- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

53 Cognitive Style

Maria Kozhevnikov, Martinos Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, National University of Singapore, Singapore

- Published: 03 June 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter will review research on cognitive style from different traditions in order to revaluate previous and existing theoretical conceptions of cognitive style and to redefine cognitive style in accordance with current cognitive science and neuroscience theories. First, this chapter will review conventional and applied research on cognitive style that introduces the concept of cognitive style as patterns of adaptation to the external world and demonstrate that, although cognitive style develops on the basis of innate abilities, it is modified further as a result of changing environmental demands. Next, we will review the latest trends in cognitive style research that integrate different style dimensions into unifying models as well as recent findings in transcultural neuroscience that have documented the existence of culturally sensitive individual differences in cognition and suggested a close relationship between sociocultural environment and specific neural and cognitive patterns of information processing. Finally, based on our review, we will redefine cognitive style as ontogenetically flexible individual differences representing an individual’s adaptation of innate predisposition to external physical and sociocultural environments and expressing themselves as environmentally and culturally sensitive neural and/or cognitive patterns of information processing.

Historically, the term “cognitive style” refers to consistencies in an individual’s manner of cognitive functioning, particularly in acquiring and processing information (Ausburn & Ausburn, 1978 ). Messick ( 1976 ) defines cognitive styles as stable attitudes, preferences, or habitual strategies that determine individuals’ modes of perception, memory, thought, and problem solving. Witkin, Moore, Goodenough, and Cox ( 1977 ) characterize cognitive style as individual differences in the way people perceive, think, solve problems, learn, and relate to others.

While it seems obvious that there are differences among individuals’ preferred ways of processing information, what these differences mean and how they might be captured is less apparent. Despite being extremely popular throughout the 1950s–1970s, research on cognitive style has lost much of its appeal and has been seriously questioned in recent decades, and currently, many cognitive scientists are on the verge of accepting that cognitive style research has reached a standstill. The main reasons for this decline of interest in cognitive style seem to be the lack of a coherent organizing framework, and the lack of understanding of how cognitive style maps onto other psychological concepts and theories (see Kozhevnikov, 2007 , for a review). According to its definition, cognitive style should refer to the way individuals process information; however, since the vast majority of cognitive style studies were conducted before the rise of cognitive science, the concept of cognitive style has not been integrated with contemporary cognitive science theories, and the relationship between cognitive style’s and cognitive psychology’s approaches to individual differences in cognition has not been established (Kozhevnikov, 2007 , for a review).

Cognitive psychologists and neuroscientists researching individual differences in cognitive functioning have often focused on such basic dimensions of individual differences as speed of processing, working memory capacity (WMC), and general fluid intelligence ( Gf ). Overall, these reflect stationary individual differences in cognition, in the sense that these individual differences are largely genetically predetermined (Ando, Ono, & Wright, 2001 ; Deary, Penke, & Johnson, 2010 ; Friedman et al., 2008 ) and exhibit only limited ontogenetic sensitivity and training-induced plasticity (e.g., Sayala, Sala, & Courtney, 2005 ). Cognitive style researchers, in contrast, originally introduced the concept of cognitive style as specific modes of adjustment to the external world (Klein, 1951 ; Witkin, Dyk, Faterson, Goodenough, & Karp, 1962 ) modifiable by sociocultural and life experiences, and they have been primarily interested in more flexible , ontogenetically malleable individual differences that are shaped as a result of physical and sociocultural influences.

The goal of the current chapter is to incorporate the concept of cognitive style into current cognitive science theories of individual differences by integrating research findings on individual differences in cognition and cognitive styles from three different research perspectives: (1) cognitive style, (2) cognitive psychology and neuroscience, and (3) transcultural psychology and neuroscience. First, this chapter will review conventional research on cognitive style that introduces the concept of cognitive style as patterns of adaptation or specific modes of adjustment to the external world. Next, the chapter will review cognitive style research in applied fields (education, management) demonstrating that, although cognitive style develops on the basis of innate abilities, it is modified further as a result of changing environmental demands and life experiences, and it must thus be thought of not only in terms of innate predispositions but as a flexible construct, in terms of sociocultural interactions regulating an individual’s behavior. Third, we will summarize the latest trends in cognitive style research that have attempted to integrate the variety of cognitive style dimensions into unifying hierarchical models, and we relate these models to information processing theories. Fourth, we will review recent findings in transcultural psychology and neuroscience that have documented the existence of culturally sensitive individual differences in cognition and suggested a close relationship between sociocultural environment and specific neural and cognitive patterns of information processing.

Finally, based on our review, we will suggest a dissociation between (1) stationary individual differences that are determined primarily by genetic factors and exhibit only limited sensitivity to ontogenetic (environmental and sociocultural) factors; and (2) flexible individual differences or cognitive styles , whose formation, although affected by genetic factors, is largely influenced by environmental and sociocultural factors during ontogenetic development. According to the aforementioned approach, we will redefine the concept of cognitive style as ontogenetically flexible individual differences representing an individual’s adaptation of innate predisposition to external physical and sociocultural environments and expressing themselves as environmentally and culturally sensitive neural and/or cognitive patterns of information processing .

“Conventional” Cognitive Style

“Conventional” cognitive style research began in the late 1940s, with experimental research (e.g., Hanfmann, 1941 ; Klein, 1951 ; Klein & Schlesinger, 1951 ; Witkin & Ash, 1948 ) that focused on identifying the existence of consistent individual differences in performance on lower order cognitive tasks (e.g., perception, simple categorization). For example, Hanfmann ( 1941 ) identified two groups of individuals: those who preferred a perceptual approach when grouping blocks, and others who preferred a more conceptual approach. Klein ( 1951 ) identified “sharpeners,” who tended to notice differences between visual stimuli, and “levelers,” who tended to notice similarities.

These individual differences were first conceptualized as cognitive styles in the early 1950s, with Klein ( 1951 ) terming them as “perceptual attitudes.” These perceptual attitudes were defined as patterns of adaptation to the external world that regulate an individual’s cognitive functioning. According to Klein, adaptation requires balancing one’s inner needs with the requirements of the external environment. Klein also reported a relationship between cognitive style and personality; levelers exhibited a “self-inwardness” pattern characterized by “a retreat from objects, avoidance of competition,” while sharpeners were more manipulative and active (Klein, 1951 , p. 339). Klein considered both poles of the leveling/sharpening dimension as equally valid ways for individuals to achieve a satisfactory equilibrium between their inner needs and outer requirements, but different in their repertoire of psychological functions. Several years later, based on Klein’s findings, Holzman and Klein ( 1954 , p. 105) defined cognitive styles as “generic regulatory principles” or “preferred forms of cognitive regulation” in the sense that cognitive styles are an “ organism’s typical means of resolving adaptive requirements posed by certain types of cognitive problems ,” emphasizing the adaptive and flexible nature of cognitive style.

Around the same time, Witkin et al. ( 1954 ) carried out his large-scale experimental study on field dependence/independence, which was central to the further development of cognitive style research. The goal of this study was to investigate individual differences in perception and to associate these differences with particular trends in personality. Subjects were presented with a number of orientation tests aimed at examining their perceptual skills (e.g., Rod-and-Frame Test, in which the subjects determined the upright position of a rod, or Embedded Figure Test [EFT], in which the subjects were asked to find a simple figure inside a complex one) along with various personality measures. Two main groups of subjects were distinguished: field dependent (FD), those who exhibited high dependency on the surrounding field; and field independent (FI), those who displayed low dependency on the field. There was also a significant relationship between subjects’ performance on perceptual tests and their personality characteristics: FD individuals were more attentive to social cues than FI individuals. In contrast, the FI group had a more impersonal orientation than the FD group, exhibiting psychological and physical distancing from others. Witkin concluded that that the “core” of cognitive style is rooted in an individual’s innate predispositions, such as abilities or personality. Furthermore, Witkin explained individual differences in perception as outcomes of different modes of adjustment to the world, concluding that both FD and FI groups have specific components that are adaptive to particular situations. According to Witkin, Dyk, Paterson, Goodenough, and Karp ( 1962 ), field dependence reflects an earlier and less differentiated mode of adjustment to the world, and field independence reflects a later and more differentiated mode. However, although a highly differentiated FI individual could be highly efficient in perceptual and cognitive tasks, he or she may exhibit inappropriate responses to certain situational requirements and be in disharmony with his or her surroundings. Thus, both Klein and Witkin introduced the notion of cognitive style as patterns or modes of adjustment to the world, which appeared to be equal in their adaptive value but different in their level and repertoire of psychological and/or perceptual functions.

In the late 1950s, Klein’s and Witkin’s idea of bipolarity (value-equal poles of cognitive style dimensions in terms of adaptive nature) spawned a great deal of interest. As a result, a tremendous number of studies on “style types” appeared in the literature. The most commonly studied cognitive styles of this period are impulsivity/reflectivity (Kagan, 1966 ), tolerance for instability (Klein & Schlesinger, 1951 ), breadth of categorization (Pettigrew, 1958 ), field articulation (Messick & Fritzky, 1963 ), conceptual articulation (Messick, 1976 ), conceptual complexity (Harvey, Hunt, & Schroder, 1961 ), range of scanning, constricted/flexible controls (Gardner, Holzman, Klein, Linton, & Spence, 1959 ), holist/serialist (Pask, 1972 ), verbalizer/visualizer (Paivio, 1971 ), and locus of control (Rotter, 1966 ). Attempting to organize these numerous dimensions, Messick ( 1976 ) proposed a list of 19 cognitive styles; Keefe ( 1988 ) synthesized a list of 40 separate styles.

One of the serious limitations of conventional cognitive style research was its narrow focus on lower order cognitive tasks, often assessed by performance ability measures (error rate and response time) with simple “right” and “wrong” answers, which is hypothetically more relevant in testing abilities , not styles. Most of the perceptual tasks used as measures of cognitive style were tapping relatively stationary individual differences related to personality or intelligence. Ironically, this fact appears especially clear in the most commonly used instruments to measure cognitive styles, such as Witkin’s EFT (Witkin et al., 1954 ) and Kagan’s Matching Familiar Figures Test (MFFT; Kagan, Rosman, Day, Albert, & Phillips, 1964 ). While these instruments were supposed to measure bipolar dimensions representing two equally efficient ways of solving a task, in reality, one strategy was usually more effective than the other (e.g., FI subjects usually perform better than FD on many spatial tasks). It is not surprising then that many researchers who have investigated the correlation between intelligence tests and conventional measures of field dependence such as the Rod-and-Frame or EFT (e.g., Cooperman, 1980 ; Goodenough & Karp, 1961 ; McKenna, 1984 ) consistently report higher intelligence among individuals with an FI style than among those with an FD style.

Thus, despite that literature of that period has suggested the adaptive nature of cognitive style, and proposed that cognitive style refers to specific modes of adjustment to the external world (Klein, 1951 ; Witkin et al., 1962 ), early research on cognitive styles often used measures of individual differences sensitive mostly to genetic factors, and it did not clearly distinguish those from adaptive, ontogenetically malleable traits. This caused a situation in which the cognitive styles under study closely resembled genetically predetermined cognitive abilities, sparking later debates as to whether cognitive style and ability were indeed the same. Furthermore, since the majority of the aforementioned studies were conducted before the advent of cognitive science, their main problem was the lack of a unifying theoretical approach to information processing, which could lay the foundation for systematizing numerous overlapping cognitive style dimensions (see Kozhevnikov, 2007 for a review). Consequently, the promising benefits of studying cognitive styles were lost amidst the chaos, and the amount of work devoted to the cognitive style construct declined dramatically by the end of the 1970s, ironically, only a few years before information processing and cognitive science stepped into the forefront of contemporary psychology. Thus, although cognitive style refers to ways of processing information, since the majority of interest in cognitive style was abandoned before the rise of the information processing approach, a close relationship between cognitive style and other psychological concepts from contemporary information processing theories was never properly established.

Research in Applied Fields: Sociocultural Components of Cognitive Styles

Despite declining theoretical interest in conventional cognitive styles toward the end of the 1970s, the number of publications on cognitive styles in applied fields has continued to increase, reflecting an assumption of a practical necessity of understanding cognitive styles and their important role in real-life activities. Applied research on cognitive style focused on the existence of styles related to higher order cognitive functioning, such as problem solving, decision making, learning, and explanation of causality, as reviewed next.

Kirton ( 1976 , 1989 ) was the first to consider “decision-making styles” within the cognitive style framework by introducing the adaptor/innovator dimension of managerial style. Kirton defined adaptors as preferring to accept generally recognized policies while proposing ways of “doing things better,” and innovators as those who question the problem itself and propose ways “for doing things differently”; Kirton proposed that these differences were evident in personality as well as creativity and problem-solving strategies. Kirton ( 1989 ) investigated the adaptation/innovation dimension in organizational settings, widening the concept of cognitive style to characterize not only individuals but also the prevailing style in a group situation (called “organizational cognitive climate”). Kirton argued that overall cognitive climate stems from members of a workgroup sharing similar cognitive styles, that is, with all members within one-half standard deviation around the mean for the workgroup. Other studies on managerial decision-making styles were conducted by Agor ( 1984 ), who introduced three broad types of management styles in decision making: intuitive, analytical, and integrated problem-solving styles. Agor ( 1984 ) surveyed 2,000 managers of various occupations and managerial levels, and cultural backgrounds, and although it is not clear whether the differences cited are indeed statistically significant, Agor states that the data showed variation in executives’ dominant styles of management practice by organizational level, service level, and gender and ethnic background (e.g., women are more intuitive than men, managers of Asian background are more intuitive than the average manager). As did Kirton, Agor pointed out that one’s decision-making style not only includes stable individual characteristics but also applies to interpersonal communications and group behavior.

Rowe and Mason ( 1987 ) proposed a model of decision-making styles based on cognitive complexity (i.e., an individual’s tolerance for ambiguity) and environmental complexity (people-oriented vs. task-oriented work environment). The four styles derived from this model are directive (practical, power-oriented), analytical (logical, task-oriented), conceptual (creative, intuitive), and behavioral (people-oriented, supportive). Rowe and Mason stressed the importance of cognitive style in career success. More recent studies on styles in managerial fields have supported similar ideas. First, that cognitive style is a key “determinant of individual and organizational behavior, which manifests itself in both individual workplace actions and in organizational systems, processes, and routines” (Sadler-Smith & Badger, 1998 , p. 247). Second, although tending to be relatively stable, cognitive styles interact with the external environment and can be modified in response to changing situational demands, as well as influenced by life experiences (Allison & Hayes, 1996 ; Hayes & Allinson, 1998 ; Leonard & Straus, 1997 ).

At the same time, by the end of 1970s, a large number of “personal cognitive styles” have arisen in psychotherapy, such as optimistic/pessimistic, explanatory, anxiety-prone, and others (Haeffel et al., 2003 ; Peterson et al., 1982 ; Seligman, Abramson, Semmel, & von Baeyer, 1979 ). One of the first and most elaborated personality-related styles to be used widely in psychotherapy was the explanatory (attributional) style that reflects differences in the manner in which people habitually explain the causes of uncontrollable events (attributing the cause to internal vs. external circumstances). The cognitive component, according to this theory, refers to the ways in which people perceive, explain, and extrapolate events in their lives. Furthermore, the attribution theory suggests that styles are not always inherent to one’s personality and intelligence and, although relatively stable, can be acquired as a result of an individual’s interaction with the external environment (Peterson, Maier, & Seligman, 1993 ). It requires some amount of repetition of life events or observing other people’s behavior to reinforce or inhibit a certain style.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) remains the major tool for describing personal styles (Myers, 1976 ; Myers & McCaulley, 1985 ). The MBTI is a self-report instrument, which was developed based on four of Jung’s ( 1923 ) personality dimensions, extraversion/introversion (EI), sensing/intuition (SI), thinking/feeling (TF), and judging/perceiving (JP). Permutations of the four dimensions form 16 psychological types identified by the MBTI. Although evidence supporting the MBTI as a valid measurement of style is inconclusive (see Coffield, Moseley, Hall, & Ecclestone, 2004 , for a review), and there has been considerable controversy regarding its measurement characteristics (Carlson, 1989 ; Healy, 1989 ; McCaulley, 1991 ) and construct validity (e.g., Bess & Harvey, 2002 ; Girelli & Stake, 1993 ), similar to other “applied” approaches, the MBTI assumes close connections between one’s style and professional specialization and that certain professional settings are suited to individuals with different personality profiles.

The applied field that generated the greatest number of studies on styles was education. In education, research on style was aimed at understanding individual differences (preferences) in learning processes, and thus they were called “learning styles.” One of the first models of learning styles was proposed by Kolb ( 1974 , 1984 ), who suggested that the “cycle of learning” involves four adaptive learning modes—two opposing modes of grasping experience: concrete experience (CE) and abstract conceptualization (AC); and two opposing modes of transforming experience: reflective observation (RO) and active experimentation (AE). Kolb suggested the relationship between learning styles and educational or professional specialization, showing that different job requirements might cause changes in learning styles. Other research on learning styles has focused on the development of psychological instruments to assess individual differences in complex classroom situations (e.g., Dunn, Dunn, & Price, 1989 ; Entwistle, 1981 ; Schmeck, 1988 ). These studies all showed a close connection between educational environment and cognitive style. Overall, learning style research establishes the importance of how education might affect cognitive style and also how cognitive style may affect an individual’s preference for certain educational environments.

The main problem with applied research on cognitive style is similar to the problem with conventional cognitive style research: If in the conventional cognitive style research the number of styles was defined by the number of cognitive tasks used as assessors, here the number of styles was defined by the number of applied fields in which styles were studied. As a consequence, the cognitive style construct multiplied, and in addition to conventional cognitive styles, the new terminologies of decision-making styles, learning styles, and personal styles were introduced in the mid-1970s, without clear definitions of what they were or how they differed from conventional cognitive styles. Despite their problems, one of the most significant contributions of the applied studies to cognitive style research is the examination of how external, social-environmental factors affect the formation of cognitive style. Most of the applied studies on cognitive style converged on the conclusion that cognitive styles, although relatively stable, adapt to changing environmental and situational demands and can be modified by life experiences. Furthermore, evidence has accumulated regarding the connection between an individual’s cognitive style and the requirements of different social groups—including parent–child relationships, educational and professional societies, and sociocultural environment. Thus, the early definition of cognitive styles as patterns of adjustment to the world was further specified to include descriptions of particular requirements of social and professional groups on an individual’s cognitive functioning. Cognitive styles became related not only to personality, ability, or cognition but also to social interactions regulating beliefs and value systems.

Another significant contribution by this line of research is that it expanded the concept of cognitive style to include constructs that might operate not only at perceptual or simple cognitive levels but also on complex, higher order cognitive levels (decision making, learning preferences). Overall, the applied studies on cognitive style seem to more apparently reflect the flexible nature of cognitive styles (e.g., interaction and development within professional and educational settings; relevance for sociocultural interactions and overall sociocultural context).

Recent Developments in Cognitive Style Research

Since the 1970s, conventional cognitive style and applied cognitive style studies have been joined by new trends in cognitive style research, which can be divided into three rough categories. The first includes studies that suggest the existence of cognitive styles (e.g., mobility-fixity), or “metastyles,” that operate on the metacognitive level. The second category contains studies that attempt to unite existing models of cognitive style into a unifying theory with a limited number of central dimensions, culminating in a few theoretical studies that aim to build multilevel hierarchical models of cognitive styles.

The Mobility/Fixity Dimension: “Metastyle”

Studies of the mobility/fixity (also called flexibility/rigidity) dimension attempted to address contradictory results from previous research on conventional cognitive styles, namely, the mobility of cognitive style. Witkin was the first to point out that there might be “mobile” individuals who possess both FD and FI characteristics, and can employ one style or the other depending on the situation (Witkin, 1965 ; Witkin et al., 1962 ). According to Witkin, while FI individuals as a group tend to be creative, FI individuals who also possess FD characteristics may be even more creative, since such mobility signifies greater diversity in functioning and is more adaptive than fixed use of a single style.

Furthermore, Niaz ( 1987 ) administered the ETF and Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices Test to a group of college freshmen to assess their field dependence/independence and intelligence level. In addition, participants received the Figural Intersection Test to measure mobility/fixity. According to their results on the EFT and Figural Intersection Test, four groups of participants were identified: mobile FI, mobile FD, fixed FI, and fixed FD. Niaz reported that the fixed FI group of students received the highest intelligence scores among all the groups on the Raven’s Matrices Test, while mobile individuals (both FD and FI) performed significantly better than all other groups in college chemistry, mathematics, and biology classes. Niaz ( 1987 , p. 755) concluded that “mobile subjects are those who have available to them both a developmentally advanced mode of functioning (field-independence) and a developmentally earlier mode (field-dependence).” Furthermore, she also concluded that in mature individuals, fixed functioning implies a certain degree of inflexibility and inability to regress to earlier perceptual modes.

Furthermore, Russian psychologist Kholodnaya ( 2002 ) suggested a quadripolar model of several conventional cognitive styles: field dependence/independence, wide/narrow categorization, constricted/flexible cognitive control, and impulsivity/reflectivity. Participants were administered a number of different cognitive style and intelligence tests (EFT, the MFFT, Raven’s Matrices, Stroop task) and a word sorting task. Using cluster analysis, four clusters in the field-dependency/independency dimension were identified. One seemed to represent fixed FI individuals, who demonstrated high scores on EFT; however, they showed high interference and longer response times in the Stroop task, as well as low concept formation ability (as measured by the word sorting task). In contrast, another cluster, representing mobile field independence , included individuals who, along with high EFT scores, showed relatively high performance on the word sorting task, lower conflict on the Stroop task, and higher ability to integrate sensory information with context. The other two clusters, fixed FD and mobile FD , were similar in their relatively poor response on the EFT. However, in contrast to fixed FD, mobile FD individuals exhibited low cognitive conflict in the Stroop task and better ability to coordinate their verbal responses with presented sensory information. Kholodnaya found similar patterns for each of the following dimensions: constricted/flexible cognitive control, impulsivity/reflexivity, and narrow/wide range of equivalence. She concluded that mobile individuals can spontaneously regulate their intellectual activities and effectively resolve cognitive conflicts. In contrast, fixed individuals are unable to adapt their strategies to the situation and exhibit difficulties in monitoring their intellectual activity. Thus, according to Kholodnaya, cognitive style represents the extent to which the metacognitive self-monitoring mechanisms are formed in a particular individual, and in the case of a fixed individual, it is more appropriate to talk about a cognitive deficit rather than a cognitive style.

The important contribution of this research is that it introduces the notion of metacognition to the field of cognitive style. However, there is little support for the conclusions that fixed individuals exhibit cognitive deficits, or that cognitive style can be reduced to metacognition, or that the majority of the cognitive styles are quadripolar dimensions. Rather, the results seem to suggest that individuals are different in the extent to which they exhibit flexibility and their degrees of self-monitoring in their choices of different cognitive styles. Mobility/fixity may be better viewed as a metastyle representing the level of flexibility with which an individual applies a particular style in a particular situation. More recently, Kozhevnikov ( 2007 ) suggested that the mobility/fixity dimension represents a superordinate metastyle dimension, which serves as a control structure for other subordinate cognitive styles. That is, metastyle represents the developmental level of an individual’s metacognitive mechanisms—the ability to consciously control and situationally adapt one’s own active problem-solving strategies to the degree that he or she has a number of available potential solutions and strategies (which may involve opposing cognitive styles) and can select the most appropriate one for any given task.

Toward Hierarchical Models of Cognitive Style

The unifying trend emerged in the 1990s as a general response to vagueness in the cognitive style field, and it aimed to unite and systematize multiple cognitive style dimensions. For example, Hayes and Allinson ( 1994 ) proposed that the different dimensions of cognitive style can be considered as variations of an overarching analytical-intuitive dimension. Others characterize cognitive style as consisting of two orthogonal dimensions, such as holistic-analytical versus visualizer-verbalizer (Hodgkinson & Sadler-Smith, 2003 ; Riding & Cheema, 1991 ). However, these models of cognitive style were too simplistic; they tried to reduce cognitive style to a limited number of dimensions, rather than build a theory that systematizes known styles into a multidimensional structure. Generally, models of cognitive style do not consider cognitive style in the context of information processing theories; they neither attempt to relate cognitive styles to other psychological theories, nor do they fully account for the complexity of the cognitive style construct. Miller ( 1987 ) was the first to consider cognitive style in the context of information processing and proposed that cognitive style consisted of a horizontal analytical-holistic dimension and a vertical dimension representing different stages and levels of information processing, such as perception, memory (representation, organization, and retrieval), and thought. However, Miller’s model has been criticized for its lack of empirical support, and that the placement of cognitive style dimensions into the model was based more on convenience than research evidence or theoretical framework (Messick, 1994 ; Zhang & Sternberg, 2006 ).

There have been few empirical attempts to systematize cognitive style dimensions (e.g., Leonard, Scholl, & Kowalski, 1999 ; Bokoros, Goldstein, & Sweeney, 1992 ). For example, Bokoros et al. ( 1992 ) conducted an empirical study based on the factor analysis of correlations between the various subscales of widely used cognitive style instruments. They identified three factors, to which a variety of cognitive style dimensions could be reduced, which were dubbed as the “information-processing domain,” the “thinking-feeling dimension,” and the “attentional focus dimension.” It is interesting to note that the first and second factors identified empirically by Bokoros et al. closely resemble “conventional” and “applied” styles, respectively. While the first factor comprised cognitive style dimensions that operate at perceptual and low-order cognitive levels, the second factor comprised styles related to individual differences in more complex, higher order cognitive activities. As for the third factor, which is described by Bokoros et al. as “internal and external application of the executive cognitive function,” it closely resembles the mobility/fixity dimension, or metastyle, described in the mobility/fixity lines of research.

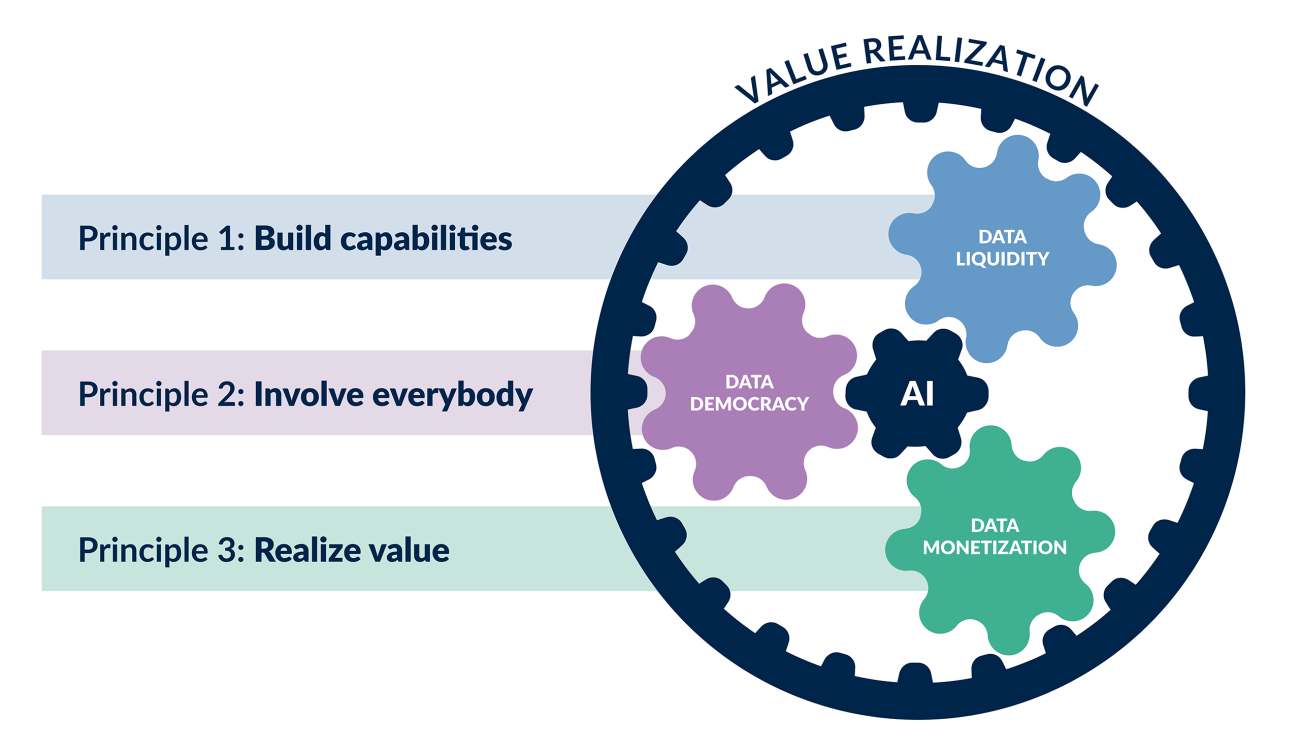

Finally, Nosal ( 1990 ) proposed a multidimensional hierarchical model of cognitive style that systematized cognitive style dimensions based on cognitive science theories. Specifically, the model proposes that the variety of cognitive styles can be arranged into a matrix (see Fig. 53.1 ). The horizontal axis of the matrix represents four hierarchical levels of information processing: perception (processing of primary/early perceptual information), concept formation (formation of conceptual representations in the form of symbolic, semantic, and abstract structures), modeling (organizing personal experiences into “schemas,” “models,” or “theories”), and program (goal-directed activity and metacognitive approaches used for complex decision-making tasks).

Cognitive styles in relation to levels of information processing and cross-dimensions, according to Nosal’s theory. 1 = field dependence-independence; 2 = field articulation; 3 = breadth of categorization; 4 = range of equivalence; 5 = articulation of conceptual structure; 6 = tolerance for unrealistic experience; 7 = leveling-sharpening; 8 = range of scanning; 9 = reflectivity-impulsivity; 10 = rigidity-flexibility; 11 = locus of control; 12 = time orientation.

After positioning different conventional styles into these four levels of information processing, Nosal identified a number of vertical cross-dimensions, which he described as “modules of information processing” that encompass all the variety of cognitive styles. These stylistic cross-dimensions, according to Nosal, reflect regulatory mechanisms responsible for generating four qualitatively different bipolar cognitive style dimensions: (1) field structuring ( context dependent vs. context independent ), which describes a tendency to shift attention to perceiving events as separate versus inseparable from their context; (2) field scanning ( rule-driven vs. intuitive ), which describes a tendency for directed, driven by rules, versus aleatoric, driven by salient stimuli, information scanning; (3) control allocation ( internal vs. external locus of processing ), which describes ways of locating criteria for processing at the internal versus external center; and (4) equivalence range ( compartmentalization vs. integration ), which represents a tendency to process and output information globally versus sequentially. The model allows detecting some gaps in the area of cognitive style and identifying yet unknown cognitive styles dimensions in the cells of the matrix. For instance, field-structuring cross-dimension has been studied so far on the basis of Witkin’s field dependence/independence cognitive style, which operates mostly on the perceptual level, so context-dependent/independent styles operating at higher levels of cognitive processing have yet to be identified.

It is interesting to note that the cross-dimensions that Nosal derived from his model resemble the metacomponents suggested by Sternberg’s componential theory of intelligence (selection of low-order components, selection of representation or organization of information, and selection of a strategy for combining lower order components), which are defined as the “specific realization of control processes…sometimes collectively (and loosely) referred to as the executive” (Sternberg, 1985 , p. 99). Thus, the four major cross-dimensions identified by Nosal seem to reflect four different types of executive functions or cognitive control processes that regulate an individual’s perception, thoughts, and actions, and generate four qualitatively different bipolar cognitive style dimensions (i.e., context dependent vs. context independent; rule-driven vs. stimulus-driven information scanning; internal vs. external locus of control; and holistic vs. sequential processing). In this view, any given cognitive style can be viewed as an expression of a particular executive function from these four cross-dimensions, operating at a particular level of information processing. Thus, according to Nosal’s categorization, the number of cognitive styles is finite and unknown styles could be predicted and placed into the cells of the matrix.

In summary, the recent studies on cognitive style endeavored to systematize the variety of cognitive styles and establish a possible structural relationship among them. These studies cast serious doubt on the unitary nature of cognitive style and provided evidence for the hierarchical organization of cognitive style dimensions operating at different levels of information processing (from perceptual to metacognitive). Furthermore, Nosal’s model allows for mapping existing models of cognitive style onto information processing theories, taking into account the complex structure and multidimensionality of the cognitive style construct. Furthermore, many of the aforementioned studies pointed out the regulatory function of cognitive styles. Nosal’s model, in particular, suggested that all the variety of cognitive style dimensions might be clustered around a limited number of stylistic cross-dimensions, related to specific executive functions.

Perspectives From Cognitive Sciences and Neuroscience

Recent cognitive science and neuroscience studies provided new evidence that shed light on the nature of cognitive style and its relation to other basic psychological constructs and processes. In this section, we will review two categories of recent cognitive science and neuroscience studies.

The first line of research contains a few recent cognitive neuroscience studies that attempted to demonstrate that cognitive style may be more accurately represented by specific patterns of neural activity, and not only by differences in performance on behavioral measures. Gevins and Smith ( 2000 ) examined differences between subjects with verbal versus nonverbal cognitive styles by recoding their electroencephalograms (EEGs) while the subjects performed a spatial working memory task. The results showed that although the subjects did not significantly differ in task performance, subjects with a verbal cognitive style tended to make greater use of the left parietal region, whereas subjects with a nonverbal style tended to make greater use of the right parietal region. Furthermore, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) experiments have revealed that, while performing the EFT (which can be solved with either visual-object or visual-spatial strategies), in the absence of significant behavioral differences in task performance, spatial visualizers (i.e., individuals who prefer to process information spatially in terms of spatial relations and locations) showed greater activation in left occipito-temporal areas, while the object visualizers (i.e., individuals who prefer to process information visually in terms of color, shape, and detail) showed greater activation in the bilateral occipito-parietal junction (Motes, Malach, & Kozhevnikov, 2008 ), supporting the relationship between individual differences in visual cognitive style and differential use of regions in the dorsal and ventral visual processing streams. The importance of these studies is that they indicate that individuals with different cognitive styles may exhibit different patterns of neural activity, even though their behavioral performance may not significantly differ. That is, the findings imply that the differences underlying individuals’ cognitive styles can be associated with different patterns of neural activity in the brain, in addition to the ability to perform a particular task.

The second line of studies is related to the most recent cognitive and cultural neuroscience studies that demonstrated that culture-specific experiences may afford distinct patterns of information processing. Surprisingly, these culture-sensitive patterns of information processing were indentified not only at cognitive levels but also at the neural and perceptual levels, suggesting that sociocultural experiences may affect neural pathways and also shape perception (e.g., Han & Northoff, 2008 ). For instance, several studies have shown that members of Eastern cultures exhibit more holistic and field-dependent rather than analytic and field-independent perceptual affordances (e.g., Miyamoto, Nisbett, & Masuda, 2006 ;Nisbett & Masuda, 2003 ). On a change blindness task, East Asians detected more changes in background context, whereas North Americans detected more changes in foreground objects (Nisbett & Masuda, 2003 ). Kitayama, Duffy, Kawamura, and Larsen ( 2003 ) also found that while North Americans were more accurate in an “absolute task” (drawing a line that was identical to the first line in absolute length), Japanese people were more accurate in a “relative task” (drawing a line that was identical to the first in relation to the surrounding frame), suggesting that the Japanese participants paid more attention to the frame (context) than did the North Americans and were more field dependent. Other studies reported that North Americans recognized previously seen objects in changed contexts better than Asians did, due to their increased focus on objects’ features independent of context (Chua, Boland, & Nisbett, 2005 ). Gutchess, Welsh, Boduroglu, and Park ( 2006 ) evaluated neural bases for these cultural differences in fMRI, concluding that cultural experiences subtly direct neural activity, particularly for focal objects in early visual processing.

Differences between members of different cultures were also reported on lower order and higher order cognitive tasks, as well as on tasks that require metacognitive processing. For instance, Chinese participants organized objects more relationally (e.g., grouping “monkey” and “banana” together because monkeys eat bananas) and less categorically (e.g., grouping “panda” and “monkey” together because both are animals) than Westerners (Nisbett, 2003 ), reflecting differences in field scanning. Significant differences between Easterners and Westerners have also been found in decision making. Kume ( 1985 ) discovered that, when making decisions, Easterners adopt an indirect, agreement-centered approach, based on intuition, while Westerners favor a direct, confrontational strategy using rational criteria. There are also cross-cultural differences at the neural level in language processing; English speakers reading English words activate superior temporal gyrus, but Chinese speakers reading Chinese characters activate inferior parietal lobe (Tan, Laird, Li, & Fox, 2005 ), which might indicate differences in global versus sequential processing.

Furthermore, research also identified self-construal differences: Westerners characterize the self as independent and have self-focused attention, while East Asians emphasize interdependence and social context (Nisbett, Choi, Peng, & Norenzayan, 2001 ). Also, Americans believe that they have control over events to the extent that they often fail to distinguish between objectively controllable events and uncontrolled ones. In contrast, East Asians are not susceptible to this illusion (Glass & Singer, 1973 ), reflecting differences in the locus of control dimension.

Overall, the reported cultural differences were identified at all levels of information processing (from perceptual to higher order cognitive reasoning) and can be generally described as tendencies of East Asian people (1) to engage in context-dependent cognitive processes, while Westerners, who tend to think about the environment analytically, engage in context-independent cognitive processes (Goh et al., 2007 ; Miyamoto et al., 2006 ); (2) to seek intuitive instantaneous understanding through direct perception, while Westerners favor more logic and abstract principles (Nakamura, 1985 ); (3) to exhibit more external locus of control in contrast to Westerners, who have stronger internal locus (Glass & Singer, 1973 ; Nisbett et al., 2001 ); and (4) to have tendencies to perceive and think about the environment more holistically and globally, in contrast to Westerners, who engage in more sequential processing (Goh et al., 2007 ).

Interestingly, all the reported culture-sensitive individual difference can be described by Nosal’s four style cross-dimensions (executive functions), field scanning, organization, locus of control, and equivalence range, and can therefore be positioned into the cells of Nosal’s matrix of cognitive style dimensions, according to the specific executive function they perform and the dominant level of information processing involved in a given task. Thus, culture-sensitive individual differences reported in transcultural psychology and neuroscience seem to represent different dimensions of cognitive style described in the cognitive style literature, and yet unidentified, culture-sensitive individual differences in cognition might be predicted from the Nosal’s matrix.

While cognitive psychology research provides evidence that some components of executive functions (e.g., updating working memory representations, shifting between task sets) are entirely genetic in origin (Friedman et al., 2008 ), social-constructivist research argues for the sociocultural origin of executive functioning, suggesting its flexible nature (e.g., Ardila, 2008 ; Vygotsky, 1984 ). In light of the proposed framework distinguishing between stationary and flexible individual differences, as well as on the basis of the review of culture-sensitive individual differences, we suggest that the four executive functions derived from Nosal’s theory represent “flexible” components of executive functioning, which are shaped and mediated by sociocultural environment. On the basis of this approach, cognitive style research can contribute to transcultural psychology and neuroscience research by helping to organize and predict different dimensions of culture-sensitive individual differences.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The current review attempts to bridge the gap between the large body of traditional cognitive style concepts, cognitive neuroscience, and transcultural psychology and neuroscience research, using an organizing framework that distinguishes between relatively stationary (i.e., abilities, personality traits) and ontogenetically flexible (cognitive styles) individual differences in cognition. As demonstrated throughout the review, the lack of discrimination between stationary and flexible individual differences, as well as the absence of a common theoretical framework for mapping the cognitive style concept onto existing cognitive science and neuroscience research, has led to misinterpretation and underestimation of the cognitive style concept.

The reviewed literature on the state of affairs in the aforementioned three research traditions suggests that the concept of cognitive style has a place in, and should be integrated into, mainstream current cognitive science and neuroscience theories. One of the possible approaches to integrate cognitive style into contemporary cognitive science theories can be based on Nosal’s ( 1990 ) model, which proposes that the variety of cognitive styles could be structuralized as the elements of a matrix, with the horizontal axis representing different levels of information processing (from perception to metacognition) and the vertical axis representing four major types of stylistic cross-dimensions that reflect specific executive functions responsible for generating four qualitatively different bipolar cognitive style dimensions (i.e., context dependent vs. context independent; rule-driven vs. stimulus-driven information scanning; internal vs. external locus of control; holistic vs. sequential processing). Nosal’s model takes into account the complex structure and multidimensionality of the cognitive style construct, and it allows for predicting the existence of other, yet unidentified, styles.

Based on our review, we suggest redefining cognitive style as ontogenetically flexible individual differences representing an individual’s adaptation of innate predisposition to external physical and sociocultural environments and expressing themselves as environmentally and culturally sensitive neural and/or cognitive patterns of information processing. To an extent far greater than that seen in other animals, who are born in a given environment and bound for generations to specific environmental conditions and thus might exhibit numerous fixed inborn patterns of behavior that result from long-term evolutionary processes, humans are much less restricted by fixed innate mechanisms suited for specific environmental conditions. This places more importance on the role of postnatal development, which is largely based on social interactions, concepts, and cultural means of learning, and takes place in ever-expanding and changing environments throughout the life span. Thus, the inborn capacities of humans allow for a wide range of possibilities for their future expression and development. Recent evidence from neuroscience indicates that neurogenesis and neural plasticity are affected by social environments (Lu et al., 2003 ). Research in evolutionary genetics consistently shows evidence of the neural plasticity of human behavior in relation to sociocultural environment, and the coevolution of genes, cognition, and culture (see Li, 2003 for review).

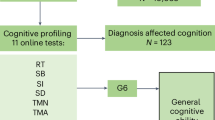

The proposed view on individual differences in cognition is reflected in the model presented in Figure 53.2 . The core is formed by the individual’s innate predispositions and personality traits, which reflect stationary individual differences. This core

Layers constituting individual differences in cognition. (See color insert.)

is surrounded by cognitive style, reflecting flexible individual differences. The development of cognitive style occurs on the basis of these innate core traits and is shaped through interaction with the surrounding environment. The first environmental layer represents the individual’s immediate familial and physical environment, which influences early cognitive development and reinforces certain innate characteristics, while suppressing others. At the next level lies the educational layer, in which the individual progresses through school systems and develops certain problem-solving strategies. The next layer is the professional layer, in which individuals’ ways of thinking are sharpened and become more distinct. In the professional layer, an individual’s cognitive style is affected by both mediated information contained in the professional media, as well as personal interactions with peers. Surrounding all of these is the final, cultural layer, reflecting mental, behavioral and cognitive processing patterns common to a specific cultural group. All these sociocultural layers affect each other and together shape the different layers of information processing and behavioral patterns of an individual. Metacognitive processes can possibly affect all the subordinate layers of information processing; a person with highly developed metacognitive processes would be aware of his or her preferred style, and, when presented with tasks or situations that require use of a different style, would flexibly adapt his or her strategies. The development of flexible metatstyles would allow an individual to switch between preferred styles. Possible reasons for the formation of flexible metastyles could be experiencing different situational contexts (such as different professional, educational, and cultural settings), changing professional field, or changing cultural context (native language, traditions). Indeed, Bagley and Mallick ( 1998 ) indicated malleability of cognitive styles in migrant children and suggested that concept of cognitive style can be deployed as an indicator of process and change in migration and multicultural education, rather than as a description of basic cognitive processes.

The current organizing framework that distinguishes between stationary and ontogenetically flexible individual differences in cognition helps to bridge the gap between the large body of traditional cognitive style concepts, cognitive neuroscience, and transcultural psychology and neuroscience research. We argue for the importance of such a framework for cognitive psychology and neuroscience, which still lacks a coherent framework of individual differences. Moreover, such an organizing framework will be crucial for helping transcultural psychology and neuroscience identify the causes of found cross-cultural individual differences (e.g., whether the identified differences are due to long-term evolutionary processes or ontogenetic development) and assign relative weight to such causes (e.g. whether within-culture differences, such as in educational and/or professional contexts, might overshadow the global cultural effect). Finally, such a framework will aid in understanding the relation between cognitive style and other cognitive science concepts, suggesting that cognitive style can be a valuable concept beyond the largely abandoned filed of cognitive style research, and can bring new insights in understanding the individual differences in humans’ cognitive functioning.

Ardila A. ( 2008 ). On the evolutionary origins of executive functions. Brain and Cognition, 68, 92–99.

Agor W. H. ( 1984 ). Intuitive management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ : Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Allison J., &Hayes, C. ( 1996 ). The Cognitive Style Index, a measure of intuition-analysis for organizational research, Journal of Management Studies, 33, 119–135.

Ando J. , Ono Y. , & Wright M. J. ( 2001 ). Genetic structure of spatial and verbal working memory. Behavior Genetics, 31, 615–624.