The Sociology of Social Inequality

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

Social inequality results from a society organized by hierarchies of class, race, and gender that unequally distributes access to resources and rights.

It can manifest in a variety of ways, like income and wealth inequality, unequal access to education and cultural resources, and differential treatment by the police and judicial system, among others. Social inequality goes hand in hand with social stratification .

Social inequality is characterized by the existence of unequal opportunities and rewards for different social positions or statuses within a group or society. It contains structured and recurrent patterns of unequal distributions of goods, wealth, opportunities, rewards, and punishments.

Racism , for example, is understood to be a phenomenon whereby access to rights and resources is unfairly distributed across racial lines. In the context of the United States, people of color typically experience racism, which benefits white people by conferring on them white privilege , which allows them greater access to rights and resources than other Americans.

There are two main ways to measure social inequality:

- Inequality of conditions

- Inequality of opportunities

Inequality of conditions refers to the unequal distribution of income, wealth, and material goods. Housing, for example, is inequality of conditions with the homeless and those living in housing projects sitting at the bottom of the hierarchy while those living in multi-million dollar mansions sit at the top.

Another example is at the level of whole communities, where some are poor, unstable, and plagued by violence, while others are invested in by businesses and government so that they thrive and provide safe, secure, and happy conditions for their inhabitants.

Inequality of opportunities refers to the unequal distribution of life chances across individuals. This is reflected in measures such as level of education, health status, and treatment by the criminal justice system.

For example, studies have shown that college and university professors are more likely to ignore emails from women and people of color than they are to ignore those from white men, which privileges the educational outcomes of white men by channeling a biased amount of mentoring and educational resources to them.

Discrimination of an individual, community, and institutional levels is a major part of the process of reproducing social inequalities of race, class, gender , and sexuality. For example, women are systematically paid less than men for doing the same work.

2 Main Theories

There are two main views of social inequality within sociology. One view aligns with the functionalist theory, and the other aligns with conflict theory.

- Functionalist theorists believe that inequality is inevitable and desirable and plays an important function in society. Important positions in society require more training and thus should receive more rewards. Social inequality and social stratification, according to this view, lead to a meritocracy based on ability.

- Conflict theorists, on the other hand, view inequality as resulting from groups with power dominating less powerful groups. They believe that social inequality prevents and hinders societal progress as those in power repress the powerless people to maintain the status quo. In today's world, this work of domination is achieved primarily through the power of ideology, our thoughts, values, beliefs, worldviews, norms, and expectations, through a process known as cultural hegemony .

How It's Studied

Sociologically, social inequality can be studied as a social problem that encompasses three dimensions: structural conditions, ideological supports, and social reforms.

Structural conditions include things that can be objectively measured and that contribute to social inequality. Sociologists study how things like educational attainment, wealth, poverty, occupations, and power lead to social inequality between individuals and groups of people.

Ideological supports include ideas and assumptions that support the social inequality present in a society. Sociologists examine how things such as formal laws, public policies, and dominant values both lead to social inequality, and help sustain it. For example, consider this discussion of the role that words and the ideas attached to them play in this process.

Social reforms are things such as organized resistance, protest groups, and social movements. Sociologists study how these social reforms help shape or change social inequality that exists in a society, as well as their origins, impact, and long-term effects.

Today, social media plays a large role in social reform campaigns and was harnessed in 2014 by British actress Emma Watson , on behalf of the United Nations, to launch a campaign for gender equality called #HeForShe.

Milkman, Katherine L., et al. “ What Happens before? A Field Experiment Exploring How Pay and Representation Differentially Shape Bias on the Pathway into Organizations. ” Journal of Applied Psychology , vol. 100, no. 6, 2015, pp. 1678–1712., 2015, doi:10.1037/apl0000022

“ Highlights of Women's Earnings in 2017 .” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics , Aug. 2018.

- The Differences Between Socialism and Communism

- Introduction to Sociology

- What You Need to Know About Economic Inequality

- What Is Social Stratification, and Why Does It Matter?

- The Sociology of Education

- Visualizing Social Stratification in the U.S.

- What's the Difference Between Prejudice and Racism?

- What Is Social Oppression?

- How Expectation States Theory Explains Social Inequality

- Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge

- The Sociology of Consumption

- The Sociology of Gender

- Theories of Ideology

- Sociology Of Religion

- Understanding Poverty and Its Various Types

- Understanding Meritocracy from a Sociological Perspective

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 9. Social Inequality

9.1. What Is Social Inequality?

Sociologists use the term social inequality to describe the unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and social positions in a society. Key to the concept are the notions of social differentiation and social stratification . The question for sociologists is: how are systems of stratification formed? What is the basis of systematic social inequality in society?

Social differentiation refers to the social characteristics — social differences, identities, and roles — used to differentiate people and divide them into different categories, such as race, gender, age, class, occupation, and education. These social categories have implications for social inequality. Social differentiation by itself does not necessarily imply a division of individuals into a hierarchy of rank, privilege, and power. However, when a social category like class, occupation, gender, or race puts people in a position where they can claim a greater share of resources or rewards, then social differentiation becomes the basis of social inequality.

The term social stratification refers to an institutionalized system of social inequality. It refers to a situation in which social inequality has solidified into an ongoing system that determines and reinforces who gets what, when, and why. Social differentiation based on different characteristics becomes the basis for social inequality.

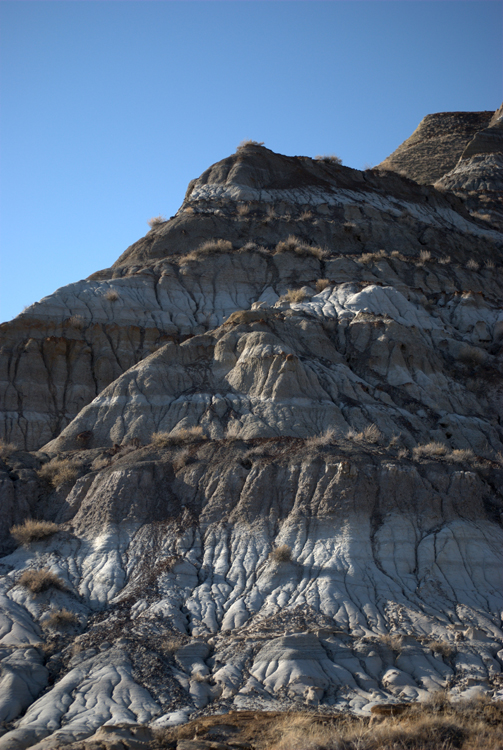

Students may remember the word “stratification” from geology class. The distinct horizontal layers found in rock, called “strata,” are a good way to visualize social structure. Society’s layers are made of people, and society’s resources are distributed unevenly throughout the layers. The people with the most resources represent the top layer of the social structure of stratification. Other groups of people, with progressively fewer and fewer resources, represent the lower layers of society. Social stratification assigns people to socio-economic strata based on a process of social differentiation — “these type of people go here, and those type of people go there.” The outcome is differences in wealth, income and power. Again, the question for sociologists is how systems of stratification are formed. What is the basis of systematic social inequality in society?

Equality of Condition and Equality of Opportunity

In Canada, the dominant ideological presumption about social inequality is that everyone has an equal chance at success. This is the belief in equality of opportunity , which can be contrasted with the concept of equality of condition . Equality of opportunity is the idea that everyone has an equal possibility of becoming successful. It exists when people have the same chance to pursue economic or social rewards. This is often seen as a function of equal access to education, meritocracy (where individual merit determines social standing), and formal or informal measures to eliminate social discrimination.

Equality of condition is the situation in which everyone in a society has a similar actual level of wealth, status, and power. Although degrees of equality of condition vary markedly in modern societies, it is clear that even the most egalitarian societies today have considerable degrees of inequality of condition. Ultimately, equality of opportunity means that inequalities of condition are not so great that they greatly hamper a person’s opportunities or life chances. Whether Canada is a society characterized by equality of opportunity, or not, is a subject of considerable sociological debate.

To a certain extent, Ted Rogers’ story illustrates the idea of equality of opportunity. His personal narrative is one in which hard work and talent — not inherent privilege, birthright, prejudicial treatment, or societal values — determined his social rank. This emphasis on individual effort is based on the belief that people individually control where they end up in the social hierarchy, which is a key piece in the idea of equality of opportunity. Most people connect inequalities of wealth, status, and power to the individual characteristics of those who succeed or fail. The story of the Aboriginal gang members, although it is also a story of personal choices, casts that belief into doubt. It is clear that the type of choices available to the Aboriginal gang members are of a different range and quality than those available to the Rogers family. The available choices and opportunities are a product of habitus and location within the system of social stratification .

While there are always inequalities between individuals in terms of talent, skill, drive, chance, and so on, sociologists are interested in larger social patterns. Social inequality is not about individual qualities and differences, but about systematic inequalities based on group membership, class, gender, ethnicity, and other variables that structure access to rewards and status. In other words, sociologists are interested in examining the structural conditions of social inequality. There are of course differences in individuals’ abilities and talents that will affect their life chances. The larger question, however, is how inequality becomes systematically structured in economic, social, and political life. In terms of individual ability: Who gets the opportunities to develop their abilities and talents, and who does not? Where does “ability” or “talent” come from? As Canadians live in a society that emphasizes the individual (individual effort, individual morality, individual choice, individual responsibility, individual talent, etc.) it is often difficult to see the way in which life chances are socially structured.

Wealth, Income, Power and Status

Factors that define the layers of stratification vary in different societies. In most modern societies, stratification is indicated by differences in wealth , the net value of money and assets a person has, and income , a person’s wages, salary, or investment dividends. It can also be defined by differences in power (e.g., how many people a person must take orders from versus how many people a person can give orders to, or how many people are affected by one’s orders) and status (the degree of honour or prestige one has in the eyes of others). These four factors create a complex amalgam that defines an individual’s social standing within a hierarchy.

Usually the four factors coincide, as in the case of corporate CEOs, like Ted Rogers, at the top of the hierarchy — wealthy, powerful, and prestigious — and the Aboriginal offenders at the bottom — poor, powerless, and abject. Sociologists use the term status consistency to describe the consistency of an individual’s rank across these factors.

Students can also think of someone like the Canadian Prime Minister — who ranks high in power, but with a salary of approximately $320,000 — earns much less than comparable executives in the private sector (albeit eight times the average Canadian salary). The Prime Minister’s status or prestige also rises and falls with the fluctuations of politics and public opinion. The Nam-Boyd scale of status, based on education and income, ranks politicians (legislators) at 66/100, the same status as cable TV technicians (Boyd, 2008). There is status inconsistency in the prime minister’s position.

Teachers often have high levels of education, which give them high status (92/100 according to the Nam-Boyd scale), but they receive relatively low pay. Many believe that teaching is a noble profession, so teachers should do their jobs for the love of their profession and the good of their students, not for money. Yet no successful executive or entrepreneur would embrace that attitude in the business world, where profits are valued as a driving force. Cultural attitudes and beliefs like these support and perpetuate social inequalities.

Systems of Stratification

Sociologists distinguish between two types of stratification systems. Closed systems accommodate little change in social position. They do not allow people to shift levels and do not permit social relations between levels. Open systems, which are based on achievement, allow movement and interaction between layers and classes. The different systems also produce and foster different cultural values, like the values of loyalty and traditions versus the values of innovation and individualism. The difference in stratification systems can be examined by the comparison between class systems and caste systems.

The Caste System

Caste systems are closed stratification systems in which people can do little or nothing to change their social standing. A caste system is one in which people are born into their social standing and remain in it their whole lives. It is based on fixed or rigid status distinctions, rather than economic classes per se.

As noted above, status is defined by the level of honour or prestige one receives by virtue of membership in a group. Sociologists make a distinction between ascribed status: a status one receives by virtue of being born into a category or group (e.g., caste, hereditary position, gender, race, ethnicity, etc.), and achieved status: a status one receives through individual effort or merits (e.g., occupation, educational level, moral character, etc.). Caste systems are based on a hierarchy of ascribed statuses, because people are born into fixed caste groups. A person’s occupation and opportunity for education follow from their caste position.

In a caste system, people are assigned roles regardless of their individual talents, interests, or potential. Marriage is endogamous (from endo- ‘within’ and Greek gamos ‘marriage’) which means marriage between castes is forbidden, whereas exogamous marriage is a marriage union between people from different social groups. There are virtually no opportunities to improve one’s social position. Instead, the relationship between castes is bound by institutionalized rules, and highly ritualistic procedures come into play when people from different castes come into contact. People value traditions and often devote considerable time to perfecting the details of ritualistic procedures.

The feudal systems of Europe and Japan can, in some ways, be seen as caste systems in that the statuses of positions in the social stratification systems were fixed, and there was little or no opportunity for movement through marriage or economic opportunities. In Europe, the feudal estate system divided the population into clergy (first estate), nobility (second estate), and commoners (third estate), which included artisans, merchants, and peasants. In early European feudalism, it was still possible for a peasant or a warrior to achieve a high position in the clergy or nobility, but later the divisions became more rigid. In Japan, between 1603 and 1867, the mibunsei system divided society into five rigid strata in which social standing was inherited. At the top was the Emperor, then court nobles ( kuge ), military commander-in-chief ( shogun ), and land-owning lords ( daimyo ). Beneath them were four classes or castes: the military nobility ( samurai ), peasants, craftsmen, and merchants. The merchants were considered the lowest class because they did not produce anything with their own hands. There was also an outcast or untouchable caste known as the burakumin, who were considered impure or defiled because of their association with death: executioners, undertakers, slaughterhouse workers, tanners, and butchers (Kerbo, 2006).

The caste system in India from 4,000 years ago until the 20th century probably best typifies the system of stratification. In the Hindu caste tradition, people were expected to work in the occupation of their caste and enter into marriage according to their caste. Originally there were four castes: Brahmans (priests), Kshatriyas (military), Vaisyas (merchants), and Sudras (artisans, farmers). There were also the Dalits or Harijans (“untouchables”). Hindu scripture said, “In order to preserve the universe, Brahma (the Supreme) caused the Brahmin to proceed from his mouth, the Kshatriya to proceed from his arm, the Vaishya to proceed from his thigh, and the Shudra to proceed from his foot” (Kashmeri, 1990).

Accepting this social standing was considered a moral duty. Cultural values and economic restrictions reinforced the system. Caste systems promote beliefs in fate, destiny, and the will of a higher power, rather than promoting individual freedom as a value. A person who lives in a caste society is socialized to accept their social standing, and this is reinforced by the society’s dominant norms and values.

Although the caste system in India has been officially dismantled, its residual presence in Indian society is deeply embedded. In rural areas, aspects of the tradition are more likely to remain, while urban centres show less evidence of this past. In India’s larger cities, people now have opportunities to choose their own career paths and marriage partners. As a global centre of employment, corporations have introduced merit-based hiring and employment to the nation. The caste system has been largely replaced by a class system of structured inequality. Nevertheless, Dalits continue to experience violence and discrimination in hiring or obtaining business loans (Jodhka, 2018).

The Class System

A class system is based on both socio-economic factors and individual achievement. It is at least a partially open system. A class consists of a set of people who have the same relationship to the means of production or productive property — that is, to the things used to produce the goods and services needed for survival, such as tools, technologies, resources, land, workplaces, etc. In Karl Marx’s (1848) analysis, class systems form around the institution of private property, dividing those who own or control productive property from those who do not, who survive on the basis of selling their labour. In capitalist societies, for example, the dominant classes are the capitalist class and the working class.

In a class system, social inequality is structural , meaning it is built into the organization of the economy. The relationship to the means of production (i.e., ownership/non-ownership) defines a persistent, objective pattern of social relationships that exists independently of individuals’ personal or voluntary choices and motives.

Unlike caste systems, however, class systems are open in the sense that individuals are able to change class position. Individuals are at least formally free to gain a different level of education or occupation than their parents. They can move up and down within the stratification system. They can also socialize with and marry members of other classes, allowing people to move from one class to another. In other words, individuals can move up and down the class hierarchy, even while the class categories and the class hierarchy itself remain relatively stable. It is not impossible for individuals to pass back and forth between classes through social mobility , but the class structure itself remains intact, structuring people’s lives, privileges, wealth, and social possibilities.

In a class system, one’s occupation is not fixed at birth. Though family background tends to predict where one ends up in the stratification system, personal factors play a role. For example, Ted Rogers Jr. chose a career in media like his father but managed to move upward from a position of modest wealth and privilege in the petite bourgeoisie, to being the fifth-wealthiest bourgeois in the country. On the other hand, his father Ted Sr. chose a career in radio based on individual interests that differed from his own father’s. Ted Sr.’s father, Albert Rogers, held a position as a director of Imperial Oil. Ted Sr. therefore moved downward from the class of the bourgeoisie to the class of the petite bourgeoisie.

Making Connections: Case Study

The commoner who could be queen.

On April 29, 2011, in London, England, Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, married Catherine (“Kate”) Middleton, a commoner. Throughout its history, it has been rare, though not unheard of, for a member of the British royal family to marry a commoner. Kate Middleton had an upper-middle-class upbringing. Her father was a former flight dispatcher, and her mother was a former flight attendant. The family then formed a lucrative mail order business for party accessories. William was the elder son of Charles, Prince of Wales, and Diana, Princess of Wales. Kate and William met when they were both students at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland (Köhler, 2010).

The rules regarding the marriage of royals trace their history to Britain’s formal feudal monarchy, which arose with William of Normandy’s conquest in 1066. Feudal social hierarchy was originally based on landholding. The monarch’s family (royalty) was at the top, vassals, nobles and knights (landholders) below the king, and commoners or serfs on the bottom. This was generally a closed system, with people born into positions of nobility or serfdom. Wealth was passed from generation to generation through primogeniture , a law stating that all property was to be inherited by the firstborn son. If the family had no son, the land went to the next closest male relation. Women could not inherit property, and their social standing was primarily determined through marriage. From the late feudal era onward, a royal marrying a commoner was a scandal. In 1937, the British parliament obliged Edward VIII to abdicate his succession to King of the United Kingdom, so he could marry the American divorcée, Wallis Simpson. Not only was she a commoner, but she was also divorced , which contradicted the Church of England doctrine.

The rise of capitalism changed Britain’s class structure. The feudal commoner class generated both the new dominant class of the bourgeoisie or capitalists and the new subordinate class of the proletariat or wage labourers. The aristocracy and the royals continued as a class through their wealth and property, but their position in society became increasingly based on status and tradition alone. Today, the British government is a constitutional monarchy, with the prime minister and other ministers elected to their positions. The royal family’s role is largely ceremonial. The historical differences between nobility and commoners have blurred, and the modern class system in Britain is similar to Canada. Since Edward VIII’s abdication in 1937, Queen Elizabeth II’s sister and several of her children and grandchildren have married commoners.

Today, the royal family still commands wealth, power, and a great deal of attention. In 2017, Forbes estimated the total wealth of the royal family to be $88 billion (Rodriguez, 2017). Since Queen Elizabeth II passed away in September 2022, Prince Charles has ascended the throne as king. His wife Camille Parker-Bowles, also a commoner and divorcée, is expected to become “Princess Consort.” If Charles had abdicated (chosen not to become king) or died, the position would go to Prince William. If that happened, Kate Middleton would be called Queen Catherine and hold the position of Queen Consort. She would be one of the few queens in history to have earned a university degree (Marquand, 2011). Of note here is, of course, Prince Harry, who married the commoner and divorcée Meghan Markle. Prince Harry is currently 6th in line for the British throne, after Prince William’s children. If she succeeded to Queen Consort, Meghan Markle would be the first queen with African heritage.

Initially there was a great deal of social pressure on Kate Middleton not only to behave as a royal, but to bear children. The royal family recently changed its succession laws to allow daughters, not just sons, to ascend the throne. Her firstborn son, Prince George, was born on July 22, 2013, so the new succession law is not likely to be tested in the near future. However, behind George is Princess Charlotte (b. 2015) and Prince Louis (b. 2018). Kate’s experience — from commoner to possible queen — demonstrates the fluidity of social class position in modern society.

Social Class

Social class is both obvious and not so obvious in Canadian society. It is based on subjective impressions, outward symbols, and less visible structural determinants. Can one tell a person’s education level based on clothing? Is opening an $80 bottle of wine for dinner normal, an exceptional occasion, or an insane waste of money? Can one guess a person’s income by the car they drive? There was a time in Canada when people’s class was more visibly apparent. In some countries, like the United Kingdom, class differences can still be gauged by differences in schooling, lifestyle, and even accent. In Canada, however, it is harder to determine class from outward appearances.

For sociologists, too, categorizing class is a fluid science. One debate in the discipline is between Marxist and Weberian approaches to social class (Abercrombie & Urry, 1983).

Marx’s analysis emphasizes a historical materialist approach to the underlying structures of the capitalist economy. Classes are historical formations that distribute people into categories based on the organization and structure of the economy. Marx’s definition of social class rests essentially on one materialist variable: a group’s relation to the means of production (ownership or non-ownership of productive property or capital). Therefore, in Marxist class analysis, there are two dominant classes in capitalism — the working class and the owning class — and any divisions within the classes based on occupation, status, education, etc. are less important than the tendency toward increasing separation and polarization of these two classes.

Marx referred to these two classes as the bourgeoisie and the proletariat . The capitalist class (bourgeoisie) lives from the proceeds of owning or controlling productive property (capital assets like factories, technology, software platforms or machinery, or capital itself in the form of investments, stocks, and bonds). The working class (proletariat) live from selling their labour to the capitalists for a wage or salary. Their interests are in conflict, as higher profits depend on lower wages, which accounts for the characteristic power dynamics, conflicts, instabilities and periodic crises of capitalist societies.

In addition, he described the classes of the petite bourgeoisie (the little bourgeoisie) and the lumpenproletariat (the sub-proletariat). The petite bourgeoisie are those like small business owners, farmers, and contractors who own some property and perhaps employ a few workers, but still rely on their own labour to survive. The lumpenproletariat are the chronically unemployed or irregularly employed, who are in and out of the workforce. They are what Marx referred to as the “reserve army of labour,” a pool of potential labourers who are surplus to the needs of production at any particular time.

Weber defined social class slightly differently, as the life chances one shares in common with others by virtue of possession of property, goods, skills or opportunities for income (1969). Life chances refer to the ability or probability of an individual to act on opportunities and attain a certain standard of living. Owning property or capital, or not owning property or capital, is still the basic variable that defines a person’s class situation or life chances. However, class position is defined with respect to markets rather than the process of production . It is the value of one’s capital, products or skills in the commodity or labour markets at any particular time that determines whether one has greater or fewer life chances.

This yields a model of class hierarchy based on multiple gradations of socio-economic status, instead of a division between two principle classes. Analyses of class inspired by Weber tend to emphasize gradations of status relating to several variables like wealth, income, education, and occupation. Class stratification is not just determined by a group’s economic position, but by the prestige of the group’s occupation, education level, consumption, and lifestyle. It is a matter of status — the level of honour or prestige one holds in the community by virtue of one’s social position — as much as a matter of class.

Based on the Weberian approach, some sociologists talk about upper, middle, and lower classes (with many subcategories within them) in a way that mixes status categories with class categories. These gradations are often referred to as a group’s socio-economic status ( SES ): their social position relative to others based on income, education, and prestige of occupation . For example, although plumbers might earn more than high school teachers and have greater “life chances” in a particular economy, the status division between blue-collar work (people who “work with their hands”) and white-collar work (people who “work with their minds”) means the plumbers might be characterized as lower class but teachers as middle class.

There is a randomness in the division of classes into upper, middle, and lower in the Weberian model. However, this manner of classification based on status distinctions captures something about the subjective experience of class and the shared lifestyle and consumption patterns of class that Marx’s categories often do not. An NHL hockey player receiving a salary of $6 million a year is a member of the working class, strictly speaking. He might even go on strike or get locked out according to the dynamic of capital and labour conflict described by Marx. Nevertheless, it is difficult to see what the life chances of the hockey player have in common with a landscaper or receptionist, despite the fact that they might share a common working-class background.

Class: Materialist and Interpretive Factors

Social class is a complex category to analyze. It has both a strictly materialist quality relating to a group’s structural position within the economic system, and an interpretive quality relating to the formation of status gradations, common subjective perceptions of class, differences of power in society, and class-based lifestyles and consumption patterns. Considering both the Marxist and Weberian models, social class has at least three objective components: a group’s position in the occupational structure (i.e., the status and salary of one’s job), a group’s position in the power structure (i.e., who has authority over whom), and a group’s position in the property structure (i.e., ownership or non-ownership of capital). It also has an important subjective component that relates to recognitions of status, distinctions of lifestyle, and ultimately how people perceive their place in the class hierarchy.

Making Connections: Classic Sociologists

Marx and weber on social class: how do they differ.

Often, Marx and Weber are perceived as at odds in their approaches to class and social inequality, but it is perhaps better to see them as articulating different styles of analysis.

Weber’s analysis presents a more complex model of the social hierarchy of capitalist society than Marx. Weber’s model goes beyond the economic structural class position to include the variables of status (degree of social prestige or honour) and power (degree of political influence). Thus, Weber provides a multi-dimensional model of social hierarchy. As a result, although individuals might be from the same objective class, their position in the social hierarchy might differ according to their status and political influence. For example, women and men might be equal in terms of their class position, but because of the inequality in the status of the genders within each class, women (as a group) remain lower in the social hierarchy.

With respect to class specifically, Weber also relies on a different definition than Marx. As noted above, Weber (1969) defines class as the “life chances” one shares in common with others by virtue of one’s possession of goods or opportunities for income. Class is defined with respect to markets, rather than the process of production. As in Marx’s analysis, the economic position that stems from owning property and capital, or not owning property and capital, is still the basic variable that defines one’s class situation or life chances. However, as the value of different types of capital or property (e.g., industrial, real estate, financial, etc.), or the value of different types of opportunity for income (i.e., different types of marketable skills), varies according to changes in the commodity or labour markets, Weber can provide a more nuanced description of an individual’s class position than Marx. A skilled tradesman like a pipe welder might enjoy a higher class position and greater life chances in Northern Alberta where such skills are in demand, than a high school teacher in Vancouver or Victoria where the number of qualified teachers exceeds the number of positions available. If one adds the element of status into the picture, the situation becomes even more complex, as the educational requirements and social responsibilities of the high school teacher usually confer more social prestige than the requirements and responsibilities of the pipe welder.

Nevertheless, Weber’s analysis is descriptive rather than analytical . It can provide a useful description of differences between the levels or “strata” in a social hierarchy or stratification system but does not provide an analysis of the formation of classes themselves.

On the other hand, Marx’s analysis of class is essentially one-dimensional. It has one variable: the relationship to the means of production. If one is a professional hockey player, a doctor in a hospital, or a clerk in a supermarket, one works for a wage and is therefore a member of the working class. In this regard, his analysis challenges common sense, as the difference between these different “fragments” of the working class seems paramount — at least from the point of view of the subjective experience of class. It would seem that hockey players, doctors, lawyers, professors, and business executives have very little in common with grocery clerks, factory or agricultural workers, tradespeople, or low level administrative staff, despite the fact that they all depend on being paid wages by someone.

However, the key point of Marx’s analysis is not to ignore the existence of status distinctions within classes, but to examine class structure dialectically in order to provide a more comprehensive and historical picture of class dynamics.

The four components of dialectical analysis were described in Chapter 1. An Introduction to Sociology : (1) Everything in society is related; (2) everything is caught up in a process of change; (3) change proceeds from the quantitative to the qualitative; and (4) change is the product of oppositions and struggles in society. These dialectical qualities are also central to Marx’s account of the hierarchical structure of classes in capitalist society.

With regard to the first point — everything in society is related — the main point of the dialectical analysis of class is that the working class and the owning class have to be understood in a structural relationship to one another. They emerged together out of the old class structure of feudalism. More significantly for Marx, each exists only because the other exists. The wages that define the wage labourer are paid by the capitalist; the profit and capital accumulated by the capitalist are products of the workers’ labour.

In Marx’s dialectical model, “everything is caught up in a process of change” occurs because the system is characterized by the struggle of opposites. The classes are structurally in conflict because the contradiction in their class interests is built into the economic system. The bourgeoisie as a class is defined by the economic drive to accumulate capital and increase profit. The key means to achieve this in a competitive marketplace is by reducing the cost of production by lowering the cost of labour (by reducing wages, moving production to lower wage areas, or replacing workers with labour-saving technologies). This conflicts with the interests of the proletariat who seek to establish a sustainable standard of living by maintaining their level of wages and employment in society. While individual capitalists and individual workers might not see it this way, structurally, their class interests clash and define a persistent pattern of management-labour conflict and political cleavage in modern, capitalist societies.

So, from the dialectical model, Marx can predict that the composition of classes changes over time: the statuses of different occupations vary, the proportions between workers’ income and capitalists’ profit change, and the types of production and the means of production change (through the introduction of labour-saving technologies, globalization, new products and consumption patterns, etc.). In addition, change proceeds from the quantitative to the qualitative, in the sense that the multiplicity of changes in purely quantitative variables like salary, working conditions, unemployment levels, rates of profitability, product sales, supply and demand, etc., lead to changes in qualitative variables like the subjective experience of inequality and injustice, the political divisions of “left” and “right,” the formation of class-consciousness, and eventually change in the entire economic system through new models of capital accumulation or even revolution.

The strength of Marx’s analysis is its ability to go beyond a description of where different groups fit within the class structure at a given moment in time to an analysis of why those groups and their relative positions change with respect to one another. The dialectical approach reveals the underlying logic of class structure as a dynamic system, and the potential commonality of interests and subjective experiences that define class-consciousness. As a result, in an era in which the precariousness of many high status “middle class” jobs has become clearer, the divisions of economic and political interests between the different segments of the working class becomes less so.

Media Attributions

- Figure 9.3 Office Politics: A Rise to the Top by Alex Proimos, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 licence.

- Figure 9.4 Strata in the Badlands by Just a Prairie Boy, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 9.5 Fort Mason Neighborhood by Orin Zebest, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 9.6 Woman, construction, worker, temple, india, manual, poor, labourer, labour , via PxHere, is used under a CC0 Public Domain licence.

- Figure 9.7 Royal wedding Kate & William by Gerard Stolk, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 licence.

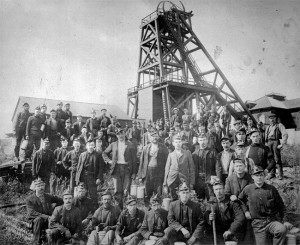

- Figure 9.8 Item B-03624 – Group of Nanaimo coal miners at the pithead by unknown photographer, [ca. 1870] (Creation) via the Royal BC Museum/ British Columbia Archives Collection (Item B-03624), is in the public domain .

- Figure 9.9 James and Laura Dunsmuir in Italian Garden at Hatley Park, by unknown photographer, 1912-1920 (Creation), courtesy of Craigdarroch Castle Society, is in the public domain .

- Figure 9.10 File:MAX WEBER.jpg by Power Renegadas, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

- Figure 9.11 Karl Marx by John Mayall, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain .

Introduction to Sociology – 3rd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2023 by William Little is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

106 Social Inequality Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Social inequality is a pervasive issue that affects individuals and communities across the globe. From economic disparities to racial discrimination, there are countless aspects of society that contribute to unequal opportunities and outcomes for different groups of people. If you are studying or researching social inequality, you may be looking for essay topics that will help you explore this complex and important issue further. To help you get started, here are 106 social inequality essay topic ideas and examples that you can use as inspiration for your next assignment:

- The impact of income inequality on health outcomes

- Gender pay gap: causes and consequences

- Educational inequality and its effects on social mobility

- The role of race in shaping access to opportunities

- Discrimination in the workplace: a case study

- Wealth inequality and its implications for society

- The digital divide: how access to technology perpetuates inequality

- Disability discrimination and social exclusion

- Intersectionality: how multiple forms of inequality intersect

- The role of social class in shaping life chances

- Housing inequality and homelessness

- Environmental justice and marginalized communities

- The criminal justice system and racial disparities

- Healthcare access and disparities in medical treatment

- LGBTQ+ rights and discrimination

- Ageism and discrimination against older adults

- The impact of globalization on income inequality

- Indigenous rights and land sovereignty

- Access to clean water and sanitation in low-income communities

- The role of social policies in reducing inequality

- Religious discrimination and freedom of worship

- Mental health stigma and access to care

- The impact of social media on perceptions of beauty and self-worth

- Immigration policy and its effects on immigrant communities

- The role of language in perpetuating inequality

- The impact of colonialism on modern-day inequality

- Food insecurity and poverty

- The effects of gentrification on low-income communities

- The role of social networks in shaping opportunities

- Disability rights and accessibility in public spaces

- The impact of incarceration on families and communities

- The intersection of race and gender in shaping experiences of inequality

- The role of education in breaking the cycle of poverty

- Affirmative action and its effects on equality

- The impact of political corruption on social inequality

- The role of media in perpetuating stereotypes and prejudice

- The effects of climate change on marginalized communities

- Worker rights and labor exploitation

- The impact of globalization on job opportunities

- The role of social movements in advocating for equality

- The effects of war and conflict on social inequality

- The impact of family structure on economic outcomes

- The role of technology in widening or narrowing the digital divide

- The effects of discrimination on mental health

- The impact of mass incarceration on communities of color

- The role of education in shaping attitudes towards inequality

- The effects of poverty on cognitive development

- The impact of housing segregation on social mobility

- The role of religion in shaping attitudes towards social inequality

- The effects of income inequality on political participation

- The impact of colonialism on indigenous cultures

- The role of social norms in perpetuating gender inequality

- The effects of income inequality on social cohesion

- The impact of war and conflict on refugee communities

- The role of social media in shaping perceptions of poverty

- The effects of discrimination on access to healthcare

- The impact of gentrification on cultural identity

- The role of education in shaping attitudes towards race

- The effects of globalization on cultural diversity

- The impact of incarceration on economic opportunities

- The role of social networks in shaping access to resources

- The effects of climate change on agricultural communities

- The impact of colonialism on indigenous languages

- The role of social norms in shaping attitudes towards disability

- The effects of income inequality on mental health

- The impact of war and conflict on children

- The role of education in shaping attitudes towards immigration

- The effects of discrimination on access to housing

- The impact of gentrification on community cohesion

- The role of religion in shaping attitudes towards poverty

- The effects of income inequality on social trust

- The impact of colonialism on indigenous rights

- The role of social media in shaping perceptions of inequality

- The effects of discrimination on access to education

- The impact of incarceration on family relationships

- The role of social networks in shaping access to employment

- The effects of climate change on coastal communities

- The impact of war and conflict on mental health

- The role of education in shaping attitudes towards gender

- The effects of globalization on cultural identity

- The impact of colonialism on indigenous traditions

- The role of social norms in perpetuating racial inequality

- The effects of income inequality on social capital

- The impact of war and conflict on refugee rights

- The role of education in shaping attitudes towards poverty

- The effects of discrimination on access to transportation

- The impact of globalization on cultural preservation

- The role of social media in shaping perceptions of discrimination

- The impact of colonialism on indigenous identities

- The role of social norms in shaping attitudes towards immigration

- The effects of discrimination on access to legal representation

- The impact of war and conflict on community resilience

- The role of education in shaping attitudes towards disability

- The effects of globalization on cultural exchange

- The impact of colonization on indigenous land rights

- The impact of war and conflict on children's rights

- The effects of discrimination on access to affordable housing

- The impact of gentrification on community development

- The role of religion in shaping attitudes towards social justice

- The effects of income inequality on social mobility

- The impact of colonialism on indigenous health

- The role of social norms in perpetuating gender stereotypes

These are just a few examples of the many ways in which social inequality can manifest in society. By choosing one of these topics (or coming up with one of your own), you can delve deeper into the complexities of this issue and explore how it impacts individuals and communities in different ways. Whether you are writing a research paper, a policy analysis, or a reflective essay, these topics will provide you with a solid foundation for exploring the causes, consequences, and potential solutions to social inequality. Good luck with your writing!

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Advertisement

Social inequalities: theories, concepts and problematics

- Published: 17 May 2021

- Volume 1 , article number 116 , ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Renato Miguel Carmo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0052-4387 1

2247 Accesses

2 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article aims to present a concise perusal of the different approaches developed in the study of social inequalities and in the relationships that they establish with manifold social processes and problems. The text does not intend to be exhaustive from the theoretical point of view, but rather to present an overview of the analytical complexity of the inequalities systems and demonstrate that they should be tackled in a multidimensional, systemic and multiscale perspective.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary on “From unidimensional to multidimensional inequality: a review”

By Way of Summary: Substantive Contributions and Public Policies for Dealing with Social Inequalities

Socio-Economic Inequalities: A Statistical Physics Perspective

Data availability.

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

The most recent configuration of the ACM typology is composed of the following class categories: “ Employers and executives are employers or directors at private companies or in the public administration. They may be recruited from any of the groups in the occupational structure. Private Professionals are self-employed and very qualified in certain specialised professions, such as lawyers, architects, and so on. Professionals and managers are employees in upper or mid-level intellectual, scientific and technical jobs. They are different from the previous category essentially because they are not self-employed. Self-employed workers work on their own account without employees in administrative or similar occupations in services and commerce. They include craftsmen and similar workers, farmers and qualified workers in agriculture and fishery. Routine employees are administrative and similar personnel, service employees and salespeople. Industrial workers are manual workers employed in less qualified occupations in construction, industry, transports, agriculture and fishery (Carmo and Nunes 2013 , p. 378).

This section is based on Carmo ( 2014 , pp. 134–138).

Aboim S (2020) Covid-19 e desigualdades de género: uma perspetiva interseccional sobre os efeitos da pandemia. In: Carmo RM, Tavares I, Cândido AF (eds) Um Olhar Sociológico sobre a Crise Covid-19 em Livro. Observatório das Desigualdades, CIES-Iscte, Lisbon, pp. 130–148: https://www.observatorio-das-desigualdades.com/2020/11/29/umolharsociologicosobreacovid19emlivro

ADB—Asian Development Bank (2012) Outlook 2012. Confronting Rising Inequality in Asia s.1., ADB.

Atkinson AB (2015) Inequality: what can be done? Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Barata A, Carmo RM (2015) O Futuro nas Mãos: de Regresso à Política do Bem-Comum. Tinta-da-China, Lisbon

Google Scholar

Bhir A, Pfefferkorn R (2008) Le system des Inégalités. La Découverte, Paris

Bourdieu P (2010[1979]) A Distinção: uma crítica social da faculdade de juízo. Edições 70, Lisbon.

Cantante F (2019) O Risco da Desigualdade. Almedina, Coimbra

Carmo RM (2009) Coesão e capital social: uma perspetiva para as políticas públicas. In: Veloso L, Carmo RM (eds) A Constituição Social da Economia. Mundos Sociais, Lisbon, pp 197–230

Carmo RM (2014) Sociologia dos Territórios: Teorias. Estruturas e Deambulações, Mundos Sociais, Lisbon

Carmo RM, Nunes N (2013) Class and social capital in Europe: a transnational analysis of the European Social Survey. Eur Soc 15(3):373–387

Article Google Scholar

Carmo RM, Rio C, Medgyesi M (eds) (2018) Reducing inequalities: a challenge for the European Union? Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Castells, M (2000) The information age. Economy, society and culture. 2ª ed., Blackwell Publishers, Oxford.

Costa AF (1998) Classificações Sociais. Leituras: Revista da Biblioteca Nacional 3(2):65–75

Costa AF (2012) Desigualdades Sociais Contemporâneas. Mundos Sociais, Lisbon

Costa AF, Mauritti R (2018) Classes sociais e interseções de desigualdades: Portugal e a Europa. In: Carmo RM et al (eds) Desigualdades Sociais: Portugal e a Europa. Mundos Sociais, Lisbon, pp 109–129

Hill Collins P (2019) Intersectionality as critical social theory. Duke University Press, Durham

Massey D (2007) World city. Polity Press, Cambridge

Milanovic B (2012) Global income inequality by the numbers: in history and know. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6259: 1–28

Milanovic B (2016) Global inequality. Cambridge, Belknap

OECD (2011) Divided we stand. Why inequality keeps rising. OECD Publications, Paris

OECD (2015) In it together: Why less inequality benefits all. OECD Publications, Paris

OECD (2018) A broken social elevator? How to promote social mobility. OECD Publications, Paris

Parkin F (1979) Marxism and class theory: a bourgeois critique. Tavistock, London

Piketty T (2020) Capital and ideology. Cambridge, Belknap

Rawls J (2001) [1971] Uma Teoria da Justiça, 2nd edn. Editorial Presença, Lisbon

Sassen S (2000) Cities in a world economy. Pine Forge Press, Thousand Oaks

Sen A (1980) Equality of What? In: McMurrin S (ed) Tanner lectures on human values, vol I. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Sen A (2003) Desenvolvimento como Liberdade. Gradiva, Lisbon

Therborn G (ed) (2006) Inequalities of the world new theoretical frameworks: multiple empirical approaches. Verso, London

Therborn G (2013) The killing fields of inequality. Polity Press, Cambridge

Tilly C (2005) Historical perspectives on inequality. In: Romero M, Margolis E (eds) The Blackwell Companion to Social Inequalities. Blackwell, Malden, pp 15–30

UNDP (2019) Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: inequalities in human development in the 21st century. Human Development Report 2019.

Wilkinson R, Pickett K (2009) The spirit level. Why more equal societies almost always do better. Allen Lane, London

Wright EO (1994) Análises de classes, história e emancipação. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais 40:3–35

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was developed within the project EmployALL—The employment crisis and the Welfare State in Portugal: deterring drivers of social vulnerability and inequality, funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (PTDC/SOC-SOC/30543/2017).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

ISCTE – University Institute of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

Renato Miguel Carmo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Renato Miguel Carmo .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Carmo, R.M. Social inequalities: theories, concepts and problematics. SN Soc Sci 1 , 116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00134-5

Download citation

Received : 11 April 2021

Accepted : 16 April 2021

Published : 17 May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00134-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Inequalities

- Social theory

- Public policy

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A Developmental Science Perspective on Social Inequality

Laura elenbaas.

1 University of Rochester

Michael T. Rizzo

2 New York University

3 Beyond Conflict Innovation Lab, Boston, MA

Melanie Killen

4 University of Maryland

Many people believe in equality of opportunity, but overlook and minimize the structural factors that shape social inequalities in the United States and around the world, such as systematic exclusion (e.g., educational, occupational) based on group membership (e.g., gender, race, socioeconomic status). As a result, social inequalities persist, and place marginalized social groups at elevated risk for negative emotional, learning, and health outcomes. Where do the beliefs and behaviors that underlie social inequalities originate? Recent evidence from developmental science indicates that an awareness of social inequalities begins in childhood, and that children seek to explain the underlying causes of the disparities that they observe and experience. Moreover, children and adolescents show early capacities for understanding and rectifying inequalities when regulating access to resources in peer contexts. Drawing on a social reasoning developmental framework, this paper synthesizes what is currently known about children’s and adolescents’ awareness, beliefs, and behavior concerning social inequalities, and highlights promising avenues by which developmental science can help reduce harmful assumptions and foster a more just society.

Despite the fact that many people believe in equality of opportunity, many also overlook the structural factors that shape social and economic disparities in the United States and around the world. These structural factors include, for example, historical and current exclusion from residential, educational, and occupational opportunities on the basis of gender, race, socioeconomic status, or other group memberships ( Bullock, 2019 ; Kraus et al., 2019 ). As a result, excluded social groups continue to have fewer opportunities for upward mobility and experience elevated risk for negative emotional, learning, and health outcomes ( Duncan & Mumane, 2011 ; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2017 ). Psychological science plays a crucial role in illuminating the processes that underlie people’s responses to social inequality. For example, research has shown that social inequalities persist in part because many people under-estimate their true magnitude, are not motivated to correct disparities that benefit their social groups, or hold negative stereotypes about marginalized groups ( Arsenio, 2018 ; Lott, 2012 ; Roberts & Rizzo, 2020 ). In order to address the psychological roots of these inequalities, we need to know where these beliefs and attitudes come from, and how we might encourage a more equitable and just understanding of the causes and consequences of social inequalities. In this paper, we offer a developmental perspective that begins to address these two questions.

In the past decade, developmental scientists have been at the forefront of efforts to understand how youth develop an awareness of social inequalities, seek explanations for their causes, form judgments of their consequences, and enact behavioral responses, based on their personal experiences with social inequalities and the influences of micro (e.g., family, peer) and macro (e.g., school, media) social contexts ( Arsenio, 2015 ; Ruck et al., 2019 ). Although children have few direct opportunities to influence societal-level inequalities (e.g., through voting, protesting), they regularly experience social inequalities in their peer and family contexts, and take on a range of different roles (e.g., perpetuator, rectifier, victim, witness) within these inequalities ( Killen et al., 2018 ). As a result, research is beginning to uncover not only the developmental processes that exacerbate social inequalities, but also potential pathways for promoting greater consideration of equity in childhood. In fact, developmental science is uniquely positioned to illuminate the factors that motivate children and adults to either ignore, exacerbate, or challenge social inequalities in their everyday interactions.

Social Reasoning Developmental Model

One branch of current research on how youth conceptualize social inequalities is informed by the social reasoning developmental (SRD) model ( Killen et al., 2018 ; Rutland et al., 2010 ). The SRD model focuses on reasoning, judgments, and decisions about moral and social issues, and how these processes change across development. It integrates concepts from social domain theory (e.g., how children reason about social-conventional, moral, and personal concerns) and social identity theory (e.g., how intra- and inter-group dynamics shape decisionmaking) to provide a framework for understanding how children make sense of moral issues (e.g., denial of resources) that occur in inter-group contexts.

The SRD model takes a constructivist view in postulating that children’s social-cognitive development stems from their reflections and abstractions based on their everyday interactions which, in turn, enable them to infer, evaluate, and judge actions and events in their world ( Killen & Rutland, 2011 ). In contrast to nativist or socialization perspectives, constructivist theories regarding the origins of social cognition emphasize the central role of the child in actively interpreting and making sense of their social world ( Killen & Smetana, 2015 ; Turiel, 1983 ). Within this broader theoretical perspective, the SRD model proposes that reasoning about morality, group identity, and the psychological states of others emerges early in childhood and coexists throughout development (see Figure 1 ). Each of these domains of knowledge are brought to bear when children and adolescents consider complex issues, such as social inequalities. What changes across development is the complexity of children’s and adolescents’ moral reasoning, the depth of their understanding of social group dynamics, their awareness of others’ mental state capacities, and their ability to coordinate and balance these overlapping concerns.

Social Reasoning Developmental (SRD) Model proposes that children and adolescents bring three forms of knowledge to bear on their reasoning about social inequalities: moral, group, and psychological.

In order to understand the orgins, development, and sources of influence on thinking about social inequalities, research from the SRD perspective has examined how children’s and adolescents’ understanding of moral, group, and psychological concepts are applied to their emerging: 1) awareness of social inequalities, 2) explanations for these inequalities, and 3) behavior aimed at increasing or reducing social inequalities. In this paper, we synthesize research from the SRD framework, as well as related research in developmental science, to outline what is currently known about children’s and adolescents’ awareness, beliefs, and behavior concerning social inequalities, and highlight promising avenues to encourage positive change.

Awareness of Social Inequalities

Being aware of social inequalities means recognizing the existence of disparities in access to resources or opportunities between social groups. On the most basic level, children are cognitively equipped to notice resource inequalities from early in development. Already in their first year of life, infants notice when someone has more toys than someone else ( Sommerville, 2018 ). By the time they reach kindergarten, children attend to wealth inequalities, identifying their peers as “poor” or “rich”, alongside other forms of social categorization (e.g., gender, ethnicity) ( Hazelbaker et al., 2018 ; Shutts, 2015 ). Over the course of adolescence, youth view U.S. society as increasingly economically stratified and also increasingly link economic status and race, associating White and Asian Americans with higher income and wealth than Black and Latinx Americans ( Arsenio & Willems, 2017 ; Ghavami & Mistry, 2019 ). However, even adults under-estimate the true extent to which wealth is unequally distributed in society, as well as the true magnitude of current racial wealth gaps ( Arsenio, 2018 ; Kraus et al., 2019 ).

Moreover, children’s own status or the status of their social group can lead them to deny or minimize the extent of social inequalities. For example, in one recent experiment, Rizzo and Killen (2020) randomly assigned 3- to 8 year-old children to either an advantaged group (had more resources than an outgroup) or a disadvantaged group (had fewer resources than an outgroup). Children assigned to the advantaged group were more likely to see the resource inequality as fair, support attempts to perpetuate the inequality, and keep more resources for their own group when given the chance.

Similarly, Elenbaas and colleagues (2016) randomly assigned European-American and African-American children, ages 5- to 6 and 10- to 11 years, to witness an experimental inequality of school supplies that placed either their racial ingroup or outgroup at a disadvantage. Young children whose ingroup was disadvantaged judged the inequality to be unfair and took steps to correct it, but young children whose outgroup was disadvantaged did not (see Figure 2 ). Older children, by contrast, rectified the inequality under both conditions and reasoned about the importance of ensuring equal access to resources (e.g., “Both schools should have the same amount of supplies for learning”).

Young children corrected a resource inequality that disadvantaged their racial ingroup but not an inequality that disadvantaged their outgroup.

From an SRD perspective, these results reveal what happens when children prioritize group concerns over moral concerns, and how the prioritization of these concerns develops during childhood. Whereas younger children in both studies struggled to balance concerns for ingroup benefit with concerns for equity, older children’s reasoning and decision-making reflected a more generalized concern for ensuring fair access to resources that took precedence over social preferences. Because ingroup concerns remain common throughout development, however, it is important to identify which social contexts enable children and adolescents to see the bigger picture and align their moral behavior with their moral judgments.

Explanations for Social Inequalities

Generating an explanation for a social inequality entails forming beliefs about how disparities in access to resources or opportunities between social groups came to be. Children and adolescents are able to consider multiple possible sources for social inequalities, and not all sources are perceived to be unfair ( Arsenio & Willems, 2017 ; Flanagan et al., 2014 ; Starmans et al., 2017 ). For instance, many people –youth and adults– explain social inequalities in terms of traditions and authority, including the need to maintain a predictable status quo and the idea that it is normal or typical for some groups to succeed and others not to. Other explanations are moral in nature. For instance, social inequalities cause direct and indirect harm to members of marginalized groups as a result of systemic discrimination and are thus in need of rectification. Finally, many explanations weigh moral, societal (economic systems), and psychological rationales, including beliefs that economic systems are designed to give everyone an equal pportunity for upward mobility and that a certain amount of inequality in society is motivating for people.

By kindergarten, children believe that greater effort entitles an individual person to a greater share of rewards (e.g., someone who tries harder at a game deserves to keep their winnings) ( Rizzo et al., 2016 ). However, when scaled up to the social group level, early-emerging judgments about merit can lead to negative stereotypes that marginalized and excluded groups “deserve” their status. For instance, young children stereotype poor peers as less competent than rich peers ( Shutts et al., 2016 ). Similarly, children hold stereotypes that African-Americans are less hardworking than European-Americans and girls are less intelligent than boys ( Bian et al., 2017 ; Pauker et al., 2016 ). In fact, although adolescents are more likely than children to generate structural explanations for social inequalities (e.g., systemic racism, classism, or sexism), these explanations typically exist alongside problematic assumptions about differences in social groups’ motivation, effort, and ingenuity, rather than replacing them ( Flanagan et al., 2014 ; Godfrey et al., 2019 ).

Explaining the underlying causes of social inequalities is challenging because observing an existing disparity (e.g., a racial disparity in access to education) does not provide enough information to infer its cause, and because the messages that children receive (e.g., from adults, media sources) about the nature and origins of social inequalities are often incomplete or ambiguous. As a result, children’s awareness and understanding of the complex structural factors underlying social inequalities (e.g., political systems that exclude the poor, residential systems that exclude ethnic minorities, educational systems that exclude girls) is limited and interacts with other cognitive biases. For example, when children are asked to generate explanations for resource inequalities between novel groups (e.g., the Orps and the Blarks), children often assume that group differences resulted from internal factors (e.g., work ethic, natural ability) rather than external factors (e.g., discrimination) ( Hussak & Cimpian, 2015 ).

Behavior in Contexts Involving Social Inequalities

Children’s and adolescents’ reasoning about the causes of social inequalities informs their thinking about what (if anything) should be done to address them. For example, in one experiment, Rizzo and colleagues (2018) tested 3- to 8-year-old children’s responses to individually-based inequalities (i.e., one peer received more prizes than another because they worked harder) or structurally-based inequalities (i.e., one peer received more prizes than another because the person giving out prizes had a gender bias). In response to the individually-based inequality, children gave more resources to the hardworking peer and reasoned about merit (e.g., “She did a better job at the activities”). In response to the structurally-based inequality, children gave more resources to the peer who had received less because of a gender bias and reasoned about equality (e.g., “They should get the same number”). These results confirm young children’s belief that individual effort should be rewarded, but also highlight emerging concerns for equity in response to structurally-based inequalities. When children had clear and unambiguous evidence that resources were allocated unjustly, they acted to correct the disparity.

Similarly, one recent experiment informed early adolescents that access to an educational opportunity (a science summer camp) had historically been restricted such that only wealthy children or only poor children had attended ( Elenbaas, 2019a ). When they had the chance to determine who should attend the camp “this summer,” participants favored the group that had been excluded in the past, particularly when that group was poor. Moreover, the larger the economic “gap” in access to opportunities that participants perceived in broader society, the more they supported including poor peers in this particular opportunity (see Figure 3 ) and reasoned about fair access to learning (e.g., “Everyone has the right to education no matter what background they come from”).

Early adolescents who perceived a larger economic “gap” in access to opportunities in favor of high-wealth peers were more supportive of including low-wealth peers in a learning opportunity.

These studies, both drawing on the SRD model to understand children’s and adolescents’ reasoning and behavior in contexts involving moral issues (differential access to resources and opportunities) on inter-group levels (involving gender or social class), have intriguing implications for how to reduce harmful stereotypes about the causes of social inequalities. When children know –from their own direct observations or from others’ testimony– that an inequality is rooted in structural discrimination or bias, most children support efforts to reduce it. The challenge is that children rarely receive this direct and unambiguous evidence. While the idea that anyone can achieve success with enough effort and ambition is widely available to children in national, social, and educational discourse, children receive far less consistent information about the historical and societal contexts for why some social groups are advantaged over others. However, this may offer a point of entry for adults interested in increasing children’s recognition of the complex structural causes of social inequalities.

Supporting Complex Reasoning about Social Inequalities

Providing opportunities for analysis and reflection on the sources and consequences of social inequalities may help youth develop a critical understanding of the social, economic, and political systems that they are a part of ( Seider et al., 2018 ). For example, research on family racial-ethnic socialization indicates that conversations about discrimination can contribute to adolescents’ structural explanations for social inequalities (e.g., systemic racism) ( Bañales et al., 2019 ). Similarly, research on civic engagement has shown that adolescents who frequently discuss current events with their parents have a better understanding of structural contributors to poverty ( Flanagan et al., 2014 ). Likewise, research on critical consciousness indicates that discussions with parents, teachers, mentors, and peers can foster adolescents’ awareness of sociopolitical conditions and motivation to address social inequalities ( Diemer et al., 2016 ). Although little research has examined the messages about social inequality that pre-adolescent children may receive, they, too, are becoming aware of social inequalities, and likely consider their parents’ and teachers’ opinions when forming beliefs about their causes.

Relationships with peers whose experiences differ from their own may also help youth reject stereotypes and develop a deeper understanding of social inequalities. For instance, research on inter-group contact indicates that having a friend from a different racial background is associated with lower racial stereotypes ( Aboud & Brown, 2013 ). Similarly, cross-SES friendships may encourage children’s fairness reasoning. In one recent study, children from zupper-middle income families who reported more contact with peers from lower-income backgrounds were more likely to reason about differences in access to resources when sharing toys, and shared more equitably ( Elenbaas, 2019b ). Although, it is not yet known whether interactions with higher-SES peers have a similar impact on lower-SES children’s reasoning, these results point to how everyday interactions with friends may raise children’s consideration of the immediate consequences of resource disparities.

Future Directions for Research

Understanding children’s and adolescents’ thinking about social inequality is a new area of research in developmental science ( Ruck et al., 2019 ). We now know that youth face challenges in becoming aware of the existence and extent of social inequalities, understanding their structural causes, and deciding how to address social inequalities. Moreover, both the potential for ingroup benefit and negative stereotypes about disadvantaged groups lead to more exclusive and inequitable behavior.