Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

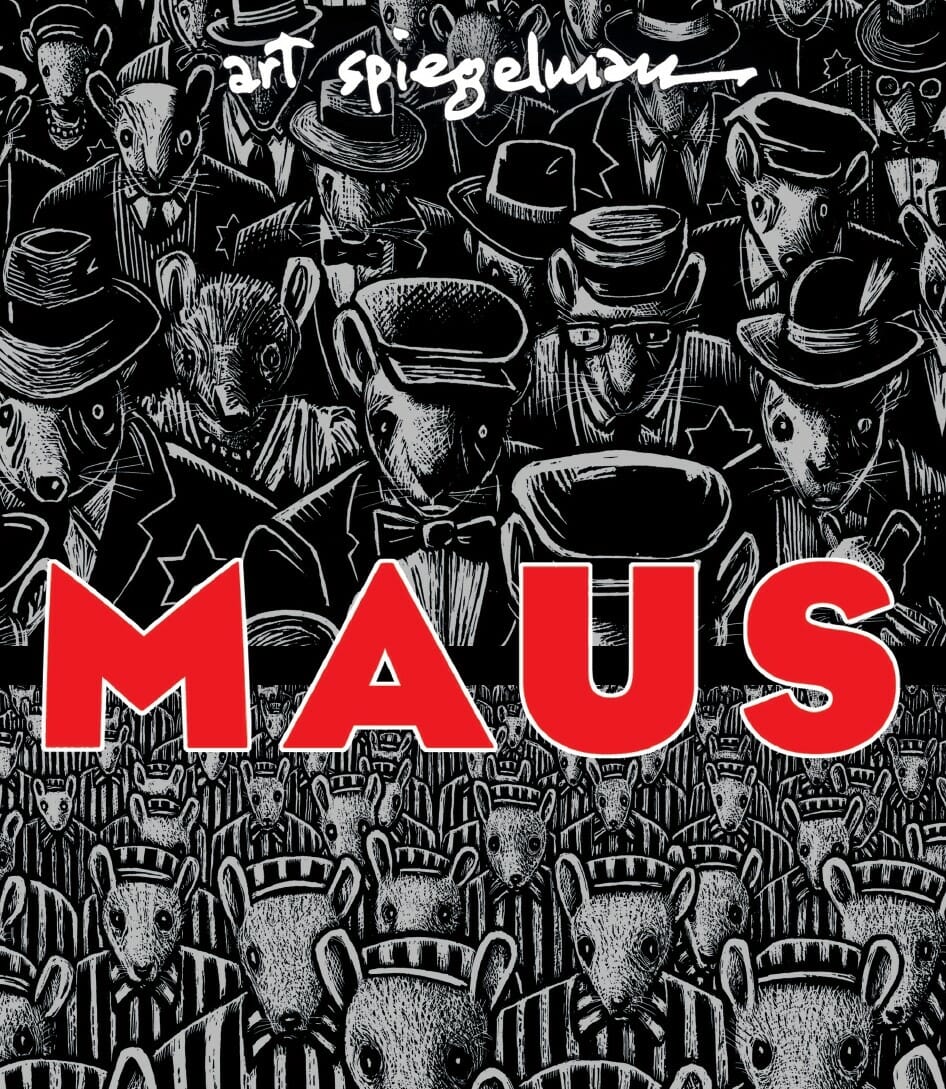

Art Spiegelman's Maus: An EthnoGraphic Memoir

(Capstone Paper) Maus by Art Spiegelman is an intersection of historic research and literary genres through an unusual mode making it worthy of canonization.

Related Papers

Rohan Dhoot

Abdul Walid Azizi

The graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman is the story of the writer’s own parents who survived several Nazi concentration camps, including Auschwitz. In the novel, Jews are depicted as mice and Germans as cats. Spiegelman’s father has trouble coming into terms with the war experience. He, as the son of two Holocaust survivors, also struggles to make sense of the brutal reality of the war and the concentration camps. The irrelevant digressions in the text is a significant indicator of the writer’s difficulty to come into terms with the horror of war while, paradoxically, these digressions assist him to articulate ideas and put his parents’ story into paper. Spiegelman employs the dialogue form to overcome this struggle and communicate about the brutal reality of the war and Auschwitz. Opposite to the typical narratives, the author then employs the comics form—replacing the human figures with the animal cats and mice masks—to speak of the unspeakable horrifying tale. Using this particular form of comics enables the writer to disrupt the linear time concept and, consequently, aids him to report his parents’ story.

Dr. Naila Sahar

Art Spiegelman’s act of writing (and drawing) Maus is an act of breaking silences. It’s an act of reinterpreting and reconstructing history. By collecting personal memories of his father, Spiegelman recovers, commemorates and recollects the collective heritage of a trauma in a society, where denial and erasure are primary tools of historiography.

DISCOVERY: Georgia State Honors College Undergraduate Research Journal

Jonathan Kincade

Julian Lawrence

Philip Smith

Art Spiegelman is one of the most-discussed creators in Comic Book Studies. His Pulitzer-winning work Maus (1980 and 1991) was, alongside The Dark Knight Returns (1986) and Watchmen (1987), the catalyst to a sea change in the commercial and critical fortunes of the alternative comic book during the mid-1980s. It has been a landmark text in critical discourses on comics ever since. The purpose of this and its companion paper is to offer a synthesis and reinvestigation of both the existing critical literature on Spiegelman as well as, perhaps most importantly, the lacunae within that literature. The aims of these two papers, then, are two-fold: firstly, to establish where we have got to and, secondly, to suggest some directions for the future of Spiegelman scholarship. This, the first of the two papers, will be devoted to the richest vein of Spiegelman scholarship, on Maus.

Prandium the Journal of Historical Studies at U of T Mississauga

Puneet Kohli

Critical Arts: A South-North Journal of Cultural & Media Studies

Liam Kruger

An examination of the specifically graphic-novelistic strategies employed in Art Spiegelman’s graphic memoir, Maus, in leading the reader into a punctuated experience of time and memory, and in forcing complicity with the novel’s problematic animal-as-ethnicity metaphor, in a wider attempt at putting together the critical vocabulary for discussing comic books as simultaneously textual and pictorial ‘texts.’

Erin McGlothlin

Yasmeen Rabia Razack

Art Spiegelman's "Maus" is an emotional graphic novel about the life of Spiegelman himself and the atrocities that his parents faced during the Holocaust. This paper looks at Spiegelman's use of animals as characters and how that connects to the idea of "dehumanization."

RELATED PAPERS

Jedy De la Cruz

Himanshu Ji Sharma

International Journal of Communication Systems

behnaz mohammadi

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

JUCS - Journal of Universal Computer Science

Ashot Harutyunyan

Clinical Pharmacokinetics

Lene Høimark

Research in Virology

Pierre Coursaget

Revista Tecnológica-Educativa Docentes 2.0

Marcos Miguel Coronado Terrones

怎么办理usyd学位证书 悉尼大学毕业证学位证书案例GRE证书原版一模一样

British Journal of Nutrition

Muneeb Ur Rehman

sumri shamri

Call Girls Hyderabad

Journal of Dairying, Foods & Home Sciences

Dr. Luna Dutta Baruah

Lira Sekantsi

Leopold Fezeu

Texto Livre: Linguagem e Tecnologia

Carlos Alexandre Rodrigues de Oliveira

Agricultural Economics

patrice adegbola

Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva

Nelson Filice de Barros

The Journal of Community Health Management

kartik patil

Neurochemistry International

Mohaddeseh Behjati , Mojtaba Ehsanifar

arte e ensaios

Eduardo Montelli

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

'Maus' author Art Spiegelman shares the story behind his Pulitzer-winning work

Terry Gross

Spiegelman's graphic novel, which was recently banned by a school district in Tennessee, tells the story of how his Jewish parents survived the Holocaust in Poland. Originally broadcast in 1987.

Copyright © 2022 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- Update your cookie preferences

- The Hypercritic Project

- Hypercritic for Companies

- Media coverage of Hypercritic’s work

- Meet the Hypercritics

- Collections

- Write To Us

Don’t miss a thing

Supported by

Copyright 2022 © All rights Reserved. Iscrizione registro stampa n. cronol. 4548/2020 del 11/03/2020 RG n. 6985/2020 al Tribunale di Torino. Use of Hypercritic constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use , Privacy Policy , Cookie Policy

- Maus | Art Spiegelman’s graphic analysis of war

Maus | Art Spiegelman's graphic analysis of war

Big - Little

Fast - Slow

Easy - Hard

Clean - Dirty

In 1978 Art Spiegelman convinced his reluctant father, Vladek , to talk to him about his experience as a Polish Jew during the Second World War . What came out of it was a serial of comics about a life smashed up by the Holocaust. After nearly forty years, Spiegelman’s Maus confirms itself to be a postmodern analysis of Word War II.

Later on, Pantheon Books published Maus in several volumes and then in a single-volume edition, but its first appearance was in December 1980. It was an insert in Raw , a magazine founded by Spiegelman himself and his wife Françoise Mouly in the same year. It was an influential magazine in the comics field and treated them as a cultural object worth disseminating and analyzing, and not just as entertainment.

Spiegelman’s Maus is the first and only graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize , in 1992. In 2011 the author made MetaMaus , a complete guide and detailed study of Maus , including contents such as an interview with Spiegelman, sketches, photographs and the original versions of Vladek’s recordings.

A survivor tale

The first panels, with Art visiting his father in New York , build a narrative frame leading the narration. The main focus remains on Vladek’s experience , while the framing allows the reader to understand Art’s point of view. The storyline swings in and out of the two timelines, giving a genuine view of Spiegelman’s family. The narration of the past represents a discovery of the author’s background, but it also allows him to develop his relationship with his father. It’s the story of the survivor Vladek and of the son Art discovering his family origins.

In the first part, Vladek speaks about his marriage with Art’s mother, Anja , in 1937. The Nazis invaded Poland shortly after and sent him to a work camp. On his release, life for Jewish people became more and more difficult. In 1943, the Nazis arrested Vladek and Anja and deported them to Auschwitz .

The second part starts with a jump in time to 1986, while Art is experiencing writer’s block. He can only move on when he has to host his father. At that time, he had the chance to know what his father never told him. Namely, what he went through during the months in Auschwitz and Dachau . Vladek tells his story in a detached manner, from his sufferings to the end of the war, when he could finally find his wife and start a new life. The last panel shows Vladek and Anja’s gravestone: he died in 1982 before the comics were finished.

The author leaves out hyperbole, judgments or personal comments. Describing what happened is enough. Every narrative and graphic of Spiegelman’s choice is oriented to make Maus an analysis of war as a complex and dark period, where everything was uncertain and nothing safe.

An hybrid language from the melting pot

Maus uses a specific linguistic style. The language Spiegelman’s father speaks is the outcome of the USA’s melting pot. Jews living in New York developed a unique way of speaking: a hybrid language that can be heard in some Woody Allen movies, just as in The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel . Vladek’s English follows Polish grammar structures and contains words coming from Yiddish (spoken by Jews in the east of Europe). Some Yiddish terms became part of everyday American English, such as “ bagel ” or “ meshugga “; they create a language that contributes to cultural identification.

Vladek’s speech is confident in flashbacks, while it gets uncertain in the present, reflecting the distance from his home country. Since he had to leave, he feels his nation betrayed him. He doesn’t belong to Poland anymore, nor to the USA, where he feels like a stranger. So, his language reflects his sensation of estrangement in the present time. The language becomes a metaphor for his long journey to find a safe place without forgetting where he comes from. The title itself is a pun: “maus” means “mouse” in German, but it also recalls the German verb “ mauscheln ” which means “ speaking like a Jew “.

Spoken language is not the only element of postmodern art and literature in the comics. The frame scheme represents a solid meta-narrative element, given how it follows on from seeing how the comics develop in the author’s mind. The author blurs the line between present and past. Interruption in dialogues and jumps between the timelines make clear the chaos in his mind while listening to the story.

Spiegelman’s drawings as an analysis of the war

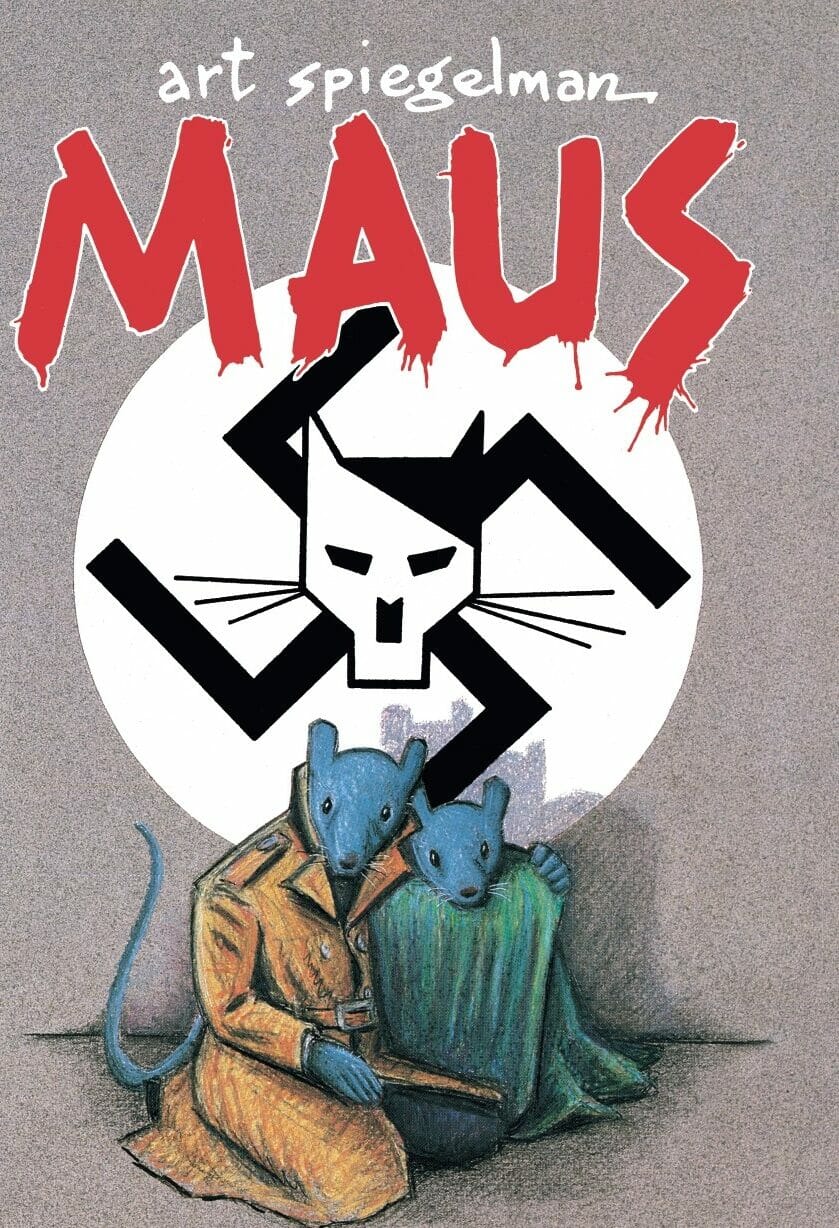

Spiegelman chooses various animals as metaphors of nationality. He represents Jews as mice, Germans as cats, Americans as dogs, Poles as pigs and French as frogs. Characters pretending to belong to other countries visibly wear a mask. The use of anthropomorphized animals in comics is nothing new in itself: both in children’s comics as Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse , and in underground comics for adults such as Robert Crumb’s Fritz the Cat . But those were just anthropomorphic animals, recalling the fairy tale tradition of beasts acting like humans. Spiegelman takes one step further, being the first illustrator using animals to show cultural differences. It’s the first device he uses to obtain emotional detachment, making identification difficult.

Spiegelman’s Maus is the first comic to talk about the Holocaust. Dealing with the concept and story of genocide, Spiegelman decided to let the story talk, putting himself in the background and showing more than telling. He eases as much as possible both the narrative and graphic style, growing apart from events. Page after page, panels are more and more neutral and stylized. Lines become rough and words seem screamed. The fragmented narration, dark sketches and a cold gaze on events create a historic reportage, that doesn’t even try to find an explanation or a sense, just expose. Matching history with its consequences in the present, Spiegelman’s Maus gives a strong and personal point of view on war.

Funding a genre

Maus was among the first book to be classified as a graphic novel , following the path was opened by Will Eisner ( The Spirit , A Contract with God ). It helped to strengthen the idea that comics can address several targets and discuss grown-up, serious subjects. Spiegelman wanted to create a more mature and underground style. Taking inspiration from Harold Grey ( Little Orphan Annie ) and Frans Masereel ( The City ), he contributed to comics’ recognition as artforms and not just entertainment, in opposition with superheroes’ comics.

Together with two DC Comics stories ( Watchmen and The Dark Knights Returns ), Maus contributed to changing the general perception of the comics. From that moment on, also thanks to independent publishers and a growing market, the comics industry was no longer dominated by Marvel and DC Comics and started to be something that could address not only kids, but also a vast audience of mature readers.

Lovingly Related Records

Watchmen | A subversion of the superhero

Posted on 16 July, 2020

The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel | It's comedy time

Posted on 23 September, 2021

The Man in the High Castle | “What have might been”

Posted on 01 July, 2021

Advertisement

Supported by

Art Spiegelman on Life With a ‘500-Pound Mouse Chasing Me’

Known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning comic book, “Maus,” the author has had a busy year, after the book was banned and jump-started a fresh debate about the sanitization of history. Frankly, he’s ready to get back to work.

- Share full article

By Alexandra Alter

On a recent afternoon, Art Spiegelman was sitting in the living room of his SoHo apartment, puffing on an e-cigarette that he wears around his neck, clipped to a pen holder so that he doesn’t misplace it. “I’m always losing things,” he explained.

He was feeling more disoriented than usual, having just returned home after several weeks on the road — a two-week road trip across the South with his son, Dash; a research excursion to a comics museum in Columbus, Ohio, for a new project; and a stop in Cincinnati to attend a memorial service for the cartoonist Justin Green, a close friend and mentor of his.

The whirlwind trip capped a momentous and chaotic year for Spiegelman, the iconic cartoonist, who was thrust into a national debate about censorship and rising antisemitism after a Tennessee school district banned his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel, “Maus,” from classrooms in January.

Since then, Spiegelman has been called upon again and again to champion and defend his work. He’s given countless interviews, speeches and webinars, including a Zoom meeting with residents of the Tennessee county where “Maus” was removed after parents objected to scattered instances of profanity and nudity in the text. He has argued repeatedly that the ban is about much more than “Maus,” which details his parents’ experience during the Holocaust, depicting Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. To Spiegelman, the decision to remove “Maus” from schools reflects a more insidious campaign to sanitize disturbing chapters of history, under the guise of “protecting” children.

“They want a kinder, gentler, fuzzier Holocaust,” he said.

Ironically, the ban has brought droves of new readers to his work and underscored its ongoing relevance, at a moment of heightened fear over a resurgence of antisemitism, fascism and white nationalist movements. “Maus” shot to the top of the best-seller list and sold 665,000 copies this year, more than triple its 2021 sales.

But the renewed attention has also been exhausting, and left him with little time or energy for his art, said Spiegelman, who never wanted to be a spokesman for Holocaust remembrance, and would rather be sketching in his notebook.

“It’s been a wild year,” he said, adding, “I’m done.”

Of course, Spiegelman is not unaccustomed to the spotlight. Fame has followed him ever since “Maus” won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992, becoming the first comic book to win the award, and transformed the medium, proving that comics can be a form of high art and literature. It sold six million copies in the United States, becoming a staple of school curriculums and a classic of Holocaust literature.

Still, this past year, Spiegelman has been in especially high demand. In November, the National Book Foundation awarded Spiegelman a medal for distinguished contribution to American letters. This fall, a new collection of essays and criticism about “Maus” and its enduring resonance, called “Maus Now,” was released by Pantheon. And to Spiegelman’s great delight, Pantheon just reissued a new edition of “Breakdowns,” an anthology of his early work, which was first published in 1978, and never received much attention outside of academic and hard-core cartoonist circles.

“There’s a small coterie of people who really read comics that know what I do,” Spiegelman said. “But for the most part, ‘Maus’ is like this giant skyscraper.”

The collected images, which feature his comics from the 1970s and later work from the 2000s, offer a glimpse of Spiegelman’s range as an illustrator and the breadth of his influences. The drawings include gag comics, a detective serial with a Cubist bent and some images that veer into hard-core pornography. The anthology also features intimate, emotional drawings that capture his devastation after his mother’s suicide, and reveal how he internalized his parents’ lingering trauma.

“This is where I found my own voice,” Spiegelman said of the work in “Breakdowns.” “I discovered territory that was genuinely mine.”

Close students and fans of Spiegelman’s work view “Breakdowns” as a sort of Rosetta Stone that offers a master key to his intricate and varied visual idiom, revealing his enormous and often overlooked range as an artist.

“On one level, it’s a deeply formalist book, showing how anti-narrative comics can be, with this avant-garde experimental language that Art is exploring,” said Hillary Chute, a professor of English, art and design at Northeastern University who edited “Maus Now” and has studied Spiegelman’s work for years. “It’s also incredibly personal.”

The reissue was already in the works well before the “Maus” ban, but the timing has proved fortuitous, said Lisa Lucas, Pantheon’s publisher.

“The reissue of ‘Breakdowns’ has coincided with a moment when the import of Art Spiegelman’s extraordinary career has become so deeply apparent to the culture,” Lucas wrote in an email. “Given the increased attention to his work and career, it’s exciting that so many new readers will learn about Art’s contributions to comix writ large.”

Spiegelman, 74, speaks softly and with precision, and has a reserved, professorial demeanor that can seem at odds with some of his transgressive early comics, which can be hypersexual or grotesquely morbid.

He reflected on his work and its legacy for nearly two hours on a recent frigid December afternoon, alternately sitting and pacing in the art- and book-filled apartment where he and his wife and creative collaborator, the New Yorker art editor Françoise Mouly, have lived since the mid 1970s. Back then, they had a printing press in their living room, where they put together editions of Raw, an eclectic, alternative comics magazine that published luminaries like Robert Crumb, Richard McGuire, Chris Ware and Justin Green , who was one of Spiegelman’s idols.

It was Green who showed him that “that confessional, autobiographical, intimate, unsayable material is perfectly fine content for comics,” Spiegelman said.

“It’s not just, ‘Make a joke,’ or, ‘Make a fantasy story,’” he continued. “This was like, ‘What’s going on in one’s brain, and how can you express it?’”

As a boy growing up in Queens, Spiegelman was haunted by the feeling that he shouldn’t exist, given his parents’ narrow escapes from the death camps, and found refuge in the subversive humor and wild art of Mad magazine and other comics. He began drawing early, prompted by doodling games he played with his mother, a playful side of her that he captures in “Breakdowns.” When he was just 13, he published a comic in a weekly Queens newspaper, which later hired him as a freelancer.

In 1966, he got a job at Topps Chewing Gum, designing stickers and novelty cards. The company subsidized his career for 20 years, giving him a steady income while he experimented with edgier and less commercial comics.

Spiegelman was shaped by the underground comic scene of the 1960s, and became a fixture in some of the era’s magazines, which peddled cartoons about drugs, sex and twisted genre stories. He arrived at a turning point in his career and life in the late ’60s, when he was hospitalized after a mental breakdown, got kicked out of college and was shattered by his mother’s suicide.

He became interested in mixing high and low art, and in pushing the boundaries of narrative in comics, exploring how time and space could be compressed or stretched in a series of images, and how interior experiences and memory could be illustrated on the page.

“For me to be able to bring the vocabulary of everything from Gertrude Stein and James Joyce to Picasso and other more formal aspects of picture-making, opened up very new territory,” Spiegelman said. “In order to do ‘Maus,’ everything I learned here became new vocabulary for me.”

In 1972, Spiegelman drew a three-page comic that later evolved into “Maus.” It opens with Spiegelman, as a young mouse, in bed as his father tucks him in and tells him the story of how he was captured in Poland by Nazis and sent to Auschwitz. Using animal faces in place of people gave him enough distance to tell the story. “For me, it was powerful just because it allowed me to deal with the material by putting a mask on people,” he said. “By reliving it microscopically, as best I could, moment by moment — it allowed me to at least come to grips with something that otherwise was only a dark shadow.”

Spiegelman worked on “Maus” for 13 years. It swelled to over 300 pages, and recounts the story of how his father and mother, Vladek and Anja, survived unimaginable horrors in a Nazi concentration camp, intertwined with the narrative of his own experience as a cartoonist, recording conversations with his father and aiming to capture the unspeakable in images. The first chapter was printed in 1980 in Raw, where it was serialized over the next decade.

When Spiegelman tried to find a publisher for a book version, the manuscript was widely rejected until Pantheon took it on. Spiegelman never imagined that it would become such a cultural and historical behemoth, or that decades later, it would become “cannon fodder in the culture wars,” as he put it.

“The only person I wanted to teach anything to was myself. I wanted to find out how I got born, when both my parents were supposed to be murdered before I could be conceived,” he said. “And so that was a complex project, to reconstruct for myself what that history was for them.”

“Maus” has long been a magnet for controversy. Critics took offense at the use of animal imagery to explore such a grave subject, and some said it was doubly offensive that Spiegelman drew Jews as mice, given that Nazi propaganda compared Jews to vermin — which was precisely Spiegelman’s point. It was banned in Russia because of the swastika image on the cover. When it was published in Poland in 2001, protesters, who were outraged that Spiegelman depicted Polish gentiles as pigs, burned copies of the book. In Germany, Spiegelman was asked by a reporter if a cartoon about Auschwitz was in bad taste. “No, I thought Auschwitz was in bad taste,” Spiegelman replied .

In the years since its release, Spiegelman has often felt oppressed by the scale of the book’s success, which has overshadowed all his other work. “Ever since ‘Maus ,’ I’ve been having to deal with a 500-pound mouse chasing me,” he said.

Spiegelman hopes that the revival of “Breakdowns” could introduce readers who only know “Maus” to a greater range of his work.

Looking back on the artist he was when he drew the works in “Breakdowns,” Spiegelman feels a mixture of affection and pride, for what he overcame and what he was able to create.

“I admire that guy,” he said with a smile. “Yeah. I was on fire.”

Alexandra Alter writes about publishing and the literary world. Before joining The Times in 2014, she covered books and culture for The Wall Street Journal. Prior to that, she reported on religion, and the occasional hurricane, for The Miami Herald. More about Alexandra Alter

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

John S. Jacobs was a fugitive, an abolitionist — and the brother of the canonical author Harriet Jacobs. Now, his own fierce autobiography has re-emerged .

Don DeLillo’s fascination with terrorism, cults and mass culture’s weirder turns has given his work a prophetic air. Here are his essential books .

Jenny Erpenbeck’s “ Kairos ,” a novel about a torrid love affair in the final years of East Germany, won the International Booker Prize , the renowned award for fiction translated into English.

Kevin Kwan, the author of “Crazy Rich Asians,” left Singapore’s opulent, status-obsessed, upper crust when he was 11. He’s still writing about it .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Guilt in “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman Research Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

An overview of events and characters concerning guilt, maus’ guilt, levels and causes of guilt, the therapeutic role of storytelling, works cited.

Survivor’s guilt is when a person feels guilty for surviving a life-threatening situation when others didn’t. Veterans are some of the people who face guilt and blame. Holocaust survivors, responders, and people who have experienced traumatic events, among others, also suffer from this type of guilt. The survivors tend to question why they survived an event, and others do not, asking themselves what they could have done to help the victims. Survivors’ guilt can be handled by connecting with others, including family and support groups, and accepting the feelings (De Leon 4). One may cope with guilt by processing the issue and allowing the mind to heal from the trauma. It can be accomplished using mindful techniques like breathing exercises during the flashbacks and practicing self-care like engaging in sports and taking long or short walks, among others. In Maus : A Survivor’s Tale , guilt is the main theme depicting how survivor’s guilt can be detrimental using the main character, Maus’, experiences following the Holocaust.

Maus details Spiegelman’s father’s story Vladek about his experiences as a Polish Jew during the Holocaust. The story runs parallel with the story of Spiegelman’s numerous interactions with his father during his visits to record his memories (Gavrilă 61). The characters in the comic are presented as animals used to highlight the author’s point of view. The dogs represent the Americans, the Cats stand for the Germans, and the Jews are depicted as mice (Gavrilă 61). Maus bases his story on the terrifying facts about the Holocaust, which saw the systematic genocide of millions of Jews that was carried out by the Nazi regime in World War II (Gavrilă 63). Maus represents the Second-generation literature about the Holocaust written from the perspective of the survivor’s children as told by their survivor’s parents (De Leon 10). It is a way for the children to connect with their family’s past, which is a Jewish tradition.

Guilt greatly consumes the victim’s life, but it is one way of learning from their and other people’s experiences. Spiegelman, through Maus, talks about his guilt for not suffering from the Holocaust like his parents and stepmother did (De Leon 5). He is guilty of the fact that his life is way better than theirs because by the time he grew up, the nightmare was over, and he wasn’t directly affected by the Holocaust (De Leon5). The guilt makes him feel disappointed, and through his experiences, a survivor’s tale is developed. In this case, Maus feels bad that he did not go through the Holocaust like his family members. He wishes he had joined in with the terror survivors. Using the character of Maus, Spiegelman shows how survival is highly-priced through the lens of his father’s experiences.

Maus talks about guilt and blame on two levels, the first being the individual part. In a personal case, the Holocaust victims try to come to terms with their guilt of surviving the ordeal when others died in camps. Maus, through the comic, explains the Holocaust through his father’s experience, and we see that it was not an easy place to come out because of the horrors and mistreatment in the concentration camps (De Leon 4). The people who went through the experience directly are guilty because they watched their loved ones, and they feel like the ones who died deserved to live more than them.

In life, some cultural artifacts and symbols are used to remind people of their duty to self and community. The concentration camps made it such that individuals had to think about their need to survive and their sense of responsibility to others (Gavrilă 63). This means that in the camp, it didn’t matter if it was your child/sister/ mother who was next on the line to die; the most important thing was an individual’s survival, which further demonstrates their guilt. Maus’ narration involves the character of Vladlek on a stationary bike (Spiegelman 11). The stationary bike symbolizes the impact of survivor’s guilt on an individual (Gavrilă 67). The person keeps trying to move forward, but the pain keeps pushing them back. Even though he survived the Holocaust, Vladlen is still guilty of the fact that other people did not survive like him.

In some cases, individuals may feel guilty as a group rather than individually. The second level of guilt, the collective one, is when the children of the holocaust victims feel guilty over not sharing their parent’s experiences (De Leon 13). This resembles Maus’ character, who had to question the reasons why the Holocaust had to happen, who, apart from the Nazis, were involved, and why the whole world couldn’t intervene to rescue the victims. The stories were passed down to them by their parents, making both of them get troubled by the same trauma (Gavrilă 69). The children felt angry about the situation, and some pushed for the survivors’ justice to get over the guilt. This is the reason why there are memorial days. The days are used to reflect on what happened during the Holocaust, and the people get to learn from others’ experiences to know what they would have done differently.

Spiegelman may have been born after the world war but is guilty of the fact that he was awakening the pain and digging into the wounds of his father, making him recount the pain of the Holocaust. He feels even guiltier because he will get to sell and make a profit from talking about the people’s pain, knowing that they won’t ever get justice and the Holocaust shouldn’t have happened (Spiegelman 33). Maus explains the Nazi ideology and consequences, which showed that they saw the Jews as sub-humans who were not worthy of ethical consideration. The Holocaust shows how weak ethics and morality are when truly tested and how bonds like friendship and family are broken. This is evident when one has to think about whether to consider the relationship they have with others or survive something like the Holocaust.

In the concentration camps, Vladlek gives Spiegelman a picture of how poor the conditions were. There was inhumane treatment with little food, and people were treated like objects of no value. The goal of victims like Valdek was to survive the Holocaust. That is why he accepted being drafted to go into different camps where life may not have been better, but he was treated differently in the concentration camp (Gavrilă 69). He was later released and managed to get his business back, but that did not mean that he could forget the people he lost in the camps.

Storytelling plays a therapeutic role in the lives of the victims. The holocaust victims, just like Spiegelman and Vladlek, were encouraged to talk about their experiences to help them heal. Talking about their experiences to the children not only connects their children with their past and makes them appreciate the struggles of the survivors but also aids in the push for justice and reconciliation. It allows the other generations to learn what to expect from fellow human beings and helps them strive to be better individuals (De Leon 9). These stories should be told by both the Nazi generation and the Jew generations to push for reconciliation. The surviving Holocaust victims need to be given a platform to speak about their experiences to expose the rot in the justice system and find answers for the ones who did not.

In conclusion, survivor’s guilt arises from surviving horrifying situations that would have almost led to death. These instances can occur at any time in a person’s life. The main challenge is in overcoming such feelings, especially when one feels separated from society in one way or another. Although some people may try to handle this guilt on their own, seeking support from caring individuals such as family and friends would help. Maus is a comical narration of a survivor who happens to be Spiegel man’s father. Maus is the main character affected by guilt resulting from his not participating in the Holocaust. His family members are considered to be survivors of what they endured, while Maus blames himself for not being present in the tribulations. Through this story, therapy for Holocaust victims can be realized.

De Leon, Danielle. “‘My Father Bleeds History’: Survivor’S Guilt and Filial Inadequacy in Art Spiegelman’S Maus : A Survivor’S Tale and E.L. Doctorow’S The Book of Daniel.” Wonderer , 2020. Web.

Gavrilă, Ana-Maria. “Holocaust Representation and Graphical Strangeness in Art Spiegelman’S Maus : A Survivor’S Tale: “Funny Animals,” Constellations, And Traumatic Memory.” Acta Universitatis Sapientiae Communicatio , vol 4, no. 1, 2017, pp. 61-75.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale . 1986.

- "Maus: A Survivor's Tale" a Novel by Art Spiegelman

- A Survivor’s Tale: "Maus" by Spiegelman

- Reasons Why the Jews Failed to Resist the Holocaust

- Analysis of “Who Invented the Jump Shot” Story by John Edgar Wideman

- Gary Soto’s “Afterlife” and Magical Realism

- Review of Slavery Topic in "Never Caught"

- The Role of Ezol’s Journal in Miko Kings: An Indian Baseball Story

- Alice Sebold’s Novel “The Lovely Bones”

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, December 17). Guilt in “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman. https://ivypanda.com/essays/guilt-in-maus-a-survivors-tale-by-art-spiegelman/

"Guilt in “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman." IvyPanda , 17 Dec. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/guilt-in-maus-a-survivors-tale-by-art-spiegelman/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Guilt in “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman'. 17 December.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Guilt in “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman." December 17, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/guilt-in-maus-a-survivors-tale-by-art-spiegelman/.

1. IvyPanda . "Guilt in “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman." December 17, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/guilt-in-maus-a-survivors-tale-by-art-spiegelman/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Guilt in “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman." December 17, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/guilt-in-maus-a-survivors-tale-by-art-spiegelman/.

Henri Bella Schaeffer and the Women of 1950s New York City

As a processing intern with the Archives of American Art, I organized donated collections into a standardized arrangement, to make them accessible to researchers. I personally think processing archivists have the best job in the field; we get to immerse ourselves in stories and shape how the materials which hold them will be understood. I get to see an artist’s process, from journaled ideas to preliminary sketches to exhibition. I get to read their most intimate self-reflections. I get to hold snapshots of their community.

Of the collections which I processed this past summer, my favorite was the papers of Henri Bella Schaeffer . Despite being a relatively obscure artist without—as of this writing—her own Wikipedia page, Schaeffer led an impressive life, both as an artist and a philanthropist. Born in 1908, she studied at the Académie André Lhote and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, and under the tutelage of muralist William A. Mackay. She would go on to become an admired postimpressionist painter, notably included in the International Women’s Salon and the Salon d'Automne.

Much of Schaeffer’s collection surrounds her dedication to the Artists Equity Association (AEA) , a national organization that, according to their constitution and by-laws , “formed to advance, foster, and promote the interests of those who work in the Fine Arts.” Schaeffer began this philanthropic commitment in 1950 as a member of the AEA New York Chapter’s Welfare Committee. She would advance steadily within the organization over the next decade, serving as a member of the National Welfare Committee from 1953 to 1959; director of the New York Chapter from 1954 to 1956; AEA director-at-large from 1956 to 1959; and AEA national secretary from 1961 to 1963.

The AEA formed its chapter-level and national welfare committees during a period of political change and American artistic redefinition; in New York City where Schaeffer worked, this change was embodied in the invention of Abstract Expressionism. Following the end of World War II and the uptick of the Cold War, the United States’ new status as a strong ally led many European Modernists to immigrate to New York City. Art historian Michael Leja argues that American artists in New York City were influenced by this imported Modernism, a broad genre that embraces experimentation, to create art that encapsulated individualistic reactions to America’s rising role as an imperialist force. The rise of this new artistic genre in combination with America’s increasing global influence lifted New York City as a new center of the art world scene, supported by a booming postwar economy and the Works Progress Administration’s recent federal legitimization of artistic careers.

Using the example of abstract expressionism, we can gain insight into how women artists fared in 1950s New York City. In her book, Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics , Ann Eden Gibson argues that Abstract Expressionism is remembered as a “triumph of the outsider,” a daring venture by artists to take their political messages from the margins to the global art scene. However, because Abstract Expressionism fundamentally relies on the personhood of the artist, those with societal advantages ironically became the dominant voices in a genre defined by its supposed marginalization. As Joan Marter notes in her essay “Missing in Action: Abstract Expressionist Women,” women abstract expressionists in New York City were largely excluded from the commercial art scene, limited in their participation within key artist clubs, and their portrayals of postwar existentialism were largely dismissed. With white women experiencing this level of discrimination, it is no surprise that artists of color saw even less recognition within the budding genre of abstract expressionism.

Due to professional dismissal, some women artists in 1950s New York City were desperate for work. As a member of the New York Chapter’s Welfare Committee, Schaeffer received many letters from women artists or the wives of artists, asking for financial and professional assistance. Common stressors included debt, medical access, and housing insecurity. The women writing to Schaeffer and the New York Welfare Committee expressed their lack the references and connections needed to apply for jobs and their desperation to support their families.

Schaeffer heard the pleas of these women and with the help of the New York Chapter Welfare Committee provided support in a variety of ways. Oftentimes this took the form of loans, to cover the rent and debts of recipients. When the situation was less immediate, the Committee connected women to job opportunities that could provide immediate cash. When a Mr. Loius Ferstad was sent to a sanitorium, the Welfare Committee covered the cost and, unable to find artistic employment on such short notice, set his wife up with “some typewriting work to do at home” to support their children in his absence. The Committee’s support always came with the expectation that its recipients would work hard to better their situations and would repay the AEA in time.

The Committee also supported women artists when the strain of poverty and personal losses to war became too much to bear. When Mrs. Dasha, the wife of a deceased veteran, wrote in requesting a same-day loan to purchase coal and clothes for her son, the Committee provided loans, artistic employment, and relocation assistance, hoping that the support would create “a possible incentive to her to try and help herself.” And when sculptor Irma Rothstein lived through a suicide attempt after losing her brother in World War II, the Committee covered her hospital bill, sold some of her artwork, and kept her company, as she had no family in the country. Schaeffer and the AEA stood with these women when they had no one else to which they could turn.

Henri Bella Schaeffer would continue to support artists through her other roles with the AEA, but her work with the New York Welfare Committee allowed her compassionate nature to directly reach women creatives in need. In the words of Schaeffer, “the right human relationship is … of utmost importance.” People like Henri Bella Schaeffer, a woman and an artist and an impactful philanthropist with a small digital footprint, are the reason I am training to be an archivist: to discover their stories, to place their legacies in the hands of others.

Emma Eubank is earning an M.A. in Public History at North Carolina State University and a M.S. in Library Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She interned with the Collections Processing department of the Archives of American Art in 2023.

Add new comment

- No HTML tags allowed.

- Web page addresses and email addresses turn into links automatically.

- Lines and paragraphs break automatically.

Get Involved

Internship, fellowship, and volunteer opportunities provide students and lifelong learners with the ability to contribute to the study and preservation of visual arts records in America .

Archives of American Art in the Smithsonian Transcription Center

You can help make digitized historical documents more findable and useful by transcribing their text .

Visit the Archives of American Art project page in the Smithsonian Transcription Center now.

Terra Foundation Center for Digital Collections

A virtual repository of a substantial cross-section of the Archives' most significant collections.

Visit the Terra Foundation Center for Digital Collections

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Scientists identify mechanism behind drug resistance in malaria parasite

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Peter Dedon

- Antimicrobial Resistance Interdisciplinary Research Group

- Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART)

- Department of Biological Engineering

Related Topics

- Drug resistance

- Antibiotics

- Biological engineering

- Drug development

- International initiatives

- Collaboration

Related Articles

Satellite-based method measures carbon in peat bogs

Newly discovered bacterial communication system aids antimicrobial resistance

SMART launches research group to advance AI, automation, and the future of work

A novel combination therapy counters antibiotic-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus infections

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

MIT Corporation elects 10 term members, two life members

Read full story →

Diane Hoskins ’79: How going off-track can lead new SA+P graduates to become integrators of ideas

Chancellor Melissa Nobles’ address to MIT’s undergraduate Class of 2024

Noubar Afeyan PhD ’87 gives new MIT graduates a special assignment

Commencement address by Noubar Afeyan PhD ’87

President Sally Kornbluth’s charge to the Class of 2024

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

(Capstone Paper) Maus by Art Spiegelman is an intersection of historic research and literary genres through an unusual mode making it worthy of canonization. ... ("Graphic Novel") and given Spiegelman had done field research, Spiegelman and Rowohlt publishing were allowed to keep the swastika on the cover (MetaMaus 155, 159). ...

Rosemary V. Hathaway Reading Art Spiegelman's Maus 251 arguing that "in an era when absolute truth claims are under assault, Spiegelman's Maus makes a case for an essentially reciprocal relationship between the truth of what happened and the truth of how it is remem - bered" (2000, 39). Young's description, while apt, still couches ...

The first, Art Spiegelman's 1984 comic book strip Maus, anthropomorphised Germans into cats and Jews into mice in order to narrate events experienced by Spiegelman's father, Vladek, during the ...

Art Spiegelman (born February 15, 1948, Stockholm, Sweden) is an American author and illustrator whose Holocaust narratives Maus I: A Survivor's Tale: My Father Bleeds History (1986) and Maus II: A Survivor's Tale: And Here My Troubles Began (1991) helped to establish comic storytelling as a sophisticated adult literary medium.. Spiegelman immigrated to the United States with his parents ...

In 1992, Art Spiegelman's two-volume illustrated work Maus: A Survivor's Tale was awarded a special-category Pulitzer Prize. In a comic book form, Spiegelman tells the gripping, heart-rending story of his father's experiences in the Holocaust. The book renders in stark clarity the trials Spiegelman's father endured as a Jewish refugee in the ghettos and concentration camps of Poland during ...

PDF | 1. Abstract Maus, the graphic novel by Art Spiegelman, depicts the author interviewing his father Vladek, a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor,... | Find, read and cite all the research you ...

Abstract: This bibliographic essay on Art Spiegelman's Maus: A Survivor's Tale serves as a broad survey of Maus criticism based on ten thematic categories such as trauma, postmemory, generational transmission, and the use of English. As much as this essay examines the wide range of scholarly interests surrounding Maus, it also highlights the problem of repetitive concentration on certain ...

BIANCULLI: Art Spiegelman speaking to Terry Gross in 1987. His graphic novel, "Maus," was published the year before, won the Pulitzer Prize and is now more than 35 years old. Yet very recently, it ...

Art Spiegelman: The Road To "Maus" This is the metadata section. Skip to content viewer section. ... Chapter Four," colored crayon on paper, ca. 1990. Date. November 10 - December 8, 1995 ... organization helping the academic community use digital technologies to preserve the scholarly record and to advance research and teaching in sustainable ...

This paper demonstrates how in his graphic novel In the Shadow of No Towers Art Spiegelman reads the events of 9/11 through the conceptual screen of the Holocaust. The questions that are raised in this connection concern the legitimacy of speaking about catastrophes, the stylistic means necessary to avoid sensationalism and kitsch, and finally the role of political commitment in the process of ...

In 1978 Art Spiegelman convinced his reluctant father, Vladek, to talk to him about his experience as a Polish Jew during the Second World War.What came out of it was a serial of comics about a life smashed up by the Holocaust. After nearly forty years, Spiegelman's Maus confirms itself to be a postmodern analysis of Word War II.. Later on, Pantheon Books published Maus in several volumes ...

Art Spiegelman on Life With a '500-Pound Mouse Chasing Me'. Known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning comic book, "Maus," the author has had a busy year, after the book was banned and jump ...

Dark Knight Returns, Spiegelman's Maus: A Surviour's Tale, Alan Moore and Davie Gibbon's Watchman (Wolk 8). However, along with Chris Ware, one of the best known contemporary graphic novelists, artists such as Art Spiegelman, Craig Thompson and Marjane Satrapi have introduced a highly personal style to their autobiographical graphic works.

Abstract. The purpose of this paper was to comment on the significance of "Maus" in the graphic novel. The genre as a whole was thrust into the limelight as Spiegelman's novel broke traditional ...

Itzhak Avraham ben Zeev Spiegelman (/ ˈ s p iː ɡ əl m ən / SPEE-gəl-mən; born February 15, 1948), professionally known as Art Spiegelman, is an American cartoonist, editor, and comics advocate best known for his graphic novel Maus.His work as co-editor on the comics magazines Arcade and Raw has been influential, and from 1992 he spent a decade as contributing artist for The New Yorker.

TOPIC: Research Paper on Art Spiegelman's Maus and the Literary Canon Assignment This is reminiscent of Dr. Kurt Spellmeyer of Rutgers University when, in his outstanding text, the New Humanities Reader, written with colleague Richard E. Miller, he shares his discovery that most college students do not know how to "connect" and that this is the ...

We will write a custom essay on your topic a custom Research Paper on Guilt in "Maus: A Survivor's Tale" by Art Spiegelman. 808 writers online . Learn More . An Overview of Events and Characters concerning Guilt. Maus details Spiegelman's father's story Vladek about his experiences as a Polish Jew during the Holocaust. The story runs ...

Art Spiegelman Research Paper; Art Spiegelman Research Paper. 451 Words 2 Pages. Art Spiegelman was born on February 15th, 1948 in Stockholm, Sweden. Both his parents were Polish Jews - Władysław (1906-1982) and Andzia (1912-1968) and were both born under Hebrew names; Zeev (William when he immigrated to the United States) and Hannah ...

Letter to Bert Warter from Lincoln Kirstein, 1953 July 14. H. Bella Schaeffer papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The AEA formed its chapter-level and national welfare committees during a period of political change and American artistic redefinition; in New York City where Schaeffer worked, this change was embodied in the invention of Abstract Expressionism. Following ...

Following last year's incredible success, we are thrilled to announce the NeurIPS 2024 Creative AI track. We invite research papers and artworks that showcase innovative approaches of artificial intelligence and machine learning in art, design, and creativity. Focused on the theme of Ambiguity, this year's track seeks to highlight the ...

In a paper titled "tRNA modification reprogramming contributes to artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum", published in the journal Nature Microbiology, researchers from SMART's Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) interdisciplinary research group documented their discovery: A change in a single tRNA, a small RNA molecule that is involved in translating genetic information from RNA to ...