Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 26 April 2024

The development of human causal learning and reasoning

- Mariel K. Goddu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4969-7948 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Alison Gopnik 4 , 5

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 3 , pages 319–339 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1131 Accesses

165 Altmetric

Metrics details

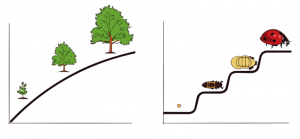

- Human behaviour

Causal understanding is a defining characteristic of human cognition. Like many animals, human children learn to control their bodily movements and act effectively in the environment. Like a smaller subset of animals, children intervene: they learn to change the environment in targeted ways. Unlike other animals, children grow into adults with the causal reasoning skills to develop abstract theories, invent sophisticated technologies and imagine alternate pasts, distant futures and fictional worlds. In this Review, we explore the development of human-unique causal learning and reasoning from evolutionary and ontogenetic perspectives. We frame our discussion using an ‘interventionist’ approach. First, we situate causal understanding in relation to cognitive abilities shared with non-human animals. We argue that human causal understanding is distinguished by its depersonalized (objective) and decontextualized (general) representations. Using this framework, we next review empirical findings on early human causal learning and reasoning and consider the naturalistic contexts that support its development. Then we explore connections to related abilities. We conclude with suggestions for ongoing collaboration between developmental, cross-cultural, computational, neural and evolutionary approaches to causal understanding.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$59.00 per year

only $4.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The rational use of causal inference to guide reinforcement learning strengthens with age

Causation in neuroscience: keeping mechanism meaningful

Causal reductionism and causal structures

Prüfer, K. et al. The bonobo genome compared with the chimpanzee and human genomes. Nature 486 , 527–531 (2012).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gopnik, A. & Wellman, H. M. Reconstructing constructivism: causal models, Bayesian learning mechanisms, and the theory theory. Psychol. Bull. 138 , 1085–1108 (2012). This paper provides an introduction to the interventionist approach formalized in terms of causal Bayes nets.

Gopnik, A. & Schulz, L. (eds.) Causal Learning: Psychology, Philosophy and Computation (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007). This edited volume provides an interdisciplinary overview of the interventionist approach.

Pearl, J. Causality (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009).

Penn, D. C. & Povinelli, D. J. Causal cognition in human and nonhuman animals: a comparative, critical review. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58 , 97–118 (2007).

PubMed Google Scholar

Schölkopf, B. et al. Toward causal representation learning. Proc. IEEE 109 , 612–634 (2021).

Google Scholar

Spirtes, P., Glymour, C. & Scheines, R. in Causation, Prediction, and Search Lecture Notes in Statistics Vol 81, 103–162 (Springer, 1993).

Gopnik, A. et al. A theory of causal learning in children: causal maps and Bayes nets. Psychol. Rev. 111 , 3–32 (2004). This seminal paper reviews the causal Bayes nets approach to causal reasoning and suggests that children construct mental models that help them understand and predict causal relations.

Pearl, J. & Mackenzie, D. The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect (Basic Books, 2018). This book provides a high-level overview of approaches to causal inference from theoretical computer science for a general audience.

Lombrozo, T. & Vasil, N. in Oxford Handbook of Causal Reasoning (ed. Waldmann, M.) 415–432 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

Woodward, J. Making Things Happen: A Theory of Causal Explanation (Oxford Univ. Press, 2005). This book outlines the ‘interventionist’ approach to causation and causal explanation in philosophy.

Shanks, D. R. & Dickinson, A. Associative accounts of causality judgment. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 21 , 229–261 (Elsevier, 1988).

Carey, S. The Origin of Concepts (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009).

Michotte, A. The Perception of Causality (Routledge, 2017).

Leslie, A. M. The perception of causality in infants. Perception 11 , 173–186 (1982). This canonical study shows that 4.5-month-old and 8-month-old infants are sensitive to spatiotemporal event configurations and contingencies that adults also construe as causal.

Leslie, A. M. Spatiotemporal continuity and the perception of causality in infants. Perception 13 , 287–305 (1984).

Danks, D. Unifying the Mind: Cognitive Representations as Graphical Models (MIT Press, 2014).

Godfrey‐Smith, P. in The Oxford Handbook of Causation (eds Beebee, H., Hitchcock, C. & Menzies, P.) 326–338 (Oxford Academic, 2009).

Gweon, H. & Schulz, L. 16-month-olds rationally infer causes of failed actions. Science 332 , 1524–1524 (2011).

Woodward, J. Causation with a Human Face: Normative Theory and Descriptive Psychology (Oxford Univ. Press, 2021). This book integrates philosophical and psychological literatures on causal reasoning to provide both normative and descriptive accounts of causal reasoning.

Rozenblit, L. & Keil, F. The misunderstood limits of folk science: an illusion of explanatory depth. Cogn. Sci . 26 , 521–562 (2002).

Ismael, J. How Physics Makes us Free (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Woodward, J. in Causal Learning: Psychology, Philosophy, and Computation (eds Gopnik, A. & Schulz, L.) Oxford Series in Cognitive Development 19–36 (Oxford Academic, 2007).

Godfrey-Smith, P. Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016).

Körding, K. P. et al. Causal inference in multisensory perception. PLoS One 2 , e943 (2007).

Wei, K. & Körding, K. P. in Sensory Cue Integration (eds Trommershäuser, J., Kording, K. & Landy, M. S.) Computational Neuroscience Series 30–45 (Oxford Academic, 2011).

Haith, A. M. & Krakauer, J. W. in Progress in Motor Control: Neural, Computational and Dynamic Approaches (eds Richardson, M. J., Riley, M. A. & Shockley, K.) 1–21 (Springer, 2013).

Krakauer, J. W. & Mazzoni, P. Human sensorimotor learning: adaptation, skill, and beyond. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21 , 636–644 (2011).

Adolph, K. E. An ecological approach to learning in (not and) development. Hum. Dev. 63 , 180–201 (2020).

Adolph, K. E., Hoch, J. E. & Ossmy, O. in Perception as Information Detection (eds Wagman, J. B. & Blau, J. J. C.) 222–236 (Routledge, 2019).

Riesen, A. H. The development of visual perception in man and chimpanzee. Science 106 , 107–108 (1947).

Spelke, E. S. What Babies Know: Core Knowledge and Composition Vol. 1 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2022).

Pearce, J. M. & Bouton, M. E. Theories of associative learning in animals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52 , 111–139 (2001).

Wasserman, E. A. & Miller, R. R. What’s elementary about associative learning? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 48 , 573–607 (1997).

Sutton, R. S. & Barto, A. G. Reinforcement learning: an introduction. Robotica 17 , 229–235 (1999).

Gershman, S. J., Markman, A. B. & Otto, A. R. Retrospective revaluation in sequential decision making: a tale of two systems. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143 , 182–194 (2014).

Gershman, S. J. Reinforcement learning and causal models. In Oxford Handbook of Causal Reasoning (ed. Waldmann, M.) 295 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

Taylor, A. H. et al. Of babies and birds: complex tool behaviours are not sufficient for the evolution of the ability to create a novel causal intervention. Proc. R. Soc. B 281 , 20140837 (2014). This study shows that complex tool use does not entail the ability to understand and create novel causal interventions: crows do not learn causal interventions from observing the effects of their own accidental behaviours.

Povinelli, D. J. & Penn, D. C. in Tool Use and Causal Cognition (eds McCormack, T., Hoerl, C. & Butterfill, S.) 69–88 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

Povinelli, D. J. & Henley, T. More rope tricks reveal why more task variants will never lead to strong inferences about higher-order causal reasoning in chimpanzees. Anim. Behav. Cogn. 7 , 392–418 (2020).

Tomasello, M. & Call, J. Primate Cognition (Oxford Univ. Press, 1997).

Visalberghi, E. & Tomasello, M. Primate causal understanding in the physical and psychological domains. Behav. Process. 42 , 189–203 (1998).

Völter, C. J., Sentís, I. & Call, J. Great apes and children infer causal relations from patterns of variation and covariation. Cognition 155 , 30–43 (2016).

Tennie, C., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. Untrained chimpanzees ( Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii ) fail to imitate novel actions. Plos One 7 , e41548 (2012).

Whiten, A., Horner, V., Litchfield, C. A. & Marshall-Pescini, S. How do apes ape? Anim. Learn. Behav. 32 , 36–52 (2004).

Moore, R. Imitation and conventional communication. Biol. Phil. 28 , 481–500 (2013).

Meltzoff, A. N. & Marshall, P. J. Human infant imitation as a social survival circuit. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 24 , 130–136 (2018).

Boesch, C. & Boesch, H. Optimisation of nut-cracking with natural hammers by wild chimpanzees. Behaviour 83 , 265–286 (1983).

Chappell, J. & Kacelnik, A. Tool selectivity in a non-primate, the New Caledonian crow ( Corvus moneduloides ). Anim. Cogn. 5 , 71–78 (2002).

Weir, A. A., Chappell, J. & Kacelnik, A. Shaping of hooks in New Caledonian crows. Science 297 , 981–981 (2002).

Wimpenny, J. H., Weir, A. A., Clayton, L., Rutz, C. & Kacelnik, A. Cognitive processes associated with sequential tool use in New Caledonian crows. PLoS One 4 , e6471 (2009).

Manrique, H. M., Gross, A. N.-M. & Call, J. Great apes select tools on the basis of their rigidity. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 36 , 409–422 (2010).

Mulcahy, N. J., Call, J. & Dunbar, R. I. Gorillas ( Gorilla gorilla ) and orangutans ( Pongo pygmaeus ) encode relevant problem features in a tool-using task. J. Comp. Psychol. 119 , 23–32 (2005).

Sanz, C., Call, J. & Morgan, D. Design complexity in termite-fishing tools of chimpanzees ( Pan troglodytes ). Biol. Lett. 5 , 293–296 (2009).

Visalberghi, E. et al. Selection of effective stone tools by wild bearded capuchin monkeys. Curr. Biol. 19 , 213–217 (2009).

Seed, A., Hanus, D. & Call, J. in Tool Use and Causal Cognition (eds McCormack, T., Hoerl, C. & Butterfill, S.) 89–110 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

Völter, C. J. & Call, J. in APA Handbook of Comparative Psychology: Perception, Learning, and Cognition (eds Call, J. et al.) 643–671 (American Psychological Association, 2017). This chapter provides a comprehensive overview of causal and inferential reasoning in non-human animals, highlighting (1) the difference between prediction versus causal knowledge and (2) the organization of non-human animals’ knowledge (stimulus- and/or context-specific versus general and structured).

Völter, C. J., Lambert, M. L. & Huber, L. Do nonhumans seek explanations? Anim. Behav. Cogn. 7 , 445–451 (2020).

Call, J. Inferences about the location of food in the great apes ( Pan paniscus , Pan troglodytes , Gorilla gorilla , and Pongo pygmaeus ). J. Comp. Psychol. 118 , 232–241 (2004).

Call, J. Apes know that hidden objects can affect the orientation of other objects. Cognition 105 , 1–25 (2007).

Hanus, D. & Call, J. Chimpanzees infer the location of a reward on the basis of the effect of its weight. Curr. Biol. 18 , R370–R372 (2008).

Hanus, D. & Call, J. Chimpanzee problem-solving: contrasting the use of causal and arbitrary cues. Anim. Cogn. 14 , 871–878 (2011).

Petit, O. et al. Inferences about food location in three cercopithecine species: an insight into the socioecological cognition of primates. Anim. Cogn. 18 , 821–830 (2015).

Heimbauer, L. A., Antworth, R. L. & Owren, M. J. Capuchin monkeys ( Cebus apella ) use positive, but not negative, auditory cues to infer food location. Anim. Cogn. 15 , 45–55 (2012).

Schloegl, C., Schmidt, J., Boeckle, M., Weiß, B. M. & Kotrschal, K. Grey parrots use inferential reasoning based on acoustic cues alone. Proc. R. Soc. B 279 , 4135–4142 (2012).

Schloegl, C., Waldmann, M. R. & Fischer, J. Understanding of and reasoning about object–object relationships in long-tailed macaques? Anim. Cogn. 16 , 493–507 (2013).

Schmitt, V., Pankau, B. & Fischer, J. Old world monkeys compare to apes in the primate cognition test battery. PLoS One 7 , e32024 (2012).

Völter, C. J. & Call, J. Great apes ( Pan paniscus , Pan troglodytes , Gorilla gorilla , Pongo abelii ) follow visual trails to locate hidden food. J. Comp. Psychol. 128 , 199–208 (2014).

Blaisdell, A. P., Sawa, K., Leising, K. J. & Waldmann, M. R. Causal reasoning in rats. Science 311 , 1020–1022 (2006).

Leising, K. J., Wong, J., Waldmann, M. R. & Blaisdell, A. P. The special status of actions in causal reasoning in rats. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 137 , 514–527 (2008).

Flavell, J. H. The Developmental Psychology Of Jean Piaget (Van Nostrand, 1963).

Piaget, J. The Construction of Reality in the Child (Routledge, 2013).

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J. & Norenzayan, A. Most people are not WEIRD. Nature 466 , 29–29 (2010).

Ayzenberg, V. & Behrmann, M. Development of visual object recognition. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 3 , 73–90 (2023).

Bronson, G. W. Changes in infants’ visual scanning across the 2- to 14-week age period. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 49 , 101–125 (1990).

Aslin, R. Ν. in Eye Movements . Cognition and Visual Perception (eds Fisher, D. F., Monty, R. A. & Senders, J. W.) 31–51 (Routledge, 2017).

Miranda, S. B. Visual abilities and pattern preferences of premature infants and full-term neonates. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 10 , 189–205 (1970).

Haith, M. M., Hazan, C. & Goodman, G. S. Expectation and anticipation of dynamic visual events by 3.5-month-old babies. Child Dev. 59 , 467–479 (1988).

Harris, P. & MacFarlane, A. The growth of the effective visual field from birth to seven weeks. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 18 , 340–348 (1974).

Cohen, L. B. & Amsel, G. Precursors to infants’ perception of the causality of a simple event. Infant. Behav. Dev. 21 , 713–731 (1998).

Leslie, A. M. & Keeble, S. Do six-month-old infants perceive causality? Cognition 25 , 265–288 (1987).

Oakes, L. M. & Cohen, L. B. Infant perception of a causal event. Cogn. Dev. 5 , 193–207 (1990). This canonical study shows that 10-month-olds, but not 6-month-olds, discriminate between causal versus non-causal events.

Kotovsky, L. & Baillargeon, R. Calibration-based reasoning about collision events in 11-month-old infants. Cognition 51 , 107–129 (1994).

Kominsky, J. F. et al. Categories and constraints in causal perception. Psychol. Sci. 28 , 1649–1662 (2017).

Spelke, E. S., Breinlinger, K., Macomber, J. & Jacobson, K. Origins of knowledge. Psychol. Rev. 99 , 605 (1992).

Baillargeon, R. in Language, Brain, and Cognitive Development: Essays in Honor of Jacques Mehler (ed. Dupoux, E.) 341–361 (MIT Press, 2001).

Hespos, S. J. & Baillargeon, R. Infants’ knowledge about occlusion and containment events: a surprising discrepancy. Psychol. Sci. 12 , 141–147 (2001).

Spelke, E. S. Principles of object perception. Cogn. Sci. 14 , 29–56 (1990).

Sobel, D. M. & Kirkham, N. Z. Blickets and babies: the development of causal reasoning in toddlers and infants. Dev. Psychol. 42 , 1103–1115 (2006).

Sobel, D. M. & Kirkham, N. Z. Bayes nets and babies: infants’ developing statistical reasoning abilities and their representation of causal knowledge. Dev. Sci. 10 , 298–306 (2007).

Bell, S. M. & Ainsworth, M. D. S. Infant crying and maternal responsiveness. Child Dev . 43 , 1171–1190 (1972).

Jordan, G. J., Arbeau, K., McFarland, D., Ireland, K. & Richardson, A. Elimination communication contributes to a reduction in unexplained infant crying. Med. Hypotheses 142 , 109811 (2020).

Nakayama, H. Emergence of amae crying in early infancy as a possible social communication tool between infants and mothers. Infant. Behav. Dev. 40 , 122–130 (2015).

Meltzoff, A. N. & Moore, M. K. in The Body and the Self (eds Bermúdez, J. L., Marcel, A. J. & Eilan, N.) 3–69 (MIT Press, 1995).

Rovee, C. K. & Rovee, D. T. Conjugate reinforcement of infant exploratory behavior. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 8 , 33–39 (1969).

Hillman, D. & Bruner, J. S. Infant sucking in response to variations in schedules of feeding reinforcement. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 13 , 240–247 (1972).

DeCasper, A. J. & Spence, M. J. Prenatal maternal speech influences newborns’ perception of speech sounds. Infant. Behav. Dev. 9 , 133–150 (1986).

Watson, J. S. & Ramey, C. T. Reactions to response-contingent stimulation in early infancy. Merrill-Palmer Q. Behav. Dev. 18 , 219–227 (1972).

Rovee-Collier, C. in Handbook of Infant Development 2nd edn (ed. Osofsky, J. D.) 98–148 (John Wiley & Sons, 1987).

Twitchell, T. E. The automatic grasping responses of infants. Neuropsychologia 3 , 247–259 (1965).

Wallace, P. S. & Whishaw, I. Q. Independent digit movements and precision grip patterns in 1–5-month-old human infants: hand-babbling, including vacuous then self-directed hand and digit movements, precedes targeted reaching. Neuropsychologia 41 , 1912–1918 (2003).

Von Hofsten, C. Mastering reaching and grasping: the development of manual skills in infancy. Adv. Psychol . 61 , 223–258 (1989).

Witherington, D. C. The development of prospective grasping control between 5 and 7 months: a longitudinal study. Infancy 7 , 143–161 (2005).

Needham, A., Barrett, T. & Peterman, K. A pick-me-up for infants’ exploratory skills: early simulated experiences reaching for objects using ‘sticky mittens’ enhances young infants’ object exploration skills. Infant. Behav. Dev. 25 , 279–295 (2002).

van den Berg, L. & Gredebäck, G. The sticky mittens paradigm: a critical appraisal of current results and explanations. Dev. Sci. 24 , e13036 (2021).

Keen, R. The development of problem solving in young children: a critical cognitive skill. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62 , 1–21 (2011). This paper provides an overview of the developmental trajectory of ‘problem-solving’skills in young children, integrating findings from perception and motor development studies with cognitive problem-solving studies.

Claxton, L. J., McCarty, M. E. & Keen, R. Self-directed action affects planning in tool-use tasks with toddlers. Infant. Behav. Dev. 32 , 230–233 (2009).

McCarty, M. E., Clifton, R. K. & Collard, R. R. The beginnings of tool use by infants and toddlers. Infancy 2 , 233–256 (2001).

Gopnik, A. & Meltzoff, A. N. Semantic and cognitive development in 15- to 21-month-old children. J. Child. Lang. 11 , 495–513 (1984).

Gopnik, A. & Meltzoff, A. N. in The Development of Word Meaning: Progress in Cognitive Development Research (eds Kuczaj, S. A. & Barrett, M. D.) 199–223 (Springer, 1986).

Gopnik, A. & Meltzoff, A. N. Words, Thoughts, and Theories (Mit Press, 1997).

Tomasello, M. in Early Social Cognition: Understanding Others in the First Months of Life (ed. Rochat, P.) 301–314 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1999).

Tomasello, M. & Farrar, M. J. Joint attention and early language. Child Dev . 57 , 1454–1463 (1986).

Gopnik, A. Words and plans: early language and the development of intelligent action. J. Child. Lang. 9 , 303–318 (1982). This paper proposes that language acquisition tracks with conceptual developments in infants’ and toddlers’ abilities in goal-directed action and planning.

Meltzoff, A. N. Infant imitation and memory: nine-month-olds in immediate and deferred tests. Child. Dev. 59 , 217–225 (1988).

Meltzoff, A. N. Infant imitation after a 1-week delay: long-term memory for novel acts and multiple stimuli. Dev. Psychol. 24 , 470–476 (1988).

Gergely, G., Bekkering, H. & Király, I. Rational imitation in preverbal infants. Nature 415 , 755–755 (2002).

Meltzoff, A. N., Waismeyer, A. & Gopnik, A. Learning about causes from people: observational causal learning in 24-month-old infants. Dev. Psychol. 48 , 1215–1228 (2012). This study demonstrates that 2-year-old and 3-year-old children learn novel causal relations from observing other agents’ interventions (observational causal learning).

Waismeyer, A., Meltzoff, A. N. & Gopnik, A. Causal learning from probabilistic events in 24‐month‐olds: an action measure. Dev. Sci. 18 , 175–182 (2015).

Stahl, A. E. & Feigenson, L. Observing the unexpected enhances infants’ learning and exploration. Science 348 , 91–94 (2015). This study demonstrates that 11-month-old children pay special visual and exploratory attention to objects that appear to violate the laws of physics as the result of an agent’s intervention.

Perfors, A., Tenenbaum, J. B., Griffiths, T. L. & Xu, F. A tutorial introduction to Bayesian models of cognitive development. Cognition 120 , 302–321 (2011).

Gopnik, A. & Bonawitz, E. Bayesian models of child development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cognit. Sci. 6 , 75–86 (2015). This paper is a technical introduction and tutorial in the Bayesian framework.

Gopnik, A., Sobel, D. M., Schulz, L. E. & Glymour, C. Causal learning mechanisms in very young children: two-, three-, and four-year-olds infer causal relations from patterns of variation and covariation. Dev. Psychol. 37 , 620–629 (2001).

Schulz, L. E. & Bonawitz, E. B. Serious fun: preschoolers engage in more exploratory play when evidence is confounded. Dev. Psychol. 43 , 1045–1050 (2007).

Gopnik, A. & Sobel, D. M. Detecting blickets: how young children use information about novel causal powers in categorization and induction. Child. Dev. 71 , 1205–1222 (2000).

Schulz, L. E., Gopnik, A. & Glymour, C. Preschool children learn about causal structure from conditional interventions. Dev. Sci. 10 , 322–332 (2007).

Walker, C. M., Gopnik, A. & Ganea, P. A. Learning to learn from stories: children’s developing sensitivity to the causal structure of fictional worlds. Child. Dev. 86 , 310–318 (2015).

Schulz, L. E., Bonawitz, E. B. & Griffiths, T. L. Can being scared cause tummy aches? Naive theories, ambiguous evidence, and preschoolers’ causal inferences. Dev. Psychol. 43 , 1124–1139 (2007).

Kushnir, T. & Gopnik, A. Young children infer causal strength from probabilities and interventions. Psychol. Sci. 16 , 678–683 (2005).

Walker, C. M. & Gopnik, A. Toddlers infer higher-order relational principles in causal learning. Psychol. Sci. 25 , 161–169 (2014). This paper shows that 18–30-month-old infants can learn relational causal rules and generalize them to novel stimuli.

Sobel, D. M., Yoachim, C. M., Gopnik, A., Meltzoff, A. N. & Blumenthal, E. J. The blicket within: preschoolers’ inferences about insides and causes. J. Cogn. Dev. 8 , 159–182 (2007).

Schulz, L. E. & Sommerville, J. God does not play dice: causal determinism and preschoolers’ causal inferences. Child. Dev. 77 , 427–442 (2006).

Schulz, L. E. & Gopnik, A. Causal learning across domains. Dev. Psychol. 40 , 162–176 (2004).

Seiver, E., Gopnik, A. & Goodman, N. D. Did she jump because she was the big sister or because the trampoline was safe? Causal inference and the development of social attribution. Child. Dev. 84 , 443–454 (2013).

Vasilyeva, N., Gopnik, A. & Lombrozo, T. The development of structural thinking about social categories. Dev. Psychol. 54 , 1735–1744 (2018).

Kushnir, T., Xu, F. & Wellman, H. M. Young children use statistical sampling to infer the preferences of other people. Psychol. Sci. 21 , 1134–1140 (2010).

Kushnir, T. & Gopnik, A. Conditional probability versus spatial contiguity in causal learning: preschoolers use new contingency evidence to overcome prior spatial assumptions. Dev. Psychol. 43 , 186–196 (2007).

Kimura, K. & Gopnik, A. Rational higher‐order belief revision in young children. Child. Dev. 90 , 91–97 (2019).

Goddu, M. K. & Gopnik, A. Learning what to change: young children use “difference-making” to identify causally relevant variables. Dev. Psychol. 56 , 275–284 (2020).

Gopnik, A. et al. Changes in cognitive flexibility and hypothesis search across human life history from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114 , 7892–7899 (2017).

Lucas, C. G., Bridgers, S., Griffiths, T. L. & Gopnik, A. When children are better (or at least more open-minded) learners than adults: developmental differences in learning the forms of causal relationships. Cognition 131 , 284–299 (2014). This paper shows that young children learn and generalize unusual causal relationships more readily than adults do.

Goddu, M. K., Lombrozo, T. & Gopnik, A. Transformations and transfer: preschool children understand abstract relations and reason analogically in a causal task. Child. Dev. 91 , 1898–1915 (2020).

Magid, R. W., Sheskin, M. & Schulz, L. E. Imagination and the generation of new ideas. Cogn. Dev. 34 , 99–110 (2015).

Liquin, E. G. & Gopnik, A. Children are more exploratory and learn more than adults in an approach–avoid task. Cognition 218 , 104940 (2022).

Erickson, J. E., Keil, F. C. & Lockhart, K. L. Sensing the coherence of biology in contrast to psychology: young children’s use of causal relations to distinguish two foundational domains. Child Dev. 81 , 390–409 (2010).

Keil, F. C. Concepts, Kinds, and Cognitive Development (MIT Press, 1992).

Carey, S. Conceptual Change in Childhood (MIT Press, 1987).

Gelman, S. A. The Essential Child: Origins of Essentialism in Everyday Thought (Oxford Univ. Press, 2003).

Ahl, R. E., DeAngelis, E. & Keil, F. C. “I know it’s complicated”: children detect relevant information about object complexity. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 222 , 105465 (2022).

Chuey, A. et al. No guts, no glory: underestimating the benefits of providing children with mechanistic details. npj Sci. Learn. 6 , 30 (2021).

Keil, F. C. & Lockhart, K. L. Beyond cause: the development of clockwork cognition. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 30 , 167–173 (2021).

Chuey, A., Lockhart, K., Sheskin, M. & Keil, F. Children and adults selectively generalize mechanistic knowledge. Cognition 199 , 104231 (2020).

Lockhart, K. L., Chuey, A., Kerr, S. & Keil, F. C. The privileged status of knowing mechanistic information: an early epistemic bias. Child Dev. 90 , 1772–1788 (2019).

Kominsky, J. F., Zamm, A. P. & Keil, F. C. Knowing when help is needed: a developing sense of causal complexity. Cogn. Sci. 42 , 491–523 (2018).

Mills, C. M. & Keil, F. C. Knowing the limits of one’s understanding: the development of an awareness of an illusion of explanatory depth. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 87 , 1–32 (2004).

Goldwater, M. B. & Gentner, D. On the acquisition of abstract knowledge: structural alignment and explication in learning causal system categories. Cognition 137 , 137–153 (2015).

Rottman, B. M., Gentner, D. & Goldwater, M. B. Causal systems categories: differences in novice and expert categorization of causal phenomena. Cogn. Sci. 36 , 919–932 (2012).

Bonawitz, E. B. et al. Just do it? Investigating the gap between prediction and action in toddlers’ causal inferences. Cognition 115 , 104–117 (2010). This study demonstrates that the ability to infer causal relations from observations of correlational information without an agent’s involvement or the use of causal language develops at around the age of four years.

Herrmann, E., Call, J., Hernández-Lloreda, M. V., Hare, B. & Tomasello, M. Humans have evolved specialized skills of social cognition: the cultural intelligence hypothesis. Science 317 , 1360–1366 (2007).

Tomasello, M. Becoming Human: A Theory of Ontogeny (Harvard Univ. Press, 2019).

Henrich, J. The Secret of our Success (Princeton Univ. Press, 2015).

Hesslow, G. in Contemporary Science and Natural Explanation: Commonsense Conceptions of Causality (ed. Hilton, D. J.) 11–32 (New York Univ. Press, 1988).

Woodward, J. The problem of variable choice. Synthese 193 , 1047–1072 (2016).

Khalid, S., Khalil, T. & Nasreen, S. A survey of feature selection and feature extraction techniques in machine learning. In 2014 Science and Information Conf . 372–378 (IEEE, 1988).

Bonawitz, E., Denison, S., Griffiths, T. L. & Gopnik, A. Probabilistic models, learning algorithms, and response variability: sampling in cognitive development. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18 , 497–500 (2014).

Bonawitz, E., Denison, S., Gopnik, A. & Griffiths, T. L. Win–stay, lose–sample: a simple sequential algorithm for approximating Bayesian inference. Cogn. Psychol. 74 , 35–65 (2014).

Denison, S., Bonawitz, E., Gopnik, A. & Griffiths, T. L. Rational variability in children’s causal inferences: the sampling hypothesis. Cognition 126 , 285–300 (2013).

Samland, J., Josephs, M., Waldmann, M. R. & Rakoczy, H. The role of prescriptive norms and knowledge in children’s and adults’ causal selection. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145 , 125–130 (2016).

Samland, J. & Waldmann, M. R. How prescriptive norms influence causal inferences. Cognition 156 , 164–176 (2016).

Phillips, J., Morris, A. & Cushman, F. How we know what not to think. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23 , 1026–1040 (2019).

Gureckis, T. M. & Markant, D. B. Self-directed learning: a cognitive and computational perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7 , 464–481 (2012).

Saylor, M. & Ganea, P. Active Learning from Infancy to Childhood (Springer, 2018).

Goddu, M. K. & Gopnik, A. in The Cambridge Handbook of Cognitive Development (eds Houdé, O. & Borst, G.) 299–317 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Gopnik, A. Scientific thinking in young children: theoretical advances, empirical research, and policy implications. Science 337 , 1623–1627 (2012).

Weisberg, D. S. & Sobel, D. M. Constructing Science: Connecting Causal Reasoning to Scientific Thinking in Young Children (MIT Press, 2022).

Xu, F. Towards a rational constructivist theory of cognitive development. Psychol. Rev. 126 , 841 (2019).

Xu, F. & Kushnir, T. Infants are rational constructivist learners. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22 , 28–32 (2013).

Lapidow, E. & Bonawitz, E. What’s in the box? Preschoolers consider ambiguity, expected value, and information for future decisions in explore-exploit tasks. Open. Mind 7 , 855–878 (2023).

Kidd, C., Piantadosi, S. T. & Aslin, R. N. The Goldilocks effect: human infants allocate attention to visual sequences that are neither too simple nor too complex. PLoS One 7 , e36399 (2012).

Ruggeri, A., Swaboda, N., Sim, Z. L. & Gopnik, A. Shake it baby, but only when needed: preschoolers adapt their exploratory strategies to the information structure of the task. Cognition 193 , 104013 (2019).

Sim, Z. L. & Xu, F. Another look at looking time: surprise as rational statistical inference. Top. Cogn. Sci. 11 , 154–163 (2019).

Sim, Z. L. & Xu, F. Infants preferentially approach and explore the unexpected. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 35 , 596–608 (2017).

Siegel, M. H., Magid, R. W., Pelz, M., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Schulz, L. E. Children’s exploratory play tracks the discriminability of hypotheses. Nat. Commun. 12 , 3598 (2021).

Schulz, E., Wu, C. M., Ruggeri, A. & Meder, B. Searching for rewards like a child means less generalization and more directed exploration. Psychol. Sci. 30 , 1561–1572 (2019).

Schulz, L. Infants explore the unexpected. Science 348 , 42–43 (2015).

Perez, J. & Feigenson, L. Violations of expectation trigger infants to search for explanations. Cognition 218 , 104942 (2022).

Cook, C., Goodman, N. D. & Schulz, L. E. Where science starts: spontaneous experiments in preschoolers’ exploratory play. Cognition 120 , 341–349 (2011). This study demonstrates that preschoolers spontaneously perform causal interventions that are relevant to disambiguating multiple possible causal structures in their free play.

Lapidow, E. & Walker, C. M. Learners’ causal intuitions explain behavior in control of variables tasks. Dev. Psychol. (in the press).

Lapidow, E. & Walker, C. M. Rethinking the “gap”: self‐directed learning in cognitive development and scientific reasoning. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 13 , e1580 (2022). This theory paper provides a complementary viewpoint to ‘child-as-scientist’, or Bayesian ‘rational constructivist’, account, arguing that children seek to identify and generate evidence for causal relations that are robust across contexts (and thus will be reliable for causal intervention).

Lapidow, E. & Walker, C. M. Informative experimentation in intuitive science: children select and learn from their own causal interventions. Cognition 201 , 104315 (2020).

Moeller, A., Sodian, B. & Sobel, D. M. Developmental trajectories in diagnostic reasoning: understanding data are confounded develops independently of choosing informative interventions to resolve confounded data. Front. Psychol. 13 , 800226 (2022).

Fernbach, P. M., Macris, D. M. & Sobel, D. M. Which one made it go? The emergence of diagnostic reasoning in preschoolers. Cogn. Dev. 27 , 39–53 (2012).

Buchanan, D. W. & Sobel, D. M. Mechanism‐based causal reasoning in young children. Child. Dev. 82 , 2053–2066 (2011).

Sobel, D. M., Benton, D., Finiasz, Z., Taylor, Y. & Weisberg, D. S. The influence of children’s first action when learning causal structure from exploratory play. Cogn. Dev. 63 , 101194 (2022).

Lapidow, E. & Walker, C. M. The Search for Invariance: Repeated Positive Testing Serves the Goals of Causal Learning (Springer, 2020).

Klayman, J. Varieties of confirmation bias. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 32 , 385–418 (1995).

Zimmerman, C. The development of scientific thinking skills in elementary and middle school. Dev. Rev. 27 , 172–223 (2007).

Rule, J. S., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Piantadosi, S. T. The child as hacker. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24 , 900–915 (2020).

Burghardt, G. M. The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limits (MIT Press, 2005).

Chu, J. & Schulz, L. E. Play, curiosity, and cognition. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2 , 317–343 (2020).

Schulz, L. The origins of inquiry: inductive inference and exploration in early childhood. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 , 382–389 (2012).

Harris, P. L., Kavanaugh, R. D., Wellman, H. M. & Hickling, A. K. in Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development https://doi.org/10.2307/1166074 (Society for Research in Child Development, 1993).

Weisberg, D. S. in The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Imagination (ed. Taylor, M.) 75–93 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Gopnik, A. & Walker, C. M. Considering counterfactuals: the relationship between causal learning and pretend play. Am. J. Play. 6 , 15–28 (2013).

Weisberg, D. S. & Gopnik, A. Pretense, counterfactuals, and Bayesian causal models: why what is not real really matters. Cogn. Sci. 37 , 1368–1381 (2013).

Root-Bernstein, M. M. in The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Imagination (ed. Taylor, M.) 417–437 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Buchsbaum, D., Bridgers, S., Skolnick Weisberg, D. & Gopnik, A. The power of possibility: causal learning, counterfactual reasoning, and pretend play. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367 , 2202–2212 (2012).

Wente, A., Gopnik, A., Fernández Flecha, M., Garcia, T. & Buchsbaum, D. Causal learning, counterfactual reasoning and pretend play: a cross-cultural comparison of Peruvian, mixed-and low-socioeconomic status US children. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 377 , 20210345 (2022).

Buchsbaum, D., Gopnik, A., Griffiths, T. L. & Shafto, P. Children’s imitation of causal action sequences is influenced by statistical and pedagogical evidence. Cognition 120 , 331–340 (2011).

Csibra, G. & Gergely, G. ‘Obsessed with goals’: functions and mechanisms of teleological interpretation of actions in humans. Acta Psychol. 124 , 60–78 (2007).

Kelemen, D. The scope of teleological thinking in preschool children. Cognition 70 , 241–272 (1999).

Casler, K. & Kelemen, D. Young children’s rapid learning about artifacts. Dev. Sci. 8 , 472–480 (2005).

Casler, K. & Kelemen, D. Reasoning about artifacts at 24 months: the developing teleo-functional stance. Cognition 103 , 120–130 (2007).

Ruiz, A. M. & Santos, L. R. 6. in Tool Use in Animals: Cognition and Ecology 119–133 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Walker, C. M., Rett, A. & Bonawitz, E. Design drives discovery in causal learning. Psychol. Sci. 31 , 129–138 (2020).

Butler, L. P. & Markman, E. M. Finding the cause: verbal framing helps children extract causal evidence embedded in a complex scene. J. Cogn. Dev. 13 , 38–66 (2012).

Callanan, M. A. et al. Exploration, explanation, and parent–child interaction in museums. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. Dev. 85 , 7–137 (2020).

McHugh, S. R., Callanan, M., Jaeger, G., Legare, C. H. & Sobel, D. M. Explaining and exploring the dynamics of parent–child interactions and children’s causal reasoning at a children’s museum exhibit. Child Dev . https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.14035 (2023).

Sobel, D. M., Letourneau, S. M., Legare, C. H. & Callanan, M. Relations between parent–child interaction and children’s engagement and learning at a museum exhibit about electric circuits. Dev. Sci. 24 , e13057 (2021).

Willard, A. K. et al. Explain this, explore that: a study of parent–child interaction in a children’s museum. Child Dev. 90 , e598–e617 (2019).

Daubert, E. N., Yu, Y., Grados, M., Shafto, P. & Bonawitz, E. Pedagogical questions promote causal learning in preschoolers. Sci. Rep. 10 , 20700 (2020).

Yu, Y., Landrum, A. R., Bonawitz, E. & Shafto, P. Questioning supports effective transmission of knowledge and increased exploratory learning in pre‐kindergarten children. Dev. Sci. 21 , e12696 (2018).

Walker, C. M. & Nyhout, A. in The Questioning Child: Insights From Psychology and Education (eds Butler, L. P., Ronfard, S. & Corriveau, K. H.) 252–280 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2020).

Weisberg, D. S. & Hopkins, E. J. Preschoolers’ extension and export of information from realistic and fantastical stories. Infant. Child. Dev. 29 , e2182 (2020).

Tillman, K. A. & Walker, C. M. You can’t change the past: children’s recognition of the causal asymmetry between past and future events. Child. Dev. 93 , 1270–1283 (2022).

Rottman, B. M., Kominsky, J. F. & Keil, F. C. Children use temporal cues to learn causal directionality. Cogn. Sci. 38 , 489–513 (2014).

Tecwyn, E. C., Mazumder, P. & Buchsbaum, D. One- and two-year-olds grasp that causes must precede their effects. Dev. Psychol. 59 , 1519–1531 (2023).

Liquin, E. G. & Lombrozo, T. Explanation-seeking curiosity in childhood. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 35 , 14–20 (2020).

Mills, C. M., Legare, C. H., Bills, M. & Mejias, C. Preschoolers use questions as a tool to acquire knowledge from different sources. J. Cogn. Dev. 11 , 533–560 (2010).

Ruggeri, A., Sim, Z. L. & Xu, F. “Why is Toma late to school again?” Preschoolers identify the most informative questions. Dev. Psychol. 53 , 1620–1632 (2017).

Ruggeri, A. & Lombrozo, T. Children adapt their questions to achieve efficient search. Cognition 143 , 203–216 (2015).

Legare, C. H. & Lombrozo, T. Selective effects of explanation on learning during early childhood. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 126 , 198–212 (2014).

Legare, C. H. Exploring explanation: explaining inconsistent evidence informs exploratory, hypothesis‐testing behavior in young children. Child Dev. 83 , 173–185 (2012).

Walker, C. M., Lombrozo, T., Legare, C. H. & Gopnik, A. Explaining prompts children to privilege inductively rich properties. Cognition 133 , 343–357 (2014).

Vasil, N., Ruggeri, A. & Lombrozo, T. When and how children use explanations to guide generalizations. Cogn. Dev. 61 , 101144 (2022).

Walker, C. M., Bonawitz, E. & Lombrozo, T. Effects of explaining on children’s preference for simpler hypotheses. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 24 , 1538–1547 (2017).

Walker, C. M. & Lombrozo, T. Explaining the moral of the story. Cognition 167 , 266–281 (2017).

Walker, C. M., Lombrozo, T., Williams, J. J., Rafferty, A. N. & Gopnik, A. Explaining constrains causal learning in childhood. Child. Dev. 88 , 229–246 (2017).

Gopnik, A. Childhood as a solution to explore–exploit tensions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 375 , 20190502 (2020).

Wente, A. O. et al. Causal learning across culture and socioeconomic status. Child. Dev. 90 , 859–875 (2019).

Carstensen, A. et al. Context shapes early diversity in abstract thought. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116 , 13891–13896 (2019). This study provides evidence for developmentally early emerging cross-cultural differences in learning ‘individual’ versus ‘relational’ causal rules in children from individualist versus collectivist societies.

Ross, N., Medin, D., Coley, J. D. & Atran, S. Cultural and experiential differences in the development of folkbiological induction. Cogn. Dev. 18 , 25–47 (2003).

Inagaki, K. The effects of raising animals on children’s biological knowledge. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 8 , 119–129 (1990).

Cole, M. & Bruner, J. S. Cultural differences and inferences about psychological processes. Am. Psychol. 26 , 867–876 (1971).

Rogoff, B. & Morelli, G. Perspectives on children’s development from cultural psychology. Am. Psychol. 44 , 343–348 (1989).

Rogoff, B. Adults and peers as agents of socialization: a highland Guatemalan profile. Ethos 9 , 18–36 (1981).

Shneidman, L., Gaskins, S. & Woodward, A. Child‐directed teaching and social learning at 18 months of age: evidence from Yucatec Mayan and US infants. Dev. Sci. 19 , 372–381 (2016).

Callanan, M., Solis, G., Castañeda, C. & Jipson, J. in The Questioning Child: Insights From Psychology and Education (eds Butler, L. P., Ronfard, S. & Corriveau, K. H.) 73–88 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2020).

Gauvain, M., Munroe, R. L. & Beebe, H. Children’s questions in cross-cultural perspective: a four-culture study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 44 , 1148–1165 (2013).

Adolph, K. E. & Hoch, J. E. Motor development: embodied, embedded, enculturated, and enabling. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70 , 141–164 (2019).

Schleihauf, H., Herrmann, E., Fischer, J. & Engelmann, J. M. How children revise their beliefs in light of reasons. Child. Dev. 93 , 1072–1089 (2022).

Vasil, N. et al. Structural explanations lead young children and adults to rectify resource inequalities. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 242 , 105896 (2024).

Koskuba, K., Gerstenberg, T., Gordon, H., Lagnado, D. & Schlottmann, A. What’s fair? How children assign reward to members of teams with differing causal structures. Cognition 177 , 234–248 (2018).

Bowlby, J. The Bowlby–Ainsworth attachment theory. Behav. Brain Sci. 2 , 637–638 (1979).

Tottenham, N., Shapiro, M., Flannery, J., Caldera, C. & Sullivan, R. M. Parental presence switches avoidance to attraction learning in children. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3 , 1070–1077 (2019).

Frankenhuis, W. E. & Gopnik, A. Early adversity and the development of explore–exploit tradeoffs. Trends Cogn. Sci. 27 , 616–630 (2023).

Van IJzendoorn, M. H. & Kroonenberg, P. M. Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: a meta-analysis of the strange situation. Child Dev. 59 , 147–156 (1988).

Gopnik, A. Explanation as orgasm. Minds Mach. 8 , 101–118 (1998).

Gottlieb, S., Keltner, D. & Lombrozo, T. Awe as a scientific emotion. Cogn. Sci. 42 , 2081–2094 (2018).

Valdesolo, P., Shtulman, A. & Baron, A. S. Science is awe-some: the emotional antecedents of science learning. Emot. Rev. 9 , 215–221 (2017).

Keil, F. C. Wonder: Childhood and the Lifelong Love of Science (MIT Press, 2022).

Perez, J. & Feigenson, L. Stable individual differences in infants’ responses to violations of intuitive physics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118 , e2103805118 (2021).

Goddu, M. K., Sullivan, J. N. & Walker, C. M. Toddlers learn and flexibly apply multiple possibilities. Child. Dev. 92 , 2244–2251 (2021).

Cisek, P. Resynthesizing behavior through phylogenetic refinement. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 81 , 2265–2287 (2019).

Pezzulo, G. & Cisek, P. Navigating the affordance landscape: feedback control as a process model of behavior and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20 , 414–424 (2016).

Cisek, P. Cortical mechanisms of action selection: the affordance competition hypothesis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 362 , 1585–1599 (2007).

Tomasello, M. The Evolution of Agency: Behavioral Organization From Lizards to Humans (MIT Press, 2022).

Beck, S. R., Robinson, E. J., Carroll, D. J. & Apperly, I. A. Children’s thinking about counterfactuals and future hypotheticals as possibilities. Child. Dev. 77 , 413–426 (2006).

Robinson, E. J., Rowley, M. G., Beck, S. R., Carroll, D. J. & Apperly, I. A. Children’s sensitivity to their own relative ignorance: handling of possibilities under epistemic and physical uncertainty. Child. Dev. 77 , 1642–1655 (2006).

Leahy, B. P. & Carey, S. E. The acquisition of modal concepts. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24 , 65–78 (2020).

Mody, S. & Carey, S. The emergence of reasoning by the disjunctive syllogism in early childhood. Cognition 154 , 40–48 (2016).

Shtulman, A. & Carey, S. Improbable or impossible? How children reason about the possibility of extraordinary events. Child Dev. 78 , 1015–1032 (2007).

Redshaw, J. & Suddendorf, T. Children’s and apes’ preparatory responses to two mutually exclusive possibilities. Curr. Biol. 26 , 1758–1762 (2016).

Phillips, J. S. & Kratzer, A. Decomposing modal thought. Psychol. Rev. (in the press).

Vetter, B. Abilities and the epistemology of ordinary modality. Mind (in the press).

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. Variants of uncertainty. Cognition 11 , 143–157 (1982).

Rafetseder, E., Schwitalla, M. & Perner, J. Counterfactual reasoning: from childhood to adulthood. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 114 , 389–404 (2013).

Beck, S. R. & Riggs, K. J. Developing thoughts about what might have been. Child Dev. Perspect. 8 , 175–179 (2014).

Kominsky, J. F. et al. The trajectory of counterfactual simulation in development. Dev. Psychol. 57 , 253 (2021). This study uses a physical collision paradigm to demonstrate that the content of children’s counterfactual judgements changes over development.

Gerstenberg, T. What would have happened? Counterfactuals, hypotheticals and causal judgements. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 377 , 20210339 (2022).

Gerstenberg, T., Goodman, N. D., Lagnado, D. A. & Tenenbaum, J. B. A counterfactual simulation model of causal judgments for physical events. Psychol. Rev. 128 , 936 (2021).

Nyhout, A. & Ganea, P. A. The development of the counterfactual imagination. Child Dev. Perspect. 13 , 254–259 (2019).

Nyhout, A. & Ganea, P. A. Mature counterfactual reasoning in 4- and 5-year-olds. Cognition 183 , 57–66 (2019).

Moll, H., Meltzoff, A. N., Merzsch, K. & Tomasello, M. Taking versus confronting visual perspectives in preschool children. Dev. Psychol. 49 , 646–654 (2013).

Moll, H. & Tomasello, M. Three-year-olds understand appearance and reality — just not about the same object at the same time. Dev. Psychol. 48 , 1124–1132 (2012).

Moll, H. & Meltzoff, A. N. How does it look? Level 2 perspective‐taking at 36 months of age. Child. Dev. 82 , 661–673 (2011).

Gopnik, A., Slaughter, V. & Meltzoff, A. in Children’s Early Understanding of Mind: Origins and Development (eds Lewis, C. & Mitchell, P.) 157–181 (Routledge, 1994).

Gopnik, A. & Astington, J. W. Children’s understanding of representational change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance–reality distinction. Child Dev. 59 , 26–37 (1988).

Doherty, M. & Perner, J. Metalinguistic awareness and theory of mind: just two words for the same thing? Cogn. Dev. 13 , 279–305 (1998).

Wimmer, H. & Perner, J. Beliefs about beliefs: representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition 13 , 103–128 (1983).

Flavell, J. H., Speer, J. R., Green, F. L., August, D. L. & Whitehurst, G. J. in Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 1–65 (Society for Research in Child Development, 1981).

Wellman, H. M., Cross, D. & Watson, J. Meta‐analysis of theory‐of‐mind development: the truth about false belief. Child. Dev. 72 , 655–684 (2001).

Kelemen, D. & DiYanni, C. Intuitions about origins: purpose and intelligent design in children’s reasoning about nature. J. Cogn. Dev. 6 , 3–31 (2005).

Kelemen, D. Why are rocks pointy? Children’s preference for teleological explanations of th natural world. Dev. Psychol. 35 , 1440 (1999).

Vihvelin, K. Causes, Laws, and Free Will: Why Determinism Doesn’t Matter (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Yiu, E., Kosoy, E. & Gopnik, A. Transmission versus truth, imitation versus innovation: what children can do that large language and language-and-vision models cannot (yet). Persp. Psychol. Sci . https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231201401 (2023).

Kosoy, E. et al. Towards understanding how machines can learn causal overhypotheses. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.08353 (2022).

Frank, M. C. Baby steps in evaluating the capacities of large language models. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2 , 451–452 (2023).

Frank, M. C. Bridging the data gap between children and large language models. Trends Cogn. Sci . 27 , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2023.08.007 (2023).

Schmidhuber, J. A possibility for implementing curiosity and boredom in model-building neural controllers. In Proc. Int. Conf. on Simulation of Adaptive Behavior: From Animals to Animats 222–227 (MIT Press, 1991).

Volpi, N. C. & Polani, D. Goal-directed empowerment: combining intrinsic motivation and task-oriented behaviour. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 15 , 361–372 (2020).

Salge, C., Glackin, C. & Polani, D. in Guided Self-Organization: Inception . Emergence, Complexity and Computation Vol. 9 (ed. Prokopenko, M.) 67–114 (Springer, 2014).

Klyubin, A. S., Polani, D. & Nehaniv, C. L. Empowerment: a universal agent-centric measure of control. In 2005 IEEE Congr. on Evolutionary Computation 128–135 (IEEE, 2005).

Gopnik, A. Empowerment as causal learning, causal learning as empowerment: a bridge between Bayesian causal hypothesis testing and reinforcement learning. Preprint at https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/id/eprint/23268 (2024).

Rovee-Collier, C. K., Sullivan, M. W., Enright, M., Lucas, D. & Fagen, J. W. Reactivation of infant memory. Science 208 , 1159–1161 (1980).

Kominsky, J. F., Li, Y. & Carey, S. Infants’ attributions of insides and animacy in causal interactions. Cogn. Sci. 46 , e13087 (2022).

Lakusta, L. & Carey, S. Twelve-month-old infants’ encoding of goal and source paths in agentive and non-agentive motion events. Lang. Learn. Dev. 11 , 152–175 (2015).

Saxe, R., Tzelnic, T. & Carey, S. Knowing who dunnit: infants identify the causal agent in an unseen causal interaction. Dev. Psychol. 43 , 149–158 (2007).

Saxe, R., Tenenbaum, J. & Carey, S. Secret agents: inferences about hidden causes by 10- and 12-month-old infants. Psychol. Sci. 16 , 995–1001 (2005).

Liu, S., Brooks, N. B. & Spelke, E. S. Origins of the concepts cause, cost, and goal in prereaching infants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116 , 17747–17752 (2019).

Liu, S. & Spelke, E. S. Six-month-old infants expect agents to minimize the cost of their actions. Cognition 160 , 35–42 (2017).

Nyhout, A. & Ganea, P. A. What is and what never should have been: children’s causal and counterfactual judgments about the same events. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 192 , 104773 (2020).

Legare, C. H. The contributions of explanation and exploration to children’s scientific reasoning. Child. Dev. Perspect. 8 , 101–106 (2014).

Denison, S. & Xu, F. Twelve‐to 14‐month‐old infants can predict single‐event probability with large set sizes. Dev. Sci. 13 , 798–803 (2010).

Denison, S., Reed, C. & Xu, F. The emergence of probabilistic reasoning in very young infants: evidence from 4.5-and 6-month-olds. Dev. Psychol. 49 , 243 (2013).

Alderete, S. & Xu, F. Three-year-old children’s reasoning about possibilities. Cognition 237 , 105472 (2023).

Scholl, B. J. & Tremoulet, P. D. Perceptual causality and animacy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4 , 299–309 (2000).

Hood, B., Carey, S. & Prasada, S. Predicting the outcomes of physical events: two‐year‐olds fail to reveal knowledge of solidity and support. Child. Dev. 71 , 1540–1554 (2000).

Hood, B. M., Hauser, M. D., Anderson, L. & Santos, L. Gravity biases in a non‐human primate? Dev. Sci. 2 , 35–41 (1999).

Hood, B. M. Gravity does rule for falling events. Dev. Sci. 1 , 59–63 (1998).

Hood, B. M. Gravity rules for 2-to 4-year olds? Cognit. Dev. 10 , 577–598 (1995).

Woodward, A. L. Infants selectively encode the goal object of an actor’s reach. Cognition 69 , 1–34 (1998).

Woodward, A. L. Infants’ grasp of others’ intentions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 18 , 53–57 (2009).

Woodward, A. L., Sommerville, J. A., Gerson, S., Henderson, A. M. & Buresh, J. The emergence of intention attribution in infancy. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 51 , 187–222 (2009).

Meltzoff, A. N. ‘Like me’: a foundation for social cognition. Dev. Sci. 10 , 126–134 (2007).

Gerson, S. A. & Woodward, A. L. The joint role of trained, untrained, and observed actions at the origins of goal recognition. Infant. Behav. Dev. 37 , 94–104 (2014).

Gerson, S. A. & Woodward, A. L. Learning from their own actions: the unique effect of producing actions on infants’ action understanding. Child. Dev. 85 , 264–277 (2014).

Sommerville, J. A., Woodward, A. L. & Needham, A. Action experience alters 3-month-old infants’ perception of others’ actions. Cognition 96 , B1–B11 (2005).

Liu, S. & Almeida, M. Knowing before doing: review and mega-analysis of action understanding in prereaching infants. Psychol. Bull. 149 , 294–310 (2023).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge their funding sources: the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the Templeton World Charity Foundation (0434), the John Templeton Foundation (6145), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (047498-002 Machine Common Sense), the Department of Defense Multidisciplinary University Initiative (Self-Learning perception Through Real World Interaction), and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Catalyst Award. For helpful discussions, comments, and other forms of support, the authors thank: S. Boardman, E. Bonawitz, B. Brast-McKie, D. Buchsbaum, M. Deigan, J. Engelmann, T. Friend, T. Gerstenberg, S. Kikkert, A. Kratzer, E. Lapidow, B. Leahy, T. Lombrozo, J. Phillips, H. Rakoczy, L. Schulz, D. Sobel, E. Spelke, H. Steward, B. Vetter, M. Waldmann and E. Yiu.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Philosophy, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Mariel K. Goddu

Institut für Philosophie, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Centre for Advanced Study in the Humanities: Human Abilities, Berlin, Germany

Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA

Alison Gopnik

Department of Philosophy Affiliate, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.K.G. wrote the article and created the figures. A.G. contributed substantially to discussion of the content and to multiple revisions. A.G. and M.K.G. together reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Mariel K. Goddu or Alison Gopnik .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Psychology thanks Jonathan Kominsky and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Goddu, M.K., Gopnik, A. The development of human causal learning and reasoning. Nat Rev Psychol 3 , 319–339 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00300-5

Download citation

Accepted : 11 March 2024

Published : 26 April 2024

Issue Date : May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00300-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Cancer risk, wine preference, and your genes

Excited about new diet drug? This procedure seems better choice.

How friends helped fuel the rise of a relentless enemy

Good genes are nice, but joy is better.

Harvard Staff Writer

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Part of the tackling issues of aging series.

A series on how Harvard researchers are tackling the problematic issues of aging.

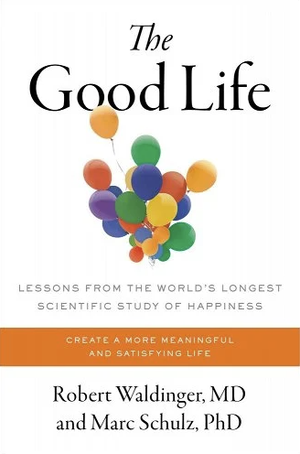

W hen scientists began tracking the health of 268 Harvard sophomores in 1938 during the Great Depression, they hoped the longitudinal study would reveal clues to leading healthy and happy lives.

They got more than they wanted.

After following the surviving Crimson men for nearly 80 years as part of the Harvard Study of Adult Development , one of the world’s longest studies of adult life, researchers have collected a cornucopia of data on their physical and mental health.

Of the original Harvard cohort recruited as part of the Grant Study, only 19 are still alive, all in their mid-90s. Among the original recruits were eventual President John F. Kennedy and longtime Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee. (Women weren’t in the original study because the College was still all male.)

In addition, scientists eventually expanded their research to include the men’s offspring, who now number 1,300 and are in their 50s and 60s, to find out how early-life experiences affect health and aging over time. Some participants went on to become successful businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and others ended up as schizophrenics or alcoholics, but not on inevitable tracks.

“Loneliness kills. It’s as powerful as smoking or alcoholism.” Robert Waldinger, psychiatrist, Massachusetts General Hospital

During the intervening decades, the control groups have expanded. In the 1970s, 456 Boston inner-city residents were enlisted as part of the Glueck Study, and 40 of them are still alive. More than a decade ago, researchers began including wives in the Grant and Glueck studies.

Over the years, researchers have studied the participants’ health trajectories and their broader lives, including their triumphs and failures in careers and marriage, and the finding have produced startling lessons, and not only for the researchers.

“The surprising finding is that our relationships and how happy we are in our relationships has a powerful influence on our health,” said Robert Waldinger , director of the study, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School . “Taking care of your body is important, but tending to your relationships is a form of self-care too. That, I think, is the revelation.”

Close relationships, more than money or fame, are what keep people happy throughout their lives, the study revealed. Those ties protect people from life’s discontents, help to delay mental and physical decline, and are better predictors of long and happy lives than social class, IQ, or even genes. That finding proved true across the board among both the Harvard men and the inner-city participants.

“The people who were the most satisfied in their relationships at age 50 were the healthiest at age 80,” said Robert Waldinger with his wife Jennifer Stone.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

The long-term research has received funding from private foundations, but has been financed largely by grants from the National Institutes of Health, first through the National Institute of Mental Health, and more recently through the National Institute on Aging.

Researchers who have pored through data, including vast medical records and hundreds of in-person interviews and questionnaires, found a strong correlation between men’s flourishing lives and their relationships with family, friends, and community. Several studies found that people’s level of satisfaction with their relationships at age 50 was a better predictor of physical health than their cholesterol levels were.

“When we gathered together everything we knew about them about at age 50, it wasn’t their middle-age cholesterol levels that predicted how they were going to grow old,” said Waldinger in a popular TED Talk . “It was how satisfied they were in their relationships. The people who were the most satisfied in their relationships at age 50 were the healthiest at age 80.”

He recorded his TED talk, titled “What Makes a Good Life? Lessons from the Longest Study on Happiness,” in 2015, and it has been viewed 13,000,000 times.

The researchers also found that marital satisfaction has a protective effect on people’s mental health. Part of a study found that people who had happy marriages in their 80s reported that their moods didn’t suffer even on the days when they had more physical pain. Those who had unhappy marriages felt both more emotional and physical pain.

Those who kept warm relationships got to live longer and happier, said Waldinger, and the loners often died earlier. “Loneliness kills,” he said. “It’s as powerful as smoking or alcoholism.”

According to the study, those who lived longer and enjoyed sound health avoided smoking and alcohol in excess. Researchers also found that those with strong social support experienced less mental deterioration as they aged.

In part of a recent study , researchers found that women who felt securely attached to their partners were less depressed and more happy in their relationships two-and-a-half years later, and also had better memory functions than those with frequent marital conflicts.

“When the study began, nobody cared about empathy or attachment. But the key to healthy aging is relationships, relationships, relationships.” George Vaillant, psychiatrist

“Good relationships don’t just protect our bodies; they protect our brains,” said Waldinger in his TED talk. “And those good relationships, they don’t have to be smooth all the time. Some of our octogenarian couples could bicker with each other day in and day out, but as long as they felt that they could really count on the other when the going got tough, those arguments didn’t take a toll on their memories.”

Since aging starts at birth, people should start taking care of themselves at every stage of life, the researchers say.

“Aging is a continuous process,” Waldinger said. “You can see how people can start to differ in their health trajectory in their 30s, so that by taking good care of yourself early in life you can set yourself on a better course for aging. The best advice I can give is ‘Take care of your body as though you were going to need it for 100 years,’ because you might.”

The study, like its remaining original subjects, has had a long life, spanning four directors, whose tenures reflected their medical interests and views of the time.

Under the first director, Clark Heath, who stayed from 1938 until 1954, the study mirrored the era’s dominant view of genetics and biological determinism. Early researchers believed that physical constitution, intellectual ability, and personality traits determined adult development. They made detailed anthropometric measurements of skulls, brow bridges, and moles, wrote in-depth notes on the functioning of major organs, examined brain activity through electroencephalograms, and even analyzed the men’s handwriting.

Now, researchers draw men’s blood for DNA testing and put them into MRI scanners to examine organs and tissues in their bodies, procedures that would have sounded like science fiction back in 1938. In that sense, the study itself represents a history of the changes that life brings.

6 factors predicting healthy aging According to George Vaillant’s book “Aging Well,” from observations of Harvard men in long-term aging study

Physically active.

Absence of alcohol abuse and smoking

Having mature mechanisms to cope with life’s ups and downs

Healthy weight

Stable marriage.

Psychiatrist George Vaillant, who joined the team as a researcher in 1966, led the study from 1972 until 2004. Trained as a psychoanalyst, Vaillant emphasized the role of relationships, and came to recognize the crucial role they played in people living long and pleasant lives.

In a book called “Aging Well,” Vaillant wrote that six factors predicted healthy aging for the Harvard men: physical activity, absence of alcohol abuse and smoking, having mature mechanisms to cope with life’s ups and downs, and enjoying both a healthy weight and a stable marriage. For the inner-city men, education was an additional factor. “The more education the inner city men obtained,” wrote Vaillant, “the more likely they were to stop smoking, eat sensibly, and use alcohol in moderation.”

Vaillant’s research highlighted the role of these protective factors in healthy aging. The more factors the subjects had in place, the better the odds they had for longer, happier lives.

“When the study began, nobody cared about empathy or attachment,” said Vaillant. “But the key to healthy aging is relationships, relationships, relationships.”

“We want to find out how it is that a difficult childhood reaches across decades to break down the body in middle age and later.” Robert Waldinger

The study showed that the role of genetics and long-lived ancestors proved less important to longevity than the level of satisfaction with relationships in midlife, now recognized as a good predictor of healthy aging. The research also debunked the idea that people’s personalities “set like plaster” by age 30 and cannot be changed.

“Those who were clearly train wrecks when they were in their 20s or 25s turned out to be wonderful octogenarians,” he said. “On the other hand, alcoholism and major depression could take people who started life as stars and leave them at the end of their lives as train wrecks.”

The study’s fourth director, Waldinger has expanded research to the wives and children of the original men. That is the second-generation study, and Waldinger hopes to expand it into the third and fourth generations. “It will probably never be replicated,” he said of the lengthy research, adding that there is yet more to learn.

“We’re trying to see how people manage stress, whether their bodies are in a sort of chronic ‘fight or flight’ mode,” Waldinger said. “We want to find out how it is that a difficult childhood reaches across decades to break down the body in middle age and later.”

Lara Tang ’18, a human and evolutionary biology concentrator who recently joined the team as a research assistant, relishes the opportunity to help find some of those answers. She joined the effort after coming across Waldinger’s TED talk in one of her classes.

“That motivated me to do more research on adult development,” said Tang. “I want to see how childhood experiences affect developments of physical health, mental health, and happiness later in life.”

Asked what lessons he has learned from the study, Waldinger, who is a Zen priest, said he practices meditation daily and invests time and energy in his relationships, more than before.

“It’s easy to get isolated, to get caught up in work and not remembering, ‘Oh, I haven’t seen these friends in a long time,’ ” Waldinger said. “So I try to pay more attention to my relationships than I used to.”

Share this article

Also in this series:.

Probe of Alzheimer’s follows paths of infection

Starting with microbes, Harvard-MGH researchers outline a devastating chain of events

To age better, eat better

Much of life is beyond our control, but dining smartly can help us live healthier, longer

The balance in healthy aging

To grow old well requires minimizing accidents, such as falling, as well as ailments

How old can we get? It might be written in stem cells

No clock, no crystal ball, but lots of excitement — and ambition — among Harvard scientists

Plotting the demise of Alzheimer’s

New study is major test for power of early action

You might like

Biologist separates reality of science from the claims of profiling firms

Study finds minimally invasive treatment more cost-effective over time, brings greater weight loss

Economists imagine an alternate universe where the opioid crisis peaked in ’06, and then explain why it didn’t

How old is too old to run?

No such thing, specialist says — but when your body is trying to tell you something, listen

Cease-fire will fail as long as Hamas exists, journalist says

Times opinion writer Bret Stephens also weighs in on campus unrest in final Middle East Dialogues event

TED is supported by ads and partners 00:00

Lessons from the longest study on human development

- relationships

- communication

- personal growth

- Our Mission

- Strategic Plan

- Institute History

- Annual Reviews

- Keeping Up With Kellogg ENews

- Kellogg 40th Anniversary

- Staff by Name

- Staff by Area

Human Development

- The Ford Program

- K-12 Resources

- Ford Family Notre Dame Award

- Outstanding Doctoral Student Contributions

- Distinguished Dissertation on Democracy and Human Development

- Undergraduate Mentoring Award

- Considine Award

- Bartell Prize for Undergraduate Research

- The Notre Dame Prize

- Employment Opportunities

The Kellogg Institute for International Studies, part of the University of Notre Dame’s new Keough School of Global Affairs, is an interdisciplinary community of scholars that promotes research, provides educational opportunities, and builds linkages related to democracy and human development.

Our welcoming intellectual community helps foster relationships among faculty, graduate students, undergraduate students, and visitors that promote scholarly conversation, further research ideas and insights, and build connections that are often sustained beyond Notre Dame.

- Kellogg Faculty

- Visiting Fellows

- Distinguished Research Affiliates

- Advisory Board

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- Faculty Committee

- Institute Staff

- Engage with Alumni

- International Scholars

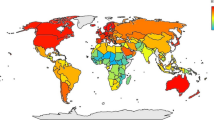

A map of the involvement of Kellogg Institute people and programs in countries around the world.

- Democracy Initiative

- Policy and Practice Labs

- Research Clusters

- Varieties of Democracy Project

- Kellogg Institute Book Series

- Kellogg Institute Working Papers

- Conference Publications

- Faculty Research Highlights

- Kellogg Funded Faculty Research

- Visiting Fellow Research

- Visiting Fellows News and Spotlights

- Work in Progress Series

- Working Groups

- Kellogg Funded Doctoral Research

- Doctoral Research Highlights

- Graduate Student News

- Comparative Politics Workshop

- Kellogg Int'l Scholars Program

- Int'l Development Studies Minor

- Kellogg/Kroc Research Grants

- Experiencing the World Fellowships

KELLOGG COMMONS The Commons is flexible space in the Hesburgh Center for our Kellogg community to study and gather in an informal setting. Open M-F, 8am to midnight. To reserve meeting rooms or for more info: 574.631.3434.

- Faculty Grant Opportunities

- Working Paper Series

- Kellogg Event Proposal Form

- Visiting Fellowships

- Postdoctoral Visiting Fellowships

- Fulbright Chair

- Other Visitor Opportunities

- Doctoral Student Affiliates

- PhD Fellowships

- Dissertation Year Fellowship

- Summer Dissertation Fellowship

- Graduate Research Grants

- Professionalization Grants

- Conference Travel Grants

- Overview Page

- Kellogg Developing Researchers Program

- Pre-Experiencing the World Fellowship Program

- Organizations

- Kellogg/Kroc Undergraduate Research Grants

- Human Development Conference

- Postgraduate Opportunities

News & Features Learn what exciting developments are happening at the Kellogg Institute. Check our latest news often to see interesting updates and stories as they develop.

Global Stage Podcasts

At the Kellogg Institute, our conceptualization of human development emphasizes above all the centrality of the human person as agent of development, and it focuses on understanding and promoting the conditions that allow people to participate in shaping their own futures and to live with dignity and freedom. It includes not only economic growth but also the social and political dimensions of development while also taking into consideration human values, context, culture, and tradition. It takes seriously the centrality of religion in human experience and the contributions of religious communities and traditions in informing a more integrative vision of human development. This broad multidimensional approach accords with the idea of Integral Human Development as articulated in modern Catholic social teaching and as embodied in the mission of the Keough School of Global Affairs .

Kellogg endeavors to unite rigorous social science research with normative and theoretical reflections on human development, dignity, and flourishing. Advancing multi-disciplinary research, both quantitative and qualitative, the Institute supports innovative methodologies that consider the concept and process of human development and engage and enrich the experiences of local communities. Its research seeks to inform sustainable development practices and to generate policy-relevant insights about the respective roles and responsibilities of institutions, policies, and laws at stake in global development.

Research on this theme includes:

- Public policies for social justice and ecological responsibility, examining the way social policy, market activities, and social change combine to affect the distribution of wealth, opportunity, and quality of life;

- Economic growth, development, and human welfare in a globalizing economy, considering the roles of economic institutions, government policies, market structures, distributional issues, international trade and finance, and economic geography;

- Political, social, and cultural institutions of development, and the way in which culture, social movements, and religious beliefs influence social change;

- The concept and content of “development,” as informed by engagement with local communities and investigating the harms of development paradigms and projects that inadequately account for local contexts, cultures, and traditions;

- Human rights and their relationship with improvements in human welfare, human vulnerabilities, and basic needs;

- Global health, including issues of public health, health delivery, and policy and practice at local, regional, national, and international levels;

- Education, examining policy, institutions, innovative programs, and practice at the macro and micro levels;

- Technology and the environment, examining the impact of technological adaptation and the complex interactions between development and growth, natural ecologies, and environmental concerns.

human development Research and Discussion

Research on Human Development

Kellogg Institute scholars advance the understanding of human development through sharing their research findings and expert analyses in various media.

Insurgent and Rural-Poor Collective Action and Land Redistribution in War-to-Peace Transitions

Kellogg Connections Foster Interdisciplinary Community Among Scholars of the Middle East

“A Force for Good”: IDS Student Studies Girls’ Vocational Education

Former International Scholars Bring Development Skills to a World in Need

Guide: A World of Differences: The Science of Human Variation Can Drive Early Childhood Policies and Programs to Bigger Impacts