- Member Login

Oral Health Topics

The Oral Health Topics section on ADA.org is intended to provide dentists with clinically relevant, evidence-based science behind the issues that may affect their patients and their practice. Refer to the Oral Health Topics for current scientific reviews of subjects that relate to oral health, from amalgam separators and antibiotic prophylaxis to xerostomia and X-rays.

Featured oral health topics

Learn which oral analgesics are used for the management of acute dental pain.

Understand Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) safety standards.

Learn about special considerations for pregnant patients and pregnant dental personnel .

Efficacy information about whitening treatments for extrinsic and intrinsic staining.

- Professionals

- Membership Benefits Overview

- Leadership Opportunities

- Dues Calculator

- Member Directory

- CE Smart Online Learning

- CE Smart Subscription

- ADHA Publications

- Become a Dental Hygienist

- Maintain Your Licensure

- Scholarships + Grants

- Professional Resources

- Student Resources

- National Board Review

- Professional Fellows Program

- Innovative Workforce Models

- Scope of Practice

- Advocacy Efforts

- License Portability

- ADHA24 Annual Conference

- Oral Cancer Awareness Month – April

- Student Proud Week ’24 Wrapped

- Oral Cancer Diagnostics Workshop

- Mental Health + The Dental Hygienist

- Philips|ADHA CE Seminars

- Heartland Dental Events

- IOH Foundation Happy Hour Series

- National Children’s Dental Health Month – February

- ADHA Awards & Winners

- National Dental Hygiene Month – October

- ADHA Celebrates 100

- Hygienist Hub

- CE Smart Course Catalog

- IOH Foundation

- Journal of Dental Hygiene

- My CE Smart

Thank You for Visiting ADHA

This content is for adha members only., to continue reading, please log in to your member account or join us and return to the site for full access.

Join adha today!

Already a member?

ADHA Member login

Related Links

- About CE Smart by ADHA

Research is critically important to achieving our mission to advance the art and science of dental hygiene. Facilitating the development of new clinical techniques, materials and treatments modalities, research also has an impact on access to care, education and public and private policies on oral health.

Both inside and outside of the research arena, it is important for practitioners to make decisions that are firmly grounded in knowledge obtained from research and clinical experiences. To help advance our profession, the National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda (NDHRA) identifies the following priority research areas:

- Health Promotion/Disease Prevention

- Health Services Research

- Professional Education and Development

- Clinical Dental Hygiene Care

- Occupational Health and Safety

View the National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda

Requests for Research and Research Support

The ADHA regularly conducts research studies on various important topics within or affecting the practice of dental hygiene and the ADHA membership. ADHA also receives many requests for research or research support. Please view the ADHA’s Policy on Requests for Research Support prior to soliciting support from ADHA for a research project. VIEW THE POLICY ON REQUESTS FOR RESEARCH SUPPORT

The Journal of Dental Hygiene

The Journal of Dental Hygiene (JDH) is the premier, peer-reviewed scientific research publication. In each issue, ADHA members will find articles to help them make evidence-based treatment decisions and so much more. The JDH’s Editorial Review Board (ERB) consists of nationally and internationally recognized content experts in the dental hygiene profession, as well experts from dentistry, physical therapy, nursing and public health. Published bi-monthly, archived articles are available for review, but only ADHA members and paid JDH subscribers have access to the last 12 months of JDH research and content.

Learn more about JDH

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Perspectives on dental health and oral hygiene practice from US adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft

Affiliation School of Dentistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis

Affiliation College of Literature, Science & the Arts, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States of America

Affiliation School of Dental Medicine, University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States of America, Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States of America

- Long Zhang,

- Marika Waselewski,

- Jack Nawrocki,

- Ian Williams,

- Margherita Fontana,

- Tammy Chang

- Published: January 19, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280533

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Adolescence is a critical time for adopting health behaviors which continue through adulthood. There is a lack of data regarding perspectives of US adolescents and young adults on their dental health and oral hygiene practice.

Adolescents and young adults, age 14–24, from MyVoice, a nationwide text message poll of youth. were asked five open-ended questions on the importance of dental health and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Responses were qualitatively analyzed using thematic analysis. Chi-square test was used to examine differences in experiences by demographics.

Of 1,148 participants, 932 responded to at least one question. The mean age was 19 years. Respondents were largely male (49.5%) and non-Hispanic white (62.4%). Most (92%) respondents perceived dental health as important or somewhat important and emphasized overall dental health and hygiene (38.6%) and aesthetics (18.3%). About half (49.2%) of respondents stated they have had at least one cavity since middle school. Just over half (54.8%) reported brushing and flossing to care for their dentition. 58% visited a dentist at least every 6 months, while 38% visited a dentist less frequently or not at all. Being non-cisgender, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and receipt of free or reduced lunch was associated with less frequent dental visits. 44% stated COVID-19 impacted their dental health, with many mentioning scheduling difficulties or worsened dental hygiene.

Conclusions

Most youth in our study consider dental health important, though their oral hygiene practice may not follow ADA guidelines and self-reported dental caries are high. Dental healthcare among youth has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic with interruption in regular dental visits and changes in hygiene habits. Re-engagement of adolescents and young adults by dental care providers via greater access to appointments and youth-centered messaging reinforcing hygiene recommendations may help youth improve dental health now and in the future.

Citation: Zhang L, Waselewski M, Nawrocki J, Williams I, Fontana M, Chang T (2023) Perspectives on dental health and oral hygiene practice from US adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 18(1): e0280533. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280533

Editor: Tanay Chaubal, International Medical University, MALAYSIA

Received: September 13, 2022; Accepted: December 29, 2022; Published: January 19, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Zhang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Our work uses data from MyVoice ( www.hearmyvoicenow.org ) a national text message survey of youth (ages 14-24). As part of our IRB approval and protections for this vulnerable population, we require Data Sharing Agreements to be executed with any individual or organization interested in accessing our data. Researchers interested in this data can contact the authors or the University of Michigan Medical School IRB ( [email protected] ) for more information.

Funding: TC received funding for this research from the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research and the University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Oral health is an essential part of the overall health and well-being of an individual. Dental caries (or tooth decay, which can result in painful cavities in teeth) in children remain the primary oral health challenge in the United States [ 1 ] and the world [ 2 ]. Untreated tooth decay can result in pain and infection, which may affect an individual’s eating, speaking, playing, and learning. Poor oral health in children is linked to school absence and worse academic performance [ 3 ].

Adolescents represent a unique and often overlooked group of children who experience many biological, developmental, and social transitions. Adolescence is a critical time of life for adopting health behaviors which continue through adulthood. According to the oral health surveillance report in 2011–2016 from CDC, more than half (57%) of adolescents aged 12–19 years experienced dental caries. One in six adolescents aged 12–19 years had untreated tooth decay [ 4 ]. There has been no detectable improvement in disease burden of dental caries in adolescents in the past two decades in the United States [ 5 ]. However, even though dental caries remains highly prevalent in adolescence, this period of life has been largely neglected in oral health research [ 5 ].

Previous studies attributed the high level of dental caries during adolescence to an increase in susceptible newly erupted permanent tooth surfaces, high carbohydrate dietary habits, independence to seek or avoid dental care, a low priority for oral hygiene, and additional social factors [ 6 ]. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) recommends fluoride, oral hygiene, diet management, and sealant placement as the primary prevention strategies to control dental caries in adolescents [ 6 ]. Yet the success of these preventive efforts depends on how adolescents perceive the importance of their dental health, maintain oral hygiene routine, and follow up with dental health care professionals. Also, in the context of COVID-19 pandemic, there is a lack of data regarding adolescents’ perspectives of impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their dental health.

The aim of our study was to understand the perspectives of a nationwide sample of adolescents and young adults regarding the importance of their dental health, experiences with dental caries, how they care for their dental health, how often they visit a dentist, and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on their dental health.

Data from five open-ended questions were obtained from the MyVoice cohort. MyVoice is an ongoing longitudinal nationwide text message poll that seeks to understand youth opinions on salient issues related to health and policy. Participants are a diverse sample of over 1,000 youth aged 14–24 years; details on study procedures have been previously described elsewhere [ 7 ]. Briefly, participants’ age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, census region of residence, and free lunch status were collected upon consent for the study. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board with online written consent completed by all participants and a waiver of parental consent for minors as the study was deemed minimal risk.

Questions were sent to 1,148 MyVoice participants on May 21, 2021 and were iteratively developed by a research team of youth, physicians, dentists, and mixed-methods research experts. Participants were sent the following five questions, which aimed to assess participants’ beliefs surrounding the importance of dental health and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their dental care experience:

- How important is dental health to you? Why?

- Since middle school, have you had any cavities? Tell us about it!

- What do you do to take care of your teeth?

- How often do you go to the dentist? What for?

- How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your dental health?

The survey responses were qualitatively analyzed using thematic analysis. A codebook was iteratively developed by the research team by first reviewing several hundred responses and identifying major concepts or codes. Codes were then defined with illustrative examples to complete the codebook for each question. Two independent researchers reviewed each question and applied codes to each response. Discrepancies between coders were identified and discussed to reach a consensus. Summary statistics were calculated using Microsoft Excel (2016). Chi-square test was used to analyze the difference of selected outcomes by demographics with SAS 9.4 software (Cary, NC, USA).

Of 1,148 participants, 932 responded to at least one question (response rate = 81.2%). The mean age of respondents was 19 years old (standard deviation: 2 years). Respondents were largely male (49.5%), non-Hispanic white (62.4%), had an education level of some college or technical school (41.0%), resided in the Midwest (32.3%), and did not receive free or reduced lunch (61.2%), a measure of low socioeconomic status ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280533.t001

Overall, 92.0% (852/926) considered dental health important or somewhat important to them. The most cited reasons why dental health is important included overall dental health and hygiene (38.6%) and aesthetics (18.3%). Participants who reported on the importance of overall dental health and hygiene noted “it’s important to have good dental hygiene”, they have “only one set permanent teeth”, and “we need our teeth to eat, bite, and talk.” ( Table 2 ). The proportion of people who perceived dental health important or somewhat important did not significantly vary by gender, race, or free or reduced lunch receipt ( Table 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280533.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280533.t003

In our sample, 49.2% (442/899) respondents reported having had at least one cavity since middle school. Among all respondents, 9.9% (89/899) specified having one cavity, 28.3% (254/899) reported multiple cavities, and 11.2% (101/899) reported an unspecified number of cavities. The percent of respondents who reported having had at least one cavity significantly varied by gender but did not vary by race or free or reduced lunch receipt. Among those who had tooth decay, 24.4% (108/442) said they received dental treatment for tooth decay. Some respondents attributed their cavity to poor oral hygiene (9.5%, 42/442), poor diet (6.3%, 28/442), a health condition or a genetic predisposition (6.1%, 27/442), not visiting a dentist (2.5%, 11/442) or not being able to afford visiting a dentist (1.8%, 8/442). Some respondents revealed that having a cavity caused pain (3.4%, 15/442) or led to an advanced dental treatment such as a crown, root canal treatment, or extraction (3.2%, 14/442).

Among the 883 who answered the question on how they take care of their teeth, 97.2% (858/883) reported brushing and 56.1% (495/883) reported flossing. Over half (54.8%; 484/883) noted that they both brush and floss to care for their teeth, though only 19.1% (169/883) described habits that specifically met the ADA guidelines of brushing twice daily and flossing daily. Other ways respondents reported caring for their teeth included using mouthwash (24.8%), visiting a dentist (10.8%), and avoiding damaging foods like high sugar items such as candies (5.5%).

Most youth (58.4%, 513/878) reported visiting a dentist every 6 months or more frequently, while some youth (37.6%, 330/878) went to a dentist less frequently than every 6 months. Of note, 10.4% (91/878) never visited a dentist for dental care. Common reasons for visiting a dentist included checkups (75.4%, 662/878), dental emergency (3.3%, 29/878), restoration (2.6%, 23/878), and orthodontics (2.3%, 20/878). There was a significant difference in the rate of respondents visiting a dentist every 6 months or more frequently based on gender, race, and status of receiving free or reduced lunch.

Regarding whether the COVID-19 pandemic affected respondent’s dental health, 56.5% (488/864) said the pandemic had no impact, and 43.5% (376/864) indicated an impact. The types of impact reported by youth included difficulty scheduling appointments (30.9%), worsened hygiene (7.2%), improved dental health (2.8%), safety (1.9%), and eating habits (1.0%).

A majority (92%) of adolescents and young adults surveyed, perceived dental health as important or somewhat important to them regardless of demographics, and many of them emphasized the importance of overall dental health and hygiene and aesthetics. This is consistent with a previous report that found adolescents considered dental appearance and oral self-care as important in terms of social interaction with peers, personal and career satisfaction, and future success in social and work life [ 8 ]. These positive beliefs in oral health among adolescents may be associated with better oral health outcomes. Broadbent et al found that individuals who held stable favorable dental beliefs from adolescence through adulthood had fewer tooth loss due to caries, less periodontal disease, better oral hygiene, and better self-rated oral health [ 9 ].

Despite having positive perspectives in oral health, our study participants (aged 14–24 years) revealed a high prevalence (49%) of self-reported dental caries since middle school, which is consistent with the CDC data that reported 57% prevalence of caries among adolescents aged 12–19 years [ 4 ]. This high prevalence of dental caries may be due to a host of factors that were not measured in our study including, the rate of caries experienced during early childhood, increased exposure to cariogenic bacteria, high frequency of sugar consumption, inadequate salivary composition or flow, delayed or insufficient fluoride exposure, and poor oral hygiene [ 10 , 11 ]. Adolescent’s positive beliefs in oral health are also subject to change and the stability of dental health beliefs, rather than a snapshot, may be more predictive of self-reported oral health outcomes [ 9 ].

Females and those who identify as “other” gender also reported a statistically significant higher rate of having cavities than male respondents. But there was no significant difference of the rate of having cavities by race and receipt of free or reduced lunch (a proxy for socioeconomic status). It is known that socioeconomic factors such as race and household income level contribute to the disparity of dental caries in U.S. adolescents [ 4 ]. The reason why our study did not show the same pattern could result from a different definition of outcome, sampling method, and study period. The lack of associations between self-reported dental caries and socioeconomic status in our study warrants further investigation.

The way in which adolescents and young adults cared for their teeth included brushing, flossing, mouthwash, visiting a dentist, and avoiding damaging food. Interestingly, nearly all (97%) of participants reported brushing their teeth as a routine oral hygiene practice; however, only 56% reported flossing to care for their teeth, and 19% specifically reported following ADA guidelines of brushing twice a day and flossing once a day [ 12 ]. The difference between brushing and flossing could reflect a difference in perception of importance of each practice. A study examined the stability of oral health related beliefs including using dental floss at ages 15, 18, and 26 years, and found that 49% of adolescents thought flossing was not important at least once at the three ages [ 9 ]. This might explain why our study population favored brushing over flossing. A systematic review and meta-analysis has shown the benefits of flossing in addition to toothbrushing in reducing gingivitis compared to toothbrushing alone, though it lacks evidence of its effect in preventing dental caries [ 13 ]. The clinical benefits of flossing in preventing gum disease may help to formulate dental health messages to adolescents from a perspective of both cosmetic and health reasons [ 14 ].

Slightly more than half of adolescents and young adults in our study reported visiting a dentist every six months or more frequently, while 38% visited a dentist less frequently or not at all. This supports previous national statistics of dental visits by adolescents in the United States, which found that 64.9% of adults 18 and older visited a dentist in the past year [ 15 ]. The frequency of dental visits varies based on individual needs [ 16 ], though fewer dental visits could indicate limited resources or limited access to dental care. Our data showed that respondents that self-identified as non-Hispanic black or Hispanic and people who received free or reduced lunch were less likely to visit a dentist in a recommended schedule compared to their counterparts. Also, our study showed that about 10% of youth reported no dental visit at all, which could be due to barriers preventing adolescents from seeking dental care such as access to dental insurance, financial limitation, lack of adequate transportation, and social support. Infrequent or inadequate number of dental visits may contribute to a possible knowledge gap in maintaining oral health. For example, though the respondents commonly mentioned brushing to care for their teeth, it was rare for them to discuss the benefits of fluoride toothpaste, which plays an important role in preventing dental caries [ 17 ]. Also, some participants mentioned using mouthwash, whitening strips, and retainer to care for their teeth, which are more aesthetics driven than health driven. Access to dental health professionals and proper oral hygiene education may be an area for improvement in adolescents.

A total 44% of our surveyed population stated that COVID-19 had an impact on their dental health. Those who were affected by COVID-19 often reported scheduling conflicts and worsened dental hygiene. The responses to the COVID-19 impact in our adolescent and young adult samples shed a light on the psychosocial aspects of oral health in adolescence. For instance, one respondent said “We haven’t gone to the dentist in a while. Also I got really depressed and it was hard to brush regularly”. Another responded “Being at home all the time makes me forget to brush my teeth sometimes since I don’t have as structured of a routine and don’t have to for social reasons as often”. Social interactions among adolescents were largely affected by COVID-19 pandemic and it may be linked with less ideal oral hygiene practice in this group, given the self-reported importance of dental aesthetics in this population.

This study has several strengths including a high response rate as well as detailed qualitative data that allowed a nuanced assessment of the rationale behind participants behaviors. The information obtained can help shape public health messaging campaigns and further inform and shape dental practitioners’ approach in educating the youth about proper dental hygiene.

This study also has limitations. Participants represent a large nationwide sample of youth that opted in to a text messaging poll. However the sample is not nationally representative, which limits the generalizeability of our findings. The responses were also taken in May 2021, a very dynamic time where thoughts and opinions of COVID-19 in responses may change from the start of the pandemic to today. MyVoice is an open-ended poll designed to be only 5 questions to minimize burden on our youth participants, though this limits our ability to probe more deeply into the experiences of youth.

In summary, our study demonstrated that majority of adolescents and young adults perceived dental health to be important or somewhat important, though their oral hygiene practice may not follow ADA guidelines and the burden of self-reported dental caries is high. The COVID-19 pandemic affected adolescent’s ability to schedule a dental visit and might affect their oral hygiene practice in a socially isolated environment. Gender, race, and status of receiving free or reduced lunch were associated with less frequent dental visits. Re-engagement of adolescents and young adults in dental care by dental care providers via greater access to appointments and youth-centered messaging that reinforces hygiene recommendations may help youth achieve improved dental health now and in the future.

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children’s Oral Health [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/basics/childrens-oral-health/index.html . Accessed May 1, 2022

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dental Caries in Permanent Teeth of Children and Adolescents [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/OHSR-2019-dental-caries-permanent-teeth.html . Accessed March 22, 2022.

- 5. National Institutes of Health. Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, 2021.

- 6. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Adolescent oral health care. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2021:267–76.

- 12. American Dental Association (ADA) Division of Science. Keeping your gums healthy[Internet]. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; Available from: https://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(15)00245-7/fulltext#relatedArticles . Accessed May 5, 2022.

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral and Dental Health [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/dental.htm . Accessed March 22, 2022

- 16. American Dental Association (ADA). Your Top 9 Questions About Going to the Dentist—Answered![Internet]. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association (ADA). Available from: https://www.mouthhealthy.org/en/dental-care-concerns/questions-about-going-to-the-dentist/ . Accessed March 9, 2022.

Skip to content

Support the College of Dental Medicine

Community outreach.

Learn more about the College of Dental Medicine's community outreach programs.

Postdoctoral and Residency Programs

dds program.

Half of our graduates go directly into specialty training upon completion of the DDS degree.

Research Areas

Patient care, columbiadoctors dentistry, become a student.

Learn more about the admissions process and how you can apply.

Student Research Projects

- Live CE Event – June 1, 2024

- Self-Study CE Courses

- Live Event CE Certificates

- Dental Quizzes

- Dental Hygiene

Dental Research

- Patient Care

- Life at Work

- Infection Control

- Students & New Grads

- Ask Kara RDH

- Curiosity Killed the Plaque

- Videos & Hygiene Chats

- Hygiene Chats: Kara & Emily

- Hygienist Spotlight

- Today’s RDH Honor Awards

- Submissions

- June 1st Live CE Event

- Featured posts

- Most popular

- 7 days popular

- By review score

Research Finds Potential Association Between Oral Bacteria and High Blood Pressure

Researchers Find the Mechanism Behind Potential Anticancer Properties in Lidocaine

Oral Microbiome and Diet: Researchers Analyze DNA From Ancient “Chewing Gum”

Researchers Use Saliva Analysis to Help Diagnose Pain in Patients with Dementia

Research Reveals an Association Between Primary Teeth Biorhythm and Adolescent Weight Gain

Research Explores How Dietary Choices Affect the Oral Microbiome in Postmenopausal Women

The Mystery of Tooth Enamel Defects: A New Autoimmune Disorder Discovered

Research Suggests Association with Oral Infections and Metabolic Profiles

Researchers Find that Viking Age Dentistry Was Probably More Sophisticated than Previously Thought

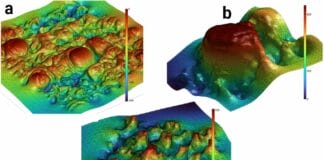

Research Using AI and 3D Imaging Unveils Unique Terrain of Individual Tongue Surfaces

Research Explores Innovative Tissue Regeneration for Endodontic Diseases With Potential Beyond Dentistry

Research Explores the Association Between Immune System’s Memory, Inflammatory Systemic Conditions, and Periodontitis

Systematic Review Analyzes the Association Between Daily Toothbrushing and Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia

Ancient Dental Calculus Reveals an Oral Microbiome Shift after the Black Death

Research Examines the Association Between Periodontal Care and Acute Myocardial Infarction Hospitalization

Research Finds a High Abundance of Previously Unknown Antibiotic-resistant Genes in Bacteria

Research Examines Fluoridated Water’s Impact on Child Emotional and Behavioral Development and Executive Functioning

Longitudinal Look at Tooth Loss and Cognitive Decline among Older Adults

Dental Health Improvement and Its Effects on Dentists’ and Hygienists’ Demand

Research Looks into the Unnecessary Prescribing of Antibiotics Among Dentists

Trending now.

4 Simple Tips for Newly Graduated Dental Hygienists

Does Referring to Appointments as a “Cleaning” Undervalue Dental Hygienists and Treatment Provided?

Caviar Tongue: Are Dental Hygiene Patients Displaying Signs of “Aging?”

Curiosity Killed the Plaque Ep. 20: Dangers of Oral Clay Products

- Dental Hygiene 593

- Patient Care 319

- Dental Research 263

- Hygiene Chats & Videos 139

- Life at Work 121

- Healthy Smiles, Healthy Practices 86

- Students & New Grads 56

- COVID-19 53

- Hygienist Spotlight 48

Most Recent

A Hygienist’s Game Plan to Conquer Dental Conference Exhibit Halls

Instrument Sharpening by the RDH: The How and Why

Don't Miss

QUIZ: Test Your COVID-19 Infection Control Knowledge

Hygiene Treatment CDT Code Breakdown and Patient Explanations

VIDEO: Hygiene Chat – Ensuring CDC Compliance when Using New Products

Research on Drug Suggests Future Possibilities as a Periodontal Antibiotic

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Dent J (Basel)

Broadening the Dental Hygiene Students’ Perspectives on the Oral Health Professionals: A Text Mining Analysis

Yukiko nagatani.

1 Department of Dental Hygiene, University of Shizuoka Junior College, 2-2-1 Oshika, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka-shi 422-8021, Japan

Rintaro Imafuku

2 Medical Education Development Center, Gifu University, 1-1 Yanagido, Gifu 501-1194, Japan

Yukie Nakai

Associated data.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Professional identity formation, an important component of education, is influenced by participation, social relationships, and culture in communities of practice. As a preliminary investigation of dental hygienists’ professional identity formation, this study examined changes in the dental hygiene students’ perceptions of oral health professionals over the three years of their undergraduate program. At a Japanese dental hygiene school, 40 students participated in surveys with open-ended questions about professional groups several times during their studies. The text data were analyzed through content analysis with text mining software. The themes that characterized their dental hygienist profession perceptions in their programs each year were identified as: “Supporters at the dental clinic”; “Engagement with interprofessional care” and “Improved problem-solving skills for clinical issues regarding the oral region”; and “Active contribution to general health” and “Recognition of the roles considering relationships” (in the first, second, and third years, respectively). The students acquired professional knowledge and recognized the significance and roles of oral health professionals in practice. They gained more learning experiences in their education, including clinical placements and interprofessional education. This study provides insight into curriculum development for professional identity formation in dental hygiene students.

1. Introduction

Dental hygienists specialize in the control of dental diseases; this profession is prevalent and generally professionally licensed in over 30 countries [ 1 , 2 ]. They are primarily responsible for preventive procedures and non-surgical periodontal treatments. Their role is usually to investigate dental diseases, and motivate and instruct patients about dental health [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. In Japan’s aging society, the necessity of implementing oral health management as primary care is becoming widely recognized by health professionals and the public. It is essential for dental hygienists to prevent and treat dental diseases and support general health by maintaining and promoting the oral environment [ 4 ], and improve the quality of life [ 5 ]. To respond to these social needs, it is necessary to secede from the emphasis on manual procedures in dental clinics [ 6 ] and practice as directed by the dentists; to train the dental hygienists with high qualities and professional skills who can think and practice on their own in the community in cooperation with multiple professionals; and to establish a way of the dental hygiene work that is adapted to the aging society [ 7 ]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a deep understanding of one’s professional role and expertise, in addition to the roles of the other professionals with whom they work, considering social needs. Moreover, the internalization of this value system promotes the identity formation of a learner who practices in the health profession.

Identity formation is “the process by which an individual self-defines as a member of that profession based on the acquisition of the requisite knowledge, skills, attitudes, values and behaviors” [ 8 ]. It is considered an important component of education in the health profession. In identity formation in health professions, social interactions, experiences, and learning contexts are influential factors. At the collective level, it is influenced by context, including culture and the learning environment chosen by the learner. According to Wenger, gaining practical experience through active engagement and interactions with other members of a community is essential to professional identity formation [ 9 ].

In health profession education, the learners’ profound transformation occurs through learning experiences, most notably the clinical ones [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. To make the transition from a layperson to a professional, they need learning opportunities that encourage a re-identification of the past (or the present) self [ 13 ]. Furthermore, building social relationships with peers and mentors in clinical education, as well as reflecting and discussing about learning experiences in clinical settings, strengthens professional identity formation through socialization with professional groups [ 14 , 15 ]. Therefore, the health profession education programs need to be structured stepwise from the first year to enable the development of values and professional identity regarding evidence-based practice and professionalism [ 16 ].

The importance of introducing education and support that promotes professional identity formation in dental hygiene education has been internationally recognized. For example, service-learning exercises and curriculum revisions have been implemented to develop students’ attitudes and sense of professional responsibility [ 17 , 18 ]. In addition, Imafuku et al. explored the interprofessional identity formation in dental hygienists [ 19 ]. However, the overall understanding of the process of dental hygienists’ professional identity formation over time, beginning with their first year of study, remains unclear. Clarifying the process of dental hygienists’ professional identity formation could provide insight into students’ actual perceptions of the nature, tasks, and value system of the profession. Analyzing the discrepancy between their perceptions of the profession of dental hygienist and the learning outcomes expected by their teachers would provide a basis for improving and developing new educational strategies and learning support methods in the future. Therefore, in this study, as a preliminary investigation of dental hygienists’ professional identity formation, we examined the changes in their perceptions of the dental hygienist profession during the three years of their undergraduate education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. participants.

An observational, longitudinal, and prospective study was conducted in the Department of Dental Hygiene at the University of Shizuoka Junior College. All freshmen in the cohort who enrolled in the school in 2019 were invited to participate in this study, and all consented ( n = 40). They were 18–19 years old at the time of enrollment. Their background prior to enrollment was high school or post-high school graduates preparing for university entrance exams. In addition, none of them had clinical experience in the medical field.

2.2. Data Collection

An open-ended questionnaire was self-administered to 40 students each year for three years, from the second half of their first year to the second half of their third year. The open-ended format allowed the researchers to elicit richer data on students’ perceptions of the professional roles and prospects as health professionals at each stage of their undergraduate education. Specifically, this questionnaire survey was structured by five open-ended questions about their reasons for choosing the profession, their ideal future image as a dental professional, their perceptions of professionalism in dental hygiene, societal expectations, and competencies required for the profession. The actual questions in the survey are as listed below:

- - Why did you decide to become a dental hygienist?

- - What kind of dental hygienist do you want to be?

- - What do you think is the professionalism of dental hygienists?

- - What do you think is required of you as dental health professionals by society and patients?

- - What competencies do you think that dental hygienists need to have for clinical practice?

The data were gathered in October 2019 (at the beginning of the first year’s second semester), October 2020 (at the beginning of the second year’s second semester), and November 2021 (at the end of the clinical practice).

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were transcribed from questionnaires and then subjected to text mining analysis using the software, KH Coder 3 (Koichi Higuchi, Kyoto, Japan) [ 20 ]. The software produced a list of words according to their frequencies and interrelationships. It is a quantitative process of adapting algorithms to discover hidden, useful, and interesting patterns in unstructured qualitative text data [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. In analyzing the qualitative text data, text mining increases the reliability and validity of the coding [ 23 ]. In addition, it can be used in conjunction with human coding content analysis to enhance the rigor [ 24 ].

In this study, the software was used for the research participants’ perceptions of the dental hygienist profession to obtain an overall picture of the diversity, type, and distribution as a framework for understanding the data before conceptualization. A hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted on the pupils’ perceptions of the oral health professionals at each of the three data collection points; moreover, frequently occurring words were extracted. Subsequently, the co-occurrence of the strength of the association between the extracted words was calculated using the Jaccard coefficient. In these analyses, the Key Word in Content (KWIC) concordance function was used to identify words with three or more occurrences to qualitatively examine students’ interpretations of their perceptions of the dental hygienist and how they changed over time. The resulting associations were visually represented on a Co-Occurrence Network Map and coded and categorized by the first and second authors to increase rigor and explore the meaning of the data in conjunction with the qualitative analysis. The authors discussed and identified underlying themes in the visualization of the results. Preliminary results were then discussed and a consensus was reached by all members of the research team. The chi-square test was applied to assess the significance of differences in the distribution of students’ perceptions of oral health professionals at each of the three data collection points using KH Coder, version 3 (Koichi Higuchi, Kyoto, Japan). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

In addition, the relationship between the results of each period and the content of the curriculum taken up to that point, as well as a comparison of the data at the end of the third-year field training with the diploma, were also examined.

2.4. Study Context

This study was conducted at the Department of Dental Hygiene, Junior College of the University of Shizuoka, involving students enrolled in a three-year education program. Regarding the educational philosophy, this school follows the diploma policy, which entails the student learning outcome objectives and graduation approval/degree awarding program; it is set to train dental hygienists who can respond to the oral health needs of the community. A junior college bachelor’s degree is awarded to those who have studied in an educational program to acquire the abilities listed below and have earned the necessary credits.

- - Professional knowledge, abilities, and communication skills related to dental hygiene

- - Logical thinking and problem-solving skills

- - Awareness of their roles and responsibilities as dental hygiene practitioners and the ability to perform them appropriately

- - A rich sense of humanity and high ethical standards, and ability to collaborate and cooperate with other professionals

- - Contribution to the development of people’s health and a striving for lifelong learning.

In the training school included in this study, the curriculum was designed to enable students to achieve the above-mentioned diploma. As shown in Figure 1 , in the first year, students attend lectures on liberal arts, basic specialties, and dental hygiene. In the second year, they opt for specialized clinical subjects, on-campus training related to dental hygiene work, and subjects related to interpersonal support and well-being in collaboration with students from other departments. In addition, elective subjects related to health and medical well-being have been established from the second semester of the first year to the first semester of the second year. After studying these subjects, the third year includes off-campus practical training in dental clinics, oral surgery departments of general hospitals, nursing homes, and disability support facilities.

Three-year curriculum of dental hygiene at the research site. (The intensity of the color indicates the volume of the subject’s content.)

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the University of Shizuoka Research Ethics Committee [approval number 1-19]. Furthermore, informed consent was provided by all the study participants.

3.1. Changes in the Word Frequency

Overall, 333 statements were related to the professional role and attitude of dental hygiene, of which 120, 177, and 192 statements were categorized for the first, second, and third years, respectively. The following five words were found to occur over 30 times in total:

- Oral: 90 times

- Patient: 64 times

- Dental: 62 times

- Health: 51 times

- Knowledge: 35 times

3.2. Number of Code Occurrences

The occurrence rate of the aforementioned words varied from year to year ( Figure 2 ). In the first year, “oral” was the most frequently appearing word, followed by “prevention”, “dental”, “health”, “knowledge”, and “patient”; in the second year, “oral” was the most frequently occurring word, similar to the first year, followed by “patient”, “dental”, “health”, “whole body”, and “knowledge”. The increased utilization of the words “patient” and “whole body” was characteristic. The former occurred 12, 24, and 28 times in the first, second, and third years of school, respectively, and the number of occurrences tended to increase as the school year progressed. In the third year, “oral” was the most frequently used word, followed by “patient”, “dental”, “health”, “do”, and “knowledge”, similar to the first and second years. Although “do” did not occur in the first year, it showed an increasing trend with 5 and 13 occurrences in the second and third years, respectively. However, the number of occurrences of “prevention” tended to decrease with increasing grade level, from 16 to 8 and 6 times in the first, second, and third years, respectively.

The number of the extracted words of expertise perceived by the dental hygiene students over time.

3.3. Code Occurrence Rate

Figure 3 visualized the changes in the occurrence rate of the specialty codes as perceived by the dental hygiene students over time. The square size indicates the occurrence rate of each code (showing “percent”), and its color corresponds to the standardized residuals (Pearson residuals). Therefore, a larger square represents a higher rate of occurrence, and the darker color represents the larger residual. According to Figure 3 , only “do”, which did not appear in the first year, showed a significant difference in the proportion of the occurrence of the three points ( p < 0.05, Chi-square test).

Changes in the occurrence of the specialty codes as perceived by the dental hygiene students.

3.4. Recognition of Professional Roles, Competence, and Attitude at the Three Time Points Based on the Strength of the Relationship between the Words

From the co-occurrence network model diagram showing the strength of the association between the words with three or more occurrences, the characteristic themes were extracted for the dental hygiene students’ perceptions of their professional roles, competence, and attitude at each of the three time points, using the KWIC concordance function to assess the word usage.

3.4.1. At the Beginning of the First Year’s Second Semester

During the first year, the following two themes were extracted ( Figure 4 ):

The co-occurrence network diagram of the first-year dental hygienists’ perceptions of professional role and competencies.

Supporters at the Dental Clinic

The dental hygienists were identified as assistants in the dental clinic, professionals who help patients improve their health by providing expert knowledge and skillful care in the prevention and treatment of dental caries, alleviating their fear of treatment, and supporting the dentists during the dental treatment.

- - “How to comfort the patients at the dental clinic, a place where they are considered to be uncomfortable”.

- - “Supporting the dental treatment to run smoothly”.

Understanding the Relationship between Oral and General Health

The participants were aware that the oral region and the whole body are deeply related; however, as professionals in oral health, they believed that they must enhance their knowledge, treatment, instruction, and care techniques for “improving the health of the whole body through oral care”.

- - “Understanding better than anyone else that the teeth and oral health are linked to general health”.

- - “Dental caries prevention and understanding the relationship between the oral region and the whole body”.

- - “The ability to communicate the importance of oral health in various settings, both in the medical and educational fields”.

3.4.2. At the Beginning of the Second Year’s Second Semester

During the second year, the following four themes were extracted: ( Figure 5 ).

The co-occurrence network diagram of the second-year dental hygienists’ perceptions of professional role and competencies.

Dental Hygienists’ Work Frames

Participants recognized the framework of the three main tasks of a dental hygienist in Japan, including caries prevention treatment through fluoride application, assistance work for smooth dental treatment by standing between patients and dentists, and oral health instruction.

- - “Must be able to assist in the dental treatment, provide the oral health instruction, and perform the caries prevention procedures”.

- - “A person who can stand between the dentist and the patient and contribute to enhanced treatment”.

Engagement with Interprofessional Care

The participants felt they must have a broad knowledge of medicine, not only regarding oral health, which is their profession, but also systemic diseases. They aimed to confidently collaborate and communicate with multiple professionals and develop the ability to handle interprofessional medicine that could provide patient-centered care.

- - “To acquire an awareness of the whole body, not just the oral, and to be able to perform team medicine with other professionals”.

- - “Have a patient-centered attitude and the communication skills to practice in a team-based environment”.

Health Support from the Perspective of the Oral Health

The need for dental hygienists to acquire medical information along with oral health knowledge in order to demonstrate support for general health from the perspective of oral health has been recognized. These skills help prevent infection and improve general health and quality of life by helping to maintain and promote oral health throughout life, including the perioperative period and old age.

- - “To improve the quality of life as well as the oral health of patients”.

- - “Promoting and maintaining general health through the oral health”.

Improved Problem-Solving Skills for Clinical Issues Regarding the Oral Region

The participants were aware of their role in solving and improving oral problems. Therefore, participants recognized the need for the ability to provide medical care, including instruction, care, and hygiene management, to identify and resolve issues based on each person’s condition status and needs, and to build a relationship of trust with the patient.

- - “Perceive the patients’ condition, their oral health situation, understand their problems, and provide them with appropriate care to resolve those issues”.

- - “I think it is about improving oral health, instructing about oral health, and building trusting relationships to solve oral health problems”.

3.4.3. At the End of the Third-Year Clinical Practice

At the end of the third-year clinical practice, the following four themes were identified: ( Figure 6 ).

The co-occurrence network diagram of the dental hygienists’ perceptions of professional role and competencies in the third year.

Active Contribution to General Health

Participants mentioned the need for evidence-based and correct professional knowledge and skills, as well as the ability to make decisions in clinical practice. They recognized that acquiring these competencies would enable them to respond to patient complaints and work smoothly with multiple health care professionals from an oral health perspective.

- - “Dental as well as medical knowledge and working with various professionals to approach problems”.

- - “As a dental hygienist, we must have the knowledge to answer patient complaints”.

Recognition of the Roles Considering Relationships

As professionals supporting patients’ autonomous oral health care, they recognized their role in improving self-care and providing professional care based on their relationship with patients; they were able to incorporate specific preventive approaches such as dietary instructions and periodontal treatments. In addition, they recognized their role based on their clinical relationship with the dentist, which included managing the patients overall health during treatment and paying attention to the intentions and feelings of both the patient and the dentist.

- - “We are professionals in terms of prevention; thus, hygienists are required to provide care and prevention so that we do not get to the treatment stage”.

- - “To support the patients’ feelings (chief complaint) and to help them feel comfortable through the dentist”.

Protecting the Oral and Overall Health

The students expressed their intention to be actively involved in the whole health management not limited to oral health care, such as supporting the daily quality of life from a holistic perspective.

- - “Improvement of the overall health and quality of life through oral health”.

- - “To enhance the quality of life by improving and maintaining oral health that is closely related to the everyday life, such as eating, speaking and laughing”.

Intervention in the Life Context

In the approach to oral health maintenance and promotion, participants recognized the need to not only understand the oral and general condition of patients, but also to actively incorporate their oral function and hygiene into their daily lives by intervening in their life background, such as their diet and lifestyle.

- - “To be able to provide health instruction from a dental perspective, including dietary instruction and lifestyle modification”.

- - “To provide instruction for the patients’ own oral health self-care, so that they themselves can maintain a good oral health”.

4. Discussion

This study found that dental hygiene students’ perceptions were strongly influenced and shaped by their learning experiences during college. This included lectures on their specific duties, the interdisciplinary education program, and clinical placements in dental facilities. As previous studies have shown, it is critical that they gain a clear understanding of the core values, expectations, and behaviors of the profession during health professions education and are encouraged to develop their own identities in addition to acquiring knowledge and skills [ 14 , 25 ]. Accordingly, the present longitudinal research demonstrated four aspects of changing the perceptions of the oral health professional among dental hygiene students.

The first aspect is the relationship between knowledge acquisition and professionalism. The establishment of a knowledge system in a professional domain has a significant impact on identity formation [ 26 , 27 ]. Moreover, self-efficacy has been related to professional recognition, skill mastery, and knowledge [ 28 ]. In this research, the first-year students were expected to acquire knowledge related to the “oral and general health promotion” such as “dental caries prevention and understanding the relationship between the oral region and the whole body” and “the teeth and oral health are linked to general health”. In the second year, the concept of the “dental hygienists’ work frames” learned in lectures such as “assist in the dental treatment, provide the oral health instruction, and perform the caries prevention procedures”, was often mentioned as a competence of dental hygienists. Specifically, in the first and second years, their professionality was frequently viewed from the aspect of knowledge acquisition reflected in the content of the specialized clinical courses. Knowledge acquisition is also essential in forming the professional identity foundation [ 26 ]. Nevertheless, in the first and second years, the students tended to focus excessively on obtaining the expertise of a dental hygienist. As it is said that identity formation is facilitated by active engagement and interaction in the community [ 9 ], therefore, education programs that promote the pupils’ understanding of “Recognition of the roles considering relationships”, such as communication training, interprofessional education, and early exposure program need to be developed and incorporated into the basic education stage. For example, early exposure is an educational strategy to help students adapt to the clinical environment, improve their skills of reflection and evaluation, and establish their professional identity [ 29 , 30 , 31 ].

Regarding knowledge acquisition, enhancing logical thinking and problem-solving skills are key for curriculum development. Specifically, it is important to incorporate research and exploratory activities into each subject area step-by-step in dental hygiene education. These skills are necessary to apply the acquired knowledge in practice. In medical education, undergraduate research courses in which pupils independently conduct research for a certain time have been offered; further, efforts to improve their logical thinking and evidence-based medicine have been reported [ 32 , 33 ]. Similarly, in the three years of dental hygiene education, it is necessary to promote a continuum of learning through exploratory activities about assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation to develop logical thinking and problem-solving skills for evidence-based medical practice [ 34 ]. Therefore, educational objectives and content should be jointly determined by the clinical practice organization and the educational institution, and research activities should be integrated into the curriculum.

The second aspect is the students’ broadened perceptions of their professional roles and responsibilities, which influence professional identity formation [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]. Thus, this study indicated the changes in the pupils’ perceptions of the role and responsibilities of a dental hygienist. Specifically, the first-year students limited the place of work to the “dental clinic” and viewed dental hygienists as professionals involved in the dental care there; further, there was a limited term or phrase indicating a professional role of caring for people at different life stages, such as oral function management in the elderly and perioperative oral care. In the second year, the pupils acquired the perspective of the “patient” and the theme of supporting patient health from the oral health perspective was extracted. In the third year, the theme of protecting the patient’s overall health as a role of a dental hygienist was obtained. These results suggested that health is not limited to the oral region but is also considered from the standpoint of the whole body and that the students had been taking more initiative in “protecting” the patient’s health. Furthermore, the vague image of the role of a dental hygienist in the first year was transformed into a more concrete image and gained a more generalist view. They were able to think about the clinical issues from a patient’s standpoint in the third year. Their text data included “improving and maintaining oral health that is closely related to everyday life, such as eating, speaking and laughing”, and the “improvement of the overall health and quality of life through oral health”. This result is consistent with that of the study by Imafuku et al., that explored the identity formation processes of dental hygienists in the field as interprofessional collaborators [ 19 ]; however, the significance of this research is that it showed that such a change in perception might be occurring among the undergraduate students.

In dental hygienist education, for example, it is essential to provide opportunities for the students to reaffirm professional values and beliefs, including what kind of a dental hygienist they want to become, and to clarify their vision for the future in their education’s early stage. In clinical education, dental hygienists and other professionals can assume specific roles within the community of practice through collaborative practice. To encourage group-level socialization, opportunities to meet role models who are active in various situations [ 8 , 38 ] and internships in a community of practice can be used. It is also important to incorporate into the curriculum supportive methods that internalize the values of the dental hygienist during these social experiences [ 8 , 25 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]

The third aspect is a change in perception from individual to team care. Over three years, this study’s participants modified their perceptions of the dental hygienist’s professional role and responsibilities from a focus on the “individual” as a specialist involved in the dental treatment to an “interpersonal” or “team” perspective, such as interprofessional collaboration and patient communication. In the first year, many of the texts referred to their skills, such as “dental caries prevention and understanding the relationship between the oral region and the whole body” and “the ability to communicate the importance of oral health in various settings, both in the medical and educational fields”. Similarly, in the second year, there were several statements about their skills; however, the concepts related to the professions in which they work with the people they care for, such as “provide them with appropriate care to resolve these issues” and “have a patient-centered attitude and the communication skills to practice in a team-based environment”, were more common. During this time, students are believed to have gained a deeper understanding of the relationship between oral and general health, as well as a perspective on the importance of the dental hygienist’s intervention to a person’s general health through the study of specialized clinical subjects. In addition, learning about welfare, management, and clinical psychology, planning dental health instruction, and experiencing being in the role of a patient during campus clinical training may have fostered an awareness of the need for interprofessional collaboration, the ability to provide interpersonal support, and the responsibility to solve health problems. In the third year, students interacted with patients and dental hygienists in clinical practice. They noted the relationships between patients and medical staff, patients and dental hygienists, and dental hygienists and various professionals. Students mentioned the need for clarification of the relationship and their own roles between dental hygienists and multidisciplinary professionals, the ability to respond to patient complaints, the ability to make judgments that allow active participation in multidisciplinary care confidently, and scientifically sound clinical skills.

This finding corroborates the results of previous studies, which show that students focus more on enhancing teamwork and collaborative practice, and their identity confidence is increased after interprofessional education programs [ 41 , 42 ]. However, this study did not confirm the pupils’ improved collective learning skills, such as consensus-building and leadership, and the relationships between their interprofessional learning experience and quality care provision, as suggested by Cooper and Imafuku [ 41 , 42 ]. A possible factor influencing this is that during their clinical practice at the university, the pupils themselves had limited opportunities to experience interprofessional collaborative practice with professionals other than dentists.

Regarding interprofessional collaboration, most clinical practice hours were spent in private dental clinics, presumably because there were not enough opportunities to experience situations of interprofessional collaboration with other professionals. During the five-day oral surgery clinical practicum in the general hospital, students did not proactively practice interprofessional collaboration due to the severity of patients’ illnesses, systemic management issues, and limited skills; it is assumed that they only observed the instructor and had difficulty recognizing interprofessional collaboration. Furthermore, there is a strong perception that they are employees who perform their duties under the instruction of the Dental Hygienists Act, which states that “dental hygienists are those whose work is to perform the following acts under the instruction of dentists and preventive measures for diseases of the teeth and oral” [ 43 ]. Annan-Coultas indicated that observations of real-life teamwork environments can be a meaningful way to teach interprofessional teamwork concepts [ 44 ]. Similarly, although it is difficult for pupils to practice interprofessional teamwork on high-risk patients in a clinical setting, it may be useful for them to observe a multidisciplinary conference and how dental hygienists practice collaborative medicine in such a situation to deepen their awareness of interprofessional collaboration.

Finally, analysis of the textual data suggests that dental hygiene students have a stronger sense of ownership as health care providers. It suggests that participation in the clinical placements strengthened students’ professional identity and sense of responsibility. Specifically, text analysis in the third year showed that the verbs “to do” and “to protect”, which indicate proactive action in terms of professional role and responsibility, were frequently described. This change may be primarily due to their insertion into the dental clinic community during their field training and gaining experience in clinical practice, albeit in a peripheral role, while building relationships with the dentists and dental hygienists in the dental clinic. Students’ identities are formed not only by their associations with professional networks, but also by their actual experiences and participation in the community [ 9 ].

The increased sense of ownership is related to student’s attitude toward lifelong learning. Thus, further educational support is needed from the first-year education to continuously enhance their awareness of the importance of self-learning in healthcare. Lifelong learning is an integral part of the communities of practice, with time and expectations for reflection [ 45 ]. Encouraging pupils to reflect on their experiences in clinical placements deeply can enhance their awareness of lifelong learning and cultivate their self-learning skills. Some studies in medical education show that medical students’ identities are promoted in relationships through reflective activities and the need to provide educational spaces for them to understand their identity as a doctor by recounting their clinical experiences [ 14 , 46 , 47 ].

In this study, we conducted a content analysis of an open-ended questionnaire related to the role and competencies of oral health professionals in dental hygiene students. The results of this study have implications for society as a whole, particularly in the areas of dental education and health care. However, the questionnaire survey did not reflect the background of the students’ descriptions, what they could not express, and the depth of their insight. In particular, we did not explore the kind of individuality and specific experiences from which their perceptions emerged, how they perceived their experiences, and what kind of identity they formed in the narrative process. In addition, although we related the changes in students’ perceptions to the curriculum, we were unable to examine the influence of extracurricular factors, such as extracurricular activities and prior learning experiences. As the data in this study were compiled and compared across all participants at the three time points, changes in individual perceptions over time could not be tracked and the effects of individual personalities and environments could not be analyzed. Therefore, further qualitative interview studies are needed to more fully incorporate students’ experiences behind their perceptions of professionals and to shed light on professional identity formation among dental hygienists.

5. Conclusions

The dental hygiene students in this study acquired professional knowledge, became aware of the importance and role of oral health professionals in practice, and broadened their perspectives as dental hygienists through their health care education, which included lectures, clinical placements, and interprofessional education. Therefore, this study provides insight into the development of curricula to promote the professional identity of dental hygiene students.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the dental hygiene students who participated in this study.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the research grant of the University of Shizuoka and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP22K17279.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; methodology, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I; software, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani); validation, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani), R.I. and Y.N. (Yukie Nakai); formal analysis, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; investigation, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; resources, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; data curation, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and Y.N. (Yukie Nakai); writing—original draft preparation, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; writing—review and editing, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; visualization, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; supervision, Y.N. (Yukie Nakai); project administration, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani); funding acquisition, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the national and institutional ethical standards. The ethical approval for the study protocol was obtained from the Human Institutional and Regional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee, the University of Shizuoka Research Ethics Committee [approval number 1-19].

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Advanced search

Advanced Search

National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda

- Figures & Data

- Info & Metrics

- Introduction

A profession involves the acquisition of knowledge and skills in a unique area through formal training. A discipline is a branch of knowledge studied and expanded through higher education and research, while a profession consists of persons educated in the discipline according to nationally regulated, defined and monitored standards. 1 The regulation of a profession and establishment of clinical standards are important aspects of the social contract between a profession and the society it serves.

The American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA) acknowledges the importance of a body of research unique to dental hygiene in defining it as a profession and developing it into a discipline. The aim of the dental hygiene research agenda is to provide a framework to guide those members of the profession who desire to add to the body of knowledge that defines the dental hygiene profession. In recognition of the importance of relevancy of the NDHRA to the dental hygiene profession, ADHA is committed to the ongoing updating of the NDHRA as the dental hygiene body of knowledge expands

ADHA defines the discipline of dental hygiene as the art and science of preventive oral health care including the management of behaviors to prevent oral disease and promote health. 2 The ADHA research agenda proposes to continue to develop and add to the body of knowledge that defines the profession. As research builds the discipline of dental hygiene, the profession demonstrates its value to society through the provision of service and care, and ultimately, improved oral health.

Historically, dental hygiene has drawn in part on other disciplines, such as the disciplines of periodontics and public health, for the evidence used to support its own practice and education. The generation of scientific knowledge and utilization of an interdisciplinary approach to knowledge benefits the profession through shared initiatives and perspectives. The goal of increasing dental hygienists' participation in research is to grow beyond reliance on research originating from other disciplines and, instead, build upon existing research so the knowledge base can emerge from within dental hygiene itself. 3 To this end, the framework of the dental hygiene research agenda directs dental hygiene researchers to contribute knowledge that is unique to dental hygiene. The 5 primary objectives that were the basis for the creation of the National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda still remain applicable today: 4

To give visibility to research activities that enhance the profession's ability to promote the health and well-being of the public;

To enhance research collaboration among members of the dental hygiene community and other professional communities;

To communicate research priorities to legislative and policy-making bodies;

To stimulate progress toward meeting national health objectives; and

To translate the outcomes of basic science and applied research into theoretical frameworks to form the basis for dental hygiene education and practice.

The updated research agenda visually illustrates how the areas of dental hygiene research move through discovery, testing and translation into education and practice. Discovery is the phase of research where ideas are generated, testing is where concepts and interventions are implemented and outcomes are generated and evaluated, and translation disseminates findings to the profession and to the scientific community at large.

Translational research aims to “translate” findings from basic science research into interprofessional medical, nursing and dental practice for improving health outcomes. Decisions for practice or subsequent research are based on all phases: discovery, testing and translation. For example, the discovery phase of research might document barriers, while the testing phase considers assessing interventions and improving application of science to practice. Within the translation level of research, the process of translating or moving findings from research into practice is examined. It verifies that the application of these findings results in improved health for clients and populations. Research hypothesis need to be tested and then applied (translated) in real life settings with outcomes measured and assessed.

Using the three phases of research changes the way we conceptualize the dental hygiene research agenda from a linear design with a list of objectives to a visual display showing the inter-relationship existing between the phases of research and themes or areas of research. The new visual display was designed recognizing that all research is interconnected and multifactorial, while also recognizing that results can influence future need for additional research.

- Perspectives on the ADHA Research Agenda

Dental hygiene and research have been linked since the early 1900s. In 1914, Dr. Fones' 5-year study in public schools demonstrated that dental hygienists can positively impact oral disease using education and preventive methods. 5 Dental hygienists today are increasingly becoming involved in research at all levels and are helping to provide data that will impact the profession for years to come.

The first ADHA National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda (NDHRA) was developed in 1993 by the ADHA Council on Research and adopted by the ADHA House of Delegates in 1994. 4 A Delphi study was used to establish consensus and focus the research topics for the agenda. 6 This was the first step to guide research efforts that support the ADHA strategic plan and goals. A research agenda provides direction for the development of a unique body of knowledge that is the foundation of any health care discipline and, as such, should be used to drive the activities of the profession.

In 2001, the Council on Research revised the agenda to reflect a changing environment based on two national reports: The Surgeon General's Report on Oral Health and Healthy People 2010. Input from the 2000 National Dental Hygiene Research Conference sponsored by ADHA was considered in the revision. The revised document was released in October 2001 and prioritized the key areas of research. 7

In 2007, the agenda was revised to reflect current research priorities aimed at meeting national health objectives and to systematically advance dental hygiene's unique body of knowledge. These revisions were based on a Delphi study that was conducted to gain consensus on research priorities. 8