Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Service Improvement Project

Paper completed for my Nursing degree dissertation. It discusses the implementation of a patients DNACPR status and its identification on a patients wristband. The text follows a hypothetical project to implement the service improvement within an NHS trust; including research, stakeholder engagement and change implementation at a ward level.

Related Papers

Health technology assessment (Winchester, England)

Matthew Breckons

Byung Cheol Lee

Healthcare information systems (e.g., Bar Code Medication Administration (BCMA) system), have been adopted to deliver efficient healthcare services recently. However, though it is seem-ingly simple to use (scanning barcodes before medication), users of the BCMA system (e.g., nurses and pharmacists) often show non-compliance behaviors. Therefore, the goal of this study is to comprehensively understand why such non-compliance behaviors occur with BCMA system. Though comprehensive literature review, we identified 128 instances of causes, which were cate-gorized into the five categories: Poor Visual and Audio Interface, Poor Physical Ergonomic De-sign, Poor Information Integrity, Abnormal Situation for System Use, and User Reluctance and Negligence. The results show that successful use of a BCMA system requires supportive systems and environments, so it is more like an issue of the system, rather than that of an individual user or a device. We believe that the proposed categories could be applicable in investigating non-compliance behaviors in other healthcare information systems as well.

Michelle L Rogers

International Journal of Evidence-based Healthcare

Anesthesia and analgesia

imran bhatti

Difficult airway cases can quickly become emergencies, increasing the risk of life-threatening complications or death. Emergency airway management outside the operating room is particularly challenging. We developed a quality improvement program-the Difficult Airway Response Team (DART)-to improve emergency airway management outside the operating room. DART was implemented by a team of anesthesiologists, otolaryngologists, trauma surgeons, emergency medicine physicians, and risk managers in 2005 at The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. The DART program had 3 core components: operations, safety, and education. The operations component focused on developing a multidisciplinary difficult airway response team, standardizing the emergency response process, and deploying difficult airway equipment carts throughout the hospital. The safety component focused on real-time monitoring of DART activations and learning from past DART events to continuously improve system-level perfo...

Journal of Evaluation in …

Nick Sevdalis

Graham Cookson

Transfusion

Charles Vincent

Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

Pierangelo Bonini

RELATED PAPERS

Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety / Joint Commission Resources

Etienne Phipps

Cognition, Technology & Work

Emily Patterson

Anesthesiology clinics

Edward R Mariano

BMJ Quality & Safety

Transfusion Medicine

Martha Bruce

Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association

Damian Roland , Alesia Hunt

Andrei Rosin

Claire Goodman , Alison While , Vari M Drennan

Clinics in laboratory medicine

David Novis

Dilek Gümüş

International Journal of Nursing Studies

Laurence Moseley

Tibert Verhagen , Matthijs Noordzij

Implementation Science

Mike English

The practising midwife

Declan Devane

Journal of Advanced Nursing

Robert Crouch

Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences

Kjell Grankvist

Kerm Henriksen , Emily Patterson

Quality in primary care

Charles Campion-smith , Peter Wilcock

Alan Tennant

Adam Jowett

Lisa Sharrock , Suzanne K Molesworth

Andrew Booth

Archives of Pathology Laboratory Medicine

peter beresford

BMC Health Services Research

Ivaylo Vassilev , Evridiki Patelarou , christina foss

Amangaly Akanov

Manual Therapy

Janine Leach

Patrick Bolton

Health Service Journal

Omid Shabestari

International Journal of Medical Informatics

Osman Sayan

Panagiotis Siaperas

wendy jessiman

Dr Paul Barach

Irish Journal of Medical Science

Catriona Murphy

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Baillie L, Bromley B, Walker M, Jones R, Mhlanga F Implementing service improvement projects within pre-registration nursing education: A multi-method case study evaluation. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014; 14:(1)62-68 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.06.006

Bahn D Social Learning Theory: its application in the context of nurse education. Nurse Educ Today. 2001; 21:(2)110-117 https://doi.org/10.1054/nedt.2000.0522

Bandura A Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977; 84:(2)191-215 https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura A Self-efficacy: the exercise of control.New York: WH Freeman; 1997

Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. 2002. https://tinyurl.com/glm79u4 (accessed 27 May 2020)

Batalden PB, Davidoff F What is ‘quality improvement’ and how can it transform healthcare?. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007; 16:(1)2-3 https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2006.022046

Baumeister RF, Leary MR The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995; 117:(3)497-529 https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Benner P From novice to expert. Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice.Menlo Park (CA): Addison-Wesley; 1984

Carlin A, Duffy K Newly qualified staff's perceptions of senior charge nurse roles. Nurs Manage. 2013; 20:(7)24-30 https://doi.org/10.7748/nm2013.11.20.7.24.e1142

Chang E, Hancock K Role stress and role ambiguity in new nursing graduates in Australia. Nurs Health Sci. 2003; 5:(2)155-163 https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00147.x

Chesser-Smyth PA, Long T Understanding the influences on self-confidence among first-year undergraduate nursing students in Ireland. J Adv Nurs. 2013; 69:(1)145-157 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06001.x

Christiansen A, Robson L, Griffith-Evans C Creating an improvement culture for enhanced patient safety: service improvement learning in pre-registration education. J Nurs Manag. 2010; 18:(7)782-788 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01114.x

Coventry TH, Maslin-Prothero SE, Smith G Organizational impact of nurse supply and workload on nurses continuing professional development opportunities: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs. 2015; 71:(12)2715-2727 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12724

Craig L Service improvement in health care: a literature review. Br J Nurs. 2018; 27:(15)893-896 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2018.27.15.893

Davis L, Taylor H, Reyes H Lifelong learning in nursing: A Delphi study. Nurse Educ Today. 2014; 34:(3)441-445 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.04.014

Dinmohammadi M, Peyrovi H, Mehrdad N Concept analysis of professional socialization in nursing. Nurs Forum. 2013; 48:(1)26-34 https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12006

Draucker BC The critique of Heideggerian hermeneutic nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 1999; 30:(2)360-373 https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01091.x

Duchscher JB A process of becoming: the stages of new nursing graduate professional role transition. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2008; 39:(10)441-450 https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20081001-03

Duchscher JEB Transition shock: the initial stage of role adaptation for newly graduated Registered Nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2009; 65:(5)1103-1113 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04898.x

Feng RF, Tsai YF Socialisation of new graduate nurses to practising nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2012; 21:(13-14)2064-2071 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03992.x

Fretwell JE Ward teaching and learning.London: Royal College of Nursing; 1982

Gadamer H-G Truth and method, 2nd edn. London: Sheed and Ward; 1979

Gignac-Caille AM, Oermann MH Student and faculty perceptions of effective clinical instructors in ADN programs. J Nurs Educ. 2001; 40:(8)347-353

Gollop R, Whitby E, Buchanan D, Ketley D Influencing sceptical staff to become supporters of service improvement: a qualitative study of doctors' and managers' views. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004; 13:(2)108-114 https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2003.007450

Gray M, Smith LN The professional socialization of diploma of higher education in nursing students (Project 2000): a longitudinal qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 1999; 29:(3)639-647 https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00932.x

Gray PD, Thomas D Critical analysis of ‘culture’ in nursing literature: implications for nursing education in the United States. In: Oermann MH, Heinrich KT (eds). NewYork (NY): Springer Publishing Company; 2005

Guba EG, Lincoln YS Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds.). Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1994

Hatlevik IKR The theory-practice relationship: reflective skills and theoretical knowledge as key factors in bridging the gap between theory and practice in initial nursing education. J Adv Nurs. 2012; 68:(4)868-877 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05789.x

Houghton CE ‘Newcomer adaptation’: a lens through which to understand how nursing students fit in with the real world of practice. J Clin Nurs. 2014; 23:(15-16)2367-2375 https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12451

Huybrecht S, Loeckx W, Quaeyhaegens Y, De Tobel D, Mistiaen W Mentoring in nursing education: perceived characteristics of mentors and the consequences of mentorship. Nurse Educ Today. 2011; 31:(3)274-278 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.022

Jackson D, Firtko A, Edenborough M Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2007; 60:(1)1-9 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x

James B, Beattie M, Shepherd A, Armstrong L, Wilkinson J Time, fear and transformation: student nurses' experiences of doing a practicum (quality improvement project) in practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016; 19:70-78 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.05.004

Johnson N., Penny J., Robinson D., Cooke M. W., Fowler-Davis S., Janes G., Lister S. Introducing service improvement to the initial training of clinical staff Retrieved 05.04.2012, 2012. 2010; https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2007.024984

Lindseth A, Norberg A A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004; 18:(2)145-153 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00258.x

Machin AI, Jones D Interprofessional service improvement learning and patient safety: A content analysis of pre-registration students' assessments. Nurse Educ Today. 2014; 34:(2)218-224 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.06.022

Mackintosh C Caring: The socialisation of pre-registration student nurses: A longitudinal qualitative descriptive study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006; 43:(8)953-962 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.11.006

Madden MA Empowering nurses at the bedside: what is the benefit?. Aust Crit Care. 2007; 20:(2)49-52 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2007.02.002

Maben J, Latter S, Clark JM The theory–practice gap: impact of professional–bureaucratic work conflict on newly-qualified nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2006; 55:(4)465-477 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03939.x

Maslow AH Toward a psychology of being.Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 1998

McGowan B Who do they think they are? Undergraduate perceptions of the definition of supernumerary status and how it works in practice. J Clin Nurs. 2006; 15:(9)1099-1105 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01478.x

NHS Improvement. Patient Safety Measurement Unit. 2017. https://tinyurl.com/y8pagbwq

NHS website. High impact actions for nursing and midwifery—the essential collection. 2010. https://tinyurl.com/yawpgcjy

NHS website. Releasing time to care, the NHS Productive Series. 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/productives

Future nurse: Standards of proficiency for registered nurses.London: NMC; 2018

Ogier M An ‘ideal’ sister—seven years on. Nurs Times. 1986; 82:(5)54-57

Ó Lúanaigh P Becoming a professional: what is the influence of registered nurses on nursing students' learning in the clinical environment?. Nurse Educ Pract. 2015; 15:(6)450-456 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2015.04.005

Orton H Ward learning climate: a study of the role of the ward sister in relation to student nurse learning on the ward.London: Royal College of Nursing; 1981

Potter J Representing reality: discourse, rhetoric and social construction.London: Sage; 1996

Potter P, Perry A Fundamentals of nursing, 5th edn. St Louis (Mo): Elsevier; 2001

Robson C Real world research, 3rd edn. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 2011

Salmon J The use of phenomenology in nursing research. Nurse Res. 2012; 19:(3)4-5 https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.19.3.4.s2

Schoessler M, Waldo M The first 18 months in practice: a developmental transition model for the newly graduated nurse. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development (JNSD). 2006; 22:(2)47-52 https://doi.org/10.1097/00124645-200603000-00001

Shafer L, Aziz MG Shaping a unit's culture through effective nurse-led quality improvement. Medsurg nursing. 2013; 22:(4)229-236

Smith N, Lister S Turning students' ideas into service improvements. Learning Disability Practice. 2011; 14:(2)12-16 https://doi.org/10.7748/ldp2011.03.14.2.12.c8377

Smith J, Pearson L, Adams J Incorporating a service improvement project into an undergraduate nursing programme: a pilot study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2014; 20:(6)623-628 https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12217

Standing M A new critical framework for applying hermeneutic phenomenology. Nurse Res. 2009; 16:(4)20-30 https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2009.07.16.4.20.c7158

Strouse SM, Nickerson CJ Professional culture brokers: nursing faculty perceptions of nursing culture and their role in student formation. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016; 18:10-15 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.02.008

Thomas LJ, Revell SH Resilience in nursing students: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2016; 36:457-462 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.10.016

van Manen M Researching lived experience. Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy.New York (NY): State University of New York Press; 1990

Welsh I, Swann C Partners in learning. A guide to support and assessment in nurse education.Cornwall: Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd; 2002

Wilcock P, Carr E Improving teaching about improving practice. Qual Saf Health Care. 2001; 10:(4)201-202 https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.0100201w

Developing and sustaining nurses' service improvement capability: a phenomenological study

Subject Lead, Adult Nursing, and Senior Lecturer, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne

View articles

Alison Machin

Professor of Nursing and Interprofessional Education, Northumbria University/Executive Member (workforce), Council of Deans of Health

View articles · Email Alison

Background:

Service improvement to enhance care quality is a key nursing responsibility and developing sustainable skills and knowledge to become confident, capable service improvement practitioners is important for nurses in order to continually improve practice. How this happens is an under-researched area.

A hermeneutic, longitudinal study in Northern England aimed to better understand the service improvement lived experiences of participants as they progressed from undergraduate adult nursing students to registrants.

Twenty year 3 student adult nurses were purposively selected to participate in individual semi-structured interviews just prior to graduation and up to 12 months post-registration. Hermeneutic circle data analysis were used.

Themes identified were service improvement learning in nursing; socialisation in nursing practice; power and powerlessness in the clinical setting; and overcoming service improvement challenges. At the end of the study, participants developed seven positive adaptive behaviours to support their service improvement practice and the ‘model of self-efficacy in service improvement enablement’ was developed.

Conclusion:

This study provides a model to enable student and registered nurses to develop and sustain service improvement capability.

Embedding a nursing service improvement culture has been a focus of successive UK policy initiatives ( Craig, 2018 ), such as the NHS Safety Thermometers scheme ( NHS Improvement, 2017 ), the 2012 nurse-led quality framework Energise for Excellence, High Impact Actions for Nursing and Midwifery ( NHS website, 2010 ) and the NHS Productive Series ( NHS website, 2020 ). However, information about how nurses develop and sustain service improvement skills beyond their initial education is lacking.

Service improvement can be defined as ‘the combined efforts of everyone to make changes, leading to better patient outcomes (health), better system performance (care) and better professional development (learning) regardless of the theoretical concept or tool utilised’ ( Batalden and Davidoff, 2007:2 ).

In 2007, a national initiative to embed this learning in undergraduate programmes created many opportunities for pre-registration nursing students to develop these skills ( Johnson et al, 2010 ). Students involved in the initiative evaluated it very positively and subsequent studies suggest it enhanced their understanding of the practicalities of implementing service improvement activity ( Machin and Jones 2014 ). Johnson et al's (2010) study suggested that resistance from staff, lack of time and student status were barriers to the success of students' service improvement efforts. Despite challenges, service improvement learning and the opportunity to improve the patient care experience is valued by pre-registration students ( Smith and Lister, 2011 ), with classroom-based sessions seen as beneficial for learning ( Baillie et al, 2014 ; Smith et al, 2014 ). Educational programmes encompassing service improvement have helped prepare student nurses to make changes in practice when qualified ( Machin and Jones, 2014 ; James et al, 2016 ). However, little is known about the sustainability of this learning.

This study aimed to understand service improvement experiences of undergraduate adult nursing students in their final year of university and up to 12 months into their graduate practice. The following research questions were posed:

- What are student adult nurses' experiences of service improvement in education and its application in the practice learning setting?

- What are registered adult nurses' experiences of service improvement in their first year of clinical practice?

A longitudinal hermeneutic phenomenological design was used to explore participants' perceptions of their pre- and post-qualification experiences of service improvement in nursing. Phenomenology was appropriate as a research methodology because it seeks to understand particular phenomenon as it is lived by participants.

Sampling from five to 25 participants is often suggested for qualitative research methodologies, which include phenomenology. A longitudinal hermeneutic study carried out by Standing (2009) explored the experiences of transition from student to registered nurse. Following the post-qualifying period, there was 50% attrition. This helped inform the decision to include 20 participants in the present study, a sufficient number to enable rich data collection and allow for potential attrition during phase 2 (there were 15 participants for phase 2, an attrition of 5).

Participants had completed a service improvement module as part of their second-year education programme, where they engaged with service improvement, explored theoretical improvement methodologies and appraised via a written assessment of their experiences.

All participants' placements were in the NHS trust that was likely to be the location of their first staff nurse job. This was important to enable post-graduate follow-up. The 20 students gave consent to be individually interviewed twice, once as a student and again in their first year of being qualified.

An interview schedule was developed to facilitate semi-structured interviews in both phases of the study. Robson (2011) suggested that interview schedules should incorporate an introduction, a focused lead question and several key questions or prompts:

- What does service improvement mean to you?

- What do you understand about service improvement?

- What experience have you had of service improvement learning?

- What experience have you had of service improvement in practice?

- Has there been anything in your service improvement experience that has changed the way you feel about it or the way you facilitate it?

- Is there anything else you want to tell me about your role in service improvement?

Each participant was asked the same opening question and the same final question.

Forty interviews lasting 30-45 minutes were undertaken by the lead researcher (LC) at the university, digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Digital and written data were stored in line with data protection policy. Data were analysed using a phenomenological, hermeneutic circle approach ( van Manen, 1990 ), comprising three stages ( Lindseth and Norberg, 2004 ), and the process was informed by re-reading the relevant literature:

- Transcripts were read and recordings listened to in order to understand the context of each participant

- Key themes across the transcripts were identified and clustered into overarching themes

- These themes were then interpreted to develop in-depth understanding of participant experiences of service improvement learning and practice.

Researcher understanding of participants' experiences was checked with them throughout data collection. Member checking occurred with participants concurrently as part of each interview during both phases.

A transparent audit trail of researcher decision-making ensured that the study and its results were trustworthy ( Guba and Lincoln, 1994 ).

Ethical permission

Ethical permission was given by the university's ethical approval committee and the research development department at the participating NHS trust.

van Manen's (1990) six-step approach was used because it was congruent with the research methodology and is conducive to analysing hermeneutic phenomenological data. Although there are six steps, the process undertaken was not linear and the lead researcher (LC) frequently returned to the hermeneutic circle for naive reading, re-reading and interpretation of the transcripts throughout each stage of analysis ( Table 1 ). Gadamer (1979) supports this approach, suggesting that movement between the six activities, forward and backward, allows researchers the time to consider, reconsider and reflect on the parts and the whole. It is through these activities that the researcher can fully engage in the hermeneutic circle and enabled them to identify convergent and divergent viewpoints.

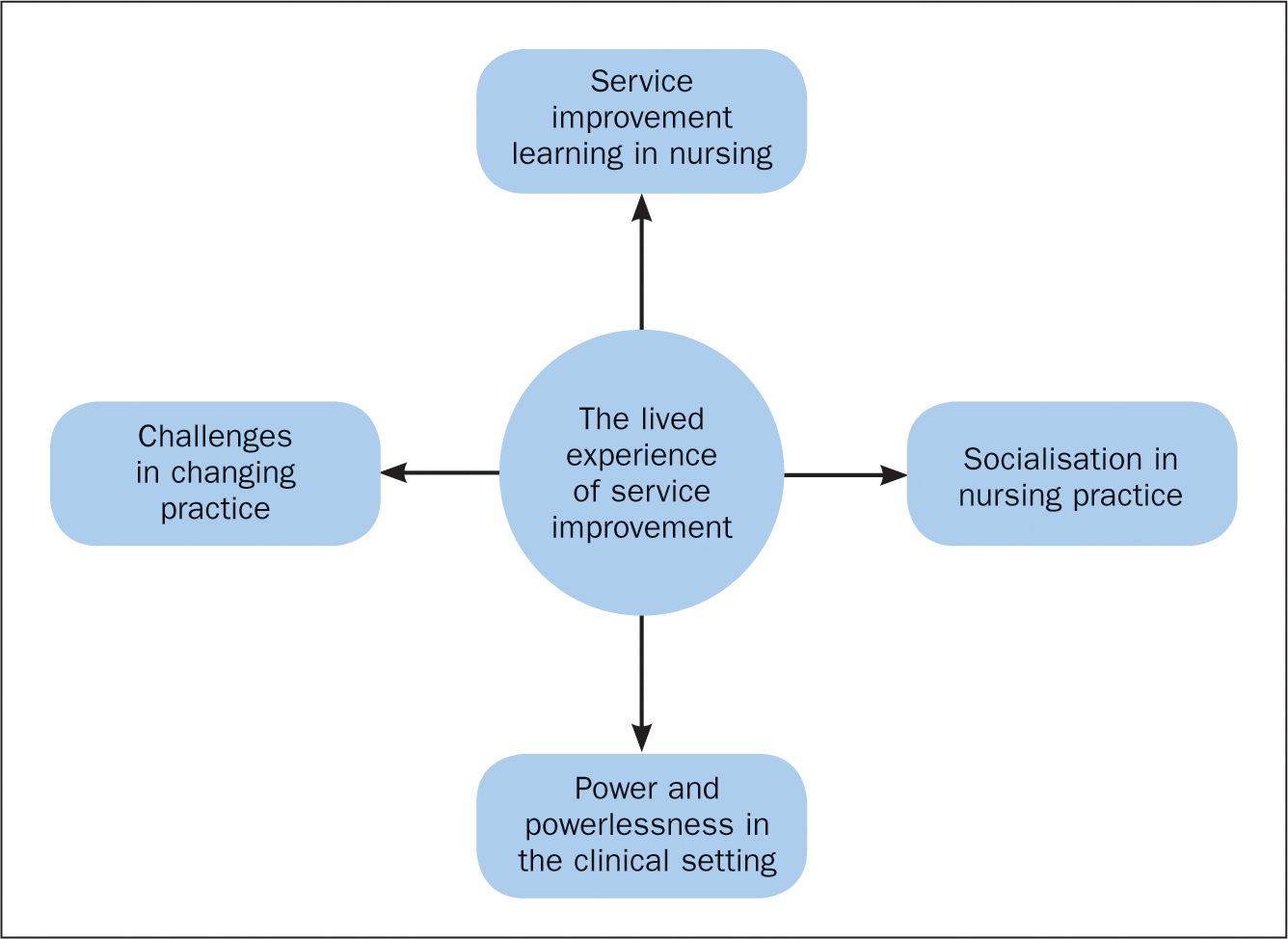

Four overarching themes emerged from the hermeneutic data analysis of the participants' ( Figure 1 ):

Service improvement learning in nursing

Socialisation in nursing practice, power and powerlessness in the clinical setting.

- Challenges in changing practice.

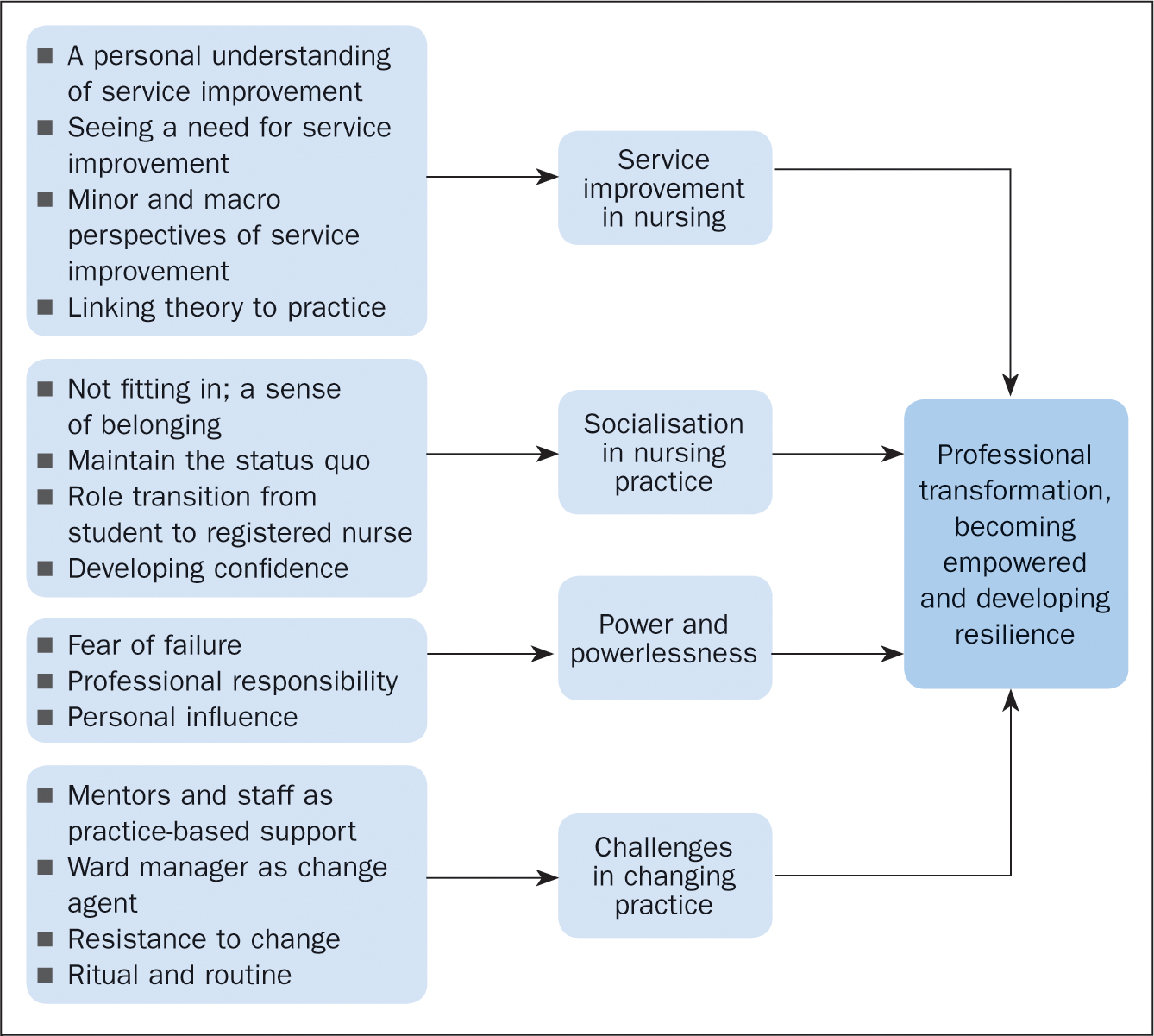

Service improvement in nursing was an overarching theme incorporating subthemes, such as a personal understanding of service improvement, seeing a need for service improvement, micro and macro perspectives of service improvement and linking theory to practice. It was evident in the findings that all participants had socially constructed an understanding of service improvement and were able to give a definition of what this meant to them. The findings illustrated that participants had experienced service improvement both in university and in their clinical practice.

As students, they conveyed their understanding of service improvement, citing their rationale, and applied theoretical models and different approaches for the process:

‘[Service improvement] means trying to improve and change the service so patients have a better experience, an overall experience’

Another participant also identified a patient-focused rationale for service improvement:

‘[Service improvement is] changing any service or [a] service that you give to patients, so it could be an intervention or some other way care is given or organised’

This understanding stayed with the newly qualified participants; however, they talked about their nursing role in service improvement in a more personalised way, recognising the scope of the contribution they could make as individual newly qualified practitioners:

‘Looking back, you gain knowledge and skills as your career progresses. You don't want to go in with a huge service improvement, just start little and build up. I have used some of the theory about change and PDSA [plan, do, study, act]. I am always reflecting and learning’

Another talked about the importance of having service improvement confidence, despite being newly qualified and still on a learning journey:

‘I am still learning, but if you have a good idea about something, having the confidence to go with it, giving reasons and rationale as to how and why you want to do it, to improve the patients service’

Several participants described service improvement opportunities within the preceptorship period as consolidating their learning:

‘As part of preceptorship I did service improvement. We have the knowledge and skills framework, which we have to work towards. Without learning, you would never be getting to best practice. I think, if you don't look for how you can improve your service, you don't improve things for your patients’

Several of the new registrants recognised that, as lifelong learners, there may be a time when they would need to refresh their understanding of service improvement learning theory, for example:

‘If I was doing some service improvement, I would look back at the theories behind it. I would have a good read and re-educate myself’

It was apparent that socialisation and learning in nursing practice was an important feature for participants, both when they were students and as registered nurses. Socialisation is a process that starts during nurse education and continues throughout a nurse's career ( Dinmohammadi et al, 2013 ; Strouse and Nickerson, 2016 ). Socialisation in nursing occurs through social interactions with colleagues in clinical practice and can have both positive and negative consequences concerning the development of nurses ( Gray and Smith, 1999 ; Mackintosh, 2006 ).

Service improvement confidence was not always experienced by student participants who, arguably, had not yet been fully socialised into the nursing community of practice. One student participant felt they did not really belong to the clinical area team within which they were trying to make improvements:

‘As a student, I think it is difficult to fit in, you haven't been properly socialised into the team’

Another expressed the same feelings, describing having to ‘fit in’ as a prerequisite to making changes of any kind:

‘You don't feel you belong. It doesn't matter what you do. You have to just learn to fit in. You're not part of the social scene. I felt not supported [in service improvement activity]’

Several suggested that they tried to join conversations to develop relationships with work colleagues, but were ignored:

‘They did not like the idea of me coming in as an outsider and changing [service improvements]. You don't fit in. You would go to lunch and try and join the conversation, and they would blank you. It wasn't sociable’

At a time when retention of nursing students on their course is a national priority, this perceived lack of support on placement is of concern. However, this perception changed after the nurses became qualified and were employed in their first job. Fitting in and having supportive relationships was perceived as important:

‘As a student you weren't embedded in a culture or in a team quite yet. You were an outsider with outside views which is sometimes good, but when you are working here all the time it is easier to pick up the things that need a little bit of help’

This sense of becoming an ‘insider’ is an indication of the participants' socialisation into the nursing profession post-qualification. Another newly qualified participant also reflected on how different she had felt as a student:

‘When I look back to being a student, I don't think I was ever really part of the team. Compared to now’

As students, and later as registered nurses, the participants discussed an awareness of power in the context of making changes through service improvements. They were aware of power as a dynamic in the clinical environment and that this influenced how they approached and undertook service improvements in practice. Power and powerlessness emerged as an important feature in how they experienced service improvements in nursing.

Nursing occurs in a social environment, where power impacts nurses in context of their working situation ( Gray and Thomas, 2005 ). Power pervades social norms and sustains power-imbalanced relationships ( Potter, 1996 ; Gray and Thomas, 2005 ). In this context, this theme had three related subthemes: personal influence, fear of failure and professional responsibility. Student participants were aware of the power imbalance in the clinical environment and this influenced how they approached their service improvements projects. Some felt powerless because of their student nurse status:

‘There was nothing, nothing [service improvement] I could do as a lowly student nurse’

Another, who had also felt powerless, suggested that common assumptions were that service improvements were implemented ‘top-down’, driven by people more ‘senior’ with more organisational power:

‘I am still in my little white student nurse uniform, not higher up. I have no power. I think a lot of people expect service improvement to come from higher up’

This perception reflects a lack of confidence as a student for engaging in ‘bottom-up’ improvements and change. As registered nurses participants noted a tangible change in their power, status, responsibility and authority in making improvements once they had qualified:

‘It's completely different, looking back. [As a staff nurse] I am aware of it [service improvement] in everything I do. I am aware of small things every day that you can do to improve the service. You can see where the flaws are. We have the power now to say, “maybe we can change this’ ”

Another participant felt empowered in her newly qualified status, and able to suggest changes proactively:

‘Now, when qualified, you do have a say [in service improvement] and it's important that I do speak up … you do have the power to say how things are done’

Another recently qualified participant described the transition phase between student and becoming a registered nurse as being an optimum time to engage in service improvement:

‘Looking back, you are in the best place. You just come in from university with new eyes and want to improve’

This suggests that harnessing service improvement enthusiasm in the important preceptorship period and empowering graduates might be a way of maintaining the sustainability of service improvement learning and practice.

Challenges in changing practice

There were several subthemes associated with challenges to change: mentors and staff as practice-based support, ward manager as change agent, resistance to change and ritual and routine. Positive relationships in clinical practice were key enablers for overcoming challenges in implementing service improvement. For students, perhaps understandably, it was the positive, effective mentors they had encountered who helped them to feel good about their service improvement efforts:

‘It depends who you work with. You can have some mentors who are quite good at facilitating change and asking for ideas, and they have some respect for the student. You are not just another body’

‘My mentor was brilliant, she respected student nurses … She was a role model for me [in service improvement]’

Some of the newly qualified nurse participants reflected on their student experiences. They were able to make comparisons between their experiences then and now, in trying to overcome service improvement challenges. They also identified relationships within teams as factor influencing nurses' ability and opportunity to challenge and improve practice:

‘As a student, you don't have the confidence to implement anything. I guess it's how well you get on in the team, but moving from placement to placement all the time makes it really difficult. As a qualified member of the team you get on well with everyone. You fit in and you wouldn't be afraid to say to someone, “maybe we can do it this way” ’

Having colleagues on the ward with a research role seemed to be something that could enhance the receptivity of staff to new ideas and try them out:

‘I would go and see the other nurses and see what they thought, if there was enough “oomph” behind it. We have a lot of research nurses … They are a great support’

People-focused ward managers were key enablers in empowering qualified participants to make improvements:

‘Definitely our ward manager supports change and values your ideas, and always listens to what you have to say’

‘She [the sister] was really receptive. She was a great help to me’

Strong leadership skills were identified by another as pivotal to embedding a service improvement culture where challenges could be overcome:

‘They [the ward manager] is confident, they are a strong leader. They are supportive, open to staff opinions; not only listening to senior staff member, but to everybody’

Self-determination was identified as a way of overcoming the challenges of implementing service improvement. One student participant said:

‘I just got on with it [service improvement]. I got a bit more confident. Sometimes you can't please everyone, you just have to get on with things’

Several participants, once qualified, discussed how, despite challenges, they would persevere, believing that they had an important role to play in improving care for patients:

‘If you don't look at how you can improve your services, you don't improve things for your patients. There are not going to be any advances, you are not going to use any evidenced-based practice’

One participant suggested that continuous improvement and change were essential to ensure that patients received the best, contemporary, evidence-based nursing care:

‘If you are stuck in your ways and set in a certain pattern, you are not always going to meet everybody's needs, and it could be detrimental to patients’

Summary of findings and further theoretical development

In keeping with hermeneutic phenomenology, the four key themes and related subthemes have been presented supported by literature to inform the analysis of the findings ( Draucker, 1999 ). Through further theoretical analysis of each key theme, there was evidence that a range of contextual, professional and behavioural factors were influencing the lived experience of the participants engaging in service improvement ( Figure 2 ). These factors and the four themes identified were synthesised into three overarching processes experienced by participants: professional transformation, developing resilience and becoming empowered in making service improvements. This helped to develop further understanding of the participants' lived experiences.

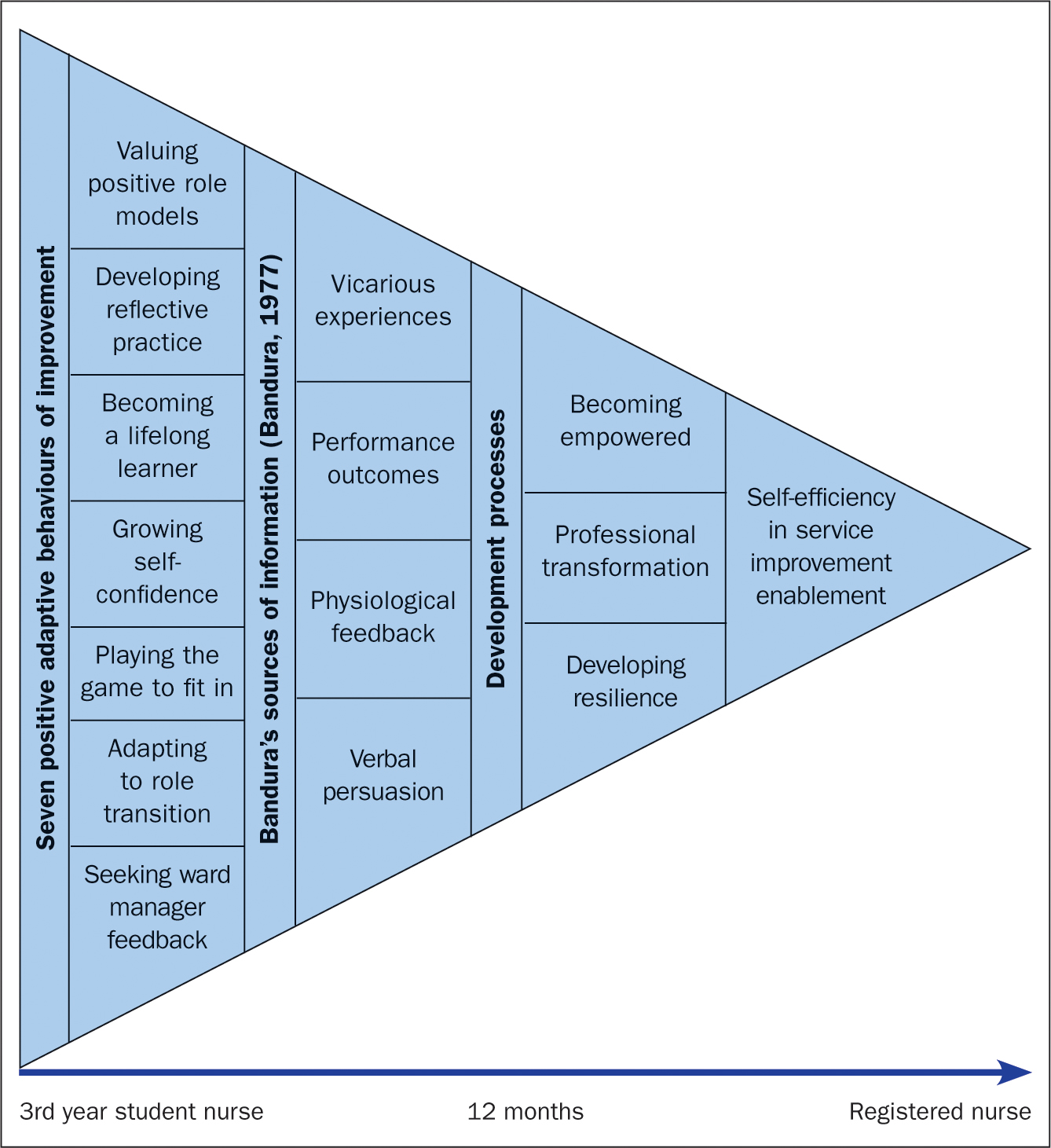

This study aimed to better understand the service improvement experiences of participants as student nurses and throughout their first year of post-registration practice. Across the themes identified common behaviours helped participants engage in service improvement, sustaining their knowledge and enthusiasm post-qualification. Participants were revealing behaviours they had developed in response to their learning and experiences of service improvement in nursing. These ‘positive adaptive behaviours’ are consistent with Bandura (2002) , who found that effective problem solvers are motivated to improve their own practice. The adaptive behaviours identified included ( Figure 3 ):

Valuing positive role models

Developing reflective practice, becoming a lifelong learner, growing in self-confidence, playing the game to fit in, adapting to role transition.

- Seeking ward manager feedback and support.

Several participants (P9, P14, P17, P19, P20) talked about role model mentors and colleagues. They described how their sense of self-efficacy had grown from watching and learning from them as students to seeking to emulate them as qualified nurses. Positive role modelling in nursing usually occurs through a process of mentorship, and helping students to fit in and develop the skills necessary for professional practice (Gignac-Caille and Oermann, 2010; Huybrecht et al, 2011 ; Houghton, 2014 ; Ó Lúanaigh, 2015 ). This study identified that service improvement role models are also important for students and new registrants.

Many participants (P2, P8, P7, P13, P20) reflected on their service improvement experiences. In keeping with other research ( Hatlevik, 2012 ), they perceived that reflection helped bridge the service improvement theory–implementation gap, facilitating development of their identity and knowledge as service improvers. Through reflection, participants developed resilience, as has been reported in other studies ( Jackson et al, 2007 ; Thomas and Revell, 2016 ). Reflection also helped them to identify strategies to overcome service improvement challenges, believing passionately in the positive impact service improvement has on patient care. Bandura (1977) found that learners model their behaviours through being self-reflective and self-reactive.

Two participants (P2, P15) discussed preceptorship and lifelong learning as being integral to the nursing role ( Benner, 1984 ; Nursing and MIdwifery Council, 2018 ). Other studies have shown that professional development that starts in the pre-qualifying period continues throughout a nursing career through lifelong learning ( Davis et al, 2014 ; Coventry et al, 2015 ). In this study, the preceptorship period was crucial for sustaining and further developing service improvement learning. A service improvement mindset was synonymous with a lifelong learning philosophy mindset. Where confidence dipped, participants would return to study the theory underpinning their practice.

Effective ward managers were viewed as those willing to listen and learn from students, as well as qualified staff, where new learning could improve patient care. Effective integration of lifelong service improvement learning into a clinical practice setting culture will also have positive benefits for future students.

Participants (P2, P4, P5, P6, P14, P19) who felt supported in practice developed more self-confidence as service improvers. Conversely, a lack of support from mentors and colleagues impacted negatively on participants' confidence as change agents. Other research has also indicated that student nurses develop self-confidence in practice through positive mentoring experiences, peer support and being successful in practice ( Bahn, 2001 ; Chesser-Smyth and Long, 2013 ). Self-confidence is linked to self-efficacy and reflects an individual's perception of their own ability to perform a goal or task ( Bandura, 1997 ; Potter and Perry, 2001 . Once qualified, participants described growing service improvement self-confidence and self-efficacy through reflective practice and colleague support.

Several participants (P20, P7, P13, P8) described developing what might be called ‘belongingness’ in social psychological terms; through social contact, working on incremental acceptance and becoming an integral component of the group in the clinical practice area ( Baumeister and Leary, 1995 ; Maslow, 2014). Studies suggest that nursing socialisation starts during training, through social interactions in practice placements, and continues throughout a nursing career ( Gray and Smith, 1999 ; Mackintosh, 2006 ; Dinmohammadi et al, 2013 ; Strouse and Nickerson, 2016 ).

As students, participants perceived that their lack of confidence in making service improvements was linked to feelings of not fitting in or lack of belonging, and this was exacerbated by the short length of time spent in any one area. They described the adaptive behaviours they adopted to fit in, such as using previous work and personal stories to start conversations. Some participants perceived that these casual, non-threatening conversations could help them get their service improvement ideas accepted.

Role transition was an important point in participants' service improvement experiences. As students, some of them felt powerless to make service improvements. Research suggests that social norms in nursing sustain power-imbalanced relationships: where this is negative, it can affect practice efficacy ( Potter, 1996 ; Gray and Thomas, 2005 ). Some participants described a feeling akin to ‘transition shock’ ( Duchscher, 2009 ) in the newly qualified period, finding it hard to cope with the competing demands of clinical practice and ongoing learning, including service improvement learning.

This is in keeping with other research suggesting that role transition is complex and challenging ( Maben et al, 2006 ; Feng and Tsai, 2012 ; Hatlevik, 2012 ). In this context, some participants also found it hard to make service improvements during role transition unless it was part of their preceptorship programme expectations ( Chang and Hancock, 2003 ; Schoessler and Waldo, 2006 ; Duchscher, 2008 ; Duchscher, 2009 ; Feng and Tsai, 2012 ; Hatlevik, 2012 ). Nevertheless, through professional transformation, some participants (P1, P2, P4, P16) recognised an increased accountability and responsibility for making service improvements now that they were qualified.

Seeking ward manager feedback and support

Most participants (P2, P4, P5, P12, P9, P16) described ward managers as important in fostering a culture of service improvement and change. The significance of the ward manager in creating ward learning cultures is well documented ( Orton, 1981 ; Fretwell, 1982 ; Ogier, 1986 ; Welsh and Swann, 2002 ; McGowan, 2006 ; Carlin and Duffy, 2013 ). Whether student participants felt empowered to make service improvements depended mainly on ward manager leadership. This leadership was also identified as important by the new registrants. Active engagement from those in senior positions is critical to successful service improvement ( Gollop et al, 2004 ). Nurses can experience high levels of empowerment when ward managers nurture perceptions of autonomy and confidence ( Madden, 2007 ). This study confirms that ward manager leadership is integral to nurse-led service improvement models ( Shafer and Aziz, 2013 ).

A proposed model of self-efficacy in service improvement enablement

The seven positive adaptive behaviours identified ( Figure 3 ) underpinned a process of participant professional transformation towards self-efficacy ( Bandura, 1997 ). With increasing resilience, they felt more empowered to make service improvements as they transitioned from student to registered nurse. The ‘model of self-efficacy in service improvement enablement’ brings together these positive adaptive behaviours as a way of understanding how participants' education and practice were interrelated to influence their service improvement learning and practice.

Although the model is presented as a linear process, the rate of service improvement engagement and development differed between participants, and was influenced by the context of their learning and practice. However, by the time they had made the transition from student to registered nurse they had all achieved a degree of empowerment, resilience and transformation, enabling them to move forward with service improvements in their own work context. This model offers an explanation for other research, which found that nurse-led service improvement requires knowledge and skills that must be continually practised and refined in order to be successful ( Wilcock and Carr, 2001 ; Christiansen et al, 2010 ).

Nursing undergraduate and preceptorship programmes should focus on developing these positive adaptive behaviours towards sustainable service improvement knowledge and skills. Policymakers at local level need to ensure that students and new registrants are supported by ward managers in their implementation of service improvement projects in order to develop their service improvement self-efficacy. Further research with other professional groups and in different healthcare contexts is needed to refine and test the model.

Limitations

This study took place in one university and NHS foundation trust; it is therefore context specific. Participants were in adult nursing only, which reduces transferability of the findings.

This study explored service improvement experiences of adult nurses as students and as qualified practitioners. It showed that they used positive adaptive behaviours to navigate their service improvement learning and practice contexts. The process of becoming service improvement practitioners has been explained through the ‘model of self-efficacy in service improvement enablement’. This provides a framework for understanding how nurses undergo concurrent processes of professional transformation, empowerment and resilience building, through service improvement experiences.

Ward management leadership approaches, supportive colleagues and an opportunity to practise service improvement skills pre-qualifying and in the preceptorship period were identified as essential to develop and sustain service improvement capability. This was important for participants as students but also as qualified nurses, at which time they believed that service improvement practice could be sustained through reflection and lifelong learning.

For all participants the central motivation to push past challenges encountered was a commitment to improving care for the patients they were caring for. This study's findings can inform the practice of nurse educators, practitioners, policy makers and healthcare delivery organisations, thereby potentially making a contribution to global efforts to embed a service improvement culture for the ongoing benefit of all.

- Looking for ways to continually improve the experience of those they care for is a professional responsibility of all nurses in all settings

- Service improvement learning in pre-registration programmes enables the development of nurses' ability to facilitate positive changes in practice

- The positive adaptive behaviours developed through service improvement learning can be sustained through lifelong learning, reflective practice and a supportive work environment, where a commitment to high-quality patient care delivery is prioritised

CPD reflective questions

- How do I view service improvement in practice?

- What skills and knowledge do I have to help me make service improvements in practice?

- How can I meet the gaps in my knowledge and practice?

- How do I support learners in practice in identifying and making service improvements?

- How can I make service improvement central to nursing activity?

Implementing service improvement projects within pre-registration nursing education: a multi-method case study evaluation

Affiliations.

- 1 Faculty of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University London, United Kingdom; University College London Hospitals, London, United Kingdom. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, University of Bedfordshire, United Kingdom. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 3 Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, University of Bedfordshire, United Kingdom. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 4 University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, United Kingdom. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 5 University of Bedfordshire, United Kingdom. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 23867284

- DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2013.06.006

Background: Preparing healthcare students for quality and service improvement is important internationally. A United Kingdom (UK) initiative aims to embed service improvement in pre-registration education. A UK university implemented service improvement teaching for all nursing students. In addition, the degree pathway students conducted service improvement projects as the basis for their dissertations.

Aim: The study aimed to evaluate the implementation of service improvement projects within a pre-registration nursing curriculum.

Method: A multi-method case study was conducted, using student questionnaires, focus groups with students and academic staff, and observation of action learning sets. Questionnaire data were analysed using SPSS v19. Qualitative data were analysed using Ritchie and Spencer's (1994) Framework Approach.

Results: Students were very positive about service improvement. The degree students, who conducted service improvement projects in practice, felt more knowledgeable than advanced diploma students. Selecting the project focus was a key issue and students encountered some challenges in practice. Support for student service improvement projects came from action learning sets, placement staff, and academic staff.

Conclusion: Service improvement projects had a positive effect on students' learning. An effective partnership between the university and partner healthcare organisations, and support for students in practice, is essential.

Keywords: Clinical practice; Dissertation; Evaluation; Service improvement projects; Student nurses.

Copyright © 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Education, Nursing, Baccalaureate / standards*

- Education, Nursing, Baccalaureate / trends

- Focus Groups

- Mentors / psychology*

- Models, Educational

- Qualitative Research

- Quality Assurance, Health Care / methods

- Quality Assurance, Health Care / standards*

- Quality Improvement / standards

- Students, Nursing / psychology*

- Surveys and Questionnaires

- United Kingdom

- Login / Register

‘Let’s hear it for the midwives and everything they do’

STEVE FORD, EDITOR

- You are here: Archive

Changing practice 1: assessing the need for service improvement

22 February, 2016

Before implementing a change in practice, nurses require a systematic, evidence-based approach to identifying gaps in services and the need for change

In order to ensure the service they offer is of an appropriate standard, nurses need to know how to assess its quality, identify the need for change, and implement and evaluate that change. This two-part series offers practical guidance on how to bring about an evidence-based change in practice, and how to demonstrate the success, or otherwise, of that change. It uses the example of an initiative undertaken to improve medicines management in a hospice to illustrate the process. The article also illustrates how work undertaken in changing practice can form part of the evidence submitted in the nurse revalidation process. Part 1 considers how to determine when a change in practice is needed, how to assess and measure current practice, and identify gaps or weaknesses. Part 2 will discuss how to find out why the current practice is falling short of the desired level, and how to go about implementing improvements and measuring the effect of changes.

Citation: Carter H, Price L (2016) Changing practice 1: assessing the need for service improvement. Nursing Times ; 112: 8, 15-17.

Authors: Helen Carter is an independent healthcare advisor; Lynda Price is a clinical governance and infection control facilitator, Helen & Douglas House, Oxford.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here

- Read part 2 of this series here

Introduction

Nurses have a responsibility to preserve safety; this is made clear in the revised code of conduct for nurses (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2015a). The Code states that nurses must “take account of current evidence, knowledge and developments in reducing mistakes and the effect of them and the impact of human factors and system failures”.

Preserving safety involves protecting vulnerable people and ensuring patient safety by reducing errors, rectifying mistakes and reporting concerns immediately. This requires nurses to identify problems and their causes, and put in place changes that will improve safety and the quality of care; it can involve participating in clinical audits and reviews, and any other activity that results in changing practice. This two-part series provides practical advice for nurses wishing to make changes to practice, as well as suggestions for documenting and evaluating the resulting changes.

When nurse revalidation begins in April 2016, the NMC will expect nurses to provide evidence of how they practise effectively. This will involve written information, including personal reflections and feedback from colleagues and patients, and evidence of having undertaken continuing professional development (CPD). Bringing together the expectations from The Code (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2015a) and How to revalidate with the NMC (NMC, 2015b), the article also aims to help nurses consider ways to use the evidence collated in service-improvement projects as part of the material submitted in their revalidation evidence.

Importance of reflective practice

The Royal College of Nursing (2010) has developed a set of eight principles to enable nurses to reflect on their own practice. Principle F highlights the need for evidence-based practice, where “nurses and nursing staff have up-to-date knowledge and skills, and use these with intelligence, insight and understanding in line with the needs of each individual in their care” (Gordon and Watts, 2011). More recently, in the Shape of Caring review, Lord Willis stated that: “Registered nurses and care assistants are required at all levels to adapt, support and lead research and innovation to deliver high-quality care” (Willis, 2015). His recommendations were influenced by the need to celebrate good care and build on the expertise and evidence base of existing clinical practice.

Evidence-based practice has been defined as: “the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values” (Sackett et al, 2000). Implementing a change in practice involves collating a variety of information and analysing the findings against national guidance, service provision and patients’ views of their care.

Identifying the need for change

Nursing practice is continually changing and it is important to identify improvements and deterioration in practice, particularly if they affect patient safety. Identifying issues in practice relies on nurses using their clinical judgement and knowledge to collate relevant information, thoroughly analyse appropriate data and provide robust evidence for the success, or otherwise, of change (Benner, 2000).

Once the need for change has been noticed, the process of bringing about change can be thought of as a series of steps:

- What are we trying to achieve? A review of the relevant evidence-based practice for the particular area of healthcare.

- Are we achieving it? How does current practice measure up to local and national standards?

- Why are we not achieving it? A review of current systems and processes to discover why current practice is falling short.

- What can be done to improve things? Recommendations, timescales and strategies to bring about a change in practice.

- Have things been improved?

Re-audit of current practice and ongoing review to see whetherm change has been successful.

This article explains steps 1 and 2. Steps 3 to 5 will be discussed in part 2 .

What are we trying to achieve?

It is essential to assess current practice within national and local guidance, standards and expectations; this will help to reveal potential gaps in practice and give an indication of what needs to be the main focus of an audit. A range of tools, advice and standards is available that can be used as a baseline or framework for measuring practice. While it is not within the scope of this article to address these in depth, they may include:

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines;

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network;

- National social care standards;

- The Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014 (part 3);

- NHS Commissioning Board Special Health Authority (responsible for patient safety);

- Professional-body standards and guidelines.

Measuring gaps in practice

Regular audits of the structure, processes and outcomes of service provision are key in measuring whether or not established criteria and standards are being met (Chambers et al, 2006). Even in the best services there is likely to be a gap between what is happening in clinical practice and what has been identified as good practice in national and local guidance.

Carey et al (2009) suggested that closing the gap between best evidence and current clinical practice has the potential to improve health outcomes. If a nurse identifies a gap in practice, evidence such as incident forms, complaints, observations made by staff, patients or the public may show whether it is more than an isolated case. Nurses should therefore explore all available evidence, and discussions with colleagues will help to confirm any gap or poor practice

Once clinical issues needing to be addressed have been identified, it is important to select the most appropriate method to measure the quality and standard that should be available to patients; each will have its advantages and disadvantages. The method used to gather information will depend on the aim of the project. Depending on the time, resources and level of support available, clinical leads may choose to use some or all of the following methods:

- Clinical audit;

- Service review;

- Seeking patient and staff feedback;

- Observation of practice;

- Literature review;

- Complaints review;

- Patterns of incident reporting;

- Primary and/or secondary research.

This series uses a case study of some of the processes used by a nurse who undertook a medicines-management audit in a hospice, outlined in Box 1. Clinical audit is “a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes through a systematic review of care against explicit criteria and the implementation of change” (NICE, 2002). Based on the audit cycle, Fig 1 (attached) outlines the processes that can be followed to maintain a robust approach to any project. Since the process is a cycle, once an audit has been undertaken and the relevant changes made, a re-audit should be carried out to close the loop and evaluate how the service is performing after making changes.

Box 1. Case study: Investigating medication errors in a hospice

A nurse working in a hospice was studying for an infection prevention and control qualification. The assignment for a module on quality and clinical governance was to identify an area of practice in which the standards of care could be improved. This involved using clinical governance tools and techniques, such as clinical audit, risk management, change management and evidence-based practice.

Within the organisation was a steady flow of incident reports concerning medication errors. The nurse decided to look into the issue to see if she could find any patterns, causes or contributing factors that might reveal why the errors were occurring. With this information the nurse would be able to recommend a change in practice that would improve the quality of care patients received.

The nurse began by auditing incident forms from the previous 12 months. These were benchmarked against criteria in the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) patient safety incident reports. Using this information, the nurse analysed the current position of the organisation to identify any underlying causes for the errors.

The nurse felt supported by senior staff and undertook the audit with the full backing of the hospice, which viewed medication errors as valuable opportunities for learning on an organisational and personal level. The World Health Organization (2004) suggested that this response to reporting incidents is more likely to improve patient care than the reporting process.

With information gathered about the causes of errors, and collated evidence of best practice, the nurse would be able to make recommendations to reduce the risk or prevent further errors.

Are we achieving it?

Having identified the issue(s) to be audited, the next step in the process (Fig 1, attached) is to assess whether or not the organisation or an identified clinical area is achieving its aims, in this case, the safe administration of medication. It is imperative to analyse the existing situation; a number of tools such as those mentioned above can be used to determine whether the organisation is achieving a high standard of care and, if not, the reasons for this.

A strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis can be undertaken to identify barriers and opportunities for change. This is an integral part of the planning stage, and can save time and frustration at later stages of the project. A SWOT analysis is easy to do, and provides an assessment of internal and external factors that can influence changes in practice. It can be used to support short-term clinical or organisational goals (NICE, 2007).

Table 1 (attached) illustrates a SWOT analysis reviewing potential organisational influences on the prevalence of medication errors in the hospice. In this case, the analysis demonstrated that the organisation was open, trusting, willing to learn from mistakes and share good practice. This attitude is reflected in nursing practice and the willingness of staff to report incidents.

Defining the scope

After the need for change has been identified, the project’s scope and aim need to be described. The scope highlights the area to be included and excluded from the review or audit, while the aim can be an overarching statement to determine the areas of interest. Examples of reflective questions to ask when defining the scope include:

- What is being measured?

- Is this an audit or review?

- What are the risks to patients, staff and the organisation?

- What is the benchmark?

- Are there any standards to indicate what should be achieved?

- Is a baseline audit required?

The rationale for the project needs to be clearly articulated. The hospice nurse identified the aim as being to reduce the risk of preventable medication errors, thus improving the quality and safety of care.

Documenting change

Records are a vital component throughout the process of change, in order to provide evidence of how issues were identified and why service aims were not being achieved; recommendations to improve practice; and to show that the service has improved. The nature of this cyclical process means that monitoring and ongoing reviews determine whether the change has had an impact on practice or not.

Having identified where practice is not meeting the required national and local standards, the next step it to find out why this is happening and what could be done to improve practice. This will be discussed in part 2 .

- Nurses are required to have up-to-date skills

- Evidence-based practice is a cornerstone of all healthcare

- As part of revalidation, nurses will need to provide evidence to support practice

- Regular audits of service provision will measure standards

- Audit/review cycle ensures high standards

Related files

240216_assessing-the-need-for-service-improvement.pdf, fig 1 the cycle of audit and reevaluation.pdf, table 1 swot analysis of the hospice.pdf.

- Add to Bookmarks

Have your say

Sign in or Register a new account to join the discussion.

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Learning Zone Previous Next

Using service improvement methodology to change practice, william gage lead nurse for practice development and innovation, imperial college healthcare nhs trust, london..

This article discusses the role of service improvement methodology in changing the quality of care delivered. It outlines the six-stage framework for quality improvement recommended by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. The reader is encouraged to complete a series of activities to plan and deliver a service improvement project. Potential challenges to the successful delivery of a service improvement project are also considered. The article concludes with an example of the use of the six-stage framework to improve the quality of urinary catheter care in one acute NHS trust.

Nursing Standard . 27, 23, 51-57. doi: 10.7748/ns2013.02.27.23.51.e7241R1

This article has been subject to double blind peer review

Received: 03 October 2012

Accepted: 16 November 2012

management - leadership - quality - change management - quality improvement - service improvement

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

06 February 2013 / Vol 27 issue 23

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Using service improvement methodology to change practice

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Service improvement in health care: a literature review

- Nursing, Midwifery and Health

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

Access to Document

- 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.15.893

Fingerprint

- Nursing Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Enalapril Maleate Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Nurse Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Service Development Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Literature Review Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Error Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Treatment Outcome Nursing and Health Professions 100%

- Cost Control Nursing and Health Professions 100%

T1 - Service improvement in health care

T2 - a literature review

AU - Craig, Lynn

PY - 2018/8/9

Y1 - 2018/8/9

N2 - Service improvements in health care can improve provision, make cost savings, streamline services and reduce clinical errors. However, on its own it may not be adequate for improving patient outcomes and quality of care. The complexity of healthcare provision makes service improvement a challenge, and there is little evidence on whether improvement initiatives change healthcare practices and improve care. To understand the concept of service development within health care, it is necessary to explore the national context and how the NHS has adopted improvement initiatives. To equip the nursing workforce with the skills necessary to make positive change, higher education institutions have developed courses that include the topic within their pre-registration programmes. However, service improvement is a learned skill that nurses need to practise in order to become competent.

AB - Service improvements in health care can improve provision, make cost savings, streamline services and reduce clinical errors. However, on its own it may not be adequate for improving patient outcomes and quality of care. The complexity of healthcare provision makes service improvement a challenge, and there is little evidence on whether improvement initiatives change healthcare practices and improve care. To understand the concept of service development within health care, it is necessary to explore the national context and how the NHS has adopted improvement initiatives. To equip the nursing workforce with the skills necessary to make positive change, higher education institutions have developed courses that include the topic within their pre-registration programmes. However, service improvement is a learned skill that nurses need to practise in order to become competent.

KW - Service improvement

KW - Nursing, practice development

KW - Quality improvement

U2 - 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.15.893

DO - 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.15.893

M3 - Article

SN - 0966-0461

JO - British Journal of Nursing

JF - British Journal of Nursing

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- 10 Essential Public Health Services

- Cooperative Agreements, Grants & Partnerships

- Public Health Professional: Programs

- Health Assessment: Index

- Research Summary

- COVID-19 Health Disparities Grant Success Stories Resources

- Communication Resources

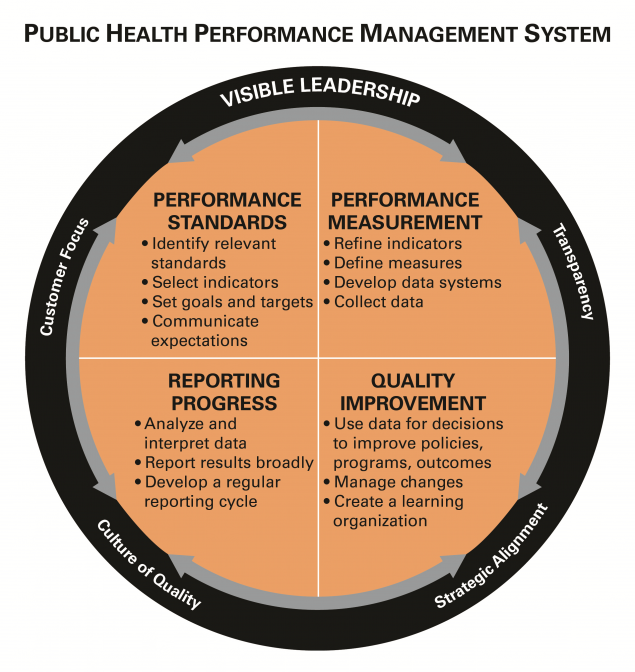

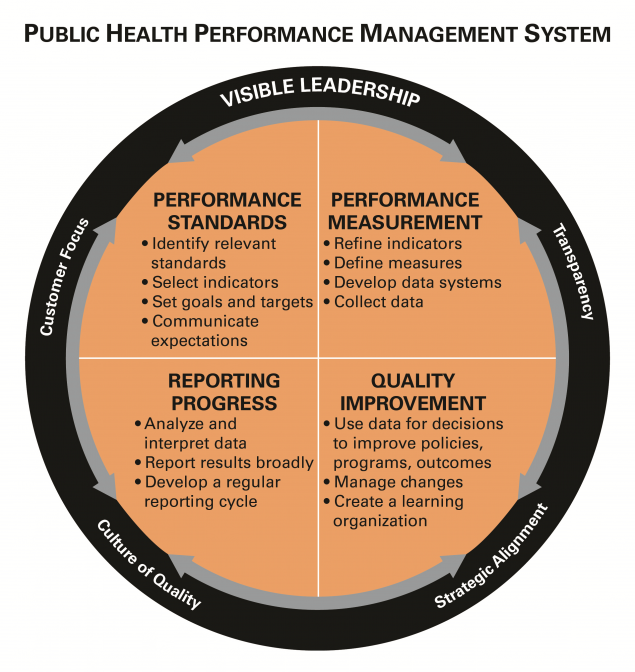

Performance Management and Quality Improvement: Definitions and Concepts

At a glance.

In the public health field, many initiatives and organizations focus on improving public health practice, using different terms. This page provides common definitions for public health performance management.

Definitions and concepts

There has been a rapidly growing interest in performance and quality improvement within the public health community, and different names and labels are often used to describe similar concepts or activities. Other sectors, such as industry and hospitals, have embraced a diverse and evolving set of terms but which generally have the same principles at heart (i.e., continuous quality improvement, quality improvement, performance improvement, six sigma, and total quality management).

In the public health field, an array of initiatives has set the stage for attention to improving public health practice, using assorted terms. The Turning Point Collaborative focused on performance management, the National Public Health Performance Standards Program created a framework to assess and improve public health systems, while the US Department of Health and Human Services has provided recommendations on how to achieve quality in healthcare . In 2011, the Public Health Accreditation Board launched a national voluntary accreditation program that catalyzes quality improvement but also acknowledges the importance of performance management within public health agencies. Regardless of the terminology, a common thread has emerged—one that focuses on continuous improvement and operational excellence within public health programs, agencies, and the public health system.

To anchor common thinking, below are links to some of the definitions that are frequently used throughout these pages.

Key definitions

- Riley et al, "Defining Quality Improvement in Public Health", JPHMP, 2010, 16(10), 5-7.

- Public Health Accreditation Board Acronyms and Glossary of Terms, Version 2022 [PDF]

Public Health Gateway

CDC's National Center for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Public Health Infrastructure and Workforce helps drive public health forward and helps HDs deliver services to communities.

Message placeholder

- A. V. Khutorskoy Key competencies and educational standards , Internet magazine “Eidos”. (2002), URL: http://eidos.ru/journal/2002/0423.htm 194 (data of access: 05.10.2017) [Google Scholar]

- A. V. Khutorskoy Design technology of key and subject competences , Internet magazine “Eidos”. (2005), URL : http://www.eidos.ru/yournal/2006/0505.htm 195 (data of access: 25.09.2017) [Google Scholar]

- V.I. Zvonnikov, M.B. Chelyshkova Evaluation of the quality of learning outcomes in attestation: competence approach (Logos, Moscow, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- A. A. Ozerina Professional identity of undergraduate students. PhD dissertation. (Yaroslavl, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Y. P. Povarenkov, Siberian psychological journal. 24 , 53–58, (2006) [Google Scholar]

- E. V. Voevoda Theory and practice of professional language training of international specialists in Russia PhD dissertation (Moscow, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- A. S. Nekrasov The development of professional identity of the cadet military school. PhD dissertation (Krasnodar, 2005) [Google Scholar]

- M. V. Panfilova Professional and personal identification as a factor in the formation of the future tourism Manager . Extended abstract of PhD dissertation. (Krasnodar, 2008) [Google Scholar]

- V.L. Zhvetkov, Y. V. Slobodchikov, Psychopedagogy in law enforcement 1(52) , 30–32, (2013) [Google Scholar]

- J. Mohtashami, H. Rahnama, F. Farzinfard, A. Talebi, F. Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, M. A. Ghalenoee Open Journal of Nursing 5 , 765–772, [Google Scholar]

- S. L. Rubinstein Principles and ways of development of psychology (AN SSSR, Moscow, 1959) [Google Scholar]

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

Theses and Dissertations Collection

Open Access Repository of University of Idaho Graduate ETD

Description

An open access repository of theses and dissertations from University of Idaho graduate students. The collection includes the complete electronic theses and dissertations submitted since approximately 2014, as well as, select digitized copies of earlier documents dating back to 1910.

Top Subjects

computer science ecology electrical engineering natural resource management mechanical engineering plant sciences water resources management education civil engineering environmental science animal sciences forestry engineering materials science agriculture biology chemical engineering wildlife management

Top Programs

natural resources education mechanical engineering computer science electrical and computer engineering plant, soil and entomological sciences civil engineering environmental science english water resources movement & leisure sciences animal and veterinary science anthropology chemical and materials science engineering geology curriculum & instruction bioinformatics & computational biology chemistry

1910 to 2023 View Timeline

1893 PDFs 395 Records 147 Embargoed ETDs View table

Collection as Data (click to download)

Metadata CSV Metadata JSON Subjects JSON Subjects CSV Timeline JSON Facets JSON Source Code

On the Problem of Cooperation of the Reaction of Hands: I. Cooperation of Hand Reaction to Sound and Light Stimuli in Healthy Subjects

- Published: November 2002

- Volume 28 , pages 698–701, ( 2002 )

Cite this article

- S. M. Blinkov 1 &

- M. G. Nikandrov 1

44 Accesses

Explore all metrics