Kantian Ethics

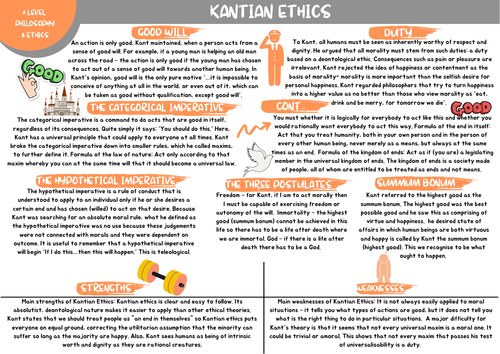

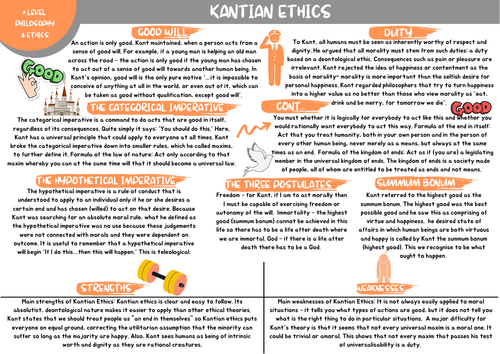

Immanuel Kant, a German philosopher from the Enlightenment period, is the father of Kantian ethics. These deontological principles, also referred to as duty ethics, emphasise the process (or duty) behind actions rather than their outcomes.

Central to Kantian ethics are three formulations of the Categorical Imperative, which is an absolute command that has no exceptions and does not depend on one’s desires.

First formulation (Universalizability): “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” This entails that if your action’s maxim (the principle behind the action) can be logically applied universally, then it is considered morally correct.

Second formulation (Humanity as an end in themselves): “Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.” Kant argues that every human has an intrinsic worth and should not be exploited for one’s aim.

Third formulation (Autonomy and the Kingdom of Ends): “Every rational being must act as if he were through his maxim always a legislating member in the universal kingdom of ends.” This means that one should behave as if their actions set the laws in a perfect moral kingdom.

Kant differentiates between hypothetical imperatives, which provide instructions for achieving a specific outcome (if you want X, do Y), and categorical imperatives that denote moral obligations (you must do Y).

Kant’s theory is based on the principle of rationality. Kant believed that through a process of rational thought, individuals can discern moral laws and duties.

The concept of “good will” is also critical to understanding Kantian ethics. For Kant, a good will is the only thing that is good without qualification – it is good regardless of its outcomes.

Critics of Kantian ethics argue that his moral laws are too rigid, and situations may arise where a strict application of the Categorical Imperative would result in a morally reprehensible outcome. Critics also argue that Kant’s emphasis on rationality doesn’t account sufficiently for elements of human emotion and empathy.

Kantian ethics reject consequentialist theories, like Utilitarianism, which suggests that the moral worth of an act is determined by its outcome. In contrast, Kantian ethics argue that morality’s value lies within the act itself.

Kant also proposed the idea of a “moral agent,” someone capable of rational decision-making and hence responsible for their actions. He believed that all adult humans are moral agents capable of determining the right course of action based on pure reason.

Essay: Kantian ethics are helpful for moral decision-making

September 22, 2020.

‘Kantian ethics are helpful for moral decision-making in every kind of context.’ Discuss

On one hand, I do not think that Kantian ethics is helpful with every decision. This is because all situations are different and are not the same so it cannot be universal. Kant’s theology was based on very ‘black and white terms’ this sort of phrase should be avoided as it’s not very clear what it means, he focused on the moral act of a situation and ignored the consequences that could be a result of that act. His theology also was based on the idea of Maxims. Maxims are moral rules that are determined by reason. He believed that everyone has reason and so if we all had reason then this makes us all the same, meaning that we all should be making the same moral decisions. An example of a maxim that Kant introduced was that ‘lying is wrong and we should focus on always telling the absolute truth.’ However, a flaw to this theory is when it is put into context, it contradicts itself. For example, the situation with the man and the axe. A murder with an axe in his hand has turned up to your house and he is asking you ‘where is your mother I am going to kill her?’ In this situation, Kant would say that you should tell the truth of where the mother is, regardless of the consequences (mother would die). I think that the maxims that Kant put in place aren’t specific enough to each situation because every situation is unique. Universal rules aren’t helpful in the real world because every situation is different. There are never two situations that are the same. Therefore, the theory should be relativist and not absolutist. Overall, I think that Kantian ethics should not be applied when making every moral decision because it doesn’t take into consideration the situation that the individual is in, therefore it isn’t universal because the rules are too set in stone.

Phew! We have a number of excellent points here but as a writing tactic it’s not a good idea ot have an opening paragraph that tries to say so much. Why not just say ‘there are three reasons why Kant’s ethics is unworkable. Then spell out the three reasons in a subsequent paragraph structure.

On the counter side, Kantian ethics is reliable in some circumstances. It relies on a system of rules which is very clear cut, meaning that everyone is aware of the obligations. Yes, but you need to show me how Kant produces the rule in the first place! By a priori reason.If you allowed everyone to break the rules, then the consequences of the legal system would be a mess. No one would know what they ought to do. For example, in order for everyone to do their duty, it must be able to be universalised. In other words, the individual has to think to themselves “can I apply this to all situations/ circumstances?” To put this in context, making a lying promise about loaning some money. i.e. if you promise to take a loan of money out with the intention that you will not be able to pay the company back in the time that has been given, the promise contradicts the act of keeping a promise. Yes, technically he calls this a perfect duty because it is logically contradictory to break the rule of promising Kant would view this as it being morally wrong to make a lying promise and so would advise people not to take a loan out because one may not be able to guarantee that they can pay the company that leant the money back. This therefore supported Kant’s idea that lying contradicts itself. This is the obvious place for a paragraph break However, on the other hand others may argue that Kant’s theology is inflexible. It should be able to break an unhelpful rule if the individual circumstances mean that that is the right thing to do. For example, going back to talking about the example with making a lying promise. In some situations, a person may want to take out a loan and would be able to pay the money back and so they may not be able to because of universal moral laws that have been put in place which say that this is wrong. Therefore, I think that this is unrealistic because Kant asks us to follow maxims, but sometimes just because some people act in one way doesn’t mean that others will. Just like the person who will take out a loan even though they know that they will not be able to pay the money back. Overall, I think that Kantian ethics are helpful for moral decision-making in some contexts because it is so clear that a child could understand what they should and should not do . This means that no one can act in a selfish way and so would promote a happier environment.

This paragraph has some good analytical and evaluative points mixed in. however, the paragraph is still rather long.

Another strength in Kant’s theory that is helpful for moral decision-making is that his theory supports all equality and justice. In other words, Kant’s theory provides a basis for Human rights. In 1948, UN Declaration of Human rights was agreed by 48 countries and is the world’s most translated document, protecting humans around the globe. This means that the theory provides the foundations for modern conceptions of equality and justice and suggests that no one can be used for being a different race, culture or religion. It also suggests that everyone is of equal worth and that no one is of a higher value of another individual. This as a result would reduce the chances of social unsettlement and minimise the amount of prejudice that is happening in the modern day. However, this is not always the case. For example, in today’s world prejudice and discrimination is still happening in some countries even though there are moral laws in place which say that this is not acceptable. And so, even though there are laws in place, it doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone is going to abide by the rules. This therefore means that an unrealistically high standard is set which some people are not adhering to which was always going to be the case otherwise there would be no need for moral laws to be put in place. To conclude this, I still think that Kantian ethics is helpful for some moral decision-making but not in every kind of context. My reason for this I because not everyone makes moral decisions and it cannot be universalised because the rules are not universal in all situations and so it is unrealistic.

Plenty of good material here showing signs of the potential to be a top grade candidate. This candidate will be hitting A* when he or she learns to structure an argument more coherently, by separating points into a slightly more logical structure of thought rather than trying to say everything at once. The opening and closing paragraphs need to be worked on – indeed – the idea of a paragraph itself doesn’t seem to be grasped. Underlying this there is an acute mind, however, and I particularly like the way different points are grounded in practical examples. An exciting prospect!

Grade A potential but…

Total 30/40 75% B, almost A

AO1 13 marks

A very good demonstration of knowledge and understanding in response to the question:

focuses on the precise question throughout

very good selection of relevant material which is used appropriately

accurate, and detailed knowledge which demonstrates very good understanding through either the breadth or depth of material used

accurate and appropriate use of technical terms and subject vocabulary.

a very good range of scholarly views, academic approaches, and/or sources of wisdom and authority are used to demonstrate knowledge and understanding

AO2 17 marks

A very good demonstration of analysis and evaluation in response to the question:

clear argument which is mostly successful

successful and clear analysis and evaluation

views very well stated, coherently developed and justified

answers the question set competently

a very good range of scholarly views, academic approaches and sources of wisdom and authority used to support analysis and evaluation

Assessment of Extended Response: There is a well–developed and sustained line of reasoning which is coherent, relevant and logically structured work on this a bit more

Study with us

Practise Questions 2020

Religious Studies Guides – 2020

Check out our great books in the Shop

Leave a Reply Cancel

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Introduction to Kantian Ethics & Duty

Kant's deontological theory on duty.

Immanuel Kant looked at moral statements and how we use them. His deontological theory looks at how an action brings about a duty as opposed to utilitarianism, which is consequence-focussed.

The importance of reason

- Kant felt reason played a big part in how humans make moral decisions. So he centred his theory on the idea of reasoning from goodwill and duty.

Moral vs everyday statements

- Moral statements are a priori synthetic as they can be understood without any experience, but followed up and evidenced with experience.

- Everyday statements are most typically known through a person's experience and then verified by the experience of that person using this evidence to support the statement.

Kant's theory on good will

- Kant focussed on the idea of goodwill and its relationship with duty.

- For example, an action would not be deemed good if it was done to make somebody feel or look good.

Kant's definition of duty

- Kant’s definition of duty is to act morally and follow the rules that have been set out for you.

- When you combine good will and duty, you get a moral action.

- Kant’s former statements on reason come into play here. Kant felt every decision should be made by reason; based on the good will and the duty you have.

- A decision should not be based on feelings or personal opinions. It should simply be based upon reasoning conforming to goodwill and duty.

1 Philosophy of Religion

1.1 Ancient Philosophical Influences: Plato

1.1.1 Plato's Understanding of Reality

1.1.2 Plato's Theory of Forms

1.1.3 Plato's Analogy of the Cave

1.1.4 The Purpose of Plato's Analogy of the Cave

1.1.5 Evaluation of Plato's Theories

1.2 Ancient Philosophical Influences: Aristotle

1.2.1 Aristotle's Understanding of Reality

1.2.2 Aristotle's Four Causes

1.2.3 Aristotle's Prime Mover

1.3 Ancient Philosophical Influences: Soul, Mind, Body

1.3.1 Plato & Aristotle's Views of the Soul

1.3.2 Metaphysics of Consciousness

1.3.3 Materialism - Ryle’s Philosophical Behaviourism

1.3.4 Materialism - Identity Theory

1.4 The Existence of God - Arguments from Observation

1.4.1 The Teleological Argument - Aquinas' Fifth Way

1.4.2 The Teleological Argument - Paley & Evolution

1.4.3 The Cosmological Argument

1.4.4 Hume's Criticisms: Teleological & Cosmological

1.5 The Existence of God - Arguments from Reason

1.5.1 The Ontological Argument

1.5.2 Criticisms of the Ontological Argument

1.6 Religious Experience

1.6.1 Introduction to Religious Experience

1.6.2 Mystical Experience

1.6.3 Conversion Experience

1.6.4 Understanding Religious Experience

1.6.5 Issues Relating to Religious Experience - Validity

1.6.6 Issues Relating to Religious Experiences - People

1.7 The Problem of Evil

1.7.1 Presentations of the Problems of Evil

1.7.2 Discussion Points -

1.8 The Nature & Attributes of God

1.8.1 Omnipotence

1.8.2 Omniscience

1.8.3 Boethius - Divine Knowledge, Free Will & Eternity

1.8.4 (Omni)benevolence

1.8.5 Eternity & Free Will

1.9 Religious Language: Negative, Analogical, Symbolic

1.9.1 Apophatic & Cataphatic Way

1.9.2 Symbol

1.9.3 Discussion Points: Religious Language

1.10 Religious Language: 20th Century Perspective

1.10.1 Logical Positivism & Verification Principle

1.10.2 Wittgenstein

1.10.3 Falsification Symposium: Flew & Hare

1.10.4 Falsification Symposium: Mitchell

1.10.5 Discussion Points: Verification & Falsification

1.10.6 Discussion Points: Aquinas vs Wittgenstein

2 Religion & Ethics

2.1 Natural Law

2.1.1 St Thomas Aquinas - Telos & Four Tiers of Law

2.1.2 St Thomas Aquinas - Precepts

2.1.3 St Thomas Aquinas - Real & Apparent Goods

2.1.4 Discussion Points - Natural Law & Doing Good

2.1.5 Discussion Points - Telos & Double Effect Doctrine

2.2 Situation Ethics

2.2.1 Fletcher's Situation Ethics

2.2.2 Fletcher's Concept of Conscience

2.2.3 Discussion Points: Moral Decision-Making

2.2.4 Discussion Points - Agape

2.3 Kantian Ethics

2.3.1 Introduction to Kantian Ethics & Duty

2.3.2 Hypothetical & Categorical Imperative

2.3.3 Summum Bonum & Three Postulates

2.3.4 Discussion Points: Kantian Ethics

2.4 Utilitarianism

2.4.1 The Utility Principle

2.4.2 Act & Rule Utilitarianism

2.4.3 Discussion Points: Utilitarianism

2.5 Euthanasia

2.5.1 Key Concepts for Euthanasia Debates

2.5.2 Discussion Points: Natural Law & Situation Ethics

2.5.3 Discussion Points: Sanctity of Life

2.5.4 Discussion Points: Autonomy & Medical Intervention

2.6 Business Ethics

2.6.1 Corporate Social Responsibility & Whistle-Blowing

2.6.2 Good Ethics & Globalisation

2.6.3 Discussion Points: Utilitarianism & Kantian Ethics

2.6.4 Discussion Points: CSR, Globalisation & Capitalism

3 Developments in Christian Thought

3.1 Saint Augustine's Teachings

3.1.1 Human Nature

3.1.2 Original Sin & God's Grace

3.2 Death & the Afterlife

3.2.1 Heaven, Hell, & Purgatory

3.2.2 Different Interpretations of the Afterlife

3.2.3 Election

3.2.4 The Final Judgement

3.2.5 Discussion Points: Heaven, Hell & Purgatory

3.3 Knowledge of God's Existence

3.3.1 Natural Knowledge

3.3.2 Revealed Knowledge in Faith, Grace, & Jesus Christ

3.3.3 Revealed Knowledge in the Bible & Church

3.3.4 Discussion Points: Reason & Belief in God

3.3.5 Discussion Points: The Fall & Trust in God

3.4 The Person of Jesus Christ

3.4.1 Jesus Christ’s Authority as the Son of God

3.4.2 Jesus Christ’s Authority as a Teacher of Wisdom

3.4.3 Jesus Christ’s Authority as a Liberator

3.5 Christian Moral Principles

3.5.1 The Bible & Love

3.5.2 Bible, Church & Reason

3.5.3 Discussion Points: Christian Ethics

3.5.4 Discussion Points: Love & the Bible

3.6 Christian Moral Action

3.6.1 Dietrich Bonhoeffer & the Confessing Church

3.6.2 Bonhoeffer & Civil Disobedience

3.6.3 Bonhoeffer's Teaching on Ethics as Action

3.6.4 Discussion Points: Civil Disobedience & Bonhoeffer

3.7 Development - Pluralism & Theology

3.7.1 Pluralism & Theology: Exclusivism & Inclusivism

3.7.2 Pluralism & Theology: Pluralism

3.7.3 Discussion Points: Salvation

3.7.4 Discussion Points: Pluralism Undermining Beliefs

3.8 Development - Pluralism & Society

3.8.1 Development of Multi-Faith Societies

3.8.2 Responses to Inter-Faith Dialogue

3.8.3 The Scriptural Reasoning Movement

3.8.4 Discussion Points: Social Cohesion & Scripture

3.8.5 Discussion Points: Conversion

3.9 Gender & Society

3.9.1 Waves of Feminism

3.9.2 Traditional Christian Views on Gender Roles

3.9.3 Christian Views on Gender Roles & Family

3.9.4 Discussion Points: Secular Views of Gender

3.9.5 Discussion Points: Motherhood & Family

3.10 Gender & Theology

3.10.1 Rosemary Radford Ruether

3.10.2 Mary Daly

3.10.3 Discussion Points: Ruether & Daly

3.10.4 Discussion Points: Male Saviour & Female God

3.11 Challenges

3.11.1 Secularism - Sigmund Freud

3.11.2 Secularism - Richard Dawkins

3.11.3 Christianity & Public Life

3.11.4 Discussion Points: Spiritual Values

3.11.5 Discussion Points: Social Values & Opportunities

3.11.6 Karl Marx

3.11.7 Liberation Theology

Jump to other topics

Unlock your full potential with GoStudent tutoring

Affordable 1:1 tutoring from the comfort of your home

Tutors are matched to your specific learning needs

30+ school subjects covered

Discussion Points - Agape

Hypothetical & Categorical Imperative

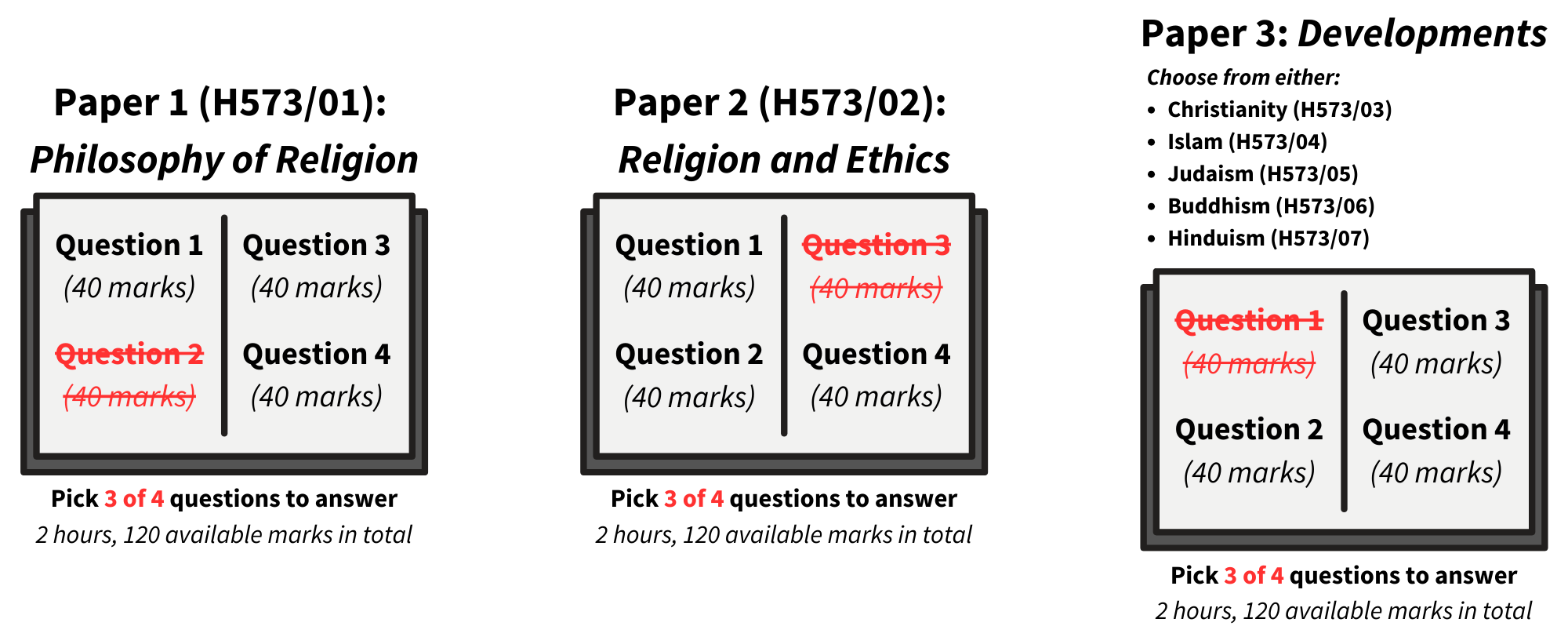

OCR Religious Studies – Religion and Ethics

The Religion and Ethics exam paper in OCR A Level Religious Studies (H573/02) contains essay questions on the following topics:

- Religious approaches to ethics (including natural law and situation ethics )

- Normative ethical theories (including deontological ethics and utilitarianism )

- Applied ethics (in particular the issues of euthanasia and business ethics )

- Sexual ethics (including premarital sex , extramarital sex , and homosexuality )

- Metaethics (including naturalism , intuitionism , and emotivism )

- Conscience (including the views of Aquinas and Freud )

Religious approaches to ethics

Ethics is about what is morally good and bad, right and wrong. And so, religious approaches to ethics say morality is grounded in religious teachings and God:

- Aquinas argues that what is good and right is for things to achieve their purpose as determined by (God’s) natural law.

- Fletcher argues that what is good and right is to act in the most loving way according to the specific details of the situation.

Natural law (Aquinas)

St. Thomas Aquinas’ approach to ethics is heavily influenced by the ideas of Aristotle covered in the philosophy of religion topic . Like Aristotle, Aquinas believes in a natural law that things have an inherent nature and an inherent purpose/telos/final end . According to this natural law, good means something achieves its telos, whereas bad means something doesn’t achieve its telos. For both Aristotle and Aquinas, the telos of humans is eudaimonia – although they have slightly different interpretations of what this means.

The word telos roughly translates to purpose . And according to natural law, what is good is for something to act in accordance with its nature to achieve its telos. A good chair , for example, achieves its telos of providing a comfortable place to sit. A good tennis player achieves the telos of winning tennis matches.

Both Aristotle and Aquinas saw the unique nature of human beings as rationality – the ability to use reason. It is this nature that makes humans different from all other things – animals, plants, chairs, etc. A good human being is one that acts in accordance with this nature and chooses their actions rationally. By doing so, they will achieve their telos.

For both Aristotle and Aquinas, the telos of human beings is eudaimonia. For Aristotle, eudaimonia means a good life achieved by acting virtuously (see the AQA philosophy notes for more detail on eudaimonia) , whereas Aquinas puts a Christian spin on this idea. For Aquinas, eudaimonia means glorifying God by acting virtuously and, ultimately, achieving union with God.

So, in summary, ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are a matter of natural law for Aquinas:

- God created an orderly world with natural laws where everything has a telos .

- According to this natural law, what’s good is for things to fulfil their telos. What’s bad is for things not to fulfil their telos.

- ( This is what conscience is for Aquinas )

- By using this capacity for reason, we can choose our actions in accordance with natural law and achieve our telos of eudaimonia (i.e. we’ll have a good life).

- If humans disobey natural law and God’s plan, they won’t achieve their telos of eudaimonia (i.e. they’ll have a bad life).

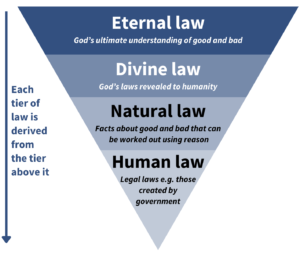

4 tiers of law

- Eternal law: God’s divine plan – i.e. God’s ultimate understanding of good and bad as decided by His omnipotence and omnibenevolence.

- Divine law: God’s laws as directly communicated to people – i.e. instances where God has explicitly revealed His laws to humanity. For example, in the Bible.

- Natural law: What is good and bad for human beings as can be worked out using reason regardless of whether a person has knowledge of the Bible/divine law.

- Human law: The laws of societies created by humans/governments. These laws should be derived from natural laws.

Each tier of law is determined by the tier above it. For example, the 10 Commandments revealed to Moses (an example of divine law) are a subset of God’s eternal law. Because of this hierarchy, Aquinas believes governments should derive the laws of society from natural laws. If a human law goes against a natural law, we shouldn’t follow the human law because the natural law is higher up in the hierarchy. In other words, it may be illegal to break such a natural law, but it would not be immoral (i.e. morally wrong).

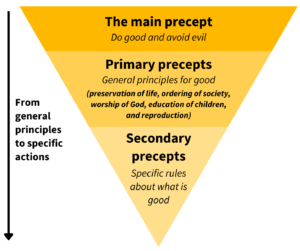

The precepts

A precept is like a moral rule. According to Aquinas, the main precept is simply: To do good and avoid evil.

“Hence this is the first precept of law, that “good is to be done and pursued, and evil is to be avoided.” All other precepts of the natural law are based upon this.” – Aquinas, Summa Theologica , First Part of the Second Part Question 94

(this main precept is sometimes referred to as the synderesis rule)

- Preservation of life

- Ordering of society

- Worship of God

- Education of children

- Reproduction

And from these primary precepts, we can also derive secondary precepts, which are more specific rules for behaviour. For example:

- It follows from the primary precept of preservation of life that you shouldn’t kill someone if you find them irritating (a secondary precept).

- The Catholic prohibition of contraception (a secondary precept) is derived from the primary precept of reproduction.

Double effect

Aquinas also talks about double effect , where a single action causes multiple effects. In such cases, what matters is that the intended effect is in line with the precepts.

Example: Killing in self-defence. Killing someone obviously violates the primary precept of preservation of life. But if a person kills someone in self-defence of their own life, there are two effects: 1. Killing the would-be murder, and 2. Saving your own life. As long as the person’s intention is 2 – to save their own life – then killing in self-defence is morally acceptable.

Situation ethics (Fletcher)

Joseph Fletcher’s approach to ethics argues that what is morally good is to act in the most loving way. The religious basis for this is the constant theme of agape/love in Jesus’ teachings in the New Testament. Orthodox religious ethics often emphasises universal moral laws (e.g. the 10 commandments), but Fletcher’s situation ethics argues that what is most loving (and therefore what is good) differs depending on different situations.

The Greek word agape translates to (unconditional) love . This is the word Jesus uses in the context of the ‘greatest’ commandments, one of which is:

“Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. There is none other commandment greater than these.” – Mark, chapter 12 verse 31 (KJV)

For Fletcher, this verse captures the essence of ethics. Specific rules, such as “Thou shalt not kill” (Exodus 20:13), are secondary to this general principle of agape/love. You shouldn’t kill people because , in general , it is not a loving thing to do. However, in the rare situation where killing is the loving thing to do, then that is what is ethically right. For example, Fletcher describes a situation where a group of Irish immigrants to America were hiding from natives who wanted to kill them. A baby was about to start crying, which would reveal the immigrants’ location and result in them all being killed. In this situation, Fletcher argues, killing the baby was the most loving thing to do as doing so would save the others and the baby would die anyway if the natives found them.

Fletcher argues that situation ethics allows for a middle way between two extremes in ethical thinking: Legalism and antinomianism .

The 4 working principles

Fletcher identifies 4 working principles – i.e. 4 general principles he assumes that underpin his situation ethics:

- Pragmatism: Moral truth should not be understood in a theoretical and abstract way but instead moral truth should be grounded in what works in reality .

- Relativism: Fletcher avoids absolute rules, such as ‘ never steal’. The only thing that is absolute is love, and so what is morally right is relative to love and depends on the details of the situation.

- Positivism: The ultimate foundation for moral judgements is faith . We do not use reason or observation to deduce what is morally right, we instead choose to have faith in love and then work out what is morally right from there.

- Personalism: It is people who can love and be loved, and so moral value comes from people rather than rules.

The 6 propositions

Fletcher further identifies 6 propositions – i.e. 6 statements – that follow from agape and the 4 working principles above and summarise his situation ethics:

- In other words, love is the only thing that is good in itself . Work, for example, is extrinsically good to make money , and money is extrinsically good to buy things , but love is intrinsically good – it’s good in itself and not for some other reason.

- This is the idea described above and illustrated with the baby example that specific rules are secondary to the general principle of love/agape. In the Old Testament, there are lots of specific laws, but Fletcher says these are less important than the general principle of love. There is some scriptural support for this in the New Testament, such as “For all the law is fulfilled in one word, even in this; Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” (Galatians 5:14).

- We might think that justice and love can conflict. For example, if someone steals something, justice says to punish the thief whereas love says to forgive them. However, Fletcher says it is not possible for justice and love to actually conflict because justice reduces to love – they are ultimately the same thing.

- Agape is not like the feeling of love we have for our family and friends. It is a decision to act for the good of others regardless of how we might personally feel about them. This attitude extends to all, even our enemies: “But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you;” (Matthew 6:44)

- This is illustrated by the example above : Even killing a baby (the means ) can be justified if it ultimately achieves a loving outcome (i.e. the end ).

- As described above , what’s morally right is not determined by rigidly following rules. Instead, we must instead decide our actions based on love according to the circumstances of the situation.

Conscience as a verb

The word conscience is typically used as a noun – it’s a thing that people have or don’t. It might be thought of as a part of the mind or soul that understands what is morally right and wrong. This is how Freud analyses conscience , for example – as a part of our mind.

However, Fletcher says we should understand conscience as a verb – it is a process of deciding what is right or wrong. Understood this way, it makes more sense to talk about conscienc ing rather than talking about conscience as a thing that constantly exists whether we’re using it or not (this is also more in line with how Aquinas analyses conscience ).

Normative ethical theories

Whereas religious approaches to ethics say what’s right and wrong is grounded in God, normative ethical theories appeal to general (secular) principles:

- Kant takes a deontological approach and argues we can derive universal moral rules about what is right and wrong using reason .

- Utilitarianism takes a teleological approach and argues that what is right or wrong depends on the consequences .

Deontological ethics (Kant)

For a more in-depth explanation, see the Kant’s deontological ethics notes for AQA philosophy.

Immanuel Kant’s approach to ethics is deontological: It says there are universal rules/laws about which actions are morally right or wrong, such as “never steal”. And these rules should be followed in all circumstances, regardless of the consequences. Kant says we can work out what these moral rules/laws are by using reason .

Duty and good will

Kant says we have a duty to follow the moral law – i.e. to do what is right.

And good will , according to Kant, means to choose our actions for the sake of duty . This means to choose our actions because they are right thing to do and not for any other reason.

We might have a duty to help an old lady across the road, say. And so someone who helps the old lady across the road does the right thing. But if they only do the right thing because they want others to think that they’re a good person , or because they think the old lady will give them a reward , they only act in accordance with duty and not out of duty. The person who acts with good will helps the lady across the road acts out of duty: They do the right thing because it is morally right.

The categorical imperative

For Kant, moral laws are categorical – they apply to everyone regardless of circumstances.

A hypothetical imperative is one that only applies to certain people in circumstances. For example, “you should leave now if you want to catch the 3pm train” only applies to people who want to catch the 3pm train. But the moral law, says Kant, is categorical – it applies to everyone at all times regardless of circumstances.

When we act, says Kant, we act according to a maxim (i.e. a rule for behaviour). Kant describes various tests to see whether our maxim passes the categorical imperative and thus whether our maxim is morally acceptable:

- Universal law formulation

- Don’t treat people as means formulation

- Kingdom of ends formulation

Test 1: The universal law formulation

“Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law without contradiction.” – Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals

If an act can’t be made into a universal law without resulting in a logical contradiction , Kant says that action is morally wrong.

Example: Stealing. If everybody followed the rule ‘to steal other people’s property’, then nobody would have any property to steal in the first place! And so, in a world where stealing is made into a universal law, it is not even possible to steal. Thus, stealing is always morally wrong – no exceptions.

Test 2: Don’t treat people as a means (humanity formula)

“Act in such a way that you always treat humanity […] never simply as a means , but always at the same time as an end .” – Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals

If an action means using another human being solely as a means to achieve your own goals, Kant says that action is morally wrong.

Example: Marrying someone for their money. If you pretend to love someone in order to marry them and get half their money, you are using that person solely as a means to make money for yourself. That person might have their own goals/ends (such as marrying a partner who genuinely loves them) but you are ignoring their goals/ends as a means to selfishly achieve your own goals/ends.

Another example: If you buy an apple from a shopkeeper, you are not using the shopkeeper solely as a means to get an apple because the shopkeeper is freely pursuing their own ends (e.g. to make money). There’s some sense in which both sides use each other as a means , but this is OK because both sides acknowledge the other’s ends (and so don’t use each other solely as a means).

Test 3: The kingdom of ends formulation

“Act in accordance with the maxims of a member giving universal laws for a merely possible kingdom of ends. ” – Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals

Finally, Kant asks us to imagine a ‘ Kingdom of Ends ‘ where everyone acts according to the two tests above. In this ideal world, everybody only acts according to rules that can be applied universally and nobody treats another human being as a means but always as an end. We must imagine ourselves as a lawmaker in this ideal world – not our actual world – and consider whether our action could work as a law in the Kingdom of Ends. If such a law wouldn’t work in the Kingdom of Ends, then we shouldn’t do that action.

The 3 postulates

Kant also talks about the summum bonum , or highest good . This is a world of perfect justice where people behave with perfect virtue and are rewarded for doing so with perfect happiness. Kant says we have a duty to strive towards the summum bonum .

However, a duty to strive towards the summum bonum only makes sense if such a state of affairs is actually possible in practice. And so, Kant identifies 3 postulates we must assume that make the summum bonum possible:

- Free will: If we do not freely choose our actions, then we are not responsible for them, and ethics would be pointless. So, for Kant, ethics requires free will.

- Immortality: People who do good things are not always rewarded for them. For example, a person who lives a moral life may die young from cancer whereas a lifelong thief may live a long and happy life. This is unfair and unjust. For Kant, the summum bonum requires that good deeds are rewarded proportionally with happiness and this can only be achieved if people are immortal.

- God: God must exist in order to enforce this justice and achieve the summum bonum.

Utilitarianism

For a more in-depth explanation, see the utilitarianism notes for AQA philosophy.

Utilitarian approaches to ethics are consequentialist: They say it is the consequences of an action that make it morally good or bad. So, whereas Kant’s deontological ethics says stealing is wrong in itself , act utilitarianism would say stealing is morally acceptable in situations where doing so would increase pleasure or reduce pain.

“The greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals.” – Jeremy Bentham

Utilitarianism is described on the syllabus as a teleological theory of ethics because it defines morality in terms of the end goal/purpose of happiness.

Utility and the hedonic calculus

Jeremy Bentham , the father of utilitarianism, understood utility (i.e. usefulness) as that which maximises happiness/pleasure and minimises unhappiness/pain.

He created the hedonic calculus (also called the felicific or utility calculus) as a way to calculate and quantify the utility of an action and thus to calculate and quantify how morally good or bad an action is. The hedonic calculus has 7 variables:

- Intensity: how strong the pleasure is

- Duration: how long the pleasure lasts

- Certainty: how likely the pleasure is to occur

- Propinquity: how soon the pleasure will occur

- Fecundity: how likely the pleasure will lead to more pleasure

- Purity: how likely the pleasure will lead to pain

- Extent: the number of people affected

So, let’s say we have two courses of action, A and B:

- A results in a 7/10 intensity pleasure that has a duration of 20 minutes.

- B results in a 6/10 intensity pleasure that has a duration of an hour.

The hedonic calculus would say the much longer duration of B – despite the slightly lower intensity – results in more utility and so is the morally superior course of action.

It gets complicated, though, when you have to predict and calculate all the other variables and compare them against each other ( see below for more on this ).

Act and rule utilitarianism

Act utilitarianism and rule utilitarianism calculate utility at different levels:

- Act utilitarianism calculates utility at the level of specific actions . For example, whether an act of stealing is right or wrong depends on whether, in that particular case , stealing increases or decreases utility/pleasure.

- In contrast, rule utilitarianism calculates utility at the level of general rules . For example, we may calculate that as a general rule stealing results in a reduction of utility/pleasure. And so, even though there may be specific cases where an act of stealing increases utility/pleasure, it is still wrong to steal in those instances because it violates a general rule that increases utility.

Ethical issues

The syllabus looks at 3 different ethical issues and applies the ethical theories above to them:

Business ethics

Sexual ethics.

Euthanasia means deliberately ending a person’s life to reduce their suffering. This may be achieved by active means (e.g. administering a lethal drug) or passive means (e.g. by withdrawing treatment or food) and may be a voluntary or non-voluntary decision . Such distinctions often determine whether someone considers an act of euthanasia morally acceptable or morally wrong (and also in many countries whether it is legal or illegal).

Of the ethical theories above, the syllabus specifically mentions how natural law and situation ethics may be applied to the issue of euthanasia .

Sanctity of life and quality of life

The principles of sanctity of life and quality of life may come into conflict on the issue of euthanasia.

Sanctity of life is the moral principle that all human lives are inherently valuable regardless of quality. This approach is generally associated with religious approaches to ethics for reasons such as:

- Murder is wrong: For example, Exodus 20:13 says “Thou shalt not kill”.

- Humans are made in God’s image: In the Bible, Genesis 1:27 says “So God created man in his own image”. This means all human lives possess some God-like divine component that is morally wrong to destroy.

- Humans do not have a right to decide: Job 1:21 says “the LORD gave, and the LORD hath taken away; blessed be the name of the LORD.” As it is God who gives life, God is the only one who has the right to take life.

Quality of life is the moral principle that there are degrees to which human lives are valuable based on certain conditions. As such, whether a life is valuable depends on factors such as pleasure, pain, or autonomy . The quality of life principle is generally associated with secular approaches to ethics for reasons such as:

- Utilitarianism: Utilitarian principles imply that some lives are more valuable than others because of different values of pleasure and pain. For example, if a person is experiencing constant and incurable pain with little or no joy or pleasure, the hedonic calculus may suggest that it is morally acceptable to end that person’s life so as to reduce the amount of pain in the world.

Voluntary and non-voluntary euthanasia

Autonomy is another factor to consider in the ethics of euthanasia.

Voluntary euthanasia is when a person acts with full autonomy and free will to consent to someone ending their life. John Stuart Mill’s harm principle says “over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign” and can be used to defend voluntary euthanasia as this principle says that humans have a right to do whatever they want with their own body and mind (as long as it does not cause harm to another person), which includes destroying it.

Non-voluntary euthanasia is when a person cannot act with autonomy to consent to someone ending their life. For example, if a person is in a coma or persistent vegetative state, they are unable to express their desire to continue living or end their life. In such situations, it often falls to another person (e.g. a family member or doctor) to represent their interests and provide consent.

(although not specifically mentioned on the syllabus, there’s also involuntary euthanasia , which is when a person can give consent, does not give consent, but someone decides to end their life anyway. This is probably the least morally ambiguous category, given that it’s basically just murder)

Ethical theories applied to euthanasia

Natural law applied to euthanasia.

In general, natural law (and the Catholic Church) would argue against euthanasia:

- 4 tiers of law: The natural law is below divine law in this hierarchy. And, given the Bible says things such as “Thou shalt not kill” (Exodus 20:13), natural law would likely argue that euthanasia (at least active euthanasia) is wrong.

- The precepts: One of the five primary precepts is preservation of life . Euthanasia is the opposite of preserving life – it’s deliberately shortening a life – and so this is another reason why natural law could argue euthanasia is wrong.

However, there are some exceptions/unusual cases where euthanasia may be morally acceptable:

- Active euthanasia and double effect: If a doctor administers a high dose of painkiller to alleviate pain (effect 1) which accidentally causes the death of the patient (effect 2), then this is morally acceptable because the intended effect was not in violation of natural law.

- Passive euthanasia and ordinary vs. extraordinary means: The Catholic Church says life should be preserved by ordinary means. For example, it is not acceptable to withdraw food or water for someone who is ill and wants to die. However, if preserving life requires extraordinary means – e.g. a risky or burdensome surgery – then it is morally acceptable to withhold such treatments even if doing so results in death of the patient.

Situation ethics applied to euthanasia

In general, situation ethics would permit euthanasia if the facts of the situation are appropriate:

- Rejection of legalism : The guiding principle of situation ethics is agape /love for one’s neighbour and this takes precedence over legalistic adherence to rules . As such, there is no absolute rule that applies in all situations, such as “Thou shalt not kill”.

- Relativism and personalism: A related consideration is Fletcher’s working principle of relativism; the rejection of absolute rules such as “Thou shalt not kill”. Instead, Fletcher works from the principle of personalism; that moral value comes from people rather than rules .

- Proposition 5: According to Fletcher, agape/love is the end goal of ethics and this can be achieved by any means, which would include euthanasia. In other words, if the situation is one where euthanasia is the most loving thing to do, then euthanasia is morally acceptable.

Business ethics is about moral issues for corporations, their customers, and the wider society. The ethical issues for businesses mentioned on the syllabus are corporate social responsibility , whistleblowing , and globalisation .

Of the ethical theories above, the syllabus specifically mentions how deontological ethics and utilitarianism may be applied to business ethics.

Corporate social responsibility

Businesses primarily exist to make money for shareholders. But corporate social responsibility (CSR) is the idea that businesses have ethical responsibilities to stakeholders in the wider community . For example:

- A responsibility to protect the environment

- A responsibility to protect their customers

- A responsibility to ensure the health and safety of employees

ESG (environmental, social, and governance) ratings are a way to quantify a company’s CSR efforts. For example, a company that uses sweatshops in poor countries would receive a lower ESG rating than a company that pays employees a living wage (all else being equal). Investors can invest in companies with good ESG ratings through indexes such as the FTSE4Good index, which is an index of UK (FTSE) companies that have high ESG scores.

Good ethics is good business

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest .” – Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations

Adam Smith provides a pragmatic case for CSR, arguing that good ethics is good business . The good ethics is good business position is that, in the long term , acting in accordance with CSR is the most effective way to make money and thus that good business decisions are good ethical decisions. For example:

- Customers: It may benefit a company in the short term to overcharge customers or cut corners to make a cheap product, but in the long term it will destroy the company’s reputation and customers will buy from a competitor instead.

- Employees: It may benefit a company to overwork employees and pay them low wages in the short term , but eventually the employees will take their skills and go work for a competitor that pays them more and provides better working conditions.

- Environment: It may be cheaper in the short term for a company to dump toxic waste into the local river, but eventually people will find out and the company’s reputation will be destroyed and no one will buy from them.

Ethical theories applied to CSR

Deontological ethics applied to csr.

In general, the categorical imperative implies businesses (through the people running them) have several ethical responsibilities over and above profit, such as:

- To employees: Companies cannot treat employees solely as a means to make money as this would violate the second formulation . Instead, companies should treat employees as ends in themselves, which would mean paying them a fair wage and providing safe and humane working conditions.

- To customers: Kant gives an example of how shopkeepers have a duty to charge a fair price to customers. But Kant uses this example to make a point about good will : A shopkeeper who charges a fair price because it is good for his reputation and thus his business is not morally praiseworthy because he only acts in accordance with duty and not because of duty. Kant says we should always choose our actions – whether in business or life in general – because they are morally right and not for some other reason. This is in contrast to Smith’s point above that we should behave ethically because it is good business – Kant says we should behave ethically because of duty , regardless of whether it is good or bad for business.

Utilitarianism applied to CSR

The hedonic calculus says we should maximise pleasure and minimise pain. And, in most cases, it’s unlikely that a business maximising its profit without regard for CSR would also happen be the most efficient way to maximise pleasure:

- Rule utilitarian response: However, capitalists argue that businesses pursuing profit has resulted in economic growth that has benefited society more in the long run. For example, competition to produce food more efficiently and increase profits has led to technological innovations that have reduced global hunger. If food companies had been forced to distribute their profits to hungry people rather than re-investing in their own businesses, it’s possible these technological innovations wouldn’t have happened and overall hunger would be greater today. It’s a bit long-winded, but you could make a rule utilitarian argument along these lines that allowing businesses freedom to pursue profits without CSR results in greater happiness overall than not having this rule.

Whistleblowing

Whistleblowing is when an employee discloses information about serious ethical wrongdoing at their company. This may be done privately or publicly:

- Private: The employee reports wrongdoing to someone within the company (e.g. raising the issue with senior management).

- Public: The employee reports wrongdoing to someone outside of the company (e.g. going to the news/media).

The ethics of whistleblowing involves balancing loyalty to the company with concern for the wider public good.

Ethical theories applied to whistleblowing

Deontological ethics applied to whistleblowing.

- Duty: Kant would say employees have certain duties to towards their employer, such as to carry out orders.

- Categorical imperative : However, our duties as an employee cannot override our wider moral duties. For example, the first formulation implies that we must never lie because if telling lies was made a universal law then nobody would believe anyone. And so, if an employer orders an employee to lie to protect the company, Kant would say our duty to tell the truth takes priority.

Utilitarianism applied to whistleblowing

- Hedonic calculus : Whether an act of whistleblowing is right or wrong must be calculated according to the specific circumstances. If the pleasure that results from an act of whistleblowing (e.g. legal intervention results in improvements in employee working conditions) outweighs the pains (e.g. job losses and fines for the company), then whistleblowing is morally acceptable. If whistleblowing results in a lot of pain and unhappiness without much pleasure in return, then whistleblowing is morally wrong.

Globalisation

Globalisation can have both positive and negative effects:

Ethical theories applied to globalisation

Deontological ethics applied to globalisation.

- Categorical imperative : In principle, globalisation doesn’t seem to violate any of the tests of the categorical imperative. There’s no contradiction that results from manufacturing goods in another country, for example. However, in practice, the reality of globalisation is often at odds with deontological ethics. For example, companies outsource manufacturing to sweatshops and countries with weak labour laws. Such business practices could be accused of using employees solely as a means to increase profit, which violates the second formulation .

Utilitarianism applied to globalisation

- Hedonic calculus: The positive and negative effects of globalisation described above must be weighed against each other according to the hedonic calculus. For example, globalisation has lifted millions of people out of poverty (e.g. in China since 1970), but also concentrated wealth among a small group of companies and people leading to increased inequality. If the pleasures outweigh the pains, then utilitarianism would say globalisation is morally good.

Sexual ethics looks at ethical issues in sexual and romantic relationships. The particular issues mentioned on the syllabus are premarital sex, extramarital sex , and homosexuality .

The syllabus also mentions how all the ethical theories above may be applied to sexual ethics. As some of these ethical theories are religious in nature (i.e. natural law and situation ethics), a related issue to the extent to which religious ideas about ethics should inform laws and attitudes towards sex in an increasingly secular society. Another issue mentioned on the syllabus is whether sexual behaviours should be treated as entirely private or whether they should be subject to social norms and legislation.

Premarital and extramarital sex

Premarital sex

Premarital sex is when you have sex with someone before you are married to them.

Attitudes to premarital sex have changed over time. Religious teachings generally forbid premarital sex and these teachings influenced historical social attitudes. For example, a few decades ago, it was common to describe cohabiting couples who weren’t married as ‘living in sin’. But nowadays, religious attitudes are less influential and it’s more common than not for couples to move in together before getting married.

Ethical issues surrounding premarital sex:

- Differences in degree: ‘Premarital sex’ covers everything from one night stands with random people right up to sex between a committed couple who’ve been together for years but just aren’t married. Are all instances of premarital sex the same, ethically?

- Pregnancy: Before the pill, sexual encounters carried a higher risk of pregnancy so women may have been more likely to demand the commitment of marriage before sex so as not to be left to raise the child alone.

- Sexually transmitted diseases: Having sex with a single partner reduces the risk of sexually transmitted infections. However, condoms have reduced this risk of premarital sex to some degree.

Extramarital sex

Extramarital sex is when you have sex with someone who isn’t your husband/wife when you are already married.

Although some religious cultures permit men to have multiple wives (e.g. David and Solomon had multiple wives in the Old Testament), religious teachings generally forbid extramarital sex. For example, one of the 10 commandments is “Thou shalt not commit adultery” (Exodus 20:14). Despite a general decline in religious belief, societal attitudes towards extramarital sex have remained generally negative. This consistent attitude may have a biological basis related to paternity and raising children.

Ethical issues surrounding extramarital sex:

- Cheating: Is extramarital sex ethically worse than cheating on a long-term partner who you are not married to?

- Open marriages: Is extramarital sex ethically permissible if both partners agree to an open marriage?

Ethical theories applied to premarital and extramarital sex

Natural law applied to premarital and extramarital sex.

In general, natural law argues against premarital and extramarital sex:

- 4 tiers of law: The natural law is below divine law in this hierarchy. On the issue of extramarital sex, one of the 10 commandments in the Bible is “Thou shalt not commit adultery.” (Exodus 20:14), which suggests extramarital sex is wrong according to natural law. On the issue of premarital sex, although there are no Bible verses that condemn it specifically , there are many verses arguing against ‘sexual immorality’ and ‘fornication’ (e.g. Galatians 5:19) and so premarital sex is also wrong according to natural law.

- The precepts: One of the five primary precepts is reproduction . A lot of natural law (and Catholic) thinking on sexual ethics is based on this – that sex should only be between a married couple and, as Pope Paul VI says, “retain its intrinsic relationship to the procreation of human life” . The precepts of ordering of society and education of children may also inform sexual ethics regarding extramarital and premarital sex, as marriage provides stability and structure for children.

Situation ethics applied to premarital and extramarital sex

As always, what Fletcher’s situation ethics says depends on the situation . Fletcher rejects legalism and as such there are no absolute rules regarding premarital or extramarital sex:

- Agape applied to premarital sex : Situation ethics demands we do the most loving thing, which is not necessarily the same thing as the most pleasurable thing (i.e. utilitarianism). As such, Fletcher may draw a distinction between premarital sex between a committed couple who are in love and casual sex between two people who are just having sex for pleasure .

- Agape applied to extramarital sex : In general, extramarital sex would not be the most loving thing to do. However, Fletcher acknowledges various situations where it would be morally acceptable. For example, he describes the situation of a married woman in a prison camp during a war who deliberately gets pregnant by one of the guards in order to be released from the prison camp and return to her family.

Deontological ethics applied to premarital and extramarital sex

Kant would argue against extramarital sex:

- Second formulation of the categorical imperative : A marriage is a promise to remain faithful to your partner (among other things). Kant argues that to break a promise is to treat the person we made the promise to as a means rather than an end and as such violates the humanity formula of the categorical imperative. As such, extramarital sex is morally wrong according to Kant.

- First formulation of the categorical imperative : Further, Kant may argue that if extramarital sex were made a universal law, then the very concept of marriage (as an exclusive agreement between two people) would become meaningless. As such, extramarital sex violates the universal law formulation too.

Kant also argues against premarital sex too, on the grounds that it means using another person (and yourself) solely for their body and objectifies them, which ‘degrades humanity’. His reasoning for this is a bit convoluted:

- Kant’s response: Because in marriage the partners give each other their entire “person, body and soul” and not just the sexual aspect. This leads to “a union of human beings” that does not degrade their humanity and objectify them.

Utilitarianism applied to premarital and extramarital sex

In general, utilitarianism permits both premarital and extramarital sex:

- Hedonic calculus applied to premarital sex : Sex is pleasurable, and so utilitarianism would generally have no issue with premarital sex. There are obvious exceptions to this, however, such as rape, as well as consideration of longer-term consequences, such as the pleasures and pains of any offspring that results from sex.

- Hedonic calculus applied to extramarital sex : With utilitarianism, there are no rules or principles over and above pleasure, and so no rules against extramarital sex. In calculating whether an act of extramarital sex is right or wrong, a person must weigh their pleasure from extramarital sex against their spouse’s pain at being cheated on. An obvious way to reduce this pain is to lie to your partner and say you didn’t cheat on them.

Homosexuality

Both attitudes and the law with regards to homosexuality have changed over time. In the UK, homosexual sex was a criminal offence until 1967. In 2005, the law was changed to allow civil partnerships between same-sex couples and in 2014 this was extended to full marriage rights.

Religious teachings generally forbid homosexuality. For example, Leviticus 18:22 says: “Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination.” Historically, social attitudes towards homosexuality have been similarly negative. However, modern secular culture generally makes no distinction between the ethics of heterosexual and homosexual sex. These changing social attitudes may have influenced religious attitudes, with modern religious teachings being generally more tolerant of homosexuality than in the past.

Ethical issues surrounding homosexuality:

- Tolerance of homophobia: To what extent should secular cultures tolerate religious views that say homosexuality is wrong?

- Marriage: If marriage is a religious institution, is it ethical (or even possible) for homosexual couples to marry?

- Children: Although homosexual couples can’t (naturally) produce children, is it ethical for them to adopt children?

Ethical theories applied to homosexuality

Natural law applied to homosexuality.

In general, natural law would argue against homosexuality:

- 4 tiers of law: The natural law is below divine law in this hierarchy. And, given the Bible says things such as “Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination.” (Leviticus 18:22), this suggests homosexuality is wrong according to natural law.

- The precepts: One of the five primary precepts is reproduction . The fact that homosexual couples cannot (naturally) produce children is another reason why homosexual sex might be considered wrong according to natural law.

Situation ethics applied to homosexuality

In general, Fletcher’s situation ethics says homosexuality is morally acceptable:

- Agape : The guiding principle of situation ethics is agape/love for one’s neighbour and this takes precedence over legalistic adherence to rules (such as Leviticus 18:22). It is hard to envisage many situations where rejecting homosexuality is the most loving thing to do.

- Relativism and personalism : A related notion is Fletcher’s principle of relativism; the rejection of absolute rules such as “homosexuality is wrong”. Instead, Fletcher argues for personalism; the idea that moral value comes from people , rather than rules .

- Propositions 2 and 6 : Similarly, propositions 2 and 6 reject laws (e.g. “homosexuality is wrong”) in favour of the general principle of love applied to the specific details of the situation.

Deontological ethics applied to homosexuality

In general, Kant and deontological ethics are against homosexuality:

- Categorical imperative : We cannot will that everybody be homosexual as a universal law because then the human race would die out. A such, homosexuality fails the first formulation and is morally wrong.

Utilitarianism applied to homosexuality

In general, utilitarianism supports homosexuality:

- Hedonic calculus : With utilitarianism, there are no rules or principles over and above pleasure and so if someone is attracted to the same sex, and find having sex with them pleasurable, then there is no reason why homosexuality would be morally different to heterosexuality.

The ethical theories above – natural law , situation ethics , deontological ethics , and utilitarianism – all take it for granted that moral properties – i.e. ‘good’ and ‘bad’ – are things that exist. They take these moral properties to give rise to moral facts , such as “stealing is wrong”. However, metaethics drills down into what moral properties actually are and whether they even exist.

Moral realist theories say mind-independent moral properties and facts do exist:

- Naturalism says mind-independent moral properties are natural properties that can be known a posteriori using observation.

- Intuitionism also says mind-independent moral properties exist, but says they are non-natural properties that can only be known using a priori intuition.

In contrast, moral anti-realist theories say mind-independent moral properties and facts do not exist:

- Emotivism says there are no such things as mind-independent moral properties, and so no moral facts either. Instead, moral statements are non-cognitive expressions of emotion.

For a more in-depth explanation, see the ethical naturalism notes for AQA philosophy.

Moral naturalism is a realist theory; it says that mind-independent moral properties (such as ‘good’ and ‘bad’) do exist. More specifically, naturalism says these moral properties are natural properties and so moral facts (such as “stealing is wrong”) can be known by making a posteriori observations of the world.

Examples of naturalist ethical theories we’ve looked at above are:

- Utilitarianism: Utilitarianism is meta-ethically naturalist because it says good = pleasure and bad = pain. Pleasure and pain are natural and observable properties and so good and bad are also natural and observable properties.

- Natural law: Aquinas’ theory of natural law is meta-ethically naturalist because it says there are natural (God-given) facts about a thing’s purpose/telos and that what is good is for a thing to achieve this purpose/telos. By observing the world, we can understand our telos and thus what is good and bad.

All forms of moral naturalism are cognitivist ; they say there are true moral statements, such as “stealing is wrong”. What makes this moral statement true or false depends on whether the act of stealing has the natural property of wrongness.

Intuitionism

For a more in-depth explanation, see the ethical non-naturalism notes for AQA philosophy. Like naturalism above, intuitionism is also a realist theory; it agrees that mind-independent moral properties (such as ‘good’ and ‘bad’) do exist. However, where naturalism says these properties are natural properties that can be known through a posteriori observation, intuitionism says moral properties are not part of the natural/physical world and can only be known using a priori intuition.

G.E. Moore argues for intuitionism. He argues that ethical naturalism commits the naturalistic fallacy (see AQA notes here for more detail) of reducing moral properties (e.g. good) to natural properties (e.g. pleasure) when, in reality, moral properties are basic and cannot be reduced to anything simpler. Moore draws an analogy between moral properties and the colour yellow: You can’t explain what yellow is by breaking it down into something simpler – you just have to show someone something yellow. Likewise, you can’t explain what ‘wrongness’ is by breaking it down into simpler, natural, properties – you have to give an example (e.g. torturing an innocent person).

However, if moral properties are not part of the natural world, this raises the question of how we know about them since it’s not like we can observe them like we can ordinary natural properties. Moore’s answer is a priori intuition : The fact that “torturing innocent people is wrong” is just self-evidently true when we reflect and think about it.

Note that intuitionism is also cognitivist ; it says that moral statements are capable of being true (or false). The reason why the statement “torturing innocent people is wrong” is true is because the act of torturing innocent people has the non-natural property of ‘wrongness’.

For a more in-depth explanation, see the emotivism notes for AQA philosophy.

Whereas naturalism and intuitionism are moral realist theories, emotivism is anti-realist . This means emotivists believe that mind-independent moral properties (e.g. ‘good’, ‘wrong’) don’t actually exist.

Instead, according to emotivism, moral statements (e.g. “murder is wrong”), are not descriptions of properties of the world but are actually non-cognitive expressions of emotion . This means moral statements are neither true or false.

Emotivism is sometimes referred to as boo-hooray theory . When football fans cheer when their team scores, for example, it’s not like they are describing the world in a way that is true or false. Instead, they’re just expressing their happiness that their team scored. Similarly, for emotivists, saying “giving money to charity is good” is like cheering for giving money to charity. Saying “Stealing is wrong” is like saying “ Boooo! Stealing!” and expressing your disapproval.

Our conscience is the inner voice that tells us something is morally right or wrong. It makes us feel guilty when we do something bad and feel happy when we do something good. The syllabus looks at 2 different explanations of conscience:

- Aquinas says our conscience is because we are made in God’s image with the ability to use reason to work out what’s right and wrong.

- Freud says our conscience has a purely psychological explanation that can be explained without God.

Aquinas’ theological approach

As described above , right and wrong are a matter of natural law for Aquinas. And Aquinas explains our conscience as the result of ratio: Our ability to use reason to work out what this natural law is. He breaks conscience down into 2 components: Synderesis and conscientia .

According to Aquinas, we have this capacity to reason (i.e. ratio) about right and wrong because we are made in God’s image. So, this is a theological explanation of conscience.

Synderesis is our natural habit or capacity towards what is morally good. If you remember the main precept above – to do good and avoid evil – this in some sense built in to our nature, says Aquinas. Just as plants have a natural inclination to grow towards the sun in accordance with their telos , so too do human beings have a natural inclination to behave morally and act in accordance with natural law. Aquinas describes synderesis as “the law of our mind”.

Conscientia

But synderesis doesn’t mean we automatically have perfect knowledge of right and wrong. Synderesis means we generally tend towards good, but we may be conflicted or confused as to how this actually translates to practical situations like euthanasia or extramarital sex . This is where conscientia is needed.

Conscientia is the use of reason (ratio) to work out what is right and wrong in practical situations. In the case of euthanasia, we may use conscientia to reason that euthanasia violates the primary precept of preservation of life and is thus morally wrong. So, for Aquinas, conscience is a process of reasoning ( similar to how Fletcher describes conscience as a verb above ) rather than some inner voice that automatically tells us what’s right.

We may sometimes make mistakes in our moral reasoning/conscientia. However, Aquinas says we must always follow our conscience regardless. To act against your conscience – even if the end result turns out to be the right thing – is a sin because it is to choose an action you believe to be wrong.

Vincible and invincible ignorance

Aquinas distinguishes between two types of mistake that lead to immoral behaviour:

- For example, a man may reason that it is morally acceptable to cheat on his wife because he confuses the apparent good of his pleasure with the real good of his marriage. This is his fault because it is within his power to use conscientia to work out what the correct moral rule is but doesn’t.

- For example, a man cheats on his wife because she has an identical twin sister who tricks him into thinking she’s his wife. This is not his fault because he has reasoned correctly about the moral rules concerning adultery and has acted according to his conscience, but has made a mistake due to something outside his control.

Freud’s psychological approach

Whereas Aquinas sees our conscience as something grounded in God, Freud rejects the existence of God as a man-made idea. Instead, Freud explains our conscience in purely psychological terms.

Freud’s psychological theory emphasises the role of the unconscious mind . Different parts of the mind have different goals and desires. Our conscience is one part of our personality ( the superego ) that develops during the phallic psychosexual stage of development. However, the superego/conscience often comes into conflict with other parts of our personality.

Structure of personality: Id, Ego, and Superego

Freud saw personality as consisting of 3 parts: The id , the ego , and the superego . These 3 parts of personality have competing demands that often come into conflict with each other.

Our id is only concerned with pleasure and so wants to indiscriminately have sex with attractive people and kill annoying people, for example. But this obviously isn’t a suitable way to behave. As children, our parents and society tell us that such behaviours are morally wrong , which teaches us an ideal standard of behaviour that becomes our superego or conscience.

The ego is the part of the mind we are most consciously aware of. It sits between the id and the superego, balancing their competing demands. When we give in to our id and behave badly, the superego punishes the ego by creating feelings of guilt .

And so, according to Freud, our conscience/superego is just a product of our upbringing – parents, society, etc. – rather than a reflection of moral reality or God.

Psychosexual development

According to Freud, psychological development in childhood involves progressing through 5 psychosexual stages : 1. Oral, 2. Anal, 3. Phallic, 4. Latency, and 5. Genital. It is during the phallic stage (between 3-5 years of age) where the superego /conscience develops.

This is where the theory gets wild. The specifics differ between girls ( Electra Complex ) and boys ( Oedipus Complex ), but the general pattern during the phallic stage is:

- Boys develop sexual desire for their mothers

- Girls develop 1. A desire to have a penis (penis envy) and 2. A desire for their father (as he has what she wants – a penis)

- The boy wants to kill his father so he can have his mother for himself

- The girl 1. Thinks the reason she doesn’t have a penis is because her mother took it, and 2. Sees her mother as competition for her father’s love

- For boys this is because they fear their father will find out about their sexual desire for the mother and castrate them

- For girls this is because they also love their mothers and fear losing her love

- The child resolves these feelings of anxiety by identifying with their same-sex parent

- Identifying with the same-sex parent means accepting and internalising their moral values

- This forms the superego/conscience

<< Paper 1: Philosophy of Religion

Paper 3: developments in religious thought >>>.

rsrevision.com/ethical theory

- Theory in detail

- Applied ethics

Find out more

Test yourself.

- Games and Quizzes

Exam practice

- You may get asked to explain Kant's theory, or an aspect of it.

- You may be required to evaluate the theory or compare it to another theory.

- You may be asked to apply Kant's theory to one of the issues studied.

Have a look at 'Evaluating the Theories' and TICKETs (pdfs), as well as each of the ethical theories on War (AS) and the Environment (A2) .

- Explain the main aims of Kant's ethical theory. [25]

- 'Kant's idea of universalisation does not work in practice.' Discuss. [10]

- Explain how the various formulations of the Categorical Imperative might be applied to an ethical issue. [25]

- 'The Categorical Imperative has no serious weaknesses.' Discuss. [10]

- Explain, with examples, the importance Kant placed upon doing one’s duty. [25]

- To what extent is doing one’s duty the most important part of ethics? [10]

- Explain the differences between the Hypothetical and Categorical Imperatives. [25]

- How useful is Kant's theory when considering embryo research? [10]

- Explain Kant's argument for using the Categorical Imperative. [25]

- 'The universalisation of maxims by Kant cannot be defended.' Discuss. [10]

The following question was from June 2010 :

- Explain how a follower of Kantian ethics might approach issues surrounding the right to a child. [25]

- 'The right to a child is an absolute.' Discuss. [10]

This question was from June 2009 :

- Explain the strengths of Kant's theory of ethics. [25]

- 'Kant's theory of ethics is not a useful approach to abortion.' Discuss. [10]

This question was from the January 2009 AS Ethics paper :

Explain, with examples, Kant’s theory of the Categorical Imperative.

‘Kant’s theory has no serious weaknesses.’ Discuss.

This question was from the OCR Website :

Explain Kant’s theory of duty.

- To what extent is Kant’s ethical theory a good approach to human embryo research?

(a) Explain what Kant meant by ‘the Categorical Imperative’. [33] (b) Assess critically Kant’s claims about the Categorical Imperative. [17]

(taken from the OCR website )

(a) 'People should always do their duty.' Explain how Kant understood this concept. [33] (b) 'The use of the Categorical Imperative makes no room for compassionate treatment of women who want abortions.' Discuss. [17]

Evaluate the argument that Kant’s moral theory could not support the idea of voluntary euthanasia.

We now have an interactive diagram showing how to answer an ethics exam question, The 'structure' of the paragraph will be different for 'ethical theory' questions, but the basic principles are the same. Try filling it in yourself and print out the completed diagram.

lauren's A level religious studies revision

all of my A level revision for the religious studies 2016 OCR spec x

example essays master post

*long post alert*

hi! i finished this course over a year ago now but someone commented asking me to post some example essays, so i thought that might be helpful seeing as this blog seems to get only more busy!