ESL Speaking

Games + Activities to Try Out Today!

in Activities for Adults · Activities for Kids · ESL Speaking Resources

Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching: CLT, TPR

Teaching a foreign language can be a challenging but rewarding job that opens up entirely new paths of communication to students. It’s beneficial for teachers to have knowledge of the many different language learning techniques including ESL teaching methods so they can be flexible in their instruction methods, adapting them when needed.

Keep on reading for all the details you need to know about the most popular foreign language teaching methods. Some of the ESL pedagogy ideas covered are the communicative approach, total physical response, the direct method, task-based language learning, suggestopedia, grammar-translation, the audio-lingual approach and more.

Language teaching methods

Most Popular Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching

Here’s a helpful rundown of the most common language teaching methods and ESL teaching methods. You may also want to take a look at this: Foreign language teaching philosophies .

#1: The Direct Method

In the direct method ESL, all teaching occurs in the target language, encouraging the learner to think in that language. The learner does not practice translation or use their native language in the classroom. Practitioners of this method believe that learners should experience a second language without any interference from their native tongue.

Instructors do not stress rigid grammar rules but teach it indirectly through induction. This means that learners figure out grammar rules on their own by practicing the language. The goal for students is to develop connections between experience and language. They do this by concentrating on good pronunciation and the development of oral skills.

This method improves understanding, fluency , reading, and listening skills in our students. Standard techniques are question and answer, conversation, reading aloud, writing, and student self-correction for this language learning method. Learn more about this method of foreign language teaching in this video:

#2: Grammar-Translation

With this method, the student learns primarily by translating to and from the target language. Instructors encourage the learner to memorize grammar rules and vocabulary lists. There is little or no focus on speaking and listening. Teachers conduct classes in the student’s native language with this ESL teaching method.

This method’s two primary goals are to progress the learner’s reading ability to understand literature in the second language and promote the learner’s overall intellectual development. Grammar drills are a common approach. Another popular activity is translation exercises that emphasize the form of the writing instead of the content.

Although the grammar-translation approach was one of the most popular language teaching methods in the past, it has significant drawbacks that have caused it to fall out of favour in modern schools . Principally, students often have trouble conversing in the second language because they receive no instruction in oral skills.

#3: Audio-Lingual

The audio-lingual approach encourages students to develop habits that support language learning. Students learn primarily through pattern drills, particularly dialogues, which the teacher uses to help students practice and memorize the language. These dialogues follow standard configurations of communication.

There are four types of dialogues utilized in this method:

- Repetition, in which the student repeats the teacher’s statement exactly

- Inflection, where one of the words appears in a different form from the previous sentence (for example, a word may change from the singular to the plural)

- Replacement, which involves one word being replaced with another while the sentence construction remains the same

- Restatement, where the learner rephrases the teacher’s statement

This technique’s name comes from the order it uses to teach language skills. It starts with listening and speaking, followed by reading and writing, meaning that it emphasizes hearing and speaking the language before experiencing its written form. Because of this, teachers use only the target language in the classroom with this TESOL method.

Many of the current online language learning apps and programs closely follow the audio-lingual language teaching approach. It is a nice option for language learning remotely and/or alone, even though it’s an older ESL teaching method.

#4: Structural Approach

Proponents of the structural approach understand language as a set of grammatical rules that should be learned one at a time in a specific order. It focuses on mastering these structures, building one skill on top of another, instead of memorizing vocabulary. This is similar to how young children learn a new language naturally.

An example of the structural approach is teaching the present tense of a verb, like “to be,” before progressing to more advanced verb tenses, like the present continuous tense that uses “to be” as an auxiliary.

The structural approach teaches all four central language skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. It’s a technique that teachers can implement with many other language teaching methods.

Most ESL textbooks take this approach into account. The easier-to-grasp grammatical concepts are taught before the more difficult ones. This is one of the modern language teaching methods.

Most popular methods and approaches and language teaching

#5: Total Physical Response (TPR)

The total physical response method highlights aural comprehension by allowing the learner to respond to basic commands, like “open the door” or “sit down.” It combines language and physical movements for a comprehensive learning experience.

In an ordinary TPR class, the teacher would give verbal commands in the target language with a physical movement. The student would respond by following the command with a physical action of their own. It helps students actively connect meaning to the language and passively recognize the language’s structure.

Many instructors use TPR alongside other methods of language learning. While TPR can help learners of all ages, it is used most often with young students and beginners. It’s a nice option for an English teaching method to use alongside some of the other ones on this list.

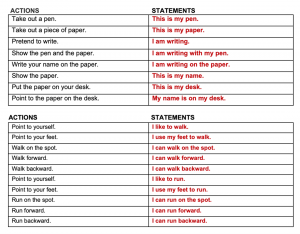

An example of a game that could fall under TPR is Simon Says. Or, do the following as a simple review activity. After teaching classroom vocabulary, or prepositions, instruct students to do the following:

- Pick up your pencil.

- Stand behind someone.

- Put your water bottle under your chair.

Are you on your feet all day teaching young learners? Consider picking up some of these teacher shoes .

#6: Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

These days, CLT is by far one of the most popular approaches and methods in language teaching. Keep reading to find out more about it.

This method stresses interaction and communication to teach a second language effectively. Students participate in everyday situations they are likely to encounter in the target language. For example, learners may practice introductory conversations, offering suggestions, making invitations, complaining, or expressing time or location.

Instructors also incorporate learning topics outside of conventional grammar so that students develop the ability to respond in diverse situations.

- Amazon Kindle Edition

- Bolen, Jackie (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 301 Pages - 12/21/2022 (Publication Date)

CLT teachers focus on being facilitators rather than straightforward instructors. Doing so helps students achieve CLT’s primary goal, learning to communicate in the target language instead of emphasizing the mastery of grammar.

Role-play , interviews, group work, and opinion sharing are popular activities practiced in communicative language teaching, along with games like scavenger hunts and information gap exercises that promote student interaction.

Most modern-day ESL teaching textbooks like Four Corners, Smart Choice, or Touchstone are heavy on communicative activities.

#7: Natural Approach

This approach aims to mimic natural language learning with a focus on communication and instruction through exposure. It de-emphasizes formal grammar training. Instead, instructors concentrate on creating a stress-free environment and avoiding forced language production from students.

Teachers also do not explicitly correct student mistakes. The goal is to reduce student anxiety and encourage them to engage with the second language spontaneously.

Classroom procedures commonly used in the natural approach are problem-solving activities, learning games , affective-humanistic tasks that involve the students’ own ideas, and content practices that synthesize various subject matter, like culture.

#8: Task-Based Language Teaching (TBL)

With this method, students complete real-world tasks using their target language. This technique encourages fluency by boosting the learner’s confidence with each task accomplished and reducing direct mistake correction.

Tasks fall under three categories:

- Information gap, or activities that involve the transfer of information from one person, place, or form to another.

- Reasoning gap tasks that ask a student to discover new knowledge from a given set of information using inference, reasoning, perception, and deduction.

- Opinion gap activities, in which students react to a particular situation by expressing their feelings or opinions.

Popular classroom tasks practiced in task-based learning include presentations on an assigned topic and conducting interviews with peers or adults in the target language. Or, having students work together to make a poster and then do a short presentation about a current event. These are just a couple of examples and there are literally thousands of things you can do in the classroom. In terms of ESL pedagogy, this is one of the most popular modern language teaching methods.

It’s considered to be a modern method of teaching English. I personally try to do at least 1-2 task-based projects in all my classes each semester. It’s a nice change of pace from my usually very communicative-focused activities.

One huge advantage of TBL is that students have some degree of freedom to learn the language they want to learn. Also, they can learn some self-reflection and teamwork skills as well.

#9: Suggestopedia Language Learning Method

This approach and method in language teaching was developed in the 1970s by psychotherapist Georgi Lozanov. It is sometimes also known as the positive suggestion method but it later became sometimes known as desuggestopedia.

Apart from using physical surroundings and a good classroom atmosphere to make students feel comfortable, here are some of the main tenants of this second language teaching method:

- Deciphering, where the teacher introduces new grammar and vocabulary.

- Concert sessions, where the teacher reads a text and the students follow along with music in the background. This can be both active and passive.

- Elaboration where students finish what they’ve learned with dramas, songs, or games.

- Introduction in which the teacher introduces new things in a playful manner.

- Production, where students speak and interact without correction or interruption.

TESOL methods and approaches

#10: The Silent Way

The silent way is an interesting ESL teaching method that isn’t that common but it does have some solid footing. After all, the goal in most language classes is to make them as student-centred as possible.

In the Silent Way, the teacher talks as little as possible, with the idea that students learn best when discovering things on their own. Learners are encouraged to be independent and to discover and figure out language on their own.

Instead of talking, the teacher uses gestures and facial expressions to communicate, as well as props, including the famous Cuisenaire Rods. These are rods of different colours and lengths.

Although it’s not practical to teach an entire course using the silent way, it does certainly have some value as a language teaching approach to remind teachers to talk less and get students talking more!

#11: Functional-Notional Approach

This English teaching method first of all recognizes that language is purposeful communication. The reason people talk is that they want to communicate something to someone else.

Parts of speech like nouns and verbs exist to express language functions and notions. People speak to inform, agree, question, persuade, evaluate, and perform various other functions. Language is also used to talk about concepts or notions like time, events, places, etc.

The role of the teacher in this second language teaching method is to evaluate how students will use the language. This will serve as a guide for what should be taught in class. Teaching specific grammar patterns or vocabulary sets does play a role but the purpose for which students need to know these things should always be kept in mind with the functional-notional Approach to English teaching.

#12: The Bilingual Method

The bilingual method uses two languages in the classroom, the mother tongue and the target language. The mother tongue is briefly used for grammar and vocabulary explanations. Then, the rest of the class is conducted in English. Check out this video for some of the pros and cons of this method:

#13: The Test Teach Test Approach (TTT)

This style of language teaching is ideal for directly targeting students’ needs. It’s best for intermediate and advanced learners. Definitely don’t use it for total beginners!

There are three stages:

- A test or task of some kind that requires students to use the target language.

- Explicit teaching or focus on accuracy with controlled practice exercises.

- Another test or task is to see if students have improved in their use of the target language.

Want to give it a try? Find out what you need to know here:

Test Teach Test TTT .

#14: Community Language Learning

In Community Language Learning, the class is considered to be one unit. They learn together. In this style of class, the teacher is not a lecturer but is more of a counsellor or guide.

In general, there is no set lesson for the day. Instead, students decide what they want to talk about. They sit in the a circle, and decide on what they want to talk about. They may ask the teacher for a translation or for advice on pronunciation or how to say something.

The conversations are recorded, and then transcribed. Students and teacher can analyze the grammar and vocabulary, as well as subject related content.

While community language learning may not comprehensively cover the English language, students will be learning what they want to learn. It’s also student-centred to the max. It’s perhaps a nice change of pace from the usual teacher-led classes, but it’s not often seen these days as the only method of teaching a class.M

#15: The Situational Approach

This approach loosely falls under the behaviourism view of language as habit formation. The situational approach to teaching English was popular in England, starting in the 1930s. Find out more about it:

Language Teaching Approaches FAQs

There are a number of common questions that people have about second or foreign language teaching and learning. Here are the answers to some of the most popular ones.

What is language teaching approaches?

A language teaching approach is a way of thinking about teaching and learning. An approach produces methods, which is the way of teaching something, in this case, a second or foreign language using techniques or activities.

What are method and approach?

Method and approach are similar but there are some key differences. An approach is the way of dealing with something while a method involves the process or steps taken to handle the issue or task.

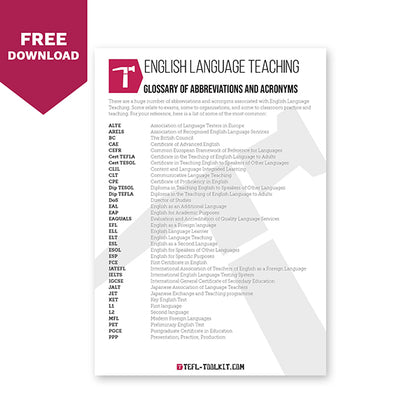

What is presentation practice production?

How many approaches are there in language learning?

Throughout history, there have been just over 30 popular approaches to language learning. However, there are around 10 that are most widely known including task-based learning, the communicative approach, grammar-translation and the audio-lingual approach. These days, the communicative approach is all the rage.

What is the best method of English language teaching?

It’s difficult to choose the best single approach or method for English language teaching as the one used depends on the age and level of the students as well as the material being taught. Most teachers find that a mix of the communicative approach, audio-lingual approach and task-based teaching works well in most cases.

What is micro teaching?

What are the most effective methods of learning a language?

The most effective methods for learning a language really depends on the person, but in general, here are some of the best options: total immersion, the communicative approach, extensive reading, extensive listening, and spaced repetition.

The Modern Methods of Teaching English

There are several modern methods of teaching English that focus on engaging students and making learning more interactive and effective. Some of these methods include:

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

This approach emphasizes communication and interaction as the main goals of language learning. It focuses on real-life situations and encourages students to use English in meaningful contexts.

Task-Based Learning (TBL)

TBL involves designing activities or tasks that require students to use English to complete a specific goal or objective. This approach helps students develop language skills while focusing on the task at hand.

Technology-Enhanced Learning

Using technology such as computers, tablets, and smartphones can make learning more engaging and interactive. Online resources, apps, and educational games can be used to supplement traditional teaching methods.

Flipped Classroom

In a flipped classroom, students learn new material at home through videos or online resources, and then use class time for activities, discussions, and practice exercises. This approach allows for more individualized learning and interaction in the classroom.

Project-Based Learning (PBL)

PBL involves students working on projects or tasks that require them to use English in a real-world context. This approach helps students develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills while improving their language abilities.

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL)

CLIL involves teaching subjects such as science or history in English, rather than teaching English as a separate subject. This approach helps students learn English while also learning about other subjects.

Gamification

Using game elements such as points, badges, and leaderboards can make learning English more fun and engaging. Educational games can help students practice language skills in a playful and interactive way.

These modern methods of teaching English focus on making learning more student-centered, interactive, and engaging, leading to better outcomes for students.

Have your say about Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching

What’s your top pick for a language teaching method? Is it one of the options from this list or do you have another one that you’d like to mention? Leave a comment below and let us know what you think. We’d love to hear from you. And whatever approach or method you use, you’ll want to check out these top 1o tips for new English teachers .

Also, be sure to give this article a share on Facebook, Pinterest, or Twitter. It’ll help other busy teachers, like yourself, find this useful information about approaches and methods in language teaching and learning.

Last update on 2024-04-25 / Affiliate links / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API

About Jackie

Jackie Bolen has been teaching English for more than 15 years to students in South Korea and Canada. She's taught all ages, levels and kinds of TEFL classes. She holds an MA degree, along with the Celta and Delta English teaching certifications.

Jackie is the author of more than 100 books for English teachers and English learners, including 101 ESL Activities for Teenagers and Adults and 1001 English Expressions and Phrases . She loves to share her ESL games, activities, teaching tips, and more with other teachers throughout the world.

You can find her on social media at: YouTube Facebook TikTok Pinterest Instagram

This is wonderful, I have learned a lot!

You’re welcome!

What year did you publish this please?

Recently! Only a few months ago.

Wonderful! Thank you for sharing such useful information. I have learned a lot from them. Thank you!

I am so grateful. Thanks for sharing your kmowledge.

Hi thank you so much for this amazing article. I just wanted to confirm/ask is PPP one of the methods of teaching ESL if so was there a reason it wasn’t included in the article(outdated, not effective etc.?).

PPP is more of a subset of these other ones and not an approach or method in itself.

Good explanation, understandable and clear. Congratulations

That’s good, very short but clear…👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

I meant the naturalistic approach

This is amazing! Thank you for writing this article, it helped me a lot. I hoped this will reach more people so I will definitely recommend this to others.

Thank you, sir! I just used this article in my PPT presentation at my Post Grad School. More articles from you!

I think this useful because it is teaching me a lot about english. Thank you bro! 😀👍

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Our Top-Seller

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

More ESL Activities

Five Letter Words Without Vowels | No Vowel Words

List of Text Slang, Definitions, and Examples | Chat Abbreviations

200+ List of Categories | Different Types of Categories

List of Common American Foods with Pictures

About, contact, privacy policy.

Jackie Bolen has been talking ESL speaking since 2014 and the goal is to bring you the best recommendations for English conversation games, activities, lesson plans and more. It’s your go-to source for everything TEFL!

About and Contact for ESL Speaking .

Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

Email: [email protected]

Address: 2436 Kelly Ave, Port Coquitlam, Canada

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Key Foreign Language Teaching Methods

How do you teach your foreign language students?

Consider for a moment the manners in which you teach reading , writing, listening, speaking, grammar and culture . Why do you use those methods?

In my experience, knowing the history of how your subject has been taught will help you understand your teaching methods.

It will also help you learn to select the best ones for your students at any given moment.

Read on for the most common foreign language teaching methods of today, as well as how to choose which ones to employ.

Grammar-translation

Audio-lingual, total physical response, communicative, task-based learning, community language learning, the silent way, functional-notional, other methods, how to choose a foreign language teaching method.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Those who’ve studied an ancient language like Latin or Sanskrit have likely used this method . It involves learning grammar rules, reading original texts and translating both from and into the target language.

You don’t really learn to speak—although, to be fair, it’s hard to practice speaking languages that have no remaining native speakers.

For the longest time, this approach was also commonly used for teaching modern foreign languages. Though it’s fallen out of favor, there are some benefits to it for occasional use.

With grammar-translation , you might give your students a brief passage in the target language, provide the new vocabulary and give them time to try translating. The reading might include a new verb tense, a new case or a complex grammatical construction.

When it occurs, speaking might only consist of a word or phrase and is typically in the context of completing the exercises. Explanations of the material are in the native language.

After the assignment, you could give students a series of translation sentences or a brief paragraph in the native language for them to translate into the target language as homework.

The direct method , also known as the natural approach, was a response to the grammar-translation method. Here, the emphasis is on the spoken language.

Based on observations of children learning their native tongues, this approach centers on listening and comprehension at the beginning of the language learning process.

Lessons are taught in the target language —in fact, the native language is strictly forbidden. A typical lesson might involve viewing pictures while the teacher repeats the vocabulary words, then listening to recordings of these words used in a comprehensible dialogue.

Once students have had time to listen and absorb the sounds of the target language, speaking is encouraged at all times, especially because grammar instruction isn’t taught explicitly.

Rather, students should learn grammar inductively. Allow them to use the language naturally, then gently correct mistakes and give praise to proper language usage. (Note that many have found this method of grammar instruction insufficient.)

Direct method activities might include pantomiming, word-picture association, question-answer patterns, dialogues and role playing.

The theory behind the audio-lingual approach is that repetition is the mother of all learning. This methodology emphasizes drill work in order to make answers to questions instinctive and automatic.

This approach gives highest priority to the spoken form of the target language. New information is first heard by students; written forms come only after extensive drilling. Classes are generally held in the target language.

An example of an audio-lingual activity is a substitution drill. The instructor might start with a basic sentence, such as “I see the ball.” Then they hold up a series of other photos for students to substitute for the word “ball.” These exercises are drilled into students until they get the pronunciations and rhythm right.

The audio-lingual approach borrows from the behaviorist school of psychology, so languages are taught through a system of reinforcement . Reinforcements are anything that makes students feel good about themselves or the situation—clapping, a sticker, etc.

Full immersion is difficult to achieve in a foreign language classroom—unless, of course, you’re teaching that language in a country where it’s spoken and your students are doing everything in the target language.

For example, ESL students have an immersion experience if they’re studying in an Anglophone country. In addition to studying English, they either work or study other subjects in English for the complete experience.

Attempts at this methodology can be seen in foreign language immersion schools, which are becoming popular in certain districts in the US. The challenge is that, as soon as students leave school, they are once again surrounded by the native language.

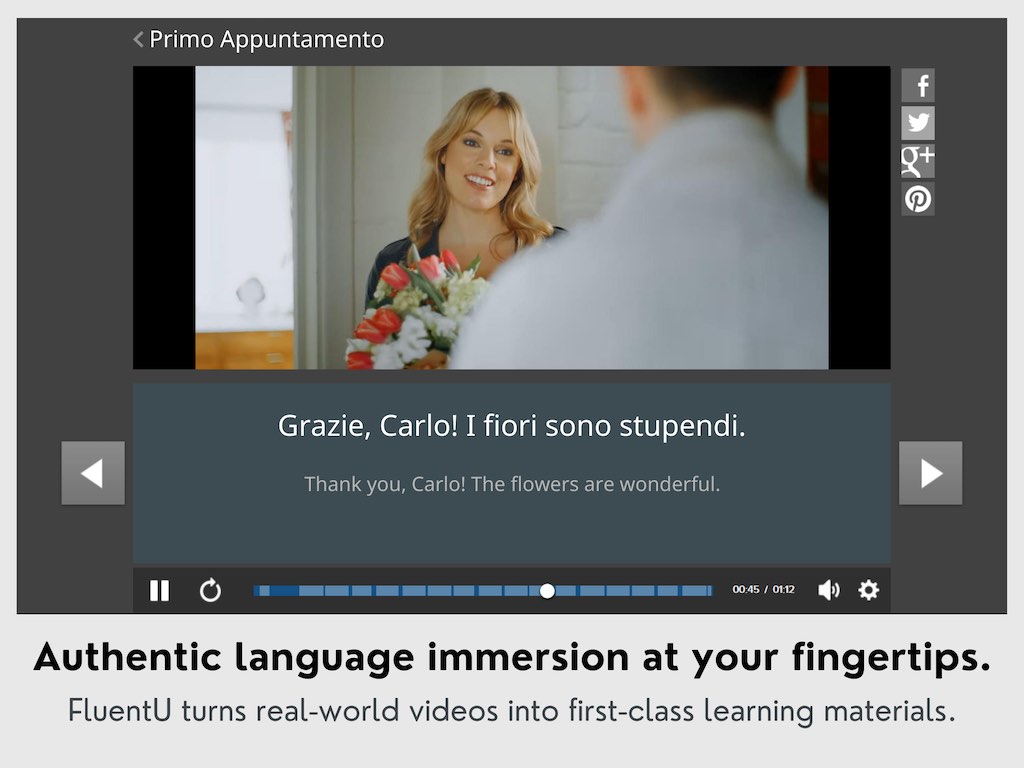

One way to get closer to the core of this method is to use an online language immersion program, such as FluentU . The authentic videos are made by and for native speakers and come with a multitude of learning tools.

Try FluentU for FREE!

Expert-vetted, interactive subtitles provide definitions, photo references, example sentences and more. Each lesson contains a quiz personalized to every individual student.

You can also import your own flashcard lists and assign tasks directly to learners with FluentU in order to encourage immersive learning outside of class.

Also known as TPR , this teaching method emphasizes aural comprehension. Gestures and movements play a vital role in this approach.

Children learning their native language hear lots of commands from adults: “Catch the ball,” “Pick up your toy,” “Drink your water.” TPR aims to teach learners a second language in the same manner with as little stress as possible.

The idea is that when students see movement and move themselves, their brains create more neural connections, which makes for more efficient language acquisition.

In a TPR-based classroom, students are therefore trained to respond to simple commands: stand up, sit down, close the door, open your book, etc.

The teacher might demonstrate what “jump” looks like, for example, and then ask students to perform the action themselves. Or, you might simply play Simon Says!

This style can later be expanded to storytelling , where students act out actions from an oral narrative, demonstrating their comprehension of the language.

The communicative approach is the most widely used and accepted approach to classroom-based foreign language teaching today.

It emphasizes the learner’s ability to communicate various functions, such as asking and answering questions, making requests, describing, narrating and comparing.

Task assignment and problem solving —two key components of critical thinking—are the means through which the communicative approach operates.

A communicative classroom includes activities where students can work out a problem or situation through narration or negotiation—composing a dialogue about when and where to eat dinner, for instance, or creating a story based on a series of pictures.

This helps them establish communicative competence and learn vocabulary and grammar in context. Error correction is de-emphasized so students can naturally develop accurate speech through frequent use. Language fluency comes through communicating in the language rather than by analyzing it.

Task-based learning is a refinement of the communicative approach and focuses on the completion of specific tasks through which language is taught and learned.

The purpose is for language learners to use the target language to complete a variety of assignments. They will acquire new structures, forms and vocabulary as they go. Typically, little error correction is provided.

In a task-based learning environment, three- to four-week segments are devoted to a specific topic, such as ecology, security, medicine, religion, youth culture, etc. Students learn about each topic step-by-step with a variety of resources.

Activities are similar to those found in a communicative classroom, but they’re always based around the theme. A unit often culminates in a final project such as a written report or presentation.

In this type of classroom, the teacher serves as a counselor rather than an instructor.

It’s called community language learning because the class learns together as one unit —not by listening to a lecture, but by interacting in the target language.

For instance, students might sit in a circle. You don’t need a set lesson since this approach is learner-led; the students will decide what they want to talk about.

Someone might say, “Hey, why don’t we talk about the weather?” The student will turn to the teacher ( standing outside the circle ) and ask for the translation of this statement. The teacher will provide the translation and ask the student to say it while guiding their pronunciation.

When the pronunciation is correct, the student will repeat the statement to the group. Another student might then say, “I had to wear three layers today!” And the process repeats.

These conversations are always recorded and then transcribed and mined for lesson continuations featuring grammar, vocabulary and subject-related content.

Proponents of this approach believe that teaching too much can sometimes get in the way of learning. It’s argued that students learn best when they discover rather than simply repeat what the teacher says.

By saying as little as possible, you’re encouraging students to do the talking themselves to figure out the language. This is seen as a creative, problem-solving process —an engaging cognitive challenge.

So how does one teach in silence ?

You’ll need to employ plenty of gestures and facial expressions to communicate with your students.

You can also use props. A common prop is Cuisenaire Rods —rods of different colors and lengths. Pick one up and say “rod.” Pick another, point at it and say “rod.” Repeat until students understand that “rod” refers to these objects.

Then, you could pick a green one and say “green rod.” With an economy of words, point to something else green and say, “green.” Repeat until students get that “green” refers to the color.

The functional-notional approach recognizes language as purposeful communication. That is, we use it because we need to communicate something.

Various parts of speech exist because we need them to express functions like informing, persuading, insinuating, agreeing, questioning, requesting, evaluating, etc. We also need to express notions (concepts) such as time, events, action, place, technology, process, emotion, etc.

Teachers using the functional-notional method must evaluate how the students will be using the language .

For example, very young kids need language skills to help them communicate with their parents and friends. Key social phrases like “thank you,” “please” or “may I borrow” are ideal here.

For business professionals, you might want to teach the formal forms of the target language, how to delegate tasks and how to vocally appreciate a job well done. Functions could include asking a question, expressing interest or negotiating a deal. Notions could be prices, quality or quantity.

You can teach grammar and sentence patterns directly, but they’re always subsumed by the purpose for which the language will be used.

A student who wants to learn with the reading method probably never intends to interact with native speakers in the target language.

Perhaps they’re a graduate student who simply needs to read scholarly articles. Maybe they’re a culinary student who only wants to understand the French techniques in her cookbook.

Whoever it is, these students only require one linguistic skill: reading comprehension.

Do away with pronunciation and dialogues. No need to practice listening or speaking, or even much (if any) writing.

With the reading approach, simply help your students build their vocabulary. They’ll likely need a lot of specialized words in a specific field, though they’ll also need to know elements like conjunctions and negation—enough grammar to make it through a standard article in their field.

These approaches are not necessarily as common in the classroom setting but deserve a mention nonetheless:

- Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL): A number of commercial products ( Pimsleur , Rosetta Stone ) and online products ( Duolingo , Babbel ) use the CALL method. With careful planning, you can likely employ some in the classroom as well.

- Cognitive-code: Developed in response to the audio-lingual method , this approach requires essential language structures to be explicitly laid out in examples (dialogues, readings) by the teacher, with lots of opportunities for students to practice .

- Suggestopedia: The idea here is that the more relaxed and comfortable students feel, the more open they are to learning , which therefore makes language acquisition easier.

Now that you know a number of methodologies and how to use them in the classroom, how do you choose the best?

You should always try to choose the methods and approaches that are most effective for your students. After all, our job as teachers is to help our students to learn in the best way for them— not for us or for researchers or for administrators.

So, the best teachers choose the best methodology and the best approach for each lesson or activity. They aren’t wedded to any particular methodology but rather use principled eclecticism:

- Ever taught a grammatical construction that only appears in written form? Had your students practice it by writing? Then you’ve used the grammar-translation method.

- Ever talked to your students in question/answer form, hoping they’d pick up the grammar point? Then you’ve used the direct method.

- Every repeatedly drilled grammatical endings, or numbers, or months, perhaps before showing them to your students? Then you’ve used the audio-lingual method.

- Ever played Simon Says? Or given your students commands to open their textbook to a certain page? Then you’ve used the total physical response method.

- Ever written a thematic unit on a topic not covered by the textbook, incorporating all four skills and culminating in a final assignment? Then you’ve used task-based learning.

If you’ve already done all of these, then you’re already practicing principled eclecticism!

The point is: The best teachers make use of all possible approaches at the appropriate time, for the appropriate activities and for those students whose learning styles require that approach.

The ultimate goal is to choose the foreign language teaching methods that best fit your students, not to force them to adhere to a particular or method.

Remember: Teaching is always about our students! You got this!

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Learning Module One: Overview of Language Teaching Methodologies

Introduction.

Five approaches and/or methods are presented in this module as a foundational backdrop to current language teaching methodologies. This module answers the question “What approaches or methods used in the past have influenced current language teaching methodologies?

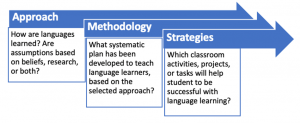

The terms ‘approach’ and ‘method’ are often used synonymously, but a distinction should be made. An approach is a broad term used to describe a set of beliefs or assumptions about the nature of language learning. A method (also called methodology ) describes a systematic plan for language teaching that follows a selected approach. Strategies (sometimes called techniques) are actions, tasks, or activities that support a language teaching methodology. Strategies bring a selected methodology to life in the classroom.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan.

Brief video explanations are available here:

- International TEFL & TESOL Training (2017). Theories, Methods, and Techniques of Teaching. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLbVib986kwejHLSDSDglLNPaZtt2uizzc

(1) Grammar Translation Method

This is by far the oldest method of language teaching, dating back several centuries. The original purpose was to translate classic literature from Ancient Latin and Greek into modern languages.

Key Features

In this method, students learn grammatical features of the target language. They are given practice exercises such as grammar drills and sentence translations. The aim is for students to be able to translate with ease between two languages, usually their first or native language (L1) and the target language (L2) being learned. Students begin with basic sentence translations and progress to paragraphs and longer texts. Translation demands high levels of proficiency with written text. Students must understand both the context and meaning in order to translate messages accurately from one language to the other.

- A major weakness is the intense focus on reading, writing, and grammar without equal attention to oral communication skills. The ability to communicate with others orally is not the focus of this method. Note: Translation should not be confused with interpretation , which is oral.

- Another weakness is the lack of interaction for real-life, authentic communication. The grammar-translation method is static, requiring interaction between the reader and text. Authentic communication is active and engaging, comprised of listening, speaking, reading, and writing for various purposes with different target audiences.

- A third weakness is an overemphasis on grammatical accuracy and the memorization of grammatical rules, making language learning a rules-driven rather than communication-driven academic pursuit.

Translate the following English paragraph to another language that you know.

‘ Anne of Green Gables’ by Canadian author L. M. Montgomery offers hours of enjoyable reading for pre-teens. This book recounts the life of an 11-year old red-headed orphan girl named Anne Shirley. Anne is adopted by an elderly brother and sister, Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert, who live on a farm called Green Gables. The farm is near the town of Avonlea on Prince Edward Island. Matthew and Marilla had hoped to adopt a boy to help on the farm. Instead, they receive a very curious, outspoken, and imaginative girl. Anne brings many unexpected adventures to Matthew, Marilla, and the residents of Avonlea.

Credit: Nadia Prokopchuk

(2) the natural approach.

In the mid-20th century, linguists recognized that the grammar-translation method had many shortcomings. Krashen and Terrell (1983) proposed a new methodology stemming from Terrell’s belief in the Natural Approach (1977). The approach described the process of learning a new language as being similar to the acquisition of a first language in childhood. Krashen further explained that language acquisition involves spontaneous, experiential learning, and language input from many sources. Krashen added five hypotheses to Terrell’s theory.

a) Acquisition-learning hypothesis – L2 is acquired in a manner parallel to L1. Acquisition, or absorbing the language naturally, is not the same as learning in a classroom (studying the language and its rules).

b) Natural order hypothesis – The brain retains grammatical rules subconsciously in a natural order. Teachers should expect errors during language acquisition, knowing that rules are being absorbed naturally.

c) Monitor hypothesis – Self-correction, a kind of internal monitor, helps students to gain control of the grammatical features of language over time.

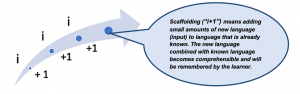

d) Input hypothesis – Students acquire new vocabulary through input that is slightly beyond their current level of language comprehension (“i +1”), guided by mentors or language speakers.

e) Affective filter hypothesis – Pressure, fear, and anxiety have a negative effect on language learning (lowered self-confidence, motivation, worry).

The methodology requires that teachers use only the target language, or L2, in the classroom, without references to or support from L1. The goal is to create an atmosphere of immersion, in an effort to simulate language learning in the home environment. No grammatical instruction is provided in the Natural Approach. Students model and repeat language until grammatical patterns are absorbed over time.

As students grow in their ability to communicate using oral language, they are introduced to reading and writing in L2.

The Natural Approach is dependent on comprehensible input , a term introduced by Krashen as part of the Input Hypothesis and symbolized as ‘ i + 1’ (information that is known by the learner ‘i’, plus a new piece of information, or ‘1’). Comprehensible input is comparable to scaffolding as described by Vygotsky (1978). In Krashen’s view, language acquisition takes place when known language is blended with small amounts of new language . A language speaker (such as a teacher, guide, or mentor) helps the language learner to add the new language to their existing ‘language storehouse’ in the brain. Vygotsky used the phrase More Knowledgeable Other, or MKO, to describe the person providing guidance.

Krashen further asserted that high levels of comprehensible input build receptive language , which is the language received and stored by the brain through listening & reading . This storehouse of vocabulary is the foundation for productive language , which is the language needed for speaking & writing.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

In 1983, Krashen and Terrell identified four stages of language learning: pre-production (listening, gestures); early production (short phrases); speech emergence (sentences); intermediate fluency (conversation). These stages have influenced approaches to language teaching across North American for several decades.

- The distinction between acquisition and learning is not firmly supported by research. Terms such as acquiring, learning, and studying language are used interchangeably.

- Assumptions about a natural cognitive order for acquiring grammar are not supported in research. There is little evidence that an immersive approach in the classroom results in learners acquiring grammar naturally and in a logical order.

- The natural immersive environment of the home, where a first language surround infants and young children in the context of daily living, cannot be replicated in an artificial classroom environment.

- The hypothesis builds on a faulty assumption that a new language has no connection to knowledge already available in a first language. This premise discounts conceptual knowledge and literacy skills gained in a student’s first language and stored in the brain.

(3) Audio-Lingual Method

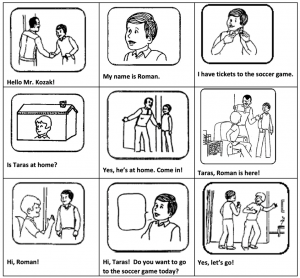

This method aligns well with Krashen’s hypothesis about the need for comprehensible input in language learning. The audio-lingual method promotes the notion that learning language can be simulated inside the classroom by using prescribed dialogues and texts which are comprehensible to the learners. When students are able to repeat dialogues easily, they are asked to transfer (‘transpose’) the memorized language to other situations they may encounter outside the classroom.

The audio-lingual method promotes accuracy over fluency, meaning that vocabulary is limited, but grammatically accurate. The method relies on memorization of set phrases for prescribed contexts or situations. Vocabulary-building does not extend beyond the prescribed dialogues and texts.

As with the Natural Approach, the Audio-Lingual Method proposes that students hear and use only the target language in the classroom, with no disruptions from their L1. Students are presented with a series of prepared drills and conversational sequences. They rehearse the sequences in pairs or small groups (e.g., role play, dialogues, class skits) until sentence patterns and grammatical sequences are memorized. In the initial stages, language is presented orally using audio-visual supports (e.g., audio recordings, film/video clips, pictures, props, gestures). Written language is introduced when basic oral skills have been mastered from the prepared dialogues and texts.

- Language forms are practiced in static drills without explicit instruction to highlight grammatical features of the new language.

- The method limits language learning to well-rehearsed sequences rather than allowing for expanded language learning beyond these sequences.

- Memorized language sequences learned in the classroom are often inadequate for real-life purposes or difficult to transfer to authentic situations encountered outside the classroom.

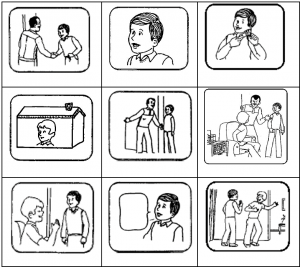

Memorize the text that matches each illustration, then role play with classmates using only the visuals. Three participants are required for the role play: Mr. Kozak, Roman, Taras.

Audio Visual Dialogue – Example for Role-Play (with text)

Source: Ukrainian Canadian Congress (1981). Mova I Rozmova (Language and Conversation). Winnipeg. https://www.spiritsd.ca/ukrainian/eng_high_mova.htm Permission: Courtesy of the Government of Saskatchewan Non-Commercial Reproduction.

Audio Visual Dialogue – Example for Role-Play (text removed)

(4) Total Physical Response

Total Physical Response, or TPR, was created by Dr. James Asher (1965). As with the theories of Terrell and Krashen, Asher believed that children learn a new language the way they learn their mother tongue. Children interact with their parents and the environment, combining actions and words for meaningful learning experiences. For example, a parent may say, “Look at me. Give me the toy.” The child will respond physically by looking and then handing the toy to the parent. These listening-responding actions continue for months until the child begins to mimic language by repeating one or two words, followed by phrases, and eventually full sentences.

TPR can be compared to games such as ‘Simon Says’ or ‘Follow the Leader’, in which participants listen for instructions and then perform the actions.

The teacher demonstrates a command-action sequence. Students are asked to listen to the command and perform the action several times. Then, together with the teacher, students repeat both the command and the action. After several choral repetitions, the teacher pulls away support (scaffolding) to allow student-led commands and actions.

TPR works particularly well with young children using learning activities such as fingerplays, action stories, and action songs. The combination of language and movement makes learning enjoyable. An extension of TPR with older learners is commonly called ‘role play’. For example, students can act out a cooking lesson, play charades, or participate in a ‘Who Am I’ game. TPR works with large or small classes and requires few props or materials. Teachers need to plan language-movement sequences carefully for best results.

- Younger children are often very open to movement and actions in the classroom, while older learners may find action sequences uncomfortable or embarrassing (unless the sequences are part of demonstrations, such as cooking or science experiments).

- TPR is highly dependent on brief statements and the use of imperative form of verbs, limiting language learning to commands with action verbs.

- Vocabulary grows at a slow pace, confined to directive statements and commands. Varied sentence patterns, questioning strategies, descriptive language, and interaction sequences for real-world communication are not part of TPR.

Follow the TPR sequence below.

Step 1: Students perform the actions following the teacher’s example.

Step 2: Students combine the action and statements as a choral exercise led by the teacher.

Step 3: Students repeat the actions and phrases in pairs or small groups on their own.

Permission: Courtesy of Nadia Prokopchuk, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Saskatchewan

(5) the communicative approach.

This approach grew in popularity in the late 1970s. It blended Krashen’s theory of natural language acquisition with the realization that students learn language more effectively in the classroom when communication is meaningful, purposeful, and applicable to their lives. The Communicative Approach, also known as Communicative Language Teaching, or CLT, does not adhere to one prescribed methodology. Several methodologies have been integrated into CLT, including task-based learning, immersion/partial immersion education, and integrated language and content instruction (ILCI). Other terms for ILCI are content-based instruction (CBI) and content and language integrated learning (CLIL).

Three distinguishing features of the Communicative Approach are:

- learner-centered instruction;

- language learning for real-life purposes; and,

- emphasis on fluency over accuracy.

In this approach, the teacher is the guide or facilitator of language learning in the classroom and students are active participants. Students gain confidence in their ability to communicate freely on various topics without feeling pressure to be grammatically accurate. Although grammar is not the central focus of the approach, it is still an important component of classroom instruction. Teachers draw attention to forms and functions of the language in the context of classroom language learning activities. Three methodologies that grew from the Communicative Approach are described below.

Task-Based Learning : This methodology centers on a problem to be solved or a task to be completed using the target language. Students begin with pedagogical tasks that are completed within the classroom, followed by target tasks to be completed outside the classroom. The tasks completed in the classroom allow the students to gain the language skills required to work on tasks outside the classroom, creating a ‘language bridge’ between the classroom and the real world. Tasks are carefully selected and sequenced to build functional language.

Full Immersion/Partial Immersion: Immersion education, in general, reflects the basic principles of communicative language teaching within the context of mainstream K-12 education. Immersion education has several delivery formats, such as partial, early, middle, and late immersion, bilingual education, and dual language education. Lyster and Genesee (2012) describe immersion education as “…a form of bilingual education that provides students with a sheltered classroom environment in which they receive at least half of their subject-matter instruction through the medium of a language that they are learning as a second, foreign, heritage, or indigenous language (L2). In addition, immersion students receive some instruction through the medium of a shared primary language, which normally has majority status in the community. (p.1) The curriculum for immersion education is cumulative in nature, with new language sequenced grade-by-grade into each subject area taught in the target language.

Integrated Language and Content Learning (ILCI) . As with immersion, ILCI methodology reflects the belief that language is best learned through active use in authentic contexts. In the case of K-12 education, the context is the school classroom. Students learn to communication in the new language while also learning content in the subject areas. In other words, the classroom is used for learning language and learning content through language . The methodology promotes a combination of language objectives and content area objectives. Teachers create language objectives that target key terms and phrases needed to learn content successfully. The focus on language and content allows students to reach curriculum objectives in the subject areas.

- As with the Natural Approach, the primary goal of Communicative Language Teaching is fluency rather than accuracy. Attention to grammatical features is left to the discretion of the teacher.

- Programs that are built on topics that reflect student interests may result in weak or unbalanced communication skills.

- Teachers continue to have difficulty recreating real-life communication in the artificial environment of the classroom.

- Assessment of progress can be challenging, given the focus on fluency for authentic purposes. Markers of language success must be clearly defined at the outset.

To encourage communication in the target language, create a Word Wall using a strategy called Brainstorming . Ask students to generate words and phrases based on a picture prompt that is relevant to a topic/theme being studied in class.

Step 1: Students share words and phrases that come to mind when looking at the selected picture. The teacher writes everything down on a whiteboard, poster, or flip chart.

Step 2: Ask students to organize the words/phrases into categories. Create lists that can be displayed in the classroom (shown below). Students can refer to the Word Wall when talking, singing, dramatizing, or writing on the topic.

Step 3: Students may transfer vocabulary from the Word Wall to a personal language notebook. Remind students that they may use their L1 as a tool to help them understand and remember the meaning of new vocabulary.

Picture Prompt: Autumn

Source : Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Michael Morse

Students might contribute some/all of the words below. These words can be categorized (e.g., colours, nature, clothing, action words) and used to create a Word Wall.

leaf, leaves, children, boy, girl, fall, fun, many, cool, jacket, sweater, trees, red, yellow, brown, gold, crimson, copper, play, throw, catch, run, jump, laugh, chilly, rustle, falling, autumn, forest, crunch, crackle, crisp, jumping, throwing, catching, rustling, colourful, happy, smiling, playing, laughing, sunshine, chilly, playtime, recess.

Use any format to create the Word Wall. Brief video explanations are available here:

- Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE). The Balanced Literacy Diet. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Q_Ek_ZD7hY

- Hampton, L. (2019). Learning Focused. Ideas for Creating Word Walls. https://learningfocused.com/word-wall-ideas-interactive-classroom-word-wall-makeover/

Review Your Learning

- Describe five language teaching methodologies/approaches that have been used in past decades to promote language study.

- Identify key features and weaknesses of each methodology/approach.

- Recall personal language learning experiences from past years. Which approach or methodology was commonly used by your language teacher(s)?

- Think about your current teaching practices. Which approach or methodology do you frequently use for language instruction? Why?

Module 1 Glossary

Approach: A broad term used to describe a set of beliefs or assumptions about the nature of language learning.

Comprehensible input: A strategy for language learning that involves the use of language that is slightly above the level of language that is understood by learners. Krashen described this small margin between the known and the new as i +1.

Interpretation: Involves oral transfer of information from one language to another, ensuring that the intended meaning is conveyed to the listener.

Method (methodology): Describes a systematic plan for language teaching that reflects a selected approach.

Productive language: The language produced (output) through speaking and writing.

Receptive language: The language received and stored in the brain (input) through listening and reading.

Scaffolding: Process of adding small bits of new information (input) to existing knowledge, guided by an individual who is a ‘More Knowledgeable Other’ (Vygotsky = MKO).

Strategies: Actions, tasks, or activities that support language instruction in the classroom as part of a teaching methodology.

Translation: Involves written transfer of information from one language to another.

Brown, H. D. & Lee, H. (2015). Teaching by Principles. An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy . Fourth Edition . New York: Pearson Education Inc.

Krashen, S.D. & Terrell, T.D. (1983). The natural approach: Language acquisition in the classroom . London: Prentice Hall Europe.

Lyster, R. & Genesee, F. (2012). Immersion Education. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics . Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315714959_Immersion_Education

McLeod, S. A. (2012). Zone of proximal development. Retrieved from: www.simplypsychology.org/Zone-of-Proximal-Development.html

Richards, J. & Rogers, T. (2014). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Romeo, K. (n/d). Krashen and Terrell’s “Natural Approach”. Retrieved from: https://web.stanford.edu/~hakuta/www/LAU/ICLangLit/NaturalApproach.htm

Terrell, T.D. (1977). A natural approach to the acquisition and learning of a language. Modern Language Journal, 61 . 325-336.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Watson, Sue. (2020). How to Brainstorm in the Classroom. ThoughtCo. Retrieved from: thoughtco.com/brainstorm-in-the-classroom-3111340

Language Learning in K-12 Schools: Theories, Methodologies, and Best Practices Copyright © 2022 by Nadia Prokopchuk is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Teaching Methodologies

Learning Objectives

- I can understand and explain the differences between grammar-translation, audiolingual, and communicativist teaching methods

- I can explain the possible positives and negatives of these three teaching methods

Similarly to the first section of this chapter, this section will focus on classroom methodology . This time, however, it’s more specific to actual language education and not just learning theories in general. I want you to think back to that high school language class. Put yourself in the room, see your teacher, and your classmates too. Now that we know about Behaviorism, Cognitivism, and Constructivism, I want you to put a label on the type of learning you experienced in that class. It might be difficult, and it’s fine to say that it was mixed, because it most likely was. Most education is a blend of many rich elements because there is no one way to teach a language.

Some language teaching methodologies existed before people were theorizing about learning, and others have been influenced by learning theories over time. Think back to your high school classroom again. Your teacher might have asked you to mostly do grammar exercises in a workbook. They might have held up plastic fruits or pointed to colors and prompted you to say the translated words back. You might have followed scripts and talked with your classmates, maybe like “Hola, quiero comprar cien bananas por favor” (Hi, I would like to buy a hundred bananas please), admittedly the applicability of this situation is not high. Or you might have been asked to jump in and interact with your classmates mostly through immersion in the new language until you could communicate, similar to learning your first language.

Grammar-translation approach

One very traditional way of language teaching that was not influenced by any modern learning theory is called ‘grammar-translation’. In Grammar-translation, “The aim is for students to be able to translate with ease between two languages, usually their first or native language (L1) and the target language (L2) being learned” (Prokopchuk, 2022). As stated, this looks primarily like the study of individual grammatical structures, conjugations, or vocabulary for a language, and less of the conversational aspects or application of language. While this method has largely died out in popularity among language teachers, it still might be found in some classrooms, specifically classic-language classrooms like Latin or ancient Greek. Even if you didn’t take one of those classes, however, your language classroom likely implemented elements of grammar-translation. Grammar-translation methods can be extremely helpful in the explicit teaching of grammar concepts, sentence structure, or vocabulary. They rely on our abilities to see and reproduce patterns, which relates to both behaviorist and cognitivist ways of learning. However, many people agree that the grammar-translation method falters is its lack of immediate applicability to real-life scenarios and the over-focus on declarative knowledge. That is, conversations on the street likely won’t consist of ‘Hey, how do you conjugate the verb ser in the pluscuamperfecto?’ (the verb to be in the past perfect tense). So, while the grammar-translation method does have many positive elements in the explicit teaching of linguistic concepts, other teaching methods focus more on real-life application and communication.

Audiolingual approach

A very different approach to language teaching that was strongly influenced by behaviorism is the Audiolingual method. Popularized in the 1950s, the Audiolingual method focuses on “the notion that learning language can be simulated inside the classroom by using prescribed dialogues and texts which are comprehensible to the learners” (Prokopchuk, 2022). Some common practice exercises used machines in language learning labs, rather than using practice with other people. These machines would allow you to listen to a sentence as spoken by a native speaker, and then record yourself speaking the same sentence. You would then listen to both and do a side-by-side comparison of your accents . The focus largely was on scripted learning and the perfection of predetermined vocabulary and a ‘native-like’ accent. Akin to behaviorism, learning takes place through habitual repetition and praise for correct answers. Unlike grammar translation, this method does provide intensive listening and speaking practice to build procedural ability, but learners still don’t have the opportunity to improvise in real-life interactions. The constant focus on accuracy can make also learners self-conscious and afraid to experiment with communication. And while the focus on accent can help with some people’s goals, let’s think back to chapter one and think about the role of accent in communication. Maybe an aside thought in a box by the main chapter?

Communicative approach

Lastly, communicative approaches are the most popular among language teachers today, largely because of their focus on usability rather than perfection. Communicative approaches acknowledge that “students learn language more effectively in the classroom when communication is meaningful, purposeful, and applicable to their lives” (italics in original) (Prokopchuk, 2022). Classrooms that include communicative approaches are most like my own growing up.

Logan ~ I grew up in a dual language immersion program where I started learning Spanish as a kindergartener. Without any prior knowledge of the language, I was thrown into a setting where Spanish was the only language spoken by teachers, and English among students was discouraged. Over time and with many visual aids, the words started to pick up meaning and I was able to create original ideas like “puedo tener el juguete por favor” (can I please have the toy)

The focus on communication helps with fluency in a language, but sometimes sacrifices grammatical accuracy if there is no parallel focus on declarative knowledge, especially with older learners. We see that communicative approaches draw on both cognitivist and constructivist approaches, but they can also include aspects of behaviorist approaches. The key difference from other teaching methods is that communicative approaches are not limited to behaviorist or cognitivist approaches.

Thought exercise

Would you rather…

- Lose your grammatical knowledge

- Lose your vocabulary

Which impacts your ability to communicate more?

With your understanding of these teaching approaches, let’s now see if we can recognize these styles when presented with an example. These examples may look like exercises that subscribe to one method more than another, or maybe examples of things that might be said in these classrooms.

Before we move on, if you would like more information about teaching methods (and to learn about different teaching methods than these three), please watch this video.

While any one person might have their preferred teaching method or learning theory as we talked about in the last section, I hope that it is apparent that these theories and methods are not one-size-fits-all, nor should they exist independently of one another. Where the audio-lingual or grammar-translation methods falter, the communicative method can supplement, and vice-versa. The same can be said for all the theories and methods we talked about in this chapter. Diversity is best when learning a language; diversity in people, diversity in exercises and methods, and diversity in input. We all grew up learning our native language through a variety of different methods of exposure whether that be our parents talking to us, reading the labels at the store, or watching TV, and eventually studying grammar in school. So, I beg the question: why should we treat our second language any differently?

A group or set of methods used for the purpose of creating an effective learning environment in the classroom.

A patterned variation of pronunciation in a language. Usually tied to a specific region, community, or individual.

The ability to speak in a language spontaneously without unnecessary pauses, even if some errors might occur.

How correct one's language use is according to the specific language ideology held by interlocutors.

Language Learning Copyright © by Keli Yerian and Bibi Halima. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Professional development

- Knowing the subject

- Teaching Knowledge database D-H

Methodology

Methodology is a system of practices and procedures that a teacher uses to teach.

It will be based on beliefs about the nature of language, and how it is learnt (known as 'Approach').

Example Grammar Translation, the Audiolingual Method and the Direct Method are clear methodologies, with associated practices and procedures, and are each based on different interpretations of the nature of language and language learning.

In the classroom Many teachers base their lessons on a mixture of methods and approaches to meet the different needs of learners and the different aims of lessons or courses. Factors in deciding how to teach include the age and experience of learners, lesson and course objectives, expectations and resources.

Further links:

https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/scott-thornbury-british-council-armenia

https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/methods-post-method-m%C3%A9todos

https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/starter-teachers-a-methodology-course-classroom

Research and insight

Browse fascinating case studies, research papers, publications and books by researchers and ELT experts from around the world.

See our publications, research and insight

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Language teaching methodology : a textbook for teachers

Available online, at the library.

SAL3 (off-campus storage)

More options.

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary.

- Part 1 An empirical approach to language teaching methodology: defining "methodology"

- research into language processing and production

- the context and environment of learning

- classrooms in action

- exploring language classrooms

- how to use this book. Part 2 Listening: bottom-up and top-down views of listening

- identifying different types of listening

- textual connectivity

- listening purpose

- what makes listening difficult?

- listening texts and tasks

- investigating listening comprehension. Part 3 Speaking in a second language: identifying different types of speaking

- predictability and unpredictability

- the concept of "genre"

- the difficulty of speaking tasks

- classroom interaction

- stimulating oral interaction in the classroom

- investigating speaking and oral interaction. Part 4 Reading - discourse perspective: bottom-up and top-down views on reading

- scheme theory and reading

- research into reading in a second language

- reading and social context

- types of reading text

- the reading lesson

- investigating reading comprehension. Part 5 Developing writing skills: differences between spoken and written language

- writing as process and writing as product

- the generic structure of texts

- differences between skilled and unskilled writers

- writing classrooms and materials

- investigating writing development. Part 6 Mastering the sounds of the language: a contrastive approach to pronunciation

- recent theory and research

- pronunciation in practice

- investigating pronunciation. Part 7 Vocabulary: the status of vacabulary in the curriculum

- word lists and frequency counts

- vocabulary and context

- vocabulary development and second language acquisition

- semantic networks and features

- memory and vocabulary development

- investigating the teaching and learning of vocabulary. Part 8 Focus on form - the role of grammar: the "traditional" language classroom

- second language acquisition research and its influence on practice

- grammatical consciousness-raising

- pedagogic materials and techniques for teaching grammar

- investigating the teaching and learning of grammar. Part 9 Focus on the learner - learning styles and strategies: research into learning styles and strategies

- the "good" language learner

- a learner-centred approach to language teaching

- learning strategies in the classroom

- investigating learning strategy preferences. Part 10 Focus on the teacher - classroom management and interaction: amount and type of teacher talk

- teacher questions

- feedback on learner performance

- classroom management in action

- investigating teacher talk. Part 11 Materials development

- commercial materials

- research on materials in use

- materials and methods

- materials design

- materials adaptation

- investigating materials. Part 12 Language teaching methods - a critical analysis: the psychological tradition

- the humanistic tradition

- the second language acquisition tradition

- investigating methods.

- (source: Nielsen Book Data)

Bibliographic information

Browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Your cart is empty

Have an account?

Log in to check out faster.

Estimated total

Enjoy £5.00 off your order! Use Code: WELCOME5

No physical shipments, just instant downloads!

English Language Teaching: Approaches, Methods, and Techniques

Written by: Mike Turner

June 15, 2021

Time to read 5 min

When we are looking at the effectiveness of our teaching, we often get tied up in the minutiae of classroom practice. However, sometimes it’s useful to take a bit of a step back and examine what we are doing more broadly.

In order to look at our different options as teachers, it is handy to use a consistent framework. I am indebted to several writers on TEFL methodology, but I have chosen specifically to apply the useful distinctions between approach , method , and technique made by Richards and Rogers in their 1986 work Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching (London: CUP). Although the book is now 25 years old, it still provides one of the neatest and most accessible descriptions of some of the most influential approaches. The terminological distinctions they draw are particularly useful and are summarised below. I have then applied them, as succinctly as I can, to a variety of current and historical approaches. The list is not intended to be exhaustive, but I hope it will allow teachers to contextualise their own practice.

Approach, Method & Technique

An approach describes the theory or philosophy underlying how a language should be taught; a method or methodology describes, in general terms, a way of implementing the approach (syllabus, progression, kinds of materials); techniques describe specific practical classroom tasks and activities. For example:

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) is an approach with a theoretical underpinning that a language is for communication.

A CLT methodology may be based on a notional-functional syllabus, or a structural one, but the learner will be placed at the centre, with the main aim being developing their Communicative Competence. Classroom activities will be chosen that will engage learners in communicating with each other.

CLT techniques might include role-plays, discussions, text ordering, speaking games, and problem-solving activities.

Some Different Approaches, Methods & Techniques

The audiolingual approach.

The Audiolingual Approach is based on a structuralist view of language and draws on the psychology of behaviourism as the basis of its learning theory, employing stimulus and response.

Audio-lingual teaching uses a fairly mechanistic method that exposes learners to increasingly complex language grammatical structures by getting them to listen to the language and respond. It often involves memorising dialogues and there is no explicit teaching of grammar.

Techniques include listening and repeating, and oral drilling to achieve a high level of accuracy of language forms and patterns. At a later stage, teachers may use communicative activities.

CLIL - Content and Language Integrated Learning

CLIL is an approach that combines the learning of a specific subject matter with learning the target language. It becomes necessary for learners to engage with the language in order to fulfil the learning objectives. On a philosophical level, its proponents argue that it fosters intercultural understanding, meaningful language use, and the development of transferrable skills for use in the real world.

The method employs immersion in the target language, with the content and activities dictated by the subject being taught. Activities tend to integrate all four skills, with a mixture of task types that appeal to different learning styles.

Techniques involve reading subject-specific texts, listening to subject-based audio or audio-visual resources, discussions, and subject-related tasks.