anglin O, et al. COVID-19-Associated Hospitalizations Among Adults During SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron Variant Predominance, by Race/Ethnicity and Vaccination Status - COVID-NET, 14 States, July 2021-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Mar 25 2022;71(12):466-473. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7112e2

- Johnson AG, Amin AB, Ali AR, et al. COVID-19 Incidence and Death Rates Among Unvaccinated and Fully Vaccinated Adults with and Without Booster Doses During Periods of Delta and Omicron Variant Emergence - 25 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4-December 25, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jan 28 2022;71(4):132-138. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e2

- Danza P, Koo TH, Haddix M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Hospitalization Among Adults Aged >/=18 Years, by Vaccination Status, Before and During SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant Predominance - Los Angeles County, California, November 7, 2021-January 8, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Feb 4 2022;71(5):177-181. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7105e1

To receive email updates about COVID-19, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Overview and General Information about Oral Presentation

- Daily Presentations During Work Rounds

- The New Patient Presentation

- The Holdover Admission Presentation

- Outpatient Clinic Presentations

- The structure of presentations varies from service to service (e.g. medicine vs. surgery), amongst subspecialties, and between environments (inpatient vs. outpatient). Applying the correct style to the right setting requires that the presenter seek guidance from the listeners at the outset.

- Time available for presenting is rather short, which makes the experience more stressful.

- Individual supervisors (residents, faculty) often have their own (sometimes quirky) preferences regarding presentation styles, adding another layer of variability that the presenter has to manage.

- Students are evaluated/judged on the way in which they present, with faculty using this as one way of gauging a student’s clinical knowledge.

- Done well, presentations promote efficient, excellent care. Done poorly, they promote tedium, low morale, and inefficiency.

General Tips:

- Practice, Practice, Practice! Do this on your own, with colleagues, and/or with anyone who will listen (and offer helpful commentary) before you actually present in front of other clinicians. Speaking "on-the-fly" is difficult, as rapidly organizing and delivering information in a clear and concise fashion is not a naturally occurring skill.

- Immediately following your presentations, seek feedback from your listeners. Ask for specifics about what was done well and what could have been done better – always with an eye towards gaining information that you can apply to improve your performance the next time.

- Listen to presentations that are done well – ask yourself, “Why was it good?” Then try to incorporate those elements into your own presentations.

- Listen to presentations that go poorly – identify the specific things that made it ineffective and avoid those pitfalls when you present.

- Effective presentations require that you have thought through the case beforehand and understand the rationale for your conclusions and plan. This, in turn, requires that you have a good grasp of physiology, pathology, clinical reasoning and decision-making - pushing you to read, pay attention, and in general acquire more knowledge.

- Think about the clinical situation in which you are presenting so that you can provide a summary that is consistent with the expectations of your audience. Work rounds, for example, are clearly different from conferences and therefore mandate a different style of presentation.

- Presentations are the way in which we tell medical stories to one another. When you present, ask yourself if you’ve described the story in an accurate way. Will the listener be able to “see” the patient the same way that you do? Can they come to the correct conclusions? If not, re-calibrate.

- It's O.K. to use notes, though the oral presentation should not simply be reduced to reading the admission note – rather, it requires appropriate editing/shortening.

- In general, try to give your presentations on a particular service using the same order and style for each patient, every day. Following a specific format makes it easier for the listener to follow, as they know what’s coming and when they can expect to hear particular information. Additionally, following a standardized approach makes it easier for you to stay organized, develop a rhythm, and lessens the chance that you’ll omit elements.

Specific types of presentations

There are a number of common presentation-types, each with its own goals and formats. These include:

- Daily presentations during work rounds for patients known to a service.

- Newly admitted patients, where you were the clinician that performed the H&P.

- Newly admitted patients that were “handed off” to the team in the morning, such that the H&P was performed by others.

- Outpatient clinic presentations, covering several common situations.

Key elements of each presentation type are described below. Examples of how these would be applied to most situations are provided in italics. The formats are typical of presentations done for internal medicine services and clinics.

Note that there is an acceptable range of how oral presentations can be delivered. Ultimately, your goal is to tell the correct story, in a reasonable amount of time, so that the right care can be delivered. Nuances in the order of presentation, what to include, what to omit, etc. are relatively small points. Don’t let the pursuit of these elements distract you or create undue anxiety.

Daily presentations during work rounds of patients that you’re following:

- Organize the presenter (forces you to think things through)

- Inform the listener(s) of 24 hour events and plan moving forward

- Promote focused discussion amongst your listeners and supervisors

- Opportunity to reassess plan, adjust as indicated

- Demonstrate your knowledge and engagement in the care of the patient

- Rapid (5 min) presentation of the key facts

Key features of presentation:

- Opening one liner: Describe who the patient is, number of days in hospital, and their main clinical issue(s).

- 24-hour events: Highlighting changes in clinical status, procedures, consults, etc.

- Subjective sense from the patient about how they’re feeling, vital signs (ranges), and key physical exam findings (highlighting changes)

- Relevant labs (highlighting changes) and imaging

- Assessment and Plan : Presented by problem or organ systems(s), using as many or few as are relevant. Early on, it’s helpful to go through the main categories in your head as a way of making sure that you’re not missing any relevant areas. The broad organ system categories include (presented here head-to-toe): Neurological; Psychiatric; Cardiovascular; Pulmonary; Gastrointestinal; Renal/Genitourinary; Hematologic/Oncologic; Endocrine/Metabolic; Infectious; Tubes/lines/drains; Disposition.

Example of a daily presentation for a patient known to a team:

- Opening one liner: This is Mr. Smith, a 65 year old man, Hospital Day #3, being treated for right leg cellulitis

- MRI of the leg, negative for osteomyelitis

- Evaluation by Orthopedics, who I&D’d a superficial abscess in the calf, draining a moderate amount of pus

- Patient appears well, states leg is feeling better, less painful

- T Max 101 yesterday, T Current 98; Pulse range 60-80; BP 140s-160s/70-80s; O2 sat 98% Room Air

- Ins/Outs: 3L in (2 L NS, 1 L po)/Out 4L urine

- Right lower extremity redness now limited to calf, well within inked lines – improved compared with yesterday; bandage removed from the I&D site, and base had small amount of purulence; No evidence of fluctuance or undrained infection.

- Creatinine .8, down from 1.5 yesterday

- WBC 8.7, down from 14

- Blood cultures from admission still negative

- Gram stain of pus from yesterday’s I&D: + PMNS and GPCs; Culture pending

- MRI lower extremity as noted above – negative for osteomyelitis

- Continue Vancomycin for today

- Ortho to reassess I&D site, though looks good

- Follow-up on cultures: if MRSA, will transition to PO Doxycycline; if MSSA, will use PO Dicloxacillin

- Given AKI, will continue to hold ace-inhibitor; will likely wait until outpatient follow-up to restart

- Add back amlodipine 5mg/d today

- Hep lock IV as no need for more IVF

- Continue to hold ace-I as above

- Wound care teaching with RNs today – wife capable and willing to assist. She’ll be in this afternoon.

- Set up follow-up with PMD to reassess wound and cellulitis within 1 week

The Brand New Patient (admitted by you)

- Provide enough information so that the listeners can understand the presentation and generate an appropriate differential diagnosis.

- Present a thoughtful assessment

- Present diagnostic and therapeutic plans

- Provide opportunities for senior listeners to intervene and offer input

- Chief concern: Reason why patient presented to hospital (symptom/event and key past history in one sentence). It often includes a limited listing of their other medical conditions (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, etc.) if these elements might contribute to the reason for admission.

- The history is presented highlighting the relevant events in chronological order.

- 7 days ago, the patient began to notice vague shortness of breath.

- 5 days ago, the breathlessness worsened and they developed a cough productive of green sputum.

- 3 days ago his short of breath worsened to the point where he was winded after walking up a flight of stairs, accompanied by a vague right sided chest pain that was more pronounced with inspiration.

- Enough historical information has to be provided so that the listener can understand the reasons that lead to admission and be able to draw appropriate clinical conclusions.

- Past history that helps to shed light on the current presentation are included towards the end of the HPI and not presented later as “PMH.” This is because knowing this “past” history is actually critical to understanding the current complaint. For example, past cardiac catheterization findings and/or interventions should be presented during the HPI for a patient presenting with chest pain.

- Where relevant, the patient's baseline functional status is described, allowing the listener to understand the degree of impairment caused by the acute medical problem(s).

- It should be explicitly stated if a patient is a poor historian, confused or simply unaware of all the details related to their illness. Historical information obtained from family, friends, etc. should be described as such.

- Review of Systems (ROS): Pertinent positive and negative findings discovered during a review of systems are generally incorporated at the end of the HPI. The listener needs this information to help them put the story in appropriate perspective. Any positive responses to a more inclusive ROS that covers all of the other various organ systems are then noted. If the ROS is completely negative, it is generally acceptable to simply state, "ROS negative.”

- Other Past Medical and Surgical History (PMH/PSH): Past history that relates to the issues that lead to admission are typically mentioned in the HPI and do not have to be repeated here. That said, selective redundancy (i.e. if it’s really important) is OK. Other PMH/PSH are presented here if relevant to the current issues and/or likely to affect the patient’s hospitalization in some way. Unrelated PMH and PSH can be omitted (e.g. if the patient had their gall bladder removed 10y ago and this has no bearing on the admission, then it would be appropriate to leave it out). If the listener really wants to know peripheral details, they can read the admission note, ask the patient themselves, or inquire at the end of the presentation.

- Medications and Allergies: Typically all meds are described, as there’s high potential for adverse reactions or drug-drug interactions.

- Family History: Emphasis is placed on the identification of illnesses within the family (particularly among first degree relatives) that are known to be genetically based and therefore potentially heritable by the patient. This would include: coronary artery disease, diabetes, certain cancers and autoimmune disorders, etc. If the family history is non-contributory, it’s fine to say so.

- Social History, Habits, other → as relates to/informs the presentation or hospitalization. Includes education, work, exposures, hobbies, smoking, alcohol or other substance use/abuse.

- Sexual history if it relates to the active problems.

- Vital signs and relevant findings (or their absence) are provided. As your team develops trust in your ability to identify and report on key problems, it may become acceptable to say “Vital signs stable.”

- Note: Some listeners expect students (and other junior clinicians) to describe what they find in every organ system and will not allow the presenter to say “normal.” The only way to know what to include or omit is to ask beforehand.

- Key labs and imaging: Abnormal findings are highlighted as well as changes from baseline.

- Summary, assessment & plan(s) Presented by problem or organ systems(s), using as many or few as are relevant. Early on, it’s helpful to go through the main categories in your head as a way of making sure that you’re not missing any relevant areas. The broad organ system categories include (presented here head-to-toe): Neurological; Psychiatric; Cardiovascular; Pulmonary; Gastrointestinal; Renal/Genitourinary; Hematologic/Oncologic; Endocrine/Metabolic; Infectious; Tubes/lines/drains; Disposition.

- The assessment and plan typically concludes by mentioning appropriate prophylactic considerations (e.g. DVT prevention), code status and disposition.

- Chief Concern: Mr. H is a 50 year old male with AIDS, on HAART, with preserved CD4 count and undetectable viral load, who presents for the evaluation of fever, chills and a cough over the past 7 days.

- Until 1 week ago, he had been quite active, walking up to 2 miles a day without feeling short of breath.

- Approximately 1 week ago, he began to feel dyspneic with moderate activity.

- 3 days ago, he began to develop subjective fevers and chills along with a cough productive of red-green sputum.

- 1 day ago, he was breathless after walking up a single flight of stairs and spent most of the last 24 hours in bed.

- Diagnosed with HIV in 2000, done as a screening test when found to have gonococcal urethritis

- Was not treated with HAART at that time due to concomitant alcohol abuse and non-adherence.

- Diagnosed and treated for PJP pneumonia 2006

- Diagnosed and treated for CMV retinitis 2007

- Became sober in 2008, at which time interested in HAART. Started on Atripla, a combination pill containing: Efavirenz, Tonofovir, and Emtricitabine. He’s taken it ever since, with no adverse effects or issues with adherence. Receives care thru Dr. Smiley at the University HIV clinic.

- CD4 count 3 months ago was 400 and viral load was undetectable.

- He is homosexual though he is currently not sexually active. He has never used intravenous drugs.

- He has no history of asthma, COPD or chronic cardiac or pulmonary condition. No known liver disease. Hepatitis B and C negative. His current problem seems different to him then his past episode of PJP.

- Review of systems: negative for headache, photophobia, stiff neck, focal weakness, chest pain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, urinary symptoms, leg swelling, or other complaints.

- Hypertension x 5 years, no other known vascular disease

- Gonorrhea as above

- Alcohol abuse above and now sober – no known liver disease

- No relevant surgeries

- Atripla, 1 po qd

- Omeprazole 20 mg, 1 PO, qd

- Lisinopril 20mg, qd

- Naprosyn 250 mg, 1-2, PO, BID PRN

- No allergies

- Both of the patient's parents are alive and well (his mother is 78 and father 80). He has 2 brothers, one 45 and the other 55, who are also healthy. There is no family history of heart disease or cancer.

- Patient works as an accountant for a large firm in San Diego. He lives alone in an apartment in the city.

- Smokes 1 pack of cigarettes per day and has done so for 20 years.

- No current alcohol use. Denies any drug use.

- Sexual History as noted above; has sex exclusively with men, last partner 6 months ago.

- Seated on a gurney in the ER, breathing through a face-mask oxygen delivery system. Breathing was labored and accessory muscles were in use. Able to speak in brief sentences, limited by shortness of breath

- Vital signs: Temp 102 F, Pulse 90, BP 150/90, Respiratory Rate 26, O2 Sat (on 40% Face Mask) 95%

- HEENT: No thrush, No adenopathy

- Lungs: Crackles and Bronchial breath sounds noted at right base. E to A changes present. No wheezing or other abnormal sounds noted over any other area of the lung. Dullness to percussion was also appreciated at the right base.

- Cardiac: JVP less than 5 cm; Rhythm was regular. Normal S1 and S2. No murmurs or extra heart sounds noted.

- Abdomen and Genital exams: normal

- Extremities: No clubbing, cyanosis or edema; distal pulses 2+ and equal bilaterally.

- Skin: no eruptions noted.

- Neurological exam: normal

- WBC 18 thousand with 10% bands;

- Normal Chem 7 and LFTs.

- Room air blood gas: pH of 7.47/ PO2 of 55/PCO2 of 30.

- Sputum gram stain remarkable for an abundance of polys along with gram positive diplococci.

- CXR remarkable for dense right lower lobe infiltrate without effusion.

- Monitored care unit, with vigilance for clinical deterioration.

- Hypertension: given significant pneumonia and unclear clinical direction, will hold lisinopril. If BP > 180 and or if clear not developing sepsis, will consider restarting.

- Low molecular weight heparin

- Code Status: Wishes to be full code full care, including intubation and ICU stay if necessary. Has good quality of life and hopes to return to that functional level. Wishes to reconsider if situation ever becomes hopeless. Older brother Tom is surrogate decision maker if the patient can’t speak for himself. Tom lives in San Diego and we have his contact info. He is aware that patient is in the hospital and plans on visiting later today or tomorrow.

- Expected duration of hospitalization unclear – will know more based on response to treatment over next 24 hours.

The holdover admission (presenting data that was generated by other physicians)

- Handoff admissions are very common and present unique challenges

- Understand the reasons why the patient was admitted

- Review key history, exam, imaging and labs to assure that they support the working diagnostic and therapeutic plans

- Does the data support the working diagnosis?

- Do the planned tests and consults make sense?

- What else should be considered (both diagnostically and therapeutically)?

- This process requires that the accepting team thoughtfully review their colleagues efforts with a critical eye – which is not disrespectful but rather constitutes one of the main jobs of the accepting team and is a cornerstone of good care *Note: At some point during the day (likely not during rounds), the team will need to verify all of the data directly with the patient.

- 8-10 minutes

- Chief concern: Reason for admission (symptom and/or event)

- Temporally presented bullets of events leading up to the admission

- Review of systems

- Relevant PMH/PSH – historical information that might affect the patient during their hospitalization.

- Meds and Allergies

- Family and Social History – focusing on information that helps to inform the current presentation.

- Habits and exposures

- Physical exam, imaging and labs that were obtained in the Emergency Department

- Assessment and plan that were generated in the Emergency Department.

- Overnight events (i.e. what happened in the Emergency Dept. and after the patient went to their hospital room)? Responses to treatments, changes in symptoms?

- How does the patient feel this morning? Key exam findings this morning (if seen)? Morning labs (if available)?

- Assessment and Plan , with attention as to whether there needs to be any changes in the working differential or treatment plan. The broad organ system categories include (presented here head-to-toe): Neurological; Psychiatric; Cardiovascular; Pulmonary; Gastrointestinal; Renal/Genitourinary; Hematologic/Oncologic; Endocrine/Metabolic; Infectious; Tubes/lines/drains; Disposition.

- Chief concern: 70 yo male who presented with 10 days of progressive shoulder pain, followed by confusion. He was brought in by his daughter, who felt that her father was no longer able to safely take care for himself.

- 10 days ago, Mr. X developed left shoulder pain, first noted a few days after lifting heavy boxes. He denies falls or direct injury to the shoulder.

- 1 week ago, presented to outside hospital ER for evaluation of left shoulder pain. Records from there were notable for his being afebrile with stable vitals. Exam notable for focal pain anteriorly on palpation, but no obvious deformity. Right shoulder had normal range of motion. Left shoulder reported as diminished range of motion but not otherwise quantified. X-ray negative. Labs remarkable for wbc 8, creat 2.2 (stable). Impression was that the pain was of musculoskeletal origin. Patient was provided with Percocet and told to see PMD in f/u

- Brought to our ER last night by his daughter. Pain in shoulder worse. Also noted to be confused and unable to care for self. Lives alone in the country, home in disarray, no food.

- ROS: negative for falls, prior joint or musculoskeletal problems, fevers, chills, cough, sob, chest pain, head ache, abdominal pain, urinary or bowel symptoms, substance abuse

- Hypertension

- Coronary artery disease, s/p LAD stent for angina 3 y ago, no symptoms since. Normal EF by echo 2 y ago

- Chronic kidney disease stage 3 with creatinine 1.8; felt to be secondary to atherosclerosis and hypertension

- aspirin 81mg qd, atorvastatin 80mg po qd, amlodipine 10 po qd, Prozac 20

- Allergies: none

- Family and Social: lives alone in a rural area of the county, in contact with children every month or so. Retired several years ago from work as truck driver. Otherwise non-contributory.

- Habits: denies alcohol or other drug use.

- Temp 98 Pulse 110 BP 100/70

- Drowsy though arousable; oriented to year but not day or date; knows he’s at a hospital for evaluation of shoulder pain, but doesn’t know the name of the hospital or city

- CV: regular rate and rhythm; normal s1 and s2; no murmurs or extra heart sounds.

- Left shoulder with generalized swelling, warmth and darker coloration compared with Right; generalized pain on palpation, very limited passive or active range of motion in all directions due to pain. Right shoulder appearance and exam normal.

- CXR: normal

- EKG: sr 100; nl intervals, no acute changes

- WBC 13; hemoglobin 14

- Na 134, k 4.6; creat 2.8 (1.8 baseline 4 m ago); bicarb 24

- LFTs and UA normal

- Vancomycin and Zosyn for now

- Orthopedics to see asap to aspirate shoulder for definitive diagnosis

- If aspiration is consistent with infection, will need to go to Operating Room for wash out.

- Urine electrolytes

- Follow-up on creatinine and obtain renal ultrasound if not improved

- Renal dosing of meds

- Strict Ins and Outs.

- follow exam

- obtain additional input from family to assure baseline is, in fact, normal

- Since admission (6 hours) no change in shoulder pain

- This morning, pleasant, easily distracted; knows he’s in the hospital, but not date or year

- T Current 101F Pulse 100 BP 140/80

- Ins and Outs: IVF Normal Saline 3L/Urine output 1.5 liters

- L shoulder with obvious swelling and warmth compared with right; no skin breaks; pain limits any active or passive range of motion to less than 10 degrees in all directions

- Labs this morning remarkable for WBC 10 (from 13), creatinine 2 (down from 2.8)

- Continue with Vancomycin and Zosyn for now

- I already paged Orthopedics this morning, who are en route for aspiration of shoulder, fluid for gram stain, cell count, culture

- If aspirate consistent with infection, then likely to the OR

- Continue IVF at 125/h, follow I/O

- Repeat creatinine later today

- Not on any nephrotoxins, meds renaly dosed

- Continue antibiotics, evaluation for primary source as above

- Discuss with family this morning to establish baseline; possible may have underlying dementia as well

- SC Heparin for DVT prophylaxis

- Code status: full code/full care.

Outpatient-based presentations

There are 4 main types of visits that commonly occur in an outpatient continuity clinic environment, each of which has its own presentation style and purpose. These include the following, each described in detail below.

- The patient who is presenting for their first visit to a primary care clinic and is entirely new to the physician.

- The patient who is returning to primary care for a scheduled follow-up visit.

- The patient who is presenting with an acute problem to a primary care clinic

- The specialty clinic evaluation (new or follow-up)

It’s worth noting that Primary care clinics (Internal Medicine, Family Medicine and Pediatrics) typically take responsibility for covering all of the patient’s issues, though the amount of energy focused on any one topic will depend on the time available, acuity, symptoms, and whether that issue is also followed by a specialty clinic.

The Brand New Primary Care Patient

Purpose of the presentation

- Accurately review all of the patient’s history as well as any new concerns that they might have.

- Identify health related problems that need additional evaluation and/or treatment

- Provide an opportunity for senior listeners to intervene and offer input

Key features of the presentation

- If this is truly their first visit, then one of the main reasons is typically to "establish care" with a new doctor.

- It might well include continuation of therapies and/or evaluations started elsewhere.

- If the patient has other specific goals (medications, referrals, etc.), then this should be stated as well. Note: There may well not be a "chief complaint."

- For a new patient, this is an opportunity to highlight the main issues that might be troubling/bothering them.

- This can include chronic disorders (e.g. diabetes, congestive heart failure, etc.) which cause ongoing symptoms (shortness of breath) and/or generate daily data (finger stick glucoses) that should be discussed.

- Sometimes, there are no specific areas that the patient wishes to discuss up-front.

- Review of systems (ROS): This is typically comprehensive, covering all organ systems. If the patient is known to have certain illnesses (e.g. diabetes), then the ROS should include the search for disorders with high prevalence (e.g. vascular disease). There should also be some consideration for including questions that are epidemiologically appropriate (e.g. based on age and sex).

- Past Medical History (PMH): All known medical conditions (in particular those requiring ongoing treatment) are listed, noting their duration and time of onset. If a condition is followed by a specialist or co-managed with other clinicians, this should be noted as well. If a problem was described in detail during the “acute” history, it doesn’t have to be re-stated here.

- Past Surgical History (PSH): All surgeries, along with the year when they were performed

- Medications and allergies: All meds, including dosage, frequency and over-the-counter preparations. Allergies (and the type of reaction) should be described.

- Social: Work, hobbies, exposures.

- Sexual activity – may include type of activity, number and sex of partner(s), partner’s health.

- Smoking, Alcohol, other drug use: including quantification of consumption, duration of use.

- Family history: Focus on heritable illness amongst first degree relatives. May also include whether patient married, in a relationship, children (and their ages).

- Physical Exam: Vital signs and relevant findings (or their absence).

- Key labs and imaging if they’re available. Also when and where they were obtained.

- Summary, assessment & plan(s) presented by organ system and/or problems. As many systems/problems as is necessary to cover all of the active issues that are relevant to that clinic. This typically concludes with a “health care maintenance” section, which covers age, sex and risk factor appropriate vaccinations and screening tests.

The Follow-up Visit to a Primary Care Clinic

- Organize the presenter (forces you to think things through).

- Accurately review any relevant interval health care events that might have occurred since the last visit.

- Identification of new symptoms or health related issues that might need additional evaluation and/or treatment

- If the patient has no concerns, then verification that health status is stable

- Review of medications

- Provide an opportunity for listeners to intervene and offer input

- Reason for the visit: Follow-up for whatever the patient’s main issues are, as well as stating when the last visit occurred *Note: There may well not be a “chief complaint,” as patients followed in continuity at any clinic may simply be returning for a visit as directed by their doctor.

- Events since the last visit: This might include emergency room visits, input from other clinicians/specialists, changes in medications, new symptoms, etc.

- Review of Systems (ROS): Depth depends on patient’s risk factors and known illnesses. If the patient has diabetes, then a vascular ROS would be done. On the other hand, if the patient is young and healthy, the ROS could be rather cursory.

- PMH, PSH, Social, Family, Habits are all OMITTED. This is because these facts are already known to the listener and actionable aspects have presumably been added to the problem list (presented at the end). That said, these elements can be restated if the patient has a new symptom or issue related to a historical problem has emerged.

- MEDS : A good idea to review these at every visit.

- Physical exam: Vital signs and pertinent findings (or absence there of) are mentioned.

- Lab and Imaging: The reason why these were done should be mentioned and any key findings mentioned, highlighting changes from baseline.

- Assessment and Plan: This is most clearly done by individually stating all of the conditions/problems that are being addressed (e.g. hypertension, hypothyroidism, depression, etc.) followed by their specific plan(s). If a new or acute issue was identified during the visit, the diagnostic and therapeutic plan for that concern should be described.

The Focused Visit to a Primary Care Clinic

- Accurately review the historical events that lead the patient to make the appointment.

- Identification of risk factors and/or other underlying medical conditions that might affect the diagnostic or therapeutic approach to the new symptom or concern.

- Generate an appropriate assessment and plan

- Allow the listener to comment

Key features of the presentation:

- Reason for the visit

- History of Present illness: Description of the sequence of symptoms and/or events that lead to the patient’s current condition.

- Review of Systems: To an appropriate depth that will allow the listener to grasp the full range of diagnostic possibilities that relate to the presenting problem.

- PMH and PSH: Stating only those elements that might relate to the presenting symptoms/issues.

- PE: Vital signs and key findings (or lack thereof)

- Labs and imaging (if done)

- Assessment and Plan: This is usually very focused and relates directly to the main presenting symptom(s) or issues.

The Specialty Clinic Visit

Specialty clinic visits focus on the health care domains covered by those physicians. For example, Cardiology clinics are interested in cardiovascular disease related symptoms, events, labs, imaging and procedures. Orthopedics clinics will focus on musculoskeletal symptoms, events, imaging and procedures. Information that is unrelated to these disciples will typically be omitted. It’s always a good idea to ask the supervising physician for guidance as to what’s expected to be covered in a particular clinic environment.

- Highlight the reason(s) for the visit

- Review key data

- Provide an opportunity for the listener(s) to comment

- 5-7 minutes

- If it’s a consult, state the main reason(s) that the patient was referred as well as who referred them.

- If it’s a return visit, state the reasons why the patient is being followed in the clinic and when the last visit took place

- If it’s for an acute issue, state up front what the issue is Note: There may well not be a “chief complaint,” as patients followed in continuity in any clinic may simply be returning for a return visit as directed

- For a new patient, this highlights the main things that might be troubling/bothering the patient.

- For a specialty clinic, the history presented typically relates to the symptoms and/or events that are pertinent to that area of care.

- Review of systems , focusing on those elements relevant to that clinic. For a cardiology patient, this will highlight a vascular ROS.

- PMH/PSH that helps to inform the current presentation (e.g. past cardiac catheterization findings/interventions for a patient with chest pain) and/or is otherwise felt to be relevant to that clinic environment.

- Meds and allergies: Typically all meds are described, as there is always the potential for adverse drug interactions.

- Social/Habits/other: as relates to/informs the presentation and/or is relevant to that clinic

- Family history: Focus is on heritable illness amongst first degree relatives

- Physical Exam: VS and relevant findings (or their absence)

- Key labs, imaging: For a cardiology clinic patient, this would include echos, catheterizations, coronary interventions, etc.

- Summary, assessment & plan(s) by organ system and/or problems. As many systems/problems as is necessary to cover all of the active issues that are relevant to that clinic.

- Reason for visit: Patient is a 67 year old male presenting for first office visit after admission for STEMI. He was referred by Dr. Goins, his PMD.

- The patient initially presented to the ER 4 weeks ago with acute CP that started 1 hour prior to his coming in. He was found to be in the midst of a STEMI with ST elevations across the precordial leads.

- Taken urgently to cath, where 95% proximal LAD lesion was stented

- EF preserved by Echo; Peak troponin 10

- In-hospital labs were remarkable for normal cbc, chem; LDL 170, hdl 42, nl lfts

- Uncomplicated hospital course, sent home after 3 days.

- Since home, he states that he feels great.

- Denies chest pain, sob, doe, pnd, edema, or other symptoms.

- No symptoms of stroke or TIA.

- No history of leg or calf pain with ambulation.

- Prior to this admission, he had a history of hypertension which was treated with lisinopril

- 40 pk yr smoking history, quit during hospitalization

- No known prior CAD or vascular disease elsewhere. No known diabetes, no family history of vascular disease; He thinks his cholesterol was always “a little high” but doesn’t know the numbers and was never treated with meds.

- History of depression, well treated with prozac

- Discharge meds included: aspirin, metoprolol 50 bid, lisinopril 10, atorvastatin 80, Plavix; in addition he takes Prozac for depression

- Taking all of them as directed.

- Patient lives with his wife; they have 2 grown children who are no longer at home

- Works as a computer programmer

- Smoking as above

- ETOH: 1 glass of wine w/dinner

- No drug use

- No known history of cardiovascular disease among 2 siblings or parents.

- Well appearing; BP 130/80, Pulse 80 regular, 97% sat on Room Air, weight 175lbs, BMI 32

- Lungs: clear to auscultation

- CV: s1 s2 no s3 s4 murmur

- No carotid bruits

- ABD: no masses

- Ext; no edema; distal pulses 2+

- Cath from 4 weeks ago: R dominant; 95% proximal LAD; 40% Cx.

- EF by TTE 1 day post PCI with mild Anterior Hypokinesis, EF 55%, no valvular disease, moderate LVH

- Labs of note from the hospital following cath: hgb 14, plt 240; creat 1, k 4.2, lfts normal, glucose 100, LDL 170, HDL 42.

- EKG today: SR at 78; nl intervals; nl axis; normal r wave progression, no q waves

- Plan: aspirin 81 indefinitely, Plavix x 1y

- Given nitroglycerine sublingual to have at home.

- Reviewed symptoms that would indicate another MI and what to do if occurred

- Plan: continue with current dosages of meds

- Chem 7 today to check k, creatinine

- Plan: Continue atorvastatin 80mg for life

- Smoking cessation: Doing well since discharge without adjuvant treatments, aware of supports.

- Plan: AAA screening ultrasound

The Clinical Presentation

- First Online: 01 January 2013

Cite this chapter

- Sergio V. Delgado 3 &

- Jeffrey R. Strawn 4

980 Accesses

Presenting case material to colleagues requires preparation, whether the presentation is to be made casually during bedside rounds or in the formal environment of a national meeting. It is rewarding when a presentation is well received, particularly because it may prove helpful to other clinicians, allied health professionals, and researchers. Regardless of the setting, the presenter’s goal is to share their knowledge based on observations they have made and lessons they have learned from the case or cases. The most time-consuming aspect of the patient-oriented presentation is collecting and organizing as much information as possible about the patients, their families, and others who were involved in the patients’ care. Once these tasks are complete, the presenter must summarize the information and place it within the context of treatment data and consensus approaches. Tailoring the talk to the audience is also of paramount importance. Different groups will invariably come from different disciplines, and the presentation will need to be tailored to accommodate each audience’s background, interests and goals.

Make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler —Albert Einstein (1879–1955)

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Altman LK (2006) Socratic dialogue gives way to powerpoint®. New York Times, 12 Dec 2006

Google Scholar

Blechner MJ (2012) Confidentiality: against disguise, for consent. Psychotherapy (Chic) 49(1):16–18

Article Google Scholar

Clifft MA (1986) Writing about psychiatric patients. Guidelines for disguising case material. Bull Menninger Clin 50(6):511–524

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Copeland HL, Hewson MG, Stoller JK et al (1998) Making the continuing medical education lecture effective. J Contin Educ Health Prof 18:227–234

Gabbard GO (2000) Disguise or consent: problems and recommendations concerning the publication and presentation of clinical material. Int J Psychoanal 81:1071–1086

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gabbard GO, Williams P (2001) Preserving confidentiality in writing of case reports. Int J Psychoanal 82:1067–1068

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP (1989) A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof 9(4):257–266

Lorin MI, Palazzi DL, Turner TL et al (2008) What is a clinical pearl and what is its role in medical education? Med Teach 30(9–10):870–874

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA et al (1996) Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. Br Med J 312:71–72

Article CAS Google Scholar

Tuckett D (2000) Reporting clinical events in the journal: towards the constructing of a special case. Int J Psychoanal 81:1065–1069

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Sergio V. Delgado

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Jeffrey R. Strawn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Delgado, S.V., Strawn, J.R. (2014). The Clinical Presentation. In: Difficult Psychiatric Consultations. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39552-9_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39552-9_8

Published : 16 September 2013

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-642-39551-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-642-39552-9

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 November 2020

Clinical presentations, laboratory and radiological findings, and treatments for 11,028 COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Carlos K. H. Wong 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Janet Y. H. Wong 3 na1 ,

- Eric H. M. Tang 1 ,

- C. H. Au 1 &

- Abraham K. C. Wai 4

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 19765 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

5978 Accesses

47 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

- Medical research

- Microbiology

- Risk factors

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the comorbidities, symptoms, clinical characteristics and treatment of COVID-19 patients. Epidemiological studies published in 2020 (from January–March) on the clinical presentation, laboratory findings and treatments of COVID-19 patients were identified from PubMed/MEDLINE and Embase databases. Studies published in English by 27th March, 2020 with original data were included. Primary outcomes included comorbidities of COVID-19 patients, their symptoms presented on hospital admission, laboratory results, radiological outcomes, and pharmacological and in-patient treatments. 76 studies were included in this meta-analysis, accounting for a total of 11,028 COVID-19 patients in multiple countries. A random-effects model was used to aggregate estimates across eligible studies and produce meta-analytic estimates. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (18.1%, 95% CI 15.4–20.8%). The most frequently identified symptoms were fever (72.4%, 95% CI 67.2–77.7%) and cough (55.5%, 95% CI 50.7–60.3%). For pharmacological treatment, 63.9% (95% CI 52.5–75.3%), 62.4% (95% CI 47.9–76.8%) and 29.7% (95% CI 21.8–37.6%) of patients were given antibiotics, antiviral, and corticosteroid, respectively. Notably, 62.6% (95% CI 39.9–85.4%) and 20.2% (95% CI 14.6–25.9%) of in-patients received oxygen therapy and non-invasive mechanical ventilation, respectively. This meta-analysis informed healthcare providers about the timely status of characteristics and treatments of COVID-19 patients across different countries.

PROSPERO Registration Number: CRD42020176589

Similar content being viewed by others

Global prevalence and effect of comorbidities and smoking status on severity and mortality of COVID-19 in association with age and gender: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression

Frequency, risk factors, and outcomes of hospital readmissions of COVID-19 patients

Risk factors for severe COVID-19 differ by age for hospitalized adults

Introduction.

Following the possible patient zero of coronavirus infection identified in early December 2019 1 , the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been recognized as a pandemic in mid-March 2020 2 , after the increasing global attention to the exponential growth of confirmed cases 3 . As on 29th March, 2020, around 690 thousand persons were confirmed infected, affecting 199 countries and territories around the world, in addition to 2 international conveyances: the Diamond Princess cruise ship harbored in Yokohama, Japan, and the Holland America's MS Zaandam cruise ship. Overall, more than 32 thousand died and about 146 thousand have recovered 4 .

A novel bat-origin virus, 2019 novel coronavirus, was identified by means of deep sequencing analysis. SARS-CoV-2 was closely related (with 88% identity) to two bat-derived severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-like coronaviruses, bat-SL-CoVZC45 and bat-SL-CoVZXC21, but were more distant from SARS-CoV (about 79%) and MERS-CoV (about 50%) 5 , both of which were respectively responsible for two zoonotic human coronavirus epidemics in the early twenty-first century. Following a few initial human infections 6 , the disease could easily be transmitted to a substantial number of individuals with increased social gathering 7 and population mobility during holidays in December and January 8 . An early report has described its high infectivity 9 even before the infected becomes symptomatic 10 . These natural and social factors have potentially influenced the general progression and trajectory of the COVID-19 epidemiology.

By the end of March 2020, there have been approximately 3000 reports about COVID-19 11 . The number of COVID-19-related reports keeps growing everyday, yet it is still far from a clear picture on the spectrum of clinical conditions, transmissibility and mortality, alongside the limitation of medical reports associated with reporting in real time the evolution of an emerging pathogen in its early phase. Previous reports covered mostly the COVID-19 patients in China. With the spread of the virus to other continents, there is an imminent need to review the current knowledge on the clinical features and outcomes of the early patients, so that further research and measures on epidemic control could be developed in this epoch of the pandemic.

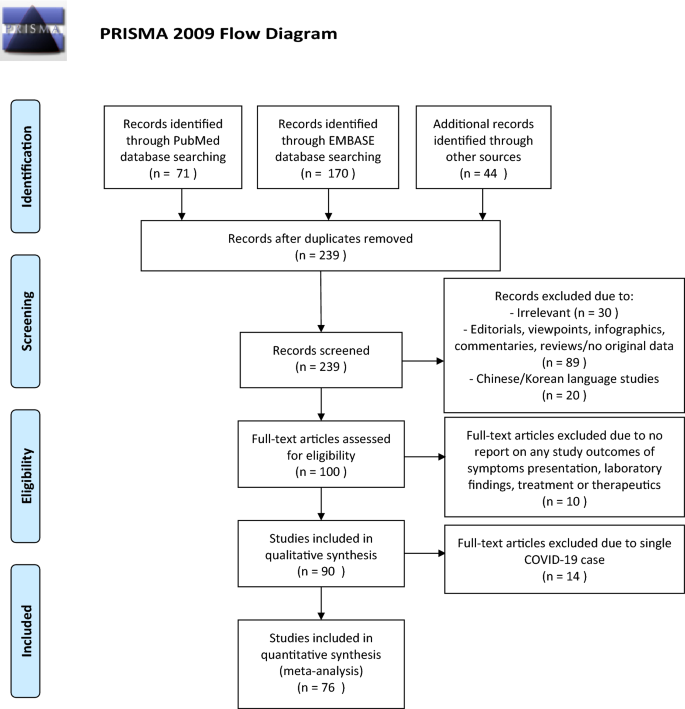

Search strategy and selection criteria

The systematic review was conducted according to the protocol registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42020176589). Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline throughout this review, data were identified by searches of MEDLINE, Embase and references from relevant articles using the search terms "COVID", “SARS-CoV-2”, and “novel coronavirus” (Supplementary material 1 ). Articles published in English up to 27th March, 2020 were included. National containment measures have been implemented at many countries, irrespective of lockdown, curfew, or stay-at-home orders, since the mid of March 2020 12 , except for China where imposed Hubei province lockdown at 23th January 2020, Studies with original data including original articles, short and brief communication, letters, correspondences were included. Editorials, viewpoints, infographics, commentaries, reviews, or studies without original data were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they were animal studies, modelling studies, or did not measure symptoms presentation, laboratory findings, treatment and therapeutics during hospitalization.

After the removal of duplicate records, two reviewers (CW and CHA) independently screened the eligibility criteria of study titles, abstracts and full-texts, and reference lists of the studies retrieved by the literature search. Disagreements regarding the procedures of database search, study selection and eligibility were resolved by discussion. The second and the last authors (JW and AW) verified the eligibility of included studies.

Outcomes definitions

Signs and symptoms were defined as the presentation of fever, cough, sore throat, headache, dyspnea, muscle pain, diarrhea, rhinorrhea, anosmia, and ageusia at the hospital admission 13 .

Laboratory findings included a complete blood count (white blood count, neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet count), procalcitonin, prothrombin time, urea, and serum biochemical measurements (including electrolytes, renal-function and liver-function values, creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, C-reactive protein, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate), and treatment measures (i.e. antiviral therapy, antibiotics, corticosteroid therapy, mechanical ventilation, intubation, respiratory support, and renal replacement therapy). Radiological outcomes included bilateral involvement identified and pneumonia identified by chest radiograph.

Comorbidities of patients evaluated in this study were hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, liver disease and cancer.

In-patient treatment included intensive care unit admission, oxygen therapy, non-invasive ventilation, mechanical ventilation, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), renal replacement therapy, and pharmacological treatment. Use of antiviral and interferon drugs (Lopinavir/ritonavir, Ribavirin, Umifenovir, Interferon-alpha, or Interferon-beta), antibiotic drugs, corticosteroid, and inotropes (Nor-adrenaline, Adrenaline, Vasopressin, Phenylephrine, Dopamine, or Dobutamine) were considered.

Data analysis

Three authors (CW, EHMT and CHA) extracted data using a standardized spreadsheet to record the article type, country of origin, surname of first author, year of publications, sample size, demographics, comorbidities, symptoms, laboratory and radiology results, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments.

We aggregated estimates across 90 eligible studies to produce meta-analytic estimates using a random-effects model. For dichotomous outcomes, we estimated the proportion and its respective 95% confidence interval. For laboratory parameters as continuous outcomes, we estimated the mean and standard deviation from the median and interquartile range if the mean and standard deviation were not available from the study 14 , and calculated the mean and its respective 95% confidence intervals. Random-effect models on DerSimonian and Laird method were adopted due to the significant heterogeneity, checked by the I 2 statistics and the p values. I 2 statistic of < 25%, 25–75% and ≥ 75% is considered as low, moderate, high likelihood of heterogeneity. Pooled estimates were calculated and presented by using forest plots. Publication bias was estimated by Egger’s regression test. Funnel plots of outcomes were also presented to assess publication bias.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the STATA Version 13.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). The random effects model was generated by the Stata packages ‘Metaprop’ for proportions 15 and ‘Metan’ for continuous variables 16 .

The selection and screen process are presented in Fig. 1 . A total of 241 studies were found by our searching strategy (71 in PubMed and 170 in Embase). 46 records were excluded due to duplication. After screening the abstracts and titles, 100 English studies were with original data and included in full-text screening. By further excluding 10 studies with not reporting symptoms presentation, laboratory findings, treatment and therapeutics, 90 studies 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 and 76 studies with more than one COVID-19 case 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 53 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 67 , 69 , 70 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 98 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 were included in the current systematic review and meta-analysis respectively. 73.3% 66 studies were conducted in China. Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale has been used to assess study quality of each included cohort study 107 . 30% (27/90) of included studies had satisfactory or good quality. The summary of the included study is shown in Table 1 .

PRISMA flowchart reporting identification, searching and selection processes.

Of those 90 eligible studies, 11,028 COVID-19 patients were identified and included in the systematic review. More than half of patients (6336, 57.5%) were from mainland China. The pooled mean age was 45.8 (95% CI 38.6–52.5) years and 49.3% (pooled 95% CI 45.6–53.0%) of them were male.

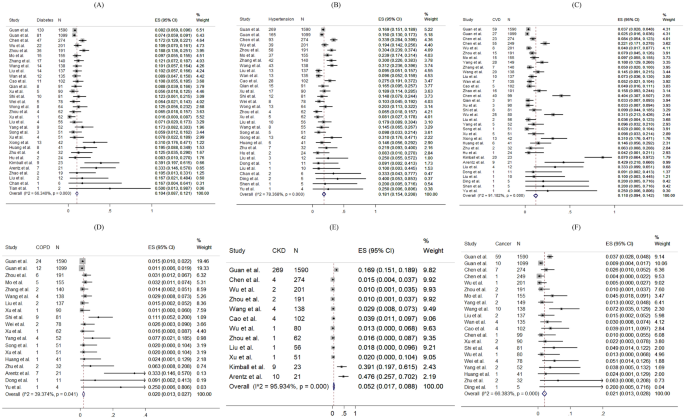

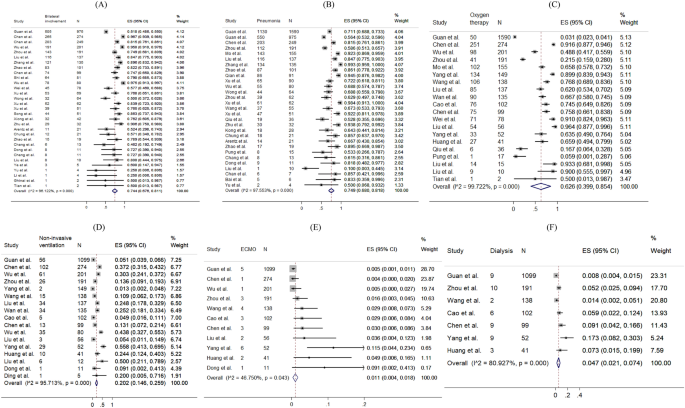

For specific comorbidity status, the most prevalent comorbidity was hypertension (18.1%, 95% CI 15.4–20.8%), followed by cardiovascular disease (11.8%, 95% CI 9.4–14.2%) and diabetes (10.4%, 95% CI 8.7–12.1%). The pooled prevalence (95% CI) of COPD, chronic kidney disease, liver disease and cancer were 2.0% (1.3–2.7%), 5.2% (1.7–8.8%), 2.5% (1.7–3.4%) and 2.1% (1.3–2.8%) respectively. Moderate to substantial heterogeneity between reviewed studies were found, with I 2 statistics ranging from 39.4 to 95.9% ( p values between < 0.001–0.041), except for liver disease (I 2 statistics: 1.7%, p = 0.433). Detailed results for comorbidity status are displayed in Fig. 2 .

Random-effects meta-analytic estimates for comorbidities. ( A ) Diabetes mellitus, ( B ) Hypertension, ( C ) Cardiovascular disease, ( D ) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ( E ) Chronic kidney disease, ( F ) Cancer.

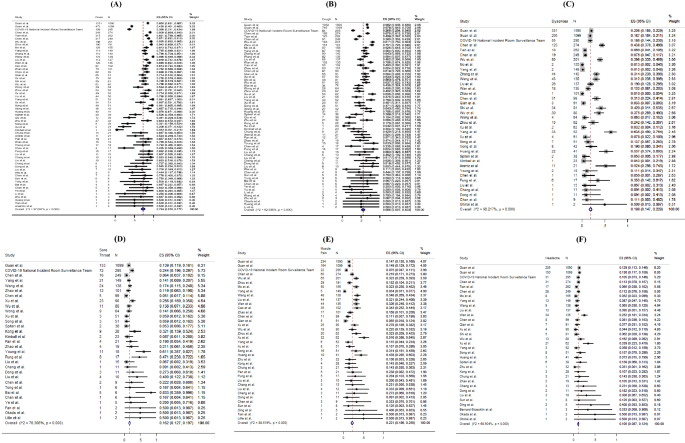

Regarding the symptoms presented at hospital admission, the most frequent symptoms were fever (pooled prevalence: 72.4%, 95% CI 67.2–77.7%) and cough (pooled prevalence: 55.5%, 95% CI 50.7–60.3%). Sore throat (pooled prevalence: 16.2%, 95% CI 12.7–19.7%), dyspnoea (pooled prevalence: 18.8%, 95% CI 14.7–22.8%) and muscle pain (pooled prevalence: 22.1%, 95% CI 18.6–25.5%) were also common symptoms found in COVID-19 patients, but headache (pooled prevalence: 10.5%, 95% CI 8.7–12.4%), diarrhoea (pooled prevalence: 7.9%, 95% CI 6.3–9.6%), rhinorrhoea (pooled prevalence: 9.2%, 95% CI 5.6–12.8%) were less common. However, none of the included papers reported prevalence of anosmia and ageusia. The I 2 statistics varied from 68.5 to 97.1% (all p values < 0.001), indicating a high heterogeneity exists across studies. Figure 3 shows the pooled proportion of symptoms of patients presented at hospital.

Random-effects meta-analytic estimates for presenting symptoms. ( A ) Fever, ( B ) Cough, ( C ) Dyspnoea, ( D ) Sore throat, ( E ) Muscle pain, ( F ) Headache.

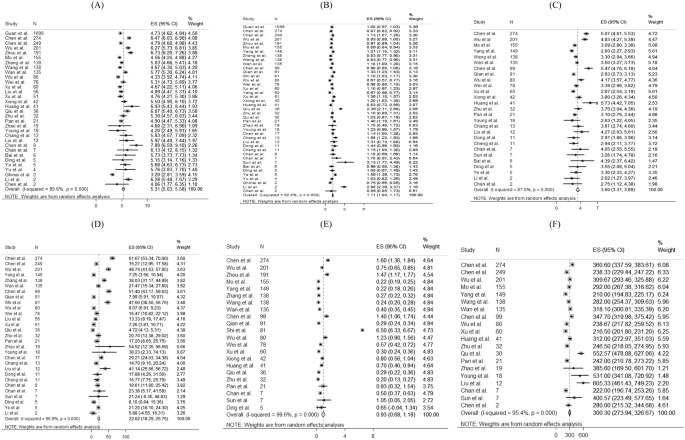

For laboratory parameters, white blood cell (pooled mean: 5.31 × 10 9 /L, 95% CI 5.03–5.58 × 10 9 /L), neutrophil (pooled mean: 3.60 × 10 9 /L, 95% CI 3.31–3.89 × 10 9 /L), lymphocyte (pooled mean: 1.11 × 10 9 /L, 95% CI 1.04–1.17 × 10 9 /L), platelet count (pooled mean: 179.5 U/L, 95% CI 172.6–186.3 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (pooled mean: 30.3 U/L, 95% CI 27.9–32.7 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (pooled mean: 27.0 U/L, 95% CI 24.4–29.6 U/L) and C-reactive protein (CRP) (pooled mean: 22.0 mg/L, 95% CI 18.3–25.8 mg/L) and D-dimer (0.93 mg/L, 95% CI 0.68–1.18 mg/L) were the common laboratory test taken for COVID-19 patients. Above results and other clinical factors are depicted in Fig. 4 . Same with the comorbidity status and symptoms, high likelihood of heterogeneity was detected by I 2 statistics for a majority of clinical parameters.

Random-effects meta-analytic estimates for laboratory parameters. ( A ) White blood cell, ( B ) Lymphocyte, ( C ) Neutrophil, ( D ) C-creative protein, ( E ) D-dimer, ( F ) Lactate dehydrogenase.

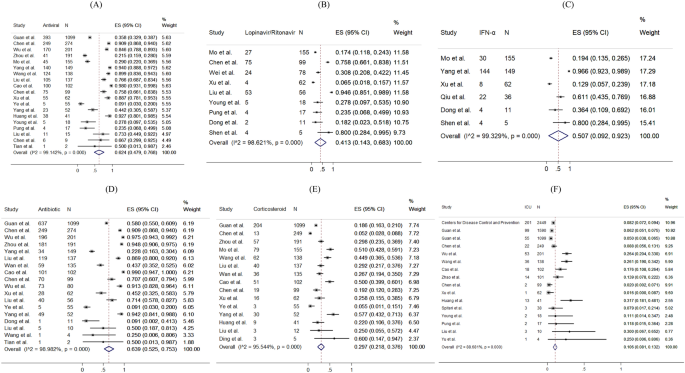

Figure 5 presents the distribution of the pharmacological treatments received for COVID-19 patients. 10.6% of patients admitted to intensive care units (pooled 95% CI 8.1–13.2%). For drug treatment, 63.9% (pooled 95% CI 52.5–75.3%), 62.4% (pooled 95% CI 47.9–76.8%) and 29.7% (pooled 95% CI 21.8–37.6%) patients used antibiotics, antiviral, and corticosteroid, respectively. 41.3% (pooled 95% CI 14.3–68.3%) and 50.7% (pooled 95% CI 9.2–92.3%) reported using Lopinavir/Ritonavir and interferon-alpha as antiviral drug treatment, respectively. Among 14 studies reporting proportion of corticosteroid used, 7 studies (50%) specified the formulation of corticosteroid as systemic corticosteroid. The remaining one specified the use of methylprednisolone. No reviewed studies reported the proportion of patients receiving Ribavirin, Interferon-beta, or inotropes.

Random-effects meta-analytic estimates for pharmacological treatments and intensive unit care at hospital. ( A ) Antiviral or interferon drugs, ( B ) Lopinavir/Ritonavir, ( C ) Interferon alpha (IFN-α), ( D ) Antibiotic drugs, ( E ) Corticosteroid, ( F ) Admission to Intensive care unit.

The prevalence of radiological outcomes and non-pharmacological treatments were presented in Fig. 6 . Radiology findings detected chest X-ray abnormalities, with 74.4% (95% CI 67.6–81.1%) of patients with bilateral involvement and 74.9% (95% CI 68.0–81.8%) of patients with viral pneumonia. 62.6% (pooled 95% CI 39.9–85.4%), 20.2% (pooled 95% CI 14.6–25.9%), 15.3% (pooled 95% CI 11.0–19.7%), 1.1% (pooled 95% CI 0.4–1.8%) and 4.7% (pooled 95% CI 2.1–7.4%) took oxygen therapy, non-invasive ventilation, mechanical ventilation, ECMO and dialysis respectively.

Random-effects meta-analytic estimates for radiological findings and non-pharmacological treatments at hospital. ( A ) Bilateral involvement, ( B ) Pneumonia, ( C ) Oxygen therapy, ( D ) Non-invasive ventilation, ( E ) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), ( F ) Dialysis.

The funnel plots and results Egger’s test of comorbidity status, symptoms presented, laboratory test and treatment were presented in eFigure 1 – S5 in the Supplement. 63% (19/30) of the funnel plots (eFigure 1 – S5 ) showed significance in the Egger’s test for asymmetry, suggesting the possibility of publication bias or small-study effects caused by clinical heterogeneity.

This meta-analysis reveals the condition of global medical community responding to COVID-19 in the early phase. During the past 4 months, a new major epidemic focus of COVID-19, some without traceable origin, has been identified. Following its first identification in Wuhan, China, the virus has been rapidly spreading to Europe, North America, Asia, and the Middle East, in addition to African and Latin American countries. Three months since Wuhan CDC admitted that there was a cluster of unknown pneumonia cases related to Huanan Seafood Market and a new coronavirus was identified as the cause of the pneumonia 108 , as on 1 April, 2020, there have been 858,371 persons confirmed infected with COVID-19, affecting 202 countries and territories around the world. Although this rapid review is limited by the domination of reports from patients in China, and the patient population is of relative male dominance reflecting the gender imbalance of the Chinese population 109 , it provides essential information.

In this review, the pooled mean age was 45.8 years. Similar to the MERS-CoV pandemic 110 , middle-aged adults were the at-risk group for COVID-19 infections in the initial phase, which was different from the H1N1 influenza pandemic where children and adolescents were more frequently affected 111 . Biological differences may affect the clinical presentations of infections; however, in this review, studies examining the asymptomatic COVID-19 infections or reporting any previous infections were not included. It is suggested that another systematic review should be conducted to compare the age-specific incidence rates between the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic periods, so as to understand the pattern and spread of the disease, and tailor specific strategies in infection control.

Both sexes exhibited clinical presentations similar in symptomatology and frequency to those noted in other severe acute respiratory infections, namely influenza A H1N1 112 and SARS 113 , 114 . These generally included fever, new onset or exacerbation of cough, breathing difficulty, sore throat and muscle pain. Among critically ill patients usually presented with dyspnoea and chest tightness 22 , 29 , 39 , 72 , 141 (4.6%) of them with persistent or progressive hypoxia resulted in the requirement of intubation and mechanical ventilation 115 , while 194 (6.4%) of them required non-invasive ventilation, yielding a total of 11% of patients requiring ventilatory support, which was similar to SARS 116 .

The major comorbidities identified in this review included hypertension, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus. Meanwhile, the percentages of patients with chronic renal diseases and cancer were relatively low. These chronic conditions influencing the severity of COVID-19 had also been noted to have similar effects in other respiratory illnesses such as SARS, MERS-CoV and influenza 117 , 118 . Higher mortality had been observed among older patients and those with comorbidities.

Early diagnosis of COVID-19 was based on recognition of epidemiological linkages; the presence of typical clinical, laboratory, and radiographic features; and the exclusion of other respiratory pathogens. The case definition had initially been narrow, but was gradually broadened to allow for the detection of more cases, as milder cases and those without epidemiological links to Wuhan or other known cases had been identified 119 , 120 . Laboratory investigations among COVID-19 patients did not reveal specific characteristics—lymphopenia and elevated inflammatory markers such as CRP are some of the most common haematological and biochemical abnormalities, which had also been noticed in SARS 121 . None of these features were specific to COVID-19. Therefore, diagnosis should be confirmed by SARS-CoV–2 specific microbiological and serological studies, although initial management will continue to be based on a clinical and epidemiological assessment of the likelihood of a COVID-19 infection.

Radiology imaging often plays an important role in evaluating patients with acute respiratory distress; however, in this review, radiological findings of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia were non-specific. Despite chest radiograph usually revealed bilateral involvement and Computed Tomography usually showed bilateral multiple ground-glass opacities or consolidation, there were also patients with normal chest radiograph, implying that chest radiograph might not have high specificity to rule out pneumonia in COVID-19.

Limited clinical data were available for asymptomatic COVID-19 infected persons. Nevertheless, asymptomatic infection could be unknowingly contagious 122 . From some of the official figures, 6.4% of 150 non-travel-related COVID-19 infections in Singapore 123 , 39.9% of cases from the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan 124 , and up to 78% of cases in China as extracted on April 1st, 2020, were found to be asymptomatic 122 . 76% (68/90) studies based on hospital setting which provided care and disease management to symptomatic patients had limited number of asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 infection. This review calls for further studies about clinical data of asymptomatic cases. Asymptomatic infection intensifies the challenges of isolation measures. More global reports are crucially needed to give a better picture of the spectrum of presentations among all COVID-19 infected persons. Also, public health policies including social and physical distancing, monitoring and surveillance, as well as contact tracing, are necessary to reduce the spread of COVID-19.