- Prehistoric

- From History

- Cultural Icons

- Women In history

- Freedom fighters

- Quirky History

- Geology and Natural History

- Religious Places

- Heritage Sites

- Archaeological Sites

- Handcrafted For You

- Food History

- Arts of India

- Weaves of India

- Folklore and Mythology

- State of our Monuments

- Conservation

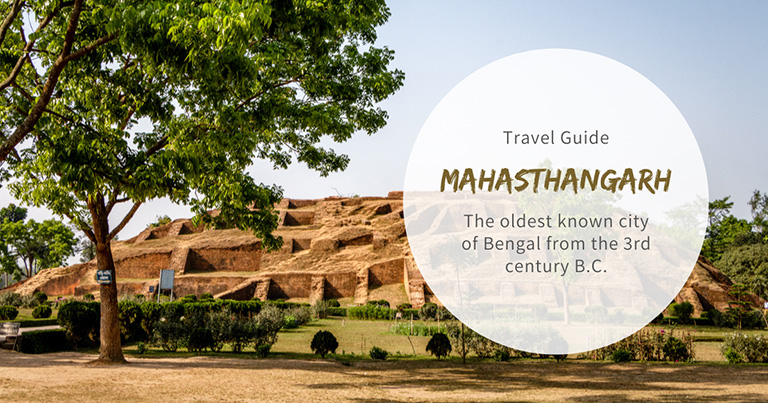

Mahasthangarh: Bangladesh's Oldest City

- AUTHOR Aditi Shah

- PUBLISHED 16 November 2021

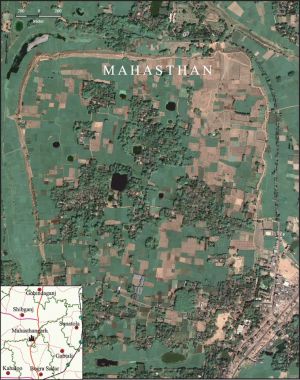

One of the subcontinent’s oldest cities in the east is still telling its story 2,300 years after the Mauryans built this magnificent provincial capital in what is now north-west Bangladesh. Identified as the glorious city of Pundranagara, it is known as Mahasthangarh today and is situated in what was earlier East Bengal.

Mahasthangarh is Bangladesh’s oldest-known city, an archaeological site 200 km north of Dhaka on the banks of the Karatoya River. The site goes back to the 3rd century BCE, to the height of the Mauryan Empire, whose capital was Pataliputra in present-day Patna, the capital of Bihar in Northern India. And what a sight it must have been!

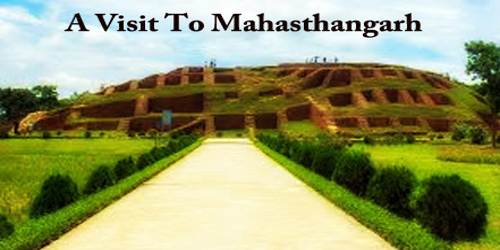

Long and snaking walls made of burnished brick still outline the city’s fortified heart, a citadel that measures 1.5 km x 1.4 km. Inside the citadel and all around, excavations are still uncovering structures that reveal what was undoubtedly a vibrant administrative and cultural capital.

Archaeological remains and medieval literary descriptions point to a well-planned and highly organised city that had sturdy walls, elaborate gates, opulent palaces, large assembly halls, places of worship, lush orchards, pleasure gardens and vast suburban areas where common folk lived.

– This ancient city was first discovered, not by an archaeologist, but by Scottish geographer and botanist Francis Buchanan-Hamilton in 1807.

Employed by the British East India Company, he was asked by the Government of Bengal to survey the area and report on its topography, history and inhabitants. During one of his field visits, he came upon the abandoned site of Mahasthangarh and made a note of it.

But Pundranagara was not ready to be discovered, at least not yet. It would be 70 years before Alexander Cunningham, the father of Indian archaeology, visited the site, in 1879. And it was he who identified it as the ancient city of Pundranagara, mentioned in classical literary texts.

The Aitareya Brahmana , a Vedic text, talks of the Pundra people living in the eastern part of the subcontinent. That’s how the city probably got its name. The Chinese monk Hiuen Tsang, who visited the area in the 7th century CE, wrote that Pundranagara had 20 Buddhist monasteries, over 3,000 Buddhist monks, 100 Dev temples and followers of multiple sects, including Jain Digambar monks.

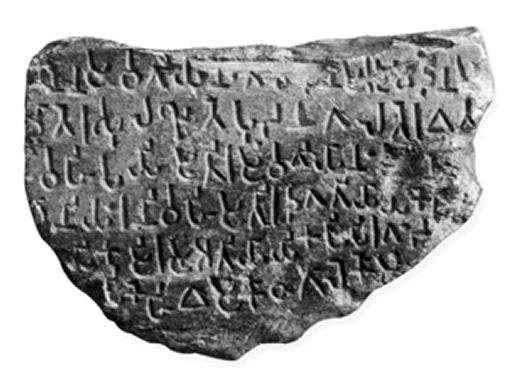

Evidence that helped identify this as the city Pundranagara came from a chance find by a local farmer, who happened to dig up a limestone slab in his fields. The six-line inscription in the Brahmi script recorded a land grant and was dated to the 3rd century BCE, the era of the Mauryan Dynasty.

The inscription tells us that ‘a mahamatra was posted in the well-organised and prosperous Pundranagara. He gave orders to dole out sesame and mustard seeds to the samvargikas ... The crops were stored in the royal granary in the fortified area of the city.’

The famous 11th-century text Kathasaritasagar by Somadeva, a collection of folktales, mentions a road from Pundranagara to Pataliputra, the Mauryan capital. It seems Pundranagara was an important trading city in ancient times and was well connected to other parts of Bengal, by road and by river. The Arthashastra of Kautilya refers to ‘Paundrika patrorna ’, a type of silk, and dukula , a fine-quality cotton cloth, both produced in Pundra.

The site of Mahasthangarh, which includes the citadel at its centre, covers an area with a radius of 9 km, and includes hundreds of mounds, some excavated, others yet to be, scattered across several villages. Excavations, which began in the 1920s, have revealed cast copper coins belonging to the 3rd century BCE, which support the antiquity of the city.

Amazingly, the site shows continuous occupation from the 3rd century BCE to the 13th century CE, which is reflected in remains that date from pre-Mauryan times to the Mauryans, Kushanas, Guptas and the Palas.

The remains found here include the ruins of Buddhist monasteries, Hindu temples and numerous Hindu and Buddhist sculptures.

Excavations have also uncovered a trench and a tunnel built through the massive fort wall, a sign of a military siege. While this military practice is well-known through textual sources, most notably the Arthashashtra , the Mahasthangarh tunnel is the earliest archaeological evidence of this military strategy in the Indian subcontinent.

Weapons like arrows, spears, crossbow heads and terracotta slingshot balls, dated to the 7th-8th century CE, have been found in large numbers. After the siege, important construction activities were undertaken that can be placed in the Pala period, a long period of peace in North Bengal.

This spectacular city appears to have fallen to ruin when a massive earthquake hit the area in 1255 CE. Besides the obvious damage, the earthquake probably caused the Karatoya River to silt up, forcing the residents to migrate.

Excavations are still being carried out here but Mahasthangarh has faded from public memory. Sadly, lack of adequate conservation, poor water drainage and looting are damaging this vital archaeological site. This was stated in a 2010 a report titled Saving Our Vanishing Heritage prepared by the Global Heritage Fund, which identified Mahasthangarh as one of 12 worldwide sites most ‘on the verge’ of irreparable loss and damage. What will it take to save Bangladesh’s oldest city and a vital part of India’s heritage?

Cover Image: The Gokul Medh mound, 3 km south of the citadel, courtesy Azim Khan Ronnie

Handcrafted Home Decor For You

Blue Sparkle Handmade Mud Art Wall Hanging

Handcrafted Tissue Box Cover Sea Green & Indigo Blue (Set of 2)

Scarlet Finely Embroidered Silk Cushion Cover

Sunflower Handmade Mud Art Wall Hanging

Best of Peepul Tree Stories

Mahasthangarh

Dating back to at least the 4th century BCE, Mahasthangarh is the earliest urban archaeological site that has been discovered in Bangladesh.

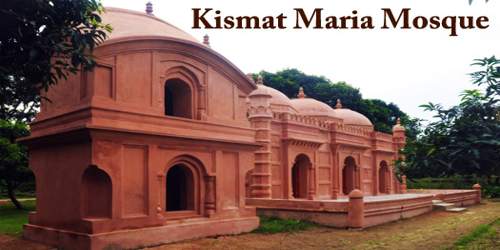

Several historical sites are located within the rampart wall, including a mausoleum (Mausoleum of Shah Sultan Mahisawar Balkhi), a temple site (Bairgir Bhita), remnants of an ancient palace (Parshuram’s Palace) with an ancient well (Jiyat Kunda) as well as residential blocks in the eastern rampart area.

One of the highlights of Mahasthangarh is Govinda Bhita, where remnants of two Buddhist temples can be visited. The main temple was erected in the 6th century and next to it is a slightly smaller temple, which was built in the 11th century.

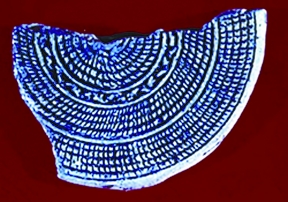

Opposite Govinda Bhita, near the north side of the citadel is the Mahasthan Archaeological Museum. The museum is quite small but has a well-maintained collection of pieces recovered from the archaeological site. These include the statues of Hindu and Buddhist gods and goddesses, terracotta plaques depicting daily life, as well as some well-preserved bronze images found in nearby monastery ruins that date back to the pre-Pala period. There are even some fragments of ring-stones which were used for rituals in the Mauryan period.

The rest of the archaeological site consists mainly of foundations and hillocks, hinting at the past glory. It's possible to walk over the remains of the fortifications of the ancient citadel to get a sense of how the city would once have looked.

Open from sunrise to sunset

Entry is free both for national and international visitors

- Mahasthangarh: Ruins of the oldest known city of Bengal from the 3rd century B.C.

Mahasthangarh is the oldest known city of Bengal located in Bangladesh, dating back to the 3rd century B.C. The word ‘Mahasthan’ means a place that has excellent sanctity, and ‘Garh’ means fort. The extensive ruins of Mahasthangarh present a glorious past of about two thousand and five hundred years of Pundranagar, the capital city of ancient Pundra Vardhan Bhukti.

Mahasthangarh, spreading along the western bank of the Korotoa river, is situated about 13 km north of Bogra town. This earliest and largest city of the entire Bengal is fortified successively by mud and brick wall. It measures 1,525 meters long North-South, 1,370 meters broad East-West, and 5 meters high above the surrounding level. The river in the east and a deep moat on the west, south, and north served as additional defense apart from the citadel wall.

History of Mahasthangarh

From the archaeological evidence, it is proven that Mahasthangarh was the provincial capital of the Mauryans, the Guptas, the Palas, and the Feudal Hindu kings of a later period. Beyond the citadel, other ancient ruins found within a radius of 7/8 km in a semi-circle in the north, south, and west testify to the existence of extensive suburbs.

It is worth quoting that Yuen Chwang, the famous Chinese pilgrim, visited the Pundra Vardhana between 639-645 A.D. Sir Alexandar Cunningham rightly identified the current Mahasthangarh as Pundranagar in 1879, following the description left by Yuen Chwang.

The whole area is rich in Hindu, Buddhist, and Muslim sites. The Buddhists were here until at least the 11th century. Their most glorious period was the 8th to the 11th centuries when the Buddhist Pala emperors of North Bengal ruled. It is from this period that most of the visible remains belong. The citadel was probably first constructed under the Mauryan empire in the 3rd century B.C.

Mahasthangarh fell into disuse around the time of the Mughal invasions. Most of the visible brickwork dates from the 8th century, apart from that added during restoration. Outside the citadel, there is a remaining of 6th-century Govinda Bhita Hindu Temple, which looks like a broken-down step pyramid.

- 17 Best places to visit in Bangladesh you can't miss on your holiday

- 13 Places to visit in Dhaka you can't miss on your trip

- 16 Top Bangladeshi food you must try on your visit

- 11 Major tribes (ethnic/indigenous groups) of Bangladesh and their culture

- 8 Top things to do in Sundarbans for a great experience of the forest

- 8 Top things to do in Sreemangal for the ultimate experience

- 10 Most impressive archaeological sites in Bangladesh you can't miss on your trip

- 10 Most beautiful historical mosques in Bangladesh

- Bangladesh Tourist Places: A full list of the best sights

- Lawachara National Park: A Guide to its diverse flora and fauna

- Puthia Temple Complex: A village full of historic Hindu temples in Bangladesh

- Kantajew Temple—The most beautiful terracotta temple in Bangladesh

- Gaur (Gauda / Gour): The rich ancient capital of Bengal located on the India-Bangladesh border

- Mosque City of Bagerhat: A Lost 15th-Century City and a UNESCO World Heritage Site

- Panam Nagar: An entirely abandoned city of the wealthy Hindu cotton merchants in Bangladesh

- Sonargaon Travel Guide: Visiting Museum and other attractions in the old capital

- Jaflong: A popular tourist site in Bangladesh with unique photo opportunities

- Tajhat Palace: The finest Jamidar Bari in northern Bangladesh

Have you ever visited Mahasthangarh? How amazing have you found it? Share your thoughts and experience with us in the comments.

Check out our 1-7 days Bangladesh tour packages and 8-28 days Bangladesh holiday packages to visit Bangladesh with comfort.

Sundarban Safari

Bangladesh Photography Tour

Classic Bangladesh

Glories of Bangladesh

Raas Festival Tour

Express Bangladesh

I am the Owner & CEO of Nijhoom Tours, a multi-award winning local tour operator in Bangladesh specializing in organizing memorable holidays in Bangladesh for western travelers. Connect with me on Facebook or Mastodon , or join our Facebook group Let's Go To Bangladesh for updates and help about traveling to Bangladesh.

View all posts

Awards & Recognitions

Connect with us

Affiliation

Featured On

Online Payment Details

How to pay us

Content Protection

Content of this website is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. of USA. Any content (text, photo, video, graphics) theft from this website and hosted somewhere else will be taken down by their ISP under the DMCA law, no matter which country the site is hosted in.

Mahasthan or Mahasthangarh represents the earliest and the largest archaeological site in Bangladesh, consists of the ruins of the ancient city of pundranagara . The site is 13 km north of Bogra town on the Dhaka-Dinajpur highway. The ruins form an oblong plateau measuring 1500m N-S and 1400m E-W and are enclosed on their four sides by rampart walls that rise to an average height of 6m from river level. The highest point within the enclosure at the southeast corner is occupied by the mazar (tomb) of shah sultan mahisawar and by a mosque of the Mughal Emperor farrukh siyar . The latter has been enclosed by a modern mosque, which has been extended recently, a development that precludes the scope of excavation here in future.

The northern, western and southern sides of the fortified city were encircled by a deep moat, traces of which are visible in the former two sides and partly in the latter side. The river Karatoya flows on the eastern side. The moat and the river might have served as a second line of defence of the fort city. Many isolated mounds occur at various places outside the city within a radius of 8 km on the north, south and west, testifying to the existence of suburbs of the ancient provincial capital.

Many travellers and scholars, notably buchanan , O'Donnell, Westmacott, beveridge and Sir Alexander cunningham visited this site and mentioned it in their reports. But it was Cuningham who identified these ruins as the ancient city of Pundranagara in 1879.

The city was probably founded by the Mauryas, as testified by a fragmentary stone inscription in the Brahmi script ( mahasthan brahmi inscription ) mentioning Pudanagala (Pundranagara). It was continuously inhabited for a long span of time.

The first regular excavation was conducted at the site in 1928-29 by the Archaeological Survey of India under the guidance of KN Diksit, and was confined to three mounds locally known as bairagir bhita , govinda bhita and a portion of the eastern rampart, together with the bastion known as munir ghun . Work was then suspended for three decades. It was resumed in the early sixties when the northern rampart area, parasuram palace (Parashuramer Prasad), mazar area, khodar pathar bhita , mankalir kunda mound and other places were excavated. The preliminary report of these excavations was published in 1975. After about two decades excavation was once more resumed in 1988.

It then continued for almost every year up to 1991. During this period the work was confined to areas near the mazar and the northern and eastern rampart walls. But the work done in this phase was of negligible scope compared to the vastness of the site. The history and cultural sequence of the site were yet to be established.

The necessity of a thorough investigation for the reconstruction of the early history of the site and the region, and for the understanding of the organisation of the ancient city continued to be felt. Consequently, under an agreement between the governments of Bangladesh and France (1992) a joint venture by Bangladeshi and French archaeologists was undertaken in early 1993. Since then archaeological investigation is being carried out every year in an area close to the middle of the eastern rampart. Excavations have also been conducted earlier by the Department of Archaeology, Bangladesh, in a number of sites outside the fortified city such as bhasu viharA (Bhasu Vihara), bihar dhap , mangalkot and Godaibari.

Excavation at the city has reached virgin soil at several points. Of these, the recent excavations conducted by the France-Bangladesh mission have revealed 18 building levels. The works carried out at different times from 1929 to the present (including France-Bangladesh expeditions) reveal the following cultural sequence:

Period I represents the pre-Mauryan cultural phase characterised by large quantity of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) of phase B, Rouletted ware, Black and Red Ware (BRW), black slipped ware, grey ware, stool querns, mud-built houses (kitchen) with mud floors, hearths and post-holes. Fine NBPW are more numerous in the lowermost levels; dishes, cups, beakers and bowls are the predominant types. Only a brick-paved floor has been traced in a very restricted area of this level, but no wall associated with this floor has been exposed till now. It appears that the earliest settlement took place over the Pliestocene formation. No precise date for this early settlement could be ascertained. But some radiocarbon dates from the upper level go back to late 4th century BC. This indicates that the 'early settlement' is of pre-Mauryan period. It needs to be ascertained whether this phase belongs to Nanda or pre/proto-historic culture.

Period II is represented by the occurrence of broken tiles (the earliest evidence so far known of this type of roofing), brick-bats used as temper or binding material in the construction of mud walls (also sometimes reused in a domestic context ie, fire place, terracotta ring well),

NBPW, common wares of pale red or buff colour, ring stone, bronze mirror, bronze lamp, copper cast coins, terracotta plaques, terracotta animal figurines, semi-precious stone beads, stone mullers and querns. A few calibrated radiocarbon dates (366-162 BC, 371-173 BC) and the cultural materials indicate that this phase represents the Mauryan period.

Period III represents the post-Mauryan (Shunga-Kusana) phase. It is marked by substantial architectural remains of large sized and better-preserved brick built houses, brick-paved floors, post-holes, terracotta ring wells, large quantity of terracotta plaques of Shunga affiliation, beads of semi-precious stones (agate, carnelion, quartz), silver punch marked coins, silver bangle, copper cast coins, antimony rods, terracotta pinnacle, large quantity of common pale red or buff wares (especially dishes, cups and bowls) and grey wares. NBPW of course fabric occurs in less frequency compared to Mauryan level. A few radiocarbon dates give calibrated intervals 197-46 BC, 60 BC-172 AD, 40 BC-122 AD.

Period IV represents the Kusana-Gupta phase. It is marked by the discovery of substantial amount of Kusana pottery and terracotta figurines with definite stylistic affiliation of the contemporary idiom. The principal pottery types are handled cooking vessels with incised designs, saucers, bowls, sprinklers and lids. Architectural remains are scanty compared to its lower and upper phases. Building materials are represented by small fragments of bricks. Other cultural materials are terracotta beads, bowls, stone and glass beads, glass bangles, terracotta seals and sealings. Gold coins

Period V represents the Gupta and late-Gupta phase. Radiocarbon data of this phase give calibrated dates between 361 AD and 594 AD. The phase yielded remains of a massive brick structure of a temple called Govinda Bhita, located close to the fort-city, belonging to the late Gupta period, as well as other brick structures - houses, floors, streets - in the city, and huge antiquities, including terracotta plaques of the characteristic style, seals, sealings, beads of terracotta, glass and semi-precious stones, terracotta balls, discs, copper and iron objects, and stamped wares.

Period VI represents the Pala phase, evidenced by architectural remains of several sites scattered throughout the eastern side of the city, like Khodar Pathar Bhita, Mankalir Kunda, Parasuram's Palace and Bairagir Bhita. This was the most flourishing phase and during this period a large number of Buddhist establishments were erected outside the city.

Period VII represents the Muslim phase testified by the architectural remains of a 15 domed mosque superimposed over the earlier period remains at Mankalir Kunda, a single domed mosque built by Farrukh Siyar, and other antiquities like Chinese celadon and glazed ware typical of the age.

Bairagir Bhita, Khodar Pathar Bhita, Mankalir Kunda Mound, Parasuram’s Palace Mound and Jiat Kunda are some sites inside the city which have yielded archaeological objects of interest. In addition to these sites, excavations in 1988-91 have revealed three gateways of the city, a considerable portion of the northern and eastern rampart, and a temple complex near the mazar area. Out of the three gateways, two are in the northern rampart; one is 5m wide and 5.8m long and is located 442m eastward from the northwest corner of the fort, and the other, situated 6.5m eastward, is 1.6m wide. The gateways were in use in two phases related to the early and later Pala periods. The only gateway in the eastern rampart, located almost in its middle and 100m east of Parasuram’s Palace, is about 5m wide and is thought to have been built in the late Pala period over the remains of an earlier gateway, which has not yet been fully exposed.

All the gateway complexes are provided with guardrooms in the inner side, and bastions projecting outside the rampart walls. The temple complex exposed in the mazar area does not reveal a coherent plan. It appears to have been built and rebuilt in five phases, one superimposed over the other, covering the Pala period. The antiquities recovered from the site include a few large size terracotta plaques, toys, balls, ornamental bricks, and earthenwares.

The rampart of the city, built with burnt bricks, belongs to six building periods. The earliest one belonged to the Maurya period, whereas the subsequent ones correspond to Shunga-Kusana, Gupta, early Pala, late Pala, and Sultanate periods. These walls were successively built one above the other.

Thus we get a succession of rampart walls as we see the succession of cultural remains inside the city. However, the correlation between the cultural remains of the city of the earliest level and the earliest rampart wall (mud wall?) remains to be established.

Govinda Bhita, laksindarer medh , Bhasu Vihar, Vihar Dhap, Mangalkot and Godaibadi Dhap are excavated sites located outside the city but within its vicinity. Many more mounds lie scattered in adjacent villages, which are believed to contain cultural remains of the suburbs of the ancient fortified city of Pundranagar. [Shafiqul Alam]

Bibliography KN Dikshit, 'Annual Report 1928-29', Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi, 1933; A Cunningham, 'Report of a Tour in Bihar and Bengal in 1879-1880 From Patna to Sonargaon', Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi 1969; N Ahmed, Mahasthan: A Preliminary Report of The Recent Archaeological Excavations at Mahasthangarh, Dacca, 1975; Shafiqul Alam and J-F Salle (ed), France-Bangladesh Joint Venture Excavations at Mahasthangarh First Interim Report 1993-1999, Dhaka, 2001.

- Archaeology

- This page was last edited on 17 June 2021, at 19:21.

- Privacy policy

- About Banglapedia

- Disclaimers

World 🢖 Asia 🢖 Bangladesh

Ancient cities and towns 🢔 Settlements 🢔 Archaeological wonders 🢔 Categories of wonders

Mahasthangarh

T rue wonder of the ancient past of Bangladesh is Mahasthangarh . This enormous city was founded at 300 BC or even earlier and served as a capital of Pundravardhana state.

GPS coordinates

Location, address, name in bengali, alternate names, map of the site.

Mahasthangarh is located next to Karatoya River, in a comparatively high location, some 25 m above sea level. Currently, this is a small, silted river but in the earlier times, Karatoya was an important and sacred river, which then seemed to be as large as the sea: reportedly three times wider than Ganges in the 13th century AD. This river served as a border between Pundravardhana and Kamarupa – another ancient country to the east.

This high bank at the giant river was one of the main reasons why this location was selected for the city. And the most likely loss of the might of this river can be blamed for the decline of the city. Such changes in the flow of rivers are frequent in Bangladesh and are caused by silting and earthquakes.

Rivers were the main transport routes but Mahasthangarh was connected to important regional centers (e.g. Pataliputra, Mithila) with roads as well.

Description

Remnants of this ancient city are well visible up to this day albeit not too exciting: for most part there are visible massive ramparts and simple brick walls of diverse buildings.

Main part of this city is its citadel – fortified central part of the city. This rectangular area is 1,523 km long from north to the south and 1,371 m wide in east – west direction, enclosing an area of 185 ha. The impressive brick ramparts around the citadel have been preserved up to this day and rise up to 11 – 13 m high above the surroundings. Around the walls was made also a ditch which also partly has been preserved.

Structures inside the citadel

Citadel has several gateways – Kata Duar in the north, Dorab Shah Toran in the east, Burir Fatak in the south and Tamra Dawaza in the west.

There are remnants of many interesting buildings inside the citadel. Some of these structures are:

- Bairagir Bhita – palace for women – hermits, built in the 4th – 5th century AD.

- Jiat Kunda – well which, according to legends, possessed life giving power. According to legends dead soldiers were revived with its water during the fights.

- Khodar Pathar Bhita – Buddhist shrine.

- Munir Ghon – impressive bastion.

- Parasuramer Basgriha – palace of king Parasuram, in use from 800 AD to 1800 AD.

Structures outside the citadel

Hundreds of mounds scattered for kilometres to the north, west and south from the citadel testify that Mahasthangarh was a true metropolis also by today’s scale. Each of these mounds hides some important ancient structure or group of structures. Most of these mounds are unexplored up to this day, but some of the most interesting explored sites are:

- Govinda Bhita – temple of Govinda is located to the north-east from the city walls, at Karatoya river. This is ancient building, possibly from the 3rd century AD, although here have been found artefacts from the 3rd century BC.

- Mazar – holy tomb of Shah Sultan Balkhi Mahisawar with later built mosque next to it. This structure is located at the south-eastern corner of citadel, in the site of an ancient Hindu temple.

- Gokul Medh is located some 3 km south from the citadel. This Buddhist monastery belongs to most impressive archaeological sites in this area. This enormous structure was excavated in 1934 – 1936, when 172 rectangular blind cells were exposed. Gokul Medh was built in the 6th – 7th century AD. On the top of this approximately 13 m tall structure was standing stupa which is lost now.

Mahasthangarh is one of the oldest ancient cities discovered so far in Bangladesh. Its true age is unknown, but the oldest dated artifact here is an inscription from the 3rd century BC. It is written in Prakrit – Indo-Aryan language.

City though could be much older, even from the 7th century BC.

Its current name – Mahasthangarh – comes from the medieval times and in Sanskrit means a place of sanctity ( Mahasthan ) and fort ( garh ).

Capital of Pundravardhana

Mahasthangarh is the former capital of Pundravardhana – the state of the Pundra people. This was an ancient state, founded by a little-known culture that spoke in a language which does not belong to the Indo-European family.

Initially Hinduism was the main religion here but it is assumed that Buddhism came here already before the 3rd century BC. This new religion did not come without conflict – thus some 18,000 followers of Ajivika philosophy were killed upon the orders of Mauryan Emperor Ashoka in the area of Pundravardhana.

Mahasthangarh developed as an important inland port with an intense connection to the seaport of Chittagong.

Medieval times

In the 6th century Pundravardhana most likely became a part of the Gauda empire and did not exist as a separate political unit anymore.

Importance of Mahasthangarh decreased together with the decline of Pundravardhana, although the city was enormous and continued to be inhabited for centuries long. In the 8th – 12th centuries it was an important center of Buddhist religion as testified by numerous large monasteries built in this time here.

Local people were converted to Islam in the 14th century AD by Shah Sultan Balkhi Mahisawar, who resided in Mahasthangarh after he took it with force from Raja Parshuram in 1343. His tomb (mazar) is located in the ancient city.

Fortifications of Mahasthangarh were used until the 18th century (and even during the liberation war in 1971) but it was never fully abandoned – Bangladesh is too densely populated to afford such a luxury.

First European to visit this ancient city was explorer Francis Buchanan Hamilton in 1808. Another explorer – Alexander Cunningham identified this ancient site as the capital of Pundravardhana in 1879.

In 1928 there were started excavations by Kashinath Narayan Dikshit, Archaeological Survey of India. Soon after the inside of the citadel was cleaned – before the excavations it looked rather like a hill. Excavations continue up to this day and we can be sure that scientists will have here enough work for centuries. Researchers have identified in the cultural layer of this ancient city 18 construction layers from different periods.

Mahasthangarh does not belong to the most spectacular landmarks but nevertheless, it is popular among people interested in history. It is also a sacred place for Hindus. Next to the site is built a museum which contains many items which have been found during the excavations.

Unfortunately Mahasthangarh is endangered – an unknown quantity of artifacts are stolen from the hundreds of unexplored mounds, the site is also endangered by swamping.

- A. K. M. Yaqub Ali. Pundranagara: an Emporium of North Bengal. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Vol. 53, No.1., June 2008, Dhaka.

Linked articles

Wonders of Bangladesh

The densely populated Bangladesh has had large and influential cities for millennia long. The country is rich with interesting archaeological heritage, such as remnants of viharas – Buddhist shrines and monasteries and abandoned ancient cities.

Abandoned cities and towns

The main impression created by abandoned cities is intimate. This is a mixed feeling of sadness, unclear anxiety (“my city will not be eternal either”), and at the same time – inspiration from the abilities of our ancestors. Long ago, without electricity, paper, or different mechanisms, they managed to create magnificent structures, that covered many square kilometers.

Ancient cities and towns

It turns out that urban planning is a very old profession. The urban fabric of ancient settlements – their structure and evolution gives a lot of food for thoughts about the nature of humans and civilization.

Wondermondo includes in the category of ancient cities and towns those settlements which have developed as urban areas at least 1500 years ago: around 500 AD.

Recommended books

A history of bangladesh.

Bangladesh is a new name for an old land whose history is little known to the wider world. A country chiefly famous in the West for media images of poverty, underdevelopment, and natural disasters, Bangladesh did not exist as an independent state until 1971.

Bangladesh (Bradt Travel Guide)

This updated guidebook, with a focus on responsible tourism, offers greater coverage than any other to the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and to the world’s largest mangrove forest at the Sundarbans. Personal insights guide travelers to aspects of the country almost unknown to visitors – dolphin and whale watching, winter bird-watching, and golden Bengal’s silk and archaeological highlights.

Mahasthangarh, the ancient capital of Pundra

Mahasthangarh (or Mahasthangar ) is an archaelogical site that is located in Shibganj upazila of Bogura district , Bangladesh. This is one of the oldest archaelogical sites from Bangladesh which is dated 300 BC. That time this place was the capital of Pundravardhana , and a lot of architectural components are scattered around the place.

Mahasthangarh museum

This nice little museum also works as a visitor center for the tourists. This remains open from 9am – 5pm during winter, and from 10am – 6pm during summer time. This remains closed on Sunday, and Monday it is half day closed. During any government holiday this place remains closed as well. The museum is rich with numerous collections such as statues, coins, weapons, etc which were found after the excavation from the archaeological sites around the Mahasthangarh .

Gobinda Vita

Govinda Vita is another archaeological spot from the Mahasthangarh (which is at the opposite of the museum). This is situated just beside the famous river Korotoa . Few important antique objects were discovered around the Govinda Bhita , such items are cast copper coins, silver coins, NBP wares, terracotta female figurines with sunga affinities, terracotta seal bearing Brahmi script and semi precious stone beads.

Shila Debir Ghat

Shila Debir Ghat is another archaeological spot which is situated approximately 200 meter from the Mahastangarh , and it is beside the river Korotoa . According to the legend, Shila Debi was the beautiful daughter of the king Parshurama , some scholars use to say she was the sister of the King Porshurama . After the war with King Shah Sultan , Shila Debi jumped into the Korota river to save her honor, and drowned herself.

The place at the bank of the river is known as the Ghat of Shila Debi . But the scholars are considering this story as a myth. They believe that the original name of the place was Shila Dvipa which means the island of stone. Anyway, the Hindus celebrate the Paus Narayani Bath annually at the Ghat.

Jiyat Kunda

Jiyat Kunda (or Jiyat Kua ) is a water well having a diameter of 3.86 meter. To ease the water crisis during the ruling period of king Porshuram this water well was established. People believe that the king Porshuram could bring life inside a dead body using the water from the well. But the well lost its spiritual power during the war with King Shah Sultan , when the Sultan dropped a piece of beef using the bird kite. This story is just a myth, but a lot of visitors pay a visit here for a while.

Gokul Medh is another archaeological site that is a part of the Mahasthangarh . But this place is slightly far from the other attractions. Local people believe this as a Bashor ghor of Behula and Lakkhindar . This place requires a separate ticket to enter and it has an opening and closing time too. Read more about Gokul Medh .

Mahastangarh is located just beside the Bogura – Rangpur highway. You could take a bus to Rangur from Dhaka and leave it near Mahasthan . From there it is just a few minutes of rickshaw distance. Alternatively you could take the bus of Bogura and then catch any inter district bus for Mahasthan . There are several bus services departing for Bogura and Rangpur from the Kolyanpur of Dhaka . It takes around 8-10 hours of overnight bus journey depending upon the traffic condition.

Where to stay:

Bogura town has a lot of excellent quality hotels for staying. Hotel Naz Garden is the best quality one from the district. you could stay there if you do not have any tight budget. For me, I stayed in the hotel Red Chillies from the town. It was a modest quality guesthouse with reasonable prices.

Mahasthangarh, Village: Mahastan, Upazila: Shibganj, District: Bogura, Country: Bangladesh.

Written by Lonely Traveler , For blog alonelytraveler.com

Friday, 28th May 2010

Share this:

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Comments are closed.

Popular posts

Sorry. No data so far.

Recent posts

Bangladesh In My Eyes

Travel - Photography - Tourism

- Privacy Policy

Search This Blog

Monday, july 15, 2013, mahasthangarh, bogra, rajshshi division, mahasthangarh, gokul medh (behula lokhindorer bashor ghor), hazrat shah sultan mahmud balkhi mahisawar (rh), parasuramer palace, jiyat kunda (the well of life).

Comment and Post on Facebook

5 comments:.

actually i liked the structure. we spend less than an hour in mohasthan gorh, which is very little to know and get overview. wish get back there and see all over the place.

The site is helpful for traveler. Distance Between Dhaka and Bogra is 163.86 kilometers or 101.82 miles.

Sorry for late reply. Thanks for your information. I feel good when people give informative comments.. :)

Hello Admin, How do you do? I hope you are doing well.I like your post verry much, for your amzing thinking.Visitors of another occasion, we were not aware of the arranging procedure at this inside, however we had a great time there as visitors. While it's continually energizing to be facilitating the occasion, we got ourselves altogether getting a charge out of the occasion and pleasantries as visitors, You will do remarkable in future. please chake this out -Read about: Hotel in Rajshahi Thanks sahsa loren

Thanks a bunch for sharing this with all of us you really recognise what you're speaking about! Bookmarked. Please also visit my site =). We can have a hyperlink change contract among us craigslist atlanta

I truly appreciate the time you have spent here. Please like and share my post and give good comments to encourage my hard work. Those who do not have any id use Anonymous or Name/URL (only name, no URL needed) to post your comment. Have a great day !!

Mahasthangarh: Exploring the Ancient Ruins of Bangladesh

- Bichanakandi National Park

- Kaptai National Park

- Khagrachari National Park

- Lawachara National Park

- Madhupur National Park

- Nijhum Dwip National Park

- Sajek National Park

- Satchari National Park

- Sundarbans National Park

- Dhaka

- Barisal

- Bhairab

- Bogra

- Brahmanbaria

- Chittagong

- Comilla

- Gazipur

- Jamalpur

- Khulna

- Mymensingh

- Narayanganj

- Narsingdi

- Pabna

- Rajshahi

- Rangpur

- Saidpur

- Sylhet

- Tangail

- Tongi

- Ahsan Manzil

- Bandarban

- Bishwa Ijtema

- Boga Lake

- Chittagong Hill Tracts

- Cox's Bazar

- Kuakata

- Lalbagh Fort

- Madhabkunda Waterfall

- Mahasthangarh

- Mainamati

- National Martyrs' Memorial.

- Nijhum Dwip

- Paharpur

- Rangamati

- Ratargul Swamp Forest

- Srimangal

- St. Martin's Island

- Sundarbans

- Our Mission

- Mahasthangarh, Bogura

by Setvertex | Dec 6, 2023

Mahasthangarh, Bogura: Unraveling the Ancient Mystique of Bangladesh’s Archaeological Gem

Nestled in the heart of Bangladesh, Mahasthangarh in Bogura stands as a silent witness to centuries of history, an archaeological marvel that echoes the tales of ancient civilizations. As one embarks on a journey to this sacred site, a profound connection with the roots of Bangladesh’s rich heritage unfolds.

Historical Significance

Mahasthangarh is not just a name; it is a portal to a bygone era. This ancient city, believed to have been inhabited continuously for over two millennia, holds the key to understanding the evolution of human civilization in the region. Its roots can be traced back to the 4th century BCE, making it one of the oldest archaeological sites in Bangladesh.

Capital of the Pundra Kingdom

In antiquity, Mahasthangarh served as the capital of the Pundra Kingdom, a powerful and culturally rich civilization. The archaeological remnants unearthed here include city walls, ancient moats, and structural ruins that whisper tales of a once-thriving metropolis.

Citadel Remnants

As visitors tread the grounds of Mahasthangarh, the remnants of the citadel walls transport them back in time. The sheer scale of the fortifications is a testament to the strategic importance the city held in its heyday.

Votive Stupas and Temples

Scattered across the site are numerous votive stupas and temples, each with its unique architectural nuances. The Vasu Bihar, an ancient Buddhist monastery, stands as an epitome of the architectural brilliance of that era.

Treasures Preserved

To delve even deeper into the history and culture of Mahasthangarh, a visit to the on-site museum is a must. The museum houses a diverse collection of artifacts, including pottery, sculptures, and ancient inscriptions, providing a comprehensive overview of life in this ancient city.

Conservation Efforts

Preserving Mahasthangarh is a shared responsibility, and ongoing conservation efforts aim to protect and showcase this archaeological gem. The delicate balance between exploration and conservation ensures that future generations can continue to marvel at the wonders of this ancient city.

Conclusion: A Journey Through Time

Mahasthangarh, Bogura, is more than an archaeological site; it is a pilgrimage for those seeking a profound connection with the roots of Bangladesh. As visitors wander through the remnants of ancient structures and reflect on the stories etched in stone, Mahasthangarh becomes a living testament to the resilience of human civilization.

In the embrace of Mahasthangarh’s historical aura, one can’t help but feel a sense of awe for the countless generations that once called this place home. As the wind whispers through the ancient ruins, it carries with it the echoes of a time long past, inviting all who listen to embark on a timeless journey through Bangladesh’s rich heritage.

Recent Posts

- Exploring the Rise and Fall of Nalanda University

- History of Origin and Development of the University

- Rulers Who Built Vast Empires From Nothing

- Exploring the Timeless Beauty of Panam City, Sonargaon

Recent Comments

Take advantage of the search to browse through the World Heritage Centre information.

Share on social media

Unesco social media, cultural landscape of mahasthan and karatoya river.

The Tentative Lists of States Parties are published by the World Heritage Centre at its website and/or in working documents in order to ensure transparency, access to information and to facilitate harmonization of Tentative Lists at regional and thematic levels.

The sole responsibility for the content of each Tentative List lies with the State Party concerned. The publication of the Tentative Lists does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever of the World Heritage Committee or of the World Heritage Centre or of the Secretariat of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its boundaries.

Property names are listed in the language in which they have been submitted by the State Party

Description

Mahasthan (literally meaning maha = great and sthan = place in Bengali) is in Shibganj Upazila of Bogura district, under the Rajshahi division of Bangladesh. Mahasthan is located on the west of the Bogura-Rangpur highway and is about 12km north of the Bogura district headquarter and to the western bank of the currently seasonally active channel of the Karatoya River. These archaeological sites and the riverine alluvial landscape at Mahasthan, featuring the Karatoya River, represent the complex interaction of cultural activity and natural landscape to an extent that the landscape, river, waterbody and cultural activities over 2400 years have become entangled. The cultural landscape in this area, moreover, represents the entwinement of tangible and intangible aspects of heritage. The landscape and rivers have continued to be part of popular imagination and local legends and myths. They are also an essential component of local religious rituals belonging to different religious traditions – Islamic, Hindu and other sects. This property can be defined under the second sub-category of the second category of cultural landscape as ‘continuing landscape is one which retains an active social role in contemporary society closely associated with the traditional way of life, and in which the evolutionary process is still in progress. At the same time, it exhibits significant material evidence of its evolution over time.’ In this place, popular folktales, legends, religious rituals, and archaeological remains have manifested inseparable association and influence of waterscape and landscape in the area, especially the Karatoya River.

The archaeological context of Mahasthan can be broadly represented by a citadel and numerous archaeological sites in the form of structural and habitational mounds, monumental remains, and old tanks. The citadel is known as Mahasthangarh and it is characterized by fortified urban centres of early Bengal. The urban centre was established around the 4 th -3 rd century BCE on the bank of the Karatoya River. Archaeological studies since the later part of the 19 th century to date have exposed several facets of the rich and evolving history of the place as an urban centre. Excavations in the citadel area and radiocarbon dating of the stratigraphic context have established that the human activity in the citadel area continued to date with several periods of transformation. The fortified citadel is the core urban centre and it measures roughly 1.52km (north to south) by 1.37km (east to west), with high and wide ramparts in all its wings. Other sites, both excavated and unexcavated, are distributed around this core citadel area. Most of the excavated sites are religious monumental remains including Buddhist monasteries, Brahmanical temples, mosques and mazars (tombs of Muslim saints).

The urban centre was known as Pundranagara according to various textual sources belonging to the 7 th century CE and later. According to the excavation and geoarchaeological research in the area, the urban centre with the first fortification wall was built with mud around the 4 th century BCE during the Mauryan period. A fragment of a stone inscription written in Brahmi script represents the importance of the settlement, where the administrator of the settlement was asked to help the poor during the time of calamity. Scholars think that this inscription can be dated to the time of the Emperor Asoka. The urban centre became the administrative centre and capital of Pundrabardhana bhukti, a unit under Gupta and later, Pala and Sena rulers.

During the 13 th century, the capital city was partly destroyed by a massive earthquake. The human occupation continued here in various parts inside and outside the citadel area. The mazar of Sultan Mahisawar (r.) and Borhanuddin, two Muslim Sufi saints, became the hub of ritualistic gathering and ceremonial activities during the 15 th -16 th century CE. The mazar of Mahisawar was constructed on the abandoned citadel wall in the 15th century CE or earlier.

Among other archaeological sites around Mahasthangarh, the monastic complex at Bhasu Bihar, the temple built with a cellular technique at Gokul Medh, the temples of Bihar Dhap, Govinda Bhita, Mangolkot and several other excavated places, and more than a hundred unexcavated mounds within 15-20km of the citadel area testify to the immense significance of this area as a nodal zone of administrative, political, cultural, economic and religious activities for nearly two and a half millennia.

The settlements and religious edifices around this centre in the hinterland zone of the urban core are difficult to define with regard to a specific spatial boundary, partly because of the lack of archaeological research in the hinterland zone and partly because of the nature of the archaeological remains which are spread over a considerably large space. Yet, for the purpose of proposing the property of Mahasthan and Karatoya River as a cultural landscape, the area with the highest density of the sites to the north, west and south has been taken into consideration. The most dense occurrences of the sites extend 6-8km to the north, 8km to the west and 10km to the south of the citadel. This spatial boundary is drawn as a requirement for this proposal, though considering the landscape and its use, the boundary can be extended further in these directions, and also to the east of the Karatoya River.

The landscape context can be broadly divided into two units on the basis of their geological and geomorphological characteristics, and also, on the basis of the historic land-use pattern. The citadel and around the citadel are situated on a terrain which is recognized as Barind Terrace. This terrace is tectonically uplifted and characterized by Pleistocene deposits with yellowish-red to reddish-brown clay and sandy clay. Barind Terrace with the citadel and most of the sites to the right bank of the Karatoya River are on the bank of the Karatoya River (and its tributaries like Bangali) and the Karatoya River cuts an alluvium deposited by the Brahmaputra-Karatoya Rivers during the Holocene period. The older alluvium of Barind Terrace and the recent alluvium of the rivers played a critical role in the formation, evolution and transformations of the archaeological and cultural pattern of landscape use and modifications.

The scholarly works have suggested that the formation of the urban core was controlled by its location in the margin of the Barind Terrace, on the bank of the Karatoya River. The fortification wall gradually evolved from a mud wall into an extensive brick-built rampart that was essential for defence as well as for the protection of the core urban area from floods and inundations which were regular during the peak Indian summer monsoon (ISMR). The riverine route was, moreover, the route for communication and trade with the sub-regions to the northern, southeastern and southern parts of Bengal. The location of the citadel and the settlements sites in the hinterland were, thus, partly controlled by the fluvial network and fluvial landscape. Distributaries of the Karatoya River like the Nagar River and several other palaeo-channels have differential implications on the human activity pattern and history in this area.

The Barind Terrace, though predominantly characterized by the yellowish-red and reddish-brown old alluvium, has micro-scale variabilities in the hinterland zone. The zone is marked with moderate undulations, wetlands and lowlands characterised by dark-grey to greyish clayey soils. Several structural remains of the archaeological mounds were constructed by careful adaptations and modifications of these landforms. The formation of the settlements in Mahasthangarh was controlled by the landscape context, as the recent studies suggest. The landscape was covered densely by lowlands and wetlands before the formation of the urban core around the 5 th -4 th centuries BCE and it was not suitable for human occupation and construction of an urban centre as large as Mahasthangarh. The studies also suggested that it was during the expansion of the Mauryan empire, this place, with its unique location in the intersection of recent and old alluvial terrain, became suitable for the development of an urban landscape. The recent alluvium offered the suitable terrain for the agrarian expansion and the supply for surplus production for the sustenance of the urban settlement. The fluvial network, in which the Karatoya River became pivotal for communication and trade, offered the perfect landscape for the development of an urban landscape that continued until the 13 th century CE and with the evident decline of the landscape and dwindled riverine network, the occupation continued in various patches in a semi-urban or rural character.

Many tanks were excavated outside the citadel area for purposes like irrigation, supply of drinking water, and for ritualistic purposes. These tanks manifest the modification of the landscape for different settlement activities for more than 2400 years. There are the remains of an earthen wall, popularly known as Bhimer Jangal, which had acted as an embankment and pathway. A major portion of the earthen wall has been destroyed by human activities during the last 50-60 years. The popular memory, however, narrates this earthen wall as a signature of the Kaivarta rebellion in the 11 th century CE.

The examination of the Mahasthan and the human activity in this place overtly manifest the symbiotic relationship between culture and nature, between cultural activities and their changes and landscape-waterscape. The intimate interrelationship becomes explicit in the ways the human perception and actions are shaped by the landscape variables.

Karatoya Mahattyam, a poetic composition belonging to c. 13 th -14 th century CE, belongs to the category of texts known as sthal-purana (a specific type of Purana, or mythical narration of time and events, representing the supernatural and sacred qualities and characters of a place). It was in the verses of this textual composition that the place name of Mahasthan occurred first. The text also attests to the fact that Mahasthan is the location of the great urban centre of Pundranagara. The entire composition illustrates the great sacred qualities of the Karatoya River and the place of Mahasthan. The place (and the landscape) were perceived in this purnara as possessing the power of healing, the emancipation from sins and the ascribing of merit to sincere devotees. The water of the Karatoya River was perceived as sacred and possessing miraculous powers. Bathing in the water of the river was considered as a holy and merit-gaining act. Mahasthan, in association with the river, gained equivalent miraculous power, according to the text. Living in this land was narrated as a holy achievement in human life.

In a similar way, Mahasthan is perceived and experienced as a holy and sacred place, as the location of the mazars of Hazrat Shah Sultan Mahisawar (r.) and Sheikh Borhanuddin (r.), two great Sufi saints of medieval Bengal. The grave of Mahisawar is considered by the local people, irrespective of their religious identity, as possessing miraculous powers to heal, to fulfil the desires, and to giving merits to devotees. The archaeological remains, such as khodar pathar bhita, jiyat kunda and several other features in the landscape close to the southern part of the citadel, are considered as sacred and worshipped by the local people.

The sacredness of the river, land and archaeological remains are celebrated annually, first, by the huge gathering of the people belonging to the Hindu community for bathing in the river water in the months of March-April and secondly, by the gathering of thousands of devotees during the uras (a sacred gathering and ritualistic activities to commemorate the birth or miraculous acts of a holy Sufi saint or pir in Bengal) each year on the last Thursday of the Bengali month of Baisakh (the months of April-May in the Gregorian calendar).

The existence of the tangible remains are often perceived, lived and narrated in the tales and poems representing the holy miraculous acts of the Sufi saints. The places and remains are actors in popular mythical narratives from the Manasa mangal kavya (a category of poetic narrations of different local deities among the Hindu community of Bengal). For example, the moat and the wetland to the west of the citadel are recognized as the Kalidaha sagar (a big water body name Kalidaha) where the boats of the merchant Chad anchored. The places are identified in the popular narratives as associated with these characters and events from a mythical past. Interestingly, the narratives which are constructed by the archaeological and historical discourses are not known or popular among the larger section of the people. These narratives clearly show that people may have different and heterogeneous perceptions and associations with their pasts. The archaeological places of Mahasthan are kept alive and significant by the religious rituals, popular folklores and the pluralistic relationship of landscape, river, archaeological places and the people living with the places at the present. The landscape of Mahasthan attains a very different meaning, albeit very distinct from the mainstream historical and archaeological meaning and narration style, as a living religious place and as a landscape vibrant with living religious traditions.

The tangible archaeological remains, therefore, become the sites for popular mythical perception as well as for the religious rituals, blurring the boundaries between history and myth, real and unreal, secular and religious and dead traditions and living religious traditions. The cultural landscape of Mahasthan and Karatoya River, eventually, illustrate the multivocality of the past at the present. It represents the pluralistic, heterogenous and concurrent existence and continuity of different traditions at a place that is characterized by the entanglement of cultural activities and natural processes, of the land, water and people.

Although hundreds of archaeological sites and places have been recorded in the area, many of them have been destroyed and obliterated to an extent that they cannot fit within the standards of authenticity and integrity. Among these sites, sixty-two components are proposed within this property. Hence, the sites which comply with the accepted Nara Document on Authenticity are listed above. It must be stated that the Karatoya River, with its connected channels and palaeo-channels (seasonally flooded) associated with the area of the site, is also included as a component, though they have not been listed in the table. The area covers more than 80 sq. km and there are many cultural remains and features within this zone which lack intensive inspection and surveying. Subsequent research may add more properties to this list.

The Karatoya River to the south and southeast of the urban area and the Nagar River to the north of this property must be included as the landscape component of this property. As natural features, they are owned by the state authority and managed by the local communities.

Justification of Outstanding Universal Value

Criterion (i): From the 4 th -3 rd century BCE to the 18 th – 19 th century CE, this property represents unparalleled, innovative and flexible human activities to build a large city with numerous monuments, artificial water bodies and modified landscapes around the city. The fortification wall of the citadel represents the transformation from an earthen wall into a massive brick-built rampart with bastions, with the modification of the landscape and with the adaptation with the floodplain of the Karatoya River. The citadel and the monumental remains are located on the uplifted terrace of Barind and the moat of the citadel is connected to the Karatoya River. The western part of the citadel has a water body which is also enclosed by the fortification wall and is connected with the low land (bill), which is locally known as Kalidaha Sagar. This is an outstanding example of the use and modification of a natural water body for maintaining connectivity and communication through the water of the artificial moat and the natural fluvial network mediated by the Karatoya-Nagar and other rivers. To the west and the north of the citadel, a vast area characterized by natural wetland was brought under use for habitation and cultivation by harvesting water through tanks and the seasonal use of water in the wetlands. Several monumental remains in this zone are either enclosed by natural waterbodies or by artificial moats. Remnants of palaeo-channels connected to the Karatoya River and the Jamuna River (also known as the Brahmaputra River upstream) vividly illustrate the cohabitation of the natural and the cultural on a wide area. The area between the currently moribund channels of the Karatoya River and the Jamuna River represents an alluvial terrain that is as dynamic and changing as it is fertile. This floodplain is marked with numerous abandoned river beds, oxbow lakes and back swamps. Despite the changes in the fluvial system, the cultural activities continued to flourish with certain ups and downs in the entire city and the hinterland zone for more than two millennia. Excavated data from the citadel and outside (e.g., excavated Buddhist and Brahmanical remains of Bhasu Bihar, Bihar Dhap, Govenda Bhita Temple, Gokul Medh, etc) show that attacks from outside and natural disasters were common in this area. The evidence of the attacks and breaking of the fortification wall as well as the evidence of a massive earthquake and partial collapse of the urban area around the 13th century are well attested by radiocarbon dating. Floods and consequent changes in the fluvial environment were perpetual. In spite of all these obstacles, a formidable centre of administrative, economic and religious activity was established, maintained and continued by taking the urban area as its focal point and by adapting to the landscape-waterscape around the city. The city represents intense cultural activities both during the phases of second urbanism in the Ganges-Jamuna plains extending from the western part of present India to the east up to Mahasthangarh in the 4 th -3 rd century BCE. In that sense, the city and the vast hinterland represents the easternmost detectable large urban proliferation despite the dynamic landscape. Simultaneously, the archaeological evidence suggests that the city flourished after a period of decline again in the period of third urbanism in South Asia in around the 8 th -9 th century CE. Various studies by the Bangladesh-France joint team and their publications represent irrefutable evidence of the close and intimate interaction between human activity patterns and changes in natural features including the landscape. Human creativity cannot be better portrayed in the enterprises and actions of adapting to nature.

Criterion (ii): As has been elaborated in the justification of the criteria (i), the cultural activities in this urban area and its hinterland zone continued over two millennia. Following is a table representing the stratigraphic evidence of the continuity gleaned from the excavation by the Bangladesh-France Joint Team in Eastern Rampart Area within the citadel (Alam and Salles 2001).

The cultural materials from the excavations and the excavated monumental remains including Brahmanical, Buddhist, Jain and Islamic edifices illustrates the exchange of human values through overland and riverine routes. For example, similar and analogous cultural material including Northern Black Polished Wares (NBPW), Rouletted Wares (RW), Moulded Terracotta Plaques with specific ‘Sunga style’, Bronze objects including mirrors and sculptures, stone made religious and non-religious objects, etc. are so abundant that it is evident that trade and commercial activities and exchanges of religious ideas were continuous. Chinese Pilgrims Zuan Jang’s (Hiuen Tsang) description in the 7 th century CE about the glorious and thriving religious activities in these sites is one of several examples. As an urban centre surrounded by many monastic establishments and temples, the scholastic studies suggest, the city and its hinterland zone were vibrant with pilgrimage and mercantile activities. It has also been suggested that the fluvial networks through the Karatoya-Brahmaputra River system enabled communication with the Himalayan piedmont zones in the north and to the maritime routes to the south in the Bay of Bengal.

Criterion (iii): The aforementioned text of Karatoya-Mahatyam of the 13 th -14 th century CE clearly indicated the sacred qualities of the land of Mahasthan and the Karatoya River. The water of the river was considered as possessing supernatural sacred qualities. This ancient text narrated the annual bathing in the river to gain merit according to Hindu tradition. The tradition of ritualistic bath in the river continues up to the present.

At the same time, the mazar of Shah Sultan Mahisawar (ra.) is the location of huge annual gatherings and pilgrimages by the adherents of various Sufi sects, pious Muslims and Hindus. In the month of April, the gathering gains special significance through various ritualistic activities and gathering, musical performances and embodied ritualistic activities. These traditions have their historicity from at least the 15 th -16 th century CE or earlier.

The pluralistic, tolerant and syncretistic religious and ritualistic traditions are nowhere better represented than in Mahathan and Karatoya Rivers. The religious traditions of the property similarly attest to the intimate inter-relationship between human beliefs and rituals and the natural features. The waterscape, especially the rivers, have shaped the symbolic as well as the perceptions of the inhabitants in this area for a long time. The landscape and waterscape were not only related to human activity in a functional sense. The inseparable existence of the tangible and the intangible is represented by the oral histories, folktales and legends which borrow from the rich literary traditions of Bengal. An example may be given here of the identification of the several archaeological sites and wetlands with the narratives of Manasa Mangala Kavya of the medieval period.

Criterion (vi): Mahasthan and Karatoya River are entangled entities as a locus of cultural activities, symbolic perception, continuous oral traditions of narrative making, literary creation, and human experiential and phenomenological engagement with the landscape. The traditions continue with their transformations and obstacles despite various modern and colonial interventions. The living traditions of storytelling, folklore, oral history in song, poetries and dances, and performative embodied actions are quite unique as they show the deep, inseparable and juxtaposed human and non-human, human and landscape and human and river actions and mobilities. These traditions and events of celebrating these traditions have a universal significance in terms of the ways human perceptions and senses are shaped by as well as refashion the natural environment around them.

Statements of authenticity and/or integrity

Authenticity

The excavated, conserved and protected archaeological sites and their landscape at Mahasthan in relation to the Karatoya River System undeniably represent the authentic attestation of human creative and building technologies and their use of the landscape. These sites and the landscape proposed for nomination as a complex or cluster of properties were constructed mainly by burnt bricks, mud, earthworks and clay, and lime-surki mortars, with occasional use and reuse of stone blocks. Evidence of plasters of lime and clay are also recovered. The excavations revealed the architectural remains of various natures. The cellular temple of Gokul Medh, the massive brick and stone-built fortifications enclosed by a moat, the construction of habitations and monuments within wetlands, and the excavated tanks – all represent the most authentic human-landscape interaction, both functionally and symbolically. Thick and sequential successive occupation deposits and objects of innumerable types were found and preserved. The remains were found incomplete and having gone through weathering and damage done by the passage of time. The remains, nevertheless, have provided evidence based upon which the original characters and layout of the buildings and associated landscape, the traditional construction materials and techniques, and the common regional use of clay for producing bricks as well as for binding the construction material can be inferred with a high degree of precision.

Because of the recent expansion of developmental and habitational activities, many of the sites have already been destroyed. The proposed properties represent the selected sites which are well preserved and compatible with the guidelines of the World Heritage Convention. The Karatoya River with its abandoned beds is also clearly detectable and manageable through a planned river management initiative. The impact of natural processes has been reduced by the continuous protection and conservation as well as monitoring of the properties. The modification of the landscape is increasing because of human activities in a densely-populated country like Bangladesh. The continuous monitoring of the Department of Archaeology, Ministry of Cultural Affairs of these sites protected under the Antiquity Act, 1972 have retained the original nature and character of the sites when they were exposed by excavations. Several proposed sites are under private ownership and they can be protected and preserved without evicting the people living around them. The conservation of excavated remains has followed international conventions and standards in protection and conservation. These sites are major tourist destinations of the region. Proposed sites such as the mazars of Shah Sultan (ra.) and Borhanuddin (ra.) are communal properties and they are continuously being reused for living religious traditions. As communal places of worship and the continuous focus of living religious traditions, sites like these are proposed despite their changes and renewal by the communities around them. These sites represent the religious sites around the world that are recognized by UNESCO under the conventions of protecting the places of living religious traditions. The landscape around the Karatoya River which is the centre of living ritualistic traditions are well protected by the communities around the sites. The touristic activities are controlled and managed according to the accepted guidelines and as per the required accountability and community-oriented engagements.

Comparison with other similar properties

The cultural landscape of this proposed property can be compared to the Bam and its Cultural landscape of Iran. Located on the Iranian high plateau, the urban centre of Bam and the hinterland of this city can be dated back to the Achaemenid period (6 th to 4 th centuries BC). Its heyday was from the 7 th to 11 th centuries, being at the crossroads of important trade routes and known for the production of silk and cotton garments. Bam is closely connected to the arid desert environment and landscape. On the other hand, Mahasthan is intimately connected to its fluvial landscape. Arg-e Bam is one of the most outstanding examples of a fortified medieval town/city like Mahasthangarh and it represents the adaptive tradition of human activities.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Role of Stakeholders in Heritage Management in Bangladesh: A Case Study of Mahasthangarh

2020, CenRaPS Journal of Social Sciences

The notion of stakeholders is becoming increasingly significant in heritage management activities and planning. It is commonly argued that individuals, groups, organizations, environs, societies, institutions, and even the natural environment can be potential stakeholders. However, most of the case heritage sites are impacted and concerned by particular stakeholders such as the local community, regional government, and NGOs. Every project has stakeholders who can influence or be influenced by the project in a positive or negative manner. Mahasthangarh and its environs are a potential heritage site of South Asia that helps understand the chronological history and cultural development of Bengal Civilization. Like many other heritage sites in Bangladesh, Mahasthangarh faces serious threats and challenges which are damaging and waning its outstanding universal value of tangible and intangible heritage. Since site managers involve potential key stakeholders to enhance the sustainable heritage management, planning, reduce the possibility of conflict, increase the stakeholders' ownership through regular communication, raising awareness, educational activities, and building campaigns, and to augment the community's trust in heritage management; without the effective role of stakeholders, the outcomes are precarious and can be catastrophic. The paper will demonstrate the possibilities of using the roles of stakeholders as potential tools for safeguarding and managing the heritage site by using Mahasthangarh and its environs as a case study.

Related Papers

Neel Kamal Chapagain

Pre-Conference Proceedings of the 2nd Edition of International Conference on Heritage Management Education and Practice: Developing Integrated Approaches, held at Ahmedabad University, Ahmedabad, India on 14-16 December 2018. More information and for the upcoming editions, please visit https://ahduni.edu.in/chm/

Journal of Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

Maliha N A R G I S Ahmed

Mahasthangarh, the ancient Pundranagara is located in Bogura district of Bangladesh. By far it is one of the earliest urban settlements of Bangladesh being discovered and excavated. The site museum of Mahasthangarh was established almost after three decades since its excavation was done. At present the small hall room type museum houses a good number of Hindu and Buddhist sculptures (Stone, bronze and terracotta) which were collected from numerous parts of Varendra region (region where the site was discovered) through different attempts of excavation and as well as exploration. Ideally a site museum contains materials directly related to specific site and its surroundings which refers at current case to the Mahasthangarh citadel and its connecting sites. But this aspect was not followed as part of salvage archaeology and budget constraints resulting museum authority to comprise with the authenticity and integrity of the museum's nature. So major collection of this site museum is sculptures found, discovered or excavated not from the site only but the Varendra region ranging the time frame from Sunga to Sena period. The museum representing the sculptures as form of art object and aestheticism, was prioritized while the display was designed. The concept of musealization (contextualization) was never considered during planning and exhibiting the display. Visitors often may get confused while viewing the museum objects on what is from Mahasthangarh site area and what is from the neighboring districts of Bogura and how these objects are chronologically or culturally related with each other. Current researchers conducted museum visit in person to identify different categories of sculptures in terms of chronology, material and religious creed (mainly Brahmanical and Buddhist). Identification and observations drawn on this process provides logic to the necessity of rearranging the display of sculptures within a temporal and thematic framework to highlight the stylistic evolution of sculptural art. Thus this paper trys to offer a new modernist approach in museum display at Mahasthangarh site museum of Bogura.

Ege Yildirim

As a key concept in the conservation of cultural and natural heritage, site management has been adopted by Turkey in recent years, both through the legislative reforms of the mid-2000s and cases of practical implementation. An important aspect of site management is its relevance for sustainable development, as it brings actors and interests representing both conservation and development, and thus presents opportunities for balancing and integrating these interests. A case study where all these themes can be observed is the Mudurnu Cultural Heritage Site Management Plan, both in its preparation in 2014 and its implementation process ongoing since January 2015. Situated in the northwestern Anatolian province of Bolu, Mudurnu was historically a strategic trading and military post due to its location on major routes including the Silk Road. In modern times, the town fell off the major transportation arteries of Turkey, but has preserved its rich legacy of Ottoman monumental and vernacular architecture, as well as its special intangible heritage of Akhism, i.e the Anatolian merchant guild system combining spiritual and commercial moral codes. As one of the outputs of the site management process, the town was inscribed on Turkey’s Tentative List for UNESCO World Heritage as ‘the Historic Guild Town of Mudurnu’. Better known in recent decades for its poultry industry, the town’s economy was hit hard by Turkey’s economic crisis of 2001, after which efforts began for revitalizing the town through cultural tourism. Building on these efforts, a site management plan was prepared and adopted for Mudurnu, becoming one of the few such plans in the country that has a rolling implementation process in action, with numerous projects and milestones achieved including the Tentative List inscription. Through the case of Mudurnu, this paper will explain specific issues of site management in Turkey in the context of small towns, such as the economics of decline and revitalization, tourism-related pressures and expectations, the historic urban landscape approach in a significant historic urban center set in a rural cultural landscape, regional perspectives for cooperation in cultural tourism, customizing administrative mechanisms for site management for small towns with an emphasis on volunteering, local ownership and capacity building, and prospects for actual World Heritage inscription. These issues will also be addressed in the context of current concepts prioritized by ICOMOS, such as in its Thematic Working Group for the Silk Road, and the themes presented in the UN Sustainable Development Goals that are relevant for urban cultural heritage.

Dennis Rodwell

Journal of Sustainable Tourism

Neelam Poudyal

World Heritage Watch

Gabriel Lafitte