Archives of Medical Research

Subject Area and Category

- Medicine (miscellaneous)

Elsevier Inc.

Publication type

01884409, 18735487

Information

How to publish in this journal

The set of journals have been ranked according to their SJR and divided into four equal groups, four quartiles. Q1 (green) comprises the quarter of the journals with the highest values, Q2 (yellow) the second highest values, Q3 (orange) the third highest values and Q4 (red) the lowest values.

The SJR is a size-independent prestige indicator that ranks journals by their 'average prestige per article'. It is based on the idea that 'all citations are not created equal'. SJR is a measure of scientific influence of journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where such citations come from It measures the scientific influence of the average article in a journal, it expresses how central to the global scientific discussion an average article of the journal is.

Evolution of the number of published documents. All types of documents are considered, including citable and non citable documents.

This indicator counts the number of citations received by documents from a journal and divides them by the total number of documents published in that journal. The chart shows the evolution of the average number of times documents published in a journal in the past two, three and four years have been cited in the current year. The two years line is equivalent to journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

Evolution of the total number of citations and journal's self-citations received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. Journal Self-citation is defined as the number of citation from a journal citing article to articles published by the same journal.

Evolution of the number of total citation per document and external citation per document (i.e. journal self-citations removed) received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. External citations are calculated by subtracting the number of self-citations from the total number of citations received by the journal’s documents.

International Collaboration accounts for the articles that have been produced by researchers from several countries. The chart shows the ratio of a journal's documents signed by researchers from more than one country; that is including more than one country address.

Not every article in a journal is considered primary research and therefore "citable", this chart shows the ratio of a journal's articles including substantial research (research articles, conference papers and reviews) in three year windows vs. those documents other than research articles, reviews and conference papers.

Ratio of a journal's items, grouped in three years windows, that have been cited at least once vs. those not cited during the following year.

Evolution of the percentage of female authors.

Evolution of the number of documents cited by public policy documents according to Overton database.

Evoution of the number of documents related to Sustainable Development Goals defined by United Nations. Available from 2018 onwards.

Leave a comment

Name * Required

Email (will not be published) * Required

* Required Cancel

The users of Scimago Journal & Country Rank have the possibility to dialogue through comments linked to a specific journal. The purpose is to have a forum in which general doubts about the processes of publication in the journal, experiences and other issues derived from the publication of papers are resolved. For topics on particular articles, maintain the dialogue through the usual channels with your editor.

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2024. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

- Paper Archives

- Journal Indexing

- Research Conference

- Add Journal

Searching By

- Search More ...

Description

Last modified: 2023-05-05 22:47:29

- No Archives

Advertisement

Society Homepage About Public Health Policy Contact

Author center.

This page has moved to https://esmed.org/author-center/

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

PubMed Central (PMC) Home Page

PubMed Central ® (PMC) is a free full-text archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature at the U.S. National Institutes of Health's National Library of Medicine (NIH/NLM)

Discover a digital archive of scholarly articles, spanning centuries of scientific research.

Learn how to find and read articles of interest to you.

Collections

Browse the PMC Journal List or learn about some of PMC's unique collections.

For Authors

Navigate the PMC submission methods to comply with a funder mandate, expand access, and ensure preservation.

For Publishers

Learn about deposit options for journals and publishers and the PMC selection process.

For Developers

Find tools for bulk download, text mining, and other machine analysis.

9.9 MILLION articles are archived in PMC.

Content provided in part by:, full participation journals.

Journals deposit the complete contents of each issue or volume.

NIH Portfolio Journals

Journals deposit all NIH-funded articles as defined by the NIH Public Access Policy.

Selective Deposit Programs

Publisher deposits a subset of articles from a collection of journals.

March 21, 2024

Preview upcoming improvements to pmc.

We are pleased to announce the availability of a preview of improvements planned for the PMC website. These…

Dec. 15, 2023

Update on pubreader format.

The PubReader format was added to PMC in 2012 to make it easier to read full text articles on tablet, mobile, and oth…

We are pleased to announce the availability of a preview of improvements planned for the PMC website. These improvements will become the default in October 2024.

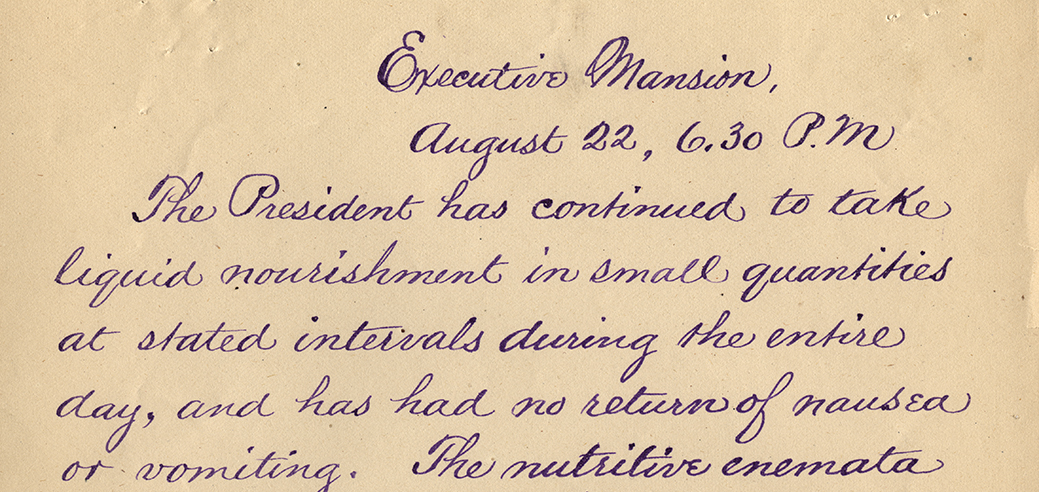

Collections : Archives & Modern Manuscripts

Digitized Collections

Explore fully digitized archives and personal papers collections online such as the Leonidas Berry Papers through NLM Digital Collections.

Profiles in Science

Michael E. DeBakey (1908–2008) was a legendary American surgeon, educator, and medical statesman who transformed cardiovascular surgery.

Introduction

The Archival collections predominantly date from the mid-1900s to the present and with an emphasis on documenting the social and cultural development of post-World War II biomedical science, molecular biology, public health, and health policy... READ MORE

Where to Find...

Archives and modern manuscript collection finding aids.

Online searchable finding aids provide details about the scope and content of NLM personal papers and archives materials. Finding Aids do not represent the entirety of NLM holdings.

Finding aids are comprehensive overviews of unique personal paper and archival resources. Progressively detailed descriptions of a collection’s component parts summarize the overall scope of the content, convey details about the individuals and organizations involved, and list box and folder headings. Special service conditions are noted, including terms under which the collection may be accessed or copied. Links are provided to digitized content, when available.

Accessions and unprocessed collections are generally available for use and often have preliminary boxlists users can consult. Contact us for more information.

A growing number of fully-digitized collections are available online through NLM Digital Collections . Users can expect access to collection materials the same as they would in our reading room.

Archives and Personal Papers Collections

Digitized archival collections

Go to NLM Digital Collections

Student Lecture Notes

Digitized lecture notes from our bound manuscripts holdings

Recipe Books

Digitized recipe and cookery books from our bound manuscripts holdings

NLM Publications and Productions

Publications and videos produced by NLM from NLM's institutional archives

- Bound manuscripts are digitized at the book level; archives and manuscript collections are digitized at the folder or item level according to the contents listings in finding aids.

- Users will find [view online] links alongside folder titles in finding aids.

- Archival collections often contain mixed copyrights. While creators and donors often deed any copyrights they own to the published and unpublished materials in these collections to the public domain, the authors of other third-party materials still retain those copyrights.

- NLM leverages its own fair use rights according to ARL's Code of Best Practices for Fair Use to make these collections publicly available for use in research, teaching, and private study. It is the user's responsibility to research and understand their own fair use rights and any applicable copyright and re-publication rights.

- NLM does not grant permissions to re-publish. Users can find copyright status and re-use information in the Access and Use sections of collection finding aids and in bibliographic records in our online catalogs. NLM will attempt to provide information about copyright holders to the best of our knowledge upon request.

WEB COLLECTIONS

Recognizing that web sites, blogs, social media, and other web content plays an increasingly important role in documenting the scholarly biomedical record and illustrating a diversity of philosophical and cultural perspectives in health and medicine, Archives and Modern Manuscripts has begun selectively collecting representative web content to augment our physical personal papers and organizational archives. NLM also periodically captures and archives large portions of its own web domain, including NLM blogs and social media. In addition to directly accessing archived web content through our Internet Archive Archive It service, archived websites are described in the pertinent collection finding aids.

Browse: Archives and Modern Manuscripts collections NLM Institutional Archives

MORE ABOUT WEB COLLECTING AND ARCHIVING AT NLM

Web collecting and archiving is the process of collecting web sites, social media, and other web content to ensure the information is preserved in an archive for future researchers, historians, and the public. NLM librarians and archivists use Archive-It web crawlers to collect web content guided by the Library’s collection development policies... Read More

PROFILES IN SCIENCE

Profiles in Science presents the lives and work of innovators in science, medicine, and public health through in-depth research, curation, and digitization of archival collection materials. NLM historians and archivists review and select documents from the Library's collections, and collaborating institutions, to bring the public biographical stories and direct access to supporting primary sources. Profiles in Science includes digitized letters, draft manuscripts, photographs, diaries, and more that provide insight into the challenges and successes of scientific discovery and the diversity of paths and perspectives involved.

View Collection

Nlm collections.

FDA Notices of Judgment database

The FDA Notices of Judgment Collection is a digital archive of the published notices judgment for products seized under authority of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

All Modern Manuscript Collections

Modern manuscripts are defined as archival materials dating from the year 1600 and comprise an estimated 20,000 linear feet, including about 250 oral histories. For manuscript collections with finding aids, fully searchable finding aids are available. For more detailed information about manuscript materials without finding aids, consult the NLM on-line catalog LocatorPlus Catalog , or the in-house collection guides.

Oral History Collections

Oral history collections , chiefly from the 1970s to the present, consist of interviews with physicians, scientists, health policy administrators, and health-business executives.

Bound and Folio Manuscripts

Bound and folio manuscripts are chiefly 18th century materials consisting of lecture notes, recipe books, hospital logs, and other discrete items, often with European or eastern U.S. provenance. These manuscripts supplement the Library’s medieval manuscripts and book collections .

Medical Informatics Collections

Medical librarianship and informatics collections include institutional archives, the papers of NLM Directors, including NLM founder John Shaw Billings, and records and oral histories of the Medical Library Association (MLA).

New Accessions and Unprocessed Collections

Unprocessed collections of all types and newer accessions. These materials often have brief information in the NLM on-line catalog and are most likely stored in an offsite location requiring at least 30 days prior notice for delivery. Please consult the HMD Reference Staff for information regarding these collections.

NLM Institutional Archives

NLM Institutional Archives contain records of the National Library of Medicine as well as archives of its website from 2004 to the present.

Archives & Manuscripts | Circulating Now

Last Reviewed: January 9, 2023

Medical Research Archives Latest Publications

Total documents, published by knowledge enterprises journals.

- Latest Documents

- Most Cited Documents

- Contributed Authors

- Related Sources

- Related Keywords

Human Milk: Benefits, Composition and Evolution

Breastfeeding provides all the energy that the child needs in the form of nutrients in the first months of life. The components cover the nutritional needs in all stages, including colostrum and final or mature milk. It must also be taken into account that the composition of milk varies from one woman to another, between both breasts, between feedings and in the different stages in the same mother. It can be said that variation is an active mechanism to perfectly adjust to the nutritional and immunological needs of each child. Components of breast milk can exert beneficial non-nutritional functions. Breast milk also has bioactive factors, which affect biological processes and, therefore, have an impact on health. In the nutrition of premature babies, parenteral nutrition is carried out first, which later becomes enteral through different strategies, such as early minimal enteral nutrition. Despite this, they still present postnatal growth restrictions, which is associated with adverse neurocognitive outcomes. Breast milk achieves multiple benefits in both preterm and term births. Digestion and absorption in the stomach and intestines follow circadian rhythms in mammals, and these rhythms are regulated by rhythmically expressed clock genes in the intestine, as well as by daily food intake.

Biobased Hyperbranched Poly(ester)s of Precise Structure for the Release of Therapeutics

Hyperbrached poly(ester)s derived from naturally-occurring biomonomers may serve as excellent platforms for the sustained-release of therapeutics. Those generated from glycerol are particularly attractive. Traditionally, the difference in reactivity of the hydroxyl groups of glycerol has precluded the formation of well-defined polymers at high monomer conversion without gelation. Using the Martin-Smith model to select appropriate monomer ratios (ratios of functional groups), polymerization may be carried out to high conversion while avoiding gelation and with the assurance of a single type of endgroup. Various agents may be attached via esterification, amide formation or other process. Sustained release of the active agent may be readily achieved by enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis.

Systemic soluble Programmed Death-Ligand 1 levels in sarcoidosis subjects does not vary with disease progression

Interaction of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptor and its ligand 1 (PD-L1) is well studied in the field of fibrotic lung diseases, supporting its use as a biomarker of progression of interstitial lung disease. Anti PD-L1 therapy has shown effectiveness in improvement of many malignancies and murine models of autoimmune fibrotic lung diseases. Higher PD-1 expression on T cells and PD-L1 expression on human lung fibroblasts are known to contribute towards severity in sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), respectively. The focus of this investigation was to determine if soluble form of PD-L1 (sPD-L1) serves as predictive biomarker of disease severity in interstitial lung disease (ILD), such as scleroderma, sarcoidosis and IPF. Comparison of local environments, such as bronchoalveolar lavage, revealed significantly higher sPD-L1 levels compared to systemic environments, such as peripheral blood (p=0.001, paired two-tailed Student’s t test). Investigation of serum samples of healthy control, IPF, scleroderma and sarcoidosis patients reveal significantly higher levels in sarcoidosis and IPF patients, compared to patients with scleroderma (p=0.001; p=0.02, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s respectively). Comparison of serum levels between sarcoidosis patients and healthy controls revealed no significant differences (p=0.09, unpaired two-tailed t test). In addition, comparison of physiologic parameters, such as percent predicated Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) and sPD-L1 levels in sarcoidosis and IPF patients revealed no correlation. These observations suggest that sPD-L1 will not serve as a biomarker of sarcoidosis disease severity. Additional investigation of sPD-L1 in local environments is warranted.

Ethics or Bioethics for the Medical Profession?

The events that have occurred as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have brought to the fore the figure of the doctor, as a main actor, in this complex and uncertain scenario. Many of the medical actions carried out have required strength, reflection, wisdom and prudence, all of them essential virtues according to the classical philosophical tradition, and that the ETHOS of the medical profession and the doctor translate, with this it is necessary to emphasize that it is the traditional medical ethics, the basis of this undeniable commitment to humanity, and that Bioethics, born 60 years ago, has been invested with an unthinkable condition, by its creator VR Potter, who proposed that the main objective should be scientific development -Technical but with ecological responsibility, beyond its supposed guiding function of current medicine. Which are the motivations for choosing the School of Medicine? What does it mean to be a good professional? How to respond to an increasingly demanding society? In light of the development of new technologies and communication systems, which today are universally accessible. It seems that the answer to these questions lies in a higher education based on ancestral ethical principles, which have been professed by generations of doctors, in traditional clinical practice and in practicing general medicine to achieve the specific medical training process, thus achieving efficiently meet the primary health demands of society. Therefore, Bioethics must be understood as an incipient discipline whose objective is to warn about the care of ecosystems, necessary for the survival of the human being, different from medical ethics.

Coevolution study of tau and a-synuclein suggests a connection between their normal interaction in neurons and the Parkinson's disease-associated mutation A53T

Alpha-synuclein lies at the center of Parkinson’s disease etiology, and polymorphisms in the gene for the microtubule-associated protein tau are risk factors for getting the disease. Tau and a-synuclein interact in vitro, and a-synuclein can also compete with tau binding to microtubules. To test whether these interactions might be part of their natural biological functions, a correlated mutation analysis was performed between tau and a-synuclein, looking for evidence of coevolution. For comparison, analyses were also performed between tau and b- and g-synuclein. In addition, analyses were performed between tau and the synuclein proteins and the neuronal tubulin proteins. Potential correlated mutations were detected between tau and a-synuclein, one involving an a-synuclein residue known to interact with tau in vitro, Asn122, and others involving the Parkinson’s disease-associated mutation A53T. No significant correlated mutations were seen between tau and b- and g-synuclein. Tau showed potential correlated mutations with the neuron-specific bIII-tubulin protein, encoded by the TUBB3 gene. No convincing correlated mutations were seen between the synuclein and tubulin proteins, with the possible exception of b-synuclein with bIVa-tubulin, encoded by the TUBB4A gene. While the correlated mutations between tau and a-synuclein suggest the two proteins have coevolved, additional study will be needed to confirm that their interaction is part of their normal biological function in cells.

The belated implementation of a long-awaited health system in Cyprus and the role of interest groups

It is really a paradox that 60 years were required to establish a modern health system in Cyprus, despite the expressed positive attitude οf all political parties and most governments. This article investigates the planning and implementation of the National Health System (NHS) and its delay determinants, by employing qualitative research of published sources, audio material and 33 interviews with elite key informants. A major anti-reform alliance, consisting of private doctors, private hospitals and health insurance companies was identified, further supported by doctors of the “old” public system, whose benefits were threatened. Delay contributions additionally arose from media and patient groups, whilst the pharmaceutical sector imposed insignificant influence. Τhe prevailing political, economic and social environment, along with aspects of the proposed reform, fueled this anti-reform movement. However, climate in favour of the NHS implementation gradually developed, attributed to the power balance shift supportingthe Minister of Health and the government, mobilization of important actors/stakeholders, including the Federation of Patients' Organizations of Cyprus and the Media, and significant decrease in the influence of reform-resistant groups. The new dynamics created a supportive environment leading to the NHS launch on June 1st, 2019; thus Cyprus has ceased to be the last state of the European Union (EU) without a universal health coverage system. The process of introducing this new system in Cyprus is a prime example of resource and power redistribution amongst different interest groups and of the catalysts required to exit the orbit of an extremely “path-dependent” system, potentially inspiring future reformers.

History of Trypanosomosis in the One-Humped Camel and Development of its Treatment and Cure, with Special Reference to Sudan

Sudan has one of the largest populations of domestic animals in Africa. One-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius) numbers were estimated at 4.5 million in 2009. Once used extensively for military transport they are still used in the transport role by spatially mobile pastoralist households and are a major source of milk and meat for these people. Trypanosomosis, due to Trypanosoma evansi, generally known as ‘surra’ but as ‘gufar’ in Sudan was first identified in camels in the country in 1902 and is the main cause of disease although T. vivax infections have recently been discovered in parts of Sudan. This protozoan disease is the most important health problem in camels, causing high morbidity and huge production losses. The causal organism, unlike most other trypanosomes, is not transmitted cyclically with tsetse (genus Glossina) flies as the vector but mechanically by biting flies mainly family Tabanidae but also by others of the Muscidae. Identification of the parasite in camel blood was initially by simple microscopic techniques but biotechnology and molecular methods now enable infection to be diagnosed at an earlier stage and with more accuracy. Prophylactic and curative treatments of trypanosomosis are notoriously complicated and uncertain with the situation in camels being exacerbated because of its peculiar physiology. Many trypanocides have been developed over time but the parasite often develops resistance to these drugs. Some drugs are successful, for some time, as both prophylactics and cures but are often accompanied by undesirable side effects. Other drugs used on conventional domestic stock are ineffective in camels or have lower efficacy. Research on diagnosis and treatment of trypanosomosis is continuing but the disease continues to cause production losses to the detriment of national and household incomes and food security.

Time-course of adaptations for electroretinography and pupillography

Cones are primarily involved in photopic vision and light adaptation. Rods are responsible for scotopic vision and dark adaptation. The typical time-courses of light and dark adaptations have been known for century. However, information regarding the minimal adaptation time for electroretinography (ERG) and pupillography would be helpful for practical applications and clinical efficiency. Therefore, we investigated the relationship between adaptation time and the parameters of ERG and pupillography. Forty-six eyes of 23 healthy women (mean age, 21.7 years) were enrolled. ERG and pupillography were tested for right and left eyes, respectively. ERG with a skin electrode was used to determine amplitude (µV) and implicit time (msec) by the records of rod-, flash-, cone-, and flicker-responses with white light (0.01–30 cd·s/m2). Infrared pupillography was used to record the pupillary response to 1-sec stimulation of red light (100 cd/m2). Cone- and flicker- (rod-, flash-, and pupil) responses were recorded after light (dark) adaptation at 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 min. Amplitude was significantly different between 1 min and ≥5 or ≥10 min after adaptation in b-wave of cone- or rod-response, respectively. Implicit time differed significantly between 1 min and ≥5 min after adaptation with b-wave of cone- and rod-response. There were significant differences between 1 min and ≥10 or ≥5 min after dark adaptation in parameter of minimum pupil diameter or constriction rate, respectively. Consequently, light-adapted ERGs can be recorded, even in 5 min of light adaptation time without special light condition, whereas dark-adapted ERGs and pupillary response results can be obtained in 10 min or longer of dark adaptation time in complete darkness.

A Comparison of Neuropathy Quality of Life Tools: Norfolk QOL-DN, PN-QOL-97, and NeuroQOL-28

Aims To explore the effectiveness of the Norfolk QOL-DN (QOL-DN), PN-QOL-97, and NeuroQOL-28 as tools for early detection of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in overweight, obese, and inactive (OOI), prediabetes (PD), and type 2 diabetes (T2D) individuals. Methods Thirty-four adults were divided by A1C [(10 OOI, 13 PD, and 11 T2D] and the sural nerves were tested bilaterally via NC-Stat DPN Check, conducting a sural nerve conduction study (NCS). Participants were individually timed, filling out questionnaires (QOL-DN, NeuroQOL-28, and PN-QOL-97) at a self-selected pace. Data were analyzed and compared to NCS findings to determine the best instrument for early neuropathy detection, usability in screening settings, and application for individuals with OOI, PD, and T2D. Results Abnormal NCS results were obtained from 27 individuals, of which 25 were bilateral and symmetrical. Confirmed DSPN criteria were met for 24, and 1 case met criteria for subclinical neuropathy. Normal NCS findings, reported symptoms, and reduced bilateral sensation were found in 7 cases. The QOL-DN and NeuroQOL-28 significantly predict neuropathy criteria in OOI, PD, and T2D subjects. Analyses revealed the QOL-DN as the quickest for completion (M=5.17; SD=1.83), followed by the NeuroQOL-28 (M=5.58; SD=3.56), and the PN-QOL-97 (M=13.23; SD=3.606). Conclusions The QOL-DN and NeuroQOL-28 are valid early screening measures for DPN detection. Time completion studies revealed that the QOL-DN and NeuroQOL-28 may be used as excellent short screening measures, completed in approximately 6 minutes or less, with reasonable scoring for both. The NeuroQOL-28 is a better fit for immediate feedback, time constraints, or limited staff. Future investigations should evaluate these tools for detection in DPN-prone individuals and in subclinical populations screenings.

A Pilot Study of At-Home Virtual Reality for Chronic Pain Patients

Chronic pain disorders are a common and expensive health problem worldwide. Available treatments for these disorders have been decreasing and new treatments are needed. Virtual reality (VR) has been used for acute and procedural pain for years but systems are only now becoming available for use with chronic pain. In this study patients with a chronic pain disorder were given the option of using either take-home virtual reality equipment for one month or take-home biofeedback equipment for one month. In the VR condition patients were oriented to the “PainCare” app but could access any free content from the internet as well. Qualitative data was gathered on 23 VR patients and 12 biofeedback patients. Pre-post measures of depression, catastrophizing and function were obtained from 17 VR patients and 8 biofeedback patients. Data found that there was a statistically significant decrease in depression and catastrophizing in the VR group but no such decrease was found in the biofeedback group. No significant increase in function was found in either group though the VR group trended in that direction. One hundred percent (100%) of the patients who tried VR reported that they thought it had helped them overall at least a little. Patient ratings of the VR equipment were more favorable than the biofeedback equipment. This non-randomized small sample study suggests that at-home VR use can be used successfully with patients to decrease the important treatment variables of depression and catastrophizing, and perhaps become a significant contribution to the treatment of chronic pain disorders.

Export Citation Format

Share document.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Trending Articles

- Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators. Lancet. 2024. PMID: 38762324

- An age-progressive platelet differentiation path from hematopoietic stem cells causes exacerbated thrombosis. Poscablo DM, et al. Cell. 2024. PMID: 38749423

- Burden of disease scenarios for 204 countries and territories, 2022-2050: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. GBD 2021 Forecasting Collaborators. Lancet. 2024. PMID: 38762325

- ARID1A suppresses R-loop-mediated STING-type I interferon pathway activation of anti-tumor immunity. Maxwell MB, et al. Cell. 2024. PMID: 38754421

- Andexanet for Factor Xa Inhibitor-Associated Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Connolly SJ, et al. N Engl J Med. 2024. PMID: 38749032 Clinical Trial.

Latest Literature

- Am J Clin Nutr (1)

- Am J Surg Pathol (2)

- Arch Phys Med Rehabil (2)

- Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2)

- Gastroenterology (2)

- J Biol Chem (6)

- Nat Commun (1)

- Pediatrics (3)

- World J Gastroenterol (13)

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Abstracted and indexed

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 20 May 2024

Medical history predicts phenome-wide disease onset and enables the rapid response to emerging health threats

- Jakob Steinfeldt ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1387-2054 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 na1 ,

- Benjamin Wild ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7492-8448 6 na1 ,

- Thore Buergel 5 , 6 na1 ,

- Maik Pietzner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3437-9963 3 , 7 , 8 ,

- Julius Upmeier zu Belzen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0966-4458 6 ,

- Andre Vauvelle 9 ,

- Stefan Hegselmann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2145-3258 10 , 11 ,

- Spiros Denaxas 9 , 12 , 13 , 14 ,

- Harry Hemingway ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2279-0624 9 , 13 , 14 ,

- Claudia Langenberg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5017-7344 3 , 7 , 8 ,

- Ulf Landmesser ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0214-3203 1 , 2 , 4 , 15 , 16 na2 ,

- John Deanfield 5 na2 &

- Roland Eils ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0034-4036 6 , 17 na2

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 4257 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Disease prevention

- Epidemiology

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed a global deficiency of systematic, data-driven guidance to identify high-risk individuals. Here, we illustrate the utility of routinely recorded medical history to predict the risk for 1883 diseases across clinical specialties and support the rapid response to emerging health threats such as COVID-19. We developed a neural network to learn from health records of 502,460 UK Biobank. Importantly, we observed discriminative improvements over basic demographic predictors for 1774 (94.3%) endpoints. After transferring the unmodified risk models to the All of US cohort, we replicated these improvements for 1347 (89.8%) of 1500 investigated endpoints, demonstrating generalizability across healthcare systems and historically underrepresented groups. Ultimately, we showed how this approach could have been used to identify individuals vulnerable to severe COVID-19. Our study demonstrates the potential of medical history to support guidance for emerging pandemics by systematically estimating risk for thousands of diseases at once at minimal cost.

Introduction

The early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic exposed a global deficiency in delivering systematic, data-driven guidance for individual patients and healthcare providers with critical implications for pandemic preparedness. The assessment of an individual’s risk for future disease is central to guiding preventive interventions, early detection of disease, and the initiation of treatments. However, bespoke risk scores are only available for a subset of common diseases 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , leaving healthcare providers and individuals with little to no guidance on most relevant diseases. Even for diseases with established risk scores, little consensus exists on which score to use and associated physical or laboratory measurements to obtain, leading to highly fragmented practice in routine care 5 . Importantly, in the early phases of emerging pandemics such as COVID-19, it is necessary to allocate sparse resources, but risk scores to identify vulnerable subpopulations are not available due to the lack of available data.

At the same time, most medical decisions on diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of diseases are fundamentally based on an individual’s medical history 6 . With the widespread digitalization, this information is routinely collected by healthcare providers, insurance, and governmental organizations at a population scale in the form of electronic health records 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 . These readily accessible records, which include diseases, medications, and procedures, are potentially informative about future risk trajectories, but their potential to improve medical decision-making is limited by the human ability to process and understand vast amounts of data 13 .

To date, routine health records have been used to guide clinical decision-making with etiological 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , diagnostic 18 , 19 , and prognostic research 15 , 16 , 20 , 21 , 22 . Existing efforts often extract and leverage known clinical predictors with new methodologies 19 , augment them with additionally extracted data modalities such as clinical notes 23 , or aim to identify novel predictors among the recorded concepts 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . Prior work on the prediction of disease onset has mainly focused on single diseases, including dementia 15 , 24 , cardiovascular conditions 23 , 25 such as heart failure 26 and atrial fibrillation 27 , 28 . In contrast, phenome-wide association studies (PheWAS) quantifying the associations of genetic variants with comprehensive phenotypic traits are emerging in genetic epidemiology 29 , 30 . While approaches have been developed for high-throughput phenotyping 31 , 32 and to extract information from longitudinal health records 33 , 34 , no studies have investigated the predictive potential and potential utility over the entire human phenome. Consequently, the predictive information in routinely collected health records and its potential to systematically guide medical decision-making is largely unexplored.

Here, we examined the predictive potential of an individual’s entire medical history and propose a systematic approach for phenome-wide risk stratification. We developed, trained, and validated a neural network in the UK Biobank cohort 35 to estimate disease risk from routinely collected health records. Unlike alternative methods, such as linear models or survival trees, which require separate models for each disease, our approach employs a multi-layer perceptron that predicts multiple endpoints concurrently, resulting in a significantly simplified model architecture. These endpoints include preventable diseases (e.g., coronary heart disease), diseases that are not currently preventable, but the early diagnosis has been shown to substantially slow down the progression and development of complications (e.g., heart failure), and outcomes, which are currently neither entirely preventable nor treatable (e.g., death). They also include both diseases with risk prediction models recommended in guidelines and used in practice (e.g., cardiovascular diseases or breast cancer) as well as diseases without current risk prediction models (e.g., psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis).

We evaluated our approach by integrating the endpoint-specific risk states estimated by the neural network in Cox Proportional Hazard models 36 , investigating the phenome-wide predictive potential over basic demographic predictors, selected comorbidities, and established modifiable risk factors, and illustrating how phenome-wide risk stratification could benefit individuals by providing risk estimates, facilitating early disease diagnosis, and guiding preventive interventions. Furthermore, by externally validating in the All Of Us cohort 37 , we show that our models can generalize across healthcare systems and populations, including communities historically underrepresented in biomedical research.

Finally, we assessed the potential of our approach to aid risk stratification for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and to respond to emerging health threats at the example of COVID-19. We then show that the risk states of pneumonia, sepsis & all-cause death can be used to calculate a combined severity risk score using primary and secondary care records available before the global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our results demonstrate the currently unused potential of routine health records to guide medical practice by providing comprehensive phenome-wide risk estimates.

Characteristics of the study population and integration of routine health records

This study is based on the UK Biobank cohort 35 , 38 , a longitudinal population cohort of 502,460 relatively healthy individuals of primarily British descent, with a median age of 58 (IQR 50, 63) years, 54.4% biological females, 11% current smokers, and a median BMI of 26.7 (IQR 24.1, 29.9) at recruitment (Table 1 for detailed information). Individuals recruited between 2006 and 2010 were followed for a median of 12.6 years, resulting in ~6.2 M overall person-years on 1883 phenome-wide endpoints 39 with ≥ 100 incident events (>0.02% of individuals having the event in the observation time). We externally validated our findings in individuals from the All of Us cohort, a longitudinal cohort of 229,830 individuals with linked health records recruited from all over the United States. Individuals in the All of Us cohort are of diverse descent, with 46% of reportedly non-white ethnicity and 78% of groups historically underrepresented in biomedical research 37 , 40 , and have a median age of 54 (IQR 38, 65) years with 61.1% biological females (see Table 1 for detailed information). Individuals were recruited from 2019 on and followed for a median of 3.5 years, resulting in ~787,300 person-years on 1568 endpoints.

Central to this study is the prior medical history, defined as the entirety of routine health records before recruitment. Before further analysis, we mapped all health records to the OMOP vocabulary. While most records originate from primary care and, to a lesser extent, secondary care (Suppl. Figure 1a ), the predominant record domains are drugs and observations, followed by conditions, procedures, and devices (Supplementary Fig. 1b ). Interestingly, while rare medical concepts (with a record in <1% of individuals in the study population) are not commonly included in prediction models 21 , they are often associated with high incident event rates (exemplified by the mortality rate in Supplementary Fig. 1c ) compared to common concepts (a record present in >= 1% of the study population). For example, the concept code for “portal hypertension” (OMOP 34742003) is only recorded in 0.04% (203) of individuals at recruitment, but 48.7% (99 individuals) will die over the course of the observation period. Importantly, there are many distinct rare concepts, and thus 91.7% of individuals have at least one rare record before recruitment, compared with 92.5% for common records. In addition, 60.7% of individuals have ≥ 10 rare records compared with 78.4% for common records, and individuals have only slightly fewer rare than common records (Supplementary Fig. 1d ).

After excluding very rare concepts (<0.01%, less than 50 individuals with the record in this study), we integrated the remaining 15,595 unique concepts (Supplementary Data 2 ) with a multi-task multi-layer perceptron (with 88.4 M parameters) to predict the phenome-wide onset of 1883 endpoints (Supplementary Data 1 ) simultaneously (Fig. 1a ). For comparison, we also include additional comparisons with a linear baseline (with 29.4 M parameters, Supplementary Fig. 2 ), demonstrating superior performance at a minimal increase of complexity.

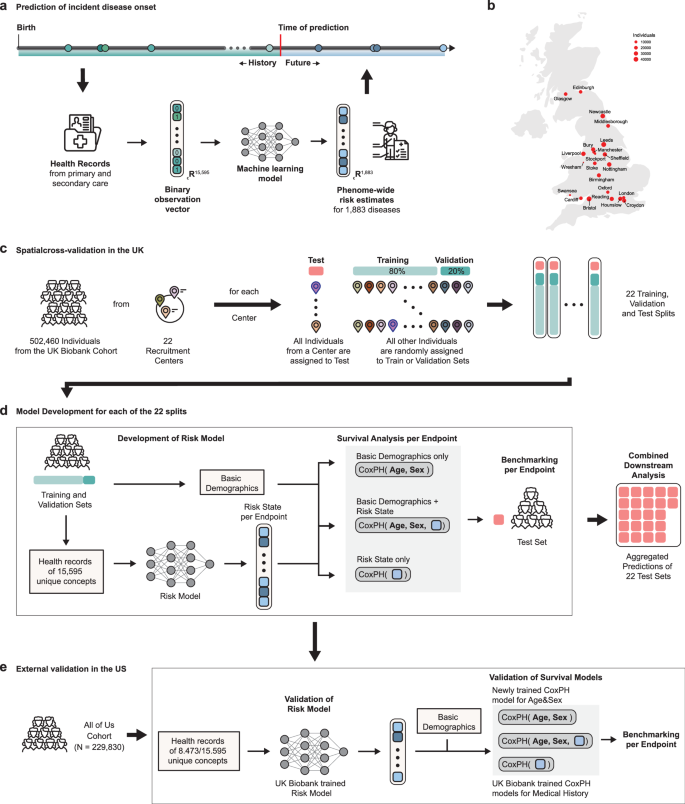

a The medical history captures encounters with primary and secondary care, including diagnoses, medications, and procedures (ideally) from birth. Here we train a multi-layer perceptron on data before recruitment to predict phenome-wide incident disease onset for 1883 endpoints. b Location and size of the 22 assessment centers of the UK Biobank cohort across England, Wales, and Scotland. c To learn risk states from individual medical histories, the UK Biobank population was partitioned by their respective assessment center at recruitment. d For each of the 22 partitions, the Risk Model was trained to predict phenome-wide incident disease onset for 1883 endpoints. Subsequently, for each endpoint, Cox proportional hazard (CPH) models were developed on the risk states in combination with sets of commonly available predictors to model disease risk. Predictions of the CPH model on the test set were aggregated for downstream analysis. e External validation in the All of US cohort. After mapping to the OMOP vocabulary, we transferred the trained risk model to the All of US cohort and calculated the risk state for all endpoints. To validate these risk states, we compared the unchanged CPH models developed in the UK Biobank with refitted CPH models for age and sex. Source data are provided. The Icons are made by Freepik from www.flaticon.com .

To ensure that our findings are generalizable and transferable, we spatially validate our models in 22 recruitment centers (Fig. 1b ) across England, Wales, and Scotland. We developed 22 models, each trained on individuals from 21 recruitment centers at recruitment, randomly split into training and validation sets (Fig. 1c ). We subsequently tested the models on individuals from the additional recruitment center unseen for model development for internal spatial validation. After checkpoint selection on the validation data sets and obtaining the selected models’ final predictions on the individual test sets, the test set predictions were aggregated for downstream analysis (Fig. 1d ). Subsequently, disease-specific exclusions of prior events and sex-specificity were respected in all downstream analyses. After development, the models were externally validated in the All of Us cohort 37 .

Routine health records stratify phenome-wide disease onset

Central to the utility of any predictor is its potential to stratify risk. The better the stratification of low and high-risk individuals, the more effective targeted interventions and disease diagnoses are.

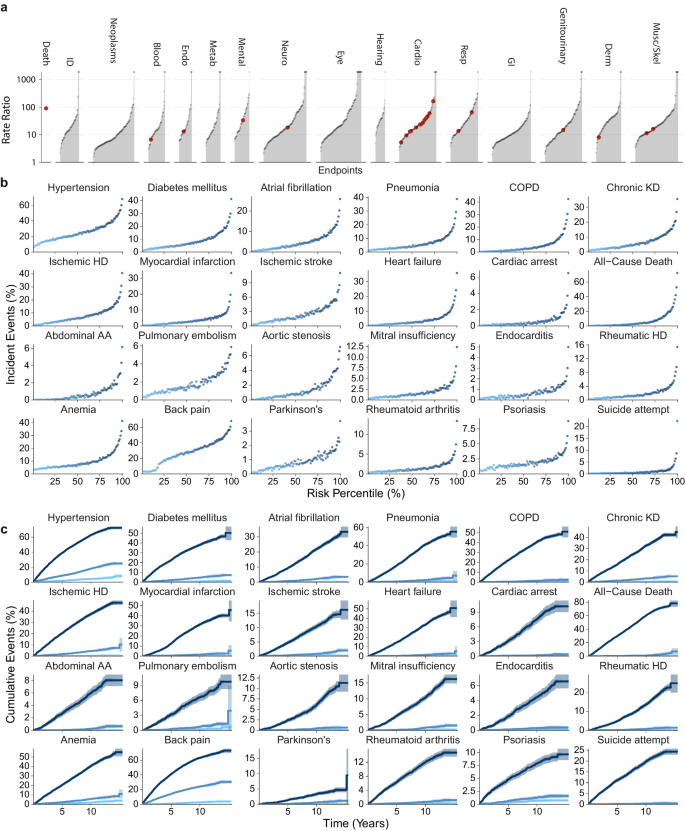

To investigate whether health records can be used to identify high-risk individuals, we assessed the relationship between the risk states estimated by the neural network for each endpoint and the risk of future disease (Fig. 2 ). For illustration, we first aggregated the incident events over the percentiles of the risk states for each endpoint and subsequently calculated ratios between the top and bottom 10% of risk states over the entire phenome (Fig. 2a ). We found that fewer than 10% of the individuals had an incident hypertension diagnosis in the observation window if they were estimated to be in the bottom risk percentile of the medical history, compared to more than 60% if they were estimated to be in the top risk percentile. Subsequently, the incident event ratio between the top and bottom deciles was ~5.23. Importantly, we found differences in the event rates, reflecting a stratification of high and low-risk individuals for almost all endpoints covering a broad range of disease categories and etiologies: For 1341 of 1883 endpoints (71.2%), we observed >10-times as many events for individuals in the top 10% of the predicted risk states compared to the bottom 10%. For instance, these endpoints included rheumatoid arthritis (Ratio ~11.3), ischemic heart disease (Ratio ~23.5), or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Ratio ~65.4). For 230 (12.2%) of the 1883 conditions, including abdominal aortic aneurysm (Ratio ~163.4), more than 100 times the number of individuals in the top 10% of predicted risk states had incident events compared to the bottom 10%. For 542 (28.8%) endpoints, the separation between high and low-risk individuals was smaller (Ratio <10), which included hypertension (Ratio ~5.2) and anemia (Ratio ~6.7), often diagnosed earlier in life or precursors for future comorbidities. Notably, the ratios were >1 for all but one of the 1883 investigated endpoints, even though all models were developed in spatially segregated assessment centers. To illustrate how high-risk individuals differ from the moderate cases, we also provide additional ratios comparing the top 10% to individuals in the median 20% of the population. The complete list of all endpoints and corresponding statistics can be found in Supplementary Data 4 .

a Ratio of incident events in the Top 10% compared with the Bottom 10% of the estimated risk states. Event rates in the Top 10% are higher than in the Bottom 10% for all but one of the 1883 investigated endpoints. Red dots indicate 24 selected endpoints detailed in Fig. 2b. To illustrate, 1198 (2.39%) individuals in the top risk decile for cardiac arrest experienced an event compared with only 30 (0.06%) in the bottom decile, with a risk ratio of 39.93. b Incident event rates for each medical history risk percentile (if medical history was available) for a selection of 24 endpoints. c Cumulative event rates with 95% confidence intervals for the Top 1%, median, and Bottom 1% of risk percentiles in b ) over 15ys. Statistical measures were derived from 502.460 individuals. Individuals with prevalent diseases were excluded from the endpoints-specific analysis. Source data are provided.

In addition to the phenome-wide analysis of 1883 endpoints, we also provide detailed associations between the risk percentiles and incident event ratios (Fig. 2b ), as well as cumulative event rates for up to 15 years (Fig. 2c ) of follow-up for the top, median, and bottom percentiles for a subset of 24 selected endpoints. This set was selected to comprise actionable endpoints and common diseases with significant societal burdens, specific cardiovascular conditions with pharmacological and surgical interventions, as well as endpoints without established tools to stratify risk to date. To exemplify the potential of our approach, among individuals in the top risk decile for heart failure, 8018 (16.06%) experienced an event, in contrast to 178 (0.35%) individuals in the bottom decile, resulting in a risk ratio of 46.35 (Fig. 2a, b , Supplementary Data 4 ). Consequently, those at high risk of heart failure could be prioritized for echocardiographic screening and, if necessary, prescribed effective guideline-directed medical therapy. Similarly, individuals with a high risk of developing COPD—where the top 10% face over 65 times the risk compared to the bottom 10%—may be considered for spirometry, an approach already established in the CAPTURE trial 41 . If confirmed, they could benefit from interventions such as long-acting bronchodilators. As a third example, a high-risk estimate for less common diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (risk ratio ~8.3), could further support referring individuals to a specialist and potentially shorten the often extensive patient journey before a final diagnosis is reached.

In summary, the disease-specific states stratify the risk of onset for all 1883 investigated endpoints across clinical specialties. This indicates that routine health records provide a large and widely unused potential for the systematic risk estimation of disease onset in the general population.

Discriminative performance indicates potential utility

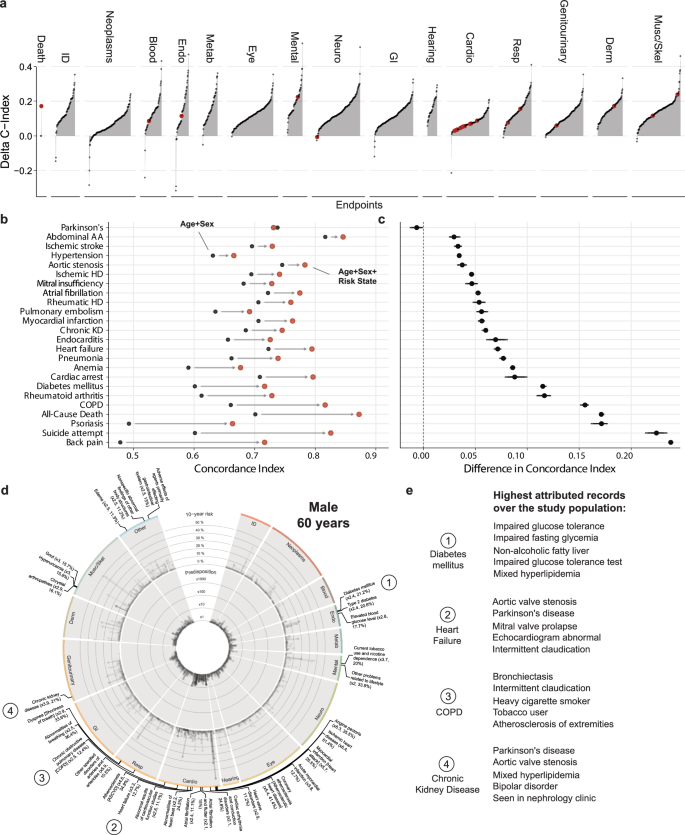

While routine health records can stratify incident event rates, this does not prove utility. To test whether the risk state derived from the routine health records could provide utility and information beyond ubiquitously available predictors, we investigated the predictive information over age and biological sex, selected comorbidities from the Charlson Comorbidity Index 42 , and established modifiable risk factors from the AHA ASCVD pooled cohort equation 3 . We modeled the risk of disease onset using Cox Proportional-Hazards (CPH) models for all 1883 endpoints, which allowed us to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (denoted as HR in Supplementary Data 6 ) and 10-year discriminative improvements (indicated as Delta C-index in Fig. 3a ).

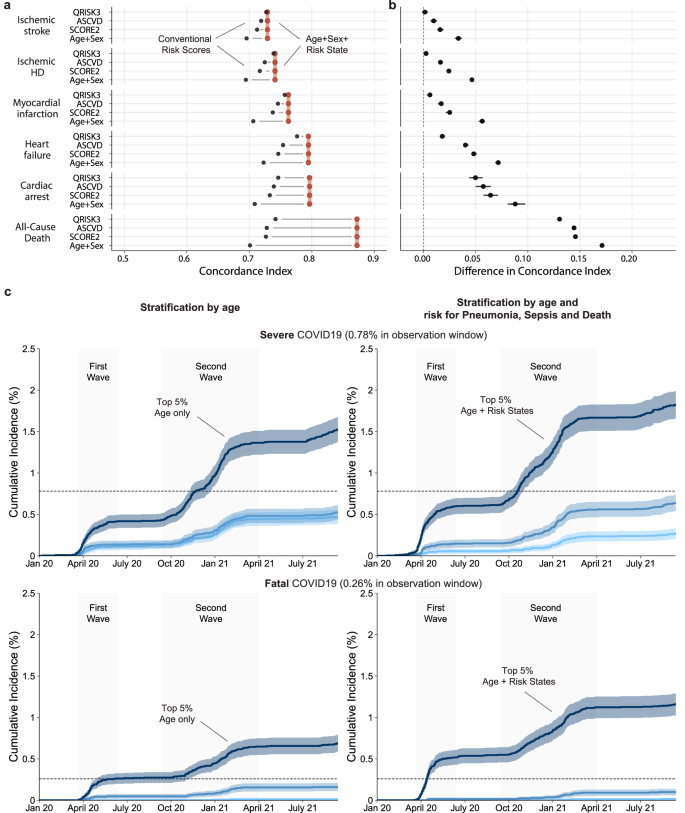

a Differences in discriminatory performance quantified by the C-Index between CPH models trained on Age+Sex and Age+Sex+MedicalHistory for all 1883 endpoints. We found significant improvements over the baseline model (Age+Sex, age, and biological sex only) for 1774 (94.2%) of the 1883 investigated endpoints. Red dots indicate selected endpoints in Fig. 3b. b Absolute discriminatory performance in terms of C-Index comparing the baseline (Age+Sex, black point) with the added routine health records risk state (Age+Sex+RiskState, red point) for a selection of 24 endpoints. c The direct C-index differences for the same models. Dots indicate medians and whiskers extend to the Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval for a distribution bootstrapped over 100 iterations. d Example of individual predicted phenome-wide risk profile. Predisposition (10-year risk estimated by Age+Sex+RiskState compared to risk estimated by Age+Sex alone) is displayed in the inner circle, and absolute 10-year risk estimated by Age+Sex+RiskState can be found in the outer circle. Labels indicate endpoints with a high individual predisposition (>2 times higher than the Age+Sex-based reference estimate) and absolute 10-year risk > 10%. e Top 5 highest attributed records for selected endpoints. Statistical measures were derived from 502.460 individuals. Source data are provided.

We found significant improvements over the baseline model (age and biological sex only) for 1774 (94.2%) of the 1883 investigated endpoints (Fig. 3 , Supplementary Data 5 ). For many of these endpoints, the discriminative improvements were considerable (Delta C-Index Q25%: 0.094, Q50: 0.116, Q75: 0.141). We found significant improvements for 23 of the highlighted subset of 24 endpoints (indicated in Fig. 2a ), with the largest increases for the prediction of back pain (Delta C-Index: +0.238 (CI 0.236, 0.241)), suicide attempts (Delta C-Index: +0.224 (CI 0.213, 0.235)), psoriasis (Delta C-Index: +0.171 (CI 0.161, 0.178)), all-cause mortality (Delta C-Index: +0.171 (0.169, 0.174)) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Delta C-Index: +0.156 (0.151, 0.159)). In contrast, we did not find significant improvements in the prediction of 86 (4.6%) of the 1883 endpoints, including, e.g., Parkinson’s disease (Delta C-Index: −0.006 (CI −0.013, 0)) or even deteriorations in the prediction of 23 (1.2%) of the endpoints, including neoplasm like cervical cancer (Delta C-Index: −0.025 (−0.059, −0.004)) and gastrointestinal diseases as chronic hepatitis (Delta C-Index: −0.032 (−0.064, −0.007)).

We also present a comparison between our approach and the Charlson Comorbidity Index’s 42 predictive performance, both of which can be automated. Additionally, we compare our method to the well-established ASCVD predictors, which are widely accessible but require an additional blood draw. Notably, incorporating the comorbidities from the Charlson Comorbidity Index enhances the discriminative capacity beyond age and sex; however, adding medical history proves to be significantly more effective in improving performance (Supplementary Fig. 3 , Supplementary Data 5 ). Likewise, while supplementing ASCVD predictors to age and sex augments the performance for most endpoints, it remains inferior to the combination of age, sex, and medical history alone. Incorporating the medical history alongside the comorbidities or ASCVD predictors further improves the predictive performance for the vast majority of endpoints (AgeSex+Comorbidities augmented by the MedicalHistory: +1726/1883 (91.7%), ASCVD+MedicalHistory: +1727/1883 (91.7%), demonstrating complementary nature of these information sources.

For illustration, we also present individual phenome-wide risk profiles (Fig. 3c , Supplementary Fig. 4a +b and 5a+b). The risk profiles varied substantially in the predispositions relative to the age and sex reference (the inner circle, see methods for details) and the absolute 10-year risk estimates (the outer circle). The first individual (Fig. 3c ), a 60-year-old man, is predicted to be at a particularly high 10-year risk of metabolic, cardiovascular, respiratory, and genitourinary conditions, including diabetes mellitus (19.4%), heart failure (22%), COPD (14.9%), and chronic kidney disease (16.8%). Increased risk of neoplastic, dermatological, and musculoskeletal conditions was not predicted by the prior health records of this individual. In contrast, another individual, a 48-year-old woman (Supplementary Fig. 5b ), is not estimated at increased cardiovascular risk but conversely to have almost 10x the risk for suicide ideation and attempt or self-harm compared to the reference group.

Importantly, the model performance is robust to the removal of recent information, indicating that the model effectively incorporates both the individuals’ long-term medical history and recent interactions with the healthcare system in order to predict future disease onset (Supplementary Fig. 6 ). We provide Shapley attributions 43 for the most important records (Fig. 3d , Suppl. Figure 4c , Suppl. Figure 5c ) and all records for the 24 highlighted endpoints (Supplementary Data 9 ) in the study population, enhancing the interpretability of our findings.

These findings indicate that health records contain substantial predictive information over established predictors for the majority of disease endpoints from across clinical specialties.

Predictive models can generalize across healthcare systems and populations

While our findings indicate potential utility in the UK Biobank, health records vary substantially across healthcare systems and over time due to differences in medical and coding practices (“distribution shift”) and underlying differences in the populations. Thus, predictive models can fail to learn robust and generalizable information 44 , 45 , 46 .

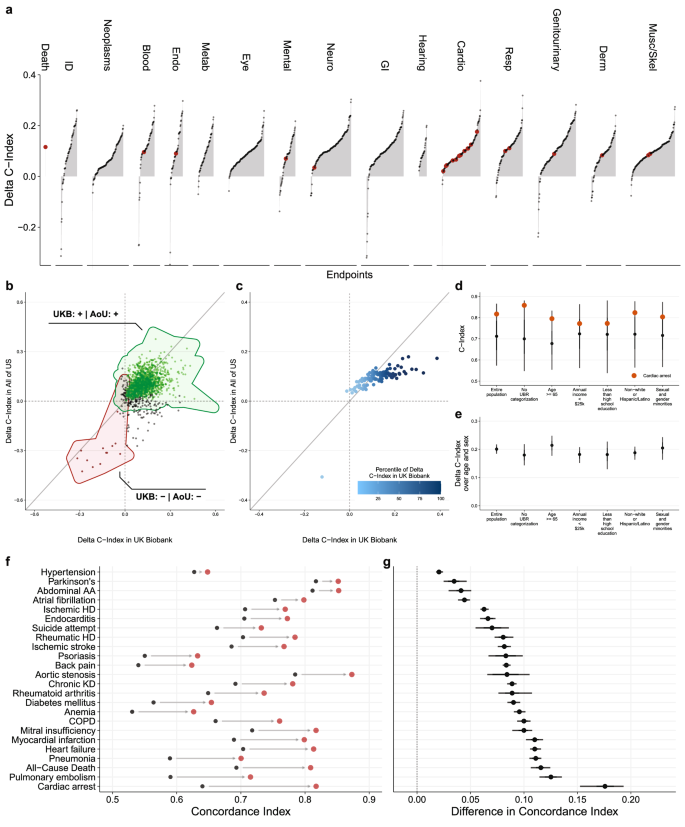

To better understand the generalisability across different healthcare systems, we predicted risk states and absolute risk estimates for all individuals in the All of Us cohort with linked medical records ( N = 229,830; see Table 1 ). Importantly, we found significant improvements over the baseline model (age and biological sex only) for 1347 (85.9%) of the 1568 investigated endpoints with at least 100 incident events (Fig. 4a , Supplementary Data 8 ), replicating 1347/1500 (89.8%) of all significant improvements in the UK Biobank (Fig. 4b , Supplementary Data 8 ). Generally, larger improvements in the UK Biobank were replicated in the All of Us cohort. It’s noteworthy that smaller improvements in the UK Biobank often corresponded to proportionately larger improvements in All of Us, while larger improvements in the UK Biobank were attenuated in All of Us (Fig. 4c ).

a External validation of the differences in discriminatory performance quantified by the C-Index between CPH models trained on age and biological sex and age, biological sex, and the risk state for 1.568 endpoints in the All of Us cohort. We find significant improvements over the baseline model (age and biological sex only) for 1.347 (85.9%) of the 1.568 investigated endpoints. b Direct comparison of the absolute C-Index in the UK Biobank (x-axis) and the All Of Us cohort (y-axis). Significant improvements can be replicated for 1347 (89.8%, green points) of 1500 endpoints in the All Of Us cohort. c Comparison of mean delta C-Index per delta percentile (derived from the UK Biobank from the 1.568 endpoints available in All Of Us). Improvements in the All Of Us cohort are consistent with the UK Biobank cohort: Small improvements in the UK Biobank tend to be larger in All Of Us, while large improvements in the UK Biobank tend to be attenuated in All Of Us. d Distribution of C-Indices for the 1.568 investigated endpoints stratified by communities historically underrepresented in biomedical research (UPD) 73 . Dots indicate medians and whiskers extend to the Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval for a distribution bootstrapped over 100 iterations. e For the same groups, confidence intervals for the additive performance as measured by the C-Index compared to the baseline model. Dots indicate medians and whiskers extend to the Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval for a distribution bootstrapped over 100 iterations. f Absolute discriminatory performance in terms of C-Index comparing the baseline (age and biological sex, black point) with the added routine health records risk state (red points) for a selection of 24 endpoints. g The differences in C-index for the same models. Statistical measures for UKB (in b and c ))were derived from 502.460 individuals and for AoU (in a – g ) were derived from 229.830 individuals. Dots indicate medians and whiskers extend to the Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval for a distribution bootstrapped over 100 iterations. Source data are provided.

As the risk states were largely derived from white, middle-aged, and generally affluent and healthy individuals from the UK, it was critical to validate the discriminative performance in diverse and historically underserved and underrepresented groups and ethnicities. Generally, we found comparable discriminative performances (Fig. 4d ) and substantial benefits over basic demographic predictors (example of cardiac arrest in Fig. 4e ) across all investigated groups.

To illustrate these improvements further, we replicated significant improvements for all of the 24 a priori selected endpoints, with improvements ranging from modest for hypertension (Delta C-Index: +0.021 (0.016, 0.024)) and Parkinson’s disease (Delta C-Index: +0.035 (0.021, 0.05)) to substantial for, e.g., All-Cause Death (Delta C-Index: +0.116 (0.104, 0.127), Pulmonary embolism (Delta C-Index: +0.125 (0.112, 0.137)), and Cardiac arrest (Delta C-Index: +0.176 (0.146, 0.206)) (Fig. 4f, g and Supplementary Data 8 ). Only for a subset of 54 (3.44%) significantly improved endpoints in the UK Biobank, the discriminative performance in All Of Us deteriorated significantly upon transferring the pre-trained medical history risk model and integrating the information beyond age and biological sex alone, including hepatitis (Delta C-Index: −0.226 (−0.251, −0.2)), substance abuse (Delta C-Index: −0.037 (−0.05, −0.026)) and osteoporosis (Delta C-Index: −0.015 (−0.021, −0.008)).

Taken together, our findings suggest that predictive models based on medical history can generalize across health systems and are robust to diverse populations.

Predictions can support cardiovascular disease prevention and the response to emerging health threats

While comprehensive phenome-wide risk profiles provide opportunities to guide medical decision-making, not all of the predictions are actionable. To illustrate the potential clinical utility, we focused on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and the response to newly emerging health threats at the example of COVID-19.

Risk scores are well established in the primary prevention of cardiovascular events and have been recommended to guide preventive lipid-lowering interventions 47 . While cardiovascular predictors are accessible at a low cost, dedicated visits and resources from healthcare providers for physical and laboratory measurements are required. Therefore, we compared our phenome-wide risk score, based only on age, sex, and routine health records, to models based on established cardiovascular risk scores, the SCORE2 48 , the ASCVD 3 , and the British QRISK3 4 score. Interestingly, the discriminative performance of our phenome-wide model is competitive with the established cardiovascular risk scores for all investigated cardiovascular endpoints (Fig. 5a , Supplementary Data 7 ): we found comparable C-Indices with differences +0.001 (CI −0.002, 0.005) for ischemic stroke, +0.002 (CI 0.002, 0.005) for ischemic heart disease and +0.006 (CI 0.003, 0.009) for myocardial infarction compared with the comprehensive QRISK3 score. It is noteworthy that these discriminative improvements are substantially better for later-stage diseases, including heart failure (+0.018 (CI 0.015, 0.021)), cardiac arrest (+0.05 (CI 0.042, 0.059)), and all-cause mortality (+0.13 (CI 0.128, 0.132)) when prior health records are considered.

a Discriminatory performances in terms of absolute C-Indices comparing risk scores (Age+Sex, SCORE2, ASCVD, and QRISK as indicated, black point) with the risk model based on Age+Sex+RiskState (red segment). b Direct differences between risk scores (Age+Sex, SCORE2, ASCVD, and QRISK as indicated) and the risk model based on Age+Sex+RiskState in terms of C-index. Dots indicate medians and whiskers extend to the Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval for a distribution bootstrapped over 100 iterations. c Estimated cumulative event trajectories, including 95% confidence intervals of severe (with hospitalization) and fatal (death registry) COVID-19 outcomes stratified by the Top, Median, and Bottom 5% based on age (left) or risk states of pneumonia, sepsis, and all-cause mortality as estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Statistical measures were derived from 502.460 individuals. Source data are provided.

To further illustrate potential utility, we look at newly emerging pathogenic health threats, where rapid and reliable risk stratification is required to protect high-risk groups and prioritize preventive interventions. We investigated how our phenome-wide risk states could have been used in the context of COVID-19, a respiratory infection with pneumonia and sepsis as common, life-threatening complications of severe cases. We repurposed the risk states for pneumonia, sepsis, and all-cause mortality to calculate a combined COVID-19 severity risk score using information available at the end of 2019 before the global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Methods for details). The COVID-19 severity risk score resembles the risk for developing severe or fatal COVID-19 and illustrates how health records could have helped to identify individuals at high risk and to prioritize individuals in initial vaccination campaigns better. Augmenting age with the COVID-19 severity risk score, we found substantially improved discriminative performance for both severe and fatal COVID-19 outcomes (Severe: C-Index (age) 0.597 (CI 0.591, 0.604) → C-Index (age + COVID-19 severity risk score) 0.647 (CI 0.641, 0.654); Fatal: C-Index (age) 0.720 (CI 0.710, 0.731) → C-Index (age + COVID-19 severity risk score) 0.780 (CI 0.772, 0.789). These discriminative improvements translate into higher cumulative incidence in the Top 5% population compared to age alone (Suppl. Figure 6C , age (left), COVID-19 severity score (right), severe COVID-19 (top), fatal COVID-19 (bottom)): In the top 5% of the age-based risk group (~79 (IQR 77, 81) years old), 0.42% (CI 0.34%, 0.5%, n = 105) have been hospitalized, and 0.26% (CI 0.2%, 0.33%, n = 66) had died by the end of the first wave. By the end of the second wave, around 0.96% (CI 0.83%, 1.08%, n = 240) had been hospitalized, and 0.44% (0.36%, 0.52%, n = 111) had died. In contrast, for individuals in the top 5% of the COVID-19 severity risk score, by the end of the first wave, around 0.64% (CI 0.54%, 0.74%, n = 160) had been hospitalized, and 0.32% (0.25%, 0.39%, n = 80) had died, while by the end of the second wave, 1.74% (CI 1.57%, 1.9%, n = 436) had been hospitalized and 0.68% (0.58%, 0.79%, n = 172) had died.

In summary, our findings illustrate the clinical utility of medical history for primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases and the rapid response to emerging health threats.

Current clinical practice lacks systematic, data-driven guidance for individuals and care providers. Our study demonstrated that medical history can systematically inform on phenome-wide risk across clinical specialties, as shown in the British UK Biobank cohort. Subsequently, we show that these risk states can be repurposed to identify individuals vulnerable to severe COVID-19 and mortality. Importantly, we found significant improvements in the discriminated performance for the vast majority of disease endpoints, of which almost 90% could be replicated in the US All of US cohort. Our results indicated utility beyond age, sex, selected comorbidities, and established cardiovascular risk factors commonly considered in clinical practice for preventable diseases, treatable diseases, and diseases without existing risk stratification tools. We anticipate that our approach has the potential to facilitate population health at scale.

Designed for outpatient settings and focused on patients without acute complaints, our approach identifies incident disease onset from early (e.g., hypertension) and later (e.g., bypass surgery) health system contacts. We identified three primary scenarios of potential utility: Firstly, medical history can be exploited in diseases that are preventable with effective interventions, such as the prescription of lipid-lowering medication for primary prevention of coronary heart disease 47 . Lowering LDL cholesterol in 10,000 individuals at increased risk by 2 mmol/L with atorvastatin 40 mg daily (~2€ per month) for 5 years is estimated to prevent 500 vascular events, reducing the individual relative risk by more than a third 49 , 50 . Secondly, in conditions that are not preventable anymore individuals can benefit from early detection and treatment, like in type 2 diabetes or systolic heart failure. In individuals with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, a comprehensive treatment regime (including ARNI, beta-blockers, MRA, and SGLT2 inhibitors) compared to a conventional regime (ACEi or ARB and beta blockers) reduced the hospital admissions for heart failure by more than two thirds, all-cause mortality by almost half 51 . For a 55-year-old male, this translated into an estimated 8.3 additional years free from cardiovascular death or readmission for heart failure. Lastly, in cases where outcomes are neither preventable nor treatable, estimates of prospective individual risk may be of high importance for personal decisions or the planning of advanced care, e.g., a high short-term mortality could identify patients needing to transition from curative to palliative strategies for optimal care 52 , 53 . Multiple studies have shown that palliative care services can improve patients’ symptoms and life quality and may even increase survival 54 . Overall, our approach could facilitate the identification of high-risk populations for specific screening programs, potentially improving the value of national health programs.

Importantly, our approach, based on routine health records, shows large discriminative improvements for the majority of diseases compared with conventionally tested biomarkers 55 , 56 , 57 and can generalize across diverse health systems, populations, and ethnicities. However, we also see that including the medical history over age and sex deteriorated the performance for a subset of 1.2% (UK Biobank) and 4.9% (All Of Us cohort), respectively. Three central challenges remain: First, health records, being products of interactions with the medical system, are subject to biological, procedural, and socio-economic biases 58 , as well as being dependent on the evolving nature of medical knowledge and policies. Furthermore, certain measurements and laboratory values are often inaccessible at the point of care, and harmonization in and across health systems presents a significant barrier to implementation 59 . Integrating these measures into the model holds considerable promise to improve the predictive performance further. While our approach is based on the standardized OMOP vocabulary, implementation requires a robust harmonization infrastructure, and data drift might necessitate model updates. Second, research cohorts often comprise healthier individuals with lower disease prevalence than the general population 60 , potentially leading to underestimating absolute risks. While discriminative improvements provide evidence of the potential clinical utility, they are insufficient to prove it, as it is highly context-dependent on the population, the disease, and the interventions available. This is particularly relevant for very rare diseases, where screening the general population poses the risk of false positive findings. Future randomized implementation studies must investigate how this discriminatory information can translate into improved clinical outcomes in the respective target populations. The third challenge concerns ensuring the interpretability of our approach on such complex data. Our approach provided unique insights into how the model used patients’ medical history to make risk predictions. The Shapley value attributions highlighted features the model found most informative for inference on both individual and population levels. These attributions are reflective of the model’s decision-making process, and while they aligned with our clinical understanding, they should not replace clinician judgment or other forms of evidence. As we refine and deploy this approach, we must remain vigilant in evaluating its performance and understanding the interpretational limitations. Interestingly, the attributions also expose the challenges of implementing predictive models across primary care and clinical specialties. For example, statins and chest pain are among the most highly attributed records for a high future likelihood of developing heart disease, indicating that in some cases, prior healthcare providers have already considered or even acted upon a high suspected risk of the disease, without entering the actual diagnosis into the records. Consequently, employing the model for such patients, when low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels are already managed, may not lead to further preventive actions if the patient’s care aligns with established standards. Importantly, we find that such cases do not drive the model’s predictive performance by assessing the robustness of the model performance to the removal of recent information (Supplementary Fig. 6 ). Ultimately, if routine health records are to be used for risk prediction, robust governance rules to protect individuals, such as opt-out and usage reports, need to be implemented. With many national initiatives emerging to curate routine health records for millions of individuals in the general population, future studies will allow us to better understand how to overcome these challenges.

Our study presents a systematic approach to simultaneous risk stratification for thousands of diseases across clinical specialties based on readily available medical history. These risk states can then be used to rapidly respond to emerging health threats such as COVID-19. Our findings demonstrate the potential to link clinical practice with already collected data to inform and guide preventive interventions, early diagnosis, and treatment of disease.

Data source and definitions of predictors and endpoints

To derive risk states, we analyzed data from the UK Biobank cohort. Participants were enrolled from 2006 to 2010 in 22 recruitment centers across England, Scotland, and Wales; the follow-up is ongoing, and records until the 24th of September 2021 are included in this analysis. The UK Biobank cohort comprises 273.353 women and 229.107 men aged between 37-73 years at the time of their assessment visit. Participants are linked to routinely collected records from primary care (GP), hospital records (HES, PEDW, and SMR), and death registries (ONS), providing longitudinal information on diagnosis, procedures, and prescriptions for the entire cohort from Scotland, Wales, and England. Routine health records were mapped to the OMOP CDM and represented as a 71.036-dimensional binary vector, indicating whether a concept has been recorded at least once in an individual prior to recruitment. A subset of 15.595 unique concepts, all found in at least 50 individuals, was chosen for model development. Endpoints were defined as the set of PheCodes X 39 , 61 , and after the exclusion of very rare endpoints (recorded in <100 individuals), 1883 PheCodes X endpoints were included in the development of the models. Due to the adult population, congenital, developmental, and neonatal endpoints were excluded. For each endpoint, subsequently, time-to-event outcomes were extracted, defined by the first occurrence after recruitment in primary care, hospital, or death records. Detailed information on the predictors and endpoints is provided in Supplementary Data 1 - 2 .

While all individuals in the UK Biobank were used to integrate the routine health records, develop the model, and estimate phenome-wide log partial hazards, individuals were excluded from endpoint-specific downstream analysis if they were already diagnosed with a disease (defined by a prior record of the respective endpoint) or are generally not eligible for the specific endpoint (females were excluded from the risk estimation for prostate cancer).

To externally validate our risk states, we investigate individuals from the All of Us cohort 37 , containing information on 229,830 individuals of diverse descent and from minorities historically underrepresented in biomedical research 40 . Because we only use the All of Us cohort for validation, we evaluate the predictive performance for the subset of 1568 endpoints with at least 100 incident events in the All of Us cohort.

The study adhered to the TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis) statement for reporting 62 . The completed checklist can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Extraction and preparation of the routine health records

To extract the routine health records of each individual, we first aggregated the linked primary care, hospital records, and mortality records and mapped the aggregated records to the OMOP CDM (mostly SNOMED and RxNorm). Specifically, we used mapping tables provided by the UK Biobank, the OHDSI community, and SNOMED International to map concepts from the provider and country-specific non-standard vocabularies to OMOP standard vocabularies.