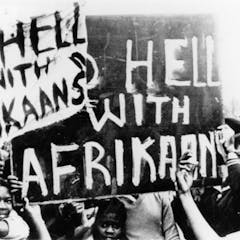

'My activism started then': the Soweto uprising remembered

From students and activists to reporters and photographers, Guardian readers remember the brutal events of the 16 June 1976

F or many South Africans looking back on the events of 16 June 1976, when police brutally attacked thousands of protesting school children , the day marked the beginning of the end of the apartheid system.

The uprising began as students came together against a decree that all pupils must learn Afrikaans in school. As historian Julian Brown, the author of a new study, The Road to Soweto , says: “These crowds were not coordinated by any national political body. They were the product of local tensions. They constituted new efforts to remake South Africa’s democracy from the ground up.”

To commemorate 40 years since the uprising and the violence against peaceful protesters that followed, we asked Guardian readers to share their memories with us. From protesters to reporters to radical teachers, we heard from an array of people who were there that day, and shared moving accounts with us. Alongside them, we are also publishing the accounts of survivors .

I had no idea what was going on. I was a young student and did not understand politics. I followed older students I knew and we all began marching towards town. Immediately after reaching Vincent Road we were met by police who arrived in large ‘hippos’ [armoured vehicles] and began firing live ammunition and tear gas. Gloria Moletse, Tiyang Primary, Meadowlands

The protester

My name is Phumla Williams I was born in Pimville, Soweto. I was brought up by a single parent who worked as a domestic worker, and I later became an assistant nurse in a clinic in Soweto.

In June 1976, I was 16 years old and a student in Musi High School. On the 16th, when the student uprising started in Orlando, our school was still having normal classes. In fact, on that day, I was writing my half-yearly test of the Afrikaans paper.

The students crossed Soweto and protested over night. On the 17 June, Musi High students joined the protest. My activism started then.

I came to realise that African children’s education was designed to be inferior to the other races in South Africa , and that the conditions under which I was being schooled were unlikely to change unless I took action.

One of the sad memories that still lingers with me was one my schoolmates who was shot and killed. She was one of those who did not participate in the protest, but a stray bullet hit her whilst she was sweeping the yard at her home. This was the madness of the system we were dealing at time.

After the events in Soweto, my activism led me to leave the country in 1978 to join the exiled African National Congress (ANC) in Swaziland. My political consciousness had developed to a level of appreciating that the apartheid system in the country was responsible for the inequalities in our society.

What is recently pleasing is the level of constructive activism by the students that we saw in universities . But a lot still needs to be done. Education remains the pillar to a better life. Three-hundred years of subjugation can never be undone in 40 years. Generations to come need to stay on the cause.

When the shooting began, I went into hiding. When the shooting stopped, I came out of hiding when others came out. I saw [my brother] Hector [Pieterson] across the street, and I called him and waved at him. He came over and I spoke to him, but more shots rang out and I went into hiding again. I thought he followed me, but he did not come. I came out again and waited at the spot where I just saw him. He did not come. When Mbuyiso came past me a group of children were gathering nearby. He walked towards the group and picked up a body ... And then I saw Hector’s shoes. Antoinette Sithole, Tshesele High School

The reporter

Tony Kleu, now 67 and living in Sydney, was a white journalist in his mid-20s working at the Rand Daily Mail in 1976. He recalled the atmosphere in the build up to events on 16 June, as well as his vivid memories of despair and anguish as news filtered in. He says theirs was an unusual newsroom at the time in that he had many black colleagues, and though the staff did include “a few openly pro-government people and several suspected informers, the vast majority of us were sympathetic to black aspirations and despised the government.”

“We had known there was growing unrest and that students planned to march,” he said, “but I don’t believe anyone had anticipated the scale of the protest or the reaction on the 16 June. I don’t think there was expectation of high drama, but the reaction when we first heard thousands had joined the march (quite late in the morning I think) and that police had attempted to block them was alarm and disbelief.

“We were alarmed because we knew damn well what had happened at Sharpeville, 16 years earlier , and we feared what might happen if the heavily armed police, renowned for their brutality, lost control. For several hours there was confusion about the scale of the clashes. Palls of smoke could be seen over Soweto, but communication was compromised, roads in and out had been blocked and we were wary of reports from police.”

It wasn’t until first-hand accounts from reporters came in that the scale of the brutality would become clear.

“The first report of a fatality came from the police, who announced that rioters, unprovoked, had killed white civilians, but we would soon receive evidence the death toll far exceeded the government’s early claims only a handful of black people had been killed,” says Kleu.

“We heard how one of our photographers, I think it was Alf Kumalo , hid behind garbage bins risking his life to snap images while trigger happy police drove past. I remember the sense of dread in the air and intense concern everyone in the newsroom felt – it seemed the country had finally tipped over the edge and into barbarism.”

Kleu says he felt a clear need to “convey the full drama”, that “whatever the truth, it should be recorded.”

“The most appalling memory I have is one of our black reporters telling us how he saw bodies thrown into a van like sacks of potatoes. That image will always remain with me.

“I doubt any of us, that night, recognised the day’s events as the beginning of a revolution,” he adds. “Those kids were astonishingly proud and brave. I feel they became the catalyst that mobilised the masses after a decade of ineffectual activism. They deserve to be remembered.”

The historians

Ismail Farouk was a young researcher at the Hector Pieterson Museum in Soweto in 2005 when he was commissioned to investigate alternative narratives of the 16 June uprising.

“The museum itself is limited, and has a strong African National Congress political bias, and arguably, a very masculine focus,” he says. “I was interested in whose stories get told and why, and wanted to find a multiplicity of voices to better reflect the events of that day.”

After 1976, there was little information in the public domain about the events: “It was hushed up.”

Searching for ways to present the various voices and memories he had collected during extensive interviews, Farouk met Babak Fakhamzadeh, a mobile developer, and they started working on an open, accessible way to present the data.

“[Already in 2005] these people were getting older, and they had subjective views. We asked ourselves: how do we collect all of these and allow for all the discrepancies in the stories. There isn’t one official narrative,” Fakhamzadeh explains.

Back then, Google Maps was in its infancy and the two decided to sketch out the various routes of the protestors, allowing users to add to it and make changes. The result was www.sowetouprisings.com .

It’s a dynamic narrative of the events of that day. “The popular imagination of the uprisings is one of a chaotic, crazy day where the students were violent and disorganised,” Farouk explains. “But if you look at the different routes, there was a clear goal.”

Looking back on the project more than 10 years later, the two admit that although the technology now feels a little rudimentary, the spirit of the project remains: “Our core goal was to represent a different view of what happened that day.”

It was so rough that day I still remember and the police came and we were so small and running everywhere trying to hide ourselves. We had to run for safety and ran into neighbouring houses. There was lots of smoke and lots of children – it was chaos. Maki Lekaba, Teyang Primary, Meadowlands

The teacher

In 1976 Richard Welch was a young teacher riding his Vespa scooter to work when he saw the newspaper hoardings reporting the uprising. “A feeling of exhilaration came over me,” he recalls. “I thought: ‘This is it. Nothing will be the same again’.”

After the brutal events of that day, Welch became involved in an alternative education project for the young students who had rejected Bantu Education, a system designed to keep them in subjection.

“The events of 1976 generated a popular culture of resistance to Bantu education and apartheid which spread from the highly politicised township students into almost every sphere of South African life,” Welch remembers.

The initiative for the education project came from the Witwatersrand Council of Churches, under Simeon Nkoane, the Anglican Dean of Johannesburg. It was established as a church initiative, because Nkoane believed “the security police would be less likely to threaten an initiative ... if it was based in the suburban (mainly white) churches and manned and supported by concerned white teachers, students, and other folk,” Welch says.

“In those days the average black high school student had many obstacles to overcome in his or her school career, so our students ranged in age from about 20 years old to 25 years old, some even older. The project ran for 21 years, from 1978 to 1999, and it began with approximately 200 students. All in all, it probably catered for 150 to 250 students per year.”

Welch’s classes covered basic lessons such as maths, science, english and biology, but offered other options too.

“Twice a week, on Thursdays and Saturdays, students participated in the so-called Enrichment Programme, later known as the Cultural Programme which involved activities promoting theory of music, fine arts, drama, modern dance, modern african literature and history, contemporary urban life, and study skills.”

Looking back, Welch realises the radical nature of what he and so many others were doing. “It was ‘clandestine’ in the sense that we had continually to be on our guard, take care what was said in the phone, or to whom one said it. The organisers and students, and some tutors at least were often in danger of arrest. We never spoke publicly about what we were doing, or sought any kind of public profile.”

Additional photography: James Oatway for the Guardian and Sowetouprisings.com archive

This article was amended on 28 June 2016 to remove the word “young” from Tony Kleu’s account of what his reporters told him they saw. It was introduced due to an editing error.

- Guardian Africa network

- South Africa

- ANC (African National Congress)

- Nelson Mandela

Most viewed

- Social Justice , Winter 2020

Then and now: The legacy of Bantu education in South Africa

- April 1, 2020

By Briana Garrett Medill Reports

For most of the twentieth century, South Africa functioned under the system of apartheid, a system that segregated South African peoples in every aspect of life, privileging whiteness above all. Through a series of laws, apartheid created deep economic disparities, immense political disenfranchisement and social divides with rippling effects across generations.

Under apartheid, Bantu education was law permitting the use of race to dictate the quality of the curriculum and resources. Segregation was cemented in the education system and modern public education still grapples with rectifying its past. In an audio piece that explores the past and present of public education in South Africa, South African leaders in education lend their voices to narrate the future thereof.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/787150321″ params=”color=#ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”300″ iframe=”true” /]

Photo at top: Students gather after classes at City Deep Adult Learning Center (Briana Garrett/MEDILL)

© 2023 Northwestern University

MEDILL SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM, MEDIA, INTEGRATED MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS 1845 Sheridan Road Evanston, IL 60208-2101

Articles on Bantu Education

Displaying all articles.

What happened to Nelson Mandela’s South Africa? A new podcast series marks 30 years of post-apartheid democracy

Thabo Leshilo , The Conversation

Jonas Gwangwa embodied South Africa’s struggle for a national culture

Gwen Ansell , University of Pretoria

How Masisi outsmarted Khama to take the reins in Botswana

Barry Morton , Indiana University

Khanya College: a South African story of decolonisation

Hanne Kirstine Adriansen , Aarhus University ; Lene Møller Madsen , University of Copenhagen , and Rajani Naidoo , University of Bath

Strategic lessons South Africa’s students can learn from the leaders of 1976

Anne Heffernan , University of the Witwatersrand

Related Topics

- African Jazz

- African National Congress (ANC)

- Cry Freedom

- Peacebuilding

- South Africa

Scheduling Analyst

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Top contributors.

Associate of the Gordon Institute for Business Science, University of Pretoria

Professor and Director, International Centre for Higher Education Management, School of Management, University of Bath

Assistant Professor in the history of Southern Africa, Durham University

Associate Professor, School of Education, Aarhus University

Associate professor in Science Education, University of Copenhagen

Research Fellow, African Studies, Indiana University

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Announcements

- About AOSIS

New Contree

- Editorial Team

- Submission Procedures

- Submission Guidelines

- Submit and Track Manuscript

- Publication fees

- Make a payment

- Journal Information

- Journal Policies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Article RSS

- Support Enquiry (Login required)

- Aosis Newsletter

Open Journal Systems

Original research, segregated schools of thought: the bantu education act (1953) revisited, about the author(s).

Various political parties, civil rights groups and columnists support the view that one of South Africa’s foremost socio-economic challenges is overcoming the scarring legacy which the Bantu Education Act of 1953 left on the face of the country. In light of this challenge, a need arose to revisit the position and place of Bantu Education historiography in the current contested interpretation of its legacy.

It is apparent from the plethora of literature available on this topic that academics are not in agreement about whether or not the passing of the 1953 Act was a watershed moment in marginalising education for black pupils. On the one hand, it would seem that the general consensus is that the 1953 Act was indeed a turning point in the formalisation of education reserved for pupils of colour – thus a largely “traditional” view. On the other hand, the Marxist school, as coined by P Christie and C Collins, argues that securing a cheap, unskilled labour force was already on the agenda of the white electorate preceding the formalisation of the Act.

The aim of this article is two-fold. Firstly, to contextualise these two stances historically; and secondly and more chiefly, to examine the varying approaches regarding the rationalisation behind Bantu Education by testing these approaches against the rationale apparent in primary sources in the form of parliamentary debates and contemporary newspaper articles.

Crossref Citations

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get specific, domain-collection newsletters detailing the latest CPD courses, scholarly research and call-for-papers in your field.

New Contree | ISSN: 0379-9867 (PRINT) | ISSN: 2959-510X (ONLINE)

ISSN: 2959-510X

Fisher Digital Publications

Home > The Review > Vol. 2 (1999)

Article Title

Bantu Education

Andrew Phillips , St. John Fisher University Follow

Disciplines

African History | Education | Race and Ethnicity

In lieu of an abstract, below is the essay's first paragraph. South Africa has had to deal with issues of racial differences since colonial times. British settlers came into this foreign country and claimed it as their own. Until recently, these settlers were able to treat the black people of South Africa as a subservient and inferior race as a result of the system of apartheid. Many different strategies were needed to keep this imbalanced system in place. One such strategy was employed through education, or a lack thereof. As long as blacks received a lower quality education than whites, they could not hope to become the political or social equals of whites.

Recommended Citation

Phillips, Andrew. "Bantu Education." The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research 2 (1999): 22-27. Web. [date of access]. <https://fisherpub.sjf.edu/ur/vol2/iss1/6>.

Additional Files

Since July 01, 2013

Included in

African History Commons , Education Commons , Race and Ethnicity Commons

- Journal Home

- About this Journal

- Most Popular Papers

- Receive Email Notices or RSS

Advanced Search

Home | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

NYU Launches Its Center for the Study of Antisemitism

At a moment when antisemitism is on the rise, NYU faculty, graduate students, and scholars from other universities grappled with the historical origins and widespread impact of this particular form of hate, examined its connection to other forms of bigotry, and analyzed the resulting harm to American democracy and societies around the world.

NYU’s Center for the Study of Antisemitism, announced last fall, presented its inaugural academic conference, “Four Critical Questions: Confronting Antisemitism in 2024 and Beyond,” on April 18 in the John A. Paulson Center’s African Grove Theatre. With more than 120 in attendance—including university leadership, supporters, and community partners—the conference employed a multidisciplinary lens to examine the age-old hate and its role in our current global crisis.

Calling for critical inquiry founded in precision, empathy, and courage, NYU President Linda G. Mills opened the day-long event by emphasizing NYU’s decision to harness its unique academic strength.

“The creation of the Center for the Study of Antisemitism comes in part out of the renewed wave of Jewish hatred we have seen in the past several months. There is a clear need for knowledge and further study,” Mills said. “Today we have assembled several brilliant scholars from NYU and beyond to use the tools we at a university know best: systemic and scholarly review.”

The conference came the day after a second Congressional hearing on higher education’s handling of antisemitism and the challenges facing universities in the wake of the Oct. 7 attack on Israel by Hamas. The hearing was the latest to highlight the ongoing debate about how to weigh the protection of academic freedom with concerns about discrimination and student safety.

Avinoam Patt, the inaugural director of the Center for the Study of Antisemitism, welcomes participants to the April 18 conference. ©Hollenshead: Courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau

The groundbreaking center was created in November to meet this difficult moment. It will convene scholars and students from diverse disciplines—including the arts, humanities, social sciences, Judaic Studies, history, social work, public policy, psychology, law, sociology, media studies, management, and public health—to address the historical roots of antisemitism, its contemporary manifestations, and the most effective ways to combat it.

Presented in four parts, “Four Critical Questions” began with “Historical Perspectives,” probing how Oct. 7 and the resulting surge in global antisemitism could be understood within Jewish history. With Benjamin Hary, director of NYU Tel Aviv, moderating, Lihi Ben-Shitrit, Henry Taub Professor of Israel Studies and director of the Taub Center for Israel Studies in Arts & Science, examined antisemitic attitudes across the political spectrum and how conflict in Israel contributes to anti-Jewish violence. Elisha Russ Fishbane, associate professor in the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, explored the roots of anti-Judaism and antisemitism in the Muslim world, while Lawrence Schiffman, Global Distinguished Professor in the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, traced the history of Jewish-Christian relations.

Eric Ward, executive vice president of Race Forward and senior fellow at the Southern Poverty Law Center, examined the connection between antisemitism and racism and other forms of hatred. In a keynote that was both personal and political, Ward described antisemitism as the “theoretical core” of the White Nationalist movement and charted its movement from the margins to the center of American society.

Eric Ward gave the conference keynote address. ©Hollenshead: Courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau

“It imperils us all. Because it doesn’t look like anti-Black racism, we may think it is not a big deal. But I believe it is one of the biggest deals. Antisemitism is an effective conspiracy theory that dehumanizes us all. It distorts our understanding of how the world actually works. It isolates us. It kills, but it also kills American democracy,” said Ward, who drew parallels to the Civil Rights Movement in outlining the importance of combating prejudice.

Most significantly, Ward explained why antisemitism is a threat to all civil society and not just to Jews.

“Antisemitism isn’t just bigotry toward the Jewish community. It is, more accurately, utilizing bigotry toward the Jewish community and those seen as proximate to it to deconstruct 60 years of Black Civil Rights struggle,” he continued. “It does so by framing democracy as ineffective and a conspiracy rather than a tool of empowerment or a functional tool of governance.”

To start the afternoon session, President Mills presented a Proclamation in Honor of Richard Courant , the late NYU mathematics professor who joined NYU in 1933 after losing his position in Germany because he was Jewish. Not only a noted mathematician, whose name graces the university’s institute of mathematics, Courant was a lifeline for others escaping Nazi Germany, Mills explained.

The next panel focused on the role of education in confronting antisemitism. Daniel Greene, a curator and subject expert at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., described how the museum pushes visitors to tackle difficult questions and contradictions.

“We are a nation of immigrants and we are also a nation that has closed its doors to immigrants,” he said, citing one example of the tensions highlighted in the museum’s exhibitions.

Batia Wiesenfeld, a professor and director of the Business & Society Program at the Stern School of Business, asks a question. ©Hollenshead: Courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau

Azedeh Aalai, associate professor of psychology at Queensborough Community College, and adjunct professor at NYU, discussed how studying the Holocaust exercises students’ critical thinking skills, improves their emotional literacy, and makes them less susceptible to antisemitism. Difficult conversations around questions that may not have answers are opportunities for transformational learning, she said. Sara Fredman Aeder, director of Israel and Jewish Affairs at the Jewish Community Relations Council of New York, presented findings of her research on Jewish student belonging and the distinctions between students’ experiences of antisemitism and their perceptions of safety.

Renowned Jewish historian David Engel, professor emeritus of NYU's Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, gave the day’s final lecture, which examined the past, present, and future of Antisemitism Studies. Engel traced the meaning of the word from its debut in 1879 to the current day, arguing that its many meanings have prevented serious academic research on the varied forms of anti-Jewish persecution over time. Rather than focus on its definition, Engel encouraged research that empirically studies specific types of discrimination and responses to them. He also encouraged the center to tap NYU’s strengths in data science and its global centers to create a framework for future research.

Avinoam Patt, Maurice Greenberg Professor of Holocaust Studies and the inaugural director of the center, concluded the event by thanking the presenters and participants for their thoughtful contributions.

“We know that right now we are living in a turning point in history…when resources are properly being invested in the critical study of this topic, but also, hopefully, in the study of a broader examination of hate in a radical time of profound social, economic, and political crisis,” he said. “I’m under no illusions that the launch of our center will solve the problem of antisemitism, but we know that we can begin to ask serious questions and begin to do the research that will help move our field forward.”

- Education News

CBSE Board Results 2024: Notification for verification of marks, re-evaluation of answer sheets released at cbse.gov.in

Visual Stories

A banner of a Colombian-born American missing woman Ana Maria Knezevich Henao, 40, is displayed on a streetlight in Madrid, Spain, Feb. 16, 2024. The estranged husband of the woman who disappeared three months ago in Spain has been charged by U.S. federal agents with her kidnapping. U.S. marshals arrested David Knezevich at Miami International Airport on Saturday, May 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Manu Fernandez, file)

- Copy Link copied

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. (AP) — The estranged husband of a Florida woman who disappeared three months ago in Spain has been charged by U.S. federal agents with her kidnapping.

The FBI and other federal agents arrested David Knezevich at Miami International Airport on Saturday. The Fort Lauderdale resident is charged in connection with the Feb. 2 disappearance of his 40-year-old wife, Ana Knezevich, from the Madrid apartment where she had been staying since shortly after their separation last year.

David Knezevich, a 36-year-old business owner originally from Serbia, briefly appeared in Miami federal court Monday and will have a bond hearing Friday.

“The Spanish National Police, Customs and Border Protection, the Diplomatic Security Service, and the FBI continue their investigation. Because this is an ongoing investigation, no further information will be released,” the FBI said in a statement.

Knezevich’s attorney, Ken Padowitz, did not return a call Monday afternoon seeking comment. Padowitz has previously denied his client had anything to do with his wife’s disappearance.

Ana Knezevich, a naturalized American originally from Colombia, vanished shortly after a man wearing a motorcycle helmet disabled her apartment complex’s security cameras by spray-painting the lenses.

A friend, Sanna Rameau, and another woman received text messages from Ana Knezevich’s phone the next day saying she was running off for a few days with a man she had just met. Rameau said the messages were not written in Ana’s style and she would never leave with a stranger.

“I am happy that there has been an arrest,” Rameau said Monday. “We are hoping that this next chapter will bring justice and find answers about what has happened to Ana.”

The Knezeviches, who sometimes spell their surname “Knezevic,” have been married for 13 years. They own EOX Technology Solutions Inc., which does computer support for South Florida businesses. Records show they also own a home and two other Fort Lauderdale properties, one of those currently under foreclosure.

Ana’s brother, Juan Henao, called the divorce “nasty” in an interview with a Fort Lauderdale detective, a report shows. He told police David was angry that they would be dividing a substantial amount of money.

Padowitz, in a February interview, denied that the divorce was contentious and said his client was cooperating with police. He said his client was in Serbia when his wife disappeared.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In 1954—5 black teachers and students protested against Bantu Education. The African Education Movement was formed to provide alternative education. For a few years, cultural clubs operated as informal schools, but by 1960 they had closed down. The Extension of University Education Act, Act 45 of 1959, put an end to black students attending ...

On the 16th, when the student uprising started in Orlando, our school was still having normal classes. In fact, on that day, I was writing my half-yearly test of the Afrikaans paper. The students ...

The June 16 1976 Uprising that began in Soweto and spread countrywide profoundly changed the socio-political landscape in South Africa. Events that triggered the uprising can be traced back to policies of the Apartheid government that resulted in the introduction of the Bantu Education Act in 1953. The rise of the Black Consciousness Movement ...

Bantu education in a post-apartheid era. One of the legacies of apartheid that continues to haunt the black people of South Africa is the legacy of the Bantu Education system. This education system, which was implemented to oppress black people by means of providing the Bantu schools with little to almost no funding at all, although indirectly ...

Brembeck Cole S. and Keith John P. Education in Emerging Africa: A Select and Annotated Bibliography. East Lansing, Michigan: College of Education, Michigan State University, 1966. 3. Catalogue of the Collection of Education in Tropical Areas of the Institute of Education, University of London. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1967. (3 volumes) 4.

Under apartheid, Bantu education was law permitting the use of race to dictate the quality of the curriculum and resources. Segregation was cemented in the education system and modern public education still grapples with rectifying its past. In an audio piece that explores the past and present of public education in South Africa, South African ...

This article illustrates the transition from Bantu Education to social justice education in South Africa. I argue that education reform in post-apartheid South Africa has made important changes during this transition, although inequalities persist. Large disparities in resources between black township (still segregated) and formerly white (now ...

Bantu Education Act, South African law, enacted in 1953 and in effect from January 1, 1954, that governed the education of Black South African (called Bantu by the country's government) children. It was part of the government's system of apartheid, which sanctioned racial segregation and discrimination against nonwhites in the country.. From about the 1930s the vast majority of schools ...

Browse Bantu Education news, ... Articles on Bantu Education. Displaying all articles. ... Associate professor in Science Education, University of Copenhagen

Bantu Education respectively and to test these against the rationale apparent in the architects of the Bantu Education system, in the form of Hansards and contemporary newspaper articles. In order to contextualise the historical interpretations, the so-called Marxist school of

Bantu Education, and Its Living Educational and Socioeconomic Legacy in Apartheid and Post-Apartheid South Africa ... News articles from South African news sites providing up-to-date information on current events in South Africa are also included in this thesis. While secondary and scholarly sources

A NOTE ON BANTU EDUCATION, 1953 TO 1970. Hermann Giliomee, Hermann Giliomee. University of Stellenbosch. Search for more papers by this author. Hermann Giliomee, Hermann Giliomee. University of Stellenbosch. Search for more papers by this author. First published: 31 March 2009.

Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) caught the world education systems by surprise and inflicted a deep-felt disruption in the previously disadvantaged black schools in South Africa.

108 Segregated schools of thought: ffie Bantu Education Act, New Contree, 79, December 2017, pp. 106-126 trousers".4 More insight into the American missionaries' approach is provided in DJ Kotze's Letters of the American missionaries, 1835-1838.One such example is illustrated by the missionaries, BB Wisner, R Anderson and D

Abstract. Various political parties, civil rights groups and columnists support the view that one of South Africa's foremost socio-economic challenges is overcoming the scarring legacy which the Bantu Education Act of 1953 left on the face of the country. In light of this challenge, a need arose to revisit the position and place of Bantu ...

Nadine Moore. University of Pr etoria. [email protected]. Abstract. V arious political parties, civil rights groups and columnists support the view. that one of South Africa 's for emost ...

The Bantu Education Act 1953 (Act No. 47 of 1953; later renamed the Black Education Act, 1953) was a South African segregation law that legislated for several aspects of the apartheid system. Its major provision enforced racially-separated educational facilities; [1] Even universities were made "tribal", and all but three missionary schools ...

A NOTE ON BANTU EDUCATION, 1953 TO 1970. Hermann Giliomee, Hermann Giliomee. University of Stellenbosch. Search for more papers by this author. Hermann Giliomee, ... View the article/chapter PDF and any associated supplements and figures for a period of 48 hours. Article/Chapter can not be printed.

Bantu Education contributed to the reproduction of unskilled or semi-skilled black labour power in schools, appropriate to the division of labour in South Africa and to the accompanying exploitation of black workers (Enslin, 1984; Moll, 1998, pp. 263-264). Based on CNE ideology, apartheid could then be regarded as a modernized form of

period, and the mid-1940s witnessed a general crisis in the accumulation process, centred partly on labour disruption. One of the aims of Bantu Education was to facilitate the. reproduction of the ...

Bantu Education cannot continue to haunt us. The achievements of learners are still strongly (and sadly) linked to the circumstances of their birth, writes Annette Lovemore. By Staff Reporter ...

Bantu Education Act, Act No 47 of 1953. The Act was to provide for the transfer of the adminiustration and control of native education from the several provincial administrations to the Government of the Union of South Africa, and for matters incidental thereto. Click here to download.

Abstract. Various political parties, civil rights groups and columnists support the view that one of South Africa's foremost socio-economic challenges is overcoming the scarring legacy which the Bantu Education Act of 1953 left on the face of the country. In light of this challenge, a need arose to revisit the position and place of Bantu ...

In lieu of an abstract, below is the essay's first paragraph.South Africa has had to deal with issues of racial differences since colonial times. British settlers came into this foreign country and claimed it as their own. Until recently, these settlers were able to treat the black people of South Africa as a subservient and inferior race as a result of the system of apartheid. Many different ...

The Houthi's offer of an education for U.S. students sparked a wave of sarcasm by ordinary Yemenis on social media. One social media user posted a photograph of two Westerners chewing Yemen's ...

News Release. Study Shows How Higher Education Supports Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Students Through Culturally Relevant Courses, Programs, and Research. Apr 30, 2024. Apr 30, 2024. Education and Social Sciences Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development.

The groundbreaking center was created in November to meet this difficult moment. It will convene scholars and students from diverse disciplines—including the arts, humanities, social sciences, Judaic Studies, history, social work, public policy, psychology, law, sociology, media studies, management, and public health—to address the historical roots of antisemitism, its contemporary ...

Step 1: Go to the official website at sctvesd.wb.gov.in. Step 2: On the homepage, click on the link displayed as "HS VOC Result 2024." Step 3: A new window will open, enter your login details and ...

NEW DELHI: The Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) will soon announce the results for Class 10 and Class 12 board exams. Once published, students can access their mark sheets on the ...

The Associated Press is an independent global news organization dedicated to factual reporting. Founded in 1846, AP today remains the most trusted source of fast, accurate, unbiased news in all formats and the essential provider of the technology and services vital to the news business. More than half the world's population sees AP journalism ...