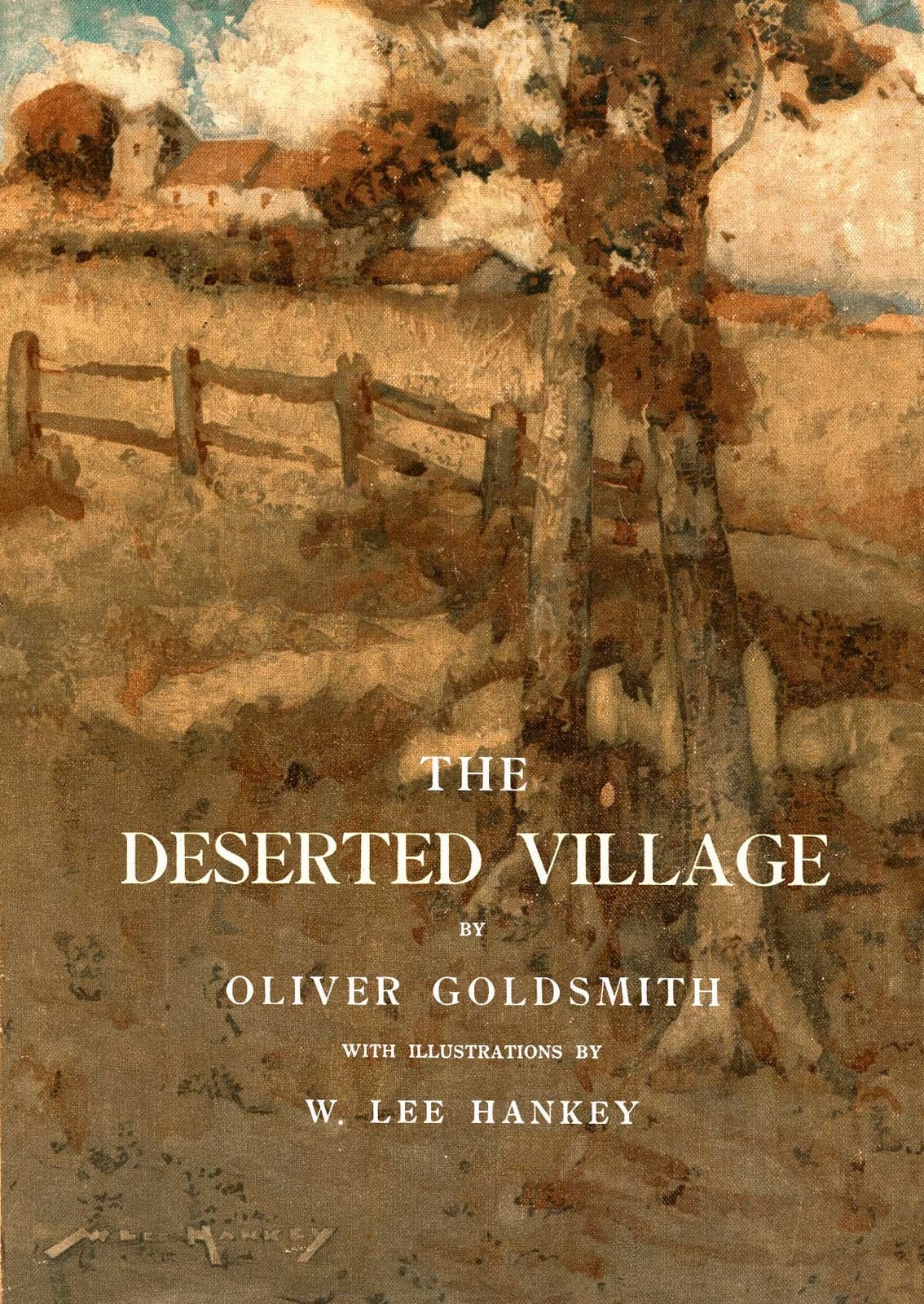

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: Oliver Goldsmith]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/golds.jpg)

OLIVER GOLDSMITH (Sir Joshua Reynolds)

OXFORD EDITION

The complete poetical works of oliver goldsmith.

Edited with Introduction and Notes by AUSTIN DOBSON HON. LL.D. EDIN.

PREFATORY NOTE

This volume is a reprint, extended and revised, of the Selected Poems of Goldsmith issued by the Clarendon Press in 1887. It is ‘extended,’ because it now contains the whole of Goldsmith’s poetry: it is ‘revised’ because, besides the supplementary text, a good deal has been added in the way of annotation and illustration. In other words, the book has been substantially enlarged. Of the new editorial material, the bulk has been collected at odd times during the last twenty years; but fresh Goldsmith facts are growing rare. I hope I have acknowledged obligation wherever it has been incurred; I trust also, for the sake of those who come after me, that something of my own will be found to have been contributed to the literature of the subject.

AUSTIN DOBSON.

Ealing, September , 1906.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Introduction.

Two of the earlier, and, in some respects, more important Memoirs of Oliver Goldsmith open with a quotation from one of his minor works, in which he refers to the generally uneventful life of the scholar. His own chequered career was a notable exception to this rule. He was born on the 10th of November, 1728, at Pallas, a village in the county of Longford in Ireland, his father, the Rev. Charles Goldsmith, being a clergyman of the Established Church. Oliver was the fifth of a family of five sons and three daughters. In 1730, his father, who had been assisting the rector of the neighbouring parish of Kilkenny West, succeeded to that living, and moved to Lissoy, a hamlet in Westmeath, lying a little to the right of the road from Ballymahon to Athlone. Educated first by a humble relative named Elizabeth Delap, the boy passed subsequently to the care of Thomas Byrne, the village schoolmaster, an old soldier who had fought Queen Anne’s battles in Spain, and had retained from those experiences a wandering and unsettled spirit, which he is thought to have communicated to one at least of his pupils. After an attack of confluent small-pox, which scarred him for life, Oliver was transferred from the care of this not-uncongenial preceptor to a school at Elphin. From Elphin he passed to Athlone; from Athlone to Edgeworthstown, where he remained until he was thirteen or fourteen years of age. The accounts of these early days are contradictory. By his schoolfellows he seems to have been regarded as stupid and heavy,—‘little better than a fool’; but they admitted that he was remarkably active and athletic, and that he was an adept in all boyish sports. At home, notwithstanding a variable disposition, and occasional fits of depression, he showed to greater advantage. He scribbled verses early; and sometimes startled those about him by unexpected ‘swallow-flights’ of repartee. One of these, an oft-quoted retort to a musical friend who had likened his awkward antics in a hornpipe to the dancing of Aesop,—

Heralds! proclaim aloud! all saying, See Aesop dancing, and his monkey playing,—

reads more like a happily-adapted recollection than the actual impromptu of a boy of nine. But another, in which, after a painful silence, he replied to the brutal enquiry of a ne’er-do-well relative as to when he meant to grow handsome, by saying that he would do so when the speaker grew good,—is characteristic of the easily-wounded spirit and ‘exquisite sensibility of contempt’ with which he was to enter upon the battle of life.

In June, 1744, after anticipating in his own person, the plot of his later play of She Stoops to Conquer by mistaking the house of a gentleman at Ardagh for an inn, he was sent to Trinity College, Dublin. The special dress and semi-menial footing of a sizar or poor scholar—for his father, impoverished by the imprudent portioning of his eldest daughter, could not afford to make him a pensioner—were scarcely calculated to modify his personal peculiarities. Added to these, his tutor elect, Dr. Theaker Wilder, was a violent and vindictive man, with whom his ungainly and unhopeful pupil found little favour. Wilder had a passion for mathematics which was not shared by Goldsmith, who, indeed, spoke contemptuously enough of that science in after life. He could, however, he told Malone, ‘turn an Ode of Horace into English better than any of them.’ But his academic career was not a success.

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: Goldsmith’s Autograph]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/glasspane.jpg)

PANE OF GLASS WITH GOLDSMITH’S AUTOGRAPH (Trinity College, Dublin)

In May, 1747, the year in which his father died,—an event that further contracted his already slender means,—he became involved in a college riot, and was publicly admonished. From this disgrace he recovered to some extent in the following month by obtaining a trifling money exhibition, a triumph which he unluckily celebrated by a party at his rooms. Into these festivities, the heinousness of which was aggravated by the fact that they included guests of both sexes, the exasperated Wilder made irruption, and summarily terminated the proceedings by knocking down the host. The disgrace was too much for the poor lad. He forthwith sold his books and belongings, and ran away, vaguely bound for America. But after considerable privations, including the achievement of a destitution so complete that a handful of grey peas, given him by a girl at a wake, seemed a banquet, he turned his steps homeward, and, a reconciliation having been patched up with his tutor, he was received once more at college. In February, 1749, he took his degree, a low one, as B.A., and quitted the university, leaving behind him, for relics of that time, a scratched signature upon a window-pane, a folio Scapula scored liberally with ‘promises to pay,’ and a reputation for much loitering at the college gates in the study of passing humanity. Another habit which his associates recalled was his writing of ballads when in want of funds. These he would sell at five shillings apiece; and would afterwards steal out in the twilight to hear them sung to the indiscriminate but applauding audience of the Dublin streets.

What was to be done with a genius so unstable, so erratic? Nothing, apparently, but to let him qualify for orders, and for this he is too young. Thereupon ensues a sort of ‘Martin’s summer’ in his changing life,—a disengaged, delightful time when ‘Master Noll’ wanders irresponsibly from house to house, fishing and flute-playing, or, of winter evenings, taking the chair at the village inn. When at last the moment came for his presentation to the Bishop of Elphin, that prelate, sad to say, rejected him, perhaps because of his college reputation, perhaps because of actual incompetence, perhaps even, as tradition affirms, because he had the bad taste to appear before his examiner in flaming scarlet breeches. After this rebuff, tutoring was next tried. But he had no sooner saved some thirty pounds by teaching, than he threw up his engagement, bought a horse, and started once more for America, by way of Cork. In six weeks he had returned penniless, having substituted for his roadster a sorry jade, to which he gave the contemptuous name of Fiddleback. He had also the simplicity to wonder, on this occasion, that his mother was not rejoiced to see him again. His next ambition was to be a lawyer; and, to this end, a kindly Uncle Contarine equipped him with fifty pounds for preliminary studies. But on his way to London he was decoyed into gambling, lost every farthing, and came home once more in bitter self-abasement. Having now essayed both divinity and law, his next attempt was physic; and, in 1752, fitted out afresh by his long-suffering uncle, he started for, and succeeded in reaching, Edinburgh. Here more memories survive of his social qualities than of his studies; and two years later he left the Scottish capital for Leyden, rather, it may be conjectured, from a restless desire to see the world than really to exchange the lectures of Monro for the lectures of Albinus. At Newcastle (according to his own account) he had the good fortune to be locked up as a Jacobite, and thus escaped drowning, as the ship by which he was to have sailed to Bordeaux sank at the mouth of the Garonne. Shortly afterwards he arrived in Leyden. Gaubius and other Dutch professors figure sonorously in his future works; but whether he had much experimental knowledge of their instructions may be doubted. What seems undeniable is, that the old seduction of play stripped him of every shilling; so that, like Holberg before him, he set out deliberately to make the tour of Europe on foot. Haud inexpertus loquor, he wrote in after days, when praising this mode of locomotion. He first visited Flanders. Thence he passed to France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, supporting himself mainly by his flute, and by occasional disputations at convents or universities. ‘Sir,’ said Boswell to Johnson, ‘he disputed his passage through Europe.’ When on the 1st February, 1756, he landed at Dover, it was with empty pockets. But he had sent home to his brother in Ireland his first rough sketch for the poem of The Traveller .

He was now seven-and-twenty. He had seen and suffered much, but he was to have further trials before drifting definitely into literature. Between Dover and London, it has been surmised, he made a tentative appearance as a strolling player. His next ascertained part was that of an apothecary’s assistant on Fish Street Hill. From this, with the opportune aid of an Edinburgh friend, he proceeded—to use an eighteenth-century phrase—a poor physician in the Bankside, Southwark, where least of all, perhaps, was London’s fabled pavement to be found. So little of it, in fact, fell to Goldsmith’s share, that we speedily find him reduced to the rank of reader and corrector of the press to Samuel Richardson, printer, of Salisbury Court, author of Clarissa . Later still he is acting as help or substitute in Dr. Milner’s ‘classical academy’ at Peckham. Here, at last, chance seemed to open to him the prospect of a literary life. He had already, says report, submitted a manuscript tragedy to Richardson’s judgement; and something he said at Dr. Milner’s table attracted the attention of an occasional visitor there, the bookseller Griffiths, who was also proprietor of the Monthly Review. He invited Dr. Milner’s usher to try his hand at criticism; and finally, in April, 1757, Goldsmith was bound over for a year to that venerable lady whom George Primrose dubs ‘the antiqua mater of Grub Street’—in other words, he was engaged for bed, board, and a fixed salary to supply copy-of-all-work to his master’s magazine.

The arrangement thus concluded was not calculated to endure. After some five months of labour from nine till two, and often later, it came suddenly to an end. No clear explanation of the breach is forthcoming, but mere incompatability of temper would probably supply a sufficient ground for disagreement. Goldsmith, it is said, complained that the bookseller and his wife treated him ill, and denied him ordinary comforts; added to which the lady, a harder taskmistress even than the antiqua mater above referred to, joined with her husband in ‘editing’ his articles, a course which, hard though it may seem, is not unprecedented. However this may be, either in September or October, 1757, he was again upon the world, existing precariously from hand to mouth. ‘By a very little practice as a physician, and very little reputation as a poet [a title which, as Prior suggests, possibly means no more than author], I make a shift to live.’ So he wrote to his brother-in-law in December. What his literary occupations were cannot be definitely stated; but, if not prepared before, they probably included the translation of a remarkable work issued by Griffiths and others in the ensuing February. This was the Memoirs of a Protestant, condemned to the Galleys of France for his Religion, being the authentic record of the sufferings of one Jean Marteilhe of Bergerac, a book of which Michelet has said that it is ‘written as if between earth and heaven.’ Marteilhe, who died at Cuylenberg in 1777, was living in Holland in 1758; and it may be that Goldsmith had seen or heard of him during his own stay in that country. The translation, however, did not bear Goldsmith’s name, but that of James Willington, one of his old class-fellows at Trinity College. Nevertheless, Prior says distinctly that Griffiths (who should have known) declared it to be by Goldsmith. Moreover, the French original had been catalogued in Griffiths’ magazine in the second month of Goldsmith’s servitude, a circumstance which colourably supplies the reason for its subsequent rendering into English.

The publication of Marteilhe’s Memoirs had no influence upon Goldsmith’s fortunes, for, in a short time, he was again installed at Peckham, in place of Dr. Milner invalided, waiting hopefully for the fulfilment of a promise by his old master to procure him a medical appointment on a foreign station. It is probably that, with a view to provide the needful funds for this expatriation, he now began to sketch the little volume afterwards published under the title of An Enquiry into the Present State of Polite Learning in Europe , for towards the middle of the year we find him addressing long letters to his relatives in Ireland to enlist their aid in soliciting subscriptions for this book. At length the desired advancement was obtained,—a nomination as a physician and surgeon to one of the factories on the coast of Coromandel. But banishment to the East Indies was not to be his destiny. For some unexplained reason the project came to nothing; and then—like Roderick Random—he presented himself at Surgeons’ Hall for the more modest office of a hospital mate. This was on the 21st of December, 1758. The curt official record states that he was ‘found not qualified.’ What made matters worse, the necessity for a decent appearance before the examiners had involved him in new obligations to Griffiths, out of which arose fresh difficulties. To pay his landlady, whose husband was arrested for debt, he pawned the suit he had procured by Griffiths’ aid; and he also raised money on some volumes which had been sent him for review. Thereupon ensued an angry and humiliating correspondence with the bookseller, as a result of which Griffiths, nevertheless, appears to have held his hand.

By this time Goldsmith had moved into those historic but now non-existent lodgings in 12 Green Arbour Court, Old Bailey, which have been photographed for ever in Irving’s Tales of a Traveller. It was here that the foregoing incidents took place; and it was here also that, early in 1759, ‘in a wretched dirty room, in which there was but one chair,’ the Rev. Thomas Percy, afterwards Bishop of Dromore, found him composing (or more probably correcting the proofs of) The Enquiry. ‘At least spare invective ’till my book with Mr. Dodsley shall be publish’d,’—he had written not long before to the irate Griffiths—‘and then perhaps you may see the bright side of a mind when my professions shall not appear the dictates of necessity but of choice.’ The Enquiry came out on the 2nd of April. It had no author’s name, but it was an open secret that Goldsmith had written it; and to this day it remains to the critic one of the most interesting of his works. Obviously, in a duodecimo of some two hundred widely-printed pages, it was impossible to keep the high-sounding promise of its title; and at best its author’s knowledge of the subject, notwithstanding his continental wanderings, can have been but that of an external spectator. Still in an age when critical utterance was more than ordinarily full-wigged and ponderous, it dared to be sprightly and epigrammatic. Some of its passages, besides, bear upon the writer’s personal experiences, and serve to piece the imperfections of his biography. If it brought him no sudden wealth, it certainly raised his reputation with the book-selling world. A connexion already begun with Smollett’s Critical Review was drawn closer; and the shrewd Sosii of the Row began to see the importance of securing so vivacious and unconventional a pen. Towards the end of the year he was writing for Wilkie the collection of periodical essays entitled The Bee ; and contributing to the same publisher’s Lady’s Magazine , as well as to The Busy Body of one Pottinger. In these, more than ever, he was finding his distinctive touch; and ratifying anew, with every fresh stroke of his pen, his bondage to authorship as a calling.

He had still, however, to conquer the public. The Bee , although it contains one of his most characteristic essays (‘A City Night-Piece’), and some of the most popular of his lighter verses (‘The Elegy on Mrs. Mary Blaize’), never attained the circulation essential to healthy existence. It closed with its eighth number in November, 1759. In the following month two gentlemen called at Green Arbour Court to enlist the services of its author. One was Smollett, with a new serial, The British Magazine ; the other was Johnson’s ‘Jack Whirler,’ bustling Mr. John Newbery from the ‘Bible and Sun’ in St. Paul’s Churchyard, with a new daily newspaper, The Public Ledger . For Smollett, Goldsmith wrote the ‘Reverie at the Boar’s Head Tavern’ and the ‘Adventures of a Strolling Player,’ besides a number of minor papers. For Newbery, by a happy recollection of the Lettres Persanes of Montesquieu, or some of his imitators, he struck almost at once into that charming epistolary series, brimful of fine observation, kindly satire, and various fancy, which was ultimately to become the English classic known as The Citizen of the World . He continued to produce these letters periodically until the August of the following year, when they were announced for republication in ‘two volumes of the usual Spectator size.’ In this form they appeared in May, 1762.

But long before this date a change for the better had taken place in Goldsmith’s life. Henceforth he was sure of work,—mere journey-work though much of it must have been;—and, had his nature been less improvident, of freedom from absolute want. The humble lodgings in the Old Bailey were discarded for new premises at No. 6 Wine Office Court, Fleet Street; and here, on the 31st of May, 1761, with Percy, came one whose name was often in the future to be associated with Goldsmith’s, the great Dictator of London literary society, Samuel Johnson. Boswell, who made Johnson’s acquaintance later, has not recorded the humours of that supper; but it marks the beginning of Goldsmith’s friendship with the man who of all others (Reynolds excepted) loved him most and understood him best.

During the remainder of 1761 he continued busily to ply his pen. Besides his contributions to The Ledger and The British Magazine , he edited The Lady’s Magazine , inserting in it the Memoirs of Voltaire , drawn up some time earlier to accompany a translation of the Henriade by his crony and compatriot Edward Purdon. Towards the beginning of 1762 he was hard at work on several compilations for Newbery, for whom he wrote or edited a History of Mecklenburgh , and a series of monthly volumes of an abridgement of Plutarch’s Lives . In October of the same year was published the Life of Richard Nash , apparently the outcome of special holiday-visits to the then fashionable watering-place of Bath, whence its fantastic old Master of the Ceremonies had only very lately made his final exit. It is a pleasantly gossiping, and not unedifying little book, which still holds a respectable place among its author’s minor works. But a recently discovered entry in an old ledger shows that during the latter half of 1762 he must have planned, if he had not, indeed, already in part composed, a far more important effort, The Vicar of Wakefield . For on the 28th of October in this year he sold to one Benjamin Collins, printer, of Salisbury, for 21 pounds, a third in a work with that title, further described as ‘2 vols. 12mo.’ How this little circumstance, discovered by Mr. Charles Welsh when preparing his Life of John Newbery, is to be brought into agreement with the time-honoured story, related (with variations) by Boswell and others, to the effect that Johnson negotiated the sale of the manuscript for Goldsmith when the latter was arrested for rent by his incensed landlady—has not yet been satisfactorily suggested. Possibly the solution is a simple one, referable to some of those intricate arrangements favoured by ‘the Trade’ at a time when not one but half a score publishers’ names figured in an imprint. At present, the fact that Collins bought a third share of the book from the author for twenty guineas, and the statement that Johnson transferred the entire manuscript to a bookseller for sixty pounds, seem irreconcilable. That The Vicar of Wakefield was nevertheless written, or was being written, in 1762, is demonstrable from internal evidence.

About Christmas in the same year Goldsmith moved into lodgings at Islington, his landlady being one Mrs. Elizabeth Fleming, a friend of Newbery, to whose generalship this step seems attributable. From the curious accounts printed by Prior and Forster, it is clear that the publisher was Mrs. Fleming’s paymaster, punctually deducting his disbursements from the account current between himself and Goldsmith, an arrangement which as plainly indicates the foresight of the one as it implies the improvidence of the other. Of the work which Goldsmith did for the businesslike and not unkindly little man, there is no very definite evidence; but various prefaces, introductions, and the like, belong to this time; and he undoubtedly was the author of the excellent History of England in a Series of Letters addressed by a Nobleman to his Son , published anonymously in June, 1764, and long attributed, for the grace of its style, to Lyttelton, Chesterfield, Orrery, and other patrician pens. Meanwhile his range of acquaintance was growing larger. The establishment, at the beginning of 1764, of the famous association known afterwards as the ‘Literary Club’ brought him into intimate relations with Beauclerk, Reynolds, Langton, Burke, and others. Hogarth, too, is said to have visited him at Islington, and to have painted the portrait of Mrs. Fleming. Later in the same year, incited thereto by the success of Christopher Smart’s Hannah , he wrote the Oratorio of The Captivity , now to be found in most editions of his poems, but never set to music. Then after the slow growth of months, was issued on the 19th December the elaboration of that fragmentary sketch which he had sent years before to his brother Henry from the Continent, the poem entitled The Traveller; or, A Prospect of Society .

In the notes appended to The Traveller in the present volume, its origin and progress are sufficiently explained. Its success was immediate and enduring. The beauty of the descriptive passages, the subtle simplicity of the language, the sweetness and finish of the versification, found ready admirers,—perhaps all the more because of the contrast they afforded to the rough and strenuous sounds with which Charles Churchill had lately filled the public ear. Johnson, who contributed a few lines at the close, proclaimed The Traveller to be the best poem since the death of Pope; and it is certainly not easy to find its equal among the works of contemporary bards. It at once raised Goldsmith from the condition of a clever newspaper essayist, or—as men like Sir John Hawkins would have said—a mere ‘bookseller’s drudge,’ to the foremost rank among the poets of the day. Another result of its success was the revival of some of his earlier work, which, however neglected by the author, had been freely appropriated by the discerning pirate. In June, 1765, Griffin and Newbery published a little volume of Essays by Mr. Goldsmith , including some of the best of his contributions to The Bee, The Busy Body, The Public Ledger , and The British Magazine , besides ‘The Double Transformation’ and ‘The Logicians Refuted,’ two pieces of verse in imitation of Prior and Swift, which have not been traced to an earlier source. To the same year belongs the first version of a poem which he himself regarded as his best work, and which still retains something of its former popularity. This was the ballad of Edwin and Angelina , otherwise known as The Hermit . It originated in certain metrical discussions with Percy, then engaged upon his famous Reliques of English Poetry ; and in 1765, Goldsmith, who through his friend Nugent (afterwards Lord Clare) had made the acquaintance of the Earl of Northumberland, printed it privately for the amusement of the Countess. In a revised and amended form it was subsequently given to the world in The Vicar of Wakefield .

With the exception of an abortive attempt to resume his practice as a medical man,—an attempt which seems to have been frustrated by the preternatural strength of his prescriptions,—the next memorable thing in Goldsmith’s life is the publication of The Vicar of Wakefield itself. It made its appearance on the 27th of March, 1766. A second edition followed in May, a third in August. Why, having been sold (in part) to a Salisbury printer as far back as October, 1762, it had remained unprinted so long; and why, when published, it was published by Francis Newbery and not by John Newbery, Goldsmith’s employer,—are questions at present unsolved. But the charm of this famous novel is as fresh as when it was first issued. Its inimitable types, its happy mingling of Christianity and character, its wholesome benevolence and its practical wisdom, are still unimpaired. We smile at the inconsistencies of the plot; but we are carried onward in spite of them, captivated by the grace, the kindliness, the gentle humour of the story. Yet it is a mistake to suppose that its success was instantaneous. Pirated it was, of course; but, according to expert investigations, the authorized edition brought so little gain to its first proprietors that the fourth issue of 1770 started with a loss. The fifth, published in April, 1774, was dated 1773; and had apparently been withheld because the previous edition, which consisted of no more than one thousand copies, was not exhausted. Five years elapsed before the sixth edition made its tardy appearance in 1779. These facts show that the writer’s contemporaries were not his most eager readers. But he has long since appealed to the wider audience of posterity; and his fame is not confined to his native country, for he has been translated into most European languages. Dr. Primrose and his family are now veritable ‘citizens of the world.’

A selection of Poems for Young Ladies , in the ‘Moral’ division of which he included his own Edwin and Angelina ; two volumes of Beauties of English Poesy , disfigured with strange heedlessness, by a couple of the most objectionable pieces of Prior; a translation of a French history of philosophy, and other occasional work, followed the publication of the Vicar . But towards the middle of 1766, he was meditating a new experiment in that line in which Farquhar, Steele, Southerne, and others of his countrymen had succeeded before him. A fervent lover of the stage, he detested the vapid and colourless ‘genteel’ comedy which had gradually gained ground in England; and he determined to follow up The Clandestine Marriage , then recently adapted by Colman and Garrick from Hogarth’s Marriage A-la-Mode , with another effort of the same class, depending exclusively for its interest upon humour and character. Early in 1767 it was completed, and submitted to Garrick for Drury Lane. But Garrick perhaps too politic to traverse the popular taste, temporized; and eventually after many delays and disappointments, The Good Natur’d Man , as it was called, was produced at Covent Garden by Colman on the 29th of January, 1768. Its success was only partial; and in deference to the prevailing craze for the ‘genteel,’ an admirable scene of low humour had to be omitted in the representation. But the piece, notwithstanding, brought the author 400 pounds, to which the sale of the book, with the condemned passages restored, added another 100 pounds. Furthermore, Johnson, whose ‘Suspirius’ in The Rambler was, under the name of ‘Croaker,’ one of its most prominent personages, pronounced it to be the best comedy since Cibber’s Provok’d Husband .

During the autumn of 1767, Goldsmith had again been living at Islington. On this occasion he had a room in Canonbury Tower, Queen Elizabeth’s old hunting-lodge, and perhaps occupied the very chamber generally used by John Newbery, whose active life was, in this year, to close. When in London he had modest housing in the Temple. But the acquisition of 500 pounds for The Good Natur’d Man seemed to warrant a change of residence, and he accordingly expended four-fifths of that sum for the lease of three rooms on the second floor of No. 2 Brick Court, which he straightway proceeded to decorate sumptuously with mirrors, Wilton carpets, moreen curtains, and Pembroke tables. It was an unfortunate step; and he would have done well to remember the Nil te quaesiveris extra with which his inflexible monitor, Johnson, had greeted his apologies for the shortcomings of some earlier lodgings. One of its natural results was to involve him in a new sequence of task-work, from which he never afterwards shook himself free. Hence, following hard upon a Roman History which he had already engaged to write for Davies of Russell Street, came a more ambitious project for Griffin, A History of Animated Nature ; and after this again, another History of England for Davies. The pay was not inadequate; for the first he was to have 250 guineas, for the second 800 guineas, and for the last 500 pounds. But as employment for the author of a unique novel, an excellent comedy, and a deservedly successful poem, it was surely—in his own words—‘to cut blocks with a razor.’

And yet, apart from the anxieties of growing money troubles, his life could not have been wholly unhappy. There are records of pleasant occasional junketings—‘shoe-maker’s holidays’ he called them—in the still countrified suburbs of Hampstead and Edgware; there was the gathering at the Turk’s Head, with its literary magnates, for his severer hours; and for his more pliant moments, the genial ‘free-and-easy’ or shilling whist-club of a less pretentious kind, where the student of mixed character might shine with something of the old supremacy of George Conway’s inn at Ballymahon. And there must have been quieter and more chastened resting-places of memory, when, softening towards the home of his youth, with a sadness made more poignant by the death of his brother Henry in May, 1768, he planned and perfected his new poem of The Deserted Village .

In December, 1769, the recent appointment of his friend Reynolds as President of the Royal Academy brought him the honorary office of Professor of History to that institution; and to Reynolds The Deserted Village was dedicated. It appeared on the 26th of May, 1770, with a success equal, if not superior, to that of The Traveller . It ran through five editions in the year of its publication; and has ever since retained its reputation. If, as alleged, contemporary critics ranked it below its predecessor, the reason advanced by Washington Irving, that the poet had become his own rival, is doubtless correct; and there is always a prejudice in favour of the first success. This, however, is not an obstacle which need disturb the reader now; and he will probably decide that in grace and tenderness of description The Deserted Village in no wise falls short of The Traveller ; and that its central idea, and its sympathy with humanity, give it a higher value as a work of art.

After The Deserted Village had appeared, Goldsmith made a short trip to Paris, in company with Mrs. and the two Miss Hornecks, the elder of whom, christened by the poet with the pretty pet-name of ‘The Jessamy Bride,’ is supposed to have inspired him with more than friendly feelings. Upon his return he had to fall again to the old ‘book-building’ in order to recruit his exhausted finances. Since his last poem he had published a short Life of Parnell ; and Davies now engaged him on a Life of Bolingbroke , and an abridgement of the Roman History . Thus, with visits to friends, among others to Lord Clare, for whom he wrote the delightful occasional verses called The Haunch of Venison , the months wore on until, in December, 1770, the print-shops began to be full of the well-known mezzotint which Marchi had engraved from his portrait by Sir Joshua.

His chief publications in the next two years were the above-mentioned History of England , 1771; Threnodia Augustalis , a poetical lament-to-order on the death of the Princess Dowager of Wales, 1772; and the abridgement of the Roman History , 1772. But in the former year he had completed a new comedy, She Stoops to Conquer; or, The Mistakes of a Night , which, after the usual vexatious negotiations, was brought out by Colman at Covent Garden on Monday, the 15th of March, 1773. The manager seems to have acted Goldsmith’s own creation of ‘Croaker’ with regard to this piece, and even to the last moment predicted its failure. But it was a brilliant success. More skilful in construction than The Good Natur’d Man , more various in its contrasts of character, richer and stronger in humour and vis comica , She Stoops to Conquer has continued to provide an inexhaustible fund of laughter to more than three generations of playgoers, and still bids fair to retain the character generally given to it, of being one of the three most popular comedies upon the English stage. When published, it was gratefully inscribed, in one of those admirable dedications of which its author above all men possessed the secret, to Johnson, who had befriended it from the first. ‘I do not mean,’ wrote Goldsmith, ‘so much to compliment you as myself. It may do me some honour to inform the public, that I have lived many years in intimacy with you. It may serve the interests of mankind also to inform them, that the greatest wit may be found in a character, without impairing the most unaffected piety.’

His gains from She Stoops to Conquer were considerable; but by this time his affairs had reached a stage of complication which nothing short of a miracle could disentangle; and there is reason for supposing that his involved circumstances preyed upon his mind. During the few months of life that remained to him he published nothing, being doubtless sufficiently occupied by the undertakings to which he was already committed. The last of his poetical efforts was the poem entitled Retaliation , a group of epitaph-epigrams prompted by some similar jeux d’esprit directed against himself by Garrick and other friends, and left incomplete at his death. In March, 1774, the combined effects of work and worry, added to a local disorder, brought on a nervous fever, which he unhappily aggravated by the use of a patent medicine called ‘James’s Powder.’ He had often relied upon this before, but in the present instance it was unsuited to his complaint. On Monday, the 4th of April, 1774, he died, in his forty-sixth year, and was buried on the 9th in the burying-ground of the Temple Church. Two years later a monument, with a medallion portrait by Nollekens, and a Latin inscription by Johnson, was erected to him in Westminster Abbey, at the expense of the Literary Club. But although the inscription contains more than one phrase of felicitous discrimination, notably the oft-quoted affectuum potens, at lenis dominator , it may be doubted whether the simpler words used by his rugged old friend in a letter to Langton are not a fitter farewell to Oliver Goldsmith,—‘Let not his frailties be remembered; he was a very great man.’

In person Goldsmith was short and strongly built. His complexion was rather fair, but he was deeply scarred with small-pox; and—if we may believe his own account—the vicissitudes and privations of his early life had not tended to diminish his initial disadvantages. ‘You scarcely can conceive,’ he writes to his brother in 1759, ‘how much eight years of disappointment, anguish, and study, have worn me down. . . . Imagine to yourself a pale melancholy visage, with two great wrinkles between the eye-brows, with an eye disgustingly severe, and a big wig; and you may have a perfect picture of my present appearance,’ i.e. at thirty years of age. ‘I can neither laugh nor drink,’ he goes on; ‘have contracted an hesitating, disagreeable manner of speaking, and a visage that looks ill-nature itself; in short, I have thought myself into a settled melancholy, and an utter disgust of all that life brings with it.’ It is obvious that this description is largely coloured by passing depression. ‘His features,’ says one contemporary, ‘were plain, but not repulsive,—certainly not so when lighted up by conversation.’ Another witness—the ‘Jessamy Bride’—declares that ‘his benevolence was unquestionable, and his countenance bore every trace of it.’ His true likeness would seem to lie midway between the grotesquely truthful sketch by Bunbury prefixed in 1776 to the Haunch of Venison , and the portrait idealized by personal regard, which Reynolds painted in 1770. In this latter he is shown wearing, in place of his customary wig, his own scant brown hair, and, on this occasion, masquerades in a furred robe, and falling collar. But even through the disguise of a studio ‘costume,’ the finely-perceptive genius of Reynolds has managed to suggest much that is most appealing in his sitter’s nature. Past suffering, present endurance, the craving to be understood, the mute deprecation of contempt, are all written legibly in this pathetic picture. It has been frequently copied, often very ineffectively, for so subtle is the art that the slightest deviation hopelessly distorts and vulgarizes what Reynolds has done supremely, once and for ever.

Goldsmith’s character presents but few real complexities. What seems most to have impressed his contemporaries is the difference, emphasized by the happily-antithetic epigram of Garrick, between his written style and his conversation; and collaterally, between his eminence as a literary man and his personal insignificance. Much of this is easily intelligible. He had started in life with few temporal or physical advantages, and with a native susceptibility that intensified his defects. Until he became a middle-aged man, he led a life of which we do not even now know all the degradations; and these had left their mark upon his manners. With the publication of The Traveller , he became at once the associate of some of the best talent and intellect in England,—of fine gentlemen such as Beauclerk and Langton, of artists such as Reynolds and Garrick, of talkers such as Johnson and Burke. Morbidly self-conscious, nervously anxious to succeed, he was at once forced into a competition for which neither his antecedents nor his qualifications had prepared him. To this, coupled with the old habit of poverty, must be attributed his oft-cited passion for fine clothes, which surely arose less from vanity than from a mistaken attempt to extenuate what he felt to be his most obvious shortcomings. As a talker especially he was ill-fitted to shine. He was easily disconcerted by retort, and often discomfited in argument. To the end of his days he never lost his native brogue; and (as he himself tells us) he had that most fatal of defects to a narrator, a slow and hesitating manner. The perspicuity which makes the charm of his writings deserted him in conversation; and his best things were momentary flashes. But some of these were undoubtedly very happy. His telling Johnson that he would make the little fishes talk like whales; his affirmation of Burke that he wound into a subject like a serpent; and half-a-dozen other well-remembered examples—afford ample proof of this. Something of the uneasy jealousy he is said to have exhibited with regard to certain of his contemporaries may also be connected with the long probation of obscurity during which he had been a spectator of the good fortune of others, to whom he must have known himself superior. His improvidence seems to have been congenital, since it is to be traced ‘even from his boyish days.’ But though it cannot justly be ascribed to any reaction from want to sufficiency, it can still less be supposed to have been diminished by that change. If he was careless of money, it must also be remembered that he gave much of it away; and fortune lingers little with those whose ears are always open to a plausible tale of distress. Of his sensibility and genuine kindheartedness there is no doubt. And it is well to remember that most of the tales to his disadvantage come, not from his more distinguished companions, but from such admitted detractors as Hawkins and Boswell. It could be no mean individuality that acquired the esteem, and deserved the regret, of Johnson and Reynolds.

In an edition of Goldsmith’s poems, any extended examination of his remaining productions would be out of place. Moreover, the bulk of these is considerably reduced when all that may properly be classed as hack-work has been withdrawn. The histories of Greece, of Rome, and of England; the Animated Nature ; the lives of Nash, Voltaire, Parnell, and Bolingbroke, are merely compilations, only raised to the highest level in that line because they proceeded from a man whose gift of clear and easy exposition lent a charm to everything he touched. With the work which he did for himself, the case is different. Into The Citizen of the World , The Vicar of Wakefield , and his two comedies, he put all the best of his knowledge of human nature, his keen sympathy with his kind, his fine common-sense and his genial humour. The same qualities, tempered by a certain grace and tenderness, also enter into the best of his poems. Avoiding the epigram of Pope and the austere couplet of Johnson, he yet borrowed something from each, which he combined with a delicacy and an amenity that he had learned from neither. He himself, in all probability, would have rested his fame on his three chief metrical efforts, The Traveller , The Hermit , and The Deserted Village . But, as is often the case, he is remembered even more favourably by some of those delightful familiar verses, unprinted during his lifetime, which he threw off with no other ambition than the desire to amuse his friends. Retaliation , The Haunch of Venison , the Letter in Prose and Verse to Mrs. Bunbury , all afford noteworthy exemplification of that playful touch and wayward fancy which constitute the chief attraction of this species of poetry. In his imitations of Swift and Prior, and his variations upon French suggestions, his personal note is scarcely so apparent; but the two Elegies and some of the minor pieces retain a deserved reputation. His ingenious prologues and epilogues also serve to illustrate the range and versatility of his talent. As a rule, the arrangement in the present edition is chronological; but it has not been thought necessary to depart from the practice which gives a time-honoured precedence to The Traveller and The Deserted Village . The true sequence of the poems, in their order of publication, is, however, exactly indicated in the table which follows this Introduction.

CHRONOLOGY OF GOLDSMITH’S LIFE AND POEMS.

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: Vignette to ‘The Traveller’]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/vignette.jpg)

VIGNETTE TO ‘THE TRAVELLER’ (Samuel Wale)

DESCRIPTIVE POEMS

THE TRAVELLER OR A PROSPECT OF SOCIETY DEDICATION TO THE REV. HENRY GOLDSMITH

D EAR S IR , I am sensible that the friendship between us can acquire no new force from the ceremonies of a Dedication; and perhaps it demands an excuse thus to prefix your name to my attempts, which you decline giving with your own. But as a part of this Poem was formerly written to you from Switzerland, the whole can now, with propriety, be only inscribed to you. It will also throw a light upon many parts of it, when the reader understands, that it is addressed to a man, who, despising Fame and Fortune, has retired early to Happiness and Obscurity, with an income of forty pounds a year.

I now perceive, my dear brother, the wisdom of your humble choice. You have entered upon a sacred office, where the harvest is great, and the labourers are but few; while you have left the field of Ambition, where the labourers are many, and the harvest not worth carrying away. But of all kinds of ambition, what from the refinement of the times, from different systems of criticism, and from the divisions of party, that which pursues poetical fame is the wildest.

Poetry makes a principal amusement among unpolished nations; but in a country verging to the extremes of refinement, Painting and Music come in for a share. As these offer the feeble mind a less laborious entertainment, they at first rival Poetry, and at length supplant her; they engross all that favour once shown to her, and though but younger sisters, seize upon the elder’s birthright.

Yet, however this art may be neglected by the powerful, it is still in greater danger from the mistaken efforts of the learned to improve it. What criticisms have we not heard of late in favour of blank verse, and Pindaric odes, choruses, anapaests and iambics, alliterative care and happy negligence! Every absurdity has now a champion to defend it; and as he is generally much in the wrong, so he has always much to say; for error is ever talkative.

But there is an enemy to this art still more dangerous, I mean Party. Party entirely distorts the judgment, and destroys the taste. When the mind is once infected with this disease, it can only find pleasure in what contributes to increase the distemper. Like the tiger, that seldom desists from pursuing man after having once preyed upon human flesh, the reader, who has once gratified his appetite with calumny, makes, ever after, the most agreeable feast upon murdered reputation. Such readers generally admire some half-witted thing, who wants to be thought a bold man, having lost the character of a wise one. Him they dignify with the name of poet; his tawdry lampoons are called satires, his turbulence is said to be force, and his frenzy fire.

What reception a Poem may find, which has neither abuse, party, nor blank verse to support it, I cannot tell, nor am I solicitous to know. My aims are right. Without espousing the cause of any party, I have attempted to moderate the rage of all. I have endeavoured to show, that there may be equal happiness in states, that are differently governed from our own; that every state has a particular principle of happiness, and that this principle in each may be carried to a mischievous excess. There are few can judge, better than yourself, how far these positions are illustrated in this Poem.

I am, dear Sir, Your most affectionate Brother, O LIVER G OLDSMITH .

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: ]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/traveller.jpg)

THE TRAVELLER OR A PROSPECT OF SOCIETY

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: ]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/traveller2.jpg)

THE TRAVELLER (R. Westall)

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: Vignette to ‘The Deserted Village’]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/vignette2.jpg)

VIGNETTE TO ‘THE DESERTED VILLAGE’ (Isaac Taylor)

THE DESERTED VILLAGE

DEDICATION TO SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS

D EAR S IR , I can have no expectations in an address of this kind, either to add to your reputation, or to establish my own. You can gain nothing from my admiration, as I am ignorant of that art in which you are said to excel; and I may lose much by the severity of your judgment, as few have a juster taste in poetry than you. Setting interest therefore aside, to which I never paid much attention, I must be indulged at present in following my affections. The only dedication I ever made was to my brother, because I loved him better than most other men. He is since dead. Permit me to inscribe this Poem to you.

How far you may be pleased with the versification and mere mechanical parts of this attempt, I don’t pretend to enquire; but I know you will object (and indeed several of our best and wisest friends concur in the opinion) that the depopulation it deplores is no where to be seen, and the disorders it laments are only to be found in the poet’s own imagination. To this I can scarce make any other answer than that I sincerely believe what I have written; that I have taken all possible pains, in my country excursions, for these four or five years past, to be certain of what I allege; and that all my views and enquiries have led me to believe those miseries real, which I here attempt to display. But this is not the place to enter into an enquiry, whether the country be depopulating or not; the discussion would take up much room, and I should prove myself, at best, an indifferent politician, to tire the reader with a long preface, when I want his unfatigued attention to a long poem.

In regretting the depopulation of the country, I inveigh against the increase of our luxuries; and here also I expect the shout of modern politicians against me. For twenty or thirty years past, it has been the fashion to consider luxury as one of the greatest national advantages; and all the wisdom of antiquity in that particular, as erroneous. Still however, I must remain a professed ancient on that head, and continue to think those luxuries prejudicial to states, by which so many vices are introduced, and so many kingdoms have been undone. Indeed so much has been poured out of late on the other side of the question, that, merely for the sake of novelty and variety, one would sometimes wish to be in the right.

I am, Dear Sir, Your sincere friend, and ardent admirer, O LIVER G OLDSMITH .

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: ]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/village.jpg)

The Water-cress gatherer (John Bewick)

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: ]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/departure.jpg)

THE DEPARTURE (Thomas Bewick)

LYRICAL AND MISCELLANEOUS PIECES

Part of a prologue written and spoken by the poet laberius a roman knight, whom caesar forced upon the stage p reserved by m acrobius., on a beautiful youth struck blind with lightning.

( Imitated from the Spanish. )

TO IRIS, IN BOW STREET, CONVENT GARDEN

THE LOGICIANS REFUTED

IN IMITATION OF DEAN SWIFT

ON THE TAKING OF QUEBEC, AND DEATH OF GENERAL WOLFE

AN ELEGY ON THAT GLORY OF HER SEX, MRS. MARY BLAIZE

Description of an author’s bedchamber, on seeing mrs. ** perform in the character of ****, of the death of the left hon. ***, an epigram addressed to the gentlemen reflected on in the rosciad, a poem, by the author.

Worried with debts and past all hopes of bail, His pen he prostitutes t’ avoid a gaol. R OSCOM.

TO G. C. AND R. L.

Translation of a south american ode, the double transformation a tale, a new simile in the manner of swift.

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: ]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/edwin.jpg)

EDWIN AND ANGELINA (T. Stothard)

EDWIN AND ANGELINA A BALLAD

Elegy on the death of a mad dog, song from ‘the vicar of wakefield’, epilogue to ‘the good natur’d man’, epilogue to ‘the sister’, prologue to ‘zobeide’, threnodia augustalis:.

SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF HER LATE ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCESS DOWAGER OF WALES. OVERTURE—A SOLEMN DIRGE. AIR—TRIO.

MAN SPEAKER.

SONG. BY A MAN—AFFETTUOSO.

WOMAN SPEAKER.

SONG. BY A MAN.—BASSO.—STACCATO.—SPIRITOSO.

SONG. BY A WOMAN.—AMOROSO.

AIR. CHORUS.—POMPOSO.

PART II OVERTURE—PASTORALE MAN SPEAKER.

CHORUS.—AFFETTUOSO.—LARGO.

SONG. BY A WOMAN.

SONG. BY A MAN.—BASSO. SPIRITOSO.

SONG. BY A WOMAN.—PASTORALE.

CHORUS.—ALTRO MODO.

SONG FROM ‘SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER’

Epilogue to ‘she stoops to conquer’.

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: ]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/goldie.jpg)

PORTRAIT OF GOLDSMITH AFTER REYNOLDS (Vignette to ‘Retaliation’)

RETALIATION A POEM

After the Fourth Edition of this Poem was printed, the Publisher received an Epitaph on Mr. Whitefoord, from a friend of the late Doctor Goldsmith, inclosed in a letter, of which the following is an abstract:—

‘I have in my possession a sheet of paper, containing near forty lines in the Doctor’s own hand-writing: there are many scattered, broken verses, on Sir Jos. Reynolds, Counsellor Ridge, Mr. Beauclerk, and Mr. Whitefoord. The Epitaph on the last-mentioned gentleman is the only one that is finished, and therefore I have copied it, that you may add it to the next edition. It is a striking proof of Doctor Goldsmith’s good-nature. I saw this sheet of paper in the Doctor’s room, five or six days before he died; and, as I had got all the other Epitaphs, I asked him if I might take it. “ In truth you may, my Boy ,” (replied he,) “ for it will be of no use to me where I am going. ”’

SONG INTENDED TO HAVE BEEN SUNG IN ‘SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER’

Translation, the haunch of venison a poetical epistle to lord clare, epitaph on thomas parnell, the clown’s reply, epitaph on edward purdon, epilogue for mr. lee lewes, epilogue intended to have been spoken for ‘she stoops to conquer’.

Enter M RS. B ULKLEY , who curtsies very low as beginning to speak. Then enter M ISS C ATLEY , who stands full before her, and curtsies to the audience.

MRS. BULKLEY.

MISS CATLEY.

Recitative.

Air—Cotillon.

Air—A bonny young lad is my Jockey.

MISS CATLEY. Air—Ballinamony.

THE CAPTIVITY

AN ORATORIO

THE PERSONS.

S CENE —The Banks of the River Euphrates, near Babylon.

THE CAPTIVITY ACT I—S CENE I. Israelites sitting on the Banks of the Euphrates. FIRST PROPHET. RECITATIVE.

FIRST PROPHET. AIR.

SECOND PROPHET.

SECOND PROPHET. RECITATIVE.

FIRST PROPHET. RECITATIVE.

Enter C HALDEAN P RIESTS attended. FIRST PRIEST. AIR.

SECOND PRIEST.

A CHALDEAN WOMAN. AIR.

A CHALDEAN ATTENDANT.

FIRST PRIEST.

RECITATIVE.

FIRST PROPHET.

ACT II. Scene as before. CHORUS OF ISRAELITES.

FIRST PRIEST. RECITATIVE.

SECOND PRIEST. AIR.

![name some of the essays of oliver goldsmith [Illustration: ]](https://www.gutenberg.org/images/autograph.jpg)

GOLDSMITH’S AUTOGRAPH (Stanzas from ‘The Captivity’)

ISRAELITISH WOMAN. RECITATIVE.

SECOND PRIEST. RECITATIVE.

CHALDEAN WOMAN. AIR.

CHORUS OF ALL.

ACT III. Scene as before. FIRST PRIEST. RECITATIVE.

ISRAELITISH WOMAN. AIR.

CHORUS OF ISRAELITES.

FIRST AND SECOND PRIEST. AIR.

CHORUS OF YOUTHS.

CHORUS OF VIRGINS.

SEMI-CHORUS.

THE LAST CHORUS.

VERSES IN REPLY TO AN INVITATION TO DINNER AT DR. BAKER’S. ‘This is a poem! This is a copy of verses!’

O LIVER G OLDSMITH .

LETTER IN PROSE AND VERSE TO MRS. BUNBURY

M ADAM , I read your letter with all that allowance which critical candour could require, but after all find so much to object to, and so much to raise my indignation, that I cannot help giving it a serious answer.

I am not so ignorant, Madam, as not to see there are many sarcasms contained in it, and solecisms also. (Solecism is a word that comes from the town of Soleis in Attica, among the Greeks, built by Solon, and applied as we use the word Kidderminster for curtains, from a town also of that name;—but this is learning you have no taste for!)—I say, Madam, there are sarcasms in it, and solecisms also. But not to seem an ill-natured critic, I’ll take leave to quote your own words, and give you my remarks upon them as they occur. You begin as follows:—

‘I hope, my good Doctor, you soon will be here, And your spring-velvet coat very smart will appear, To open our ball the first day of the year.’

Pray, Madam, where did you ever find the epithet ‘good,’ applied to the title of Doctor? Had you called me ‘learned Doctor,’ or ‘grave Doctor,’ or ‘noble Doctor,’ it might be allowable, because they belong to the profession. But, not to cavil at trifles, you talk of my ‘spring-velvet coat,’ and advise me to wear it the first day in the year,—that is, in the middle of winter!—a spring-velvet in the middle of winter!!! That would be a solecism indeed! and yet, to increase the inconsistence, in another part of your letter you call me a beau. Now, on one side or other, you must be wrong. If I am a beau, I can never think of wearing a spring-velvet in winter: and if I am not a beau, why then, that explains itself. But let me go on to your two next strange lines:—

‘And bring with you a wig, that is modish and gay, dance with the girls that are makers of hay.’

The absurdity of making hay at Christmas, you yourself seem sensible of: you say your sister will laugh; and so indeed she well may! The Latins have an expression for a contemptuous sort of laughter, ‘Naso contemnere adunco’; that is, to laugh with a crooked nose. She may laugh at you in the manner of the ancients if she thinks fit. But now I come to the most extraordinary of all extraordinary propositions, which is, to take your and your sister’s advice in playing at loo. The presumption of the offer raises my indignation beyond the bounds of prose; it inspires me at once with verse and resentment. I take advice! and from whom? You shall hear.

There’s the parish of Edmonton offers forty pounds; there’s the parish of St. Leonard, Shoreditch, offers forty pounds; there’s the parish of Tyburn, from the Hog-in-the-Pound to St. Giles’s watchhouse, offers forty pounds,—I shall have all that if I convict them!’—

I challenge you all to answer this: I tell you, you cannot. It cuts deep;—but now for the rest of the letter: and next— but I want room—so I believe I shall battle the rest out at Barton some day next week.

I don’t value you all! O. G.

VIDA’S GAME OF CHESS TRANSLATED

He was born . . . at Pallas. This is the usual account. But it was maintained by the family of the poet’s mother, and has been contended (by Dr. Michael F. Cox in a Lecture on ‘The Country and Kindred of Oliver Goldsmith,’ published in vol. 1, pt. 2, of the Journal of the ‘National Literary Society of Ireland.’ 1900) that his real birth-place was the residence of Mrs. Goldsmith’s parents, Smith-Hill House, Elphin, Roscommon, to which she was in the habit of paying frequent visits. Meanwhile, in 1897, a window was placed to Goldsmith’s memory in Forgney Church, Longford,—the church of which, at the time of his birth, his father was curate.

his academic career was not a success. ‘Oliver Goldsmith is recorded on two occasions as being remarkably diligent at Morning Lecture; again, as cautioned for bad answering at Morning and Greek Lectures; and finally, as put down into the next class for neglect of his studies’ (Dr. Stubbs’s History of the University of Dublin , 1889, p. 201 n.)

a scratched signature upon a window-pane. This, which is now at Trinity College, Dublin, is here reproduced in facsimile. When the garrets of No. 35, Parliament Square, were pulled down in 1837, it was cut out of the window by the last occupant of the rooms, who broke it in the process. (Dr. J. F. Waller in Cassell’s Works of Goldsmith, [1864–5], pp. xiii-xiv n.)

a poor physician. Where he obtained his diploma is not known. It was certainly not at Padua ( Athenaeum , July 21, 1894). At Leyden and Louvain Prior made inquiries but, in each case, without success. The annals of the University of Louvain were, however, destroyed in the revolutionary wars. (Prior, Life , 1837, i, pp. 171, 178).

declared it to be by Goldsmith. Goldsmith’s authorship of this version has now been placed beyond a doubt by the publication in facsimile of his signed receipt to Edward Dilly for third share of ‘my translation,’ such third share amounting to 6 pounds 13s. 4d. The receipt, which belongs to Mr. J. W. Ford of Enfield Old Park, is dated ‘January 11th, 1758.’ ( Memoirs of a Protestant , etc., Dent’s edition, 1895, i, pp. xii-xviii.)

12, Green Arbour Court, Old Bailey. This was a tiny square occupying a site now absorbed by the Holborn Viaduct and Railway Station. No. 12, where Goldsmith lived, was later occupied by Messrs. Smith, Elder & Co. as a printing office. An engraving of the Court forms the frontispiece to the European Magazine for January, 1803.

or some of his imitators. The proximate cause of the Citizen of the World , as the present writer has suggested elsewhere, may have been Horace Walpole’s Letter from XoHo [Soho?], a Chinese Philosopher at London, to his friend Lien Chi, at Peking . This was noticed as ‘in Montesquieu’s manner’ in the May issue of the Monthly Review for 1757, to which Goldsmith was a contributor ( Eighteenth Century Vignettes , first series, second edition, 1897, pp. 108–9).

demonstrable from internal evidence. e.g.—The references to the musical glasses (ch. ix), which were the rage in 1761–2; and to the Auditor (ch. xix) established by Arthur Murphy in June of the latter year. The sale of the ‘Vicar’ is discussed at length in chapter vii of the editor’s Life of Oliver Goldsmith (‘Great Writers’ series), 1888, pp. 110–21.

started with a loss. This, which to some critics has seemed unintelliglble, rests upon the following: ‘The first three editions, . . . resulted in a loss, and the fourth, which was not issued until eight [four?] years after the first, started with a balance against it of £2 16s. 6d., and it was not until that fourth edition had been sold that the balance came out on the right side’ ( A Bookseller of the Last Century [John Newbery] by Charles Welsh, 1885, p. 61). The writer based his statement upon Collins’s ‘Publishing book, account of books printed and shares therein, No. 3, 1770 to 1785.’

James’s Powder. This was a famous patent panacea, invented by Johnson’s Lichfield townsman, Dr. Robert James of the Medicinal Dictionary . It was sold by John Newbery, and had an extraordinary vogue. The King dosed Princess Elizabeth with it; Fielding, Gray, and Cowper all swore by it, and Horace Walpole, who wished to try it upon Mme. du Deffand in extremis , said he should use it if the house were on fire. William Hawes, the Strand apothecary who attended Goldsmith, wrote an interesting Account of the late Dr. Goldsmith’s Illness, so far as relates to the Exhibition of Dr. James’s Powders, etc., 1774, which he dedicated to Reynolds and Burke. To Hawes once belonged the poet’s worn old wooden writing-desk, now in the South Kensington Museum, where are also his favourite chair and cane. Another desk-chair, which had descended from his friend, Edmund Bott, was recently for sale at Sotheby’s (July, 1906).

GREEN ARBOUR COURT, LITTLE OLD BAILEY (as it appeared in 1803)

EDITIONS OF THE POEMS.

No collected edition of Goldsmith’s poetical works appeared until after his death. But, in 1775, W. Griffin, who had published the Essays of ten years earlier, issued a volume entitled The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B., containing all his Essays and Poems . The ‘poems’ however were confined to ‘The Traveller,’ ‘The Deserted Village,’ ‘Edwin and Angelina,’ ‘The Double Transformation,’ ‘A New Simile,’ and ‘Retaliation,’—an obviously imperfect harvesting. In the following year G. Kearsly printed an eighth edition of Retaliation , with which he included ‘The Hermit’ (‘Edwin and Angelina’), ‘The Gift,’ ‘Madam Blaize,’ and the epilogues to The Sister and She stoops to Conquer ;* while to an edition of The Haunch of Venison , also put forth in 1776, he added the ‘Epitaph on Parnell’ and two songs from the oratorio of The Captivity . The next collection appeared in a volume of Poems and Plays published at Dublin in 1777, where it was preceded by a ‘Life,’ written by W. Glover, one of Goldsmith’s ‘Irish clients.’ Then, in 1780, came vol. i of T. Evans’s Poetical and Dramatic Works, etc., now first collected , also having a ‘Memoir,’ and certainly fuller than anything which had gone before. Next followed the long-deferred Miscellaneous Works, etc., of 1801, in four volumes, vol. ii of which comprised the plays and poems. Prefixed to this edition is the important biographical sketch, compiled under the direction of Bishop Percy, and usually described as the Percy Memoir , by which title it is referred to in the ensuing notes. The next memorable edition was that edited for the Aldine Series in 1831, by the Rev. John Mitford. Prior and Wright’s edition in vol. iv of the Miscellaneous Works , etc., of 1837, comes after this; then Bolton Corney’s excellent Poetical Works of 1845; and vol. i of Peter Cunningham’s Works , etc. of 1854. There are other issues of the poems, the latest of which is to be found in vol. ii (1885) of the complete Works , in five volumes, edited for Messrs. George Bell and Sons by J. W. M. Gibbs.

* Some copies of this are dated 1777, and contain The Haunch of Venison and a few minor pieces.

Most of the foregoing editions have been consulted for the following notes; but chiefly those of Mitford, Prior, Bolton Corney, and Cunningham. Many of the illustrations and explanations now supplied will not, however, be found in any of the sources indicated. When an elucidatory or parallel passage is cited, an attempt has been made, as far as possible, to give the credit of it to the first discoverer. Thus, some of the illustrations in Cunningham’s notes are here transferred to Prior, some of Prior’s to Mitford, and so forth. As regards the notes themselves, care has been taken to make them full enough to obviate the necessity, except in rare instances, of further investigation. It is the editor’s experience that references to external authorities are, as a general rule, sign-posts to routes which are seldom travelled.*

* In this connexion may be recalled the dictum of Hume quoted by Dr. Birkbeck Hill:—‘Every book should be as complete as possible within itself, and should never refer for anything material to other books’ ( History of England , 1802, ii. 101).

THE TRAVELLER.

It was on those continental wanderings which occupied Goldsmith between February, 1755 and February, 1756 that he conceived his first idea of this, the earliest of his poems to which he prefixed his name; and he probably had in mind Addison’s Letter from Italy to Lord Halifax , a work in which he found ‘a strain of political thinking that was, at that time [1701]. new in our poetry.’ ( Beauties of English Poesy , 1767, i. III). From the dedicatory letter to his brother—which says expressly, ‘as a part of this Poem was formerly written to you from Switzerland, the whole can now, with propriety, be only inscribed to you’—it is plain that some portion of it must have been actually composed abroad. It was not, however, actually published until the 19th of December, 1764, and the title-page bore the date of 1765.* The publisher was John Newbery, of St. Paul’s Churchyard, and the price of the book, a quarto of 30 pages, was 1s. 6d. A second, third and fourth edition quickly followed, and a ninth, from which it is here reprinted, was issued in 1774, the year of the author’s death. Between the first and the sixth edition of 1770 there were numerous alterations, the more important of which are indicated in the ensuing notes.

* This is the generally recognized first edition. But the late Mr. Frederick Locker Lampson, the poet and collector, possessed a quarto copy, dated 1764, which had no author’s name, and in which the dedication ran as follows:—‘This poem is inscribed to the Rev. Henry Goldsmith, M.A. By his most affectionate Brother Oliver Goldsmith.’ It was, in all probability, unique, though it is alleged that there are octavo copies which present similar characteristics. It has now gone to America with the Rowfant Library. In 1902 an interesting discovery was made by Mr. Bertram Dobell, to whom the public are indebted for so many important literary ‘finds.’ In a parcel of pamphlets he came upon a number of loose printed leaves entitled A Prospect of Society . They obviously belonged to The Traveller ; but seemed to be its ‘formless unarranged material,’ and contained many variations from the text of the first edition. Mr. Dobell’s impression was that ‘the author’s manuscript, written on loose leaves, had fallen into confusion, and was then printed without any attempt at re-arrangement.’ This was near the mark; but the complete solution of the riddle was furnished by Mr. Quiller Couch in an article in the Daily News for March 31, 1902, since recast in his charming volume From a Cornish Window , 1906, pp. 86–92. He showed conclusively that The Prospect was ‘merely an early draft of The Traveller printed backwards in fairly regular sections.’ What had manifestly happened was this. Goldsmith, turning over each page as written, had laid it on the top of the preceding page of MS. and forgotten to rearrange them when done. Thus the series of pages were reversed; and, so reversed, were set up in type by a matter-of-fact compositor. Mr. Dobell at once accepted this happy explanation; which—as Mr. Quiller Couch points out—has the advantage of being a ‘blunder just so natural to Goldsmith as to be almost postulable.’ One or two of the variations of Mr. Dobell’s ‘find’—variations, it should be added, antecedent to the first edition—are noted in their places.

The didactic purpose of The Traveller is defined in the concluding paragraph of the Dedication ; and, like many of the thoughts which it contains, had been anticipated in a passage of The Citizen of the World , 1762, i. 185:—‘Every mind seems capable of entertaining a certain quantity of happiness, which no institutions can encrease, no circumstances alter, and entirely independent on fortune.’ But the best short description of the poem is Macaulay’s:—‘In the Traveller the execution, though deserving of much praise, is far inferior to the design. No philosophical poem, ancient or modern, has a plan so noble, and at the same time so simple. An English wanderer, seated on a crag among the Alps, near the point where three great countries meet, looks down on the boundless prospect, reviews his long pilgrimage, recalls the varieties of scenery, of climate, of government, of religion, of national character, which he has observed, and comes to the conclusion, just or unjust, that our happiness depends little on political institutions, and much on the temper and regulation of our own minds.’ ( Encyclop. Britannica , Goldsmith, February, 1856.)

The only definite record of payment for The Traveller is ‘Copy of the Traveller, a Poem, 21 l ,’ in Newbery’s MSS.; but as the same sum occurs in Memoranda of much later date than 1764, it is possible that the success of the book may have prompted some supplementary fee.

A Prospect , i.e. ‘a view.’ ‘I went to Putney, and other places on the Thames, to take ‘prospects’ in crayon, to carry into France, where I thought to have them engraved’ (Evelyn, Diary , 20th June, 1649). And Reynolds uses the word of Claude in his Fourth Discourse:—‘His pictures are a composition of the various draughts which he had previously made from various beautiful scenes and prospects’ ( Works , by Malone, 1798, i. 105). The word is common on old prints, e.g. An Exact Prospect of the Magnificent Stone Bridge at Westminster , etc., 1751.

Dedication. The Rev. Henry Goldsmith, says the Percy Memoir , 1801, p. 3, ‘had distinguished himself both at school and at college, but he unfortunately married at the early age of nineteen; which confined him to a Curacy, and prevented his rising to preferment in the church.’

with an income of forty pounds a year. Cf. The Deserted Village , ll. 141–2:—

A man he was, to all the country dear, And passing rich with forty pounds a year .

Cf. also Parson Adams in ch. iii of Joseph Andrews , who has twenty-three; and Mr. Rivers, in the Spiritual Quixote , 1772:—‘I do not choose to go into orders to be a curate all my life-time, and work for about fifteen-pence a day, or twenty-five pounds a year’ (bk. vi, ch. xvii). Dr. Primrose’s stipend is thirty-five in the first instance, fifteen in the second ( Vicar of Wakefield , chapters ii and iii). But Professor Hales ( Longer English Poems , 1885, p. 351) supplies an exact parallel in the case of Churchill, who, he says, when a curate at Rainham, ‘prayed and starved on forty pounds a year .’ The latter words are Churchill’s own, and sound like a quotation; but he was dead long before The Deserted Village appeared in 1770. There is an interesting paper in the Gentleman’s Magazine for November, 1763, on the miseries and hardships of the ‘inferior clergy.’

But of all kinds of ambition, etc. In the first edition of 1765, p. ii, this passage was as follows:—‘But of all kinds of ambition, as things are now circumstanced, perhaps that which pursues poetical fame, is the wildest. What from the encreased refinement of the times, from the diversity of judgments produced by opposing systems of criticism, and from the more prevalent divisions of opinion influenced by party, the strongest and happiest efforts can expect to please but in a very narrow circle. Though the poet were as sure of his aim as the imperial archer of antiquity, who boasted that he never missed the heart; yet would many of his shafts now fly at random, for the heart is too often in the wrong place.’ In the second edition it was curtailed; in the sixth it took its final form.

they engross all that favour once shown to her. First version—‘They engross all favour to themselves.’

the elder’s birthright. Cunningham here aptly compares Dryden’s epistle To Sir Godfrey Kneller , II. 89–92:—

Our arts are sisters, though not twins in birth; For hymns were sung in Eden’s happy earth: But oh, the painter muse, though last in place, Has seized the blessing first, like Jacob’s race.

Party =faction. Cf. lines 31–2 on Edmund Burke in Retaliation :—

Who, born for the Universe, narrow’d his mind, And to party gave up what was meant for mankind.

Such readers generally admire, etc. ‘I suppose this paragraph to be directed against Paul Whitehead, or Churchill,’ writes Mitford. It was clearly aimed at Churchill, since Prior ( Life , 1837, ii. 54) quotes a portion of a contemporary article in the St. James’s Chronicle for February 7–9, 1765, attributed to Bonnell Thornton, which leaves little room for doubt upon the question. ‘The latter part of this paragraph,’ says the writer, referring to the passage now annotated, ‘we cannot help considering as a reflection on the memory of the late Mr. Churchill, whose talents as a poet were so greatly and so deservedly admired, that during his short reign, his merit in great measure eclipsed that of others; and we think it no mean acknowledgment of the excellencies of this poem [ The Traveller ] to say that, like the stars, they appear the more brilliant now that the sun of our poetry is gone down.’ Churchill died on the 4th of November, 1764, some weeks before the publication of The Traveller . His powers, it may be, were misdirected and misapplied; but his rough vigour and his manly verse deserved a better fate at Goldsmith’s hands.

tawdry was added in the sixth edition of 1770.

blank verse. Cf. The Present State of Polite Learning , 1759, p. 150—‘From a desire in the critic of grafting the spirit of ancient languages upon the English, has proceeded of late several disagreeable instances of pedantry. Among the number, I think we may reckon blank verse . Nothing but the greatest sublimity of subject can render such a measure pleasing; however, we now see it used on the most trivial occasions’—by which last remark Goldsmith probably, as Cunningham thinks, intended to refer to the efforts of Akenside, Dyer, and Armstrong. His views upon blank verse were shared by Johnson and Gray. At the date of the present dedication, the latest offender in this way had been Goldsmith’s old colleague on The Monthly Review , Dr. James Grainger, author of The Sugar Cane , which was published in June, 1764. (Cf. also The Bee for 24th November, 1759, ‘An account of the Augustan Age of England.’)

and that this principle, etc. In the first edition this read—‘and that this principle in each state, and in our own in particular, may be carried to a mischievous excess.’

Remote, unfriended, melancholy, slow. Mitford (Aldine edition, 1831, p. 7) compares the following lines from Ovid:—

Solus, inops, exspes, leto poenaeque relictus. Metamorphoses , xiv. 217. Exsul, inops erres, alienaque limina lustres, etc. Ibis . 113.

slow. A well-known passage from Boswell must here be reproduced:—‘Chamier once asked him [Goldsmith], what he meant by slow , the last word in the first line of The Traveller ,

Remote, unfriended, melancholy, slow.

Did he mean tardiness of locomotion? Goldsmith, who would say something without consideration, answered “yes.” I [Johnson] was sitting by, and said, “No, Sir, you do not mean tardiness of locomotion; you mean, that sluggishness of mind which comes upon a man in solitude.” Chamier believed then that I had written the line as much as if he had seen me write it.’ [Birkbeck Hill’s Boswell , 1887, iii. 252–3.) It is quite possible, however, that Goldsmith meant no more than he said.

the rude Carinthian boor. ‘Carinthia,’ says Cunningham, ‘was visited by Goldsmith in 1755, and still (1853) retains its character for inhospitality.’

Campania. ‘Intended,’ says Bolton Corney, ‘to denote La campagna di Roma . The portion of it which extends from Rome to Terracina is scarcely habitable.’

a lengthening chain. Prior compares Letter iii of The Citizen of the World , 1762, i. 5:—‘The farther I travel I feel the pain of separation with stronger force, those ties that bind me to my native country, and you, are still unbroken. By every remove, I only drag a greater length of chain.’ But, as Mitford points out, Cibber has a similar thought in his Comical Lovers , 1707, Act v:—‘When I am with Florimel, it [my heart] is still your prisoner, it only draws a longer chain after it .’ And earlier still in Dryden’s ‘All for Love’, 1678, Act ii, Sc. 1:—

My life on’t, he still drags a chain along, That needs must clog his flight.

with simple plenty crown’d. In the first edition this read ‘where mirth and peace abound.’

the luxury of doing good. Prior compares Garth’s Claremont , 1715, where he speaks of the Druids:—

Hard was their Lodging, homely was their Food, For all their Luxury was doing Good .

my prime of life. He was seven-and-twenty when he landed at Dover in February, 1756.