An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A Literature Review: Website Design and User Engagement

Renee garett.

1 ElevateU, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Sean D. Young

2 University of California Institute for Prediction Technology, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

3 UCLA Center for Digital Behavior, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Proper design has become a critical element needed to engage website and mobile application users. However, little research has been conducted to define the specific elements used in effective website and mobile application design. We attempt to review and consolidate research on effective design and to define a short list of elements frequently used in research. The design elements mentioned most frequently in the reviewed literature were navigation, graphical representation, organization, content utility, purpose, simplicity, and readability. We discuss how previous studies define and evaluate these seven elements. This review and the resulting short list of design elements may be used to help designers and researchers to operationalize best practices for facilitating and predicting user engagement.

1. INTRODUCTION

Internet usage has increased tremendously and rapidly in the past decade ( “Internet Use Over Time,” 2014 ). Websites have become the most important public communication portal for most, if not all, businesses and organizations. As of 2014, 87% of American adults aged 18 or older are Internet users ( “Internet User Demographics,” 2013 ). Because business-to-consumer interactions mainly occur online, website design is critical in engaging users ( Flavián, Guinalíu, & Gurrea, 2006 ; Lee & Kozar, 2012 ; Petre, Minocha, & Roberts, 2006 ). Poorly designed websites may frustrate users and result in a high “bounce rate”, or people visiting the entrance page without exploring other pages within the site ( Google.com, 2015 ). On the other hand, a well-designed website with high usability has been found to positively influence visitor retention (revisit rates) and purchasing behavior ( Avouris, Tselios, Fidas, & Papachristos, 2003 ; Flavián et al., 2006 ; Lee & Kozar, 2012 ).

Little research, however, has been conducted to define the specific elements that constitute effective website design. One of the key design measures is usability ( International Standardization Organization, 1998 ). The International Standardized Organization (ISO) defines usability as the extent to which users can achieve desired tasks (e.g., access desired information or place a purchase) with effectiveness (completeness and accuracy of the task), efficiency (time spent on the task), and satisfaction (user experience) within a system. However, there is currently no consensus on how to properly operationalize and assess website usability ( Lee & Kozar, 2012 ). For example, Nielson associates usability with learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors, and satisfaction ( Nielsen, 2012 ). Yet, Palmer (2002) postulates that usability is determined by download time, navigation, content, interactivity, and responsiveness. Similar to usability, many other key design elements, such as scannability, readability, and visual aesthetics, have not yet been clearly defined ( Bevan, 1997 ; Brady & Phillips, 2003 ; Kim, Lee, Han, & Lee, 2002 ), and there are no clear guidelines that individuals can follow when designing websites to increase engagement.

This review sought to address that question by identifying and consolidating the key website design elements that influence user engagement according to prior research studies. This review aimed to determine the website design elements that are most commonly shown or suggested to increase user engagement. Based on these findings, we listed and defined a short list of website design elements that best facilitate and predict user engagement. The work is thus an exploratory research providing definitions for these elements of website design and a starting point for future research to reference.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. selection criteria and data extraction.

We searched for articles relating to website design on Google Scholar (scholar.google.com) because Google Scholar consolidates papers across research databases (e.g., Pubmed) and research on design is listed in multiple databases. We used the following combination of keywords: design, usability, and websites. Google Scholar yielded 115,000 total hits. However, due to the large list of studies generated, we decided to only review the top 100 listed research studies for this exploratory study. Our inclusion criteria for the studies was: (1) publication in a peer-reviewed academic journal, (2) publication in English, and (3) publication in or after 2000. Year of publication was chosen as a limiting factor so that we would have enough years of research to identify relevant studies but also have results that relate to similar styles of websites after the year 2000. We included studies that were experimental or theoretical (review papers and commentaries) in nature. Resulting studies represented a diverse range of disciplines, including human-computer interaction, marketing, e-commerce, interface design, cognitive science, and library science. Based on these selection criteria, thirty-five unique studies remained and were included in this review.

2.2. Final Search Term

(design) and (usability) and (websites).

The search terms were kept simple to capture the higher level design/usability papers and allow Google scholar’s ranking method to filter out the most popular studies. This method also allowed studies from a large range of fields to be searched.

2.3. Analysis

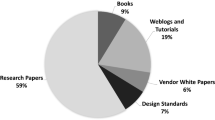

The literature review uncovered 20 distinct design elements commonly discussed in research that affect user engagement. They were (1) organization – is the website logically organized, (2) content utility – is the information provided useful or interesting, (3) navigation – is the website easy to navigate, (4) graphical representation – does the website utilize icons, contrasting colors, and multimedia content, (5) purpose – does the website clearly state its purpose (i.e. personal, commercial, or educational), (6) memorable elements – does the website facilitate returning users to navigate the site effectively (e.g., through layout or graphics), (7) valid links – does the website provide valid links, (8) simplicity – is the design of the website simple, (9) impartiality – is the information provided fair and objective, (10) credibility – is the information provided credible, (11) consistency/reliability – is the website consistently designed (i.e., no changes in page layout throughout the site), (12) accuracy – is the information accurate, (13) loading speed – does the website take a long time to load, (14) security/privacy – does the website securely transmit, store, and display personal information/data, (15) interactive – can the user interact with the website (e.g., post comments or receive recommendations for similar purchases), (16) strong user control capabilities– does the website allow individuals to customize their experiences (such as the order of information they access and speed at which they browse the website), (17) readability – is the website easy to read and understand (e.g., no grammatical/spelling errors), (18) efficiency – is the information presented in a way that users can find the information they need quickly, (19) scannability – can users pick out relevant information quickly, and (20) learnability – how steep is the learning curve for using the website. For each of the above, we calculated the proportion of studies mentioning the element. In this review, we provide a threshold value of 30%. We identified elements that were used in at least 30% of the studies and include these elements that are above the threshold on a short list of elements used in research on proper website design. The 30% value was an arbitrary threshold picked that would provide researchers and designers with a guideline list of elements described in research on effective web design. To provide further information on how to apply this list, we present specific details on how each of these elements was discussed in research so that it can be defined and operationalized.

3.1. Popular website design elements ( Table 1 )

Frequency of website design elements used in research (2000–2014)

Seven of the website design elements met our threshold requirement for review. Navigation was the most frequently discussed element, mentioned in 22 articles (62.86%). Twenty-one studies (60%) highlighted the importance of graphics. Fifteen studies (42.86%) emphasized good organization. Four other elements also exceeded the threshold level, and they were content utility (n=13, 37.14%), purpose (n=11, 31.43%), simplicity (n=11, 31.43%), and readability (n=11, 31.43%).

Elements below our minimum requirement for review include memorable features (n=5, 14.29%), links (n=10, 28.57%), impartiality (n=1, 2.86%), credibility (n=7, 20%), consistency/reliability (n=8. 22.86%), accuracy (n=5, 14.29%), loading speed (n=10, 28.57%), security/privacy (n=2, 5.71%), interactive features (n=9, 25.71%), strong user control capabilities (n=8, 22.86%), efficiency (n=6, 17.14%), scannability (n=1, 2.86%), and learnability (n=2, 5.71%).

3.2. Defining key design elements for user engagement ( Table 2 )

Definitions of Key Design Elements

In defining and operationalizing each of these elements, the research studies suggested that effective navigation is the presence of salient and consistent menu/navigation bars, aids for navigation (e.g., visible links), search features, and easy access to pages (multiple pathways and limited clicks/backtracking). Engaging graphical presentation entails 1) inclusion of images, 2) proper size and resolution of images, 3) multimedia content, 4) proper color, font, and size of text, 5) use of logos and icons, 6) attractive visual layout, 7) color schemes, and 8) effective use of white space. Optimal organization includes 1) cognitive architecture, 2) logical, understandable, and hierarchical structure, 3) information arrangement and categorization, 4) meaningful labels/headings/titles, and 5) use of keywords. Content utility is determined by 1) sufficient amount of information to attract repeat visitors, 2) arousal/motivation (keeps visitors interested and motivates users to continue exploring the site), 3) content quality, 4) information relevant to the purpose of the site, and 5) perceived utility based on user needs/requirements. The purpose of a website is clear when it 1) establishes a unique and visible brand/identity, 2) addresses visitors’ intended purpose and expectations for visiting the site, and 3) provides information about the organization and/or services. Simplicity is achieved by using 1) simple subject headings, 2) transparency of information (reduce search time), 3) website design optimized for computer screens, 4) uncluttered layout, 5) consistency in design throughout website, 6) ease of using (including first-time users), 7) minimize redundant features, and 8) easily understandable functions. Readability is optimized by content that is 1) easy to read, 2) well-written, 3) grammatically correct, 4) understandable, 5) presented in readable blocks, and 6) reading level appropriate.

4. DISCUSSION

The seven website design elements most often discussed in relation to user engagement in the reviewed studies were navigation (62.86%), graphical representation (60%), organization (42.86%), content utility (37.14%), purpose (31.43%), simplicity (31.43%), and readability (31.43%). These seven elements exceeded our threshold level of 30% representation in the literature and were included into a short list of website design elements to operationalize effective website design. For further analysis, we reviewed how studies defined and evaluated these seven elements. This may allow designers and researchers to determine and follow best practices for facilitating or predicting user engagement.

A remaining challenge is that the definitions of website design elements often overlap. For example, several studies evaluated organization by how well a website incorporates cognitive architecture, logical and hierarchical structure, systematic information arrangement and categorization, meaningful headings and labels, and keywords. However, these features are also crucial in navigation design. Also, the implications of using distinct logos and icons go beyond graphical representation. Logos and icons also establish unique brand/identity for the organization (purpose) and can serve as visual aids for navigation. Future studies are needed to develop distinct and objective measures to assess these elements and how they affect user engagement ( Lee & Kozar, 2012 ).

Given the rapid increase in both mobile technology and social media use, it is surprising that no studies mentioned cross-platform compatibility and social media integration. In 2013, 34% of cellphone owners primarily use their cellphones to access the Internet, and this number continues to grow ( “Mobile Technology Factsheet,” 2013 ). With the rise of different mobile devices, users are also diversifying their web browser use. Internet Explorer (IE) was once the leading web browser. However, in recent years, FireFox, Safari, and Chrome have gained significant traction ( W3schools.com, 2015 ). Website designers and researchers must be mindful of different platforms and browsers to minimize the risk of losing users due to compatibility issues. In addition, roughly 74% of American Internet users use some form of social media ( Duggan, Ellison, Lampe, Lenhart, & Smith, 2015 ), and social media has emerged as an effective platform for organizations to target and interact with users. Integrating social media into website design may increase user engagement by facilitating participation and interactivity.

There are several limitations to the current review. First, due to the large number of studies published in this area and due to this study being exploratory, we selected from the first 100 research publications on Google Scholar search results. Future studies may benefit from defining design to a specific topic, set of years, or other area to limit the number of search results. Second, we did not quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of these website design elements. Additional research can help to better quantify these elements.

It should also be noted that different disciplines and industries have different objectives in designing websites and should thus prioritize different website design elements. For example, online businesses and marketers seek to design websites that optimize brand loyalty, purchase, and profit ( Petre et al., 2006 ). Others, such as academic researchers or healthcare providers, are more likely to prioritize privacy/confidentiality, and content accuracy in building websites ( Horvath, Ecklund, Hunt, Nelson, & Toomey, 2015 ). Ultimately, we advise website designers and researchers to consider the design elements delineated in this review, along with their unique needs, when developing user engagement strategies.

- Arroyo Ernesto, Selker Ted, Wei Willy. Usability tool for analysis of web designs using mouse tracks. Paper presented at the CHI’06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems.2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Atterer Richard, Wnuk Monika, Schmidt Albrecht. Knowing the user’s every move: user activity tracking for website usability evaluation and implicit interaction. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 15th international conference on World Wide Web.2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Auger Pat. The impact of interactivity and design sophistication on the performance of commercial websites for small businesses. Journal of Small Business Management. 2005; 43 (2):119–137. [ Google Scholar ]

- Avouris Nikolaos, Tselios Nikolaos, Fidas Christos, Papachristos Eleftherios. Advances in Informatics. Springer; 2003. Website evaluation: A usability-based perspective; pp. 217–231. [ Google Scholar ]

- Banati Hema, Bedi Punam, Grover PS. Evaluating web usability from the user’s perspective. Journal of Computer Science. 2006; 2 (4):314. [ Google Scholar ]

- Belanche Daniel, Casaló Luis V, Guinalíu Miguel. Website usability, consumer satisfaction and the intention to use a website: The moderating effect of perceived risk. Journal of retailing and consumer services. 2012; 19 (1):124–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bevan Nigel. Usability issues in web site design. Paper presented at the HCI; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blackmon Marilyn Hughes, Kitajima Muneo, Polson Peter G. Repairing usability problems identified by the cognitive walkthrough for the web. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems.2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blackmon Marilyn Hughes, Polson Peter G, Kitajima Muneo, Lewis Clayton. Cognitive walkthrough for the web. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems.2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Braddy Phillip W, Meade Adam W, Kroustalis Christina M. Online recruiting: The effects of organizational familiarity, website usability, and website attractiveness on viewers’ impressions of organizations. Computers in Human Behavior. 2008; 24 (6):2992–3001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brady Laurie, Phillips Christine. Aesthetics and usability: A look at color and balance. Usability News. 2003; 5 (1) [ Google Scholar ]

- Cyr Dianne, Head Milena, Larios Hector. Colour appeal in website design within and across cultures: A multi-method evaluation. International journal of human-computer studies. 2010; 68 (1):1–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cyr Dianne, Ilsever Joe, Bonanni Carole, Bowes John. Website Design and Culture: An Empirical Investigation. Paper presented at the IWIPS.2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dastidar Surajit Ghosh. Impact of the factors influencing website usability on user satisfaction. 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Angeli Antonella, Sutcliffe Alistair, Hartmann Jan. Interaction, usability and aesthetics: what influences users’ preferences?. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 6th conference on Designing Interactive systems.2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Djamasbi Soussan, Siegel Marisa, Tullis Tom. Generation Y, web design, and eye tracking. International journal of human-computer studies. 2010; 68 (5):307–323. [ Google Scholar ]

- Djonov Emilia. Website hierarchy and the interaction between content organization, webpage and navigation design: A systemic functional hypermedia discourse analysis perspective. Information Design Journal. 2007; 15 (2):144–162. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duggan M, Ellison N, Lampe C, Lenhart A, Smith A. Social Media update 2014. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flavián Carlos, Guinalíu Miguel, Gurrea Raquel. The role played by perceived usability, satisfaction and consumer trust on website loyalty. Information & Management. 2006; 43 (1):1–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- George Carole A. Usability testing and design of a library website: an iterative approach. OCLC Systems & Services: International digital library perspectives. 2005; 21 (3):167–180. [ Google Scholar ]

- Google.com. Bounce Rate. Analyrics Help. 2015 Retrieved 2/11, 2015, from https://support.google.com/analytics/answer/1009409?hl=en .

- Green D, Pearson JM. Development of a web site usability instrument based on ISO 9241-11. Journal of Computer Information Systems. 2006 Fall [ Google Scholar ]

- Horvath Keith J, Ecklund Alexandra M, Hunt Shanda L, Nelson Toben F, Toomey Traci L. Developing Internet-Based Health Interventions: A Guide for Public Health Researchers and Practitioners. J Med Internet Res. 2015; 17 (1):e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3770. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- International Standardization Organization. ISO 2941-11:1998 Ergonomic requirements for office work with visual display terminals (VDTs) -- Part 11: Guidance on usability: International Standardization Organization (ISO) 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Internet Use Over Time. 2014 Jan 2; Retrieved February 15, 2015, from http://www.pewinternet.org/data-trend/internet-use/internet-use-over-time/

- Internet User Demographics. 2013 Nov 14; Retrieved February 11, 2015, from http://www.pewinternet.org/data-trend/internet-use/latest-stats/

- Kim Jinwoo, Lee Jungwon, Han Kwanghee, Lee Moonkyu. Businesses as Buildings: Metrics for the Architectural Quality of Internet Businesses. Information Systems Research. 2002; 13 (3):239–254. doi: 10.1287/isre.13.3.239.79. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee Younghwa, Kozar Kenneth A. Understanding of website usability: Specifying and measuring constructs and their relationships. Decision Support Systems. 2012; 52 (2):450–463. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lim Sun. The Self-Confrontation Interview: Towards an Enhanced Understanding of Human Factors in Web-based Interaction for Improved Website Usability. J Electron Commerce Res. 2002; 3 (3):162–173. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lowry Paul Benjamin, Spaulding Trent, Wells Taylor, Moody Greg, Moffit Kevin, Madariaga Sebastian. A theoretical model and empirical results linking website interactivity and usability satisfaction. Paper presented at the System Sciences, 2006. HICSS’06. Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on.2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maurer Steven D, Liu Yuping. Developing effective e-recruiting websites: Insights for managers from marketers. Business Horizons. 2007; 50 (4):305–314. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mobile Technology Fact Sheet. 2013 Dec 27; Retrieved August 5, 2015, from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/

- Nielsen Jakob. Usability 101: introduction to Usability. 2012 Retrieved 2/11, 2015, from http://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/

- Palmer Jonathan W. Web Site Usability, Design, and Performance Metrics. Information Systems Research. 2002; 13 (2):151–167. doi: 10.1287/isre.13.2.151.88. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Petre Marian, Minocha Shailey, Roberts Dave. Usability beyond the website: an empirically-grounded e-commerce evaluation instrument for the total customer experience. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2006; 25 (2):189–203. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petrie Helen, Hamilton Fraser, King Neil. Tension, what tension?: Website accessibility and visual design. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2004 international cross-disciplinary workshop on Web accessibility (W4A).2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Raward Roslyn. Academic library website design principles: development of a checklist. Australian Academic & Research Libraries. 2001; 32 (2):123–136. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosen Deborah E, Purinton Elizabeth. Website design: Viewing the web as a cognitive landscape. Journal of Business Research. 2004; 57 (7):787–794. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shneiderman Ben, Hochheiser Harry. Universal usability as a stimulus to advanced interface design. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2001; 20 (5):367–376. [ Google Scholar ]

- Song Jaeki, Zahedi Fatemeh “Mariam”. A theoretical approach to web design in e-commerce: a belief reinforcement model. Management Science. 2005; 51 (8):1219–1235. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sutcliffe Alistair. Interactive systems: design, specification, and verification. Springer; 2001. Heuristic evaluation of website attractiveness and usability; pp. 183–198. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tan Gek Woo, Wei Kwok Kee. An empirical study of Web browsing behaviour: Towards an effective Website design. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 2007; 5 (4):261–271. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarafdar Monideepa, Zhang Jie. Determinants of reach and loyalty-a study of Website performance and implications for Website design. Journal of Computer Information Systems. 2008; 48 (2):16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson Lori Foster, Braddy Phillip W, Wuensch Karl L. E-recruitment and the benefits of organizational web appeal. Computers in Human Behavior. 2008; 24 (5):2384–2398. [ Google Scholar ]

- W3schools.com. Browser Statistics and Trends. Retrieved 1/15, 2015, from http://www.w3schools.com/browsers/browsers_stats.asp .

- Williamson Ian O, Lepak David P, King James. The effect of company recruitment web site orientation on individuals’ perceptions of organizational attractiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2003; 63 (2):242–263. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Ping, Small Ruth V, Von Dran Gisela M, Barcellos Silvia. A two factor theory for website design. Paper presented at the System Sciences, 2000. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Hawaii International Conference on.2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Ping, Von Dran Gisela M. Satisfiers and dissatisfiers: A two-factor model for website design and evaluation. Journal of the American society for information science. 2000; 51 (14):1253–1268. [ Google Scholar ]

A Literature Review: Website Design and User Engagement

Affiliations.

- 1 ElevateU, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- 2 University of California Institute for Prediction Technology, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA; UCLA Center for Digital Behavior, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- PMID: 27499833

- PMCID: PMC4974011

Proper design has become a critical element needed to engage website and mobile application users. However, little research has been conducted to define the specific elements used in effective website and mobile application design. We attempt to review and consolidate research on effective design and to define a short list of elements frequently used in research. The design elements mentioned most frequently in the reviewed literature were navigation, graphical representation, organization, content utility, purpose, simplicity, and readability. We discuss how previous studies define and evaluate these seven elements. This review and the resulting short list of design elements may be used to help designers and researchers to operationalize best practices for facilitating and predicting user engagement.

Keywords: Website design; navigation; organization; simplicity; usability.

Grants and funding

- K01 MH090884/MH/NIMH NIH HHS/United States

- R01 MH106415/MH/NIMH NIH HHS/United States

- R21 DA039458/DA/NIDA NIH HHS/United States

A Literature Review: Website Design and User Engagement.

- Garett, Renee ;

- Chiu, Jason ;

- Zhang, Ly ;

- Young, Sean D

Published Web Location

Proper design has become a critical element needed to engage website and mobile application users. However, little research has been conducted to define the specific elements used in effective website and mobile application design. We attempt to review and consolidate research on effective design and to define a short list of elements frequently used in research. The design elements mentioned most frequently in the reviewed literature were navigation, graphical representation, organization, content utility, purpose, simplicity, and readability. We discuss how previous studies define and evaluate these seven elements. This review and the resulting short list of design elements may be used to help designers and researchers to operationalize best practices for facilitating and predicting user engagement.

Many UC-authored scholarly publications are freely available on this site because of the UC's open access policies . Let us know how this access is important for you.

Enter the password to open this PDF file:

A Systematic Review of Adaptive and Responsive Design Approaches for World Wide Web

- Conference paper

- First Online: 27 December 2018

- Cite this conference paper

- Nazish Yousaf 17 ,

- Wasi Haider Butt 17 ,

- Farooque Azam 17 &

- Muhammad Waseem Anwar 17

Part of the book series: Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing ((AISC,volume 887))

Included in the following conference series:

- Future of Information and Communication Conference

1102 Accesses

1 Citations

World Wide Web (WWW) in today’s age is used on different devices. These devices communicate with each other thus creating a design problem of layouts and data mismatch. Consequently, there is a strong need of visualizing and envisioning web data with proper customization suiting different types of users. The purpose of this Systematic Literature Review (SLR) is to investigate the two widely used web based designs i.e. Adaptive Web Design (AWD) and Responsive Web Design (RWD). Particularly, a systematic literature review has been used to identify 58 research works, published during 2009–2017. Consequently, we identify 23 research works regarding AWD, 14 research works related to RWD and 21 research works pertaining to both AWD and RWD. Moreover, 4 significant tools and 13 leading techniques have been identified in the context of AWD and RWD implementation. Finally, significant aspects of two web development approaches (AWD and RWD) are also compared with the traditional web design. It has been concluded that the traditional web design is not sufficient to fulfill the needs of ever-growing web users all around the globe. Therefore, the combination of both AWD and RWD is essential to meet the technological advancements in WWW.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

WEBAPIK: a body of structured knowledge on designing web APIs

Paving the Path to Content-Centric and Device-Agnostic Web Design

Quality of Web Mashups: A Systematic Mapping Study

Roberto, V.: AML: a modeling language for designing adaptive web applications. J. Pers. Ubiquit. Comput. 16 (5), 527–541 (2012)

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Stewart, C.B.: Making it work for everyone HTML5 and CSS Level3 for responsive accessible design on your library website. J. Libr. Inf. Serv. Distance Learn. 8 (3–4), 118–136 (2014)

Google Scholar

Changbo, K., Zhiqiu, H.: Self-adaptive semantic web service matching method. J. Knowl. Based Syst. 35 , 41–48 (2012)

Article Google Scholar

Jia-Jiunn, L., Ya-Chen, C., Shiou-Wen, Y.: Designing an adaptive web-based learning system based on students’ cognitive styles identified online. J. Comput. Educ. 59 (1), 209–222 (2012)

Zhenlong, L., Binghua C.: The design of adaptive web-learning system base on learning behavior monitoring. In: Proceedings of 7th International Conference on Computer Science and Education (ICCSE), Melbourne. IEEE (2012)

Manvi, A.D., Komal K.B.: Design of an ontology based adaptive crawler for hidden web. In: International Conference in Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT 2013), Gwalior. IEEE (2013)

Carlos, G., Carlos, J., Ramon P.: Improving web cache performance via adaptive content fragmentation design. In: 10th IEEE International Symposium on Network Computing and Applications (NCA 2011), Cambridge. IEEE (2011)

Bin, Z.: Responsive design e-learning site transformation. In: 4th International Conference on Networking and Distributed Computing (ICNDC 2013), Los Angeles. IEEE (2013)

Bijan, B.G.: Culturally responsive educational web sites. J. Educ. Media Int. 37 (3), 185–195 (2010)

Luca, L.: Formalising human mental workload as non-monotonic concept for adaptive and personalised web-design. In: International Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation, and Personalization (UMAP) 2012. LNCS, vol. 7379, pp 369–373. Springer (2012)

Nancy, R.G., Phil, S.: One site fits all: responsive web design. J. Electron. Resour. Med. Libr. 11 (2), 78–90 (2014)

Ioannis, M., Stavros, D., Anastasios, K.: Adaptive and intelligent systems for collaborative learning support: a review of the field. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 4 (1), 5–20 (2011)

Mohorovičić, S.: Implementing responsive web design for enhanced web presence. In: 36th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO 2013), Opatija. IEEE (2013)

Jari-Pekka, V., Jaakko, S., Tommi M.: On the design of a responsive user interface for a multi-device web service. In: 2nd ACM International Conference on Mobile Software Engineering and Systems (MOBILEsoft 2015), Florence. ACM (2015)

Mohammed, S., Mohammed, R., Mostafa, B.: Towards minimizing author’s effort during designing the domain model of adaptive web-based educational system. In: 8th International Conference on Intelligent Systems: Theories and Applications (SITA 2013), Rabat. IEEE (2013)

Gu, W., Liu, J.: Web-based adaptive intelligent learning system design and implementation. In: International Conference on Information, Networking and Automation (ICINA), Kunming. IEEE (2010)

Aqueasha, M.H., Abdullah, A., Catherine, H., Amy K.H.: Understanding design considerations for adaptive user interfaces for accessible pointing with older and younger adults. In: Proceedings of the 12th Web for All Conference (W4A 2015), New York. ACM (2015)

Ramón, H., José, B.: Towards the ubiquitous visualization: adaptive user-interfaces based on the semantic web. J. Interact. Comput. 23 , 40–56 (2011)

Vlad, S., Yu, Y.: Experiences designing hypermedia-driven and self-adaptive web-based AR authoring tools. In: Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on RESTful Design (WS-REST 2012), New York. ACM (2012)

Federica, C., Antonina, D., Pasquale, L., Julita, V.: Perspectives in semantic adaptive social web. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 4 (4), 59 (2013)

Bilal, L.B., Gede, P., Halizah, B.B.: ULUL-ILM the design of web-based adaptive educational hypermedia system based on learning style. In: 13th International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications (ISDA 2013), Bangi. IEEE (2013)

Liu, X., Han, H.: The design and realization of web-based adaptive learning system. In: 2nd International Conference on Networking and Digital Society (ICNDS 2010), Wenzhou. IEEE (2010)

Wei, J., Meng, Z., Bin, Z., Yujian, J., Yingwei, Z.: Responsive web design mode and application. In: IEEE Workshop on Advanced Research and Technology in Industry Applications (WARTIA 2014), Ottawa. IEEE (2014)

Jeonghyun, L., Imsu, L., Iseul, K., Hyejin, Y., Jongwon, L., Mansung, J., Hyenki, K.: Responsive web design according to the resolution. In: 8th International Conference on u- and e-Service, Science and Technology (UNESST 2015), Jeju. IEEE (2015)

Jacob, D., Bert, V., Tele, T.: Enhancing accessibility to web mapping systems with technology aligned adaptive profiles. Int. J. Dig. Earth 7 (4), 256–278 (2014)

Fabio, P., Christian, S.: Model-based customizable adaptation of web applications for vocal browsing. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (SIGDOC 2011), pp. 83–90, Pisa. ACM (2011)

Anne, S.: Responsive web design for libraries A LITA guide. J. Hosp. Librariansh. 64 (2), 159–160 (2015)

Eva, H., Paul, K., Steven, L., Norbert, S.: Responsive Web Design. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2011)

Ezwan, S.A.M., Zulkefli, M., Norfadillah, K.: Adaptation of usability principles in responsive web design technique for e-commerce development. In: 5th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI 2015), Denpasar. IEEE (2015)

Wang, H., Liu, X.: Adaptive site design based on web mining and topology. In: World Congress on Computer Science and Information Engineering WRI 2009, Los Angeles. IEEE (2009)

Katerina, P., Stephanos, M.: Developing adaptive e-Learning systems based on Web 2.0. In: International Conference on Information Society (i-Society 2012), London. IEEE (2012)

Guo, L., Hua, Q.Y., Wang, P., Yu, K., Wang, K., Xu, J.: A model-based responsive web user interface. In: 6th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS 2015), Beijing. IEEE (2015)

Evgeny, K., Paul, D.B., Mykola, P.: AH 12 years later: a comprehensive survey of adaptive hypermedia methods and techniques. J. New Rev. Hypermed. Multimed. 15 (1), 5–38 (2009)

Yoann, B., Marianne, H., Michel, M.: Reconciling user and designer preferences in adapting web pages for people with low vision. In: Proceedings of the 12th Web for All Conference (W4A 2015), Florence. ACM (2015)

Kunyanuth, K., Pubet, K., Pattarapan, R.: Developing an adaptive web-based intelligent tutoring system using mastery learning technique. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 191 , 686–691 (2015)

Quan, Z.S., Boualem, B., Zakaria, M., Anne, H.N.: Configurable composition and adaptive provisioning of web services. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2 (1), 34–49 (2009)

Jàn, A.: Beyond adaptive web design. IEEE (2014)

Bujar, R., Mexhid, F., Xhemal, Z., Jaumin, A., Florije, I.: Methods and techniques of adaptive web accessibility for the blind and visually impaired. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 195 , 1999–2007 (2015)

Bo, M., Bin, C., Xiaoying, B., Junfei, H.: Design of BDI agent for adaptive performance testing of web services. In: Proceedings of 10th International Conference on Quality Software, Zhangjiajie. IEEE (2010)

Meltem, H.B., Murat, B.: Responsive web design-a new type of design for web-based instructional content. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 106 , 2275–2279 (2013)

Jian, Y., Quan, Z.S., Joshua, K.Y.S., Han, J., Liu, C., Noor, T.N.: Model-driven development of adaptive web service processes with aspects and rules. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 81 , 533–552 (2015)

Cristóbal, R., Sebastián, V., Amelia, Z., de Paul, B.: Applying web usage mining for personalizing hyperlinks in web-based adaptive educational systems. J. Comput. Educ. 53 , 828–840 (2009)

Nicolas, P., Toni, M., Josep, L.B., Ricard, G., Jordi, T.: Self-adaptive utility-based web session management. J. Comput. Netw. 53 , 1712–1721 (2009)

Evangelos, S., Antoniou, D., Poulia, A., Athanasios, T.: A web personalizing technique using adaptive data structures: the case of bursts in web visits. J. Syst. Softw. 83 (11), 2200–2210 (2010)

Quang-Dung, V., Danh-Viet, V., Ha-Thanh, N.P.B., Viet-Ha, N., Nobuyasu, N.: Adaptive web page layout for mobile devices. In: International Conference on Computing, Management and Telecommunications (ComManTel 2014), Da Nang. IEEE (2014)

Sowmya, S., Ravitheja, T., Joy, B.: Rendering on browsers responsive to user head. In: Annual India Conference (INDICON 2014), Pune. IEEE (2014)

Shengbo, C., Huaikou, M., Bo, S., Yihai, C.: Towards practical modeling of web applications and generating tests. In: IEEE 4th International Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Software Engineering (TASE 2010), Taipei. IEEE (2010)

Sowmya, S., Ravitheja, T., Joy, B.: Responsive, adaptive and user personalized rendering on mobile browsers. In: International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI 2014), New Delhi. IEEE (2014)

Stephen, S.Y., Nong, Y., Hessam, S.S., Dazhi, H., Auttawut, R., Mustafa, G.B., Mohammed, A.M.: Toward development of adaptive service-based software systems. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2 (3), 247–260 (2009)

Tiago, C.N., Deller, J.F., Sérgio, T.C., Luciana, O.B.: Evaluating responsive web design’s impact on blind users. IEEE Multimedia 24 (2), 86–95 (2017)

Maryam, A.A., John, H.C., Carla, B.Z., Dimitrios, P.: An adaptive educational web application for engineering students. IEEE Access 5 , 359–365 (2017)

Wenhui, P., Yaling, Z.: The design and research of responsive web supporting mobile learning devices. In: International Symposium on Educational Technology (ISET 2015), Wuhan. IEEE (2015)

Yahya, M.T., Majd, S., Manar, F., Walaa, S., Mohammad, A.A.: Adaptive e-learning web-based English tutor using data mining techniques and Jackson’s learning styles. In: 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS 2017), Irbid. IEEE (2017)

Yingzi, L., Jeffrey, B., Mura, I., David, S.: An adaptive interface design (AID) for enhanced computer accessibility and rehabilitation. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 98 (C), 14–23 (2017)

Xuan-zhe, L., Mengwei, X., Teng, T., Gang, H., Hong, M.: MUIT: a domain-specific language and its middleware for adaptive mobile web-based user interfaces in WS-BPEL. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. PP (99), 1 (2016)

Azlan, Y., Moamin, A.M., Mohd, S.A.: A conceptual multi-agent semantic web model of a self-adaptive website for intelligent strategic marketing in learning institutions. In: 2nd International Symposium on Agent, Multi-Agent Systems and Robotics (ISAMSR 2016), Bangi. IEEE (2016)

Tilman, D., Ted, S.: On the importance of spatial perception for the design of adaptive user interfaces. In: IEEE 10th International Conference on Self-Adaptive and Self-Organizing Systems (SASO 2016), Augsburg. IEEE (2016)

Kitchenham, B: Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews, Keele University TR/SE-0401/NICTA, Technical Report 0400011T (2004)

Brusilovsky, P.: Adaptive Hypermedia (2001)

Search Process Search terms. http://ceme.nust.edu.pk/ISEGROUP/Resources/slra/slr.html

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Computer and Software Engineering, College of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering (EME), National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST), Islamabad, Pakistan

Nazish Yousaf, Wasi Haider Butt, Farooque Azam & Muhammad Waseem Anwar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nazish Yousaf .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Science and Engineering, Saga University, Saga, Japan

The Science and Information (SAI) Organization, Bradford, West Yorkshire, UK

Supriya Kapoor

The Science and Information (SAI) Organization, New Delhi, India

Rahul Bhatia

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Yousaf, N., Butt, W.H., Azam, F., Anwar, M.W. (2019). A Systematic Review of Adaptive and Responsive Design Approaches for World Wide Web. In: Arai, K., Kapoor, S., Bhatia, R. (eds) Advances in Information and Communication Networks. FICC 2018. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 887. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03405-4_50

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03405-4_50

Published : 27 December 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-03404-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-03405-4

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

This paper is in the following e-collection/theme issue:

Published on 24.10.2019 in Vol 3 , No 4 (2019) : Oct-Dec

A Comprehensive Framework to Evaluate Websites: Literature Review and Development of GoodWeb

Authors of this article:

- Rosalie Allison, BSc, MSc ;

- Catherine Hayes, BSc ;

- Cliodna A M McNulty, MBBS, FRCP ;

- Vicki Young, BSc, PhD

Public Health England, Gloucester, United Kingdom

Corresponding Author:

Rosalie Allison, BSc, MSc

Public Health England

Primary Care and Interventions Unit

Gloucester, GL1 1DQ

United Kingdom

Phone: 44 0208 495 3258

Email: [email protected]

Background: Attention is turning toward increasing the quality of websites and quality evaluation to attract new users and retain existing users.

Objective: This scoping study aimed to review and define existing worldwide methodologies and techniques to evaluate websites and provide a framework of appropriate website attributes that could be applied to any future website evaluations.

Methods: We systematically searched electronic databases and gray literature for studies of website evaluation. The results were exported to EndNote software, duplicates were removed, and eligible studies were identified. The results have been presented in narrative form.

Results: A total of 69 studies met the inclusion criteria. The extracted data included type of website, aim or purpose of the study, study populations (users and experts), sample size, setting (controlled environment and remotely assessed), website attributes evaluated, process of methodology, and process of analysis. Methods of evaluation varied and included questionnaires, observed website browsing, interviews or focus groups, and Web usage analysis. Evaluations using both users and experts and controlled and remote settings are represented. Website attributes that were examined included usability or ease of use, content, design criteria, functionality, appearance, interactivity, satisfaction, and loyalty. Website evaluation methods should be tailored to the needs of specific websites and individual aims of evaluations. GoodWeb, a website evaluation guide, has been presented with a case scenario.

Conclusions: This scoping study supports the open debate of defining the quality of websites, and there are numerous approaches and models to evaluate it. However, as this study provides a framework of the existing literature of website evaluation, it presents a guide of options for evaluating websites, including which attributes to analyze and options for appropriate methods.

Introduction

Since its conception in the early 1990s, there has been an explosion in the use of the internet, with websites taking a central role in diverse fields such as finance, education, medicine, industry, and business. Organizations are increasingly attempting to exploit the benefits of the World Wide Web and its features as an interface for internet-enabled businesses, information provision, and promotional activities [ 1 , 2 ]. As the environment becomes more competitive and websites become more sophisticated, attention is turning toward increasing the quality of the website itself and quality evaluation to attract new and retain existing users [ 3 , 4 ]. What determines website quality has not been conclusively established, and there are many different definitions and meanings of the term quality, mainly in relation to the website’s purpose [ 5 ]. Traditionally, website evaluations have focused on usability, defined as “the extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use [ 6 ].” The design of websites and users’ needs go beyond pure usability, as increased engagement and pleasure experienced during interactions with websites can be more important predictors of website preference than usability [ 7 - 10 ]. Therefore, in the last decade, website evaluations have shifted their focus to users’ experience, employing various assessment techniques [ 11 ], with no universally accepted method or procedure for website evaluation.

This scoping study aimed to review and define existing worldwide methodologies and techniques to evaluate websites and provide a simple framework of appropriate website attributes, which could be applied to future website evaluations.

A scoping study is similar to a systematic review as it collects and reviews content in a field of interest. However, scoping studies cover a broader question and do not rigorously evaluate the quality of the studies included [ 12 ]. Scoping studies are commonly used in the fields of public services such as health and education, as they are more rapid to perform and less costly in terms of staff costs [ 13 ]. Scoping studies can be precursors to a systematic review or stand-alone studies to examine the range of research around a particular topic.

The following research question is based on the need to gain knowledge and insight from worldwide website evaluation to inform the future study design of website evaluations: what website evaluation methodologies can be robustly used to assess users’ experience?

To show how the framework of attributes and methods can be applied to evaluating a website, e-Bug, an international educational health website, will be used as a case scenario [ 14 ].

This scoping study followed a 5-stage framework and methodology, as outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [ 12 ], involving the following: (1) identifying the research question, as above; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Identifying Relevant Studies

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [ 15 ], studies for consideration in the review were located by searching the following electronic databases: Excerpta Medica dataBASE, PsycINFO, Cochrane, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Scopus, ACM digital library, and IEEE Xplore SPORTDiscus. The keywords used referred to the following:

- Population: websites

- Intervention: evaluation methodologies

- Outcome: user’s experience.

Table 1 shows the specific search criteria for each database. These keywords were also used to search gray literature for unpublished or working documents to minimize publication bias.

a EMBASE: Excerpta Medica database.

b CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

c ACM: Association for Computing Machinery.

d IEEE: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

Study Selection

Once all sources had been systematically searched, the list of citations was exported to EndNote software to identify eligible studies. By scanning the title, and abstract if necessary, studies that did not fit the inclusion criteria were removed by 2 researchers (RA and CH). As abstracts are not always representative of the full study that follows or capture the full scope [ 16 ], if the title and abstract did not provide sufficient information, the full manuscript was examined to ascertain whether they met all the inclusion criteria, which included (1) studies focused on websites, (2) studies of evaluative methods (eg, use of questionnaire and task completion), (3) studies that reported outcomes that affect the user’s experience (eg, quality, satisfaction, efficiency, effectiveness without necessarily focusing on methodology), (4) studies carried out between 2006 and 2016, (5) studies published in English, and (6) type of study (any study design that is appropriate).

Exclusion criteria included (1) studies that focus on evaluations using solely experts and are not transferrable to user evaluations; (2) studies that are in the form of electronic book or are not freely available on the Web or through OpenAthens, the University of Bath library, or the University of the West of England library; (3)studies that evaluate banking, electronic commerce (e-commerce), or online libraries’ websites and do not have transferrable measures to a range of other websites; (4) studies that report exclusively on minority or special needs groups (eg, blind or deaf users); and (5) studies that do not meet all the inclusion criteria.

Charting the Data

The next stage involved charting key items of information obtained from studies being reviewed. Charting [ 17 ] describes a technique for synthesizing and interpreting qualitative data by sifting, charting, and sorting material according to key issues and themes. This is similar to a systematic review in which the process is called data extraction. The data extracted included general information about the study and specific information relating to, for instance, the study population or target, the type of intervention, outcome measures employed, and the study design.

The information of interest included the following: type of website, aim or purpose of the study, study populations (users and experts), sample size, setting (laboratory, real life, and remotely assessed), website attributes evaluated, process of methodology, and process of analysis.

NVivo version 10.0 software was used for this stage by 2 researchers (RA and CH) to chart the data.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Although the scoping study does not seek to assess the quality of evidence, it does present an overview of all material reviewed with a narrative account of findings.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

As no primary research was carried out, no ethical approval was required to undertake this scoping study. No specific reference was made to any of the participants in the individual studies, nor does this study infringe on their rights in any way.

The electronic database searches produced 6657 papers; a further 7 papers were identified through other sources. After removing duplicates (n=1058), 5606 publications remained. After titles and abstracts were examined, 784 full-text papers were read and assessed further for eligibility. Of those, 69 articles were identified as suitable by meeting all the inclusion criteria ( Figure 1 ).

Study Characteristics

Studies referred to or used a mixture of users (72%) and experts (39%) to evaluate their websites; 54% used a controlled environment, and 26% evaluated websites remotely ( Multimedia Appendix 1 [ 2 - 4 , 11 , 18 - 85 ]). Remote usability, in its most basic form, involves working with participants who are not in the same physical location as the researcher, employing techniques such as live screen sharing or questionnaires. Advantages to remote website evaluations include the ability to evaluate using a larger number of participants as travel time and costs are not a factor, and participants are able to partake at a time that is appropriate to them, increasing the likelihood of participation and the possibility of a greater diversity of participants [ 18 ]. However, the disadvantages of remote website evaluations, in comparison with a controlled setting, are that system performance, network traffic, and the participant’s computer setup can all affect the results.

A variety of types of websites evaluated were included in this review including government (9%), online news (6%), education (1%), university (12%), and sports organizations (4%). The aspects of quality considered, and their relative importance varied according to the type of website and the goals to be achieved by the users. For example, criteria such as ease of paying or security are not very important to educational websites, whereas they are especially important for online shopping. In this sense, much attention must be paid when evaluating the quality of a website, establishing a specific context of use and purpose [ 19 ].

The context of the participants was also discussed, in relation to the generalizability of results. For example, when evaluations used potential or current users of their website, it was important that computer literacy was reflective of all users [ 20 ]. This could mean ensuring that participants with a range of computer abilities and experiences were used so that results were not biased to the most or least experienced users.

Intervention

A total of 43 evaluation methodologies were identified in the 69 studies in this review. Most of them were variations of similar methodologies, and a brief description of each is provided in Multimedia Appendix 2 . Multimedia Appendix 3 shows the methods used or described in each study.

Questionnaire

Use of questionnaires was the most common methodology referred to (37/69, 54%), including questions to rank or rate attributes and open questions to allow text feedback and suggested improvements. Questionnaires were used in a combination of before or after usability testing to assess usability and overall user experience.

Observed Browsing the Website

Browsing the website using a form of task completion with the participant, such as cognitive walkthrough, was used in 33/69 studies (48%), whereby an expert evaluator used a detailed procedure to simulate task execution and browse all particular solution paths, examining each action while determining if expected user’s goals and memory content would lead to choosing a correct option [ 30 ]. Screen capture was often used (n=6) to record participants’ navigation through the website, and eye tracking was used (n=7) to assess where the eye focuses on each page or the motion of the eye as an individual views a Web page. The think-aloud protocol was used (n=10) to encourage users to express out loud what they were looking at, thinking, doing, and feeling, as they performed tasks. This allows observers to see and understand the cognitive processes associated with task completion. Recording the time to complete tasks (n=6) and mouse movement or clicks (n=8) were used to assess the efficiency of the websites.

Qualitative Data Collection

Several forms of qualitative data collection were used in 27/69 studies (39%). Observed browsing, interviews, and focus groups were used either before or after the use of the website. Pre-website-use, qualitative research was often used to collect details of which website attributes were important for participants or what weighting participants would give to each attribute. Postevaluation, qualitative techniques were used to collate feedback on the quality of the website and any suggestions for improvements.

Automated Usability Evaluation Software

In 9/69 studies (13%), automated usability evaluation focused on developing software, tools, and techniques to speed evaluation (rapid), tools that reach a wider audience for usability testing (remote), and tools that have built-in analyses features (automated). The latter can involve assessing server logs, website coding, and simulations of user experience to assess usability [ 42 ].

Card Sorting

A technique that is often linked with assessing navigability of a website, card sorting, is useful for discovering the logical structure of an unsorted list of statements or ideas by exploring how people group items and structures that maximize the probability of users finding items (5/69 studies, 7%). This can assist with determining effective website structure.

Web Usage Analysis

Of 69 studies, 3 studies used Web usage analysis or Web analytics to identify browsing patterns by analyzing the participants’ navigational behavior. This could include tracking at the widget level, that is, combining knowledge of the mouse coordinates with elements such as buttons and links, with the layout of the HTML pages, enabling complete tracking of all user activity.

Outcomes (Attributes Used to Evaluate Websites)

Often, different terminology for website attributes was used to describe the same or similar concepts ( Multimedia Appendix 4 ). The most used website attributes that were assessed can be broken down into 8 broad categories and further subcategories:

- Usability or ease of use is the degree to which a website can be used to achieve given goals (n=58). It includes navigation such as intuitiveness, learnability, memorability, and information architecture; effectiveness such as errors; and efficiency.

- Content (n=41) includes completeness, accuracy, relevancy, timeliness, and understandability of the information.

- Web design criteria (n=29) include use of media, search engines, help resources, originality of the website, site map, user interface, multilanguage, and maintainability.

- Functionality (n=31) includes links, website speed, security, and compatibility with devices and browsers.

- Appearance (n=26) includes layout, font, colors, and page length.

- Interactivity (n=25) includes sense of community, such as ability to leave feedback and comments and email or share with a friend option or forum discussion boards; personalization; help options such as frequently answered questions or customer services; and background music.

- Satisfaction (n=26) includes usefulness, entertainment, look and feel, and pleasure.

- Loyalty (n=8) includes first impression of the website.

GoodWeb: Website Evaluation Guide

As there was such a range of methods used, a suggested guide of options for evaluating websites is presented below ( Figure 2 ), coined GoodWeb, and applied to an evaluation of e-Bug, an international educational health website [ 14 ]. Allison at al [ 86 ] show the full details of how GoodWeb has been applied and outcomes of the e-Bug website evaluation.

Step 1. What Are the Important Website Attributes That Affect User's Experience of the Chosen Website?

Usability or ease of use, content, Web design criteria, functionality, appearance, interactivity, satisfaction, and loyalty were the umbrella terms that encompassed the website attributes identified or evaluated in the 69 studies in this scoping study. Multimedia Appendix 4 contains a summary of the most used website attributes that have been assessed. Recent website evaluations have shifted focus from usability of websites to an overall user’s experience of website use. A decision on which website attributes to evaluate for specific websites could come from interviews or focus groups with users or experts or a literature search of attributes used in similar evaluations.

Application

In the scenario of evaluating e-Bug or similar educational health websites, the attributes chosen to assess could be the following:

- Appearance: colors, fonts, media or graphics, page length, style consistency, and first impression

- Content: clarity, completeness, current and timely information, relevance, reliability, and uniqueness

- Interactivity: sense of community and modern features

- Ease of use: home page indication, navigation, guidance, and multilanguage support

- Technical adequacy: compatibility with other devices, load time, valid links, and limited use of special plug-ins

- Satisfaction: loyalty

These cover the main website attributes appropriate for an educational health website. If the website did not currently have features such as search engines, site map, background music, it may not be appropriate to evaluate these, but may be better suited to question whether they would be suitable additions to the website; or these could be combined under the heading modern features . Furthermore, security may not be a necessary attribute to evaluate if participant identifiable information or bank details are not needed to use the website.

Step 2. What Is the Best Way to Evaluate These Attributes?

Often, a combination of methods is suitable to evaluate a website, as 1 method may not be appropriate to assess all attributes of interest [ 29 ] (see Multimedia Appendix 3 for a summary of the most used methods for evaluating websites). For example, screen capture of task completion may be appropriate to assess the efficiency of a website but would not be the chosen method to assess loyalty. A questionnaire or qualitative interview may be more appropriate for this attribute.

In the scenario of evaluating e-Bug, a questionnaire before browsing the website would be appropriate to rank the importance of the selected website attributes, chosen in step 1. It would then be appropriate to observe browsing of the website, collecting data on completion of typical task scenarios, using the screen capture function for future reference. This method could be used to evaluate the effectiveness (number of tasks successfully completed), efficiency (whether the most direct route through the website was used to complete the task), and learnability (whether task completion is more efficient or effective second time of trying). It may then be suitable to use a follow-up questionnaire to rate e-Bug against the website attributes previously ranked. The attribute ranking and rating could then be combined to indicate where the website performs well and areas for improvement.

Step 3: Who Should Evaluate the Website?

Both users and experts can be used to evaluate websites. Experts are able to identify areas for improvements, in relation to usability; whereas, users are able to appraise quality as well as identify areas for improvement. In this respect, users are able to fully evaluate user’s experience, where experts may not be able to.

For this reason, it may be more appropriate to use current or potential users of the website for the scenario of evaluating e-Bug.

Step 4: What Setting Should Be Used?

A combination of controlled and remote settings can be used, depending on the methods chosen. For example, it may be appropriate to collect data via a questionnaire, remotely, to increase sample size and reach a more diverse audience, whereas a controlled setting may be more appropriate for task completion using eye-tracking methods.

Strengths and Limitations

A scoping study differs from a systematic review, in that it does not critically appraise the quality of the studies before extracting or charting the data. Therefore, this study cannot compare the effectiveness of the different methods or methodologies in evaluating the website attributes. However, what it does do is review and summarize a huge amount of literature, from different sources, in a format that is understandable and informative for future designs of website evaluations.

Furthermore, studies that evaluate banking, e-commerce, or online libraries’ websites and do not have transferrable measures to a range of other websites were excluded from this study. This decision was made to limit the number of studies that met the remaining inclusion criteria, and it was deemed that the website attributes for these websites would be too specialist and not necessarily transferable to a range of websites. Therefore, the findings of this study may not be generalizable to all types of website. However, Multimedia Appendix 1 shows that data were extracted from a very broad range of websites when it was deemed that the information was transferrable to a range of other websites.

A robust website evaluation can identify areas for improvement to both fulfill the goals and desires of its users [ 62 ] and influence their perception of the organization and overall quality of resources [ 48 ]. An improved website could attract and retain more online users; therefore, an evidence-based website evaluation guide is essential.

Conclusions

This scoping study emphasizes the fact that the debate about how to define the quality of websites remains open, and there are numerous approaches and models to evaluate it. Multimedia Appendix 2 shows existing methodologies or tools that can be used to evaluate websites. Many of these are variations of similar approaches; therefore, it is not strictly necessary to use these tools at face value; however, some could be used to guide analysis, following data collection. By following steps 1 to 4 of GoodWeb, the framework suggested in this study, taking into account the desired participants and setting and website evaluation methods, can be tailored to the needs of specific websites and individual aims of evaluations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Primary Care Unit, Public Health England. This study is not applicable as secondary research.

Authors' Contributions

RA wrote the protocol with input from CH, CM, and VY. RA and CH conducted the scoping review. RA wrote the final manuscript with input from CH, CM, and VY. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Summary of included studies, including information on the participant.

Interventions: methodologies and tools to evaluate websites.

Methods used or described in each study.

Summary of the most used website attributes evaluated.

- Straub DW, Watson RT. Research Commentary: Transformational Issues in Researching IS and Net-Enabled Organizations. Info Syst Res 2001;12(4):337-345. [ CrossRef ]

- Bairamzadeh S, Bolhari A. Investigating factors affecting students' satisfaction of university websites. In: 2010 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology. 2010 Presented at: ICCSIT'10; July 9-11, 2010; Chengdu, China p. 469-473. [ CrossRef ]

- Fink D, Nyaga C. Evaluating web site quality: the value of a multi paradigm approach. Benchmarking 2009;16(2):259-273. [ CrossRef ]

- Markaki OI, Charilas DE, Askounis D. Application of Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process to Evaluate the Quality of E-Government Web Sites. In: Proceedings of the 2010 Developments in E-systems Engineering. 2010 Presented at: DeSE'10; September 6-8, 2010; London, UK p. 219-224. [ CrossRef ]

- Eysenbach G, Powell J, Kuss O, Sa E. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the world wide web: a systematic review. J Am Med Assoc 2002;287(20):2691-2700. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 9241-11: Ergonomic Requirements for Office Work with Visual Display Terminals (VDTs): Part 11: Guidance on Usability. Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization; 1998.

- Hartmann J, Sutcliffe A, Angeli AD. Towards a theory of user judgment of aesthetics and user interface quality. ACM Trans Comput-Hum Interact 2008;15(4):1-30. [ CrossRef ]

- Bargas-Avila JA, Hornbæk K. Old Wine in New Bottles or Novel Challenges: A Critical Analysis of Empirical Studies of User Experience. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2011 Presented at: CHI'11; May 7-12, 2011; Vancouver, BC, Canada p. 2689-2698. [ CrossRef ]

- Hassenzahl M, Tractinsky N. User experience - a research agenda. Behav Info Technol 2006;25(2):91-97. [ CrossRef ]

- Aranyi G, van Schaik P. Testing a model of user-experience with news websites. J Assoc Soc Inf Sci Technol 2016;67(7):1555-1575. [ CrossRef ]

- Tsai W, Chou W, Lai C. An effective evaluation model and improvement analysis for national park websites: a case study of Taiwan. Tour Manag 2010;31(6):936-952. [ CrossRef ]

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method 2005;8(1):19-32. [ CrossRef ]

- Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Syst 2008;6:7 [ FREE Full text ] [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- e-Bug. 2018. Welcome to the e-Bug Teachers Area! URL: https://e-bug.eu/eng_home.aspx?cc=eng&ss=1&t=Welcome%20to%20e-Bug [accessed 2019-08-23]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000100 [ FREE Full text ] [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Badger D, Nursten J, Williams P, Woodward M. Should All Literature Reviews be Systematic? Eval Res Educ 2000;14(3-4):220-230. [ CrossRef ]

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess B, editors. Analyzing Qualitative Data. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge; 2002:187-208.

- Thomsett-Scott BC. Web site usability with remote users: Formal usability studies and focus groups. J Libr Adm 2006;45(3-4):517-547. [ CrossRef ]

- Moreno JM, Morales del Castillo JM, Porcel C, Herrera-Viedma E. A quality evaluation methodology for health-related websites based on a 2-tuple fuzzy linguistic approach. Soft Comput 2010;14(8):887-897. [ CrossRef ]

- Alva M, Martínez A, Labra Gayo J, Del Carmen Suárez M, Cueva J, Sagástegui H. Proposal of a tool of support to the evaluation of user in educative web sites. 2008 Presented at: 1st World Summit on the Knowledge Society, WSKS 2008; 2008; Athens p. 149-157. [ CrossRef ]

- Usability: Home. Usability Evaluation Basics URL: https://www.usability.gov/what-and-why/usability-evaluation.html [accessed 2019-08-24]

- AddThis: Get more likes, shares and follows with smart. 10 Criteria for Better Website Usability: Heuristics Cheat Sheet URL: http://www.addthis.com/blog/2015/02/17/10-criteria-for-better-website-usability-heuristics-cheat-sheet/#.V712QfkrJD8 [accessed 2019-08-24]

- Akgül Y. Quality evaluation of E-government websites of Turkey. In: Proceedings of the 2016 11th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies. 2016 Presented at: CISTI'16; June 15-18 2016; Las Palmas, Spain p. 1-7. [ CrossRef ]

- Al Zaghoul FA, Al Nsour AJ, Rababah OM. Ranking Quality Factors for Measuring Web Service Quality. In: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Intelligent Semantic Web-Services and Applications. 2010 Presented at: 1st ACM Jordan Professional Chapter ISWSA Annual - International Conference on Intelligent Semantic Web-Services and Applications, ISWSA'10; June 14-16, 2010; Amman, Jordan. [ CrossRef ]

- Alharbi A, Mayhew P. Users' Performance in Lab and Non-lab Enviornments Through Online Usability Testing: A Case of Evaluating the Usability of Digital Academic Libraries' Websites. In: 2015 Science and Information Conference. 2015 Presented at: SAI'15; July 28-30, 2015; London, UK p. 151-161. [ CrossRef ]

- Aliyu M, Mahmud M, Md Tap AO. Preliminary Investigation of Islamic Websites Design & Content Feature: A Heuristic Evaluation From User Perspective. In: Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on User Science and Engineering. 2010 Presented at: iUSEr'10; December 13-15, 2010; Shah Alam, Malaysia p. 262-267. [ CrossRef ]

- Aliyu M, Mahmud M, Tap AO, Nassr RM. Evaluating Design Features of Islamic Websites: A Muslim User Perception. In: Proceedings of the 2013 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for the Muslim World. 2013 Presented at: ICT4M'13; March 26-27, 2013; Rabat, Morocco. [ CrossRef ]

- Al-Radaideh QA, Abu-Shanab E, Hamam S, Abu-Salem H. Usability evaluation of online news websites: a user perspective approach. World Acad Sci Eng Technol 2011;74:1058-1066 [ FREE Full text ]

- Aranyi G, van Schaik P, Barker P. Using think-aloud and psychometrics to explore users’ experience with a news web site. Interact Comput 2012;24(2):69-77. [ CrossRef ]

- Arrue M, Fajardo I, Lopez JM, Vigo M. Interdependence between technical web accessibility and usability: its influence on web quality models. Int J Web Eng Technol 2007;3(3):307-328. [ CrossRef ]

- Arrue M, Vigo M, Abascal J. Quantitative metrics for web accessibility evaluation. 2005 Presented at: Proceedings of the ICWE 2005 Workshop on Web Metrics and Measurement; 2005; Sydney.

- Atterer R, Wnuk M, Schmidt A. Knowing the User's Every Move: User Activity Tracking for Website Usability Evaluation and Implicit Interaction. In: Proceedings of the 15th international conference on World Wide. 2006 Presented at: WWW'06; May 23-26, 2006; Edinburgh, Scotland p. 203-212. [ CrossRef ]

- Bahry F, Masrom M, Masrek M. Website evaluation measures, website user engagement and website credibility for municipal website. ARPN J Eng Appl Sci 2015;10(23):18228-18238. [ CrossRef ]

- Bañón-Gomis A, Tomás-Miquel JV, Expósito-Langa M. Improving user experience: a methodology proposal for web usability measurement. In: Strategies in E-Business: Positioning and Social Networking in Online Markets. New York City: Springer US; 2014:123-145.

- Barnes SJ, Vidgen RT. Data triangulation and web quality metrics: a case study in e-government. Inform Manag 2006;43(6):767-777. [ CrossRef ]

- Bolchini D, Garzotto F. Quality of Web Usability Evaluation Methods: An Empirical Study on MiLE+. In: Proceedings of the 2007 international conference on Web information systems engineering. 2007 Presented at: WISE'07; December 3-3, 2007; Nancy, France p. 481-492. [ CrossRef ]

- Chen FH, Tzeng G, Chang CC. Evaluating the enhancement of corporate social responsibility websites quality based on a new hybrid MADM model. Int J Inf Technol Decis Mak 2015;14(03):697-724. [ CrossRef ]

- Cherfi SS, Tuan AD, Comyn-Wattiau I. An Exploratory Study on Websites Quality Assessment. In: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Conceptual Modeling Workshops. 2013 Presented at: ER'13; November 11-13, 2014; Hong Kong, China p. 170-179. [ CrossRef ]

- Chou W, Cheng Y. A hybrid fuzzy MCDM approach for evaluating website quality of professional accounting firms. Expert Sys Appl 2012;39(3):2783-2793. [ CrossRef ]

- Churm T. Usability Geek. 2012 Jul 9. An Introduction To Website Usability Testing URL: http://usabilitygeek.com/an-introduction-to-website-usability-testing/ [accessed 2019-08-24]

- Demir Y, Gozum S. Evaluation of quality, content, and use of the web site prepared for family members giving care to stroke patients. Comput Inform Nurs 2015 Sep;33(9):396-403. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Dominic P, Jati H, Hanim S. University website quality comparison by using non-parametric statistical test: a case study from Malaysia. Int J Oper Res 2013;16(3):349-374. [ CrossRef ]

- Elling S, Lentz L, de Jong M, van den Bergh H. Measuring the quality of governmental websites in a controlled versus an online setting with the ‘Website Evaluation Questionnaire’. Gov Inf Q 2012;29(3):383-393. [ CrossRef ]