What is Modern Art — Definition, History and Examples

- Art Styles Explained

- Art History Timeline

- Renaissance

- Neoclassicism

- Naturalism vs Realism

- Romanticism

- Art Nouveau

- Kinetic Art

- Post Impressionism

- Primitivism

- Abstract Expressionism

- Avant Garde

- Conceptual Art

- Constructivism Art

- Expressionism

- Harlem Renaissance

- Magical Realism

- Suprematism

- Contemporary Art

- Installation Art

- Photorealism

- Performance Art

D o you ever look at a painting in a modern art museum and wonder “what am I looking at?” We’ve all experienced that moment when we want to know more about the unusual artwork we’re seeing. Modern artwork is mysterious and thought-provoking, making it an exciting form of expression for artists around the world. But what is modern art exactly, where did it come from, and why do so many people love it? In this blog post, we’ll explore these questions to help you understand the nature of modern art better.

TYPES OF ART STYLES

Art styles explained & art history timeline.

- Avant-Garde

- Post-Impressionism

What is Modern Art Movement?

First, let’s define modern art.

The concept of modern art can seem elusive at first. Before we dive into its history and important artists, let’s look at the modern art definition.

MODERN ART DEFINITION

What is modern art.

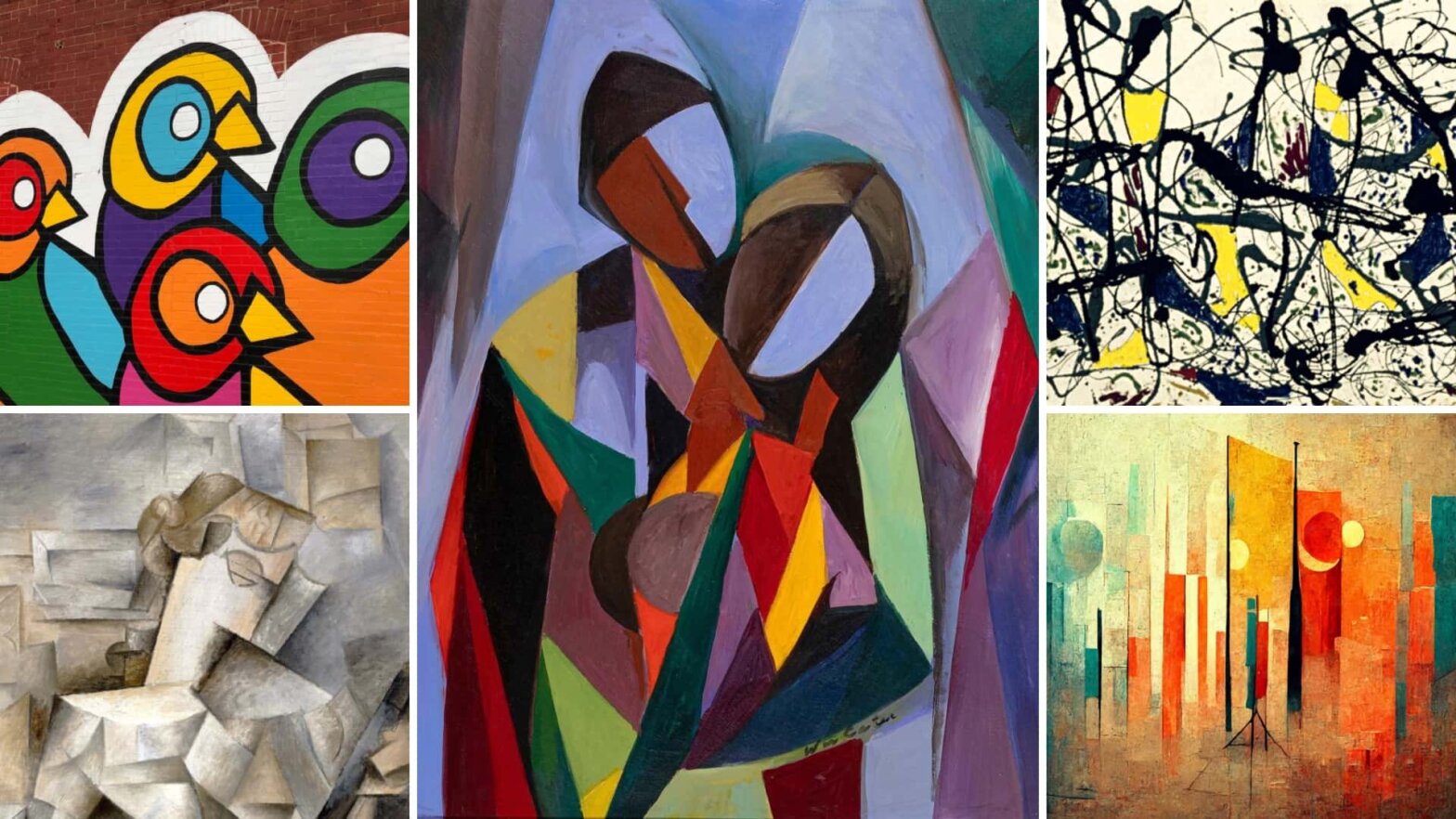

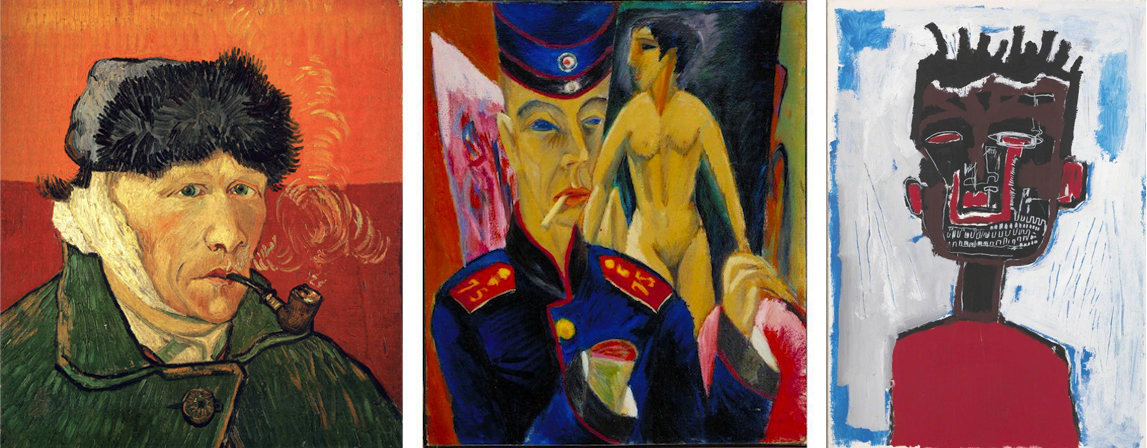

Modern art is an art movement that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was characterized by a shift away from traditional styles to a more abstract, experimental approach to creating works of art. Major modern art movements include Impressionism, Expressionism, Cubism, Fauvism, Dadaism and Surrealism. Influential modernist artists include Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky, Salvador Dalí and Marcel Duchamp. Modern artwork has had a lasting impact on the development of visual culture and continues to influence contemporary art today.

Characteristics of Modern Art:

- Use of vibrant colors and bold brushstrokes

- Abstract, expressive forms and shapes

- Exploration of new concepts such as movement, time, and space

- Rejection of mainstream values and traditional techniques

This article is part of our ongoing series on Art Styles . You can also refer to our Art History Timeline post to help place this movement in context.

What is Modern Art Influenced By?

History of modern art.

Now that we’ve covered the modern art definition it’s important to clarify that the history of modern artwork is a complex and ever-evolving narrative. It began in the late 19th century as a revolt against academic artistic conventions, which championed realism and classicism.

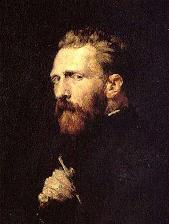

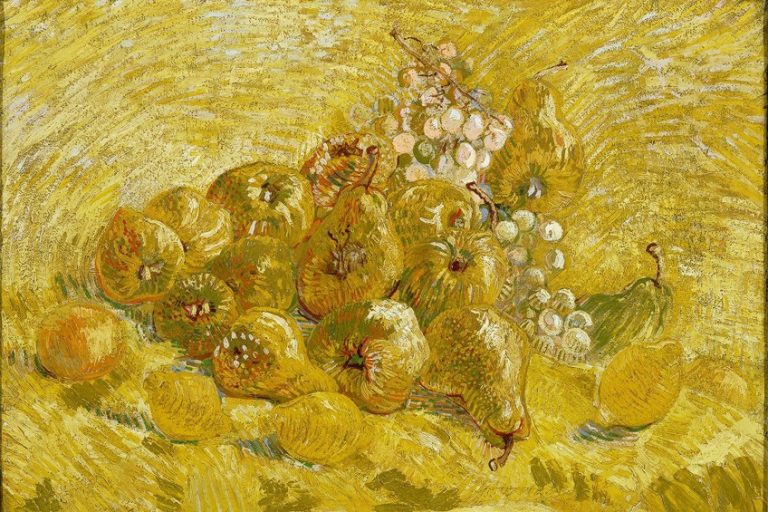

Led by pioneering artists such as Claude Monet, Paul Cezanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. This movement sought to eliminate traditional rules around painting in favor of more experimental approaches to art-making.

What is modern art and where did it begin? For some great insight on how art evolved into modern art and how and why artists began pushing the limits of the form, check out this video by Nerdwriter1.

How Art Arrived At Jackson Pollock

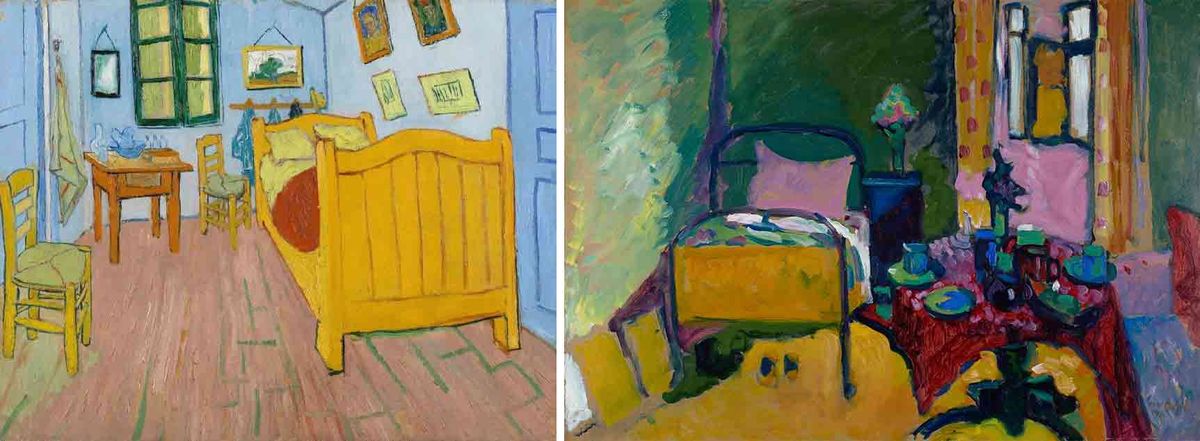

To reiterate the video above, artists like Monet and Van Gogh influenced the push toward abstraction and away from realism. These works led to an influx of abstract styles such as Cubism, Fauvism, and Surrealism which had lasting effects on visual culture.

For example, Cubism was one of the first modern art movements, emerging in the early 20th century. It was a radical departure from traditional painting techniques, with its emphasis on abstract compositions and geometric forms.

Les Femmes d'Alger (Version "O"), 1955 by Pablo Picasso

Artists such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque painted with this technique, seeking to blur distinctions between objects and represent them in a new way, challenging conventional understanding of visual representation. This desire was at the core of modern art.

Today modern art continues to influence contemporary art across all mediums from painting, sculpture and installation through to digital media and performance art.

While each movement has its own distinguishing characteristics and qualities, there is a thread that flows through each modern art movement. Its practitioners sought to push the boundaries of traditional art-making techniques and explore new ways of expressing feelings and ideas through visual media. Let’s take a deeper dive into some of the most important modern art movements in art history and some examples of modern art from each.

Types of Modern Art

Impressionism.

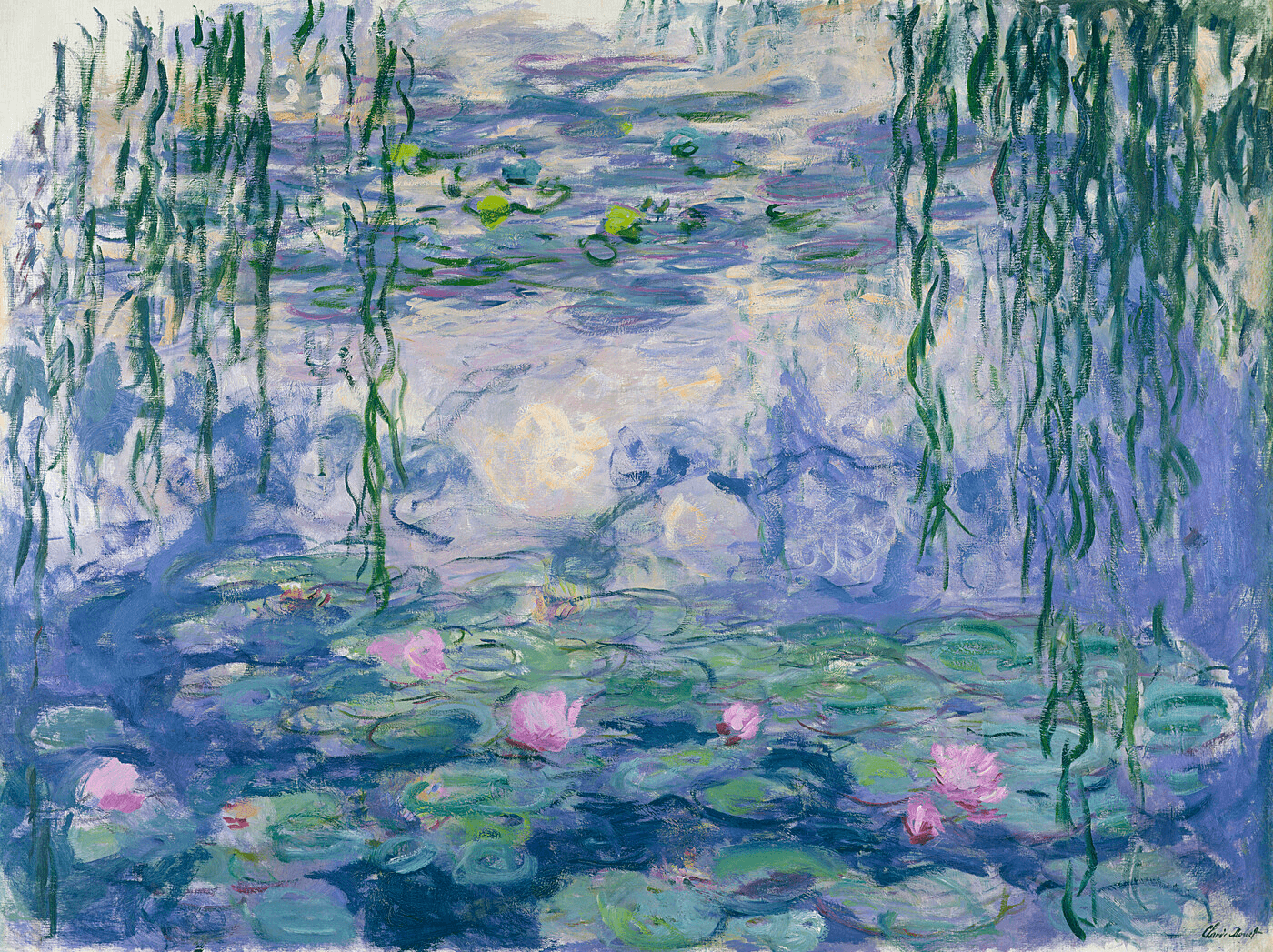

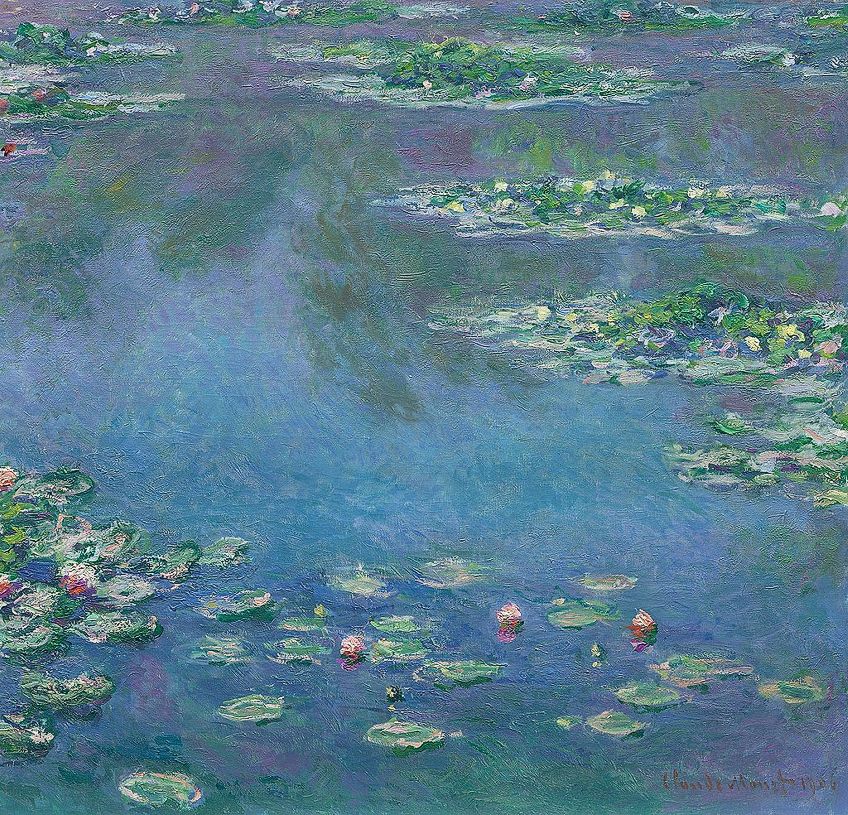

Impressionism was an art movement that began in France in the late 19th century. It is characterized by its focus on capturing the effects of light and atmosphere, and emphasizes accurate depictions of specific times of day and season. Artists employed brilliant colours, thick brush strokes, high chroma, and vivid light-dark contrasts to create their works.

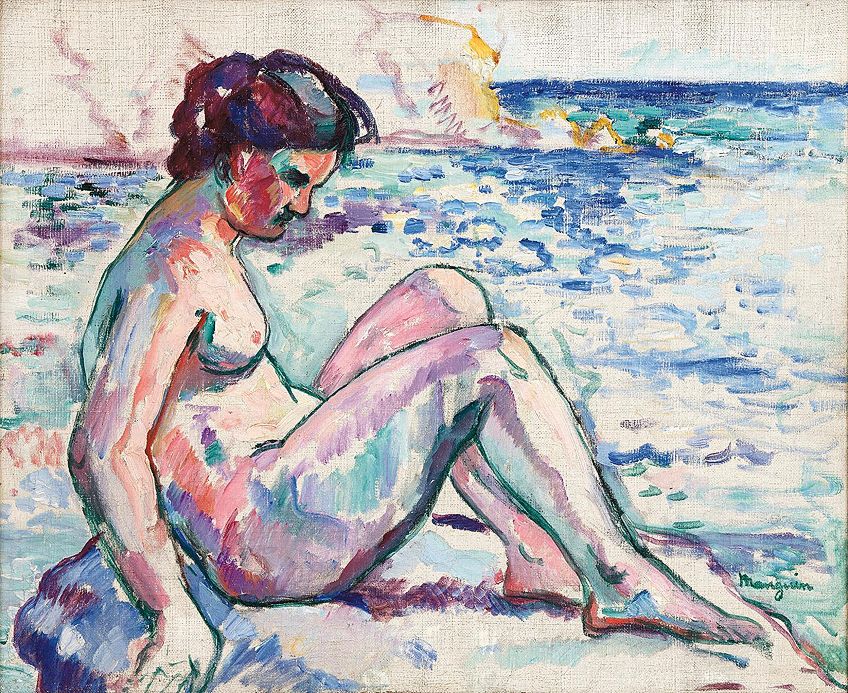

Water lilies (1916-1919) by Claude Monet • Examples of modern art

Impressionists reacted against traditional academic painting styles and sought to capture fleeting moments or impressions of reality. Famous impressionists such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley are renowned for their unique vision and approach to painting.

Modern Art Movements

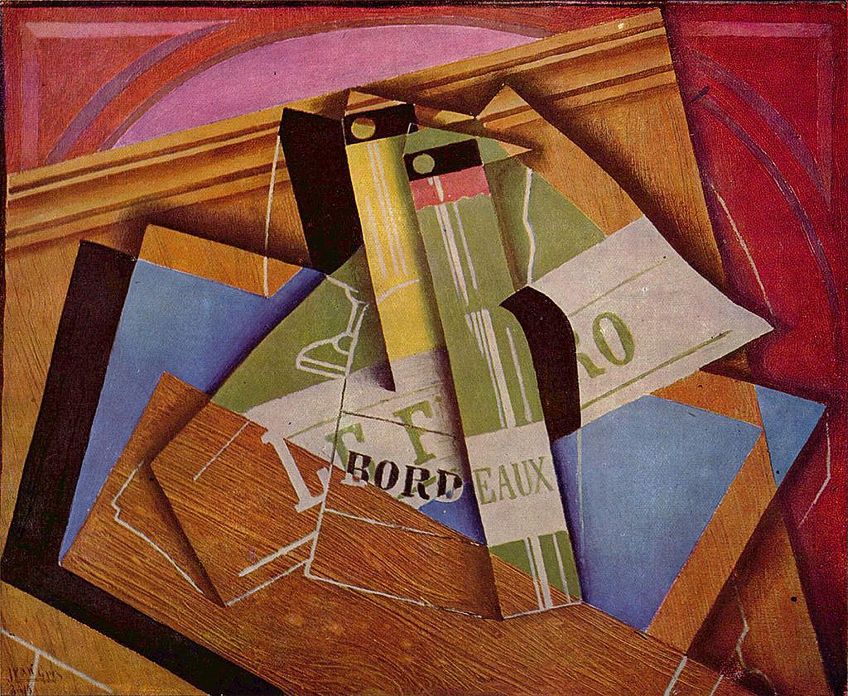

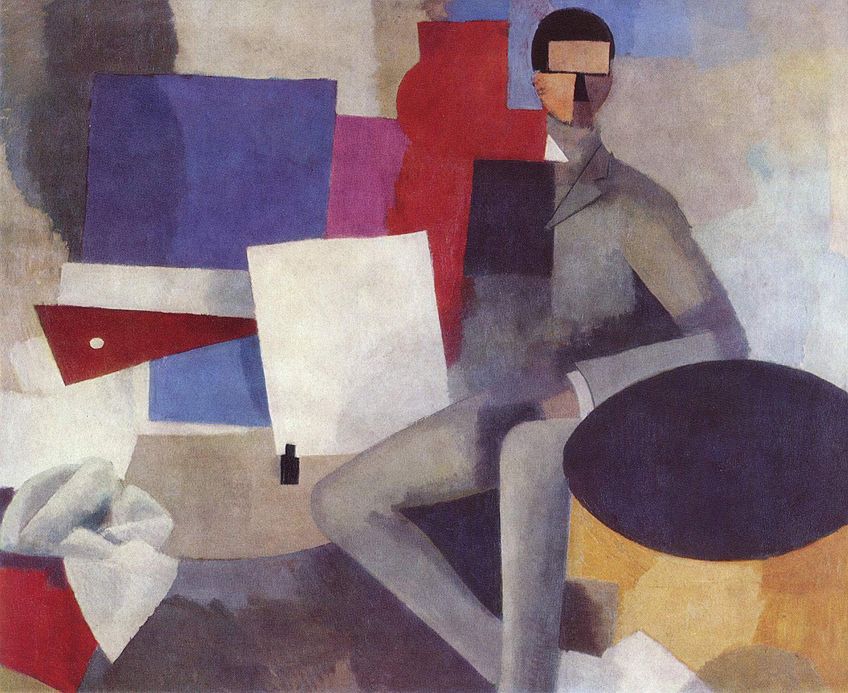

Cubism is an avant-garde art movement that emerged in the early twentieth century. Pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, it sought to challenge traditional notions of perspective and representation by abstracting forms and reducing them to their most basic shapes.

"La Roche-Guyon" (1909) by Georges Braque

Cubism broke down objects into interlocking planes, creating a fragmented view of reality that challenged viewers to see things differently. Today, cubist works continue to inspire creators to experiment with visual expression in unorthodox ways.

Types of Modern Art Movements

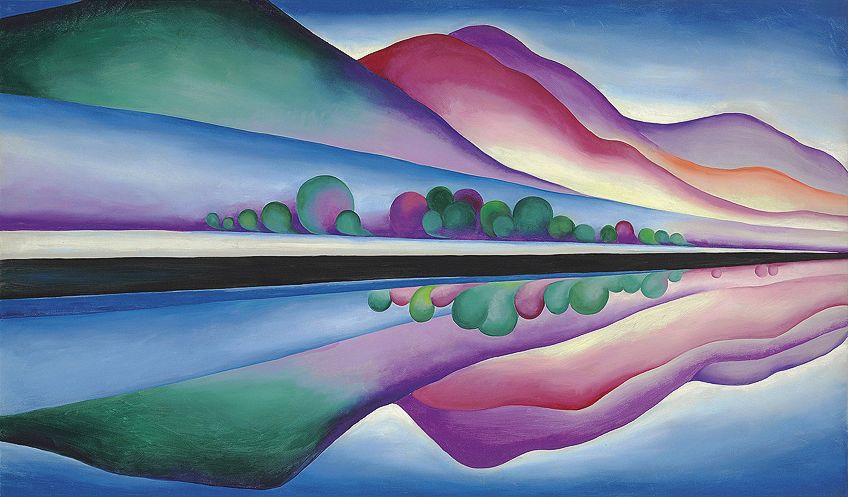

Fauvism is a style of painting that emerged in early twentieth century France. Characterized by bright, expressive colours and simplified forms, it was pioneered by Henri Matisse and André Derain.

André Derain's 'The Turning Road, L'Estaque (1906)

Fauvist works often use shock and contrast to capture the emotional intensity of a subject, emphasizing vivid hues over realism. By focusing on intense colour combinations, Fauve artists conveyed their own unique perspectives on the world around them.

Related Posts

- A Guide to Western Art Movements →

- What is Avant Garde Art Movement? →

- What is Contemporary Art — Definition & Examples →

Modern Art History

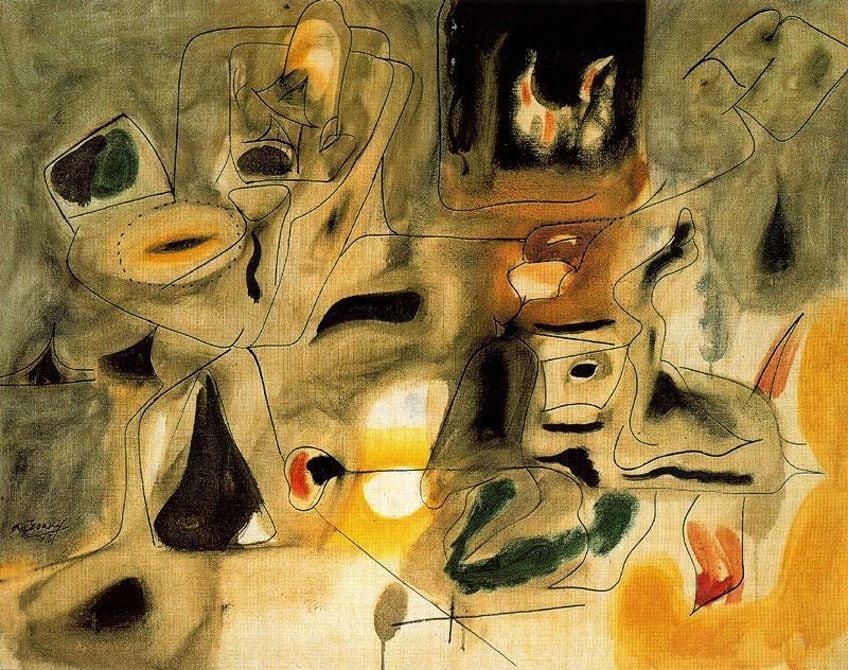

Surrealism is an art movement that emerged in the early twentieth century, characterized by dreamlike imagery and fantastical scenes. It was pioneered by artists such as Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst and Joan Miró, and draws heavily on Freudian psychoanalytic theory.

Roots (1943) by Frida Kahlo • Examples of modern art

By combining subject matter from everyday life with elements of fantasy, surrealist works create a unique visual space where the subconscious comes to life. Surrealism continues to inspire creators to explore the depths of their imagination and represent them through conscious expression.

Types of Modern Art movements

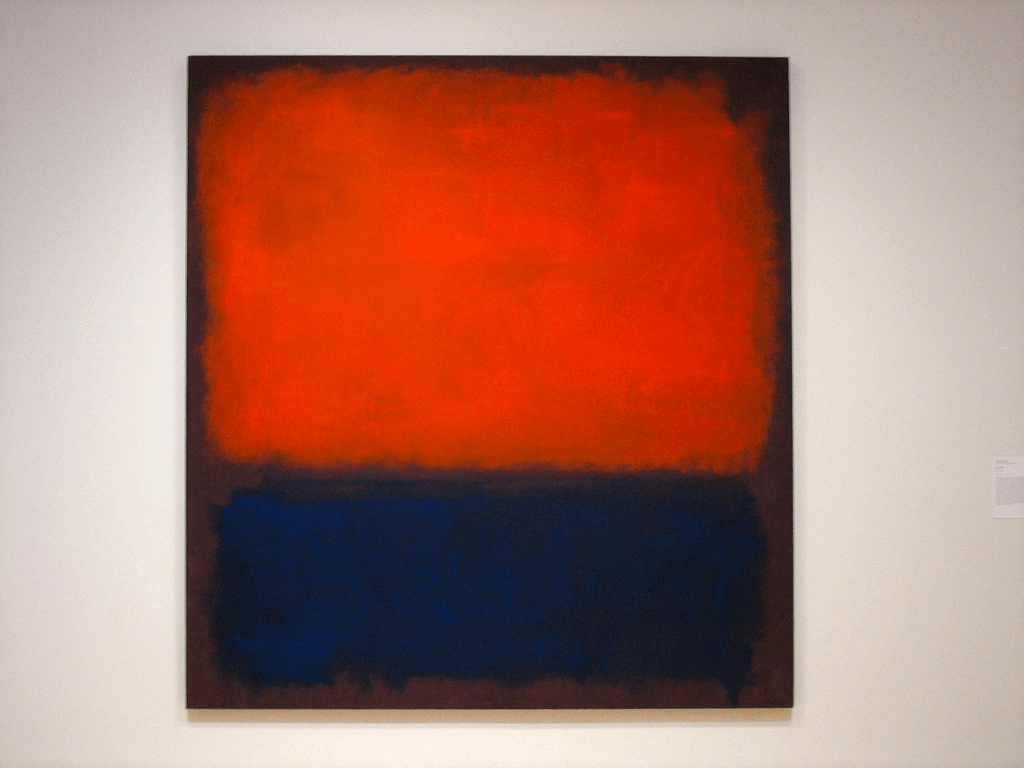

Abstract Expressionism is a style of painting that emerged in post-World War II America. Pioneered by artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning, this movement emphasized the artist's emotional and psychological state over representational representation.

No. 14, 1960 by Mark Rothko

By combining colour, line and form, Abstract Expressionist works explore the depths of human experience through abstract aesthetic techniques. Through its dynamic brushstrokes and symbolic forms, Abstract Expressionism strives to capture the innermost emotions of the painter.

What is Modern Art Pop Art?

Pop Art is a visual art movement that originated in the 1950s and gained massive popularity during the 1960s. It combines elements of popular culture, such as advertisements, comic books, and everyday objects, with abstract art techniques to create a unique aesthetic.

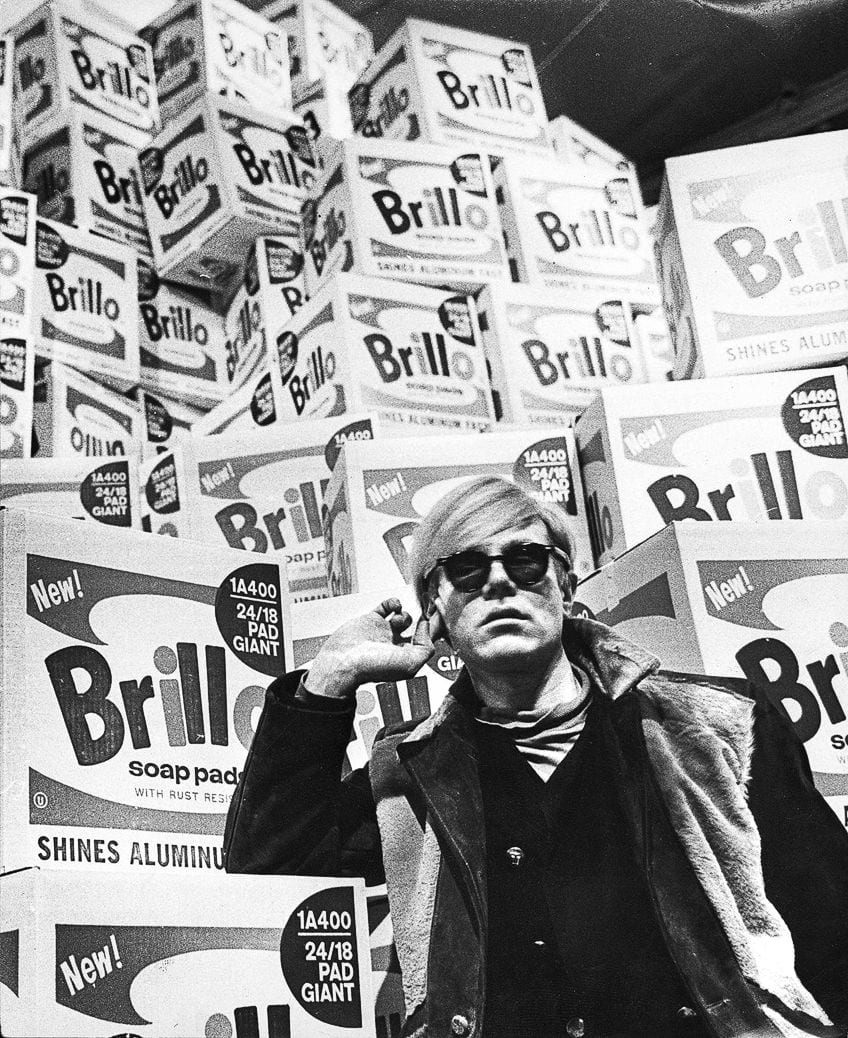

Pop Art celebrates kitsch and popular culture, challenging traditional artistic conventions and subverting hierarchies of taste. Artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein are considered to be primary figures of the movement who pushed it from an underground phenomenon to a global one.

Tree of Life (1985) by Keith Haring

While modern artwork may have its roots in traditional artistic conventions, it often seeks to expand our understanding of what art is and can be – from exploring the intangible depths of our unconscious minds to celebrating popular culture or challenging existing social norms.

Modern art continues to be a major influence on contemporary art, in both its formal and conceptual approaches. These artists pushed boundaries of what could be considered "art" while challenging viewers to look at the world differently.

Explore More Styles and Movements

This was just one of many fascinating segments of art history. There are many eras, styles, artists, and movements to discover. Let's continue our study by choosing the next stop on your way to becoming an art aficionado. Below you can visit our Art Styles Index , our Art History Timeline , or choose an individual movement.

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards.

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

Wow! sharing such a nice info.

Can I have the citations for this?

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- VFX vs. CGI vs. SFX — Decoding the Debate

- What is a Freeze Frame — The Best Examples & Why They Work

- TV Script Format 101 — Examples of How to Format a TV Script

- Best Free Musical Movie Scripts Online (with PDF Downloads)

- What is Tragedy — Definition, Examples & Types Explained

- 2 Pinterest

Summary of Modern Art

Modern art represents an evolving set of ideas among a number of painters, sculptors, photographers , performers, and writers who - both individually and collectively - sought new approaches to art making. Although modern art began, in retrospect, around 1850 with the arrival of Realism , approaches and styles of art were defined and redefined throughout the 20 th century. Practitioners of each new style were determined to develop a visual language that was both original and representative of the times.

Overview of Modern Art

The rapid growth of industry and the progress of technology propelled artists to represent the world in new and innovative ways. The result was an art that took on new colors, alternative forms, emotional expressions, and experiments in abstraction.

The Important Artists and Works of Modern Art

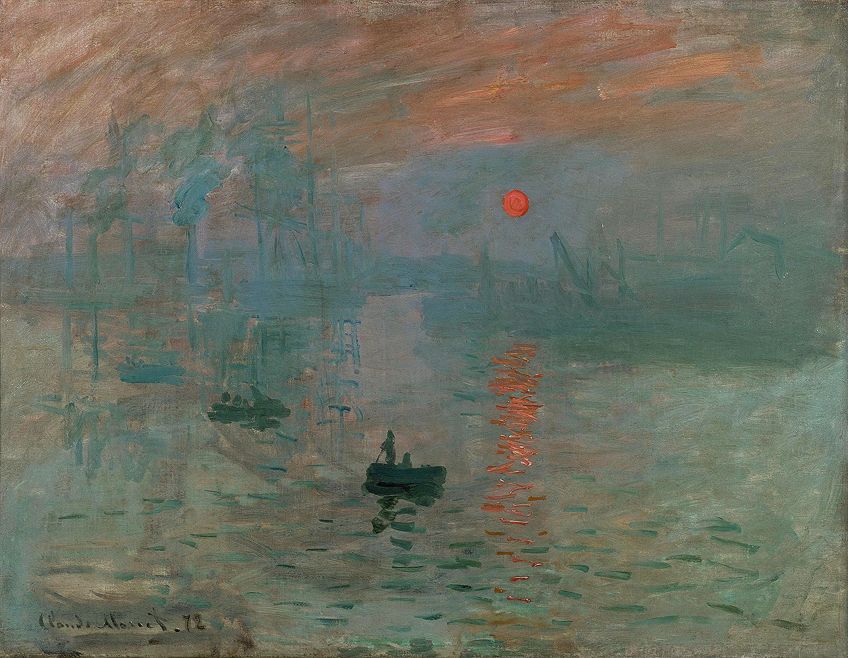

Impression, Sunrise

Artist: Claude Monet

In this seminal work of modern art, Monet's loose handling of paint and his focus on light and atmosphere within the landscape scene are all key characteristics of Impressionism, which is widely considered the first fully modern movement. Monet's use of abstraction evokes what the artist sensed or experienced while painting the scene, which was a highly unusual approach for a painter to adopt at the time. The title of the work, Impression, Sunrise not only provided critics with the name that the movement would later receive, but also conveys the transitory, fleeting and subjective nature of the painting. It is Monet's visual impression of what he observed during that sunrise.

Oil on canvas - Musée Marmottan Monet

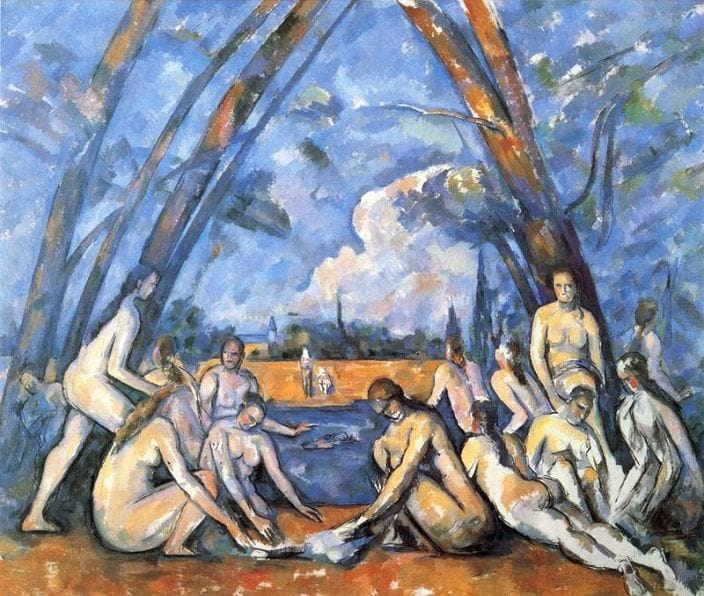

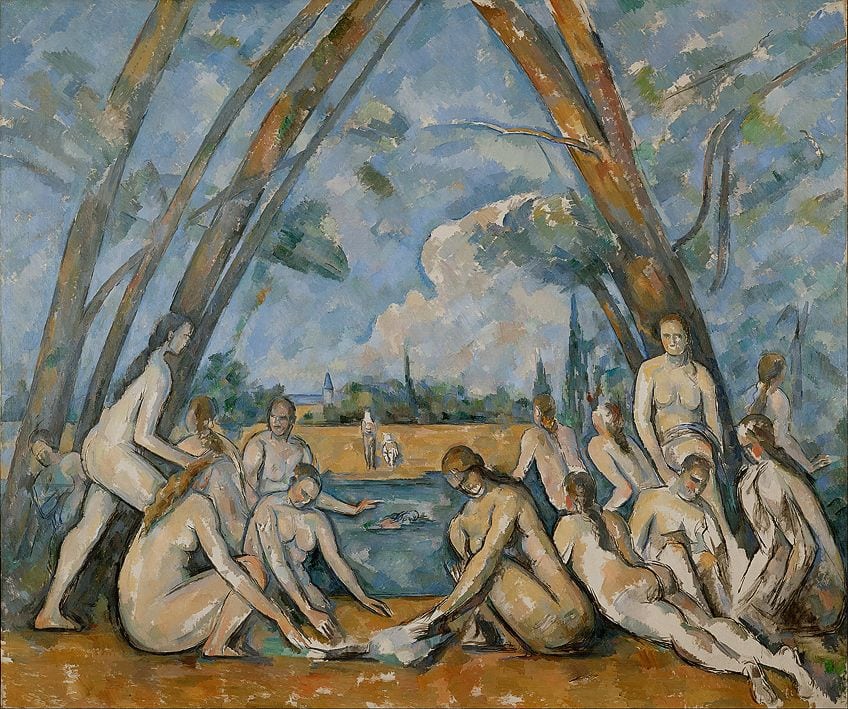

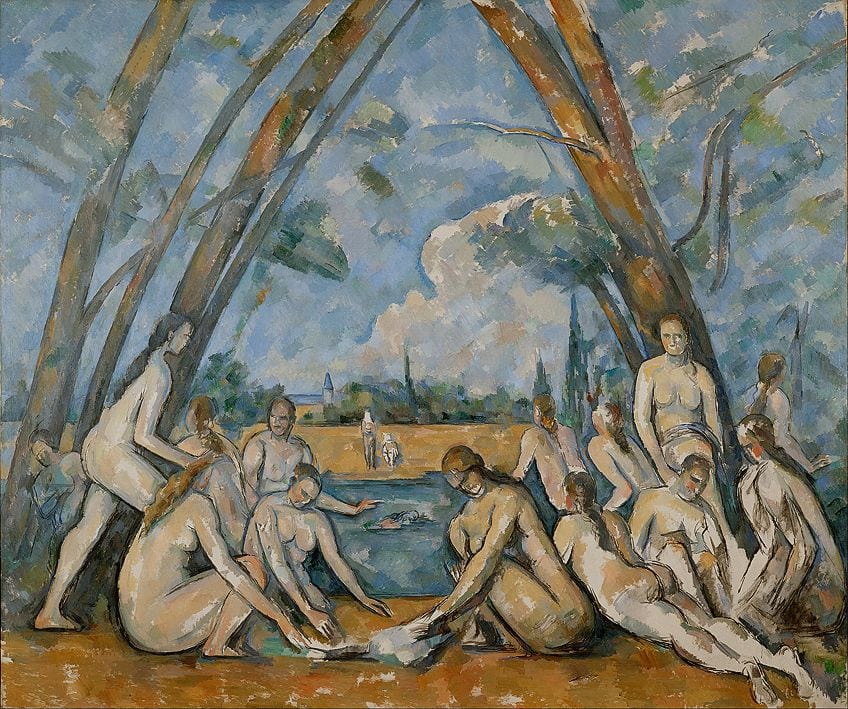

The Large Bathers

Artist: Paul Cézanne

The Large Bathers is one of the finest examples of Cézanne's exploration of the theme of the modern, heroic nude within a natural setting. The series of nudes are arranged into a variety of positions, like objects in a still life, under the pointed arch formed by the intersection of trees and the sky. Cézanne was attempting a departure from the Impressionist motifs of light and natural effect and instead composed this scene as a series of carefully constructed figures, as if creating sculpture with his paintbrush. He was more concerned with the way the forms occupied space than with recording his visual observations. This destruction of regular illusionism and the radical foray into increased abstraction is considered an important precursor to Cubism.

Oil on canvas - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

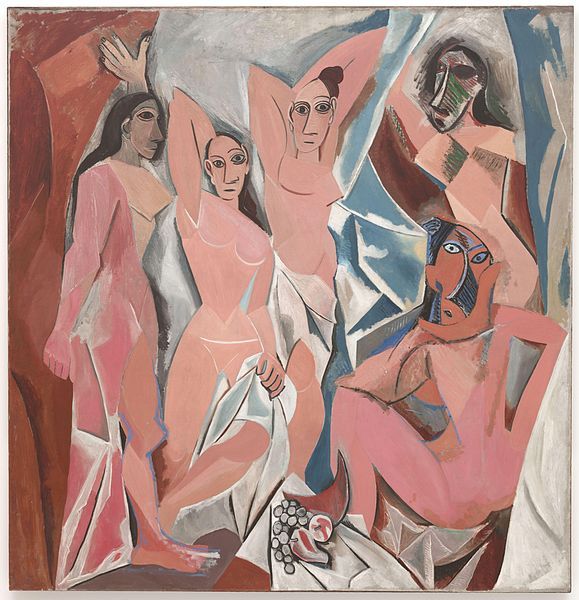

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

Artist: Pablo Picasso

For Les Demoiselles d'Avignon , Picasso gathered inspiration from a variety of sources, including African tribal art, Expressionism, and the Post-Impressionist paintings of Paul Cézanne. Assimilating these seemingly disparate sources in one piece was a new approach to art making and conveys just how much artists' perspectives expanded with the rise of modernism. The painting originally raised significant controversy for its depiction of a brothel scene and for the jagged, protruding, and abstract forms used to depict the women. It is also widely considered the artwork that launched the Cubism movement. The multiplicity of styles incorporated within this work - from Iberian sculpture referenced in the women's' bodies to the sculptural deconstruction of space derived from Cézanne - not only represent a clear turning point in Picasso's career, but make the painting an incredibly distinct achievement of the modern era.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

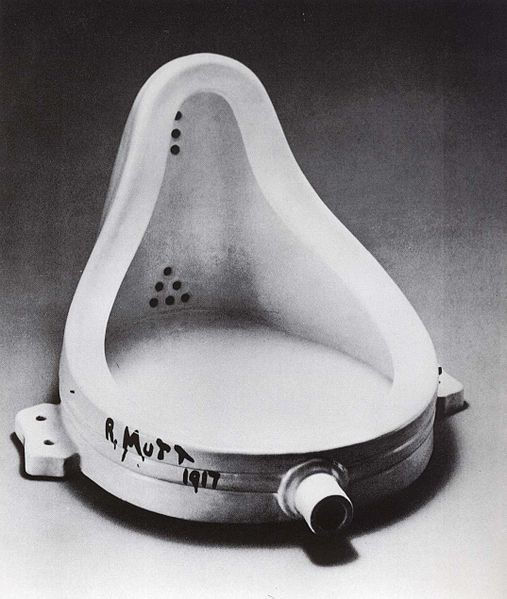

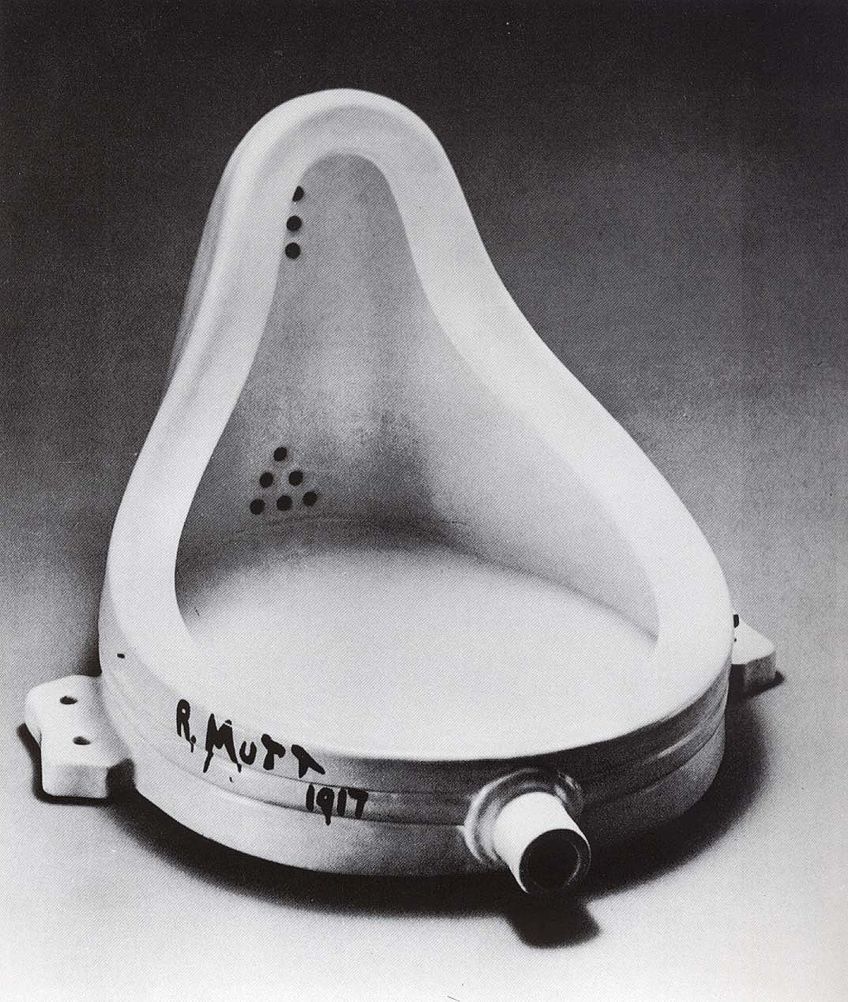

Artist: Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp's invention of the readymade - a manufactured, found object divorced from its utilitarian purpose and presented in a new way as art - helped redefine what constituted a work of art within the modern era. Henceforth, a unique work of art no longer required the act of creation by the artist or visual evidence of the artist's hand in its production, the artist merely needed to designate the work as art for it to be considered as such. Duchamp's Fountain is a mass-produced porcelain urinal, turned on its back and inscribed with the name R. Mutt, a combination of a plumbing company name and a comic. By using an everyday, prefabricated object Duchamp forced the viewer to reconsider the definition of art and who makes that definition. This work in particular, and other readymades, were major influences on the later movements of Pop art, which focused on combining low and high art, and Conceptualism, wherein the idea behind the artwork is as important as the final object.

Porcelain - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

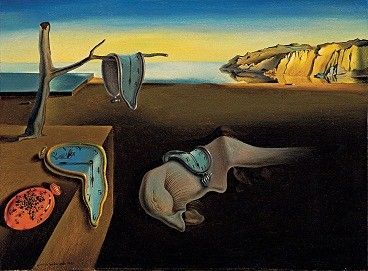

The Persistence of Memory

Artist: Salvador Dalí

This iconic Surrealist painting naturalistically depicts an otherworldly landscape where time is a series of melting watches surrounded by swarming ants that hint at decay, an organic process which held great fascination for Dalí. He sought to portray "images of concrete irrationality," bringing haunting dreamscapes, like this allegorically empty space where time has no power, out of the subconscious mind and onto the canvas. Dalí's celebrated and vivid imagination, his fascination with dream imagery and metaphor, and his exploration into the human subconscious all follow the key characteristics of the Surrealism movement in the early-20 th century.

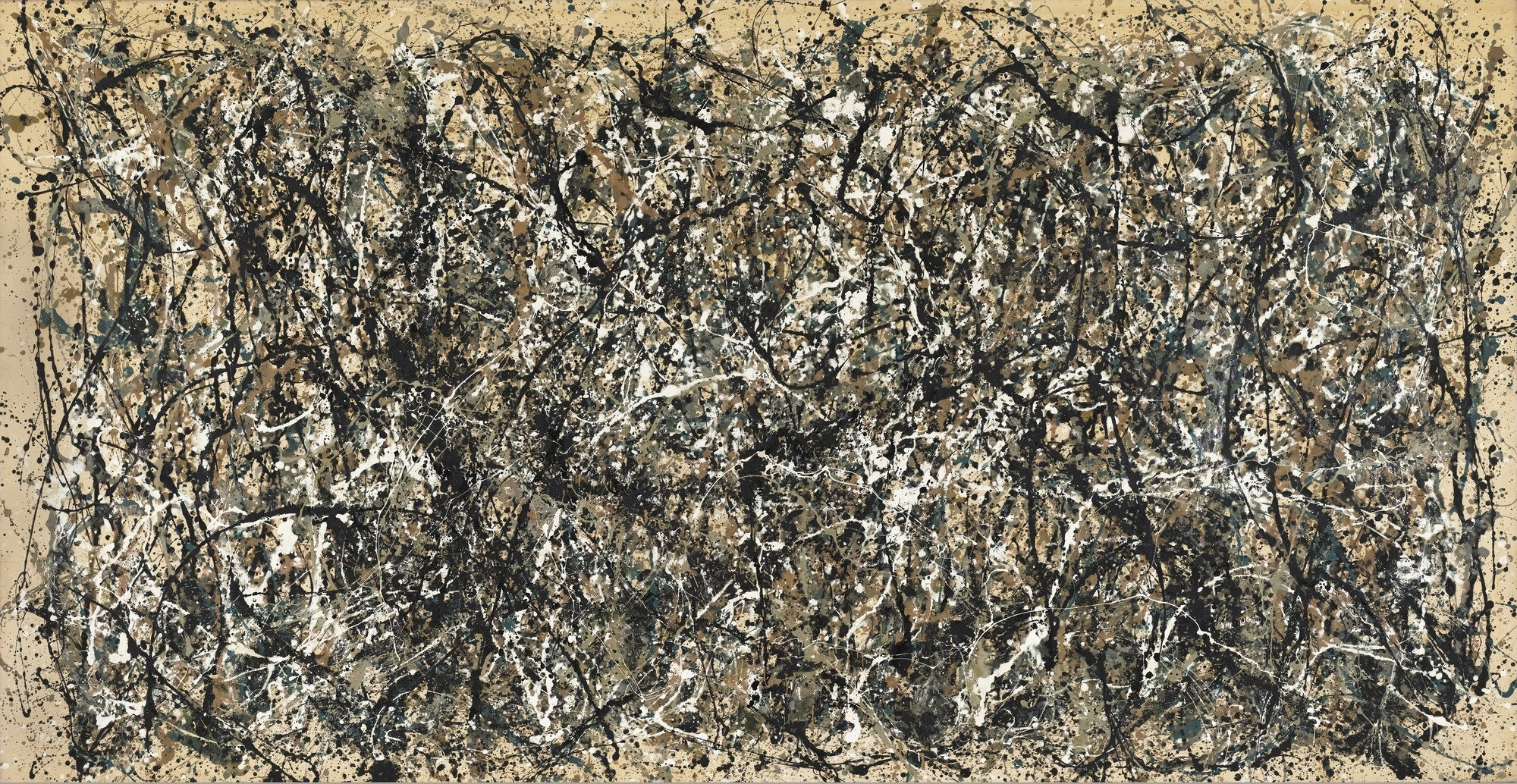

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)

Artist: Jackson Pollock

Through the development of his "drip" style of painting, and thedelicate dance executed in the process of creating the work, Jackson Pollock helped define the idea of Action Painting. With these paintings, Pollock - one of the most famous Abstract Expressionists - discovered a new abstract, visual language for his unconscious that moved beyond the Freudian symbolism of the Surrealists. He broke up the rigid, shallow space of Cubist pictures, replacing it with a dense web of lines and forms, like an unfathomable galaxy of stars. In some respects this work evokes both Impressionism and Surrealism, in the loose, gestural application of the paint and the unconscious nature of the expression laid down on the canvas.

Enamel on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Artist: Jasper Johns

Flag , Johns' first major work, broke away from the emotionally driven style of the Abstract Expressionists by portraying a recognizable, everyday object, which according to Johns is "seen but not looked at." Although the work is representational, the painting is also abstract in its many textures, layers, and materials, including strips of newspaper painted over with encaustic, and the tactile brush strokes that create a painterly, expressive surface. Johns turns a flag, a three-dimensional object, into a two-dimensional painting. This practice of appropriating familiar objects recalled the practices of the earlier Dadaists, particularly Marcel Duchamp, who revolutionized modern art with the readymade. Johns' approach with his Flag paintings renewed interest in Dada and was as an important precursor to Pop art particularly through his use of everyday, mass-produced objects.

Encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric mounted on plywood, three panels - The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

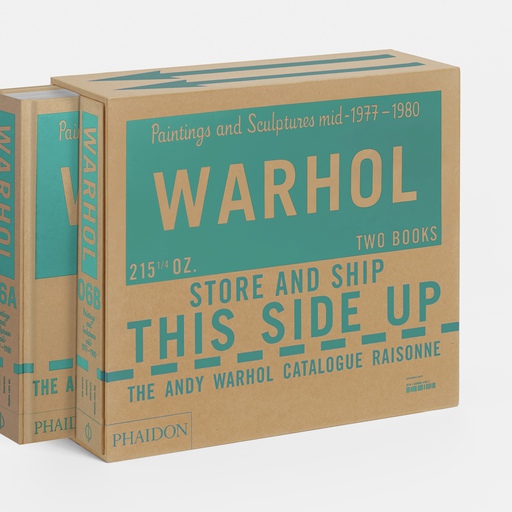

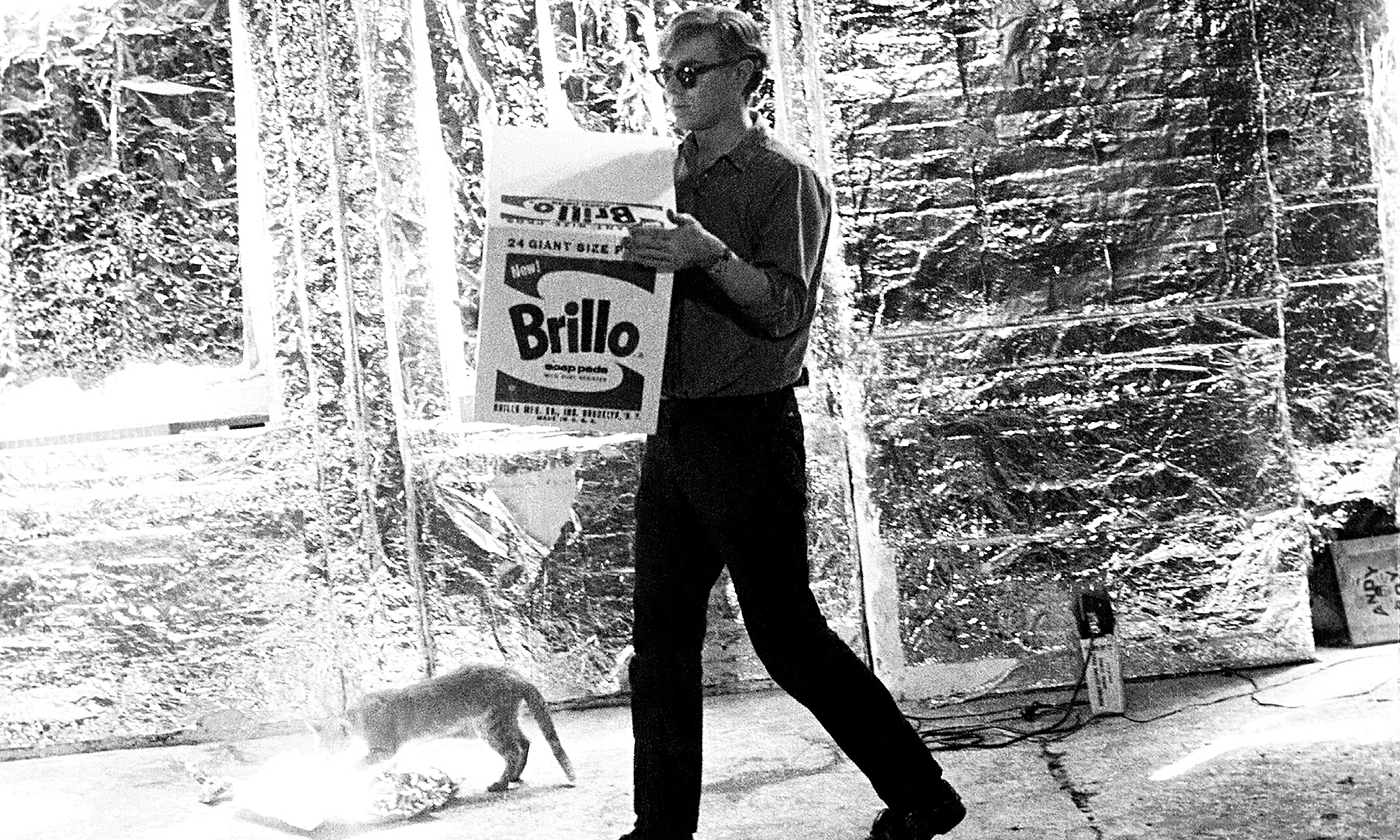

Marilyn Diptych

Artist: Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol completed this work (the first of many devoted to Marilyn Monroe) shortly after the actress's untimely death in August 1962. The image of Monroe, which Warhol recycled and used for all his Marilyn silkscreen paintings, was taken from a publicity shot originally used for the film Niagara . Not dissimilar from Warhol's motifs of Campbell's soup cans or Brillo boxes, the artist stacks and repeats the same image of Monroe here as if she were a consumer product in a grocery store. By juxtaposing the bright colors with monochrome in the diptych, Warhol alludes to her mortality. Though Warhol was a great admirer of the actress, he acknowledged in this and similar works that celebrity was itself a consumer product. Marilyn Diptych is designed as both a tribute to the late icon and a harsh commentary on how we had come to treat these pop cultural icons in the modern era.

Silkscreen ink on synthetic polymer paint on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

One Ton Prop (House of Cards)

Artist: Richard Serra

One Ton Prop presages Serra's mature works, where gravity, weight, counterforce, sinuous movement, and other physical and visual properties are embodied by steel. This sculpture, consisting of four rolled sheets of lead propped on each other, is less a visual exercise for the viewer and more of an intellectual one, obliging one to contemplate the physical properties that allow the piece to remain upright rather than collapse. The unprecedented complexity of such a work is fairly typical of post-minimal sculpture, which relied upon a variety of visual sources and theories for inspiration. While One Ton Prop embodies certain principles of Minimalism, Conceptualism, and even Dada, it is generally referred to as Process art because the process of its construction is inherent and apparent in the final work. The multiplicity of sources and possible styles is typical of the pluralist contemporary world, and the contemporary art that goes with it.

Lead antimony, four plates - The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Definition of Modern Art

Modern art is the creative world's response to the rationalist practices and perspectives of the new lives and ideas provided by the technological advances of the industrial age that caused contemporary society to manifest itself in new ways compared to the past. Artists worked to represent their experience of the newness of modern life in appropriately innovative ways. Although modern art as a term applies to a vast number of artistic genres spanning more than a century, aesthetically speaking, modern art is characterized by the artist's intent to portray a subject as it exists in the world, according to his or her unique perspective and is typified by a rejection of accepted or traditional styles and values.

The Beginnings of Modern Art

Classical and early modern art.

The centuries that preceded the modern era witnessed numerous advancements in the visual arts, from the humanist inquiries of the Renaissance and Baroque periods to the elaborate fantasies of the Rococo style and the ideal physical beauty of 18 th -century European Neoclassicism . However, one prevalent characteristic throughout these early modern eras was an idealization of subject matter, whether human, natural, or situational. Artists typically painted not what they perceived with subjective eyes but rather what they envisioned as the epitome of their subject.

Age of Modernism and Art

The modern era arrived with the dawn of the industrial revolution in Western Europe in the mid-19 th century, one of the most crucial turning points in world history. With the invention and wide availability of such technologies as the internal combustion engine, large machine-powered factories, and electrical power generation in urban areas, the pace and quality of everyday life changed drastically. Many people migrated from the rural farms to the city centers to find work, shifting the center of life from the family and village in the country to the expanding urban metropolises. With these developments, painters were drawn to these new visual landscapes, now bustling with all variety of modern spectacles and fashions.

A major technological development closely-related to the visual arts was photography. Photographic technology rapidly advanced, and within a few decades a photograph could reproduce any scene with perfect accuracy. As the technology developed, photography became increasingly accessible to the general public. The photograph conceptually posed a serious threat to classical artistic modes of representing a subject, as neither sculpture nor painting could capture the same degree of detail as photography. As a result of photography's precision, artists were obliged to find new modes of expression, which led to new paradigms in art.

The Artist's Perspective and Modern Art

In the early decades of the 19 th century, a number of European painters began to experiment with the simple act of observation. Artists from across the continent, including portraitists and genre painters such as Gustave Courbet and Henri Fantin-Latour , created works that aimed to portray people and situations objectively, imperfections and all, rather than creating an idealized rendition of the subject. This radical approach to art would come to comprise the broad school of art known as Realism .

Also early in the 19 th century, the Romantics began to present the landscape not necessarily as it objectively existed, but rather as they saw and felt it. The landscapes painted by Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W. Turner are dramatic representations that capture the feeling of the sublime that struck the artist upon viewing that particular scene in nature. This representation of a feeling in conjunction with a place was a crucial step for creating the modern artist's innovative and unique perspective.

Early Abstraction and Modern Art

Similarly, while some artists focused on objective representation, others shifted their artistic focus to emphasize the visual sensation of their observed subjects rather than an accurate and naturalistic depiction of them. This practice represents the beginnings of abstraction in the visual arts. Two key examples of this are James McNeill Whistler's Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1874) and Claude Monet 's Boulevard des Capucines (1873). In the former, the artist couples large splatters and small flecks of paint to create a portrait of a night sky illuminated by fireworks that was more atmospheric than representational. In the latter, Monet provides an aerial view of bustling modern Parisian life. In portraying this scene, Monet rendered the pedestrians and cityscape as an "impression," or in other words, a visual representation of a fleeting, subjective, and slightly abstracted, perspective.

Modern Art Themes and Concepts

Modern artists.

The history of modern art is the history of the top artists and their achievements. Modern artists have strived to express their views of the world around them using visual mediums. While some have connected their work to preceding movements or ideas, the general goal of each artist in the modern era was to advance their practice to a position of pure originality. Certain artists established themselves as independent thinkers, venturing beyond what constituted acceptable forms of "high art" at the time which were endorsed by traditional state-run academies and the upper-class patrons of the visual arts. These innovators depicted subject matter that many considered lewd, controversial, or even downright ugly.

The first modern artist to essentially stand on his own in this regard was Gustave Courbet , who in the mid-19 th century sought to develop his own distinct style. This was achieved in large part with his painting from 1849-1850, Burial at Ornans , which scandalized the French art world by portraying the funeral of a common man from a peasant village. The Academy bristled at the depiction of dirty farm workers around an open grave, as only classical myths or historical scenes were fitting subject matter for such a large painting. Initially, Courbet was ostracized for his work, but he eventually proved to be highly influential to subsequent generations of modern artists. This general pattern of rejection and later influence has been repeated by hundreds of artists in the modern era.

Modern Art Movements

The discipline of art history tends to classify individuals into units of like-minded and historically connected artists designated as the different movements and "schools." This simple approach of establishing categories is particularly apt as it applies to centralized movements with a singular objective, such as Impressionism , Futurism , and Surrealism . For example, when Claude Monet exhibited his painting Impression, Sunrise (1872) as part of a group exhibition in 1874, the painting and the exhibition as a whole were poorly received. However, Monet and his fellow artists were ultimately motivated and united by the criticism. The Impressionists thus set a precedent for future independently minded artists who sought to group together based on a singular objective and aesthetic approach.

This practice of grouping artists into movements is not always completely accurate or appropriate, as many movements or schools consist of widely diverse artists and modes of artistic representation. For example, Vincent van Gogh , Paul Gauguin , Georges Seurat and Paul Cézanne are considered the principal artists of Post-Impressionism , a movement named so because of the artists' deviations from Impressionist motifs as well as their chronological place in history. Unlike their predecessors, however, the Post-Impressionists did not represent a cohesive movement of artists who united under a single ideological banner. Furthermore, the case can be made that some artists do not fit into any particular movement or category. Key examples include the likes of Auguste Rodin , Amadeo Modigliani , and Marc Chagall . Despite these complications, the imperfect designation of movements allows the vast history of modern art to be broken down into smaller segments separated by contextual factors that aid in examining the individual artists and works.

The Avant-Garde and The Progression of Modern Art

The avant-garde is a term that derives from the French "vanguard," the lead division going into battle, literally advance guard, and its designation within modern art is very much like its military namesake. Generally speaking, most of the successful and creative modern artists were avante-gardes. Their objective in the modern era was to advance the practices and ideas of art, and to continually challenge what constituted acceptable artistic form in order to most accurately convey the artist's experience of modern life. Modern artists continually examined the past and revalued it in relation to the modern.

Modern, Contemporary, and Postmodern Art

Generally speaking, contemporary art is defined as any form of art in any medium that is produced in the present day. However, within the art world the term designates art that was made during and after the post-Pop art era of the 1960s. The dawn of Conceptualism in the late 1960s marks the turning point when modern art gave way to contemporary art. Contemporary art is a broad chronological delineation that encompasses a vast array of movements like Earth art , Performance art , Neo-Expressionism , and Digital art . It is not a clearly designated period or style, but instead marks the end of the periodization of modernism.

Postmodernism is the reaction to or a resistance against the projects of modernism, and began with the rupture in representation that occurred during the late 1960s. Modernism became the new tradition found in all the institutions against which it initially rebelled. Postmodern artists sought to exceed the limits set by modernism, deconstructing modernism's grand narrative in order to explore cultural codes, politics, and social ideology within their immediate context. It is this theoretical engagement with the ideologies of the surrounding world that differentiates postmodern art from modern art, as well as designates it as a unique facet within contemporary art. Features often associated with postmodern art are the use of new media and technology, like video, as well as the technique of bricolage and collage , the collision of art and kitsch, and the appropriation of earlier styles within a new context. Some movements commonly cited as Postmodern are: Conceptual art , Feminist art , Installation art and Performance art .

Useful Resources on Modern Art

- Modern Art Movements All major modern art movements, as well as a number of related styles and tendencies

- Modern Art Artists Comprehensive guide to the most important modern and contemporary artists

- The Progression of Modern Art This timeline displays the major trends and movements in modern art

- Top Modern Art Works This timeline is a guide to the 50 most important and groundbreaking works of art from the modern era

- The Shock of the New By Robert Hughes

- Art Since 1900 Our Pick By Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin Buchloh

- Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics By Herschel B. Chipp, Peter Selz, Joshua C. Taylor

- Art in Theory, 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas Our Pick By Charles Harrison and Dr. Paul J. Wood, eds.

- Defining Modern Art: Selected Writings of Alfred H. Barr, Jr. By Alfred Hamilton Barr, Irving Sandler, Amy Newman

- The Tradition of the New By Harold Rosenberg

- The Theory of the Avant-Garde By Renato Poggioli, Gerald Fitzgerald

- The Meanings of Modern Art By John Russell

- Museum of Modern Art's Library and Archives MoMA's physical and online archives provide among the world's most comprehensive surveys of modern and contemporary art

- The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Collection The SFMoMA collection features 30,000 works, with interactive educational resources for special topics in modern art

- Modern Art Notes Modern art and Contemporary art blog by Tyler Green

- Uncertainty: Modernity and Art Our Pick Episode from "This is Civilisation" British series

- Great Museums: In Our Time: The Museum of Modern Art Our Pick

- The Contemporary and the Historical Our Pick By Donald Kuspit / Artnet.com

- Modernist Painting By Clement Greenberg

- African Influences in Modern Art By Denise Murrell / Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University

- Art, Philosophy, and the Philosophy of Art By Arthur C. Danto

Related Artists

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Justin Wolf

Edited and published by The Art Story Contributors

Modern Art – An Exploration of the 20th-Century Modernist Movement

The Modernism movement within art, arising in the early 20 th century, referred to art that accurately reflected the society in which artists found themselves. After the French industrial revolution, artists demonstrated a great desire to move away from the traditional aspects that previously governed fine art in favor of creating artworks that sought to capture the experiences and values in modern industrial life. Thus, Modern Art existed as a broad movement that incorporated a variety of other “isms” under its title.

Table of Contents

- 1 What Is Modernism?

- 2 An Appropriate Modernism Definition

- 3.1 The Influence of the Industrial Revolution

- 3.2 The Influence of War

- 4 Main Characteristics of Modern Art

- 5 Criticisms of Modern Art

- 6.1 Impressionism (1870s – 1880s)

- 6.2 Fauvism (1905 – 1907)

- 6.3 Expressionism (1905 – 1920)

- 6.4 Cubism (1908 – 1914)

- 6.5 Futurism (1909 – 1944)

- 6.6 Dadaism (1916 – 1924)

- 6.7 Surrealism (1924 – 1950s)

- 6.8 Abstract Expressionism (1940s – 1950s)

- 6.9 Pop Art (1950s – 1960s)

- 7 Modern Art in America

- 8.1 Paul Cézanne (1839 – 1906)

- 8.2 Claude Monet (1840 – 1926)

- 8.3 Georges Seurat (1859 – 1891)

- 8.4 Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954)

- 8.5 Giacomo Balla (1871 – 1958)

- 8.6 Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973)

- 8.7 Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968)

- 8.8 Salvador Dalí (1904 – 1989)

- 8.9 Jackson Pollock (1912 – 1956)

- 8.10 Andy Warhol (1928 – 1987)

- 9 Modernism into Postmodernism

What Is Modernism?

Known as a global movement that existed in society and culture, Modern Art developed at the start of the 20 th century in reaction to the widespread urbanization that appeared after the industrial revolution. Modern Art, also referred to as Modernism, was viewed as both an art and philosophical movement at the time of its emergence. This movement reflected the immense longing of artists to produce new forms of art, philosophy, and social structures that precisely reflected the newly developing world.

Modernism included a variety of different styles, techniques, and media within the broad movement. However, the fundamental principle that was demonstrated in all the artworks of each movement within Modernism was a complete dismissal of history and traditional concepts associated with realism.

Artists began to make use of new images, materials, and techniques to create artworks that they thought better reflected the realities and hopes that existed in rapidly modernizing societies.

Due to the fact that it was not considered a singular and cohesive movement, many different movements developed that fell into the bracket of Modernism. These Modern movements included Post-Impressionism , Fauvism, Cubism, Dadaism, Expressionism, and Futurism, to name a few. The unifying element that existed within these movements was the consistent yearning to break away from the customs of representational art .

A great influence of Modernism was considered to be the Impressionism movement, as artists practicing within this period began to make use of non-naturalistic colors when depicting subjects. Impressionism was wildly unpopular with high society at the time, as it embraced elements that did not fit into the traditional way of making art. Thus, this deviation from the norm was said to pave the way for the beginning of Modernism Art as it embraced the start of abstract tendencies that were still to be explored.

Modernists disregarded old rules relating to color, perspective, and composition in order to create their own visions of how artworks should be constructed. These attitudes were strengthened by the rapid changes that were brought on by the industrial revolution decades before, as well as the start of World War One in 1914. Artists, in reaction to the horror and brutality that was seen in society as a result of war, abandoned intellect for intuition within their artworks and depicted the world exactly as they observed it.

This period of rapid changes characterized modern society at the time, leading artists to constantly update and refine their techniques when making art so as to accurately depict the aspirations and dreams of the modern world that had developed. Modernism was a response to the rapidly changing conditions of life due to the rise of industrialization and the beginning of wartime, with artists looking for new subject matter, working techniques, and materials to better capture this change.

Additionally, the reason for this change in technique was because artists regarded traditional forms of art to be outdated and therefore obsolete within modern society. Artists stated that they felt a growing alienation from the previous Victorian society and searched for new modes of expression that would adequately reflect how they felt within the new world. Modernism was heavily motivated by the different social and political agendas of the time, with artists attempting to reflect these ideal visions of human life and society in their works.

Whilst artists experimented with new techniques to adequately depict modern life, they also attempted to express the emotional and psychological effects of negotiating a world in rapid changes in their artworks. This was an important element in Modern art, with artists like Henri Matisse and Paul Cézanne exploring their subject matters in-depth and in ways that shocked society.

Modernism Art was essentially the creative world’s answer to the rationalist customs and viewpoints of the new lives and ideas that were provided by the technological progressions of industrialization. Artists attempted to represent their experience of modern life in innovative ways irrespective of the artistic genre they were working from. Thus, Modern Art was characterized by artists who rejected traditional styles and values, instead including their own perspective into their works and portrayed their subjects exactly as they existed in the world.

By the 1960s, Modernism had become a leading movement within the art sphere. While some academics have said that the movement continued into the 21 st century, others have stated that it evolved into a late type of Modernism that was termed “Postmodernism.” Despite using the term “modernism” in its name, the Postmodern art movement demonstrated a vast departure from Modernist principles, as it rejected its fundamental assumptions in an effort to produce a new kind of art.

An Appropriate Modernism Definition

Modernism has been interpreted to mean a variety of things, ranging from a manner of thinking to an aesthetic form of self-examination. Additionally, the movement has also been viewed as a broad social, cultural, and political initiative that upheld the principles of impermanence within the newly urbanizing world.

The terms “Modernism” and “Modern Art” were used by art historians and critics when describing the series of art movements that emerged after the Realism period that was dominated by artist Gustav Courbet . Realism occurred just prior to the Industrial Revolution in France and along with Courbet’s distinct style, marked the beginning of an art period that abandoned the romanticism that previously dictated artmaking.

The philosophical characteristics that accompanied the Modernist movement helped to define it as a way of thinking in addition to an art medium . This was demonstrated by the self-consciousness and self-reference that artists included within their artworks. These brazen and unashamed elements were used to refer to their new modern reality, as well as to highlight their straying away from what was previously seen as fine art.

In Western society, Modernism was defined as a socially liberal trend of thought. Modern Art was said to acknowledge the strength of human beings in creating, enhancing, and restructuring their environment through the advancements in technology and scientific knowledge. These changes were demonstrated through the subsequent art movements that developed, which all found their basic principles under the broad term of Modernism.

Poet Ezra Pound’s famous 1934 line, “Make it New”, went on to exist as the benchmark of the Modernism approach, as Pound ordered artists and creatives to produce art out of distinctly innovative materials.

Thus, an appropriate Modernism definition would be artworks that rejected all traditional forms of art in an attempt to include the perspective of artists and the consequences and effects of industrialization in the developing contemporary world.

The Origins of Modern Art

Modern Art was said to begin in 1863 after artist Édouard Manet exhibited his shocking and disrespectful painting, Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe , at the Salon des Refuses in Paris. Despite Manet’s artwork paying respect to a Renaissance artwork by Raphael, its exhibition to society is widely considered to mark the start of the changes that began to occur in art, which led to the emergence of Modernism.

After Manet’s painting, the new generation of artists were tired of following the conventional academic art forms that dominated the 18th and early 19th century. These artists were branded as “modern”, and they started to create a variety of Modernism paintings that were based on new themes, materials, and methods.

Whilst sculpture and architecture were also affected by these new ideas within art, their period of changes occurred at a later stage. Initially, fine art painting appeared to be the first creative sphere that abandoned traditional views in favor of a Modern outlook that acutely reflected society at the time.

In the centuries that preceded the Modern era, many advancements were made in the numerous styles that developed, as shown in movements such as the Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo periods . The prevailing characteristic that appeared throughout these movements in art was the idealization of the subject matter.

Instead of painting exactly what they saw, artists were known to paint what they imagined to be the epitome of their subject.

The first Modern artist who veered away from these traditional values of art was Gustave Courbet, who sought to establish his own distinct style in the mid-19 th century. Courbet achieved this with his large 1948 – 1850 painting, Burial at Ornans , as he portrayed a funeral of an ordinary man with filthy farmworkers surrounding the open grave. This angered the formal art academy, as only works devoted to classical myths or historical scenes were seen as appropriate subject matter for a painting of this proportion.

Despite being shunned for this artwork, Courbet’s painting went on to be highly influential to the following generations of Modern artists. This idea of rejecting artworks previously reserved for religious and important imagery was embraced by artists when Modernism fully developed, with artists creating immense artworks to depict the lives and struggles of common society as they saw fit.

The Influence of the Industrial Revolution

The onset of the Industrial Revolution in France in the mid-19 th century was seen as a turning point in both the world’s history and the elements of formal art. With the invention and rapid advancement of technology, artists began to abandon a romanticized view of the world in order to accurately depict what they were seeing. This drastic urbanization led to a change in the pace and quality of ordinary life, with artists feeling compelled to represent this change in the works.

Many people began to relocate from rural farms into city centers in order to find work, which transferred the center of life from the country and villages to the growing urban capitals. Artists were drawn to these rapid developments and began to depict the new visual landscapes that emerged in society, as they bustled with a variety of modern wonders and styles that were waiting to be fully explored.

A significant technological advancement that occurred within this time frame was the invention of the camera in 1888 , which began to rapidly progress. As technology began to develop, photography became more and more accessible to the general public. Suddenly, ordinary people were able to create their own portraits simply by taking a photograph, instead of commissioning an artwork to be made.

This development in portraiture presented a threat to traditional artistic modes of portraying a subject, as no existing artforms were able to capture the same degree of detail and depth as a photograph could. Due to the accuracy of photography, artists were forced to find new methods of expression, which led to new ideas and paradigms in the artistic community.

The Influence of War

Whilst modern society believed in the idea of progress and its many benefits, this belief faded when the First World War began. This period of time sparked further outrage that was felt in connection to traditional art, as artists began to question the morality of urbanization if it could lead to something as gruesome as war.

World War One had a destructive impact on Europe and on the minds of every individual that it reached. A noticeable shift in artistic creation happened after the war, as societies began to distance themselves from its aftermath. Cities began to quickly expand, which led artists, writers, and philosophers to begin adopting views and beliefs that differed from those that existed prior to the war.

Some artists turned towards notions of beauty, order, and harmony within their modern works as a way to offset the disorder, separation, and ugliness that was left from the war. Others began to represent the individuals as hollow and ghostlike within their artworks, in an attempt to refer to the destruction that the war had caused. This was very noticeable in the artworks that formed part of the German Expressionist movement during World War One.

However, some artists viewed this fragmentation and deformity of figures in the art to be cruel, as society had already suffered so much death and pain when soldiers returned home.

Some artists believed that returning to prewar Cubism and Expression was impossible, and so instead looked ahead for a new form of expression that would appropriately capture their current time whilst not coming across as brutal.

Main Characteristics of Modern Art

Lasting for almost an entire century, Modern Art involved multiple different art movements that all incorporated a variety of different elements and techniques. Modernism embraced everything in its subsequent movements, including pure abstraction, hyperrealism, and anti-art styles to name a few. Due to the movement’s great diversity, it is difficult to consider any unifying characteristics which can be used to define this era.

However, one thing that can be said about Modernism Art that managed to separate it from prior movements, as well as the Postmodern movement which followed it, was that artists truly believed that their art was important and held real value. This differed from their predecessors who simply assumed that their work was valuable if it incorporated traditional elements, purely because the art academies told them so.

Despite there being no singular defining characteristic of Modern Art, it incorporated various important characteristics over a few of the movements. The first characteristic was that most Modern Art movements attempted to create a new type of art, through using styles such as collage art, assemblage, animation, photography, land art , and performance art.

The second characteristic was that most modern painters attempted to make use of new materials when creating art, such as attaching fragments of newspapers and other items to canvases. A good example of this is artist Marcel Duchamp, who popularized the use of readymade objects through his iconic artworks which he essentially created out of trash. By using a variety of new materials, a type of assemblage art was created, which allowed some artists to combine a variety of different and ordinary materials in one singular work.

The third characteristic that most Modernists incorporated into their work was a vivid use of color. The movements that made use of this technique the most were Fauvism and Expressionism, as artists practicing within these genres tended to exploit color in a variety of ways so as to emphasize the emotions they were attempting to convey.

Lastly, the fourth characteristic that was used within these Modernism movements was the invention of new techniques. Examples of this include automatic drawing and frottage that were invented by Surrealist artists , and benday dots and silkscreen painting that were introduced by Pop artists and brought into formal art.

Criticisms of Modern Art

Like every other artistic period, Modern Art had its fair share of criticisms. Due to the fact that Modernism disregarded conventional elements of art and placed emphasis on freedom of expression, experimentation, and radicalism, it was met with complete disbelief and outrage from audiences. Modernism also managed to alienate certain audiences through its eccentric and unpredictable effects, such as the disturbing motifs that were included in Surrealist artworks.

A major criticizer of the Modern Art era was the Nazi government in Germany, who deemed the artworks that fell into the bracket of Modernism as narcissistic and nonsensical. The Nazis went so far as to label Modern Art as “degenerate art”, and had some works belonging to the German Expressionism movement destroyed.

Most Important Movements Within Modernism

As Modernism was merely an umbrella term for a variety of different movements that came into existence after the Industrial Revolution and in the early 20 th century, it is easy to wonder: what is Modernism? Essentially, Modernism was a period in which many movements existed. What made these movements similar was the unifying characteristic that rejected all traditional forms of art, which made them each modern within their own sense.

Impressionism (1870s – 1880s)

Seen as an important precursor to the Modernist movement, Impressionism made famous the use of non-naturalist colors in the artworks that were created. The importance of Impressionism was demonstrated by artist Claude Monet , whose landscape works focused on capturing transient moments of light and color in excruciating detail.

This attention to detail was also seen when artists chose the colors within their artworks, as these vivid and shocking colors were said to emphasize the emotions that they felt. Additionally, Impressionists made use of loose and highly textured brushstrokes that made the painting unrecognizable if viewed from up close. These specific techniques made Impressionism very disliked in the conventional art spheres, as the works created did not conform to the traditional elements of art.

This led to Impressionism being seen as an important influence of Modernism, as it was one of the initial movements to reject the realism associated with traditional art through the color palette and brush strokes used. Impressionism went on to validate the use of unrealistic colors in artworks, which went on to pave the way for the emergence of abstract art . This continued to be upheld as an important characteristic in the Modern Art movements that developed.

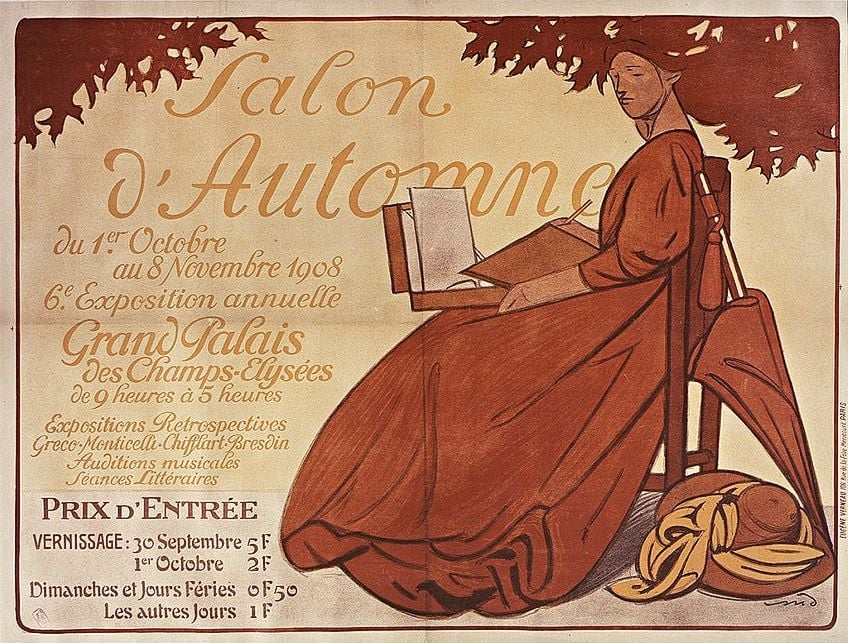

Fauvism (1905 – 1907)

Led by Henri Matisse, Fauvism was an incredibly short-lived movement that existed during the mid-1900s in Paris. Despite its lifespan, it was an incredibly dynamic and influential movement and was seen as a very fashionable and modern style during its time.

Fauvism is known for launching at the Salon d’Automne , with the movement becoming instantly renowned for its intense, loud, and non-naturalistic colors that were used in the artworks created. This excessive use of color made the previous movement of Impression seem monochromatic in its palette choice, with the use of colors being extremely exaggerated in Fauvism.

The major contribution of Fauvism to the Modern Art movement was its demonstration of the power of color. Fauvism showcased the independent strength that colors possessed, which turned artworks into a force to be reckoned with when various colors were combined. Additionally, Fauvism was seen as a highly subjective movement, existing as a strong contender to the previous classical artistic style that was used.

Expressionism (1905 – 1920)

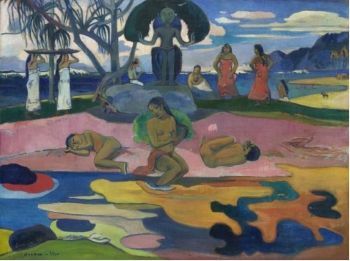

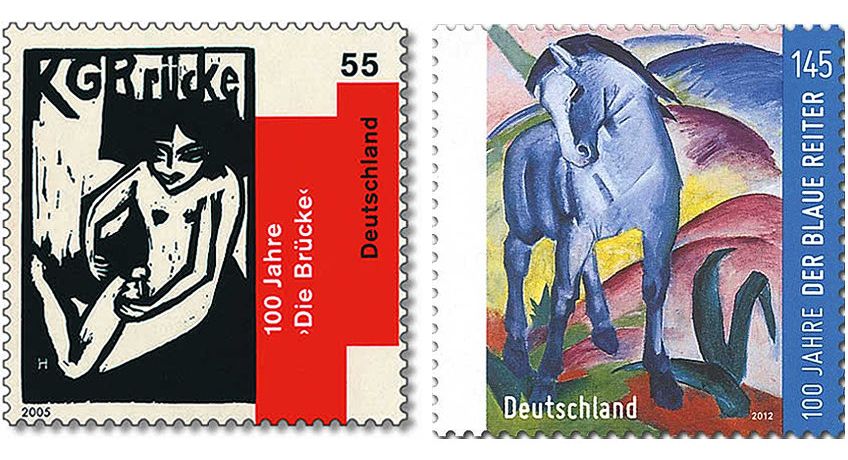

Despite being predicted in the artworks by artists such as Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh, the Expressionist movement only truly came into being in pre-war Germany. Two groups within Expressionism emerged named Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter , which went on to define this movement as one that belonged within Modern Art.

Existing before and after World War One, Expressionism was said to be heavily based on the brutalities that occurred. The Expressionist movement used the horror associated with the war as its main subject and created works that accurately echoed the devastation and consequences felt in society after it ended.

Die Brücke , translated to “the bridge”, was formed in Dresden in 1905 and existed as one of the integral groups within Expressionism. Founded by artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner , Die Brücke made use of figural distortions, a primal straightforwardness of rendering, and expressive use of color in its artworks.

The second essential group within the Expressionist movement was Der Blaue Reider . Known as “the Blue Rider”, this group was founded by Wassily Kandinsky in Munich in 1911 and centered around the potential of pure abstraction within the art that was created. Kandinsky also argued that abstraction offered completeness that mere representation did not.

The importance of Expressionism within Modernism was that the movement popularized the idea of subjectivity in painting. Additionally, the vivid color palette used in Expressionist artworks existed as a fundamental characteristic within other Modern Art movements.

Cubism (1908 – 1914)

Developed by artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Cubism existed as quite a harsh and challenging style of painting. This art form differed greatly from previous movements that were inspired by the techniques of linear perspective and softly curved volumes made famous in the Renaissance. Instead, Cubism made use of a compositional arrangement of flat and shattered planes that were combined to make up a painting.

Cubism was developed into two versions, namely Analytical Cubism and Synthetic Cubism. Analytical Cubism, which existed from 1910 to 1012, examined the use of basic shapes and overlapping surfaces to portray the individual forms of the subjects in a painting. Synthetic Cubism appeared after and ran from 1912 to 1914. This style emphasized on including characteristics such as simple shapes and bright colors that held hardly any depth in the artworks that were created.

Despite its influence over abstract art, the appeal surrounding Cubism was extremely limited. However, an important contribution of the Cubism movement within Modern Art was that it offered an entirely new alternative to standard perspective due to its creation of the flat picture plane.

Futurism (1909 – 1944)

The Futurist movement, founded by Italian art theorist and poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, was an art form that celebrated technology, speed, inventions such as the automobile and the airplane, and scientific achievement.

This movement saw all of these avenues of development as worthy of praise and believed that they were responsible for the advancement of modern society. Futurism captured the dynamism and energy that existed in the modern world and proposed the creation of art that celebrated modernity and the development of technology in all its forms.

Existing as a heavily influential movement, it borrowed elements from other eras such as Neo-Impressionism, Italian Divisionism, and Cubism. This was demonstrated through the splintered forms and numerous viewpoints that were typical of some Futurist artworks.

Futurism was at its most influential stage between 1909 and 1914, as World War One brought the first wave of Futurism to a close. This led artists to turn to different styles that incorporated elements of modernity. However, after the war had ended, Marinetti revived the movement and continued to develop into what was called second-generation Futurism. Thus, Futurism was seen as a significant Modern Art movement as it introduced the element of movement into art and linked the concept of beauty to scientific achievement.

Dadaism (1916 – 1924)

Seen as the first anti-art movement to be established, Dada was an art practice that rebelled against the system which had allowed the atrocity of World War One to take place. Dadaism began at the Cabaret Voltaire in Switzerland and was led by a group of artists who had relocated to the neutral country during the outbreak of the war.

The boisterous, facetious, and iconoclastic performances that were created were intended to lay heavy criticism on the bourgeois society and the economic forces that the Dadaists blamed for the onset of war. Dadaism quickly became a revolutionary movement as its main aim was to undermine the art establishment in an attempt to point out the futility in order and tradition as it led to war.

Using performance art that could not be commodified, the Dada movement advocated for the eradication of the commercial art institution along with its traditional concepts and reasons. Dada artists embraced the notions of irrationality and originality within their works, as demonstrated by artists such as Jean Arp, Hugo Ball, and Marcel Duchamp.

Existing as the most notable artist within the Dada movement was Duchamp, whose infamous 1917 Fountain caused enormous controversy due to him merely making use of an ordinary urinal in his artwork and submitting it for exhibition. Duchamp also introduced the idea of the “ready-mades” into art, which was the use of everyday items in place of traditional artistic elements.

Dadaism existed as an important movement in Modern Art, as it managed to disrupt the traditional art academy through its anarchistic tendencies. Dadaism brought great creativity and critique into modern society, as demonstrated through its embrace of junk items as art, which forced audiences to consider what intellect within art and society truly meant.

Surrealism (1924 – 1950s)

Existing right after the Dadaism movement and still maintaining its seditious humor, Surrealism was established in Paris by writer Andre Breton. Surrealism was seen as the last significant avant-garde movement that existed in the interwar period, as it began to fade out with the onset of World War Two.

Evolving out of the nihilistic Dada movement, Surrealism rejected the notions of order and beauty within its artworks, yet it was not viewed as anti-art or heavily political. Surrealism was built on a preference for the irrational and created artworks that used dreams, hallucination, and random and automatic image generation. This was done to evade rational thought processes in the creation of art, in addition to demonstrating the absurdity that existed in the intellectual minds of society.

Surrealist artists avoided any notion of rationality within their works. Instead, artists leaned towards psychological concepts about the unconscious mind that was primarily introduced by neurologist Sigmund Freud, who believed that this was where the base of artistic creativity lay. Thus, Surrealism attempting to connect with the unconscious mind through interpreting dreams and using automatism within the artworks created.

The main contribution of Surrealism to Modernism was its ability to generate a refreshing set of new artworks that were constructed out of one’s subconscious mind. Surrealism was able to introduce a period of imagination and fun into the interwar years within Modern Art.

Abstract Expressionism (1940s – 1950s)

Developed in New York City after the ending of World War Two, Abstract Expressionism was established by a group of vaguely associated artists who sought to create a stylistically varied body of work. Abstract Expressionism, also known as the New York School, introduced extreme new directions in art and relocated the art world’s attention to focus on Abstract Modernist art.

Abstract Expressionism, which was strongly influenced by European artists living in America, consisted of two main styles. The first was an extremely energetic form of gestural painting that was introduced by Jackson Pollock, and the second was a more passive mood-directed style known as Color Field painting made famous by Mark Rothko .

Abstract Expressionism aimed to create art that, while still abstract in nature, was able to evoke great expression and emotion as an effect. This was inspired by the previous movement of Surrealism, as Abstract Expressionists also subscribed to the notion that art should develop from the unconscious mind. The influence of Abstract Expressionism within Modernism was its ability to popularize abstraction, in addition to inventing a new style called “action painting”, as demonstrated by Pollock’s drip paintings.

Pop Art (1950s – 1960s)

The last influential movement said to exist within Modern Art was Pop Art. Initially emerging in America and England in the late 1950s, Pop Art reflected the popular culture and mass consumerism that existed in America in the early 1960s. Pop Art existed as a dominant form of avant-garde art due to its brazen and easy-to-recognize imagery, its use of vivid block colors, and the inclusion of famous icons.

Andy Warhol was an exemplary figure of the Pop Art movement, as his use of famous icons and popular celebrities in his artworks made his work incredibly well-known. Pop Art also branched into the creation of posters, advertisements, comic strips, and product packaging, to demonstrate the flexibility of art within the new consumer-driven society. Additionally, these materials helped to reduce the separation that existed between commercial art and fine art.

Essentially, Pop Art celebrated the consumerism of the post-World War Two period. The movement rejected Abstract Expressionism in an effort to praise and subsequently glorify advertising, the material consumer culture, and the image representation of the mass production era. Thus, the main contribution of Pop Art within Modern Art was its demonstration that any art deemed worthy could be unsophisticated and mass-marketed, in addition to being constructed out of mere commodities.

Modern Art in America

Due to the expansiveness of Modern Art, it is not easy to integrate the various movements of America and Europe into a chronological timeline. A multitude of historical and sociocultural factors exist for both American and European Modernism, which makes combining the two variations of Modern Art very challenging.

Modern Art took slightly longer to ground itself in America among its artists, critics, and the public. Prior to the development of Modernism, there was a variety of other American movements that had started to embrace elements of modernity in the artworks created.

The event that acted as the true catalyst for the growth of Modernism within America was the 1913 Armory Show, which was exhibited in New York. Nearly 1300 artworks created by 300 artists were displayed, with two-thirds of these artists being American. The style within these works included Ashcan, French Impressionist, Cubist, and Fauvist , which gave fellow artists, collectors, critics, and the public a glimpse into the future of Modern Art.

Modernist ideas began to grow within the minds of American artists , which were encouraged in the upcoming years by refugee artists who fled Europe at the onset of World War One. Additionally, the influx of artists who left Nazi-occupied Europe in the run-up to World War Two also brought new techniques and philosophies, which greatly inspired American artists and helped spur the development of Modern Art.

The introduction of Abstract Expressionism was also seen as a major turning point in American Modernism, as artists were largely influenced by the number of European avant-garde artists who had settled in America. Due to the country’s economic advantage that emerged after the end of World War Two, New York replaced Paris as the unofficial capital of Western art. This was thought to lead to the eventual appearance of Modern Art as a full-blown movement within America.

Notable Modern Artists and Their Well-Known Artworks

Throughout the expansive period of Modern Art, many different artistic movements embraced the rejection of traditionalism and the introduction of modernity within the Modernism paintings created. Listed below are some of the more notable artists and their artworks to come out of the Modernism era.

Paul Cézanne (1839 – 1906)

A significant artist existing in the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist period was Paul Cézanne, whose artworks have been considered as important precursors to the development of Modern Art. Completed in the year that Cézanne passed away, The Large Bathers was painted from 1898 to 1906 and existed as one of the finest examples of Cézanne’s investigation of the theme of the modern and courageous nude within a natural setting.

Cézanne created a series of these bathing nudes, with The Large Bathers existing as both his last and his largest composition in the series. Within this work, Cézanne depicted the female nudes in numerous effortless positions, with the ease that he created his composition being likened to him arranging objects in a still life. The archway formed by the overlapping trees and sky helped to ground the figures in the middle of the painting, in addition to turning them into the focal point through drawing the eyes of the viewer inwards.

When painting The Large Bathers , Cézanne attempted to create an artwork that would be viewed as timeless. He achieved this through his deviation from the Impressionist themes of light and natural effect and instead composed the scene as a series where his emphasis fell on the carefully constructed figures. Cézanne was more interested in the way his forms were able to occupy space as opposed to depicting his visual observations as realistically as possible.

This artwork was seen as a significant predecessor in the development of Cubism, as its disruption of illusionism and growing abstraction were elements that were later adopted in the Cubist movement. The brushstrokes within this painting were obvious, which gave Cézanne’s work an incomplete quality. Additionally, he boldly left traces of his working patterns on his paintings, with his colors blending into each other at certain points.

Despite its seemingly unrefined state, The Large Bathers is still seen as a masterpiece of Modern Art due to the characteristics it introduced to the art world. Cézanne’s work was praised for its use of vivid yet cool colors which swirled around the canvas, with the commanding nature of his colors later going on to be an important characteristic within Modern Art.

Claude Monet (1840 – 1926)

Another influential artist within the Impressionism period was Claude Monet. Impressionism was generally thought to be the first fully Modern movement to exist, with some of its characteristics influencing the later movements in the Modernism period. Within his landscape artworks, Monet placed focus on light and atmosphere, which existed as key characteristics of the Impressionism movement. In his 1873 painting, titled Impression, Sunrise , Monet demonstrated his focus on the same elements.

Impression, Sunrise is seen as Monet’s pioneering Modernism artwork. A misty sunrise over a French harbor is depicted, along with a very blurred background. The orange and yellow tones chosen by Monet contrast vividly with the darker ships, with little to no detail being visible to viewers at all.

Monet’s loose style of painting and use of abstraction evoked what he felt and experienced when painting the scene at the harbor, which was a very uncommon approach for a painter at that time. Additionally, the title of his work conveyed the ephemeral nature of his painting, as it was based purely on what Monet observed at the time of the sunrise.

This painting was very unusual of Monet’s own work during this time and of the Impressionist movement in general, as little to no Impressionist methods of light and color were shown. The colors chosen were incredibly restrained and at certain places, Monet left pieces of the canvas entirely visible.

Monet’s work was considered to be extremely atmospheric and subjective as opposed to analytical, which would go on to be an important characteristic of Modern Art. Monet kept details to a bare minimum within Impression, Sunrise , with the painting making use of a fleeting and near-abstract technique. Due to this, the style of his painting drew more attention than the actual composition itself, which outraged viewers at the time. Audiences even claimed that they were unable to identify what they were viewing at all.

Due to the techniques employed by Monet within Impression, Sunrise , this work is viewed as an important precursor to Modernism, as it made use of a variety of styles that would go on to later inform other Modern movements.

Georges Seurat (1859 – 1891)

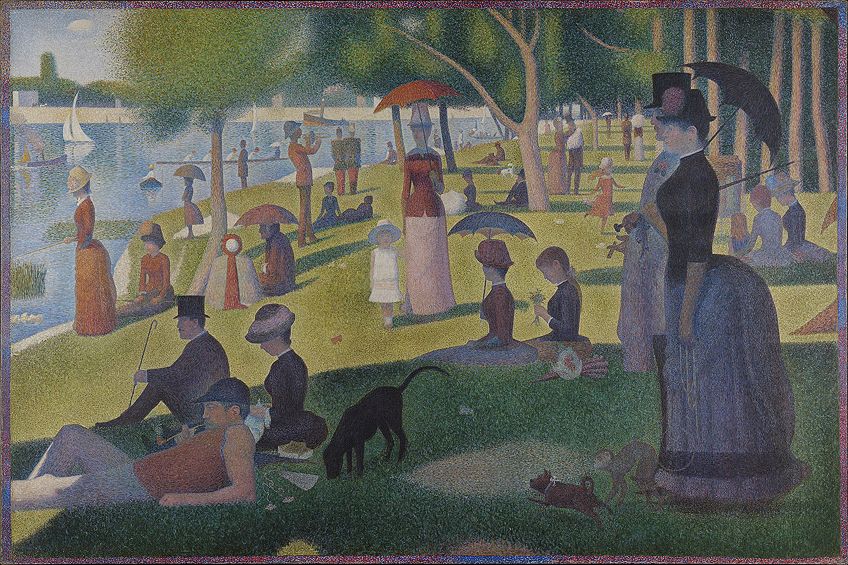

An important Neo-Impressionist French artist was Georges Seurat, who’s paintings seemed to supersede his own reputation. Seurat altered the direction of Modern Art through his introduction of the Neo-Impressionism movement , which emerged at a time in modern France where painters were searching for new methods to explore. Existing as the best-known and largest painting done by Seurat is his 1884 to 1886 masterpiece, titled Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte , which was an important Neo-Impressionist work.

Seurat’s artwork depicts relaxed individuals in a park on an island in the Seine River known as “La Grande Jatte”, which was a popular place for middle- and upper-class Parisians in the 19 th century. What makes this painting so remarkable is that its theme captured something as boring and ordinary as a normal Sunday afternoon, yet it still carried an air of mystery.

At first glance, this work appears to be a painting of ordinary people relaxing in the park. However, upon closer inspection, truly peculiar images come to light. For example, the lady carrying the parasol on the right appears to be walking a monkey on a leash, and the little girl wearing the white dress that is placed in the center of the painting is the only figure who is depicted without a shadow.

Additionally, Seurat’s bizarre artwork introduced a new style of painting called Pointillism , with this technique still being known by this name today. This painting technique was highly systematic and near scientific in its development but was relatively easy for other artists to copy. Seurat started with a layer of small horizontal brushstrokes of complementary colors , upon which he later added small dots that appeared solid and radiant from afar.

This was done to prove his theory that painting in dots was able to create a brighter color than painting in strokes, as the viewer’s eye would be able to optically blend the colors from a distance. This led to a radical turning point within the Modern Art era, as artists were presented with an alternative way to define forms within their artworks as opposed to making use of the worn-out traditional methods.

Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954)

Existing as an important artist within the Fauvism movement was Henri Matisse , who was well-known for his expressive use of color and his fluid and original drawing techniques. Matisse is commonly regarded as an artist who helped define the groundbreaking developments within visual arts, with some of his paintings existing as important works in early Modernism.

One such work is his painting, titled Le Bonheur de Vivre (The Joy of Life) , which he painted from 1905 to 1906. Within this work, Matisse depicted the figures of blue-green and pink nudes dancing, singing, and frolicking in what seemed to be an unblemished and multicolored version of Eden.

Through overemphasizing and simplifying his figures at odd angles, Matisse was able to emphasize the canvas as a mere two-dimensional support for the harmonious contrast of color as opposed to any sort of precise depiction of nature.

Matisse separated color from reasoning within his artwork, as he used these bright tones as an expressive medium that was not intended to make any visual sense. It was thought that this technique was used to introduce the concept of Primitivism into 20 th century Modernism, with artists like Matisse choosing to paint naïve and simple artworks in an era dominated by rapid industrialization and modernization. Additionally, Matisse’s work implied a lot about the new territory of Modernism that was emerging.

Giacomo Balla (1871 – 1958)

Futurist artist Giacomo Balla produced some incredibly well-known artworks within Modern Art. As a key proponent of Futurism, Balla skillfully depicted light, movement, and speed in his artworks. What set him aside from other Futurists was that his focus on movement did not relate to that produced by a machine, which led his artworks to be quite playful and witty in nature.

Balla’s most notable work, as well as the most well-known work of the Futurist movement, was his 1912 painting, titled Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash . Within this work, Balla combined the idea of art and science, which was influenced by his fascination with chronophotographic studies of animals in motion. Chronophotography existed as a technique whereby several photos were taken in quick succession to capture the movement of a subject.

The artwork depicts a black dachshund walking alongside a woman wearing dark shoes and a dress, which added to the monochrome feeling of the painting. Both the feet of the figure and the dog are shown to be in speedy motion, as signified by their slight blurring and the multiplication of their parts, as well as the numerous depictions of the dog lead.

A striking feature of this artwork is the quiet sincerity that is implied by the skittering dog. Thus, while the painting’s title expressed the lively movement as seen by the motion of the dog, the peaceful honesty present in the work contradicts this.

To reinforce the perception of speed, Balla painted the ground using diagonal lines and positioned his signature and the date at a lively angle. This work made use of characteristics that were significant within Modernism, such as the fascination with speed and technology, which were later referred to in other modern movements.

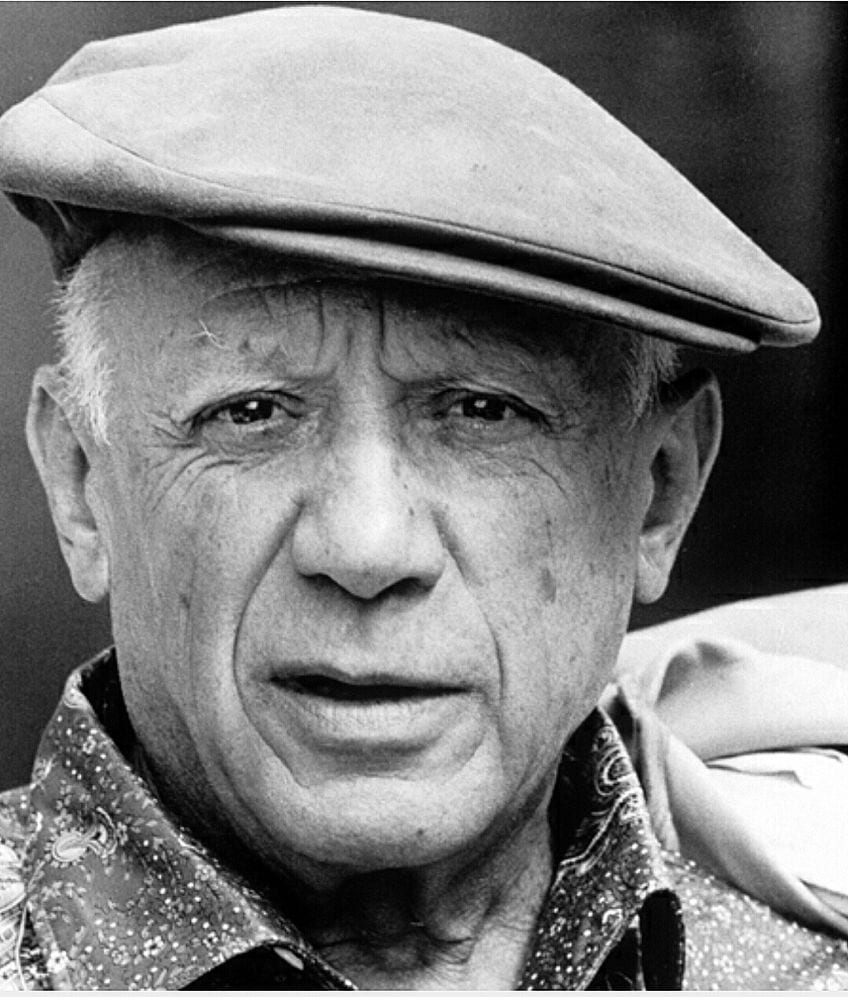

Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973)

An important artist working within the Cubism movement was Spanish artist Pablo Picasso. His artworks have been categorized into different periods, such as his Blue Period and his Rose Period, which allowed Picasso to experiment with a variety of styles. These include both Analytic and Synthetic Cubism, as well as making use of some elements of Neoclassicism and Surrealism in his later works.

Out of all his Cubist works, his 1907 painting titled Les Demoiselles d’Avignon remains one of his most notable works. Considered to be the artwork that essentially launched the Cubism movement, Picasso’s work was met with substantial controversy for its portrayal of a brothel scene and for the rough, prominent, and abstract forms he used to represent the women.

When painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon , Picasso accumulated inspiration from various sources, such as African tribal art , Expressionism, and the Post-Impressionist artworks of Paul Cézanne. These sources are noticeable within Picasso’s work, as demonstrated by several of the women whose faces seemed to be modeled on African masks, as well as the sculptural deconstruction of space that originated from the works of Cézanne.

The multiplicity of the styles used within this painting clearly represented a turning point in Picasso’s career, as well as managing to separate his version of Modern Art from the Western artistic tradition. Thus, the integration of these diverse sources within a single painting demonstrated the new approach to art-making that artists had adopted. This also conveyed how the perspective of artists had expanded with the steady rise of the Modernist movement.

Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968)

Commonly regarded as one of the most influential artists who helped define the innovative developments in the plastic arts at the start of the 20 th century is Marcel Duchamp . Additionally, Duchamp is also commonly recognized as the face of the Dada movement, in which he exists as one of its most notable contributors.

Duchamp’s invention of the “readymade”, in which he made use of common items and claimed them to be artworks, rattled the traditional and formal art academies. In using ordinary items, that were sometimes even considered to be junk, Duchamp managed to separate the items from their utilitarian purpose in order to present them as new forms of art. Thus, Duchamp helped to reformulate what made essentially made up a work of art within the modern era.