Open Access. Powered by Scholars. Published by Universities. ®

- Digital Commons Network ™

- / Social and Behavioral Sciences

- / Psychology

Quantitative Psychology Commons ™

Popular Articles

Based on downloads in April 2024

The Effects Of Sleep Deprivation On Online University Students' Performance , Maureen Cort-Blackson Walden University

The Effects Of Sleep Deprivation On Online University Students' Performance , Maureen Cort-Blackson

Walden dissertations and doctoral studies.

Sleep deprivation affects the academic performance of online university students, and students who have family responsibilities and a full-time job have a higher prevalence of sleep deprivation. This phenomenological study examined the lived experiences of online university students regarding sleep patterns, sleep deprivation, and the impact on their academic performance. The theoretical foundation for this study was based on the opponent processing model that explains the 2 fundamental processes necessary for individuals to function at their optimum ability: the sleep-wake homeostatic process and the circadian rhythm processes. The research question explored the beliefs and perceptions of 10 online university students, …

Go to article

Happiness Index Methodology , Laura Musikanski, Scott Cloutier, Erica Bejarano, Davi Briggs, Julia Colbert, Gracie Strasser, Steven Russell Happiness Alliance

Happiness Index Methodology , Laura Musikanski, Scott Cloutier, Erica Bejarano, Davi Briggs, Julia Colbert, Gracie Strasser, Steven Russell

Journal of sustainable social change.

The Happiness Index is a comprehensive survey instrument that assesses happiness, well-being, and aspects of sustainability and resilience. The Happiness Alliance developed the Happiness Index to provide a survey instrument to community organizers, researchers, and others seeking to use a subjective well-being index and data. It is the only instrument of its kind freely available worldwide and translated into over ten languages. This instrument can be used to measure satisfaction with life and the conditions of life. It can also be used to define income inequality, trust in government, sense of community and other aspects of well-being within specific demographics …

Understanding Of Self-Confidence In High School Students , George Ballane Walden University

Understanding Of Self-Confidence In High School Students , George Ballane

Students at a private high school in New Jersey exhibited low academic self-confidence as compared to other indicators on the ACT Engage exam. The purpose of this qualitative case study was to gain an understanding of academic self-confidence, academic performance, and learning within a sample of students. This research explored students' and teachers' perceptions of self-confidence and their impact on academic performance. The research was guided by Weiner's attribution and Bandura's self-efficacy theories. The research questions focused on 3 areas: students' and teachers' perceptions of academic self-confidence as factors impacting students' academic performance; and the perceived relationship between academic self-confidence, …

An Introduction To The Analysis Of Ranked Response Data , Holmes Finch University of Massachusetts Amherst

An Introduction To The Analysis Of Ranked Response Data , Holmes Finch

Practical assessment, research, and evaluation.

Researchers in many disciplines work with ranking data. This data type is unique in that it is often deterministic in nature (the ranks of items k -1 determine the rank of item k ), and the difference in a pair of rank scores separated by k units is equivalent regardless of the actual values of the two ranks in the pair. Given its unique qualities, there are specific statistical analyses and models designed for use with ranking data. The purpose of this manuscript is to demonstrate a strategy for analyzing ranking data from sample description through the modeling of relative …

Apr Financial Stress Scale: Development And Validation Of A Multidimensional Measurement , Wookjae Heo, Soo Hyun Cho, Philseok Lee South Dakota State University

Apr Financial Stress Scale: Development And Validation Of A Multidimensional Measurement , Wookjae Heo, Soo Hyun Cho, Philseok Lee

Journal of financial therapy.

People usually experience financial stress in managing their financial resources. Despite financial stress’s importance in life outcomes and the need for a comprehensive and theory-based measurement of the construct, few studies have addressed the conceptual issues of financial stress and its measurement. Hence, by borrowing from theories of general stress, this study attempts to fill this gap. Using an expert panel and two separate online survey samples, we developed and validated a novel financial stress scale. A total of 688 responses were used in an exploratory factor analysis and 1,115 responses were used in a confirmatory factor analysis. This multidimensional …

Negative Social Media And Its Influence On Athlete's Performance , Bernd R. Huber Cal Poly Humboldt

Negative Social Media And Its Influence On Athlete's Performance , Bernd R. Huber

Cal poly humboldt theses and projects.

This study aimed to investigate the potential impact of negative social media content on athletes' cortisol levels and subsequent performance. The study focused on the change in cortisol levels and differences in free throw performance, based on previous research findings. We hypothesized that negative social media postings would increase the stress experienced by student-athletes, resulting in elevated cortisol levels and decreased performance. Additionally, participants ( n = 8) completed a questionnaire to examine the interaction between preexisting fear and the biological stress response. Contrary to expectations, there was no significant change in stress response, and negative postings did not have …

Leadership's Impact On Employee Work Motivation And Performance , Tonia Marilu Joseph-Armstrong Walden University

Leadership's Impact On Employee Work Motivation And Performance , Tonia Marilu Joseph-Armstrong

AbstractLeadership is a major factor in terms of motivating employees, leading to enhanced performance. A study was conducted to examine the influence of supervisory leadership style on employee work motivation and job performance in organizations, specifically in a K-12 school setting. The main goal was to determine if there is a relationship between type of leadership demonstrated by school administrators and its impact on the teaching staff’s motivation and performance. Data for this quantitative study were gathered and analyzed from various public and private schools and included a sample of 100 participants. The predictor variable leadership was assessed using the …

Student Engagement Scale: Development And The Underlying Factor Structure , Patricia Isabel Quiñones Pareja California State University, San Bernardino

Student Engagement Scale: Development And The Underlying Factor Structure , Patricia Isabel QuiñOnes Pareja

Theses digitization project.

The purpose of this thesis show the strong effects attributed to student engagement on a range of educational issues, the need for a scale to measure the construct of student engagement is great.

Factors Impacting Parental Acceptance Of An Lgbt Child , Dani E. Rosenkrantz University of Kentucky

Factors Impacting Parental Acceptance Of An Lgbt Child , Dani E. Rosenkrantz

Theses and dissertations--educational, school, and counseling psychology.

Chrisler’s (2017) Theoretical Framework of Parental Reactions When a Child Comes Out as Lesbian, Gay, or Bisexual suggests that parental reactions to having a non-heteronormative child are impacted by a process of cognitively appraising information about their child’s identity and experiencing and coping with emotional responses, both of which are influenced by contextual factors such as a parent’s value system. However, some religious values can challenge parents in the process of accepting a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) child. The purpose of this study was to test a model that examines the influence of cognitive-affective factors (cognitive flexibility, emotional …

The Relationship Between Parenting Style And The Level Of Emotional Intelligence In Preschool-Aged Children , Giselle Farrell Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine

The Relationship Between Parenting Style And The Level Of Emotional Intelligence In Preschool-Aged Children , Giselle Farrell

Pcom psychology dissertations.

The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between parenting style and the level of emotional intelligence in preschool-aged children. The sample consisted of eighty parent participants of preschool-aged children between the ages of 3 and 6 years old. Participants completed the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) in order to assess their views on behaviors that parents typically demonstrate towards their children. Based on each participant’s responses on the PSDQ they were determined to favor one of the following three parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, or permissive. Participants also completed the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire- Very Short Form (CBQ-VSF) …

All Articles in Quantitative Psychology

849 full-text articles. Page 1 of 37 .

The Application Of Bayesian Meta-Analytic Models In Cognitive Research On Neurodevelopmental Disorders , Nic Zapparrata 2024 The Graduate Center, City University of New York

The Application Of Bayesian Meta-Analytic Models In Cognitive Research On Neurodevelopmental Disorders , Nic Zapparrata

Dissertations, theses, and capstone projects.

Meta-analysis is the systematic review and quantitative synthesis of specific areas in literature and is an important quantitative tool for researchers interested in synthesizing a particular body of research. The current research used meta-analysis to investigate processing speed in two neurodevelopmental disorders. This dissertation consisted of four meta-analytic papers. The first paper was a meta-analysis that synthesized a large body of research on processing speed, measured via reaction time (RT) measures, in groups of individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) versus age-matched neurotypical comparison groups. This research was motivated by two previous meta-analyses in the literature on processing speed …

Embodied Co-Regulation: A Neuroregulatory-Informed Dance/Movement Therapy Transition Intervention Method For Arousal Regulation For Adolescents In A Partial Hospitalization Program , ANAMARIA GUZMAN 2024 Lesley University

Embodied Co-Regulation: A Neuroregulatory-Informed Dance/Movement Therapy Transition Intervention Method For Arousal Regulation For Adolescents In A Partial Hospitalization Program , Anamaria Guzman

Expressive therapies capstone theses.

This thesis introduces a novel Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT) approach, focusing on nervous system arousal regulation during transitions between therapy groups. The core of the method involves a brief 5-minute exercise designed to modulate arousal levels, encompassing alertness and energy, aiming to establish a baseline homeostasis. Rooted in Polyvagal Theory and Developmental Neurobiology, the approach assumes the co-regulation of nervous systems within a group therapeutic setting. Two primary outcomes are self-assessed: 1) somatic experiences documented through narratives and 2) nervous system biodata measured using the Flowtime headband monitoring of brainwaves, heart rate, and other biomarkers. Results indicated that all six sessions …

An Investigation Of The Effectiveness Of Student’S T-Test Under Heterogeneity Of Variance , Hayden Nelson 2024 Western Kentucky University

An Investigation Of The Effectiveness Of Student’S T-Test Under Heterogeneity Of Variance , Hayden Nelson

Masters theses & specialist projects.

Within the field of psychology, few tests have been as thoroughly investigated as Student’s t-test. One area of criticism is the use of the test when the assumption for heterogeneity of variance between two samples is violated, such as when sample sizes and observed sample variances are unequal. The current study proposes a Monte Carlo analysis to observe a broad range of conditions in efforts to identify the resulting fluctuations in the proportion obtained significant results for two conditions: no mean difference (𝜇 = 𝜇) compared to the set level of alpha, and small-to-moderate mean differences (𝜇 ≠ 𝜇) compared …

Effects Of Emotional Intelligence And Social Support On The Relationship Between Childhood Maltreatment And Disordered Eating , Rachel Kilby 2024 University of Northern Colorado

Effects Of Emotional Intelligence And Social Support On The Relationship Between Childhood Maltreatment And Disordered Eating , Rachel Kilby

Undergraduate honors theses.

Current research has established a connection between childhood maltreatment and eating disorders, and some studies have looked at emotional intelligence or social support as mediators. However, little research has looked at how emotional intelligence and social support work together in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and eating disorders. This study looked at how emotional intelligence and social support act as mediators in this relationship. Undergraduate students (N=134) were administered the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-90), Wong-Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS), Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), and the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26). Correlations between scales were …

Investigating Bimanual Haptic Exploration With Arm-Support Exoskeletons , Balagopal Raveendranath 2024 Clemson University

Investigating Bimanual Haptic Exploration With Arm-Support Exoskeletons , Balagopal Raveendranath

All dissertations.

The ability to judge properties like weight and length of hand-held objects is essential in industrial work. Sometimes workers use devices like exoskeletons, which can augment their ability to lift and move heavy objects. Previous studies have investigated the perceptual information available for one-handed weight and length judgments. The current study investigated how blindfolded participants bimanually heft and wield objects to explore haptic information, to perceive object heaviness or length. The study also investigated the effects of using an arm-support exoskeleton (ASE) on the perceived weight of hand-held objects. We empirically tested whether people wield and manipulate objects differently, depending …

Praise In The Collegiate Classroom: How Narcissism, Entitlement, Empathy, And A Desire For Fame Impact Student’S Preferences For Praise , Alexandra Crissman 2024 University of Lynchburg

Praise In The Collegiate Classroom: How Narcissism, Entitlement, Empathy, And A Desire For Fame Impact Student’S Preferences For Praise , Alexandra Crissman

Student scholar showcase.

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between personality traits, namely narcissism, entitlement, empathy, and a desire for fame, and a preference for public praise in a student population. Past research has shown that those who are higher in narcissism are also higher in entitlement and that these rates have been rising with future generations. Past research has also indicated a negative relationship between narcissistic tendencies and empathy, inferring that those higher in narcissism tend to score lower on empathy measures. In this study, undergraduate students were surveyed online to determine scores on four measures of traits …

Buffering Effects Of Negative Intergroup Contact Through Complex Social Identities , Liora Morhayim 2024 University of Massachusetts Amherst

Buffering Effects Of Negative Intergroup Contact Through Complex Social Identities , Liora Morhayim

Masters theses.

Although negative intergroup contact occurs less frequently than positive contact, negative contact can more strongly influence outgroup attitudes and behaviors due to the effect of category salience in the generalization process. The present study ( N =306) tests whether being aware of an outgroup member’s complex social identity will serve as a buffer against the adverse impact of a negative intergroup contact experience on outgroup attitudes. In a 3X2 between-subjects design, social identity complexity (SIC) of an outgroup confederate (high versus low versus control) and the valence of contact (neutral versus negative) were manipulated. Participants interacted with an outgroup confederate …

The Relationship Between Cognitive Impairment In Psychiatric Patients And Readmission Rate To An Inpatient Facility , Cherilyn Isis Schuff 2024 Florida Institute of Technology

The Relationship Between Cognitive Impairment In Psychiatric Patients And Readmission Rate To An Inpatient Facility , Cherilyn Isis Schuff

Theses and dissertations.

The primary intention of this study was to further understand the impact of assessing cognitive impairment in psychiatric patients, as a mediating factor on readmission rates. Mild cognitive dysfunction impacts a patient’s functional outcomes (Bowie & Harvey, 2006; Davis et al., 2012; Marcantonio, et al., 2001). Little information exists to guide best practices in the treatment of adults with cognitive impairment who are hospitalized for acute conditions (Davis et al., 2012). A cognitive impairment may impact patient prognosis and ability to function outside of a setting focused on stabilization. Neuropsychological testing is a valuable tool in predicting a patient’s cognitive …

Examining Differences In Self-Concept And Language Between Monolingual And Bilingual Undergraduate Students , Marilyn Vega-Wagner 2024 University of the Pacific

Examining Differences In Self-Concept And Language Between Monolingual And Bilingual Undergraduate Students , Marilyn Vega-Wagner

University of the pacific theses and dissertations.

The literature is lacking in studies that examine self-concept and language status among individuals older than adolescence. The purpose of this study is to conduct a quantitative nonexperimental comparative design to examine differences in self-concept and language status (monolingual or bilingual) between male and female undergraduate students in California. A total of 97 participants were examined in the study. The researcher conducted descriptive statistics on the demographics as well as a MANOVA and an ANOVA to answer the proposed research question. Based on the findings presented, the researcher failed to reject the null hypothesis of research question 1: There is …

The Effect Of Email Communication On Professor-Student Rapport, Academic Self-Efficacy, Resiliency, Motivation, And Spirituality , David J. Heim 2024 Missouri State University

The Effect Of Email Communication On Professor-Student Rapport, Academic Self-Efficacy, Resiliency, Motivation, And Spirituality , David J. Heim

Msu graduate theses.

Student retention and success rates are an increasing concern among collegiate administrators and educators. This study examined the influence of a college instructor’s email communications on professor-student rapport, student academic self-efficacy, resilience, motivation, and success. Researchers hypothesized that the student participants who received the encouraging email communications from their professor would demonstrate higher levels of professor-student rapport, higher levels of academic self-efficacy, resiliency, and success compared to the students who receive standard email communications from their professor. Five scales were utilized in this study including Professor-Student Rapport Scale, Academic Self-Efficacy Scale, Academic Resilience Scale (ARS-30), Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES), …

Consistent Across Situations? A Person Specific Approach To Examining A Long-Standing Paradox. , Muchen Xi 2023 Washington University in St. Louis

Consistent Across Situations? A Person Specific Approach To Examining A Long-Standing Paradox. , Muchen Xi

Arts & sciences electronic theses and dissertations.

Bem and Allen (1974) address the person situation debate by proposing that there are some people behave more consistently, which can be better “explained” try personality traits, than others who are more influenced by situations. However, with failures to directly replicate Bem and Allen’s study, the existence of individual difference in cross situation consistency of behaviors remaining unclear. The current study addressed open questions that arose from the personality consistency debate by employing Mixed Effect Location Scale Model (MELSM) in an intensive longitudinal study. We found 1) there are individual difference in the overall behavioral consistency across situations; 2) there …

Detecting Careless Cases In Practice Tests , Steven Nydick 2023 Duolingo

Detecting Careless Cases In Practice Tests , Steven Nydick

Chinese/english journal of educational measurement and evaluation | 教育测量与评估双语期刊.

In this paper, we present a novel method for detecting careless responses in a low-stakes practice exam using machine learning models. Rather than classifying test-taker responses as careless based on model fit statistics or knowledge of truth, we built a model to predict significant changes in test scores between a practice test and an official test based on attributes of practice test items. We extracted features from practice test items using hypotheses about how careless test takers respond to items and cross-validated model performance to optimize out-of-sample predictions and reduce heteroscedasticity when predicting the closest official test. All analyses use …

Critical Transitions In Mental Health: Van Gogh Case Study , Anna Singley 2023 University of Portland

Critical Transitions In Mental Health: Van Gogh Case Study , Anna Singley

Annual symposium on biomathematics and ecology education and research.

No abstract provided.

The Effectiveness Of Computerized Neurofeedback As An Accompanying Or Alternative Therapeutic Intervention For Pharmacological Treatment In Improving Attention And Other Symptoms For Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Adhd) , Eqbal Z. Darandari PhD, Nouf F. Alsultan 2023 King Saud University

The Effectiveness Of Computerized Neurofeedback As An Accompanying Or Alternative Therapeutic Intervention For Pharmacological Treatment In Improving Attention And Other Symptoms For Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Adhd) , Eqbal Z. Darandari Phd, Nouf F. Alsultan

International journal for research in education.

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of a treatment program using computerized neuro-feedback in improving attention for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). To achieve the aim of the study, the computerized neurofeedback program was applied to (56) children diagnosed with (ADHD), aged between (7-11) years. They were distributed into four groups: the first group was subjected to combined intervention (neurofeedback & pharmacological treatment), the second group was subjected to (neurofeedback only), while the third group was exposed to the intervention using (pharmacological treatment only), and the fourth group was (not exposed to any intervention). Test of Variables …

A Psychometric Analysis Of Natural Language Inference Using Transformer Language Models , Antonio Laverghetta Jr. 2023 University of South Florida

A Psychometric Analysis Of Natural Language Inference Using Transformer Language Models , Antonio Laverghetta Jr.

Usf tampa graduate theses and dissertations.

Large language models (LLMs) are poised to transform both academia and industry. But the excitement around these generative AIs has also been met with concern for the true extent of their capabilities. This dissertation helps to address these questions by examining the capabilities of LLMs using the tools of psychometrics. We focus on analyzing the capabilities of LLMs on the task of natural language inference (NLI), a foundational benchmark often used to evaluate new models. We demonstrate that LLMs can reliably predict the psychometric properties of NLI items were those items administered to humans. Through a series of experiments, we …

A New Method To Determine The Posterior Distribution Of Coefficient Alpha , John Mart V. DelosReyes 2023 Old Dominion University

A New Method To Determine The Posterior Distribution Of Coefficient Alpha , John Mart V. Delosreyes

Psychology theses & dissertations.

There is a focus within the behavioral/social sciences on non-physical, psychological constructs (i.e., constructs). These constructs are indirectly measured using measurement instruments that consist of questions that capture the manifestations of these constructs. The indirect nature of measuring constructs results in a need of ensuring that measurement instruments are reliable. The most popular statistic used to estimate reliability is coefficient alpha as it is easy to compute and has properties that make it desirable to use. Coefficient alpha’s popularity has resulted in a wide breadth of research into its qualities. Notably, research about coefficient alpha’s distribution has led to developments …

Examining The Relationship Between Counselor Professional Identity And Burnout , Jessica Gaul 2023 Antioch University Seattle

Examining The Relationship Between Counselor Professional Identity And Burnout , Jessica Gaul

Antioch university full-text dissertations & theses.

This study examines counselor professional identity and burnout for clinical mental health counselors. The population of focus included licensed or license-eligible Clinical Mental Health Counselors, who were post-grad (N=53). Participants then completed the Professional Identity Scale in Counseling - Short Form and the Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services Survey. When examining the findings regarding the relationship between Counselor Professional Identity and Burnout for this study, the initial observation revealed the validity and applicability of the MBI-HSS to clinical mental health counselors. Though a relationship between Burnout and Counselor Professional Identity was not identified, relationships between sub-scale items were noteworthy. Implications for …

Recentering Psych Stats , Lynette Bikos 2023 Seattle Pacific University

Recentering Psych Stats , Lynette Bikos

Faculty open access books.

To center a variable in regression means to set its value at zero and interpret all other values in relation to this reference point. Regarding race and gender, researchers often center male and White at zero. Further, it is typical that research vignettes in statistics textbooks are similarly seated in a White, Western (frequently U.S.), heteronormative, framework. ReCentering Psych Stats seeks provide statistics training for psychology students (undergraduate, graduate, and post-doctoral) in a socially and culturally responsive way. All lessons use the open-source statistics program, R (and its associated packages). Each lesson includes a chapter and screencasted lesson, features a …

Exploring The Dimensions And Dynamics Of Partnered Sexual Behaviours: Scale Development And Validation Using Factor And Network Analysis , Devinder S. Khera 2023 Western University

Exploring The Dimensions And Dynamics Of Partnered Sexual Behaviours: Scale Development And Validation Using Factor And Network Analysis , Devinder S. Khera

Electronic thesis and dissertation repository.

Sexual behaviours are an integral part of most intimate relationships and can serve as mechanisms for building intimacy, enhancing emotional connection, and can serve as non-verbal communication to express care, love, and compassion for significant others. Sexually compatible behaviours are also associated with sexual satisfaction – something especially important given the downstream consequences of sexual satisfaction on relationship satisfaction, relationship stability, and general well-being. However, to date, no inclusive, psychometrically validated measure of partnered sexual interests and behaviours exists. Given the central role of sexual interests and behaviours in sexual satisfaction and in turn relationship quality, we sought to develop …

Average Or Outlier? Introductory Statistics Adjunct Instructors’ Beliefs, Practices, And Experiences , Samantha Estrada Aguilera, Erica Martinez 2023 University of Texas at Tyler

Average Or Outlier? Introductory Statistics Adjunct Instructors’ Beliefs, Practices, And Experiences , Samantha Estrada Aguilera, Erica Martinez

The qualitative report.

In recent years, the adjunct faculty phenomenon has grown steadily. This research focused on adjunct instructors teaching introductory statistics courses. The purpose of the study was to give a voice to adjunct instructors by allowing them to describe their experiences teaching statistics. We conducted a qualitative study with 15 adjunct instructors of introductory statistics through semi-structured interviews. The participants came from several fields: psychology, nursing, and business, among others. Thematic analysis was used to find themes of statistical anxiety, use of technology in the classroom, lack of curriculum flexibility, and connection to the host institution. Our findings can inform institutions …

Popular Institutions

Featured Publications

Popular authors.

- Applied Behavior Analysis

- Biological Psychology

- Child Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognition and Perception

- Cognitive Psychology

- Community Psychology

- Comparative Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Experimental Analysis of Behavior

- Geropsychology

- Health Psychology

- Human Factors Psychology

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Multicultural Psychology

- Other Psychology

- Pain Management

- Personality and Social Contexts

- School Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Somatic Psychology

- Theory and Philosophy

- Transpersonal Psychology

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 11: Presenting Your Research

Writing a Research Report in American Psychological Association (APA) Style

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major sections of an APA-style research report and the basic contents of each section.

- Plan and write an effective APA-style research report.

In this section, we look at how to write an APA-style empirical research report , an article that presents the results of one or more new studies. Recall that the standard sections of an empirical research report provide a kind of outline. Here we consider each of these sections in detail, including what information it contains, how that information is formatted and organized, and tips for writing each section. At the end of this section is a sample APA-style research report that illustrates many of these principles.

Sections of a Research Report

Title page and abstract.

An APA-style research report begins with a title page . The title is centred in the upper half of the page, with each important word capitalized. The title should clearly and concisely (in about 12 words or fewer) communicate the primary variables and research questions. This sometimes requires a main title followed by a subtitle that elaborates on the main title, in which case the main title and subtitle are separated by a colon. Here are some titles from recent issues of professional journals published by the American Psychological Association.

- Sex Differences in Coping Styles and Implications for Depressed Mood

- Effects of Aging and Divided Attention on Memory for Items and Their Contexts

- Computer-Assisted Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Child Anxiety: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial

- Virtual Driving and Risk Taking: Do Racing Games Increase Risk-Taking Cognitions, Affect, and Behaviour?

Below the title are the authors’ names and, on the next line, their institutional affiliation—the university or other institution where the authors worked when they conducted the research. As we have already seen, the authors are listed in an order that reflects their contribution to the research. When multiple authors have made equal contributions to the research, they often list their names alphabetically or in a randomly determined order.

In some areas of psychology, the titles of many empirical research reports are informal in a way that is perhaps best described as “cute.” They usually take the form of a play on words or a well-known expression that relates to the topic under study. Here are some examples from recent issues of the Journal Psychological Science .

- “Smells Like Clean Spirit: Nonconscious Effects of Scent on Cognition and Behavior”

- “Time Crawls: The Temporal Resolution of Infants’ Visual Attention”

- “Scent of a Woman: Men’s Testosterone Responses to Olfactory Ovulation Cues”

- “Apocalypse Soon?: Dire Messages Reduce Belief in Global Warming by Contradicting Just-World Beliefs”

- “Serial vs. Parallel Processing: Sometimes They Look Like Tweedledum and Tweedledee but They Can (and Should) Be Distinguished”

- “How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Words: The Social Effects of Expressive Writing”

Individual researchers differ quite a bit in their preference for such titles. Some use them regularly, while others never use them. What might be some of the pros and cons of using cute article titles?

For articles that are being submitted for publication, the title page also includes an author note that lists the authors’ full institutional affiliations, any acknowledgments the authors wish to make to agencies that funded the research or to colleagues who commented on it, and contact information for the authors. For student papers that are not being submitted for publication—including theses—author notes are generally not necessary.

The abstract is a summary of the study. It is the second page of the manuscript and is headed with the word Abstract . The first line is not indented. The abstract presents the research question, a summary of the method, the basic results, and the most important conclusions. Because the abstract is usually limited to about 200 words, it can be a challenge to write a good one.

Introduction

The introduction begins on the third page of the manuscript. The heading at the top of this page is the full title of the manuscript, with each important word capitalized as on the title page. The introduction includes three distinct subsections, although these are typically not identified by separate headings. The opening introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting, the literature review discusses relevant previous research, and the closing restates the research question and comments on the method used to answer it.

The Opening

The opening , which is usually a paragraph or two in length, introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting. To capture the reader’s attention, researcher Daryl Bem recommends starting with general observations about the topic under study, expressed in ordinary language (not technical jargon)—observations that are about people and their behaviour (not about researchers or their research; Bem, 2003 [1] ). Concrete examples are often very useful here. According to Bem, this would be a poor way to begin a research report:

Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance received a great deal of attention during the latter part of the 20th century (p. 191)

The following would be much better:

The individual who holds two beliefs that are inconsistent with one another may feel uncomfortable. For example, the person who knows that he or she enjoys smoking but believes it to be unhealthy may experience discomfort arising from the inconsistency or disharmony between these two thoughts or cognitions. This feeling of discomfort was called cognitive dissonance by social psychologist Leon Festinger (1957), who suggested that individuals will be motivated to remove this dissonance in whatever way they can (p. 191).

After capturing the reader’s attention, the opening should go on to introduce the research question and explain why it is interesting. Will the answer fill a gap in the literature? Will it provide a test of an important theory? Does it have practical implications? Giving readers a clear sense of what the research is about and why they should care about it will motivate them to continue reading the literature review—and will help them make sense of it.

Breaking the Rules

Researcher Larry Jacoby reported several studies showing that a word that people see or hear repeatedly can seem more familiar even when they do not recall the repetitions—and that this tendency is especially pronounced among older adults. He opened his article with the following humourous anecdote:

A friend whose mother is suffering symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) tells the story of taking her mother to visit a nursing home, preliminary to her mother’s moving there. During an orientation meeting at the nursing home, the rules and regulations were explained, one of which regarded the dining room. The dining room was described as similar to a fine restaurant except that tipping was not required. The absence of tipping was a central theme in the orientation lecture, mentioned frequently to emphasize the quality of care along with the advantages of having paid in advance. At the end of the meeting, the friend’s mother was asked whether she had any questions. She replied that she only had one question: “Should I tip?” (Jacoby, 1999, p. 3)

Although both humour and personal anecdotes are generally discouraged in APA-style writing, this example is a highly effective way to start because it both engages the reader and provides an excellent real-world example of the topic under study.

The Literature Review

Immediately after the opening comes the literature review , which describes relevant previous research on the topic and can be anywhere from several paragraphs to several pages in length. However, the literature review is not simply a list of past studies. Instead, it constitutes a kind of argument for why the research question is worth addressing. By the end of the literature review, readers should be convinced that the research question makes sense and that the present study is a logical next step in the ongoing research process.

Like any effective argument, the literature review must have some kind of structure. For example, it might begin by describing a phenomenon in a general way along with several studies that demonstrate it, then describing two or more competing theories of the phenomenon, and finally presenting a hypothesis to test one or more of the theories. Or it might describe one phenomenon, then describe another phenomenon that seems inconsistent with the first one, then propose a theory that resolves the inconsistency, and finally present a hypothesis to test that theory. In applied research, it might describe a phenomenon or theory, then describe how that phenomenon or theory applies to some important real-world situation, and finally suggest a way to test whether it does, in fact, apply to that situation.

Looking at the literature review in this way emphasizes a few things. First, it is extremely important to start with an outline of the main points that you want to make, organized in the order that you want to make them. The basic structure of your argument, then, should be apparent from the outline itself. Second, it is important to emphasize the structure of your argument in your writing. One way to do this is to begin the literature review by summarizing your argument even before you begin to make it. “In this article, I will describe two apparently contradictory phenomena, present a new theory that has the potential to resolve the apparent contradiction, and finally present a novel hypothesis to test the theory.” Another way is to open each paragraph with a sentence that summarizes the main point of the paragraph and links it to the preceding points. These opening sentences provide the “transitions” that many beginning researchers have difficulty with. Instead of beginning a paragraph by launching into a description of a previous study, such as “Williams (2004) found that…,” it is better to start by indicating something about why you are describing this particular study. Here are some simple examples:

Another example of this phenomenon comes from the work of Williams (2004).

Williams (2004) offers one explanation of this phenomenon.

An alternative perspective has been provided by Williams (2004).

We used a method based on the one used by Williams (2004).

Finally, remember that your goal is to construct an argument for why your research question is interesting and worth addressing—not necessarily why your favourite answer to it is correct. In other words, your literature review must be balanced. If you want to emphasize the generality of a phenomenon, then of course you should discuss various studies that have demonstrated it. However, if there are other studies that have failed to demonstrate it, you should discuss them too. Or if you are proposing a new theory, then of course you should discuss findings that are consistent with that theory. However, if there are other findings that are inconsistent with it, again, you should discuss them too. It is acceptable to argue that the balance of the research supports the existence of a phenomenon or is consistent with a theory (and that is usually the best that researchers in psychology can hope for), but it is not acceptable to ignore contradictory evidence. Besides, a large part of what makes a research question interesting is uncertainty about its answer.

The Closing

The closing of the introduction—typically the final paragraph or two—usually includes two important elements. The first is a clear statement of the main research question or hypothesis. This statement tends to be more formal and precise than in the opening and is often expressed in terms of operational definitions of the key variables. The second is a brief overview of the method and some comment on its appropriateness. Here, for example, is how Darley and Latané (1968) [2] concluded the introduction to their classic article on the bystander effect:

These considerations lead to the hypothesis that the more bystanders to an emergency, the less likely, or the more slowly, any one bystander will intervene to provide aid. To test this proposition it would be necessary to create a situation in which a realistic “emergency” could plausibly occur. Each subject should also be blocked from communicating with others to prevent his getting information about their behaviour during the emergency. Finally, the experimental situation should allow for the assessment of the speed and frequency of the subjects’ reaction to the emergency. The experiment reported below attempted to fulfill these conditions. (p. 378)

Thus the introduction leads smoothly into the next major section of the article—the method section.

The method section is where you describe how you conducted your study. An important principle for writing a method section is that it should be clear and detailed enough that other researchers could replicate the study by following your “recipe.” This means that it must describe all the important elements of the study—basic demographic characteristics of the participants, how they were recruited, whether they were randomly assigned, how the variables were manipulated or measured, how counterbalancing was accomplished, and so on. At the same time, it should avoid irrelevant details such as the fact that the study was conducted in Classroom 37B of the Industrial Technology Building or that the questionnaire was double-sided and completed using pencils.

The method section begins immediately after the introduction ends with the heading “Method” (not “Methods”) centred on the page. Immediately after this is the subheading “Participants,” left justified and in italics. The participants subsection indicates how many participants there were, the number of women and men, some indication of their age, other demographics that may be relevant to the study, and how they were recruited, including any incentives given for participation.

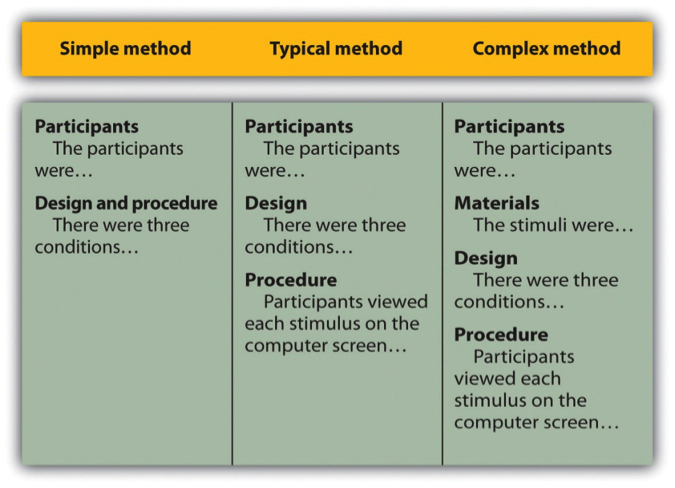

After the participants section, the structure can vary a bit. Figure 11.1 shows three common approaches. In the first, the participants section is followed by a design and procedure subsection, which describes the rest of the method. This works well for methods that are relatively simple and can be described adequately in a few paragraphs. In the second approach, the participants section is followed by separate design and procedure subsections. This works well when both the design and the procedure are relatively complicated and each requires multiple paragraphs.

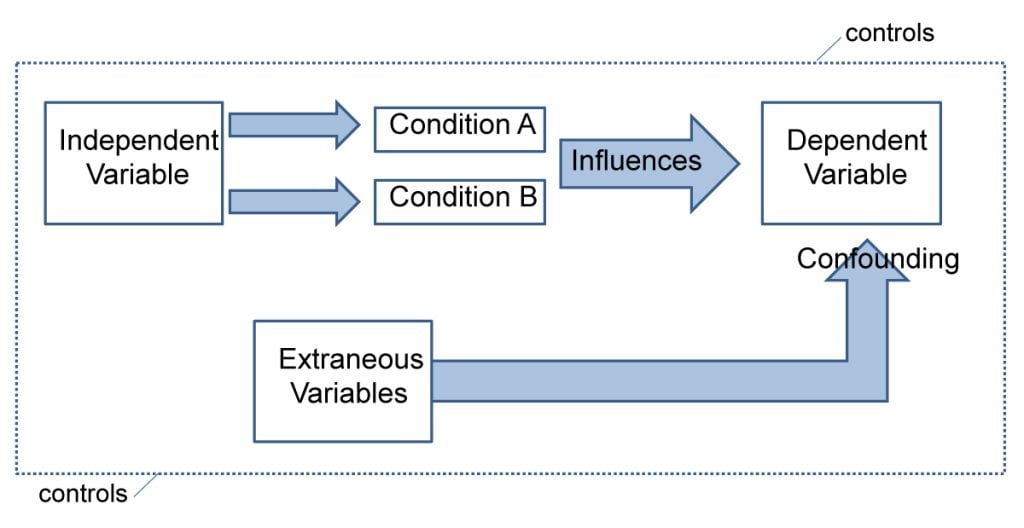

What is the difference between design and procedure? The design of a study is its overall structure. What were the independent and dependent variables? Was the independent variable manipulated, and if so, was it manipulated between or within subjects? How were the variables operationally defined? The procedure is how the study was carried out. It often works well to describe the procedure in terms of what the participants did rather than what the researchers did. For example, the participants gave their informed consent, read a set of instructions, completed a block of four practice trials, completed a block of 20 test trials, completed two questionnaires, and were debriefed and excused.

In the third basic way to organize a method section, the participants subsection is followed by a materials subsection before the design and procedure subsections. This works well when there are complicated materials to describe. This might mean multiple questionnaires, written vignettes that participants read and respond to, perceptual stimuli, and so on. The heading of this subsection can be modified to reflect its content. Instead of “Materials,” it can be “Questionnaires,” “Stimuli,” and so on.

The results section is where you present the main results of the study, including the results of the statistical analyses. Although it does not include the raw data—individual participants’ responses or scores—researchers should save their raw data and make them available to other researchers who request them. Several journals now encourage the open sharing of raw data online.

Although there are no standard subsections, it is still important for the results section to be logically organized. Typically it begins with certain preliminary issues. One is whether any participants or responses were excluded from the analyses and why. The rationale for excluding data should be described clearly so that other researchers can decide whether it is appropriate. A second preliminary issue is how multiple responses were combined to produce the primary variables in the analyses. For example, if participants rated the attractiveness of 20 stimulus people, you might have to explain that you began by computing the mean attractiveness rating for each participant. Or if they recalled as many items as they could from study list of 20 words, did you count the number correctly recalled, compute the percentage correctly recalled, or perhaps compute the number correct minus the number incorrect? A third preliminary issue is the reliability of the measures. This is where you would present test-retest correlations, Cronbach’s α, or other statistics to show that the measures are consistent across time and across items. A final preliminary issue is whether the manipulation was successful. This is where you would report the results of any manipulation checks.

The results section should then tackle the primary research questions, one at a time. Again, there should be a clear organization. One approach would be to answer the most general questions and then proceed to answer more specific ones. Another would be to answer the main question first and then to answer secondary ones. Regardless, Bem (2003) [3] suggests the following basic structure for discussing each new result:

- Remind the reader of the research question.

- Give the answer to the research question in words.

- Present the relevant statistics.

- Qualify the answer if necessary.

- Summarize the result.

Notice that only Step 3 necessarily involves numbers. The rest of the steps involve presenting the research question and the answer to it in words. In fact, the basic results should be clear even to a reader who skips over the numbers.

The discussion is the last major section of the research report. Discussions usually consist of some combination of the following elements:

- Summary of the research

- Theoretical implications

- Practical implications

- Limitations

- Suggestions for future research

The discussion typically begins with a summary of the study that provides a clear answer to the research question. In a short report with a single study, this might require no more than a sentence. In a longer report with multiple studies, it might require a paragraph or even two. The summary is often followed by a discussion of the theoretical implications of the research. Do the results provide support for any existing theories? If not, how can they be explained? Although you do not have to provide a definitive explanation or detailed theory for your results, you at least need to outline one or more possible explanations. In applied research—and often in basic research—there is also some discussion of the practical implications of the research. How can the results be used, and by whom, to accomplish some real-world goal?

The theoretical and practical implications are often followed by a discussion of the study’s limitations. Perhaps there are problems with its internal or external validity. Perhaps the manipulation was not very effective or the measures not very reliable. Perhaps there is some evidence that participants did not fully understand their task or that they were suspicious of the intent of the researchers. Now is the time to discuss these issues and how they might have affected the results. But do not overdo it. All studies have limitations, and most readers will understand that a different sample or different measures might have produced different results. Unless there is good reason to think they would have, however, there is no reason to mention these routine issues. Instead, pick two or three limitations that seem like they could have influenced the results, explain how they could have influenced the results, and suggest ways to deal with them.

Most discussions end with some suggestions for future research. If the study did not satisfactorily answer the original research question, what will it take to do so? What new research questions has the study raised? This part of the discussion, however, is not just a list of new questions. It is a discussion of two or three of the most important unresolved issues. This means identifying and clarifying each question, suggesting some alternative answers, and even suggesting ways they could be studied.

Finally, some researchers are quite good at ending their articles with a sweeping or thought-provoking conclusion. Darley and Latané (1968) [4] , for example, ended their article on the bystander effect by discussing the idea that whether people help others may depend more on the situation than on their personalities. Their final sentence is, “If people understand the situational forces that can make them hesitate to intervene, they may better overcome them” (p. 383). However, this kind of ending can be difficult to pull off. It can sound overreaching or just banal and end up detracting from the overall impact of the article. It is often better simply to end when you have made your final point (although you should avoid ending on a limitation).

The references section begins on a new page with the heading “References” centred at the top of the page. All references cited in the text are then listed in the format presented earlier. They are listed alphabetically by the last name of the first author. If two sources have the same first author, they are listed alphabetically by the last name of the second author. If all the authors are the same, then they are listed chronologically by the year of publication. Everything in the reference list is double-spaced both within and between references.

Appendices, Tables, and Figures

Appendices, tables, and figures come after the references. An appendix is appropriate for supplemental material that would interrupt the flow of the research report if it were presented within any of the major sections. An appendix could be used to present lists of stimulus words, questionnaire items, detailed descriptions of special equipment or unusual statistical analyses, or references to the studies that are included in a meta-analysis. Each appendix begins on a new page. If there is only one, the heading is “Appendix,” centred at the top of the page. If there is more than one, the headings are “Appendix A,” “Appendix B,” and so on, and they appear in the order they were first mentioned in the text of the report.

After any appendices come tables and then figures. Tables and figures are both used to present results. Figures can also be used to illustrate theories (e.g., in the form of a flowchart), display stimuli, outline procedures, and present many other kinds of information. Each table and figure appears on its own page. Tables are numbered in the order that they are first mentioned in the text (“Table 1,” “Table 2,” and so on). Figures are numbered the same way (“Figure 1,” “Figure 2,” and so on). A brief explanatory title, with the important words capitalized, appears above each table. Each figure is given a brief explanatory caption, where (aside from proper nouns or names) only the first word of each sentence is capitalized. More details on preparing APA-style tables and figures are presented later in the book.

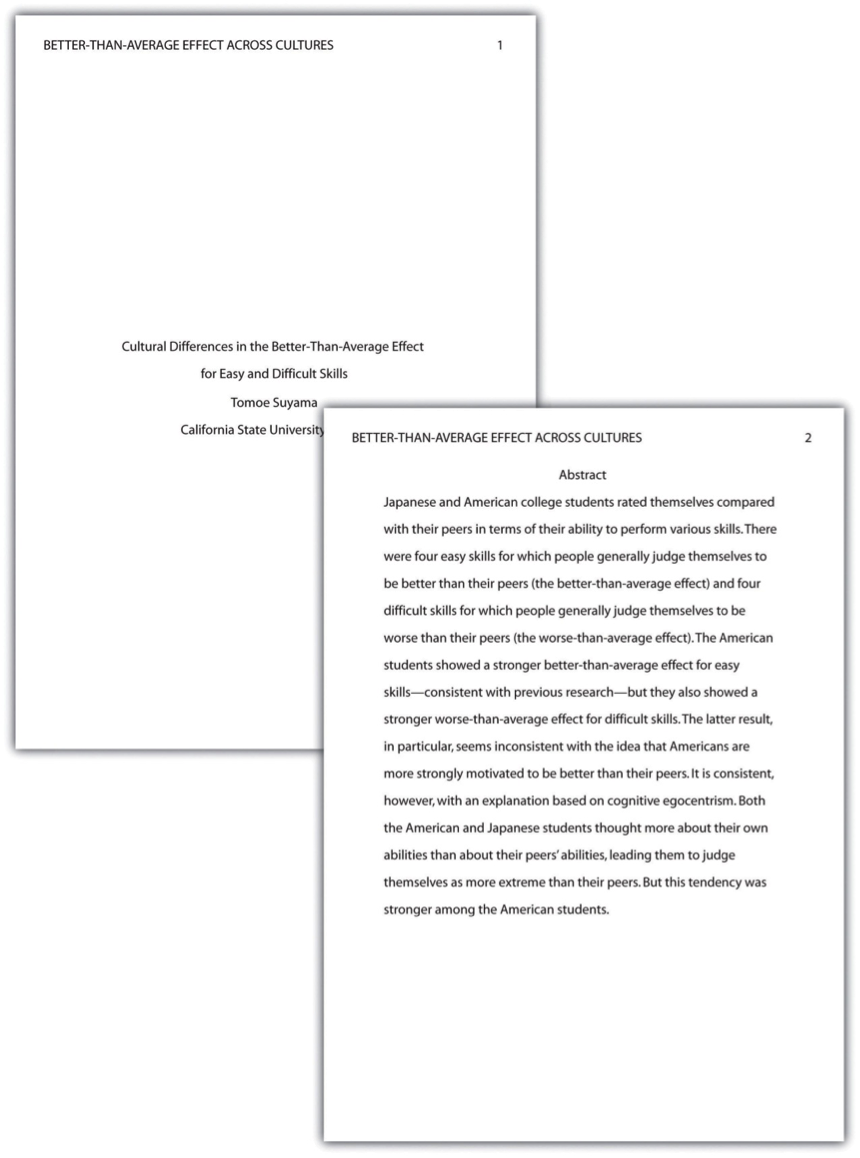

Sample APA-Style Research Report

Figures 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, and 11.5 show some sample pages from an APA-style empirical research report originally written by undergraduate student Tomoe Suyama at California State University, Fresno. The main purpose of these figures is to illustrate the basic organization and formatting of an APA-style empirical research report, although many high-level and low-level style conventions can be seen here too.

Key Takeaways

- An APA-style empirical research report consists of several standard sections. The main ones are the abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, and references.

- The introduction consists of an opening that presents the research question, a literature review that describes previous research on the topic, and a closing that restates the research question and comments on the method. The literature review constitutes an argument for why the current study is worth doing.

- The method section describes the method in enough detail that another researcher could replicate the study. At a minimum, it consists of a participants subsection and a design and procedure subsection.

- The results section describes the results in an organized fashion. Each primary result is presented in terms of statistical results but also explained in words.

- The discussion typically summarizes the study, discusses theoretical and practical implications and limitations of the study, and offers suggestions for further research.

- Practice: Look through an issue of a general interest professional journal (e.g., Psychological Science ). Read the opening of the first five articles and rate the effectiveness of each one from 1 ( very ineffective ) to 5 ( very effective ). Write a sentence or two explaining each rating.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and identify where the opening, literature review, and closing of the introduction begin and end.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and highlight in a different colour each of the following elements in the discussion: summary, theoretical implications, practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Long Descriptions

Figure 11.1 long description: Table showing three ways of organizing an APA-style method section.

In the simple method, there are two subheadings: “Participants” (which might begin “The participants were…”) and “Design and procedure” (which might begin “There were three conditions…”).

In the typical method, there are three subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”).

In the complex method, there are four subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Materials” (“The stimuli were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”). [Return to Figure 11.1]

- Bem, D. J. (2003). Writing the empirical journal article. In J. M. Darley, M. P. Zanna, & H. R. Roediger III (Eds.), The compleat academic: A practical guide for the beginning social scientist (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4 , 377–383. ↵

A type of research article which describes one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors.

The page at the beginning of an APA-style research report containing the title of the article, the authors’ names, and their institutional affiliation.

A summary of a research study.

The third page of a manuscript containing the research question, the literature review, and comments about how to answer the research question.

An introduction to the research question and explanation for why this question is interesting.

A description of relevant previous research on the topic being discusses and an argument for why the research is worth addressing.

The end of the introduction, where the research question is reiterated and the method is commented upon.

The section of a research report where the method used to conduct the study is described.

The main results of the study, including the results from statistical analyses, are presented in a research article.

Section of a research report that summarizes the study's results and interprets them by referring back to the study's theoretical background.

Part of a research report which contains supplemental material.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Quantitative Methods in Psychology: Inevitable and Useless

Aaro toomela.

1 Institute of Psychology, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia

Science begins with the question, what do I want to know? Science becomes science, however, only when this question is justified and the appropriate methodology is chosen for answering the research question. Research question should precede the other questions; methods should be chosen according to the research question and not vice versa. Modern quantitative psychology has accepted method as primary; research questions are adjusted to the methods. For understanding thinking in modern quantitative psychology, two epistemologies should be distinguished: structural-systemic that is based on Aristotelian thinking, and associative-quantitative that is based on Cartesian–Humean thinking. The first aims at understanding the structure that underlies the studied processes; the second looks for identification of cause–effect relationships between the events with no possible access to the understanding of the structures that underlie the processes. Quantitative methodology in particular as well as mathematical psychology in general, is useless for answering questions about structures and processes that underlie observed behaviors. Nevertheless, quantitative science is almost inevitable in a situation where the systemic-structural basis of behavior is not well understood; all sorts of applied decisions can be made on the basis of quantitative studies. In order to proceed, psychology should study structures; methodologically, constructive experiments should be added to observations and analytic experiments.

Science begins with questions. Everybody can have questions, and even answers to them. What makes science special is its method of answering questions. Therefore a scientist must ask questions both about the phenomenon to be understood and about the method. There are actually not one or two but four principal questions that should be asked by every scientist when conducting studies (Toomela, 2010b ):

- What do I want to know, what is my research question?

- Why I want to have an answer to this question?

- With what specific research procedures (methodology in the strict sense of the term) can I answer my question?

- Are the answers to three first questions complementary, do they make a coherent theoretically justified whole?

First, there should be a question about some phenomenon that needs an answer. Next, the need for an answer should be justified – in science it is quite possible to ask “wrong” questions, which answers do not help understanding the studied phenomena. Vygotsky ( 1982a ) gave in his colorful language an ironic example of answering scientifically wrong questions:

One can multiply the number of citizens of Paraguay with the number of versts [an obsolete Russian unit of length] from Earth to Sun and divide the result with the average length of life of an elephant and conduct this whole operation without a flaw even in one number; and yet the number found in the operation can confuse anybody who would like to know the national income of that country (p. 326; my translation).

It can be said that modern psychology is more advanced than science of Vygotsky's time; perhaps the questions asked in the modern science are meaningful. This opinion, however, may be wrong. One source of wrong questions about the studied phenomena is unsatisfactory answer to the last question – when answers to first three questions do not agree one with another. In this paper I am going to suggest that psychology asks “wrong” questions far too often. The problem is related to the mismatch in answers to the first and third question. Specifically, quantitative methodology that dominates psychology of today is not appropriate for achieving understanding of mental phenomena, psyche.

The number of substantial problems with quantitative methods brought out by scholars is increasing every year. Already one observation could make scientists cautious. The questions provided above are in a certain order – first we should have a question about the phenomenon and only then the appropriate method for finding an answer should be looked for. Substantial part of modern psychology follows the opposite order of decisions – first it is decided to use quantitative methods, and the question about the phenomenon is already formulated in the language of data analysis. Between 1940 and 1955, statistical data analysis became the indispensable tool for hypothesis testing; with this change of scientific methodology, statistical methods began to turn into theories of mind. Instead of looking for theory that perhaps can be elaborated with the help of statistical tools, statistical tools began to determine the shape of theories (Gigerenzer, 1991 , 1993 ).

For instance, a researcher may ask, how many factors emerge in the analysis of personality or intelligence test results. But why to look for the number of factors if personality or intelligence is studied? We would guess here that the original question may be something like, is it possible to identify distinguishable components in the structure of personality or intelligence? However, the decision to use factor analysis for that purpose must be justified before this method is chosen. This justification seems to be missing; it is only a hypothesis – ungrounded hypothesis – that factor analysis is an appropriate tool for identifying distinct mental processes that underlie behavioral data (filling in a questionnaire is behavior). The problems emerge already with the determination of the number of factors to retain. There are formal and substantial criteria for that. Formal decisions are based on Kaiser's criterion, Cattel's scree test, Velicer's Minimum Average Partial test, or Horn's parallel analysis. There is no evidence that any of these criteria is actually suitable for distinguishing the number of distinct processes that underlie behavior. Researchers also decide the number of factors on the basis of comprehensibility – the solution which generates the most comprehensible factor structure is chosen. But this substantial criterion is always used after applying formal criteria; nobody starts from the possibility that all, say, 248 items of an inventory correspond to 248 distinct mental processes. The number of factors usually retained – from two to six or seven – seems to correspond to processing limitations of the researcher's working memory rather than to true structure of the mind.

In this paper, epistemological issues that underlie quantitative methods used in psychology are discussed. I suggest that, regardless of the research area in psychology, mathematical procedures of any kind cannot answer questions about the structure of mind. The discussion focuses primarily on the statistical methodology as used in psychology today; yet there are fundamental problems inherent to other kinds of mathematical approaches as well. My intention is not to suggest that scientific studies of mind should reject mathematical approaches. Rather, it should be made clear, which questions can be answered with the help of mathematical methods and which cannot.

Which Questions Can and Which Cannot be Answered by the Statistical Data Analysis Procedures?