Differentiated Instruction as an Approach to Establish Effective Teaching in Inclusive Classrooms

- Open Access

- First Online: 28 June 2023

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Esther Gheyssens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4871-6780 4 , 5 ,

- Júlia Griful-Freixenet ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9317-9617 5 , 6 &

- Katrien Struyven ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6562-2172 5 , 7

10k Accesses

2 Citations

Differentiated Instruction has been promoted as a model to create more inclusive classrooms by addressing individual learning needs and maximizing learning opportunities. Whilst differentiated instruction was originally interpreted as a set of teaching practices, theories now consider differentiated instruction rather a pedagogical model with philosophical and practical components than the simple act of differentiating. However, do teachers also consider differentiated instruction as a model of teaching? This chapter is based on a doctoral thesis that adopted differentiated instruction as an approach to establish effective teaching in inclusive classrooms. The first objective of the dissertation focused on how differentiated instruction is perceived by teachers and resulted in the DI-Quest model. This model, based on a validated questionnaire towards differentiated instruction, pinpoints different factors that explain differences in the adoption of differentiated instruction. The second objective focused on how differentiated instruction is implemented. This research consisted of four empirical studies using two samples of teachers and mixed method. The results of four empirical studies of this dissertation are discussed and put next to other studies and literature about differentiation. The conclusions highlight the importance of teachers’ philosophy when it comes to implementing differentiated instruction, the importance of perceiving and implementing differentiated instruction as a pedagogical model and the importance and complexity of professional development with regard to differentiated instruction.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Differentiated Instruction, Perceptions and Practices

Measuring differentiated instruction in The Netherlands and South Korea: factor structure equivalence, correlates, and complexity level

Defining differentiation in cyber schools: what online teachers say.

- Differentiated instruction

- Effective teaching

- Inclusive classrooms

1 Introduction

Differentiated Instruction (DI) has been promoted as a model to facilitate more inclusive classrooms by addressing individual learning needs and maximizing learning opportunities (Gheyssens et al., 2020c ). DI aims to establish maximal learning opportunities by differentiating the instruction in terms of content, process, and product in accordance with students their readiness, interests and learning profiles (Tomlinson, 2017 ). This chapter is based on a doctoral thesis that adopted DI as an approach to establish effective teaching in inclusive classrooms. This doctoral dissertation consisted of four empirical studies towards the conceptualisation and implementation of DI (Gheyssens, 2020 ). This chapter summarizes the most important results of this dissertation and includes three parts. First the conceptualisation of DI is discussed. Second, we discuss literature findings regarding the effectiveness of DI. Third, the results of the studies about the implementation of DI are discussed. Finally, based on the previous parts some recommendations for implementation are presented.

2 Conceptualisation of Differentiated Instruction

2.1 defining differentiated instruction.

Differentiated instruction (DI) is an approach that aims to meet the learning needs of all students in mixed ability classrooms by establishing maximal learning and differentiating instruction with regard to content, process and product in accordance with student needs in terms of their readiness (i.e., student’s proximity to specified learning goal), interests (i.e., passions, affinities that motivate learning) and learning profiles (i.e., preferred approaches to learning) (Tomlinson, 2014 ). Whilst DI was originally interpreted as a set of teaching practices or simplified as the act of differentiating (e.g. van Kraayenoord, 2007 ; Tobin, 2006 ), it is evolved towards a pedagogical model with philosophical and practical components (Gheyssens, 2020 ). This model is rooted in the belief that diversity is present in every classroom and that teachers should adjust their education accordingly (Tomlinson, 1999 ). Tomlinson ( 2017 ) states that DI is an approach where teachers are proactive and focus on common goals for each student by providing them with multiple options in anticipation of and in response to differences in readiness, interest, and learning needs (Tomlinson, 2017 ). From this perspective, differentiation refers to an educational process where students are made accountable for their abilities, talents, learning pace, and personal interests (Op ‘t Eynde, 2004 ). This means that teachers proactively plan varied activities addressing what students need to learn, how they will learn it, and how they show what they have learned. This increases the likelihood that each student will learn as much as he or she can as efficiently as possible (Tomlinson, 2005 ). Moreover, DI emphasizes the needs of both advanced and struggling learners in mixed-ability classroom. In more detail, Bearne ( 2006 ) and Tomlinson ( 1999 ) consider differentiation as an approach to teaching in which teachers proactively adjust curricula, teaching methods, resources, learning activities and student product so that various student’s needs are satisfied (individuals or small groups) and every student is provided with maximum learning opportunities (in Tomlinson et al., 2003 ).

2.2 The DI-Quest Model

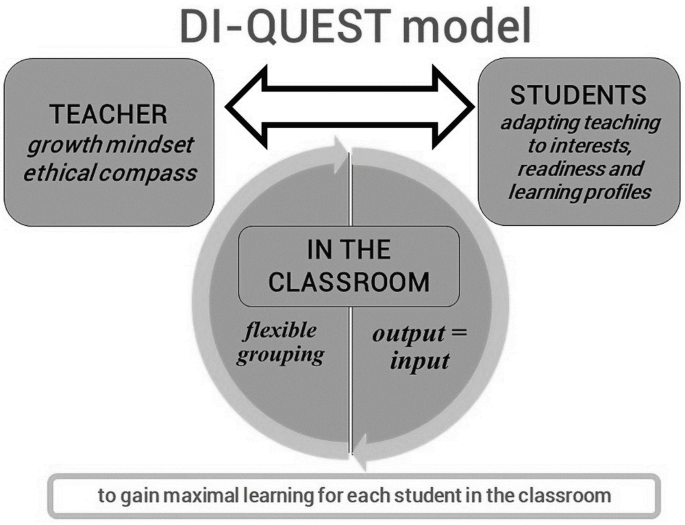

Considering DI as a pedagogical model rather than as a set of teaching strategies became also clear in the validity study of Coubergs et al. ( 2017 ) when they tried to measure DI empirically. Their research resulted in the so-called ‘DI-Quest model’, based on the DI-questionnaire the researchers developed for investigating DI. This model pinpoints different factors that explain differences in the adoption of differentiated instruction (Coubergs et al., 2017 ). It was inspired by the differentiated instruction model developed by Tomlinson ( 2014 ), which presents a step by step process demonstrating how a teacher moves from thinking about DI toward implementing it in the classroom. According to this model, the teacher can differentiate content, process, product, and environments to respond to different needs in learning based on students’ readiness, learning profiles, and interests. Tomlinson ( 2014 ) also stipulates that, to respond adequately to students’ learning needs, teachers should apply general classroom principles such as respectful tasks, flexible grouping, and ongoing assessment and adjustment. In contrast with Tomlinson’s well-known DI model, which also contains concepts relating to good teaching, the DI-Quest model distinguishes teachers who use DI less often from those who use it more often (Gheyssens et al., 2020c ). The DI-Quest model comprises five factors. The five factors are presented in three categories. The key factor, similar to Tomlinson’s ( 2014 ) model, is adapting teaching to students’ readiness, interests, and learning profiles. This is the main factor because it represents the ‘core business’ of differentiating: the teachers adapt his/her teaching to three essential differences in learning. The second and third factors represent DI as a philosophy. The fourth and fifth factor represent differentiated strategies in the classroom (Fig. 30.1 ). Below the figure the different factors are discussed on detail.

The DI-Quest model

2.2.1 Adaptive Teaching

Adaptive teaching illustrates that the teacher provides various options to enable students to acquire information, digest, and express their understanding in accordance with their readiness, interests, and learning profiles (Tomlinson, 2001 ). Differences in learning profiles are described by Tomlinson and colleagues ( 2003 , p. 129) as “a student’s preferred mode of learning that can be affected by a number of factors, including learning style, intelligence preference and culture.” Applying different learning profiles positively influences the effectiveness of learning because students get the opportunity to lean the way they learn best. Responding to student interests also appears to be related to more positive learning experiences, both in the short and long term (Woolfolk, 2010 ; Tomlinson et al., 2003 ). Ryan and Deci ( 2000 ) claimed that understanding what motivates students will help develop interest, joy, and perseverance during the learning process. Thus, investing in differences in interests increases learning motivation among students. Taking account of students’ readiness can also lead to higher academic achievement. Readiness focuses on differences arising from a student’s learning position relative to the learning goals that are to be attained (Woolfolk, 2010 ). When taking students’ readiness into account enables every student to attain the learning objectives in accordance with their learning pace and position (Gheyssens et al., 2021 ).

2.2.2 Philosophy of DI

The first philosophical factor to consider is the ‘growth mindset’. Tomlinson ( 2001 ) addressed the concept of mindset in her DI model by stating that a teacher’s mindset can affect the successful implementation of differentiated instruction (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2011 ). Teachers with a growth mindset set high goals for their students and believe that every student is able to achieve success when they show commitment and engagement (Dweck, 2006 ). The second philosophical factor is the ‘ethical compass’. This envisions the use of curriculum, textbooks, and other external influences as a compass for teaching rather than observations of the student (Coubergs et al., 2017 ; Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010 ). An ethical compass that focuses on the student embodies the development of meaningful learning outcomes, devises assessments in line with these, and creates engaging lesson plans designed to enhance students’ proficiency in achieving their learning goals (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010 ). Research on self-reported practices demonstrated that teachers with an overly rigid adherence to a curriculum that does not take students’ needs into account, report to adopt less adaptive teaching practices (Coubergs et al., 2017 ; Gheyssens et al., 2020c ).

2.2.3 Differentiated Classroom Practices

The next factor is the differentiated practice to be explained is ‘flexible grouping’. Switching between homogeneous and heterogeneous groups helps students to progress based on their abilities (when in homogeneous groups) and facilitates learning through interaction (when in heterogeneous groups) (Whitburn, 2001 ). Given that the aim of differentiated instruction is to provide maximal learning opportunities for all students, variation between homogeneous and heterogeneous teaching methods is essential. Coubergs et al. ( 2017 ) found that combining different forms of flexible grouping positively predicts the self-reported use of adaptive teaching in accordance with differences in learning. The final factor in the DI-Quest model is the differentiated practice ‘Output = input.’ This factor represents the importance of using output from students (such as information from conversations, tasks, evaluation, and classroom behaviour) as a source of information. This output of students is input for the learning process of the students themselves by providing them with feedback. But this output is also crucial input for the teacher in terms of information about how students react to his/her teaching (Hattie, 2009 ). Assessment and feedback are not the final steps in the process of teaching, but they are an essential part of the process of teaching and learning (Gijbels et al., 2005 ). In this regard, Coubergs et al. ( 2017 ) state that including feedback as an essential aspect of learning positively predicts the self-reported use of adaptive teaching.

3 Effectiveness of Differentiated Instruction

Several studies dealing with the effectiveness of DI have demonstrated a positive impact on student achievement (e.g. Beecher & Sweeny, 2008 ; Endal et al., 2013 ; Mastropieri et al., 2006 ; Reis et al., 2011 ; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019 ; Valiandes, 2015 ). However, while recent theories plead for a more holistic interpretation of DI, being a philosophy and a practice of teaching, empirical studies on the impact on student learning are often limited to one aspect of DI, e.g. ability grouping, tiering, heterogenous grouping, individualized instruction, mastery learning or another specific operationalization of DI (e.g. Bade & Bult, 1981 ; Tomlinson, 1999 ; Vanderhoeven, 2004 ; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019 ). Often studies on DI are also fragmented in studies on ability grouping, tiering, heterogenous grouping, individualized instruction, mastery learning or another specific operationalization of DI (Coubergs et al., 2013 ; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019 ). Although effectiveness can be found for most of these operationalisations, overall the evidence is limited and sometimes even inconclusive (e.g. evidence of the benefits on ability grouping). Indeed research indicates that DI has the power to benefit students’ learning. However, this might not always be the case for all students. For example Reis and colleagues demonstrated that at-risk students are most likely to benefit from DI (e.g. Reis et al., 2011 ). By contrast, experimental research on DI by Valiandes ( 2015 ) showed that although the socioeconomic status of students correlated with their initial performance, it had no effect on their progress. This confirmed that DI can maximize learning outcomes for all students regardless of their socioeconomic background. It also depends on how DI is implemented, for example the effects of ability grouping may differ for subgroups of students (Coubergs et al., 2013 ). A recent review on DI concluded that studies of effectiveness of DI overall report small to medium-sized positive effects of DI on student achievement. However, the authors of this study plead for more empirical studies towards the effectiveness of DI on both academic achievement and affective students’ outcomes, such as attitudes and motivation (Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019 ).

4 Implementation of Differentiated Instruction

Differentiated instruction is often presented in a fragmented fashion in studies. For example, it can be defined as a specific set of strategies (Bade & Bult, 1981 ; Woolfolk, 2010 ) or studies with regard to the effectiveness of DI often focus on specific differentiated classroom actions, rather than on DI as a whole-classroom approach (Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019 ). Moreover, DI is not only in studies fragmented defined and investigated, DI is also perceived by teachers in a fragmented way (Gheyssens, 2020 ). For example, using mixed methods, this study explored to what degree differentiated practices are implemented by primary school teachers in Flanders (Gheyssens et al., 2020a ). Data were gathered by means of three different methods, which are compared: teachers’ self-reported questionnaires (N = 513), observed classroom practices and recall interviews (N = 14 teachers). The results reveal that there is not always congruence between the observed and self-reported practices. Moreover, the study seeks to understand what encourages or discourages teachers to implement DI practices. It turns out that concerns about the impact on students and school policy are referred to by teachers as impediments when it comes to adopting differentiated practices in classrooms. On teacher level, some teachers expressed a feeling of powerlessness towards their teaching and have doubts if their efforts are good enough. On school level, a development plan was often missing which gave teachers the feeling that they are standing alone (Gheyssens et al., 2020a ). Other studies confirm that when beliefs about teaching and learning are different among various actors involved in a school, this can limit DI implementation (Beecher & Sweeny, 2008 ). However, we know form the DI-Quest model how important a teachers’ mindset is when it comes to implementing DI. In this specific study teachers were asked about both hindrances and encouragements to implement DI. Teachers only responded with hindrances. In addition, flexible grouping, which in theory is an ideal teaching format when it comes to differentiation, occurs often randomly in the classroom without the intention to differentiate. The researchers of this study concluded that teachers do not succeed in implementing DI to the fullest because their mindset about DI is not as advanced as their abilities to implement differentiated practices. These practices, such as flexible grouping for example, are often part of the curriculum. Moreover, also in teacher education programmes pre-service teachers are trained to use differentiated strategies. However, teacher education programmes approach DI mostly again as a set of teaching practices. Teaching a mindset is much more difficult and complicated. This focus on DI as only a practice and as a pedagogical model, like the DI-Quest model demonstrates, leads to partial implementation of DI. DI is then perceived as something teachers can do “sometimes” in their classrooms, rather than a pedagogical model that is embedded in the daily teaching and learning process (Gheyssens et al., 2020a ).

In other words, one aspect of DI is often implemented, one specific teaching format is applied, or one strategy is adopted to deal with one specific difference between learning. As a consequence, some aspects will be improved or some students will benefit from this approach, but the desired positive effects on the total learning process of all the students that theories about DI promise, will remain unforthcoming. Below some recommendations are listed to implement DI more as a pedagogical model and less fragmented.

4.1 Importance of the Teachers’ Philosophy

Review studies which investigated the effectiveness and implementation of specific operationalizations of DI (for example grouping) report small to medium effects on student achievement (Coubergs et al., 2013 ; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019 ). Although theories recommend approaching DI as a holistic concept, the effectiveness of such a holistic approach on student learning has, to our knowledge, not yet been investigated. We emphasize the importance of presenting and perceiving DI as a pedagogical model that is regarded as a philosophy of teaching and a collection of teaching practices (Tomlinson, 2017 ). Thus, DI is considered a pedagogical model that is influenced by teachers’ mindset and one which encourages teachers to be proactive, involves modifying curricula, teaching methods, resources, learning activities and student products in anticipation of, and response to, student differences in readiness, interests and learning profiles, in order to maximize learning opportunities for every student in the classroom (Coubergs et al., 2017 ; Tomlinson, 2017 ). In this regard we would also like to emphasize that these modifications do not necessary involve new teaching strategies and extra workload for teachers, but require that teachers shift their mindset and start acting more pro-actively, planned better and be more positive. In a study that investigated the effectiveness of a professional development programme about inclusive education on teachers’ implementation of differentiated instruction, teachers stated that after participating in the programme they did not necessarily adopt more differentiated practices, but they did the ones they used more thoroughly (Gheyssens et al., 2020b ). As demonstrated in the DI-Quest model, in order to implement DI as a pedagogical model, it is essential to start with the teachers’ philosophy. However, changing a philosophy does not come about overnight, but rather demands time and patience (Gheyssens, 2020 ).

4.2 Importance and Complexity of Professional Development

When DI becomes a pedagogical model that consists of both philosophy and practice components, and furthermore demands that teachers have a positive mindset towards DI in order to implement DI effectively, professional development for some teachers is necessary to strengthen their competences and to support them in embedding DI in their classrooms. Depending on the current mindset of the teacher, some will need more support, while for other teachers differentiating comes naturally. However, if we want teachers to implement DI as a pedagogical model and not just as fragmented practices, teachers need to be prepared and supported. Professional development is essential for teachers to respond adequately to the changing needs of students during their careers (Keay & Lloyd, 2011 ; EADSNE, 2012 ). However, professional development is also complex. The final study in the dissertation of Gheyssens ( 2020 ) investigated the effectiveness of a professional development programme (PDP) aimed at strengthening the DI competences of teachers. A quasi-experimental design consisting of a pre-test, post-test, and control group was used to study the impact of the programme on teachers’ self-reported differentiated philosophies and practices. Questionnaires were collected from the experimental group (n = 284) and control group (n = 80) and pre- and post-test results were compared using a repeated measures ANOVA. Additionally, interviews with a purposive sample of teachers (n = 8) were conducted to explore teachers’ experiences of the PDP. The results show that the PDP was not effective in changing teachers’ DI competences. Multiple explanations are presented for the lack of improvement such as treatment fidelity, the limitations of instruments, and the necessary time investment (Gheyssens et al., 2020b ).

We found similar information in other studies. For example Brighton et al. ( 2005 ) stated that the biggest challenge for most teachers is that DI questions their previous beliefs. This ties in with our emphasis on teachers’ mindset. To participate in professional development, teachers need to have/keep an open mind in order to respond to new forms of diversity and new opportunities for collaborating with colleagues. Although continued professional development is necessary and important for teachers, it is a complex process. We refer to the work of Merchie et al. ( 2016 ) who identified nine characteristics of effective professional development, with one of them being that the supervisor is of high quality and is competent when it comes to giving and receiving constructive feedback and imparting other coaching skills (Merchie et al., 2016 ). Literature states that professional development is only successful if teachers are active participants, if they have a voice in what and how they learn things, and if the PDP is tailored to the specific context (Merchie et al., 2016 ). However, PDP often works towards a specific goal which is not always very flexible. A suitable coach is able to find a balance between these two extremes. Or, specifically within inquiry-based learning as an example, the coach needs to find the fragile balance between telling the teachers what to do, and letting them find their own answers. Finding such a balance and guiding teachers towards looking for and finding the answers they need is important if we wish to establish the desired improvement we want to see in teachers’ professional development. In this regard, Willegems et al. ( 2016 ) plead for the role of a broker as a bridge-maker in professional development trajectories, in addition to the role of coach (Willegems et al., 2016 ).

4.3 Importance of Collaboration

In addition, collaboration is indeed essential for effective professionalisation (Merchie et al., 2016 ) and beneficial for DI implementation (De Neve et al., 2015 ; Latz & Adams, 2011 ). In a professional development study where inquiry-based learning was applied to teams of teachers at schools, teachers reported positive experiences in discussing their individual learning activities, and during the programme became aware of the need to work together on the collective development of knowledge in the school. They all agreed that to implement DI they needed to collaborate more. A common school vision and policy is necessary for the implementation of specific differentiated measures, as these currently differ between teachers and grades, and can be confusing for students. This is consistent with previous research that states that collaboration is crucial for creating inclusive classrooms (Hunt et al., 2002 ; Mortier et al., 2010 ; EADSNE, 2012 ; Claasen et al., 2009 ; Mitchel, 2014 ). A first step in this process is realising that collaboration is beneficial for both teachers and students (EADSNE, 2012 ).

5 Conclusion

The chapter summarizes a doctoral dissertation that started with the assumption from theory that differentiated instruction can be adopted to create more inclusive classrooms. Theories describe DI as both a teaching practice and a philosophy, but the concept is rarely measured as such. Empirical evidence about the effectiveness and operationalisation of differentiating is limited. The general aim of this research was to gain a more in-depth understanding of the concept of DI. This main aim was subdivided into two objectives. The first objective focused on how DI is perceived by teachers and resulted in the DI-Quest model. The second objective focused on how DI is implemented. Four empirical studies were conducted to address these objectives. Two different samples spread over three years were adopted (1302 teachers in study 1 and 1522 teachers in studies 2, 3 and 4) and mixed methods were applied to investigate these research goals. In this chapter the results of these studies were put next to other studies and literature about differentiation. The conclusions highlight the importance of teachers’ philosophy when it comes to implementing DI, the importance of perceiving and implementing DI as a pedagogical model and the importance and complexity of professional development with regard to DI. Overall, the authors of this dissertation conclude that DI can be as promising as theories say when it comes to creating inclusive classrooms, but at the same time their research illustrated that the reality of DI in classrooms, is far more complex than the theories suggest.

Bade, J., & Bult, H. (1981). De praktijk van interne differentiatie. Handboek voor de leraar . Uitgeverij Intro Nijkerk.

Google Scholar

Bearne, E. (2006). Differentiation and diversity in the primary school . Routledge.

Beecher, M., & Sweeny, S. M. (2008). Closing the achievement gap with curriculum enrichment and differentiation: One school’s story. Journal of Advanced Academica, 19 (3), 502–530.

Article Google Scholar

Claasen, W., de Bruïne, E., Schuman, H., Siemons, H. & van Velthooven, B. (2009). Inclusief bekwaam. Generiek competentieprofiel inclusief onderwijs - LEOZ Deelproject 4 . Garant.

Brighton, C. M., Hertberg, H. L., Moon, T. R., Tomlinson, C. A., & Callahan, C. M. (2005). The feasibility of high-end learning in a diverse middle school . National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented.

Coubergs, C., Struyven, K., Engels, N., Cools, W., & De Martelaer, K. (2013). Binnenklasdifferentiatie. Leerkansen voor alle leerlingen . Acco.

Coubergs, C., Struyven, K., Vanthournout, G., & Engels, N. (2017). Measuring teachers’ perceptions about differentiated instruction: The DI-Quest instrument and model. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 53 , 41–54.

De Neve, D., Devos, G., & Tuytens, M. (2015). The importance of job resources and self-efficacy for beginning teachers’ professional learning in differentiated instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47 , 30–41.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success . Random House.

EADSNE (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education). (2012). Lerarenopleiding en inclusie. Profiel van inclusieve leraren . European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education.

Endal, G., Padmadewi, N., & Ratminingsih, M. (2013). The effect of differentiated instruction and achievement motivation on students’ writing competency. Journal Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris , 1 .

Gheyssens, E. (2020). Adopting differentiated instruction to create inclusive classrooms . Crazy Copy Center Productions.

Gheyssens, E., Consuegra, E., Vanslambrouck, S., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2020a). Differentiated instruction in practice: Do teachers walk the talk? Pedagogische Studieën, 97 , 163–186.

Gheyssens, E., Consuegra, E., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2020b). Good things come to those who wait: The importance of professional development for the implementation of differentiated instruction. Frontiers in Education, 5 , 96.

Gheyssens, E., Coubergs, C., Griful-Freixenet, J., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2020c). Differentiated instruction: The diversity of teachers’ philosophy and practice to adapt teaching to students’ interests, readiness and learning profiles. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26 , 1383.

Gheyssens, E., Consuegra, E., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2021). Creating inclusive classrooms in primary and secondary schools: From noticing to differentiated practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 100 , 103210.

Gijbels, D., Dochy, F., Van den Bossche, P., & Segers, M. (2005). Effects of problem-based learning: A meta-analysis from the angle of assessment. Review of Educational Research, 75 (1), 27–61.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement . Taylor & Francis Ltd.

Hunt, P., Soto, G., Maier, J., Müller, E., & Goetz, L. (2002). Collaborative teaming to support students with augmentative and alternative communication needs in general education classrooms. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18 (1), 20–35.

Keay, J. K., & Lloyd, C. M. (2011). Developing inclusive approaches to learning and teaching. In J. K. Keay & C. M. Lloyd (Eds.), Linking children’s learning with professional learning. Impact, evidence and inclusive practice (pp. 31–44). Sense Publishers.

Chapter Google Scholar

Latz, A. O., & Adams, C. M. (2011). Critical differentiation and the twice oppressed: Social class and giftedness. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34 (5), 773–789.

Mastropieri, M. A., Scruggs, T. E., Norland, J. J., Berkeley, S., McDuffie, K., Tornquist, E. H., & Connors, N. (2006). Differentiated curriculum enhancement in inclusive middle school science effects on classroom and high-stakes tests. The Journal of Special Education, 40 (3), 130–137.

Merchie, E., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., & Vanderlinde, R. (2016). Evaluating teachers’ professional development initiatives: Towards an extended evaluative framework. Research Papers in Education, 33 , 1–26.

Mitchel, D. (2014). What really works in special and inclusive education. Using evidence-based teaching strategies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Mortier, K., Van Hove, G., & De Schauwer, E. (2010). Supports for children with disabilities in regular education classrooms: An account of different perspectives in Flanders. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14 (6), 543–561.

Op ‘t Eynde. (2004). Leren doe je nooit alleen: differentiatie als een sociaal gebeuren. Impuls, 35 (1), 4–13.

Reis, S. M., McCoach, D. B., Little, C. A., Muller, L. M., & Kaniskan, R. B. (2011). The effects of differentiated instruction and enrichment pedagogy on reading achievement in five elementary schools. American Educational Research Journal, 48 (2), 462–501.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and Well-being. American Psychologist, 55 (1), 68.

Smale-Jacobse, A. E., Meijer, A., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Maulana, R. (2019). Differentiated instruction in secondary education: A systematic review of research evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 , 2366.

Sousa, D. A., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2011). Differentiation and the brain: How neuroscience supports the learner – Friendly classroom . Solution Tree Press.

Tobin, R. (2006). Five ways to facilitate the teacher assistant’s work in the classroom. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 2 (6), n6.

Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom. Responding to the needs of all learners . ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms . Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2005). Grading and differentiation: Paradox or good practice? Theory Into Practice, 44 (3), 262–269.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners . ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2017). How to differentiate instruction in academically diverse classrooms . ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Imbeau, M. B. (2010). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom . ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A., Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Brimijoin, K., Conover, L. A., & Reynolds, T. (2003). Differentiating instruction in response to student readiness, interest and learning profile in academically diverse classrooms: A review of the literature. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 27 (2/3), 119–145.

Valiandes, S. (2015). Evaluating the impact of differentiated instruction on literacy and reading in mixed ability classrooms: Quality and equity dimensions of education effectiveness. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 45 , 17–26.

van Kraayenoord, C. E. (2007). School and classroom practices in inclusive education in Australia. Childhood Education, 83 (6), 390–394.

Vanderhoeven, J. L. (2004). Positief omgaan met verschillen in de leeromgeving. Een visie op differentiatie en gelijke kansen in authentieke middenscholen . Uitgeverij Antwerpen.

Whitburn, J. (2001). Effective classroom organisation in primary schools: Mathematics. Oxford Review of Education, 27 (3), 411–428.

Willegems, V., Consuegra, E., Struyven, K., & Engels, N. (2016). How to become a broker: The role of teacher educators in developing collaborative teacher research teams. Educational Research and Evaluation, 22 (3–4), 173–193.

Woolfolk, A. (2010). Educational psychology . The Ohio State University: Pearson Education International.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

Esther Gheyssens

Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Aalst, Belgium

Esther Gheyssens, Júlia Griful-Freixenet & Katrien Struyven

Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Júlia Griful-Freixenet

Universiteit Hasselt, Hasselt, Belgium

Katrien Struyven

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Esther Gheyssens .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Teacher Education, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands

Ridwan Maulana

Michelle Helms-Lorenz

Department of Education, University of York, York, UK

Robert M. Klassen

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Gheyssens, E., Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K. (2023). Differentiated Instruction as an Approach to Establish Effective Teaching in Inclusive Classrooms. In: Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Klassen, R.M. (eds) Effective Teaching Around the World . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31678-4_30

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31678-4_30

Published : 28 June 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-31677-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-31678-4

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Differentiated Instruction for Diverse Learners

Nov 29, 2014

190 likes | 365 Views

Differentiated Instruction for Diverse Learners. Gayle Y. Thieman, Ed.D. Portland State University. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act I.D.E.A.

Share Presentation

- differentiated instruction

- learning goals

- integrating differentiated instruction

- linking quality teaching differentiation

Presentation Transcript

Differentiated Instruction for Diverse Learners Gayle Y. Thieman, Ed.D. Portland State University

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act I.D.E.A. • 1975 PL 94-142 to ensure all children with disabilities have free appropriate public education with special education services to meet unique needs; provided federal funding to states • 1986 requires early intervention and pre-school programs be provided from birth • 1983,1990 requires culturally relevant intervention and assessments linked to instruction • 1997: requires collaborative partnerships, family-friendly practices, emphasizes need to provide services in least restrictive environment (partial or full inclusion in regular education setting) • 1990 Americans with Disabilities ACT (ADA accommodations) • Section 504 of Civil Rights Act ) requires accommodations to individuals with impairment that affects major life activities (ADHD, physical handicap, etc.)

Some Definitions • Individual Education Plan (IEP): reviewed, updated annually for each student receiving special education services, includes assessment data, learning goals, accommodations • Specially Designed Instruction: provided by SPED staff (e.g., individual, small group, tutorial) • Related Services: provided by specialists (e.g. physical therapy, speech/language, counseling, transportation)

Accommodation Modification Intervention

Differentiated Instruction is the teacher’s response to learners’ needs guided by principles of differentiation such as respectful tasks flexible grouping ongoing assessment & adjustment

WHAT CAN BE DIFFERENTIATED? CONTENT PROCESS PRODUCT According to students’ Learning Profile Readiness Interests

Math manipulatives Texts, e.g. novels at multiple reading levels Reading partners Tape recordings or videos of books Highlighted texts Web quests Curriculum compacting (TAG) Graphic organizers Reteaching Synopsis of unit Peer/adult mentors Scaffolding Independent study MODIFY ACCESS TO INSTRUCTIONAL CONTENT : same skills & concepts

Tiered activities or projects at different levels KWL Learning logs Journals with varied prompts Learning centers Literature circles Role playing Jigsaw Think-pair-share Model making Instructional strategies for “multiple learning modalities” Modify Process or activity by which learner makes sense of concepts or skills based on readiness, interest, learning style

Provide options for student choice Varied working arrangements Varied resources Varying degrees of difficulty Variety of assessments Differentiate timelines Use formative & summative evaluation Peer & self evaluation Develop rubrics with students Authentic audience Differentiate Product by which student demonstrates learning

Checklist for Group Work • Students understand task & expectation for each member • Task is interesting & matches instructional goals • Task requires genuine collaboration and important contribution from each member • Timelines are brisk. Students know what to do next. • “Way out for students who are not succeeding with the group • Opportunity for teacher/peer coaching & in-process quality checks

Curriculum is based on essential ideas & skills related to the discipline Curriculum is relevant, coherent, & connected Clear expectations for learning Instruction, activities, products focus on goals Lesson interests & engages learners Activities & products require higher level thinking & complex problem solving Students understand criteria for high quality work Classroom environment is respectful of each student & group as a whole Linking Quality Teaching & Differentiation.

Resources for Promoting Differentiation • Haager, D. & Klingner, J. (2005). Differentiating instruction in inclusive classrooms. Pearson • Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. ASCD • Tomlinson, C.A. & Allan,S.D. (2000) Leadership for differentiating schools and classrooms. ASCD • Tomlinson, C.A. (2001) How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. 2nd ed. ASCD • Tomlinson, C.A. & McTighe, J. (2006). Integrating differentiated instruction and understanding by design. ASCD

- More by User

Differentiated Instruction

Differentiated Instruction. Group Members : Marla Kemler Rachel Parrett Coleen Smith Joni Klopfenstein. Success breeds success . Kim Miller Michelle Olofsson Chrissy Sinn. Every child deserves a reasonable chance at success!. If a student is successful 1 time per day it carries over.

427 views • 20 slides

DIFFERENTIATED INSTRUCTION

443 views • 19 slides

Differentiated Instruction. Differentiation is responsive teaching rather than one-size-fits-all teaching. Tomlinson, C.A.,Teach Me Teach My Brain. 10% of what we READ 20% of what we HEAR 30% of what we SEE 50% of what we SEE & HEAR 70% of what is DISCUSSED with OTHERS

592 views • 21 slides

Grammar and Vocabulary Instruction for Diverse Learners

Grammar and Vocabulary Instruction for Diverse Learners. CATESOL 2012 College/University Level Workshop Jan Frodesen , UC Santa Barbara Margi Wald, UC Berkeley. Bennett, TESOL 2012: Good writing = Writing that meets expectations. Disciplines, courses, instructors

677 views • 52 slides

Differentiated Instruction. Language Arts Presentation and Workshop By Robin Knutelsky and Cara Russo May 23, 2013. On post-it notes answer the following questions : 1. What am I most passionate about? 2. What do I like to teach the most? How is this linked to my passion?

335 views • 15 slides

Differentiated Instruction. Blackboard Collaborate Communication Tools. Collaborate Tools. Sliders adjust mic and speaker volume Press to Talk and activate Video. Participant Tools: Emoticons Step Away Raise Hand Polling. Chat Tool. Participant Features Audio Setup Wizard.

451 views • 28 slides

Differentiated Instruction. Sarah Gavin & Wendy Gregg. Alston Middle School: 6 th – 7 th Grade Writing. Mission and Vision. Mission : Dorchester School District Two leading the way, every student, every day, through relationships, rigor, and relevance. .

562 views • 35 slides

Differentiated Instruction. “As we start a new school year, Mr. Smith, I just want you to know that I’m an Abstract-Sequential learner and trust that you’ll conduct yourself accordingly!”. Lisa Bruno Karla Skinner. What is Differentiated Instruction?. Teacher Assessment Tool.

384 views • 7 slides

DIFFERENTIATED INSTRUCTION. Belinda Chong Dawn Sng Hidaya Jermaine Vaness Quek. Definition.

991 views • 46 slides

Differentiated Instruction. English Year 3 The Rotterdam approach…. Karin Winkel Ton de Kraay . Rotterdam, 00 januari 2007. Start. Karin Winkel [email protected] http ://pabolicious.wordpress.com /. English JK II. Attendance Classroom language! Do’s and don’ts

360 views • 25 slides

Differentiated Instruction . What is your understanding of DI? http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/speced/learningforall2011.pdf http://www.edugains.ca/resourcesDI/EducatorsPackages/DIEducatorsPackage2010/2010EducatorsGuide.pdf.

345 views • 11 slides

Differentiated Instruction. A brief overview with practical application. How often is education “one size fits all?” Are there simple changes that we can make that can make our classrooms and our students more successful?. Using flexible means to reach defined ends.

399 views • 15 slides

Differentiated Instruction. What does it mean to differentiate instruction?. What reasons are there for differentiated instruction?. How did Lulu’s class differ from the modern classroom? Letting the children explore to learn Teacher still present to assist with learning

653 views • 25 slides

Learning Profile Pre-Assessment. Differentiated Instruction. Learning Profile Pre-Assessment. The following exercise can be used to group students according to their learning profiles. It is a great way to gain some insights into the interests of students and the way they learn.

433 views • 7 slides

Differentiated Instruction. By: Frank Oliva. Activity. Step 1 – Please read the article called Bull vs. Bear Step 2 – Prove that you understand the concepts of a Bull market by creating a political cartoon

837 views • 21 slides

Content, Process, and Product Conemaugh Valley School District. Differentiated Instruction. Differentiation. Is a teacher’s response to learner’s needs. Guided by general principles of differentiation. Respectful tasks. Formative assessment. Flexible grouping.

619 views • 40 slides

Differentiated Instruction for English Language Learners (ELLs)

Differentiated Instruction for English Language Learners (ELLs). Christopher Bell, Hong Duong, Sheryl Hoilette EDUC 4800 Action Research Project Georgia Gwinnet College School of Education Spring 2013. Introduction.

304 views • 10 slides

Differentiated Instruction. What It Is & How to Do It. What is differentiated instruction?. It’s a process through which teachers enhance learning by matching student characteristics to instruction and assessment

525 views • 15 slides

Differentiated Instruction. Helping Teachers with Assessment, Evaluation & Reporting. Setting the Stage for Learning. Before Learning Activity Each table has been given a specific task related to assessment. Instruction sheets have been provided for each activity.

922 views • 43 slides

Differentiated Instruction For English Language Learners

Differentiated Instruction For English Language Learners. By: Stephanie Merrick. What is an English Language Learner?. Students in your classroom whose primary language is not English. They may have recently moved to the United States, or just speak a different language at home. The Facts.

331 views • 7 slides

Differentiated Instruction. Presented by Laurenceau, Okafor, Ivery, Rice, Pokorny & Wagner. Not all students are alike. Some students have learning styles that are:. Visual – Spatial Bodily-Kinesthetic Musical Interpersonal Intra-personal Linguistic Logical – Mathematic

269 views • 22 slides

Differentiated Instruction. Mrs. Heidi Moya, M.Ed Education Professions & ELA Teacher Educators Rising Teacher Leader Mountain Ridge High School, Deer Valley Unified School District Contact me: [email protected]. What do you consider when shopping for jeans?.

526 views • 52 slides

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, what is differentiated instruction examples of how to differentiate instruction in the classroom.

Just as everyone has a unique fingerprint, every student has an individual learning style. Chances are, not all of your students grasp a subject in the same way or share the same level of ability. So how can you better deliver your lessons to reach everyone in class? Consider differentiated instruction—a method you may have heard about but haven’t explored, which is why you’re here. In this article, learn exactly what it means, how it works, and the pros and cons.

Definition of differentiated instruction

Carol Ann Tomlinson is a leader in the area of differentiated learning and professor of educational leadership, foundations, and policy at the University of Virginia. Tomlinson describes differentiated instruction as factoring students’ individual learning styles and levels of readiness first before designing a lesson plan. Research on the effectiveness of differentiation shows this method benefits a wide range of students, from those with learning disabilities to those who are considered high ability.

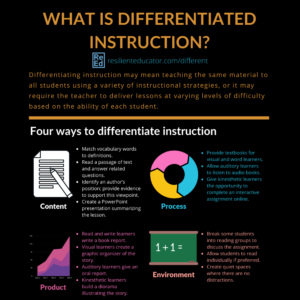

Differentiating instruction may mean teaching the same material to all students using a variety of instructional strategies, or it may require the teacher to deliver lessons at varying levels of difficulty based on the ability of each student.

Teachers who practice differentiation in the classroom may:

- Design lessons based on students’ learning styles.

- Group students by shared interest, topic, or ability for assignments.

- Assess students’ learning using formative assessment.

- Manage the classroom to create a safe and supportive environment.

- Continually assess and adjust lesson content to meet students’ needs.

History of differentiated instruction

The roots of differentiated instruction go all the way back to the days of the one-room schoolhouse, where one teacher had students of all ages in one classroom. As the educational system transitioned to grading schools, it was assumed that children of the same age learned similarly. However in 1912, achievement tests were introduced, and the scores revealed the gaps in student’s abilities within grade levels.

In 1975, Congress passed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), ensuring that children with disabilities had equal access to public education. To reach this student population, many educators used differentiated instruction strategies. Then came the passage of No Child Left Behind in 2000, which further encouraged differentiated and skill-based instruction—and that’s because it works. Research by educator Leslie Owen Wilson supports differentiating instruction within the classroom, finding that lecture is the least effective instructional strategy, with only 5 to 10 percent retention after 24 hours. Engaging in a discussion, practicing after exposure to content, and teaching others are much more effective ways to ensure learning retention.

Four ways to differentiate instruction

According to Tomlinson, teachers can differentiate instruction through four ways: 1) content, 2) process, 3) product, and 4) learning environment.

As you already know, fundamental lesson content should cover the standards of learning set by the school district or state educational standards. But some students in your class may be completely unfamiliar with the concepts in a lesson, some students may have partial mastery, and some students may already be familiar with the content before the lesson begins.

What you could do is differentiate the content by designing activities for groups of students that cover various levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (a classification of levels of intellectual behavior going from lower-order thinking skills to higher-order thinking skills). The six levels are: remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

Students who are unfamiliar with a lesson could be required to complete tasks on the lower levels: remembering and understanding. Students with some mastery could be asked to apply and analyze the content, and students who have high levels of mastery could be asked to complete tasks in the areas of evaluating and creating.

Examples of differentiating activities:

- Match vocabulary words to definitions.

- Read a passage of text and answer related questions.

- Think of a situation that happened to a character in the story and a different outcome.

- Differentiate fact from opinion in the story.

- Identify an author’s position and provide evidence to support this viewpoint.

- Create a PowerPoint presentation summarizing the lesson.

Each student has a preferred learning style, and successful differentiation includes delivering the material to each style: visual, auditory and kinesthetic, and through words. This process-related method also addresses the fact that not all students require the same amount of support from the teacher, and students could choose to work in pairs, small groups, or individually. And while some students may benefit from one-on-one interaction with you or the classroom aide, others may be able to progress by themselves. Teachers can enhance student learning by offering support based on individual needs.

Examples of differentiating the process:

- Provide textbooks for visual and word learners.

- Allow auditory learners to listen to audio books.

- Give kinesthetic learners the opportunity to complete an interactive assignment online.

The product is what the student creates at the end of the lesson to demonstrate the mastery of the content. This can be in the form of tests, projects, reports, or other activities. You could assign students to complete activities that show mastery of an educational concept in a way the student prefers, based on learning style.

Examples of differentiating the end product:

- Read and write learners write a book report.

- Visual learners create a graphic organizer of the story.

- Auditory learners give an oral report.

- Kinesthetic learners build a diorama illustrating the story.

4. Learning environment

The conditions for optimal learning include both physical and psychological elements. A flexible classroom layout is key, incorporating various types of furniture and arrangements to support both individual and group work. Psychologically speaking, teachers should use classroom management techniques that support a safe and supportive learning environment.

Examples of differentiating the environment:

- Break some students into reading groups to discuss the assignment.

- Allow students to read individually if preferred.

- Create quiet spaces where there are no distractions.

Pros and cons of differentiated instruction

The benefits of differentiation in the classroom are often accompanied by the drawback of an ever-increasing workload. Here are a few factors to keep in mind:

- Research shows differentiated instruction is effective for high-ability students as well as students with mild to severe disabilities.

- When students are given more options on how they can learn material, they take on more responsibility for their own learning.

- Students appear to be more engaged in learning, and there are reportedly fewer discipline problems in classrooms where teachers provide differentiated lessons.

- Differentiated instruction requires more work during lesson planning, and many teachers struggle to find the extra time in their schedule.

- The learning curve can be steep and some schools lack professional development resources.

- Critics argue there isn’t enough research to support the benefits of differentiated instruction outweighing the added prep time.

Differentiated instruction strategies

What differentiated instructional strategies can you use in your classroom? There are a set of methods that can be tailored and used across the different subjects. According to Kathy Perez (2019) and the Access Center those strategies are tiered assignments, choice boards, compacting, interest centers/groups, flexible grouping, and learning contracts. Tiered assignments are designed to teach the same skill but have the students create a different product to display their knowledge based on their comprehension skills. Choice boards allow students to choose what activity they would like to work on for a skill that the teacher chooses. On the board are usually options for the different learning styles; kinesthetic, visual, auditory, and tactile. Compacting allows the teacher to help students reach the next level in their learning when they have already mastered what is being taught to the class. To compact the teacher assesses the student’s level of knowledge, creates a plan for what they need to learn, excuses them from studying what they already know, and creates free time for them to practice an accelerated skill.

Interest centers or groups are a way to provide autonomy in student learning. Flexible grouping allows the groups to be more fluid based on the activity or topic. Finally, learning contracts are made between a student and teacher, laying out the teacher’s expectations for the necessary skills to be demonstrated and the assignments required components with the student putting down the methods they would like to use to complete the assignment. These contracts can allow students to use their preferred learning style, work at an ideal pace and encourages independence and planning skills. The following are strategies for some of the core subject based on these methods.

Differentiated instruction strategies for math

- Provide students with a choice board. They could have the options to learn about probability by playing a game with a peer, watching a video, reading the textbook, or working out problems on a worksheet.

- Teach mini lessons to individuals or groups of students who didn’t grasp the concept you were teaching during the large group lesson. This also lends time for compacting activities for those who have mastered the subject.

- Use manipulatives, especially with students that have more difficulty grasping a concept.

- Have students that have already mastered the subject matter create notes for students that are still learning.

- For students that have mastered the lesson being taught, require them to give in-depth, step-by-step explanation of their solution process, while not being rigid about the process with students who are still learning the basics of a concept if they arrive at the correct answer.

Differentiated instruction strategies for science

- Emma McCrea (2019) suggests setting up “Help Stations,” where peers assist each other. Those that have more knowledge of the subject will be able to teach those that are struggling as an extension activity and those that are struggling will receive.

- Set up a “question and answer” session during which learners can ask the teacher or their peers questions, in order to fill in knowledge gaps before attempting the experiment.

- Create a visual word wall. Use pictures and corresponding labels to help students remember terms.

- Set up interest centers. When learning about dinosaurs you might have an “excavation” center, a reading center, a dinosaur art project that focuses on their anatomy, and a video center.

- Provide content learning in various formats such as showing a video about dinosaurs, handing out a worksheet with pictures of dinosaurs and labels, and providing a fill-in-the-blank work sheet with interesting dinosaur facts.

Differentiated instruction strategies for ELL

- ASCD (2012) writes that all teachers need to become language teachers so that the content they are teaching the classroom can be conveyed to the students whose first language is not English.

- Start by providing the information in the language that the student speaks then pairing it with a limited amount of the corresponding vocabulary in English.

- Although ELL need a limited amount of new vocabulary to memorize, they need to be exposed to as much of the English language as possible. This means that when teaching, the teacher needs to focus on verbs and adjectives related to the topic as well.

- Group work is important. This way they are exposed to more of the language. They should, however, be grouped with other ELL if possible as well as given tasks within the group that are within their reach such as drawing or researching.

Differentiated instruction strategies for reading

- Tiered assignments can be used in reading to allow the students to show what they have learned at a level that suites them. One student might create a visual story board while another student might write a book report.

- Reading groups can pick a book based on interest or be assigned based on reading level

- Erin Lynch (2020) suggest that teachers scaffold instruction by giving clear explicit explanations with visuals. Verbally and visually explain the topic. Use anchor charts, drawings, diagrams, and reference guides to foster a clearer understanding. If applicable, provide a video clip for students to watch.

- Utilize flexible grouping. Students might be in one group for phonics based on their assessed level but choose to be in another group for reading because they are more interested in that book.

Differentiated instruction strategies for writing

- Hold writing conferences with your students either individually or in small groups. Talk with them throughout the writing process starting with their topic and moving through grammar, composition, and editing.

- Allow students to choose their writing topics. When the topic is of interest, they will likely put more effort into the assignment and therefore learn more.

- Keep track of and assess student’s writing progress continually throughout the year. You can do this using a journal or a checklist. This will allow you to give individualized instruction.

- Hand out graphic organizers to help students outline their writing. Try fill-in-the-blank notes that guide the students through each step of the writing process for those who need additional assistance.

- For primary grades give out lined paper instead of a journal. You can also give out differing amounts of lines based on ability level. For those who are excelling at writing give them more lines or pages to encourage them to write more. For those that are still in the beginning stages of writing, give them less lines so that they do not feel overwhelmed.

Differentiated instruction strategies for special education

- Use a multi-sensory approach. Get all five senses involved in your lessons, including taste and smell!

- Use flexible grouping to create partnerships and teach students how to work collaboratively on tasks. Create partnerships where the students are of equal ability, partnerships where once the student will be challenged by their partner and another time they will be pushing and challenging their partner.

- Assistive technology is often an important component of differential instruction in special education. Provide the students that need them with screen readers, personal tablets for communication, and voice recognition software.

- The article Differentiation & LR Information for SAS Teachers suggests teachers be flexible when giving assessments “Posters, models, performances, and drawings can show what they have learned in a way that reflects their personal strengths”. You can test for knowledge using rubrics instead of multiple-choice questions, or even build a portfolio of student work. You could also have them answer questions orally.

- Utilize explicit modeling. Whether its notetaking, problem solving in math, or making a sandwich in home living, special needs students often require a step-by-step guide to make connections.

References and resources

- https://www.thoughtco.com/differentiation-instruction-in-special-education-3111026

- https://sites.google.com/site/lrtsas/differentiation/differentiation-techniques-for-special-education

- https://www.solutiontree.com/blog/differentiated-reading-instruction/

- https://www.readingrockets.org/article/differentiated-instruction-reading

- https://www.sadlier.com/school/ela-blog/13-ideas-for-differentiated-reading-instruction-in-the-elementary-classroom

- https://inservice.ascd.org/seven-strategies-for-differentiating-instruction-for-english-learners/

- https://www.cambridge.org/us/education/blog/2019/11/13/three-approaches-differentiation-primary-science/

- https://www.brevardschools.org/site/handlers/filedownload.ashx?moduleinstanceid=6174&dataid=8255&FileName=Differentiated_Instruction_in_Secondary_Mathematics.pdf

Books & Videos about differentiated instruction by Carol Ann Tomlinson and others

- The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners, 2nd Edition

- Leading and Managing a Differentiated Classroom – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Marcia B. Imbeau

- The Differentiated School: Making Revolutionary Changes in Teaching and Learning – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Kay Brimijoin, and Lane Narvaez

- Integrating Differentiated Instruction and Understanding by Design: Connecting Content and Kids – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Jay McTighe

- Differentiation in Practice Grades K-5: A Resource Guide for Differentiating Curriculum – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Caroline Cunningham Eidson

- Differentiation in Practice Grades 5–9: A Resource Guide for Differentiating Curriculum – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Caroline Cunningham Eidson

- Differentiation in Practice Grades 9–12: A Resource Guide for Differentiating Curriculum – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Cindy A. Strickland

- Fulfilling the Promise of the Differentiated Classroom: Strategies and Tools for Responsive Teaching – Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Leadership for Differentiating Schools and Classrooms – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Susan Demirsky Allan

- How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms, 3rd Edition by Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Assessment and Student Success in a Differentiated Classroom by Carol Ann Tomlinson and Tonya R. Moon

- How To Differentiate Instruction In Mixed Ability Classrooms 2nd Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson

- How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms 3rd Edition by Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Assessment and Student Success in a Differentiated Classroom Paperback – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Tonya R. Moon

- Leading and Managing a Differentiated Classroom (Professional Development) 1st Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Marcia B. Imbeau

- The Differentiated School: Making Revolutionary Changes in Teaching and Learning 1st Edition by Carol Ann Tomlinson, Kay Brimijoin, Lane Narvaez

- Differentiation and the Brain: How Neuroscience Supports the Learner-Friendly Classroom – David A. Sousa, Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Leading for Differentiation: Growing Teachers Who Grow Kids – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Michael Murphy

- An Educator’s Guide to Differentiating Instruction. 10th Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson, James M. Cooper

- A Differentiated Approach to the Common Core: How do I help a broad range of learners succeed with a challenging curriculum? – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Marcia B. Imbeau

- Managing a Differentiated Classroom: A Practical Guide – Carol Tomlinson, Marcia Imbeau

- Differentiating Instruction for Mixed-Ability Classrooms: An ASCD Professional Inquiry Kit Pck Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Using Differentiated Classroom Assessment to Enhance Student Learning (Student Assessment for Educators) 1st Edition – Tonya R. Moon, Catherine M. Brighton, Carol A. Tomlinson

- The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners 1st Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson

You may also like to read

- Creative Academic Instruction: Music Resources for the Classroom

- How Teachers Use Student Data to Improve Instruction

- Advice on Positive Classroom Management that Works

- Five Skills Online Teachers Need for Classroom Instruction

- 3 Examples of Effective Classroom Management

- Advice on Improving your Elementary Math Instruction

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Curriculum and Instruction , Diversity , Engaging Activities , New Teacher , Pros and Cons

- Certificates in Administrative Leadership

- Trauma-Informed Practices in School: Teaching...

- Certificates for Reading Specialist

These languages are provided via eTranslation, the European Commission's machine translation service.

- slovenščina

- Azerbaijani

Differentiated Instruction: Inclusive Strategies for Successful Learning

Participants will be enlightened on the adaptability and variety of individual student needs. They will show that differentiated learning and assessment strategies are specifically based on the understanding and promotion of five key areas. They will learn to design tailored lesson plans and build a positive learning environment with differentiated content.

Description

- --> Read the full course description and tentative schedule <--

- Understanding students' interests and inclinations;

- Using differentiated content;

- Understanding individual learning processes;

- Activities to promote collaboration in the classroom;

- Differentiated assessment strategies.

Learning objectives

- Understand differentiated learning methods;

- Connect the interest of students with different school subjects;

- Design differentiated lesson plans;

- Develop innovative assessment strategies;

- Design an inclusive classroom;

- Reflect on core competencies for continuing education;

- Foster inclusive behaviors at school.

Methodology & assessment

Certification details.

- Certificate of Attendance: Upon successful completion of your course, you will receive a Certificate of Attendance in line with Erasmus quality standards.

- Europass Mobility Certificate : If requested, you can also receive the Europass Mobility Certificate.

- Seamless Administration : We provide assistance and guidance to our participants throughout every step of the project: from the grant application to the final documents.

- Live Chat support : Monday-Friday | 8:30-22:30 CET

- Guides to Erasmus+

- OID Numbers and Fiscal Data

Pricing, packages and other information

- Price: 480 Euro

- Package contents: Course

Additional information

- Language: English

- Target audience ISCED: Primary education (ISCED 1) Lower secondary education (ISCED 2) Upper secondary education (ISCED 3)

- Target audience type: Teacher Head Teacher / Principal Pedagogical Adviser

- Learning time: 25 hours or more

Upcoming sessions

Key competences

More courses by this organiser.

Project-Based Learning (PBL): Make Students’ Learning Real and Effective!

Next upcoming session 06.05.2024 - 11.05.2024

3D Printing and Modeling: an Introduction for Schoolteachers

From CLIL to Translanguaging: Strategies to Integrate Migrants

- Future Students

- Current Students

- International Students

- Community Members

Candidate presentation: Differentiated Instruction and Inclusive Education

The Faculty of Education invites members of the campus community – students, faculty, and staff – to attend a public presentation on “What is the most critical issue in inclusive education?” by Elizabeth Blake, candidate for a tenure-track position in Differentiated Instruction and Inclusive Education. The presentation takes place from 9:00--10:00 am on May 1 in Memorial Hall 417.

This will be a hybrid presentation, and a Zoom link will be available as follows:

https://upei.zoom.us/j/63889368981?pwd=ZDNVTUlxVkxwWTlxd016Sk9CUlg1dz09

Meeting ID: 638 8936 8981

Passcode: 037280

For further information, contact Karen-Anne O’Halloran.

- Academic Calendar

- MyUPEI | Campus Login

- Staff and Faculty Lookup

- Study Abroad

- Explore the Campus

- Crisis Centre

- Athletics and Recreation

- Faculties and Schools

- Conference Services

- Health and Wellness

- Sexual Violence Prevention and Response Office

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Differentiation can include complex strategies, like writing tiered lesson plans, or it can take a more simplistic form, such as using reading buddies or think-pair-share strategies. Here is a condensed list of the continuum of differentiated strategies. Higher Prep Strategies. Lower Prep Strategies. Tiered Lessons.

7. Content Examples of differentiating content: 1. Using reading materials at varying readability levels; 2. Putting text materials on tape; 3. Using spelling or vocabulary lists at readiness levels of students; 4. Presenting ideas through both auditory and visual means; 5. Using reading buddies; and 6.

Erin Waltman. This document provides information about inclusive education practices and differentiated instruction strategies. It discusses full inclusion and partial inclusion models. It also outlines characteristics of evidence-based inclusive schools like diversity, formal and natural supports, age-appropriate classrooms, access to general ...

Differentiated Instruction : • Is valuable at every level and subject area • Helps students become successful learners • Stretches students in the learning process. Mrs. Jones Activity • Read through Sample Lesson 1 and 2 • Answer the questions that follow each lesson • Be ready to discuss your findings.

An appropriate data collection and monitoring mechanism is needed to reach out to the children concerned, understand exclusion experiences, provide inclusive education, and improve policy and planning for persons with disabilities. There is also a lack of qualified teachers to implement inclusive education efficiently.

Based on the literature, the researcher should expect to find general education. teacher's perceptions of differentiated instruction, how they practice (DI) and the supports. necessary for effective (DI) in the inclusionary class. The idea of differentiated instruction is to develop a cohesive system that reinforces.

Differentiated Instruction (DI) has been promoted as a model to facilitate more inclusive classrooms by addressing individual learning needs and maximizing learning opportunities (Gheyssens et al., 2020c).DI aims to establish maximal learning opportunities by differentiating the instruction in terms of content, process, and product in accordance with students their readiness, interests and ...

Differentiated Instruction for Inclusive Teaching - Free download as Powerpoint Presentation (.ppt), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or view presentation slides online. Teacher training seminar on differentiated instruction.

Differentiated Instruction 101 Clare Kilbane, Ph. D. ... 84-85. Thinking about Students with Disabilities 96% of general education teachers have students with disabilities in their classrooms. On average, there are at least 3-4 students with IEPs integrated into each general education class. ... Not just inclusion but inclusive teaching ...

inclusive education & differentiated instruction 9 has been determined, is a supportive and communal atmosphere where all "students are educated in general education classrooms with their peers to the greatest extent possible" (Chriss Walther-

Differentiated instruction Differentiated Instruction involves responding effectively to the differences that exist among learners in the classroom. According to Tomlinson (2001), teachers differentiate when they reach out to an individual or small group by varying their teaching in order to create the best learning experience possible.

1. Introduction. With the ever-growing diversity within the student population, policymakers and researchers urge teachers to embrace diversity by means of differentiated instruction (DI) (UNESCO, Citation 2017).Given that teachers are a determining factor when it comes to the implementation of DI, research has focused on investigating variables that support teachers' instructional behaviors ...

Resources. Differentiated Instruction:. Meeting the Instructional Needs Of Diverse Classrooms. presented by Dr. Abraham H. Jones NEA Resource Cadre Member. Note of Appreciation to . Deborah E Burns, Curriculum Coordinator, Cheshire Connecticut Public Schools Slideshow 146050 by Patman.

In an 'inclusive classroom', there are no barriers to learning. Each student brings their own needs and strengths. In our daily research, we are told that it is a particular challenge to teachers to differentiate for those needs. We brought together science and humanities specialists - University Senior Lecturer in Science Education, Dr ...

Presentation Transcript. Differentiated Instruction for Diverse Learners Gayle Y. Thieman, Ed.D. Portland State University. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act I.D.E.A. • 1975 PL 94-142 to ensure all children with disabilities have free appropriate public education with special education services to meet unique needs; provided federal ...

According to Tomlinson, teachers can differentiate instruction through four ways: 1) content, 2) process, 3) product, and 4) learning environment. 1. Content. As you already know, fundamental lesson content should cover the standards of learning set by the school district or state educational standards.

Differentiated instruction is a technique that teachers use to accommodate each student's learning style and instructional preferences. This strategy may involve teaching the same material to all students using a variety of instructional methods, or ... Keywords: Inclusive education, differentiated instruction, learning style, content ...