This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Abegaz TM, Shehab A, Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, Elnour AA. Nonadherence to antihypertensive drugs. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017; 96:(4) https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000005641

Armitage LC, Davidson S, Mahdi A Diagnosing hypertension in primary care: a retrospective cohort study to investigate the importance of night-time blood pressure assessment. Br J Gen Pract. 2023; 73:(726)e16-e23 https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2022.0160

Barratt J. Developing clinical reasoning and effective communication skills in advanced practice. Nurs Stand. 2018; 34:(2)48-53 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11109

Bostock-Cox B. Nurse prescribing for the management of hypertension. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2013; 8:(11)531-536

Bostock-Cox B. Hypertension – the present and the future for diagnosis. Independent Nurse. 2019; 2019:(1)20-24 https://doi.org/10.12968/indn.2019.1.20

Chakrabarti S. What's in a name? Compliance, adherence and concordance in chronic psychiatric disorders. World J Psychiatry. 2014; 4:(2)30-36 https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v4.i2.30

De Mauri A, Carrera D, Vidali M Compliance, adherence and concordance differently predict the improvement of uremic and microbial toxins in chronic kidney disease on low protein diet. Nutrients. 2022; 14:(3) https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030487

Demosthenous N. Consultation skills: a personal reflection on history-taking and assessment in aesthetics. Journal of Aesthetic Nursing. 2017; 6:(9)460-464 https://doi.org/10.12968/joan.2017.6.9.460

Diamond-Fox S. Undertaking consultations and clinical assessments at advanced level. Br J Nurs. 2021; 30:(4)238-243 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.4.238

Diamond-Fox S, Bone H. Advanced practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Br J Nurs. 2021; 30:(9)526-532 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.9.526

Donnelly M, Martin D. History taking and physical assessment in holistic palliative care. Br J Nurs. 2016; 25:(22)1250-1255 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2016.25.22.1250

Fawcett J. Thoughts about meanings of compliance, adherence, and concordance. Nurs Sci Q. 2020; 33:(4)358-360 https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318420943136

Fisher NDL, Curfman G. Hypertension—a public health challenge of global proportions. JAMA. 2018; 320:(17)1757-1759 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.16760

Green S. Assessment and management of acute sore throat. Pract Nurs. 2015; 26:(10)480-486 https://doi.org/10.12968/pnur.2015.26.10.480

Harper C, Ajao A. Pendleton's consultation model: assessing a patient. Br J Community Nurs. 2010; 15:(1)38-43 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.1.45784

Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E. The Top 100 Drugs; Clinical Pharmacology and Practical Prescribing, 2nd edn. Scotland: Elsevier; 2019

Hobden A. Strategies to promote concordance within consultations. Br J Community Nurs. 2006; 11:(7)286-289 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2006.11.7.21443

Ingram S. Taking a comprehensive health history: learning through practice and reflection. Br J Nurs. 2017; 26:(18)1033-1037 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.18.1033

James A, Holloway S. Application of concepts of concordance and health beliefs to individuals with pressure ulcers. British Journal of Healthcare Management. 2020; 26:(11)281-288 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2019.0104

Jamison J. Differential diagnosis for primary care. A handbook for health care practitioners, 2nd edn. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006

History and Physical Examination. 2021. https://patient.info/doctor/history-and-physical-examination (accessed 26 January 2023)

Kumar P, Clark M. Clinical Medicine, 9th edn. The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017

Matthys J, Elwyn G, Van Nuland M Patients' ideas, concerns, and expectations (ICE) in general practice: impact on prescribing. Br J Gen Pract. 2009; 59:(558)29-36 https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X394833

McKinnon J. The case for concordance: value and application in nursing practice. Br J Nurs. 2013; 22:(13)766-771 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2013.22.13.766

McPhillips H, Wood AF, Harper-McDonald B. Conducting a consultation and clinical assessment of the skin for advanced clinical practitioners. Br J Nurs. 2021; 30:(21)1232-1236 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.21.1232

Moulton L. The naked consultation; a practical guide to primary care consultation skills.Abingdon: Radcliffe Publishing; 2007

Medicine adherence; involving patients in decisions about prescribed medications and supporting adherence.England: NICE; 2009

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. How do I control my blood pressure? Lifestyle options and choice of medicines patient decision aid. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/resources/patient-decision-aid-pdf-6899918221 (accessed 25 January 2023)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline NG136. 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136 (accessed 15 June 2023)

Nazarko L. Healthwise, Part 4. Hypertension: how to treat it and how to reduce its risks. Br J Healthc Assist. 2021; 15:(10)484-490 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjha.2021.15.10.484

Neighbour R. The inner consultation.London: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; 1987

The Code. professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates.London: NMC; 2018

Nuttall D, Rutt-Howard J. The textbook of non-medical prescribing, 2nd edn. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2016

O'Donovan K. The role of ACE inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2018; 13:(12)600-608 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2018.13.12.600

O'Donovan K. Angiotensin receptor blockers as an alternative to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2019; 14:(6)1-12 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2019.0009

Porth CM. Essentials of Pathophysiology, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2015

Rae B. Obedience to collaboration: compliance, adherence and concordance. Journal of Prescribing Practice. 2021; 3:(6)235-240 https://doi.org/10.12968/jprp.2021.3.6.235

Rostoft S, van den Bos F, Pedersen R, Hamaker ME. Shared decision-making in older patients with cancer - What does the patient want?. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021; 12:(3)339-342 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.08.001

Schroeder K. The 10-minute clinical assessment, 2nd edn. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2017

Thomas J, Monaghan T. The Oxford handbook of clinical examination and practical skills, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014

Vincer K, Kaufman G. Balancing shared decision-making with ethical principles in optimising medicines. Nurse Prescribing. 2017; 15:(12)594-599 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2017.15.12.594

Waterfield J. ACE inhibitors: use, actions and prescribing rationale. Nurse Prescribing. 2008; 6:(3)110-114 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2008.6.3.28858

Weiss M. Concordance, 6th edn. In: Watson J, Cogan LS Poland: Elsevier; 2019

Williams H. An update on hypertension for nurse prescribers. Nurse Prescribing. 2013; 11:(2)70-75 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2013.11.2.70

Adherence to long-term therapies, evidence for action.Geneva: WHO; 2003

Young K, Franklin P, Franklin P. Effective consulting and historytaking skills for prescribing practice. Br J Nurs. 2009; 18:(17)1056-1061 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2009.18.17.44160

Newly diagnosed hypertension: case study

Angela Brown

Trainee Advanced Nurse Practitioner, East Belfast GP Federation, Northern Ireland

View articles · Email Angela

The role of an advanced nurse practitioner encompasses the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of a range of conditions. This case study presents a patient with newly diagnosed hypertension. It demonstrates effective history taking, physical examination, differential diagnoses and the shared decision making which occurred between the patient and the professional. It is widely acknowledged that adherence to medications is poor in long-term conditions, such as hypertension, but using a concordant approach in practice can optimise patient outcomes. This case study outlines a concordant approach to consultations in clinical practice which can enhance adherence in long-term conditions.

Hypertension is a worldwide problem with substantial consequences ( Fisher and Curfman, 2018 ). It is a progressive condition ( Jamison, 2006 ) requiring lifelong management with pharmacological treatments and lifestyle adjustments. However, adopting these lifestyle changes can be notoriously difficult to implement and sustain ( Fisher and Curfman, 2018 ) and non-adherence to chronic medication regimens is extremely common ( Abegaz et al, 2017 ). This is also recognised by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2009) which estimates that between 33.3% and 50% of medications are not taken as recommended. Abegaz et al (2017) furthered this by claiming 83.7% of people with uncontrolled hypertension do not take medications as prescribed. However, leaving hypertension untreated or uncontrolled is the single largest cause of cardiovascular disease ( Fisher and Curfman, 2018 ). Therefore, better adherence to medications is associated with better outcomes ( World Health Organization, 2003 ) in terms of reducing the financial burden associated with the disease process on the health service, improving outcomes for patients ( Chakrabarti, 2014 ) and increasing job satisfaction for professionals ( McKinnon, 2013 ). Therefore, at a time when growing numbers of patients are presenting with hypertension, health professionals must adopt a concordant approach from the initial consultation to optimise adherence.

Great emphasis is placed on optimising adherence to medications ( NICE, 2009 ), but the meaning of the term ‘adherence’ is not clear and it is sometimes used interchangeably with compliance and concordance ( De Mauri et al, 2022 ), although they are not synonyms. Compliance is an outdated term alluding to paternalism, obedience and passivity from the patient ( Rae, 2021 ), whereby the patient's behaviour must conform to the health professional's recommendations. Adherence is defined as ‘the extent to which a person's behaviour, taking medication, following a diet and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider’ ( Chakrabarti, 2014 ). This term is preferred over compliance as it is less paternalistic ( Rae, 2021 ), as the patient is included in the decision-making process and has agreed to the treatment plan. While it is not yet widely embraced or used in practice ( Fawcett, 2020 ), concordance is recognised, not as a behaviour ( Rae, 2021 ) but more an approach or method which focuses on the equal partnership between patient and professional ( McKinnon, 2013 ) and enables effective and agreed treatment plans.

NICE last reviewed its guidance on medication adherence in 2019 and did not replace adherence with concordance within this. This supports the theory that adherence is an outcome of good concordance and the two are not synonyms. NICE (2009) guidelines, which are still valid, show evidence of concordant principles to maximise adherence. Integrating the theoretical principles of concordance into this case study demonstrates how the trainee advanced nurse practitioner aimed to individualise patient-centred care and improve health outcomes through optimising adherence.

Patient introduction and assessment

Jane (a pseudonym has been used to protect the patient's anonymity; Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) 2018 ), is a 45-year-old woman who had been referred to the surgery following an attendance at an emergency department. Jane had been role-playing as a patient as part of a teaching session for health professionals when it was noted that her blood pressure was significantly elevated at 170/88 mmHg. She had no other symptoms. Following an initial assessment at the emergency department, Jane was advised to contact her GP surgery for review and follow up. Nazarko (2021) recognised that it is common for individuals with high blood pressure to be asymptomatic, contributing to this being referred to as the ‘silent killer’. Hypertension is generally only detected through opportunistic checking of blood pressure, as seen in Jane's case, which is why adults over the age of 40 years are offered a blood pressure check every 5 years ( Bostock-Cox, 2013 ).

Consultation

Jane presented for a consultation at the surgery. Green (2015) advocates using a model to provide a structured approach to consultations which ensures quality and safety, and improves time management. Young et al (2009) claimed that no single consultation model is perfect, and Diamond-Fox (2021) suggested that, with experience, professionals can combine models to optimise consultation outcomes. Therefore, to effectively consult with Jane and to adapt to her individual personality, different models were intertwined to provide better person-centred care.

The Calgary–Cambridge model is the only consultation model that places emphasis on initiating the session, despite it being recognised that if a consultation gets off to a bad start this can interfere throughout ( Young et al, 2009 ). Being prepared for the consultation is key. Before Jane's consultation, the environment was checked to minimise interruptions, ensuring privacy and dignity ( Green, 2015 ; NMC, 2018 ), the seating arrangements optimised to aid good body language and communication ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ) and her records were viewed to give some background information to help set the scene and develop a rapport ( Young et al, 2009 ). Being adequately prepared builds the patient's trust and confidence in the professional ( Donnelly and Martin, 2016 ) but equally viewing patient information can lead to the professional forming preconceived ideas ( Donnelly and Martin, 2016 ). Therefore, care was taken by the trainee advanced nurse practitioner to remain open-minded.

During Jane's consultation, a thorough clinical history was taken ( Table 1 ). History taking is common to all consultation models and involves gathering important information ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ). History-taking needs to be an effective ( Bostock-Cox, 2019 ), holistic process ( Harper and Ajao, 2010 ) in order to be thorough, safe ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ) and aid in an accurate diagnosis. The key skill for taking history is listening and observing the patient ( Harper and Ajao, 2010 ). Sir William Osler said:‘listen to the patient as they are telling you the diagnosis’, but Knott and Tidy (2021) suggested that patients are barely given 20 seconds before being interrupted, after which they withdraw and do not offer any new information ( Demosthenous, 2017 ). Using this guidance, Jane was given the ‘golden minute’ allowing her to tell her ‘story’ without being interrupted ( Green, 2015 ). This not only showed respect ( Ingram, 2017 ) but interest in the patient and their concerns.

Once Jane shared her story, it was important for the trainee advanced nurse practitioner to guide the questioning ( Green 2015 ). This was achieved using a structured approach to take Jane's history, which optimised efficiency and effectiveness, and ensured that pertinent information was not omitted ( Young et al, 2009 ). Thomas and Monaghan (2014) set out clear headings for this purpose. These included:

- The presenting complaint

- Past medical history

- Drug history

- Social history

- Family history.

McPhillips et al (2021) also emphasised a need for a systemic enquiry of the other body systems to ensure nothing is missed. From taking this history it was discovered that Jane had been feeling well with no associated symptoms or red flags. A blood pressure reading showed that her blood pressure was elevated. Jane had no past medical history or allergies. She was not taking any medications, including prescribed, over the counter, herbal or recreational. Jane confirmed that she did not drink alcohol or smoke. There was no family history to note, which is important to clarify as a genetic link to hypertension could account for 30–50% of cases ( Nazarko, 2021 ). The information gathered was summarised back to Jane, showing good practice ( McPhillips et al, 2021 ), and Jane was able to clarify salient or missing points. Green (2015) suggested that optimising the patient's involvement in this way in the consultation makes her feel listened to which enhances patient satisfaction, develops a therapeutic relationship and demonstrates concordance.

During history taking it is important to explore the patient's ideas, concerns and expectations. Moulton (2007) refers to these as the ‘holy trinity’ and central to upholding person-centredness ( Matthys et al, 2009 ). Giving Jane time to discuss her ideas, concerns and expectations allowed the trainee advanced nurse practitioner to understand that she was concerned about her risk of a stroke and heart attack, and worried about the implications of hypertension on her already stressful job. Using ideas, concerns and expectations helped to understand Jane's experience, attitudes and perceptions, which ultimately will impact on her health behaviours and whether engagement in treatment options is likely ( James and Holloway, 2020 ). Establishing Jane's views demonstrated that she was eager to engage and manage her blood pressure more effectively.

Vincer and Kaufman (2017) demonstrated, through their case study, that a failure to ask their patient's viewpoint at the initial consultation meant a delay in engagement with treatment. They recognised that this delay could have been avoided with the use of additional strategies had ideas, concerns and expectations been implemented. Failure to implement ideas, concerns and expectations is also associated with reattendance or the patient seeking second opinions ( Green, 2015 ) but more positively, when ideas, concerns and expectations is implemented, it can reduce the number of prescriptions while sustaining patient satisfaction ( Matthys et al, 2009 ).

Physical examination

Once a comprehensive history was taken, a physical examination was undertaken to supplement this information ( Nuttall and Rutt-Howard, 2016 ). A physical examination of all the body systems is not required ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ) as this would be extremely time consuming, but the trainee advanced nurse practitioner needed to carefully select which systems to examine and use good examination technique to yield a correct diagnosis ( Knott and Tidy, 2021 ). With informed consent, clinical observations were recorded along with a full cardiovascular examination. The only abnormality discovered was Jane's blood pressure which was 164/90 mmHg, which could suggest stage 2 hypertension ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ). However, it is the trainee advanced nurse practitioner's role to use a hypothetico-deductive approach to arrive at a diagnosis. This requires synthesising all the information from the history taking and physical examination to formulate differential diagnoses ( Green, 2015 ) from which to confirm or refute before arriving at a final diagnosis ( Barratt, 2018 ).

Differential diagnosis

Hypertension can be triggered by secondary causes such as certain drugs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, decongestants, sodium-containing medications or combined oral contraception), foods (liquorice, alcohol or caffeine; Jamison, 2006 ), physiological response (pain, anxiety or stress) or pre-eclampsia ( Jamison, 2006 ; Schroeder, 2017 ). However, Jane had clarified that these were not contributing factors. Other potential differentials which could not be ruled out were the white-coat syndrome, renal disease or hyperthyroidism ( Schroeder, 2017 ). Further tests were required, which included bloods, urine albumin creatinine ratio, electrocardiogram and home blood pressure monitoring, to ensure a correct diagnosis and identify any target organ damage.

Joint decision making

At this point, the trainee advanced nurse practitioner needed to share their knowledge in a meaningful way to enable the patient to participate with and be involved in making decisions about their care ( Rostoft et al, 2021 ). Not all patients wish to be involved in decision making ( Hobden, 2006 ) and this must be respected ( NMC, 2018 ). However, engaging patients in partnership working improves health outcomes ( McKinnon, 2013 ). Explaining the options available requires skill so as not to make the professional seem incompetent and to ensure the patient continues to feel safe ( Rostoft et al, 2021 ).

Information supported by the NICE guidelines was shared with Jane. These guidelines advocated that in order to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, a clinic blood pressure reading of 140/90 mmHg or higher was required, with either an ambulatory or home blood pressure monitoring result of 135/85 mmHg or higher ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ). However, the results from a new retrospective study suggested that the use of home blood pressure monitoring is failing to detect ‘non-dippers’ or ‘reverse dippers’ ( Armitage et al, 2023 ). These are patients whose blood pressure fails to fall during their nighttime sleep. This places them at greater risk of cardiovascular disease and misdiagnosis if home blood pressure monitors are used, but ambulatory blood pressure monitors are less frequently used in primary care and therefore home blood pressure monitors appear to be the new norm ( Armitage et al, 2023 ).

Having discussed this with Jane she was keen to engage with home blood pressure monitoring in order to confirm the potential diagnosis, as starting a medication without a true diagnosis of hypertension could potentially cause harm ( Jamison, 2006 ). An accurate blood pressure measurement is needed to prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary therapy ( Jamison, 2006 ) and this is dependent on reliable and calibrated equipment and competency in performing the task ( Bostock-Cox, 2013 ). Therefore, Jane was given education and training to ensure the validity and reliability of her blood pressure readings.

For Jane, this consultation was the ideal time to offer health promotion advice ( Green, 2015 ) as she was particularly worried about her elevated blood pressure. Offering health promotion advice is a way of caring, showing support and empowerment ( Ingram, 2017 ). Therefore, Jane was provided with information on a healthy diet, the reduction of salt intake, weight loss, exercise and continuing to abstain from smoking and alcohol ( Williams, 2013 ). These were all modifiable factors which Jane could implement straight away to reduce her blood pressure.

Safety netting

The final stage and bringing this consultation to a close was based on the fourth stage of Neighbour's (1987) model, which is safety netting. Safety netting identifies appropriate follow up and gives details to the patient on what to do if their condition changes ( Weiss, 2019 ). It is important that the patient knows who to contact and when ( Young et al, 2009 ). Therefore, Jane was advised that, should she develop chest pains, shortness of breath, peripheral oedema, reduced urinary output, headaches, visual disturbances or retinal haemorrhages ( Schroeder, 2017 ), she should present immediately to the emergency department, otherwise she would be reviewed in the surgery in 1 week.

Jane was followed up in a second consultation 1 week later with her home blood pressure readings. The average reading from the previous 6 days was calculated ( Bostock-Cox, 2013 ) and Jane's home blood pressure reading was 158/82 mmHg. This reading ruled out white-coat syndrome as Jane's blood pressure remained elevated outside clinic conditions (white-coat syndrome is defined as a difference of more than 20/10 mmHg between clinic blood pressure readings and the average home blood pressure reading; NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ). Subsequently, Jane was diagnosed with stage 2 essential (or primary) hypertension. Stage 2 is defined as a clinic blood pressure of 160/100 mmHg or higher or a home blood pressure of 150/95 mmHg or higher ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ).

A diagnosis of hypertension can be difficult for patients as they obtain a ‘sick label’ despite feeling well ( Jamison, 2006 ). This is recognised as a deterrent for their motivation to initiate drug treatment and lifestyle changes ( Williams, 2013 ), presenting a greater challenge to health professionals, which can be addressed through concordance strategies. However, having taken Jane's bloods, electrocardiogram and urine albumin:creatinine ratio in the first consultation, it was evident that there was no target organ damage and her Qrisk3 score was calculated as 3.4%. These results provided reassurance for Jane, but she was keen to engage and prevent any potential complications.

Agreeing treatment

Concordance is only truly practised when the patient's perspectives are valued, shared and used to inform planning ( McKinnon, 2013 ). The trainee advanced nurse practitioner now needed to use the information gained from the consultations to formulate a co-produced and meaningful treatment plan based on the best available evidence ( Diamond-Fox and Bone, 2021 ). Jane understood the risk associated with high blood pressure and was keen to begin medication as soon as possible. NICE guidelines ( 2019 ; 2022 ) advocate the use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blockers in patients under 55 years of age and not of Black African or African-Caribbean origin. However, ACE inhibitors seem to be used as the first-line treatment for hypertensive patients under the age of 55 years ( O'Donovan, 2019 ).

ACE inhibitors directly affect the renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system which plays a central role in regulation of blood pressure ( Porth, 2015 ). Renin is secreted by the juxtaglomerular cells, in the kidneys' nephrons, when there is a decrease in renal perfusion and stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system ( O'Donovan, 2018 ). Renin then combines with angiotensinogen, a circulating plasma globulin from the liver, to form angiotensin I ( Kumar and Clark, 2017 ). Angiotensin I is inactive but, through ACE, an enzyme present in the endothelium of the lungs, it is transformed into angiotensin II ( Kumar and Clark, 2017 ). Angiotensin II is a vasoconstrictor which increases vascular resistance and in turn blood pressure ( Porth, 2015 ) while also stimulating the adrenal gland to produce aldosterone. Aldosterone reduces sodium excretion in the kidneys, thus increasing water reabsorption and therefore blood volume ( Porth, 2015 ). Using an ACE inhibitor prevents angiotensin II formation, which prevents vasoconstriction and stops reabsorption of sodium and water, thus reducing blood pressure.

When any new medication is being considered, providing education is key. This must include what the medication is for, the importance of taking it, any contraindications or interactions with the current medications being taken by the patient and the potential risk of adverse effects ( O'Donovan, 2018 ). Sharing this information with Jane allowed her to weigh up the pros and cons and make an informed choice leading to the creation of an individualised treatment plan.

Jamison (2006) placed great emphasis on sharing information about adverse effects, because patients with hypertension feel well before commencing medications, but taking medication has the potential to cause side effects which can affect adherence. Therefore, the range of side effects were discussed with Jane. These include a persistent, dry non-productive cough, hypotension, hypersensitivity, angioedema and renal impairment with hyperkalaemia ( Hitchings et al, 2019 ). ACE inhibitors have a range of adverse effects and most resolve when treatment is stopped ( Waterfield, 2008 ).

Following discussion with Jane, she proceeded with taking an ACE inhibitor and was encouraged to report any side effects in order to find another more suitable medication and to prevent her hypertension from going untreated. This information was provided verbally and written which is seen as good practice ( Green, 2015 ). Jane was followed up with fortnightly blood pressure recordings and urea and electrolyte checks and her dose of ramipril was increased fortnightly until her blood pressure was under 140/90 mmHg ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ).

Conclusions

Adherence to medications can be difficult to establish and maintain, especially for patients with long-term conditions. This can be particularly challenging for patients with hypertension because they are generally asymptomatic, yet acquire a sick label and start lifelong medication and lifestyle adjustments to prevent complications. Through adopting a concordant approach in practice, the outcome of adherence can be increased. This case study demonstrates how concordant strategies were implemented throughout the consultation to create a therapeutic patient–professional relationship. This optimised the creation of an individualised treatment plan which the patient engaged with and adhered to.

- Hypertension is a growing worldwide problem

- Appropriate clinical assessment, diagnosis and management is key to prevent misdiagnosis

- Long-term conditions are associated with high levels of non-adherence to treatments

- Adopting a concordance approach to practice optimises adherence and promotes positive patient outcomes

CPD reflective questions

- How has this article developed your assessment, diagnosis or management of patients presenting with a high blood pressure?

- What measures can you implement in your practice to enhance a concordant approach?

Hypertension

Learn about the nursing care management of patients with hypertension .

Table of Contents

- What is Hypertension?

Classification

Pathophysiology, epidemiology, clinical manifestations, complications, diagnostic tests, pharmacologic therapy.

- Nursing Assessment

- Diagnosis

- Nursing Care Plan and Goals

Nursing Priorities

Nursing interventions, discharge and home care guidelines, documentation guidelines, what is hypertension.

Hypertension is one of the most common lifestyle diseases to date. It affects people from all walks of life. Let us get to know hypertension more by its definitions.

- Hypertension is defined as a systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mmHg and a diastolic pressure of more than 90 mmHg .

- This is based on the average of two or more accurate blood pressure measurements during two or more consultations with the healthcare provider.

- The definition is taken from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure .

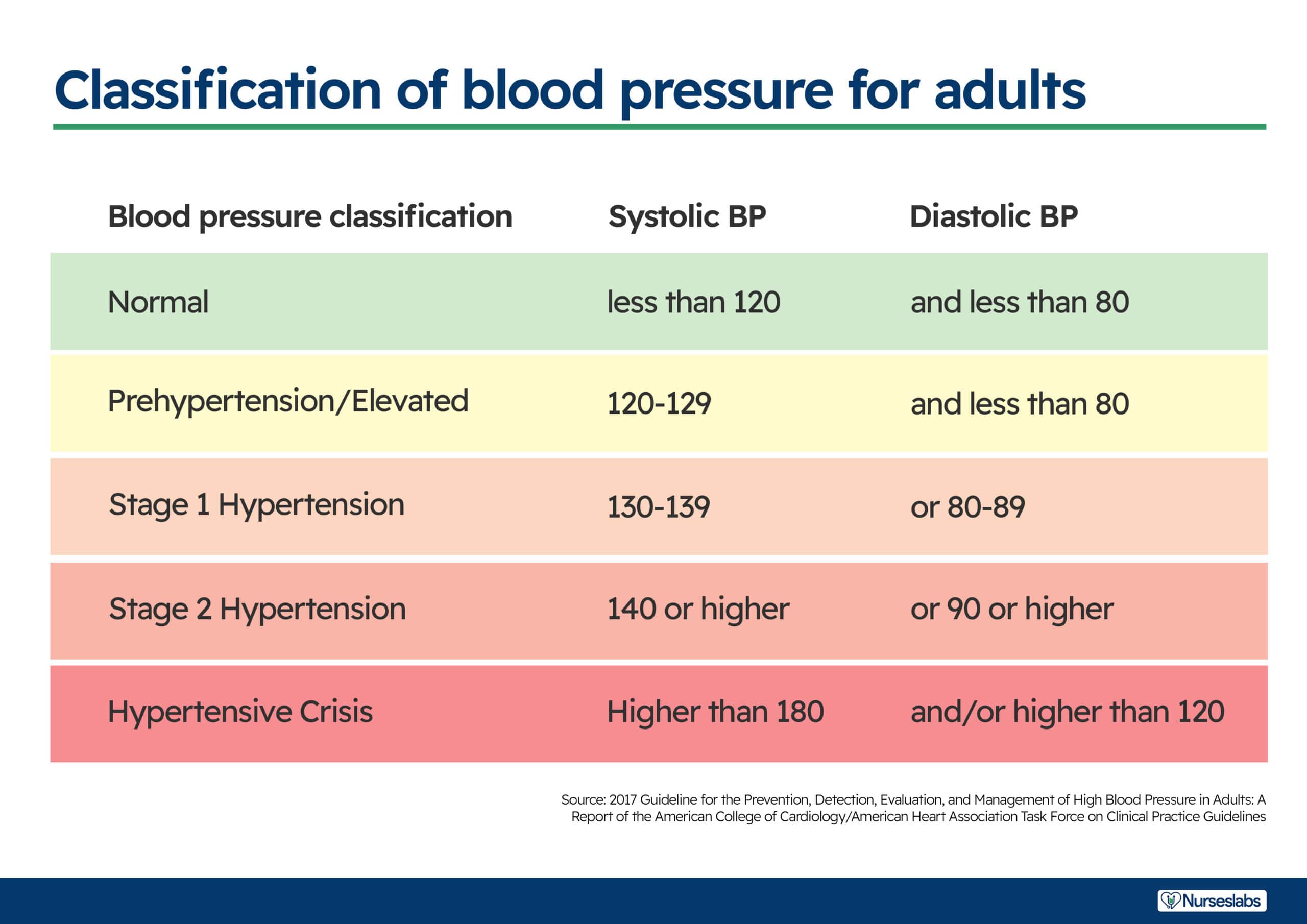

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association revised their hypertension guidelines . The previous guidelines set the threshold at 140/90 mm Hg for younger people and 150/80 mm Hg for those ages 65 and older.

- Normal . The normal range for blood pressure is between, less than 120 mmHg and less than 80 mmHg.

- Elevated . Elevated stage starts from 120 mmHg to 129 mmHg for systolic blood pressure and less than 80 mmHg for diastolic pressure.

- Stage 1 hypertension . Stage 1 starts when the patient has a systolic pressure of 130 to 139 mmHg and a diastolic pressure of 80 to 89 mmHg.

- Stage 2 hypertension . Stage 2 starts when the systolic pressure is already more than or equal than 140 mmHg and the diastolic is more than or equal than 90 mmHg.

In a normal circulation, pressure is transferred from the heart muscle to the blood each time the heart contracts and then pressure is exerted by the blood as it flows through the blood vessels.

The pathophysiology of hypertension follows.

- Hypertension is a multifactorial

- When there is excess sodium intake , renal sodium retention occurs, which increases fluid volume resulting in increased preload and increase in contractility.

- Obesity is also a factor in hypertension because hyperinsulinemia develops and structural hypertrophy results leading to increased peripheral vascular resistance.

- Genetic alteration also plays a role in the development of hypertension because when there is cell membrane alteration, functional constriction may follow and also results in increased peripheral vascular resistance.

Hypertension is slowly rising to the top as one of the primary causes of morbidity in the world . Here are the current statistics of the status of hypertension in some of the leading countries.

- About 31% of the adults in the United States have hypertension.

- African-Americans have the highest prevalence rate of 37%.

- In the total US population of persons with hypertension, 90% to 95% have primary hypertension or high blood pressure from an unidentified cause.

- The remaining 5% to 10% of this group have secondary hypertension or high blood pressure related to identified causes.

- Hypertension is also termed as the “silent killer” because 24% of people who had pressures exceeding 140/90 mmHg were unaware that their blood pressures were elevated.

Hypertension has a lot of causes just like how fever has many causes. The factors that are implicated as causes of hypertension are:

- Increased sympathetic nervous system activity . Sympathetic nervous system activity increases because there is dysfunction in the autonomic nervous system .

- Increase renal reabsorption . There is an increase reabsorption of sodium, chloride, and water which is related to a genetic variation in the pathways by which the kidneys handle sodium.

- Increased RAAS activity . The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system increases its activity leading to the expansion of extracellular fluid volume and increased systemic vascular resistance.

- Decreased vasodilation of the arterioles . The vascular endothelium is damaged because of the decrease in the vasodilation of the arterioles.

Many people who have hypertension are asymptomatic at first. Physical examination may reveal no abnormalities except for an elevated blood pressure, so one must be prepared to recognize hypertension at its earliest.

- Headache . The red blood cells carrying oxygen is having a hard time reaching the brain because of constricted vessels , causing headache.

- Dizziness occurs due to the low concentration of oxygen that reaches the brain.

- Chest pain . Chest pain occurs also due to decreased oxygen levels .

- Blurred vision. Blurred vision may occur later on because of too much constriction in the blood vessels of the eye that red blood cells carrying oxygen cannot pass through.

Prevention of hypertension mainly relies on a healthy lifestyle and self-discipline.

- Weight reduction . Maintenance of normal body weight can help prevent hypertension.

- Adopt DASH . DASH or the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension includes consummation of a diet rich in fruits, vegetable, and low-fat dairy .

- Dietary sodium retention . Sodium contributes to an elevated blood pressure, so reducing the dietary intake to no more than 2.4 g sodium per day can be really helpful.

- Physical activity . Engage in regular aerobic physical activity for 30 minutes thrice every week.

- Moderation of alcohol consumption . Limit alcohol consumption to no more than 2 drinks per day in men and one drink for women and people who are lighter in weight.

If hypertension is left untreated, it could progress to complications of the different body organs.

- Heart failure . With increased blood pressure, the heart pumps blood faster than normal until the heart muscle goes weak from too much exertion.

- Myocardial infarction . Decreased oxygen due to constriction of blood vessels may lead to MI.

- Impaired vision. Ineffective peripheral perfusion affects the eye, causing problems in vision because of decreased oxygen.

- Renal failure. Blood carrying oxygen and nutrients could not reach the renal system because of the constricted blood vessels .

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Assessment of the patient with hypertension must be detailed and thorough. There are also diagnostic tests that can be performed to establish the diagnosis of hypertension.

- Assess the patient’s health history

- Perform physical examination as appropriate.

- The retinas are examined to assess possible organ damage .

- Laboratory tests are also taken to check target organ damage .

- Urinalysis is performed to check the concentration of sodium in the urine though the specific gravity.

- Blood chemistry (e.g. analysis of sodium, potassium , creatinine , fasting glucose , and total and high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels). These tests are done to determine the level of sodium and fat in the body.

- 12-lead ECG . ECG needs to be performed to rule presence of cardiovascular damage .

- Echocardiography . Echocardiography assesses the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy .

- Creatinine clearance . Creatinine clearance is performed to check for the level of BUN and creatinine that can determine if there is renal damage or not.

- Renin level . Renin level should be assessed to determine how RAAS is coping.

- Hemoglobin/hematocrit: Not diagnostic but assesses relationship of cells to fluid volume (viscosity) and may indicate risk factors such as hypercoagulability, anemia .

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/creatinine: Provides information about renal perfusion/function.

- Glucose: Hyperglycemia ( diabetes mellitus is a precipitator of hypertension) may result from elevated catecholamine levels (increases hypertension).

- Serum potassium : Hypokalemia may indicate the presence of primary aldosteronism (cause) or be a side effect of diuretic therapy.

- Serum calcium : Imbalance may contribute to hypertension.

- Lipid panel (total lipids, high-density lipoprotein [HDL], low-density lipoprotein [LDL], cholesterol, triglycerides, phospholipids): Elevated level may indicate predisposition for/presence of atheromatous plaques.

- Thyroid studies: Hyperthyroidism may lead or contribute to vasoconstriction and hypertension.

- Serum/urine aldosterone level: May be done to assess for primary aldosteronism (cause).

- Urinalysis: May show blood, protein, or white blood cells; or glucose suggests renal dysfunction and/or presence of diabetes .

- Creatinine clearance: May be reduced, reflecting renal damage.

- Urine vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) (catecholamine metabolite): Elevation may indicate presence of pheochromocytoma (cause); 24-hour urine VMA may be done for assessment of pheochromocytoma if hypertension is intermittent.

- Uric acid: Hyperuricemia has been implicated as a risk factor for the development of hypertension.

- Renin: Elevated in renovascular and malignant hypertension, salt-wasting disorders.

- Urine steroids: Elevation may indicate hyperadrenalism, pheochromocytoma, pituitary dysfunction, Cushing’s syndrome.

- Intravenous pyelogram (IVP): May identify cause of secondary hypertension, e.g., renal parenchymal disease, renal/ureteral calculi.

- Kidney and renography nuclear scan: Evaluates renal status (TOD).

- Excretory urography: May reveal renal atrophy, indicating chronic renal disease.

- Chest x-ray : May demonstrate obstructing calcification in valve areas; deposits in and/or notching of aorta ; cardiac enlargement.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan: Assesses for cerebral tumor , CVA, or encephalopathy or to rule out pheochromocytoma.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): May demonstrate enlarged heart, strain patterns, conduction disturbances. Note: Broad, notched P wave is one of the earliest signs of hypertensive heart disease.

Medical Management

Main Topic: Antihypertensive Drugs

The goal of hypertension treatment is to prevent complications and death by achieving and maintaining arterial blood pressure at or below 130/80 mmHg.

- The medications used for treating hypertension decrease peripheral resistance , blood volume , or the strength and rate of myocardial contraction .

- For uncomplicated hypertension, the initial medications recommended are diuretics and beta blockers.

- Only low doses are given, but if blood pressure still exceeds 140/90 mmHg, the dose is increased gradually.

- Thiazide diuretics decrease blood volume , renal blood flow, and cardiac output.

- ARBs are competitive inhibitors of aldosterone binding .

- Beta blockers block the sympathetic nervous system to produce a slower heart rate and a lower blood pressure.

- ACE inhibitors inhibit the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II and lowers peripheral resistance.

Stage 1 Hypertension

- Thiazide diuretic is recommended for most and angiotensin-converting enzyme-1, aldosterone receptor blocker , beta blocker , or calcium channel blocker is considered.

Stage 2 Hypertension

- Two-drug combination is followed, usually including thiazide diuretic and angiotensin-converting enzyme-1, or beta-blocker , or calcium channel blocker.

Nursing Management

The goal of nursing management is to help achieve a normal blood pressure through independent and dependent interventions.

Nursing Assessment

Nursing assessment must involve careful monitoring of the blood pressure at frequent and routinely scheduled intervals.

- If patient is on antihypertensive medications, blood pressure is assessed to determine the effectiveness and detect changes in the blood pressure.

- Complete history should be obtained to assess for signs and symptoms that indicate target organ damage.

- Pay attention to the rate, rhythm, and character of the apical and peripheral pulses.

Based on the assessment data, nursing diagnoses may include the following:

- Deficient knowledge regarding the relation between the treatment regimen and control of the disease process.

- Noncompliance with the therapeutic regimen related to side effects of the prescribed therapy.

- Risk for activity intolerance related to imbalance between oxygen supply and demand.

- Risk- prone health behavior related to condition requiring change in lifestyle.

Nursing Care Plan and Goals

Main article: Hypertension Nursing Care Plans

The major goals for a patient with hypertension are as follows:

- Understanding of the disease process and its treatment.

- Participation in a self-care program.

- Absence of complications.

- BP within acceptable limits for individual.

- Cardiovascular and systemic complications prevented/minimized.

- Disease process/prognosis and therapeutic regimen understood.

- Necessary lifestyle/behavioral changes initiated.

- Plan in place to meet needs after discharge.

- Maintain/enhance cardiovascular functioning.

- Prevent complications.

- Provide information about disease process/prognosis and treatment regimen.

- Support active patient control of condition.

The objective of nursing care focuses on lowering and controlling the blood pressure without adverse effects and without undue cost.

- Encourage the patient to consult a dietitian to help develop a plan for improving nutrient intake or for weight loss .

- Encourage restriction of sodium and fat

- Emphasize increase intake of fruits and vegetables .

- Implement regular physical activity .

- Advise patient to limit alcohol consumption and avoidance of tobacco.

- Assist the patient to develop and adhere to an appropriate exercise regimen.

At the end of the treatment regimen, the following are expected to be achieved:

- Maintain blood pressure at less than 140/90 mmHg with lifestyle modifications, medications, or both.

- Demonstrate no symptoms of angina , palpitations, or visual changes.

- Has stable BUN and serum creatinine levels.

- Has palpable peripheral pulses.

- Adheres to the dietary regimen as prescribed.

- Exercises regularly.

- Takes medications as prescribed and reports side effects.

- Measures blood pressure routinely.

- Abstains from tobacco and alcohol intake.

- Exhibits no complications.

Following discharge, the nurse should promote self-care and independence of the patient.

- The nurse can help the patient achieve blood pressure control through education about managing blood pressure.

- Assist the patient in setting goal blood pressures .

- Provide assistance with social support.

- Encourage the involvement of family members in the education program to support the patient’s efforts to control hypertension.

- Provide written information about expected effects and side effects.

- Encourage and teach patients to measure their blood pressures at home.

- Emphasize strict compliance of follow-up check up .

These are the following data that should be documented for the patient’s record:

- Effects of behavior on health status/condition.

- Plan for adjustments and interventions for achieving the plan and the people involved.

- Client responses to the interventions, teaching, and action plan performed.

- Attainment or progress towards desired outcome.

- Modifications to plan care.

- Individual findings including deviation from prescribed treatment plan.

- Consequences of actions to date.

Posts related to Hypertension:

- Pregnancy Induced Hypertension

- 6 Hypertension Nursing Care Plans

- Antihypertensive Drugs

- Cardiovascular Care Nursing Mnemonics and Tips

6 thoughts on “Hypertension”

I want some NMC questions to solve

Question regarding Stage 1 HTN is incorrect. Stage 1 HTN is BP reading 140-159/90-99.

In new version of Brunner & Suddath’s medical surgical nursing textbook (2022), stage 1 HTN is BP reading 130-139/80-89. (pp: 866, vol 1)

I don’t understand the explanation for the classification of hypertension, the explanation is not matching with the table, why?

“Medical Management Main Topic: Antihypertensive Drugs

The goal of hypertensive treatment I to prevent complications and death by achieving and maintaining the arterial blood pressure at 40/90 mmHg or lower.”

I think need to correct the above sentence as follows;

The goal of hypertensive treatment is to prevent complications and death by achieving and maintaining the arterial blood pressure at 140/90 mmHg or lower.”

please there is a place you wrote BP 40/90,is that correct. Meanwhile, the article is educative.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

PICO: Form a Focused Clinical Question

- 1. Ask: PICO(T) Question

- 2. Align: Levels of Evidence

- 3a. Acquire: Resource Types

- 3b. Acquire: Searching

- 4. Appraise

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Case Study Example

- Practice PICO

Formulate a Clinical Question from a Case Study

- Case: Hypertension

I: Intervention

C: comparison.

- PICO: Putting It Together

Clinical Scenario

A 68-year-old female patient has recently been diagnosed with high blood pressure. She is otherwise healthy and active. You need to decide whether to prescribe her a beta-blocker or an ACE inhibiter.

Image: "Blood pressure measuring. Doctor and patient. Health care." by agilemktg1 is marked with CC PDM 1.0

► Click on the P: Patient tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

(Case study from EBM Librarian: Teaching Tools: Scenarios .)

Consider when choosing your patient/problem:

- What are the most important characteristics?

- Relevant demographic factors

- The setting

Patient: adult hypertensive female

Image: "Nurse measuring blood pressure of senior woman at home. Looking at camera, smiling.?" by agilemktg1 is marked with CC PDM 1.0

► Click on the I: Intervention tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

Consider for your intervention:

- What is the main intervention, treatment, diagnostic test, procedure, or exposure?

- Think of dosage, frequency, duration, and mode of delivery

Intervention: beta-blocker

Image: "Atenolol Blood Pressure Tablets Image 4" by Doctor4U_UK is licensed under CC BY 2.0

► Click on the C: Comparison tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

Consider for your comparison:

- Inactive control intervention: Placebo, standard care, no treatment

- Active control intervention: A different drug, dose, or kind of therapy

Comparison: ACE inhibiter

Image: "Ramipril Blood Pressure Capsules Image 5" by Doctor4U_UK is licensed under CC BY 2.0

► Click on the O: Outcome tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

Consider for your outcome:

- Be specific and make it measurable

- It can be something objective or subjective

Outcome: relief of symptoms; controlled blood pressure

Image: "File:BP B6 Connect blood pressure monitor.png" by 百略醫學 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

► Click on the PICO: Putting It Together tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

Formulate a PICO Question

Answerable PICO Question: In middle-aged adult females with hypertension, are beta blockers more effective than ACE inhibiters in controlling blood pressure?

Image: "Dagstuhl 2008-02-01 - 37" by Nic's events is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Suggested MeSH Terms: Adrenergic beta-Antagonists/therapeutic use; Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/therapeutic use; hypertension/drug therapy

Tip: Incorporating sex into the search may not be necessary unless there is a significant difference between males and females in relevant studies.

Click "Next" below to practice formulating clinical questions using PICO format.

- << Previous: Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Next: Practice PICO >>

- Last Updated: Apr 19, 2024 2:46 PM

- URL: https://med-fsu.libguides.com/pico

Maguire Medical Library Florida State University College of Medicine 1115 W. Call St., Tallahassee, FL 32306 Call 850-644-3883 (voicemail) or Text 850-724-4987 Questions? Ask us .

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Mr. E.A. is a 40-year-old black male who presented to his Primary Care Provider for a diabetes follow up on October 14th, 2019. The patient complains of a general constant headache that has lasted the past week, with no relieving factors. He also reports an unusual increase in fatigue and general muscle ache without any change in his daily routine. Patient also reports occasional numbness and tingling of face and arms. He is concerned that these symptoms could potentially be a result of his new diabetes medication that he began roughly a week ago. Patient states that he has not had any caffeine or smoked tobacco in the last thirty minutes. During assessment vital signs read BP 165/87, Temp 97.5 , RR 16, O 98%, and HR 86. E.A states he has not lost or gained any weight. After 10 mins, the vital signs were retaken BP 170/90, Temp 97.8, RR 15, O 99% and HR 82. Hg A1c 7.8%, three months prior Hg A1c was 8.0%. Glucose 180 mg/dL (fasting). FAST test done; negative for stroke. CT test, Chem 7 and CBC have been ordered.

Past medical history

Diagnosed with diabetes (type 2) at 32 years old

Overweight, BMI of 31

Had a cholecystomy at 38 years old

Diagnosed with dyslipidemia at 32 years old

Past family history

Mother alive, diagnosed diabetic at 42 years old

Father alive with Hypertension diagnosed at 55 years old

Brother alive and well at 45 years old

Sister alive and obese at 34 years old

Pertinent social history

Social drinker on occasion

Smokes a pack of cigarettes per day

Works full time as an IT technician and is in graduate school

Loading metrics

Open Access

Learning Forum

Learning Forum articles are commissioned by our educational advisors. The section provides a forum for learning about an important clinical problem that is relevant to a general medical audience.

See all article types »

A 21-Year-Old Pregnant Woman with Hypertension and Proteinuria

- Andrea Luk,

* To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected]

- Ching Wan Lam,

- Wing Hung Tam,

- Anthony W. I Lo,

- Enders K. W Ng,

- Alice P. S Kong,

- Wing Yee So,

- Chun Chung Chow

- Andrea Luk,

- Ronald C. W Ma,

- Ching Wan Lam,

- Wing Hung Tam,

- Anthony W. I Lo,

- Enders K. W Ng,

- Alice P. S Kong,

- Wing Yee So,

Published: February 24, 2009

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037

- Reader Comments

Citation: Luk A, Ma RCW, Lam CW, Tam WH, Lo AWI, Ng EKW, et al. (2009) A 21-Year-Old Pregnant Woman with Hypertension and Proteinuria. PLoS Med 6(2): e1000037. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037

Copyright: © 2009 Luk et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this article.

Competing interests: RCWM is Section Editor of the Learning Forum. The remaining authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: CT, computer tomography; I, iodine; MIBG, metaiodobenzylguanidine; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; SDHD, succinate dehydrogenase subunit D

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Description of Case

A 21-year-old pregnant woman, gravida 2 para 1, presented with hypertension and proteinuria at 20 weeks of gestation. She had a history of pre-eclampsia in her first pregnancy one year ago. During that pregnancy, at 39 weeks of gestation, she developed high blood pressure, proteinuria, and deranged liver function. She eventually delivered by emergency caesarean section following failed induction of labour. Blood pressure returned to normal post-partum and she received no further medical follow-up. Family history was remarkable for her mother's diagnosis of hypertension in her fourth decade. Her father and five siblings, including a twin sister, were healthy. She did not smoke nor drink any alcohol. She was not taking any regular medications, health products, or herbs.

At 20 weeks of gestation, blood pressure was found to be elevated at 145/100 mmHg during a routine antenatal clinic visit. Aside from a mild headache, she reported no other symptoms. On physical examination, she was tachycardic with heart rate 100 beats per minute. Body mass index was 16.9 kg/m 2 and she had no cushingoid features. Heart sounds were normal, and there were no signs suggestive of congestive heart failure. Radial-femoral pulses were congruent, and there were no audible renal bruits.

Baseline laboratory investigations showed normal renal and liver function with normal serum urate concentration. Random glucose was 3.8 mmol/l. Complete blood count revealed microcytic anaemia with haemoglobin level 8.3 g/dl (normal range 11.5–14.3 g/dl) and a slightly raised platelet count of 446 × 10 9 /l (normal range 140–380 × 10 9 /l). Iron-deficient state was subsequently confirmed. Quantitation of urine protein indicated mild proteinuria with protein:creatinine ratio of 40.6 mg/mmol (normal range <30 mg/mmol in pregnancy).

What Were Our Differential Diagnoses?

An important cause of hypertension that occurs during pregnancy is pre-eclampsia. It is a condition unique to the gravid state and is characterised by the onset of raised blood pressure and proteinuria in late pregnancy, at or after 20 weeks of gestation [ 1 ]. Pre-eclampsia may be associated with hyperuricaemia, deranged liver function, and signs of neurologic irritability such as headaches, hyper-reflexia, and seizures. In our patient, hypertension developed at a relatively early stage of pregnancy than is customarily observed in pre-eclampsia. Although she had proteinuria, it should be remembered that this could also reflect underlying renal damage due to chronic untreated hypertension. Additionally, her electrocardiogram showed left ventricular hypertrophy, which was another indicator of chronicity.

While pre-eclampsia might still be a potential cause of hypertension in our case, the possibility of pre-existing hypertension needed to be considered. Box 1 shows the differential diagnoses of chronic hypertension, including essential hypertension, primary hyperaldosteronism related to Conn's adenoma or bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing's syndrome, phaeochromocytoma, renal artery stenosis, glomerulopathy, and coarctation of the aorta.

Box 1: Causes of Hypertension in Pregnancy

- Pre-eclampsia

- Essential hypertension

- Renal artery stenosis

- Glomerulopathy

- Renal parenchyma disease

- Primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn's adenoma or bilateral adrenal hyperplasia)

- Cushing's syndrome

- Phaeochromocytoma

- Coarctation of aorta

- Obstructive sleep apnoea

Renal causes of hypertension were excluded based on normal serum creatinine and a bland urinalysis. Serology for anti-nuclear antibodies was negative. Doppler ultrasonography of renal arteries showed normal flow and no evidence of stenosis. Cushing's syndrome was unlikely as she had no clinical features indicative of hypercortisolism, such as moon face, buffalo hump, violaceous striae, thin skin, proximal muscle weakness, or hyperglycaemia. Plasma potassium concentration was normal, although normokalaemia does not rule out primary hyperaldosteronism. Progesterone has anti-mineralocorticoid effects, and increased placental production of progesterone may mask hypokalaemia. Besides, measurements of renin activity and aldosterone concentration are difficult to interpret as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis is typically stimulated in pregnancy. Phaeochromocytoma is a rare cause of hypertension in pregnancy that, if unrecognised, is associated with significant maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis can be established by measuring levels of catecholamines (noradrenaline and adrenaline) and/or their metabolites (normetanephrine and metanephrine) in plasma or urine.

What Was the Diagnosis?

Catecholamine levels in 24-hour urine collections were found to be markedly raised. Urinary noradrenaline excretion was markedly elevated at 5,659 nmol, 8,225 nmol, and 9,601 nmol/day in repeated collections at 21 weeks of gestation (normal range 63–416 nmol/day). Urinary adrenaline excretion was normal. Pregnancy may induce mild elevation of catecholamine levels, but the marked elevation of urinary catecholamine observed was diagnostic of phaeochromocytoma. Conditions that are associated with false positive results, such as acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, acute cerebrovascular event, withdrawal from alcohol, withdrawal from clonidine, and cocaine abuse, were not present in our patient.

The working diagnosis was therefore phaeochromocytoma complicating pregnancy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of neck to pelvis, without gadolinium enhancement, was performed at 24 weeks of gestation. It showed a 4.2 cm solid lesion in the mid-abdominal aorto-caval region, while both adrenals were unremarkable. There were no ectopic lesions seen in the rest of the examined areas. Based on existing investigation findings, it was concluded that she had extra-adrenal paraganglioma resulting in hypertension.

What Was the Next Step in Management?

At 22 weeks of gestation, the patient was started on phenoxybenzamine titrated to a dose of 30 mg in the morning and 10 mg in the evening. Propranolol was added several days after the commencement of phenoxybenzamine. Apart from mild postural dizziness, the medical therapy was well tolerated during the remainder of the pregnancy. In the third trimester, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were maintained to below 90 mmHg and 60 mmHg, respectively. During this period, she developed mild elevation of alkaline phosphatase ranging from 91 to 188 IU/l (reference 35–85 IU/l). However, liver transaminases were normal and the patient had no seizures. Repeated urinalysis showed resolution of proteinuria. At 38 weeks of gestation, the patient proceeded to elective caesarean section because of previous caesarean section, and a live female baby weighing 3.14 kg was delivered. The delivery was uncomplicated and blood pressure remained stable.

Following the delivery, computer tomography (CT) scan of neck, abdomen, and pelvis was performed as part of pre-operative planning to better delineate the relationship of the tumour to neighbouring structures. In addition to the previously identified extra-adrenal paraganglioma in the abdomen ( Figure 1 ), the CT revealed a 9 mm hypervascular nodule at the left carotid bifurcation, suggestive of a carotid body tumour ( Figure 2 ). The patient subsequently underwent an iodine (I) 131 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan, which demonstrated marked MIBG-avidity of the paraganglioma in the mid-abdomen. The reported left carotid body tumour, however, did not demonstrate any significant uptake. This could indicate either that the MIBG scan had poor sensitivity in detecting a small tumour, or that the carotid body tumour was not functional.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g002

In June 2008, four months after the delivery, the patient had a laparotomy with removal of the abdominal paraganglioma. The operation was uncomplicated. There was no wide fluctuation of blood pressures intra- and postoperatively. Phenoxybenzamine and propranolol were stopped after the operation. Histology of the excised tumour was consistent with paraganglioma with cells staining positive for chromogranin ( Figures 3 and 4 ) and synaptophysin. Adrenal tissues were notably absent.

The tumour is a well-circumscribed fleshy yellowish mass with maximal dimension of 5.5 cm.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g003

The tumour cells are polygonal with bland nuclei. The cells are arranged in nests and are immunoreactive to chromogranin (shown here) and synaptophysin.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g004

The patient was counselled for genetic testing for hereditary phaeochromocytoma/paraganglioma. She was found to be heterozygous for c.449_453dup mutation of the succinate dehydrogenase subunit D (SDHD) gene ( Figure 5 ). This mutation is a novel frameshift mutation, and leads to SDHD deficiency (GenBank accession number: 1162563). At the latest clinic visit in August 2008, she was asymptomatic and normotensive. Measurements of catecholamine in 24-hour urine collections had normalised. Resection of the left carotid body tumour was planned for a later date. She was to be followed up indefinitely to monitor for recurrences. She was also advised to contact family members for genetic testing. Our patient gave written consent for this case to be published.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g005

Phaeochromocytoma in Pregnancy

Hypertension during pregnancy is a frequently encountered obstetric complication that occurs in 6%–8% of pregnancies [ 2 ]. Phaeochromocytoma presenting for the first time in pregnancy is rare, and only several hundred cases have been reported in the English literature. In a recent review of 41 cases that presented during 1988 to 1997, maternal mortality was 4% while the rate of foetal loss was 11% [ 3 ]. Antenatal diagnosis was associated with substantial reduction in maternal mortality but had little impact on foetal mortality. Further, chronic hypertension, regardless of aetiology, increases the risk of pre-eclampsia by 10-fold [ 1 ].

Classically, patients with phaeochromocytoma present with spells of palpitation, headaches, and diaphoresis [ 4 ]. Hypertension may be sustained or sporadic, and is associated with orthostatic blood pressure drop because of hypovolaemia and impaired vasoconstricting response to posture change. During pregnancy, catecholamine surge may be triggered by pressure from the enlarging uterus and foetal movements. In the majority of cases, catecholamine-secreting tumours develop in the adrenal medulla and are termed phaeochromocytoma. Ten percent of tumours arise from extra-adrenal chromaffin tissues located in the abdomen, pelvis, or thorax to form paraganglioma that may or may not be biochemically active. The malignant potential of phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma cannot be determined from histology and is inferred by finding tumours in areas of the body not known to contain chromaffin tissues. The risk of malignancy is higher in extra-adrenal tumours and in tumours that secrete dopamine.

Making the Correct Diagnosis

The diagnosis of phaeochromocytoma requires a combination of biochemical and anatomical confirmation. Catecholamines and their metabolites, metanephrines, can be easily measured in urine or plasma samples. Day collection of urinary fractionated metanephrine is considered the most sensitive in detecting phaeochromocytoma [ 5 ]. In contrast to sporadic release of catecholamine, secretion of metanephrine is continuous and is less subjective to momentary stress. Localisation of tumour can be accomplished by either CT or MRI of the abdomen [ 6 ]. Sensitivities are comparable, although MRI is preferable in pregnancy because of minimal radiation exposure. Once a tumour is identified, nuclear medicine imaging should be performed to determine its activity, as well as to search for extra-adrenal diseases. I 131 or I 123 MIBG scan is the imaging modality of choice. Metaiodobenzylguanidine structurally resembles noradrenaline and is concentrated in chromaffin cells of phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma that express noradrenaline transporters. Radionucleotide imaging is contraindicated in pregnancy and should be deferred until after the delivery.

Treatment Approach

Upon confirming the diagnosis, medical therapy should be initiated promptly to block the cardiovascular effects of catecholamine release. Phenoxybenzamine is a long-acting non-selective alpha-blocker commonly used in phaeochromocytoma to control blood pressure and prevent cardiovascular complications [ 7 ]. The main side-effects of phenoxybenzamine are postural hypotension and reflex tachycardia. The latter can be circumvented by the addition of a beta-blocker. It is important to note that beta-blockers should not be used in isolation, since blockade of ß2-adrenoceptors, which have a vasodilatory effect, can cause unopposed vasoconstriction by a1-adrenoceptor stimulation and precipitate severe hypertension. There is little data on the safety of use of phenoxybenzamine in pregnancy, although its use is deemed necessary and probably life-saving in this precarious situation.

The definitive treatment of phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma is surgical excision. The timing of surgery is critical, and the decision must take into consideration risks to the foetus, technical difficulty regarding access to the tumour in the presence of a gravid uterus, and whether the patient's symptoms can be satisfactorily controlled with medical therapy [ 8 , 9 ]. It has been suggested that surgical resection is reasonable if the diagnosis is confirmed and the tumour identified before 24 weeks of gestation. Otherwise, it may be preferable to allow the pregnancy to progress under adequate alpha- and beta-blockade until foetal maturity is reached. Unprepared delivery is associated with a high risk of phaeochromocytoma crisis, characterised by labile blood pressure, tachycardia, fever, myocardial ischaemia, congestive heart failure, and intracerebral bleeding.

Patients with phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma should be followed up for life. The rate of recurrence is estimated to be 2%–4% at five years [ 10 ]. Assessment for recurrent disease can be accomplished by periodic blood pressure monitoring and 24-hour urine catecholamine and/or metanephrine measurements.

Genetics of Phaeochromocytoma

Approximately one quarter of patients presenting with phaeochromocytoma may carry germline mutations, even in the absence of apparent family history [ 11 ]. The common syndromes of hereditary phaeochromocytoma/paraganglioma are listed in Box 2 . These include Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, neurofibromatosis type 1, and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) gene mutations. Our patient has a novel frameshift mutation in the SDHD gene located at Chromosome 11q. SDH is a mitochondrial enzyme that is involved in oxidative phosphorylation. Characteristically, SDHD mutation is associated with head or neck non-functional paraganglioma, and infrequently, sympathetic paraganglioma or phaeochromocytoma [ 12 ]. Tumours associated with SDHD mutation are rarely malignant, in contrast to those arisen from mutation of the SDHB gene. Like all other syndromes of hereditary phaeochromocytoma, SDHD mutation is transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion. However, not all carriers of the SDHD mutation develop tumours, and inheritance is further complicated by maternal imprinting in gene expression. While it may not be practical to screen for genetic alterations in all cases of phaeochromocytoma, most authorities advocate genetic screening for patients with positive family history, young age of tumour onset, co-existence with other neoplasms, bilateral phaeochromocytoma, and extra-adrenal paraganglioma. The confirmation of genetic mutation should prompt evaluation of other family members.

Box 2: Hereditary Phaeochromocytoma/Paraganglioma Syndromes

- Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and type 2B

- Neurofibromatosis type 1

- Mutation of SDHB , SDHC , SDHD

- Ataxia-telangiectasia

- Tuberous sclerosis

- Sturge-Weber syndrome

Key Learning Points

- Hypertension complicating pregnancy is a commonly encountered medical condition.

- Pre-existing chronic hypertension must be considered in patients with hypertension presenting in pregnancy, particularly if elevation of blood pressure is detected early during pregnancy or if persists post-partum.

- Secondary causes of chronic hypertension include renal artery stenosis, renal parenchyma disease, primary hyperaldosteronism, phaeochromocytoma, Cushing's syndrome, coarctation of the aorta, and obstructive sleep apnoea.

- Phaeochromocytoma presenting during pregnancy is rare but carries high rates of maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality if unrecognised.

- Successful outcomes depend on early disease identification, prompt initiation of alpha- and beta-blockers, carefully planned delivery, and timely resection of the tumour.

Phaeochromocytoma complicating pregnancy is uncommon. Nonetheless, in view of the potential for catastrophic consequences if unrecognised, a high index of suspicion and careful evaluation for secondary causes of hypertension is of utmost importance. Blood pressure should be monitored in the post-partum period and persistence of hypertension must be thoroughly investigated.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the management of the patient or writing of the article. AL and RCWM wrote the article, with contributions from all the authors.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Graphical Abstracts and Tidbit

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About American Journal of Hypertension

- Editorial Board

- Board of Directors

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- AJH Summer School

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Clinical management and treatment decisions, hypertension in black americans, pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in black americans.

- < Previous

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Suzanne Oparil, Case study, American Journal of Hypertension , Volume 11, Issue S8, November 1998, Pages 192S–194S, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(98)00195-2

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Ms. C is a 42-year-old black American woman with a 7-year history of hypertension first diagnosed during her last pregnancy. Her family history is positive for hypertension, with her mother dying at 56 years of age from hypertension-related cardiovascular disease (CVD). In addition, both her maternal and paternal grandparents had CVD.

At physician visit one, Ms. C presented with complaints of headache and general weakness. She reported that she has been taking many medications for her hypertension in the past, but stopped taking them because of the side effects. She could not recall the names of the medications. Currently she is taking 100 mg/day atenolol and 12.5 mg/day hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), which she admits to taking irregularly because “... they bother me, and I forget to renew my prescription.” Despite this antihypertensive regimen, her blood pressure remains elevated, ranging from 150 to 155/110 to 114 mm Hg. In addition, Ms. C admits that she has found it difficult to exercise, stop smoking, and change her eating habits. Findings from a complete history and physical assessment are unremarkable except for the presence of moderate obesity (5 ft 6 in., 150 lbs), minimal retinopathy, and a 25-year history of smoking approximately one pack of cigarettes per day. Initial laboratory data revealed serum sodium 138 mEq/L (135 to 147 mEq/L); potassium 3.4 mEq/L (3.5 to 5 mEq/L); blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 19 mg/dL (10 to 20 mg/dL); creatinine 0.9 mg/dL (0.35 to 0.93 mg/dL); calcium 9.8 mg/dL (8.8 to 10 mg/dL); total cholesterol 268 mg/dL (< 245 mg/dL); triglycerides 230 mg/dL (< 160 mg/dL); and fasting glucose 105 mg/dL (70 to 110 mg/dL). The patient refused a 24-h urine test.

Taking into account the past history of compliance irregularities and the need to take immediate action to lower this patient’s blood pressure, Ms. C’s pharmacologic regimen was changed to a trial of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril, 5 mg/day; her HCTZ was discontinued. In addition, recommendations for smoking cessation, weight reduction, and diet modification were reviewed as recommended by the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI). 1

After a 3-month trial of this treatment plan with escalation of the enalapril dose to 20 mg/day, the patient’s blood pressure remained uncontrolled. The patient’s medical status was reviewed, without notation of significant changes, and her antihypertensive therapy was modified. The ACE inhibitor was discontinued, and the patient was started on the angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) losartan, 50 mg/day.

After 2 months of therapy with the ARB the patient experienced a modest, yet encouraging, reduction in blood pressure (140/100 mm Hg). Serum electrolyte laboratory values were within normal limits, and the physical assessment remained unchanged. The treatment plan was to continue the ARB and reevaluate the patient in 1 month. At that time, if blood pressure control remained marginal, low-dose HCTZ (12.5 mg/day) was to be added to the regimen.

Hypertension remains a significant health problem in the United States (US) despite recent advances in antihypertensive therapy. The role of hypertension as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is well established. 2–7 The age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension in non-Hispanic black Americans is approximately 40% higher than in non-Hispanic whites. 8 Black Americans have an earlier onset of hypertension and greater incidence of stage 3 hypertension than whites, thereby raising the risk for hypertension-related target organ damage. 1 , 8 For example, hypertensive black Americans have a 320% greater incidence of hypertension-related end-stage renal disease (ESRD), 80% higher stroke mortality rate, and 50% higher CVD mortality rate, compared with that of the general population. 1 , 9 In addition, aging is associated with increases in the prevalence and severity of hypertension. 8

Research findings suggest that risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke, particularly the role of blood pressure, may be different for black American and white individuals. 10–12 Some studies indicate that effective treatment of hypertension in black Americans results in a decrease in the incidence of CVD to a level that is similar to that of nonblack American hypertensives. 13 , 14

Data also reveal differences between black American and white individuals in responsiveness to antihypertensive therapy. For instance, studies have shown that diuretics 15 , 16 and the calcium channel blocker diltiazem 16 , 17 are effective in lowering blood pressure in black American patients, whereas β-adrenergic receptor blockers and ACE inhibitors appear less effective. 15 , 16 In addition, recent studies indicate that ARB may also be effective in this patient population.