Definition of 'research student'

Research student in british english.

Examples of 'research student' in a sentence research student

Trends of research student

View usage for: All Years Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

Browse alphabetically research student

- research scholarship

- research scientist

- research shows

- research student

- research study

- research subject

- research suggests

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'R'

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

- What is Undergraduate Research?

- Mission and History

- Strategic Plan

- Board of Directors

- CUR Divisions

- Committees + Task Forces

- Nominations & Elections

- Key Documents

- Year In Review

- Code of Conduct

What Is CUR’s Definition of Undergraduate Research?

Undergraduate research, scholarship, and creative inquiry is fundamentally a pedagogical approach to teaching and learning. With an emphasis on process, CUR defines undergraduate research as: A mentored investigation or creative inquiry conducted by undergraduates that seeks to make a scholarly or artistic contribution to knowledge.

What Are the Benefits of Undergraduate Research?

- Enhances student learning through mentoring relationships with faculty

- Increases retention and graduation in academic programs

- Increases enrollment in graduate education and provides effective career preparation

- Develops critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving, and intellectual independence

- Develops an understanding of research methodology

- Promotes an innovation-oriented culture

- Develops competencies that speak to career-readiness

How Does CUR Support Undergraduate Research?

CUR, incorporated in 1980, is an organization of individual, institutional, and affiliate members from around the world. CUR members share a focus on providing high-quality and collaborative undergraduate research, scholarly, and creative activity opportunities for faculty and students. CUR believes that faculty members enhance their teaching and contribution to society by remaining active in research and by involving undergraduates in research and that students engaged in undergraduate research succeed in their studies and professional advancement.

Among the many activities and networking opportunities that CUR provides, the organization also offers support for the professional growth of faculty and administrators through expert-designed institutes, conferences, and a wide range of volunteer positions. The CUR community continues to provide a platform for discussion and other resources related to mentoring, connecting, and creating relationships centered around undergraduate research. CUR’s advocacy efforts are also a large portion of its work as we strive to strengthen support for undergraduate research. Its continued growth in connections with representatives, private foundations, government agencies, and campuses worldwide provides value to its members and gives voice to undergraduate research.

CUR is committed to inclusivity and diversity in all its activities and our community.

We are your resource. We are the community. We are mentoring. We are CUR.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of research

(Entry 1 of 2)

Definition of research (Entry 2 of 2)

transitive verb

intransitive verb

- disquisition

- examination

- exploration

- inquisition

- investigation

- delve (into)

- inquire (into)

- investigate

- look (into)

Examples of research in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'research.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle French recerche , from recercher to go about seeking, from Old French recerchier , from re- + cerchier, sercher to search — more at search

1577, in the meaning defined at sense 3

1588, in the meaning defined at transitive sense 1

Phrases Containing research

- marketing research

- market research

- operations research

- oppo research

research and development

- research park

- translational research

Dictionary Entries Near research

Cite this entry.

“Research.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/research. Accessed 6 Jun. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of research.

Kids Definition of research (Entry 2 of 2)

More from Merriam-Webster on research

Nglish: Translation of research for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of research for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about research

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

What's the difference between 'fascism' and 'socialism', more commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, the words of the week - may 31, 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, etymologies for every day of the week, games & quizzes.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of research in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- He has dedicated his life to scientific research.

- He emphasized that all the people taking part in the research were volunteers .

- The state of Michigan has endowed three institutes to do research for industry .

- I'd like to see the research that these recommendations are founded on.

- It took months of painstaking research to write the book .

- absorptive capacity

- dream something up

- modularization

- nanotechnology

- technologist

- the mother of something idiom

- think outside the box idiom

- think something up

- study What do you plan on studying at university?

- major US She majored in philosophy at Harvard.

- cram She's cramming for her history exam.

- revise UK I'm revising for tomorrow's test.

- review US We're going to review for the test tomorrow night.

- research Scientists are researching possible new treatments for cancer.

- The amount of time and money being spent on researching this disease is pitiful .

- We are researching the reproduction of elephants .

- She researched a wide variety of jobs before deciding on law .

- He researches heart disease .

- The internet has reduced the amount of time it takes to research these subjects .

- adjudication

- have the measure of someone/something idiom

- interpretable

- interpretive

- reinspection

- reinterpret

- reinterpretation

- reinvestigate

- reinvestigation

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

Related word

Research | american dictionary, research | business english, examples of research, collocations with research.

These are words often used in combination with research .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of research

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

any of the rods that join the edge of a wheel to its centre, so giving the wheel its strength

Worse than or worst of all? How to use the words ‘worse’ and ‘worst’

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun Verb

- Business Noun Verb

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

To add research to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add research to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Advertisement

What Constitutes Student Well-Being: A Scoping Review Of Students’ Perspectives

- Published: 16 November 2022

- Volume 16 , pages 447–483, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Saira Hossain ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5549-9174 1 ,

- Sue O’Neill ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2616-4404 1 &

- Iva Strnadová ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8513-5400 1

10k Accesses

10 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Student well-being has recently emerged as a critical educational agenda due to its wide-reaching benefits for students in performing better at school and later as adults. With the emergence of student well-being as a priority area in educational policy and practice, efforts to measure and monitor student well-being have increased, and so has the number of student well-being domains proposed. Presently, a lack of consensus exists about what domains are appropriate to investigate and understand student well-being, resulting in a fragmented body of work. This paper aims to clarify the construct of student well-being by summarising and mapping different conceptualisations, approaches used to measure, and domains that entail well-being. The search of multiple databases identified 33 studies published in academic journals between 1989 and 2020. There were four approaches to conceptualising student well-being found in the reviewed studies. They were: Hedonic, eudaimonic, integrative (i.e., combining both hedonic and eudaimonic), and others. Results identified eight overarching domains of student well-being: Positive emotion, (lack of) Negative emotion, Relationships, Engagement, Accomplishment, Purpose at school, Intrapersonal/Internal factors, and Contextual/External factors. Recommendations for further research are offered, including the need for more qualitative research on student well-being as perceived and experienced by students and for research to be conducted in a non-western context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Modifying the PERMA profiler to assess student well-being

Is Teachers’ Well-Being Associated with Students’ School Experience? A Meta-analysis of Cross-Sectional Evidence

Well-Being in International Large-Scale Assessments

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Promoting student well-being has recently emerged as a critical educational agenda for educational systems worldwide due to its wide-reaching benefits (Joing et al., 2020 ). Student well-being can be considered an enabling condition for successful learning in school and an essential outcome of 21st-century education (Govorova et al., 2020 ). Students with a higher sense of well-being perform better at school and later on as adults by gaining employment, leading a socially engaged life, and contributing to the nation (Cárdenas et al., 2022 ; O’Brien & O’Shea, 2017 ; Price and McCallum, 2016 ). Although the importance of student well-being has been recognised unequivocally (Tobia et al., 2019 ), researchers have not reached a shared understanding of what student well-being entails. Researchers, however, all agree that it is a multidimensional concept incorporating multiple domains (Danker et al., 2019 ; Soutter et al., 2014 ; Svane et al., 2019 ).

With the emergence of student well-being as a priority area in educational policy and practice, efforts to measure and monitor student well-being have increased (Svane et al., 2019 ), along with the number of student well-being domains being proposed. Presently, a lack of consensus exists about what set of domains is appropriate to investigate and understand student well-being, resulting in a fragmented body of work (Danker et al., 2016 ; Svane et al., 2019 ). Such a lack of consensus is a significant barrier to developing, implementing, and evaluating programs to improve students’ well-being. The proliferation of proposed domains is often due to the variation in conceptualising the construct. Different conceptualisations lead to the selection of different domains.

Historically, the concept of well-being has been built upon two distinct philosophical perspectives: the hedonic and eudaimonic views. Those who favour a hedonic view conceptualise well-being as the state of feeling good and focus on cognitive and affective domains (Keyes & Annas, 2009 ). The cognitive domain represents satisfaction with school and life, whereas, the affective domain represents school-related positive (e.g., joy) and negative affect (e.g., anxiety). Proponents of the eudaimonic view often conceptualise well-being as functioning well at school and focus on a range of domains representing optimal student functioning, such as school engagement (Thorsteinsen & Vittersø, 2018 ). However, neither a hedonic nor eudaimonic view alone can comprehensively capture or assess the complex nature of student well-being (Thorsteinsen & Vittersø, 2018 ). This shortcoming might result in excluding important domains in evaluating the construct. An integrative mapping of available domains in the existing literature is needed to develop a more holistic measure of student well-being at school.

Differences in proposed domains are not entirely due to differences in underpinning theory. Domains representing similar concepts are often labelled differently in different studies, i.e., ‘relating to peers’ is labelled as ‘classroom connectedness’ by Mameli et al. ( 2018 ), whereas Lan and Moscardino ( 2019 ) labelled it as ‘peer relationship’. This variation muddies the measuring and monitoring of the construct, making it difficult to compare the results from study to study, build on the work of others, and ensure the inclusion of the domains that matter. There is a need for an integrative understanding of the domains available in the existing literature to target the most critical domains for holistic student well-being and provide effective intervention to support the domains in which students need the most support. It is also more critical than ever before, as currently, the well-being of school-aged students is grossly affected by the global pandemic COVID-19 (Dean Schwartz et al., 2021 ; Golberstein et al., 2019 ; Van Lancker & Parolin, 2020 ). Therefore, it is timely to conduct an integrative review to map the domains of student well-being to assist in measuring the construct and targeting supports and resources to bolster it.

Although past efforts have reviewed the existing literature on student well-being, their purposes have varied. Fraillon ( 2004 ) sought to identify the domains of student well-being to develop a reliable instrument for measuring the construct. Fraillon’s identified domains favoured the eudaimonic viewpoint. She operationalised student well-being as their effective student functioning in school. Later, Noble et al. ( 2008 ) focused on mapping pathways (e.g., strength-based approach) to achieving student well-being. However, it is ambitious to achieve student well-being leaving aside the question of what constitutes the construct of student well-being. Danker et al. ( 2016 ) reviewed the existing literature to locate domains specifically relevant to the well-being of students with autism. More recently, Govender et al. ( 2019 ) did a systematic review on South African young people’s well-being, but their review focused on well-being in a general life context. None of the above studies sought to review the domains or indicators of student well-being, mainly focusing on the school context and exploring students’ perspectives. The limit in the scope of the previous reviews indicates the gap for an integrative review to map the body of evidence on domains of student well-being. This review aims to map students’ perspectives regarding the domains of student well-being available in the existing literature to provide an integrative understanding of the construct. The following research questions guide the study:

How has student well-being been conceptualised in previous studies?

What approaches have been taken to measure student well-being?

What domains of student well-being have been perceived by the students in previous studies?

This study follows a scoping review methodology allowing for a broader and more exploratory approach to mapping a topic of interest (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 ; Levac et al., 2010 ). We chose a scoping review as it is suitable for identifying factors related to a concept (Munn et al., 2018). This review is informed by the methodological framework developed by Arksey & O’Malley ( 2005 ), which adds methodological rigour to systematic reviews. It follows a step-by-step, rigorous, transparent, and replicable procedure for searching and summarising the literature to ensure the reliability of the findings (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 ; Levac et al., 2010 ).

This scoping review included the following stages: (a) identifying relevant studies through a search strategy; (b) selecting the studies that meet inclusion criteria; (c) assessing the quality of data; and (d) charting the data, summarising, and reporting the results. Scoping reviews do not necessarily involve data quality assessment, but we carried out this step to ensure the quality of research evidence included in the domain mapping.

2.1 Identifying Relevant Studies

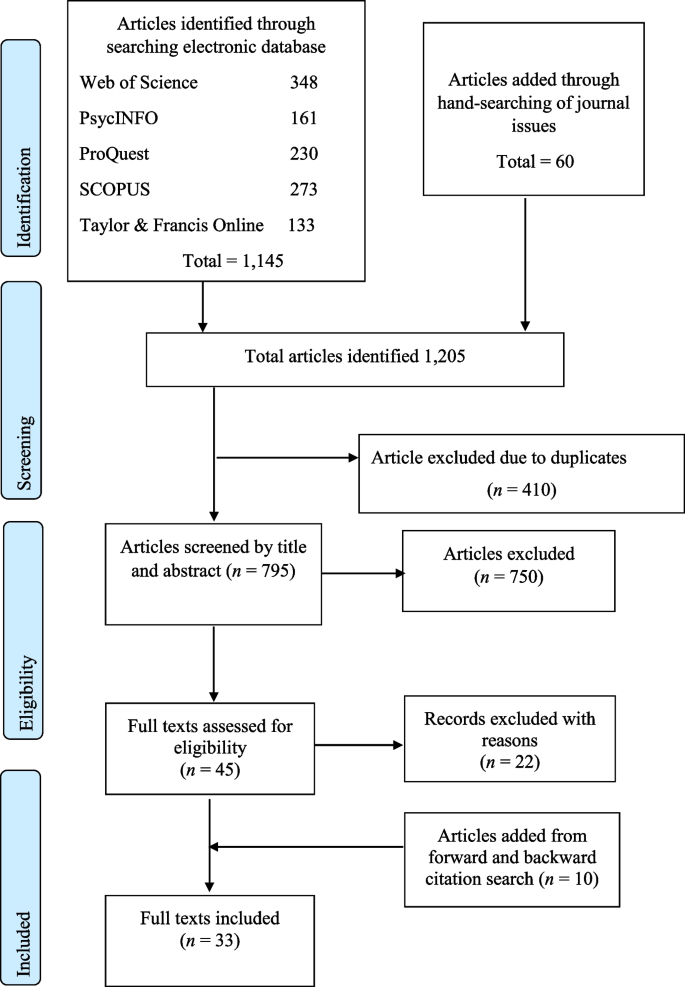

Given the broader aim and coverage of a scoping review, a comprehensive approach was required to locate the relevant studies, to answer the research questions. The search involved three key sources: electronic databases, hand-searching key journals in the field, and ancestral searches of relevant article reference lists. For manageability reasons, the scoping review did not include grey literature and restricted the search to articles written in English. The identification of relevant studies is not linear but an iterative process. Hence, we adopted a reflexive, flexible, and broad approach to defining, redefining, changing, and adding search terms to generate comprehensive coverage. The initial search terms and relevant electronic databases were identified through consultations between the first author and a research librarian at the authors’ institution. The search strategy and results were informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Moher et al., 2009 ).

A keyword search was conducted using five electronic databases: ProQuest, PsycINFO, Scopus, Taylor & Francis Online, and Web of Science. Boolean operators were used to conducting the searches (see Table 1 for search terms). All the database searches were limited to English-language peer-reviewed articles, with abstracts published from November 1989—2020. The start date represents the enactment of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations [UN], 1989 ) when the concept of children’s well-being gained increasing international attention.

A hand search was conducted of eight journals from our database search that commonly publish research on student well-being at school to locate potentially relevant articles missed in the database search (Levac et al., 2010 ). The eight journals included: Child Indicators Research, Social Indicators Research, Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, Journal of Youth and Adolescence, Journal of Happiness Studies, School Mental Health, School Psychology Review , and School Psychology Quarterly. As a final step for locating relevant studies, a backward and forward citation search was conducted with the publications identified from the database and a hand search for full-text assessment (Briscoe et al., 2020 ; Wright et al., 2014 ).

2.2 Selecting the Studies

The initial literature search yielded a total of 1,205 articles for further screening. A total of 410 duplicate articles were removed (see Fig. 1 ). The authors devised inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure that only articles relevant to the aim of the scoping review were selected (see Table 2 ). The titles and abstracts of the 795 novel articles were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria independently by the first and second authors, resulting in 45 articles retained for full-text screening. The full text of the 45 articles was examined against the inclusion criteria independently by the first and second authors to assess eligibility resulting in the exclusion of 22 of them.

Flow Diagram of Search Results

As a final step, the authors subjugated the 23 retained articles for backward and forward citation searching independently by the first and second authors yielding another ten relevant articles resulting in 33 papers included in the data charting and extraction stage. Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) with 95% confidence intervals was calculated to determine the interrater reliability score for screening stages: κ = 0.82 for the first stage, 0.85 for the second stage, and 0.89 for the third stage, which can be interpreted as almost perfect agreement (McHugh, 2012 ). The third author resolved any disagreement between the first and second authors.

2.3 Assessing the Quality of the Data

We assessed the quality of the included articles using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields (Kmet et al., 2004 ). Kmet et al. ( 2004 ) proposed two checklists: one for quantitative and the other for qualitative studies. Example assessment criteria for the quantitative studies included: the study objectives/research questions, justification and detail reported in the study design, and analytic methods. Example assessment criteria for the qualitative studies included connection to a theoretical framework/wider body of knowledge, clear description and systematic data collection and analysis method, credibility, and reflexivity of the account.

All 33 articles were independently scored by the first and second authors based on three criteria — whether they met the tool’s assessment criteria, met them only partially, or not at all. The yielded scores for each criterion were summated and converted into percentages to allow comparison. The quality scores ranged from 77—100%, which can be interpreted as strong according to McGarty and Melville ( 2018 ), indicating a high quality of research evidence. The inter-rater reliability of this process was high at κ = 0.92 (Cohen, 1960 ; McHugh, 2012 ). The third author resolved any disagreement.

2.4 Charting Data, Summarising, and Reporting Results

This step involves extracting the information relevant to the scoping review from the selected articles. A structure template was used to extract information as follows: author details, year of publication, characteristics of the sample (size, age, and gender ), study location, research design, measure/ data collection instrument and domains or indicators of well-being (Levac et al., 2010 ). The first and second authors coded the studies independently with a high level of agreement (κ = 0.89) (Cohen, 1960 ; McHugh, 2012 ).

3.1 Overview of the Selected Studies

About 58,910 students participated in the studies, ranging from 16 to 10,913. Most of the student participants were from regular primary or secondary schools. However, participants in two studies, Mameli et al. ( 2018 ) and Van Petegem et al. ( 2008 ), were from technical or vocational secondary schools. The age of the participants ranged from 6 to 19 years. Most ( n = 16) of the studies focused on post-primary grade levels, with half including participants from middle school levels. In contrast, only two studies, one from China (Lan & Moscardino, 2019 ) and the other from Ireland (Miller et al., 2013 ), included participants only from primary grade levels. Five of the studies had participants from both primary and secondary grade levels. About one-third of the studies ( n = 10) did not report any information regarding participating students’ grade levels. The number of female and male student participants was reported in 16 studies, with 53.48% being female (see Table 3 ). One study focused on students with autism enrolled in regular schools (Danker et al., 2019 ). Two studies were multi-perspective, including students, parents, principals, and teachers (Anderson & Graham, 2016 ; Tobia et al., 2019 ).

European countries dominated the research location from the 33 studies included in the analysis, accounting for 18 out of the 33 studies (see Table 3 ). There were eight studies from China and three from Australia. Three studies were multi-country: Opre et al. ( 2018 ), Hascher ( 2007 ), and Donat et al. ( 2016 ). The dates of the studies ranged from 2004 to 2020, with 26 studies published since 2015. More than two-thirds were published within the last five years, indicating growing student well-being research popularity.

3.2 Approaches to Assessing Student Well-Being

The approaches to measuring student well-being in the reviewed studies were quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Quantitative research methods dominated the research in this review, with 27 of the 33 studies solely using this method. In 30 of the 33 studies, self-reported survey measures were used, using cross-sectional and longitudinal designs (see Table 3 ). Three studies followed a qualitative, and one study followed a mixed-methods approach. Hascher ( 2007 ) and López-Pérez and Fernández-Castilla ( 2018 ) used quantitative and qualitative data collection but did not explicitly follow a mixed-methods study design.

Most of the quantitative measurement instruments used in the articles reviewed here were multidimensional, with sub-scales consisting of multiple items derived from one or more existing well-being scales. For example, McLellan and Steward ( 2015 ) adapted items from the European Social Survey (Huppert et al., 2009 ) for use with young people in school settings and drawing on Every Child Matters (Department for Education & Skills, 2003 ) from the UK. Few studies used multidimensional instruments that developed scales dedicated explicitly to measuring student well-being at school instead of adapting general well-being scales within the school context (e.g., Anderson & Graham, 2016 ; Engels et al., 2004 ; Hascher, 2007 ; Tian, 2008 ). Only López-Pérez and Fernández-Castilla ( 2018 ) and Wong and Siu ( 2017 ) used single items to measure school happiness.

Most instruments were developed from an adult perspective, that of the researchers. However, students were consulted in four studies before creating the scale items. Anderson and Graham ( 2016 ) set up a well-being advisory group of students, teachers, and other stakeholders to elicit their conceptualisations of well-being and their conception of an imaginary school. Opre et al. ( 2018 ) conducted separate focus group interviews with adolescents, parents, and teachers to identify and operationalise the sub-components of student well-being. Engels et al. ( 2004 ) used panel discussions with secondary students to identify the aspects of school and classrooms as learning environments that students perceived were relevant to their well-being. Kern et al. ( 2015 ) asked students and pastoral staff about what they wanted to know about their well-being as an indicator of what was essential for student well-being. Feedback on the suitability of items from students and teachers was sought by McLellan and Steward ( 2015 ) after they derived items from policy and other scales. Seeking stakeholder feedback enhances the content validity of instruments (Stalmeijer et al., 2008 ).

Most instruments reviewed here had acceptable reliability and good model fit. About 24 of the 30 self-report instruments had reliability ranging from Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.70 to 0.95: an acceptable value for scale reliability (Hair et al., 2018). Most studies used factor analysis to determine the factor structure of student well-being instruments, with two exceptions. Mameli et al. ( 2018 ) and Tong et al. ( 2018 ) developed sub-scales to measure student well-being indicators derived from operationalising the construct.

In the three qualitative studies, stakeholder inputs provided a deeper insight into student well-being. Soutter ( 2011 ) used drawing, walk-about discussion, and small-group work to elicit students’ understanding of well-being at school. She also developed a conceptual framework comprising domains of student well-being based on a thorough transdisciplinary literature review on well-being which she used to analyse and interpret data in her study. Hidayah et al. ( 2016 ) conducted focus group discussions using unstructured and open-ended questions with 42 secondary students in Indonesia following the School Well-being Model developed by Konu and Lintonen ( 2006 ). Danker et al. ( 2019 ) adopted an advisory participatory research method and a grounded theory approach. They used semi-structured interviews and photovoice to gain insight into well-being experiences, barriers, and facilitators of well-being for students with autism.

3.3 The Conceptualisation of Student Well-Being

There were four approaches to conceptualising student well-being found in the reviewed studies. They were hedonic, eudaimonic, integrative (i.e., combining both hedonic and eudaimonic), and other (see Table 4 ). All the reviewed studies, irrespective of their conceptualisation approach, represented well-being in terms of different indicators: those aspects needed to ensure a good level of student well-being.

A hedonic view was evident in 16 of the 33 studies (See Table 4 ). These studies mainly adopted Diener’s ( 1984 ) theory of subjective well-being within the domain-specific context of school (e.g., Liu et al., 2016 ). Hedonic-aligned definitions tended to be relatively homogeneous, with researchers defining student well-being as the subjective, cognitive, positive appraisal of school life that emerges from the presence of positive feelings such as happiness and the absence of negative feelings such as worry. Both the cognitive (e.g., school satisfaction) and affective components (e.g., joy) were evident. The connotation of positive feelings about school was common, with some defining positive feelings as the harmony between student characteristics and the characteristics of the school (e.g., Engels et al., 2004 ).

Three studies reflected eudaimonic views and conceptualised student well-being as functioning effectively within the school context (See Table 4 ). There was greater variation in how the concept was defined, with effective functioning represented as school connectedness, engagement, educational purpose, and academic efficacy (Arslan & Renshaw, 2018 ). The reviewed studies using eudaimonic aligned definition mainly followed Ryff ( 1989 )’s Psychological well-being theory which conceptualises well-being as a psychological phenomenon comprising six dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. However, none of the reviewed studies included all the six dimensions of eudaimonic well-being. For example, Holfve-Sabel ( 2014 ) focuses on learning and positive relationships.

Eleven studies took an integrative approach. They combined hedonic and eudaimonic views to conceptualise student well-being (See Table 4 ). Most of these studies provided an ad hoc definition of student well-being based on different indicators, including hedonic and eudaimonic aspects. For instance, Mameli et al.( 2018 ) represented student well-being in terms of emotional attitude (e.g. emotional engagement) and social relationship (e.g., school connectedness) indicators. Whereas, Kern et al. ( 2015 ) took a more holistic viewpoint and adopted Seligman’s PERMA theory of human flourishing within the school context, including five indicators such as positive emotion (P), engagement (E), relationships (R), meaning (M), and achievement (A). Three studies fell under the other category. Two of them took the need satisfaction approach and viewed well-being as a state that results from the satisfaction of three needs: having, loving, and being, as suggested by Allardt ( 2003 ). Here, having referred to material and impersonal needs, it also included the need for good health, loving refers to the need to relate to others, and denoting the need for personal growth. Konu et al.’s ( 2015 ) quantitative study in Finland and Hidayah et al.’s ( 2016 ) qualitative study conceptualised well-being in terms of four indicators reflecting the three needs (see Table 4 ). Only one study by Anderson and Graham ( 2016 ) used recognition theory to conceptualise student well-being in terms of three aspects of recognition: cared for, respected and valued.

3.4 Domains of Student Well-Being Explored in Previous Studies

Irrespective of the theoretical perspective adopted, 29 of the 33 studies used instruments with subscales to measure student well-being as a multidimensional concept. Ninety-one domains of well-being were identified from the well-being instruments, with an additional 21 extracted from the qualitative studies, resulting in a total of 112. We observed that different terms were used in the 33 studies reviewed to refer to the domains identified, although their descriptions were often similar. Hence, a coding scheme was developed to recategorise the domains extracted from the 33 studies (see Table 5 ). By analysing the items under each domain and examining their qualitative descriptions, all 112 domains were coded independently by the first and second author and recategorised into eight overarching domains following the coding scheme. Good interrater reliability of Cohens κ = 0.97 (Cohen, 1960 ; McHugh, 2012 ) was also found at this stage.

The eight derived overarching domains included positive emotion, lack of negative emotion, relationships, engagement, accomplishment, a sense of purpose in school, intrapersonal/ internal factors, and contextual/ external factors. The number of domains included per study ranged between two and eight.

3.4.1 Positive Emotions

Positive emotion is about feeling good at school and reflects a hedonic view of well-being. About two-thirds of the studies (24/33) in this review included at least one domain of positive emotion, such as joy or school satisfaction (see Table 6 ). School satisfaction was the most measured aspect of positive emotion, regardless of how it was labelled.

3.4.2 (lack of) Negative Emotions

The absence of negative emotions such as stress, worry, anxiety, or cynicism was used as a proxy for well-being and was evident in 16 of the 33 studies (see Table 6 ). It was commonly measured alongside positive emotion, except in two studies. Scrimin et al. ( 2016 ) assessed school-related anxiety and academic stress. Tong et al. ( 2018 ) measured depressive symptoms and student stress using specific subscales for academic stress, efficacy stress, and self-focused stress.

3.4.3 Relationships

This domain refers to students’ perceptions and feelings about meaningful relationships with peers, teachers, family and the school as an institution/community. It was the most dominant and was evident in 26 of the 33 studies (see Table 6 ). Under this domain, we included school connectedness, teacher-student, and peer-peer relationships (see Table 5 for coding sceme). The majority included positive relationships either with teachers or peers. Soutter ( 2011 ) viewed the relationship domain not only as relating to family-peers-teachers-school but also to the purpose of one’s life.

3.4.4 Engagement

This domain included behavioural, cognitive, and affective involvement with the school and was evident in 14 out of 33 studies (see Table 6 ). Cognitive and emotional engagement, interest in learning tasks, looking after self and others, attitude towards homework, and means of self-fulfilment were included here as they referred to students’ involvement in curricular and extra-curricular activities at school. We had academic well-being in the engagement domain from the study by Danker et al. ( 2019 ), referring to students’ qualitative accounts of learning in their favourite subjects at school, doing homework, and how they learn best.

3.4.5 Accomplishment

This domain referred to students’ perceived academic self-concept. Twelve of the 33 studies included a sense of accomplishment. Again, this domain was viewed in many ways, such as academic efficacy/competence, positive academic self-concept, and self-assessment of completing the task. Butler and Kern ( 2016 ) saw it as “working toward and reaching goals, mastery and efficacy to complete tasks” (p. 4). We noted a lack of domains that included non-academic accomplishments such as a sport or the arts.

3.4.6 Purpose at School

This domain represented students’ belief about the purpose or value of schoolwork to their present or future life and was evident in 4 of the 33 studies. This domain was referred to in diverse terms in the studies reviewed, including educational purposes, learning, personal development, striving, and well-being (see Table 5 for the coding scheme).

3.4.7 Intrapersonal/Internal Factors

About 10 of the 33 studies included this domain (see Table 6 ). This overarching domain is concerned with those aspects that manifest students’ internalised sense of self, such as emotional regulation, that help them experience well-being at school (Fraillon, 2004 ). Self-esteem (Miller et al., 2013 ) and self-efficacy (Tobia et al., 2019 ) were also coded as intrapersonal, as were opportunities to make an autonomous decision (Mascia et al., 2020 ) as items referred to students’ sense of self-regulation at school. Among the qualitative findings, Soutter’s ( 2011 ) “being” domain was categorised as intrapersonal as it represents personal agency, identity, independence, and the way one is comfortable with or wants to be .

Included in this overarching domain were mental and physical health as they are related to intrapersonal. Physical health was found in four studies, such as the absence of physical complaints (Hascher, 2007 ; Morinaj & Hascher, 2019 ), Health status (Hidayah et al., 2016 ; Konu et al., 2015 ), and Being healthy (Anderson & Graham, 2016 ) (See Table 6 ). Only two studies referred to students’ mental health. Wong and Siu ( 2017 ) and Kern et al. ( 2015 ) assessed the absence of depressive symptoms and depression as indicators of student well-being, respectively.

3.4.8 Contextual/ External Factors

This domain was included in 6 of the 33 studies (see Table 6 ). External factors cover all domains representing resources inside and outside of the school available for students to support their well-being. It includes but is not limited to physical and material resources, tools, and opportunities. From analysing the instruments used, the following external resources were used to measure student well-being: school conditions (Hidayah et al., 2016 ; Konu et al., 2015 ), current living conditions, and availability of assistance (Mascia et al., 2020 ). Similarly, the Having domain from Soutter’s ( 2011 ) qualitative study referred to getting access to opportunities, tools, and resources, with Anderson and Graham ( 2016 ) reporting that having a great environment, having a say, and having privacy indicated student well-being at school. It included physical and material resources, tools, school conditions or environment, current living conditions, and availability of assistance (see Table 5 for the coding scheme). Soutter’s ( 2011 ) Having domain was included here as it referred to access to opportunity, tools, and resources.

4 Discussion

4.1 measuring student well-being.

All but three studies in our review took a quantitative approach and used self-report surveys to measure student well-being. The majority of the measurement instruments had acceptable to good reliability scores. However, depending on what domains the instrument items reflect, they may not have holistically captured the construct of student well-being at school. Further, a few measurement instruments (e.g., SWBQ by Hascher, 2007 ) were used and validated in more than one study or geographic location, which raises validity and generalisation issues.

Few studies in this review reported a systematic approach to developing, validating, and piloting their instruments, optimising psychometric properties. The scales of Renshaw ( 2015 ) and Opre et al. ( 2018 ) are exceptions. Further, few sought inputs from the population of interest; the students. Adapting existing measurement instruments designed to measure adults’ or children’s well-being in general for the school context was common and less onerous than developing and testing a new instrument (Boateng et al., 2018 ). School, however, is a unique context, and general measures of well-being might not capture the nuances of well-being for students at school (Joing et al., 2020 ).

The reviewed studies seldom used qualitative and Mixed methods approaches despite the richness of data on participants’ perspectives and experiences from such research designs (Aarons et al., 2012 ; Creswell, 2013 ). This finding is consistent with the literature review undertaken by Danker et al. ( 2016 ). In this review, Three studies investigated student well-being via qualitative means (Danker et al., 2019 ; Hidayah et al., 2016 ; Soutter, 2011 ). More qualitative studies are needed to understand the students’ perspectives better. Further, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches is an effective way to improve the construct validity of research instruments, as Anderson and Graham ( 2016 ) did.

4.2 Conceptualising Student Well-Being

We identified significant variability in the conceptualisation of the term student well-being. Studies focused on measuring student well-being rather than conceptualising or defining the construct. Despite no unanimously accepted definition, all researchers conceptualised it as a multidimensional and context-dependent construct. Positive emotion and feeling (e.g., joy) in the school environment seemed to be the core element shared by all definitions, reflecting a hedonist view of well-being. Although explicit to different degrees, another common element in the conceptualisations reviewed was students’ subjective perceptions, appraisal, and evaluation of their school experience. Some conceptualisations reflected the eudaimonic view and included students’ realisation of their potential and effective functioning, typically academic learning in the classroom and within the social community. In considering the common elements across the identified definitions in the studies reviewed here, we propose a more holistic definition of student well-being as the subjective appraisal of a student’s school experience emerging from but is not limited to, positive over negative emotions, the satisfaction of individual needs, effective academic, social, and psychological functioning at school to pursue valued goals, and having access to internal and external factors.

4.3 Domains of Student Well-Being

The eight overarching domains we identified are consistent with findings reported in reviews by Fraillon ( 2004 ) and Danker et al. ( 2016 ). Fraillon ( 2004 ) identified the intrapersonal and relationship domain, whereas positive emotion, lack of negative emotion, engagement, accomplishment, relationships, intrapersonal, and having access to external resources were found in Danker et al.’s ( 2016 ) review. This review identified one additional domain: a sense of purpose at school.

Among the eight domains, hedonic-aligned domains were the most common. The consistency of the hedonic conceptualisation and measurement instruments is perhaps the reason behind such hedonic domination. Commonly included domains were positive relationship and engagement, which overlap with well-researched concepts such as peer relationships, school belonging, school connectedness, and engagement at school. Peer relationships and school engagement have been well assessed, with many psychometrically sound measures developed. Therefore, it is not surprising that researchers tended to include those domains.

Conversely, less frequently included domains such as a sense of purpose at school and intrapersonal may be due to the lack of conceptual clarity and availability of current measurement instruments. Several studies included a sense of accomplishment of the other eudaimonic domains. However, the notion of accomplishment in the reviewed studies was academic performance-centric, potentially excluding non-academic accomplishments at school (e.g., sports, the arts), which are crucial for holistic development. Recent studies have started to include eudaimonic domains such as a sense of purpose and intrapersonal domains that add depth to the construct of student well-being.

Although some domains were more frequent than others, they should not be assumed to be more critical or pertinent. Using a domain due to its conceptual clarity and measurement suitability is problematic as it can narrow the scope of an inherently complex multidimensional construct like student well-being. Our review found that many studies lacked comprehensiveness regarding the domains. In 13 of the 33 studies, only two or three domains of student well-being were used to describe the whole construct. Another problem in the studies reviewed was the lack of clear reasoning behind choosing a specific domain. There might be some good reasons to have fewer domains; it is crucial to outline the reason for the selection clearly. Doing so can provide a more theoretically grounded, accurate and informative assessment of student well-being.

5 Recommendations

We offer three recommendations to researchers based on our findings. First, there is a lack of systematic development of psychometrically sound instruments for measuring student well-being. Hence, our first recommendation is that researchers develop (or adapt) valid and reliable tools explicitly to measure student well-being that follows the nine steps outlined by Boateng et al. ( 2018 ), reflecting a broader conceptualisation of student well-being discerned in this review. Further, validation of student well-being measurement instruments that are conceptually more holistic with culturally, socially, and economically diverse participants is needed to advance the field.

Second, the domains we identified in our review may provide a valuable basis for assessing students’ well-being experience at school. The theoretical and practical relevance of the domains identified in our review should be investigated in future research. For instance, researchers may examine the construct validity of these domains collectively and see the possibility of developing a psychometrically sound instrument including them. Further, these domains can serve as a guideline for designing intervention programs that facilitate student well-being at school. Future research can investigate the impact of these domains on outcomes relevant to student well-being.

Third, we identified a predominance of quantitative studies. This points to a lack of students’ qualitative accounts of their understanding of well-being at school. Qualitative accounts can also inform the quantitative findings. Hence, our third recommendation is that more research should be conducted using qualitative and mixed-method approaches.

Fourth, most research has been conducted in Western cultural contexts, with a few exceptions, such as China and India. Given that well-being is a culture-specific construct (Suh & Choi, 2018), students’ well-being experiences might be influenced by their local educational system and broader socio-cultural factors such as adult–child relationships. Thus, our final recommendation is that more qualitative and quantitative research should be conducted in non-Western cultural contexts, particularly in countries from the global South. Cross-cultural comparisons that assist in identifying universal and culture-specific domains of student well-being are warranted.

6 Limitations

This scoping review has three main limitations. Firstly, we included only peer-reviewed journal articles in English, which raises the possibility of excluding potentially relevant studies published in reports or other languages. Secondly, we only included studies that explicitly investigated students’ perspectives. Other stakeholder views, such as teachers and parents, are important to gain a complete picture of student well-being. Some studies included in this review had other stakeholder views but were not focused upon. Hence, the scope of this review in terms of providing a multi-perspective understanding of the construct is somewhat limited. Thirdly, the dominance of cross-sectional design in the studies reviewed limits the test for causalities. Finally, since most of the studies in this scoping review reflected Anglo-European student populations, caution is needed to generalise the findings to other cultures and contexts.

7 Conclusion

This review presented an overview of the conceptualisation, measurement, and domain of student well-being identified in the extant literature since 1989. We found that definitions and conceptualisation of the construct of student well-being varied. Researchers named domains found in previous studies with different labels, unnecessarily muddying the construct and leading to issues when comparing research findings. Our analysis showed that most domains reflected a hedonic view leading to a narrow line of enquiry, with some domains we identified here appearing under-researched. Based on our review of definitions and conceptualisations, we offered a more holistic explanation of student well-being to incorporate dominant and diverse views. We identified eight overarching domains from the 33 studies. We believe this is a significant advancement, bringing better clarity and demarcation of the construct. We believe the eight domains identified here encompass a wide range of school-based experiences and provide a more holistic conceptualisation of the construct of student well-being.

Aarons, G. A., Fettes, D. L., Sommerfeld, D. H., & Palinkas, L. (2012). Mixed methods for implementation research: Application to evidence-based practice implementation and staff turnover in community based organisations providing child welfare services. Child Maltreatment, 17 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559511426908

Article Google Scholar

Allardt, E. (2003). Having, Loving, Being: An Alternative to the Swedish Model of Welfare Research. The Quality of Life, 88–94 ,. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198287976.003.0008

Anderson, D. L., & Graham, A. P. (2016). Improving student wellbeing: Having a say at school. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27 (3), 348–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2015.1084336

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8 (1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156508005621

Arslan, G., & Renshaw, T. L. (2018). Student subjective wellbeing as a predictor of adolescent problem behaviors: A comparison of first-order and second-order factor effects. Child Indicators Research, 11 (2), 507–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9444-0

Asher, S. R., Hymel, S., & Renshaw, P. D. (1984). Loneliness in children. Child Development, 55 (4), 1456–1464. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1130015 .

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6 ,. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

Briscoe, S., Bethel, A., & Rogers, M. (2020). Conduct and reporting of citation searching in Cochrane systematic reviews: A cross-sectional study. Research Synthesis Methods, 11 (2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1355

Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6 (3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

Cárdenas, D., Lattimore, F., Steinberg, D., & Reynolds, K. J. (2022). Youth well-being predicts later academic success. Scientific Reports , 12 (2134). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05780-0.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 20 (1), 37–46.

Cornoldi, C., De Beni, R., Zamperlin, C., &, & Meneghetti, C. (2005). AMOS8–15 . Abilita e motivazione allo studio: Prove di valutazione per studenti dalla terza elementare alla prima superiore [Abilities and motivation to study: Assessment for students from grade 3 to grade 9 ] . https://www.erickson.it/it/test-amos-815-abilita-e-motivazione-allo-studio-prove-di-valutazione

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions . Sage Publications Inc.

Google Scholar

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., Looze, M. de, Roberts, C., Samdal, O., Smith, O. R. F., & Barnekow, V. (2012). S ocial determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study : International report from the 2009/2010 survey. Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No. 6. World Health Organization. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/163857/Social-determinants-of-health-and-well-being-among-young-people.pdf

Danker, J., Strnadová, I., & Cumming, T. M. (2016). School experiences of students with autism spectrum disorder within the context of student wellbeing: A review and analysis of the literature. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 40 (1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2016.1

Danker, J., Strnadová, I., & Cumming, T. M. (2019). Picture my well-being: Listening to the voices of students with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 89 (April), 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.04.005

Dean Schwartz, K., Exner-Cortens, D., Mcmorris, C. A., Makarenko, E., Arnold, P., Van Bavel, M., Williams, S., Canfield, R., & Psychology, A. C. (2021). COVID-19 and Student Well-Being: Stress and Mental Health during Return-to-School. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 36 (2), 166–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/08295735211001653

Department for Education and Skills. (2003). Every child matters . https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/272064/5860.pdf

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95 (3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Diener, E., Derrick, A. E., Ae, W., Tov, W., Chu, A. E., Ae, K.-P., Choi, D.-W., Shigehiro, A. E., Ae, O., Biswas-Diener, R., Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., & Oishi, S. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97 , 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Donat, M., Peter, F., Dalbert, C., & Kamble, S. V. (2016). The meaning of students’ personal belief in a just world for positive and negative aspects of school-specific well-being. Social Justice Research, 29 (1), 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-015-0247-5

Dwyer, K. K., Bingham, S. G., Carlson, R. E., Prisbell, M., Cruz, A. M., & Fus, D. A. (2004). Communication and connectedness in the classroom: Development of the connected classroom climate inventory. Communication Research Reports, 21 (3), 264–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090409359988

Engels, N., Aelterman, A., Van Petegem, K., & Schepens, A. (2004). Factors which influence the well-being of pupils in Flemish secondary schools. Educational Studies, 30 (2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569032000159787

Fraillon, J. (2004). Measuring student well-being in the context of Australian schooling: Discussion paper. The Australian Council for Educational Research. https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=well_being

Golberstein, E., Gonzales, G., & Meara, E. (2019). How do economic downturns affect the mental health of children? Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Health Economics (united Kingdom), 28 (8), 955–970. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3885

Govender, K., Bhana, A., Mcmurray, K., Kelly, J., Theron, L., Meyer-Weitz, A., Ward, C. L., & Tomlinson, M. (2019). A systematic review of the South African work on the well-being of young people (2000–2016). South African Journal of Psychology, 49 (1), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318757932

Govorova, E., Benítez, I., & Muñiz, J. (2020). How Schools Affect Student Well-Being: A Cross-Cultural Approach in 35 OECD Countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 11 ,. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00431

Harter, S. (2012). Self-perception profile for children: Manual and questionnaires. University of Denver. https://www.apa.org/obesity-guideline/self-preception.pdf

Hascher, T. (2007). Exploring students’ well-being by taking a variety of looks into the classroom. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 4 (3), 331–349.

Helms, B. J. & Gable, R. K. (1990). Assessing and dealing with school-related stress in grades 3–12 students. In Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association .

Hidayah, N. H., Pali, M., Ramli, M., & Hanurawan, F. (2016). Students’ well-being assessment at school. Journal of Educational, Health and Community Psychology , 5 (1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.12928/jehcp.v5i1.6257

Holfve-Sabel, M. A. (2014). Learning, interaction and relationships as components of student well-being: Differences between classes from student and teacher perspective. Social Indicators Research, 119 (3), 1535–1555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0557-7

Holfve-Sabel, M., & Gustafsson, J. (2007). Attitudes towards school, teacher, and classmates at classroom and individual levels: An application of two-level confirmatory factor analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 49 (2), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830500048931

Huebner, E. S. (1994). Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment, 6 (2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1037//1040-3590.6.2.149

Huppert, F. A., Marks, Æ. N., Clark, Æ. A., Siegrist, Æ. J., Stutzer, A., Vittersø, Æ. J., & Wahrendorf, Æ. M. (2009). Measuring well-being across Europe : Description of the ESS well-being module and preliminary findings. Social Indicators Research, 91 (3), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9346-0

Joing, I., Vors, O., & Potdevin, F. (2020). The subjective well-being of students in different parts of the school premises in French middle schools. Child Indicators Research, 13 (4), 1469–1487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09714-7

Kern, M. L., Benson, L., Steinberg, E. A., & Steinberg, L. D. (2016). The EPOCH measure of adolescent well-being. Psychological Assessment, 28 (5), 586–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000201

Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10 (3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936962

Keyes, C. L. M., & Annas, J. (2009). Feeling good and functioning well: Distinctive concepts in ancient philosophy and contemporary science. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4 (3), 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760902844228

Kiuru, N., Wang, M. T., Salmela-Aro, K., Kannas, L., Ahonen, T., & Hirvonen, R. (2020). Associations between adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49 (5), 1057–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01184-y

Kmet, L. M., Lee, R. C., & Cook, L. S. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields . Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) (Vol. 13, Issue February).

Konu, A., & Lintonen, T. (2006). Theory-based survey analysis of well-being in secondary schools in Finland. Health Promotion International, 21 (1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dai028

Konu, A., Joronen, K., & Lintonen, T. (2015). Seasonality in school well-being: The case of Finland. Child Indicators Research, 8 (2), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9243-9

Lam, S. F., Jimerson, S., Wong, B. P. H., Kikas, E., Shin, H., Veiga, F. H., Hatzichristou, C., Polychroni, F., Cefai, C., Negovan, V., Stanculescu, E., Yang, H., Liu, Y., Basnett, J., Duck, R., Farrell, P., Nelson, B., & Zollneritsch, J. (2014). Understanding and measuring student engagement in School: The results of an international study from 12 countries. School Psychology Quarterly, 29 (2), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000057

Lam, S., Jimerson, S., Shin, H., Cefai, C., Veiga, F. H., Hatzichristou, C., Polychroni, F., Kikas, E., Wong, B. P. H., Stanculescu, E., Basnett, J., Duck, R., Farrell, P., Liu, Y., Negovan, V., Nelson, B., Yang, H., & Zollneritsch, J. (2016). Cultural universality and specificity of student engagement in school: The results of an international study from 12 countries. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86 (1), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12079

Lan, X., & Moscardino, U. (2019). Direct and interactive effects of perceived teacher-student relationship and grit on student wellbeing among stay-behind early adolescents in urban China. Learning and Individual Differences, 69 (June 2018), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.12.003

Laurent, J., Catanzaro, S. J., Joiner, T. E., Rudolph, K. D., Potter, K. I., Lambert, S., Osborne, L., & Tamara, G. (1999). A measure of positive and negative affect for children: Scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment, 11 (3), 326–338. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1040359002001497 .

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., O’Brien, K. K., & Hacking, I. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5 (1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511814563.003

Liu, W., Mei, J., Tian, L., & Huebner, E. S. (2016). Age and gender differences in the relation between school-related social support and subjective well-Being in school among students. Social Indicators Research, 125 (3), 1065–1083. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0873-1

López-Pérez, B., & Fernández-Castilla, B. (2018). Children’s and adolescents’ conceptions of happiness at school and its relation with their own happiness and their academic performance. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19 (6), 1811–1830. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9895-5

Mameli, C., Biolcati, R., Passini, S., & Mancini, G. (2018). School context and subjective distress: The influence of teacher justice and school-specific well-being on adolescents’ psychological health. School Psychology International, 39 (5), 526–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318794226

Mascia, M. L., Agus, M., & Penna, M. P. (2020). Emotional intelligence, self-regulation, smartphone addiction: Which relationship with student well-being and quality of life? Frontiers in Psychology, 11 (March), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00375

McGarty, A. M., & Melville, C. A. (2018). Parental perceptions of facilitators and barriers to physical activity for children with intellectual disabilities: A mixed methods systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 73 (December 2017), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.12.007

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Lessons in biostatistics interrater reliability : The kappa statistic. Biochemica Medica, 22 (3), 276–282. https://www.biochemia-medica.com/assets/images/upload/xml_tif/McHugh_ML_Interrater_reliability.pdf

McLellan, R., & Steward, S. (2015). Measuring children and young people’s wellbeing in the school context. Cambridge Journal of Education, 45 (3), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2014.889659

Miller, S., Connolly, P., & Maguire, L. K. (2013). Wellbeing, academic buoyancy and educational achievement in primary school students. International Journal of Educational Research, 62 , 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2013.05.004

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151 (4), 264–269.

Morinaj, J., & Hascher, T. (2019). School alienation and student well-being: A cross-lagged longitudinal analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34 (2), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0381-1

Noble, T., McGrath, H., Wyatt, T., Carbines, R., & Robb, L. (2008). Scoping study into approaches to student well-being. Australian Catholic University and Erebus International.

Nota, L., Soresi, S., Ferrari, L., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2011). A multivariate analysis of the self-determination of adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12 (2), 245–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9191-0

O’Brien, M., & O’Shea, A. (2017). A human development framework for orienting education and schools in the space of wellbeing. https://ncca.ie/media/2488/a-human-development-framework-psp.pdf

Opdenakker, M.-C., & Damme, J. Van. (2000). Effects of schools, teaching staff and classes on achievement and well-Being in secondary education: similarities and differences between school outcomes. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 11 (2), 165–196. https://doi.org/10.1076/0924-3453(200006)11

Opre, D., Pintea, S., Opre, A., & Bertea, M. (2018). Measuring adolescents’ subjective well-being in educational context: Development and validation of a multidimensional instrument. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies, 18 (2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.24193/jebp.2018.2.20

Pell, T., & Jarvis, T. (2010). Developing attitude to science scales for use with children of ages from five to eleven years. International Journal of Science Education, 23 (8), 847–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690010016111

Pietarinen, J., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2014). Students’ emotional and cognitive engagement as the determinants of well-being and achievement in school. International Journal of Educational Research, 67 , 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2014.05.001

Price, D., & McCallum, F. (2016). Well-being in education. In F. McCallum & D. Price (Eds.), Nurturing Well-being Developing in Education (pp. 1–21). Routledge.

Renshaw, T. L. (2015). A replication of the technical adequacy of the student subjective wellbeing questionnaire. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 33 (8), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282915580885

Renshaw, T. L., Long, A. C. J., & Cook, C. R. (2015). Assessing adolescents’ positive psychological functioning at school: Development and validation of the student subjective wellbeing questionnaire. School Psychology Quarterly, 30 (4), 534–552. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000088

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57 (6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/034645

Scrimin, S., Moscardino, U., Altoè, G., & Mason, L. (2016). Effects of perceived school well-being and negative emotionality on students’ attentional bias for academic stressors. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86 (2), 278–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12104

Soutter, Anne Kathryn. (2011). What can we learn about wellbeing in school? The Journal of Student Wellbeing , 5 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.21913/jsw.v5i1.729

Soutter, A. K., O’Steen, B., & Gilmore, A. (2014). The student well-being model: A conceptual framework for the development of student well-being indicators. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 19 (4), 496–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2012.754362

Stalmeijer, R. E., Dolmans, D. H. J. M., Wolfhagen, I. H. A. P., Muijtjens, A. M. M., & Scherpbier, A. J. J. A. (2008). The development of an instrument for evaluating clinical teachers: Involving stakeholders to determine content validity. Medical Teacher , 30 (8), 272-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802258904

Svane, D., Evans, N (Snowy)., & Carter, M.-A. (2019). Wicked wellbeing: Examining the disconnect between the rhetoric and reality of wellbeing interventions in schools. Australian Journal of Education, 63 (2), 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944119843144

The KIDSCREEN Group Europe. (2006). The KIDSCREEN questionnaires: Quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents . Pabst Science Publishers.

Thorsteinsen, K., & Vittersø, J. (2018). Striving for wellbeing: The different roles of hedonia and eudaimonia in goal pursuit and goal achievement. International Journal of Wellbeing, 8 (2), 89–109. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i2.733

Tian, L. (2008). Developing scale for school well-being in adolescents. Psychological Development & Education, 24 , 100–106.

Tian, L., Chen, H., & Huebner, E. S. (2014). The longitudinal relationships between basic psychological needs satisfaction at school and school-related subjective well-being in adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 119 (1), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0495-4

Tian, L., Liu, B., Huang, S., & Huebner, E. S. (2013). Perceived social Support and school well-being among chinese early and middle adolescents: The mediational role of self-esteem. Social Indicators Research, 113 (3), 991–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0123-8

Tian, L., Tian, Q., & Huebner, E. S. (2016). School-related social support and adolescents’ school-related subjective well-Being: The mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction at school. Social Indicators Research, 128 (1), 105–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1021-7

Tian, L., Wang, D., & Huebner, E. S. (2015a). Development and validation of the Brief Adolescents’ Subjective Well-Being in School Scale (BASWBSS). Social Indicators Research, 120 (2), 615–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0603-0

Tian, L., Zhao, J., & Huebner, E. S. (2015b). School-related social support and subjective well-being in school among adolescents: The role of self-system factors. Journal of Adolescence, 45 , 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.09.003

Tobia, V., Greco, A., Steca, P., & Marzocchi, G. M. (2019). Children’s wellbeing at school: A multi-dimensional and multi-informant approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20 (3), 841–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9974-2

Tobia, V., & Marzocchi, G. M. (2015). QBS 8–13. Questionari per la valutazione del benessere scolastico e identificazione dei fattori di rischio [QBS 8–13. Questionnaires for the evaluation of school wellbeing and QBS 8–13. Questionari per la valutazione del benessere scolastico e identificaz (Issue September). Erickson.

Tong, L., Reynolds, K., Lee, E., & Liu, Y. (2018). School relational climate, social identity, and student well-being: New evidence from china on student depression and stress levels. School Mental Health, 11 (3), 509–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9293-0

United Nations [UN]. (1989). The United Nations convention on the rights of the child. https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com/99f113b4-e5f7-00d2-23c0-c83ca2e4cfa2/fc21b0e1-2a6c-43e7-84f9-7c6d88dcc18b/unicef-simplified-convention-child-rights.pdf

Van De Wetering, E. J., Van Exel, N. J. A., & Brouwer, W. B. F. (2010). Piecing the jigsaw puzzle of adolescent happiness. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31 , 923–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2010.08.004

Van Lancker, W., & Parolin, Z. (2020). COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. The Lancet Public Health, 5 (5), 243–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0

Van Petegem, K., Aelterman, A., Van Keer, H., & Rosseel, Y. (2008). The influence of student characteristics and interpersonal teacher behaviour in the classroom on student’s wellbeing. Social Indicators Research, 85 (2), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9093-7

Wong, T. K. Y., & Siu, A. F. Y. (2017). Relationships between school climate dimensions and adolescents’ school life satisfaction, academic satisfaction and perceived popularity within a Chinese context. School Mental Health, 9 (3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9209-4

Wright, K., Golder, S., & Rodriguez-Lopez, R. (2014). Citation searching: A systematic review case study of multiple risk behaviour interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-73

Yao, Y., Kong, Q., & Cai, J. (2018). Investigating elementary and middle school students’ subjective well-being and mathematical performance in Shanghai. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 16 , 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-017-9827-1

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, 2052, Australia

Saira Hossain, Sue O’Neill & Iva Strnadová

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Saira Hossain .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of/competing interests.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Ethics Approval

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hossain, S., O’Neill, S. & Strnadová, I. What Constitutes Student Well-Being: A Scoping Review Of Students’ Perspectives. Child Ind Res 16 , 447–483 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09990-w

Download citation

Accepted : 21 October 2022

Published : 16 November 2022

Issue Date : April 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09990-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scoping review

- Student well-being

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Bringing back a long extinct bird

‘The scientist is not in the business of following instructions.’

Glimpse of next-generation internet

Lessons in learning.

Sean Finamore ’22 (left) and Xaviera Zime ’22 study during a lecture in the Science Center.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Peter Reuell

Harvard Staff Writer

Study shows students in ‘active learning’ classrooms learn more than they think

For decades, there has been evidence that classroom techniques designed to get students to participate in the learning process produces better educational outcomes at virtually all levels.

And a new Harvard study suggests it may be important to let students know it.

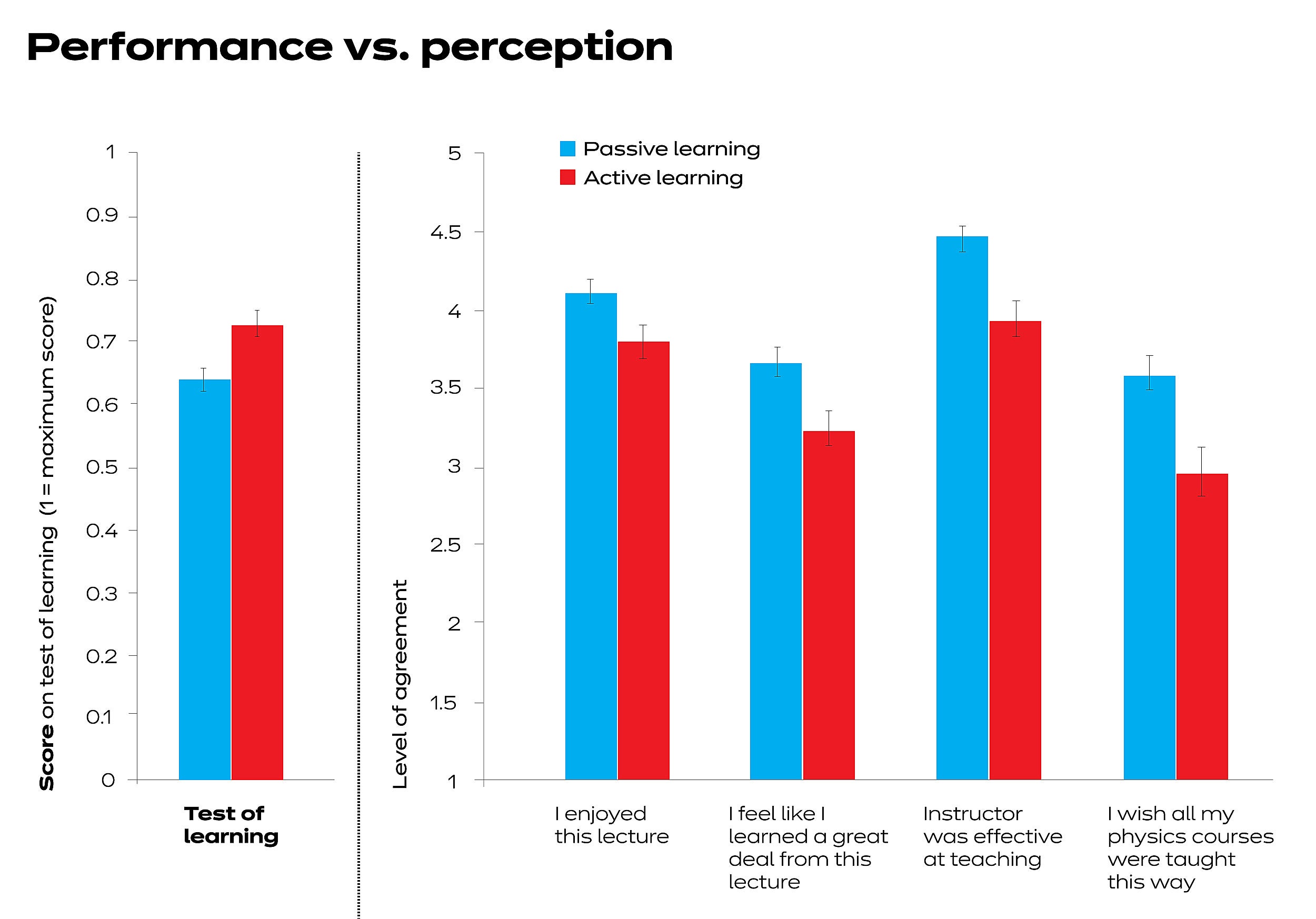

The study , published Sept. 4 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that, though students felt as if they learned more through traditional lectures, they actually learned more when taking part in classrooms that employed so-called active-learning strategies.

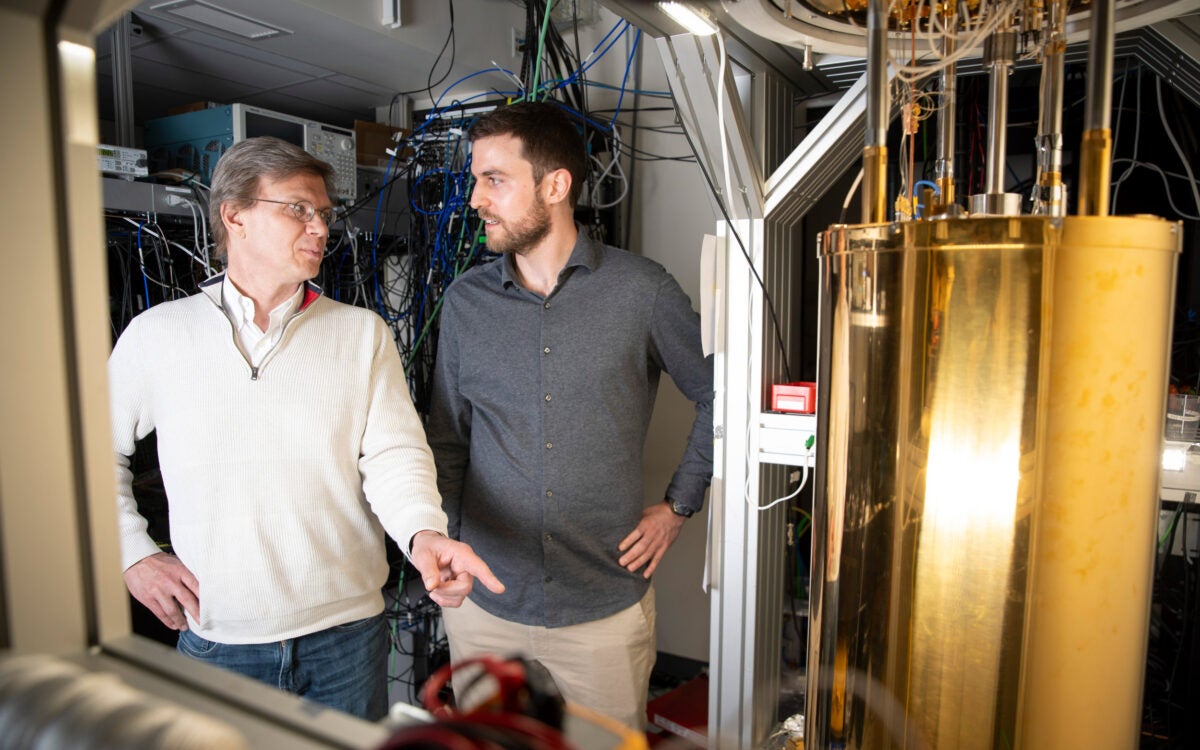

Lead author Louis Deslauriers , the director of science teaching and learning and senior physics preceptor, knew that students would learn more from active learning. He published a key study in Science in 2011 that showed just that. But many students and faculty remained hesitant to switch to it.

“Often, students seemed genuinely to prefer smooth-as-silk traditional lectures,” Deslauriers said. “We wanted to take them at their word. Perhaps they actually felt like they learned more from lectures than they did from active learning.”

In addition to Deslauriers, the study is authored by director of sciences education and physics lecturer Logan McCarty , senior preceptor in applied physics Kelly Miller, preceptor in physics Greg Kestin , and Kristina Callaghan, now a physics lecturer at the University of California, Merced.

The question of whether students’ perceptions of their learning matches with how well they’re actually learning is particularly important, Deslauriers said, because while students eventually see the value of active learning, initially it can feel frustrating.

“Deep learning is hard work. The effort involved in active learning can be misinterpreted as a sign of poor learning,” he said. “On the other hand, a superstar lecturer can explain things in such a way as to make students feel like they are learning more than they actually are.”