May 24, 2024

Goldman School of Public Policy's Official Undergraduate Public Policy Journal at UC Berkeley

Congressional Term Limits are the Key to Maintaining Our Democracy

By Michelle Tombu

T he democratic system of government in America was designed to most effectively serve the nation by vesting power in all its people. And yet it has increasingly become a weapon employed by individual politicians in fulfilling their sole objective of, first, garnering political power and then permanently remaining in it. An imposition of term limits for members of Congress has long been backed by a large majority of Americans on the impulse of fostering candid debate and forging a more progressive society – one which maintains the true integrity of our nation’s democracy. The current effects of congressional stagnation has resulted in more than 90% of House incumbents being continuously reelected year after year, with the reelection rate among Senators falling below 80% only three times total since 1982 [4]. Congressional term limits have the potential to ameliorate many of America’s most pressing political issues by “ counterbalancing incumbent advantages, ensuring congressional turnover, securing independent congressional judgment, and reducing election-related incentives for wasteful government spending” [1]. But perhaps most importantly, such a change will allow Congress to appear directly face to face with its own fragility, acquire a sense of its own transitoriness and potentially even come to learn ways in which to sustain legitimacy. Term limits are a very necessary corrective to the current political inequalities which perpetually avail incumbents and inevitably hinder their challengers.

The 22nd Amendment of the United States Constitution imposes a two term limit on all presidencies as a check on federal executive power. P residential term limits sustain the democracy of the position and ensure a single candidate does not cling on to power for an excessive period of time. Our national legislation has already appointed term limits on the office of the President in an effort to maintain political impartiality, thus it is only logical that such measures be applied to Congress as well. Some argue that congressional elections serve as inherent term limits for members of the House. This can be refuted by political campaign donors’ recognition of an incumbent candidate’s higher reelection rate and subsequent inclination to support such a campaign in an effort to yield more profit. This makes it nearly impossible for other candidates to have a chance at a fair election. In primary elections, both the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC) and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) very rarely introduce new candidates to run against incumbents. Thus, the current office-holder often becomes the sole possible nominee [2]. The approval rating of Congress ranks consistently below 20%, yet the congressional reelection rate remains over 95% because of the intrinsic advantages incumbents have over challengers, making it virtually impossible to vote them out of office. Term limits have the capacity to prevent individuals from becoming too powerful in Congress and ultimately better reflect the will of the American people. This also plays into a citizen’s constitutional right to vote by giving voters more choices at the ballot box and effectively eliminating the electoral monopoly generated by incumbent advantages. Allowing new individuals to run for office will give voters more federal autonomy and opportunities to create a personal choice.

Term limits are supported by a large majority of American demographic groups: an overwhelming 82% of Americans support a “Term Limits Amendment” for Congress, even crossing major party lines at 89% Republican, 83% Independent, and 76% Democratic, making the issue nonpartisan in itself [4]. The longstanding legislative resistance to congressional term limits stands in sharp contrast with private citizens’ strong support for them. The only serious primary opponents of term limits are incumbent politicians and the special interest groups that support them, particularly labor union groups. The extreme influence of lobbyists such as super Political Action Committees (PACs) and special interests serves as a threat to our democracy because these groups have held the financial power to sway elections and overpower the voices of others through absolutely exorbitant campaign donations. According to “Open Secrets”, 97% of corporate PAC money goes to the incumbent candidates because they are often most established and easily-influenced – l obbyists and special interest groups already have them in their back pocket [5]. Term limits would effectively break the chokehold these groups have on the members of Congress, reducing the amount of money spent on incumbent candidates and thus making our elections more democratic and just. They would aid in reducing political corruption by severing politicians’ ties with lobbyists and bureaucrats, making ex-lawmakers overall less valuable. In doing so, public service is safeguarded from those who seek to exploit it for personal benefit.

Time and time, year after year, we are represented by the same people. In 2020, both the House and Senate elections, 93% of incumbent candidates nationwide won their respective races. Such candidates have the name recognition, money, and power necessary to easily win these elections, however, they do little for their constituents and advance their own interests by gaining committee chairmanships and seniority. Bills and other legislatures are most often stalled in congressional election years when politicians are primarily focused on reelection rather than their duty to serve districts and address significant community matters. As it turns out, when members of Congress spend every waking moment of their given term consumed by the prospects of their own reelection, the concerns of the American people fall by the wayside. “As a result, all we are left with is unsolved problems and a $27 trillion national debt” [3]. When not fully invested in the matters of their own country, Congress members are forced to vote along party lines to ensure they are re-elected by their party. The introduction of term limits would create more acts of political courage. Term limits will allow the most capable lawmakers to have these positions while encouraging other members to do the same, creating a sense of ability over seniority. Term limits provide representatives who are closer to their constituents and who know they have a limited time in office to do the work they were sent there to do. They remain cognizant of the return they will make back home, where they too must live under the laws they have enacted.

Congressional incumbency is “ a paradigm of careerism, combining power, stature and influence with lavish benefits : a high salary; unparalleled business connections; limited working days; spectacular working conditions; periodic taxpayer-funded fact-finding trips; a sizable staff (that could include family and friends); exceptional medical, dental and retirement benefits; weakened insider trading rules; taxpayer funded legal expenses; the ability to moonlight at other jobs; free flights back and forth to the lawmaker’s home state; a family death gratuity; and free parking” [2]. Considering this it is truly no wonder that these guys make every effort to maintain their jobs for as long as humanly possible. Innovative public policy, which includes the addition of term limits, is the only way to address the most pressing of issues currently affecting our nation. How will we address problems such as foreign debt, climate change, immigration, etc. if the congressmen who have been unable to pass successful resolutions continue to remain in power? The solution lies in the succeeding and thus they must be rewarded an equal opportunity.

- Greenberg, Dan. “Term Limits: The Only Way to Clean up Congress.” The Heritage Foundation , Political Process, 1994, https://www.heritage.org/political-process/report/term-limits-the-only-way-clean-congress

- Fulcrum, William NatbonyThe. “Ted Cruz Is Right! Congress Needs Term Limits.” Shelby News , 17 Aug. 2021, https://www.shelbynews.com/opinion/ted-cruz-is-right-congress-needs-term-limits/article_0bfe80b1-b6d9-5894-a39f-7e18376b8274.html

- “OpEd: We Need Congressional Term Limits.” Representative Jake LaTurner , 20 July 2021, https://laturner.house.gov/media/editorial/oped-we-need-congressional-term-limits

- “Suggestions on the Benefits of Term Limits.” U.S. Term Limits , 5 Aug. 2021, https://www.termlimits.com/suggestions/

- Markman, Allison. “Congress Needs Term Limits.” The Iris , 7 Sep. 2021, https://www.theirisnyc.com/post/congress-needs-term-limits

Published in Edition V: Policy in the Media

Be First to Comment

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Term limits for Congress are wildly popular. But most experts say they'd be a bad idea

Ashley Lopez

Congressional term limits are really popular with voters. With experts, not so much. Catie Dull/NPR hide caption

Congressional term limits are really popular with voters. With experts, not so much.

Frustration with America's political system has led to some renewed interest in setting term limits for lawmakers, though it's an idea broadly opposed by experts.

Voters have long been supportive of hard caps on how long someone can be in office, but recent infighting among Republicans over who should be speaker of the U.S. House and health issues among aging members of Congress have reignited calls for federal term limits. ( Ethics scandals at the U.S. Supreme Court have led to separate calls for judicial term limits.)

A Pew Research Center survey this summer found a whopping 87% of Americans say they support congressional term limits.

And it's one of those rare issues that appeals to people from across the political spectrum, with Democratic and Republican respondents in the Pew poll backing the policy in equal measure.

This story is part of a series of reports on alternatives to how Americans vote and elect their political leaders. Click here for more NPR voting stories .

Casey Burgat, the director of the Legislative Affairs program at the Graduate School of Political Management at the George Washington University, says that's not surprising.

"There's a lot of dysfunction in our politics, particularly within Congress," he says. "Congress is one of the most unpopular institutions we have. And so when we have something unpopular, it makes a lot of sense to refresh the people who serve in that institution."

The idea has over the years been proposed by Democratic and Republican candidates alike, including then- President Donald Trump . And the appeal for term limits has only grown recently, says Nick Tomboulides, executive director of an advocacy group called U.S. Term Limits.

"When you're talking about the average American and why 87% of them support term limits, it's the storytelling," he says. "It's these high-profile examples that you see of people who have either lost control, they have cognitive decline ... [and] they're making the most important decisions in our country."

The incumbency advantage

Tomboulides also points to stories of lawmakers staying in office despite scandals and ethics violations.

And he blames all of this on the power of incumbency.

"Ninety-seven percent of incumbents get reelected ," he says. "Last election cycle, 100% of Senate incumbents on the ballot got reelected. Not a single sitting U.S. senator was defeated last cycle. And so from a democracy standpoint, from an election standpoint, our elections are not very democratic."

While the incumbency advantage is perhaps the most popular argument in support of term limits, academics who study this issue say it isn't as cut and dry as many people think it is.

Burgat says there are multiple factors that make it easier for incumbents to win elections, including redistricting. Most members of Congress are in uncompetitive seats drawn to particularly favor their party.

"Over 90% of our elections are uncompetitive, meaning we know essentially what party is going to win those elections, no matter what candidates are running," he says. "And so the faster you turn those politicians over, the more often you're going to have to replace them."

The U.S. has a 'primary problem,' say advocates who call for new election systems

What research has found.

Burgat says term limits don't solve the core problems in American politics that make people dislike Congress — things like gerrymandering, political polarization and the influence of special interests, as well as money in politics.

In fact, academics have broadly found that the effects of term limits are often either mixed or fall short of what proponents claim.

For example, supporters have argued term limits reduce polarization because lawmakers will be forced to be beholden to their constituents over their political parties. However, researchers found that term limits actually increased polarization in some cases.

Burgat says there is also evidence of some unintended consequences in the 16 states that have term limits for their state legislators.

Institutional knowledge

Susan Valdes is a Democratic state lawmaker in Florida, which is one of those 16 states.

"I've seen how the term limits have affected the policies at a state level and how much longer it takes to get good policies done," she says.

As a member of the Florida House, Valdes only gets a maximum of four two-year terms in office. She says she thinks of every term like one school year.

'"I'm going into my next election [thinking it] will be for my senior year," Valdes says. "And these six years in the Florida House have gone by so fast that really and truly the first two sessions, you're really just getting to know the ropes, understand how the lay of the land works, if you will, in that arena."

Florida state Reps. Susan Valdes, left, and Randy Fine high-five after debating a bill during a legislative session on March 8, 2022, in Tallahassee, Fla. Wilfredo Lee/AP hide caption

She says this is the case for pretty much everyone. Valdes says there's not a way for someone to train to become a legislator before getting into office.

Burgat says term limits often force people out of the job when they just start becoming effective and knowledgeable.

"And so when you term-limit someone," he says, "you are effectively cutting out their incentive to invest in learning how to do the job, to delve into policy issues at the depth that they need to and to really dive into how the procedures work, which just takes years. Because, again, there's no training ground for this. There's no training program."

But Tomboulides says he doesn't think lawmakers are spending their time gaining institutional knowledge, even when they have an unlimited amount of time in office. He says there is evidence that members of Congress spend most of their time raising money for their reelection.

"They're not studying the issues," Tomboulides says. "They're not reading these thousand-page bills because they're so focused on getting reelected. They're so focused on keeping the job rather than actually doing the job."

He says if politicians knew they had a limited time in office they would spend more time working for their constituents, instead of focusing on their next election.

But Valdes says she doesn't think term limits have created better legislators in her state.

"What I find is that we wind up trying to create legislation like we check our spaghetti," she says. "Let's see if it sticks to the wall and dinner's ready."

And she says what usually happens is that lawmakers have to go back during the next session and fix the unintended issues created by new policies.

"But in the meantime, what has happened is that people have been affected by those unintended consequences," Valdes says. "And that's where for me, the fairness, the equity, the righteousness of our policies and the intent of the laws that we pass sometimes get misguided."

Republican states swore off a voting tool. Now they're scrambling to recreate it

Voting online is very risky. But hundreds of thousands of people are already doing it

Power of special interests.

Some academics have found evidence that term limits give special interests more influence , because lobbyists and legislative staff have the bulk of the institutional knowledge in state legislatures.

Burgat says he also thinks term limits don't force lawmakers to be more beholden to their voters.

"In reality, studies have shown that term-limited lawmakers behave differently, that when you sever that electoral connection, when they're no longer dependent on voters to remain in office, then they start looking out for No. 1," he says. "They start looking out for themselves in a lot of different ways."

And that includes cozying up to lobbyists to line up their next job. Burgat says a lot of lawmakers don't want to forfeit all the relationships, institutional knowledge and policy expertise they gained in office.

But Tomboulides says he is not convinced that term limits equate to a big win for lobbyists and special interests. He says that's because, in his experience, lobbyists are some of the biggest opponents to his group's efforts.

"I've never had a lobbyist knock on my door and say, 'Hey, I really want to help you guys get term limits,' " he says. "It never happens. But I always have lobbyists opposing me."

Tomboulides says the fact that there is still debate about whether Congress should have term limits just shows the outsized influence that politicians have.

"Because we don't debate other 87% issues," he says. "We don't debate whether, like, my town should have a park or whether we should have, like, regular trash pickup — other 87, 90% issues. We just say this is what the American people want, this is what we're going to do. But term limits are imposed so strongly by the permanent political class in Washington."

And in the end, it is largely up to members of Congress to impose these limits on themselves.

A 1995 U.S. Supreme Court ruling went further to say that even if members of Congress managed to impose term limits on themselves, it could be ruled unconstitutional . That means congressional term limits might have to pass through a constitutional amendment, which is an exceedingly more difficult hurdle to clear.

- voting stories

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Why the Supreme Court Needs (Short) Term Limits

By Rosalind Dixon

Dr. Dixon is a law professor and testified before the Supreme Court Commission in July 2021.

The Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court recently issued its final report , considering a range of procedural changes to how the court operates — most notably, the introduction of term limits for the justices. It pointed to 18-year terms as the leading model for such change. Ideally, it suggested, the states would ratify a constitutional amendment, but some of the commissioners believed this could also be attempted through an act of Congress.

In writings after the report, other members of the commission suggested that term limits do not go far enough to curb an institution they view as hyperpartisan and as having lost public trust. (The court’s approval rating has plummeted , according to Gallup, to its lowest point since 2000, when the poll began.) They said that what was needed was an increase in the size of the court — to rebalance it in a more bipartisan direction.

More is needed to address the court’s current composition and approach — not by expanding the size of the court but through even more powerful, that is, shorter, term limits.

Eighteen years is too long to address the crisis in Supreme Court functioning and legitimacy. We need term limits that start to bite much sooner — after 12 years.

Judicial term limits are a tool widely employed by constitutional designers around the world. Some countries follow the British model of judicial age limits. Others follow the German model of fixed judicial terms, but almost all — other than the United States — reject the idea of lifetime judicial tenure. And they do so by imposing term limits shorter than 18 years.

Perhaps most important, countries with strict judicial term limits include some of the most powerful and respected constitutional courts. In Germany, justices of the Federal Constitutional Court are appointed for a single, nonrenewable 12-year term. It is the same in South Africa. And in Colombia and Taiwan, constitutional justices are appointed for an eight-year term.

Like term limits for the presidency, judicial term limits have several salutary benefits. They encourage regular turnover on a court and the renewal of democratic consent and input into the process of judicial review.

They also discourage the appointment of young, hyperideological judges who are seen as having the capacity to stay on the court for the long run and shift it in a particular predetermined ideological direction.

The Supreme Court does a lot more than call balls and strikes. It decides a range of complex legal and political questions, where legal and political philosophy inevitably play a role.

But for a court to earn and retain the public’s trust, those decisions must reflect a judge’s considered individual moral and political judgments, not any fixed ideological position or platform. Justices must also engage in true collective deliberation, not factional conferencing based on ideological positions.

The Supreme Court still does this in a wide range of nonconstitutional cases and cases that involve complex federal statutes like the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. But it rarely engages in that kind of thoughtful, collective deliberation in cases that involve constitutional rights and freedoms. What is good enough for employment benefits should be good enough for constitutional rights.

Expanding the court (“court packing”) might be justified if things were to get worse. For now, it risks setting off a dynamic with dangers for democracy. It could result in a cycle of escalation: As soon as Republicans regain control of Washington, they would seek to expand the size of the court as well. This would create a court that is too large, is forced to sit in panels rather than en banc, or as a whole, and produces uneven and unpredictable results. This is basically the experience of the Supreme Court of India, which has about 30 justices.

And it would mean that would-be authoritarians around the world would feel licensed to do the same. They would be encouraged to engage in what David Landau of Florida State University College of Law and I have called a form of “abusive” borrowing — the adoption of court packing as a strategy to advance anti-democratic rather than democratic aims.

No reform is without risks. Judges with fixed terms might also start considering postjudicial opportunities in their judgments. This is especially true for lower court judges, which explains why current reform efforts are focused solely on the Supreme Court. But this seems like a minor risk for the Supreme Court itself: Most justices are likely to prefer international arbitration or law teaching to ambassadorships. And as the commission itself noted, at least if there was a constitutional amendment, there could be a bar on judges’ holding certain offices during a period after retirement.

Some might worry that the court could turn out to be too responsive to politics under a 12-year term. This was the main reason the commission itself preferred 18-year judicial terms. But the composition of such a court would remain constant only for a single presidential term. And the details would matter: All judges could be appointed during the final two years of a president’s term, when there is less likely to be unified government and when a president’s choices would affect only the next president. This could also be accompanied by changes to how the Senate vets and votes on nominees.

The biggest risk is that the reform will simply fail to get off the ground. Judicial term limits can be adopted by statute or constitutional amendment. If adopted by statute, it would come before the Supreme Court for review — and the court might well reject the argument that it is compatible with Article III, which entrenches guarantees of judicial independence.

That makes constitutional amendment the safest path for any reform effort — but it is also the most difficult path. Article V provides that any successful amendment requires a supermajority in Congress and among the states. And if an amendment were a serious possibility, one might put a range of reforms — broader changes to how justices are appointed, electoral districts are drawn and campaign finance is regulated — ahead of term-limit reform in the list of structural changes likely to improve American law and politics.

Reforming an institution like the Supreme Court is tricky: Too rapid and radical an approach risks undermining all the institutional respect and capital it has built over centuries. Too moderate a response risks leaving it to face a slow decline in institutional integrity and public respect.

But especially if they could be adopted by statute, 12-year staggered judicial term limits might just help thread that needle — and contribute to meaningful yet restrained change to an institution that is in urgent need of it.

Rosalind Dixon is a law professor and director of the Gilbert + Tobin Center of Public Law at U.N.S.W. Sydney. She is the author, with David Landau, of “ Abusive Constitutional Borrowing : Legal Globalization and the Subversion of Liberal Democracy.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the purpose of the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court report. It was to consider reforms to the Supreme Court, not call for reforms to it.

How we handle corrections

Five reasons to oppose congressional term limits

Subscribe to governance weekly, casey burgat cb casey burgat assistant professor and program director of the legislative affairs program - george washington university’s graduate school of political management @caseyburgat.

January 18, 2018

“Nothing renders government more unstable than a frequent change of the persons that administer it.” – Roger Sherman, open letter, 1788.

Congressional term limits have long been argued to be an easy mechanism for improving the effectiveness of Congress and government at large. More specifically, advocates suggest term limits would allow members to spend less time dialing for dollars and more time on policymaking, allow them to make unpopular but necessary decisions without fear of retaliation at the ballot box, and avoid the corruptive influence of special interests that many assume is an inevitable result of spending too much time in Washington, D.C.

Plus, proponents reason, new blood in Congress is a good thing. New members bring fresh ideas and aren’t beholden to the old ways of Washington that have left so many voters frustrated and Congress’ approval rating in shambles. At the very least, term limits would prevent members from being reelected despite serving long past their primes.

In a political environment where bipartisan agreement on any issue of any size is rarely enjoyed, this proposal is incredibly popular. Seventy-four percent of likely voters are in favor of congressional term limits. In fact, many members—the very people who would be affected should such a policy be put in place—have shown their desire to limit the number of terms they themselves are eligible to serve by introducing legislation in nearly every congressional session since 1943 that would add a term-limit amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Even then-candidate Donald Trump argued term limits would effectively help him “drain the swamp” when elected, much to the delight of his anti-establishment base.

The implicit argument is that Washington, with its corrosive practices, corrupts even the most well-intentioned lawmakers. Because of this, the best—and maybe only—form of inoculation is to limit, constitutionally, the time elected officials can spend in power. At their core, limit advocates contend that elections can’t be trusted to produce incorruptible representatives.

Much of the term-limit reasoning makes sense. However, it ignores the very real downsides that would result. Despite widespread support, instituting term limits would have numerous negative consequences for Congress.

Limiting the number of terms members can serve would:

1. Take power away from voters: Perhaps the most obvious consequence of establishing congressional term limits is that it would severely curtail the choices of voters. A fundamental principle in our system of government is that voters get to choose their representatives. Voter choices are restricted when a candidate is barred from being on the ballot.

2. Severely decrease congressional capacity: Policymaking is a profession in and of itself. Our system tasks lawmakers with creating solutions to pressing societal problems, often with no simple answers and huge likelihoods for unintended consequences. Crafting legislative proposals is a learned skill; as in other professions, experience matters. In fact, as expert analysis has shown with the recently passed Senate tax bill, policy crafted by even the most experienced of lawmakers is likely to have ambiguous provisions and loopholes that undermine the intended effects of the legislation. The public is not best served if inexperienced members are making policy choices with widespread, lasting effects.

Being on the job allows members an opportunity to learn and navigate the labyrinth of rules, precedents and procedures unique to each chamber. Term limits would result in large swaths of lawmakers forfeiting their hard-earned experience while simultaneously requiring that freshman members make up for the training and legislative acumen that was just forced out of the door.

Plus, even with term limits, freshman members would still likely defer to more experienced lawmakers—even those with just one or two terms of service—who are further along the congressional learning curve or who have amassed some level of institutional clout. Much as we see today, this deference would effectively consolidate power in members that have experience in the art of making laws. In other words, a new, though less-experienced, Washington “establishment” would still wield a disproportionate degree of power over policymaking.

Even in instances where staffers, rather than members, lead the charge in crafting policies, it is often the member-to-member interactions that solidify a measure’s final details, build coaltions, and ultimately get legislation passed. Take, for example, the recent Sen. Graham-Sen. Durbin alliance that has recently proposed a bipartisan immigration compromise . Such a partnership is due in no small part to the pair’s long history—Graham and Durbin served two years together in the House and the Senate for 21 years and counting. Term limits would severely hamper the opportunity for these necessary relationships to develop. Strangers in a new environment are in a far worse position to readily trust and rely on their colleagues, particularly from across the aisle.

3. Limit incentives for gaining policy expertise: Members who know their time in Congress is limited will face less pressure to develop expertise on specific issues simply because, in most cases, the knowledge accrued won’t be nearly as valuable in a few short years.

We have seen a semblance of this effect after Republicans limited House committee chairs to six years at the helm. The incentives for chairs to dive deep into the policy details of their committee’s jurisdiction are now limited, given that chairs know they will soon be forced to give up the gavel. (In the 115 th Congress alone, an alarming seven House Chairs have announced their retirements from Congress.)

Thus, term limits would impose a tremendous brain drain on the institution. Fewer experienced policymakers in Congress results in increased influence of special interests that are ready and willing to fill the issue-specific information voids. Additionally, a decrease in the number of seasoned lawmakers would result in greater deference to the executive branch and its agencies that administer the laws on a daily basis, given their greater expertise and longer tenure.

4. Automatically kick out effective lawmakers: No matter how knowledgeable or effectual a member may be in the arduous tasks of writing and advancing legislation, term limits would ensure that his or her talents will run up against a strict time horizon. In what other profession do we force the best employees into retirement with no consideration as to their abilities or effectiveness on the job? Doesn’t it make more sense to capitalize on their skills, talents and experience, rather than forcing them to the sidelines where they will do their constituents, the public and the institution far less good? Kicking out popular and competent lawmakers simply because their time runs out ultimately results in a bad return on the investment of time spent learning and mastering the ins and outs of policymaking in Congress.

5. Do little to minimize corruptive behavior or slow the revolving door:

Because term limits have never existed on the federal level, political scientists have studied states’ and foreign governments’ experiences with term limits to project what effects the measure would have on Congress. These studies regularly find that many of the corruptive, ‘swampy,’ influences advocates contend would be curtailed by instituting term limits are, in fact, exacerbated by their implementation.

Take lobbyist influence, for example. Term limit advocates contend lawmakers unconcerned with reelection will rebuff special interest pressures in favor of crafting and voting for legislation solely on its merits. However, the term limit literature commonly finds that more novice legislators will look to fill their own informational and policy gaps by an increased reliance on special interests and lobbyists. Relatedly, lawmakers in states with term limits have been found—including from this 2006 50-state survey —to increase deference to agencies, bureaucrats, and executives within their respective states and countries simply because the longer serving officials have more experience with the matters.

Advocates also suggest that limiting the number of terms lawmakers can serve will ultimately result in fewer members looking to capitalize on their Hill relationships and policymaking experience by becoming lobbyists themselves. Establishing term limits, however, would likely worsen the revolving door problem between Congress and the private sector given that mandating member exits ensures a predictable and consistently high number of former members available to peddle their influence. The revolving door phenomenon is considered a normative problem without term limits and relatively few departing members per cycle. With term limits, the number of influential former members would drastically increase, giving more private sector landing spots to members whose time has run out. More lobbying firms would have members able to advance their special interests with former members making use of their relationships and deep understanding of the ways of the Hill.

On the surface, the case for term limits is strong given their potential to curtail the forces of corruption that so many assume dictate the ways of Washington. But, precisely because the creation of successful public policies by even the most experienced of officials is so difficult and uncertain, we should not mandate that our most effective and seasoned lawmakers be forced out of the institution. Instead, as constituents, we should rely on the most effective mechanism available to remove unresponsive, ineffectual members of Congress: elections.

Related Content

Thomas E. Mann

January 22, 1997

Casey Burgat

February 3, 2022

Curtlyn Kramer

May 24, 2017

Related Books

Thomas E. Mann, Bruce E. Cain

November 14, 2005

Thomas Mann

February 1, 1990

Ron Haskins

August 24, 2007

Campaigns & Elections

Governance Studies

Elaine Kamarck, Jordan Muchnick

May 23, 2024

William A. Galston

May 21, 2024

May 17, 2024

Term limits aren’t the answer

Assistant Professor of Political Science, Boise State University

Disclosure statement

Charlie Hunt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Boise State University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

There’s no denying that the current Congress has been one of the most chaotic in recent memory. The paralysis in 2023 and 2024 over the selection of the speaker of the House helped lead to one of Congress’ most unproductive years in history.

And although House Speaker Mike Johnson, a Louisiana Republican, survived an effort on May 8, 2024, by far-right members of his conference to oust him, the attempt is a signal of the dysfunction in Congress. It’s also a prime example of why so few Americans have a favorable view of the job Congress is doing.

For many Americans, the solution to this dysfunction is clear: Institute limits on the number of terms members of Congress can serve. If voters use term limits to “ throw the bums out ” and replace them with a new crop of elected leaders, the reasoning goes, the result will be a more effective and perhaps less polarized Congress.

According to recent surveys, 80% or more of the American people are in favor of congressional term limits . You’d be hard pressed to find another policy that more Americans from both sides of the aisle agree on.

Yet there’s a problem: Most political scientists agree that term limits are a bad idea. The evidence suggests that term limits create more problems than they solve and could even accelerate the polarization that’s been hobbling Congress for over a decade .

The value of long incumbencies

Advocates of term limits often point to a striking statistic to support the reform: the consistently high reelection rates of congressional incumbents. Current members of Congress enjoy a strong advantage from their status as an elected representative – that is, more name recognition and campaign resources than their challengers. Advocates for term limits say they are necessary to cut long-term incumbents’ service short in favor of new blood.

But term limits, often set at eight years in state legislatures, undervalue the benefits of representatives who have been serving in office for a long time. These members have had more time to gain knowledge and experience about Congress as an institution; develop policy expertise in issues important to their districts; and cultivate working relationships with fellow members that help them make policy more effectively.

Data from the Center for Effective Lawmaking , a research center with the University of Virginia and Vanderbilt University, which tracks members’ success rates for legislation they sponsor, strongly supports this perspective: The longer members serve, the more effective a lawmaker they are likely to become.

Fresh perspectives in Congress are important, which is why the U.S. has elections. But term limits would stifle members’ lawmaking careers just as they’re getting off the ground. Even worse, losing well-seasoned members with issue expertise would leave inexperienced lawmakers vulnerable to influence from lobbyists and special interest groups that would highlight their own expertise and seek to influence legislation in their favor.

This is precisely what has happened in state legislatures that instituted term limits around the turn of the century.

Term limits don’t solve extremism

Term limits are also unlikely to make Congress less ideologically extreme.

Judging from statements they’ve made, many of the more tenured members who are retiring at the end of the current Congress are the ones lamenting extremism and partisanship, often citing these trends as the reason they’re leaving.

Meanwhile, many of the most polarizing and best-known representatives in Congress – think Georgia’s Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican; Matt Gaetz of Florida, also a Republican; and Democrat Ilhan Omar from Minnesota – are newer members with less apparent interest in compromise and achievement of long-term policy goals. The data reflects this : The average long-serving member of Congress nearly always has lower ideological extremism scores than the average congressional newcomer, based on roll call votes on policy issues.

Vast majorities of Americans say they prefer a Congress that compromises to get things done. Term limits would almost certainly fail to achieve this.

Congressional ‘senioritis’

But this isn’t the only negative impact of term-limits reform.

Research by political scientist Gerald Wright suggests not only that term limits for state legislators were ineffective at reducing polarization, but that term-limited lawmakers – those legally prevented from running for reelection – tend to exert “decreased legislative effort” and missed roll call votes compared with their colleagues who are up for reelection.

In other words, members in their legally mandated final term in office enjoy a kind of “senioritis” – the apathy that can hit students in their last term of high school or college – in their legislatures because they don’t have to face the voters again at the ballot box.

Elections: The ultimate term limits

Most political scientists agree that high incumbent reelection rates are mainly the result of highly partisan districts and voters, not corrupt incumbents advantaged by years of service. The voters already have a say in primaries and general elections to vote out incumbents.

But they largely choose not to.

It is likely that very loose term limits – say, 20 years of service –could help prevent aging incumbents such as Mitch McConnell or the late Dianne Feinstein from serving well past their prime. But as a method for depolarizing Congress and making it effective again, the evidence is thin.

- US Congress

- Mythbusting

- US House of Representatives

- Polarization

- Speaker of the House

- term limits

- Election 2024

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Americans’ Dismal Views of the Nation’s Politics

10. how americans view proposals to change the political system, table of contents.

- The impact of partisan polarization

- Persistent concerns over money in politics

- Views of the parties and possible changes to the two-party system

- Other important findings

- Explore chapters of this report

- In their own words: Americans on the political system’s biggest problems

- In their own words: Americans on the political system’s biggest strengths

- Are there clear solutions to the nation’s problems?

- Evaluations of the political system

- Trust in the federal government

- Feelings toward the federal government

- The relationship between the federal and state governments

- Americans’ ratings of their House member, governor and local officials

- Party favorability ratings

- Most characterize their party positively

- Quality of the parties’ ideas

- Influence in congressional decision-making

- Views on limiting the role of money in politics

- Views on what kinds of activities can change the country for the better

- How much can voting affect the future direction of the country?

- Views of members of Congress

- In their own words: Americans’ views of the major problems with today’s elected officials

- How much do elected officials care about people like me?

- What motivates people to run for office?

- Quality of recent political candidates

- In elections, is there usually at least one candidate who shares your views?

- What the public sees as most important in political candidates

- Impressions of the people who will be running for president in 2024

- Views about presidential campaigns

- How much of an impact does who is president have on your life?

- Whose priorities should the president focus on?

- How different are the Republican and Democratic parties?

- Views of how well the parties represent people’s interests

- What if there were more political parties?

- Would more parties make solving problems easier or harder?

- How likely is it that an independent candidate will become president?

- Americans who feel unrepresented by the parties have highly negative views of the political system

- Views of the Electoral College

- Should the size of the U.S. House of Representatives change?

- Senate seats and population size

- Younger adults more supportive of structural changes

- Politics in a single word or phrase: An outpouring of negative sentiments

- Negative emotions prevail when Americans think about politics

- Americans say the tone of political debate in the country has worsened

- Which political topics get too much – and too little – attention?

- Majority of Americans find it stressful to talk politics with people they disagree with

- Acknowledgments

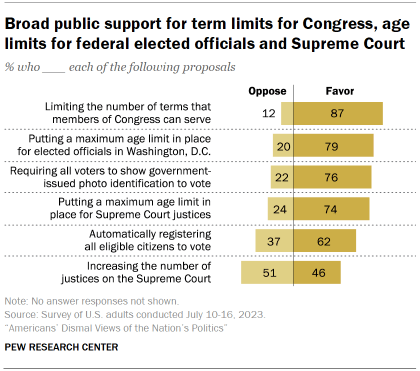

Reflecting the public’s unhappiness with the U.S. political system , there is broad support for a number of significant structural changes to politics:

Term limits for members of Congress . An overwhelming majority of adults (87%) favor limiting the number of terms that members of Congress are allowed to serve. This includes a majority (56%) who strongly favor this proposal; just 12% are opposed.

Maximum age limits for elected officials in Washington, D.C., and Supreme Court justices. Nearly eight-in-ten adults (79%) favor maximum age limits for elected officials in Washington, while 74% favor a maximum age limit for Supreme Court justices.

Requiring voters to show government-issued identification. By more than three-to-one (76% to 22%), Americans support requiring all voters to show government-issued photo identification in order to vote. These views are little changed from 2021 .

A narrower majority (62%) favors automatically registering all eligible citizens to vote.

A proposal to increase the number of justices on the Supreme Court, by contrast, draws slightly more opposition (51%) than support (46%).

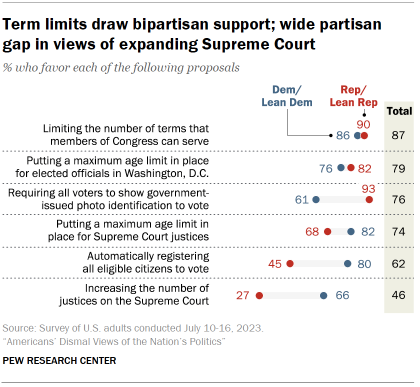

Overwhelming majorities in both parties favor term limits for members of Congress

Term limits for members of Congress are widely popular with both Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (90%) and Democrats and Democratic leaners (86%).

Establishing age limits for elected officials in Washington, D.C., also draws broad bipartisan support.

There are wider partisan differences in views of putting a maximum age limit for Supreme Court justices. Still, 82% of Democrats and 68% of Republicans support age limits for the justices.

As in past surveys, Republicans and Democrats hold different views of proposals to change how voting works in this country.

Nearly all Republicans support requiring all voters to show government-issued identification (93% favor this), compared with a narrower majority (61%) of Democrats. Meanwhile, Democrats (80%) are much more likely than Republicans (45%) to favor automatically registering all eligible citizens to vote.

Increasing the number of justices on the Supreme Court is supported by about two-thirds of Democrats (66% favor). But only about a quarter of Republicans (27%) favor expanding the size of the court, while more than twice as many (72%) are opposed.

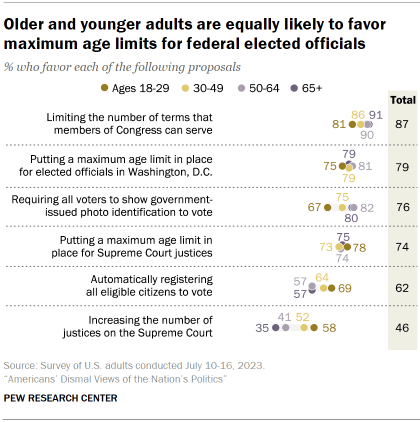

Young adults more likely than older people to support adding Supreme Court justices

There are fairly modest age differences in views of most of these proposals. However, adults under age 50 are more likely than those 50 and older to favor automatically registering all eligible citizens to vote (66% vs. 57%).

And a majority of adults under 30 (58%) favor increasing the number of justices on the Supreme Court. Support for this proposal decreases with age: About a third (35%) of those 65 and older favor this.

These age differences are more pronounced among Republicans than Democrats. About four-in-ten Republicans ages 18 to 29 (44%) favor expanding the court, but that drops steadily with age; just 13% of Republicans 65 and older support this. In contrast, Democrats in all age groups are nearly equally likely to favor increasing the number of justices on the court.

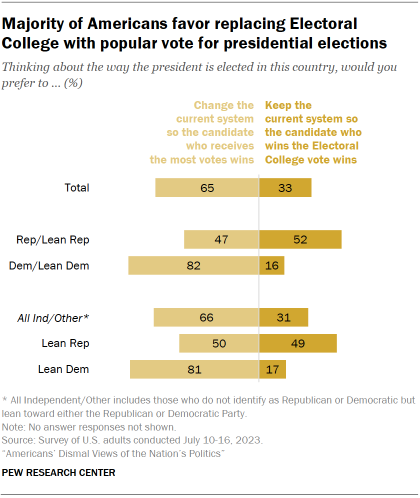

Nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) favor changing the current system for presidential elections so that the candidate who receives the most votes wins, while a third prefer to keep the current system so that the candidate who wins the Electoral College vote wins the election.

Support for changing the current system has ticked up slightly since last summer .

Democrats remain much more likely to favor a popular vote system for presidential elections than Republicans: 82% of Democrats and Democratic leaners say they would prefer to change the current system, compared with 47% of Republicans and Republican leaners.

Among all political independents and others who don’t identify with a party, about two-thirds (66%) favor changing the current system so the candidate who receives the most votes wins, while 31% prefer to keep the current Electoral College system. However, Democratic-leaning independents are much more supportive of changing the Electoral College system than Republican-leaning independents.

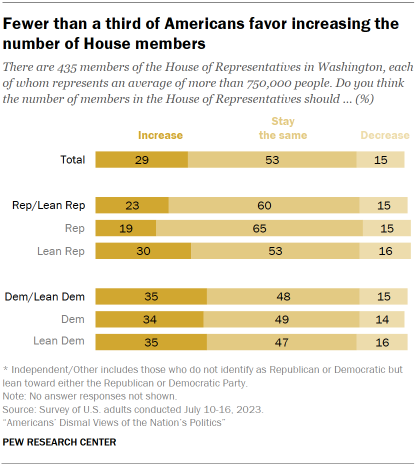

About three-in-ten adults (29%) say the size of the House of Representatives should be increased beyond its current 435 members, while a narrow majority (53%) say the size of the House should stay the same. Another 15% prefer to decrease the size of the House.

Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say that the number of members in the House should increase, though larger shares in both parties favor keeping the House at its current size.

About a third of Democrats and Democratic leaners (35%) favor increasing the size of the House, compared with 23% of Republicans and Republican leaners.

Republican-leaning independents (30%) are more likely than GOP partisans to favor increasing the size of the House (19%). The views of Democratic-leaning independents on this question are nearly identical to those of Democratic identifiers.

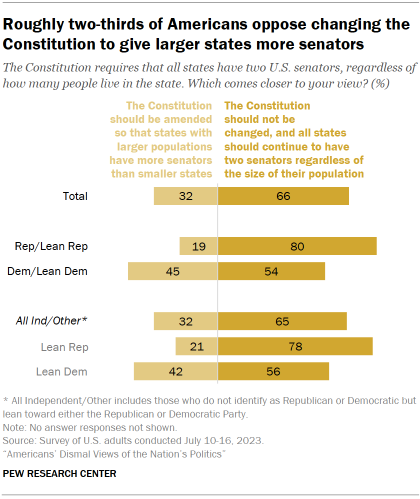

When it comes to the Senate, 66% of adults say that the method of determining representation in the upper chamber should not be changed, and all states should continue to have two senators regardless of population size. Roughly half as many (32%) say that the Constitution should be amended so that states with larger populations have more senators than smaller states.

Eight-in-ten Republicans favor maintaining the Senate’s present structure.

Among Democrats, a narrower majority (54%) favor the current allocation, while 45% say the Constitution should be amended.

The views of independents are similar to the overall public’s views, with 65% preferring to keep the current system as-is. However, Democratic-leaning independents’ views are nearly identical to Democratic partisans’ views, while Republican-leaning independents’ views are nearly identical to Republicans’ views.

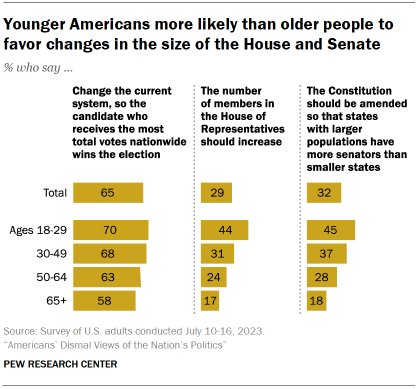

Younger adults are more likely than older adults to favor a popular vote for president, an expansion of the House of Representatives and a change to the way representation in the Senate is apportioned.

While majorities of adults across age groups support changing the presidential election system so the candidate who wins the popular vote wins the election, this view is more common among those under 50 (69%) than among those ages 50 and older (61%).

Age differences are larger when it comes to changes to the structure of Congress, with support for changes decreasing with age. Adults under 30 are much more likely than those 65 and older to say both that the number of House members should be increased (44% vs. 17%) and that the Constitution should be amended so that more populous states have more senators than smaller states (45% vs. 18%).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Election 2024

- Election System & Voting Process

- Federal Government

- National Conditions

- Political Animosity

- Political Discourse

- Political Parties

- Political Polarization

- State & Local Government

- Trust in Government

- Trust, Facts & Democracy

In GOP Contest, Trump Supporters Stand Out for Dislike of Compromise

What americans know about their government, congress has long struggled to pass spending bills on time, how the gop won the turnout battle and a narrow victory in last year’s midterms, narrow majorities in u.s. house have become more common but haven’t always led to gridlock, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Get Email Updates from Ballotpedia

First Name *

Please complete the Captcha above

Ballotpedia on Facebook

Share this page

Follow Ballotpedia

Ballotpedia on Twitter

Term limits in the united states.

- 1 Federal term limits

- 2.1 State legislatures with term limits

- 2.2 Overturned state legislative term limits

- 3 Municipal term limits

- 5 External links

There are a number of term limits to offices in the United States, which restrict the number of terms an individual can hold a certain office.

Federal term limits

The Amendment XXII, United States Constitution says that no person can be elected President of the United States more than twice. Term limits are a particularly important issue in the United States.

President George Washington originally started the tradition of informal Presidential term limits by refusing to run for a third term. The short-lived Confederate States of America adopted a six-year term for their President and Vice-President, and barred the President from seeking re-election. This innovation was endorsed by many American politicians after the war, most notably by Rutherford B. Hayes in his inaugural address. Hayes' proposal did not come to fruition, but the government of Mexico adopted the Confederate term and limit for its federal President. Franklin Roosevelt was the first and only President to successfully break Washington's tradition, and he died in office while serving his fourth term.

Congressional term limits were featured prominently in the Republican Party's Contract with America in the United States House 1994 election campaign and may well have contributed to the Republicans gaining control of the United States House of Representatives from the Democratic Party for the first time since the United States 1952 elections. The Republican leadership brought to the floor of the House a constitutional amendment that would limit House members to six two-year terms and members of the Senate to two six-year terms. However, this amendment did not gain the approval of U.S. Term Limits , the largest private organization pushing for Congressional term limits. (U.S. Term Limits wanted House members to be limited to three two-year terms.) With the Republicans holding 230 seats in the House, the amendment did receive a simple majority in the House. However, a two-thirds majority (290 votes) is required to pass a constitutional amendment, and thus the bill failed. The concept subsequently lost momentum by the mid 1990s.

In May 1995, the United States Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton , that states cannot impose term limits upon their U.S. Representatives or U.S. Senators.

Term limits at the federal level are restricted to the executive branch and some agencies. The U.S. Congress, however, remains without electoral limits.

State term limits

Term limits for state governors or others within the state executive branch and other high constitutional offices have existed since the beginning of the United States. One of the first such limits of its kind, the Delaware Constitution of 1776, limited the Governor of Delaware to a single three-year term; the governor of Delaware can serve two 4-year terms. As of present, there are 36 states have adopted term limits of various types for their governors. One variation allowed a governor to be re-elected, but only to non-consecutive terms. (To circumvent this provision, George Wallace, the governor of Alabama , announced in 1966 that voters should elect his wife, Lurleen Wallace, their next governor. It was clear during the campaign that Mrs. Wallace would be a governor in name only, and thus she was elected the first female governor of Alabama.)

Beginning in the 1990s, term limit laws were imposed on twenty state legislatures through either successful ballot measures , referenda, legislative acts, or state constitutional changes. The Maine legislature was the first state to enact legislative term limits in 1993.

Since 1997, however, six state legislatures have either overturned their own limits or state supreme courts have ruled such limits unconstitutional. In 2002 the Idaho Legislature became the first legislature of its kind to repeal its own term limits, enacted by a public vote in 1994, ostensibly because it applied to local officials along with the legislature.

State legislatures with term limits

Overturned state legislative term limits.

The following six legislatures have had their term limits nullified:

- Idaho Legislature: the Legislature repealed its own term limits in 2002.

- Massachusetts General Court : the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court overturned term limits in 1997.

- Oregon Legislative Assembly: the Oregon Supreme Court ruled term limits unconstitutional in 2002.

- Utah State Legislature: the Legislature repealed its own term limits in 2003.

- Washington State Legislature: the Washington Supreme Court voided term limits in 1998.

- Wyoming Legislature: the Wyoming Supreme Court ruled term limits unconstitutional in 2004.

Municipal term limits

As of 2023, nine of the ten largest cities in the United States impose term limits on elected municipal officials, according to U.S. Term Limits , which, according to its website, "advocates for term limits at all levels of government." [1] [2]

- Term limits

- List of term limits ballot measures

- U.S. Term Limits

- Eric O'Keefe

External links

- National Conference of State Legislatures term limits overview

- U.S. Term limits page on state legislative term limits

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 U.S. Term Limits , "Nine Of The Ten Largest U.S. Cities Have Term Limits," accessed March 13, 2023

- ↑ U.S. Term Limits , "About U.S. Term Limits," accessed March 13, 2023

- One-off pages, active

- Public policy concepts and issues

Ballotpedia features 490,279 encyclopedic articles written and curated by our professional staff of editors, writers, and researchers. Click here to contact our editorial staff or report an error . For media inquiries, contact us here . Please donate here to support our continued expansion.

Information about voting

- What's on my ballot?

- Where do I vote?

- How do I register to vote?

- How do I request a ballot?

- When do I vote?

- When are polls open?

- Who represents me?

2024 Elections

- Presidential election

- Presidential candidates

- Congressional elections

- Ballot measures

- State executive elections

- State legislative elections

- State judge elections

- Local elections

- School board elections

2025 Elections

- State executives

- State legislatures

- State judges

- Municipal officials

- School boards

- Election legislation tracking

- State trifectas

- State triplexes

- Redistricting

- Pivot counties

- State supreme court partisanship

- Polling indexes

Public Policy

- Administrative state

- Criminal justice policy

- Education policy

- Environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG)

- Unemployment insurance

- Work requirements

- Policy in the states

Information for candidates

- Ballotpedia's Candidate Survey

- How do I run for office?

- How do I update a page?

- Election results

- Send us candidate contact info

Get Engaged

- Donate to Ballotpedia

- Report an error

- Newsletters

- Ballotpedia podcast

- Ballotpedia Boutique

- Media inquiries

- Premium research services

- 2024 Elections calendar

- 2024 Presidential election

- Biden Administration

- Recall elections

- Ballotpedia News

SITE NAVIGATION

- Ballotpedia's Sample Ballot

- 2024 Congressional elections

- 2024 State executive elections

- 2024 State legislative elections

- 2024 State judge elections

- 2024 Local elections

- 2024 Ballot measures

- Upcoming elections

- 2025 Statewide primary dates

- 2025 State executive elections

- 2025 State legislative elections

- 2025 Local elections

- 2025 Ballot measures

- Cabinet officials

- Executive orders and actions

- Key legislation

- Judicial nominations

- White House senior staff

- U.S. President

- U.S. Congress

- U.S. Supreme Court

- Federal courts

- State government

- Municipal government

- Election policy

- Running for office

- Ballotpedia's weekly podcast

- About Ballotpedia

- Editorial independence

- Job opportunities

- News and events

- Privacy policy

- Disclaimers

Why No Term Limits for Congress? The Constitution

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Legal System

- U.S. Political System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.S., Texas A&M University

Since the early 1990s, the long-running demand to impose term limits on the Senators and Representatives elected to the U.S. Congress has intensified. Considering that since 1951 the President of the United States has been limited to two terms, term limits for members of Congress seem reasonable. There's just one thing in the way: the U.S. Constitution .

Historical Precedence for Term Limits

Even before the Revolutionary War, several American colonies applied term limits. For example, under Connecticut’s “Fundamental Orders of 1639,” the colony’s governor was prohibited from serving consecutive terms of only one year, and stating that “no person be chosen Governor above once in two years.” After independence, Pennsylvania’s Constitution of 1776 limited members of the state’s General Assembly from serving more than “four years in seven.

At the federal level, the Articles of Confederation , adopted in 1781, set term limits for delegates to the Continental Congress – the equivalent of the modern Congress – mandating that “no person shall be capable of being a delegate for more than three years in any term of six years.”

There Have Been Congressional Term Limits

Senators and Representatives from 23 states faced term limits from 1990 to 1995, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared the practice unconstitutional with its decision in the case of U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton .

In a 5-4 majority opinion written by Justice John Paul Stevens, the Supreme Court ruled that the states could not impose congressional term limits because the Constitution simply did not grant them the power to do so.

In his majority opinion, Justice Stevens noted that allowing the states to impose term limits would result in "a patchwork of state qualifications" for members of the U.S. Congress, a situation he suggested would be inconsistent with "the uniformity and national character that the framers sought to ensure." In a concurring opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that state-specific term limits would jeopardize the "relationship between the people of the Nation and their National Government."

Term Limits and the Constitution

The Founding Fathers considered—and rejected—the idea of term limits for Congress. A majority of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 felt that the longer they served, the more experienced, knowledgeable, and thus, effective members of Congress would become. As Father of the Constitution James Madison explained in Federalist Papers No. 53:

"[A] few of the members of Congress will possess superior talents; will by frequent re-elections, become members of long standing; will be thoroughly masters of the public business, and perhaps not unwilling to avail themselves of those advantages. The greater the proportion of new members of Congress, and the less the information of the bulk of the members, the more apt they be to fall into the snares that may be laid before them," wrote Madison.

Delegates who sided with Madison in opposing term limits argued that regular elections by the people could be a better check on corruption than constitutional term limits and that such restrictions would create their problems. Ultimately, the anti-term limits forces won out and the Constitution was ratified without them.

So now the only remaining way to impose term limits on Congress is to undertake the long and uncertain task of amending the Constitution .

This can be done in one of two ways. First, Congress can propose a term limits amendment with a two-thirds “ supermajority ” vote. In January 2021, Senators Ted Cruz of Texas, along with Marco Rubio of Florida and other Republican colleagues, introduced a bill ( S.J.Res.3 ) calling for a constitutional amendment that would limit senators to two six-year terms and House members to three two-year terms.

In introducing the bill, Senator Cruz argued, “Though our Founding Fathers declined to include term limits in the Constitution, they feared the creation of a permanent political class that existed parallel to, rather than enmeshed within, American society.

Should Congress pass the bill, which as history has proven, is highly doubtful, the amendment would be sent to the states for ratification.

If Congress refuses to pass a term limits amendment, the states could do it. Under Article V of the Constitution, if two-thirds (currently 34) of the state legislatures vote to demand it, Congress is required to convene a full constitutional convention to consider one or more amendments.

The Aging Senators Argument

Another common argument in favor of congressional term limits is the advancing age of lawmakers who, for various reasons, continually win reelection.

According to the Congressional Research Service, 23 members of the Senate are in their 70s at the beginning of 2022, while the average age of senators was 64.3 years—the oldest in history. Thus the debate goes on: Experience vs. new ideas? Career politicians vs. short-timers? Old vs. young? Baby Boomers vs. Gen X, Y (millennials), or Z?

Senators—more so than representatives—often remain in office for decades because their constituents are reluctant to give up the advantages of incumbency: Seniority, committee chairmanships, and all the money poured into their states. For example, West Virginia’s Senator Robert Byrd , who was in his ninth term when he died at age 92, funneled an estimated $10 billion to his state during his 51 years in the Senate, according to the Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History.

In 2003, South Carolina’s Senator Strom Thurmond retired at age 100 after serving 48 years in the Senate. The not-very-well-hidden secret was that during his last term, which ended six months before his death, his staff did virtually everything for him but push the vote button.

While the Founding Fathers created minimum age requirements for serving in the House, Senate, or as president, they did not address a maximum age. So the question remains: How long should members of Congress be allowed to work? In 1986, Congress passed a law ending mandatory retirement by age 65 for most professions except the military, law enforcement, commercial pilots, air traffic controllers, and, in a few states, judges.

Notably, however, six of the most brilliant political figures in the first 50 years of the United States; James Madison, Daniel Webster , Henry Clay , John Quincy Adams , John C. Calhoun , and Stephen A. Douglas served a combined 140 years in Congress. Many of America's greatest legislative achievements—such as Social Security, Medicare, and Civil Rights—came from members of Congress who were in their later years of seniority.

Why Presidential Term Limits?

At the Constitutional Convention, some delegates had fears of creating a president was too much like a king. However, they came close to doing by adopting provisions like the presidential pardon , a power similar to the British King’s “royal prerogative of mercy.” Some delegates even favored making the presidency a lifetime appointment. Though he was quickly shouted down, John Adams proposed that the president should be addressed as “His Elective Majesty.”

Instead, the delegated agreed on the complicated and often controversial electoral college system , which would still ensure, as the framers desired, that presidential elections were not left solely in the hands of ordinarily uninformed voters. Within this system, they shortened a president’s appointment from life to four years. But because most of the delegates opposed setting a limit on how many four-year terms a president could serve, they did not address it in the Constitution.

Knowing he could have probably been reelected for life, President George Washington originally started the tradition of informal Presidential term limits by refusing to run for a third term. Created after the secession of southern states from the Union in 1861, the short-lived Confederate States of America adopted a six-year term for their president and vice president and barred the president from seeking re-election. After the Civil War , many American politicians embraced the idea of presidential term limits.

Official term limits on the chief executive were introduced after the four consecutive elections of President Franklin Roosevelt .

While earlier presidents had served no more than the two-term precedent set by George Washington, Roosevelt remained in office for nearly 13 years, prompting fears of a monarchial presidency. So, in 1951, the United States ratified the 22nd Amendment , which strictly limits the president to serving no more than two terms.

The amendment had been one of 273 recommendations to Congress by the Hoover Commission, created by Pres. Harry S. Truman , to reorganize and reform the federal government. It was formally proposed by the U.S. Congress on March 24, 1947, and was ratified on Feb. 27, 1951.

An Organized Movement for Term Limits

The ultimate goal of the USTL is to get the 34 states required by Article V of the Constitution to demand a convention to consider amending the Constitution to require term limits for Congress. Recently, USTL reported that 17 of the needed 34 states had passed resolutions calling for an Article V constitutional convention. If adopted by a constitutional convention, the term limits amendment would have to be ratified by 38 states.

The Pros and Cons of Congressional Term Limits

Even political scientists remain divided on the question of term limits for Congress. Some argue that the legislative process would benefit from “fresh blood” and ideas, while others view the wisdom gained from long experience as essential to the continuity of government.

The Pros of Term Limits

- Limits Corruption: The power and influence gained by being a member of Congress for a long period of time tempt lawmakers to base their votes and policies on their own self-interest, instead of those of the people. Term limits would help prevent corruption and reduce the influence of special interests.

- Congress – It’s Not a Job: Being a member of Congress should not become the office-holders career. People who choose to serve in Congress should do so for noble reasons and a true desire to serve the people, not just to have a perpetual well-paying job.

- Bring in Some Fresh Ideas: Any organization – even Congress – thrives when fresh new ideas are offered and encouraged. The same people holding the same seat for years leads to stagnation. Basically, if you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always get what you’ve always got. New people are more likely to think outside the box.

- Reduce Fundraising Pressure: Both lawmakers and voters dislike the role money plays in the democratic system. Constantly facing reelection, members of Congress feel pressured to devote more time to raising campaign funds than to serving the people. While imposing term limits might not have much of an effect on the overall amount of money in politics, it would at least limit the amount of time elected officials will have to donate to fundraising.

The Cons of Term Limits

- It’s Undemocratic: Term limits would actually limit the right of the people to choose their elected representatives. As evidenced by the number of incumbent lawmakers reelected in every midterm election , many Americans truly like their representative and want them to serve for as long as possible. The mere fact that a person has already served should not deny the voters a chance to return them to office.

- Experience is Valuable: The longer you do a job, the better you get at it. Lawmakers who have earned the trust of the people and proven themselves to be honest and effective leaders should not have their service cut short by term limits. New members of Congress face a steep learning curve. Term limits would reduce the chances of new members growing into the job and becoming better at it.

- Throwing Out the Baby With the Bathwater: Yes, term limits would help eliminate some of the corrupt, power-hungry and incompetent lawmakers, but it would also get rid of all the honest and effective ones.

- Getting to Know Each Other: One of the keys to being a successful legislator is working well with fellow members. Trusts and friendships among members across party lines are essential to progress on controversial legislation. Such politically bipartisan friendships take time to develop. Term limits would reduce the chances for legislators to get to know each other and use those relationships to the advantage of both parties and, of course, the people.

- Won’t Really Limit Corruption: From studying the experiences of state legislatures, political scientists suggest that instead of “draining the swamp,” congressional term limits could actually make corruption in the U.S. Congress worse. Term limit advocates contend that lawmakers who do not have to worry about being reelected will not be tempted to “cave in” to pressure from special interest groups and their lobbyists, and will instead base their votes solely on the merits of the bills before them. However, history has shown that inexperienced, term-limited state legislators are more likely to turn to special interests and lobbyists for information and “direction” or legislation and policy issues. In addition, with term limits, the number of influential former members of Congress would increase dramatically. Many of those former members would—as they do now—go to work for private sector lobbying firms where their deep knowledge of the political process helping to advance special interest causes.

Established in the early 1990s, the Washington, D.C. based U.S. Term Limits (USTL) organization has advocated for term limits at all levels of government. In 2016, USTL launched its Term Limits Convention, a project to amend the Constitution to require congressional term limits. Under the Term Limits Convention program, the state legislatures are encouraged to enact term limits for the members of Congress elected to represent their states.

- The Debate Over Term Limits for Congress

- Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution

- How to Amend the Constitution

- Qualifications to be a US Representative