Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Persistent anxiety among high school students: Survey results from the second year of the COVID pandemic

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Irvington High School, Irvington, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Roles Investigation

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies, NY State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Olivia Yin,

- Nadia Parikka,

- Amy Ma,

- Philip Kreniske,

- Claude A. Mellins

- Published: September 30, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275292

- Reader Comments

Introduction

National mental health surveys have demonstrated increased stress and depressive symptoms among high-school students during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, but objective measures of anxiety after the first year of the pandemic are lacking.

A 25-question survey including demographics, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7) a validated self-administered tool to evaluate anxiety severity, and questions on achievement goals and future aspirations was designed by investigators. Over a 2-month period, all students from grade 9–12 in a single high-school (n = 546) were invited to complete an online survey after electronic parental consent and student assent. Bi-variate and chi-square analyses examined demographic differences in anxiety scores and the impact on outcomes; qualitative analyses examined related themes from open-ended questions.

In total, 155/546 (28%) completed the survey. Among students with binary gender classifications, 54/149 (36%) had GAD-7 scores in the moderate or severe anxiety range (scores≥10), with a greater proportion among females than males (47% vs 21%, P<0.001). Compared to students with GAD-7<10, those with ≥ 10 were more likely to strongly agree that the pandemic changed them significantly (51% vs 28%, p = 0.05), made them mature faster (44% vs 16%, p = 0.004), and affected their personal growth negatively (16% vs 6%, p = 0.004). Prominent themes that emerged from open-ended responses on regrets during the pandemic included missing out on school social or sports events, missing out being with friends, and attending family events or vacations.

In this survey of high school students conducted 2 years after the onset of COVID-19 in the United States, 47% of females and 21% of males reported moderate or severe anxiety symptoms as assessed by the GAD-7. Whether heightened anxiety results in functional deficits is still uncertain, but resources for assessment and treatment should be prioritized.

Citation: Yin O, Parikka N, Ma A, Kreniske P, Mellins CA (2022) Persistent anxiety among high school students: Survey results from the second year of the COVID pandemic. PLoS ONE 17(9): e0275292. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275292

Editor: Ravi Shankar Yerragonda Reddy, King Khalid University, SAUDI ARABIA

Received: June 27, 2022; Accepted: September 13, 2022; Published: September 30, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Yin et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information file.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

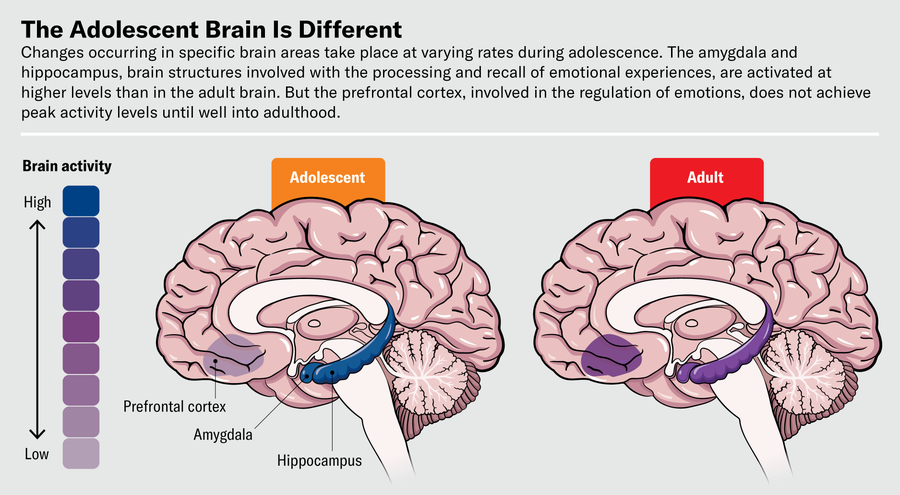

The long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of adolescents is still under investigation. A meta-analysis of 136 studies from various populations affected by COVID-19 found that at least 15–16% of the general population experienced symptoms of anxiety or depression [ 1 ]. The Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey (ABES) an online survey of a probability-based nationally representative sample of students in grades 9–12 (N = 7,705) collected from January-June of 2021 in the United States, found that 37% of students experienced poor mental health during the pandemic [ 2 ]. During the 12 months before the survey, 44% experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, 19.9% had seriously considered attempting suicide, and 9.0% had attempted suicide [ 2 ].

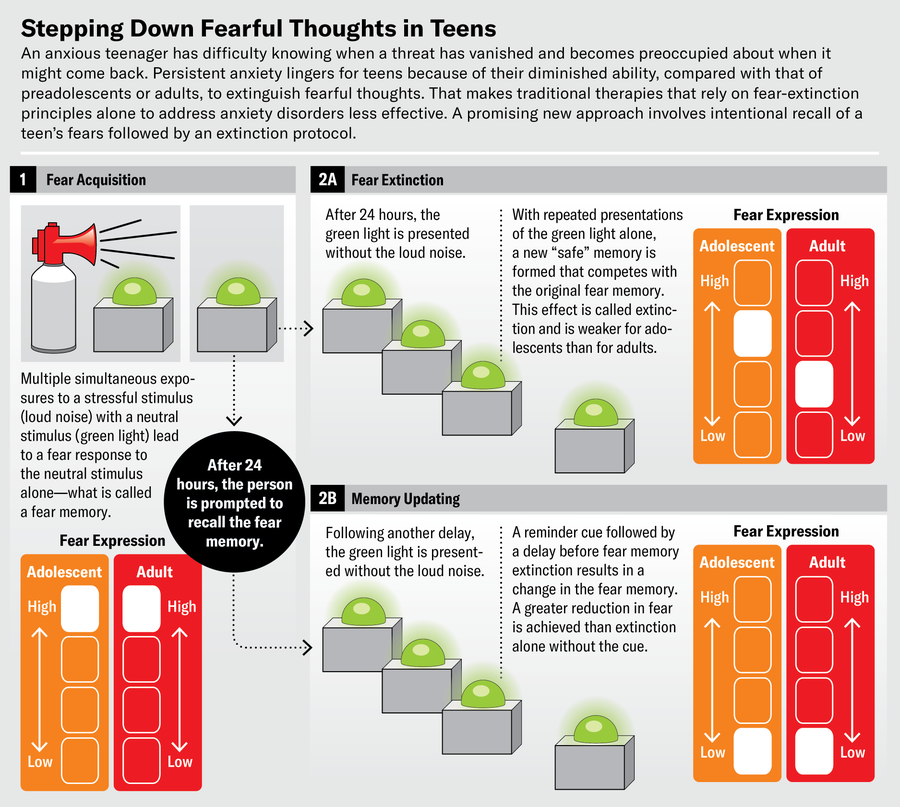

Adolescence is a development stage characterized by profound physiological, psychological and social change that could make them particularly vulnerable to stressful events [ 3 , 4 ]. Although fears of infection, sadness related to loss, and overwhelming uncertainty was experienced by people of all ages, the widespread disruption of education had profound effects on the mental health of children and adolescents [ 5 ]. Remote learning, restrictions placed on social gathering, cancellation or modification of sports or clubs, and in-school activities and events present major challenges for the education and social growth of young people. The disruption of school routines and isolation, loss of support from peers and teachers, not only makes learning difficult but can heighten the anxiety that adolescents already feel about their education and career [ 6 ]. Even before the pandemic, there were reports of increases in anxiety, depression, substance use among adolescents faced with excessive pressures to excel in affluent settings [ 7 ]. Social support from other students and teachers, especially during stressful times, is critical for the social-emotional well-being of adolescents and for sustaining academic engagement and motivation [ 8 – 10 ]. The COVID Experiences Survey, a nationwide survey of 567 adolescents in grades 7–12 performed in 2020, found that adolescents receiving virtual instruction reported more mentally unhealthy days, more persistent symptoms of depression, and a greater likelihood of considering suicide than students in other modes of instruction [ 11 ].

The Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey and COVID Experiences Survey both assessed level of stress, symptoms of depression and consideration of suicide among high school students but did not specifically include an evaluation of anxiety [ 2 , 11 ]. Several smaller published surveys of mental health among adolescent high school students in the United States included assessments of anxiety, although not all of them included validated measures of anxiety or examined the consequences of heightened anxiety [ 12 , 13 ]. In addition, all were performed in 2020, during the first wave of the infection. To our knowledge, few if any studies have examined longer-term consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent anxiety using validated tools. The goal of this study was to evaluate the longer-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on generalized anxiety in high school students using the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), a validated self-report measure, at the end of 2021. Variations by gender and the impact of anxiety on achievement goals, future aspirations and outlook of students were also explored.

Materials and methods

Study design.

This study was conducted at a single public high school in Westchester County of the State of New York. New York was one of the epicenters during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in the United States with a peak daily infection rate of over 9,000 cases/day in April 2020. In response to the New York State Education Department Executive Order, the high school was closed to in-person learning in March 2020 and transitioned to online classes (remote learning). The school remained closed to in-person learning for the remainder of the academic year. After summer break, the school re-opened with remote learning and provided the option for students to return to hybrid learning on October 7, 2020. Hybrid learning consisted of in-person school for half the week and remote learning for the other half of the week with half the capacity of students in the school at any given time. The school also allowed students to continue with full-time remote learning. This decision was made to balance the benefits of in-person learning with safety guidelines by reducing the total number students in school at any given time. On April 7, 2021, the school transitioned from hybrid learning to 100% in-person learning for the remainder of the academic year but still allowed students the option of remote learning. On September 7, 2021, the school re-opened after summer break to 100% in-person learning for all students without the remote learning option. The decision to transition to in-person learning for all students in September 2021 was based upon the low case rates of COVID and the availability of COVID vaccination. The FDA announced the emergency use authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for individuals 16 years of age and older on December 11, 2020 and for individuals 12 years of age and older on April 9, 2021.

Participants

A total of 521 students were enrolled in the high school, with the following numbers of students in each grade: 142 in 9 th ,130 in 10 th , 120 in 11 th and 128 in 12 th grade. The student body composed of 242 females and 279 males, with the following racial/ethnic distribution: 79% White, 13% Asian, 7% Black/African American, 1% American Indian/Native American. This non-selective public high school is the only high school in town. For context, the racial distribution of Westchester County was 73% White, 7% Asian, 17% Black in the 2019 census, with a median household income (in 2019 dollars) of $96,610 and 49% of the population over 25 years having a bachelor’s degree or higher. In the same period, the median household income in the United States was $68,703 with 22.5% of population age 25 and older having bachelor’s degree or higher.

The Irvington School Board approved the survey instruments and the overall study. All students attending the high school in 9 th -12 th grade were eligible to participate. Participation was voluntary, each survey question was optional, and there were no incentives for completion of survey. All participants completed an electronic parental consent and student assent prior to performing the online survey. A survey link was posted by the science teachers on the science classroom pages for all eligible students to complete on November 24, 2021. Science teachers continued to promote the survey until its closure on January 13, 2022.

Study instruments

The survey was conducted online via Google Forms software (version 2018) in English, and contained 25 questions, 23 of which were multiple choice. Participants took approximately 10–15 minutes to complete the survey. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7), a validated 7-item self-administered tool to evaluate anxiety severity, was utilized to measure anxiety [ 14 ]. GAD-7 has been utilized in adolescents and demonstrates an acceptable specificity and sensitivity for detecting clinically significant anxiety symptoms in comparison to the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale [ 15 ]. Participants are asked how often they were bothered by each of the following symptoms during the last 2 weeks with a 4-point scale ranging from “not at all” (0 points) to “nearly every day” (3 points): feeling nervous, anxious or on edge; not being able to stop or control worrying; worrying too much about different things; trouble relaxing; being so restless that it is hard to sit still; becoming easily annoyed or irritable; feeling afraid as if something awful might happen. The total score indicates the level of anxious symptoms ranging from minimal/no anxiety (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14) and severe (≥15).

Demographic data were collected, including current grade (9–12), gender (female, male, transgender man, transgender woman, non-binary, other), race (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, other), whether attending school by hybrid or remote learning, and COVID-19 vaccination status (none, partial or full series).

Several questions were developed by the study team through an iterative process that included initial development of question by the student researcher, refinement of wording by all investigators including experts in adolescent development and cognition, and testing for comprehension and clarity through review by 2 additional students. Four questions on whether students had more anxiety upon return to in-person learning in April 2021 (after hybrid or remote learning) or September 2021 (after summer break), and factors associated with the anxiety associated with in-person learning were assessed. Thirteen questions were included to assess importance of relationships, safety, achievements and future aspirations (5-point Likert scale from very important to not important): having friends/socializing; perception by friends; making parents proud; maintaining family relationships; good health (not getting COVID); feeling safe; getting good grades; graduating high school; attending college; becoming famous; having adventure; having money/wealth; and having your own family. One additional question addressed outlook on future (5-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree): “I think I will have more opportunities in life than my parents.” Three questions designed by the team assessed the impact of COVID-19 (5-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree): “The COVID-19 pandemic has changed me significantly”; “The COVID-19 pandemic has made me mature faster”; Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected my personal growth negatively.”

Two additional open-ended questions were included to allow students to reflect upon opportunities lost and gratitude experienced during COVID-19: “Share one moment that you regret missing out on during the COVID-19 pandemic,” and “Share one moment when you felt grateful during the COVID-19 pandemic”

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis..

Overall frequencies for demographics, GAD-7, and responses to questions on the importance of relationships, safety, achievements and opportunities were examined. Bivariate analyses by demographics characteristics (gender, grade, and learning type) were conducted with each response. Chi-square tests were conducted to determine whether responses differed by gender, grade, learning type, and severity of anxiety. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Mac, version 28.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, USA).

Qualitative analysis.

The answers to each open-ended question were evaluated for themes. The iterative process took the form of a data analysis spiral such that following data collection, the data was organized, read and notated for emerging ideas, described and classified by thematic codes, assessed and interpreted, and presented in this research report [ 16 ]. Author 1 read all the responses and compiled the data and created preliminary thematic codes. Author 2 reviewed the thematic codes and believed that thematic saturation had been reached. Author 1 then discussed all preliminary codes with all authors who provided additional memos. Representative excerpts for each theme are presented in Table 4 . Data saturation was defined using the grounded theory standpoint by Urquhart, that defined saturation as “the point in coding when you find that no new codes occur in the data. There are mounting instances of the same codes, but no new ones”[ 17 , 18 ].

Among the 546 students enrolled in the high school, 155/546 (28%) completed the survey, including 90 females, 59 males, and 6 students who did not identify as gender binary. Since the number of gender non-binary students was too small to include as a separate group in analyses looking at gender differences, results were presented only for students who self-identified as either female or male (n = 149) ( Table 1 ). The proportion of respondents was greater among females (90/262, 34%) than males (59/284, 21%). The response rates were much lower in 12 th grade (25/137, 18%) than in 9 th grade (61/139, 44%). The students were mostly White (69%), Asian (16%) or multi-racial (9%), predominantly engaged in hybrid learning (86%), and almost all (97%) fully or partially vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 at the time of survey completion ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275292.t001

Overall, 54/149 (36%) of the students had GAD-7 scores in the range for moderate or severe anxiety (scores≥10), with a greater proportion of the females than males experiencing moderate/severe anxiety (47% vs 21%, X 2 = 21.3984, P<0.001) ( Table 2 ). Among students who answered yes to any of the GAD-7 questions, 3% reported that anxiety made it extremely difficult and 12% reported that anxiety made it very difficult to do their work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people. More females than males (19% vs 7%, p<0.01) reported that anxiety made it very or extremely difficult to do their work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people ( Table 2 ). Severity of anxiety did not differ between students in the lower (9 th and 10 th ) versus the upper (11 th and 12 th ) grades. Severity of anxiety also did not differ between students engaged in hybrid versus remote learning ( Table 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275292.t002

More females than males felt anxious returning to in-person school in April 2021 (52% vs 27%; X 2 = 9.3457, p = 0.002) ( Table 1 ). COVID-19 vaccinations were available for individuals 16 years of age or older by December 2020 with emergency use authorization for individuals 12 years of age and older only granted on April 9, 2021. All of the major factors contributing to anxiety measured were more frequently reported in females than males: fear of getting COVID-19 (26% vs 15%), anxiety toward social interactions (20% vs 8%), and schoolwork (10% vs 5%). By September 2021, 51% of females and 44% of males reported feeling less anxious for in-person school than in April 2021. The primary reasons reported for decreased anxiety were the receipt of COVID-19 vaccinations (38%) and normalization of social interactions with in-person school (16%) ( Table 1 ).

Overall, 34% of students strongly agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic “changed me significantly” and 24% strongly agreed that it “made me mature faster” ( Table 3A ). However, only 8% of students strongly agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic “has affected my personal growth negatively.” More females reported that COVID-19 affected their personal growth negatively, but it did not reach statistical significance (11% vs 5%, p = 0.15). In comparison to students with either mild anxiety or no anxiety (GAD-7<10), students with moderate to severe anxiety (GAD-7≥10) were more likely than students with either mild anxiety or no anxiety (GAD-7<10) to strongly agree that the COVID-19 pandemic changed them significantly (51% vs 28%, p = 0.05), made them mature faster (44% vs 16%, p = 0.004), and affected their personal growth negatively (16% vs 6%, p = 0.004) ( Table 3B ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275292.t003

We further explored whether moderate/severe anxiety affected students’ outlook on relationships, safety, achievements, aspirations and opportunities. Over half of students reported the following life factors as very important: having friends/socializing (53%), maintaining good health and not getting COVID-19 (53%), getting good grades (62%), graduating high school (82%), and attending college (74%) ( Table 4 ). Females were more likely than males to regard the following factors as very important: money/wealth (28% vs 12%, p<0.01) and having your own family (39% vs 29%, p = 0.02), but did not differ from boys in other reported factors. Students with moderate to severe anxiety (GAD-7≥10) were more likely than students with mild or no anxiety to regard the following as very important: attending college (81% vs 70%, p = 0.04), becoming famous (9% vs 1%, p = 0.04), and having your own family (44% vs 31%, p = 0.01). Only 23% of students reported that they strongly agree with the statement “I will have more opportunities in my life than my parents”, without apparent differences by anxiety status ( Table 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275292.t004

In response to “share one moment that you regret missing out on during COVID-19 pandemic,” the following themes emerged, from most common to least common: missing out on school social events and sports; being with friends; family events and vacations, wasted new opportunities that were presented during COVID-19 pandemic, and celebrating milestones like bar mitzvahs, sweet-sixteens and birthdays. In response to “share one moment when you felt grateful during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the following themes emerged, from most common to least common: connecting with friends and family, health and safety, having time for personal development, moments during which there was a sense of return to normalcy, and the decreased stress of remote learning ( Table 5 ). Generally, the noted themes were similar in students with moderate-severe anxiety versus those with mild or no anxiety. However, in comparison to students with mild or no anxiety, more students with moderate-severe anxiety expressed that they regret missing out on being with friends, and less expressed regret for missing out on school-related social events such as the prom, school trips, or sports competitions. Notably, while all the students with moderate-severe anxiety reported missing out on something, 5% of students with either mild or no anxiety reported that they did not miss out on anything during the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, more students with moderate-severe anxiety expressed that they were grateful for health and safety and situations that provided a sense of normalcy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275292.t005

In one of the first reports on levels of anxiety in high school students during the second year of the COVID pandemic, this study found that 36% of the students reported moderate or severe anxiety, disproportionately affecting females. Although the GAD-7 is a screener for anxiety and meant to over detect, anxiety scores in this range are considered clinically meaningful and indications for further assessment and/or referral to a mental health professional for more definitive diagnoses. These surveys were completed in late 2021 at a point when over 95% of students had received partial or full vaccinations; therefore, our data suggest that the impact of COVID-19 on the generalized anxiety of high school students may be long-lasting.

Our findings are consistent with several large mental health surveys that included measures of anxiety were conducted on university students in 2020, earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic, and found that females were more likely to report moderate to severe general anxiety then males. The Healthy Minds Survey 2020, one of the largest studies of university students in the United States (N = 36,875), found that 32.2% of students reported moderate to severe anxiety, with a higher proportion in females than males (66.6% vs 28.6% of males) [ 19 ]. Similarly, a survey of over 69,000 university students in France found that females were more likely to report high levels of anxiety than males (30.8% vs 17.1%) [ 20 ].

As noted previously, the largest mental health surveys conducted among high school students in the United States did not specifically include an evaluation of anxiety [ 2 , 11 ], but anxiety was included in two smaller studies. Gazmararian et al. surveyed racial/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse students at 2 semi-rural public high schools in Georgia in 2020 and found that 25% of students were worried about the COVID-19 pandemic and a negative financial impact, with a similar gender difference in girls versus boys (29% vs 16%, p<0.0001) [ 13 ]. The Policy and Communication Evaluation (PACE) Vermont is an online cohort study of 212 adolescents (ages 12–17) and 662 young adults (ages 18–25) that completed questionnaires in the Fall of 2019 and 2020, before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 12 ]. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms measured by the GAD-2 increased from 24.3% to 28.4% among adolescents after COVID-19, similar to the increase from 35.3% to 42.3% observed among young adults [ 12 ].

In our study, 36% of high school students had moderate/severe anxiety by GAD-7, which is slightly higher than the prevalence in aforementioned high school studies, and similar to the prevalence among college students in the Healthy Minds Survey. Female high school students were more likely to report moderate or severe anxiety. Importantly, this study explored potential reasons for anxiety upon return to in-person learning in April 2021, informed by high school students (including lead author) and a greater proportion of females than males endorsed each category: COVID-19 (26% vs 15%), schoolwork (10% vs 5%) and social interactions (20% vs 8%). These data suggest that female high school students had higher anxiety levels not only because of fear of COVID, but also because of more normative stressors pre-COVID, such as school and social pressures. Furthermore, females reported more negative effects of their anxiety compared to boys, with 19% reporting that it is “extremely difficult to do their work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people” as compared to only 9% of males. Notably, severity of anxiety did not appear to differ between students in the lower (9 th and 10 th ) versus the upper (11 th and 12 th ) grades. This was unexpected given higher levels of stress associated with standardized testing and college applications in the upper grades. Severity of anxiety also did not differ between students engaged in hybrid versus remote learning ( Table 2 ). However, since most of the students were engaged in hybrid learning (87%), our power to detect differences was limited. Other investigators found no difference in risk for anxiety among students with remote versus in-person education [ 21 ]; however, the role of hybrid learning has never been adequately assessed.

Students who reported moderate/severe anxiety had very different responses than students with either mild or no anxiety regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Students with moderate/severe anxiety were far more likely to strongly agree that the COVID pandemic changed them (51% vs 28%), made them mature faster (44% vs 16%), and affected their personal growth negatively (16% vs 6%). It is possible that COVID-19 had a greater negative impact on these students resulting in higher anxiety levels, or that students with higher anxiety levels before the pandemic were more susceptible to the negative effects of COVID-19. This question cannot be addressed without pre-pandemic data on these students. However, it is interesting that even though students with moderate/severe anxiety perceived a greater negative impact of COVID-19, they did not differ from other students in their hopes and aspirations for the future. In fact, more students with moderate to severe anxiety responded that attending college, becoming famous, and having their own family was very important ( Table 4 ). This may also reflect a greater underlying expectation for success and a desire for safety and security among students with greater anxiety. This is an important area for future study. While students reported being concerned about good health and “not getting COVID-19,” less than half of the students (45%) rated “feeling safe” as very important. While these data may reflect the higher risk tolerance of adolescents in general vs other age groups, the data also suggest that the heightened awareness of safety measures for COVID-19 did not translate into generalized fear affecting other aspects of their lives. Overall, these data suggest that despite the relatively high proportion of students reporting anxiety, the majority did not perceive negative effects and thus appeared to be coping with the stressors of COVID-19.

This study was not designed for formal qualitative research, but there were two open-ended questions on regrets and gratitude. Missing out on school social or sports events was the most common theme, followed by missing out being with friends or attending family events or vacations. Several students also articulated missed opportunities for growth presented by COVID-19 and shared regrets for not accomplishing more with the extra time. Students shared their gratitude mostly for connecting with friends and family and for health and safety. There were also appreciations written for having a time for personal growth, moments during COVID-19 that provided a sense of normalcy, and the decreased stress from school that remote learning offered ( Table 4 ). Based upon exploratory analyses, it appeared that students with moderate-severe anxiety were more likely to regret missing out on being with friends, less likely to regret missing out on school social or sports events, and more likely to be grateful for health and safety. Further work could examine how these constructs may be important for adolescents experiencing moderate-severe anxiety.

There are now several longitudinal studies of change in mental health measures among children and young adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 22 ]. Several comprehensive studies of college and university students in the United States include data on pre-pandemic mental health, analyses of predictors, and a focus on serious psychiatric and alcohol/drug use outcomes [ 23 , 24 ], but data are lacking for high school students. Stamatis et al found that the disruption due to the pandemic and limited confidence in the government response were the main predictors of depression among college students [ 24 ]. Bountress et al found that COVID-19 worry predicted post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety even after adjusting for pre-pandemic symptom levels [ 23 ]. In addition, housing/food concerns predicted PTSD, anxiety and depression symptoms as well as suicidal ideation, after adjusting for pre-pandemic symptoms in college students [ 23 ]. Comprehensive longitudinal studies are necessary to assess the true impact of COVID on mental health in high school students. In particular, studies should assess whether symptoms are associated with serious clinical outcomes such as suicidal ideation, alcohol and substance misuse and missed milestones such as graduation from high school, admission to college, and employment.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study was the use of the well validated and extensively used GAD-7 to measure anxiety symptoms. There were no data on anxiety for the students prior to COVID-19 as a baseline for comparison nor measures of other indicator of mental health such as depression and suicidality. Other limitations of this study include the performance of the survey at a single high school—our sample size was limited and the analyses were performed on a convenience sample. While only 28% of the study body responded to the survey, this response rate was similar to the response rates of other high school surveys performed in the United States [ 12 , 13 , 25 ]. The lack of racial/ethnic diversity in the student population also limits generalizability to other populations of adolescents. We did not include potential risk factors elicited in other studies such as prior psychiatric history, financial hardship, or illness in family in our survey. We were also unable to evaluate the impact of hybrid versus remote learning on anxiety, since very few of our students chose remote learning. Lastly, the survey questions we created were done so because nothing specifically existed for this age group, the newness of COVID, and the need to implement questions quickly; therefore, we did not utilize a formal validation process.

In this survey of high school students performed almost 2 years after the onset of COVID-19 in the United States, a relatively high proportion reported moderate or severe anxiety symptoms as assessed by the GAD-7. Our data suggest that the negative impact of COVID-19 on the anxiety levels of high school students may be long-lasting. Whether the heightened anxiety results in functional deficits is still uncertain, but resources for assessment and treatment should be prioritized.

Supporting information

S1 dataset..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275292.s001

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 16. Cresswell J, Poth C. Qualitiative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. California: SAGE 2018.

- 17. Urquhart C. Grounded Theory for Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2013.

- Open access

- Published: 01 August 2023

Stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms among international students: a sequential mediation model

- Yue Wang 1 , 2 ,

- Xiaobin Wang 1 ,

- Xuehang Wang 3 ,

- Xiaoxi Guo 3 ,

- Lulu Yuan 4 ,

- Yuqin Gao 4 &

- Bochen Pan 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 23 , Article number: 556 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5304 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Anxiety is a common mental health problem among university students, and identification of its risk or associated factors and revelation of the underlying mechanism will be useful for making proper intervention strategies. The aim of our study is to test the sequential mediation of self-efficacy and perceived stress in the association between stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms.

A cross-sectional study design was adopted and a sample of 512 international students from a medical university of China completed the survey with measurements of stressors in university life, self-efficacy, perceived stress and anxiety symptoms.

We found that 28.71% of the international students had anxiety symptoms, and stressors in university life were positively associated with anxiety symptoms ( β = 0.23, t = 5.83, p < 0.01). Moreover, sequential mediating role of self-efficacy and perceived stress in the association between the stressors and anxiety symptoms was revealed.

Conclusions

Our study provided a new perspective on how to maintain the mental health, which suggested that self-efficacy improvement and stress reduction strategies should be incorporated in the training programs to support students.

Peer Review reports

There has been an increasing interest in mental health of university students, and one of the growing concerns is the high prevalence of stress and anxiety in this population [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. According to the WHO survey project about mental health problems in university students, generalized anxiety was highly prevalent in students across countries [ 5 ]. As anxiety can seriously affect students’ social function, academic achievement or even physical health, efforts should be made to identify its risk factors and illuminate the mechanism of interactions so that proper intervention strategies may be made. International students are a special population in universities, because they may have to deal with the culture differences and encounter more difficulties. Thus, their mental health is of great concern. However, studies focusing on the mental health of international students in China have been limited.

Relationship between stressors and anxiety symptoms

Studies suggest that stress is one of the risk factors for anxiety [ 6 ]. Higher levels of stress among university students have been found associated with mental health problems [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. There are many sources of stress that university students may experience, and the students must learn to balance the competing demands. Demands on an individual made by the external or internal environmental stimuli that affect the balance are defined as stressors [ 10 ]. In recent years, more and more researchers begin to focus on the stressors that university students are facing and the coping strategies students adopt. Stressors encountered by university students are categorized differently in different studies, but some major sources have been well recognized, such as the health issues, environmental problems, academic difficulties, financial pressure and interpersonal relation problems [ 11 , 12 ]. Among these sources, academic difficulties were viewed as the primary sources of stress and were shown contributing to a variety of mental health problems in many researches [ 13 , 14 ]. For international students, however, the stressors might be different, because they may face issues different from those of their domestic peers. Therefore, studies specific on the stressors perceived by international students are needed. In this study, based on the above observations, our first hypothesis (H1) is: Stressors in university life are positively and significantly associated with anxiety symptoms among international students.

However, researches have shown that the same stressors to one individual may not be stressful to another. Other factors may also contribute to the process. Lazarus and colleagues described this phenomenon in their transactional model of stress, and they pointed out that cognitive appraisals play an important role in the process to determine the presence or the severity of a stressor [ 15 ]. In this model, stress is defined as a transaction between an individual and the environment, and is generated by subjective cognitive judgement of the potential impact of a stressor on future functioning [ 16 ]. The process begins when a stressor represents a threat (primary appraisal) that activates a cognitive process for the individual to assess the degree of harm or loss, and then leads to a secondary appraisal in which the individual evaluates his or her resources to cope with the stressor. A stress response is elicited when the perceived demands outweigh the perceived resources. Therefore, it is the character of the individual rather than the environment that makes a difference in the meaning of a stressor. In addition, stress outcomes were known to involve physiological, emotional, behavioral and cognitive reactions [ 15 ].

Relationships among stressors, self-efficacy and anxiety symptoms

Self-efficacy is grounded in the social cognitive theory which emphasizes that the individual regulates his or her motivation and behavior through self-assessment [ 17 ]. General self-efficacy is defined as the degree to which individuals believe they are capable of dealing with challenging situations and is the mechanism through which individuals apply their existing knowledge and experience [ 18 ]. If individuals have a strong sense of self-efficacy, they will trust their ability to actively control stressors in the environment, which will motivate them to take action [ 19 ]. This is very similar to the appraisal concept in the transactional model of stress [ 19 ]. Studies revealed that the lower level of self-efficacy was related to mental disorders [ 20 , 21 ]. This may be true for the university students as students with more anxiety symptoms showed lower level of self-efficacy [ 22 , 23 ]. Individuals with higher levels of self-efficacy tend to experience more positive emotions, whereas those with lower levels of self-efficacy are more likely to experience more anxiety [ 24 ]. A possible explanation is that people who have lower perception of self-efficacy to control life and thoughts cannot help but be anxious at the thought of how to deal with the stressors [ 19 ]. Therefore, self-efficacy appears to be an effective protective factor against the negative psychological effects such as anxiety induced by stressors, and thus we propose the following hypotheses: (H2) Stressors in university life are negatively and significantly associated with self-efficacy among international students; (H3) Self-efficacy is negatively and significantly associated with anxiety symptoms among international students; (H4) Stressors in university life have a significant indirect effect on anxiety symptoms via self-efficacy among international students.

Relationships among stressors, perceived stress and anxiety symptoms

Appraisal or perception of stress is another factor that may mediate the association between the stressors and psychological responses. Based on the transactional model of stress, stress represents an imbalance between abilities of individuals and demands of environment, and the results of the transaction could lead to negative psychological outcomes [ 15 ]. Therefore, the effect of stressors depends on the perception of stress [ 16 ]. Some study results confirmed the presence of such a mechanism. For example, McCuaig Edge investigated the impact of combat exposure on psychological distress of military personnel and found the mediation effect of cognitive appraisal in the association [ 25 ]. Besharat et al. conducted a survey regarding anxiety among Iranian university students, and found that perceived stress played a mediating role in the association between facing existential issues and anxiety [ 26 ]. Zhang et al. examined the relationships of sleep quality and anxiety/depression among nursing students of a public university in the United States, and found that perceived stress not only mediated the association between sleep quality and anxiety symptoms, but also the association between sleep quality and depression symptoms [ 27 ]. These results strongly suggest that the appraisal or perception of stress can be the factor that determines whether the stressors will result in psychological responses or not. As a result, we posit the following hypotheses: (H5) Stressors in university life are positively and significantly associated with perceived stress among international students; (H6) Perceived stress is positively and significantly associated with anxiety symptoms among international students; (H7) Stressors in university life have a significant indirect effect on anxiety symptoms via perceived stress among international students.

Relationship between self-efficacy and perceived stress

A review of the literature related to self-efficacy and stress revealed a significant relationship between individuals’ self-efficacy and their effectiveness in coping with stress [ 24 ]. Self-efficacy is related to experiencing less negative emotions in risky situations and appraising the stressors as challenges rather than threats [ 20 ]. Individuals with higher level of self-efficacy believe they are capable of dealing with their demands, and this belief may result in adopting positive approaches and perceiving less stress in life. According to the transactional model of stress, self-efficacy may play a significant role in the primary and secondary appraisals which will lead to a decline in perceived stress, and then result in less negative psychological outcomes. Thus, we posit the following hypotheses: (H8) Self-efficacy is negatively and significantly associated with perceived stress among international students; (H9) Stressors in university life have a significant indirect effect on anxiety symptoms via self-efficacy and then perceived stress among international students.

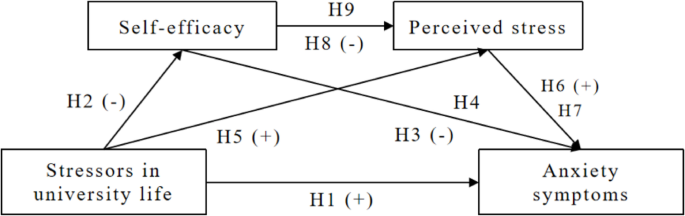

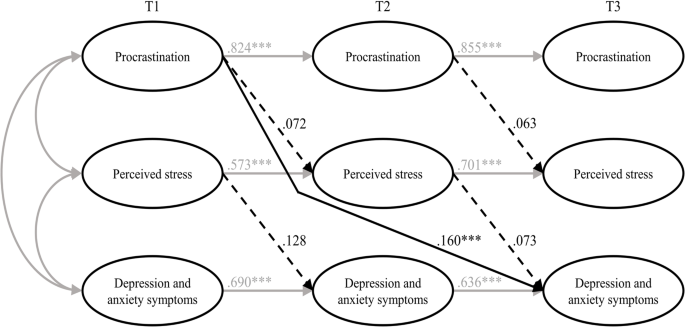

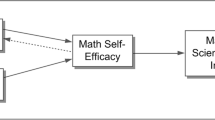

Based on the above mentioned theoretical assumptions and research results, we have constructed the conceptual framework of this study (Fig. 1 ). We hope that this conceptual framework will become the theoretical basis for exploring intervention measures to prevent or manage mental health problem such as anxiety for the international students.

Conceptual framework of this study

Study design and subjects

The present study was a cross-sectional design and a cluster sampling was adopted. Data were collected from the international students of China Medical University in November 2020. The inclusion criteria of the potential participants were (1) able to get access to internet, (2) a current student of the University, (3) able to read, fully understand and answer the survey questions. One thousand and fifteen students who met the inclusion criteria were initially contacted via electronic email. Then, in the online survey, there was a brief explanation about the study, and the participants were asked to complete an informed consent agreement, in which they were made aware that participation was completely voluntary. Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University approved our study (2020–25), and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Finally, a total of 543 international students participated, and 512 of them were able to complete the questionnaires. The overall response rate was 50.44%.

Measurements

Measurement of anxiety symptoms.

The anxiety symptoms were measured with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of seven items for observing the frequency of anxiety symptoms with a four-point Likert scale from 0 “not at all” to 3 “almost every day” [ 28 ]. The anxiety level is reflected by the total score, where higher scores indicate more symptoms of anxiety. Scores of 5, 10 and 15 represent the cutoffs for mild, moderate and severe anxiety symptoms, respectively [ 29 ]. Previous studies have demonstrated the GAD-7 has high reliability as well as good criterion and construct validity [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.92.

Measurement of stressors in university life

Stressors in university life of international students were measured by 7 questions regarding (1) health problems, (2) financial pressure, (3) academic difficulties, (4) interpersonal relation difficulties, (5) daily life difficulties, (6) adverse life events and (7) language barrier [ 11 , 12 ]. Participants answered 1 (not at all) to 4 (very serious) to the questions. The total score represents the severity of the stressors perceived by the participant. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 was found for the scale in this study.

Measurement of self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was assessed with the General Self-efficacy Scale (GSES), which is a 10-item measure of an individual’s confidence in his or her ability to deal with stressful situations [ 34 ]. Items are scored on a four-point Likert-type scale ranges from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (exactly true), and responses are calculated to yield a total score of all item scores where higher scores indicate higher levels of self-efficacy. The GSES has good psychometric properties, and many studies have confirmed its internal consistency reliability, convergent and discriminant validity [ 35 , 36 ], demonstrating that GSES is a reliable and valid measurement. The Cronbach’s alpha for GSES in the present study was 0.95.

Measurement of perceived stress

Perceived stress was evaluated by the 10-item version of Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), which is a self-report measure designed to assess the extent to which participants appraise their lives to be stressful [ 37 ]. Each item is rated on a 0 (never) to 4 (very often) Likert scale by the respondent to indicate how often the participant experienced specific feelings or thoughts. The total scores of the measure are obtained by adding the score of each item (4 items are reverse-scored) to provide a continuous measure of perceived stress, and higher scores indicate greater perceived stress. PSS-10 has demonstrated strong psychometrics. Its coefficient alpha reliability ranged between 0.84 and 0.91 in previous studies [ 6 , 38 ], and in this study it was 0.87.

Demographic characteristics

Age, gender, current place of residence (Asia/Africa/North America/Europe/Oceania) and educational background were investigated for demographic characteristics.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 17.0 was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics including frequency distributions for the nominally scaled demographic variables provided a profile of the sample. We found the scores of GAD-7 were not normal distribution after testing the normality for continuous variables. Therefore, Mann–whitney U test was conducted to determine if the groups were statistically equivalent on anxiety symptoms. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to examine relationships between continuous variables.

The sequential mediation was tested using PROCESS macro program for SPSS [ 39 ], which facilitated path analysis-based mediation analyses. We verified the hypothesis model by the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method, with 5000 resampled samples. 95% confidence intervals for the mediation effects were estimated and the results were considered significant when the 95% confidence interval did not include zero. We generated direct effect of stressors in university life on anxiety symptoms and indirect effects of stressors in university life on anxiety symptoms through the mediators (self-efficacy and perceived stress) in the mediation using the model 6 of PROCESS. There were three routes of indirect effects in the sequential mediation model. When the direct effect became non-significant but the indirect effect was significant, full mediation was established. Partial mediation was confirmed if both effects are significant [ 40 ]. Continuous variables were all centralized before the model was validated to avoid multicollinearity. Two-tailed alpha 0.05 was used for significance testing purposes.

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics of the sample are shown in Table 1 . Overall, 147 (28.71%) students had anxiety symptoms, including 93 (18.16%) mild, 33 (6.45%) moderate and 21 (4.10%) severe cases.

Severity of stressors

Stressors and their severity perceived by the international students are presented in Table 2 . Financial pressure and language barrier were the most prominent stressors affecting 72.07% and 69.34% of the students, respectively.

Differences of anxiety symptoms in categorical variables

The differences of GAD-7 scores in categorical variables are shown in Table 3 . There was no difference between the groups.

Correlations among continuous variables

The correlations among continuous variables are shown in Table 4 . Age, stressors in university life, perceived stress and self-efficacy were all significantly correlated with GAD-7 score. In addition, stressors in university life and PSS-10 negatively correlated with GSES. Finally, stressors in university life positively correlated with PSS-10, while age negatively correlated with PSS-10.

Results of the sequential mediation model testing

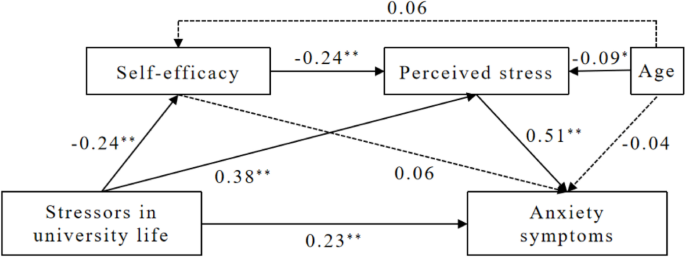

The results of regression analyses are listed in Table 5 . After controlling for age, stressors in university life were negatively associated with self-efficacy ( β = -0.24, t = -5.51, p < 0.01) and positively associated with perceived stress ( β = 0.38, t = 9.68, p < 0.01) and anxiety symptoms ( β = 0.23, t = 5.83, p < 0.01). The association between self-efficacy and perceived stress was also significant ( β = -0.24, t = -6.13, p < 0.01), but not in the association between self-efficacy and anxiety symptoms. Perceived stress had a positive and the strongest association with anxiety symptoms ( β = 0.51, t = 12.85, p < 0.01), because the standardized regression coefficient was the largest in the model. Figure 2 represents the model plot after the testing.

Sequential mediation model result. Notes: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

The direct, indirect and total effects in the sequential mediation model are shown in Table 6 . In the proposed model, stressors in university life impacted anxiety symptoms through four possible routes. The direct effect of stressors in university life on anxiety symptoms (route 1) was 0.32 with 95% bias-corrected CIs [0.21, 0.43] above 0, which was an indication of significance. The mediating effect of self-efficacy (route 2) was not significant, because the 95% bias-corrected CIs [-0.05, 0.01] included 0. Thus, self-efficacy did not play a mediating role in the association between stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms. The mediating effect of perceived stress (route 3) was 0.28 with 95% bias-corrected CIs [0.20, 0.36] excluding 0, supporting the positive mediating effect of perceived stress in the relationship between stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms. Similarly, the sequential mediating effect of self-efficacy and perceived stress (route 4) was 0.04 with 95% bias-corrected CIs [0.02, 0.07] excluding 0, representing the sequential mediating effect of self-efficacy and perceived stress in the relationship between stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms.

Previous studies mainly focused on the cross-cultural adaptation of international students, but less on the stressors and related stress responses. In our study sample, the mean scores of PSS-10 was 16.53, which is lower than the local students in Turkey (18.03) [ 41 ], Saudi Arabia (20.10) [ 42 ] and China (21.13) [ 43 ]. In addition, 28.71% of the international students had anxiety symptoms in the present study, which is also lower than the domestic Chinese students (46.85%) [ 43 ] and Libyan students (64.50%) [ 44 ]. A possible reason may be that the participants in our study all come from a medical university, and they may already have certain amount of knowledge on mental health. It is also possible that the measures taken by their university to manage the stress have been effective.

Our study showed that financial pressure and language barrier were the most serious stressors in university life among international students, which were different from the findings demonstrating that academic difficulties were the primary sources of stress in university students. As pointed out by Grable and Joo, the students who face financial crisis tend to be more likely to drop out of the university or achieve lower grades than others [ 45 ], which may cause serious stress to the students. The importance of financial pressure to international students in our study was in line with the previous studies on international students which indicated that the financial pressure was a particular concern and at higher risk for problem of mental health [ 46 , 47 ]. Language insufficiency has also been found to be a critical stressor that international students encounter in other studies, because language proficiency was essential in international students’ sociocultural adjustment [ 48 , 49 ]. In this situation, the students may face concomitant problems such as lack of confidence and low self-efficacy, again causing higher level of stress. This finding consisted with the results in previous studies which proved language deficit was a significant source of stress among international students [ 50 , 51 ]. Furthermore, in our study, stressors in university life were found positively associated with anxiety symptoms of international students ( β = 0.23, t = 5.83, p < 0.01), which supported H1 and was consistent with other studies [ 52 ]. Since the students are exposed to various stressors in university life to different extent and it may not be possible to remove the stressors from their roots, understanding the internal mechanism becomes very important in order to reduce the adverse effect of stressors in university life and maintain the mental health of students.

In the present study, stressors in university life were negatively associated with self-efficacy ( β = -0.24, t = -5.51, p < 0.01) and positively associated with perceived stress ( β = 0.38, t = 9.68, p < 0.01), which supported H2 and H5. Self-efficacy was negatively associated with perceived stress ( β = -0.24, t = -6.13, p < 0.01), and perceived stress was positively associated with anxiety symptoms ( β = 0.51, t = 12.85, p < 0.01), which supported H8 and H6. Unexpectedly, sequential mediation model testing didn’t show a direct effect of self-efficacy on anxiety symptoms nor an indirect effect of self-efficacy in the association between stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms. Therefore, H3 and H4 were not supported, which indicated that the association of self-efficacy with anxiety symptoms was not direct, similar with the findings from a study on medical college students in Philippines [ 53 ]. Instead, self-efficacy played a sequential mediating role with perceived stress in the association between stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms, which supported H9 and indicated self-efficacy’s direct relationship with perceived stress rather than anxiety symptoms. Although the sequential mediation effect accounted only for 12.5% of the total mediation effect, it still implied that the impact of self-efficacy on anxiety symptoms was generated through perceived stress. This result supported the transactional model of stress. It also indicated that self-efficacy was an effective protective factor against stress. Individuals who have lower levers of self-efficacy do not have enough confidence and the ability to cope with the external and internal environment. They will perceive more severe stressors and stress, and are more prone to show anxiety symptoms. Self-efficacy improvement interventions in previous researches have shown that the methods were effective in empowering participants to cope with stress [ 22 , 24 , 54 , 55 , 56 ].

Another finding of our study was the partial mediation effect of perceived stress in the association of stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms among international students, which supported H7. Perceived stress alone accounted for 87.50% of the total mediation effect and 43.75% of the total effect. Its strong effect indicated its important role in facilitating translation of stressors in university life into anxiety symptoms, and this is in line with other studies that assumed appraisals were important determinants of adjustment to stressful encounters [ 57 ]. Previous empirical researches have shown similar findings of the mediation effect of perceived stress [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Combined with our findings of self-efficacy as a protective factor against stress, interventions can be considered using self-efficacy training to alleviate perceived stress and promote the positive appraisal on stressors in university life to reduce anxiety symptoms. There already have been some researches of stress management among university students using cognitive behavioral therapy which have achieved a significant reduction in perceived stress and anxiety symptoms after the intervention, with the enhancement of self-efficacy as well [ 17 ].

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Given the cross-sectional design, it’s unable to make any assertions regarding causation. A further experimental design of study in the future should be employed to determine causal relationships. Another limitation is that there may have been response biases in the self-report of the individuals completing the measures. Finally, as most of the participants were from Asia, the results in this study may not apply equally well to the students in other part of the world. Future research could expand the diversity of the university types to better capture the students from other part of the world.

Despite of the limitations, this study has discovered the sequential mediating role of self-efficacy and perceived stress in the association between stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms, and provided a new perspective on how to maintain mental health for international students. The sequential mediators provides a deeper insight into the underlying mechanism of stressors in university life towards anxiety symptoms among international students. At the same time, this study has broadened the application scope of self-efficacy in the field of stress research, and is also an empirical contribution to the theory of transactional model of stress using in the population of international students. In addition, our study shows that identification and evaluation of stressors in university life are important, and financial pressure and language barrier should be given more attention for international students. This would be valuable in ensuring implementation of stress reduction programs to effectively support students. Given that few studies on university life stressors exist in the literature of international students, our study is very important because it has filled in the gap. As for practical implications, our study findings may apply to all the international students who have poor self-efficacy or perceive higher levels of stress or are struggling with anxiety. Therefore, counselling focusing on financial pressure and language barrier, as well as introduction of specific interventions into university campus for international students should be encouraged, and the university educators should utilize self-efficacy improvement and stress reduction measures in the training programs to support students.

Our study has identified the financial pressure and language barrier as the most important university life stressors for international students. The findings have also confirmed the direct positive association between stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms, as well as the positive association between perceived stress and anxiety symptoms, and revealed the sequential mediating role of self-efficacy and perceived stress in the association between stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms. Results of our study indicate that in order to maintain the mental health of international students, counselling concerning finance and language and interventions with self-efficacy improvement and stress reduction should be involved in the training programs within the university campus.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the protection of participants' privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item

General Self-efficacy Scale

10-Item version of Perceived Stress Scale

Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, Sammut S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:90–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Keyes CLM, Eisenberg D, Perry GS, Dube SR, Kroenke K, Dhingra SS. The relationship level of positive mental health with current mental disorders in predicting suicidal behavior and academic impairment in college students. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(2):126–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.608393 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Klein MC, Ciotoli C, Chung H. Primary care screening of depression and treatment engagement in a university health center: a retrospective analysis. J Am Coll Health. 2011;59(4):289–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.503724 .

Xiao H, Carney DM, Youn SJ, Janis RA, Castonguay LG, Hayes JA, Locke BD. Are we in crisis? National mental health and treatment trends in college counseling centers. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(4):407–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000130 .

Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P, Demyttenaere K, Ebert DD, Green JG, Hasking P, Murray E, Nock MK, Pinder-Amaker S, Sampson N, Stein DJ, Vilagut G, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC, WHO WMH-ICS Collaborators. WHO world mental health survey international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127(7):623–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pereira-Morales AJ, Adan A, Forero DA. Perceived stress as a mediator of the relationship between neuroticism and depression and anxiety symptoms. Curr Psychol. 2019;38(1):66–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9587-7 .

Article Google Scholar

Dixon S, Kurpius S. Depression and college stress among university undergraduates: do mattering and self-esteem make a difference? J Coll Stud Dev. 2008;49(5):412–24. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0024 .

Misra R, McKean M, West S, Russo T. Academic stress of college students: comparison of student and faculty perception. Coll Stud J. 2000;34(2):236–45.

Google Scholar

Struthers CW, Perry RP, Menec VH. An examination of the relationship among academic stress, coping, motivation and performance in college. Res High Educ. 2000;41:581–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007094931292 .

Lazarus RS, Cohen JB. Environmental Stress. In: Altman I, Wohlwill JF, editors. Human Behavior and Environment. New York: Plenum Press; 1977. p. 89–127.

Chapter Google Scholar

Rajasekar D. Impact of academic stress among the management students of AMET University-an analysis. AMET J Manag. 2013;5:32–9.

Ross SE, Neibling BC, Heckert TM. Sources of stress among college students. Coll Stud J. 1999;33(2):2–9.

Kamardeen I, Sunindijo RY. Stressors impacting the performance of graduate construction students: comparison of domestic and international students. J Prof Iss Eng Ed Pr. 2018;144(4):4018011. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EI.1943-5541.0000392 .

Misra R, McKean M. College student’s academic stress and its relation to their anxiety, time management and leisure satisfaction. Am J Health Stud. 2000;16(1):41–52.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. 1st ed. New York: Springer; 1984.

Lazarus RS. Psychological stress and the coping process. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1966.

Jafar HM, Salabifard S, Mousavi SM, Sobhani Z. The effectiveness of group training of CBT-based stress management on anxiety, psychological hardiness and general self-efficacy among university students. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(5):47–54. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p47 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Larson LM, Daniels JA. Review of the counseling self-efficacy literature. Couns Psychol. 1998;26(2):179–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000098262001 .

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. 1st ed. New York: Worth Publishers; 1997.

Luszczynska A, Gutiérrez-Doña B, Schwarzer R. General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: evidence from five countries. Int J Psychol. 2005;40(2):80–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590444000041 .

Siu OL, Lu CQ, Spector PE. Employees’ well-being in greater China: the direct and moderating effects of general self-efficacy. Appl Psychol. 2007;56(2):288–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00255.x .

Ghaderi AR, Rangaiah B. Influence of self-efficacy on depression, anxiety and stress among Indian and Iranian students. J Psychosoc Res. 2011;6(2):231–40.

Razavi SA, Shahrabi A, Siamian H. The relationship between research anxiety and self-efficacy. Mater Sociomed. 2017;29(4):247–50. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2017.29.247-250 .

Houghton JD, Wu J, Godwin JL, Neck CP, Manz CC. Effective stress management a model of emotional intelligence, self-leadership, and student stress coping. J Manag Educ. 2012;36(2):220–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562911430205 .

McCuaig Edge HJ, Ivey GW. Mediation of cognitive appraisal on combat exposure and psychological distress. Milit Psychol. 2012;24(1):71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2012.642292 .

Besharat MA, Khadem H, Zarei V, Momtaz A. Mediating role of perceived stress in the relationship between facing existential issues and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Iran J Psychiatry. 2020;15:80–7. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijps.v15i1.2442 .

Zhang Y, Peters A, Chen G. Perceived stress mediates the associations between sleep quality and symptoms of anxiety and depression among college nursing students. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2018;15(1):20170020. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijnes-2017-0020 .

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 .

Zhang M, He Y. Handbook of rating scales in psychiatry. 1st ed. Changsha: Hunan Science & Technology Press; 2015.

Donker T, van Straten A, Marks I, Cuijpers P. Quick and easy self-rating of generalized anxiety disorder: validity of the Dutch web-based GAD-7, GAD-2 and GAD-SI. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188(1):58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.01.016 .

Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093 .

Rogers KD, Young A, Lovell K, Campbell M, Scott PR, Kendal S. The British sign language versions of the patient health questionnaire, the generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale, and the work and social adjustment scale. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2013;18(1):110–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/ens040 .

Ruiz MA, Zamorano E, Garcia-Campayo J, Pardo A, Freire O, Rejas J. Validity of the GAD-7 scale as an outcome measure of disability in patients with generalized anxiety disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2011;128(3):277–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.010 .

Scherbaum CA, Cohen-Charash Y, Kern MJ. Measuring general self-efficacy: a comparison of three measures using item response theory. Educ Psychol Meas. 2006;66(6):1047–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164406288171 .

Drescher CF, Baczwaski BJ, Walters AB, Aiena BJ, Schulenberg SE, Johnson LR. Coping with an ecological disaster: the role of perceived meaning in life and self-efficacy following the Gulf Oil Spill. Ecopsychology. 2012;4(1):56–63. https://doi.org/10.1089/ec0.2012.0009 .

Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol. 2005;139(5):439–57. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.139.5.439-457 .

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404 .

Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapam S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health: Claremont Symposium on applied psychology. London: Sage; 1998. p. 31–67.

Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav Res. 2007;42(1):185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316 .

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 .

Kaya C, Tansey TN, Melekoglu M, Cakiroglu O, Chan F. Psychometric evaluation of Turkish version of the perceived stress scale with Turkish college students. J Ment Health. 2019;28(2):161–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1417566 .

Manzar MD, Salahuddin M, Pandi-Perumal SR, Bahammam AS. Insomnia may mediate the relationship between stress and anxiety: a cross-sectional study in university students. Nat Sci Sleep. 2021;13:31–8. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S278988 .

Lu W, Bian Q, Song Y, Ren J, Xu X, Zhao M. Prevalence and related risk factors of anxiety and depression among Chinese college freshmen. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol. 2015;35(6):815–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11596-015-1512-4 .

Elhadi M, Buzreg A, Bouhuwaish A, Khaled A, Alhadi A, Msherghi A, Alsoufi A, Alameen H, Biala M, Elghewi A, Elkhafeefi F, Elmabrouk A, Abdulmalik A, Alhaddad S, Elgzairi M, Khaled A. Psychological impact of the civil war and COVID-19 on Libyan medical students: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:570435. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570435 .

Grable JE, Joo S. Student racial differences in credit card debt and financial behaviors and stress. Coll Stud J. 2006;40(2):400–8.

Fritz MV, Chin D, DeMarinis V. Stressors, anxiety, acculturation and adjustment among international and North American students. Int J Intercult Rel. 2008;32(3):244–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.01.001 .

Ma L, Fu T, Qi J, Gao X, Zhang W, Li X, Cao S, Gao C. Study on cross-cultural adaptation and health status in medical international students. Chin J Med Edu Res. 2011;11:1379–82.

Misra R, Castillo LG. Academic stress among college students: Comparison of American and international students. Int J Stress Manage. 2004;11(2):132–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.11.2.132 .

Misra R, Crist M, Burant CJ. Relationships among life stress, social support, academic stressors, and reactions to stressors of international students in the United States. Int J Stress Manage. 2003;10(2):137–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.10.2.137 .

Mori S. Addressing the mental health concerns of international students. J Couns Dev. 2000;78(2):137–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb02571.x .

Olivas M, Li C. Understanding stressors of international students in higher education: what college counselors and personnel need to know. J Instr Psychol. 2006;32(3):217–22.

Al-Dubai SA, Al-Naggar RA, Alshagga MA, Rampal KG. Stress and coping strategies of students in a medical faculty in Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci. 2011;18(3):57–64.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Guillena RM, Guillena JB. Perceived stress, self-efficacy, and mental health of the first-year college students during Covid-19 pandemic. Indones J Multidiscip Sci. 2022;2(2):2005–13.

Davis M, Eshelman ER, McKay M. The relaxation & stress reduction workbook. 1st ed. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications; 2008.

Rashid T. Positive interventions in clinical practice. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):461–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20588 .

Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2006;61(8):774–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.774 .

Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50(3):571–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.571 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the participants in the investigation.

This research was supported by the Clinical Tree-Planting Project (M1590) and 345 Talent Project (M1463) of Shengjing Hospital to Bochen Pan.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Reproductive Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, No. 39 Huaxiang Road, Tiexi District, Shenyang, 110022, China

Yue Wang, Xiaobin Wang & Bochen Pan

The Fourth Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China

International Education School, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Xuehang Wang & Xiaoxi Guo

School and Hospital of Stomatology, China Medical University, Liaoning Provincial Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, Shenyang, China

Lulu Yuan & Yuqin Gao

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Yue Wang and Xiaobin Wang drafted the manuscript and analyzed the statistics. Xuehang Wang and Xiaoxi Guo collected the data. Lulu Yuan and Yuqin Gao reviewed the statistical approach. Bochen Pan designed the study.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bochen Pan .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University approved our study, and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants were asked to complete an informed consent agreement.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wang, Y., Wang, X., Wang, X. et al. Stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms among international students: a sequential mediation model. BMC Psychiatry 23 , 556 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05046-7

Download citation

Received : 19 December 2022

Accepted : 23 July 2023

Published : 01 August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05046-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Perceived stress

- Self-efficacy

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2024

Procrastination, depression and anxiety symptoms in university students: a three-wave longitudinal study on the mediating role of perceived stress

- Anna Jochmann 1 ,

- Burkhard Gusy 1 ,

- Tino Lesener 1 &

- Christine Wolter 1

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 276 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

691 Accesses

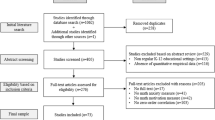

Metrics details